Abstract

Background

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) leads to early loss of ovarian function in women aged < 40 years and is highly heterogeneous in etiology. The genetic etiology of this disorder remains unknown in most women with POI.

Methods

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was used to analyze genetic factors within a Chinese POI pedigree. Bioinformatic analysis was applied to identify the potential genetic cause, and Sanger sequencing confirmed the existence of a mutation within the pedigree. A minigene assay was performed to validate the effect of the mutation on pre-mRNA splicing.

Results

A novel heterozygous missense mutation in HFM1 (c.3470G > A) associated with POI was identified by whole-exome sequencing. This mutation was heterozygous in the affected family members and was absent in the unaffected family members. In silico analysis predicted that the mutation was potentially pathogenic. Bioinformatic splice prediction tools revealed that the mutation was very likely to have a strong impact on splice site function. Results of the minigene assay revealed that the mutation changed the mRNA splicing repertory.

Conclusions

The missense mutation of the HFM1 gene (c.3470G > A) may be a cause of POI. The mutation altered mRNA splicing in cells. This study can provide geneticists with deeper insight into the pathogenesis of POI and aid clinicians in making early diagnoses in affected women.

Keywords: Premature ovarian insufficiency, HFM1, Whole-exome sequencing, Splicing minigene

Background

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a clinical syndrome defined by loss of ovarian activity before the age of 40 and is characterized by amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea for at least 4 months and raised serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels > 25 IU/L on two occasions > 4 weeks apart [1]. POI has a great impact on women’s fertility and long-term health [2]. It affects approximately 1 in 100 women and 1 in 1000 women at the ages of 40 and 30, respectively [3]. Women with POI have menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, sleep disturbance, vaginal dryness and emotional disturbance in the short term and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis in long term [4–6].

POI is highly heterogeneous in etiology, which includes genetic, iatrogenic, autoimmune, and infectious factors [7]. Although the disorder is generally considered to have a strong genetic link, the underlying cause remains unknown in many women with POI [4]. With a decrease in running costs, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has recently been widely used in the field of research and clinical medicine and has revealed genetic causes in 20–25% of women with POI [8, 9]. Furthermore, genetic predisposition can be verified by analysis of familial aggregation of women with POI, suggesting existence of inherited genetic defects in these families [10].

In this study, we used whole-exome sequencing (WES) to evaluate the genetic cause of POI in a Chinese family with a family history of POI. A minigene splicing assay was performed to identify a novel heterozygous splice-altering mutation in the meiotic-related gene HFM1. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the mutation of the HFM1 gene (c.3470G > A) as a potential cause of POI. The contribution of the mutation to the etiology of POI was evaluated.

Methods

Study participants and their families

A Han Chinese family was recruited in Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. POI was diagnosed in accordance with previously described criteria [1], that is, a depletion or loss of normal ovarian function in women before 40 years of age with FSH > 25 IU/L on two occasions > 4 weeks apart. The proband (II-1) and her mother (I-1) were affected by POI at the ages of 31 and 30 years old, respectively. The proband’s sister(II-2)was fertile and had no difficulty conceiving. The Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital, Nanfang Medical University (NFEC-2017-197) approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DNA extraction and WES

Total genomic DNA was extracted from all participants by using a TIANamp Blood DNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples from the proband, her sister and their parents were subjected to WES using a HiSeq Xten sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). The raw sequencing data included 58,850,887,060 reads, and the average raw sequencing depth (X) was 139.32.

Mutation validation and co-segregation analysis

Sanger sequencing was performed using specific PCR primers designed with Primer Premier 5 (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/primerdesign/). The sequences of HFM1 primers used were HFM1-F: 5′-TTCATGTTGCCCACAGAGAGAA-3′ and HFM1-R: 5′-TTGTCTGAAAGGAAGGAAACTGG-3′. PCR amplification included 1 cycle at 98 °C for 30 s followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 5 s, 55 °C for 5 s, and 72 °C for 20 s per 1 kb as an extension step. A final extension step of 1 cycle at 72 °C for 60 s was also performed. The HFM1 mutation was validated as previously described, and segregation analysis was performed in the family members.

In silico prediction

The potential pathogenicity of the mutation was predicted by in silico analysis using four different tools: Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD, https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/). The potential effect on splicing was predicted with two splice-site prediction programs, i.e., Human Splicing Finder (HSF, http://www.umd.be/HSF3/HSF.shtml) and Splice Site Prediction by Network (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html).

Minigene splicing assay

Synthesis of hybrid minigenes

A minigene splicing assay was performed to verify whether the mutation affected splicing products. To test the effect of the candidate mutation c.3470 G > A in HFM1 on splicing, amplicons generated by standard overlapping PCR and digestion procedures were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 reporter vector (Life Technologies, New York, USA). PCR and Sanger sequencing were used to evaluate whether the wild-type (WT) and mutant-type (MT) expression vectors had been successfully constructed.

Characterization of HFM1 expression

WT or MT HFM1 minigenes were transiently transfected into HeLa cells and 293 T cells using Liposomal Transfection Reagent(40802ES03, YEASEN, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

All cellular RNAs were extracted using the RNAiso Plus (Code No.9109, Takara, Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Total RNA was used to produce cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Cat#RR047A, Takara, Otsu, Japan). Then, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized and amplified. The PCR products were separated and verified by electrophoresis in an agarose gel and characterized by direct Sanger sequencing.

Results

Clinical findings

The proband (II-1) and her mother (I-1) were diagnosed with POI (Fig. 1a). The proband, a 33-year-old woman, had been diagnosed at the age of 31. She experienced menarche at the age of 14 and had 28–30 day menstrual cycle but had irregular menstrual cycles after 2015. She had a termination of pregnancy with an unplanned natural pregnancy at 31 years old, then was diagnosed with POI in the same year. She had a natural pregnancy at the age of 32, but unfortunately the embryo stopped to develop at 8 weeks. Her basic hormone levels were as follows: FSH, 78 mIU/ml; luteinizing hormone(LH), 31 mIU/ml; estradiol(E2), 13 pg/ml; prolactin(PRL), 13 ng/ml; testosterone(T), 18 ng/dl; and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), 0.06 ng/ml, respectively with the examination in Nanfang Hospital, Guangzhou. Transvaginal ultrasound examination revealed a normal-sized uterus (37 × 35 × 32 mm). The endometrium was 2.5 mm in thickness. The sizes of the two ovaries were smaller than that of a normal ovary (left ovary: 11 × 8 × 10 mm; right ovary: 15 × 7 × 12 mm), and only one antral follicle was observed in the left ovary.

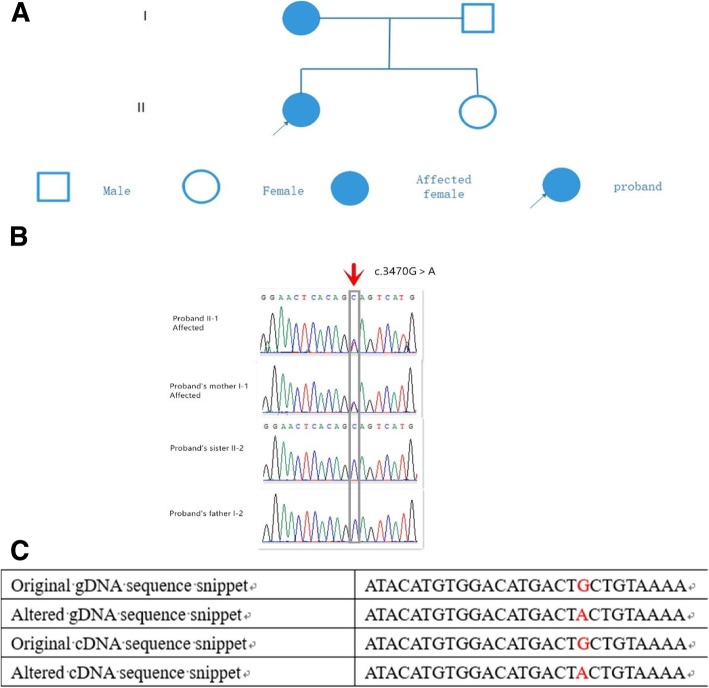

Fig. 1.

Pedigree and genetic analysis of the Chinese family. (a) Two family members in this pedigree were diagnosed with POI. The solid circle with an arrow indicates the proband. Solid circles indicate the affected family members. (b) Validation of the mutation by Sanger sequencing. The red arrow and gray frame indicate the mutation site (c.3470G > A) in I-1 and II-1 as double peaks and the lack of mutation in I-2 and II-2 as a single peak. (c) Original and altered gDNA and cDNA sequence snippets. The location of c.3470G>A is marked in red

The proband’s mother (I-1) experienced menarche at 13 years old, which was within the normal age range. She had an early marriage and suddenly underwent menopause a year after the birth of her last child and was diagnosed with POI at the age of 30. Both the proband and her mother had normal 46, XX karyotypes with normal height, weight and external genital organs. Neither woman had a history of relevant surgeries, endocrinopathies or autoimmune disorders. The fertile younger sister, aged 30 years old, had normal spontaneous pubertal development and conceived spontaneously and delivered a healthy girl.

WES analysis and HFM1 mutation co-segregation with POI in this family

WES was performed on the proband, her sister and their parents. Harmful mutations were identified by screening the mutation sites. First, mutation sites with population frequencies > 0.01 were filtered from the 1000 Genomes Project database. Next, mutation sites with frequencies > 0.01 were filtered from the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (ExAC) and the Exome Sequencing Project 6500 (ESP6500) dataset. Third, mutations in exonic regions or splicing regions were preserved. Fourth, synonymous mutations were filtered out, and nonsynonymous mutations were retained. Finally, we used four different tools to predict the potential pathogenicity of the identified mutations.

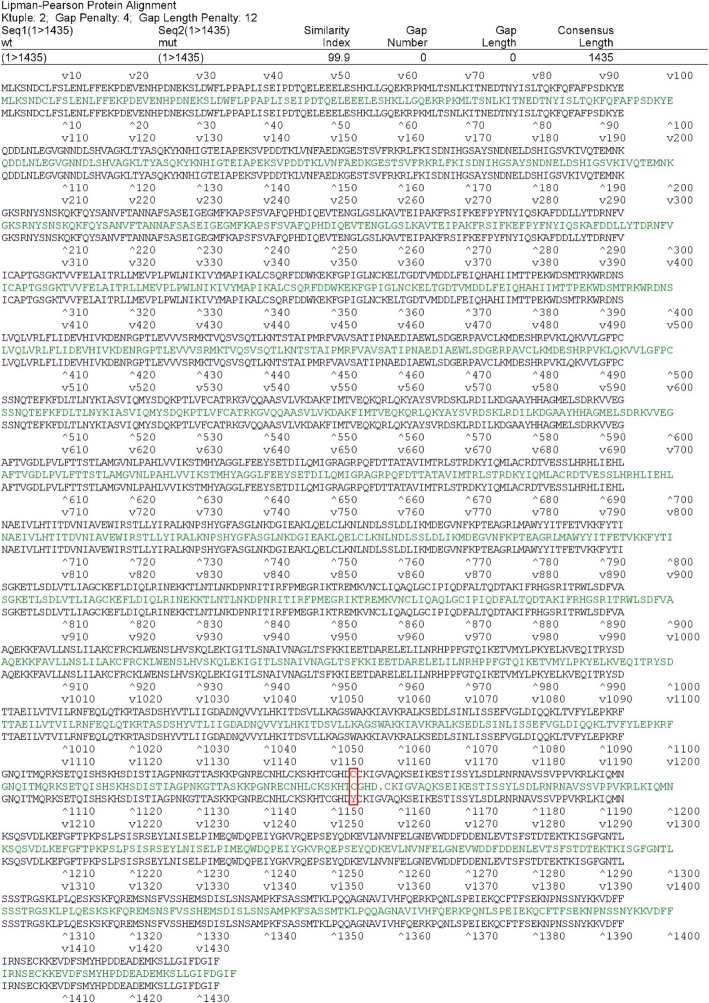

Based on the pipeline output and the several filtering steps after WES, a heterozygous missense mutation in the ATP-dependent DNA helicase homolog (HFM1), namely, NM_001017975:exon31:c.3470G > A, was identified in the proband and her mother (Table 1). The original and altered gDNA and cDNA sequence snippets are shown in Fig. 1c. Missense mutation caused changes in the amino acid sequence from the WT amino acid sequence (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

In silico analysis of the HFM1 mutation

| Gene | Mutation | Amino acid change | Zygosity | SIFT score | SIFT_pred | Polyphen2_HDIV_score | Polyphen2_HDIV_pred | Polyphen2_HVAR_score | Polyphen2_HVAR_pred | MutationTaster_score | MutationTaster_pred | CADD_phred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFM1 | c.3470G>A | G > A | Heterozygous | 0 | D | 1 | D | 0.998 | D | 1 | D | 29.7 |

“D” indicates that the mutation is damaging or deleterious. In SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/), mutations with values above 0.05 are predicted to be damaging. In Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2), higher scores predict the mutation to be more deleterious. In MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), the probability value ranges from 0 to 1, and a higher score (closer to 1) indicates a stronger prediction of disease. In Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) (http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/), the suggested threshold for harmfulness of a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is a CADD_Phred score > 15

Fig. 2.

Comparison of wild-type and mutant amino acid sequences. The red residues in the position marked with a red box are the amino acids at the HFM1 mutation site

Sanger sequencing was performed to validate the HFM1 mutation shared by the two POI patients in the family, and Mendelian segregation in the family members was tested. The proband (II-1) and her mother (I-1) had the heterozygous mutation in HFM1, whereas the father (I-2) and the unaffected sister (II-2) did not have the mutation (Fig. 1b).

Potential effects of the HFM1 mutation

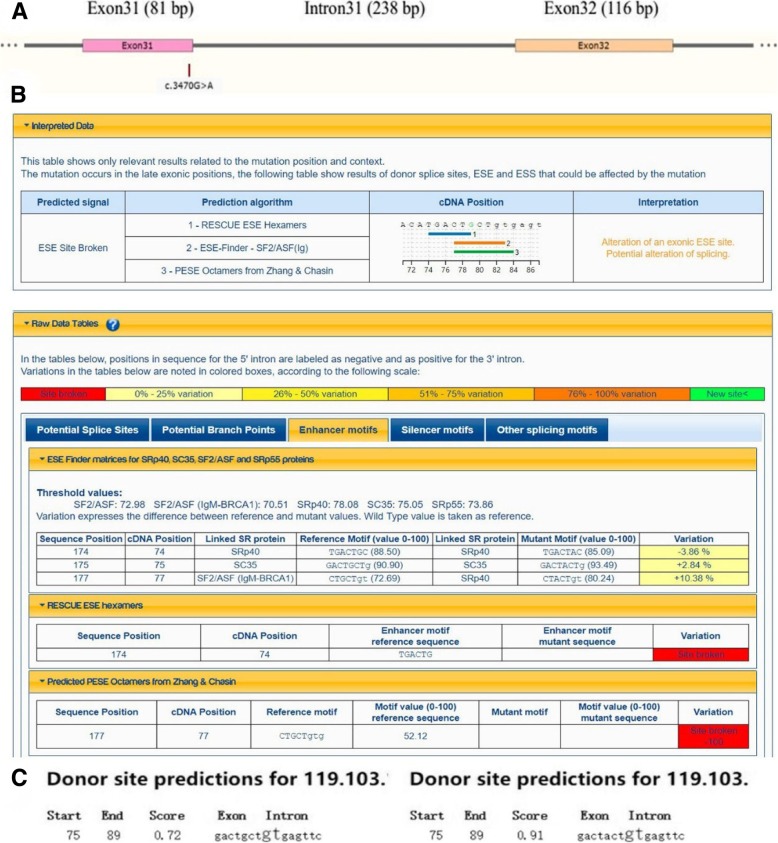

The identified missense mutation in HFM1 (c.3470G > A) was located on the third-to-last base of exon 31 (Fig. 3a). This location was very close to an intersection of splice sites and could thus affect the splice sites. Therefore, we used Human Splicing Finder (HSF) and Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network to predict changes in splice sites caused by the mutation. The first prediction tool predicted that the mutation could potentially alter splicing, possibly causing changes or destruction of splicing enhancer sites and resulting in splice site abnormalities (Fig. 3b). According to the second splice prediction tool, the confidence scores, which predict the possibility of selective splicing, were 0.72 to 0.91 before and after mutation, respectively (Fig. 3c). The increasing score indicated that it was likely to be affected splice site. In summary, both splicing prediction software programs indicated that the mutation (c.3470G > A) was likely to influence splicing products.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of potential functions of the HFM1 mutation. (a) Schematic diagram of the location of the HFM1 mutation with regard to exons and introns. The missense mutation in HFM1 (c.3470G > A) is located at the third-to-last base of exon 31. (b) The underlined sequences were analyzed, and possible changes in splice sites were predicted with HSF. (c) Differences in confidence scores before vs. after mutation as determined with Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network

Results of the Minigene assay

Colony PCR test and sequencing in recombinant vector

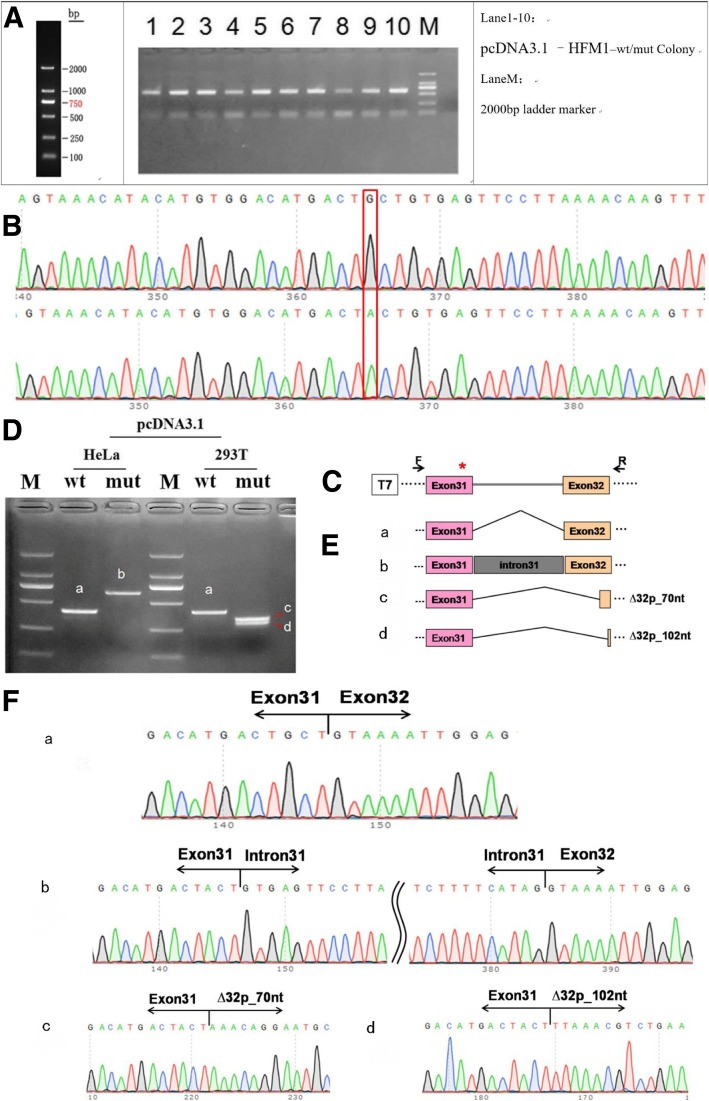

The colony PCR tests in pcDNA3.1-wt/mut were done with the following primers: pcDNA3.1-F:5′-ACTTAAGCTTATGGGAAC-3′ and pcDNA3.1-R:5′-CGGTGGATCCCTTCAGACGTTTAACTGGAGGA-3′. The amplified bands (Fig. 4a) were cloned, and the resulting clones were sequenced. The sequencing results indicated that the Wild type(WT) and Mutant type (MT) minigenes were inserted into the pcDNA3.1 vector successfully. The sequence difference between before and after the mutation is shown in Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

Splicing alteration was identified by a minigene assay. (a) Amplification bands of colony PCR tests in pcDNA3.1-wt/mut. (b) Sequencing in the recombinant vector. The top of Fig. 4b indicates the results of WT minigene sequencing, and the bottom shows the sequencing of the MT (c.3470G > A) minigene. Both of them are partial sequencing results. The red frame indicates the base changed by the mutation. (c) Schematic diagram of minigene construction. (d) Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) products were separated by electrophoresis of the pcDNA3.1 vector in HeLa and c293T cells. (e) Schematic diagram of Sanger sequencing of RT-PCR products. (f) The sequencing results for the bands

RNA extraction and cDNA for RT-PCR

RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed into cDNA after plasmid transfection of cells for 48 h. Total RNAs were qualified for each sample, with an average mass of 402 ng and integrity of 1.879.

Transfection and quantitative analysis of transcript mutation

To verify the effect of the c.3470G > A mutation in HFM1 on pre-mRNA splicing, we performed a minigene assay. In the assay, a mutant HFM1 minigene was transfected into HeLa cells and 293 T cells. A total of 4 samples were collected after 36 h of transfection. A schematic diagram of the minigene construct is shown in Fig. 4c.

The results of RT-PCR showed that there was only one WT and one MT band in HeLa cells. The WT band with the expected size was named band a, while the MT band was named band b (Fig. 4d). Sequencing showed that the WT band was cleaved normally (400 bp), i.e., the cleavage mode of the band was Exon 31 (81 bp)-Exon 32 (116 bp) (Fig. 4E-a). The MT band b (638 bp) retained all the intron 31. The cleavage mode of the band b was Exon31-intron31-Exon 32 (Fig. 4E-b). In the 293 T cells, the minigene splicing assay of the WT and MT constructs revealed one expected band produced by WT (a) and two bands of similar size in MT. The large band and the small band were named c and d respectively (Fig. 4d). Sequencing of each band showed that band a (400 bp) had normal splicing, and its cleavage mode was Exon 31 (81 bp)-Exon 32 (116 bp), as above. Band c showed a deletion of 70 bp on the left side of exon 32, i.e., the cleavage mode was Exon 31 (81 bp)-ΔExon 32 (46 bp) (Fig. 4E-c). Band d included a deletion of 102 bp on the left side of exon 32. Its cleavage mode was Exon 31 (81 bp)-∆Exon 32 (14 bp) (Fig. 4E-d). The sequencing results of the bands are shown in Fig. 4f. These results show that the HFM1 mutant minigenes produced alternative transcripts different from the WT minigene in two cell types.

Discussion

In this pedigree, we identified a novel missense mutation c.3470G > A in HFM1 associated with POI. Our study showed that the mutation altered mRNA splicing. The proband and her mother were heterozygous carriers of the mutation and exhibited the POI phenotype, whereas the sister and the father of the proband did not have the mutation.

HFM1 is a gene involved in meiosis, which is a critical process in generating haploid gametes. It is a specialized type of nuclear division [11, 12], and genes participating in meiosis are potential candidates in POI pathogenesis [13, 14]. Most mutations in genes associated with POI have deleterious impacts on the germ cell pool [15].

HFM1, comprising 39 exons mapped to human chromosome 1q22, is a meiosis-specific gene and is expressed in germline tissues [16–18]. HFM1 encodes a DNA helicase essential for meiotic homologous recombination. Its transcript is preferentially expressed in ovaries [19]. One mutation in HFM1 has been found to reduce crossover frequency and impair double-strand break repair, resulting in changes to the DNA during meiotic recombination [20]. Guiraldelli et al. reported that HFM1-deficient mice were infertile [21]. HFM1-knockout mice exhibit phenotypes resembling POI in humans. Recent evidence suggests that mutations in HFM1 could cause POI in humans, as compound heterozygous mutations in the HFM1 gene were identified in two affected POI sisters and a woman with sporadic POI [22]. In the former case, both parents were clinically normal and carried one of the mutations, whereas the two affected sisters had the same compound heterozygous mutation in HFM1. These findings demonstrate that HFM1 mutations are etiologic factors of POI at the genetic level.

It is reported that HFM1 mutation is as a cause of POI as a previous report in a Chinese pedigree. [22]. In our case, we found that the POI pedigree represents that the proband and her mother with POI had this mutation in HFM1 whereas the unaffected sister and their father did not have one. We also found that both of the POI patients had a history of birth or pregnancies before or after the diagnose of POI. The reason why the differences may be due to incomplete penetrance or the different degrees of expressivity in individuals. In our study, the novel heterozygous splice-altering mutation in HFM1(c.3470G > A) may be a cause of premature ovarian insufficiency and further exploration can be made to explain the in-depth pathogenesis.

Pathogenic mutation can influence mRNA transcription. At the level of the pre-mRNA processing, splicing defects play a majority role in human diseases. The functioning of basic and auxiliary splicing elements is necessary for proper pre-mRNA splicing [23]. To date, a series of splice-site mutations are known. In Chinese POI patients, a splicing mutation (c.1686-1G > C) in HFM1 has been reported in a previous study [22]. Moreover, Pu et al. studied 138 Chinese sporadic POI cases and identified 5 new missense mutations, but no functional studies were conducted [17]. In our study, since the missense mutation in HFM1 (c.3470G > A) was very close to an intersection of splice sites, we used bioinformatic splice prediction tools to assess the possible effect of the c.3470G > A mutation, which revealed that the mutation might have a great impact on splice site function. It is reported that a minigene experiment can produce splicing results reaching almost 100% similarity [24]; therefore our minigene splicing assay of the WT and MT constructs revealed that an alternative splicing process were produced with the c.3470G > A mutation in mRNA level. Further studies are still needed to confirm the role of the HFM1 gene mutation (c.3470G > A) in POI in protein level and potential functions in cells of involved in meiosis, which is a critical process in human fertility.

Conclusions

In summary, we identified a novel heterozygous missense mutation in the HFM1 gene (c.3470G > A) in two POI patients of a Chinese family by WES. The mutation of HFM1 gene at c.3470G > A caused a splicing defect by in vitro minigene assay. It is suggested that the splice-altering mutation in HFM1 is a likely cause of POI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Ng Ernest Hung-Ye and Professor Yeung, William Shu-Biu from the University of Hong Kong for revising our manuscript and polishing the language. We also thank Associate Professor Bei Jia from Prenatal Diagnosis and Clinical Genetics, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University for her consulting help. We are grateful to the proband and her family members for participating in this study.

Abbreviations

- AMH

Anti-Mullerian hormone

- CADD

Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion

- E2

Estradiol

- ESP6500

Exome Sequencing Project 6500

- ExAC

Exome Aggregation Consortium database

- FSH

Follicle stimulating hormone

- HSF

Human Splicing Finder

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- MT

Mutant type

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- POI

Premature ovarian insufficiency

- PRL

Prolactin

- T

Testosterone

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

- WT

Wild type

Authors’ contributions

JZ and SC contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, experiments and writing and revising of the manuscript. XC, YL, XZ, YL and JZ contributed to data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research & Developmental Program of China (2017YFC1001103) and the Clinical Research Startup Program of Southern Medical University by High-level University Construction Funding of Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (LC2016ZD010) and Clinical Research Program of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University(2018CR016).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital, Nanfang Medical University (NFEC-2017-197).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhe, Email: zxrzjj8@163.com.

Shiling Chen, Email: chensl_92@163.com.

Xin Chen, Email: zhiduoxinrun@hotmail.com.

Yudong Liu, Email: liuyd9@163.com.

Ying Li, Email: 18820791562@163.com.

Xingyu Zhou, Email: zhouxy315@163.com.

Jun Zhang, Email: 2575429499@qq.com.

References

- 1.Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, Braat D, Cartwright B, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:926–937. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiao X, Zhang H, Ke H, Zhang J, Cheng L, Liu Y, et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency: phenotypic characterization within different etiologies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:2281–2290. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panay N. Management of premenstrual syndrome. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2009;35:187–194. doi: 10.1783/147118909788708147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vos M, Devroey P, Fauser BC. Primary ovarian insufficiency. Lancet. 2010;376:911–921. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:606–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0808697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah D, Nagarajan N. Premature menopause - meeting the needs. Post Reprod Health. 2014;20:62–68. doi: 10.1177/2053369114531909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucker EJ, Grover SR, Bachelot A, Touraine P, Sinclair AH. Premature ovarian insufficiency: new perspectives on genetic cause and phenotypic Spectrum. Endocr Rev. 2016;37:609–635. doi: 10.1210/er.2016-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin Y, Jiao X, Simpson JL, Chen ZJ. Genetics of primary ovarian insufficiency: new developments and opportunities. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:787–808. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laissue P. The molecular complexity of primary ovarian insufficiency aetiology and the use of massively parallel sequencing. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;460:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelling AN. X chromosome defects and premature ovarian failure. Aust NZ J Med. 2000;30:5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2000.tb01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stack SM, Anderson LK. A model for chromosome structure during the mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. Chromosom Res. 2001;9:175–198. doi: 10.1023/A:1016690802570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page SL, Hawley RS. Chromosome choreography: the meiotic ballet. Science. 2003;301:785–789. doi: 10.1126/science.1086605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monget P, Bobe J, Gougeon A, Fabre S, Monniaux D, Dalbies-Tran R. The ovarian reserve in mammals: a functional and evolutionary perspective. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;356:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries L, Behar DM, Smirin-Yosef P, Lagovsky I, Tzur S, Basel-Vanagaite L. Exome sequencing reveals SYCE1 mutation associated with autosomal recessive primary ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E2129–E2132. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiao X, Ke H, Qin Y, Chen ZJ. Molecular genetics of premature ovarian insufficiency. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sugawara Hiroko, Iwabata Kazuki, Koshiyama Akiyo, Yanai Takuro, Daikuhara Yoko, Namekawa Satoshi H., Hamada Fumika N., Sakaguchi Kengo. Coprinus cinereus Mer3 is required for synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis. Chromosoma. 2008;118(1):127–139. doi: 10.1007/s00412-008-0185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pu D, Wang C, Cao J, Shen Y, Jiang H, Liu J, et al. Association analysis between HFM1 variation and primary ovarian insufficiency in Chinese women. Clin Genet. 2016;89:597–602. doi: 10.1111/cge.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Zhang W, Timofejeva L, Gerardin Y, Ma H. The Arabidopsis ROCK-N-ROLLERS gene encodes a homolog of the yeast ATP-dependent DNA helicase MER3 and is required for normal meiotic crossover formation. Plant J. 2005;43:321–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka Kazunori, Miyamoto Natsuki, Shouguchi-Miyata Junko, Ikeda Joh-E. HFM1, the human homologue of yeast Mer3, encodes a putative DNA helicase expressed specifically in germ-line cells. DNA Sequence. 2006;17(3):242–246. doi: 10.1080/10425170600805433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MER3 gene, encoding a novel helicase-like protein, is required for crossover control in meiosis. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18(20):5714–5723. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guiraldelli Michel F., Eyster Craig, Wilkerson Joseph L., Dresser Michael E., Pezza Roberto J. Mouse HFM1/Mer3 Is Required for Crossover Formation and Complete Synapsis of Homologous Chromosomes during Meiosis. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9(3):e1003383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Jian, Zhang Wenxiang, Jiang Hong, Wu Bai-Lin. Mutations in HFM1 in Recessive Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(10):972–974. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1310150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baralle Diana, Buratti Emanuele. RNA splicing in human disease and in the clinic. Clinical Science. 2017;131(5):355–368. doi: 10.1042/CS20160211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klift HMVD, Jansen AML, Niki VDS, Bik EC, Tops CMJ, Peter D ,et al. Splicing analysis for exonic and intronic mismatch repair gene variants associated with Lynch syndrome confirms high concordance between minigene assays and patient RNA analyses. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 2015;3:327–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.