Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide problem that crosses international boundaries and spread between continents easily. Hence, information on the existence of the causative microorganisms and their susceptibility to commonly used antibiotics are essential to enhance therapeutic outcome.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted retrospectively at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. The culture and antibiotic sensitivity data of the isolates were collected from the record books of the microbiology unit for the study period after official permission obtained from the institutional review board. The data entered and analyzed using statistical package for social science software version 20.

Result

A total of 693 bacteria were retrieved, of these 435(62.77%) were gram-negative and the rest 258(37.23%) were gram-positive. Most of the isolates were from a urine sample. Among gram positives isolates, S. aureus and from gram negatives Klebsiella spp are the most recurrent isolate. Almost a remarkable resistance was observed to most of the antibiotics mainly, penicillin G (81.8%) and cotrimoxazole (81.1%), for gram-positive bacteria. The gram-negative bacteria also show resistance to ampicillin (92.5%), tetracycline (85%) and cotrimoxazole (93.1%).

Conclusions

Nearly all isolate show substantial rates of resistance to most of the antibiotic that is frequently used in the study area. As already known we want to emphases on the importance of performing continuous monitoring of drug susceptibility to help the empirical treatment of bacterial agents to a health professional in the region. In addition, this data might help policymakers to control of antibiotics resistance.

Keywords: Antibiotics resistance, Clinical samples, Southern Ethiopia

Background

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide problem that can cross international boundaries and spread between continents with ease [1, 2]. The introduction of antibiotics in the mid-twentieth century was an important medical event in history with regard to reducing human and livestock morbidity and mortality. However, the subsequent and continuing intensive use of antibiotics since their introduction has helped to select a huge increase in the frequency of resistance among human pathogens [3]. Antibiotic resistance results in reduced efficacy of antibacterial agents make the treatment of patients difficult, costly, or even impossible. The impact on susceptible patients is most obvious, resulting in prolonged illness and even mortality. The magnitude of the problem and the impact of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) on human health including on costs for the health-care due to AMR still largely need further investigation [4].

The antibiotic resistance crisis has been attributed to the overuse and misuse of medications, as well as a lack of new drug development by the pharmaceutical industry due to reduced economic incentives and challenging regulatory requirements [5, 6]. In high-income countries, continued high rates of antibiotic use in hospitals contributed to selection pressure that has sustained resistant strains, forcing a shift to more expensive and more broad-spectrum antibiotics [6]. In low-income countries, divers antibiotic usage increases time to time due to high rates of hospitalization, and the high rate of infectious disease [6, 7].

On the other hand, the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria is a challenge for physicians to manage critical patients [8]. As already known, methicillin-resistant s. aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum ß-lactamase (ESBL) E. coli, vancomycin-resistant s. aureus and enterococcus associated morbidity and mortality are global problems [9, 10]. In regard to our setup, drug resistance to be expected as a major challenge even though there is no local report as well drug resistance monitoring system. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the burden of antibiotic resistance patterns by analyzing data collected retrospectively of a period of 3 years at the Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH) in southern Ethiopia.

Methods

This study design was an institution based cross-sectional study from November 2014–November 2017 retrospectively. The study was conducted on all clinical sample sent to the microbiology lab of HUCSH, Hawassa, Ethiopia. Hawassa is a city in Ethiopia, on the shores of Lake Hawassa in the Great Rift Valley. It is located 270 km south of Addis Ababa via Debre Zeit. The town serves as the capital of the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). It lies on the Trans-African Highway to Cairo-Cape Town, and has a latitude and longitude of 7° 3′ 35 “ N and of 38° 28’ 11” E. It has an elevation of 1708 m above sea level [11].

The HUCSH serves as a referral centre for both public and private hospitals in South Regional State also for the neighbouring region. The hospital was established in November 2005 and serves about 12 million people in the Southern Nation, Nationalities’ and peoples’ region (SNNPR) and neighbouring Oromia. Besides providing clinical services, the hospital is a teaching hospital for medical and paramedical students. It is located 273 km south of the capital city, Addis Ababa. The microbiology laboratory at HUCSH was established in 2010. It is the only laboratory in the region that participates in obtaining accreditation.

Patient data were reviewed by the principal investigators using a designed chart. Thus, all cultured sample of the patient and appropriate information were retrieved from the microbiology laboratory unit registration book. Age, sex, specimen type, bacterial isolates and antibiotic susceptibility pattern were collected using a data extraction sheet. Those with incomplete data that means a data which was not recorded for either of the isolated organism, antibiotics susceptibility, unknown sample type, sex and age were excluded. Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 20 was used for both data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the frequency of isolated bacteria.

The microbiological lab performs culture and sensitivity test from the urine, puss, blood, ear discharge, eye swab, genital swab, stool, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), sputum and nasal swab sample suspected for any bacterial infection based on the standard operating procedure (SOP). The samples were sent from different wards however the samples address was not recorded in the laboratory book. All samples were cultured on appropriate culture media i.e. manual blood culture was conducted whenever a blood-stream infection is suspected in trypticase soy broth prepared in the laboratory. If there is an indication of growth like hemolysis, gas, and turbidity the inoculum was subcultured on appropriate solid medium for further identification. Blood and MacConkey agar were used to culture non-fastidious bacteria and Chocolate agar included for fastidious bacteria and Thayer Martin agar for the genital sample was used. The single bacterial colony from culture media was taken for gram staining. Based on the gram reaction biochemical tests selected. Gram-positive bacteria are identified using catalase, coagulase, bacitracin, pyrrolidonyl arylamidase (PYRase), optochin bile solubility and Novobiocin. Gram-negative bacterial was identified based on serial biochemical reactions and fermentation of carbohydrates i.e. oxidase, catalase, triple sugar iron agar, citrate utilization test, urease, lysine iron agar, sulphur indole motility, mannitol fermentation, and indole test. Gram staining and colony characteristic were used for preliminary identification of the bacteria. Some bacterial were identified to species level by biochemical and some of them to genus level by morphological characteristics (grams stain and colony characteristics). The antibiotic sensitivity pattern was determined with the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique and interpreted based on the current clinical and laboratory standard Institute (CLSI) 2014–2017 guideline.

The susceptibility testing was conducted based on the recommendation of the CLSI. Different antibiotic discs (Abtek LTD, UK) were used: Ampicillin (AMP)(10 μg), gentamicin-Gen(10 μg), ciprofloxacin-CRP(5 μg), ceftriaxone-CRT(30 μg), ceftazidime-CAZ(30 μg), norfloxacin-NOR)(10 μg), nitrofurantoin-NIT(300 μg), augmentin-AUG(20/10 μg), cotrimoxazole-COT(1.25/23.75 μg), chloramphenicol-CAF(30 μg), meropenem-MER(10 μg), tetracycline-TAT(30 μg), penicillin G-PEN(10 IU), Clindamycin-CLD(2 μg) and erythromycin-ERY(15 μg).

Quality control

The microbiology lab performs quality control of all culture system by using E. coli (ATCC-25922), S. aureus (ATCC- 25923) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC-27853) which was ordered and supervised by the national lab of Ethiopia.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from, Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Besides official permission was obtained from the hospital administration to collect the information from the registration book. Patients’ data were anonymized and kept confidential throughout this study. All data obtained in the course of the study were reserved confidential and used only for this study.

Results

Percentage of total isolates within age and sex

A total of 693 bacteria were included for the study from different clinical specimens (blood, urine, puss, genital swab, eye swab, ear discharge, sputum, nasal swab, body fluids, CSF and stool). Of these 435(62.8%) were gram-negative bacteria (GNB) and the rest 258(37.2%) were gram-positive bacteria (GPB). Most of the isolates were detected in children less than 5 years of age (48.2%; 334/693) followed by 24–64 years of age (21.2%; 147/693); the least number of isolates were found from patients > 64 years of age. Most of the isolates were from male patients with a male to female ratio 1.13:1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of patients with bacterial isolates, HUCSH, Southern Ethiopia

| Age group in year | Sex | Total Bacteria (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male N (%) | Female N (%) | ||

| < 5 | 189(51.2) | 145(44.8) | 334(48.2) |

| 5–14 | 62(16.8) | 68(21) | 130(18.8) |

| 14–24 | 33(8.9) | 29(9) | 62(8.9) |

| 24–64 | 74(20.1) | 73(22.5) | 147(21.2) |

| > 64 | 11(3) | 9(2.8) | 20(2.9) |

| Total | 369(100) | 324(100) | 693(100) |

Sample type and bacterial isolates

Regarding sample type, most of the isolates were from urine sample 251(36.2%) followed by puss sample 190(27.4%) and blood 131(18.9%). When we observe the frequency of isolates; S. aureus was the leading 156(22.5%) and S. pneumoniae 7(1%) was the least from gram-positive bacteria. Klebsiella spp 154(22.2%) were the predominant isolates and N. gonorrhoea 3(0.4%) was the least from gram-negative bacteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of sample type and bacterial isolates from a study of the burden of antimicrobial resistance at HUCSH, southern Ethiopia

| Specimen type | Total | |||||||||||

| Isolates | Urine | Body Fluids | Stool | Ear Swab | Eye swab | CSF | Blood | Sputum | Puss | Nasal swab | Genital swab | |

| S. auraes | 22(8.8) | 6(31.6) | 0 | 5(11.9) | 6(50) | 0 | 19(14.5) | 1(5.9) | 97(51.1) | 0 | 0 | 156(22.5) |

| CoNS | 9(3.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55(42) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64(9.2) |

| Enterococcus spp | 17(6.8) | 1(5.3) | 0 | 0 | 1(8.3) | 0 | 10(7.6) | 1(5.9) | 1(0.5) | 0 | 0 | 31(4.5) |

| S. pneumonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3(7.1) | 0 | 1(14.3) | 3(2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7(1) |

| Klebsiella spp | 79(31.5) | 5 (26.3) | 0 | 9(21.4) | 2(16.7) | 0 | 26(19.8) | 8(47.1) | 25(13.2) | 0 | 0 | 154(22.2) |

| E. coli | 70(27.9) | 2(10.5) | 0 | 9(21.4) | 1(8.3) | 2(28.6) | 5(3.8) | 0 | 26(13.7) | 1 (50) | 0 | 116(16.7) |

| Pseudomonas spp | 11(4.4) | 1(5.3) | 0 | 9(21.4) | 0 | 0 | 7(5.3) | 3(17.6) | 15(7.9) | 1 (50) | 0 | 47(6.8) |

| Citrobacter spp | 16(6.4) | 3(15.8) | 0 | 2(4.8) | 1(8.3) | 0 | 1(0.8) | 2(11.8) | 7(3.7) | 0 | 0 | 32(4.6) |

| Enterobacter spp | 16(6.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(8.3) | 0 | 2(1.5) | 1(5.9) | 4(2.1) | 0 | 0 | 24(3.5) |

| Acinetobacter spp | 4(1.6) | 0 | 0 | 1(2.4) | 0 | 0 | 2(1.5) | 1(5.9) | 10(5.3) | 0 | 0 | 18(2.6) |

| Proteus Spp | 6(2.4) | 1(5.3) | 0 | 4(9.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5(2.6) | 0 | 0 | 16(2.3) |

| Shigella spp | 0 | 0 | 12(63.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12(1.7) |

| Salmonella spp | 1(0.4) | 0 | 7(36.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9(1.3) |

| N. meningitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4(57.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4(0.6) |

| N. gonorrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3(100) | 3(0.4) |

| Total | 251(36.2) | 19(2.7) | 19(2.7) | 42(6.1) | 12(1.7) | 7(1) | 131(18.9) | 17(2.5) | 190(27.4) | 2(0.3) | 3(0.4) | 693(100) |

Antibiotics resistance patterns of GPB

Concerning antibiotics resistance, we can say that extraordinarily resistant were recorded for cotrimoxazole, penicillin G, norfloxacin and ceftazidime by most of the gram-positive bacteria. In the other hand least resistance was recorded for nitrofurantoin (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antibiotics resistance patterns of GPB, HUCSH, and Southern Ethiopia

| Antibiotics | S. aureus (156) | CoNS (64) | Enterococcus spp(31) | S. pneumoniae (7) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | |

| AMP | NR | NR | 20(74.1) | NR | 20(74.1) |

| GEN | 42(31.8) | 32(55.2) | NR | NR | 74(38.9) |

| COT | 61(73.5) | 49(90.7) | NR | 4(66.7) | 116(81.1) |

| PEN | 41(80.4) | 24(92.3) | 6(75) | 1(33.3) | 72(81.8) |

| CAF | 22(19.5) | 22(40.7) | 8(34.8) | 3(60) | 55(28.2) |

| CLD | 2(5.3) | ND | NR | NR | 2(5.3) |

| NOR | 15(65.2) | 3(33.3) | 10(83.3) | NR | 28(63.6) |

| NIT | 1(14.3) | ND | 1(12.5) | NR | 2(13.3) |

| ERY | 20(31.7) | 9(50) | 11(73.3) | 0(0) | 40(40.4) |

| TAT | 11(61.1) | ND | 3(100) | 0(0) | 14(63.6) |

| CIP | 42(31.8) | 27(46.6) | 19(76) | NR | 88(40.9) |

| AUG | 51(52) | 24(39.3) | NR | NR | 75(47.2) |

| CTR | 39(45.3) | 22(41.5) | NR | NR | 61(43.9) |

| CAZ | 27(58.7) | 31(79.5) | NR | ND | 58(68.2) |

NR- Not recommended, ND-not done, R-Resistance, T- total tested, CoNS- coagulase-negative staphylococcus, ampicillin (AMP)(10 μg), gentamicin-Gen(10 μg), ciprofloxacin-CRP(5 μg), ceftriaxone-CRT(30 μg), ceftazidime-CAZ(30 μg), norfloxacin-NOR)(10 μg), nitrofurantoin-NIT(300 μg), augmentin-AUG(20/10 μg), cotrimoxazole-COT(1.25/23.75 μg), chloramphenicol-CAF(30 μg), meropenem-MER(10 μg), tetracycline-TAT(30 μg), penicillin G-PEN(10 IU), Clindamycin-CLD(2 μg) and erythromycin-ERY(15 μg).

Antibiotics resistance patterns of Enterobacteriaceae

Again higher resistance was reported from Enterobacteriaceae. As shown in Table 4 ampicillin (92.5%), cotrimoxazole (85%) and tetracycline (85%) was substantially resisted antibiotics.

Table 4.

Antibiotics resistance patterns of Enterobacteriaceae, HUCSH Southern Ethiopia

| Antibiotics | E. coli (116) | Klebsiella spp (154) | Enterobacter spp (24) | Citrobacter spp (32) | Proteus spp (16) | Shigella spp (12) | Salmonella spp (9) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | |

| AMP | 84(92.3) | 106(93.8) | 17(94.4) | 21(91.3) | 8(88.9) | 6(75) | 5(100) | 247(92.5) |

| GEN | 55(55.6) | 107(79.3) | 15(78.9) | 16(61.5) | 7(50) | 4(40) | 3(50) | 207(67) |

| CRP | 51(48.1) | 57(41.3) | 8(38.1) | 6(22.2) | 5(55.6) | 2(25) | 3(33.3) | 132(41.5) |

| CTR | 50(66.7) | 97(86.6) | 10(83.3) | 14(63.6) | 8(61.5) | 5(50) | 4(50) | 188(74.6) |

| CAZ | 28(56) | 46(78) | 4(66.7) | 3(37.5) | 2(40) | 2(100) | 1(100) | 86(65.6) |

| NOR | 46(61.3) | 35(43.8) | 8(47.1) | 6(31.6) | 4(66.7) | ND | – | 100(50.8) |

| NIT | 1(3.8) | 1(7.1) | 1(11.1) | 1(16.7) | 1(100) | ND | 0(0) | 5(8.7) |

| AUG | 65(65.7) | 93(74.4) | 14(82.4) | 15(60) | 5(38.5) | 4(50) | 4(57.1) | 200(68) |

| COT | 51(81) | 86(91.5) | 14(82.4) | 6(54.5) | 5(83.3) | 4(80) | 4(100) | 170(85) |

| CAF | 26(36.6) | 51(51) | 5(50) | 8(42.1) | 4(50) | 3(42.9) | 3(42.9) | 100(45.1) |

| MER | 0(0) | 3(13.6) | 5(62.5) | 2(42.9) | 0(0) | ND | 0(0) | 11(22.9) |

| TAT | 6(100) | 4(100) | 3(60) | 4(100) | 0(0) | ND | ND | 17(85) |

ND-Not done, R-Resistance, ampicillin (AMP)(10 μg), gentamicin-Gen(10 μg), ciprofloxacin-CRP(5 μg), ceftriaxone-CRT(30 μg), ceftazidime-CAZ(30 μg), norfloxacin-NOR)(10 μg), nitrofurantoin-NIT(300 μg), augmentin-AUG(20/10 μg), cotrimoxazole-COT(1.25/23.75 μg), chloramphenicol-CAF(30 μg), meropenem-MER(10 μg), tetracycline-TAT(30 μg)

Antibiotics resistance patterns of gram negatives non-Enterobacteriaceae

Likewise, a remarkable resistance for tested antibiotics was recorded by most non- Enterobacteriaceae isolates. As shown in Table 5 tetracycline (100%), cotrimoxazole (93.1%) and ampicillin (92.9%), was mainly resisted antibiotics.

Table 5.

Antibiotics resistance patterns of non- Enterobacteriaceae group at HUCSH, Southern Ethiopia

| Antibiotics | Pseudomonas spp (47) | Acinetobacter spp (18) | N. gonorrhoea (3) | N. meningitis (4) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | R (%) | |

| Amp | 23(92) | 15(88.2) | NR | ND | 39(92.9) |

| Gen | 22(55.2) | 11(84.6) | NR | ND | 33(62.2) |

| CRP | 14(32.6) | 9(56.2) | 2(100) | 2(50) | 27(41.5) |

| CTR | 23(67.6) | 10(76.9) | 2(66.7) | 1(100) | 38(71.7) |

| CAZ | 10(47.6) | 3(75) | 1(100) | 1(100) | 15(55.6) |

| NOR | 3(25) | 3(60) | NR | ND | 7(41.2) |

| AUG | 24(85.7) | 11(78.6) | NR | 1(100) | 36(83.7) |

| COT | 15(88.2) | 10(100) | NR | 1(50) | 27(93.1) |

| CAF | 14(70) | 10(83.3) | NR | 2(100) | 26(76.5) |

| MER | 2(50) | 2(50) | NR | ND | 4(50) |

| TAT | 3(100) | 2(100) | ND | NR | 5(100) |

ND-not done, NR-not recommended, ampicillin (AMP)(10 μg), gentamicin-Gen(10 μg), ciprofloxacin-CRP(5 μg), ceftriaxone-CRT(30 μg), ceftazidime-CAZ(30 μg), norfloxacin-NOR)(10 μg), nitrofurantoin-NIT(300 μg), augmentin-AUG(20/10 μg), cotrimoxazole-COT(1.25/23.75 μg), chloramphenicol-CAF(30 μg), meropenem-MER(10 μg), tetracycline-TAT(30 μg).

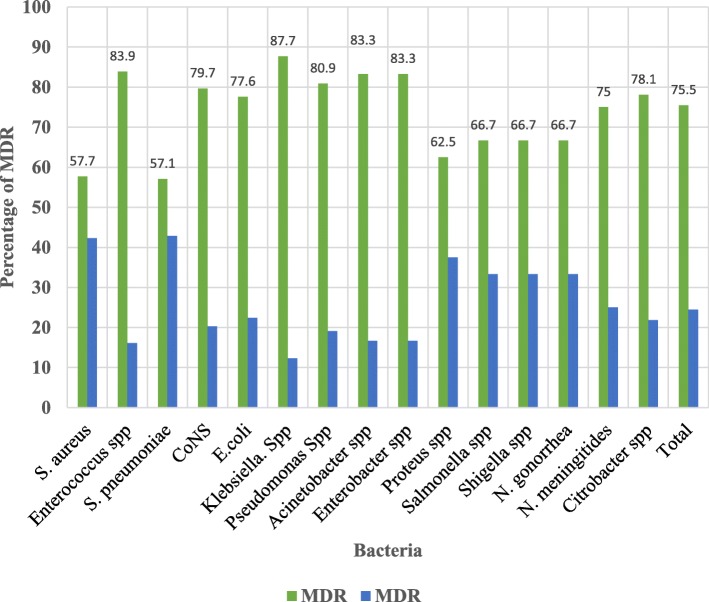

Multi-drug resistance pattern

Multi-drug resistance (MDR) is defined as resistance to at least one or more agents in three or more antibiotics categories [12]. Overall MDR to all isolates were (75.5%). Of this Klebsiella spp had been with highest MDR which was (87.7%) followed by Enterococcus spp (83.9%), Acinetobacter spp (83.3%), Enterobacter spp (83.3%) and Pseudomonas spp (80.9%). Least MDR was identified from S. aureus (57.7%) followed by S. pneumoniae (57.1%), Proteus spp (62.5%) and (66.7%) for each of these isolates (Salmonella spp, Shigella spp and N. gonorrhoea) (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Multi-drug resistance in a study of the burden of antimicrobial resistance at HUCSH

Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the most serious problems faced the world nowadays. The lack of effective antibiotics will challenge healthcare workers to combat infectious diseases including their potential to manage complications, especially among immunocompromised clients. In this study, gram-negative bacteria were predominantly isolated from most specimens. The finding is similar to the studies reported from Southwest and Debre Markos. Ethiopia reported regardless of specimen type difference [13, 14]. The most frequently isolated gram-positive bacterium was S. aureus and the lest frequently isolated bacterium was S. pneumoniae which is in-line with a study conducted in Debre Markos on the clinical specimen and Bahir Dar from nosocomial infected patients in Ethiopia [14, 15] and in India from clinical specimen [16]. In the other hand Klebsiella, spp were the predominant gram-negative bacteria in our study, in-line with our finding studies from India reported the same [17]. In contrast to our study, E. coli were reported as dominant bacteria from India from clinical specimen conducted retrospectively [16] which can be explained by study area, period and individual difference.

Our finding indicated that extraordinary rates of resistance for most antibiotics. Specifically, gram-positive bacteria were resistant to ampicillin, cotrimoxazole and penicillin G which is in agreement with reports from Debre Markos [14] and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [18], Ardabil, Iran [19], Gabon, Central Africa [10] and South East Nigeria [20]. Even though there is a difference in the study area and period, the amount of sample analyzed and a number of bacterial isolates captured.

Gram-negative bacteria had a remarkable rate of resistance to most antibiotics other studies from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [21], Saudi Arabia [22], and Libya [23] agreed with our study as gram-negative bacteria (GNB) are more resisted as compared to GPB. On the other hand, low rates of resistance for all Enterobacteriaceae was observed to nitrofurantoin and meropenem in-line with studies from Bahir Dar, Ethiopia [24], Benin Nigeria [25].

Concerning non- Enterobacteriaceae, a high rate of resistance were observed to tetracycline, cotrimoxazole, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, chloramphenicol and gentamicin. This resistance may be due to Pseudomonas spp and Acinetobacter spp which are the most common known resistant because of their nature of resistance for different chemical agents. Other studies supported this finding as high resistance Pseudomonas Spp from Iran [26], Dhaka [27], Nigeria [28], and Taiwan [29].

In our study we identified (57.1–87.3%) MDR, this showed that there are a few options to treat patients in the study area. Which was almost similar to others finding like, Studies reported from Mexico [30], Ethiopia [31], Hungary [32]. In general, we can say that antibiotics resistance will be a great challenge in the study area if there is no appropriate solution set on time.

Limitation of the study

✓ This study is a retrospective study so could not explain the current antimicrobial patterns in the study area.

✓ The study did not determine the resistance detected was due to hospital-acquired or community acquired infection.

✓ The study did not show the trends of antibiotics resistance from year to year.

Conclusions

This retrospective study identified revealed that nearly all the isolated bacteria developed substantial rates of resistance to most of the antibiotics that are frequently used in the study area. To some extent, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, nitrofurantoin and chloramphenicol were effective to treat GPB, whereas penicillin G, cotrimoxazole, augmentin, ampicillin, norfloxacin, ceftazidime and tetracycline were the least effective antibiotics. Therefore, in general, the antibiotic-resistant rate is high in the specified study area, the physician should prescribe antibiotics based on drug susceptibility report. In case of the empirical treatment is mandatory prescribing antibiotics with less resistance may be helpful to manage bacterial infections. We hope also that these studies finding will help policymakers nationally as the best data for developing intervention measures and to exclude most resistant drugs from the market.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital for official permission of this study and microbiology staffs for helping during data collection.

Ethics approval and consent to participation

The research was ethically approved by IRB of Hawassa University College of Medicine and health sciences. Permission for data collection was obtained from the hospital laboratory manager. Patients’ data were anonymized and kept confidential throughout this study. All data obtained in the course of the study were reserved confidential and used only for this study.

Competing of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial Resistance

- ATCC

American type culture collection

- CLSI

Clinical and laboratory standard Institute

- CoNS

Coagulase-negative staphylococcus

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum ß-lactamase

- GNB

Gram-negative bacteria

- GPB

Gram-positive bacteria

- HUCSH

Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MDR

Multi-drug resistance

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant S. auraes

- PYRase

Pyrrolidonyl arylamidase

- SNNPR

Southern Nation Nationalities’ and peoples’ region

- SOP

Standard operating procedure

- SPSS

Statistical package for social sciences

Authors’ contributions

TA, MA, EM and MH conceived the idea, develop the proposal, collected the data, perform the analysis and prepared the manuscript, MH has made final edition of the document. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to perform this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tsegaye Alemayehu, Phone: (+2519)-13-87-24-12), Email: alemayehutsegaye@ymail.com.

Mulubrahan Ali, Email: yeabderese@gmail.com.

Enkosilassie Mitiku, Email: enkosilassiem@gmail.com.

Mengistu Hailemariam, Email: mengemariamzenebe@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO global strategy for containment of antimicrobial resistance. No WHO/CDS/CSR/DRS/2001.2. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2001.

- 2.Choffnes ER, Relman DA, Mack A. Antibiotic resistance: implications for global health and novel intervention strategies Workshop summary: 2010: National Academies Press. 2010. Antibiotic resistance: implications for global health and novel intervention strategies. Workshop summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson DI, Hughes D. Persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(5):901–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankar PR, Balasubramanium R. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. Australasian Medical Journal (Online) 2014;7(5):237. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 2: management strategies and new agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;40(5):344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AK, Wertheim HF, Sumpradit N, Vlieghe E, Hara GL, Gould IM, Goossens H. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laxminarayan R, Heymann DL. Challenges of drug resistance in the developing world. BMJ. 2012;344:e1567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayinalem GA, Gelaw BK, Belay AZ, Linjesa JL. Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone in the medical ward of Dessie referral hospital, north East Ethiopia. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2017;2(6):711–717. doi: 10.5455/2319-2003.ijbcp20131208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amato-Gauci A. Annual epidemiological report on communicable diseases in Europe: report on the status of communicable diseases in the EU and EEA/EFTA countries: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2007.

- 10.Alabi AS, Frielinghaus L, Kaba H, Kösters K, Huson MA, Kahl BC, Peters G, Grobusch MP, Issifou S, Kremsner PG. Retrospective analysis of antimicrobial resistance and bacterial spectrum of infection in Gabon, Central Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):455. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bureau SNaNaPRSCaT: The General Background of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Regional State. 2019, http://www.southtourism.gov.et/?q=background.

- 12.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey R, Carmeli Y, Falagas M, Giske C, Harbarth S, Hindler J, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan-drug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mama M, Abdissa A, Sewunet T. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from wound infection and their sensitivity to alternative topical agents at Jimma University specialized hospital, south-West Ethiopia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulu W, Abera B, Yimer M, Hailu T, Ayele H, Abate D. Bacterial agents and antibiotic resistance profiles of infections from different sites that occurred among patients at Debre Markos referral hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2584-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulu W, Kibru G, Beyene G, Damtie M. Postoperative nosocomial infections and antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacteria isolates among patients admitted at Felege Hiwot referral hospital, Bahirdar, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(1):7–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Divyashanthi C, Adithiyakumar S, Bharathi N. Study of prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(1):185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul R, Ray J, Sinha S, Mondal J. Antibiotic resistance pattern of bacteria isolated from various clinical specimens: an eastern Indian study. 2017. 2017;4(4):5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilnessa T, Bitew A. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples at Yekatit 12 hospital medical college, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:398. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1742-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dibah S, Arzanlou M, Jannati E, Shapouri R. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain isolated from clinical specimens in Ardabil Iran. Iranian Journal of Microbiology. 2014;6(3):163–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nsofor C, Nwokenkwo V, Ohale C. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from various clinical specimens in south-East Nigeria. MOJ Cell Sci Rep. 2016;3(2):60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabew G, Abebe T, Miheret A. A retrospective study on prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacterial isolates from urinary tract infections in Tikur Anbessa specialized teaching hospital Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2013;27(2):111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haseeb A, Faidah HS, Bakhsh AR, Al Malki WH, Elrggal ME, Saleem F, ur Rahman S, Khan TM, Hassali MA. Antimicrobial resistance among pilgrims: a retrospective study from two hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:92–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed MA, Alnour TM, Shakurfo OM, Aburass MM. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacterial strains isolated from patients with urinary tract infection in Messalata central hospital. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine Libya. 2016;9(8):771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alabi AS, Frielinghaus L, Kaba H, Kosters K, Huson MA, Kahl BC, Peters G, Grobusch MP, Issifou S, Kremsner PG, et al. Retrospective analysis of antimicrobial resistance and bacterial spectrum of infection in Gabon, Central Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:455. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahoyo TA, Bankole HS, Adeoti FM, Gbohoun AA, Assavedo S, Amoussou-Guenou M, Kinde-Gazard DA, Pittet D. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and anti-infective therapy in Benin: results of the first nationwide survey in 2012. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:17. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babakhani S, shokri Derikvand S, Nazer MR, Kazemi MJ. Comparison frequency and determination antibiotic resistance pattern of Klebsiella SPP. isolated from nosocomial infection in Khorramabad Shohadaye Ashayer hospital. Bull Env Pharmacol Life Sci. 2014;3:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoque MM, Ahmad M, Khisa S, Uddin MN, Jesmine R. Antibiotic resistance pattern in pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from different clinical specimens. Journal of Armed Forces Medical College, Bangladesh. 2016;11(1):45–49. doi: 10.3329/jafmc.v11i1.30669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igbalajobi O, Oluyege A, Oladeji A, Babalola J. Antibiotic Resistance Pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Clinical Samples in Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State of Nigeria. British Microbiology Research Journal. 2016;12(4):1–6. doi: 10.9734/BMRJ/2016/22515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsueh PR, Tseng SP, Teng LJ, Ho SW. Pan-drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing nosocomial infection at a university hospital in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(8):670–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornejo-Juarez P, Vilar-Compte D, Perez-Jimenez C, Namendys-Silva SA, Sandoval-Hernandez S, Volkow-Fernandez P. The impact of hospital-acquired infections with multidrug-resistant bacteria in an oncology intensive care unit. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;31:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mengesha RE, Kasa BG-S, Saravanan M, Berhe DF, Wasihun AG. Aerobic bacteria in post-surgical wound infections and pattern of their antimicrobial susceptibility in Ayder teaching and referral hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7:575. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caini S, Hajdu A, Kurcz A, Borocz K. Hospital-acquired infections due to multidrug-resistant organisms in Hungary, 2005–2010. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(2). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.