Abstract

Endothelial surface and circulating glycoprotein von Willebrand factor (vWF) regulates platelet adhesion and is associated with thrombotic diseases, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease. Thrombosis, as manifested in these diseases, is the leading cause of disability and death in the western world. Current parenteral antithrombotic and thrombolytic agents used to treat these conditions are limited by a short therapeutic window, irreversibility, and major risk of hemorrhage. To overcome these limitations, we developed a novel anti-vWF aptamer, called DTRI-031, that selectively binds and inhibits vWF-mediated platelet adhesion and arterial thrombosis while enabling rapid reversal of this antiplatelet activity by an antidote oligonucleotide (AO). Aptamer DTRI-031 exerts dose-dependent inhibition of platelet aggregation and thrombosis in whole blood and mice, respectively. Moreover, DTRI-031 can achieve potent vascular recanalization of platelet-rich thrombotic occlusions in murine and canine carotid arteries. Finally, DTRI-031 activity is rapidly (<5 min) and completely reversed by AO administration in a murine saphenous vein hemorrhage model, and murine toxicology studies indicate the aptamer is well tolerated. These findings suggest that targeting vWF with an antidote-controllable aptamer potentially represents an effective and safer treatment for thrombosis patients having platelet-rich arterial occlusions in the brain, heart, or periphery.

Keywords: thrombosis, stroke, aptamer, platelet, antithrombotic

An aptamer targeting von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a potent and rapidly reversible antiplatelet agent. The aptamer, termed DTRI-031, can prevent thrombosis in mice following vascular injury, and it can recanalize vessels occluded by thrombi in mice and dogs. An antidote oligonucleotide can rapidly restore normal platelet function and hemostasis.

Introduction

Thrombosis, as seen in ischemic stroke, cardiovascular disease, carotid artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease, is the leading cause of death and a leading cause of major disability worldwide.1 The main therapeutic agent that has been used to treat occlusive thrombosis is recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA), which is approved for both acute coronary thrombosis2 and ischemic stroke.3 Unfortunately, rTPA is limited by several critical factors. First, the inability to reverse rTPA activity results in a significant risk of hemorrhage. Second, in the setting of ischemic stroke, the short therapeutic window for rTPA renders more than 90% of stroke patients ineligible for therapy.4 Finally, rTPA only achieves approximately 30% recanalization, and re-occlusion commonly occurs after primary thrombolysis, resulting in the loss of initial improvement.

von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a glycoprotein involved in a seminal event of platelet plug formation. vWF interacts with glycoprotein Ib-alpha (gpIba) on the platelet surface to induce platelet adhesion to the vessel wall. This initial binding event is the primary non-redundant step in platelet aggregation and represents the beginning of platelet aggregation.5 Following this event, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (gpIIb/IIIa) becomes activated and binds to fibrinogen, resulting in thrombus formation. von Willebrand disease (vWD) can be both a qualitative and quantitative reduction of vWF. Type I vWD, the predominant form of vWF disease, presents most commonly with menorrhagia in women, and otherwise heavier than usual bleeding in patients undergoing dental procedures.6 These patients do not present with spontaneous hemorrhage. Moreover, vWD type I patients are protected from cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events.7 Inhibition of vWF therefore represents an attractive target in arterial thrombosis, and it may be superior to current therapies. Moreover, as rTPA is thought to be less effective at lysing platelet-rich clots,8, 9, 10 a major unmet medical need exists for novel therapeutic agents that can restore blood flow to arteries blocked by such platelet-rich occlusions.

gpIIb/IIIa is expressed on the surface of platelets and facilitates platelet aggregation by binding to fibrinogen. The three gpIIb/IIIa inhibitors available clinically to treat acute thrombosis are Abciximab, Eptifibatide, and Tirofiban. These agents significantly improved outcomes in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).11 When tested in acute ischemic stroke, however, they resulted in a significant increase in intracranial hemorrhage without improvement in morbidity or mortality.12 This significant increase in hemorrhage has encouraged us and others to explore the development of novel antiplatelet agents for the treatment of ischemic stroke that can be controlled if bleeding occurs.13

Aptamers are single-stranded oligonucleotides that have theoretical advantages over other classes of therapeutic agents. They bind to their target with high affinity, in the low nanomolar to high picomolar region, similar to monoclonal antibodies.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 They can be chemically modified to customize their bioavailability, chemically synthesized in large scale, and, most pertinent to our application, they can be rapidly reversed.19, 20, 21, 22 Previous studies by our group demonstrated that antidote-controlled aptamer inhibition of coagulation factor IXa (FIXa) is an effective rapid-onset yet rapidly reversible anticoagulant in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.23 However, no antiplatelet aptamer-antidote pair has progressed into the clinic.

Here we describe the preclinical development and testing of a vWF aptamer-antidote pair that reversibly blocks platelet adhesion and function. The aptamer, DTRI-031, is able to prevent platelet-rich thrombus formation in a murine carotid injury model. Based on the role of vWF in thrombus remodeling and stabilization, we also investigated the effect of DTRI-031 to restore blood flow following arterial occlusion, a first for any aptamer-based agent. Finally, an antidote oligonucleotide, specifically designed to inhibit DTRI-031, was created and tested to determine if the antiplatelet activity of the aptamer could be rapidly controlled if bleeding occurs. This aptamer-antidote pair represents a novel, rapid-onset and rapidly reversible antiplatelet agent that may prove valuable for the treatment of acute thrombotic events in the heart, brain, and peripheral vasculature.

Results

Optimized vWF Aptamer Binds and Inhibits vWF Activity In Vitro and Ex Vivo

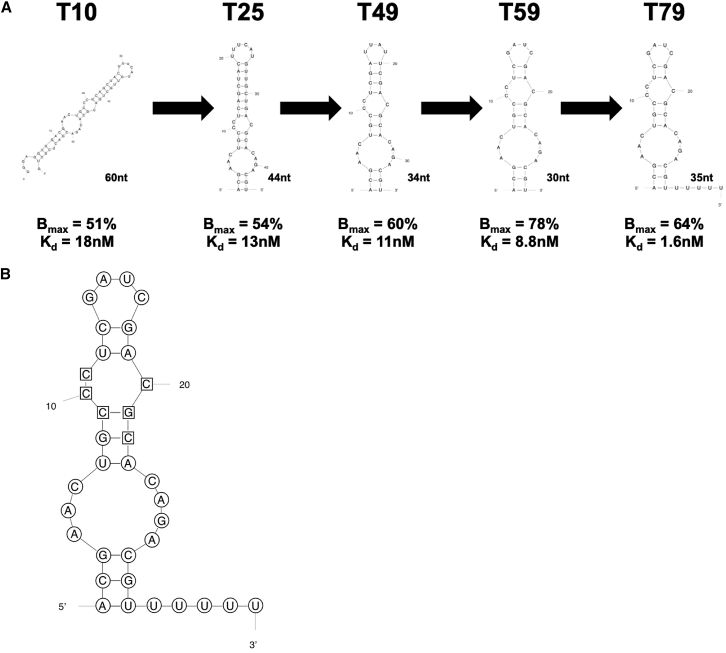

To create a vWF aptamer that would be amenable to large-scale chemical synthesis for use in large animals and the clinic, we designed and tested a series of vWF aptamer derivatives derived from the 2′Fluoro-pyrimidine-modified RNA aptamer 9.14T10 (Figure 1A).24, 25 Each truncate was evaluated for binding affinity by radiolabeling the 5′ end of the aptamer and using a double-filter nitrocellulose filter-binding assay to determine the dissociation constant (KD) and binding max (Bmax) of individual aptamers. The aptamer variants that bound with the highest affinities were evaluated for their ability to inhibit vWF activity under high shear stress in a whole-blood platelet function analysis (PFA), called a Platelet Function Analyzer-100 (PFA-100). This effort resulted in a vWF aptamer that is 30 nt long (T59) that retains high affinity.

Figure 1.

DTRI-031 Truncation and Optimization Summary

(A) The original vWF9.14T10 aptamer was initially truncated through progressive deletion of nucleotides from both the 3′ and 5′ ends. This shortening was followed by systematic deletions in stems and loops as predicated from secondary structure. It was found that the aptamer could be truncated from 60 to 30 nt without a reduction in its ability to bind to vWF. vWF aptamer T79 is T59 with 5 uracil nt added at the 3′ end to allow for antidote oligonucleotide binding. (B) Secondary structure of DTRI-031 with nucleotides highlighted in circles containing 2′OMe modifications and those in squares containing 2′F modifications.

To facilitate antidote oligonucleotide (AO) binding to the aptamer to reverse its activity, we added 5 uracil nt to the 3′ end of the aptamer to allow for rapid AO nucleation, resulting in an aptamer variant called 9.14T79 that binds to vWF with a KD = 1.6 nM and Bmax = 64% (Figure 1A). Next, to improve nuclease resistance for in vivo applications, we systematically performed chemical substitutions and identified a fully modified version of the aptamer that contains 2′ O-methyl moieties at every 2′OH-purine position except one, which can be replaced with a 2′F, resulting in an aptamer variant that does not contain any 2′OHs (Figure 1B). Almost 90 truncates were synthetized and tested in vitro. The fully truncated and stabilized aptamer, named DTRI-031, binds to vWF with a KD = 11 nM and a Bmax = 56%, which is similar to the 60-nt-long starting aptamer 9.14, which binds vWF with a KD = 18 nM and Bmax = 51% (Figure 1B).

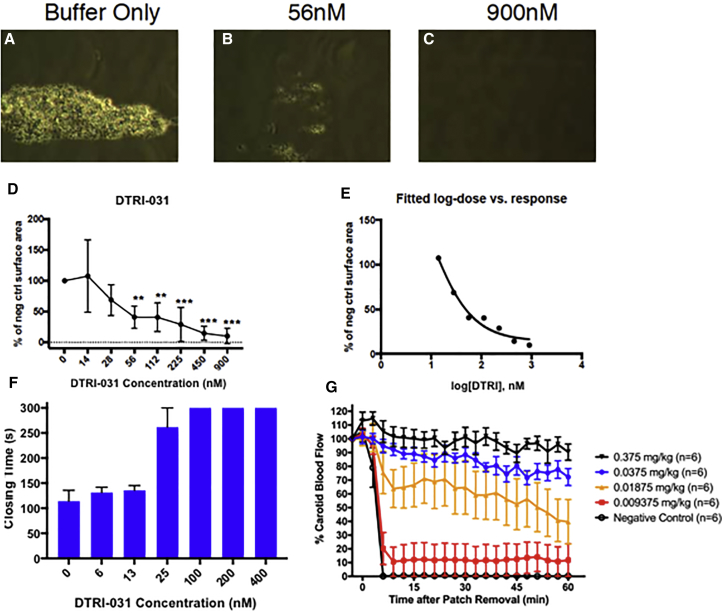

To evaluate the effect of DTRI-031 on platelet adhesion, human whole-blood samples were treated with aptamer starting at 900 nM with 2-fold dilutions to 14 nM and tested on the Venaflux, which measures platelet adhesion under high shear stress. Platelets bound to the collagen surface were measured as a percentage of control. DTRI-031 prevented platelet adhesion to the collagen surface in a dose-dependent manner compared to buffer alone (Figure 2). Near complete inhibition of platelet adhesion was achieved at doses from 225 to 900 nM and intermediate inhibition at doses from 56 to 112 nM (Figures 2B and 2C), with no inhibition in buffer control samples (Figure 2A). Log-dose versus response data fitting resulted in a logIC50 calculation of 1.9 (72.6 nM) (Figures 2D and 2E).

Figure 2.

DTRI-031 Inhibits Platelet Adhesion under High Shear, Inhibits Platelet Aggregation in Whole Blood, and Prevents Thrombosis In Vivo

DTRI-031 prevented human platelet adhesion to a collagen surface in a Venaflux system in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Buffer control demonstrated 100% platelet adhesion. Aptamer activity was measured as a percentage of the control. (B) 56 nM DTRI-031 demonstrated approximately 50% platelet adhesion in this assay while (C) 900 nM demonstrated complete inhibition (n = 3 per group). (D) DTRI-031 inhibited platelet adhesion in a dose-dependent manner, with significant inhibition at doses between 56 and 900 nM (p < 0.05) (n = 3 per group). (E) A non-linear regression analysis of the dose-response curve determined the logIC50 of the aptamer was 1.86 (72.5 nM). (F) A whole-blood Platelet Function Analyzer-100 (PFA-100) assay demonstrated that the optimized aptamer can completely inhibit platelet aggregation. Doses between 100 and 400 nM exceeded the upper limit of the assay, and 25 nM demonstrated significant platelet aggregation inhibition compared to control (p < 0.01) (n = 4 per group). (G) After intubation and sedation, the right carotid artery was exposed and the left jugular vein was catheterized. Doses from 0.009375 to 3 mg/kg were administered, followed by ferric chloride-induced carotid artery injury. The lowest dose at which there remained 100% patency was 0.0375 mg/kg. For 0.375 and 0.0375 mg/kg, p < 0.0001 for all times from 6 to 60 min versus the no aptamer group (n = 6 per group), using two-way repeated ANOVAs with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post test. Error bars represent mean ± SEM.

The effect of DTRI-031 on platelet aggregation under physiological shear was then measured ex vivo in a PFA-100 human whole-blood assay. The aptamer was mixed with freshly drawn whole blood and incubated for 5 min before being added to the collagen/ADP cartridges. This clinical PFA generates a platelet-induced closing time where baseline values for normal human blood are between 60 and 120 s. Aptamer DTRI-031 completely inhibited platelet aggregation in this system at doses over 100 nM, where platelet plug formation and closing time exceeded 300 s, representing the upper limit of the assay (Figure 2F). Thus, DTRI-031 can prevent both platelet adhesion and aggregation ex vivo.

Aptamer DTRI-031 Prevents Platelet-Rich Thrombosis In Vivo

To assess the effectiveness of the aptamer as an antithrombotic agent, we administered DTRI-031 over a range of doses in a murine carotid artery injury thrombosis model.24 This model was chosen because the arterial clots formed are known to be platelet rich.8 The primary endpoint of this animal model is to assess the ability of an agent to maintain the patency of a vessel after endothelial damage by preventing thrombosis. After intubation and sedation, the right carotid artery and left jugular vein were exposed through a midline incision. A flow probe was placed around the carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein was cannulated for intravenous (i.v.) drug administration. To damage the vessel, Whatman paper soaked in ferric chloride was applied for 3 min to the carotid artery immediately upstream of the flow probe.

As shown in Figure 2G, administration of 0.0375 mg/kg or greater of DTRI-031 to mice prior to vessel injury resulted in maintaining greater than 70% patency of the damaged carotid artery (n = 6 per group) throughout the 60-min observation period. At a dose of 0.01875 mg/kg, a significant difference in patency of the vessel was still observed compared to 0.0375 mg/kg (p = 0.007, Student’s t test). Damaged vessels in all animals treated with less aptamer (0.009375 mg/kg) or no aptamer (negative control) occluded in only a few minutes (n = 6 per group). Thus, vWF aptamer DTRI-031 is a potent antithrombotic agent in mice.

Aptamer DTRI-031 Can Restore Blood Flow following Carotid Artery Vessel Occlusion

Once we determined that DTRI-031 could prevent occlusive clot formation, we then sought to determine if it could also restore blood flow through an artery containing a platelet-rich occlusive clot. Therefore, a murine model of carotid artery occlusion was used to evaluate the ability of the aptamer to recanalize a vessel. After intubation and sedation, the right carotid artery and left internal jugular vein were exposed. The vein was then catheterized for drug administration. Whatman paper soaked in 10% ferric chloride was applied to the carotid artery for 3 min and removed. Once total vessel occlusion had been verified by the cessation of blood flow, the platelet-rich occlusive thrombus was left to stabilize for an additional 20 min, and then aptamer or rTPA was administered. The dose of rTPA used in this experiment was 10 mg/kg, 11-fold higher than 0.9 mg/kg (the dose used to treat humans who present with ischemic strokes within 3–4.5 h of last known well), because this was the dose reported to be effective for recanalization in murine models of arterial thrombosis.26

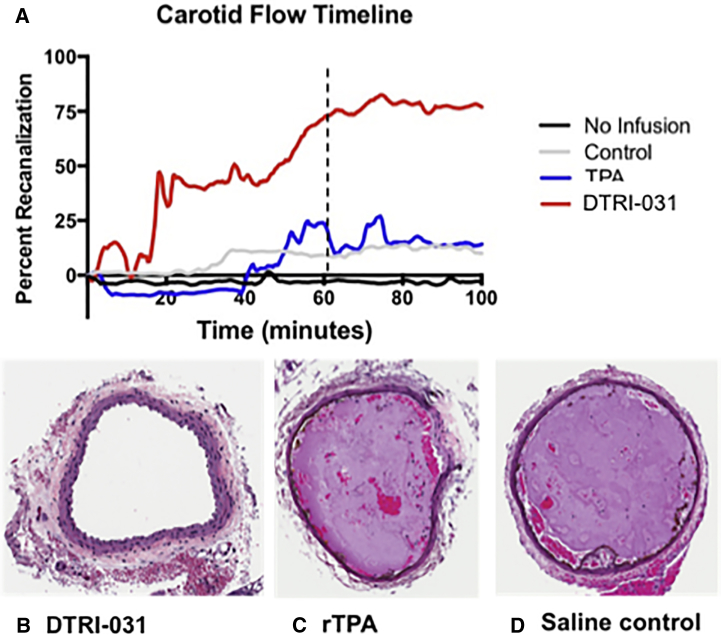

Aptamer DTRI-031 was dosed at 0.5 mg/kg and, as shown in Figure 3A, demonstrated significantly higher recanalization compared to rTPA (p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA) and buffer control (p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA) (n = 8 per group). Histological analysis of the carotid arteries from each group grossly correlated with the degree of recanalization measured by the flow probe (Figure 3). Examination of the cross-sections of the affected carotid artery of the buffer control group demonstrated complete occlusion in all animals (n = 8) (Figure 3D). Consistent with only modest recanalization, vessel sections from the rTPA-treated mice contained platelet-rich thrombi that largely occluded the vessels (n = 8) (Figure 3C). Finally, the histology of the carotid artery section of DTRI-031-treated mice demonstrated complete patency in 6 of the samples and only evidence of a small clot remaining in a section of two of the previously occluded vessels (n = 8) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

DTRI-031 Demonstrates Superior Vessel Recanalization following Murine Carotid Artery Occlusion Compared to rTPA

(A) DTRI-031-treated animals, at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (n = 8), demonstrated superior thrombolysis compared to both rTPA-treated animals, at a dose of 10 mg/kg (p < 0.05) (n = 8), and saline control animals (p < 0.01) (n = 8). Histopathology of mouse carotid arteries demonstrated that (B) DTRI-031-treated animals had patent vessels free of occlusive thrombus compared to (C) rTPA and (D) saline control animals (n = 8 per group).

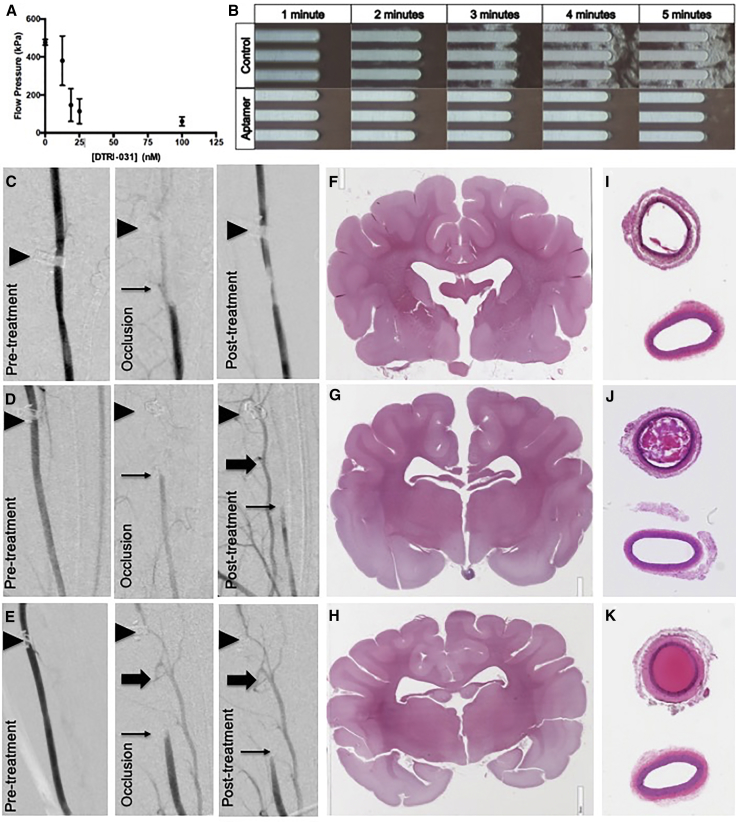

Aptamer DTRI-031 Demonstrates Dose-Dependent Platelet Inhibition of Canine Whole Blood

To further evaluate DTRI-031 activity during platelet-containing thrombus formation under high shear and begin to assess the aptamer in a large animal model, we tested the vWF aptamer in a Total Thrombus-formation Analysis System (T-TAS) (Fujimori Kogyo, Yokohama, Japan), a whole-blood sampling system that measures blood flow as a function of the pressure in kilopascals (kPa) across a collagen-coated capillary system at a constant rate of 14 μL/min.27 Previous studies have shown that this assay is sensitive in detecting platelet dysfunction in patients with vWD.28 Canine whole blood was collected in hirudin-coated tubes followed by the addition of DTRI-031. The collection tube was then inserted into the T-TAS system. While usually a two-chamber system, this unit has a camera allowing real-time observation of platelet adhesion to the collagen capillary tubes and aggregation along the membrane.

Aptamer DTRI-031 inhibited canine platelet aggregation and maintained blood flow pressure at doses between 18.75 and 100 nM (Figure 4A) (p < 0.05 compared to buffer control, two-way ANOVA) (n = 5 per group). Visualization of the platelets across the membrane demonstrated complete inhibition of both platelet adhesion and aggregation, compared to buffer control, when DTRI-031 was dosed at 100 nM (Figure 4B). Each picture represents the first 10 s of minutes 1 through 5. The areas of white haze seen from minutes 3 to 5 in the buffer control panel are platelets adhering to the horizontal capillary channel; as the channels occlude after 3 min, further platelet aggregation occurs. The aptamer treatment panel shows no such platelet accumulation, indicating that the DTRI-031 is a potent inhibitor of canine platelet function under sheer stress in vitro.

Figure 4.

vWF Aptamer Prevents Platelet Adhesion and Aggregation in Total Thrombus-Formation Analysis System in Canine Whole Blood, Recanalizes Carotid Artery Occlusion in Canines, and Demonstrates No Brain Hemorrhage or Embolization

(A) Canine whole blood incubated with or without vWF aptamer DTRI-031 at doses of 12.5, 18.75, 25, and 100 nM compared to negative saline control (p < 0.05) (n = 5 per group) and analyzed for flow via T-TAS. (B) Still images of whole blood flowing over collagen tubules in the T-TAS. The cloudy patches seen in the control group are aggregated platelets, while the aptamer sample contains DTRI-031 at a dose of 100 nM. (C–K) Carotid artery occlusion (thin arrow) was initiated by applying a 50% ferric chloride patch, and vessel occlusion was monitored with a flow probe and verified by angiography. After 45 min of occlusion, (C) intravenous aptamer administration resulted in recanalization in 4/7 dogs tested compared to (D) rTPA and (E) saline control, where no recanalization occurred (p = 0.02) (n = 7 per group). In both (D) and (E), persistent occlusion of the carotid artery (thin arrow) resulted in reflux opacification of the vertebral artery (thick arrow). Position of flow probe is indicated (black triangle). (F) Brain histology by H&E staining demonstrated that DTRI-031 did not cause intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral thromboembolism compared to (G) rTPA and (H) saline control (n = 7 per group). Carotid artery histology by H&E staining verified recanalization of the occluded segment in (I) DTRI-031-treated dog compared to (J) rTPA and (K) saline control dogs (n = 7 per group). Note the lower fully patent vessel shown in each section is the contralateral carotid that was not damaged.

Aptamer DTRI-031 Demonstrates Recanalization in a Canine Model of Carotid Occlusion

A canine model of cerebrovascular thrombotic disease was used to evaluate the aptamer in a large, clinically relevant animal model of vessel occlusion, similar to that of large vessel occlusion in stroke. Adult beagles were intubated and sedated. The right femoral artery and vein were catheterized. The right carotid artery was exposed and a flow probe was placed distal to the area of injury. A patch saturated in 50% ferric chloride was applied to the carotid artery just proximal to the flow probe, left in place for 15 min, and then removed. Arterial occlusion was indicated by the flow probe and verified by digital subtraction angiography of the carotid artery (Figures 4C–4E). After 45 min of occlusion and platelet-rich clot stabilization, animals received one of 3 agents: (1) intravenous injection of 0.5 mg/kg DTRI-031 as a bolus, (2) intravenous injection of 0.9 mg/kg rTPA by the standard clinical protocol of 10% injection and then the other 90% infused over 45 min, or (3) intravenous injection of saline.

In Figures 4C–4E, the left panel shows patency of the vessel prior to damage. The middle panel shows vessel occlusion following its damage and platelet-rich clot formation, prior to aptamer administration, as detected by the downstream flow probe. The third panel evaluates whether blood flow has recovered and if the vessel is recanalized and corresponds to what is seen on the distal flow probe in these dogs. The carotid arteries of 4 of 7 dogs that received DTRI-031 recanalized between 5 and 15 min after administration (Figure 4C). By contrast, animals treated with rTPA or saline control demonstrated no recanalization after treatment (Figures 4D and 4E) (p = 0.02) (n = 7 per group, z-test).

To begin to determine the safety of the DTRI-031, we evaluated bleeding and clotting in the brains of these dogs. Aptamer administration did not induce intracranial hemorrhage nor did carotid artery recanalization result in cerebral thromboemboli by H&E staining in any of the animals (Figure 4F). The brain histology from both the DTRI-031 and rTPA groups is unremarkable and identical to the control saline-treated group (Figures 4F–4H). The lack of cerebral thromboembolism in the aptamer group was reassuring, as the carotid artery histology demonstrated essentially complete recanalization of the vessel in all 4 aptamer-treated animals that revascularized on angiography (Figure 4I). The top carotid section is through the area of vessel damage where occlusion occurred, while the bottom section is from the patent portion adjacent to the diagnostic catheter. By sharp contrast, both the rTPA- and saline-treated control groups of animals contained thrombi that continued to occlude the damaged carotids, consistent with the inability of these approaches to restore blood flow (Figures 4J and 4K, respectively).

An AO Can Rapidly Reverse the Antiplatelet Activity of Aptamer DTRI-031 In Vitro and In Vivo, and DTRI-031 Is Well Tolerated in Mice

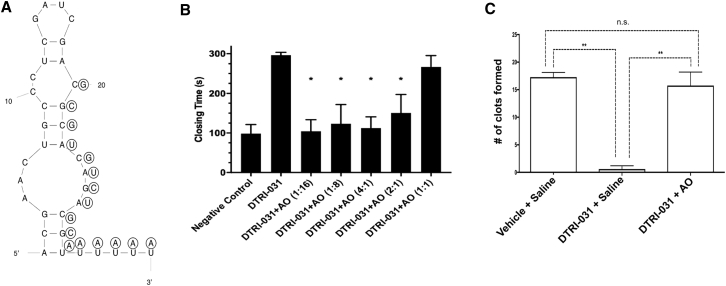

To develop a robust yet safe anti-vWF aptamer, we sought to create an AO to reverse the aptamer’s antiplatelet activity if needed. None of the antidotes initially tested could reverse the 30-nt aptamer T59, likely because they could not readily access a nucleation site on the aptamer once it was tightly bound to vWF. Therefore, we added a 5-nt uracil (oligo-U tail) to the 3′ end of the molecule as an artificial nucleation site, and we tested a 16-nt antidote complementary to this tail and the 3′ end of the aptamer (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, this AO reversed the aptamer’s antiplatelet activity in vitro in a PFA-100 assay within 2 min, at a molar ratio as low as 2:1 over the aptamer.

Figure 5.

Antidote Oligonucleotide Reverses Aptamer Ex Vivo and in a Murine Saphenous Vein-Bleeding Model

(A) Secondary structure of DTRI-031 with 2′OMe antidote oligonucleotide (AO) shown in circles. (B) Assessing the ability of the AO to reverse DTRI-031 antiplatelet activity in a PFA-100 whole-blood assay. The aptamer (125 nM) was incubated with AO at the ratios indicated for 2 min, and a 2-fold excess of the AO was observed to totally reverse the aptamer’s activity (n = 4 per group). (C) The antidote oligonucleotide rapidly reverses DTRI-031 activity in vivo following saphenous vein injury. The data are represented as a bar graph of clots formed after the administration of DTRI-031 and either no antidote (saline) or the antidote oligonucleotide (AO). All animals were initially treated with either vehicle or the DTRI-031 aptamer (dose 0.375 mg/kg) in the murine saphenous vein-bleeding model. The vehicle group stopped bleeding 17 ± 1 times over 15 min (n = 7). The DTRI-031 group given no antidote continued to bleed and demonstrated almost no clot development to control hemorrhage, which was in sharp contrast to the vehicle group (n = 5). Adding AO after DTRI-031 aptamer administration, measuring clot formation 5 min later resulted in a complete reversal of bleeding, with 16 ± 2 clots formed in 15 min, which was similar to animals that never received the aptamer (n = 8). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KS test) was used for each comparison: column A versus B, p < 0.01; column A versus C, p = not significant (ns); and column B versus C, p < 0.01. AO administered alone did not result in an increased number of clots formed compared to controls (data not shown) (statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Next, the ability of the AO to reverse the antiplatelet aptamer was evaluated in a murine saphenous vein-bleeding model.29 Here the saphenous vein is exposed and nicked by a 23G needle, and the number of times the damaged vessel stops bleeding over 15 min is assessed by disrupting clots as soon as they form. Fewer disruptions are consistent with reduced clotting and increased bleeding.29 The vehicle group demonstrated approximately 17 ± 1 clots (n = 7). Aptamer DTRI-031 was administered at a dose of 0.375 mg/kg and resulted in almost no clotting, which was highly significant compared to vehicle-treated animals (p < 0.0001, Student’s t test) (n = 5). However, aptamer DTRI-031 administration followed by AO addition demonstrated approximately 16 ± 2 clots, which was similar to animals that never received the aptamer (Figure 5C) (n = 8). Administration of antidote alone did not result in an increased or decreased number of clots. Thus, the antidote can rapidly reverse bleeding associated with DTRI-031-mediated inhibition of vWF.

Finally, to begin to assess the toxicology of DTRI-031, we dosed male and female mice with 300 mg/kg DTRI-031 (n = 6) by intravenous administration, and we monitored animals using complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) analyses. A 3-part CBC differential was evaluated both pre- and post-injection with DTRI-031. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, no significant changes were observed in either CBC or CMP, even in animals treated with doses that were 8,000 times higher than required to limit thrombosis (0.0375 mg/kg; Figure 2G) in a damaged artery. In addition, all treated animals continued to gain weight and were observed as bright, alert, and responsive throughout the study period. Gross necropsy was performed for individual animals from each time point. No signs of ascites, pleural effusion, hemorrhage, or other significant findings were observed. Thus, DTRI-031 appears to be well tolerated in mice at super-therapeutic levels.

Table 1.

Complete Blood Count Results from Mice Dosed with DTRI-031 (300 mg/kg) by Bolus i.v. Injection

| DTRI-031 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE |

Vehicle |

Day 1 |

Day 4 |

Day 8 |

|||

| Units | Normal Range | n = 23 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 6 | |

| WBC | 103/μL | 2.6–10.1 | 6.9 ± 2.8 | 7.7 ± 2.6 | 9.6 ± 4.4 | 9.2 ± 2.6 | 7.5 ± 3.2 |

| LYM | 103/μL | 1.3–8.4 | 5.0 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 7.5 ± 2.3 | 6.0 ± 2.4 |

| MONO | 103/μL | 0.0–0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| GRAN | 103/μL | 0.4–2.0 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| LYM | % | 75.5 ± 10.0 | 76.6 ± 4.0 | 71.2 ± 6.5 | 81.3 ± 4.5 | 81.2 ± 4.8 | |

| MONO | % | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | |

| GRAN | % | 17.7 ± 3.5 | 15.7 ± 3.2 | 22.6 ± 6.0 | 13.5 ± 3.8 | 14.0 ± 4.0 | |

| HCT | % | 32.8–48.0 | 50.7 ± 3.2 | 48.9 ± 2.9 | 48.5 ± 2.1 | 48.8 ± 7.4 | 48.5 ± 4.2 |

| MCV | fl | 42.3–55.9 | 43.5 ± 1.0 | 43.1 ± 1.0 | 43.7 ± 0.6 | 43.9 ± 1.2 | 43.4 ± 0.9 |

| RDWa | fl | 0.0–99.9 | 28.4 ± 1.1 | 27.9 ± 0.8 | 28.6 ± 0.4 | 29.8 ± 1.9 | 28.4 ± 0.7 |

| RDW | % | 0.0–99.9 | 22.5 ± 0.3 | 22.5 ± 0.4 | 22.7 ± 0.4 | 23.4 ± 0.7 | 22.7 ± 0.5 |

| HGB | g/dL | 10.0–16.1 | 17.8 ± 1.0 | 17.3 ± 1.1 | 17.0 ± 0.8 | 17.3 ± 2.7 | 17.0 ± 1.5 |

| MCHC | g/dL | 29.5–35.1 | 35.2 ± 0.6 | 35.4 ± 0.2 | 35.0 ± 0.4 | 35.3 ± 0.2 | 35.0 ± 0.6 |

| MCH | pg | 13.7–18.1 | 15.3 ± 0.3 | 15.2 ± 0.4 | 15.2 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 0.4 | 15.2 ± 0.1 |

| RBC | 106/μL | 6.50–10.10 | 11.66 ± 0.67 | 11.36 ± 0.82 | 11.09 ± 0.53 | 11.13 ± 1.96 | 11.18 ± 1.11 |

| PLT | 103/μL | 250–1,540 | 252 ± 68 | 264 ± 78 | 284 ± 71 | 244 ± 86 | 251 ± 65 |

| MPV | fl | 0.0–99.9 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 |

WBC, white blood cell; LYM, lymphocyte; MONO, monocyte; GRAN, granulocyte; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean cell volume; RDWa, red cell distribution width; HGB, hemoglobin; MCHC, mean cell hemoglobin concentration; MCH, mean cell hemoglobin; RBC, red blood cell; PLT, platelet; MPV, mean platelet volume.

Table 2.

Comprehensive Metabolic Panel Results from Mice Dosed with DTRI-031 (300 mg/kg) by Bolus i.v. Injection

| DTRI-031 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle |

Day 1 |

Day 4 |

Day 8 |

|||

| Units | Normal Range | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 6 | |

| BUN | mg/dL | 20.0–88.0 | 25.4 ± 2.0 | 32.2 ± 22.0 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 28.2 ± 2.7 |

| Creatinine | mg/dL | 0.5–1.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| BUN/Creat ratio | 108.9 ± 28.7 | 95.2 ± 29.0 | 114.2 ± 29.2 | 126.1 ± 30.5 | ||

| Phosphorous | mg/dL | 5.6–9.2 | 13.0 ± 1.6 | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 12.0 ± 2.5 | 10.7 ± 3.4 |

| Calcium | mg/dL | 7.9–10.5 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 9.7 ± 1.3 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 9.3 ± 0.4 |

| Total protein | g/dL | 4.5–6.0 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.2 |

| Albumin | g/dL | 3.0–4.0 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| Globulin | g/dL | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | |

| Alb/Glob ratio | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ||

| Glucose | mg/dL | 190–280 | 264 ± 25 | 191 ± 43 | 262 ± 53 | 284 ± 25 |

| Cholesterol | mg/dL | 0–0 | 72 ± 15 | 76 ± 18 | 60 ± 10 | 69 ± 14 |

| ALT (GPT) | U/L | 10–89 | 25 ± 5 | 40 ± 11 | 22 ± 3 | 34 ± 18 |

| ALP | U/L | 0–185 | 108 ± 13 | 112 ± 15 | 103 ± 13 | 112 ± 15 |

| GGT | U/L | 0–0 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Total bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.2–0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Creat, creatinine; Alb, albumin; Glob, globulin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GPT, glutamate oyruvate transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Discussion

These results indicate that vWF aptamer DTRI-031 is a potent antiplatelet agent in vitro, in a murine model of arterial thrombosis as well as in small and large animal models of recanalization of platelet-rich occluded vessels. In vivo evaluation of aptamer DTRI-031 demonstrated robust prevention of platelet-rich thrombus formation in mice. Dose-response experiments demonstrated that, following carotid injury, the aptamer can maintain arterial patency and blood flow transit time greater than 70% at a dose as low as 0.0375 mg/kg and that the aptamer is well tolerated in healthy mice at doses up to 300 mg/kg. Moreover, administration of the AO can reverse aptamer activity and restore platelet function and hemostasis in less than 5 min, which represents a major safety advance for an antiplatelet agent.

In comparison to both negative control and intravenous rTPA, DTRI-031 demonstrated superior recanalization of occluded murine carotid arteries containing platelet-rich clots at doses of 0.5 mg/kg. Currently, 0.9 mg/kg rTPA is used to treat patients who present with ischemic stroke and meet inclusion criteria. The dose of intravenous rTPA used in this mouse model was 11-fold higher than is used clinically, because that is the dose required to achieve thrombolysis in murine arterial occlusion, a platelet-rich setting where rTPA is known to have limited efficacy.10, 26 This limited efficacy may be in part due to the fact that recruited platelets release PAI-1, an inhibitor of TPA, and PAI-1 has been shown to be a major determinant in arterial thrombolysis resistance.8, 9 Approximately 60 min after drug administration, the rTPA group achieved 25% the level of pre-injury blood flow (represented as percent recanalization) compared to 75% for the DTRI-031-treated group. This effect persisted more than 100 min after drug administration until the experiment was terminated. As the vWF aptamer inhibits platelet recruitment and activation, PAI-1 levels may be reduced in thrombi in the aptamer-treated animals, which may in part result in the improved recanalization rates in arterial platelet-rich clots.

Of note, DTRI-031 was administered as an infusion over 5 min while the rTPA was infused over 45 min. This slow infusion of rTPA is necessary in humans, as more rapid infusion results in higher rates of hemorrhage with no improvement in recanalization.30 While we increased the dose of rTPA significantly in the mouse model based on other studies showing efficacy without affecting hemorrhage in rodents,26 we did not increase the dosage in the canine model but instead utilized the maximum administered dose in human stroke patients, 0.9 mg/kg,31 as increasing the dose of rTPA clinically can result in life-threatening hemorrhage. For example, when rTPA is used to treat a patient presenting with a venous lung clot (pulmonary embolus), the dose is approximately 1.5-fold that administered to a patient who presents with a stroke. Yet, this modest dose increase results in a 20% risk of hemorrhage. Therefore, to not subject canines to an unacceptable bleeding risk and to mimic the clinical setting, we utilized the accepted clinical dose of rTPA (0.9 mg/kg) for these initial dog studies. Additional studies need to be performed to determine if higher doses of rTPA can engender recanalization in this new canine carotid artery thrombosis model31 without inducing high levels of hemorrhage, as is seen in humans.

Carotid damage models of recanalization after platelet-rich arterial occlusion represent a clinical setting widely thought to be difficult to treat therapeutically.30 Currently the only therapeutic agent approved by the FDA for arterial recanalization following acute coronary and cerebrovascular thrombotic occlusion is Alteplase. Another rTPA agent called Tenecteplase has been compared to Alteplase in 2 recent clinical trials, Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits – Intra-Arterial Tenecteplase (EXTEND IA TNK) and The Norwegian Tenecteplase Stroke Trial (NOR-TEST).32, 33 The results from NOR-TEST demonstrated that the neurological improvement in patients treated with Tenecteplase was similar to the clinical standard.33 They also had the similar rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, hospital readmission, and death, suggesting that this iteration of rTPA would have similar limitations as current therapy. EXTEND IA TNK evaluated patients with a large vessel occlusion. Tenecteplase administration resulted in the vessel recanalization in 20% of patients compared to 10% of patients treated with Alteplase.32 While it represents an improvement over Alteplase, this approach remains inadequate for the large majority of patients who present with a stroke and large vessel occlusion. Moreover, with 10% recanalization in the setting of a 6.4% risk of intracranial hemorrhage, rTPA is an inefficient therapy to treat large vessel occlusion stroke. This high rate of hemorrhage is likely due to the fact that it is challenging to control rTPA activity, which significantly impacts the risk-benefit ratio of its use and limits the therapeutic window for rTPA administration to less than 3–4.5 h past last known well. By contrast, recent thrombectomy studies indicate that treatment of many stroke patients out to 16 h past last known well can improve outcome.34 Thus, we anticipate that a safer recanalization agent, such as DTRI-01, may prove beneficial to stroke patients over a larger therapeutic window.

Another important observation in the large animal model of aptamer-mediated recanalization was the lack of thromboembolism to the brain based on histopathological analysis, a known complication of rTPA. A limitation of this finding, however, is that no positive control in this experiment exists to determine the resolution of detection of embolic infarcts, as rTPA was unable to recanalize the occluded carotids; thus, it is unclear if small embolic infarcts are occurring in the aptamer-treated group but are below the resolution of histological detection. Regardless, the observation that no emboli are readily apparent in the brains of recanalized aptamer-treated animals is encouraging but must be confirmed in clinical studies.

At first glance, the idea of a drug that targets an endothelial and platelet factor breaking up a formed arterial thrombus is not intuitive; however, a growing body of literature supports the disaggregation activity of vWF inhibitors. An in vitro study performed under high fluid shear stress showed that vWF collates into thick bundles and meshes that span the vessel lumen, binding platelets together, resulting in arterial occlusion.35 Moreover, not only does vWF bind to gpIba but also to gpIIb/IIIa, and a vWF inhibitor can potentially disrupt the dynamic binding between gpIIb/IIIa and fibrinogen, which is essential in aggregation. In this setting, anti-vWF therapy could have an impact on reversing arterial occlusion by inhibiting rolling platelet adhesion to the vessel wall as well as disrupting platelet aggregation and, thereby, breaking up the interior of a thrombus. Moreover, as mentioned above, by limiting the recruitment and activation of platelets, the vWF aptamer would also be expected to limit the release of PAI-1, whose presence is known to limit endogenous thrombolysis.9 This hypothesis is supported by our observation that even in major arteries in large animals, such as the canine carotid artery, vWF aptamer DTRI-031 can engender recanalization of an occluded vessel even after 45 min of clot stabilization (Figure 4). In this model, we chose to establish an occlusive clot for 45 min before initiating treatment, as this was the time at which there was no evidence of spontaneous recanalization in the animals. We wanted to ensure we were treating a stable thrombus. We recognize that these experiments represent a proof of concept and that, over the course of further preclinical and clinical development of DTRI-031, longer times of occlusion before treatment will need to be performed to determine the upper time limit of efficacy, as the initial approval of rTPA is based on patients who present less than 3 h after having an ischemic stroke.

vWF has also been targeted by other compounds, including antibodies and aptamers, and a few have been tested for their ability to inhibit thrombosis.36, 37, 38, 39, 40 However, none of them has reported recanalization activity. Two groups have inferred vessel recanalization in their studies by using a ferric chloride-induced damage model that defined occlusion as cerebral blood flow (CBF) less than 20% of blood flow measured by laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF).41, 42 At the point of reduction in LDF, they administered their inhibitor. However, such reduced flow does not allow for clot stabilization and does not represent vessel occlusion. Nonetheless, these observations are consistent with our observations with DTRI-031. In reviewing the development of these other agents targeting vWF, none describes the development of a reversal agent, which is critical to control hemorrhage and as occurs in patients with vWD.40 The inability to control these agents may result in significant clinical morbidity, especially in closed volumes such as the skull. We also face this concern with the utilization of gpIIb/IIIa inhibitors that cannot be rapidly reversed.43

In conclusion, we believe that the development of an antidote that can readily reverse a potent antiplatelet agent such as the vWF aptamer DTRI-031 is critical for safe, clinical utility of this antiplatelet agent. Antidote design is based on Watson-Crick base pairing to the aptamer. Using this approach, an antidote could be created that completely and rapidly reversed DTRI-031 activity in vitro and in vivo.24, 29 The ability to completely and rapidly reverse such a potent, rapid-onset antiplatelet agent by a matched antidote represents a significant step forward in developing safer, parenteral antiplatelet drugs for use in the neurovascular setting.44 We believe that the antidote-controlled antiplatelet approach we describe, taken together with the highly potent antithrombotic and recanalization efficacy of the vWF aptamer and the minimal toxicity observed in mice, supports the translation of this agent into clinical studies to determine if DTRI-031 represents an effective and safer treatment option for carotid artery thrombosis, acute ischemic stroke, and platelet-rich thrombotic disease in other arteries.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Aptamer Truncates, Modifications, and AOs

Aptamer truncates were either transcribed or synthesized in-house. Software predicting RNA secondary structure (Mfold by M. Zuker) was used to aid in the design of truncates. Briefly, T7 RNA polymerase was used to transcribe initial RNA aptamer truncates T10, T21, and T22. All other aptamer truncates, modifications, and antidotes were synthesized using a MerMade 12 Oligonucleotide synthesizer (BioAutomation, Irving, TX).

Binding Assays

The KD values of each truncate and modification were determined using double-filter nitrocellulose filter-binding assays. All binding studies were performed in binding buffer F (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4],150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 0.01% BSA) at 37°C. Human purified vWF (factor VIII free) was purchased from Hematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT) and used in the double-filter nitrocellulose filter-binding assay to determine the KD of individual aptamers. Briefly, synthesized RNA was end labeled at the 5′ end with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and [γP32] ATP (PerkinElmer). Direct binding was performed by incubating trace -P32- labeled RNA with vWF in binding buffer F at 37°C for 5 min. The fraction of the nucleic acid-protein complex, which bound to the nitrocellulose membrane, was quantified with a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Non-specific binding of the radiolabeled nucleic acid was subtracted out of the binding such that only specific binding remained.

RNA Aptamer Preparation and Folding

Prior to PFA and in vivo models, RNA-based aptamers may be folded in an appropriate physiological buffer, e.g., platelet-binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM KCl) or binding buffer F with or without BSA. Aptamer solution is heated to 95°C for 3 min or 65°C for 5 min and then allowed to come to room temperature over approximately 5–10 min.

Human Whole-Blood Studies

Human blood was collected from healthy volunteers by vena puncture after written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board from both the Durham Veterans Administration Medical Center and Duke University Medical Center.

Platelet Adhesion Analysis

The Venaflux microfluidics system (Cellix, Dublin, Ireland) measures platelet adhesion on a collagen surface.45 300 μL whole blood treated with aptamer or platelet-binding buffer alone was flowed through collagen-coated micro-channels at 60 dynes for 3 min. Channels were then rinsed with saline for 3 min to wash away red blood cells (RBCs) and unbound platelets. Venaflux imaging software and Image Pro Plus were used to image bound platelets and calculate covered surface area. Aptamer was incubated at 95°C for 3 min, placed on ice for 3 min, then cooled for 10 min at room temperature. After cooling, the aptamer was kept on ice until use.

Human blood was collected into hirudin tubes from healthy volunteers by vena puncture. Total surface area covered by bound platelets in treated blood was expressed as a percentage of total coverage in negative control blood. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA; half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the aptamer was calculated using a fitted non-linear regression curve.

PFA

The PFA-100 (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL) is a whole-blood assay that measures platelet function in terms of clot formation time.46 It is highly sensitive to vWF levels. Briefly, whole blood (840 μL) was mixed with vWF aptamer in PBS with magnesium and calcium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. This mixture was then added to a collagen and ADP cartridge and tested for its closing time. The cartridge contains a microscopic aperture cut into a biologically active membrane at the end of a capillary. Whole blood is drawn through the aperture, and the membrane is coated with collagen and ADP or collagen and epinephrine, which activate platelets. The activated platelets form a plug, which occludes the aperture and stops blood flow. The time it takes for this to occur represents the closing time. The maximum closing time of the PFA-100 assay is 300 s. The effect of the AO on the activity of the aptamer was measured by mixing whole blood with aptamer, incubating for 5 min followed by adding the antidote or negative control, and testing the mixture in a PFA-100.

T-TAS

The T-TAS (Zacrox, Fujimori Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess thrombus formation in both human and canine whole blood.47 Blood was collected in a tube with hirudin in a PL chip that contains 25 capillary channels coated with type 1 collagen. The blood flow across the chip was maintained at a rate of 14 μL/min. Platelet aggregation was measured as a function of the amount of pressure (kPa) needed to maintain the flow rate. A camera was also used to observe platelet activity across the collagen-coated capillary channels.

Murine In Vivo Studies

Preclinical studies were designed to investigate in vivo efficacy of vWF aptamer as a thrombolytic and to assess the reversal potential of the antidote in the setting of intracranial hemorrhage. Investigators that performed surgery or analyzed carotid flow and imaging data were blinded to the treatment groups. All in vivo experiments were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Moreover, these committees adhere to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Carotid Artery Injury

Male and female 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Animals were anesthetized with a combination of isoflurane and tribromoethanol (125 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). The animal was intubated and mechanically ventilated (Harvard Apparatus rodent ventilator, Holliston, MA), and it was placed supine on a temperature-monitoring board. The right common carotid artery and left external jugular vein were isolated. The left jugular vein was then catheterized for all drug administration. Baseline carotid flow was obtained with a Doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Animals were treated with either control (platelet-binding buffer) or vWF aptamer, and it was allowed to circulate for 5 min. Carotid artery injury was initiated by 10% ferric chloride over 3 min as previously described.48 The blood flow was then measured for 60 min. The time to occlusion was recorded. The animals were then sacrificed.

Carotid Artery Occlusion and Thrombolysis

Male and female 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (55 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg). Through a midline ventral incision, the animal was intubated (Harvard Apparatus mouse ventilator, Holliston, MA), and the common carotid artery was isolated. Baseline carotid flow was obtained with a Doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Whatman filter paper soaked in 10% ferric chloride was placed on the artery for 3 min. Following 20 min of carotid occlusion, treatment was initiated. Through an intravenous saphenous infusion (Harvard Apparatus PHD 2000 Infusion Pump, Holliston, MA), animals were treated with control (platelet-binding buffer), vWF aptamer, or rTPA. Carotid flow was monitored for an additional 90 min to assess reperfusion. Heart rate, electrocardiogram (EKG) (ADInstruments PowerLab 4/35 EKG monitoring system, Sydney, Australia), and blood pressure (Kent Scientific CODA Non-Invasive BP Measurement system, Torrington, CT) were monitored throughout the procedure. Histological analysis was performed on the carotid arteries by H&E staining.

Saphenous Vein Bleeding

Male and female 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. The hair on the medial aspect of the right hind limb was removed. The animal was intubated and mechanically ventilated (Harvard Apparatus rodent ventilator, Holliston, MA), and it was placed supine on a temperature-monitoring board. The left external jugular vein was isolated and catheterized for all drug administration. The skin on the medial aspect of the right hind limb was incised, exposing a length of the saphenous neurovascular bundle; the bundle was covered with normal saline to prevent drying. To assess hemostasis, the right saphenous vein was transected by piercing it with a 23G needle, followed by a longitudinal incision made in the distal portion of the vessel. Blood was gently wicked away until hemostasis occurred. The clot was then removed to restart bleeding, and the blood was again wicked away until hemostasis occurred again. Clot disruption was repeated after every incidence of hemostasis to the end of the experiment.

Canine Carotid Artery Occlusion and Thrombolysis

Male and female adult beagles (7–11 kg) were anesthetized and intubated. Right femoral arterial and venous catheter was obtained. The right carotid artery was exposed, and baseline carotid flow was obtained using a Doppler flow probe. Thrombosis was induced with a 50% ferric chloride patch for 15 min, and the clot was stabilized for 45 min. Dogs were then intravenously infused with vehicle, 0.9 mg/kg TPA, or 0.5 mg/kg vWF aptamer. The aptamer and vehicle were administered as a bolus while the rTPA was administered by standard clinical protocol of 10% bolus followed by the remaining drug infused over 45 min. Carotid flow was monitored for 120 min. Thus, animals were maintained under sedation and intubated for approximately 3.5–4 h. A flow probe distal to the site of thrombosis monitored blood flow transit time throughout the experiment. Carotid angiography demonstrated baseline patency, thrombotic occlusion, and recanalization.31 Periodic blood draws assessed platelet inhibition (PFA-100). At the conclusion of the experiment, the brain and carotid arteries of each animal were collected and embedded for histological analyses by H&E staining. After 7 days in 10% formalin, 4-mm sections of the brain were embedded in paraffin and visually analyzed for hemorrhage or infarct as previously described.31

Toxicology Study Methods

Male and female C57BL/6J mice, 10–12 weeks old (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), received a single intravenous injection of DTRI-031 at 300 mg/kg. Approximately 6 h, 72 h, or 7 days after injection, 20 μL whole blood was collected from the submandibular vein by the use of a 3-mm Goldenrod animal lancet (MEDIpoint, Mineola, NY) and an EDTA-coated microcapillary tube. Samples were evaluated for a 3-part differential CBC with a HemaTrue Veterinary Hematology Analyzer (Heska, Loveland, CO). After CBC sample collection, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, intubated, mechanically ventilated (Harvard Apparatus rodent ventilator, Holliston, MA), and placed supine on a temperature-monitoring board. Approximately 500 μL whole blood was collected directly via venipuncture from the caudal vena cava through a V-cut incision through the skin and abdominal wall. Samples were evaluated for a comprehensive diagnostic chemistry panel with a DRI-CHEM 7000 Veterinary Chemistry Analyzer (Heska, Loveland, CO).

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA ith Dunnett’s multiple comparison post test to compare multiple doses of DTRI-031 in preventing platelet-rich thrombosis in vivo. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare DTRI-031, rTPA, and buffer control in the murine model of carotid artery vessel occlusion and to compare platelet inhibition of DTRI-031 in canine whole blood. A z-test was used to compare vessel recanalization of aptamer-treated animals with rTPA and saline control in the canine model of carotid occlusion. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KS test) was used to compare hemorrhage and antidote reversal.

Author Contributions

S.M.N. contributed to the concept and design, performed statistical analysis, and drafted and revised the manuscript. D.D. conducted experiments, performed statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript. D.G.W. contributed to the experimental design, performed experiments, and revised the manuscript. G.A.P., J.M.L., N.V., A.H., S.E.T., N.J.M., H.M., C.J., K.C., J.W., C.B., and L.S. conducted experiments and performed statistical analysis. M.E.J. contributed to the experimental design and performed experiments. R.E.R. and S.K. conducted experiments. M.R.H. contributed to the experimental design and performed statistical analysis. R.C.B. and J.L.Z. contributed to the experimental design and revised the manuscript. B.A.S. contributed to the concept and design and drafted and revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Duke University and The Ohio State University have submitted patent applications upon this work and its application.

Acknowledgments

We thank Russell R. Lonser for extensive review of the manuscript and Reginald Lerebours and Maragatha Kuchibhatla for statistical support and guidance. Funding was received from the NIH (5K12NS080223-3,220901 to S.M.N. and U54-HL112307 and R01-HL065222 to B.A.S.).

Contributor Information

Shahid M. Nimjee, Email: shahid.nimjee@osumc.edu.

Bruce A. Sullenger, Email: bruce.sullenger@duke.edu.

References

- 1.Adams H.P., Jr. Stroke: a vascular pathology with inadequate management. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 2003;21:S3–S7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306005-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Investigators T.G.A., GUSTO Angiographic Investigators The effects of tissue plasminogen activator, streptokinase, or both on coronary-artery patency, ventricular function, and survival after acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:1615–1622. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311253292204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lansberg M.G., Bluhmki E., Thijs V.N. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40:2438–2441. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman M., Monroe D.M., 3rd A cell-based model of hemostasis. Thromb. Haemost. 2001;85:958–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leebeek F.W., Eikenboom J.C. Von Willebrand’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:2067–2080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders Y.V., Eikenboom J., de Wee E.M., van der Bom J.G., Cnossen M.H., Degenaar-Dujardin M.E., Fijnvandraat K., Kamphuisen P.W., Laros-van Gorkom B.A., Meijer K., WiN Study Group Reduced prevalence of arterial thrombosis in von Willebrand disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:845–854. doi: 10.1111/jth.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y., Carmeliet P., Fay W.P. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a major determinant of arterial thrombolysis resistance. Circulation. 1999;99:3050–3055. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.23.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribo M., Montaner J., Molina C.A., Arenillas J.F., Santamarina E., Alvarez-Sabín J. Admission fibrinolytic profile predicts clot lysis resistance in stroke patients treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Thromb. Haemost. 2004;91:1146–1151. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomkins A.J., Schleicher N., Murtha L., Kaps M., Levi C.R., Nedelmann M., Spratt N.J. Platelet rich clots are resistant to lysis by thrombolytic therapy in a rat model of embolic stroke. Exp. Transl. Stroke Med. 2015;7:2. doi: 10.1186/s13231-014-0014-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topol E.J. Novel antithrombotic approaches to coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1995;75:27B–33B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(95)80007-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciccone A., Motto C., Abraha I., Cozzolino F., Santilli I. Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;3:CD005208. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005208.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nimjee S.M., Crofton A., Oh N., Kirsch W., Haglund M.M., Grant G.A. Coagulation for the neurosurgeon. In: Winn H.R., editor. Seventh Edition. Volume 1. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2017. pp. 146–150. (Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodruff R.S., Xu Y., Layzer J., Wu W., Ogletree M.L., Sullenger B.A. Inhibiting the intrinsic pathway of coagulation with a factor XII-targeting RNA aptamer. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:1364–1373. doi: 10.1111/jth.12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimjee S.M., Rusconi C.P., Sullenger B.A. Aptamers: an emerging class of therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005;56:555–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunaratne R., Kumar S., Frederiksen J.W., Stayrook S., Lohrmann J.L., Perry K., Bompiani K.M., Chabata C.V., Thalji N.K., Ho M.D. Combination of aptamer and drug for reversible anticoagulation in cardiopulmonary bypass. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:606–613. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chabata C.V., Frederiksen J.W., Sullenger B.A., Gunaratne R. Emerging applications of aptamers for anticoagulation and hemostasis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2018;25:382–388. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buddai S.K., Layzer J.M., Lu G., Rusconi C.P., Sullenger B.A., Monroe D.M., Krishnaswamy S. An anticoagulant RNA aptamer that inhibits proteinase-cofactor interactions within prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:5212–5223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimjee S.M., Rusconi C.P., Harrington R.A., Sullenger B.A. The potential of aptamers as anticoagulants. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2005;15:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimjee S.M., Oney S., Volovyk Z., Bompiani K.M., Long S.B., Hoffman M., Sullenger B.A. Synergistic effect of aptamers that inhibit exosites 1 and 2 on thrombin. RNA. 2009;15:2105–2111. doi: 10.1261/rna.1240109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusconi C.P., Roberts J.D., Pitoc G.A., Nimjee S.M., White R.R., Quick G., Jr., Scardino E., Fay W.P., Sullenger B.A. Antidote-mediated control of an anticoagulant aptamer in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1423–1428. doi: 10.1038/nbt1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusconi C.P., Scardino E., Layzer J., Pitoc G.A., Ortel T.L., Monroe D., Sullenger B.A. RNA aptamers as reversible antagonists of coagulation factor IXa. Nature. 2002;419:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Povsic T.J., Vavalle J.P., Aberle L.H., Kasprzak J.D., Cohen M.G., Mehran R., Bode C., Buller C.E., Montalescot G., Cornel J.H., RADAR Investigators A Phase 2, randomized, partially blinded, active-controlled study assessing the efficacy and safety of variable anticoagulation reversal using the REG1 system in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results of the RADAR trial. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:2481–2489. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nimjee S.M., Lohrmann J.D., Wang H., Snyder D.J., Cummings T.J., Becker R.C., Oney S., Sullenger B.A. Rapidly regulating platelet activity in vivo with an antidote controlled platelet inhibitor. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:391–397. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oney S., Nimjee S.M., Layzer J., Que-Gewirth N., Ginsburg D., Becker R.C., Arepally G., Sullenger B.A. Antidote-controlled platelet inhibition targeting von Willebrand factor with aptamers. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:265–274. doi: 10.1089/oli.2007.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orset C., Macrez R., Young A.R., Panthou D., Angles-Cano E., Maubert E., Agin V., Vivien D. Mouse model of in situ thromboembolic stroke and reperfusion. Stroke. 2007;38:2771–2778. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.487520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi Y., Moriki T., Igari A., Matsubara Y., Ohnishi T., Hosokawa K., Murata M. Studies of a microchip flow-chamber system to characterize whole blood thrombogenicity in healthy individuals. Thromb. Res. 2013;132:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daidone V., Barbon G., Cattini M.G., Pontara E., Romualdi C., Di Pasquale I., Hosokawa K., Casonato A. Usefulness of the Total Thrombus-Formation Analysis System (T-TAS) in the diagnosis and characterization of von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2016;22:949–956. doi: 10.1111/hae.12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monroe D.M., Hoffman M. A mouse bleeding model to study oral anticoagulants. Thromb. Res. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S6–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zakeri A.S., Nimjee S.M. Use of Antiplatelet Agents in the Neurosurgical Patient. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2018;29:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huttinger A.L., Wheeler D.G., Gnyawali S., Dornbos D., 3rd, Layzer J.M., Venetos N., Talentino S., Musgrave N.J., Jones C., Bratton C. Ferric Chloride-induced Canine Carotid Artery Thrombosis: A Large Animal Model of Vascular Injury. J. Vis. Exp. 2018 doi: 10.3791/57981. Published online September 7, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell B.C., Mitchell P.J., Churilov L., Yassi N., Kleinig T.J., Yan B., Dowling R.J., Bush S.J., Dewey H.M., Thijs V., EXTEND-IA TNK Investigators Tenecteplase versus alteplase before endovascular thrombectomy (EXTEND-IA TNK): A multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Int. J. Stroke. 2018;13:328–334. doi: 10.1177/1747493017733935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logallo N., Novotny V., Assmus J., Kvistad C.E., Alteheld L., Rønning O.M., Thommessen B., Amthor K.F., Ihle-Hansen H., Kurz M. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for management of acute ischaemic stroke (NOR-TEST): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:781–788. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lansberg M.G., Mlynash M., Hamilton S., Yeatts S.D., Christensen S., Kemp S., Lavori P.W., Gutierrez S.O., Broderick J., Heit J., DEFUSE 3 Investigators Association of Thrombectomy With Stroke Outcomes Among Patient Subgroups: Secondary Analyses of the DEFUSE 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4587. Published online January 28, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y., Chen J., López J.A. Flow-driven assembly of VWF fibres and webs in in vitro microvessels. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7858. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diaz J.A., Wrobleski S.K., Alvarado C.M., Hawley A.E., Doornbos N.K., Lester P.A., Lowe S.E., Gabriel J.E., Roelofs K.J., Henke P.K. P-selectin inhibition therapeutically promotes thrombus resolution and prevents vein wall fibrosis better than enoxaparin and an inhibitor to von Willebrand factor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:829–837. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diener J.L., Daniel Lagassé H.A., Duerschmied D., Merhi Y., Tanguay J.F., Hutabarat R., Gilbert J., Wagner D.D., Schaub R. Inhibition of von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet activation and thrombosis by the anti-von Willebrand factor A1-domain aptamer ARC1779. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7:1155–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siller-Matula J.M., Merhi Y., Tanguay J.F., Duerschmied D., Wagner D.D., McGinness K.E., Pendergrast P.S., Chung J.K., Tian X., Schaub R.G., Jilma B. ARC15105 is a potent antagonist of von Willebrand factor mediated platelet activation and adhesion. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:902–909. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markus H.S., McCollum C., Imray C., Goulder M.A., Gilbert J., King A. The von Willebrand Inhibitor ARC1779 Reduces Cerebral Embolization After Carotid Endarterectomy: A Randomized Trial. Stroke. 2011;42:2149–2153. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.616649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Momi S., Tantucci M., Van Roy M., Ulrichts H., Ricci G., Gresele P. Reperfusion of cerebral artery thrombosis by the GPIb-VWF blockade with the Nanobody ALX-0081 reduces brain infarct size in guinea pigs. Blood. 2013;121:5088–5097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-464545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Behot A., Gauberti M., Martinez De Lizarrondo S., Montagne A., Lemarchand E., Repesse Y., Guillou S., Denis C.V., Maubert E., Orset C., Vivien D. GpIbα-VWF blockade restores vessel patency by dissolving platelet aggregates formed under very high shear rate in mice. Blood. 2014;123:3354–3363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-543074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez de Lizarrondo S., Gakuba C., Herbig B.A., Repessé Y., Ali C., Denis C.V., Lenting P.J., Touzé E., Diamond S.L., Vivien D., Gauberti M. Potent Thrombolytic Effect of N-Acetylcysteine on Arterial Thrombi. Circulation. 2017;136:646–660. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dornbos D., 3rd, Katz J.S., Youssef P., Powers C.J., Nimjee S.M. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors in Prevention and Rescue Treatment of Thromboembolic Complications During Endovascular Embolization of Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2018;82:268–277. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blake C.M., Wang H., Laskowitz D.T., Sullenger B.A. A reversible aptamer improves outcome and safety in murine models of stroke and hemorrhage. Oligonucleotides. 2011;21:11–19. doi: 10.1089/oli.2010.0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanaji T., Kanaji S., Montgomery R.R., Patel S.B., Newman P.J. Platelet hyperreactivity explains the bleeding abnormality and macrothrombocytopenia in a murine model of sitosterolemia. Blood. 2013;122:2732–2742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortel T.L., James A.H., Thames E.H., Moore K.D., Greenberg C.S. Assessment of primary hemostasis by PFA-100 analysis in a tertiary care center. Thromb. Haemost. 2000;84:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arima Y., Kaikita K., Ishii M., Ito M., Sueta D., Oimatsu Y., Sakamoto K., Tsujita K., Kojima S., Nakagawa K. Assessment of platelet-derived thrombogenicity with the total thrombus-formation analysis system in coronary artery disease patients receiving antiplatelet therapy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016;14:850–859. doi: 10.1111/jth.13256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konstantinides S., Schäfer K., Thinnes T., Loskutoff D.J. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and its cofactor vitronectin stabilize arterial thrombi after vascular injury in mice. Circulation. 2001;103:576–583. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]