Abstract

Leukocyte telomere length (LTL), MUC5B rs35705950, and TOLLIP rs5743890 have been associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). In this observational cohort study, we assessed the associations between these genomic markers and outcomes of survival and rate of disease progression in patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF, n=250) and connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD, n=248). IPF (n=499) was used as a comparator.

LTL of IPAF and CTD-ILD patients (mean age-adjusted log-transformed T/S of −0.05, [SD 0.29] and −0.04 [0.25], respectively) are longer than IPF (−0.17 [0.32]). For IPAF, LTL <10th percentile is associated with faster lung function decline compared to LTL ≥10th percentile (−6.43%/year versus −0.86%/year, p<0.0001) and worse transplant-free survival (HR 2.97 [95% CI 1.70–5.20], p=0.00014). The MUC5B rs35705950 minor allele frequency is greater for IPAF (23.2 [95% CI 18.8–28.2], p<0.0001) than controls and is associated with worse transplant-free IPAF survival (HR 1.92, [95% CI 1.18–3.13], p=0.0091). Rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD (RA-ILD) has shorter LTL than non-RA CTD-ILD (−0.14 [SD 0.27] versus −0.01 [0.23], p=0.00055) and higher MUC5B minor allele frequency (34.6 [95% CI 24.4–46.3] versus 14.1 [9.8–20.0], p=0.00025). Neither LTL nor MUC5B are associated with transplant-free CTD-ILD survival.

LTL and MUC5B minor allele frequency have different associations with lung function progression and survival for IPAF and CTD-ILD.

Keywords: Telomere, MUC5B, TOLLIP, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features, Connective Tissue Disease Interstitial Lung Disease

Introduction

The interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by fibrosis of the lung. Determining the discrete ILD diagnosis for each patient based on clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic features is critically important for informing prognosis. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the prototypical fibrosing lung disease that has a progressive and lethal course with median survival of approximately 3 years (1), as opposed to connective tissue disease (CTD) associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) which has a much more favorable prognosis. Specific ILD diagnoses also inform treatment decisions; exposure to immunosuppressive medications is associated with worse outcomes in IPF (2) but may be beneficial for CTD-ILD (3–5). Some patients exhibit clinical features that overlap those of IPF and CTD-ILD. Recently, a joint European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society task force proposed criteria to facilitate recognition and study of this ILD subtype, termed “interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features” (IPAF). The criteria outline clinical, serologic, and morphologic features suggestive of an underlying autoimmune disease in the absence of extra-pulmonary manifestations of a well-defined CTD (6). While studies have described the clinical features and survival characteristics of patients with IPAF (7), little is known about the genetic determinants of clinical outcomes in this population.

Genetic and genomic factors are associated with risk of developing ILD and influence clinical outcomes. Common variants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the MUC5B and TOLLIP genes are more common in IPF patients compared to controls (8–10). These SNPs can inform mortality risk and rate of disease progression (10–12). Pathogenic rare variants in telomere-maintenance genes have been linked to pulmonary fibrosis and shortened telomeres, the protective ends of chromosomes. Patients with telomere-related rare variants in TERT, TERC, PARN or RTEL1 can manifest many forms of pulmonary fibrosis including IPF, IPAF, and CTD-ILD, but uniformly exhibit relentless disease progression and poor survival (13). Shortened age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (LTL) has also been associated with worse survival in patients with IPF (14–16) and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (CHP) (17).

The objective of this study was to determine if specific genetic and genomic markers associated with survival in IPF are also associated with survival and rate of disease progression in patients with IPAF and CTD-ILD. Genotypes of the MUC5B rs35705950 and TOLLIP rs5743890 SNPs as well as peripheral blood leukocyte telomere lengths (LTL) were measured across independent cohorts of patients. IPF patients were included as a comparator group.

Methods

Study design and populations

This retrospective cohort study included all patients with a diagnosis of IPAF, CTD-ILD, or IPF who were enrolled in longitudinal registries at three academic medical centers. Patients were enrolled at UT Southwestern (UTSW, Dallas, TX—June 17, 2003-July 1, 2017), University of California San Francisco (UCSF, San Francisco, CA—November 14, 1998-September 25, 2017), and University of Chicago (Chicago, IL—January 24, 2006-September 1, 2017). Each participant provided written informed consent and a peripheral blood sample at enrollment into the respective registries. Multidisciplinary discussion informed diagnosis at each site independently. IPF was diagnosed according to consensus guidelines (1), and the CTD-ILD diagnoses included rheumatologic evaluation. Each site retrospectively identified patients who met classification criteria for IPAF. The IPAF classification required at least one criterion from two or more domains (clinical, serologic, or morphologic) (6). In order to maintain consistency of the IPAF diagnosis across sites, unexplained intrinsic airway disease was not considered a component of the morphologic criteria for current or prior smokers. In addition, pulmonary vasculopathy required pulmonary artery mean pressure > 25 mm Hg and wedge pressure < 15 mmHg on right heart catheterization, or estimated right ventricular systolic pressure > 40 mm Hg by echocardiography, or presence of vasculopathy on histopathologic specimen. Thoracic radiologist and thoracic pathologist at each site reviewed high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans of the chest and available pathologic specimens to confirm presence of IPAF features. Clinical information including demographics, symptoms, signs, laboratory results, and longitudinal pulmonary function tests were abstracted from medical records. Ethnicity was self-reported. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW cohort), the University of California San Francisco (UCSF cohort), and the University of Chicago (Chicago cohort). The majority of IPF patients (UTSW N=149, UCSF N=54, Chicago N=139) (14), and IPAF patients from Chicago (n=112) were included in separate previous studies (7).

Genotyping and Telomere Length Measurements

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using an Autopure LS instrument (UTSW), a Gentra Puregene Blood kit (UCSF) or a Flexigene DNA kit (Chicago) (all from Qiagen, Valencia, CA). LTL was measured at UTSW using a quantitative polymerase chain assay (14, 18, 19); LTL were measured for the UCSF and Chicago cohorts using an identical protocol except that each sample was diluted to 20 ng/μl instead of 50 ng/μl before its addition to PCR reaction. Age-adjusted LTL was calculated using normal controls and presented as observed minus expected values. The intraclass correlation for the LTL measurement was 0.987 (95% CI 0.983–0.991), 0.989 (0.982–0.994), and 0.940 (0.924–0.953) for the UTSW, UCSF, and Chicago cohorts, respectively.

SNP genotyping was performed at UTSW for rs35705950 (MUC5B) and rs5743890 (TOLLIP) using Taqman SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The SNP genotype minor allele frequency (MAF) was calculated along with binomial 95% confidence intervals and reported for non-Hispanic white ILD patients and compared to controls from the European population of the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3, project 1 (20).

Statistics

Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and were compared across groups using the chi-squared test when the expected count for each cell is ≥5 otherwise the Fisher’s exact test was used. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations and were compared using the two-tailed Student’s t test (for two group comparisons) or one-way ANOVA (for more than two group comparisons). For comparisons across more than two groups, post-hoc analysis was performed using pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment.

The primary outcome of this study was transplant-free survival for patients with IPAF and CTD-ILD, defined as time from enrollment to death or transplant. Overall survival, with censoring at the time of transplant, was evaluated as the secondary endpoint in sensitivity analysis. The association between genomic predictors and primary and secondary endpoints was tested using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models stratified by cohort. The genomic predictors for the primary and secondary analyses included the MUC5B rs35705950 and TOLLIP rs5743890 genotype (homozygous wild-type vs heterozygous and homozygous minor allele) and age-adjusted LTL < or ≥ 10th percentile, as previous studies have shown this to be an informative cutoff point (14, 17–19). To account for baseline differences and known confounders, the association between transplant-free survival and each genomic predictor was adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, baseline forced vital capacity (FVC) percent predicted, and diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) percent predicted without imputation for missing data. An additional model was evaluated that included the pattern of ILD (UIP—yes/no) along with age, gender, ethnicity, and baseline FVC and DLCO % predicted to determine if the pattern of ILD influenced the genomic marker associations with transplant-free survival. Both LTL and MUC5B rs35705950 were included as variables in a multivariable model to assess their independent associations with transplant-free survival. A Bonferroni adjusted alpha of 0.017 (0.05/3) was used as the significance threshold to account for multiple testing with three genomic predictors (LTL, MUC5B, TOLLIP) per diagnosis for the transplant-free and overall survival analyses. There was no evidence of non-proportional hazards noted by plotting scaled Schoenfeld residuals against time for each covariate included in the Cox models.

To quantify the rate of disease progression, we assessed the change in FVC % predicted per year using linear mixed-effects models including patients with ≥ 3 available measurements that spanned ≥ 90 days. Age, gender, ethnicity, and smoking status were included as fixed effects in the model to account for baseline differences. The changes in FVC % predicted per year were reported for each genomic categorical predictor. The parameters were estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood procedure. The need for random effects was assessed using likelihood ratio tests, and random slopes and intercepts were included in the model. A Bonferroni adjusted alpha of 0.017 (0.05/3) was used as the significance threshold to account for multiple testing similar to the survival analysis. All p-values <0.05 were considered significant unless otherwise stated. All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.2 statistical analysis software (www.R-project.org).

Results

Characteristics of Disease Groups

This study included 250 patients with IPAF (UTSW=73, UCSF=63, Chicago=114), 248 patients with CTD-ILD (UTSW=102, Chicago=146), and 499 patients with IPF (UTSW=303, UCSF= 54 Chicago=142) (Table 1). Differences among the cohorts collected from the independent sites are listed in Supplementary Tables 1–3. Overall, the demographic characteristics (age, gender and ethnicity) of the IPAF cohort fell between the IPF and CTD-ILD cohorts. The most common CTD subtypes represented in the combined CTD-ILD cohort were scleroderma (30%, 74/248) and rheumatoid arthritis (25%, 62/248).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF), and Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD)

| IPF (N=499) |

IPAF (N=250) |

CTD-ILD* (N=248) |

p-value for Comparison across Diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.7 (9.6) | 60.5 (11.1) | 53.8 (13.4) | <0.0001 |

| Male Gender, N (%) | 368 (74) | 112 (45) | 70 (28) | <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 437 (87) | 170 (68) | 138 (56) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 34 (7) | 26 (10) | 30 (12) | |

| Black | 17 (4) | 36 (14) | 75 (30) | <0.0001 |

| Asian | 6 (1) | 12 (5) | 5 (2) | |

| Other or Unknown | 5 (1) | 6 (2) | 0 | |

| Ever Smoker, N (%) | 317 (66) | 134 (54) | 105 (42) | <0.0001 |

| Family History | 61 (20) | 10 (4) | 7 (3) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary Function Test | ||||

| FVC % predicted, mean (SD), N | 67 (18), 418 | 64 (19), 228 | 68 (19), 214 | 0.08 |

| DLCO % predicted, mean (SD), N | 47 (17), 386 | 48 (18), 212 | 53 (20), 197 | 0.001 |

| Telomere Length | N=499 | N=244 | N=248 | |

| Observed-Expected, mean (SD), N | −0.17 (0.32) | −0.05 (0.29) | −0.04 (0.25) | <0.0001† |

| <10th percentile, N (%) | 156 (31) | 40 (16) | 32 (13) | <0.0001† |

| Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, MAF (95% CI), N‡ | ||||

| MUC5B rs35705950 | 34.2 (31.1–37.5), 437 | 23.2 (18.8–28.2), 166 | 19.9 (15.5–25.2), 138 | <0.0001§ |

| TOLLIP rs5743890 | 12.4 (10.3–14.8), 437 | 15.0 (11.4–19.5, 163 | 14.2 (10.4–19.1), 137 | 0.42 |

| Follow-up in years, median (IQR) | 2.97 (1.54–4.86) | 2.86 (1.25–3.71) | 4.60 (1.88–8.21) | <0.0001 |

| Disease Progressionǁ | ||||

| Δ FVC % predicted/year, % (95% CI), N | −5.37 (−6.10, −4.66), 212 | −1.80 (−2.70, −1.0), 163 | −0.64 (−0.99, −0.30), 181 | <0.0001 |

| Survival | ||||

| Median Transplant-Free Survival, years (95% CI) |

3.75 (3.48–4.40) | 5.61 (4.88–7.07) | 11.88 (9.18-NA) | <0.0001 |

CTD-ILD diagnoses include scleroderma (N=74), rheumatoid arthritis (N=62), mixed connective tissue disease (N=35), dermatomyositis (N=22), polymyositis (N=18), anti-synthetase syndrome (N=3), primary Sjogren’s syndrome (N=20), systemic lupus erythematosus (N=12), polymyalgia rheumatic (N=2), overlap syndrome (N=2)

Bonferroni-corrected p-values for pairwise comparison between diagnoses for telomere length: IPF vs IPAF p<0.0001, IPF vs CTD-ILD p<0.0001, IPAF vs CTD-ILD p=1.0

Restricted to non-Hispanic white patients

Bonferroni-corrected p-values for pairwise comparison between diagnoses for MUC5B MAF: IPF vs IPAF p=0.00088, IPF vs CTD-ILD p<0.0001, IPAF vs CTD-ILD p=1.0

Restricted to patients with ≥3 FVC measurements over span of ≥90 days

Abbreviations: FVC, forced vital capacity; DLCO, diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide, MAF, minor allele frequency

Genetic and Genomic Characteristic

Compared to IPF, age-adjusted LTL was longer for IPAF (−0.17, SD 0.32 versus −0.05, SD 0.29, padjust<0.0001) and CTD-ILD (−0.04, SD 0.25, padjust<0.0001) (Table 1). There were twice as many individuals with age-adjusted LTL below the 10th percentile among those with IPF (31%) than IPAF (16%) or CTD-ILD (13%). Within the CTD-ILD group, rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD (RA-ILD) had shorter age-adjusted LTL (−0.14, SD 0.27) compared to scleroderma associated ILD (SSc-ILD) (−0.02, SD 0.22, padjust=0.013) and the other CTD-ILDs (0.00, SD 0.24, padjust=0.00042) (Table 2). There were more RA-ILD patients with age-adjusted LTL < 10th percentile (26%) compared to SSc-ILD (12%) and other CTD-ILD (6%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with subtypes of Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD)

| RA-ILD (N=62) |

SSc-ILD (N=74) |

Other CTD-ILD* (N=112) |

p-value for Comparison across Diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 60.2 (10.5) | 48.0 (11.7) | 54.1 (14.2) | <0.0001 |

| Male Gender, N (%) | 21 (34) | 20 (27) | 29 (26) | 0.51 |

| Non-Hispanic White, N (%) | 40 (65) | 41 (55) | 59 (53) | 0.31 |

| Smoker, N (%) | 40 (65) | 17 (23) | 48 (43) | <0.0001 |

| Family History | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.065 |

| Telomere Length | ||||

| Observed-Expected, mean (SD) | −0.14 (0.27) | −0.02 (0.22) | 0.00 (0.24) | 0.00054† |

| <10th percentile, N (%) | 16 (26) | 9 (12) | 7 (6) | 0.0011† |

| Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, MAF (95% CI), N‡ | N=40 | N=41 | N=59 | |

| MUC5B rs35705950 | 34.6 (24.4–46.3) § | 16.2 (9.3–26.6) § | 12.7 (7.5–20.4) § | 0.00053ǁ |

| TOLLIP rs5743890 | 20.5 (12.5–31.5)ǁ | 7.7 (3.2–16.6)ǁ | 14.4 (8.9–22.3)¶ | 0.072 |

| Disease Progression** | ||||

| Δ FVC % predicted/year, % (95% CI), N | −0.59 (−1.33, 0.14), 89 | −1.03 (−1.62, −0.44), 54 | −0.41 (−0.91, 0.10), 89 | 0.61 |

| Survival | ||||

| Transplant-free survival, years (95% CI) | 6.32 (4.26-NA) | 11.88 (9.18-NA) | NA (9.83-NA) | 0.00054 |

Other CTD-ILD diagnoses include mixed connective tissue disease (N=35), dermatomyositis (N=22), polymyositis (N=18), anti-synthetase syndrome (N=3), primary Sjogren’s syndrome (N=20), systemic lupus erythematosus (N=12), polymyalgia rheumatic (N=2), overlap syndrome (N=2)

Bonferroni-corrected p-values for pairwise comparisons between diagnoses for telomere length: RA-ILD vs SSc-ILD p=0.013, RA-ILD vs Other CTD-ILD p=0.00042, SSc-ILD vs Other CTD-ILD p=1.0. RA-ILD compared to non-RA CTD-ILD p=0.00055.

Restricted to non-Hispanic White

Comparison of MUC5B rs35705950 MAF of non-Hispanic white normal controls (10.7, 95% CI 8.9–12.8) to RAILD (p<0.0001), SSc-ILD (p=0.19), other CTD-ILD (p=0.62)

Bonferroni-corrected p-values for pairwise comparisons between diagnoses for MUC5B MAF: RA-ILD vs SSc-ILD p=0.040, RA-ILD vs Other CTD-ILD p=0.0015, SSc-ILD vs Other CTD-ILD p=1.0. RA-ILD compared to non-RA CTD-ILD p=0.00025.

Comparison of TOLLIP rs5743890 MAF of non-Hispanic white normal controls (14.2, 95% CI 12.1–16.6) to RAILD (p=0.18), SSc-ILD (p=0.15), other CTD-ILD (p=1.0)

Restricted to patients with ≥3 FVC measurements over span of ≥90 days

Abbreviations: RA-ILD, rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease, SSc-ILD, scleroderma- interstitial lung disease, CTD, connective tissue disease, MAF, minor allele frequency

Compared to controls (20), the minor allele frequency (MAF) of the MUC5B rs35705950 SNP was higher in non-Hispanic white IPAF (23.2, 95% CI 18.8−28.2, padjust<0.0001) and CTD-ILD (19.9, 95% CI 15.5–25.2, padjust<0.0001) patients. However, compared to IPF (34.2, 95% CI 31.1–37.5), the MUC5B MAF was lower in both IPAF (padjust=0.00088) and CTD-ILD (padjust<0.0001) patients (Table 1). Within the CTD-ILD group, non-Hispanic white RA-ILD patients had a higher MUC5B MAF compared to SSc-ILD (34.6, 95% CI 24.4–46.3 versus 16.6, 95% CI 9.3–26.6, padjust=0.040) and the other CTD-ILDs (12.7, 95% CI 7.5–20.4, padjust=0.0015) (Table 2). In addition, the RA-ILD subgroup had a higher MUC5B MAF compared to controls (p<0.0001) while the MAF for SSc-ILD and other CTD-ILD group was similar to controls (p=0.19 and p=0.62, respectively). The MAF of the TOLLIP rs5743890 SNP was similar across the diagnostic groups and controls (20).

The distribution of LTL and MUC5B and TOLLIP SNPs between patients with usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) compared to non-UIP pattern were not entirely consistent across diagnostic categories. Telomere length was shorter in the IPAF UIP group versus the non-UIP group and there was a higher MUC5B minor allele frequency in the CTD-ILD UIP group versus the non-UIP group (Supplemental Table 5).

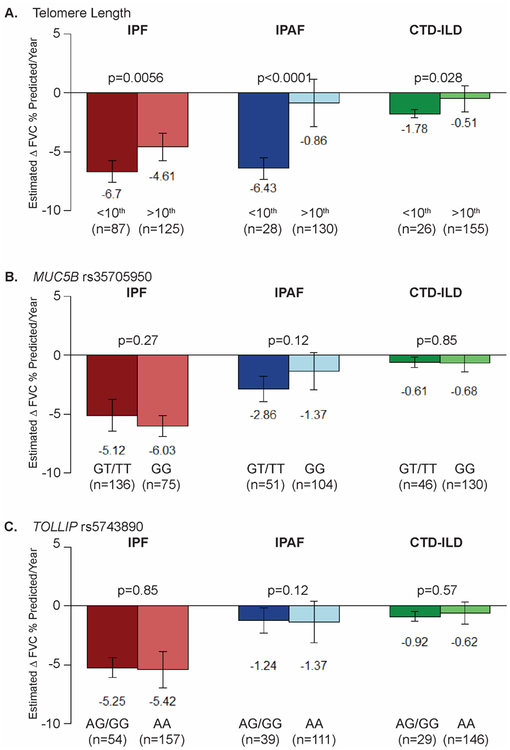

Pulmonary Disease Progression

Decline in FVC percent predicted per year was greater for IPF patients (−5.37, 95% CI −6.10, −4.66) than IPAF (−1.80, 95% CI −2.70, −1.00, padjust<0.0001) or CTD-ILD patients (−0.64, 95% CI −0.99, −0.30, padjustp <0.0001) (Table 1). Age-adjusted LTL <10th percentile was associated with a faster decline for IPF and IPAF (Figure 1A). For CTD-ILD, the LTL <10th percentile was associated with a trend toward faster decline in FVC % predicted (p=0.028) that did not reach significance (p<0.017) after accounting for multiple testing. The most dramatic difference was in the IPAF cohort where patients with LTL <10th percentile had −6.43% per year decline compared to −0.86% for those with LTL ≥10th percentile (p<0.0001). The MUC5B or TOLLIP genotypes (Figure 1B and 1C, respectively) were not associated with change in FVC percent predicted per year in IPF, IPAF or CTD-ILD patients.

Figure 1. Rate of pulmonary disease progression of Interstitial Lung Disease patients as measured by the mean change in FVC.

Estimated change of Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) percent predicted per year for patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF), and Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD) stratified by an age-adjusted blood leukocyte telomere length less than or greater than 10th percentile (A), by the presence of the MUC5B rs35705950 minor allele (GT/TT) (B), and by the presence of TOLLIP rs5743890 minor allele (AG/GG) (C). This analysis was limited to the subset of patients for which there were at least 3 spirometry measurements spanning over at least 90 days. Significant with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing with three predictors (LTL, MUC5B, TOLLIP) per diagnosis; alpha level of 0.017 per test (0.05/3)

Patient Survival

IPAF patients had longer median transplant-free survival when compared to IPF, but shorter compared to CTD-ILD (Table 1). Among the CTD-ILD cohort, the RA-ILD patients had worse transplant-free survival compared to scleroderma-ILD and the other CTD-ILDs (Table 2).

As has been previously shown in other IPF cohorts (11, 15, 16), LTL <10th percentile and the MUC5B minor allele were associated with transplant-free survival, but in opposite directions (Table 3). For IPAF, shorter LTL (HR 2.97, 95% CI 1.70–5.20, p=0.00014) and the MUC5B minor allele (1.92, 95% CI 1.18–3.13, p=0.0091) were both associated with worse transplant-free survival. For the CTDILD group, the MUC5B minor allele was associated with a trend toward worse transplant-free survival (HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.04–3.95, p=0.038) that did not reach significance (p<0.017) after accounting for multiple testing. The TOLLIP genotype was not associated with transplant-free survival in patients with IPAF or CTD-ILD. The results of the overall survival sensitivity analyses were similar (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3.

Associations between telomere length and single nucleotide polymorphisms with transplant-free survival for patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF), and Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD)

| IPF | IPAF | CTD-ILD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (events) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | N (events) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | N (events) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Telomere Length, <10th percentile | |||||||||

| Unadjusted | 499 (326) | 1.92 (1.52–2.44) | <0.0001† | 244 (102) | 2.75 (1.73–4.37) | <0.0001† | 248 (74) | 2.42 (1.3–4.51) | 0.0053† |

| Adjusted* | 386 (232) | 1.96 (1.46–2.62) | <0.0001† | 203 (85) | 2.97 (1.70–5.20) | 0.00014† | 197 (52) | 1.72 (0.84–3.49) | 0.14 |

| MUC5B rs35705950, TT/GT | |||||||||

| Unadjusted | 495 (324) | 0.65 (0.52–0.82) | 0.00018† | 240 (100) | 1.52 (1.01–2.28) | 0.046 | 243 (72) | 1.92 (1.18–3.12) | 0.0088† |

| Adjusted* | 384 (230) | 0.46 (0.34–0.62) | <0.0001† | 199 (83) | 1.92 (1.18–3.13) | 0.0091† | 194 (51) | 2.03 (1.04–3.95) | 0.038 |

| TOLLIP rs5743890, GG/AG | |||||||||

| Unadjusted | 495 (324) | 1.41 (1.10–1.81) | 0.0074 | 233 (98) | 0.65 (0.37–1.13) | 0.13 | 241 (71) | 0.90 (0.45–1.83) | 0.78 |

| Adjusted* | 384 (230) | 1.32 (0.98–1.79) | 0.072 | 193 (81) | 0.57 (0.30–1.08) | 0.083 | 192 (50) | 0.72 (0.32–1.66) | 0.44 |

Adjusted for age, gender, non-Hispanic white, baseline forced vital capacity percent predicted, baseline diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide percent predicted

Significant with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing with three predictors (LTL, MUC5B, TOLLIP) per diagnosis; alpha level of 0.017 per test (0.05/3)

Adding the UIP variable did not change the genomic associations with transplant-free survival. For the IPAF group, LTL <10th percentile (HR 2.51, 95% CI 1.44–4.39, p=0.0012) and the MUC5B minor allele (HR 1.90, 95% CI 1.12–3.23, p=0.014) were still associated with worse transplant-free survival, while the TOLLIP minor allele was not (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.35–1.30, p=0.24). In the CTD-ILD group, none of the genomic predictors were associated with transplant-free survival (LTL HR 1.64, 95% CI 0.80–3.22, p=0.18; MUC5B HR 1.87, 95% CI 0.89–3.90, p=0.097; TOLLIP HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.28–1.55, p=0.35) after adding UIP to the model.

In the model that included LTL and the MUC5B genotype as covariates, both were independently associated with transplant-free survival for patients with IPF, but in opposite directions (Table 4). For IPAF, LTL <10th percentile was associated with worse transplant-free survival (HR 2.63, 95% CI 1.47–4.69, p=0.0011) after adjusting for MUC5B genotype.

Table 4:

Independent associations of telomere length and the MUC5B rs35705950 single-nucleotide polymorphism for transplant-free survival in patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF), and Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD)

| p-value | p-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere Length, <10th percentile | <0.0001† | 0.0011† | 0.25 |

| MUC5B rs35705950, TT/GT | <0.0001† | 0.060 | 0.049 |

Adjusted for telomere length <10th percentile, MUC5B rs35705950 TT or GT genotype, age, gender, non-Hispanic white, baseline forced vital capacity percent predicted, and baseline diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide percent predicted

Significant with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing with three predictors (LTL, MUC5B, TOLLIP) per diagnosis; alpha level of 0.017 per test (0.05/3)

Discussion

The evaluation of interstitial lung disease hinges on classification into discrete ILD subtypes to infer expectations regarding disease course, treatment, and prognosis. Classification can be challenging when patients do not fit neatly within the IPF and CTD-ILD categories, as is the case for IPAF. In this multicenter cohort study, the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with IPAF fall between those of IPF and CTD-ILD. Fewer IPAF and CTD-ILD patients have short LTL (<10th percentile) compared to IPF. However, short LTL is associated with faster lung function decline and worse transplant-free survival in IPAF, similar to IPF. The MUC5B MAF is higher in IPAF patients compared to controls, and the minor allele is associated with worse transplant-free survival for these patients. The CTD-ILD group as a whole also had higher MUC5B MAF compared to controls, but this is largely due to the higher MAF in the RA-ILD sub-group.

Determining if the IPAF classification criteria identifies patients that are truly distinct in terms of disease behavior, prognosis, or response to therapy compared to IPF or CTD-ILD is clinically important. However, prior studies comparing prognosis of IPAF to either CTD-ILD or IPF demonstrate inconsistent results (7, 21). Perhaps these inconsistencies are due to differences in cohort composition with regard to LTL and MUC5B. In this multicenter cohort study, IPAF patients differ from IPF and CTD-ILD in terms of demographics, rate of progression, and overall prognosis. In addition, the distribution of the LTL and MUC5B genotype differ between IPAF and IPF. Half as many IPAF patients have short LTL compared to IPF, but IPAF patients with short LTL have faster lung function decline and poor survival. In fact, dichotomizing IPAF by LTL ≥ or <10th percentile distinguishes two groups of patients whose rates of lung function decline resembles those of CTDILD and IPF patients, respectively. The MUC5B minor allele is overrepresented in patients with IPAF compared to controls, but the minor allele frequency is still significantly lower than IPF. The MUC5B minor allele is associated with worse, not better, transplant-free survival in IPAF, which is opposite of its effect on IPF. These genome markers, therefore, identify specific endotypes within each ILD subgroup that have different rates of progression and survival characteristics.

CTD-ILD represents a collection of various systemic autoimmune disorders that result in lung fibrosis. Patients with CTD-ILD differ from IPF in terms of mechanism of disease, demographics of affected patients and clinical course. Genomic markers associated with IPF are less prevalent in CTDILD group as a whole. The mean LTL for CTD-ILD patients is only slightly shorter than the expected age-adjusted length (14, 22), and LTL has not been previously associated with transplant-free survival in CTD-ILD patients (14). In addition, prior studies of patients with scleroderma-ILD and other CTD-ILDs found no difference in the minor allele frequency for MUC5B rs35705950 compared to controls (23–26).

Although these genomic markers do not predict clinical outcomes for the combined CTD-ILD group, they may identify a subgroup of CTD-ILD patients, such as those with RA-ILD, who may have a higher risk for poor outcomes. Compared to the CTD-ILD group as a whole, patients with RA-ILD bear a closer resemblance to IPF. RA-ILD and IPF patients share demographic features such as older age and a higher proportion males and smokers (27–30). In contrast to other CTD-ILDs, patients with RA-ILD often present with radiographic and histopathologic usual interstitial pneumonia, which is the pathognomonic pattern of fibrosis in IPF (31, 32). In the current study, not only do RA-ILD and IPF patients have overlapping clinical features, they also have overlapping genomic characteristics. The proportion of RA-ILD patients with LTL <10th percentile is similar to IPF (25% and 31%, respectively) as opposed to the other non-RA CTD-ILD patients (9%). A recent study by Juge et al found that the MUC5B minor allele is overrepresented in patients with RA-ILD and is specifically associated with a UIP pattern (33). We found that patients with RA-ILD have similar overrepresentation of the MUC5B minor allele as IPF (34.6 and 34.2, respectively); in contrast, the other non-RA CTD-ILD patients have similar MUC5B MAF compared to controls (14.4 and 10.7, respectively). A previous study identified rare, likely pathogenic variants in telomere-related genes (TERT, RTEL1, and PARN) in patients with RA-ILD (34) similar to those described in sporadic and familial IPF (35–39). Unfortunately this study did not provide a large enough sample size to determine if the genomic predictors, namely LTL and the MUC5B minor allele, are associated with differential survival risk in RA-ILD as they are in IPF. In particular, it would interesting to see if the MUC5B minor allele is associated with worse survival as in IPAF, or better survival as in IPF.

This study has a number of limitations. As an observational cohort study, our results represent associations and not causal relationships between the genomic markers and clinical outcomes. Genomic DNA was isolated at each site using different methods that may influence multiplex qPCR measurements. Biologic samples of fresh blood were unavailable for measurement of telomere length by the more precise methods (40). However, similar trends of telomere length measurements within diagnostic groups are found across sites. And the associations between LTL and IPF survival have been replicated by independent investigators using methods of measuring LTL that include flow cytometry, PCR and genomic sequencing (12, 14–16). Each center assigned diagnoses based on retrospective review of clinical information, therefore availability of testing at each center may have biased the patient populations. While all IPAF patients fulfilled pre-defined criteria, heterogeneity across sites remained. Unlike IPF where the accepted diagnostic criteria have been honed over decades, IPAF is a recent designation that will likely undergo revision as the criteria continue to be studied. In our analysis we attempted to correct for differences by using multivariable models that stratified by cohort. Sample sizes of patients with discrete CTD-ILD subtypes were small, thus, limiting our ability to explore the relationship between genomic markers and disease outcomes within CTD-ILD subgroups. We did not assess the influence of treatment on clinical outcomes across genomic characteristics and ILD diagnoses.

This study is the first to characterize the associations between two genomic markers (MUC5B SNP and LTL) and clinical outcomes for IPAF and CTD-ILD patients collected from three independent academic medical centers. For patients with IPAF, as with IPF, both of these genomic markers are independently associated with survival. In addition, for IPAF patients LTL is independently associated with FVC progression. It remains to be seen how these markers might be used in clinical practice. Optimal therapeutic treatment of IPAF patients is not currently clear. Should they be treated with anti-fibrotic medications like IPF patients or immunosuppressive therapies like CTD-ILD patients? Prospective studies are needed to answer this very important question and to determine if genomic features will identify patients that may have differential response to specific therapies.

Supplementary Material

Take home message:

“The leukocyte telomere length and MUC5B minor allele frequency are similar for IPAF and the combined CTD-ILD group, however the associations between these genomic markers and clinical outcomes are different for these two types of ILD.”

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study participants, to Tyonn Barbera, Cassandra Hamilton, and Ross Wilson (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA) for help with patient recruitment and technical excellence.

Support Statement

The authors acknowledge funding support provided by the National Institutes of Health R01 HL09309 (CKG) and KL2TR001103 (CAN), K23HL13890 (JMO), and KL2TR001870 (BL), and R01HL130796 (IN).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has recently been accepted for publication in the European Respiratory Journal. It is published here in its accepted form prior to copyediting and typesetting by our production team. After these production processes are complete and the authors have approved the resulting proofs, the article will move to the latest issue of the ERJ online.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183(6):788–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research N, Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1968–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(9):708–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vij R, Strek ME. Diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2013;143(3):814–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer A, Brown KK, Du Bois RM, Frankel SK, Cosgrove GP, Fernandez-Perez ER, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil improves lung function in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(5):640–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer A, Antoniou KM, Brown KK, Cadranel J, Corte TJ, du Bois RM, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):976–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldham JM, Adegunsoye A, Valenzi E, Lee C, Witt L, Chen L, et al. Characterisation of patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(6):1767–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1503–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(4):309–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peljto AL, Zhang Y, Fingerlin TE, Ma SF, Garcia JG, Richards TJ, et al. Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dressen A, Abbas AR, Cabanski C, Reeder J, Ramalingam TR, Neighbors M, et al. Analysis of protein-altering variants in telomerase genes and their association with MUC5B common variant status in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a candidate gene sequencing study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton CA, Batra K, Torrealba J, Kozlitina J, Glazer CS, Aravena C, et al. Telomere-related lung fibrosis is diagnostically heterogeneous but uniformly progressive. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(6):1710–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuart BD, Lee JS, Kozlitina J, Noth I, Devine MS, Glazer CS, et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an observational cohort study with independent validation. The lancet Respiratory medicine. 2014;2(7):557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai J, Cai H, Li H, Zhuang Y, Min H, Wen Y, et al. Association between telomere length and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2015;20(6):947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snetselaar R, van Batenburg AA, van Oosterhout MFM, Kazemier KM, Roothaan SM, Peeters T, et al. Short telomere length in IPF lung associates with fibrotic lesions and predicts survival. PloS one. 2017;12(12):e0189467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, Elicker BM, Henry TS, Vittinghoff E, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. The lancet Respiratory medicine. 2017;5(8):639–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, Chin KM, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, et al. Telomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(7):729–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz de Leon A, Cronkhite JT, Katzenstein AL, Godwin JD, Raghu G, Glazer CS, et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5):e10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad K, Barba T, Gamondes D, Ginoux M, Khouatra C, Spagnolo P, et al. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: Clinical, radiologic, and histological characteristics and outcome in a series of 57 patients. Respir Med. 2017;123:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snetselaar R, van Moorsel CH, Kazemier KM, van der Vis JJ, Zanen P, van Oosterhout MF, et al. Telomere length in interstitial lung diseases. Chest. 2015;148(4):1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borie R, Crestani B, Dieude P, Nunes H, Allanore Y, Kannengiesser C, et al. The MUC5B variant is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease in the European Caucasian population. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock CJ, Sato H, Fonseca C, Banya WA, Molyneaux PL, Adamali H, et al. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2013;68(5):436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peljto AL, Steele MP, Fingerlin TE, Hinchcliff ME, Murphy E, Podlusky S, et al. The pulmonary fibrosis-associated MUC5B promoter polymorphism does not influence the development of interstitial pneumonia in systemic sclerosis. Chest. 2012;142(6):1584–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Vis JJ, Snetselaar R, Kazemier KM, Ten Klooster L, Grutters JC, van Moorsel CH. Effect of Muc5b promoter polymorphism on disease predisposition and survival in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respirology. 2016;21(4):712–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly CA, Saravanan V, Nisar M, Arthanari S, Woodhead FA, Price-Forbes AN, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: associations, prognostic factors and physiological and radiological characteristics--a large multicentre UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle TJ, Dellaripa PF, Batra K, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Hatabu H, et al. Functional impact of a spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 2014;146(1):41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weyand CM, Schmidt D, Wagner U, Goronzy JJ. The influence of sex on the phenotype of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):817–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saag KG, Cerhan JR, Kolluri S, Ohashi K, Hunninghake GW, Schwartz DA. Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(8):463–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim EJ, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern. Chest. 2009;136(5):1397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assayag D, Elicker BM, Urbania TH, Colby TV, Kang BH, Ryu JH, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: radiologic identification of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern. Radiology. 2014;270(2):583–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juge PA, Lee JS, Ebstein E, Furukawa H, Dobrinskikh E, Gazal S, et al. MUC5B Promoter Variant and Rheumatoid Arthritis with Interstitial Lung Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juge PA, Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Gazal S, Revy P, Wemeau-Stervinou L, et al. Shared genetic predisposition in rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease and familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrovski S, Todd JL, Durheim MT, Wang Q, Chien JW, Kelly FL, et al. An Exome Sequencing Study to Assess the Role of Rare Genetic Variation in Pulmonary Fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2017;196(1):82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Raghu G, Weissler JC, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(18):7552–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(13):1317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, Xing C, Holohan B, Chen R, et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):512–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannengiesser C, Borie R, Menard C, Reocreux M, Nitschke P, Gazal S, et al. Heterozygous RTEL1 mutations are associated with familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(2):474–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Santana-Lemos BA, Scheucher PS, Alves-Paiva RM, Calado RT. Direct comparison of flow-FISH and qPCR as diagnostic tests for telomere length measurement in humans. PloS one. 2014;9(11):e113747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.