Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Given an aging HIV population, we aimed to determine the prevalence of HIV for long-stay residents in US nursing homes (NHs) between 2001 and 2010 and to compare characteristics and diagnoses of HIV-positive (HIV+) and negative (HIV−) residents. Also, for residents with dementia diagnoses, we compared antipsychotic (APS) receipt by HIV status.

DESIGN

A cross-sectional comparative study

SETTING

NHs in the 14 states accounting for 75% of persons living with HIV

PARTICIPANTS

9,245,009 long-stay NH residents

MEASUREMENTS

Using Medicaid fee-for-service claims data in years 2001 to 2010 together with Medicare resident assessment and Chronic Condition Warehouse data, we identified long-stay (>89 days) NH residents by HIV status and dementia presence. We examined dementia presence by age groups and APS receipt by younger (<65) versus older (65+) residents, using logistic regression.

RESULTS

Between 2001 and 2010, the prevalence of long stay residents with HIV in NHs increased from 0.7% to 1.2%, a 71% increase. Long-stay residents with HIV were younger and less often female or White. For younger NH residents, rates of dementia were 20% and 16% for HIV+ and HIV− residents, respectively; they were 53% and 57% (respectively) for older residents. In adjusted analyses younger HIV+ residents with dementia had greater odds of APS receipt than did HIV− residents (AOR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2,1.4), but older HIV residents had lower odds (AOR 0.9; 95% CI 0.8,0.9).

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of long-stay HIV+ NH residents has increased over time, and given the rapid aging of the HIV population, this increase is likely to have continued. This study raises concern about potential differential quality of care for (younger) residents with HIV in NHs, but not for those 65 and older. These findings contribute to the evidence base needed to ensure high-quality care for younger and older HIV+ residents in NHs.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, dementia, nursing homes, antipsychotics, Alzheimer’s disease

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, an estimated 45% of persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the U.S. were 50 years of age or older.1 Care for aging persons with HIV is complex since they experience complications of HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART), and compared to controls, have higher rates of non-acquired immune deficiency (AIDS) conditions including particular cancers and pulmonary, cardiovascular and liver diseases.2 Given this higher prevalence of chronic conditions along with the aging of persons living with HIV, it is likely that the prevalence of persons with HIV in nursing homes (NH) is increasing and will continue to do so. Studies of HIV in U.S. NHs are relatively old (using data prior to 2000) and as such do not capture changes in the prevalence of HIV. Furthermore, they do not compare HIV positive (HIV+) and HIV negative (HIV−) residents and/or only reflect care provided in a single NH.3–6

Beyond the above conditions, and given dementia’s high prevalence7 and focus of care for long-stay NH residents, we were particularly interested in the relative prevalence and management of dementia in HIV+ as compared to HIV− residents. Also, in addition to the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and other dementias observed for HIV− NH residents, approximately 5% of persons with HIV have a diagnosis of HIV-associated dementia (post the advent of combination ART).8, 9 In NHs, the management of the behaviors and psychological symptoms that often accompany dementia and that are exhibited by most (over 80%) dementia residents is particularly challenging.10, 11 Antipsychotic medications (APS) are frequently used to control behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, despite the known serious complications and adverse consequences (including death) associated with their use.12 Indeed, the prevalence of APS prescribed for residents with dementia is an important NH quality indicator.13, 14 Furthermore, there are added concerns about APS use for HIV+ residents, including drug interactions between second generation antipsychotics and ART use,15 which may contribute to an increased risk of hyperlipidemia, hypertension and diabetes.16

This study uses population-based Medicaid and minimum data set (MDS) data along with data from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services’ (CMS) Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW) to identify a population of HIV+ long-stay NH residents in the 14 U.S. states with the highest HIV prevalence.17 Using these data we aimed to: 1) understand the prevalence of HIV in NHs from 2001 to 2010; 2) contrast sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of HIV+ and HIV− residents; and, using APS use as a quality indicator, 3) describe how dementia care may differ by HIV status.

METHODS

Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional comparative study of long-stay (stays of 90+ days) NH residents by HIV presence in the 14 states accounting for 75% of the HIV prevalence in the U.S.: New York, California, Florida, Texas, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Georgia, North Caroline, Virginia, Louisiana, Ohio, and Massachusetts.17 Given that HIV diagnoses are redacted from the MDS in some U.S. states (California, Texas, Maryland, New Jersey, and Illinois) and that large proportions of HIV+ residents admitted to NHs are Medicaid beneficiaries,4, 6 we supplemented our identification of HIV by using 2001–2010 Medicaid Analytic Extract (MAX) data. We also used 2006–2010 CCW data to identify HIV. The xxxx Institutional Review Board approved this study.

MDS data were used to identify HIV+ residents and to characterize them across several dimensions. The MDS is a federally mandated assessment required for all residents in Medicare- or Medicaid-certified facilities. Federal regulations require NHs to complete MDS assessments for each resident at admission and at least quarterly thereafter.18 The reliability and validity of the MDS data is generally high.19–22 The CMS CCW applies to Medicare and Medicaid enrollees in the US and is a research database mandated by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. For beneficiaries with 62 chronic conditions, it provides researchers with linked Medicare and Medicaid claims and assessment data across beneficiaries’ continuum of care. Expert-derived algorithms, (based on diagnosis codes from medical claims data) are used to identify beneficiaries with one or more of the 62 chronic conditions (one of which is HIV/AIDS).22

Of note, CMS redacted from the Medicaid MAX data all claims containing diagnoses of alcohol or drug addiction. Therefore, if all or most of an individual’s Medicaid claims included a drug or alcohol diagnosis, we would have been unable to identify him/her as having HIV using the MAX data (see Figure, Supplemental Material S1). However, this scenario is unlikely.

Study Sample

Using MAX data we first identified Medicaid beneficiaries who had a “likely” or “possible” HIV diagnosis (see Figure, Supplemental Material S1). Data on Medicaid beneficiaries with “likely” HIV were merged with MDS data from 2001–2010 to determine which beneficiaries had NH use after an HIV diagnosis. To these identified NH HIV residents, we added those residents who had an MDS or CCW HIV diagnoses.

We used the 2001–2010 MDS data for residents with and without (identified) HIV to classify residents as having long-stays by determining whether they had quarterly or annual MDS assessments (i.e., both of which require at least 90-day stays). In the study years and states, 9,245,009 NH residents had long-stays and 92,493 (1%) of these had HIV. To derive our study’s prevalence sample, we randomly chose for each resident one quarterly or annual MDS assessment (dated after first documentation of HIV for HIV+ residents) to represent each unique resident in the study years and states. Also, using the MDS checkbox diagnosis of “Alzheimer’s disease” or “Dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease” or a coded dementia diagnosis on the MDS, we classified residents as having AD, or non-AD dementia.21–23

Study Variables

We extracted resident-level data from the randomly selected quarterly or annual MDS. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender and race/ethnicity. To examine the prevalence of AD and non-AD dementia by age groups, we categorized age as less than 25, 26 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, 85 to 94 and 95+. Other descriptive analyses were stratified by the age group of <65 and 65+. Race/ethnicity was identified as non-Hispanic white, black, Hispanic and other. We also included MDS-derived indicator variables for AD (versus non-AD diagnoses) and for the diagnoses of depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Also, for description only, indicator variables for common NH diagnoses were created. When sociodemographic and diagnosis variables were missing in the selected quarterly or annual MDS, we used values from previous assessments. Last, we included Indicator variables to control for a NH’s state and its location in a metropolitan county (yes/no).

The Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS)24 was used to determine cognitive impairment. This scale ranges from 0 to 6 and was categorized as: intact to mild impairment (0–2), moderate to moderately severe (3–4), and severe to very severe (5–6). To identify the severity of behavioral symptoms, we used the Aggressive Behavior Scale.25 The scale uses MDS data on four core behavioral indicators (verbal aggression, physical aggression, socially inappropriate behavior and aggressive resistance to care) together with their documented frequency. For each behavior, frequency in the last seven days (prior to assessment) is documented (and scored) as: not exhibited (0); occurred 1 to 3 days (1); occurred 4 to 6 days, but less than daily (2); or occurred daily (3). The scale’s score is an aggregate of these scores and ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater severity of behavioral problems.

The outcome of interest in our multivariable analysis is whether a resident received an antipsychotic drug (as documented on the MDS) in the seven days prior to the assessment date. To calculate this outcome, we removed residents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder from the denominator, creating an indicator of potentially inappropriate APS receipt. A similar indicator has been used in the U.S.13 and Canada.14

Last, to control for changes in prescribing post the U.S. Federal Drug Administration’s (FDA) warnings regarding antipsychotics, we included indicator variables to designate whether the a resident’s assessment was completed in calendar years 2000–2005, 2006–2008 or 2009–2010. In April 2005, the FDA issued a “black box” warning regarding atypical APS prescribing because of an observed association between atypical APS use and increased mortality; it extended this warning in June 2008 to include conventional antipsychotics.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to portray HIV and dementia prevalence and to contrast resident characteristics. Logistic regression examined whether APS use was greater for HIV+ residents, controlling for the variables described above. We stratified our multivariate analyses by age (i.e., <65 and 65+) since we observed differing effects for many variables by this categorization and given there was a statistically significant interaction between HIV status and being 65+ (in the non-stratified model).

RESULTS

HIV Prevalence in NHs

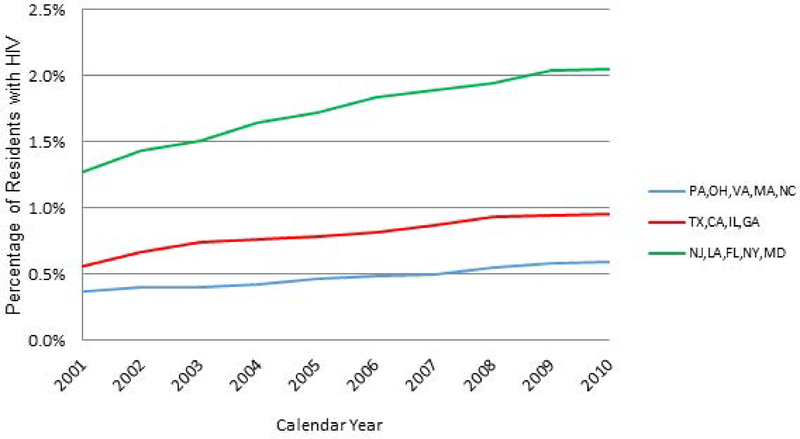

Across states, 0.7% of total long-stay residents had HIV in 2001 and this proportion increased to 1.2% by 2010. Increases in prevalence were greater in states with higher proportions of HIV+ long-stay residents, and greatest in New Jersey, Louisiana, Florida, New York and Maryland (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual Proportion of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents with HIV: By States with Lower to Higher Prevalence of HIV in Nursing Homes. Note: States were categorized into three groups based on their prevalence of HIV in Nursing Homes: <=0.5%: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, Massachusetts, North Carolina; >0.5% & <=1%: Texas, California, Illinois and Georgia; and >1%: New Jersey, Louisiana, Florida, New York and Maryland

Characteristics of HIV+ and HIV− Long-Stay Residents

Using our prevalence sample of long-stay residents in 2001–2010 (N=2,822,110) we found HIV+ residents compared to HIV− residents were younger, more often female, less often White, less often had common NH diagnoses (except renal failure), and more often resided in metropolitan-area NHs (Table 1). HIV+ residents represented only 0.5% of residents 65 or older, but 6% of those less than 65. Overall, 33% of HIV+ residents had dementia diagnoses compared to 52% of HIV− residents; however, there was only an approximate 4 percentage point difference in dementia prevalence when residents were stratified by the <65 and 65+ age groups (Table 1).

Table 1:

Individual Characteristics of Nursing Home Long-Stay Residents by HIV Status and by Younger versus Older Age Groups

| All | <65 | >=65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV− | HIV+ | HIV− | HIV+ | HIV− | HIV+ | |

| Variable | 2,788,358 | 33,752 | 343,307 | 21,078 | 2,445,017 | 12,674 |

| Alzheimer’s disease or other dementiaa | 51.8% | 32.6% | 16.4% | 20.1% | 56.8% | 53.5% |

| Age (mean, (sd)) | 80.0 (13.1) | 60.0 (17.9) | 52.8 (10.1) | 48.0 (9.1) | 83.8 (8.0) | 79.9 (9.0) |

| Female | 66.9% | 42.3% | 44.5% | 32.6% | 70.0% | 58.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 78.7% | 34.8% | 60.5% | 24.4% | 81.3% | 52.1% |

| Black | 14.1% | 50.5% | 28.2% | 60.3% | 12.1% | 34.1% |

| Hispanics | 5.3% | 13.2% | 9.0% | 14.2% | 4.8% | 11.4% |

| Other race | 1.9% | 1.6% | 2.4% | 1.1% | 1.9% | 2.4% |

| Diagnoses | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 23.2% | 12.9% | 12.0% | 6.5% | 24.8% | 23.5% |

| Cancer | 8.8% | 6.2% | 6.2% | 4.6% | 9.2% | 8.7% |

| Renal failure | 8.1% | 11.5% | 10.1% | 11.0% | 7.8% | 12.2% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.1% | 28.0% | 36.0% | 21.9% | 29.3% | 38.2% |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 21.5% | 19.1% | 20.1% | 12.8% | 21.7% | 29.6% |

| COPD | 18.4% | 14.6% | 15.6% | 10.5% | 18.8% | 21.2% |

| ASHD | 12,9% | 6.4% | 5.2% | 2.1% | 14.0% | 13.4% |

| Depression | 43.8% | 38.9% | 42.5% | 37.7% | 44.0% | 40.8% |

| Anxiety | 14.5% | 10.2% | 13.7% | 9.2% | 14.7% | 11.8% |

| Bipolar disorder | 2.6% | 5.2% | 7.5% | 6.9% | 1.9% | 2.5% |

| Schizophrenia | 4.2% | 9.3% | 15.5% | 11.9% | 2.6% | 5.0% |

| ABS scale: 0 | 74.8% | 75.9% | 72.4% | 75.2% | 75.1% | 77.0% |

| ABS scale: 1–2 | 16.3% | 16.3% | 17.9% | 17.0% | 16.1% | 15.2% |

| ABS scale: 3–5 | 6.9% | 6.3% | 7.6% | 6.4% | 6.8% | 6.0% |

| ABS scale: >=6 | 2.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 2.0% | 1.7% |

| CPS scale: 0–2 | 42.3% | 59.6% | 61.2% | 73.0% | 39.7% | 37.3% |

| CPS scale: 3–4 | 40.8% | 26.6% | 25.9% | 20.6% | 42.9% | 36.7% |

| CPS scale: 5–6 | 16.8% | 13.7% | 12.8% | 6.4% | 17.4% | 25.9% |

| Any use of antipsychotics | 25.9% | 30.7% | 35.1% | 34.8% | 24.6% | 24.0% |

| Years: 2001–2005 | 49.5% | 46.5% | 43.9% | 45.6% | 50.3% | 48.1% |

| Years: 2006–2008 | 30.4% | 31.6% | 32.6% | 32.6% | 30.1% | 30.1% |

| Years: 2009–2010 | 20.1% | 21.8% | 23.5% | 21.9% | 19.6% | 21.8% |

| Metropolitan-area nursing home | 83.9% | 93.6% | 87.2% | 96.1% | 83.5% | 89.6% |

sd = standard deviation; ABS = Aggressive Behavior Scale; CPS = Cognitive Performance Scale; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ASHD = Arteriosclerotic Heart Disease

These diagnoses were identified by using the resident assessment (MDS) diagnosis checkboxes of “Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.”

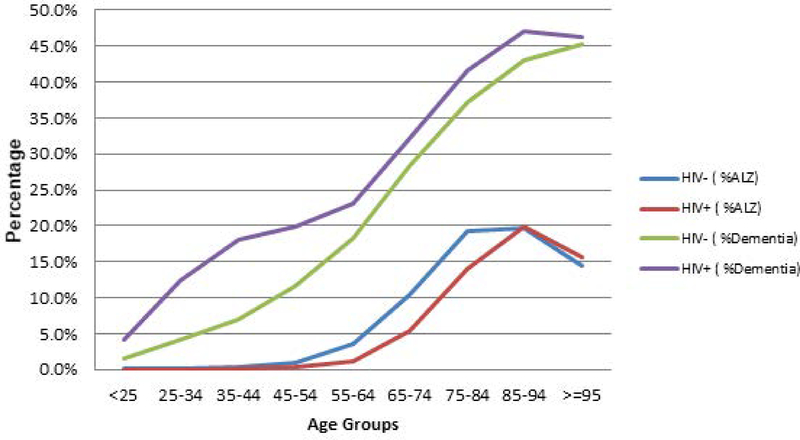

Figure 2 shows that HIV+ residents compared to HIV− residents had a higher prevalence of non-AD dementia until about the age of 85. These differences were greatest for HIV residents between the ages 25 and 54. In contrast, AD was more common for HIV− residents compared to HIV+ residents between approximately the ages of 45 and 85.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) or Non-Alzheimer’s Disease (Non-AD) Dementiaa by Age Group and HIV Status: Long-stay Nursing Home Residents in Years 2001 to 2010. a These diagnoses were identified by using the resident assessment (MDS) diagnosis checkboxes of “Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.”

HIV+ and HIV− Long-Stay Residents with Dementia

Table 2 shows long-stay residents with dementia (but without schizophrenia or bipolar disorders; n=1,386,579) had demographic differences similar to those described above for all residents in the prevalence sample. Within both age groups, HIV+ residents were younger, had less depression and anxiety and lower aggressive behavior scores; those <65 had lower levels of cognitive impairment and lower prevalence of common NH diagnoses (except renal failure). For those 65+, the prevalence of renal failure, diabetes, and CVA was higher for HIV+ residents. Forty-five percent of younger HIV+ residents had APS use compared to 43.8% of younger HIV− residents; for older residents, this receipt was 28.0% compared to 31.8% (respectively).

Table 2:

Individual Characteristics of Long-Stay Nursing Home Resident with Dementiaa but without Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder by HIV Status and Younger versus Older Age Groups

| ALL | <65 | >=65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV− | HIV+ | HIV− | HIV+ | HIV− | HIV+ | |

| 1,376,898 | 9,681 | 45,060 | 3,433 | 1,331,830 | 6,248 | |

| Age (mean (sd)) | 84.1 (8.8) | 70.6 (17.7) | 56.8 (7.0) | 49.6 (8.6) | 85.0 (7.3) | 82.2 (8.4) |

| Female | 70.6% | 50.7% | 42.6% | 28.1% | 71.5% | 63.1% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 81.1% | 43.2% | 61.6% | 26.5% | 81.7% | 52.4% |

| Black | 12.4% | 42.0% | 27.1% | 58.6% | 11.9% | 32.9% |

| Hispanic | 4.9% | 12.9% | 9.4% | 14.0% | 4.7% | 12.3% |

| Other | 1.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 0.9% | 1.7% | 2.5% |

| Diagnoses | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 20.9% | 16.7% | 9.8% | 5.3% | 21.3% | 22.9% |

| Cancer | 7.6% | 6.1% | 4.1% | 3.2% | 7.7% | 7.7% |

| Renal failure | 6.4% | 9.6% | 8.0% | 8.4% | 6.4% | 10.2% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25.2% | 29.5% | 31.1% | 19.1% | 25.0% | 35.2% |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 19.9% | 24.7% | 27.8% | 16.2% | 19.7% | 29.4% |

| COPD | 15.5% | 15.0% | 12.8% | 8.1% | 15.6% | 18.8% |

| ASHD | 13.6% | 10.5% | 6.2% | 2.0% | 14.0% | 15.1% |

| Depression | 45.9% | 41.3% | 48.9% | 39.4% | 45.8% | 42.3% |

| Anxiety | 15.3% | 11.7% | 15.2% | 10.0% | 15.3% | 12.6% |

| ABS scale: 0 | 68.6% | 71.5% | 63.7% | 69.8% | 68.7% | 72.5% |

| ABS scale: 1–2 | 19.3% | 18.4% | 21.3% | 19.5% | 19.2% | 17.7% |

| ABS scale: 3–5 | 9.2% | 7.7% | 11.2% | 8.0% | 9.1% | 7.5% |

| ABS scale: >=6 | 3.0% | 2.4% | 3.8% | 2.7% | 2.9% | 2.2% |

| CPS scale: 0–2 | 20.4% | 28.8% | 27.5% | 47.5% | 20.2% | 18.5% |

| CPS scale: 3–4 | 53.8% | 42.4% | 46.2% | 40.2% | 54.1% | 43.6% |

| CPS scale: 5–6 | 25.7% | 28.7% | 26.2% | 12.2% | 25.7% | 37.7% |

| Any use of antipsychotics | 32.2% | 34.1% | 43.8% | 45.2% | 31.8% | 28.0% |

| Years: 2001–2005 | 49.5% | 49.1% | 43.6% | 46.8% | 49.7% | 50.4% |

| Years: 2006–2008 | 30.3% | 29.3% | 32.0% | 30.2% | 30.3% | 28.8% |

| Years: 2009–2010 | 20.2% | 21.5% | 24.4% | 23.0% | 20.0% | 20.7% |

| Metropolitan-area nursing home | 84.1% | 91.6% | 85.4% | 95.0% | 84.1% | 89.7% |

sd = standard deviation; ABS = Aggressive Behavior Scale; CPS = Cognitive Performance Scale; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ASHD = Arteriosclerotic Heart Disease

Dementia was identified by using the resident assessment (MDS) diagnosis checkboxes of “Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.”

Controlling for potential confounders, HIV+ residents <65 had a 24% greater odds of APS receipt than similar HIV− residents (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.2; 95% CI 1.15, 1.34; Table 3). However, older HIV+ residents (versus HIV− residents) had lower odds of APS receipt (AOR 0.82; 95% CI 0.77, 0.87). The odds ratios and significance levels for many confounders were similar across the younger and older age groups, and in the expected directions. However, for some confounders this was not the case. For example, younger residents having the highest aggressive behavior score (> 6; compared to no aggressive behaviors) had much greater odds of APS use than did comparable older residents (AOR of 5.03 versus 3.79, respectively). Also, the AORs for APS use appear to be significantly different for younger and older residents in many states and for those residents in metropolitan-area NHs (Table 3).

Table 3:

Multivariate Regression Analyses—HIV Status and Receipt of Antipsychotic Medications for Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents with Dementiaa (but without Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder)

| age<65, N=48,268 | Age>=65, N=1,334,366 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | AOR | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

| HIV | 1.24 | <.001 | 1.15 | 1.34 | 0.82 | <.001 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| Age | 0.99 | <.001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | <.001 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Female | 0.83 | <.001 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.83 | <.001 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| Race (Ref: White) | ||||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.79 | <.001 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.88 | <.001 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Hispanic | 1.01 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 1.08 | 1.09 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.11 |

| Other | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.81 | 1.07 | 0.73 | <.001 | 0.70 | 0.75 |

| AD (versus other dementia) | 1.21 | <.001 | 1.14 | 1.28 | 1.19 | <.001 | 1.18 | 1.20 |

| Depression | 1.21 | <.001 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 1.30 | <.001 | 1.29 | 1.31 |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.52 | <.001 | 1.44 | 1.60 | 1.62 | <.001 | 1.61 | 1.64 |

| ABS (Ref: 0) | ||||||||

| Mild (1–2) | 1.95 | <.001 | 1.86 | 2.05 | 2.04 | <.001 | 2.02 | 2.06 |

| Moderate (3–5) | 2.81 | <.001 | 2.64 | 3.00 | 2.88 | <.001 | 2.84 | 2.92 |

| Severe (≥ 6) | 5.03 | <.001 | 4.49 | 5.62 | 3.79 | <.001 | 3.71 | 3.87 |

| CPS (Ref: none to mild, 0–2) | ||||||||

| Moderate to moderately severe (3–4) | 1.57 | <.001 | 1.50 | 1.64 | 1.73 | <.001 | 1.72 | 1.75 |

| Severe to very severe (5–6) | 1.19 | <.001 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 1.44 | <.001 | 1.42 | 1.46 |

| Years (Ref: 2001–2005) | ||||||||

| 2006–2008 | 1.01 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.92 | <.001 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| 2009–2010 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.82 | <.001 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| Metropolitan-area nursing home | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| Nursing Home’s State (Ref: California) | ||||||||

| Florida | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| Georgia | 1.06 | 0.24 | 0.96 | 1.18 | 1.14 | <.001 | 1.11 | 1.16 |

| Illinois | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.91 | <.001 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| Louisiana | 1.20 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 1.34 | 1.40 | <.001 | 1.37 | 1.44 |

| Massachusetts | 1.05 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 1.16 | 1.16 | <.001 | 1.13 | 1.18 |

| Maryland | 0.92 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 1.03 | 1.05 | <.001 | 1.02 | 1.08 |

| North Carolina | 0.86 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 1.04 | <.001 | 1.02 | 1.06 |

| New Jersey | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.97 | 1.01 |

| New York | 1.05 | 0.21 | 0.97 | 1.13 | 1.06 | <.001 | 1.04 | 1.08 |

| Ohio | 0.84 | <.001 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.78 | <.001 | 0.77 | 0.80 |

| Pennsylvania | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 1.01 |

| Texas | 1.14 | <.001 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 1.30 | <.001 | 1.27 | 1.32 |

| Virginia | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 1.06 |

| Constant | 0.82 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 2.35 | <.001 | 2.24 | 2.47 |

Note: the numbers in regression analysis are slightly different from those in Table 2, because some variables have missing values

HIV= human immunodeficiency virus; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; ref = Reference group; AD=Alzheimer’s disease; ABS = Aggressive Behavior Scale; CPS = Cognitive Performance Scale

Dementia was identified by using the resident assessment (MDS) diagnosis checkboxes of “Alzheimer’s Disease” and “Dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.”

The period following the first FDA Black Box warning (2006–2008 compared to 2001–2005) was associated with significantly lower odds of APS receipt for residents 65+ (AOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.92, 0.93), but not for younger residents. Being a resident in years 2009–2010 (compared to 2001–2005), the years after the extended Black Box warning, was significantly associated with lower APS receipt for both age groups; however, a larger 18% reduction in odds was observed for older residents (AOR 0.82; 95% CI 0.81, 0.83; Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This population-based comparative study of long-stay NH residents with and without HIV (in the 14 U.S. states accounting for 75% of HIV prevalence) 17,18,17,17 found that the proportion of HIV+ long-stay residents increased by 71% over a ten-year time period, from 0.7% in 2001 to 1.2% in 2010. The prevalence sample of (unduplicated) long-stay residents showed 6% of NH residents under 65 were HIV+ compared with 0.5% of those over 65. For residents with dementia, 35% of HIV+ residents were under 65 years of age compared to only 3% for HIV− residents. HIV+ residents had a higher prevalence of non-AD dementia and a lower prevalence of AD than did HIV− residents and these differences fluctuated by age. HIV+ dementia residents less than 65 had 24% greater odds of receiving an APS medication compared to their HIV− counterparts (AOR 1.24; 95% CI 1.15, 1.34), while older HIV residents had lower odds (AOR 0.82; 95% CI 0.77, 0.87). These findings are timely given the observed increase of HIV+ residents in NHs (and the expected continued increase);1 as such, they contribute to an evidence base needed to ensure high-quality care for younger and older HIV+ residents in NHs.

The higher prevalence of non-AD dementia for younger HIV+ residents likely reflects a greater prevalence of HIV-associated dementia. However, our data does not identify the type of “other dementia.” In addition, although there may be some misclassification, we believe the descriptive differences presented on the prevalence of AD and non-AD dementias by HIV status have much face validity. Notable is that our identified 56.7% prevalence of dementia in residents 65+ (in 2001–2010) is comparable to the 50.6% prevalence identified by the Centers for Disease Control in 2013–2014.7

Similar to a Canadian study,26 we observed greater APS use for HIV+ versus HIV− residents, though we found this only occurred for HIV+ residents <65 years of age. We speculate that it is possible that NHs have less familiarity caring for these younger HIV residents (99% of whom have non-AD dementia) leading to greater use of APS. While combined use of APS and ART is associated with adverse effects beyond those observed with APS or ART alone,16 we lacked data on ART use, limiting our ability to understand the frequency of combined use. Still, the study findings highlight the necessity to better prepare NHs and their staff for the expected increasing numbers of aging persons with HIV who will need NH care in the next decade.2, 27 Considering this, research aimed at understanding the characteristics of NHs with comparable (lower) APS use for HIV+ and HIV− residents is needed to assist in the development of interventions and to inform best practices. Also of interest is whether best practices and higher quality are associated with caring for higher volumes of HIV+ residents (whether “practice makes perfect”).28–30

As shown in other research31 and related to the above, we found significant differences in the odds of APS use by state. For example, compared to NH residents in California, those in Ohio had lower odds of APS use while those in Louisiana had higher odds. In addition, we found lower odds of APS for younger residents residing in metropolitan-area NHs. Given these findings and the above discussion, future research is recommended that examines how resident, NH and market (geographic) characteristics are associated with NH care for persons with HIV.

In agreement with a previous research,32 residents in NHs after the FDA’s initial “black box” APS warning generally had lower adjusted odds for APS use than NH residents in prior years). However, compared to NH residents in 2001–2005, we found greater effect sizes for years 2009–2010 (after the extended “black box” warning that included conventional APS) than we observed for years 2006–2008. While we cannot discount the possibility that this finding may reflect other efforts to reduce APS use in NHs,33 it suggests the 2009 FDA warning may have influenced APS prescribing among NH residents with dementia.

There are some study limitations. We were unable to provide a complete profile of long-stay residents with HIV since we lacked CD4 cell count, viral load and HIV treatment data. Also, our use of secondary data may limit the sensitivity and specificity of our dementia diagnoses, especially our attempt to differentiate types of dementia. In addition, we controlled for the severity of cognitive impairment using the CPS. The CPS is not a substitute for performance-based cognitive testing and for those with HIV it may be an insensitive measure of cognition function (as is its correlate, the Mini-Mental Status Exam)34 Also, while our findings suggest potential differential care, we cannot form conclusions on the appropriateness of APS prescribing without additional clinical data relating to the indication for APS use. Additionally, much of what is known about the safety and efficacy of APS in persons with HIV has been extrapolated from randomized clinical trials of APS use in elderly dementia patients - it may not be applicable to individuals (particularly younger persons) with HIV. Furthermore, the redaction by some states of HIV diagnoses on NH MDS assessments may have resulted in some under identification of HIV. However, multivariable findings were essentially the same when we included data from the eight states that did not redact HIV diagnoses. Last, given the complexities in accessing and analyzing MAX data this study reflects prevalence and care in years 2001–2010. Nonetheless, this study is the most current reflection of NH prevalence and care for HIV+ residents and the only one to our knowledge that compares persons with and without HIV in U.S. NHs.

CONCLUSION

Using population-based data on long-stay NH residents, this study contributes to our understanding of HIV in NHs. It also raises concern about potential differential quality of care for younger HIV+ residents with dementia. Given the aging of persons with HIV population in the U.S. and their increasingly likely need for NH care, study findings contribute evidence needed to ensure high-quality care for younger and older HIV+ NH residents.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. SELECTION of HIV-Medicaid Beneficiaries. Base sample of Medicaid beneficiaries likely living with HIV in 14 states, 2001–2010

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sponsor’s Role: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (#R01MH102202). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report. Dr. Wilson is partially supported by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853) and by Institutional Development Award Number U54GM115677 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds Advance Clinical and Translational Research (Advance-CTR) from the Rhode Island IDeA-CTR award (U54GM115677).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Miller, Cai, Daiello and Wilson have no possible conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among People Aged 50 and Over [On-line]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Accessed February 23, 2018

- 2.Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2010;7:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Huang C. Analyses of nursing home residents with human immunodeficiency virus and depression using the minimum data set. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2002;16:441–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Huang C. Profiles of nursing home residents with HIV. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2002;13:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Huang C. Analyses of nursing home residents with HIV and dementia using the minimum data set. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001;26 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selwyn PA, Goulet JL, Molde S et al. HIV as a chronic disease: implications for long-term care at an AIDS- dedicated skilled nursing facility. J Urban Health 2000;77:187–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-Term Care Providers and services users in the United States: data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 3 2016:x–xii; 1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker JT, Kingsley LA, Molsberry S et al. Cohort Profile: Recruitment cohorts in the neuropsychological substudy of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1506–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelman BB. Neuropathology of HAND With Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy: Encephalitis and Neurodegeneration Reconsidered. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol 2012;3:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margallo-Lana M, Swann A, O’Brien J et al. Prevalence and pharmacological management of behavioural and psychological symptoms amongst dementia sufferers living in care environments. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:900–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estabrooks CA, Knopp-Sihota JA, Norton PG. Practice sensitive quality indicators in RAI-MDS 2.0 nursing home data. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Potentially Inappropriate Use of Antipsychotics in Long-Term Care [On-line]. http://indicatorlibrary.cihi.ca/display/HSPIL/Potentially+Inappropriate+Use+of+Antipsychotics+in+Long-Term+Care. Accessed February 23, 2018

- 15.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Information for Healthcare Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics [On-line]. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Accessed February 24, 2018

- 16.Ferrara M, Umlauf A, Sanders C et al. The concomitant use of second-generation antipsychotics and long-term antiretroviral therapy may be associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Psychiatry Res 2014;218:201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2010; vol 22 In. Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDS 2.0 for Nursing Homes: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [On-line]. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIMDS20.html. Accessed February 24, 2018

- 19.Mor V, Angelelli J, Jones R, Roy J, Moore T, Morris J. Inter-rater reliability of nursing home quality indicators in the U.S. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Fries BE, Murphy K, Mor V. Development of the nursing home Resident Assessment Instrument in the USA. Age Ageing 1997;26 Suppl 2:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor V, Intrator O, Unruh MA, Cai S. Temporal and Geographic variation in the validity and internal consistency of the Nursing Home Resident Assessment Minimum Data Set 2.0. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse [On-line] https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/home. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 23.Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, et al. Diagnostic data for neurological conditions in interRAI assessments in home care, nursing home and mental health care settings: a validity study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, Koch GG, Mitchell CM, Phillips CD. Validation of the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale: agreement with the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50:M128–M133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2298–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Lemick R, Tai JW. Comparing the characteristics of people living with and without HIV in long-term care and home care in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care 2015;27:1343–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60 Suppl 1:S1–S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett CL, Adams J, Gertler P et al. Relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS-related Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: experience from 3,126 cases in New York City in 1987. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1992;5:856–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogg RS, Raboud J, Bigham M, Montaner JS, O’Shaughnessy M, Schechter MT. Relation between hospital HIV/AIDS caseload and mortality among persons with HIV/AIDS in Canada. Clin Invest Med 1998;21:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wenger NS et al. Specialty training and specialization among physicians who treat HIV/AIDS in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T, Peterson D, Gurwitz JH. Antipsychotic use among nursing home residents. JAMA. 2013;309:440–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorsey ER, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, Conti RM, Alexander GC. Impact of FDA black box advisory on antipsychotic medication use. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes Antipsychotic Drug use in Nursing Homes Trend Update [On-line]. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/2014-10-27-Trends.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2018

- 34.Skinner S, Adewale AJ, DeBlock L, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurocognitive screening tools in HIV/AIDS: comparative performance among patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2009;10: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. SELECTION of HIV-Medicaid Beneficiaries. Base sample of Medicaid beneficiaries likely living with HIV in 14 states, 2001–2010