Abstract

Background:

Some HIV prevention research participants may hold a “preventive misconception” (PM), an overestimate of the probability or level of personal protection afforded by trial participation. However, these reports typically rely upon small, retrospective qualitative assessments at single sites.

Methods:

We administered a measure of PM called PREMIS, during Microbicide Trials Network 020--A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use: a large multicenter, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring among women at risk for HIV infection in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The maximum follow-up period was 2.6 years.

Results:

1261 respondents completed PREMIS at M3; 2085 at M12; and 1010 at both visits. Most participants expressed high expectations of personal benefit (EPB) and that at least one of the rings used in the trial would reduce the risk of getting HIV (Expectation of Maximum Aggregate Benefit or EMAB). There was a moderate positive correlation between EPB and EMAB at M3 (r = .43, 95% C.I.: .37, .47) and M12 (r = .44, 95% C.I.: .40, .48). However, there was variability among sites in the strength of the relationship. There was no relationship between either expectation variables and condom use, adherence, or HIV infection.

Conclusions:

A majority of trial participants expressed some belief that their risk of HIV infection would be reduced by using a vaginal ring, which may signal PM. However, such beliefs were not associated with adherence, condom use, or subsequent HIV infection; and there was variability across sites. Further work is needed to understand these findings.

Keywords: preventive misconception, ethics, informed consent, HIV prevention research, attitudes

INTRODUCTION

A “preventive misconception” (PM) is an overestimate of the probability or level of personal protection afforded by participation in a clinical trial of an unproven intervention (Simon et al. 2007). A PM can be ethically problematic for prevention research in general and for HIV prevention research in particular. First, if participants harbor a PM they may alter their risk behaviors, increasing the likelihood of becoming infected with HIV (particularly if an intervention under investigation is unproven or being tested against a placebo), raising concerns about participants’ welfare and a false sense of protection or security being offered by the intervention. Second, a PM may suggest problems with comprehension of informed consent, introducing concerns about participants’ rights. Emerging data suggest that participants in some HIV prevention research hold a PM (Woodsong et al. 2012; Corneli et al 2015) and this has been associated with reports of increased rates of behaviors that elevate risk of HIV (Dellar et al. 2014). However, these reports generally rely upon small-scale, retrospective qualitative assessments that have not employed a standardized approach to assessing a PM.

In this study, we fielded a new, short quantitative measure of PM called “PREMIS” (PREventive MISconception in Microbicide Trials Network 020--A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use (MTN-020/ASPIRE) [ NCT01617096], a multicenter, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of a dapivirine vaginal ring among women at risk for HIV infection in Malawi, Uganda, South Africa, and Zimbabwe (Baeten et al. 2016). As such, the study aimed not only to measure PM in ASPIRE study participants and to assess its relationship to risk behaviors and acquiring HIV, but also to advance understanding of PM itself.

METHODS

Data for this study were collected as part of MTN-020/ASPIRE. Detailed methods and trial outcomes have been reported previously (Baeten et al. 2016). Here we describe methods specific to the PM-related objectives.

Sample and Procedures

From August 2012 to June 2014, MTN-020/ASPIRE enrolled women between the ages of 18 and 45 years who were healthy, sexually active, non-pregnant, and HIV-seronegative. Women were enrolled from 15 sites in the host countries and were randomly assigned to receive either a vaginal ring containing 25 mg of dapivirine or a placebo vaginal ring that were intended to be replaced each month. The dapivirine ring is designed to be worn continuously and women were counseled to wear the ring at all times. However, the ring is able to be removed and reinserted.

Women gave written informed consent for participation in MTN-020/ASPIRE. The consent process was supported with educational materials, such as a pictorial informed consent booklet, table top flipchart (pictorial with abbreviated language), and fact sheets specific to the study product, condoms, and other study related topics (see: https://mtnstopshiv.org/research/studies/mtn-020/mtn-020-study-implementation-materials). Visual materials were used to aid in participants’ understanding of study procedures, such as study product/packaging, randomization, and a pelvic model to demonstrate product placement. Participants could take the informed consent booklet and fact sheets home with them for reference and review between the screening and enrollment visits. Illiterate participants had a witness present during the consent process and all procedures were carried out in the language of the participant’s choice. Each site had a site-specific process for verifying literacy in native languages. At the enrollment visit, informed consent comprehension was assessed using a standardized (across sites) informed consent comprehension checklist that was IRB approved. Eight open-ended questions were asked of the participant, and required points of comprehension were evaluated. These points were reviewed with the participant as needed during the assessment. Results from the informed consent comprehension assessment were documented in each participant’s file. In addition to the screening and enrollment informed consent processes, consent comprehension assessment continued throughout the duration of the trial, either by reviewing it in a group setting or during one on one counseling during the study follow up visits.

Women returned for regular study visits and all were followed for a minimum of 12 months and a maximum of 33 months. The PREMIS items were administered orally by trained study staff members at the 3-month (M3) and 12-month (M12) visits to a subset of all participants enrolled after July 2013 because the instrument was implemented after the trial had started.

Measures

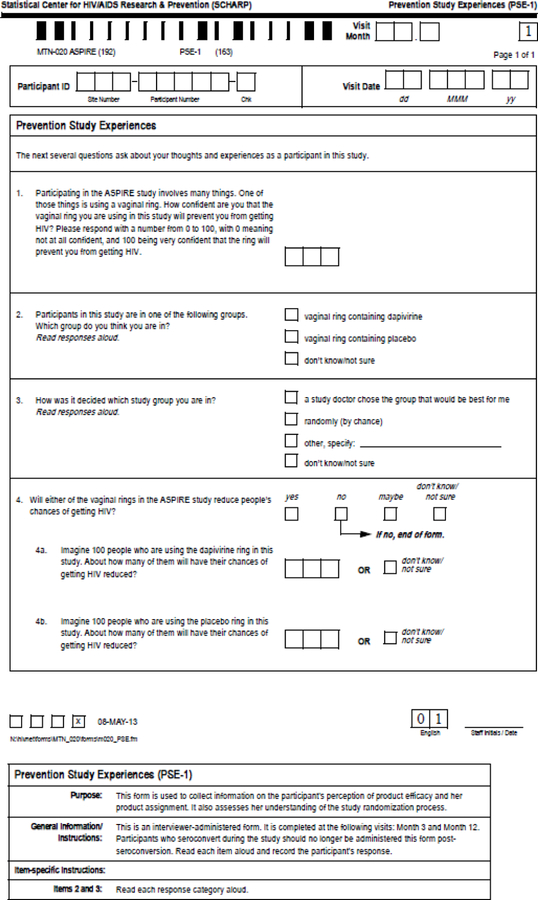

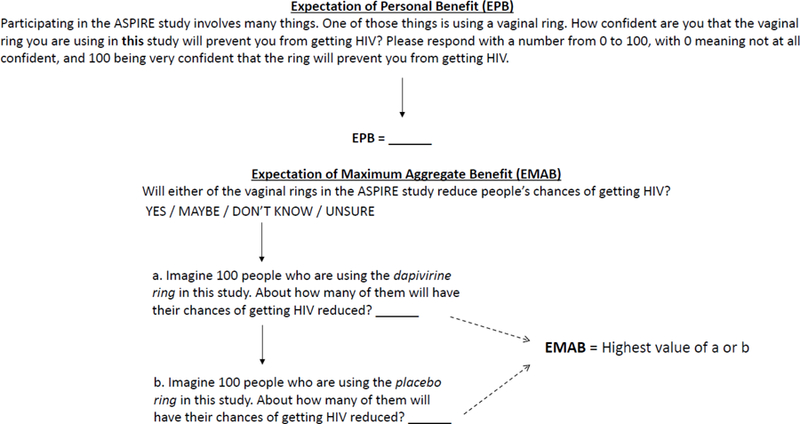

PREMIS is designed to assess trial participants’ beliefs about the risk reduction that might occur as a result of using experimental interventions. Because expectations about the future can be complex, PREMIS uses multiple ways of querying participants about their beliefs. Development of the PREMIS items is described elsewhere, and included the use of a multi-stakeholder advisory panel to guide the conceptual model and extensive, one-on-one cognitive interviews to ensure that items were understood and appropriate for participants in HIV prevention trials in the United States (Sugarman et al. 2016). The response options for some items are intended to be adapted for the particular prevention trial in which they are administered. Appendix A includes the items used in ASPIRE. PREMIS items are analyzed individually, but two responses in particular are central to the measure (See Figure 1). The first is the Expectation of Personal Benefit (EPB) assessed via item 1, which asks how confident the participant feels that the vaginal ring she is using in the study will prevent her from getting HIV. The second is the Expectation of Maximum Aggregate Benefit (EMAB), which is the higher of the participant’s responses to items, which ask, for each experimental group, how many people out of 100 will have their chances of getting HIV reduced. In other words, EMAB is the participant’s estimate of the percentage of people who will benefit in the most efficacious study arm. For this study, PREMIS items were forward/back translated to ensure fidelity of each item as originally composed in English using the same process that was employed for all survey items utilized in MTN-020/ASPIRE.

Appendix.

Figure 1.

Expectations of Benefits

As an approximate measure of preventive behaviors in this study population, we employed self-reported condom use that was being assessed in MTN-020/ASPIRE. Similarly, an objective assessment of adherence to the ring in the trial was measured by the amount of residual dapivirine in used rings. The less residual dapivirine, the more adherent was the woman, with <23.5 mg considered as demonstrating at least some adherence to the vaginal ring over the course of the prior month for purposes of the main trial analysis. HIV seroconversion was assessed via a standard algorithm (Baeten et al. 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for participant demographic variables at the baseline visit and for PREMIS item responses at M3 and M12. PREMIS responses were compared between M3 and M12 using McNemar’s (for 2 × 2) and Bowker’s (for k x k) tests of symmetry for nominal categorical responses and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for ordinal categorical responses. We examined the correspondence between EPB and EMAB responses at both M3 and M12 using Spearman’s r with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. We also explored whether the relationship between these two senses of benefit varied by study site, which likely reflects geographic, cultural, personnel, and linguistic differences. Similarly, we examined whether EPB and EMAB varied by participants’ educational level by using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Finally, we used Pearson’s χ2 and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to examine the association between EPB and EMAB on the one hand, and condom use in the past seven days and adherence to the ring on the other. The relationship between EPB and EMAB and time to HIV seroconversion was assessed in separate proportional hazards models that included treatment group and time-dependent repeated measurements of the PREMIS variable of interest (EPB or EMAB). The data analysis was generated using SAS software, Version 9 for Linux, Copyright © 2002–2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Ethics Approvals.

The ASPIRE study, including the PREMIS questionnaire, was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating sites and was overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Analyses related to the PREMIS items were deemed not to be human subjects research by the Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB and the Duke University Health System IRB.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Among the 2,629 women enrolled and followed in ASPIRE, PREMIS was completed by 2336 respondents, with 1261 at M3 and 2085 at M12; 1010 completed PREMIS at both visits. Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample at baseline (N = 2336)

| Demographic Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 26 |

| 25th, 75th percentile | 22, 31 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.3 (6.2) |

| Currently married, n (%) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) |

| Yes | 1012 (43.4) |

| No | 1322 (56.6) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |

| No schooling | 22 (0.9) |

| Primary school not complete | 233 (10.0) |

| Primary school complete | 131 (5.6) |

| Secondary school not complete | 891 (38.1) |

| Secondary school complete | 915 (39.2) |

| Attended college or university | 144 (6.2) |

| Earns income outside of home, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1060 (45.4) |

| No | 1276 (54.6) |

| Case report form language, n (%) | |

| English | 525 (22.5) |

| Shona | 635 (27.2) |

| Luganda | 236 (10.1) |

| Chichewa | 265 (11.3) |

| Zulu | 675 (28.9) |

Distribution of PREMIS Items

Distributions of responses to the PREMIS items are displayed in Table 2 by M3 and M12 study visit. Overall, most participants expressed high expectations of personal benefit (EPB; item 1) and expectations of maximal aggregate benefit (EMAB), which constitutes a belief that at least one of the rings offered in the trial would reduce the risk of getting HIV (item 4). Most were unsure which group they were in (item 2), and the majority of those who believed they knew their group assignment believed they were in the dapivirine ring arm. About 80% of participants correctly indicated that their group assignment was determined at random (item 3), with most of the remaining participants stating that they did not know or were unsure. While responses to some of the items did differ at a statistically significant (p<.05) level at the two visits, the magnitude of the differences was relatively modest, with the largest difference seen for the EMAB (medians = 70 at M3 and 80 at M12).

Table 2.

Distribution of PREMIS Item Responses, Condom Use, and Ring Adherence by Study Visit

| PREMIS Items | 3-Months Visit | 12-Months Visit | 3-Months Visit | 12-Months Visit | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (see Appendix A) | (n=1261) | (n=2085) | (Participants who completed PREMIS at both visits, n=1010) | ||

| 1. Expectation of personal benefit | 0.1294 | ||||

| Median | 70 | 75 | 70 | 80 | |

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | |

| Min, Max | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | |

| 2. Which group are you in, n (%)b | 0.1577 | ||||

| Missing | 6 (0.5) | 9 (0.4) | 2 (0.2%) | 7 (0.7%) | |

| Vaginal ring containing dapivirine | 301 (24.0) | 596 (28.7) | 245 (24.3%) | 245 (24.5%) | |

| Vaginal ring containing placebo | 97 (7.7) | 146 (7.0) | 76 (7.5%) | 53 (5.3%) | |

| Do not know/not sure | 857 (68.3) | 1334 (64.3) | 687 (68.2%) | 705 (70.3%) | |

| 3. Study group decision, n (%)b | 0.6099 | ||||

| Missing | 5 (0.4) | 9 (0.4) | 1 (0.1%) | 7 (0.7%) | |

| A study doctor chose the group | 27 (2.1) | 84 (4.0) | 24 (2.4%) | 13 (1.3%) | |

| Randomly (by chance) | 1016 (80.9) | 1613 (77.7) | 825 (81.8%) | 834 (83.2%) | |

| Other, specify | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.1%) | ||

| Do not know/not sure | 212 (16.9) | 376 (18.1) | 160 (15.9%) | 155 (15.5%) | |

| 4. Rings reduce HIV risk, n (%)b | 0.0017 | ||||

| Missing | 6 (0.5) | 12 (0.6) | 1 (0.1%) | 8 (0.8%) | |

| Yes | 842 (67.1) | 1423 (68.6) | 685 (67.9%) | 717 (71.6%) | |

| No | 64 (5.1) | 84 (4.1) | 56 (5.6%) | 28 (2.8%) | |

| Maybe | 231 (18.4) | 382 (18.4) | 179 (17.7%) | 168 (16.8%) | |

| Do not know/not sure | 118 (9.4) | 184 (8.9) | 89 (8.8%) | 89 (8.9%) | |

| 4a. Aggregate benefit for dapivirine ring | |||||

| Median | 70 | 70 | 70 | 79 | 0.1885 |

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | |

| Min, Max | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | |

| 4b. Aggregate benefit for placebo | 0.0589 | ||||

| Median | 20 | 25 | 15 | 20 | |

| 25th, 75th percentiles | 0.0, 50.0 | 0.0, 50.0 | 0.0, 50.0 | 0.0, 50.0 | |

| Min, Max | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | |

| Expectation of maximum aggregate benefitc | <.0001 | ||||

| Median | 70 | 70 | 70 | 80 | |

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 98.0 | |

| Min, Max | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | 0.0, 100.0 | |

| Condom use, n (%)b | --- | ||||

| Not asked or missing | 266 (21.1) | 536 (25.7) | 205 (20.3%) | 235 (23.3%) | |

| Neither | 499 (50.2) | 772 (49.8) | 413 (51.3%) | 420 (54.3%) | |

| Male or female condom or both | 496 (49.8) | 777 (50.2) | 392 (48.7%) | 354 (45.7%) | |

| Drug concentration - residual dapivirine level | --- | ||||

| Median | 21.3 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 21.3 | |

| 25th, 75th | 20.5, 22.5 | 20.4, 22.5 | 20.4, 22.6 | 20.3, 22.3 | |

| Min, Max | 0.0, 26.6 | 0.0, 26.6 | 0.0, 26.3 | 17.6, 26.1 | |

| Adherence to Ring d, n (%) | --- | ||||

| Missing | 56 (8.9) | 50 (4.8) | 46 (9.0) | 14 (2.7) | |

| No | 76 (12.0) | 138 (13.1) | 61 (11.9) | 56 (10.9) | |

| Yes | 500 (79.1) | 864 (82.1) | 406 (79.1) | 443 (86.4) | |

| Treatment arm, n (%) | --- | ||||

| Dapivirine | 632 (50.2) | 974 (50.7) | 497 (49.2%) | 497 (49.2%) | |

| Placebo | 628 (49.8) | 948 (49.3) | 513 (50.8%) | 513 (50.8%) | |

P-values from tests of agreement: Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous and ordinal categorical variables, and McNemar’s test for 2×2 tables or Bowker’s test of symmetry for square tables larger than 2×2;

Percent for “Not asked or missing” is based the total sample since women who did not report sexual activity over the past week were not asked about condom use; percent for other response options is calculated based on the non-missing data.

The higher of the participant’s responses to items 4a and 4b.

Adherence was defined as “Yes” = residual dapivirine of <23.5 mg and “No” = residual of ≥23.5;

Relationship between EPB and EMAB

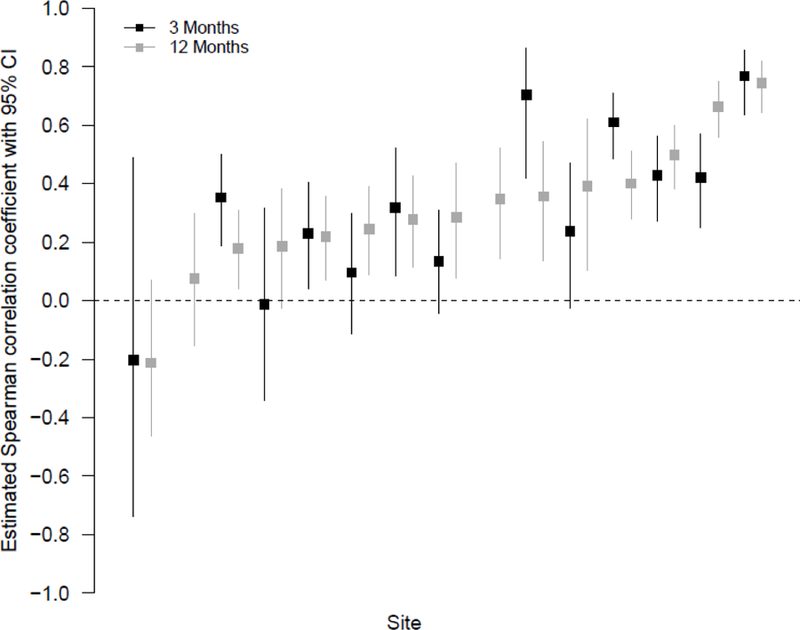

Overall, there was a moderate positive correlation between EPB and EMAB at both M3 (r = 0.43, 95% C.I.: 0.37, 0.47) and M12 (r = 0.44, 95% C.I.: 0.40, 0.48). However, there was variability among sites in the strength of the relationship (Figure 2). This variability did not appear to be related to country or language.

Figure 2.

Relationship Between EPB and EMAB

Relationship between Expectations of Benefit and Condom Use, Adherence, Education or Seroconversion

Condom use, adherence to the ring by PREMIS item responses are shown in Table 3. There was no relationship between either of the PREMIS expectation variables and condom use, or adherence. There were no statistically significant differences among education level groups and expectations of benefit.

Table 3.

Relationship between PREMIS Expectation Variables, Condom Use, and Ring Adherence by Study Visit

| PREMIS Expectation Variable | Condom Use | Adherence to Ringa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Pb | No | Yes | Pb | |

| Expectation of Personal Benefit | ||||||

| 3-month visit | 0.3188 | 0.8476 | ||||

| N | 499 | 496 | 75 | 543 | ||

| Median | 70.0 | 80.0 | 74.0 | 70.0 | ||

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | ||

| 12-month visit | 0.3302 | 0.2049 | ||||

| N | 772 | 777 | 138 | 962 | ||

| Median | 75.0 | 80.0 | 70.0 | 75.0 | ||

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 100.0 | ||

| Expectation of Maximum Aggregate Benefitc | ||||||

| 3-month visit | 0.2609 | 0.9062 | ||||

| N | 418 | 408 | 63 | 439 | ||

| Median | 70.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | ||

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 100.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 99.0 | ||

| 12-month visit | 0.3464 | 0.4730 | ||||

| N | 669 | 677 | 120 | 832 | ||

| Median | 75.0 | 75.0 | 60.0 | 70.0 | ||

| 25th, 75th percentile | 50.0, 99.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 95.0 | 50.0, 95.0 |

Adherence was defined as “Yes” = residual dapivirine of <23.5 mg and “No” = residual of ≥23.5;

P-value from Wilcoxon rank sum test;

The higher of the participant’s responses to items 4a and 4b.

PREMIS items were not administered to participants after their HIV seroconversion in the trial. However, we examined how expectations of benefits were associated with time-to HIV seroconversion, using reports from prior to HIV acquisition. There was no association between PREMIS measures and HIV acquisition, with a hazard ratio of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.04; p=0.44) for 10 units increasing in EPB and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.08; p=0.95) for 10 units increasing in EMAB.

DISCUSSION

In this first large scale test of a PM measure in a clinical trial, the majority of trial participants expressed a belief that their own risk of HIV infection would be reduced, a finding that may signal PM. Holding such beliefs was not associated with risk behaviors as assessed by condom use, adherence, or becoming infected with HIV over the course of the trial. Therefore, at least for this trial, a potential PM did not pose a risk to the welfare of research participants.

The relatively high expectations about the potential benefit of the vaginal ring may raise concerns about the rights of patients in regard to understanding the nature of trial participation despite an informed consent process that aimed to communicate the nature of a placebo controlled trial alongside other information. These concerns are tempered by several considerations. First, the measurement of PM occurred at three and 12 months following enrollment, when it would be arguably unrealistic for participants to recall complete details conveyed during the consent process at the time of enrollment. That said, information about the study was reviewed at study visits and participants received copies of the consent documents. Second, it remains unclear whether these high expectations indicate incomplete understanding or a desire to express a positive attitude, as has been found among some participants in early phase oncology trials (Sulmasy et al. 2016; Weinfurt et al. 2008; Weinfurt et al. 2012).Third, in the case of expectations expressed in terms of EMAB, participants may be reflecting potential prevention benefits of study participation other than the vaginal ring (e.g., counseling, free condoms, sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment), which could explain the median 20% expected aggregate benefit for the placebo group.

It is noteworthy that the majority of participants seemed to understand the nature of the trial in regard to randomization and reported that they did not know whether they had been assigned to receive rings containing dapivirine or placebo. Of the minority who thought they knew the ring to which they had been assigned, most thought it was the dapivirine ring. This is consistent with the report of participants in an HIV prevention trial evaluating acyclovir and may reflect a desire to be receiving the experimental intervention (Jacob et al. 2011).

This study provided an opportunity to explore different ways of expressing expectations about the future—namely, a person’s confidence that her risk of getting HIV would be reduced (EPB) and a person’s expectation about the protective effect for an aggregate of people (EMAB). The data suggest that both types of expectations reflect higher perceptions of benefit and that neither are related to risk behaviors or negative health outcomes observed in this trial. Additionally, the data suggest that while the two types of expectations have an overall moderate correlation for the total sample, there was marked variability across sites in the strength of this relationship (Figure 2). The underlying reasons for such variability are unclear. It is possible that they reflect differences among local beliefs concerning the meaning of EPB and EMAB. Such beliefs could be due to how the study was explained to participants or other more complex reasons. Thus, future qualitative work should be directed at ascertaining participants’ interpretations and construal of their situations at different sites and the interpretations of site staff as well.

The finding of site variability may have implications for advancing the conceptual understanding of PM. To date, PM has generally been considered to be operating at the level of the individual (Woodsong et al. 2012; Dellar et al. 2014; Lally et al. 2014; Ott et al. 2013) and couples (Woodsong et al. 2012) with some recognition of the need to consider community factors (Chakrapani et al. 2012). However, our data suggest that a PM may at least in part be a function of sites or communities. While qualitative data from the perspectives of participants will be essential to further elucidating these issues, it is also conceivable that site staff play an important part in shaping expectations of preventive efficacy in a variety of ways. These may occur during recruitment and consent, but also over the course of the trial when substantial attention is focused on counseling on HIV prevention and assessing and encouraging adherence.

Despite the importance of these findings, they should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. First, even though the PREMIS measure was developed using rigorous methods, this is the first time it has been fielded in a multinational trial and may be imperfect when tested at scale. For example, despite our efforts to have participants disaggregate the preventive efficacy of the vaginal ring from the preventive benefit of trial participation that included counseling, it is conceivable that this important nuance may have been missed in the field. Consequently, it needs to be assessed in other settings to better understand how it performs. Similarly, PREMIS was developed in English and therefore may perform variably in other languages. Future qualitative work with the translated PREMIS measure may help to alleviate such concerns. In addition, the PREMIS items were administered by study staff, which may have been associated with social desirability or other bias based on how the questions were actually asked. In the future, consideration should be given to administering the items in a computer assisted fashion to overcome this potential limitation. Finally, the nature of this particular trial may have influenced the findings regarding PM. Consequently, assessing its performance in other trials would be worthwhile. Nonetheless, PREMIS overcame several limitations of previous studies of PM that included being qualitative, retrospective, and not using a uniform approach.

In conclusion, in fielding a short validated quantitative measure for the first time in a multinational trial, we found that many participants had an inflated sense of preventive efficacy of a vaginal ring, but there was marked site related variations of these beliefs. While having such beliefs can be ethically problematic from the perspective of participants’ rights, they were not associated with an increase in risk behaviors or HIV seroconversions. While understanding the implications of these findings will necessitate future qualitative work at the site level, it will be important to replicate these findings in other clinical trials to assess not only how the instrument performs, but also whether safety is ever jeopardized in the presence of PM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Daniel Szydlo facilitated access to trial data. The vaginal rings used in this study were developed and supplied by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM).

Study Team Leadership: Jared Baeten, University of Washington (Protocol Chair); Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Protocol Co-chair); Elizabeth Brown, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Protocol Statistician); Lydia Soto-Torres, US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Medical Officer); Katie Schwartz, FHI 360 (Clinical Research Manager).

Study sites and site Investigators of Record: Malawi, Blantyre site (Johns Hopkins University, Queen Elizabeth Hospital): Bonus Makanani; Malawi, Lilongwe site (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill): Francis Martinson, South Africa, Cape Town site (University of Cape Town): Linda-Gail Bekker; South Africa, Durban – Botha’s Hill, Chatsworth, Isipingo, Tongaat, Umkomaas, Verulam sites (South African Medical Research Council): Vaneshree Govender, Samantha Siva, Zakir Gaffoor, Logashvari Naidoo, Arendevi Pather, and Nitesha Jeenarain; South Africa, Durban, eThekwini site (Center for the AIDS Programme for Research in South Africa): Gonasagrie Nair, South Africa, Johannesburg site (Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, University of the Witwatersrand ): Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Uganda, Kampala site (John Hopkins University, Makerere University): Flavia Matovu Kiweewa, Zimbabwe, Chitungwiza, Seke South and Zengeza sites (University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre): Nyaradzo Mgodi, Zimbabwe, Harare, Spilhaus site (University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre): Felix Mhlanga, Data management was provided by The Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research & Prevention (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) and site laboratory oversight was provided by the Microbicide Trials Network Laboratory Center (Pittsburgh, PA).

FUNDING: This work was supported in part by grant R21MH092253 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The ASPIRE clinical study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through individual grants (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615 and UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). The work presented here was funded by NIH grants UM1AI068633. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Jeremy Sugarman serves on the Merck KgaA Bioethics Advisory Panel and Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee; and he serves on the IQVIA (formerly Quintiles) Ethics Advisory Panel. Kevin Weinfurt serves as a consultant to Regeneron. Jared Baeten serves on advisory boards for Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals; has received donated medication for studies from Gilead Sciences and IPM; and has received research grants from NIH, CDC, USAID, and BMGF. Kevin Weinfurt has worked as a consultant for Regeneron. None of the other authors reported disclosures.

ETHICAL APPROVAL: The ASPIRE study, including the PREMIS questionnaire, was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating sites and was overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. Participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Analyses related to the PREMIS items were deemed not to be human subjects research by the Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB and the Duke University Health System IRB.

Contributor Information

Jeremy Sugarman, Berman Institute of Bioethics and Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland USA.

Li Lin, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Jared M. Baeten, Global Health, Epidemiology, and Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Thesla Palanee-Phillips, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Elizabeth R. Brown, Vaccine and Infectious Disease and Public Health Sciences Divisions, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Flavia Matovu Kiweewa, MUJHU Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Nyaradzo M. Mgodi, University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences Clinical Trials Research Centre, Harare, Zimbabwe

Gonasagrie Nair, Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Samantha Siva, HIV Prevention Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Durban, South Africa.

Damon M. Seils, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina USA

Kevin P. Weinfurt, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. 2016. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med 375(22):2121–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Singhal N, Jerajani J, Shunmugam M 2012. Willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials among men who have sex with men in Chennai and Mumbai, India: a social ecological approach. PLOS One 7(12):e51080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corneli A, Perry B, Agot K, Ahmed K, Malamatsho F, Van Damme L Facilitators of adherence to the study pill in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. 2015. PLoS One Apr 13;10(4):e0125458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellar RC, Abdool Karim Q, Mansoor LE, Grobler A, Humphries H, Werner L, et al. 2014. The preventive misconception: experiences from CAPRISA 004. AIDS Behav 8(9):1746–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0771-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacob ST, Baeten JM, Hughes JP, Peinado J, Wang J, Sanchez J, et al. 2011. A post-trial assessment of factors influencing study drug adherence in a randomized biomedical HIV-1 prevention trial. AIDS Behav 15(5):897–904. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9853-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lally M, Goldsworthy R, Sarr M, Kahn J, Brown L, Peralta L, et al. 2014. Evaluation of an intervention among adolescents to reduce preventive misconception in HIV vaccine clinical trials. J Adolesc Health 55(2):254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott MA, Alexander AB, Lally M, Steever JB, Zimet GD 2013. Preventive misconception and adolescents’ knowledge about HIV vaccine trials. J Med Eth 39(12):765–71. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon AE, Wu AW, Lavori PW, Sugarman J 2007. Preventive misconception: its nature, presence, and ethical implications for research. Am J Prevent Med 32(5):370–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugarman J, Seils DM, Watson-Ormond JK, Weinfurt KP 2016. Using cognitive interviews to enhance measurement in empirical bioethics: developing a measure of preventive misconception in biomedical HIV prevention trials. AJOB Empirical Bioethics 7(1):17–23. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2015.1037967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulmasy DP, Astrow AB, He MK, Seils DM, Meropol NJ, Micco E, et al. 2010. The culture of faith and hope: patients’ justifications for their high estimations of expected therapeutic benefit when enrolling in early phase oncology trials. Cancer 116(15):3702–3711. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinfurt KP, Seils DM, Tzeng JP, Compton KL, Sulmasy DP, Astrow AB, et al. 2008. Expectations of benefit in early-phase clinical trials: implications for assessing the adequacy of informed consent. Med Decis Making 28(4):575–81. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08315242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinfurt KP, Seils DM, Lin L, Sulmasy DP, Astrow AB, Hurwitz HI, et al. 2012. Research participants’ high expectations of benefit in early-phase oncology trials: are we asking the right question? J Clin Oncol 30(35):4396–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodsong C, Alleman P, Musara P, Chandipwisa A, Chirenje M, Martinson F, et al. 2012. Preventive misconception as a motivation for participation and adherence in microbicide trials: evidence from female participants and male partners in Malawi and Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav 16(3):785–90. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0027-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]