Abstract

Colorectal cancer is a heterogenous and mostly sporadic disease, the development of which is associated with microbial dysbiosis. Recent advances in subtype classification have successfully stratified the disease using molecular profiling. To understand potential relationships between molecular mechanisms differentiating the subtypes of colorectal cancer and composition of gut microbial community, we classified a set of 34 tumour samples into molecular subtypes using RNA-sequencing gene expression profiles and determined relative abundances of bacterial taxonomic groups. To identify bacterial community composition, 16S rRNA amplicon metabarcoding was used as well as whole genome metagenomics of the non-human part of RNA-sequencing data. The generated data expands the collection of the data sources related to the disease and connects molecular aspects of the cancer with environmental impact of microbial community.

Subject terms: Data publication and archiving, Colorectal cancer, Cancer genomics

| Design Type(s) | transcription profiling design • disease analysis objective |

| Measurement Type(s) | transcription profiling assay • rRNA 16S |

| Technology Type(s) | RNA sequencing • amplicon sequencing |

| Factor Type(s) | sex |

| Sample Characteristic(s) | human gut metagenome • Homo sapiens • colorectum |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Background & Summary

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide, in terms of both incidence and mortality1. Most cases of CRC are sporadic with no known genetic link. Environmental factors are therefore likely to play a critical role in the development of the disease, and a key characteristic of the colon is that it houses the largest proportion of the human microbiome, suggesting that this might play a role in causing CRC. Recent data points to the importance of the microbial communities in the gut, the microbiome, and possible links to the development of CRC2–5. If this is the case, understanding the role of the microbiome in CRC will have profound effects on cancer rates, since it is potentially relatively easily to manipulate, using diet, pre- and probiotics and faecal transplants6–9. However, despite the intense interest in the field and increasing evidence pointing to a role for the microbiome in CRC, convincing connections with clinical parameters and outcome are rarely seen.

CRC is a highly heterogeneous disease, with varying clinical outcomes, response to therapy, and morphological features, and molecular subtyping systems based on CpG-island methylation, microsatellite instability and gene mutations have shown strong associations with outcome and response to therapy in CRC10–13.

Contrary to other microbiome studies, where CRC is treated as a single disease entity, we focused on the association between Consensus Molecular Subtypes (CMS) of colorectal cancer and gut microbiome patterns in the accompanying primary publication14. We stratified a set of CRC tumour samples into CMS according to their gene expression profiles15 and assessed differences in bacterial communities among CMS. The gene expression profiles were generated using RNA sequencing, and 16S rRNA metabarcoding as well as metagenomic analysis of non-human portion of the RNA sequencing data were employed for bacterial taxa quantification. We analysed the enrichment/depletion of bacterial species in one subtype compared to the other subtypes and showed enrichment of certain oral bacteria associated with CMS, which was validated using targeted quantitative PCR.

The data generated in this study combine various views of each sample as multiple different methods were used to obtain information about the samples. This allows us to study associations between the results of the particular methods. Making the raw sequencing data available together with the scripts used for data processing and analysis, we enable reuse of the data and extend the collection of the data sources related to CRC, for which the aetiology is not yet well understood.

Methods

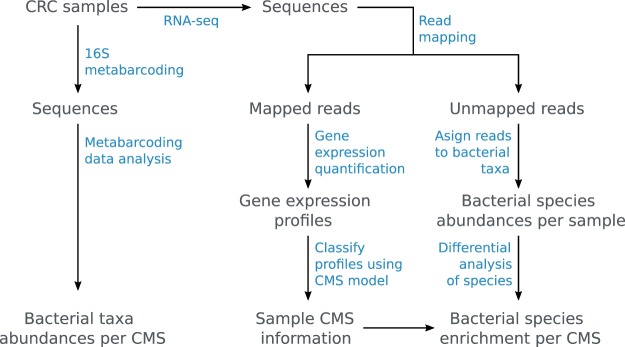

Here, we present a more condensed version of the methods that led to data and analyses in the primary publication14. The workflow is shown in Fig. 1 and the names of the partial processes (depicted in blue in the figure) are used as titles in this section to structure the text. We make the raw sequencing data freely available in NCBI Sequence Read Archive16, and scripts together with more downstream analysis results are accessible as the Zenodo dataset17.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of sample and data processing. Samples and data are shown in grey and processes highlighted in blue.

Sample collection & handling

Tumour tissue was collected from 34 patients undergoing surgery for resection of colorectal tumours. None of the patients had received chemotherapy prior to surgery, and all patients provided written, informed consent. This study was carried out with approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (ethics approval number: H16/037). Table 1 shows patient metadata for the cohort. At the time of surgery, CRC tumour cores were taken and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and initially stored at −80 °C. They were subsequently transferred to RNAlater ICETM (Qiagen), and equilibrated for at least 48 hours at −20 °C, prior to nucleic acid extraction. RNA and DNA were extracted from 15–20 mg each of tissue using RNEasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) and DNeasy Blood and Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen), respectively. Tissue disruption was carried out using a Retsch Mixer Mill. RNA extraction included a DNAse treatment step, and DNA extraction included overnight incubation with proteinase K, and treatment with RNAse A. Purified nucleic acids were quantified using the NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC, USA), and stored at −80 °C. Nucleic acids were extracted from all tumour samples in a single batch by one operator, to avoid inter-batch variation.

Table 1.

Patient metadata for Predict colorectal cancer cohort. Gender categories M for male and F for female are used; column stage is post-operative Tumour-Node-Metastasis staging; U/C in CMS column stands for unclassified; and N/A in the side column stands for data not available.

| SampleID | CMS | Age | Gender | Site | Side | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC_01 | CMS2 | 73 | M | Colon | Left | 1 |

| CRC_02 | U/C | 62 | F | Colon | Left | 3 |

| CRC_03 | U/C | 76 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_04 | CMS1 | 88 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_05 | U/C | 68 | F | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_06 | CMS3 | 63 | M | Colon | Right | 1 |

| CRC_07 | CMS2 | 81 | F | Colon | Left | 2 |

| CRC_08 | CMS2 | 74 | M | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_09 | CMS1 | 83 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_10 | CMS2 | 81 | M | Colon | Left | 1 |

| CRC_11 | CMS3 | 79 | F | Colon | Left | 3 |

| CRC_12 | CMS3 | 79 | F | Colon | Right | 1 |

| CRC_13 | CMS2 | 74 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_14 | U/C | 83 | M | Colon | Left | 2 |

| CRC_15 | CMS3 | 77 | F | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_16 | CMS3 | 84 | F | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_17 | U/C | 77 | M | Colon | Left | 3 |

| CRC_18 | CMS2 | 58 | M | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_19 | CMS2 | 77 | M | Colon | Left | 2 |

| CRC_20 | CMS3 | 74 | M | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_21 | CMS1 | 75 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_22 | CMS3 | 78 | F | Rectum | N/A | 3 |

| CRC_23 | CMS2 | 78 | F | Colon | Left | 2 |

| CRC_24 | CMS3 | 45 | F | Colon | Right | 1 |

| CRC_25 | CMS1 | 78 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_26 | U/C | 67 | M | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_27 | CMS1 | 75 | F | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_28 | CMS3 | 78 | M | Colon | Left | 1 |

| CRC_29 | CMS2 | 67 | M | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_30 | CMS2 | 80 | M | Colon | Left | 2 |

| CRC_31 | CMS2 | 74 | F | Colon | Right | 2 |

| CRC_32 | CMS2 | 68 | F | Colon | Left | 4 |

| CRC_33 | CMS2 | 80 | F | Colon | Right | 3 |

| CRC_34 | CMS1 | 81 | M | Colon | Right | 3 |

RNA-seq

Library preparation and ribosomal RNA depletion was carried out using Illumina TruSeq stranded total RNA library prep V1 and Ribo-Zero Gold. The ribosomal RNA depletion step has potentially removed a portion of bacterial ribosomal RNA alongside of the human one, hence losing some information on bacteria. However, the same method of depletion was used on all the samples thus the potential loss would effect all of them in a similar manner. RNA sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiSeq. 2500 V4 platform, to produce 125 bp paired end reads. Each sample library was split equally to two HiSeq lanes and the sequences from the two lanes were merged for each sample during the data processing phase.

Read mapping, Gene expression quantification, and Profile classification

Adapters and low quality segments were removed from the sequenced reads using fastq-mcf from EA Utils18 and SolexaQA++19. The cleaned reads were mapped to the GRCh38 reference human genome with STAR20 and the read count for each HAVANA annotated gene in every sample was calculated with htseq-count21. The read counts were transformed to gene expression profiles measured in transcripts-per-million (TPM) with DESeq222. The published CMS classifier15 was used to assign a molecular subtype of the disease to each sample based on the gene expression profiles (for more details see14). We identified six samples as CMS1, 13 samples as CMS2 and nine samples as CMS3. No samples were classified as CMS4, and six samples were unclassified.

Assignment of reads to bacterial taxa

A Kraken23 database was built containing all NCBI Refseq complete genomes or chromosome-level genomes (January 2017) and additional genomes of bacteria proposed to play a role in CRC, disregarding their genome status. The used bacterial genomes are listed in the files Supplementary_table_K1.xlsx (all complete and chromosome-level genomes) and Supplementary_table_K2.xlsx (of interest specifically for CRC) in the folder data/kraken of the accompanying repository. All RNA-seq reads that were not uniquely mapped to the human genome reference sequence were used as input to Kraken using this custom database for taxonomic classification per sample. Altogether, 2231 different bacterial species were detected in at least one sample and only 1.4% of the analysed reads were not assigned to any bacterial species. We visualised bacterial abundances per CRC subtype using Krona24 and the interactive plots are available at http://crc.sschmeier.com.

Differential analysis of bacterial species in CMS

We analysed the enrichment/depletion of bacterial species in one subtype compared to the other subtypes employing a strategy similar to differential expression analysis. Using edgeR25, we identified bacterial taxa with considerable abundance differences among the subtypes. For each CRC sample we used the assigned CMS subtype, the list of identified bacterial species, and the read counts corresponding to the identified species as input data. We treated all samples of a certain CMS subtype as replicates belonging to the subtype and ran differential analysis of each CMS subtype against all the other classified samples. This analysis identified bacterial species that are enriched (or depleted) in a subtype as compared to all other subtypes. For further details regarding the analysis, please refer to the primary publication14.

16S rRNA metabarcoding

Libraries containing 16S rRNA were prepared with 20 ng of DNA for each sample using primer pairs flanking the V3 and V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene and Illumina sequencing adaptors and barcodes were added using limited cycle PCR. Amplicon sequencing was carried out using the Illumina MiSeq platform, and paired end reads of length 250 bp were generated.

Metabarcoding data analysis

Short overlapping forward and reverse reads coming from the same fragment were joined together with FLASh26 to form sequences of the V3-V4 hypervariable 16S rRNA region. Afterwards, low quality regions were removed from the resulting fragments with SolexaQA++19. Microbiome analysis was carried out with the QIIME bioinformatics pipeline27 using the Greengenes database28 for taxonomy assignment. No further normalisation of the data was performed.

Data Records

Sequenced genomic data from both RNA-seq and 16S rRNA metabarcoding experiments are stored in the Sequence Read Archive as the study SRP11776316. Data resulting from the analyses presented here are located in the folder data of the Zenodo repository17. The data are separated into several subfolders:

The folder expr contains raw read counts in subfolder raw_counts, tpm-based expression profiles of all samples stored in file tpm.readyForClassifier.tsv and also file CMSclassifiedCRC.tpm.havana.tsv containing the CMS subtype classification. These files are the main outcomes of gene expression profile classifications.

Results of the metagenomics analysis of the non-human genomic content of RNA-seq are located in folder kraken together with two tables (Supplementary_table_K*.xlsx) containing lists of bacterial species used in this metagenomics analysis.

The folder 16S contains the biom file otu_table.biom resulting from the 16S rRNA metabarcoding analysis with QIIME and two partial abundance tables otu_table_sorted_*.txt.gz. The abundance tables are derived from the biom file and were used further for data visualisation in the primary publication as well as for the metagenomics method comparison.

Technical Validation

RNA-seq raw data quality

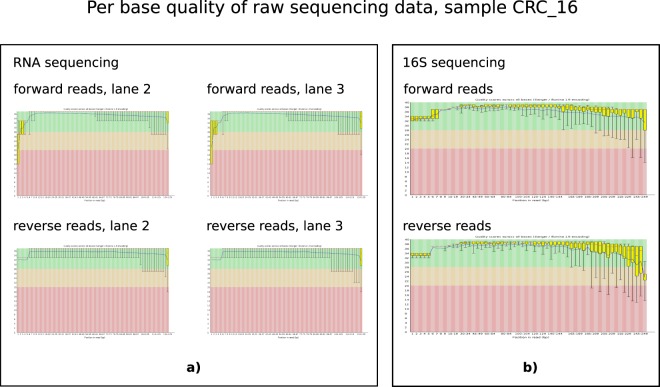

The quality of raw sequenced reads from RNA-seq experiments was assessed with FASTQC and was very good. A pair of representative per base quality plots of corresponding forward and reverse read pairs for one sample is shown in Fig. 2a). Regardless of the raw data quality, all the samples underwent routine data cleaning to ensure that no base was called with a Phred quality below 20. In Table 2, we show number of reads passing various data processing stages together with relative proportion of the reads passing two different stages.

Fig. 2.

Per base quality of raw sequencing data, sample CRC_16. Output of FASTQC: (a) RNA sequencing, (b) 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

Table 2.

RNAseq, read counts and their ratios in various data processing stages for each sample. N/A in the CRC_14 sample stands for data not available.

| sample ID | sequenced read pairs (count) | base quality ≥ 30 (in %) | cleaned read pairs (count) | cleaned in sequenced (in %) | uniquely mapped read pairs (count) | uniquely mapped in cleaned (in %) | fragments counted in expression profiles (count) | counted in mapped (in %) | read pairs for meta- genomics(count) | used for meta- genomics in cleaned (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC_01 | 10210344 | 92.99 | 8196630 | 80.28 | 7150347 | 87.24 | 5301615 | 74.14 | 1046283 | 12.76 |

| CRC_02 | 18195379 | 91.86 | 14099943 | 77.49 | 8953303 | 63.50 | 6339931 | 70.81 | 5146640 | 36.50 |

| CRC_03 | 17060748 | 92.86 | 13695754 | 80.28 | 11763192 | 85.89 | 8737708 | 74.28 | 1932562 | 14.11 |

| CRC_04 | 16113563 | 92.83 | 12984204 | 80.58 | 7771335 | 59.85 | 5515093 | 70.97 | 5212869 | 40.15 |

| CRC_05 | 12283116 | 92.70 | 9787847 | 79.69 | 8177368 | 83.55 | 6141780 | 75.11 | 1610479 | 16.45 |

| CRC_06 | 11889536 | 92.52 | 9444276 | 79.43 | 7689706 | 81.42 | 5485409 | 71.33 | 1754570 | 18.58 |

| CRC_07 | 16767600 | 92.77 | 13384614 | 79.82 | 11174494 | 83.49 | 8282768 | 74.12 | 2210120 | 16.51 |

| CRC_08 | 11692023 | 92.05 | 9148488 | 78.25 | 7211636 | 78.83 | 5370987 | 74.48 | 1936852 | 21.17 |

| CRC_09 | 12414326 | 91.96 | 9744352 | 78.49 | 4853350 | 49.81 | 3473194 | 71.56 | 4891002 | 50.19 |

| CRC_10 | 14196953 | 92.41 | 11216809 | 79.01 | 9659114 | 86.11 | 7307815 | 75.66 | 1557695 | 13.89 |

| CRC_11 | 11891786 | 92.48 | 9384672 | 78.92 | 5842764 | 62.26 | 4172474 | 71.41 | 3541908 | 37.74 |

| CRC_12 | 18376957 | 92.45 | 14448449 | 78.62 | 10438073 | 72.24 | 7535458 | 72.19 | 4010376 | 27.76 |

| CRC_13 | 16869568 | 92.16 | 13310571 | 78.90 | 11664960 | 87.64 | 8747487 | 74.99 | 1645611 | 12.36 |

| CRC_14 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CRC_15 | 13680558 | 90.83 | 10481777 | 76.62 | 5713010 | 54.50 | 4035523 | 70.64 | 4768767 | 45.50 |

| CRC_16 | 13982612 | 91.80 | 11035288 | 78.92 | 8867413 | 80.36 | 6509816 | 73.41 | 2167875 | 19.64 |

| CRC_17 | 16873883 | 92.10 | 13306336 | 78.86 | 9959970 | 74.85 | 7181815 | 72.11 | 3346366 | 25.15 |

| CRC_18 | 16663445 | 92.17 | 13179807 | 79.09 | 10641271 | 80.74 | 7400042 | 69.54 | 2538536 | 19.26 |

| CRC_19 | 3518434 | 91.50 | 2721238 | 77.34 | 1258917 | 46.26 | 727030 | 57.75 | 1462321 | 53.74 |

| CRC_20 | 13430061 | 91.98 | 10490785 | 78.11 | 1701669 | 16.22 | 1087471 | 63.91 | 8789116 | 83.78 |

| CRC_21 | 9845344 | 90.87 | 7491472 | 76.09 | 5741211 | 76.64 | 4272125 | 74.41 | 1750261 | 23.36 |

| CRC_22 | 15083803 | 91.89 | 11865373 | 78.66 | 10376744 | 87.45 | 7763574 | 74.82 | 1488629 | 12.55 |

| CRC_23 | 9427192 | 90.64 | 7169010 | 76.05 | 5663964 | 79.01 | 4216223 | 74.44 | 1505046 | 20.99 |

| CRC_24 | 11670754 | 90.49 | 8824150 | 75.61 | 6151634 | 69.71 | 4486074 | 72.92 | 2672516 | 30.29 |

| CRC_25 | 15947939 | 92.42 | 12533528 | 78.59 | 8487630 | 67.72 | 6353442 | 74.86 | 4045898 | 32.28 |

| CRC_26 | 14590462 | 91.97 | 11341012 | 77.73 | 9150589 | 80.69 | 6714043 | 73.37 | 2190423 | 19.31 |

| CRC_27 | 14302258 | 92.33 | 11333614 | 79.24 | 10074723 | 88.89 | 7531937 | 74.76 | 1258891 | 11.11 |

| CRC_28 | 11519270 | 91.74 | 9008972 | 78.21 | 7911036 | 87.81 | 5724147 | 72.36 | 1097936 | 12.19 |

| CRC_29 | 10106322 | 93.12 | 8158472 | 80.73 | 7401313 | 90.72 | 5458587 | 73.75 | 757159 | 9.28 |

| CRC_30 | 9323022 | 87.74 | 6502374 | 69.75 | 2697353 | 41.48 | 1445243 | 53.58 | 3805021 | 58.52 |

| CRC_31 | 16617530 | 92.22 | 13095067 | 78.80 | 11255164 | 85.95 | 8326092 | 73.98 | 1839903 | 14.05 |

| CRC_32 | 12418690 | 89.24 | 8994119 | 72.42 | 7557147 | 84.02 | 5644425 | 74.69 | 1436972 | 15.98 |

| CRC_33 | 15556518 | 92.15 | 12165032 | 78.20 | 10928495 | 89.84 | 8206798 | 75.10 | 1236537 | 10.16 |

| CRC_34 | 18455738 | 92.85 | 14793088 | 80.15 | 13219887 | 89.37 | 9995411 | 75.61 | 1573201 | 10.63 |

16S rRNA sequencing raw data quality

In Fig. 2b), we show quality of the 16S rRNA sequencing raw data for sample CRC_16. The other samples’ 16S rRNA quality plots looked similar. It can be seen that per base quality varied a little bit more along the 16S rRNA reads when compared to the RNA-seq reads, but overall the quality was very good for the 16S rRNA sequencing as well. Please note that the read length for the 16S rRNA sequencing was twice the read length of the RNA-seq, which together with differences between the used sequencing instruments explains differences in the quality plots. All the 16S rRNA samples underwent routine data cleaning to ensure that no base was called with a Phred quality below 20. In Table 3, we show number of reads passing various data processing stages together with relative proportion of the reads passing two different stages.

Table 3.

16S rRNA metabarcoding, read counts and their ratios in various data processing stages for each sample.

| sampleID | sequenced read pairs (count) | base quality ≥ 30 (in %) | cleaned fragments (count) | cleaned in sequenced (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC_01 | 333335 | 89.75 | 176823 | 53.05 |

| CRC_02 | 238221 | 92.15 | 126462 | 53.09 |

| CRC_03 | 356650 | 91.98 | 187474 | 52.57 |

| CRC_04 | 307676 | 92.35 | 165991 | 53.95 |

| CRC_05 | 261798 | 93.33 | 148547 | 56.74 |

| CRC_06 | 122630 | 92.36 | 67416 | 54.98 |

| CRC_07 | 175589 | 94.39 | 104310 | 59.41 |

| CRC_08 | 210849 | 93.22 | 119255 | 56.56 |

| CRC_09 | 238258 | 94.06 | 133700 | 56.12 |

| CRC_10 | 233536 | 92.30 | 129813 | 55.59 |

| CRC_11 | 291890 | 87.52 | 148406 | 50.84 |

| CRC_12 | 173621 | 93.14 | 96744 | 55.72 |

| CRC_13 | 204471 | 92.43 | 113588 | 55.55 |

| CRC_14 | 255851 | 92.52 | 141822 | 55.43 |

| CRC_15 | 254700 | 93.37 | 145899 | 57.28 |

| CRC_16 | 210014 | 94.06 | 126141 | 60.06 |

| CRC_17 | 197765 | 92.96 | 110784 | 56.02 |

| CRC_18 | 161324 | 92.88 | 90441 | 56.06 |

| CRC_19 | 147498 | 93.66 | 82425 | 55.88 |

| CRC_20 | 235318 | 92.33 | 127779 | 54.30 |

| CRC_21 | 169421 | 93.64 | 96627 | 57.03 |

| CRC_22 | 249364 | 93.55 | 144146 | 57.81 |

| CRC_23 | 171152 | 91.54 | 91281 | 53.33 |

| CRC_24 | 102066 | 91.90 | 54880 | 53.77 |

| CRC_25 | 334496 | 93.67 | 195656 | 58.49 |

| CRC_26 | 265504 | 93.22 | 150713 | 56.76 |

| CRC_27 | 69391 | 93.02 | 40037 | 57.70 |

| CRC_28 | 137873 | 91.43 | 74333 | 53.91 |

| CRC_29 | 176936 | 94.06 | 107348 | 60.67 |

| CRC_30 | 202971 | 94.46 | 118078 | 58.17 |

| CRC_31 | 220216 | 93.44 | 126807 | 57.58 |

| CRC_32 | 108880 | 93.34 | 61688 | 56.66 |

| CRC_33 | 219198 | 94.42 | 128793 | 58.76 |

| CRC_34 | 305438 | 93.88 | 178759 | 58.53 |

ISA-Tab metadata file

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Helen Morrin and the staff at the Cancer Society Tissue Bank, Christchurch for their enthusiasm and support for this project, the patients involved, for generously participating in this study, as well as New Zealand Genomics Limited (NZGL) for the sequencing and support in study design. Funding sources (Rachel Purcell): Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust, Gut Cancer Foundation (NZ), with support from the Hugh Green Foundation, Colorectal Surgical Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSSANZ).

Author Contributions

T.V. carried out bioinformatics analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. P.B. was involved in study design and data analysis. S.S. was involved in study design, bioinformatics analysis and was a contributor to manuscript preparation. F.F. was involved in study design and clinical aspects of the study. R.P. carried out nucleic acid and sequencing preparation of tumour samples and was a contributor to manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Code Availability

All the code used to process the genomic data is freely available as a part of the provided Zenodo repository17 and the code is located in the folder named scripts. The scripts folder also contains dependencies listed in the file used_packages_and_their_versions.tsv and the used parameter values listed in used_parameters.tsv. Depending on the scripts’ functionality, they are separated into various folders:

The folder rnaseq-subtype-classification contains scripts used for read mapping, gene expression quantification, and profile classification.

The folder kraken/human-unmapped contains scripts to assign reads to bacterial taxa.

The folder kraken/diff-expr-taxa contains scripts for differential analysis of bacterial species in CMS.

The folder 16S-metabarcoding contains scripts for metabarcoding data analysis.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ISA-Tab metadata

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0117-3.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in globocan 2012. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn J, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105:1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesi JR, et al. Towards the human colorectal cancer microbiome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Z, Guo B, Gao R, Zhu Q, Qin H. Microbiota disbiosis is associated with colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:20. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobhani I, et al. PLoS One. 2011. Microbial dysbiosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients; p. e16393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauch M, Lynch S. The potential for probiotic manipulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2012;23:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preidis GA, Versalovic J. Targeting the human microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics: gastroenterology enters the metagenomics era. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2015–2031. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta A, Khanna S. Fecal microbiota transplantation. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;318:102–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakatsu G, et al. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nature Communications. 2015;6:8727. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jass J. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2088–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Network CGA, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domingo E, et al. Use of multivariate analysis to suggest a new molecular classification of colorectal cancer. The Journal of Pathology. 2013;229:441–448. doi: 10.1002/path.4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purcell RV, Visnovska M, Biggs PJ, Schmeier S, Frizelle FA. Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:11590. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guinney J, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nature Medicine. 2015;21:1350. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.2017. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP117763

- 17.Schmeier S, Visnovska M, Biggs PJ, Purcell RV, Frizelle FA. 2018. Scripts and data attached to colorectal cancer study by Purcell, 2017. Zenodo. [DOI]

- 18.Aronesty Erik. Comparison of Sequencing Utility Programs. The Open Bioinformatics Journal. 2013;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.2174/1875036201307010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox MP, Peterson DA, Biggs PJ. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biology. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biology. 2014;15:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7:335. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2017. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP117763

- Schmeier S, Visnovska M, Biggs PJ, Purcell RV, Frizelle FA. 2018. Scripts and data attached to colorectal cancer study by Purcell, 2017. Zenodo. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the code used to process the genomic data is freely available as a part of the provided Zenodo repository17 and the code is located in the folder named scripts. The scripts folder also contains dependencies listed in the file used_packages_and_their_versions.tsv and the used parameter values listed in used_parameters.tsv. Depending on the scripts’ functionality, they are separated into various folders:

The folder rnaseq-subtype-classification contains scripts used for read mapping, gene expression quantification, and profile classification.

The folder kraken/human-unmapped contains scripts to assign reads to bacterial taxa.

The folder kraken/diff-expr-taxa contains scripts for differential analysis of bacterial species in CMS.

The folder 16S-metabarcoding contains scripts for metabarcoding data analysis.