Abstract

Barriers to health care access and utilization are likely to be perceived differently for receivers and providers of health care. This paper compares and contrasts perspectives of lay community members, volunteer community health advisors (CHA), and health care providers related to structural and interpersonal barriers to health care seeking and provision among African American adults experiencing health disparities in the rural Mississippi Delta. Sixty-four Delta residents (24 males, 40 females) participated in nine focus groups organized by role and gender. The constant comparative method was used to identify themes and subthemes from the focus group transcripts. Barriers were broadly categorized as structural and interpersonal with all groups noting structural barriers including poverty, lack of health insurance, and rurality. All groups identified common interpersonal barriers of gender socialization of African American males, and prevention being a low priority. Differences emerged in perceptions of interpersonal barriers between community members and healthcare providers. Community members and CHA noted fears of serious medical diagnosis, stigma, medical distrust, and racism as factors inhibiting health care utilization. All groups were critical of insurance/regulatory constraints with providers viewing medical guidelines at times restricting their ability to provide quality treatment while community members and CHA viewed providers as receiving compensation for prescribing medications without regard to potential side-effects. These findings shed light on barriers perceived similarly and differently across these stakeholder groups, and offer directions for ongoing research, outreach, clinical work, and health care policy.

Keywords: African American, Mississippi Delta region, Barriers to healthcare seeking, Barriers to healthcare provision

Introduction

The Kaiser Family Foundation recently reported the poor state of health and health coverage in the South, a region with 37% of the total U.S. population and a higher percentage of people of color (42%) than the other three U.S. census regions, including notably 58% of all Blacks in the U.S.[1]. The South has a higher rate of poverty than the other regions, as well as poorer status for several commonly tracked health outcomes, including obesity, diabetes, and infant mortality, and for health insurance coverage. In 2018, the United Health Foundation ranked Mississippi 47th or lower for its four composite health measures: outcomes, behaviors, Clinical Care, and Community and Environment [2]. At the time of the current study, the nine counties comprising the Delta/Hills Public Health District in rural northwest Mississippi had a population of 216,708 [3,4] and included seven counties in the lowest Mississippi quartile for health outcomes, and six in the lowest quartile for health factors, including health care access [5].

Poverty and health care professional shortages are contributors to access and utilization in Mississippi [4,6–8], and research from other areas of the country suggests similar structural barriers, emerging from social and historical events such as segregation and racism, contribute to low engagement of African Americans with health care systems and providers [9–11]. Studies of barriers from patient/community members’ perspectives reveal both structural and interpersonal factors as operative in limiting health care access and utilization. Structural barriers named by patients included poverty, transportation, lack of insurance and anticipated cost of services, and limited availability of health care [12–17]. Medical distrust and discrimination/racism appear in many studies of low-income, ethnic minority populations as interpersonal barriers to seeking health care [10,11,16,17].

Barriers are likely to be perceived differently by receivers and providers of health care. In a study in two rural states, Alaska and New Mexico, providers identified interpersonal barriers they felt impacted their patients’ health care utilization, including fear of stigma associated with having a disease or seeking help, lack of social support, and fear of providers breaking confidentiality [18]. When both patients and providers were questioned about perceived barriers to HIV care in South Africa [19], both groups recognized stigma as a barrier to seeking HIV care. However, providers minimized stigma and perceived that patients had more control over stigma than patients themselves perceived. Little else has been published contrasting perspectives of different community stakeholders related to structural and interpersonal barriers to health care access and utilization. In order to improve health care seeking and provision in rural populations experiencing health disparities, it is important to identify barriers from differing perspectives, including users and potential users of health care information and services as well as health care providers. This paper compares and contrasts perspectives of lay community members, volunteer community health advisors (CHAs), and health care providers related to structural and interpersonal barriers to health care seeking and provision among African American adults experiencing health disparities in the rural Mississippi Delta.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment Procedures

Representatives of three stakeholder groups, health care providers, CHAs, and African American community members, were recruited from the 9-county public health district to participate in focus groups related to health care seeking and provision. Community members included those who had and had not interacted with CHAs in their health care decision making.

Health care providers were recruited from federally qualified health centers, a local hospital, and the state health department. CHAs were recruited from a local grassroots CHA network, the Mississippi Network for Cancer Control and Prevention (MSNCCP), using records of training rolls. The MSNCCP has successfully engaged African Americans in the rural Delta with health promotion efforts since the late 1980s [20], thus these men and women could have important insight into factors influencing health care seeking and provision. Lay community members with previous CHA interaction were recruited using MSNCCP contact records. A research staff member who was a Delta resident recruited those without prior CHA contact, using personal contacts and word of mouth. All recruitment activities were coordinated by trained field staff. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Focus Group Procedures

Nine focus groups were conducted in two centrally located counties/communities in the public health district, in private meeting areas at times and locations convenient to participants. Written consent was obtained from each participant following a preliminary oral presentation with the opportunity for questions about procedures. CHA and community member groups were divided by gender because MSNCCP CHAs functioned separately by gender, and based on the researchers’ prior experience conducting focus groups on health with men in the Delta [21]. Separate groups were also conducted for lay community members who had or had not had previous CHA interactions.

Interview protocols were developed by the project team for each of three groups to ask about their respective perspectives on health care seeking and provision, including how they used health care information and made decisions about health care. Two project staff members trained and experienced in conducting focus groups [22] led each group. One served as moderator while the other served as assistant and kept field notes of each group. For the CHA/community member focus groups, both moderators were African American females with masters’ degrees. The first author, a White female, conducted the provider focus group, assisted by one of the staff moderators previously mentioned. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed methods described by Braun & Clarke [23] and King [24]. Transcripts of each focus group were reviewed independently by the first two authors, followed by line by line coding to identify categories of information. Next, related codes were organized into larger groups (themes) and axial coding was then used to connect relationships between the thematic groups. Using a constant comparative approach, categories were saturated by identifying the same categories until there was no longer new information. The two coders independently analyzed all transcript data and met on a regular basis to discuss the consistency of their responses to the codes. When differences in coding were noted, they were discussed and consensus achieved. Constant comparative analysis identified recurring themes among the categories as well as between groups.

Creswell and colleagues [25] have recommended writing the results so as to provide rich, thick, detailed description to highlight the closeness of the researcher to the participants and then soliciting stakeholders’ views on the credibility of the findings and the interpretations made. Regarding the latter, representatives from the different stakeholder groups reviewed the preliminary analyses and provided feedback on the accuracy of the interpretation of the descriptions and themes. Further, the research team applied reflexivity to the research process to help insure validity of the process and data, as reported in Wang et al. [21].

We present results in the following format: structural and interpersonal barriers identified across all participant groups; structural barriers identified only by community/CHA groups and by health care providers, respectively, and interpersonal barriers identified only by community/CHA groups. Providers identified no interpersonal barriers that differed from community/CHA groups.

Results

Table 1 presents participant demographics. All CHA and lay community member participants were African American. The provider group included African Americans and one person of other race/ethnicity not further specified and was comprised of physicians and certified nurse practitioners. Sixty-eight percent of participants were between the ages of 45–64 (data not shown). The themes identified for CHA and lay community member groups and for male and female groups were similar; therefore, we report results for these groups together, pointing out distinctions where they existed.

Table 1.

Stakeholder Groups Participating in Focus Group Sessions.

| Stakeholder Group | Number of Focus Groups | Gender | Total Number of Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Community Health Advisors (CHA) | 3 | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| Community Members | ||||

| With CHA Contact | 3 | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| Without CHA Contact | 4 | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| Healthcare Providers | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Totals | 11 | 24 | 40 | 64 |

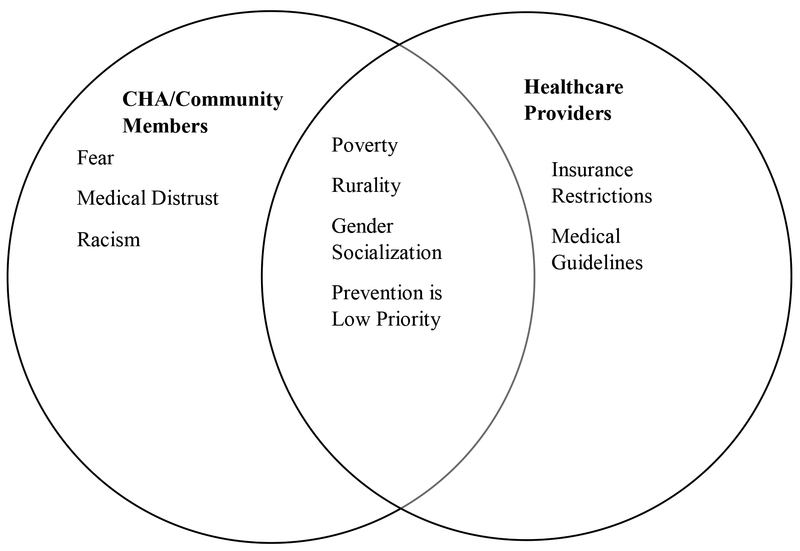

All barriers to health care seeking and provision identified in data analysis fell into two overarching categories: structural/environmental and interpersonal. Commonalities and differences are illustrated in the Figure, and Table 2 presents the themes and subthemes within the two categories.

Figure.

: Community Members’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Commonalities and Differences in Barriers to Healthcare Seeking and Provision

Table 2.

Structural and Interpersonal Barriers to Healthcare Seeking and Provision.

| Structural Barriers | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Subtheme |

| Poverty | Unemployment/underemployment |

| Lack of health insurance/lack of money for co-pays, medication | |

| Choosing between bills, co-pays, or medication | |

| Apathy | |

| Rurality | Lack of public and private transportation |

| Lack of Medical Specialists | |

| Insurance Restrictions | Restricted treatments/medications |

| Wait times for treatment approvals | |

| Medical Guidelines | Guidelines constantly change/cycle |

| Guidelines could limit individualize patient care/clinical judgement | |

| Economic Influences | |

| Racism | Feeling disrespected |

| Apathy | |

| Interpersonal Barriers | |

| Fear | Stigma of illness |

| Fear of severity of illness/death | |

| Fear of medication and side effects | |

| Prevention of disease is low priority | Care taking/family provider responsibilities |

| No need to seek healthcare as long as physical ability is not impacted | |

| Gender and gender socialization | Seeking healthcare is a feminine activity |

| African American men are socialized to be “macho” | |

| African American men do not discuss personal health issues | |

| Medical distrust | Kickbacks from pharmaceutical/insurance companies dominate physician’s provision of care |

| Feeling that healthcare provider is impersonal/uncaring/does not listen | |

Structural Barriers Identified by All Stakeholder Groups

Structural barriers mentioned throughout the interviews included living in poverty, in a rural region, with the associated effects of high unemployment rates, lack of health insurance, lack of medical specialists, and difficulties with transportation to access health care services. In particular, poverty combined with lack of health insurance was mentioned across almost all of the interviews as exemplified by this quote:

I think a lot of people either don’t have insurance or … money for the appointment, or if they do go and pay …, they don’t have money for the prescriptions. So, some of them just…choose not to go. [Female community member]

The lack of public and private transportation as a subtheme of rurality also was mentioned as a significant barrier across all focus groups. Residents often had to rely on neighbors or others to provide transportation into towns for pay. Likewise, the lack of medical specialties such as gastroenterologists required patients to travel great distances for treatments not available in the immediate region.

Transportation is one of the major problems … because many people live outside [of town] and … don’t have transportation and to get…from this doctor’s office to another doctor’s office… They have to pay a sizable fee of $45 or $30. For someone who is living on social security [paying] is pretty hard, and we’re just talking about one [visit]. [Health care provider]

Interpersonal Barriers Identified by All Stakeholder Groups

All stakeholder groups identified two interpersonal barriers that they contextualized within African American culture: gender socialization, and prevention of disease as a low priority. Men spoke more about gender socialization than women. In particular, the men described their own feelings of defensiveness when it came to seeking preventative care. Going to a doctor or clinic was viewed as a feminine attribute. Men remarked how difficult it was because of the toll it would take on their masculinity. In the male groups, participants often reached consensus regarding how unlikely it was for men to seek help on their own, and how “weak” it would be to proactively go see a doctor. At the same time, they all recognized that this mentality was detrimental to their long-term well-being. The following quotes represent these themes.

… I think we [are] basically macho, you know...’he-mans’ and all of that…it’s weak that a person goes to the doctor all the time. [Male CHA]

Every time our wives, anything happen[s], swoosh, they go straight to the doctor…Every time [something] happen[s] [to us], we don’t run up there like that…statistics show that [women] live longer than us and that’s the reason, ‘cause they go to the doctor and they get checked. [Male CHA]

One salient message in our interviews had to do with the lack of attention placed on seeking health care until a critical incident occurred, such as when an acute problem required immediate medical attention. We denoted this as “prevention of disease is low priority.” The subtheme the groups had in common was that many African Americans in the Delta did not seek health care until they became older and/or as long as physical health or ability to work were not impacted.

I’ve got guys that are 50 years old that have never been to the doctor and I said, ‘Well why haven’t you?’ ‘I don’t know. I always felt fine.’ And then, you come to find out they have metastatic disease, but the previous 50 years they have always felt fine. [Health care provider]

Structural Barriers Identified by CHA/Community Members

Several themes and subthemes emerged from the CHA/lay community member groups that were not identified in the health care provider group. At the structural/environmental barrier level, historical and systemic levels of oppression toward the African American community were discussed as influencing the psyche of the community in the sense of agency or lack thereof that they experienced, preventing them from becoming proactive about their health.

… we are marginalized in the city whether we want to be or not, [because] we [are] excluded from the political process. We [are] excluded from the residential areas, the job markets. … I think a lot of that has played on the, psychology of a lot of Black people in this community, where they just don’t get involved, even with their own health, because of some of the other ill stuff that we have to deal with in the community, like the confederate stuff… [Male community member]

Racism was also described as having been perpetrated toward them in the health care process:

…[At this particular clinic], you ain’t going to see any Black faces in the reception office or in the finance office. These are young White girls. That’s the problem for me ‘cause the majority of their patients are Black and elderly. You know, the way they treat some of these people that come in the office is what really turn[s] you away… You know if you have an appointment at 1:00 and a Caucasian [person] come in and she doesn’t even have an appointment, she’s just a walk-in, but they take her before they take you and your child… So you find places where you’re comfortable…where you feel like you are appreciated. [Female community member]

[Dialysis is] the first thing the doctor thinks of when you’re Black and you have kidney issues, as opposed to let’s try [alternatives] with you. They [are] even talking about transplants with the Caucasian people, but we [are] going to get no transplants with the Blacks. You are going into the dialysis machine. [Female community member]

Some community members pointed out that long-term environmental deprivation contributes to people’s sense of motivation and initiative, decreasing the likelihood of taking preventative health action:

And I think a lot of that is just from being conditioned … and not having resources to do things with, so you become complacent and conformant to whatever your surrounding is and in your environment.” [Male community member]

Structural Barriers Identified by Health Care Providers

Health care providers identified their own structural barriers that impeded health care service provision, particularly quality care current with practice guidelines. Two broad themes emerged. The first was insurance restrictions, referring to the limitations placed on the types of treatments covered, the requirements needed for pre-approval, delaying treatment, and the hurdles providers faced in referring patients to specialty medical practices. The quotes below provide examples of the ways in which providers face inconsistencies between changing medical guidelines and available resources for their patients.

… the newest guidelines according to the DHHS for treatment of HIV/AIDS…were released in May and the medicines that were considered first line are not covered by Medicaid. We have to do prior authorizations to get those medicines and then the state program, AIDS Drug Assistance Program, those are not the first drugs that you can give there either. So …to see the recommendations on one hand but see the things that are mostly available to your patients be something else, that’s quite difficult to deal with as a provider. [Health care provider 1]

So I tested a patient that had hepatitis B. The patient was positive, so I cannot give him Rituxan until I give him Lamivudine [according to practice guidelines], and my secretary comes to me and says, ‘… Medicare and his insurance don’t approve it because [I am] not a gastroenterologist.’ I mean it’s like in what other country does the secretary come to you because you are not that kind of doctor you cannot practice it. So [we] try to get him to see a gastroenterologist, which we don’t have, so three months later he got an appointment and his cancer will kill him. [Health care provider 2]

The second broad structural barrier, titled medical guidelines, related to evidence-based guidelines for treatment. Providers valued the need for staying current in their practices, but expressed concerns related to two subthemes: constant change, limiting individualized care/clinical judgement; and economic influences.

[Guidelines are] always changing and so it is almost [that] once the initial recommendation comes through and then people kind of pick up on it…[and] adapt, guess what, a new set of recommendations come through. [Health care provider 3]

It’s the guidelines that dictate [but]… some of the patients don’t fit, you know, into the guidelines. [Health care provider 2]

[regarding changes in recommendations for disease screening]… If there’s a driving force that says buy, buy, buy, sell, sell, sell, or pharm driven, then it says do more of that [particular screening]. If it’s possibly government driven that says let’s reduce costs then it’s let’s not be as aggressive and screen or treat certain conditions. [Health care provider 3]

Interpersonal Barriers Identified by CHAs/Community Members

CHAs/community members also identified interpersonal influences that perpetuated the lack of health care seeking for African American men and women in the Mississippi Delta. These included fear, medical distrust toward providers and insurance companies, and prevention of disease being a low priority due to overwhelming feelings of responsibility to provide instead of seek care.

The theme of fear was quite strong throughout the CHA and community member interviews and included subthemes, among them fear of learning of the severity of the illness, particularly a diagnosis of cancer, which was viewed as a death sentence. In the words of one community member, “… when I think I got this and I don’t want to go [to the doctor] ‘cause it might be bad news.” Thus, even when participants were aware that something was wrong and they needed health care, fear and subsequent denial prevented them from actively seeking services.

Another strong subtheme was fear of being stigmatized in the community for their health problems, that others would perceive them to be “less than.” Both genders viewed illness as a form of personal failure:

…I don’t know if we’re afraid of the stigma of being sick or, or don’t want people to think we’re weak. [Male community member]

I was ashamed because I didn’t want anybody to see me like that. I’m scared to go out among people because I know what you’re [going to] say…either [that] I had AIDS or I don’t have long to live. [Others might say] ‘she looked pitiful; I feel so sorry.’ I don’t want you to feel sorry for me, but I want you to love on me. [Female CHA]

Fear of taking a medication that would have serious side-effects or result in other health problems also emerged as a subtheme:

… I think that a lot of medications that [military] veterans are on are making their physical body worse than what the medicine is supposed to be helping. It’s creating other health problems, and unfortunately, health care providers don’t always explain to you that this medicine might cause this or these side effects and you don’t find out later till something else develops. [Male community member]

As suggested in the quote above, negative perceptions about health care providers also emerged as a salient theme, with community members expressing a general lack of trust toward doctors. They worried that providers would not consider the side effects of medication, and would not take the time to listen to and acknowledge patients’ concerns. Several participants mentioned seeking out providers who showed personal interest and empathy and would take the time to “sit down and give me a chance to talk.” Evidence of medical distrust was also apparent in the form of participants’ belief that some health care providers were receiving compensation from pharmaceutical companies for prescribing medication to patients.

…they…got these medical companies that [are]…going to give [them] kick-backs. So they don’t care what [prescription] you take. [Male CHA]

Finally, prevention of disease being a low priority was a common broad theme among all the groups, in the structural sense mentioned before, as well as in an interpersonal sense. The CHA/lay community member focus groups provided explanations for this lack of prioritization, relating that the feeling of being responsible for caring for the family was often a barrier to health care seeking and utilization. Daily stressors that were more pressing, like being able to pay the bills and to take care of one’s family, superseded participants’ motivation and decisions to take preventative action for their health.

Ain’t that we lazy or nothing like that, but if it ain’t got [nothing] to do with putting a dollar aside to try to pay this light bill, car note, or whatever, I don’t have time for it… [Male CHA]

…lot of our women and men are faced with cancer and they won’t quit [their] jobs because first of all, who [is going to] take care of Sally and Sue and little John [if they do]? [Female CHA]

Discussion

This study identified perspectives of multiple stakeholders, including lay community members, volunteer CHAs, and health care providers, related to barriers to health care seeking and provision among African Americans in the rural Mississippi delta region. Identified barriers fell into two broad categories, structural and interpersonal. All stakeholder groups identified poverty and rurality as overarching structural barriers. These barriers and their associated subthemes have previously been identified across a number of studies [12,16,26]. It was clear from our interviews that the subthemes worked together to magnify health disparities by increasing the challenges residents experience in health care seeking and access. For example, under/unemployment results in lack of adequate health insurance and resources to access medications, transportation, and medical services. And in this rural region, population density is insufficient to support specialty practices, requiring patients needing specialty services to secure costly transportation to travel to distant urban centers. Goins et al. [15] reported similar barriers for older adults living in rural West Virginia suggesting that similar results can be found across different rural and poor contexts.

As regards structural barriers that were not common across stakeholder groups, providers discussed the restrictions they felt were placed upon their practices and clinical judgment because of frequently changing guidelines and by third party payers’ (private or government) limits on payment for services and medications. Providers viewed the guidelines as a tug of war between pharmaceutical companies promoting the newest medication or treatment, and the federal government/insurance companies focused on curbing health care spending. To our knowledge, this particular barrier has not been identified previously by providers in published research. Thus, more work is needed to better understand providers’ struggles in navigating multiple third party payers’ restrictions while staying up-to-date with evolving practice guidelines, particularly in rural areas facing other structural barriers to provision of care. These challenges articulated by the providers were not voiced by the community members, whose only experiences with medical guidelines were from their individual and disease-specific treatment encounters.

The racism reported in this study by CHAs/community members, both in the providers’ offices and in the local community, is not unlike that reported as a barrier to health care access and utilization in other studies of African American men and women [9–11]. However, despite the long history of segregation and racism in the Mississippi delta, providers in this study did not mention racism as a barrier to health care seeking, access, or provision among delta residents. Their perception may have been affected by their own status as people of Color, or possibly influenced by the presence of a White moderator in contrast to having African American moderators for the other focus groups. Alternatively, the social and economic position of the providers in the community, in contrast to that of other group participants, might have influenced their responses.

All three groups identified gender and the gender socialization that occurs within the African American culture as strong influences on health care seeking and provision. In particular, health care seeking did not fit the cultural view of masculinity. “Working through” an illness was viewed as a strength, whereas seeing a provider for anything other than a problem that reduced physical ability was viewed as feminine or a sign of weakness. Further, a strong sense of being a provider for the family was mentioned by both men and women as a barrier to health care seeking until the condition became so serious that there was no choice but to go to the doctor. Others have reported masculinity and family provider responsibilities as barriers to preventive health care and health care seeking among African American men [27–29]. Althuogh the men in the CHA/community groups commented that going to the doctor regularly was viewed as a feminine activity, several noted that they only went to the doctor at the insistence of their wives, or because they realized, as they aged, that going to the doctor would enable them to continue to be active in their family roles and communities. Griffith, Allen, and Gunter [30] reported similar findings among urban African American men in Michigan.

Medical distrust has been reported as a structural barrier to preventive health screenings as well as to health care seeking and access among minority groups [10,11,13,16,17,28,31]. However, in our study, community participants described their distrust towards providers based on their interpersonal experiences with those who appeared impersonal or racially biased in the treatment options and care they provided. Cuevas et al. [10] reported medical distrust among African Americans in Portland when providers did not display respect toward their patients. Some participants in our study shared their suspicion that doctors were more interested in prescribing a particular medication to get compensation from the pharmaceutical company rather than caring for them as an individual. Our findings suggest that community members perceived providers to be a barrier in their health care utilization, whereas the providers we interviewed saw themselves as being aligned with their patients. Such inconsistency underscores the overlap between structural and interpersonal barriers that exacerbates health care under-utilization, as well as the need for improvements in patient provider communication that are currently being called for on many levels [32].

Relatedly, an interpersonal barrier that was prominent among community members, but not mentioned by providers, was fear. Fear of a serious diagnosis that could lead to death was an identified subtheme, and has been reported by other researchers studying delayed diagnosis of cancer [33,34]. Patients’ fear was not mentioned by providers, which may hinder providers’ ability to reach patients. Others have reported that fear of being stigmatized can result in treatment delays or avoidance among African Americans with a mental illness or HIV/AIDS diagnosis [19,35], as well as being associated with symptom distress among cancer patients [36]. One of the participants in our study spoke about the fear of being stigmatized by other community members for her cancer treatment. However, other comments related to fear of stigma were centered on being viewed as a weak person or not being able to fulfill role responsibilities. Further investigations should explore the different kinds of stigma underlying barriers to preventative and acute health care seeking, and treatment follow through.

This study is not without limitations. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants. However, for the lay community members with prior CHA contact, MSNCCP presence in the region for several years provided a broad sampling frame, and the fact that responses of both male and female CHAs and community members with and without prior CHA contact were similar could suggest that participants reflected the perceptions of the broader study population. That cannot be assumed for provider perspectives, however, with just a single group of five participants. Additionally, providers were asked about their own barriers to using the most current evidence-based treatment guidelines and not specifically about their patients’ barriers. Thus, some of the differences reported between providers and community members could arise from the way interview questions were framed, rather than being an indication that providers were unaware of barriers mentioned by community members.

Conclusions

This study provides a unique perspective of three different stakeholder groups on barriers to health care seeking and provision in a rural Southern state that is among the poorest in the U.S. for health outcomes. A number of the structural and interpersonal barriers noted by CHAs/community members and providers echoed those identified in other studies conducted in either African American or rural populations [10,15,21,27–29,33]. Distrust of providers and the health care system is a common finding. Provider perceptions of barriers may have shed some light on aspects of the distrust expressed by patients/community members, for example the community member perspective about racially driven treatment decisions vs. provider concerns about barriers to prescribing the medication of choice. The issue of lack of medical specialty practices in this rural area and restrictions on primary care providers also afforded a more nuanced look at treatment decisions as well as ways in which patient transportation challenges to appropriate care are exacerbated.

Community member perceptions of racism on the part of providers cannot be ignored however. Raising awareness among providers of patients’ perceptions in order to address them to the extent possible during patient encounters is also an important step in reducing delays in seeking health care and thus health disparities in the region. Providers and their office staff need to conscientiously seek to communicate with patients in ways that alleviate feelings of discrimination and being treated disrespectfully, such as acknowledging and discussing reasons for differential wait times [10,11], and expressing positive affective behavior [37]. Health education in rural areas should place more emphasis on early detection and treatment and its potential to positively impact not only patient but family quality of life, including developing culturally sensitive messages for encouraging health care seeking behavior.

The stigma with acknowledging illness experienced by community members in this study bears further exploration. The large body of literature on stigma associated with mental illness and HIV/AIDS does not extend to other chronic illnesses like heart disease or diabetes with high prevalence in Mississippi and the South. Approaches to understand and address stigma around mental illness/HIV/AIDS should be extended to better understand how this phenomenon deters African Americans in this rural region from health care seeking that could improve quality of life.

Community members and providers in southern rural areas likely face similar barriers to health care seeking and provision to those articulated by this study’s participants. These findings shed light on areas of commonalities as well as differences across these stakeholder groups, and offer directions for ongoing research, outreach, clinical work, and health care policy.

Acknowledgments

CLC, SCW, LC, and KY were partially supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®) Eugene Washington Engagement Award, Contract 1514-USM, during this work. CLC, LC, and KY also are partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5U54GM115428. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of PCORI®, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding The authors were partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®) Eugene Washington Engagement Award (1514-USM) during this work. CLC, LC, and KY also are partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5U54GM115428.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval The project was reviewed and approved by the University of Southern Mississippi and Santa Clara University Institutional Review Boards.

References

- 1.Artiga S, & Damico A Health and Health Coverage in the South: A Data Update.(2016). https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-and-health-coverage-in-the-south-a-data-update/. Accessed August 13, 2018.

- 2.United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings: Senior Report 2018. (2018). Minnetonka, MN: United Health Foundation; https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2018-senior-report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mississippi State Department of Health. Public Health District 3 - Mississippi State Department of Health. http://www.healthyms.com/msdhsite/_static/19,869,166.html. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 4.U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts. Population estimates, July 1, 2016, (V2016). //www.census.gov/quickfacts/. Accessed June 5, 2017.

- 5.University of Wisconsin, Population Health Institute, School of Medicine and Public Health. (2017). County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Building a Culture of Health, County by County. University of Wisconsin; http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/mississippi/2014/overview. Accessed November 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delta Regional Authority. Todays Delta: A Research Tool for the Region. (2016). http://dra.gov/images/uploads/content_files/DRA_Todays_Delta_2016.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 7.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Percent of Total Population in Poverty, 2015. https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17826. Accessed June 5, 2017.

- 8.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration Data Warehouse. https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/tools/analyzers/HpsaFindResults.aspx. Published 2016. Accessed June 14, 2017.

- 9.Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, & Rodgers SG (2008).Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by black men. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioner, 20(11), 555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuevas AG, O’Brien K, & Saha S African American experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over.” (2016). Health Psychology,35(9), 987–995. doi: 10.1037/hea0000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jupka KA, Weaver NL, Sanders-Thompson VL, Caito NM, & Kreuter MW (2008). African American adults’ experiences with the health care system: In their own words. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 2(3), 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed SM, Lemkau JP, Nealeigh N, & Mann B (2001). Barriers to healthcare access in a non-elderly urban poor American population. Health and Social Care in the Community, 9(6), 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Call KT, McAlpine DD, Garcia CM, et al. (2014). Barriers to care in an ethnically diverse publicly insured population: Is health care reform enough? Medical Care, 52(8), 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elpers J, Lester C, Shinn JB, & Bush ML (2016). Rural Family Perspectives and Experiences with Early Infant Hearing Detection and Intervention: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Community Health, 41(2), 226–233. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0086-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, Spencer SM, & Solovieva T (2005). Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: A qualitative study. Journal of Rural Health, 21(3), 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosavel M, Rafie C, Cadet DL, & Ayers A (2012). Opportunities to reduce cancer barriers: community town halls and provider focus groups. Journal of Cancer Education, 27, 641–648. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0423-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson A, Allen JA, Xiao H, & Vallone D (2012). Effects of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on health information-seeking, confidence, and trust. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(4), 1477–1493. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brems C, Johnson ME, Warner TD, & Roberts LW (2006). Barriers to healthcare as reported by rural and urban interprofessional providers. Journal of Interproffessional Care, 20(2), 105–118. doi: 10.1080/13561820600622208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogart LM, Chetty S, Giddy J, et al. (2013). Barriers to care among people living with HIV in South Africa: Contrasts between patient and healthcare provider perspectives. AIDS Care, 25(7), 843–853. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.729808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinton A, Downey J, Lisovicz N, Mayfield-Johnson S, & White-Johnson F (2005). The community health advisor program and the deep South network for cancer control: health promotion programs for volunteer community health advisors. Family and Community Health, 28(1), 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SC, Crook L, Connell C, & Yadrick K (2017). “We Need Help in the Delta”: Barriers to Health Promotion Among Older African American Men in the Mississippi Delta. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(2), 414–425. doi: 10.1177/1557988316684472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger RA (1999). Moderating Focus Groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King A (2008). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark-Plano VL, & Morales A Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. Counseling Psychology, 35(2), 236–264. doi: 10.1177/0011000006287390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen EM, Call KT, Beebe TJ, McAlpine DD, & Johnson PJ (2017). Barriers to care and health care utilization among the publicly insured. Medical Care, 55(3), 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blocker DE, Romocki LS, Thomas KB, et al. (2006). Knowledge, beliefs and barriers associated with prostate cancer prevention and screening behaviors among African-American men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(8), 1286–1295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Mohottige D, Agyemang A, & Corbie-Smith G (2010). Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community-dwelling African-American men. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(12), 1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose LE, Kim MT, Dennison CR, & Hill MN (2000). The contexts of adherence for African Americans with high blood pressure. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(3), 587–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffith DM, Ober-Allen J, & Gunter K (2011). Social and cultural factors influence African American men’s medical help seeking. Research in Social Work Practice, 21(3), 337–347. doi: 10.1177/104973151038866933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorburn S, Kue J, Keon K, & Lo P (2012). Medical mistrust and discrimination in health care: A qualitative study of Hmong women and men. Journal of Community Health, 37(4), 822–829. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9516-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou C (2018). Time to start using evidence-based approaches to patient engagement. NEJM Catalist. March 2018. https://catalyst.nejm.org/evidence-based-patient-provider-communication/. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Germeni E, & Schulz PJ (2014). Information seeking and avoidance throughout the cancer patient journey: two sides of the same coin? A synthesis of qualitative studies: A meta-ethnography on cancer information seeking and avoidance. Psychooncology, 23(12), 1373–1381. doi: 10.1002/pon.3575, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vos MS, de Haes JCJM (2007). Denial in cancer patients, an explorative review. Psychooncology, 16(1), 12–25. doi: 10.1002/pon.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempf MC, McLeod J, Boehme AK, et al. (2010). A Qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to retention-in-care among HIV-positive women in the rural southeastern United States: Implications for targeted interventions. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(8), 515–520. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finney JM, Hamilton JB, Hodges EA, Pierre-Louis BJ, Crandell JL, & Muss HB (2015). African American cancer curvivors: Do cultural factors influence symptom distress? Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26(3), 294–300. doi: 10.1177/1043659614524251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin KD, Roter DL, Beach MC, Carson KA, Cooper LA (2013). Physician communication behaviors and trust among black and white patients with hypertension: Medical Care, 51(2), 151–157. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]