Abstract

Background and Aims

The inverse correlation between atmospheric CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) and stomatal frequency in many plants has been widely used to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels. However, apparent discrepancies exist among the obtained estimates. This study attempts to find a potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 concentrations by analysing the stomatal frequency of Quercus glauca (section Cyclobalanopsis, Fagaceae), a dominant species in East Asian sub-tropical forests with abundant fossil relatives.

Methods

Stomatal frequencies of Q. glauca from three material sources were analysed: seedlings grown in four climatic chambers with elevated CO2 ranging from 400 to 1300 ppm; extant samples collected from 14 field sites at altitudes ranging from 142 to 1555 m; and 18 herbarium specimens collected between 1930 and 2011. Stomatal frequency–pCO2 correlations were determined using samples from these three sources.

Key Results

An inverse correlation between stomatal frequency and pCO2 was found for Q. glauca through cross-validation of the three material sources. The combined calibration curves integrating data of extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens improved the reliability and accuracy of the curves. However, materials in the climatic chambers exhibited a weak response and relatively high stomatal frequency possibly due to insufficient treatment time.

Conclusions

A new inverse stomatal frequency–pCO2 correlation for Q. glauca was determined using samples from three sources. These three material types show the same response, indicating that Q. glauca is sensitive to atmospheric pCO2 and is an ideal proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. Quercus glauca is a nearest living relative (NLR) of section Cyclobalanopsis fossils, which are widely distributed in the strata of East Asia ranging from the Eocene to Pliocene, thereby providing excellent materials to reconstruct the atmospheric CO2 concentration history of the Cenozoic. Quercus glauca will add to the variety of proxies that can be widely used in addition to Ginkgo and Metasequoia.

Keywords: Stomatal density, stomatal index, pCO2-elevated experiment, altitudinal gradient, historical specimen, ring-cupped oak, Quercus glauca, proxy for palaeo-CO2

INTRODUCTION

Reconstructing the deep-time dynamics of atmospheric CO2 concentrations has been the subject of a great deal of attention because this greenhouse gas plays an important role in driving and amplifying global climate change (McElwain et al., 2016). For example, the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) is well known as an intense interval of global warming linked to a dramatically elevated CO2 concentration (Zachos et al., 2005), while the Eocene–Oligocene transition is characterized by a rapid temperature drop that was probably associated with a significant CO2 decrease (Zanazzi et al., 2007; Goldner et al., 2014). Other than measuring ice cores from the past 800 000 years (Lüthi et al., 2008), there is no direct method to determine palaeoatmospheric CO2 (palaeo-CO2) concentrations. Pre-ice core CO2 concentration estimates are achieved by biogeochemical models (Berner and Kothavala, 2001; Berner, 2006) and various independent palaeobotanical and geochemical proxies, such as palaeosols (Ekart et al., 1999; Myers et al., 2012), phytoplankton (Pagani et al., 2005; Seki et al., 2010), marine carbonate (Tripati et al., 2009; Seki et al., 2010) and fossil stomata (Royer et al., 2001b; Kürschner et al., 2008; Franks et al., 2014). These methods have provided numerous palaeo-CO2 estimates throughout the Phanerozoic Eon (Royer, 2006; Breecker et al., 2010); however, there appear to be considerable discrepancies and large variabilities between estimates obtained by these different approaches (Royer et al., 2001a; Beerling and Royer, 2011).

Because their main function is to exchange gas between plants and the atmosphere, stomata respond directly to atmospheric CO2 (Lake et al., 2001, 2002; Miyazawa et al., 2006; Mizutani and Kanaoka, 2018); thus fossil stomata may conceal the atmospheric CO2 in the geological past, especially in the Cenozoic Era (Royer et al., 2001a; Beerling and Royer, 2002a; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2011). It follows that stomata-based methods have been used extensively to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels. Stomata-based methods include both empirical approaches (van der Burgh et al., 1993; McElwain and Chaloner, 1996; Beerling and Royer, 2002a; Kürschner et al., 2008; Retallack, 2009; Doria et al., 2011; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2011; Barclay and Wing, 2016) and mechanistic models (Wynn, 2003; Konrad et al., 2008; Grein et al., 2011; Franks et al., 2014). Empirical methods are generally based on the close correlation between atmospheric CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) and leaf stomatal frequency [expressed as stomatal density (SD) or stomatal index (SI)] that has been observed in many C3 plants (Woodward, 1987; McElwain, 1998; Kürschner et al., 2001; Royer, 2001; Beerling and Royer, 2002a; Kouwenberg et al., 2003; Barclay et al., 2010; Bai et al., 2015; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2019). Alternative mechanistic models have been developed in recent decades. These models infer palaeo-CO2 levels from photosynthetic gas exchange and/or water availability measurements (Wynn, 2003; Konrad et al., 2008; Franks et al., 2014). More recently, both empirical stomata-based proxies and mechanistic models have been applied to the same fossil leaves; these studies have shown that these two methods provide comparable estimates of palaeo-CO2 concentrations (Barclay and Wing, 2016; Montañez et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017). Since empirical stomata methods are simpler than mechanistic models, because they only require SD or SI measurements from fossil leaves, they remain the most widely used proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels (McElwain and Steinthorsdottir, 2017).

Woodward (1987) was the first to propose that SD decreases with increasing CO2 levels, and Woodward and Bazzaz (1988) showed that stomatal frequency responds to atmospheric pCO2 (Pa) but not to CO2 mole fraction (μmol mol–1) or concentration (ppm). Since then, an increasing number of studies have used the stomatal frequency (SF)–pCO2 relationships to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels (Kürschner et al., 2001, 2008; Beerling and Royer, 2002a, b; Bai et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2015; Barclay and Wing, 2016; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2019). In empirical stomata methods, the SF–pCO2 relationship of a fossil’s nearest living relative (NLR) must be established, before the fossil’s stomata can be used to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels (Royer, 2001; Steinthorsdottir et al., 2016). This is because the SF–pCO2 correlation is species specific: while the majority of plant species studied to date show an inverse correlation, some have no significant relationship and a minority exhibit a positive correlation (Woodward and Kelly, 1995; Royer, 2001; Haworth et al., 2010b). Materials from three different sources can be used to determine the SF–pCO2 relationship of an NLR species: (1) experimental plants grown under elevated pCO2 in greenhouses; (2) historical herbarium specimens collected over an extended period of time; and (3) specimens collected along an altitudinal gradient (Haworth et al., 2010b; Hu et al., 2015). So far, greenhouse and herbarium materials (Woodward, 1987; van der Burgh et al., 1993; Retallack, 2001; Royer et al., 2001b; Greenwood et al., 2003; Kouwenberg et al., 2003; Barclay et al., 2010; Haworth et al., 2011a) have been used much more frequently than altitudinal samples (McElwain, 2004; Eide and Birks, 2006; Kouwenberg et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2015).

However, all three sources of material have inherent limitations. (1) Experimental greenhouse materials may not capture the long-term, genetic responses of plants to slow environmental changes (Woodward, 1988; Beerling and Chaloner, 1993a; McElwain and Chaloner, 1995). Plants may exhibit incomplete phenotypic adaptation to the elevated pCO2 (Barclay and Wing, 2016) and, because of the limited pCO2 gradient in the greenhouse, only a trend of stomatal frequency response can be obtained, which is inadequate to construct a calibration curve for palaeo-CO2 estimates. (2) Use of herbarium materials may be limited by the availability of historical specimens, and the ensuing paucity of data may lead to larger errors. (3) Altitudinal materials are valuable only if the targeted plant species is distributed over a large altitudinal gradient and altitude-induced environmental variations may affect stomatal frequency. Moreover, both herbarium and altitudinal materials only capture sub-ambient to ambient pCO2, and thus are not particularly useful for estimating palaeo-CO2 during greenhouse intervals. Indeed, previous studies have shown inconsistent stomatal frequency responses to atmospheric pCO2 in the same plant species (Beerling and Chaloner, 1993b; Atkinson et al., 1997; Beerling, 1997; Lin et al., 2001; Eide and Birks, 2006), probably reflecting the inherent weaknesses of the material source type used. To reduce their inherent bias and to obtain a reliable correlation, combined use of all three material types is highly advisable. So far, very few studies have attempted this approach. Eide and Birks (2006) used the three material types to investigate the relationship between stomatal frequency and pCO2 in Betula pubescens but found no clear SF–pCO2 relationship, leading them to conclude that B. pubescens was unsuitable for palaeo-CO2 reconstruction. Clearly, more studies that combine all three types of materials are needed.

To date, the most widely used proxies to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels have been Ginkgo biloba and Metasequoia glyptostroboides, since both species exhibit ideal inverse SF–pCO2 correlations and have abundant fossil relatives stretching as far back as the Cretaceous Period (Retallack, 2001, 2009; Royer et al., 2001b; Beerling and Royer, 2002a; Quan et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2010; Doria et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Barclay and Wing, 2016). Other species, including other conifers (Passalia, 2009; Steinthorsdottir and Vajda, 2013; Liu et al., 2016), cycads (McElwain et al., 1999; Haworth et al., 2011b), Quercus petraea (van der Burgh et al., 1993; Kürschner et al., 1996), Q. guyavifolia (Hu et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016), members of the Lauraceae (McElwain, 1998; Greenwood et al., 2003; Kürschner et al., 2008) and Betula species (Finsinger and Wagner-Cremer, 2009), have been used as proxies much less frequently because of their limited number of fossil relatives. Clearly, identification of additional proxies that are sensitive to atmospheric pCO2 and also have numerous fossil relatives is highly desirable.

The ring-cupped oaks [Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis (Oerst.) Benth. & Hook. f., Fagaceae] (Denk et al., 2017), which today dominate sub-tropical East Asian forests (Zhou, 1993; Xu et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2018), have rich fossil records in the Cenozoic sediments of East Asia ranging from the Eocene to Pliocene Epochs (e.g. Huzioka and Takahasi, 1970; Writing Group of Cenozoic Plants of China, 1978; Li, 2010; Shi, 2010; Xing et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Barrón et al., 2017); therefore, they are excellent potential candidates for reconstructing the historical atmospheric CO2 concentration of the Cenozoic Era. In this study, we selected Q. glauca Thunb., a dominant species in East Asian sub-tropical forests and one of the fossils of the NLRs of section Cyclobalanopsis, to determine how the stomatal frequency of Q. glauca responds to pCO2 variation using all three material sources, i.e. seedlings grown in climatic chambers under elevated pCO2; extant field samples collected along an altitudinal gradient; and historical herbarium specimens. The overarching aim of this study was to determine the suitability of Q. glauca as a proxy for palaeo-CO2 concentrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design in the climatic chambers

Quercus glauca seeds were collected from four different altitudes. The altitudes of vouchers DH359, DH358, DH349 and DH360 are 240, 314, 715 and 1940 m, respectively (Supplementary Data Table S1). Seeds were germinated in sandy beds to young seedlings with two or three leaves (Fig. 1A) and then transplanted to pots. Seedlings in pots were grown in four walk-in climatic chambers (Grandcool, Beijing, China) at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (21°55′2.9″N, 101°16′39.7″E, altitude 548 m) with an atmospheric control of ambient air (approx. 400 ppm CO2) or ambient air with elevated CO2 concentrations (approx. 700, 1000 and 1300 ppm). All other growth conditions in the four chambers were kept the same: during the day (08.00–18.00 h) the temperature was 25 °C with a light intensity of approx. 300 μmol m–2 s–1; during the night (18.00–08.00 h) the temperature was 18 °C and dark; the relative humidity was maintained at 70 %; 300 mL of water was given every 3 d. The ranges of recorded error in CO2 concentration, temperature and relative humidity around the treatment set points are listed in Supplementary Data Table S2. Only leaves growing from newly developed buds after transfer of the seedlings into the climatic chambers were recorded.

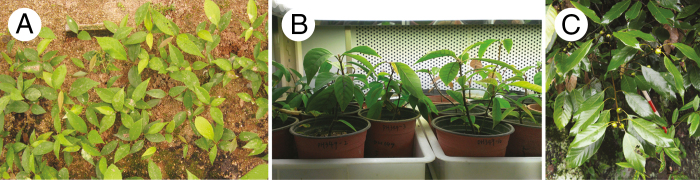

Fig. 1.

Photos of Quercus glauca in experimental and natural field conditions. (A) Young seedlings grown from seeds in sandy beds; (B) plants grown in the chambers for 1 year (photographed by Dr Li Wang); (C) plants in the natural field.

Plants were grown under two types of treatments in the four chambers: (1) plants collected from the same site were grown in different chambers under four CO2 concentrations from 400 to 1300 ppm, i.e. pCO2 approx. 38.035, 66.562, 95.088 and 123.614 Pa, respectively, in the four chambers (Supplementary Data Table S3); and (2) plants collected from different altitudes were grown in the same chamber under the same CO2 concentration (700 or 1000 ppm, i.e. pCO2 approx. 66.562 and 95.088 Pa; Supplementary Data Table S4). Vouchers DH349 and DH360 were used for treatment 1; vouchers DH359, DH358, DH349 and DH360 were used for treatment 2. Experimental plants grown in the chambers (Fig. 1B) appeared quite healthy when compared with those from the field (Fig. 1C). After approx. 1 year (from 1 January 2013 to 15 January 2014) in the climatic chambers, by which time plants had 8–20 leaves, the uppermost mature leaves, which received full irradiance, were sampled. Twenty-five individuals for each voucher were grown in each chamber and, after 1 year, 5–19 individuals were still alive; 2–4 leaves were collected from each of the surviving individuals; however, only one leaf was collected from some individuals which grew very slowly.

Collection of extant altitudinal samples

Altitudinal samples of Q. glauca were collected from five individuals at each of 14 sites with elevations ranging from 142 to 1555 m, which represents a pCO2 of 32.886–38.838 Pa (Supplementary Data Table S5; Fig. 2). Four sun and shade leaves were collected from each individual tree to account for stomatal frequency variation (Poole and Kürschner, 1999; Beerling and Royer, 2002a), since light intensity may have a positive effect on stomatal frequency (Royer, 2001; McElwain, 2004; Kouwenberg et al., 2007).

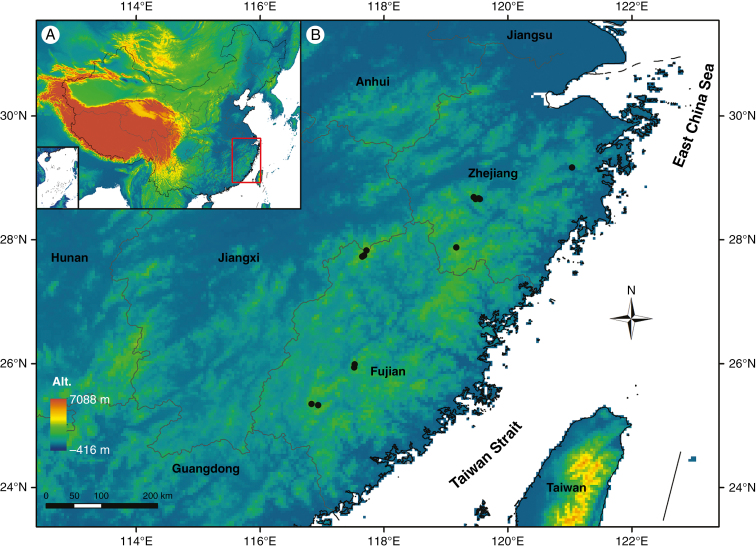

Fig. 2.

Locations of 14 sampling sites (black points; B) in south-eastern China (A) for extant altitudinal samples of Quercus glauca.

Collection of historical herbarium specimens

Quercus glauca historical herbarium specimens that spanned the time period of 1930–2005 were obtained from the Herbarium of Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KUN). We selected specimens collected from south-western China at similar altitudes (1000–1680 m) (Supplementary Data Table S6) to minimize altitude-induced error. Extant sample DH343, collected in the field, extended the time period to 2011. These samples represent a pCO2 of 26.187–33.862 Pa (Supplementary Data Table S6). Two to three leaves for each target specimen were used.

Cuticle preparation and SD/SI counts

Mature leaves were chosen for cuticle preparation, which followed the methods of Stace (1965) and Poole and Kürschner (1999), and were photographed under a light microscope (Leica DM 1000) attached to a Leica DFC 295 camera. To minimize variability, fields of view were concentrated near the mid-lamina region in the intercostals (Poole et al., 1996). The size of the images for SD (number of stomata per mm2) and SI (proportion of stomata to the total number of epidermal cells) counts was approx. 0.1643 mm2. The leaves of Q. glauca are hypostomatous (Deng et al., 2014); thus, stomatal and epidermal cell counts were made on the abaxial surface. The software package ImageJ version 1.42q was used for SD/SI counts.

For samples grown in the climatic chambers, three microscope fields per leaf were counted. The stomatal frequency of samples from the same voucher in the same chamber was averaged and the standard deviation was calculated. For extant altitudinal samples, three microscope fields were counted per leaf, resulting in 60 SD/SI counts (5 individuals × 4 leaves × 3 counts) for each of the 14 sites for both sun and shade leaves. For historical herbarium specimens, five microscope fields per leaf were counted, thus 10–15 counts were made for each specimen. Previous studies have showed that in Quercus sun leaves have a trait of straight to rounded epidermal cell walls, whereas shade leaves exhibit a pronounced undulation of the epidermal cell walls (Kürschner, 1997; Hu et al., 2015), and on this basis only sun leaves from the historical herbarium specimens were chosen for SD/SI counts. In fact, we found that sun leaves of Q. glauca were much easier to obtain than shade leaves in the herbarium, possibly because leaves from outer branches were more easily collected.

All cuticular slides were deposited at the Laboratory of Palaeoclimate Change and Plant Evolution Research Group in the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The protocols for cuticle preparation, as well as stomatal analysis for extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens, are detailed in Hu et al. (2015).

Data analysis

For samples in climatic chambers, the changes in SD and SI values under the two treatment types were illustrated as histograms using R. Levene’s test of equality of error variance was conducted and showed that the error variance of SD or SI was equal across treatment 1 (plants from the same voucher under four pCO2) or treatment 2 (plants from four different altitudes under the same pCO2), except for the SD from voucher DH349 in treatment 1. Differences in the SD or SI values across treatment 1 or 2 were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference (LSD) tests, which were applied to each of the data sets with equal error variance. For the SD from voucher DH349 with unequal error variance, differences were compared using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA (k samples).

For extant altitudinal samples, calibration curves of SD or SI vs. pCO2 for sun and shade leaves were constructed. Atmospheric pCO2 used in these calibration curves were calculated from the different altitudes using eqn (1) (Beerling and Royer, 2002a, derived from Jones, 1992):

| (1) |

where p1 and p2 are the CO2 partial pressures (Pa) at sea-level and at the site, respectively; R is the gas constant (8.3144 Pa m3 mol–1 K–1); T is the mean annual temperature (K) of the range in elevation; MA is the molecular weight of air (0.028964 kg mol–1); g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m s–2); and elev (p2) is the elevation (m) of the site. T was obtained by inputting the latitude, longitude and elevation of each site into CLAMP Climate Related Diagnostics, available from the BRIDGE website (https://www.paleo.bristol.ac.uk/ummodel/scripts/html_bridge/clamp_UEA.html). Because stomatal frequency responds to CO2 partial pressure, the approximate values of pCO2 in the four climatic chambers were also calculated (Supplementary Data Tables S3, S4) using eqn (1).

Calibration curves of SD or SI vs. pCO2 for historical herbarium specimens were also constructed. Since the altitudes of the historical herbarium specimens were relatively high, from 1000 to1680 m, atmospheric pCO2 at these altitudes was calculated by applying historical levels of atmospheric CO2 at sea level of the collection time and altitudes to eqn (1). Historical atmospheric CO2 concentrations at sea level before 1958 AD were obtained from Etheridge et al. (1996) and afterwards from the CO2.Earth website (https://www.co2.earth/).

All calibration curves were generated using simple linear regression analysis, using R version 3.0.2 (http://www.R-project.org). Paired-samples t-tests were conducted to test the difference of the stomatal frequency between sun and shade leaves of the extant altitudinal samples; analysis of covariance was conducted to test the differences in slopes and y-intercepts of the constructed curves of sun and shade leaves as well as historical herbarium specimens by using SPSS Statistics version 19.0 (http://www.spss.com.cn). In this study, significance is defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

pCO2-elevated experiment

Quercus glauca samples that were collected from two sites with different altitudes (vouchers DH349 and DH360) and grown in climatic chambers under CO2 enrichment of 400–1300 ppm (treatment 1) displayed a reduction in mean SI from 13.1 (14.3) % to approx. 12 % (Fig. 3C, D; Supplementary Data Table S3); however, this inverse response was rather weak and the mean SD showed no apparent significant change with elevated pCO2 (Fig. 3A, B).

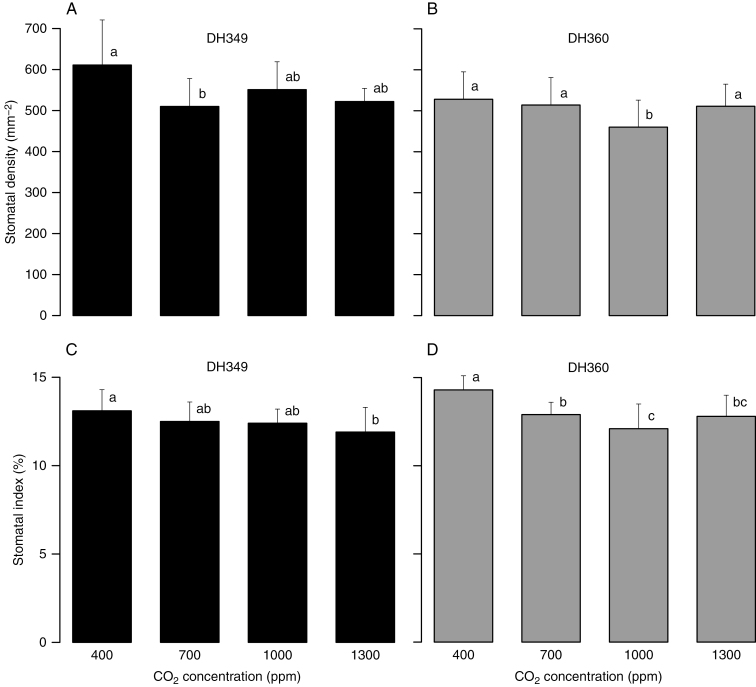

Fig. 3.

Changes in stomatal frequency (A and B, stomatal density; C and D, stomatal index) for Quercus glauca (vouchers DH349 and DH360) under four CO2 concentration gradients. Error bars represent + 1 s.d. Different letters above the histograms indicate a significant difference.

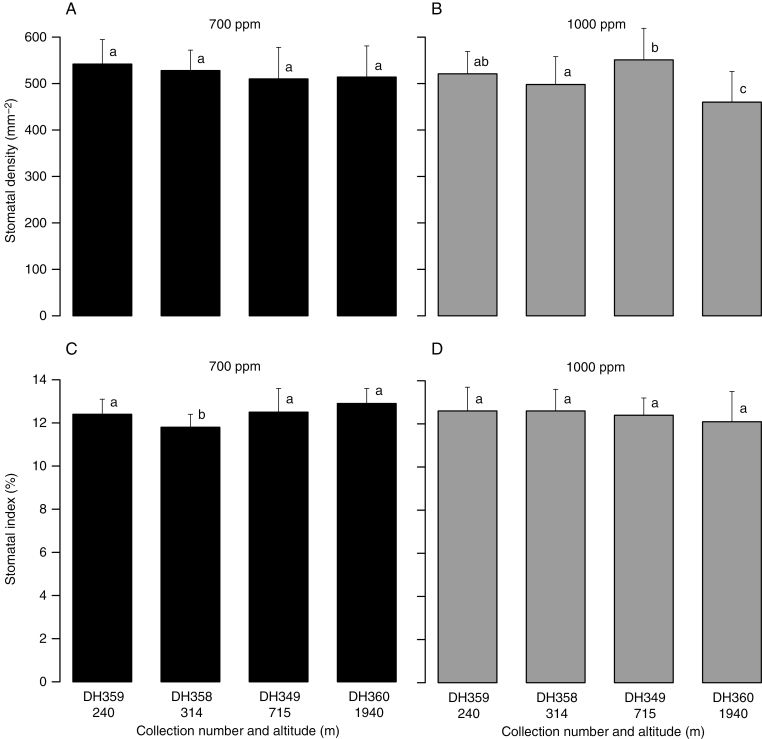

Quercus glauca samples collected from four different altitudes but modulated under the same pCO2 for 1 year (treatment 2) displayed a similar SI (Fig. 4C, D; Supplementary Data Table S4). In particular, the SI values of the four vouchers in the chamber with a CO2 concentration of 1000 ppm (pCO2 95.088 Pa) varied only from 12.1 to 12.6 %. The SD was more variable than the SI; the SD of the samples grown under 700 ppm CO2 concentration (pCO2 66.562 Pa) exhibited similar values, but those grown under 1000 ppm CO2 showed no regular response (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 4.

Changes in stomatal frequency (A and B, stomatal density; C and D, stomatal index) for Quercus glauca collected from different altitudes and treated under the same CO2 concentration for 1 year. Histograms were labelled as the collection numbers and altitudes. Error bars represent + 1 s.d. Different letters above the histograms indicate a significant difference.

Stomatal frequency of Quercus glauca from altitudinal and herbarium samples

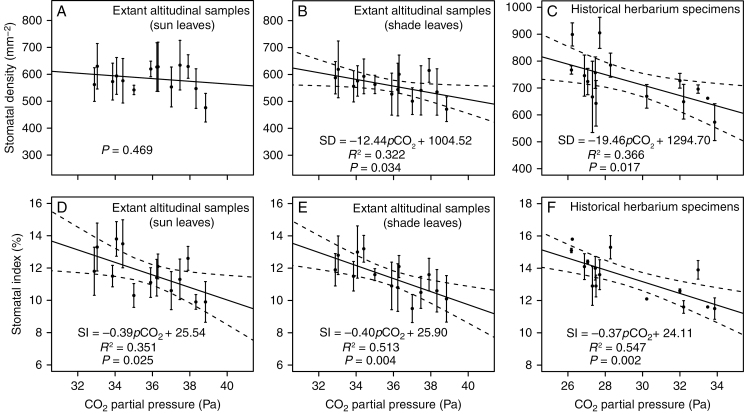

The calibration curves show a significant inverse linear correlation between SI and atmospheric pCO2 for both sun and shade leaves of Q. glauca collected along an altitudinal gradient (Fig. 5D, E; Supplementary Data Table S5). There was a slight decrease of SD with increasing pCO2 in sun leaves, but this was not significant (Fig. 5A). However, a significant inverse linear relationship between SD and pCO2 was found in shade leaves (Fig. 5B). Moreover, there was no difference in SI between sun and shade leaves (P = 0.252). Further, the slopes (P = 0.933) and y-intercepts (P = 0.548) of their constructed curves were not different. However, the SD in sun leaves was slightly higher than that of shade leaves (P = 0.031).

Fig. 5.

The relationship between stomatal frequency (A–C, stomatal density; D–F, stomatal index) and CO2 partial pressure of Quercus glauca sun (A, D) and shade (B, E) leaves of extant altitudinal samples, and from historical herbarium specimens (C, F). Error bars represent ± 1 s.d. The solid line indicates the best fit in a classical regression analysis. Dashed lines are 95 % confidence limits.

Similar to the response of the extant altitudinal samples, the SD and SI of historical herbarium specimens showed a significant inverse correlation with atmospheric pCO2 (Fig. 5C, F; Supplementary Data Table S6).

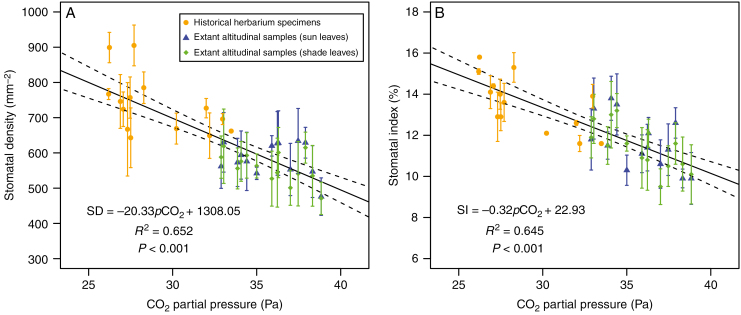

There was no significant difference in the slopes and y-intercepts of SD/SI–pCO2 curves between extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens (P = 0.497 and 0.171, respectively, for slope and y-intercept comparison of SD–pCO2 curves; P = 0.969 and 0.441, respectively, for slope and y-intercept comparison of SI–pCO2 curves). Thus, the SD/SI of extant altitudinal samples (sun and shade leaves) and historical herbarium specimens were combined to generate calibration curves (Fig. 6), which were of higher quality (R2 = 0.652 for SD–pCO2 curve; R2 = 0.645 for SI–pCO2 curve) than the individual curves.

Fig. 6.

Calibration curves of Quercus glauca constructed by combining stomatal frequency (A, stomatal density; B, stomatal index) of extant altitudinal samples (sun and shade leaves) and historical herbarium specimens (see key). Error bars represent ± 1 s.d. The solid line indicates the best fit in a classical regression analysis. Dashed lines are 95 % confidence limits.

DISCUSSION

An inverse response in pCO2-elevated experiment

Quercus glauca seedlings grown in climatic chambers under four different CO2 concentrations, ranging from 400 to 1300 ppm (treatment 1), showed an inverse relationship between stomatal frequency and pCO2, while seedlings collected from different altitudes and grown for 1 year under the same pCO2 (treatment 2) mostly displayed a similar SI. Both results point to pCO2 as the main environmental factor controlling stomatal frequency.

Improved SF–pCO2 relationship derived from three material sources

A significant inverse correlation between stomatal frequency and pCO2 was found for Q. glauca from the three material sources, namely seedlings grown under elevated pCO2, extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens. These results indicate that Q. glauca is sensitive to changes of pCO2 and is an ideal proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. Further, our results confirm that combined use of these three material sources, to investigate the SF–pCO2 relationship of a plant species, can overcome the limitations inherent to each material source (Woodward, 1988; Beerling and Chaloner, 1993a; McElwain and Chaloner, 1995; Hu et al., 2015; Barclay and Wing, 2016). These limitations have been highlighted by previous studies, using only one material source, which have reported different SF–pCO2 relationships for the same species. For example, Pinus sylvestris showed a reduction in SD under a pCO2-elevated treatment (Beerling, 1997; Lin et al., 2001), but Eide and Birks (2006) did not find a statistically significant relationship for both historical herbarium specimens and pCO2-elevated experiments; Beerling and Chaloner (1993b) showed an inverse SD–pCO2 correlation for Q. robur using historical herbarium specimens, while Atkinson et al. (1997) reported increased SD in this species under elevated pCO2. However, until now, only a handful of studies have attempted the combined use of all three material sources. Using this approach, Royer et al. (2001b) and Barclay and Wing (2016) were able to generate high-quality SI–CO2 inverse curves for Ginkgo and/or Metasequoia; however, they used only one or two field sampling sites to complement the historical herbarium data sets, not a series collected along an altitudinal gradient.

In this study, the three material types of Q. glauca were analysed independently yet produced comparable results. This confirms that pCO2 is the main factor influencing stomatal frequency not only in historical herbarium specimens but also in extant altitudinal samples. This, in turn, demonstrates that extant field samples collected along an altitudinal gradient are also a reliable, yet hitherto underutilized, material source with great application potential. To date, only a few studies have used extant altitudinal samples to investigate the relationship between stomatal frequency and pCO2 (McElwain, 2004; Eide and Birks, 2006; Kouwenberg et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2015). This probably reflects the fact that only a limited number of plant species are distributed over a wide enough altitudinal range. Nevertheless, our study clearly demonstrates that combining extant altitudinal samples with historical herbarium specimens can be advantageous, as it expands the range of pCO2 and thus improves the reliability and accuracy of SF–pCO2 curves.

Quercus glauca is one of the NLRs of section Cyclobalanopsis fossils which are widely distributed in the strata of East Asia ranging from the Eocene to Pliocene Epochs (Huzioka and Takahasi, 1970; Guo, 1978, 2011; Writing Group of Cenozoic Plants of China, 1978; Zhou, 1999; Xiao et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2009; Li, 2010; Shi, 2010; Xing et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2016; Barrón et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Linnemann et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2018). These successive fossil records provide ideal materials to reconstruct the atmospheric CO2 concentration history of the Cenozoic Era by applying the stomatal frequencies of closely related fossils to the constructed SF–pCO2 curves of Q. glauca. Thus, these fossils will considerably increase the range of optimal proxies to estimate palaeo-CO2 levels, beyond Ginkgo and Metasequoia. Recently, a new positive SF–pCO2 relationship has been determined in Q. guyavifolia, the NLR of Q. preguyavifolia fossils (Hu et al., 2015) which coexisted with section Cyclobalanopsis fossils in many floras (Xing et al., 2012; Hu, 2013; Xu, 2016). Reconstructing palaeo-CO2 concentrations using these two coexisting taxa with contrasting responses to pCO2 (inverse in Q. glauca and positive in Q. guyavifolia) will provide independent results to cross-check the palaeo-CO2 levels within the same time period.

A weak response to elevated pCO2

Although the stomatal frequency of Q. glauca grown in climatic chambers showed an inverse response to atmospheric pCO2, this response was rather weak. For example, voucher DH360 displayed higher SD and SI in the 700 ppm CO2 treatment than in the 1000 ppm CO2 treatment (P < 0.05), while voucher DH349 showed similar SD and SI between the 700 and 1000 ppm CO2 treatments (P > 0.05) (treatment 1, Fig. 3). Additionally, SD of the samples from four different altitudes was higher in the 700 ppm CO2 treatment than that in the 1000 ppm CO2 treatment (P < 0.05) (treatment 2); however, there were no difference in SI between the two treatments (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4). These results indicate that while some plants in the chambers responded to the pCO2-elevated treatment, others did not. Moreover, the SD and SI of these seedlings grown under elevated pCO2 did not exhibit obviously lower values than those of historical herbarium specimens and extant altitudinal samples; in fact, their SD values (500–550 mm–2) were similar to those of the extant altitudinal samples collected from a low altitude range (142–552 m, i.e. pCO2 37.007–38.838 Pa; Supplementary Data Table S5) and their SI values (12–13 %) were similar to the median value of the SI range for both historical herbarium specimens and extant altitudinal samples (Fig. 6; Supplementary Data Tables S5 and S6).

A possible explanation for the weak response and relatively high SD and SI values in the climatic chambers is incomplete phenotypic adaptation to elevated pCO2. A previous study also observed relatively high SI in G. biloba grown at 1500 ppm CO2; additionally, they found malformed stomata and high SI variance among these leaves, suggesting incomplete anatomical adjustment to elevated pCO2 (Barclay and Wing, 2016). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that plants often need multi-year (at least two growing seasons) pCO2-elevated treatments for their stomatal frequency to show a response (Royer, 2003; Overdieck and Strassemeyer, 2005; McElwain and Steinthorsdottir, 2017), and Hincke et al. (2016) showed that amplified adjustment of stomatal parameters in Betula nana occurred only in the second year of experimental pCO2 exposure. Therefore, it is likely that the weak response and relatively high SD and SI values of Q. glauca reported here are due to insufficient exposure (<1 year) of the experimental plants to elevated pCO2.

In addition, unsatisfactory simulation of natural field conditions within the climatic chambers may also have contributed to the weak response and relatively high SD and SI values observed here. We used a light intensity of 300 μmol m–2 s–1, because of technical limitations of our climatic chambers; this light intensity may be too low for Q. glauca, as this species occurs in sub-tropical East Asian forests (Zhou, 1993; Xu et al., 2015). Because of these two potential problems with our experimental design, we excluded the experimental data set from the calibration curves of SF and pCO2 for Q. glauca.

SD vs. SI and sun vs. shade leaves

Our results confirm that SI is more reliable than SD. Previous work has shown that SD is area dependent and susceptible to environmental factors that affect epidermal cell expansion, such as temperature, water stress and humidity (Kürschner et al., 1996; Royer, 2001; Sun et al., 2003; Haworth et al., 2010a); however, SI can reduce the effect of these environmental factors. It follows that SI is a more precise parameter for investigating the SF–pCO2 relationship and a more reliable proxy for palaeo-CO2 estimates (McElwain, 2005; Kouwenberg et al., 2007). Indeed, in this study, we showed that the SI, but not the SD, of sun leaves from extant altitudinal samples had a significant inverse response to atmospheric pCO2, and that the SI of seedlings in the climatic chambers exhibited a more pronounced response to elevated pCO2 than their SD. These results confirm that SD varies more than SI and that it is, therefore, less reliable than SI for palaeo-CO2 reconstruction. It is worth noting, however, that in cases when fossil leaves are not well preserved thus rendering SI analysis impossible, SD remains a viable option for palaeo-CO2 reconstruction, although it may give rise to error.

Previous studies have shown that in many species the stomatal frequency of sun leaves is higher than that of shade leaves (Kürschner, 1997; Wagner, 1998; Kouwenberg et al., 2007) due to the positive effect of light intensity on stomatal frequency (Lake et al., 2001, 2002). Our study shows that Q. glauca sun leaves had a higher SD than shade leaves but had a similar SI. Since SD is more variable than SI, as also demonstrated by the exceptional lack of significant correlation between pCO2 and SD of sun leaves (Fig. 5A), we conclude that light intensity has only a negligible effect on the stomatal frequency of Q. glauca. Therefore, it is feasible to combine sun and shade leaves together with historical herbarium specimens to generate SF–pCO2 curves for this species. When applying these calibration curves to related fossils for estimation of palaeo-CO2 concentrations, both sun and shade fossil leaves could also be used together. This represents an additional advantage of Q. glauca as a potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 concentrations. In species where the stomatal frequency of sun leaves differs from that of shade leaves, it is important to distinguish between the two: combining only sun leaves from extant altitudinal samples with sun leaves from historical herbarium specimens results in more accurate calibration curves; it is also necessary to distinguish fossil sun and shade leaves for palaeo-CO2 estimates.

Conclusions

We have shown a statistically significant inverse correlation between atmospheric pCO2 and stomatal frequency in Q. glauca using samples from three sources: seedlings grown in climatic chambers under elevated pCO2, extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens. These three types of samples were analysed independently, thus compensating for the disadvantages of each individual material type and allowing for cross-validation of different material sources. These three material types show the same response, indicating that Q. glauca is sensitive to atmospheric pCO2 and is a potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. The combined calibration curves, which integrated the data from extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens, showed higher accuracy than the individual curves. Thus, we suggest that samples collected along an altitudinal gradient should be utilized more often to investigate the SF–pCO2 correlation and that combining both extant altitudinal samples and historical herbarium specimens will improve the reliability and accuracy of the calibration curves and, thus, palaeo-CO2 estimations.

The numerous Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis fossils from the Eocene to Pliocene Epochs in eastern Asia provide ideal materials to estimate the atmospheric CO2 concentration history of the middle to late Cenozoic Era. However, although the seedlings of Q. glauca (the NLR of section Cyclobalanopsis fossils) from our pCO2-elevated experiment showed an inverse SF–pCO2 relationship, they displayed a weak response and relatively high SD and SI values. This is likely to be due to incomplete phenotypic adjustment to elevated pCO2 because of too short exposure time (only 1 year) and unsatisfactory simulation of natural field conditions within the climatic chambers. Clearly, longer exposure to elevated pCO2, >2 years, and better simulation of natural field conditions are recommended for future studies of stomatal frequency in tree species under elevated pCO2.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: voucher, location and altitude of Q. glauca seedlings in the climatic chambers. Table S2: the treatment set points and range of recorded points in CO2 concentration, temperature, relative humidity and light intensity in the climatic chambers. Table S3: stomatal density and stomatal index of Q. glauca under four pCO2 gradients in the climatic chambers. Table S4: stomatal density and stomatal index of Q. glauca collected from different altitudes under the same pCO2 in the climatic chambers. Table S5: location, altitude, pCO2, stomatal density and stomatal index of Q. glauca sun and shade leaves where extant altitudinal samples were collected. Table S6: collection time, location, altitude, pCO2, stomatal density and stomatal index of Q. glauca sun leaves from historical herbarium specimens.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant no. 41702027 to J.J.H.], a Joint Fund from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Yunnan Provincial Government [grant no. U1502231 to Z.K.Z.] and the NSFC-NERC (Natural Environment Research Council of the UK) joint research program [grant no. 41661134049 to T.S.].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Professor Min Deng for assistance in collecting extant altitudinal samples, the Herbarium of Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KUN) for providing historical herbarium specimens, and the Central Laboratory of Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing the climatic chambers for experiments. We also thank Yong Zeng for planting the seedlings, Sheng-Lin Zi, Li Wang, Shu-Feng Li, Mei Sun, Jian Huang, He Xu, Xiao-Qing Liang and Jian-Wei Zhang for taking care of the seedlings, Hai Zhu and Lin-Bo Jia for assistance in drawing Fig. 2, and Cheng-Hang Huang, De-Guang Yang and Jing-Wen Wang from Yunnan Agricultural University for their assistance in cuticle preparation and stomatal counts.

LITERATURE CITED

- Atkinson CJ, Taylor JM, Wilkins D, Besford RT. 1997. Effects of elevated CO2 on chloroplast components, gas exchange and growth of oak and cherry. Tree Physiology 17: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai YJ, Chen LQ, Ranhotra PS, Wang Q, Wang YF, Li CS. 2015. Reconstructing atmospheric CO2 during the Plio-Pleistocene transition by fossil Typha. Global Change Biology 21: 874–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay RS, Wing SL. 2016. Improving the Ginkgo CO2 barometer: implications for the early Cenozoic atmosphere. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 439: 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay RS, McElwain JC, Sageman BB. 2010. Carbon sequestration activated by a volcanic CO2 pulse during Ocean Anoxic Event 2. Nature Geoscience 3: 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Barrón E, Averyanova A, Kvaček Z, et al. 2017. The fossil history of Quercus. In: Gil-Pelegrín E, Peguero-Pina JJ, Sancho-Knapik D, eds. Oaks physiological ecology. Exploring the functional diversity of genus Quercus L. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 39–105. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ. 1997. Carbon isotope discrimination and stomatal responses of mature Pinus sylvestris L. trees exposed in situ for three years to elevated CO2 and temperature. Acta Oecologica 18: 697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Chaloner WG. 1993. a. Evolutionary responses of stomatal density to global CO2 change. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 48: 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Chaloner WG. 1993. b. The impact of atmospheric CO2 and temperature change on stomatal density: observations from Quercus robur lammas leaves. Annals of Botany 71: 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Royer DL. 2002. a. Fossil plants as indicators of the phanerozoic global carbon cycle. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 30: 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Royer DL. 2002. b. Reading a CO2 signal from fossil stomata. New Phytologist 153: 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Royer DL. 2011. Convergent Cenozoic CO2 history. Nature Geoscience 4: 418–420. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. 2006. GEOCARBSULF: a combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70: 5653–5664. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA, Kothavala Z. 2001. GEOCARB III: a revised model of atmospheric CO2 over phanerozoic time. American Journal of Science 301: 182–204. [Google Scholar]

- Breecker DO, Sharp ZD, McFadden LD. 2010. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations during ancient greenhouse climates were similar to those predicted for AD 2100. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107: 576–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burgh J, Visscher H, Dilcher DL, Kürschner WM. 1993. Paleoatmospheric signatures in Neogene fossil leaves. Science 260: 1788–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Hipp A, Song YG, Li QS, Coombes A, Cotton A. 2014. Leaf epidermal features of Quercus subgenus Cyclobalanopsis (Fagaceae) and their systematic significance. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 176: 224–259. [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Jiang XL, Hipp AL, Manos PS, Hahn M. 2018. Phylogeny and biogeography of East Asian evergreen oaks (Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis; Fagaceae): insights into the Cenozoic history of evergreen broad-leaved forests in subtropical Asia. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 119: 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk T, Grimm GW, Manos PS, Deng M, Hipp A. 2017. An updated infrageneric classification of the oaks: review of previous taxonomic schemes and synthesis of evolutionary patterns. bioRxiv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/168146. [Google Scholar]

- Ding WN, Huang J, Su T, Xing YW, Zhou ZK. 2018. An early Oligocene occurrence of the palaeoendemic genus Dipteronia (Sapindaceae) from Southwest China. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 249: 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Doria G, Royer DL, Wolfe AP, Fox A, Westgate JA, Beerling DJ. 2011. Declining atmospheric CO2 during the late Middle Eocene climate transition. American Journal of Science 311: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Eide W, Birks HH. 2006. Stomatal frequency of Betula pubescens and Pinus sylvestris shows no proportional relationship with atmospheric CO2 concentration. Nordic Journal of Botany 24: 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ekart DD, Cerling TE, Montañez IP, Tabor NJ. 1999. A 400 million year carbon isotope record of pedogenic carbonate: implications for paleoatmospheric carbon dioxide. American Journal of Science 299: 805–827. [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge DM, Steele LP, Langenfelds RL, Francey RJ, Barnola JM, Morgan VI. 1996. Natural and anthropogenic changes in atmospheric CO2 over the last 1000 years from air in Antarctic ice and firn. Journal of Geophysical Research 101: 4115–4128. [Google Scholar]

- Finsinger W, Wagner-Cremer F. 2009. Stomatal-based inference models for reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 concentration: a method assessment using a calibration and validation approach. The Holocene 19: 757–764. [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Royer DL, Beerling DJ, et al. 2014. New constraints on atmospheric CO2 concentration for the Phanerozoic. Geophysical Research Letters 41: 4685–4694. [Google Scholar]

- Goldner A, Herold N, Huber M. 2014. Antarctic glaciation caused ocean circulation changes at the Eocene–Oligocene transition. Nature 511: 574–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood DR, Scarr MJ, Christophel DC. 2003. Leaf stomatal frequency in the Australian tropical rainforest tree Neolitsea dealbata (Lauraceae) as a proxy measure of atmospheric pCO2. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 196: 375–393. [Google Scholar]

- Grein M, Konrad W, Wilde V, Utescher T, Roth-Nebelsick A. 2011. Reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 during the early middle Eocene by application of a gas exchange model to fossil plants from the Messel Formation, Germany. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 309: 383–391. [Google Scholar]

- Guo SX. 1978. Pliocene floras of western Sichuan. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 17: 343–352 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo SX. 2011. The late Miocene Bangmai flora from Lincang county of Yunnan, southwestern China. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 50: 353–408. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Elliott-Kingston C, McElwain JC. 2011. a. The stomatal CO2 proxy does not saturate at high atmospheric CO2 concentrations: evidence from stomatal index responses of Araucariaceae conifers. Oecologia 167: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Fitzgerald A, McElwain JC. 2011. b. Cycads show no stomatal-density and index response to elevated carbon dioxide and subambient oxygen. Australian Journal of Botany 59: 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Gallagher A, Elliott-Kingston C, Raschi A, Marandola D, McElwain JC. 2010. a. Stomatal index responses of Agrostis canina to CO2 and sulphur dioxide: implications for palaeo-[CO2] using the stomatal proxy. New Phytologist 188: 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Heath J, McElwain JC. 2010. b. Differences in the response sensitivity of stomatal index to atmospheric CO2 among four genera of Cupressaceae conifers. Annals of Botany 105: 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincke AJC, Broere T, Kürschner WM, Donders TH, Wagner-Cremer F. 2016. Multi-year leaf-level response to sub-ambient and elevated experimental CO2 in Betula nana. PLoS One 11: e0157400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JJ, Xing YW, Turkington R, et al. 2015. A new positive relationship between pCO2 and stomatal frequency in Quercus guyavifolia (Fagaceae): a potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. Annals of Botany 115: 777–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q. 2013. Leaf morphological evolution of Quercus delavayi complex and cupule morphology of Quercus subg. Cyclobalanopsis. MSc Thesis, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China: (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Xing YW, Hu JJ, Huang YJ, Ma HJ, Zhou ZK. 2014. Evolution of stomatal and trichome density of the Quercus delavayi complex since the late Miocene. Chinese Science Bulletin 59: 310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Huang HS, Hu JJ, Su T, Zhou ZK. 2016. The occurrence of Quercus heqingensis n. sp. and its application to palaeo-CO2 estimates. Chinese Science Bulletin 61: 1354–1364 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Shi GL, Su T, Zhou ZK. 2017. Miocene Exbucklandia (Hamamelidaceae) from Yunnan, China and its biogeographic and palaeoecologic implications. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 244: 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Huzioka K, Takahasi E. 1970. The Eocene flora of the Ube coal-field, southwest Honshu, Japan. Journal of the Mining College, Akita University, Series A: Mining Geology 4: 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jia H, Sun BN, Li XC, Xiao L, Wu JY. 2009. Microstructures of one species of Quercus from the Neogene in Eastern Zhejiang and its palaeoenvironmental indication. Frontiers of Earth Science 16: 79–90 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jia H, Jin PH, Wu JY, Wang ZX, Sun BN. 2015. Quercus (subg. Cyclobalanopsis) leaf and cupule species in the late Miocene of eastern China and their paleoclimatic significance. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 219: 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HG. 1992. Plants and microclimate: a quantitative approach to environmental plant physiology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konrad W, Roth-Nebelsick A, Grein M. 2008. Modelling of stomatal density response to atmospheric CO2. Journal of Theoretical Biology 253: 638–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenberg LLR, McElwain JC, Kürschner WM, et al. 2003. Stomatal frequency adjustment of four conifer species to historical changes in atmospheric CO2. American Journal of Botany 90: 610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenberg LLR, Kürschner WM, McElwain JC. 2007. Stomatal frequency change over altitudinal gradients: prospects for paleoaltimetry. Paleoaltimetry: Geochemical and Thermodynamic Approaches 66: 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kürschner WM. 1997. The anatomical diversity of recent and fossil leaves of the durmast oak (Quercus petraea Lieblein/Q. pseudocastanea Goeppert) – implications for their use as biosensors of palaeoatmospheric CO2 levels. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 96: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kürschner WM, van der Burgh J, Visscher H, Dilcher DL. 1996. Oak leaves as biosensors of late Neogene and early Pleistocene paleoatmospheric CO2 concentrations. Marine Micropaleontology 27: 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kürschner WM, Wagner F, Dilcher DL, Visscher H. 2001. Using fossil leaves for the reconstruction of Cenozoic paleoatmospheric CO2 concentrations. In: Gerhard LC, Harrison WE, Hanson BM, eds. Geological perspectives of global climate change. Tulsa, OK: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kürschner WM, Kvaček Z, Dilcher DL. 2008. The impact of Miocene atmospheric carbon dioxide fluctuations on climate and the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105: 449–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi D, Le Floch M, Bereiter B, et al. 2008. High-resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650,000–800,000 years before present. Nature 453: 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Quick WP, Beerling DJ, Woodward FI. 2001. Plant development: signals from mature to new leaves. Nature 411: 154–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Woodward FI, Quick WP. 2002. Long-distance CO2 signalling in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 53: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XC. 2010. The late Cenozoic floras from eastern Zhejiang Province and their paleoclimate reconstruction. PhD Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China: (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin JX, Jach ME, Ceulemans R. 2001. Stomatal density and needle anatomy of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) are affected by elevated CO2. New Phytologist 150: 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann U, Su T, Kunzmann L, et al. 2017. New U-Pb dates show a Paleogene origin for the modern Asian biodiversity hot spots. Geology 46: 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu XY, Gao Q, Han M, Jin JH. 2016. Estimates of late middle Eocene pCO2 based on stomatal density of modern and fossil Nageia leaves. Climate of the Past 12: 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC. 1998. Do fossil plants signal palaeoatmospheric carbon dioxide concentration in the geological past? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 353: 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC. 2004. Climate-independent paleoaltimetry using stomatal density in fossil leaves as a proxy for CO2 partial pressure. Geology 32: 1017–1020. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC. 2005. Climate-independent paleoaltimetry using stomatal density in fossil leaves as a proxy for CO2 partial pressure: comment and reply. Geology 33: e83-e83. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Chaloner WG. 1995. Stomatal density and index of fossil plants track atmospheric carbon dioxide in the Palaeozoic. Annals of Botany 76: 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Chaloner WG. 1996. The fossil cuticle as a skeletal record of environmental change. Palaios 11: 376–388. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Steinthorsdottir M. 2017. Paleoecology, ploidy, paleoatmospheric composition, and developmental biology: a review of the multiple uses of fossil stomata. Plant Physiology 174: 650–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Beerling DJ, Woodward FI. 1999. Fossil plants and global warming at the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. Science 285: 1386–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain JC, Montañez I, White JD, Wilson JP, Yiotis C. 2016. Was atmospheric CO2 capped at 1000 ppm over the past 300 million years? Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 441: 653–658. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa S-I, Livingston NJ, Turpin DH. 2006. Stomatal development in new leaves is related to the stomatal conductance of mature leaves in poplar (Populus trichocarpa×P. deltoides). Journal of Experimental Botany 57: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani M, Kanaoka MM. 2018. Environmental sensing and morphological plasticity in plants. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 83: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montañez IP, McElwain JC, Poulsen CJ, et al. 2016. Climate, pCO2 and terrestrial carbon cycle linkages during late Palaeozoic glacial–interglacial cycles. Nature Geoscience 9: 824–828. [Google Scholar]

- Myers TS, Tabor NJ, Jacobs LL, Mateus O. 2012. Estimating soil pCO2 using paleosol carbonates: implications for the relationship between primary productivity and faunal richness in ancient terrestrial ecosystems. Paleobiology 38: 585–604. [Google Scholar]

- Overdieck D, Strassemeyer J. 2005. Gas exchange of Ginkgo biloba leaves at different CO2 concentration levels. Flora 200: 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Zachos JC, Freeman KH, Tipple B, Bohaty S. 2005. Marked decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations during the Paleogene. Science 309: 600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passalia MG. 2009. Cretaceous pCO2 estimation from stomatal frequency analysis of gymnosperm leaves of Patagonia, Argentina. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 273: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Kürschner WM. 1999. Stomatal density and index: the practice. In: Jones TP, Rowe NP, eds. Fossil plants and spores: modern techniques. London: Geological Society, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Weyers JDB, Lawson T, Raven JA. 1996. Variations in stomatal density and index: implications for palaeoclimatic reconstructions. Plant, Cell & Environment 19: 705–712. [Google Scholar]

- Quan C, Sun CL, Sun YW, Sun G. 2009. High resolution estimates of paleo-CO2 levels through the Campanian (Late Cretaceous) based on Ginkgo cuticles. Cretaceous Research 30: 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Retallack GJ. 2001. A 300-million-year record of atmospheric carbon dioxide from fossil plant cuticles. Nature 411: 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retallack GJ. 2009. Greenhouse crises of the past 300 million years. Geological Society of America Bulletin 121: 1441–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL. 2001. Stomatal density and stomatal index as indicators of paleoatmospheric CO2 concentration. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 114: 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL. 2003. Estimating latest Cretaceous and Tertiary atmospheric CO2 from stomatal indices. In: Wing SL, Gingerich PD, Schmitz B, Thomas E, eds. Causes and consequences of globally warm climates in the early Paleogene. Geological Society of America; Special Paper, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL. 2006. CO2-forced climate thresholds during the Phanerozoic. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70: 5665–5675. [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL, Berner RA, Beerling DJ. 2001. a. Phanerozoic atmospheric CO2 change: evaluating geochemical and paleobiological approaches. Earth-Science Reviews 54: 349–392. [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL, Wing SL, Beerling DJ, et al. 2001. b. Paleobotanical evidence for near present-day levels of atmospheric CO2 during part of the Tertiary. Science 292: 2310–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki O, Foster GL, Schmidt DN, Mackensen A, Kawamura K, Pancost RD. 2010. Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 292: 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Shi GL. 2010. Fossil plants from the Oligocene Ningming Formation of Guangxi, and a preliminary palaeoclimatic reconstruction of the flora. PhD Thesis, Nanjing Institute of Paleontology and Geology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China: (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Smith RY, Greenwood DR, Basinger JF. 2010. Estimating paleoatmospheric pCO2 during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum from stomatal frequency of Ginkgo, Okanagan Highlands, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 293: 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Stace CA. 1965. Cuticular studies as an aid to plant taxonomy. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Botany Series 4: 3–78. [Google Scholar]

- Steinthorsdottir M, Vajda V. 2013. Early Jurassic (late Pliensbachian) CO2 concentrations based on stomatal analysis of fossil conifer leaves from eastern Australia. Gondwana Research 27: 932–939. [Google Scholar]

- Steinthorsdottir M, Jeram AJ, McElwain JC. 2011. Extremely elevated CO2 concentrations at the Triassic/Jurassic boundary. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 308: 418–432. [Google Scholar]

- Steinthorsdottir M, Porter AS, Holohan A, Kunzmann L, Collinson M, McElwain JC. 2016. Fossil plant stomata indicate decreasing atmospheric CO2 prior to the Eocene–Oligocene boundary. Climate of the Past 12: 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Steinthorsdottir M, Vajda V, Pole M. 2019. Significant transient pCO2 perturbation at the New Zealand Oligocene–Miocene transition recorded by fossil plant stomata. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 515: 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sun BN, Dilcher DL, Beerling DJ, Zhang CJ, Yan DF, Kowalski E. 2003. Variation in Ginkgo biloba L. leaf characters across a climatic gradient in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 100: 7141–7146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BN, Wang QJ, Konrad W, Ma FJ, Dong JL, Wang ZX. 2017. Reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 during the Oligocene based on leaf fossils from the Ningming Formation in Guangxi, China. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 467: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tripati AK, Roberts CD, Eagle RA. 2009. Coupling of CO2 and ice sheet stability over major climate transitions of the last 20 million years. Science 326: 1394–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner F. 1998. The influence of environment on the stomatal frequency in birch. PhD Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YQ, Momohara A, Wang L, Lebreton-Anberrée J, Zhou ZK. 2015. Evolutionary history of atmospheric CO2 during the Late Cenozoic from fossilized Metasequoia needles. PLoS One 10: e0130941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI. 1987. Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature 327: 617–618. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI. 1988. The responses of stomata to changes in atmospheric levels of CO2. Plants Today 1: 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI, Bazzaz FA. 1988. The responses of stomatal density to CO2 partial pressure. Journal of Experimental Botany 39: 1771–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI, Kelly CK. 1995. The influence of CO2 concentration on stomatal density. New Phytologist 131: 311–327. [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group of Cenozoic Plants of China (WGCPC). 1978. Fossil plants of China, Vol. 3. Cenozoic plants from China. Beijing: Science Press; (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wynn JG. 2003. Towards a physically based model of CO2‐induced stomatal frequency response. New Phytologist 157: 394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia K, Su T, Liu YS, Xing YW, Jacques FMB, Zhou ZK. 2009. Quantitative climate reconstructions of the late Miocene Xiaolongtan megaflora from Yunnan, southwest China. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 276: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Sun BN, Yan DF, Xie SP, Wei LJ. 2006. Cuticular structure of Quercus pannosa Hand.-Mazz. from the Pliocene in Baoshan, Yunnan Province and its palaeoenvironmental significance. Acta Micropalaeontologica Sinica 23: 23–30 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xing YW, Utescher T, Jacques FMB, et al. 2012. Paleoclimatic estimation reveals a weak winter monsoon in southwestern China during the late Miocene: evidence from plant macrofossils. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 358–360: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xing YW, Hu JJ, Jacques FMB, et al. 2013. A new Quercus species from the late Miocene of southwestern China and its ecological significance. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 193: 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. 2016. The Miocene Kajun flora from Mangkang County, Tibet and its palaeoenvironment implications. PhD Thesis, Xishuangbannna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China: (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Su T, Zhang ST, Deng M, Zhou ZK. 2016. The first fossil record of ring-cupped oak (Quercus L. subgenus Cyclobalanopsis (Oersted) Schneider) in Tibet and its paleoenvironmental implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 442: 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Deng M, Jiang XL, Westwood M, Song YG, Turkington R. 2015. Phylogeography of Quercus glauca (Fagaceae), a dominant tree of East Asian subtropical evergreen forests, based on three chloroplast DNA interspace sequences. Tree Genetics & Genomes 11: 805. doi.org/10.1007/s11295-014-0805-2 [Google Scholar]

- Zachos JC, Röhl U, Schellenberg SA, et al. 2005. Rapid acidification of the ocean during the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Science 308: 1611–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanazzi A, Kohn MJ, MacFadden BJ, Terry DO. 2007. Large temperature drop across the Eocene–Oligocene transition in central North America. Nature 445: 639–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZK. 1993. The fossil history of Quercus. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 15: 21–33 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZK. 1999. Fossils of the Fagaceae and their implications in systematics and biogeography. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 37: 369–385 (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Chai Y, Zhou SS, Yan LC, Shi JP, Yang GP. 2016. Combined community ecology and floristics, a synthetic study on the upper montane evergreen broad-leaved forests in Yunnan, southwestern China. Plant Diversity 38: 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.