Abstract

Objectives

Women with prediabetes are identified from screening for overt diabetes in early pregnancy, but the clinical significance of prediabetes in pregnancy is unclear. We examined whether prediabetes in early pregnancy was associated with risks of adverse outcomes.

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of pregnant women enrolled in Kaiser Permanente Washington from 2011 to 2014. Early pregnancy hemoglobin A1C (A1C) values, covariates, and outcomes were ascertained from electronic medical records and state birth certificates. Women with prediabetes (A1C of 5.7–6.4%) were compared with those with normal A1C levels (<5.7%) for risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and other outcomes including preeclampsia, primary cesarean delivery, induction of labor, large/small for gestational age, preterm birth, and macrosomia. We used modified Poisson’s regression to calculate adjusted relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Of 7,020 women, 239 (3.4%) had prediabetes. GDM developed in 48% of prediabetic women compared with 11% of women with normal A1C levels (adjusted RR: 2.8, 95% CI: 2.4–3.3). Prediabetes was not associated with all other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion

Prediabetes in early pregnancy is a risk factor for GDM. Future research is needed to elucidate whether early intervention may reduce this risk.

Keywords: prediabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus, A1C, pregnancy, gestational weight gain

Type 2 diabetes has become increasingly common in younger adults including women of childbearing age,1–3 leading to a potential increase in the number of pregnant women with overt diabetes. These women need rapid treatment and close monitoring to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes.4 Thus, the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG), the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend screening for overt diabetes at the first prenatal visit in either all or high-risk women using, for instance, glycosylated hemoglobin A1C (A1C).4–6 A1C values of 6.5% or above indicate diabetes, and women with values in this range are to be treated immediately. This approach also identifies women with prediabetes (A1C of 5.7–6.4%).5 However, it is unclear whether any intervention is warranted in this group.

In nonpregnant populations, it is helpful to recognize prediabetes because it increases risk for future diabetes and cardiovascular disease.5 Providing lifestyle interventions that promote a healthy diet, weight loss, and physical activity can slow and even prevent progression to diabetes.7,8 However, it remains controversial whether these findings are relevant to pregnant women. Only a few studies have examined how often pregnant women with early-pregnancy A1C in the prediabetic range progress to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and all confirmed a higher risk: 27 to 50% of these women developed GDM compared with 9 to 14% of women with normal A1C values.9–11 It remains unclear whether prediabetes in early pregnancy carries higher risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes other than developing GDM. Two U.S. studies reported no increased risk for other pregnancy outcomes, while a New Zealand study reported higher risks for several maternal and fetal complications, including a fourfold higher risk of perinatal death.11 Several factors could explain the discrepant results. First, the New Zealand study defined prediabetes using an A1C cutoff of 5.9%, indicating more severe prediabetes. There are likely differences in practices around caring for women with GDM between the United States and New Zealand. Finally, in the prior U.S. studies, the sample sizes were smaller (prediabetes occurred in 55 out of 526 and 189 out of 2,882 women in the U.S. studies, compared with 200 out of 8,397 in the New Zealand study). Despite this uncertainty around potential risk associated with prediabetes in early pregnancy, in some settings, women with an A1C in the prediabetic range receive interventions. For example, in a state-sponsored California Diabetes in Pregnancy Program, women with prediabetes were treated as if they had been diagnosed with GDM, without further testing.12 Knowing if women with prediabetes are at higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes can shed light on whether such immediate intervention is appropriate.

Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA), an integrated health care system in the Northwest United States serving ~680,000 members, implemented universal A1C screening for pregnant women in 2011 as part of a new clinical guideline on GDM. Using a population-based sample larger than prior U.S. studies, this study aims to examine the associations between prediabetes in early pregnancy (A1C of 5.7–6.4%) and risks of GDM and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and Methods

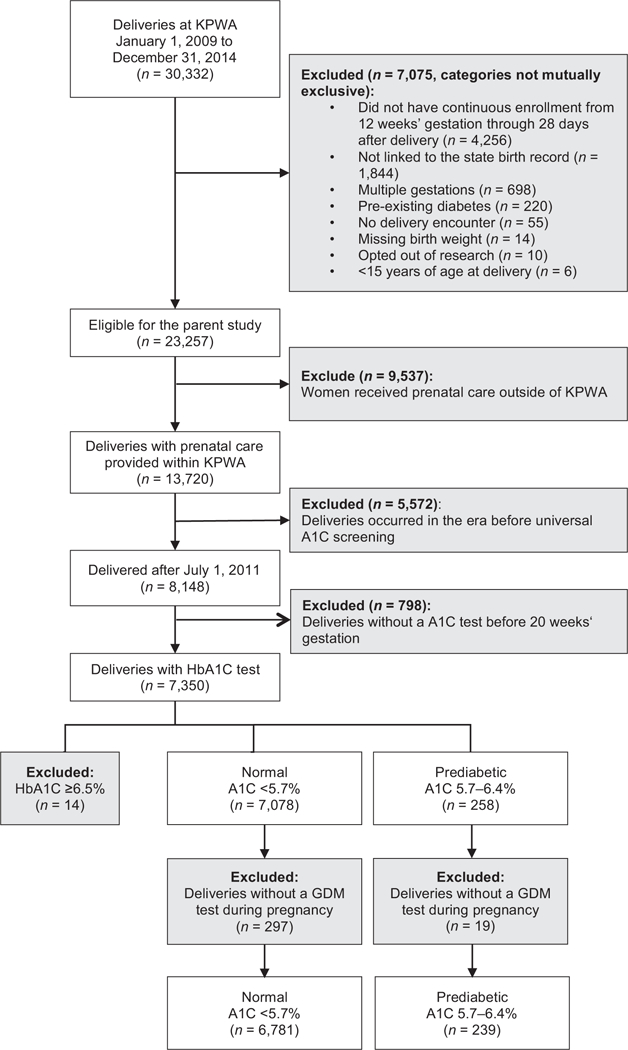

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from KPWA. In 2011, KPWA switched from the traditional two-step approach6 to IADPSG’s one-step approach4 to diagnose and treat GDM. Specifically, the new GDM guideline required: (1) universal A1C testing at the first prenatal visit; (2) a 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test as the diagnostic testing for GDM at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation; (3) initiation of pharmacologic treatment in women with GDM if fasting glucose > 90 mg/dL or 1-hour postprandial > 120 mg/dL; and (4) A1C tests at 3 months postpartum and annually in women with GDM to screen for diabetes. This study was part of a larger research project evaluating clinical outcomes associated with this new guideline.13 The parent study included all singleton live births between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2014, to women enrolled in KPWA. Only women with continuous enrollment in KPWA from 12 weeks’ gestation through 28 days after delivery were included. For the present analysis, we focused on women delivering between July 1, 2011, and December 31, 2014, a period during which most pregnant women received an A1C test before 20 weeks’ gestation. We excluded women if they (1) did not undergo an A1C test, (2) did not have any GDM diagnostic test, or (3) had an early-pregnancy A1C value ≥ 6.5%. Other exclusion criteria are described in ►Fig. 1.This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI).

Fig. 1.

Study Inclusions and exclusions.

We used data from KPWA’s electronic health record (EHR) linked to Washington state birth certificate data.14 KPWA’s EHR data include demographics, enrollment, inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, pharmacy dispensing, type of insurance, and laboratory results (e.g., A1C values). As most pregnant women cared by KPWA clinicians delivered at contracted hospitals, we did not have direct access to inpatient neonatal records. Instead, we had complete information on diagnoses and procedures for the delivery hospital stay because hospitals must submit this information to KPWA to receive payment. We used birth certificates to supplement these data with other important maternal and neonatal information, including gestational age, maternal education, infant sex, infant birth weight, and women’s pre- and postpregnancy height and weight (see ►Supplementary Table S1 [available in the online version] for variable definitions and data sources). We estimated the pregnancy start date by subtracting gestational age at delivery (obtained from the birth certificate) from the delivery date (obtained from the EHR). Gestational ages were recorded in weeks on the birth certificate and were converted to days assuming all births occurred on the 4th day of the week.

Our exposure of interest was prediabetes in early pregnancy, defined as A1C values of 5.7 to 6.4% between pregnancy start date through 20 weeks’ gestation. While we chose a 20-week cutoff to be consistent with previous studies,9,11 most women in our delivery system were screened for over diabetes at their first prenatal visits around 8 to 12 weeks’ gestation. A1C value of <5.7% were considered normal.5 For women with multiple A1C values before 20 weeks’ gestation, we used the earliest result. Pregnancy outcomes assessed in this study were a diagnosis of GDM, preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, induction of labor, large or small for gestational age (>90th or <10th percentile according to the Washington state sex-specificbirth weight data),15 preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation), admission to Level 3 or 4 neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal hypoglycemia, and macrosomia (birth weight ≥ 4,500 g). Among women diagnosed with GDM, we assessed receipt of pharmacologic treatment for GDM, including insulin, sulfonylureas, and metformin. For deliveries with available pre- and postpregnancy height and weight (96% of the population), we defined excessive gestational weight gain according to the ACOG classification scheme (see ►Supplementary Table S1, available in the online version).16

The associations between prediabetes and pregnancy outcomes were estimated using modified Poisson’s regression with a robust error variance that accounted for correlation between multiple deliveries to the same woman and the misspecified variance structure when using the Poisson’s model for binary outcomes.17,18 Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were adjusted for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, parity, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), chronic hypertension, smoking during pregnancy, and Medicaid insurance status (categorized as shown in ►Table 1). For variables with <1% missing data, we excluded women missing these variables from the multivariable models. A missing category was created for variables with more frequent missing values, namely, BMI and race/ ethnicity, and women missing only these variables were included in the multivariate analysis. We also evaluated effect modification by prepregnancy obesity and race/ethnicity by including interaction terms between prediabetes and these two variables in the model. Early in our study period, KPWA was in a process of adopting the one-step IADPSG approach and some women still received the two-step approach to diagnosing GDM. The one-step approach results in a much higher proportion of women being diagnosed with GDM because of its lower threshold for diagnosis.19 As this practice change could have impacted our results, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to women who received the one-step approach to GDM testing for the more prevalent outcomes including GDM diagnosis, excessive weight gain, and primary cesarean delivery. In a post hoc analysis, we plotted a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using continuous A1C values to predict GDM risk in a fully adjusted logistic regression model and reported the area under the curve.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnancies, by prediabetes status in early pregnancya

| Normal (A1C <5.7%) | Prediabetic (A1C 5.7–6.4%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 6,781 | n = 239 | |||

| n | Col %b | n | Col % | |

| Gestational age at the time of the A1C test (median, wk [interquartile ranges]) | 8 (7, 9) | 8 (7, 10) | ||

| Delivery, y | ||||

| 2011 | 957 | (14.1) | 51 | (21.3) |

| 2012 | 1,969 | (29.0) | 67 | (28.0) |

| 2013 | 1,961 | (28.9) | 71 | (29.7) |

| 2014 | 1,894 | (27.9) | 50 | (20.9) |

| Age at delivery (y) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 31.0 (5.1) | 32.5(5.2) | ||

| 15–24 | 742 | (10.9) | 18 | (7.5) |

| 25–29 | 1,785 | (26.3) | 48 | (20.1) |

| 30–34 | 2,622 | (38.7) | 84 | (35.1) |

| 35+ | 1,632 | (24.1) | 89 | (37.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4,764 | (70.3) | 89 | (37.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1,048 | (15.5) | 73 | (30.5) |

| Hispanic | 428 | (6.3) | 21 | (8.8) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 418 | (6.2) | 49 | (20.5) |

| Other/unknown | 123 | (1.8) | 7 | (2.9) |

| Years of education | ||||

| ≤ 12 | 967 | (14.3) | 51 | (21.5) |

| > 12 | 5,782 | (85.7) | 186 | (78.5) |

| Missing | 32 | 2 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | 1,180 | (17.4) | 55 | (23.0) |

| Married | 5,600 | (82.6) | 184 | (77.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | (0) | |

| Had Medicaid health insurance | 110 | (1.6) | 14 | (5.9) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||||

| No | 6,569 | (97.0) | 226 | (94.6) |

| Yes | 201 | (3.0) | 13 | (5.4) |

| Missing | 11 | 0 | ||

| Prepregnancy BMI | ||||

| Low/normal (<25 kg/m2) | 3,514 | (53.8) | 52 | (23.1) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 1,634 | (25.0) | 69 | (30.7) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 1,381 | (21.2) | 104 | (46.2) |

| Missing | 252 | 14 | ||

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 3,533 | (52.2) | 96 | (40.2) |

| 1 | 2,239 | (33.1) | 82 | (34.3) |

| 2+ | 998 | (14.7) | 61 | (25.5) |

| Missing | 11 | 0 | (0) | |

| Male infant | 3,519 | (51.9) | 129 | (54) |

| Had chronic hypertension | 173 | (2.6) | 22 | (9.2) |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Early pregnancy A1C value was defined using A1C measured before 20 weeks’ gestation. For 3% of women with multiple measurements, the earliest value was used.

Numbers in parentheses are interquartile ranges for gestational age at the time of the A1C test, standard deviation for mean age at delivery, and column percentages for all other categorical variables.

Results

There were 7,020 deliveries meeting study eligibility criteria (►Fig. 1), including 239 (3.4%) with an A1C of 5.7 to 6.4% (prediabetic), and 6,781 with a normal value (►Table 1). Overall, women in our study were mostly older than 25 years, non-Hispanic white, educated with high school level or more. Of all women, 53% had normal prepregnancy BMI and 52% were nulliparous. The median gestational age at the time of the A1C test was 8 weeks and 2 days for both groups. About 95% of the A1C tests were conducted at or before 13 weeks and 5 days, and 14 weeks and 2 days for women with normal and prediabetic A1C levels, respectively. Compared with pregnancies with normal A1C, women with prediabetes were somewhat older (mean age 32.5 vs. 31.0) and more likely to be obese (46.2 vs. 21.2%). They were less likely to be non-Hispanic white (37.2 vs. 70.3%), married (77.0 vs. 82.6%), nulliparous (40.2 vs. 52.2%), and to have more than 12 years of education (78.5 vs. 85.7%). They were more likely to have Medicaid insurance (5.9 vs. 1.6%) and chronic hypertension (9.2 vs. 2.6%) and to have smoked during pregnancy (5.4 vs. 3.0%).

In the multivariate analysis performed in 6,964 deliveries (99.2%) with complete data for key variables, we assessed the association between prediabetes and risk of adverse outcomes independent of potential confounders including prepregnancy BMI. Of women with prediabetes, 47.7% received a diagnosis of GDM compared with 10.6% of women with normal A1C levels (adjusted RR: 2.8, 95% CI: 2.4–3.3) (►Table 2). Women with prediabetes were less likely to gain higher than recommended weight during pregnancy as compared with women with normal A1C levels (36.6 vs. 48.4%, adjusted RR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.6–0.9). There was some suggestion for increased risks of macrosomia (2.5 vs. 1.8%, adjusted RR: 1.7, 95% CI: 0.7–4.2) and preterm birth (8.4 vs. 4.9%, adjusted RR: 1.4, 95% CI: 0.9–2.2) in women with prediabetes, but these associations were not statistically significant. Prediabetes in early pregnancy was not associated with other adverse outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (adjusted RR: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.8–1.3) and having a large-for-gestational age infant (adjusted RR: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.7–1.5). Neither of the interactions tested was statistically significant at the 5% level, thus we did not further stratify associations by prepregnancy BMI or race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Prediabetes status in early pregnancy and pregnancy outcomesa

| Outcomes | Prediabetes status in early pregnancy | Age adjusted relative risk (95% CI)b |

Multivariate adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal A1C <5.7% |

PrediabeticA1C 5.7–6.4% |

|||||

| n = 6,727 | n = 237 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Maternal outcomes | ||||||

| Gestational diabetes diagnosis | 710 | 10.6 | 113 | 47.7 | 4.18 (3.59, 4.87) | 2.78 (2.37, 3.25) |

| Higher than recommended weight gainc | 3147 | 48.4 | 83 | 36.6 | 0.77 (0.65, 0.92) | 0.74 (0.63, 0.88) |

| Primary cesarean deliveryd | 1,100 | 18.6 | 42 | 23.1 | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | 1.01 (0.78, 1.32) |

| Preeclampsia | 249 | 3.7 | 14 | 5.9 | 1.60 (0.95, 2.69) | 1.11 (0.66, 1.87) |

| Induction of labor | 1,867 | 27.8 | 80 | 33.8 | 1.21 (1.01, 1.46) | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) |

| Neonatal outcomes | ||||||

| Large for gestational age | 604 | 9.0 | 21 | 8.9 | 0.98 (0.63, 1.51) | 1.01 (0.66, 1.54) |

| Small for gestational age | 465 | 6.9 | 24 | 10.1 | 1.48 (1.00, 2.18) | 1.22 (0.83, 1.77) |

| Preterm birth | 327 | 4.9 | 20 | 8.4 | 1.68 (1.09, 2.59) | 1.42 (0.91, 2.23) |

| NICU admission | 308 | 4.6 | 16 | 6.8 | 1.47 (0.90, 2.40) | 1.33 (0.81, 2.18) |

| Neonatal hypoglycemia | 117 | 1.7 | 7 | 3.0 | 1.68 (0.79, 3.57) | NAe |

| Macrosomia | 121 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.5 | 1.46 (0.58, 3.71) | 1.68 (0.67, 4.23) |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Women who did not have complete data were excluded (n = 54, 0.8% of the cohort). Early pregnancy A1C value was defined as A1C value measured before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Relative risks were estimated by modified Poisson’s regression with robust standard errors. Numbers outside the parentheses are point estimates of the relative risks and numbers inside the parentheses are associated 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, race/ ethnicity, education, parity, prepregnancy BMI, chronic hypertension, smoking during pregnancy, and Medicaid insurance.

Restricted to 6,731 women with data on gestational weight gain and classified according to ACOG’s guideline on gestational weight gain.15

Restricted to 5,103 women who did not have a previous cesarean delivery.

Number too small to yield a reliable estimate.

To evaluate the severity of GDM, we assessed the use of diabetes medications in 823 women diagnosed with GDM (►Table 3). Of the prediabetic women who were later diagnosed with GDM, 62.0% received pharmacologic treatment, compared with 40.0% of women with normal A1C levels (adjusted RR: 1.4,95% CI: 1.2–1.7). Specifically, women with prediabetes who were later diagnosed with GDM were 1.5-fold more likely to receive insulin therapy than those with normal A1C levels who later developed GDM. Very few women in either group received oral agents to treat GDM, in accordance with KPWA’s GDM guideline which emphasized insulin as first-line therapy.

Table 3.

Prediabetes status in early pregnancy and receipt of diabetes treatment among women diagnosed with gestational diabetesa

| Use of diabetes treatment | Prediabetes status in early pregnancy | Age adjusted relative risk (95% CI)b |

Multivariate adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal A1C <5.7% | Prediabetic A1C 5.7- 6.4% |

|||||

| n = 710 | n = 113 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Any diabetes treatment | 284 | 40.0 | 70 | 62.0 | 1.49 (1.26, 1.77) | 1.40 (1.17, 1.67) |

| Insulin | 241 | 33.9 | 60 | 53.1 | 1.51 (1.23, 1.85) | 1.45 (1.17, 1.80) |

| Sulfonylurea | 31 | 4.4 | 8 | 7.1 | 1.58 (0.76, 3.30) | 1.19 (0.50, 2.84) |

| Metformin | 39 | 5.5 | 12 | 10.6 | 1.84 (1.00, 3.38) | 1.44 (0.71, 2.92) |

Abbreviations: A1C, hemoglobin A1C; CI, confidence interval.

Use of diabetes treatment defined as any prescription fill for diabetes medications after 12 weeks’ gestation.

Relative risks were estimated by modified Poisson’s regression with robust standard error. Numbers outside the parentheses are point estimates of the relative risks and numbers inside the parenthesis are 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate analysis adjusted forage at delivery, race/ethnicity, education, parity, prepregnancy BMI, chronic hypertension, smoking during pregnancy, and Medicaid insurance.

When we restricted our analyses to 6,629 women who received the one-step approach to GDM testing (94% of the cohort), our results did not change substantially.

To evaluate the accuracy of early pregnancy A1C in predicting GDM, we calculated prediction parameters using our data. Among 823 women diagnosed with GDM, only 113 had prediabetes, suggesting that if used as a screening tool with a cutoff of 5.7%, early pregnancy A1C test would have a low sensitivity of 13.7% (or a false-negative rate of 86.3%). Similarly, among 6,141 women not diagnosed with GDM, 6,017 had normal A1C, corresponding to a specificity of 98.0% (or a false-positive rate of 2.0%). In the post hoc ROC curve analysis (►Supplementary Fig. S1, available in the online version), the area under the curve was 0.716.

Comment

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based U.S. study in a setting with universal A1C screening that assessed whether prediabetes (A1C of 5.7–6.4%) in early pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. We observed that 48.4% of women with a prediabetic A1C later developed GDM, corresponding to a 2.8-fold increased risk of GDM relative to women with normal A1C. We did not observe differences in other adverse pregnancy outcomes by prediabetes status in early pregnancy.

Consistent with prior studies,9–11 our finding suggests women with prediabetes in early pregnancy represent a high-risk group for GDM. Of note, the proportion of women who developed GDM in the prediabetic group was higher in our study compared with the other U.S. studies (27–29%),9,10 and was close to 50% observed in a New Zealand study when an A1C cutoff of 5.9% was used.11 Several factors could contribute to this higher prevalence, including the use of the one-step approach to diagnosing GDM, and a higher prevalence of obesity in prediabetic women in our study as obesity is a strong risk factor for GDM,20 However, in our multivariate analysis, we adjusted BMI and thus the associations we presented were after accounting for obesity.

A critical question is whether the excess risk of GDM associated with prediabetes could be prevented by early intervention. In the general population, diet and exercise interventions may prevent progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes.7,8 Only one randomized trial of interventions in prediabetic pregnant women has been published.21 In a medical center in California, women with A1C levels of 5.7 to 6.4% were randomized to either receive treatment for GDM with diet, blood glucose monitoring, and insulin (n = 42) or usual care (n = 41). The authors reported that 45% of women in the treatment group versus 56% in the control group developed GDM (RR: 0.8, 95% Cl: 0.5–1.2). Although underpowered, findings from this study show some suggestion for a risk reduction by the early intervention. Given the increasing prevalence of GDM and obesity in pregnant women and poorer pregnancy outcomes associated with GDM,22,23 even a modest risk reduction in a high-risk group warrants further investigation.

We did not observe differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes according to prediabetes status among our study population of women with A1C of <6.5%.This is consistent with two prior U.S. studies but not with the New Zealand study, which observed higher risks of preeclampsia and shoulder dystocia among women with A1C levels of 5.9 to 6.4%.9–11 Potential differences in practice around detecting and treating GDM in the United States versus New Zealand may partly explain discrepancies in the results. For example, only 55% of women in the New Zealand population (54% in women with normal A1C and 69% in prediabetic women) received GDM testing later in pregnancy compared with 94 to 100% in the U.S. studies, including the present one. First, selectively testing high-risk women may have introduced bias and somewhat exaggerated associations between prediabetes and adverse birth outcomes. Second, although we had a larger sample of women with prediabetes than previous studies (256 included in the outcome analysis in our study compared with 55–200 in prior studies9–11), adverse pregnancy outcomes were still relatively rare, which may have limited our ability to detect an association. Another explanation for the lack of an observed association could be that a prediabetic A1C test result led to additional medical attention and behavior change among affected women in our population. Our obstetrical leadership confirmed that no systematic intervention was given to women with prediabetes at KPWA during the study period. However, some providers may have offered lifestyle counseling and earlier GDM testing to these women. Supporting this scenario, we observed a lower prevalence of excessive weight gain (37 vs. 48%) and earlier testing of GDM in this group (on average, 2 weeks earlier than those with normal A1C). The only randomized trial conducted to date among prediabetic women was underpowered to detect differences in pregnancy outcomes.21 More research is needed to elucidate the potential of early interventions to prevent adverse outcomes.

We observed a higher prevalence of pharmacological treatment after GDM diagnosis in women with prediabetes in early pregnancy as compared with those with normal A1C values. One possible interpretation is that prediabetes in early pregnancy may signal a more severe type of GDM. Indirectly, this suggests that early pregnancy A1C values may have clinical utility in identifying women who are at higher risk for future development of type 2 diabetes. Approximately 18 to 50% of women with a history of GDM develop type 2 diabetes within 5 years of delivery, and risk is higher among those who require pharmacological treatment during pregnancy.24 We currently do not have follow-up data on women that would allow us to examine the relationship between early pregnancy A1C and future diabetes risk. Among the nonpregnant population, individuals with A1C of 5.7 to 6.4% have been shown to have a sixfold higher risk of developing diabetes within 5 years compared with those with A1C in the normal range.25 Current ADA guidelines recommend that women with a history of GDM be tested for diabetes every 1 to 3 years after delivery, with the frequency of testing varies depending on risk factors such as obesity, family history, and need for pharmacological treatment during pregnancy.26 Future research should examine whether prediabetes in early pregnancy can identify women at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes who would be candidates for closer monitoring.

It is important to note that the A1C test in early pregnancy should not be used alone to screen for GDM and it was not intended for this purpose in our health care system. We reported its poor sensitivity and less optimal specificity. Our results were consistent with prediction parameters reported in previous studies evaluating first trimester A1C values, for example, 13% sensitivity and 94% specificity for an A1C cutoff of 5.7%,10 and 33% sensitivity and 89% specificity for an A1C cutoff of 5.6%.27 Thus, our findings together with others do not support use of early pregnancy A1C test to screen or diagnose GDM.

Strengths of our study include that we studied a large population-based cohort of women in a setting with universal A1C testing in early pregnancy, minimizing the potential for selection bias. Without a universal testing policy, providers may preferentially order the test for women who are already at higher risk of GDM and thus the association of higher A1C value and a subsequent GDM diagnosis may be exaggerated. Furthermore, our study included a larger number of women with prediabetes than any prior study. We had rich data from both EHR and state birth certificates, allowing us to assess many clinically important pregnancy outcomes and adjust for a wide range of potential confounders.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study population consists of predominantly privately insured women who had access to medical care. It is possible that women with prediabetes may have received additional medical advice and closer monitoring, which if true could have attenuated the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes conveyed by prediabetes in early pregnancy. Second, we used ICD-9 codes to define GDM which may have introduced some level of misclassification and this coding error may have biased our results toward the null. Finally, the prevalence of prediabetes was relatively low in our population, and in women with prediabetes only 79 women had A1C of ≥ 5.9%, limiting our ability to perform further analysis to focus on women with more severe prediabetes (i.e., A1C of 5.9–6.4% as defined in one prior study11).

In summary, in this population-based cohort study, we observed that 3.6% of pregnant women had prediabetes in early pregnancy. Compared with women with normal A1C levels, women with prediabetes had a 2.8-fold higher risk of GDM and a 1.4-fold higher risk of requiring pharmacologic treatment if they developed GDM. There were no differences in other adverse pregnancy outcomes according to prediabetes status. The A1C test does not require fasting and can be easily incorporated into early prenatal laboratory panels. Our results highlight the possible utility of early pregnancy A1C screening to identify women at high risk for GDM, and based on past research,21 this risk may be modifiable. Future research is needed to further elucidate whether risk of GDM in this group can be reduced through early lifestyle interventions to ultimately achieve better pregnancy outcomes and a lower long-term diabetes risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from Group Health Foundation’s Momentum Fund. Dr. Chen’s time was funded by Group Health Foundation Fellowship.

O.Y. received funding as a biostatistician from a research grant awarded to the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) from Bayer. S.M.S. has worked on grants awarded to KPWHRI by Pfizer and also serves as a co-investigator on grants awarded to KPWHRI from Syneos Health, who is representing a consortium of pharmaceutical companies carrying out FDA-mandated studies regarding the safety of extended-release opioids.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All other authors report no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Chen W, Sacks DA. Trends in the prevalence of preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus among a racially/ethnically diverse population of pregnant women, 1999–2005. Diabetes Care 2008;31(05):899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015;314(10):1021–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng TY, Ehrlich SF, Crites Y, et al. Trends and racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of pregestational type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Northern California: 1996–2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(02):177.e1–177.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. ; International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33(03):676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40(Suppl 1)S11–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 180: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130(01): e17–e37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. ; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006;368(9548):1673–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374(9702):1677–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong A, Serra AE, Gabby L, Wing DA, Berkowitz KM. Use of hemoglobin A1c as an early predictor of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211(06):641.e1–641.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osmundson SS, Zhao BS, Kunz L, et al. First trimester hemoglobin A1c prediction of gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol 2016;33 (10):977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes RC, Moore MP, Gullam JE, Mohamed K, Rowan J. An early pregnancy HbA1c ≥5.9% (41 mmol/mol) is optimal for detecting diabetes and identifies women at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 2014;37(11):2953–2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.California Diabetes in Pregnancy Program (Internet). Available at: http://www.cdappsweetsuccess.org. Accessed January 11, 2018

- 13.Pocobelli G, Yu O, Fuller S, et al. One-step approach to identifying gestational diabetes mellitus: association with perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132(04):859–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin E, Johnson K, Berthoud H, Dublin S. Linking mothers and infants within electronic health records: a comparison of deterministic and probabilistic algorithms. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24(01 ):45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipsky S, Easterling TR, Holt VL, Critchlow CW. Detecting small for gestational age infants: the development of a population-based reference for Washington state. Am J Perinatol 2005;22(08):405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 548: weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121(01):210–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(07):702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42(01):121–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown FM, Wyckoff J. Application of one-step IADPSG versus two-step diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes in the real world: impact on health services, clinical care, and outcomes. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17(10):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetesmellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30(08):2070–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osmundson SS, Norton ME, El-Sayed YY, Carter S, Faig JC, Kitzmiller JL. Early screening and treatment of women with prediabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol 2016;33(02): 172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, et al. ; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358(19):1991–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer O, Yogev Y, Most O, Xenakis EM. Gestational diabetes: the consequences of not treating. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(04): 989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002;25(10):1862–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heianza Y, Hara S, Arase Y, et al. HbA1c 5.7–6.4% and impaired fasting plasma glucose for diagnosis of prediabetes and risk of progression to diabetes in Japan (TOPICS 3): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2011;378(9786):147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Diabetes Association. 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2017;40(Suppl 1)S114–S119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benaiges D, Flores-Le Roux JA, Marcelo I, et al. Is first-trimester HbA1c useful in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;133:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.