Abstract

Introduction

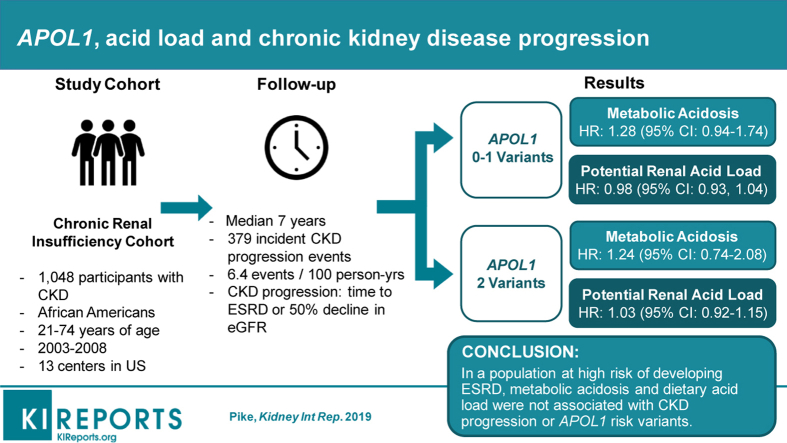

High dietary acid load and metabolic acidosis are associated with an accelerated decline in kidney function and may contribute to the observed heterogeneity in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) risk according to APOL1 genotype. Our objective was to examine the associations of metabolic acidosis and dietary acid load with kidney disease progression, according to APOL1 genotype, among individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Methods

We studied 1048 African American participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort. Metabolic acidosis was defined as blood levels of serum bicarbonate less than 22 mEq/L, and dietary acid load was quantified by potential renal acid load (PRAL) using data from the Diet Health Questionnaire. APOL1 status was defined as having 2 risk variants, consisting of either possible combination of the G1 and G2 risk alleles. We tested associations of APOL1 and dietary and metabolic acidosis with CKD progression, defined as time to ESRD or 50% decline in eGFR.

Results

During a median follow-up period of 7 years, 379 participants had an incident CKD progression event (6.4 events per 100 person-years). After full adjustment, among participants with 2 APOL1 variants, the analysis failed to detect an association between metabolic acidosis or dietary acid load and CKD progression (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96–1.11 per 1 mEq/L higher serum bicarbonate and an HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92–1.15 per 10 mEq/L higher PRAL). Similar associations were noted among participants without the APOL1 high-risk genotype.

Conclusion

In a population at high risk of developing ESRD, metabolic acidosis and dietary acid load were not associated with CKD progression.

Keywords: acidosis, APOL1, chronic kidney disease, dietary acid load, end-stage renal disease

Graphical abstract

See Commentary on Page 911

Blacks have a 3.7-fold higher prevalence and a 3-fold higher incidence of ESRD compared with whites.1, 2, 3 This disparity only partly is explained by known determinants of ESRD, including hypertension, diabetes, socioeconomic factors, and the presence of APOL1 risk variants.4, 5, 6, 7 Polymorphisms in APOL1, absent among whites, have been shown to increase the odds of developing ESRD in African Americans.8 APOL1 risk allele frequency estimates have been reported to be 21% (G1, composed of 2 missense variants), 13% (G2, in-frame deletion of 2 amino acids), and 13% with 2 high-risk alleles in African Americans.8 However, not all individuals carrying the risk alleles show evidence of kidney disease, suggesting that environmental risk factors may influence the biological effects of APOL1 on ESRD.2

Dietary acid load is a measure of balance between acid-inducing foods (e.g., animal sources of protein, metabolized to phosphorous and sulfate) and base-inducing foods (e.g., fruits and vegetables). High consumption of acid-inducing foods, along with diminished renal acid excretion, can induce metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate levels <22 mEq/L), which may be a risk factor for CKD progression. Observational studies have found that lower circulating bicarbonate levels and high dietary acid load are associated with adverse kidney outcomes, including a faster decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and higher risks of incident CKD and ESRD.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Among patients with CKD, dietary acid load is associated more strongly with risk for ESRD among blacks than among whites.15 However, a recent study suggested that the APOL1 high-risk genotype was associated more strongly with CKD progression among blacks with low net endogenous acid production (NEAP).16 We investigated whether the association of dietary acid load and metabolic acidosis on kidney disease progression is modified by APOL1 genotype among black participants within the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Dietary acid load and metabolic acidosis are modifiable risk factors that may be future targets for intervention and prevention for patients with a high-risk genotype.

Methods

Study Population

The CRIC Study was a prospective observational study of risk factors for progression of kidney and cardiovascular disease among 3939 individuals with CKD.17, 18 Participants were recruited between 2003 and 2008 at 13 centers across the United States and underwent extensive clinical evaluation at baseline and annual clinic visits and via telephone at 6-month intervals. The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.19

For this study, we restricted analyses to 1658 CRIC participants of self-reported black race. We further excluded participants who had an eGFR at baseline of less than 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 2), had missing APOL1 status (n = 129), or did not have available dietary data for analysis (n = 479), leaving a final analytic sample of 1048. Compared with participants with missing dietary data, our study population had a larger proportion of women, and fewer had diabetes and congestive heart failure at baseline.

Metabolic Acidosis

Serum bicarbonate (CO2) was measured using an enzymatic procedure with phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase on the Ortho Vitros (Raritan, NJ) platform at the University of Pennsylvania Core Laboratory. The total CO2 content includes serum bicarbonate as well as available forms of carbon dioxide. Serum bicarbonate comprises approximately 95% of the total CO2 content; thus, the serum CO2 measurement can be used as an estimator of serum bicarbonate.20 Circulating CO2 was evaluated dichotomously according to clinically relevant and previously published categories (i.e., <22 vs. ≥22 mEq/L [reference group], and continuously per mEq/L).

Dietary Acid Load

Food intake was quantified using the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire, a food frequency questionnaire administered at baseline and targeting the intake of 255 common food items over the past year.21, 22 Food intake data were converted into daily nutrient intake using Diet*Calc software (available: http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/DHQ/dietcalc).23

The PRAL and net endogenous acid production (NEAP) describe the acid load of an individual’s diet by estimating the production of nonvolatile acids and bases produced during digestion based on known nutritional content. We calculated the PRAL from dietary data using the Remer and Manz24, 25 equation as follows: (PRAL = 0.49 * protein [g] + 0.037 * phosphorus [mg] – 0.021 * potassium [mg] – 0.026 * magnesium [mg] – 0.013 * calcium [mg]). Participants were classified into quartiles (Q) by PRAL (Q1, < –12.8; Q2, –12.8 to –1.6; Q3, –1.5 to 9.3; and Q4, >9.3).

We estimated NEAP using the previously published equation: (NEAP = 54.5 * [dietary protein {g/d}/dietary potassium {mEq/d}] -10.2).26, 27 Participants were classified into quartiles by NEAP (Q1, <30.3; Q2, 30.3–39.3; Q3, 39.4–51.7; and Q4, >51.7).

Genotyping and APOL1 Risk Group Definition

Participants were genotyped for the APOL1 G1 (rs73885319 or rs60910145) and G2 (rs71785313) risk alleles using ABI TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). High-risk APOL1 status was defined as having 2 risk variants, consisting of either possible combination of the G1 and G2 risk alleles (i.e., G1/G1, G1/G2, or G2/G2 variants).

Outcomes

Kidney disease progression was defined as a 50% reduction in eGFR from baseline using the CKD–Epidemiology Collaboration (EPI) equation,28 or the development of ESRD (initiation of dialysis therapy or kidney transplantation) during follow-up evaluation until June 30, 2009. ESRD was ascertained through active follow-up evaluation and linkage of the cohort with the US Renal Data System.

Measurement of Covariates

Demographic information, medical history, medication use in the past 30 days, height, weight, and blood pressure were collected at baseline by questionnaire and examination. Diabetes was defined at baseline by a fasting blood glucose level of 126 mg/dl or greater or use of diabetic medications. Urine albumin and creatinine concentrations from a 24-hour urine sample were measured at a central laboratory using standard assays. Baseline levels of serum creatinine were used for estimation of eGFR using the CKD-EPI equation.28

Ancestry-informative genetic markers were based on the IBC Illumina chip array panel (San Diego, CA). A total of 1053 ancestry-informative markers, shared between the genotyping platform and HapMap3 reference panel, were used to derive global African continental genetic ancestry measures.29

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were tabulated with respect to categories of serum bicarbonate. Unadjusted incidence rates were calculated as the number of events divided by person-years at risk. Participants were considered at risk from the date of their baseline examination until the first occurrence of kidney disease progression, death, or their data were censored owing to loss of follow-up evaluation or end of data collection on June 30, 2009.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to test for APOL1 genotype status-specific associations of serum bicarbonate (categorically as <22 vs. ≥22 mEq/L and continuously per mEq/L), and PRAL (in study-specific quartiles and continuously per 10 mEq/d) with the relative hazard of CKD progression. Subgroup-specific HRs were calculated via linear combination of regression coefficients for main effect and cross-product terms. Analyses completely stratified by APOL1 variant status yielded similar results.

Covariates for adjustment were chosen a priori based on the suspicion that they may confound the association between acid load and CKD progression. The first model included age at enrollment, sex, and the percentage of African ancestry. The second model added education (< high school, high school, or higher), income, body mass index (in kg/m2), baseline eGFR, prevalent diabetes, smoking status (current, former/never), history of cardiovascular disease, and 24-hour urine albumin to creatinine ratio (log-transformed). Models examining PRAL additionally adjusted for the total caloric intake (kcal/kg per d, log-transformed).

Functional forms of the APOL1 genotype-specific associations of serum bicarbonate and PRAL with the hazard of CKD progression were examined graphically using adjusted penalized smoothing splines with evenly spaced knots among the inner 97.5% of serum bicarbonate or PRAL concentrations.

Multiplicative interactions were tested by the Wald test of a product term between APOL1 genotype and serum bicarbonate or PRAL. We also tested for departure from an additivity of effects of APOL1 genotype and serum bicarbonate by the relative excess risk owing to interaction.30 The 95% CI of the relative excess risk owing to interaction was calculated as proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow.31 Because associations of APOL1 and CKD progression are reported to differ by diabetes status, analyses were repeated with stratification by diabetes at baseline.

The CRIC Study enrolled 3939 participants, of whom 1048 met our inclusion criteria. Given 281 CKD progression events in the subgroup of participants with 0 to 1 APOL1 high-risk variants, at a type 1 error rate of 5%, we estimated that we had 77%, 91%, and 97% power to detect HRs of 1.2, 1.25, and 1.3, respectively. In the subgroup of participants with 2 high-risk genotypes, we had 62%, 74%, and 83% power to detect HRs of 1.3, 1.35, and 1.4, respectively.

The nominal level of significance was defined as a P value less than 0.05 (2-sided). All analyses were conducted using Stata Version 14.2 (College Station, TX)32 and R version 3.4.1 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant Characteristics

At baseline, the mean age and eGFR were 59 years (SD, 10.5 yr) and 44.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD, 15.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2), respectively. Approximately 20% of the study population had 2 APOL1 risk variants. The mean PRAL was -1.9 mEq/d (SD, 21.4 mEq/d), serum bicarbonate was 24.8 mEq/L (SD, 3.3 mEq/L), and NEAP was 41.9 mEq/d (SD, 16.8 mEq/d). PRAL and NEAP were highly correlated with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.88. Serum bicarbonate also was correlated inversely and weakly with PRAL and NEAP (correlation coefficients, –0.07 and -0.06, respectively).

Participants in the lowest category of serum bicarbonate (CO2 < 22 mEq/L) had a lower body mass index, lower eGFR, and were more likely to be current smokers and have heavy albuminuria (Table 1). NEAP was similar across categories of serum bicarbonate, and participants with the lowest serum bicarbonate levels had higher PRAL (Supplementary Table S1), with a mean of 1.2 (SD, 22.1) compared with -2.6 (SD, 21.3) in those with the highest levels of serum bicarbonate.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by category of serum bicarbonate

| N | Total |

CO2 < 22 mEq/L |

CO2 ≥ 22 mEq/L |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1048 | 163 | 876 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (yr) | 58.5 (10.5) | 57.2 (11.1) | 58.8 (10.4) |

| Female sex | 568 (54.2) | 90 (55.2) | 473 (54.0) |

| Education: high school graduate | 793 (75.7) | 120 (73.6) | 668 (76.3) |

| Income | |||

| <$20,000 | 391 (37.3) | 84 (51.5) | 301 (34.4) |

| $20,001–$50,000 | 279 (26.6) | 29 (17.8) | 248 (28.3) |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 147 (14.0) | 17 (10.4) | 129 (14.7) |

| >$100,000 | 47 (4.5) | 7 (4.3) | 40 (4.6) |

| Do not wish to answer | 184 (17.6) | 26 (16.0) | 158 (18.0) |

| Current smoker | 202 (19.3) | 48 (29.4) | 151 (17.2) |

| African ancestry, n (%) | 77.3 (9.3) | 77.3 (8.8) | 77.3 (9.5) |

| Clinical values | |||

| Body mass index | 33.5 (8.1) | 31.8 (8.1) | 33.9 (8.1) |

| uACR | |||

| <30 | 410 (40.4) | 38 (23.8) | 366 (43.3) |

| 30–300 | 272 (26.8) | 52 (32.5) | 219 (25.9) |

| >300 | 333 (32.8) | 70 (43.8) | 261 (30.9) |

| eGFR | 44.0 (15.0) | 34.6 (13.5) | 45.7 (14.7) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 132.4 (22.9) | 132.3 (23.0) | 132.4 (22.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 73.6 (13.6) | 72.4 (12.6) | 73.7 (13.9) |

| APOL1 status | |||

| 0–1 risk variants | 837 (79.9) | 127 (77.9) | 702 (80.1) |

| 2 risk variants | 211 (20.1) | 36 (22.1) | 174 (19.9) |

| Dietary characteristics | |||

| Potential renal acid load (mEq/d) | -1.9 (21.4) | 1.2 (22.1) | -2.6 (21.3) |

| Protein (g/d) | 69.4 (38.3) | 67.8 (42.4) | 69.7 (37.7) |

| Phosphorous (mg/d) | 1111.3 (539.9) | 1084.9 (538.0) | 1115.6 (541.1) |

| Potassium (mg/d) | 2913.0 (1390.4) | 2711.5 (1266.5) | 2953.6 (1412.8) |

| Magnesium (mg/d) | 301.8 (140.6) | 286.7 (132.7) | 304.5 (141.8) |

| Calcium (mg/d) | 659.2 (362.2) | 634.4 (346.5) | 663.1 (364.5) |

| Total energy intake (kcal/kg per d) | 20.7 (11.2) | 21.5 (11.4) | 20.5 (11.1) |

| Total protein intake (g/kg per d) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.4) |

| Net endogenous acid production (mEq/d) | 41.9 (16.8) | 43.8 (18.2) | 41.4 (16.5) |

| Comorbidities/medications | |||

| Stroke | 145 (13.8) | 25 (15.3) | 120 (13.7) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 398 (38.0) | 56 (34.4) | 340 (38.8) |

| Heart failure | 128 (12.2) | 17 (10.4) | 110 (12.6) |

| Anti-acidosis medications | 11 (1.1) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (0.9) |

| Diabetes | 525 (50.1) | 81 (49.7) | 441 (50.3) |

| Hypertension | 978 (93.3) | 156 (95.7) | 813 (92.8) |

APOL1, apolipoprotein 1; CO2, serum bicarbonate; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; uACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Means (±SD) or N (%) are shown.

APOL1 Risk Variants and CKD Progression

Over a median follow-up period of 6.6 years (range, 0.1–9.7 yr), 379 participants experienced CKD progression, yielding an incidence rate of 6.4 cases per 100 person-years. Among participants with 2 APOL1 risk variants, the incidence rate of CKD progression was 8.4 per 100 person-years; among those with 0 to 1 risk variants, the incidence rate was 5.9 per 100 person-years (Supplementary Table S2).

Serum Bicarbonate and Outcomes

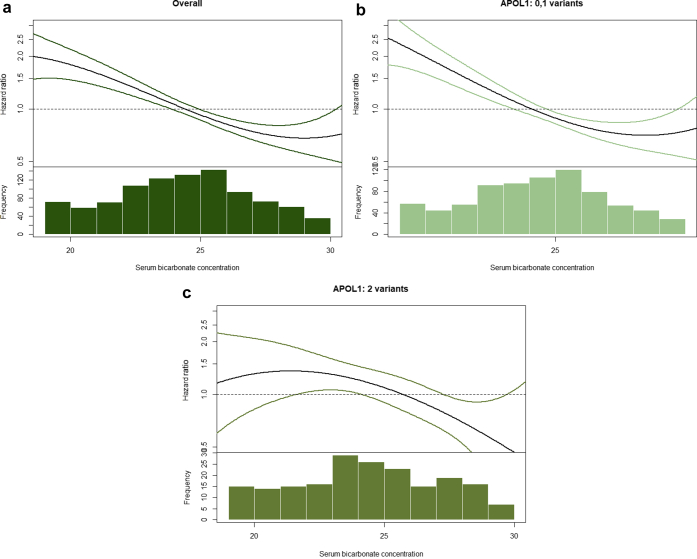

Circulating serum bicarbonate levels less than 22 mEq/L were associated with CKD progression, relative to a serum bicarbonate level greater than 22 mEq/L, after adjustment for age, sex, and African ancestry (model 1), in both APOL1 genotype subgroups; HRs were 2.28 (95% CI, 1.72–3.03) and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.17–3.17) among individuals with 0 to 1 and 2 APOL1 risk variants, respectively (Table 2). Associations were attenuated in model 2, and the 95% CI no longer excluded the null (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.94–1.74 and HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.74–2.08) among individuals with 0 to 1 and 2 risk APOL1 variants, respectively. The magnitude of associations was similar comparing participants with 0 to 1 risk variants with those with 2 risk variants (P value for multiplicative interaction = 0.736, P value for additive interaction = 0.98) (Table 2). An evaluation of the association of serum bicarbonate with risk of CKD progression using splines showed similar findings (Figure 1). Results were similar when examining serum bicarbonate continuously (Table 2) and when stratifying by diabetes at baseline (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Number of events, incidence rates, and HRs with 95% CIs for serum bicarbonate in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort

| N | Events, n | Incidence ratea | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI)b | Model 2 HR (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||||

| <22 mEq/L | 163 | 86 | 12.1 | 2.12 (1.67–2.70) | 2.20 (1.72–2.81) | 1.25 (0.95–1.64) |

| ≥22 mEq/L | 876 | 290 | 5.6 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Per mEq/L | – | – | – | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) |

| APOL1: 0–1 risk variants | ||||||

| <22 mEq/L | 127 | 66 | 11.7 | 2.24 (1.70–2.96) | 2.28 (1.72–3.03) | 1.28 (0.94–1.74) |

| ≥22 mEq/L | 702 | 215 | 5.1 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Per mEq/L | – | – | – | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) | 0.91 (0.87–0.94) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) |

| APOL1: 2 risk variants | ||||||

| <22 mEq/L | 36 | 20 | 13.5 | 1.74 (1.06–2.86) | 1.92 (1.17–3.17) | 1.24 (0.74–2.08) |

| ≥22 mEq/L | 174 | 75 | 7.6 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Per mEq/L | – | – | – | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.94 (0.88–0.99) | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) |

| P for interaction | 0.495 | 0.736 | 0.715 | |||

APOL1, apolipoprotein 1; CI, confidence interval; CO2, serum bicarbonate; HR, hazard ratio.

HRs and 95% CIs were derived from Cox proportional hazard models.

Per 100 person-years.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, and percentage of African ancestry.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, percentage of African ancestry, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, income, education, estimated glomerular filtration rate, 24-hour albumin to creatinine ratio, smoking, and history of cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Association between overall serum bicarbonate concentrations (a), serum bicarbonate concentrations in participants with 0 to 1 APOL1 risk variants (b), and serum bicarbonate concentrations in participants with 2 APOL1 risk variants with the hazard of chronic kidney disease progression (c). Adjusted penalized smoothing splines with evenly spaced knots were used.

Potential Renal Acid Load, NEAP, and Outcomes

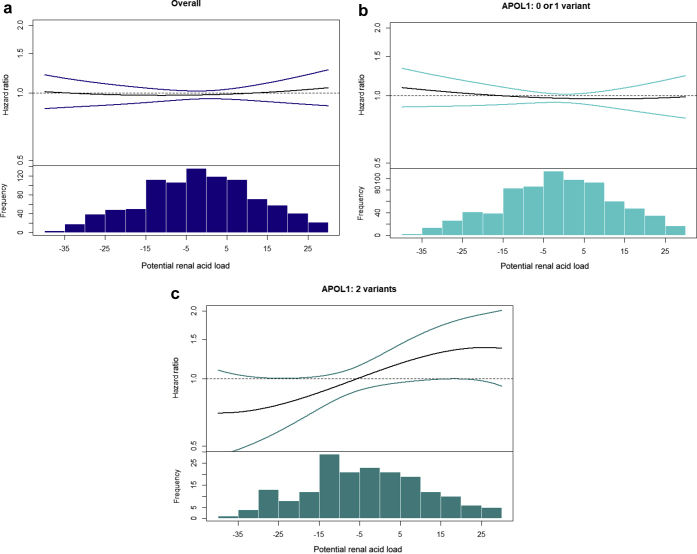

Participants with higher PRAL were more likely to be older, male, and current smokers (Supplementary Table S1). PRAL was not associated with CKD progression in either APOL1 genotype subgroup (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93–1.04 and HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92–1.15) per 10 mEq/L higher PRAL, among individuals with 0 to 1 and 2 APOL1 variants, respectively (Table 3). However, visual inspection of the splines suggested that a higher PRAL may be associated more strongly with the risk of CKD progression among participants with 2 APOL1 variants (Figure 2). Similar findings were noted for NEAP (data not shown).

Table 3.

Number of events, incidence rates, and HRs with 95% CIs for potential renal acid load in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort

| N | Events, n | Incidence ratea | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI)b | Model 2 HR (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRAL | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||

| Q1 | 262 | 87 | 5.9 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Q2 | 262 | 96 | 6.4 | 1.09 (0.81–1.45) | 1.10 (0.82–1.48) | 1.01 (0.74–1.38) |

| Q3 | 262 | 93 | 6.2 | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) | 0.96 (0.71–1.30) | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) |

| Q4 | 262 | 103 | 7.2 | 1.23 (0.92–1.63) | 1.06 (0.79–1.43) | 1.01 (0.74–1.38) |

| Per 10 mEq/d | – | – | – | 1.02 (0.98–1.08) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| APOL1: 0–1 risk variants | ||||||

| Q1 | 204 | 66 | 5.6 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Q2 | 208 | 75 | 6.4 | 1.14 (0.82–1.59) | 1.13 (0.81–1.59) | 1.05 (0.74–1.50) |

| Q3 | 215 | 70 | 5.5 | 0.99 (0.71–1.39) | 0.91 (0.65–1.30) | 0.96 (0.67–1.38) |

| Q4 | 210 | 72 | 6.2 | 1.11 (0.79–1.55) | 0.97 (0.69–1.37) | 0.92 (0.64–1.32) |

| Per 10 mEq/d | – | – | – | 1.01 (0.95–1.06) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) |

| APOL1: 2 risk variants | ||||||

| Q1 | 58 | 21 | 6.9 | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Q2 | 54 | 21 | 6.4 | 0.92 (0.50–1.68) | 0.99 (0.53–1.85) | 0.88 (0.47–1.65) |

| Q3 | 47 | 23 | 9.4 | 1.34 (0.74–2.42) | 1.20 (0.66–2.21) | 0.67 (0.36–1.26) |

| Q4 | 52 | 31 | 11.7 | 1.67 (0.96–2.90) | 1.48 (0.83–2.63) | 1.33 (0.74–2.41) |

| Per 10 mEq/d | – | – | – | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) |

| P for interaction | 0.086 | 0.109 | 0.384 | |||

APOL1, apolipoprotein 1; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PRAL, potential renal acid load; Q, quartile.

HRs and 95% CIs were derived from Cox proportional hazard models. Q1, <12.97 mEq/d; Q2, −12.97 to −1.881 mEq/d; Q3, −1.880 to 8.96 mEq/d; and Q4, >8.96 mEq/d.

Per 100 person-years.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, and percentage of African ancestry.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, percentage of African ancestry, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, income, education, estimated glomerular filtration rate, 24-hour albumin to creatinine ratio, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, and kilocalories per weight per day.

Figure 2.

Association between overall potential renal acid load (PRAL) concentrations (a), PRAL concentrations in participants with 0 to 1 APOL1 risk variants (b), and PRAL concentrations in participants with 2 APOL1 risk variants with the hazard of chronic kidney disease progression (c). Adjusted penalized smoothing splines with evenly spaced knots were used.

Discussion

Among a cohort of African Americans at high risk for ESRD, acidosis was associated with CKD progression in crude but not in fully adjusted analyses. The magnitude of associations was small and generally similar across APOL1 risk variant groups, although associations of PRAL trended stronger among individuals with 2 APOL1 variants compared with those with 0 or 1. These findings add to the growing body of literature examining gene–environment interactions or second-hit factors in the risk of ESRD associated with high-risk APOL1 variants.

The association between APOL1 high-risk genotype and ESRD is well established. Blacks with 2 APOL1 risk variants have a 2- to 6-fold higher odds of developing ESRD.8 In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, carrying 2 risk alleles was associated with a faster decline in eGFR and a higher risk of developing CKD and ESRD.33 Similarly, among individuals with CKD, black patients in the APOL1 high-risk group have higher risks of renal outcomes and a faster decline in eGFR.29 Although the APOL1 high-risk genotype has been shown to be associated with a higher risk of ESRD, unexplained variance remains. In a recent gene-by-APOL1 association study, Langefeld et al.34 found no interactions between APOL1 risk variants and any single-nucleotide polymorphism, suggesting that APOL1 and environmental interactions may be of greater importance.

Previously, in a study of CRIC participants of all race/ethnicities, Dobre et al.35 reported that the risk of developing a renal end point was lower with a higher serum bicarbonate level. In another cohort study of 1781 participants from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study, Menon et al.36 found that a lower serum bicarbonate level was associated with an increased risk of long-term outcomes in nondiabetic patients with CKD. In our study, consistent with previous studies but restricted to participants of black race, CKD progression incidence rates were higher among participants with metabolic acidosis. However, after full adjustment for potential confounders, including baseline kidney function, the analysis failed to detect an association between metabolic acidosis and CKD progression, overall or within APOL1 risk variant groups. Because eGFR is associated very strongly with both serum bicarbonate levels and CKD progression, adjustment for this factor attenuated the magnitude of the HR and rendered the estimate no longer statistically significant; our study lacked the statistical power necessary to detect an effect of this magnitude.

Dietary acid load is a modifiable risk factor that has been shown to be associated with CKD and ESRD. In a study of 15,055 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, Rebholz et al.10 found that a higher dietary acid load (PRAL and NEAP) was associated with a higher risk of incident CKD. Similarly, among individuals with CKD in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, a higher dietary acid load, measured by net acid excretion, was associated with a higher risk of ESRD and this association was stronger among blacks than among whites.15, 37 In the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension, a higher NEAP was associated with a more rapid decline in kidney function.14 In healthy individuals, an increase in dietary acid load was accompanied by an increase in urinary ammonia excretion. Among persons with CKD, however, lower acid excretion was more likely a reflection of the impaired ability of the kidney to excrete ammonia than of a decreased acid load. Along these lines, in a previous analysis within CRIC, higher net acid excretion, examined in 980 participants using urinary biomarkers, was associated with a lower risk of ESRD among participants with diabetes.38 Similarly, among participants from the Nephro Test cohort, a lower urinary ammonia level was associated with a higher risk of CKD progression.39

Visual inspection of the associations of dietary acidosis raise the possibility of differential effects of PRAL on CKD progression according to APOL1 genotype. Although we cannot be certain, in our study the lack of a statistical interaction between APOL1 variants, PRAL, and CKD progression may have been owing to limited statistical power. It would be premature to conclude that dietary modification may be particularly beneficial among individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes. High consumption of acid-inducing foods can induce metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate levels ≤22 mEq/L), which, among CKD patients, is a risk factor for disease progression, bone loss, and muscle wasting. Small single-center randomized trials have shown benefits of alkali therapy (sodium bicarbonate or a diet high in fruits and vegetables), even in patients with normal serum bicarbonate levels, on progression of CKD, bone health, and general nutritional status.40, 41, 42, 43 In a recent randomized trial of 20 adults with moderate CKD and a moderate serum bicarbonate concentration, Scialla et al.44 found that treatment with sodium bicarbonate had a strong effect on the tricarboxylic acid cycle and additional effects on propanoate metabolism, pyruvate, and branched-chain amino acid metabolism. From these findings, the investigators suggested that sodium bicarbonate treatment may be beneficial in a population with CKD. Dietary acid load and metabolic acidosis are modifiable risk factors that could be used to increase the focus on individuals with the highest risk of ESRD and may be important for developing individualized interventions to reduce ESRD risk in African Americans. Although our study did not find a significant association between dietary acid load and CKD progression, further research is needed to examine the relationship between dietary acid load and APOL1.

This study examined the association between APOL1 risk variants, metabolic acidosis, dietary acid load, and ESRD. Strengths of our study included the prospective design and the unique cohort of individuals with a high risk of ESRD. Another important strength of this study was the ascertainment of acid load using a validated measure (i.e., the Diet Health Questionnaire23). Although we were powered to detect subgroup-specific associations ranging from 1.2 to 1.3, our study had limited power to detect associations of such small magnitude. The CKD progression rate in CRIC is slower than would be expected for a cohort with these comorbidities and clinical characteristics.45, 46 It is possible that the frequent follow-up evaluations and criteria for entry drew patients with a more favorable prognoses into the CRIC study. An additional limitation was that dietary acid load was calculated from self-reported food frequency questionnaire results, which may not reflect intake. Kidney dysfunction at baseline, in combination with measuring dietary and metabolic acidosis at a single time point, impeded us from fully elucidating the interplay, through time, of changes in diet and the progression of CKD. Although we attempted to alleviate this concern by adjusting for measured subclinical disease and baseline kidney function, a fully comprehensive view of the time course of CKD progression and changes in diet over time would be ideal.

In conclusion, in a population at particularly high risk for ESRD, the associations between metabolic acidosis, dietary acidosis, and CKD progression were inconclusive. If there truly are differences in the population in the association of acidosis and CKD progression between APOL1 variant groups, they are likely to be small. We were underpowered to detect the very small differences in associations between groups in our sample; the clinical relevance of such small differences is unclear. As such, whether dietary acid load and metabolic acidosis should be targets for future interventions in those at the highest risk of ESRD has yet to be determined. These observations do motivate future larger studies of individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes to better evaluate and assess risk factors for ESRD.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants K01DK109019 (C.R.-C.), CTSA award TL1TR002244 (M.P.), and VA Merits MVP-BX003360 and CX000982 (A.H.), and 1I01CX000414 (T.A.I.).

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study was conducted by the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Investigators and was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases. The data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study reported here were supplied by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases Central Repositories. This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with Investigators of the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases Central Repositories, or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Table S1. Baseline characteristics by quartiles of potential renal acid load. Means (±SD) or N (%) are shown.

Table S2. Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for serum bicarbonate in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.

Table S3. Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for potential renal acid load in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

Baseline characteristics by quartiles of potential renal acid load. Means (±SD) or N (%) are shown.

Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for serum bicarbonate in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.

Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for potential renal acid load in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2017 Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 2.Klein J.B., Nguyen C.T., Saffore L. Racial disparities in urologic health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins D., Tareen N., Norris K.C. The epidemiology of end-stage renal disease among African Americans. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipworth L., Mumma M.T., Cavanaugh K.L. Incidence and predictors of end stage renal disease among low-income blacks and whites. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClellan W.M., Warnock D.G., Judd S. Albuminuria and racial disparities in the risk for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1721–1728. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholas S.B., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Norris K.C. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:6–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman B.I., Skorecki K. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in apolipoprotein L1 gene-associated nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2006–2013. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01330214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genovese G., Friedman D.J., Ross M.D. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goraya N., Wesson D.E. Is dietary acid a modifiable risk factor for nephropathy progression? Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:142–144. doi: 10.1159/000358602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebholz C.M., Coresh J., Grams M.E. Dietary acid load and incident chronic kidney disease: results from the ARIC study. Am J Nephrol. 2015;42:427–435. doi: 10.1159/000443746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee T., Crews D.C., Wesson D.E. Dietary acid load and chronic kidney disease among adults in the United States. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanda E., Ai M., Kuriyama R. Dietary acid intake and kidney disease progression in the elderly. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:145–152. doi: 10.1159/000358262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebholz C.M., Tin A., Liu Y. Dietary magnesium and kidney function decline: the healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span study. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:381–387. doi: 10.1159/000450861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scialla J.J., Appel L.J., Astor B.C. Net endogenous acid production is associated with a faster decline in GFR in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2012;82:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crews D.C., Banerjee T., Wesson D.E. Race/ethnicity, dietary acid load, and risk of end-stage renal disease among US Adults with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47:174–181. doi: 10.1159/000487715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen T.K., Choi M.J., Kao W.H. Examination of potential modifiers of the association of APOL1 alleles with CKD progression. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2128–2135. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05220515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman H.I., Appel L.J., Chertow G.M. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study: design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S148–S153. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070149.78399.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lash J.P., Go A.S., Appel L.J. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1302–1311. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centor R.M. Serum total carbon dioxide. In: Walker H.K., Hall W.D., Hurst J.W., editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diet History Questionnaire, Version 1.0. National Institutes of Health, Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program, National Cancer Institute; 2007.

- 22.Thompson F.E., Subar A.F., Brown C.C. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: results of an experimental validation study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:212–225. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diet∗Calc Analysis Program, Version 1.4.3. National Cancer Institute, Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program; 2005.

- 24.Remer T., Manz F. Estimation of the renal net acid excretion by adults consuming diets containing variable amounts of protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1356–1361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.6.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remer T., Manz F. Potential renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:791–797. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frassetto L.A., Lanham-New S.A., Macdonald H.M. Standardizing terminology for estimating the diet-dependent net acid load to the metabolic system. J Nutr. 2007;137:1491–1492. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frassetto L.A., Todd K.M., Morris R.C., Jr., Sebastian A. Estimation of net endogenous noncarbonic acid production in humans from diet potassium and protein contents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:576–583. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsa A., Kao W.H., Xie D. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183–2196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson D.B., Kaufman J.S. Estimation of the relative excess risk due to interaction and associated confidence bounds. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:756–760. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S. Confidence interval estimation of interaction. Epidemiology. 1992;3:452–456. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: release 14.2 ed. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster M.C., Coresh J., Fornage M. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1484–1491. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langefeld C.D., Comeau M.E., Ng M.C.Y. Genome-wide association studies suggest that APOL1-environment interactions more likely trigger kidney disease in African Americans with nondiabetic nephropathy than strong APOL1-second gene interactions. Kidney Int. 2018;94:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobre M., Yang W., Chen J. Association of serum bicarbonate with risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD: a report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:670–678. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menon V., Tighiouart H., Vaughn N.S. Serum bicarbonate and long-term outcomes in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:907–914. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banerjee T., Crews D.C., Wesson D.E. High dietary acid load predicts ESRD among adults with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1693–1700. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scialla J.J., Asplin J., Dobre M. Higher net acid excretion is associated with a lower risk of kidney disease progression in patients with diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017;91:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallet M., Metzger M., Haymann J.P. Urinary ammonia and long-term outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88:137–145. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Brito-Ashurst I., Varagunam M., Raftery M.J., Yaqoob M.M. Bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2075–2084. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goraya N., Simoni J., Jo C.H., Wesson D.E. A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:371–381. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02430312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goraya N., Simoni J., Jo C.H., Wesson D.E. Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1031–1038. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahajan A., Simoni J., Sheather S.J. Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2010;78:303–309. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scialla J.J., Brown L., Gurley S. Metabolic changes with base-loading in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1244–1246. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01830218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright J.R., Jr., Bakris G., Greene T. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H.W., Park J.T., Yoo T.H. Urinary potassium excretion and progression of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:330–340. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07820618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Baseline characteristics by quartiles of potential renal acid load. Means (±SD) or N (%) are shown.

Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for serum bicarbonate in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.

Number of events, incidence rates, and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for potential renal acid load in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort stratified by diabetes.