Abstract

Introduction:

Adolescent participation in violence prevention programming is critical in addressing the nation’s elevated rates of youth fighting and violence. However, little is known about the secular trends and correlates of violence prevention program participation in the U.S. Using national data, the authors examined the year-by-year trends and correlates of participation among American adolescents over a 15-year span.

Methods:

National trend data (2002–2016) was analyzed on non-Hispanic black/African American (n=35,216), Hispanic (n=45,780), and non-Hispanic white (n=153,087) youth aged 12–17 years from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2018. Consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s trend analysis guidelines, the authors conducted logistic regression analyses with survey year specified as an independent variable and youth violence program participation specified as the dependent variable while controlling for sociodemographic factors and other key correlates.

Results:

Youth participation in violence prevention programs significantly decreased from 16.7% in 2002 to 11.7% in 2016, a 29% relative decrease in participation. A significant declining trend in participation over time was found across all sociodemographic subgroups examined and among youth reporting the use of violence and no use of violence in the past year. Participation among black/African American youth was significantly greater than Hispanic youth who, in turn, had significantly higher participation rates than white youth.

Conclusions:

Youth participation in violence prevention programming has decreased in recent years, with particularly large declines observed among younger adolescents (aged 12–14 years), youth in higher income households, and youth reporting no past-year use of violence.

INTRODUCTION

Youth violence is a serious public health concern that impacts the lives of millions of youth and their families across the U.S. Nearly one in four American adolescents is involved each year in fighting and violence1,2 and estimates indicate that the annual cost of youth violence—resulting from productivity losses and medical expenses—is more than $14 billion.3 Moreover, substantial research has shown that youth violence is related to numerous adverse outcomes, including serious injury, mental health problems, and criminal justice system involvement.4,5 Beyond its impact on those directly involved in violence, there is compelling evidence that youth violence can negatively affect the health of neighborhoods and communities.4–6

However, recent evidence suggests that youth violence is decreasing. Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that the proportion of youth involved in violence dropped by nearly 30% between 2002 and 2014.1 Similarly, arrests for violent crime have decreased nationally7 and international data suggests that youth violence is decreasing worldwide.8 Notably, similar reductions have been observed in other externalizing behaviors, such as substance use,9,10 drug selling,11 and truancy.12 A recent study found that overall rates of abstention from a wide range of risky behaviors has increased substantially since the early 2000s.13

Despite an overall decrease in youth violence, critical disparities persist. Male youth are more likely to engage in violence than female youth14 and, although rates of violence are decreasing among all racial/ethnic groups, non-Hispanic black/African American and Hispanic youth continue to be far more likely than non-Hispanic white youth to report involvement in violence.1 Youth who are part of a gang or endorse psychopathic symptomology additionally report higher use of and exposure to violence than their peers.15–18 Scholars have offered various explanations for the decline in youth violence over the last two decades. Some suggest that an increased gender equity is associated with reduced violence due to a decrease in the normalization of violent conflict resolution.8 It may also be part of a larger downward trend of risky and antisocial behaviors, such as crime11 and drug use,19 among youth. A decrease in violence may additionally be associated with the implementation of effective violence prevention programs across the country.20 Prevention programs can vary in format and scope, but the majority of programs have addressed violence at the individual or familial level and are either universal programs (delivered to all youths/families in a community) or programs targeted to at-risk youth.21,22

The extant literature has examined the efficacy of individual youth violence prevention programs (e.g., Swaim and Kelly23), compared programs (e.g., Fagan and Catalano20), and estimated cross-sectional participation prevalence (e.g., Finkelhor et al.24). Several programs have been found to be effective,20 even among youth who are engaged in chronic, serious violence.25 Importantly, however, there remains a dearth of knowledge regarding trends in participation in these programs at the population level. As such, the objective of the present study is to employ national data to examine trends and correlates of violence prevention program participation of youth aged 12–17 years in the U.S. between 2002 and 2016. Additionally, differences in participation rates across gender and racial/ethnic subgroups are examined. Increased knowledge of differential participation in prevention programming among key subgroups has implications for program delivery and policies determining resource allocation and program access. Moreover, understanding changes in participation over time can aid in measuring the potential relationship between prevention programming and the decrease in violence seen in the extant literature.

METHODS

Study Sample

Data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) NSDUH from the years 2002 to 2016 were used for this study. The NSDUH data are collected annually from a national survey of civilian, non-institutionalized people aged ≥12 years.26 The NSDUH sampling methodology identifies potential participants who are living in traditional residences, without a permanent residence (e.g., homeless people in shelters), or are living in non-institutionalized group homes; and oversamples youth aged 12–17 years. The survey is administered in participants’ own homes using computer-assisted interviewing technologies. Participants answer the majority of questions on audio computer-assisted interviewing devices, which permits privacy for the respondent and potentially decreases any social desirability bias in their survey responses. All other questions are asked by the interviewer and entered directly into a computer. The Boston University IRB did not require IRB approval for this study as it used de-identified, secondary data.

Measures

To measure youth violence participation, all participants were asked: During the past 12 months have you participated in a violence prevention program, where you learn ways to avoid fights and control anger?26 Youth were coded as having participated in a program (1) or not (0) in the past year.

Several sociodemographic variables were used as controls in the analyses. Four dichotomous variables were included: age (12–14, 15–17), sex (male, female), urbanicity (nonmetropolitan, metropolitan—based on Office of Management and Budget guidelines27), and father’s presence in the home. Youth race/ethnicity was restricted to non-Hispanic white (hereafter white; n=153,087), non-Hispanic black/African American (hereafter black/African American; n=35,216), and Hispanic youth (n=45,780) who represented the majority (92.45%) of the sample. Annual family income was divided into four segments (<$20,000, $20,000–$39,999, $40,000–$74,999, ≥$75,000).

Religiosity was measured by four questions examining the centrality of religious practice to the youth’s life, consistent with prior studies (e.g., Farrington and Loeber28; Salas-Wright and colleagues29). Risk propensity was composed of two items, How often do you get a real kick out of doing things that are a little dangerous? and How often do you like to test yourself by doing something a little risky?26 Consistent with recent NSDUH-based research, the responses were summed to generate an ordinal scale of low-, medium- and high-risk propensity (see Vaughn et al.13).

As in prior research, an endorsement of parental conflict was defined as ten or more fights with youth’s parents in the past year (see Salas-Wright and colleagues30 and Shook et al.31). Parental affirmation was defined on a continuous scale based on two items measuring youth’s perception of their parents’ verbal displays of support (e.g., the parent says “good job” to them).

Three school-related variables were included in the analyses: enrollment, average grades, and school engagement. If participants had attended any form of school in the last year, they were considered enrolled. Average student grade was treated as a dichotomous variable (A–C, D or lower). Five items from the NSDUH about youth’s experiences at school composed a continuous measure of school engagement (Cronbach’s α=0.77). Items included questions like, How often did you feel that the school work you were assigned to do was meaningful and important?26 These items are described in greater detail elsewhere (e.g., Maynard and colleagues32).

Seven risky behaviors were included as dichotomous variables. Participants were asked if they had engaged in any of the following behaviors in the past year: stolen something worth >$50, sold illicit drugs, been involved in a serious fight at school or work, been in a group fight, attacked someone with serious intent to harm, or carried a handgun. Participants were also asked if they had been arrested or booked for a law violation in the past year. A summative dichotomous variable indicating any past-year use of violence (fight, group fight, or attack with intent to harm) was created.

Statistical Analysis

First, logistic regression analyses using the pooled 2002–2016 data were conducted to examine the association between program participation and demographic characteristics (Table 1). Annual participation prevalence estimates were then generated for the full sample and by racial/ethnic and gender subgroups (Figures 1 and 2, Appendix Figure 1). Then, the significance of the linear trend was tested across subgroups, controlling for sociodemographic factors (Table 1). In the tests of trend, survey year was included as a continuous variable according to the methods outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.33 Tests of trend were also examined among youth who did and did not engage in risky behavior. The tests of trends were repeated with all psychosocial, parental, school, and risk behavioral correlates included in the models. Interaction effects between sociodemographic variables X survey year (e.g., gender X year) and violence use X year (i.e., violence X year) were also examined. Next, a series of logistic regressions were performed to examine the association between each of the psychosocial, parental, school, and risk behavioral correlates while controlling for sociodemographic controls and survey year (Table 2). All estimates were weighted to account for NSDUH’s sampling design based on the guidelines provided by SAMHSA.34 All analyses were performed in Stata SE, version 13 in 2018.

Table 1.

Overall Prevalence and Tests of Trends for Past-Year Violence Prevention Program Participation, 2002–2016

| During the past 12 months, have you participated in a violence prevention program, where you learn ways to avoid fights and control anger? |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth subgroups | No (n=198,213; 85.5%), % (95% CI) | Yes (n=33,658; 14.5%), % (95% CI) | Pooled data, AOR (95% CI) | Test of trend (year by year data), AOR (95% CI) |

| All adolescents | 85.76 (85.57, 85.95) | 14.24 (14.05, 14.43) | — | 0.975** (0.972, 0.978) |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 12–14 | 46.67 (46.18, 46.75) | 62.85 (62.16, 63.53) | 1.936** (1.876, 1.997) | 0.969** (0.965, 0973) |

| 15–17 | 53.53 (53.25, 53.82) | 37.15 (36.47, 37.84) | — | 0.985** (0.979, 0.991) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 48.88 (48.59, 49.18) | 49.21 (48.53, 49.89) | 1.038* (1.007, 1.069) | 0.972** (0.968, 0.976) |

| Male | 51.12 (50.82, 51.41) | 50.79 (50.11, 51.47) | — | 0.978** (0.973, 0.983) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 64.62 (64.17, 65.06) | 51.92 (51.09, 52.74) | — | 0.971** (0.967, 0.976) |

| Black | 14.14, (13.88, 14.40) | 25.93 (25.18, 26.69) | 1.986** (1.911, 2.065) | 0.981** (0.973, 0.989) |

| Hispanic | 21.25 (20.88, 21.62) | 22.16 (21.42, 22.91) | 1.183** (1.131, 1.239) | 0.977** (0.968, 0.987) |

| Income | ||||

| <$20,000 | 16.09 (15.79, 16.39) | 23.78 (23.15, 24.43) | 1.413** (1.339, 1.491) | 0.982** (0.973, 0.990) |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 20.71 (20.44, 20.98) | 23.65 (22.97, 24.33) | 1.206** (1.150, 1.264) | 0.982** (0.974, 0.991) |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 28.20 (27.92, 28.48) | 25.89 (25.25, 26.53) | 1.073** (1.029, 1.119) | 0.973** (0.966, 0.980) |

| ≥$75,000 | 35.00 (34.56, 35.44) | 26.69 (26.04, 27.35) | — | 0.966** (0.959, 0.972) |

| Father in household | ||||

| No | 25.54 (25.26, 25.83) | 31.82 (31.17, 32.49) | — | 0.982** (0.976, 0.988) |

| Yes | 74.46 (74.17, 74.74) | 68.18 (67.51, 68.83) | 0.996 (0.961, 1.032) | 0.972** (0.968, 0.976) |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Non-metro | 93.48 (93.25, 93.70) | 93.28 (92.84, 93.70) | — | 0.980** (0.967, 0.994) |

| Metropolitan | 6.52 (6.30, 7.16) | 6.72 (6.30, 7.16) | 1.070* (1.007, 1.136) | 0.975** (0.971, 0.978) |

| Use of violence | ||||

| Past year | ||||

| No | 73.54 (73.31, 73.76) | 62.35 (61.62, 63.09) | — | 0.970** (0.966, 0.974) |

| Yes | 24.46 (26.24, 26.69) | 37.65 (36.91, 38.38) | 1.487** (1.439, 1.537) | 0.985** (0.979, 0.992) |

Notes: AORs for pooled data adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, father in household, urbanicity, and survey year. Tests of trends conducted while controlling for all sociodemographic factors. Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<.05; **p<?).

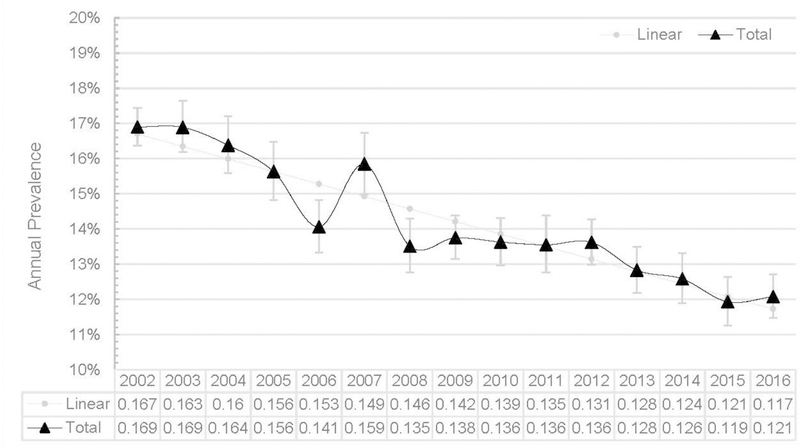

Figure 1.

Survey adjusted prevalence estimates and 95% CI for annual adolescent (aged 12 to 17 years) participation in violence prevention programming in the U.S.

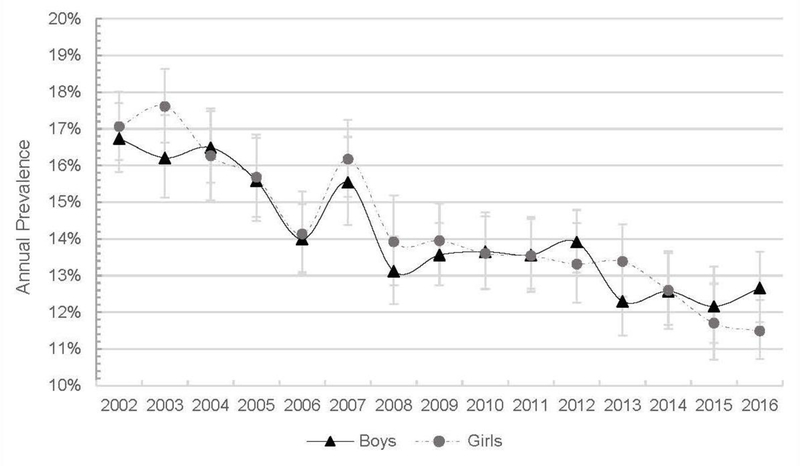

Figure 2.

Survey adjusted prevalence estimates and 95% CI for annual adolescent (aged 12 to 17 years) participation in violence prevention programming in the U.S., by race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Correlates of Youth Violence Prevention Program Participation, 2002–2014

| During the past 12 months, have you participated in a violence prevention program, where you learn ways to avoid fights and control anger? |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates of participation | No (n=198,213; 85.5%), % or mean (95% CI) | Yes (n =33,658; 14.5%), % or mean (95% CI) | Pooled data, AOR (95% CI) |

| Intrapersonal factors | |||

| Risk propensity | |||

| Low | 60.03 (59.37, 60.69) | 57.81 (57.56, 58.07) | — |

| Medium | 18.78 (18.22, 19.35) | 18.35 (18.15, 18.55) | 1.020 (0.978, 1.063) |

| High | 21.19 (20.70, 21.69) | 23.84 (23.60, 24.08) | 0.995 (0.962, 1.028) |

| Religiosity (mean) | 2.179 (2.161, 2.197) | 2.004 (1.995, 2.013) | 1.068** (1.055, 1.081) |

| Parental factors | |||

| Parental conflict, past year | |||

| <10 fights | 79.96 (79.42, 80.49) | 77.52 (77.30, 77.74) | — |

| ≥10 fights | 20.04 (19.51, 20.58) | 22.48 (22.26, 22.70) | 1.008 (0.975, 1.043) |

| Parental affirmation (mean) | 1.768 (1.760, 1.777) | 1.711 (1.707, 1.714) | 1.143** (1.114, 1.173) |

| School factors | |||

| School enrollment, past year | |||

| No | 8.21 (7.84, 8.60) | 6.72 (6.57, 6.89) | — |

| Yes | 91.79 (91.40, 92.16) | 93.28 (93.11, 93.43) | 1.074* (1.017, 1.135) |

| Average grades | |||

| A–C | 93.73 (93.34, 94.09) | 94.35 (94.19, 94.49) | — |

| D or lower | 6.27 (5.91, 6.66) | 5.65 (5.51, 5.81) | 1.040 (0.967, 1.117) |

| School engagement (mean) | 3.213 (3.205, 3.220) | 3.046 (3.042, 3.049) | 1.459** (1.421, 1.500) |

| Risk behavior | |||

| Arrested/booked | |||

| No | 95.29 (95.00, 95.56) | 97.07 (96.97, 97.18) | — |

| Yes | 4.71 (4.44, 5.00) | 2.98 (2.82, 3.03) | 1.744** (1.621, 1.876) |

| Stole >$50 | |||

| No | 94.99 (94.68, 95.29) | 96.26 (96.13, 96.28) | — |

| Yes | 5.01 (4.71, 5.32) | 3.74 (3.62, 3.87) | 1.261** (1.156, 1.375) |

| Sold drugs | |||

| No | 96.83 (96.58, 97.07) | 96.92 (96.81, 97.02) | — |

| Yes | 3.17 (2.93, 3.42) | 3.08 (2.98, 3.19) | 1.430** (1.321, 1.548) |

| Serious fight | |||

| No | 71.47 (70.77, 72.16) | 80.85 (80.64, 81.05) | — |

| Yes | 28.53 (27.84, 29.23) | 19.15 (18.95, 19.36) | 1.485** (1.431, 1.541) |

| Group fight | |||

| No | 80.65 (80.11, 81.17) | 86.79 (86.60, 86.97) | — |

| Yes | 19.35 (18.83, 19.89) | 13.21 (13.03, 13.40) | 1.439** (1.385, 1.496) |

| Attacked with intent to harm | |||

| No | 89.64 (89.14, 90.11) | 93.94 (93.82, 94.06) | — |

| Yes | 10.36 (9.89, 10.86) | 6.06 (5.94, 6.18) | 1.601** (1.514, 1.693) |

| Carried a handgun | |||

| No | 95.65 (95.37, 95.91) | 96.52 (96.41, 96.63) | — |

| Yes | 4.35 (4.09, 4.63) | 3.48 (3.37, 3.59) | 1.376** (1.278, 1.481) |

Notes: AOR for pooled data adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, household income, father in household, urbanicity, and survey year. Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of youth reporting participation versus no participation in violence prevention programming. Younger adolescents were significantly more likely than older adolescents to report participation (AOR=1.936, 95% CI=1.876, 1.997). Girls had higher odds of participation than boys (AOR=1.038, 95% CI=1.007, 1.069). Black/African American youth (AOR=1.986, 95% CI=1.911, 2.065) and Hispanic youth (AOR=1.183, 95% CI=1.131, 1.239) were significantly more likely to participate in prevention programs than their white peers. Supplementary analyses revealed that black/African American youth also had significantly higher odds of participation than Hispanic youth (AOR=1.679, 95% CI=1.591, 1.770). Youth residing in low- to moderate-income households were significantly more likely to report participation, compared with youth residing in households with incomes of ≥$75,000 per year. Nonmetropolitan youth had higher odds of participation than metropolitan youth (AOR=1.070, 95% CI=1.007, 1.136). Youth who used violence in the past year had higher odds of participating in prevention programming than youth who had not used violence (AOR=1.487, 95% CI=1.439, 1.537). The presence of the father in a household was not significantly associated with participation.

Youth participation in violence prevention programs significantly decreased from 16.7% in 2002 to 11.7% in 2016 (Figure 1; AOR=0.975, 95% CI=0.972, 0.978). A significant declining trend in participation over time was found across all sociodemographic subgroups examined and among youth reporting the use of violence and no use of violence in the past year (Table 1).

Although participation across all racial/ethnic groups decreased, participation among black/African American youth was significantly greater than Hispanic youth who, in turn, had significantly higher participation rates than white youth (as evidenced by the non-overlapping 95% CIs; Figure 2). Boys and girls participated at similar rates between 2002 and 2016 (as evidenced by the overlapping 95% CIs). All tests of trend described above and displayed in Table 1 were adjusted for sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, gender); however, supplementary analyses were also conducted that controlled for sociodemographic factors and all of the psychosocial, parental, school, and risk behavioral correlates examined in Table 2. Results from these supplemental tests revealed that the direction, significance, and magnitude of the annual trends among the whole sample and across the subgroups did not change when these additional variables were included as statistical controls. Among youth involved in risky behavior, there was a significant decrease in participation from 2002 to 2016 among those who engaged in theft (AOR=0.978, 95% CI=0.961, 0.996), serious fights (AOR=0.989, 95% CI=0.981, 0.996), or group fights (AOR=0.991, 95% CI=0.983, 0.999). The trend was not significant among those who had been arrested (AOR=0.994, 95% CI=0.976, 1.013), sold drugs (AOR=1.006, 95% CI=0.983,1.029), attacked someone with the intent to harm (AOR=0.994, 95% CI=0.981, 1.008), or carried a handgun (AOR=1.001, 95% CI=0.983, 1.019).

Interaction effects were identified for age, income, and presence of father in the household (results available on request). Specifically, this study found that the downward trend was significantly more pronounced among younger adolescents (compared with older adolescents), adolescents in higher income households (compared with adolescents in lower income households), and adolescents with a father in the home (compared with those without a father present in the home). No significant interactions were identified for gender or race/ethnicity. Additionally, although participation decreased among youth reporting use (AOR=0.985, 95% CI=0.979, 0.992) and no use of violence (AOR=0.970, 95% CI=0.966, 0.974), decreases among those not using violence were significantly greater than those of youth reporting past-year use of violence.

As shown in Table 2, several prosocial correlates, like parental affirmation (AOR=1.143, 95% CI=1.114, 1.173) and school engagement (AOR=1.459, 95% CI=1.421, 1.500), were associated with the increased likelihood of youth participation in a violence prevention program. Risk behavioral correlates, like being involved in a fight at work/school (AOR=1.485, 95% CI=1.431, 1.541) and carrying a handgun (AOR=1.376, 95% CI=1.278, 1.481), were also found to be related to an increased odds of participation in a violence prevention program.

DISCUSSION

The findings provide clear and compelling evidence that youth participation in violence prevention programs declined significantly between 2002 and 2016, decreasing by nearly 30% over a 15-year period. Notably, this downward trend was observed among all demographic subgroups examined, even when controlling for an array of sociodemographic factors as well as key psychosocial, parental, school, and risk behavioral correlates. Reviews of violence prevention programming evaluations have found that many school-based prevention programs are universal, meaning that all students at a school engage in the program regardless of their risk or past use of violence.20,35 The common implementation of universal programs could account for decreased participation across groups, as access to these programs would decrease evenly among all youth.

Despite overall decreases in participation, black/African American and Hispanic youth were more likely to participate than white youth across all survey years. This disparity may be because of differences in access. A review of prevention programs for aggressive and delinquent behaviors noted that the majority of universal programs tended to be implemented in schools that serve communities with lower SES and higher crime.21 Black/African American and Hispanic households are nearly twice as likely as white households to live in poverty36; thus, youth of color may be more likely to attend schools implementing universal prevention programs. Youth of color are also more likely to be exposed to community violence than their white peers.37 It is therefore plausible that black/African American and Hispanic youth may be more likely to participate in programming designed to respond to a need for targeted prevention efforts.

Beyond trends, the examination of the correlates of program participation suggest that there may be two types of adolescents who participated in violence prevention programs: (1) highly involved youth who may have increased voluntary participation in several extracurricular activities; and (2) youth who are involved in violent and illegal behavior, who may be mandated into such programs. These two groups parallel risk profiles for youth use of violence.38 Adolescents who report feeling more connected to school, their parents, and religion have lower odds of partaking in violence than youth who report feeling less connected.39–41 Among these youth, it may be that participation in prevention programs supports less use of violence, or that they may feel more compelled to contribute to a safe school/neighborhood environment through their participation.

Limitations

Despite the many assets of this study, it is not without its limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow for causal conclusions to be drawn about the decrease in prevention programming on violence over time. Meta-analyses indicate that several prevention programs have been successful at reducing violence20,21; therefore, the decrease in program participation may reflect a decrease in community need. However, it may also reflect a decrease in funding for such programs, school districts preferring other types of socioemotional learning programming to violence prevention, or other causes. More research is needed to examine this association. The violence prevention program participation measure focuses on preventing fights and anger management, which may result in youth not reporting participation in other forms of violence prevention, such as dating abuse prevention. Additionally, the question does not permit the analyses to account for differences in program type, dosage, or quality; all of which may affect program efficacy. Additionally, although the NSDUH can detect what type of youth attends violence prevention programs, it does not measure the motivations of these youth to participate. Another limitation is the use of self-report data; youth may over- or under-report their involvement in prevention programming. Additionally, the NSDUH does not sample youth in juvenile detention centers or other correctional institutions. It is possible that youth involved in corrections may participate in targeted violence prevention programs at higher rates than non-institutionalized youth; their lack of representation in the sample could lead to underestimation of participation rates. The NSDUH data also lack geocoding, which limited the assessment of neighborhood- or state-level factors. Future studies of more localized patterns of violence prevention program participation could address this limitation. Household surveys, including the NSDUH, have had decreased response rates in recent years.42 Although the NSDUH response rate has declined less than that of its peers,42 it is possible that youth in households that did not participate may differ from those who do, introducing endogeneity bias into the sample.

CONCLUSIONS

Results from the present study, conducted with data from a large national survey designed and implemented by SAMHSA, indicate youth violence prevention program participation rates decreased by nearly 30% between 2002 and 2016. Significant declines were observed among youth across age, gender, racial/ethnic, family income subgroups, but evidence also indicated that declines were most marked among youth aged 12–14 years and those in higher income families. Although rates of participation decreased significantly among those reporting recent use and no use of violence, declines were significantly greater among the majority of youth reporting no past-year fighting or attacks. Future research should focus on differences in participation at the city and state level and examine the characteristics and motivations of participants in programs designed to target violence. Such research could inform policymakers as to whether programs aimed at preventing violence are accessible to target populations and inform program design and implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the NIH under Award Number K01AA026645. The research was also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under Award Number R25 DA030310. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA, NIDA, or NIH.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1.

Survey adjusted prevalence estimates and 95% CI for annual adolescent (aged 12 to 17 years) participation in violence prevention programming in the U.S., by gender.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salas-Wright CP, Nelson EJ, Vaughn MG, Reingle Gonzalez JM, Córdova D. Trends in fighting and violence among adolescents in the United States, 2002–2014. Am J Public Health 2017;107(6):977–982. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics 2010;125(4):e778–e786. 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corso PS, Mercy JA, Simon TR, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. Am J Prev Med 2007;32(6):474–482. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall JE, Simon TR, Mercy JA, Loeber R, Farrington DP, Lee RD. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Expert Panel on Protective Factors for Youth Violence Perpetration. Am J Prev Med 2012;43(2):S1–S7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Preventing Youth Violence: An Overview of the Evidence 2015. http://apo.org.au/node/58219. Published October 27, 2015. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- 6.Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Maynard BR, Boutwell B. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric disorders among former juvenile detainees in the United States. Compr Psychiatry 2015;59:107–119. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benekos PJ, Merlo A V., Puzzanchera CM. Youth, race, and serious crime: examining trends and critiquing policy. Int J Police Sci Manag 2011;13(2):132–148. 10.1350/ijps.2011.13.2.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickett W, Craig W, Harel Y, et al. Cross-national study of fighting and weapon carrying as determinants of adolescent injury. Pediatrics 2005;116(6):e855–e863. 10.1542/peds.2005-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Todic J, Córdova D, Perron BE. Trends in the disapproval and use of marijuana among adolescents and young adults in the United States: 2002–2013. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2015;41(5):392–404. 10.3109/00952990.2015.1049493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipari RN. Trends in Adolescent Substance Use and Perception of Risk from Substance Use Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27656743. Accessed June 8, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughn MG, AbiNader MA, Salas-Wright CP, Oh S, Holzer KJ. Declining trends in drug dealing among adolescents in the United States. Addict Behav 2018;84:106–109. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maynard BR, Vaughn MG, Nelson EJ, Salas-Wright CP, Heyne DA, Kremer KP. Truancy in the United States: examining temporal trends and correlates by race, age, and gender. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;81:188–196. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughn MG, Nelson EJ, Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Holzer KJ. Abstention from drug use and delinquency increasing among youth in the United States, 2002–2014. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53(9):1468–1481. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1413392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffitt TE. Male antisocial behaviour in adolescence and beyond. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2(3):177–186. 10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins AM, Taylor T. The extent, predictors, and delinquency effects of gang joining among urban, suburban, and rural youth. J Crim Justice 2016;47:133–142. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watkins AM, Melde C. Gangs, gender, and involvement in crime, victimization, and exposure to violence. J Crim Justice 2018;57:11–25. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrado RR, DeLisi M, Hart SD, McCuish EC. Can the causal mechanisms underlying chronic, serious, and violent offending trajectories be elucidated using the psychopathy construct? J Crim Justice 2015;43(4):251–261. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLisi M Psychopathy as Unified Theory of Crime New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2016. 10.1057/978-1-137-46907-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaughn MG, Nelson EJ, Salas-Wright CP, Qian Z, Schootman M. Racial and ethnic trends and correlates of non-medical use of prescription opioids among adolescents in the United States 2004–2013. J Psychiatr Res 2016;73:17–24. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagan AA, Catalano RF. What works in youth violence prevention. Res Soc Work Pract 2013;23(2):141–156. 10.1177/1049731512465899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior. Am J Prev Med 2007;33(2):S130–S143. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrington DP, Gaffney H, Lösel F, Ttofi MM. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of developmental prevention programs in reducing delinquency, aggression, and bullying. Aggress Violent Behav 2017;33:91–106. 10.1016/j.avb.2016.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swaim RC, Kelly K. Efficacy of a randomized trial of a community and school-based anti-violence media intervention among small-town middle school youth. Prev Sci 2008;9(3):202–214. 10.1007/s11121-008-0096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelhor D, Vanderminden J, Turner H, Shattuck A, Hamby S. Youth exposure to violence prevention programs in a national sample. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38(4):677–686. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asscher JJ, Deković M, Van den Akker AL, Prins PJM, Van der Laan PH. Do extremely violent juveniles respond differently to treatment? Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2018;62(4):958–977. 10.1177/0306624X16670951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mack KA, Jones CM, Ballesteros MF. Illicit drug use, illicit drug use disorders, and drug overdose deaths in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas—United States. Am J Transplant 2017;17(12):3241–3252. 10.1111/ajt.14555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrington DP, Loeber R. Epidemiology of juvenile violence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2000;9(4):733–748. 10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Maynard BR. Religiosity and violence among adolescents in the United States. J Interpers Violence 2014;29(7):1178–1200. 10.1177/0886260513506279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salas-Wright CP, Lombe M, Vaughn MG, Maynard BR. Do adolescents who regularly attend religious services stay out of trouble? Results from a national sample. Youth Soc 2016;48(6):856–881. 10.1177/0044118X14521222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shook JJ, Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP. Exploring the variation in drug selling among adolescents in the United States. J Crim Justice 2013;41(6):365–374. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Peters KE. Who are truant youth? Examining distinctive profiles of truant youth using latent profile analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2012;41(12):1671–1684. 10.1007/s10964-012-9788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CDC. Conducting trend analyses of YRBS data www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/2015_yrbs_conducting_trend_analyses.pdf. Published June 2016. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 34.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haegerich TM, Dahlberg LL. Violence as a public health risk. Am J Lifestyle Med 2011;5(5):392–406. 10.1177/1559827611409127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Census Bureau. People in poverty by selected characteristics: 2013 and 2014 www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/252/pov_table3.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 37.Buka SL, Stichick TL, Birdthistle I, Earls FJ. Youth exposure to violence: prevalence, risks, and consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2001;71(3):298–310. 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Maynard BR. Violence and externalizing behavior among youth in the United States. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2014;12(1):3–21. 10.1177/1541204013478973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brookmeyer KA, Fanti KA, Henrich CC. Schools, parents, and youth violence: a multilevel, ecological analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2006;35(4):504–514. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, et al. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am Psychol 2003;58(6–7):466–474. 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Chung I-J, Guo J, Abbott RD, Hawkins JD. Protective factors against serious violent behavior in adolescence: a prospective study of aggressive children. Soc Work Res 2003;27(3):179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czajka JL, Beyler A. Declining Response Rates in Federal Surveys: Trends and Implications Washington, D.C.: Mathematica Policy Research; www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/declining-response-rates-in-federal-surveys-trends-and-implications-background-paper. Published 2016. Accessed December 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]