Abstract

Purposes:

To examine whether (a) non-minority participants differed from racial minority participants in the understanding of biospecimens collected for research purposes, (b) patients differed from comparison-group in their understanding of the ways their biospecimens could be used by researchers, and (c) participants received adequate information before consenting to donate blood for research studies.

Methods:

We analyzed cross-sectional data from female breast cancer patients scheduled to receive chemotherapy at National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) clinical sites and a healthy comparison group. After reading a consent form related to biospecimens and consenting to participate in a clinical trial, participants’ understanding of biospecimen collection was evaluated. Linear models were used to compare scores between non-minority and racial minority participants as well as cancer and non-cancer comparisons adjusting for possible confounding factors.

Results:

A total of 650 participants provided evaluable data; 592 were non-minority (Caucasian) and 58 participants were racial minority (71% black and 29% other). There were 427 cancer patients and 223 comparisons. Non-minority participants scored higher than racial minorities on relevance-to-care items (diff.=0.48, CI: 0.13 – 0.80, p=0.001). Comparison group scored higher than cancer patients on relevance-to-care items (diff.=0.58, CI: 0.37–0.78).

Conclusion:

A moderate number of the participants exhibited poor understanding of biospecimen collection across all racial/ethnic backgrounds, but racial minority participants’ scores remained lower in the relevance-to-care subscale even after adjusting for education and reading level. Differences were also noted among the patients and comparison group. Researchers should facilitate comprehension of biospecimen collection for all study participants, especially racial minority participants.

Keywords: race, disparities, biospecimens, consent, consent form

Introduction

Over the past two decades, collection of biological samples has become routine in cancer research and clinical trials. Biological samples such as tissue, blood, and other bodily fluids contain cellular and molecular information that is important for scientific and medical advances and critical for the development of personalized medicine [1-5]. Biological samples have played an important role in medical exploration of cancer development, mutation, and metastatic pathways, as well as possible therapeutic mechanisms and symptom management [2].

Even though biological samples have played an important role in research in the areas of precision medicine, drug development, and symptom management, medically underserved populations and racial and ethnic minorities are inadequately represented in those efforts [6, 7]. It is imperative to seek equitable representation of minority and underserved populations in biospecimen collection, especially in the current era of precision (or data driven) cancer therapy and research; many of these innovative therapies are linked to genomic variations that are more or less prevalent in certain minority and/or underrepresented populations [8]. Thus, representation of minorities in research biobanking is more important than ever to advance progress in cancer care for minority and underrepresented populations [8]. In addition, fair representation of minority and underserved populations in biological samples collection will present an opportunity for researchers to compare genetic variability across diverse populations, evaluate genetic predispositions and risk factors, and determine susceptibility for different racial and ethnic groups [2, 9, 10]. In addition, equitable representation of populations with diverse backgrounds would enhance generalizability of study findings [11, 12].

Patients in general, and minority and underserved patients in particular, may be willing to participate in research studies that involve biological sample collections if they adequately understand the purpose of those studies [13-15]. Indeed, Drake et al. [13] examined African American men’s barriers to participating in biorepository research and found that the majority of the participants was willing to participate in biospecimen collection and storage research if they understood that their participation could benefit future generations. Another study by Warmer et al. [16] reported that research participants had very positive views regarding tissue donation in general and they endorsed the use of their biospecimens in future research across a wide range of contexts.

Previous studies have identified important barriers to biospecimen donation including lack of awareness about biospecimen donation [15, 17] and lack of knowledge about what is done with biospecimens [6, 13, 15]. A few studies have suggested that racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations are largely underrepresented in cancer research for treatment and symptom management. In general, due to linguistic barriers that automatically exclude potential participants [18, 19], low literacy that leads to difficulties in understanding informed consent documents [19], and failure to understand the process of random assignment and the meaning of standard treatment [20]. Other barriers include concerns about possible tests, discomfort, increased costs, insurance problems, and problems with transportation [20].

While addressing these barriers is beyond the scope of this study, an opportunity exists to objectively evaluate research participants’ comprehension about biospecimen collection, storage, and sharing. Securing patients understanding about biospecimen collection [13, 15] and providing adequate and specific information that biospecimen collection will not only promote participants’ trust in the research but will also enhance their participation in biospecimen collection research [13, 15].

In this study, we specifically aimed to objectively evaluate research participants’ comprehension about biospecimen collection, storage, and sharing. This is important, especially for racial and ethnic minorities who are hesitant to participate in research because of mistrust [11, 15, 21-23]. To our knowledge, research objectively assessing participants’ understanding of biological sample collections, their storage, and their current and future use is limited. The purposes of the current study are to examine: (a) whether non-minority (white) and racial minority (black and other) participants differed in comprehension of biological sample collections (defined as the participants’ ability to recollect biospecimen information from the informed consent document and correctly select an answer for each question that was consistent with the information on the consent form), (b) whether breast cancer patients and non-cancer comparison participants differed in their understanding about biospecimen collection, and (c) whether participants received adequate information before consenting to donate blood for a research study.

Methods

Design and participants

As part of a nationwide NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) observational study that included newly diagnosed female patients with breast cancer (stage I-IIIC) and age-paired female participants without cancer [24], we conducted a cross-sectional survey administered at baseline that assessed understanding of biospecimen information provided as part of informed consent. Only participants who could read and speak English, and were 21 years or older, were included in the study.

Consent procedure

All participants completed the same informed consent document and consenting of both participants with and without cancer occurred by the same study personnel of the participating NCORP site. The study utilized a broad informed consent approach [16, 25] All participants provided face-to-face, documented informed consent before completing study requirements. Information about biospecimen collections, their storage, and their future usage were detailed in the informed consent document. The participants were given ample time to read the consent form at their own pace, opportunities to ask questions and follow-up questions for clarification, and the opportunity to thoroughly review the consent form for several days prior to making a decision about participating. Within two weeks after consenting to participate, and prior to starting their chemotherapy regimen, they were asked to complete a biological specimen survey during the baseline visit. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the URCC NCORP Research Base and each participating NCORP recruitment site approved the study before participants enrolled.

Measures

Biospecimen Questionaire

An 18-item questionnaire was developed to assess understanding of information based on biospecimen information provided in the informed consent document (Table 2). The survey was used to assess participants’ comprehension, and it consisted of three categories (subscales; a-c). (a) The specimen use and handling subscale addressed issues such as the types of biospecimens collected, whether those biospecimens were going be used or stored, etc. Nine items were used to measure specimen use and handling, and the participant was awarded one point for each correct response; possible scores ranged from 0-9, where a score of 0-6 indicated poor comprehension and a score of 7-9 indicated good comprehension. (b)The biospecimen sharing subscale included items such as who can use the biospecimens collected. Four items were used to measure specimen sharing, and the possible scores ranged from 0-4 where a score of 0-2 indicated poor comprehension and a score of 3-4 indicated good comprehension. (c) The relevance-to-care subscale focused on whether the biospecimens collected would be used for the participants’ medical care. Three items were used to measure biospecimen relevance-to-care, and the possible scores ranged from 0-3, where a score of 0-1 indicated poor comprehension and a score of 2-3 indicated good comprehension.

Table 2.

Percentage correct for items assessing knowledge of informed consent (n=650)

| Non- minority Subjects (n=592) |

Minority Subjects (n=58) |

Cancer Patients (n=427) |

Non-cancer group (n=223) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Specimen use/handling a | ||||||||

| 1. Type of human biological sample provided? | 542 | 92 | 52 | 90 | 427 | 87 | 223 | 98 |

| 2. Use specimens in the current study? | 552 | 93 | 54 | 93 | 427 | 91 | 223 | 97 |

| 3. Use specimens in future research? | 535 | 90 | 50 | 86 | 427 | 90 | 223 | 90 |

| 4. Use specimens donated indefinitely? | 498 | 84 | 44 | 76 | 427 | 83 | 223 | 84 |

| 5. Use specimens for any research? | 546 | 92 | 51 | 88 | 427 | 92 | 223 | 92 |

| 6. Use specimens for future research without further permission? | 502 | 85 | 46 | 79 | 427 | 84 | 223 | 84 |

| 7. Use specimens for future research provided it is approved? | 453 | 77 | 44 | 76 | 427 | 76 | 223 | 78 |

| 8. Can you request the specimens be removed and destroyed? | 473 | 80 | 45 | 78 | 427 | 79 | 223 | 80 |

| 9. Examine any genetic information in specimens? | 455 | 77 | 42 | 72 | 427 | 75 | 223 | 80 |

| Scored all 9 specimen use questions correctly | 278 | 47 | 23 | 40 | 186 | 44 | 115 | 52 |

| Scored 0-6 (Low score) | 111 | 19 | 11 | 19 | 84 | 20 | 38 | 17 |

| Specimen sharing a | ||||||||

| 10. Share specimens with URCC researchers? | 507 | 86 | 44 | 76 | 427 | 84 | 223 | 86 |

| 11. Share specimens with other Universities’ researchers? | 403 | 68 | 40 | 69 | 427 | 68 | 223 | 68 |

| 12. Share specimens with private companies’ researchers? | 253 | 43 | 31 | 53 | 427 | 45 | 223 | 42 |

| 13. Share specimens with other researchers outside the U.S.? | 234 | 40 | 18 | 31 | 427 | 39 | 223 | 39 |

| Scored all 4 specimen sharing questions correctly | 204 | 34 | 18 | 31 | 145 | 34 | 77 | 35 |

| Scored 0-2 (Low score) | 313 | 53 | 27 | 47 | 218 | 51 | 122 | 55 |

| Relevance-to-care b | ||||||||

| 14. Specimens be used for your medical care? | 387 | 65 | 25 | 43 | 427 | 53 | 223 | 83 |

| 15. Specimens can affect your medical care? | 308 | 52 | 18 | 31 | 427 | 42 | 223 | 66 |

| 16. Specimens will directly benefit you? | 319 | 54 | 19 | 33 | 427 | 48 | 223 | 61 |

| Scored all 3 specimen relevance questions correctly | 238 | 40 | 11 | 19 | 296 | 69 | 105 | 47 |

| Scored 0-1 (Low score) | 253 | 43 | 36 | 62 | 224 | 53 | 65 | 29 |

| Adequate information | ||||||||

| 17. Amount of information about biological sample for the CURRENT research project was adequate? | 544 | 92 | 51 | 88 | 427 | 90 | 223 | 95 |

| 18. Amount of information about biological sample for the FUTURE research project was adequate? | 506 | 86 | 52 | 90 | 427 | 84 | 223 | 90 |

The response options were yes/no/unsure. Consistent with informed consent document information, the correct answer for each item was “Yes.”

The response options were yes/no/unsure. Consistent with informed consent document information, the correct answer for each item was “No.”

Two additional items were used to determine whether participants received adequate information about biospecimen collection before donating biological samples.

Other Covariates

The reading ability of the participants was assessed using the Wide Range Assessment Test-4th Edition (WRAT-4) reading subscale [24]. Functional Assessment of Cancer-Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog) was used to measure the cognitive function of the participants [24, 26]. Age and clinical information was obtained from the medical record and participants reported their education and marital status.

Analyses

Two analyses were performed. The first (main) analysis used 2 linear regression models to compare the difference in mean scores of the biospecimen survey (outcome variables) between the non-minority and racial minority participants (covariate) and also between cancer patients and the comparison group without cancer. Each of the three outcome variables (handling/use, sharing, and relevance-to-care) were modelled, and the relationship for each was examined separately. We adjusted for age, reading comprehension (WRAT), cognitive function, marital status, clinical conditions (cancer patients vs. comparison group), and education. A secondary analysis was based on 1:1 distance-matching where the racial minority participants were matched against the non-minority participants based on the similarity of their demographic variables such as educational background, reading level, cognitive function, cancer diagnosis status (cancer patients and comparison), and age. These distance-matching analyses were conducted to account for an imbalance in sample size between non-minority and racial minority populations as well as for potential biases that might arise from unmatched analyses. The results from both analyses were compared. Computations were performed using SAS (v.9.4), and SPSS (v.24).

Results

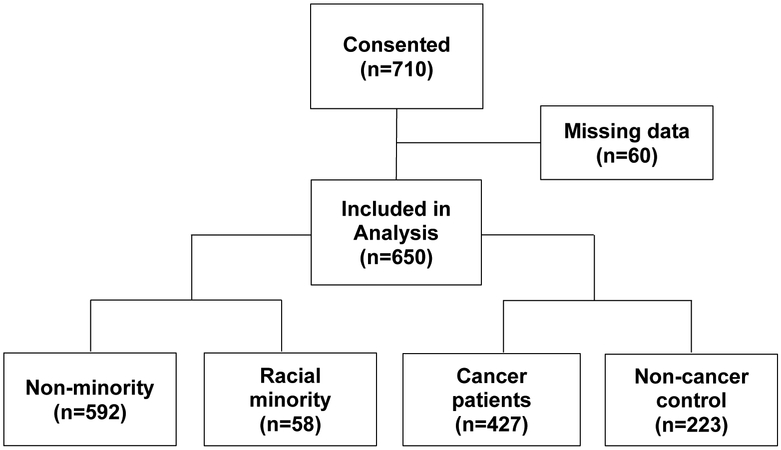

Of the total 710 participants enrolled, 650 participants provided evaluable data on the biospecimens survey (Figure 1). Sixty participants who did not provide answers to any of the biospecimen questions (outcome variables) were excluded from further analysis. The excluded participants were approximately equally distributed across races and patient and comparison groups. The 650 participants included in the analysis consisted of 427 breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and 223 non-cancer comparisons. There were 592 non-racial minorities (Caucasians) and 58 racial minorities (n=47 black and n= 11 other). For each of the 58 racial minority participants, distance-matching analyses identified a non-minority participant with the closest demographic characteristics. The results for the linear modeling analyses for the matched sub-cohort (n=58 non-minority and n=58 racial minority) were similar to the results for the main analyses for 592 non-racial minorities and 58 racial minorities (See Table 3 for the distance-matching results). We report the results for all participants. Non-racial minorities were more likely than racial minority participants to be married (p<0.05), had a higher reading level (p<0.001), and had a higher cognitive function (p<0.001). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Figure 1.

Participant flow

Table 3.

Mean correct items assessing knowledge of informed consent information by area of knowledge and by majority vs. minority racial groups.

| Main Analysis | Non-minority | Racial minority | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Difference in means |

95% CI | |

| All questionsc | 592 | 11.01 | 3.19 | 58 | 10.38 | 3.32 | 0.63 | −0.52–1.78 |

| Specimen handlingc | 592 | 7.69 | 1.84 | 58 | 7.42 | 2.10 | 0.28 | −0.24–0.81 |

| Specimen sharingc | 592 | 2.37 | 1.45 | 58 | 2.22 | 1.57 | 0.20 | −0.21–0.61 |

| Relevance-to-carec | 592 | 1.70 | 1.24 | 58 | 1.19 | 1.21 | 0.48 | 0.13–0.80a |

|

| ||||||||

| Matched Analysis | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Specimen handlingc | 58 | 7.31 | 0.27 | 58 | 7.38 | 0.27 | −0.07 | −0.83–0.69 |

| Specimen sharingc | 58 | 2.45 | 0.20 | 58 | 2.31 | 0.20 | 0.15 | −0.42–0.72 |

| Relevance-to-carec | 58 | 1.58 | 0.16 | 58 | 1.09 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.02–0.94b |

Significant at p<0.001, adjusted for age, education, clinical condition, marital status, reading level, and baseline cognitive function.

Significant at p<0.05, adjusted for age, education, clinical condition, marital status, reading level, and baseline cognitive function.

Score ranges are: all questions 0-16; specimen use between 0-9; specimen sharing between 0-4; and relevance 0-3, where a higher number indicates higher score.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics and clinical conditions for non-minority and racial minority subjects

| Non-minority participants (n=592) | Racial minority participants (n=58) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Variables | n | Percent | n | Percent |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 419 | 64% | 24 | 4%a |

| Not married | 173 | 27% | 34 | 5% |

| Education | ||||

| No college degree | 496 | 76% | 45 | 7% |

| College degree | 96 | 15% | 13 | 2% |

| Clinical condition | ||||

| Control group | 208 | 32% | 15 | 2% |

| Cancer patients | 384 | 59% | 43 | 7% |

| n | Mean | STD | Range | n | Mean | STD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading level | 592 | 63 | 5 | 40-70 | 58 | 60 | 9 | 29-70a |

| Age | 592 | 53 | 11 | 22-81 | 58 | 51 | 10 | 33-70 |

| Cognitive function | 591 | 164 | 25 | 62-200 | 57 | 152 | 27 | 85-199b |

Significant at p<0.001

Significant at p<0.05

The non-racial minorities’ scores ranged from 34% to 93%, and those of racial minorities ranged from 31% to 93%. However, more than half of non-minority participants (53%) and almost half of racial minority participants (47%) scored 0-2 out of 4 on biospecimen sharing questions. Similarly, the majority of racial minority participants (62%) and a moderate number of non-minority participants (43%) scored 0-1 out of 3 on the biospecimen relevance-to-care questions. These results showed that a moderate number of participants had poor understanding of the questions. Table 2 shows the proportion of correct scores for individual items, the overall correct scores, and the below means scores for each subscale by race.

Non-minority and racial minority participants

After adjusting for covariates, the linear regression model showed that the non-minority participants’ scores for all the questions combined were not significantly different from racial minority participants’ scores (adjusted mean scores 11.01 vs. 10.38 out of 16; p=0.28). There was no significant difference between non-racial minorities’ and racial minorities’ scores in comprehension of biospecimen handling (adjusted mean score 7.69 vs. 7.41 out of 9; p=0.29) and biospecimen sharing (adjusted mean score 2.37 vs. 2.17 out of 4; p=0.34). However, non-racial minorities demonstrated better understanding than racial minorities about biospecimen relevance-to-care for patients (adjusted mean score 1.70 vs. 1.19 out of 3; diff=0.48, CI: 0.13 – 0.80, p=0.001). See Table 3.

Both racial minority participants and non-minority participants reported that they received adequate information prior to donating biological samples for the current research project (racial minorities 87.9% vs non-racial minorities 91.9%, p=0.30) and future research projects (racial minorities 89.7% vs non-racial minorities 85.5%, p=0.38) (Table 2).

Cancer patients and comparison group

After adjusting for covariates, the non-cancer comparison group score for all questions combined was not significantly different from the cancer patients’ score (adjusted mean scores Comparison 11.04 vs. patients 10.91 out of 16; p=0.70). There also was no significant difference between the comparison group score and the cancer patients’ score on specimen use and handling (adjusted mean score: comparison 7.82 vs. patients 7.58 out of 9; p=0.12) and on specimen sharing (adjusted mean score: comparison 2.36 vs. patients 2.35 out of 4; p=0.89). The comparison group demonstrated better understanding of the relevance-to-care items than the cancer patients (adjusted mean score: comparison 2.04 vs. patients 1.46 out of 3; diff.=0.58, CI 0.37-0.78, p<0.001). See Table 4.

Table 4.

Adjusted mean scores of the patient and control groups (all races) on specimen use, specimen sharing, and relevance-to-care (n=650)

| Variables | Patient (n=427) | Non-cancer group (n=223) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | Difference in means |

95% CI |

| All questions | 10.91 | 3.25 | 11.04 | 3.07 | 0.13 | −0.55 – 0.81 |

| Specimen handlingb | 7.58 | 1.94 | 7.82 | 1.70 | 0.24 | −0.07 – 0.55 |

| Specimen sharingb | 2.35 | 1.46 | 2.36 | 1.45 | 0.01 | −0.23 – 0.26 |

| Relevance-to-careb | 1.46 | 1.25 | 2.04 | 1.12 | 0.58 | 0.37 – 0.78a |

Significant at p<0.01 adjusted for age, education, race, marital status, cognitive function, and reading level.

Score ranges are: all questions 0-16; specimen use between 0-9; specimen sharing between 0-4; and relevance 0-3, where a higher number indicates a higher score.

On adequate information questions, the non-cancer comparison group was more likely than cancer patients to report that they received adequate information prior to donating biological samples for the current research project (comparison group 95% vs. cancer patients 90%, p=0.04) and future research projects (comparison group 90% vs. patients 84%; p=0.04) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study evaluated participants’ understanding of biospecimen collection for present and future use as described in an informed consent document for an observational nationwide study conducted through the URCC NCORP Research Base and affiliate NCORP sites. The first major finding of the study was that there was a significant difference between non-minority participants’ and racial minority participants’ understanding of biospecimen collection, and these differences were apparent when assessed using the relevance-to-care subscale. Indeed, non-racial minority and racial minority participants reported that they received adequate information about biospecimen collection and banking before consenting to the study, similar to another study [27]; however, herein, participants’ responses for biospecimen collection and storage showed that information did not lead to full comprehension. Racial minority participants had lower scores than non-minority participants on biospecimen relevance-to-care subscale, even after adjusting for educational background and reading levels, demonstrating that the racial minority participants had a harder time understanding the biospecimen information in the informed consent document. This finding is consistent with the study of Dang et al. that showed that study participants demonstrated low knowledge and understanding of biospecimen research [28]. Our results also support other findings that the complex nature of the informed consent document makes it difficult for study participants, especially the minority population, to understand all aspects of clinical research [19, 29]. Racial minorities’ low understanding could be explained in terms of the their health literacy level or general literacy level [30]. General literacy is the ability to read or write, and health literacy is the ability to understand medical jargon or complex instructions in a health environment including health research instructions [30]. Unfortunately, minority populations are more likely than non-minority populations to have lower general and health literacy levels [31]. In the current study, the models were adjusted to account for reading and education levels, so general illiteracy could not explain their difficulty to understand the informed consent document. Therefore, it is likely that health illiteracy combined with the complex nature of the biospecimen information may explain the participants’ low understanding of the biospecimen relevance-to-care; this hypothesis is supported by Schyve’s study [30], which concluded that due to low health literacy most participants find it difficult to understand complex instructions in a health environment. Because informed consent documents are, in most cases, written in complex scientific jargon that research participants find difficult to understand or decline to read at all, studies have suggested that using a “teach-back” approach may be useful for administering informed consent documents especially among low health literate and racial minority populations [32-35]. The teach-back approach posits that a researcher can ask a participant to read the informed consent, or the researcher could read the documents and ask the participants to teach-back or explain what the informed consent documents mean to him/her. The racial minority participants’ lower scores on relevance-to-care could be because of lack of belief in the health care system, historical experience related to biospecimen collections or research related experience that might have affected their perceptions biospecimen relevance-to-care. Further study needs to be conducted to evaluate whether historical experience accounted for minorities low scores.

Another interesting observation in the study was that the biospecimen information on the informed consent document clearly stated that the biospecimens collected would not be used to inform treatment for the participants’ current medical conditions. However, patients, especially the racial minority participants, were likely to believe that the biospecimens collected could be used to take care of their present medical ailment(s). This may mean that the cancer patientswere thinking about treatment, and therefore when they donate the biospecimens they might expect that the blood samples would be used for their current medical condition. This assertion is consistent with the literature, in which minority participants that do decide to participate in research tend to be eager to experience the benefit of participating in research and also believe that their participation in a study will help them improve their health conditions [36]. Other studies, however, have concluded that minorities are willing to participate in research for altruistic reasons [15, 27, 36].

Another important finding shows that approximately half of non-minority participants (53%) and racial minority participants (47%) scored poorly on biospecimen sharing questions. Similarly, the majority of racial minority participants (62%) and a moderate number of non-minority participants (43%) scored poorly on relevance-to-care questions. These results indicate that participants, both non-minorities and racial minorities, had a hard time understanding who could have access to the biospecimens, for what purpose those biospecimens would be used, and whether the biospecimens would be used to treat their current health conditions or not. This result could be because they did not actually read the consent form in detail; perhaps they were unconcerned about biospecimen collection for present or future research; or maybe they simply trusted the judgment of the researchers. This proposition is supported by other studies indicating that research participants rarely fully read information in informed consent documents [37-39]. Failure of study participants to read the informed consent material in its entirety, related to biospecimen collection before consenting to the study presents an ethical conundrum for researchers, IRBs, and participants involved in research. Modern informed consent documents require, among other things, patients’ comprehension of information provided to them [19] to make an informed decision about research studies [40, 41]. However, if they do not fully read the informed consent document, then the original purpose of it—to protect human research participants [42]—is defeated. In this case, informed consent documents would become legal documents to protect researchers, as some minority participants have alleged [43].

Another major finding was the significant difference between cancer patients’ and the non-cancer comparison group’s understanding of biospecimen relevance-to-care (Table 4). The non-cancer comparison group was less likely to believe that the biospecimens collected would be used for any medical care or treatment, while cancer patients were more likely to believe the opposite because they may be thinking more about their immediate care [44]. This finding is suggesting that because non-cancer group did not have any current medical conditions, they thought biospecimen collection would not be used for anything related to medical care. The cancer patients on the other hand, might be optimistic that sample collection would be used for treatment. This means participants’ current medical conditions and perception about biospecimen collection might have influenced their responses instead of responding to the questions based on what they read from the informed consent. A qualitative study could be conducted to better understand why cancer patients demonstrated poor understanding about biospecimen relevance-to-care.

Lastly, the non-cancer comparison group was more likely than the cancer patients to report that they received adequate information prior to donating biological samples for research. The cancer participants appear to need more information; perhaps they were in a vulnerable state and felt more self-conscious about their samples. Also, they were probably receiving an overwhelming amount of information, and it might have been hard for them to separate their clinical responsibilities from the study responsibilities. Research studies should be conducted to explore why cancer patients need more information about biospecimen collections.

This study has several limitations. First, there were only 58 racial minority participants (9%), which made it difficult to compare their responses with those of non-minority participants; biases could have been introduced. However, the distance-matched analysis results agreed with the results of the main analyses, and thus the biases in this study are probably minimal. Further subgroup analyses were impossible because of the small sample size of the racial minority participants. Future studies should try to recruit more racial minority participants. Third, as a cross-sectional study, these results provide only a snapshot of the participants’ understanding of biospecimen collection and not how their understanding might change with time.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, to our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to objectively compare non-minority and racial minority cancer patients’ understanding about biospecimen collection. This study objectively assessed several important questions about the perceptions of cancer participants with regard to the future use of their biological samples and participants’ expectations regarding the benefits of research results to them. Another strength of the study is that it recruited a large sample of patients and non-patients from diverse oncology practices across the US, offering broad, nationwide generalizability.

Implications

The findings of this study highlight the need for biobanking education for research participants. The overall level of understanding was lower than optimal, especially in regard to relevance-of-care. Therefore, researchers should make efforts to fully educate participants, irrespective of their racial background, about biospecimen collection and purpose through simpler language on the consent form. Research participants’ comprehension of the informed consent document is important because it helps them make informed decisions about research studies. Research participants’ correct understanding of biospecimen collection will allay their misgivings about research and allow them to build trust that encourages them and others to participate in biospecimen research [13]. Securing patients understanding about biospecimen collection [13, 15] and providing adequate and specific information that biospecimen collection will not only promote participants’ trust in the research but will also enhance their participation in biospecimen collection research [13, 15]. Finally, providing adequate information and open conversations about biobanking can increase participation in biospecimen collection [15, 45].

Conclusion

While the majority of participants reported receiving adequate information about biological sample donation to a research study, participants’ overall understanding was lower than expected across all racial/ethnic backgrounds, and racial minority participants’ scores were lower than non-racial minorities even after adjusting for education and reading level. Efforts should be made by researchers to make it easier for all study participants, especially racial minority participants, to understand the purpose of biospecimens collection, storage, and sharing.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in this study and all staff at the URCC NCORP Research Base and our NCORP affiliate sites who recruited and followed participants. We thank the NCI CCOP and NCORP Programs for their funding and support of this project. The following CCOP/NCORPs participated in this study: Central Illinois, Columbus, CRCWM, Dayton, Delaware, Grand Rapids, Greenville, HOACNY, Kalamazoo, Kansas City, Marshfield, Metro Minnesota, Nevada, North Shore, PCRC SCCC, SCOR, Upstate Carolina, Virginia Mason, Wichita, WiNCORP, and WORC. We also thank Dr. Susan Rosenthal for her critical review of this manuscript.

Funding/Support: Funding was provided by NCI U10CA037420 Supplement, NCI UG1CA189961, NCI K07CA1688, and NCI R25CA102618.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed Supportive Care in Cancer Author Disclosure Declaration. There are no disclosures to report by any of the authors.

References

- 1.De Souza YG and Greenspan JS, Biobanking past, present and future: responsibilities and benefits. Aids, 2013. 27(3): p. 303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He N, et al. , Attitudes and Perceptions of Cancer Patients Toward Biospecimen Donation for Cancer Research: A Cross-Sectional Survey Among Chinese Cancer Patients. Biopreserv Biobank, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaught J, et al. , An NCI perspective on creating sustainable biospecimen resources. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 2011. 2011(42): p. 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt RE, Biobanking: the foundation of personalized medicine. Curr Opin Oncol, 2011. 23(1): p. 112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waltz E, Tracking down tissues. Nat Biotechnol, 2007. 25(11): p. 1204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dash C, et al. , Disparities in knowledge and willingness to donate research biospecimens: a mixed-methods study in an underserved urban community. J Community Genet, 2014. 5(4): p. 329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiviniemi MT, et al. , Pilot intervention outcomes of an educational program for biospecimen research participation. J Cancer Educ, 2013. 28(1): p. 52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew SS, et al. , Inclusion of diverse populations in genomic research and health services: Genomix workshop report. Journal of Community Genetics, 2017. 8(4): p. 267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James RD, et al. , Strategies and stakeholders: minority recruitment in cancer genetics research. Community Genet, 2008. 11(4): p. 241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burchard EG, et al. , The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med, 2003. 348(12): p. 1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, and Leese B, Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community, 2004. 12(5): p. 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miranda J, Nakamura R, and Bernal G, Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long-standing problem. Cult Med Psychiatry, 2003. 27(4): p. 467–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake BF, et al. , Barriers and strategies to participation in tissue research among African-American men. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 2017. 32(1): p. 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang R, et al. , African American participation in health-related research studies: indicators for effective recruitment. J Public Health Manag Pract, 2013. 19(2): p. 110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson FP, et al. , Abstract A28: Enrolling African Americans into a cancer-related biobank. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 2015. 24(10 Supplement): p. A28–A28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner TD, et al. , Broad Consent for Research on Biospecimens: The Views of Actual Donors at Four U.S. Medical Centers. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics, 2018: p. 1556264617751204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez EM, Torres ET, and Erwin DO, Awareness and interest in biospecimen donation for cancer research: views from gatekeepers and prospective participants in the Latino community. J Community Genet, 2013. 4(4): p. 461–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen TT, Somkin CP, and Ma Y, Participation of Asian-American women in cancer chemoprevention research: physician perspectives. Cancer, 2005. 104(12 Suppl): p. 3006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knifed E, et al. , Patients’ perception of the informed consent process for neurooncology clinical trials. Neuro Oncol, 2008. 10(3): p. 348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comis RL, et al. , Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol, 2003. 21(5): p. 830–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills EJ, et al. , Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol, 2006. 7(2): p. 141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UyBico SJ, Pavel S, and Gross CP, Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med, 2007. 22(6): p. 852–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman DB, et al. , A qualitative study of recruitment barriers, motivators, and community-based strategies for increasing clinical trials participation among rural and urban populations. Am J Health Promot, 2015. 29(5): p. 332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janelsins MC, et al. , Cognitive Complaints in Survivors of Breast Cancer After Chemotherapy Compared With Age-Matched Controls: An Analysis From a Nationwide, Multicenter, Prospective Longitudinal Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2017. 35(5): p. 506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grady C, et al. , Broad Consent For Research With Biological Samples: Workshop Conclusions. The American journal of bioethics : AJOB, 2015. 15(9): p. 34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner L, et al. , Measuring Patient Self-Reported Cognitive Function: Development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Instrument. Journal of Supportive Oncology, 2009. 7: p. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pentz RD, Billot L, and Wendler D, Research on stored biological samples: views of African American and White American cancer patients. Am J Med Genet A, 2006. 140(7): p. 733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dang JH, et al. , Engaging diverse populations about biospecimen donation for cancer research. J Community Genet, 2014. 5(4): p. 313–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killien M, et al. , Involving minority and underrepresented women in clinical trials: the National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med, 2000. 9(10): p. 1061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schyve PM, Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the Joint Commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med, 2007. 22 Suppl 2: p. 360–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leah C Trahan PW, Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities; A Business Case Update for Employers Issue Brief, 2009: p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguila E, et al. , Culturally Competent Informed-Consent Process to Evaluate a Social Policy for Older Persons With Low Literacy:The Mexican Case. SAGE Open, 2016. 6(3): p. 2158244016665886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kripalani S, et al. , Clinical Research in Low-Literacy Populations: Using Teach-Back to Assess Comprehension of Informed Consent and Privacy Information. IRB: Ethics & Human Research, 2008. 30(2): p. 13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fink AS, et al. , Enhancement of surgical informed consent by addition of repeat back: a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg, 2010. 252(1): p. 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamariz L, et al. , Improving the informed consent process for research subjects with low literacy: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med, 2013. 28(1): p. 121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.George S, Duran N, and Norris K, A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Minority Research Participation Among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 2014. 104(2): p. e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olver IN, et al. , Improving informed consent to chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial of written information versus an interactive multimedia CD-ROM. Patient Educ Couns, 2009. 74(2): p. 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen ER, et al. , Do undergraduate student research participants read psychological research consent forms? Examining memory effects, condition effects, and individual differences. Ethics Behav, 2011. 21(4): p. 332–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varnhagen CK, et al. , How informed is online informed consent? Ethics Behav, 2005. 15(1): p. 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botkin JR. Informed Consent for the Collection of Biological Samples in Household Surveys. In: National Research Council (US) Committee on Population; Finch CE, Vaupel JW, Kinsella K, editors. Cells and Surveys: Should Biological Measures Be Included in Social Science Research? Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. 12. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK110047/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn SC, et al. , Improving informed consent with minority participants: results from researcher and community surveys. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics, 2012. 7(5): p. 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weindling P, The origins of informed consent: the International Scientific Commission on Medical War Crimes, and the Nuremburg code. Bull Hist Med, 2001. 75(1): p. 37–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freimuth VS, et al. , African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc Sci Med, 2001. 52(5): p. 797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olson EM, et al. , The ethical use of mandatory research biopsies. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology, 2011. 8(10): p. 620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heredia NI, et al. , Community perceptions of biobanking participation: A qualitative study among Mexican-Americans in three Texas cities. Public health genomics, 2017. 20(1): p. 46–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]