Abstract

This commentary wishes to highlight the latest discoveries in the mutant p53 field that have been discussed in the 8th p53 Mutant Workshop 2019, held in Lyon. TP53 mutant (mutp53) proteins are involved in the pathogenesis of most human cancers. Mutp53 proteins not only lose wild-typ53 function but, in some circumstances, may acquire novel oncogenic functions, namely gain-of-function (GOF), which lead to aberrant cell proliferation, chemoresistance, disruption of tissue architecture, migration, invasion and metastasis. Decoding the TP53 mutational spectrum and mutp53 interaction with additional transcription factors will therefore help to developing and testing novel and hopefully more efficient combinatorial therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: p53, Li-Fraumeni, Small molecules, Mutant p53 reactivation, Exosomes, miRNA, Cancer-associated fibroblasts

Background

TP53 is the most frequently inactivated tumor suppressor gene in tumors, being mutated in over 50% of human cancer types and indirectly inactivated in many others. The loss of TP53 as a signature driver of human cancers is unquestionable. Loss of p53 tumor suppressor functions induces accumulation of genomic alterations culminating in cancer progression, however, other than loosing wild-type (wt) oncosuppressor function, some mutant p53 (mutp53) proteins may acquire new oncogenic functions, namely gain-of-function (GOF), associated with altered p53-dependent transcriptional programs [1]. In addition, mutp53 interplay with other oncogenic transcription factors may profoundly alter the cancer genome and secretome dictating tumor progression even through remodelling of the tumor microenvironment [2]. The 8th p53 Mutant Workshop 2019 held in Lyon 15–18 May, has been the occasion to come across to the latest discoveries in the mutant p53 field. This occurred in a very special time for p53 studies since the Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) was first described in 1969 and p53 itself came into being in 1979 while mutant p53 was recognized as a major event in cancer in 1989. Therefore, in this triple anniversary great progresses into understanding the multiple aspects of mutant p53 proteins can be underscored and, most importantly, how to exploit them in the next decades to target cancers with mutp53 accumulation (Fig. 1).

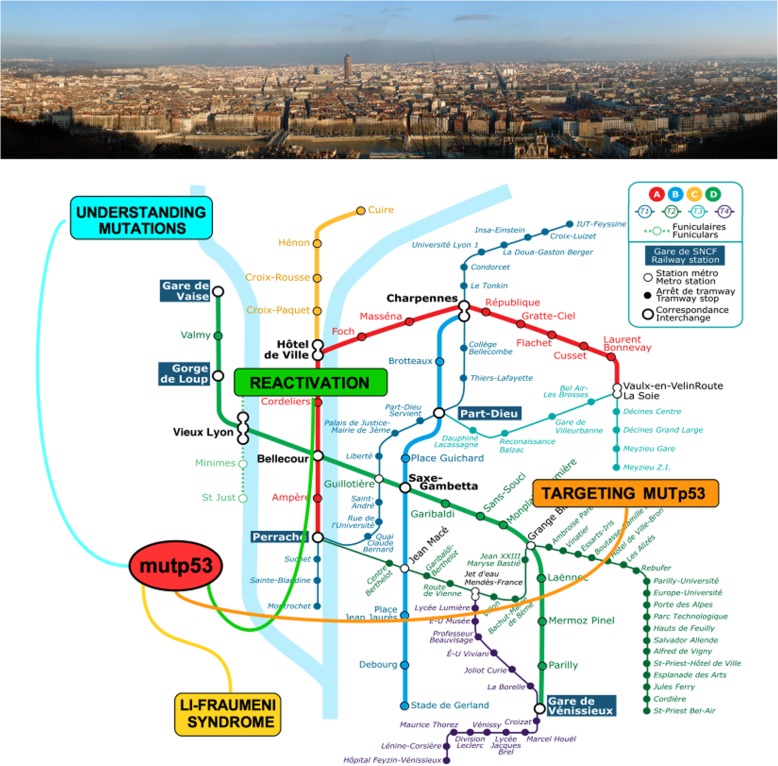

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the ongoing research in the mutp53 field. The Lyon’s map as a framework to show the crucial hub of mutp53 at the crossroads of many interventions aimed at understanding its mutational status, and the way to reactivate it for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes

Important insight into the p53 field come from the Li-Fraumeni syndrome that was first described in 1969 as a highly penetrant cancer-prone syndrome inducing sarcoma, breast cancer, adrenocortical carcinoma, and brain tumors, often with more than one cancer per affected individual. More than 85% of patients with LFS harbour germline TP53 mutations that profoundly affect the onset of the disease. In the years, the whole-exome and whole-genome testing allowed to sequence germline and somatic DNA leading to the beginning of precision medicine initiatives in LFS [3]. Although the clinical characteristics and molecular basis for LFS are now clear, no universally accepted approach exists for risk management. To this aim, recent studies showed that whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) may play a role in surveillance of this high-risk population and, more importantly, may help in localizing malignant tumors in childhood. Therefore, WBMRI may be a useful component of the routine baseline assessment of TP53 mutation carriers in children and adults [4].

A new aspect in unveiling unpredicted mutp53 functions is its link with dysbiotic microbiota that is associated, for instance, with lung carcinogenesis, the number one cause of cancer deaths. Recent microbiome studies have demonstrated a contribution of bacteria to carcinogenesis in colon and lung, for instance. Starting from the hypothesis that somatic mutations together with cigarette smoke generate a chronic inflammatory microenvironment and that epidemiological evidence indicates an association between repeated antibiotic exposure and increased lung cancer risk, it has been shown that mutations in TP53 are associated with the enrichment of a microbial consortia that are highly represented in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) tumors, providing novel biomarkers for early detection [5]. The tumor-host interaction is therefore an important link in the progression of cancer and even in therapeutic failure. Intriguingly, it has been reported in colon cancer patients that mutp53 triggers reprogramming of macrophages by non-cell-autonomous mechanism toward M2 immunosuppressive phenotype, through miR-1246-enriched exosomes. Uptake of these exosomes by neighboring macrophages triggers their miR-1246-dependent reprogramming into a cancer-promoting state. These findings, associated with poor survival patients, strongly support a microenvironmental GOF role for mutp53 to promote cancer progression and metastasis [6]. The tumor microenvironment offers favourable conditions for tumor progression, and activated fibroblasts, known as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), play a pivotal role. Recently, a specific signature of microRNA (miRNAs) (miR-126, miR-141 and miR-21), which are called metastamir, was found upregulated in the serum with a significant correlation with the presence of early stage colorectal liver metastasis [7]. In light of the positive correlation between mutant p53 and miR-21 expression existing in different metastasizing tumors, is to be supposed that these findings might unveil additional microenvironmental GOF mechanisms for mutp53, although how mutp53 is involved in the exosome machinery needs further studies.

Genetic reconstitution of the function of p53 leads to the suppression of established tumours as shown in mouse models [8]. This strongly supports the notion that p53 reactivation by small molecules could provide an efficient strategy to rescue p53 mutants and reactivate their anti-tumor capacity through a variety of mechanisms [9]. Stabilization of mutp53 folding by Apr-246, which is currently being tested in a Phase II clinical trial, appears so far to be the most promising approach, when combined with various kinase inhibitors or inhibitors of PARP enzymatic activity. In the 8th p53 Mutant Workshop several classes of compounds that could reactivate wild-type p53 activities have been discussed, such as Mdm4 inhibitors, which are currently undergoing clinical testing, MdmX inhibitors and molecules targeting factors upstream of Mdm4/X [10]. Several new molecules and peptides, found through multiple approaches, have been proposed in the last years to restore a wild type conformation of mutp53, resuming previous studies indicating that ablation of the metallothioneins, which are zinc-storing proteins, leads to the unfolding of wtp53 and thus inhibits its transcriptional activity.

Conclusion

At the end of the Workshop more questions than answers were raised, and it was clear that the successful implementation of p53-based therapies into clinical practice requires a thorough understanding of the mechanisms underlying the p53 response in both cancer cells and normal tissue (Fig. 1). Several important issues should be addressed in the future including the identification of biomarkers of resistance to p53-based therapies and possible side effects. The combinations of drugs that can act synergistically when combined with p53 reactivators seem a very promising approach.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people in the lab for critical discussion.

Abbreviations

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- GOF

Gain-of-function

- LFS

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- miRNA

microRNA

- mutp53

mutant p53

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- WBMRI

Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging

- wtp53

Wild-type p53

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in conceptualization, writing and revising of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research in G.D. lab within the realm of this manuscript is funded by AIRC and by Fondi Ateneo. The research leading to these results has received funding from AIRC under IG 2018 - ID. 21434 project – P.I. Fontemaggi Giulia; IG 2018 - ID. 20613 project – P.I. Giovanni Blandino.

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed in this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Silvia Di Agostino, Email: silvia.diagostino@ifo.gov.it.

Giulia Fontemaggi, Email: giulia.fontemaggi@ifo.gov.it.

Sabrina Strano, Email: sabrina.strano@ifo.gov.it.

Giovanni Blandino, Email: giovanni.blandino@ifo.gov.it.

Gabriella D’Orazi, Email: gdorazi@unich.it.

References

- 1.Mantovani F, Collavin LDS. G: mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:199–212. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Orazi G, Cirone M. Mutant p53 and cellular stress pathways: a criminal alliance that promotes cancer progression. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:E614. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guha T, Malkin D. Inherited TP53 mutations and the li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;3:7. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballinger ML, Best A, Mail PL, Khincha PP, Loud JT, Peters JA, et al. Baseline surveillance in li-Fraumeni syndrome using whole-body magnetic resonance imaging: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1634–1639. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greathouse KL, White JR, Vargas AJ, Bliskovsky VV, Beck JA, von Muhlinen N, et al. Interaction between the microbiome and TP53 in human lung cancer. Genome Biol. 2018;19:123. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1501-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooks T, Pateras IS, Jenkins LM, Patel KM, Robles AI, Morris J, et al. Mutant p53 cancers reprogram macrophages to tumor supporting macrophages via exosomal miR-1246. Nat Commun. 2018;9:771. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03224-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frixa T, Donzelli S, Blandino G. Oncogenic MicroRNAs: key players in malignant transformation. Cancers (Basel). 2015;7(4):2466–2485. doi: 10.3390/cancers7040904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozano G. The oncogenic roles of p53 mutants in mouse models. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blandino G, Di Agostino S. New therapeutic strategies to treat cancers expressing mutant p53 proteins. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:30. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0705-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda PJ, Buckley D, Raghu D, Pang JB, Takano EA, Vijayakumaran R, et al. MDM4 is a rational target for treating breast cancers with mutant p53. J Pathol. 2017;241:661–670. doi: 10.1002/path.4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed in this study are included in this published article.