Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and clinical factors affecting the glycemic response to dulaglutide in type 2 diabetes (T2D) in a real-world clinical setting.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of 234 patients at the Asan Medical Center, Republic of Korea, who had T2D and initiated dulaglutide from June 2016 to December 2017. The primary outcome was the change in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration between baseline and 6 months after the initiation of therapy. Multivariate regression analysis was used to determine the clinical parameters contributing to a superior glycemic response to dulaglutide.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 53, and 50% were male. Their mean baseline HbA1c, body mass index and duration of diabetes were 8.8%, 27.6 kg/m2 and 10.2 years, respectively. The change in HbA1c between baseline and 6 months was − 0.92% (95% CI: − 1.1% to − 0.74%, p < 0.001). The reduction in body weight over the same period was −2.1 kg (95% CI: − 2.9 to − 1.3 kg, p < 0.001). Using multivariate regression analysis, baseline HbA1c was found to be a significant predictor of superior glycemic response to dulaglutide.

Conclusion

The use of dulaglutide was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c and body weight over a 6-month period in a real-world clinical setting. T2D patients with higher baseline HbA1c concentrations were more likely to demonstrate good clinical responses to dulaglutide.

Electronic Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13300-019-0658-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Dulaglutide, Glucagon-like peptide 1, Type 2

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone that increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, inhibits glucagon secretion, slows gastric emptying and reduces appetite [1, 2]. Given these beneficial effects, various GLP-1 receptor agonists have been developed and are now being used for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Recently, a variety of guidelines [3–5], including the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), suggested GLP-1 receptor agonist as the preferred second option after failure to achieve adequate glycemic control using metformin and lifestyle modification. In addition, the ADA/EASD consensus report recommends the use of a GLP-1 receptor agonist in preference to insulin for patients who need the greater glucose-lowering effect of an injectable medication [6]. Moreover, GLP- 1 receptor agonists are a preferable option for Asian than Caucasian populations with T2D; the former need more focused treatment on postprandial glucose than on insulin resistance because of the unique characteristics of Asian patients such as impaired b-cell function [7].

Dulaglutide is a long-acting human GLP-1 receptor agonist that is administered weekly, and its efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in assessment of weekly administration of LY2189265 in diabetes (AWARD) trials [8–10] and several others [11–13]. However, few studies to date have demonstrated the efficacy of dulaglutide in a real-world setting. In addition, although few studies have investigated factors associated with glycemic response to dulaglutide, the findings obtained have been inconsistent [14–18], and the baseline characteristics contributing to the glycemic response to dulaglutide in a real-world setting have yet to be established. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the efficacy and clinical factors affecting the glucose-lowering response to dulaglutide in a real-world clinical setting.

Methods

Study Participants

Data from T2D patients attending the Asan Medical Center (AMC), Republic of Korea, who commenced treatment with dulaglutide between June 2016 and December 2017, and continued for at least 6 months, were retrospectively reviewed. Initially, 280 patients were included. Of these, patients who were on hemodialysis (n = 4), demonstrated cancer progression (n = 4), had missing baseline (n = 13) or 6-month (n = 5) HbA1c values, or were using dulaglutide in combination with insulin (n = 20) were excluded. Thus, data from 234 patients were eligible for analysis. In accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Korea Good Clinical Practice, this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center (2018-1050).

Efficacy of Dulaglutide

At baseline, data regarding age, sex, body weight, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, medical history, duration of diabetes, presence of hypertension or dyslipidemia, and concomitant medication were collected. In addition, the use of anti-hyperglycemic medication prior to dulaglutide treatment was reviewed. Laboratory measurements were conducted at baseline, including HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). All these measurements were repeated after 3 months (± 4 weeks) and 6 months (± 4 weeks) of dulaglutide treatment.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the efficacy of dulaglutide by assessing the change in HbA1c between baseline and 6 months. The secondary outcomes assessed after 6 months of treatment were the percentage of patients achieving the HbA1c target concentrations of < 7.0% or ≤ 6.5%, the change in body weight from baseline, fasting plasma glucose and blood pressure. After 3 months of treatment, the changes in HbA1c, FPG and body weight were also assessed.

Because this study was a retrospective, real-world study, there were no specific criteria to change the dose of dulaglutide. However, the dose of dulaglutide was increased from 0.75 mg to 1.5 mg mostly after a month of treatment. However, if patients had adverse events, had enough glycemic control with 0.75 mg of dulaglutide and/or did not want to increase the dose, it was not increased to 1.5 mg.

Clinical Parameters Affecting the Glycemic Response to Dulaglutide and Adverse Events

Clinical factors affecting the glycemic response of the patients to dulaglutide therapy were analyzed by multiple linear regression analysis. Next, patients were categorized into groups according to their age, BMI, baseline HbA1c and duration of diabetes, and the reductions in HbA1c were compared.

Adverse events were reviewed on the basis of the patients’ medical records during dulaglutide treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean (SD) for continuous variables and as a percentage for categorical variables. Student’s t-test and the χ2 test were used to compare the baseline characteristics of the study participants, categorized according to the degree of reduction in HbA1c achieved (≥ 1% or < 1%). The paired t-test was used to compare the changes in HbA1c, FPG, body weight and blood pressure between baseline and 6 months. A linear mixed model was used to analyze repeated measurements. The χ2 test was also used to compare the proportions of patients achieving the HbA1c target. Finally, univariate and multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine the clinical factors affecting the reduction in HbA1c achieved. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 for Windows (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The patients were categorized according to their change in HbA1c between baseline and 6 months (high response: HbA1c change ≥ 1% or low response: HbA1c change < 1%). In the complete cohort of dulaglutide-treated patients, the mean (SD) age was 53 (10) years, and 50% were male. The mean (SD) baseline HbA1c, BMI and duration of diabetes were 8.8% (1.4%), 27.6 kg/m2 (4.2 kg/m2) and 10.2 years (7.1 years), respectively. Of the patients, 8.1% of patients were in chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3, and 0.9% were in CKD stage 4. Dulaglutide-treated patients in the high response group had a higher mean baseline HbA1c than those in the low response group (9.4% vs. 8.3%). Patients in the high response group also tended to have higher C-peptide concentrations than those in the low response group (2.9 ng/dl vs. 2.5 ng/dl).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Total (n = 234) | HbA1c change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 1% (n = 107) | < 1% (n = 127) | p value | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 117 (50) | 60 (56.1) | 57 (44.9) | 0.088 |

| Female, n (%) | 117 (50) | 47 (43.9) | 70 (55.1) | |

| Age, years (SD) | 53 (10) | 53 (11) | 53 (10) | 0.997 |

| Body weight, kg (SD) | 74.4 (14.2) | 76.0 (16.0) | 72.9 (12.5) | 0.118 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 27.6 (4.2) | 27.9 (4.7) | 27.3 (3.9) | 0.283 |

| Diabetes duration, years (SD) | 10.2 (7.1) | 9.8 (7.1) | 10.3 (7.1) | 0.563 |

| HbA1c, % (SD) | 8.8 (1.4) | 9.4 (1.3) | 8.3 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| FPG, mg/dl (SD) | 181 (54) | 193 (58) | 171 (49) | 0.002 |

| SBP, mmHg (SD) | 131 (15) | 131 (16) | 132 (15) | 0.537 |

| DBP, mmHg (SD) | 74 (10) | 74 (10) | 74 (10) | 0.802 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl (SD) | 154 (33) | 151 (33) | 155 (34) | 0.338 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl (SD) | 47 (11) | 44 (10) | 48 (11) | 0.009 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl (SD) | 177 (105) | 181 (118) | 173 (94) | 0.575 |

| LDL-C, mg/dl (SD) | 97 (26) | 96 (23) | 99 (28) | 0.315 |

| C-peptide, ng/dl (SD) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.2) | 0.053 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl (SD) | 0.81 (0.32) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.743 |

| GFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 (SD) | 94 (20) | 95 (19) | 93 (20) | 0.329 |

| Dulaglutide dose n (%) | 0.051 | |||

| 0.75 mg | 53 (22.6) | 18 (16.8) | 35 (27.6) | |

| 1.5 mg | 181 (77.4) | 89 (83.2) | 92 (72.4) | |

| Hypertension | 168 (71.8) | |||

| On medication | 144 (61.5) | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 227 (97.0) | |||

| On medication | 210 (89.7) | |||

Data are expressed as mean (SD), median (interquartile range) or percentage (number)

BMI body mass index, FPG fasting plasma glucose, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, GFR glomerular filtration rate

Most of the patients (44.4%) had been treated with triple combinations of oral anti-diabetic drugs (OADs), and 29% were treated with a combination of insulin and OAD before initiating dulaglutide. At the time of initiating dulaglutide, 91% of patients were taking metformin and sulfonylurea, and 6% of patients were taking metformin, sulfonylurea and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (Table S1, Table S2).

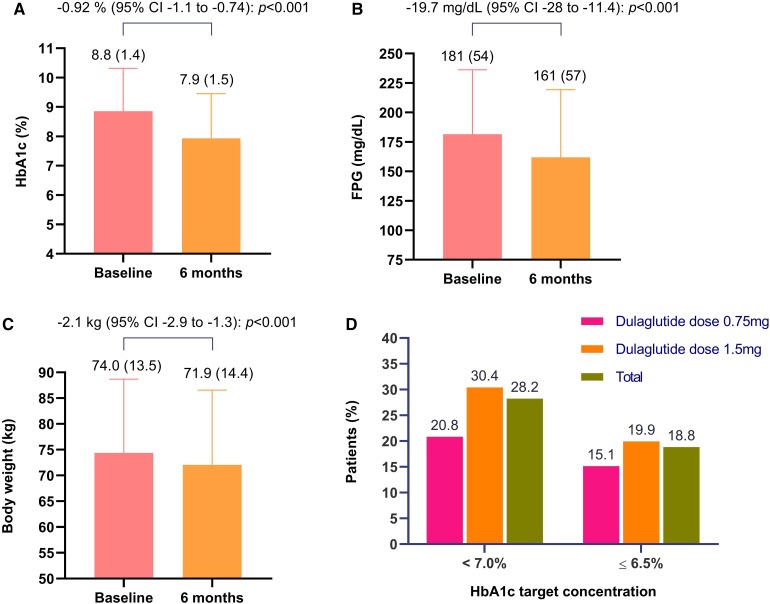

Efficacy of Dulaglutide

The change in HbA1c between baseline and 6 months was − 0.92% [95% confidence interval (CI): − 1.1 to − 0.74, p < 0.001; Fig. 1a]. The reduction in FPG concentration after 6 months of treatment was − 19.7 mg/dl (95% CI: − 28.0 to − 11.4, p < 0.001; Fig. 1b), and the reduction in body weight was − 2.1 kg (95% CI: − 2.9 to − 1.3, p < 0.001; Fig. 1c). The proportion of patients who achieved the HbA1c target concentrations of < 7.0% and ≤ 6.5% were 28.2% and 18.8%, respectively (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Efficacy measures a change in HbA1c between baseline and 6 months. b Change in fasting plasma glucose between baseline and 6 months. c Change in body weight between baseline and 6 months. d Percentages of patients achieving the HbA1c targets of < 7.0% or ≤ 6.5% after 6 months of treatment with dulaglutide

Among 234 patients who initiated dulaglutide, 48.7% (n = 114) did not change the dose of medication, and 46.2% (n = 108) decreased the dose of anti-diabetic medication. In patients who did not change the dose of oral anti-diabetic medication, the baseline HbA1c was 8.9%. In this group, the HbA1c reduction after 6 months of dulaglutide treatment was − 0.84% (95% CI: − 1.06 to − 0.62, p < 0.001). Even in patients with a decreased dose of medication, the efficacy in lowering HbA1c was consistent. In this group, the baseline HbA1c was 8.7% and the HbA1c reduction after 6 months of dulaglutide treatment was − 1.07% (95% CI: − 1.38 to − 0.75, p < 0.001) (Figure S1).

There were no differences in HbA1c changes between the groups who used metformin and sulfonylurea and who used another oral anti-diabetic medication when dulaglutide was initiated (HbA1c change: − 0.92% vs. − 1.0%, p = 0.817).

There were significant changes in HbA1c, FPG and body weight among baseline, 3 months and 6 months, according to linear mixed models (Figure S2), but there were no changes in systolic or diastolic blood pressure between baseline and 6 months (Figure S3). However, there were significant changes in TC (mean change: − 8.3 mg/dl, p = 0.001) and LDL-C (mean change: − 9.7 mg/dl, p < 0.001) after 6 months of treatment (Table S3).

Predictors of the Response to Dulaglutide

To determine which variables might predict a superior response to dulaglutide, univariate and multiple linear regression analysis of the change in HbA1c was conducted. Univariate regression analysis showed that higher baseline HbA1c, FPG and C-peptide values were associated with greater reductions in HbA1c (Table 2). After adjusting for multiple confounding factors (sex, age, C-peptide, baseline HbA1c, duration of diabetes and body weight), baseline HbA1c and C-peptide levels were shown to affect the degree of reduction in HbA1c achieved. Poorer baseline glycemic status had the strongest association with the reduction in HbA1c, with a 1% higher baseline HbA1c being associated with a reduction in HbA1c of − 0.45% (Table 3). However, age, sex, duration of diabetes and baseline BMI did not affect the degree of reduction in HbA1c.

Table 2.

Univariate linear regression analysis of the reduction in HbA1c

| Variables | Standardized β | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.303 | 0.113 |

| Age | − 0.011 | 0.207 |

| Hypertension | 0.151 | 0.479 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.205 | 0.716 |

| C-peptide | − 0.286 | 0.003 |

| Baseline HbA1c | − 0.457 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FPG | − 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| GFR | 0.005 | 0.282 |

| Body weight | − 0.012 | 0.071 |

| Dulaglutide dose | − 0.243 | 0.288 |

| Duration of diabetes | 0.019 | 0.148 |

| Baseline BMI | − 0.037 | 0.101 |

FPG fasting plasma glucose, GFR glomerular filtration rate, BMI body mass index

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the reduction in HbA1c

| Variables | Standardized β | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.053 | 0.453 |

| Age | − 0.096 | 0.176 |

| C-peptide | − 0.195 | 0.024 |

| Baseline HbA1c | − 0.454 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes duration | 0.122 | 0.083 |

| Body weight | 0.016 | 0.828 |

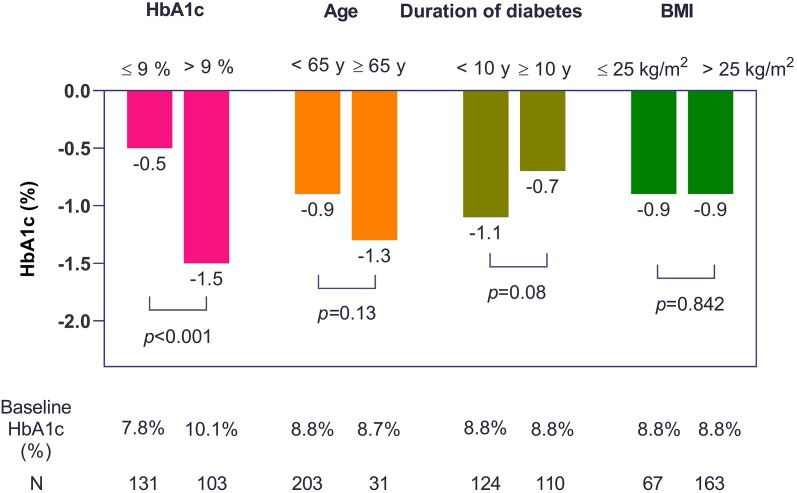

Comparison of the Efficacy of Dulaglutide in Subgroups of Patients

Patients were categorized into the following groups (Fig. 2): (1) baseline HbA1c > 9% (n = 103) or ≤ 9% (n = 131), (2) age ≥ 65 years (n = 31) or < 65 years (n = 203), (3) duration of diabetes ≥ 10 years (n = 110) or < 10 years (n = 124) and (4) BMI ≤ 25 (n = 67) or > 25 (n = 163).

Fig. 2.

Changes in HbA1c according to baseline HbA1c, age, duration of diabetes and body mass index after 6 months of treatment (Student's t-test was used to analyze the data)

After 6 months of treatment, a greater reduction in HbA1c was observed in the subgroup with baseline HbA1c > 9% (mean change: − 1.5%, 95% CI: − 1.81 to − 1.19; vs. mean change: − 0.5%, 95% CI: − 0.68 to − 0.27 for the subgroup with HbA1c ≤ 9%; p < 0.001).

The reductions in HbA1c were statistically not different for the groups classified according to age (p = 0.13) or BMI (p = 0.84).

The groups with long- and short-term histories of diabetes showed − 0.7% (95% CI: − 1.00 to − 0.50) and − 1.1% (95% CI: − 1.36 to − 0.80) reductions in HbA1c, but the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

Adverse Events

The adverse events encountered are summarized in Table 4. Overall, 41.2% of patients reported adverse events after a month of treatment. In the first month, the most frequent adverse events were gastrointestinal: nausea (26.4%) and diarrhea (5.8%). However, the overall frequency of adverse events decreased with time (19% after 3 months of treatment, 10.7% after 6 months of treatment). After 6 months, the most frequent adverse events were the same [nausea (2.9%), diarrhea (1.7%)], but they had significantly reduced in frequency. By contrast, only 1.3% (n = 3) of patients reported injection site reactions after 3 months of treatment, but 2.5% (n = 6) of patients reported these after 6 months, making them the second most common adverse event. One patient reported hypoglycemia after 3 months and one after 6 months, but there were no cases of severe hypoglycemia.

Table 4.

Adverse events

| Adverse events | 1 months (n = 102) | 3 months (n = 221) |

6 months (n = 234) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (%) | 42 (41.2) | 42 (19.0) | 25 (10.7) |

| Nausea | 27 (26.4) | 14 (6.3) | 7 (2.9) |

| Vomiting | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal distension/pain | 4 (3.9) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (5.8) | 8 (3.6) | 4 (1.7) |

| Constipation | 3 (2.9) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site reaction | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.5) |

| Allergic reaction | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) |

| Hypoglycemia | 0 (0) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) |

| Others | 2 (1.9) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) |

Data are n (%)

Discussion

In the present study, we determined the efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes in a real-world setting. Dulaglutide was effective in reducing HbA1c and was also associated with a reduction in body weight and a low risk of hypoglycemia. Dulaglutide treatment for 6 months was associated with a significant improvement in HbA1c, irrespective of age, duration of diabetes or baseline HbA1c concentration. However, greater HbA1c reductions were achieved in patients with higher baseline HbA1c concentrations.

The mean changes in HbA1c, FPG and body weight between baseline and 6 months were − 0.92%, − 19.7 mg/dl and − 2.1 kg, respectively, which were consistent with the outcomes of the clinical trials of dulaglutide [9–12, 19]. AWARD-2 compared the efficacy of dulaglutide and insulin glargine in patients already taking metformin and glimepiride, which was similar to the present study, because 91% of the patients were already taking metformin and a sulfonylurea when dulaglutide treatment was instigated. In the AWARD-2 trial, the mean HbA1c changes between baseline and 52 weeks were − 1.08% and − 0.76% for dulaglutide 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg, respectively, and those for FPG and body weight were − 27 mg/dl and − 16 mg/dl, and − 1.87 kg and − 1.33 kg, respectively. In the present study, 30.4% of patients achieved the HbA1c target of < 7% and 19.9% of patients achieved the target of ≤ 6.5%. In AWARD-2, a greater percentage of patients on dulaglutide 1.5 mg (53.2%) than on dulaglutide 0.75 mg (37.1%) achieved the HbA1c target of < 7%. However, in the present study, the baseline HbA1c of the patients was higher (8.8%) than in the AWARD-2 trial (8.1%). Thus, the percentage of patients achieving the target may have been smaller in the present study because of their higher baseline HbA1c concentrations.

Only a few previous studies have investigated the efficacy of dulaglutide in real-world settings, but their findings were similar to ours. In a study conducted in the US, the baseline HbA1c was 8.3% and there was a 1.12% reduction in HbA1c over a mean 5 months of treatment, with 40% of patients achieving an HbA1c < 7% [20]. Similarly, in a study of 30 patients conducted in India, the mean change in HbA1c over 6 months of treatment was − 1.01%, and 30% of the patients achieved an HbA1c of < 7% (baseline HbA1c, 8.43%) [21].

The adverse events associated with dulaglutide reported in this study were consistent with those previously reported for dulaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists [22]. The most frequently reported adverse events were gastrointestinal (nausea and diarrhea), but these decreased in frequency with time and were tolerable. In the present study, only two cases of hypoglycemia were reported. An optimal balance between the anti-hyperglycemic effects of the drug and the risk of hypoglycemia is of critical importance when considering options for the use of injectable therapies. The high efficacy, combined with the low risk of hypoglycemia, has contributed to GLP-1 receptor agonists becoming the favored option for patients requiring therapy in addition to oral agents.

In this study, baseline HbA1c was the most reliable clinical parameter for predicting the patients’ response to medication, and this finding is consistent with those of previous studies of dulaglutide [17, 23, 24] and other GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, albiglutide and liraglutide [25–27]. However, we have also shown a relationship between C-peptide concentration and the degree of reduction in HbA1c, suggesting that a less marked glycemic response could be expected in patients with low C-peptide levels. However, recent studies that have evaluated the relationship between C-peptide and the change in HbA1c have yielded inconsistent results. Similar to the present finding, C-peptide was associated with the degree of glycemic response to a GLP‐1 receptor agonist in a previous prospective study [18], but in other studies that investigated whether baseline pancreatic β-cell function would predict the reduction in HbA1c, C-peptide was not found to be associated with this change [16, 28]. Furthermore, dulaglutide [29] has also been shown to significantly reduce HbA1c irrespective of baseline β-cell function, assessed using the homeostatic model assessment for beta‐cell function, HOMA2-β%. Thus, further studies are needed to determine whether baseline β-cell function and/or C-peptide levels are associated with the glycemic response to GLP-1 agonists in patients with T2D.

In the present study, there was no influence of other baseline factors, including sex, age, duration of diabetes, body weight and BMI, on the change in HbA1c. One previous study showed that age < 65 years was associated with a superior reduction in HbA1c, although the effect was very small [15], but a number of other studies have shown that age [17, 23, 24, 29], sex [14, 23], duration of diabetes [23, 24] and BMI [17] do not affect the degree of reduction in HbA1c achieved.

There were several limitations to the present study. First, it was of relatively short duration (6 months). However, in a previous study, the efficacy of dulaglutide peaked after 24 weeks of treatment and was similar after 72 weeks. Thus, although longer studies might provide additional insight into other effects of dulaglutide treatment, our study duration should have been sufficient to evaluate the efficacy of dulaglutide with respect to HbA1c. Second, the prior anti-diabetic medications before starting dulaglutide were not the same among the patients; this diversity of previous medications might affect the results of efficacy of dulaglutide. However, 91% of subjects used a combination of metformin and sulfonylurea at the time of initiating dulaglutide. Third, adverse events were reported on paper, meaning that some events may have been missed. Lastly, the patients in this study were all Korean; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusion

Once-weekly dulaglutide treatment has a significant additive anti-hyperglycemic effect, induces weight loss and is associated with few significant adverse events when used in a real-world clinical setting. Furthermore, patients with higher baseline HbA1c concentrations are likely to demonstrate superior clinical responses to once-weekly dulaglutide therapy.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The article processing charges were funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Author Contributions

WJL conceived this study. JHY and WJL contributed to the design of the study. JHY, YMK, YKC, JL, HWK and CHJ conducted data collection. JHY conducted the analysis. J-YP, CHJ, JHY and WJL interpreted the results. JHY wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, with revisions by all authors. The final manuscript was approved by all authors. JHY and WJL are the guarantors of this work.

Disclosures

Jee Hee Yoo, Yun Kyung Cho, Jiwoo Lee, Hwi Seung Kim, Yu Mi Kang, Chang Hee Jung, Joong-Yeol Park and Woo Je Lee have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

In accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Korea Good Clinical Practice, this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center (2018-1050).

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8277179.

References

- 1.Umpierrez GE, Blevins T, Rosenstock J, Cheng C, Anderson JH, Bastyr EJ, 3rd Group EGOS The effects of LY2189265, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the EGO study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:418–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunberger G, Chang A, Garcia Soria G, Botros FT, Bsharat R, Milicevic Z. Monotherapy with the once-weekly GLP-1 analogue dulaglutide for 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes: dose-dependent effects on glycaemic control in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Med. 2012;29:1260–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association 9 pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S90–S102. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Won JC, Lee JH, Kim JH, Kang ES, Won KC, Kim DJ, Lee MK. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea, 2016: an appraisal of current status. Diabetes Metab J. 2018;42:415–424. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipscombe L, Booth G, Butalia S, Dasgupta K, Eurich DT, Goldenberg R, Khan N, MacCallum L, Shah BR, Simpson S, Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert C Pharmacologic glycemic management of type 2 diabetes in adults. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):S88–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2018;2018(41):2669–2701. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu JM. The role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes in Asia. Adv Ther. 2019;36:798–805. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00914-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T, Gonzalez JG, Atisso C, Sealls W, Fahrbach JL. Once-weekly dulaglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-6): a randomised, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60976-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dungan KM, Weitgasser R, Perez Manghi F, Pintilei E, Fahrbach JL, Jiang HH, Shell J, Robertson KE. A 24-week study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide added on to glimepiride in type 2 diabetes (AWARD-8) Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:475–482. doi: 10.1111/dom.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun JH, Zimmermann AG, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin and glimepiride (AWARD-2) Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2241–2249. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue H, Tamaki Y, Kashihara Y, Muraki S, Kakara M, Hirota T, Ieiri I. Efficacy of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 analogues, and SGLT2 inhibitors as add-ons to metformin monotherapy in T2DM patients: a model-based meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:393–402. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kugler AJ, Thiman ML. Efficacy and safety profile of once-weekly dulaglutide in type 2 diabetes: a report on the emerging new data. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;11:187–197. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S134960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi LX, Liu XM, Shi YQ, Li QM, Ma JH, Li YB, Du LY, Wang F, Chen LL. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy compared with glimepiride in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: post hoc analyses of a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study. J Diabetes Investig. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jdi.13075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onishi Y, Oura T, Matsui A, Matsuura J, Iwamoto N. Analysis of efficacy and safety of dulaglutide 0.75 mg stratified by sex in patients with type 2 diabetes in 2 randomized, controlled phase 3 studies in Japan. Endocr J. 2017;64:553–560. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wysham C, Guerci B, D’Alessio D, Jia N, Botros FT. Baseline factors associated with glycaemic response to treatment with once-weekly dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:1138–1142. doi: 10.1111/dom.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathieu C, Del Prato S, Botros FT, Thieu VT, Pavo I, Jia N, Haupt A, Karanikas CA, Garcia-Perez LE. Effect of once weekly dulaglutide by baseline beta-cell function in people with type 2 diabetes in the AWARD programme. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2023–2028. doi: 10.1111/dom.13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko S, Oura T, Matsui A, Shingaki T, Takeuchi M. Efficacy and safety of subgroup analysis stratified by baseline HbA1c in a Japanese phase 3 study of dulaglutide 0.75 mg compared with insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2017;64:1165–1172. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ17-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM, Hill AV, Hyde CJ, Knight BA, Hattersley AT. Markers of beta-cell failure predict poor glycemic response to glp-1 receptor agonist therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:250–257. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nauck M, Weinstock RS, Umpierrez GE, Guerci B, Skrivanek Z, Milicevic Z. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide versus sitagliptin after 52 weeks in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-5) Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2149–2158. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mody R, Grabner M, Yu M, Turner R, Kwan AYM, York W, Fernandez Lando L. Real-world effectiveness, adherence and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating dulaglutide treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34:995–1003. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1421146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosal S, Sinha B. Liraglutide and dulaglutide therapy in addition to SGLT-2 inhibitor and metformin treatment in Indian type 2 diabetics: a real world retrospective observational study. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;4:11. doi: 10.1186/s40842-018-0061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Zhang Y, Quan X, Yang Z, Zeng X, Ji L, Sun F, Zhan S. Efficacy and acceptability of glycemic control of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists among type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallwitz B, Dagogo-Jack S, Thieu V, Garcia-Perez LE, Pavo I, Yu M, Robertson KE, Zhang N, Giorgino F. Effect of once-weekly dulaglutide on glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and fasting blood glucose in patient subpopulations by gender, duration of diabetes and baseline HbA1c. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:409–418. doi: 10.1111/dom.13086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pantalone KM, Patel H, Yu M, Lando LF. Dulaglutide 1.5 mg as an add-on option for patients uncontrolled on insulin: subgroup analysis by age, duration of diabetes and baseline glycated haemoglobin concentration. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1461–1469. doi: 10.1111/dom.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, Lahtela JT, de Loredo L, Tornoe K, Boopalan A, Nauck MA, Group NNS Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:1056–1064. doi: 10.1111/dom.12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bain SC, Mosenzon O, Arechavaleta R, Bogdanski P, Comlekci A, Consoli A, Deerochanawong C, Dungan K, Faingold MC, Farkouh ME, Franco DR, Gram J, Guja C, Joshi P, Malek R, Merino-Torres JF, Nauck MA, Pedersen SD, Sheu WH, Silver RJ, Tack CJ, Tandon N, Jeppesen OK, Strange M, Thomsen M, Husain M. Cardiovascular safety of oral semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: rationale, design and patient baseline characteristics for the PIONEER 6 trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;21:499–508. doi: 10.1111/dom.13553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenstock J, Fonseca VA, Gross JL, Ratner RE, Ahren B, Chow FC, Yang F, Miller D, Johnson SL, Stewart MW, Leiter LA, Harmony 6 Study G Advancing basal insulin replacement in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with insulin glargine plus oral agents: a comparison of adding albiglutide, a weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist, versus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2317–2325. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamoto N, Matsui A, Kazama H, Oura T. Subgroup analysis stratified by baseline pancreatic beta-cell function in a Japanese study of dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boustani MA, Pittman I, Yu M, Thieu VT, Varnado OJ, Juneja R. Similar efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes aged ≥ 65 and < 65 years. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:820–828. doi: 10.1111/dom.12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.