Abstract

Background and Aims

Sexual dimorphism in morphology, physiology or life history traits is common in dioecious plants at reproductive maturity, but it is typically inconspicuous or absent in juveniles. Although plants of different sexes probably begin to diverge in gene expression both before their reproduction commences and before dimorphism becomes readily apparent, to our knowledge transcriptome-wide differential gene expression has yet to be demonstrated for any angiosperm species.

Methods

The present study documents differences in gene expression in both above- and below-ground tissues of early pre-reproductive individuals of the wind-pollinated dioecious annual herb, Mercurialis annua, which otherwise shows clear sexual dimorphism only at the adult stage.

Key Results

Whereas males and females differed in their gene expression at the first leaf stage, sex-biased gene expression peaked just prior to, and after, flowering, as might be expected if sexual dimorphism is partly a response to differential costs of reproduction. Sex-biased genes were over-represented among putative sex-linked genes in M. annua but showed no evidence for more rapid evolution than unbiased genes.

Conclusions

Sex-biased gene expression in M. annua occurs as early as the first whorl of leaves is produced, is highly dynamic during plant development and varies substantially between vegetative tissues

Keywords: Dioecy, sex-biased gene expression, sex determination, plant development, sex chromosomes

INTRODUCTION

Dioecy has evolved repeatedly from hermaphroditism and is found in about half of all families of flowering plants (Charlesworth, 2002; Renner, 2014). Many of these species are sexually dimorphic (Bateman, 1948; Arnold, 1994; Delph et al., 2005; Bonduriansky and Chenoweth, 2009; Moore and Pannell, 2011; Delph and Herlihy, 2012), with males and females differing in morphology, phenology, physiology, defence and/or other aspects of their life history (Delph and Wolf, 2005; Moore and Pannell, 2011; Barrett and Hough, 2012). Such differences probably reflect responses to selection to optimize the production and dispersal of pollen vs. seeds and fruits in the face of potentially different somatic costs of reproduction in males and females (Reznick, 1985; Obeso, 2002; Gehring and Delph, 2006). The high somatic cost of seed and fruit is probably one reason for the smaller size of females than males in woody, animal-pollinated species (reviewed in Barrett and Hough, 2012). In contrast, the smaller size of males in wind-pollinated herbs may reflect intrasexual selection for high siring success and the consequent somatic costs of producing large amounts of nitrogen-rich pollen (Harris and Pannell, 2008).

If sexual dimorphism is due to different somatic costs of reproduction, we should expect it to be expressed mainly only when individuals reach reproductive maturity, because natural selection for survival should favour a common optimal phenotype in seedlings, when mortality tends to be particularly high. Nevertheless, several plants are known to show sexual dimorphism in pre-reproductive plants. Males germinate earlier in Rumex nivalis (Stehlik and Barrett, 2005) and Silene latifolia (Doust et al., 1987); female seeds of S. latifolia enter dormancy more readily and experience lower mortality when buried than male seeds (Purrington and Schmitt, 1995); and higher pre-reproductive male mortality due to water inundation at high tides may explain female-biased sex ratios in the saltmarsh grass Distichlis spicata (Eppley, 2001). Although such differences could be due to deleterious mutations on sex chromosomes (e.g. Smith, 1963; Lloyd, 1974; Lardon et al., 1999; Stehlik and Barrett, 2005), they might reflect an adaptive anticipation of the different needs of flowering and fruiting between males and females.

Ultimately, secondary sexual dimorphism requires the differential expression of genes in males and females, i.e. ‘sex-biased gene expression’ (SBGE), which might vary between adults and juveniles (Mank et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2014). However, to our knowledge, differences in gene expression between mature males and females have so far been investigated in only four dioecious angiosperms. In S. latifolia, a species with heteromorphic sex chromosomes (Marais et al., 2008; Delph et al., 2010), the transcriptional patterns of rosette leaves revealed only mild sex bias in gene expression (0.6 and 0.3 % of autosomal genes being female biased and male biased, respectively). Unsurprisingly, SBGE in S. latifolia was overall lower in vegetative leaf tissues compared with flower buds (Zemp et al., 2016). In Asparagus officinalis, a species with homomorphic sex chromosomes (Deng et al., 2012), 570 genes (i.e. about 0.47 % of all loci identified) were found to be sex biased in spear tips, with a large majority of male-biased genes (Harkess et al., 2015). In Populus tremula, which has homomorphic sex chromosomes and a reduced sex-determining region (SDR) (Yin et al., 2008), sexual dimorphism is absent in vegetative traits and sex-biased expression has been found for only two genes, one in the SDR of the Y chromosome (Robinson et al., 2014). In Salix viminalis, reproductive tissues displayed 3567 sex-biased genes, representing 43.6 % of the expressed genes identified in catkin tissues (Darolti et al., 2018). Although transcriptome-wide SBGE has yet to be assessed for immature individuals of any angiosperm, Lipinska et al. (2015) found greater SBGE in the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus in immature (4.62 and 8.22 % for female-biased and male-biased genes, respectively) than in sexually mature individuals (1.23 and 2.25 % for female-biased and male-biased genes, respectively). Although E. siliculosus is sessile and photosynthetic, it is as distantly related to plants as it is to animals. To our knowledge, patterns of SGBE across life stages in angiosperms remain unknown.

While sexual dimorphism may result from SBGE at shared autosomal (or pseudoautosomal) loci (Ellegren and Parsch, 2007; Mank and Ellegren, 2009; Griffin et al., 2013; Parsch and Ellegren, 2013; Grath and Parsch, 2016; Mank, 2017), it may also be due to sequence divergence between homologous haplotypes in an SDR as a result of sexually antagonistic selection (Fisher, 1931; Lewis, 1942; Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 1978; Rice, 1987; Spigler et al., 2008; Charlesworth, 2013; Connallon and Clark, 2014; Wright et al., 2016). This possibility requires sex linkage for at least some genes associated with sexual dimorphism (Zemp et al., 2016). Because vegetative development is under the control of genes across the genome, SBGE of shared autosomal genes should be overwhelmingly more important in bringing about sexual dimorphism than sequence divergence at sexually antagonistic sex-linked genes (Ellegren and Parsch, 2007). Nevertheless, sex-linked genes should probably play a greater role in sexual dimorphism than genes elsewhere in the genome, and there is increasing evidence that this is indeed so. For example, the X chromosome harbours significantly more female-biased genes in the animals Mus musculus and Drosophila melanogaster (Meisel et al., 2012), as well as in the plant S. latifolia, in which sex chromosomes seem to harbour a greater number of sex-biased genes (4.1 and 3.4 % of expressed genes are female biased and male biased, respectively; Zemp et al., 2016).

Because sexual dimorphism may vary among organs or tissues (Yang et al., 2006; Barrett and Hough, 2012; Mank, 2017), patterns of underlying gene expression should also differ between tissues. The most obvious comparison is between vegetative and reproductive organs. In animals, SBGE tends to be extreme in gonads, or in samples that include gonads, and lower in other tissues, even where morphological differences are likely. For example, in D. melanogaster, Assis et al. (2012) found that >75 % of expressed genes were sex biased across multiple tissues, including gonads, whereas only 0.79 % of expressed genes were sex biased in brains alone (Catalàn et al., 2012). Similarly, in the fish Thalassoma bifasciatum, 22.7 and 0.0069 % of genes were sex biased in gonads and brains, respectively (Liu et al., 2015), whereas 53 and 2.5 % were sex biased in these tissues in the bird Cyanistes caeruleus (Mueller et al., 2016). Less is known about the distribution of SBGE among tissues in plants, but it tends to be more prevalent in floral than in vegetative tissues. For example, Zemp et al. (2016) recorded SBGE in 16.8 % of expressed autosomal genes in flowers of S. latifolia, whereas only 0.90 % of expressed genes were sex biased in leaves. To our knowledge, there are as yet no estimates of differences in SBGE between different vegetative tissues for any plant.

Genes involved in SBGE are thought to evolve faster than unbiased genes. This could be due to stronger sex-specific positive selection, or to relaxed constraints on these genes (Ellegren and Parsch, 2007). Intrasexual competition in males is probably stronger than it is in females (Bell, 1978; Burd, 1994; Bond and Maze, 1999; Moore and Pannell, 2011), and may result in enhanced male-biased gene expression (Hollis et al., 2014) and accelerated rates of protein-coding evolution for these genes. We may thus expect to measure higher rates of evolution across male-biased genes compared with female-biased genes (Ellegren and Parsch, 2007; Grath and Parsch, 2016). Differences in the rate of evolution between male-biased and female-biased genes are known in D. melanogaster, with particularly rapid evolution of genes involved in spermatogenesis (Haerty et al., 2007), but female-biased genes evolve faster in D. pseudoobscura (Assis et al., 2012). The relationship between sex bias and evolutionary rates of nucleotide change in protein-coding genes is even less well known for plants. In S. latifolia, male-biased genes do not seem to evolve faster than female-biased genes (Zemp et al., 2016), possibly because male bias is primarily the result of a downregulation of the affected genes in females rather than a change in expression in males (Zemp et al., 2016). Similarly, male- and female-biased genes have been evolving at the same rate under positive selection in the brown alga E. siliculosus (Lipinska et al., 2015).

Here, we analyse patterns of SBGE and their relative rates of sequence evolution in different tissues and developmental stages of the wind-pollinated herb Mercurialis annua (Euphorbiaceae). Dioecious populations of M. annua show sexual dimorphism in several traits, including: inflorescence architecture (males disperse their pollen from specialized erect peduncles, whereas female flowers are sub-sessile and axillary; Durand, 1963); size (males are smaller and have a greater height/biomass ratio; Harris and Pannell, 2008; Hesse and Pannell, 2011); root/shoot ratio (males have higher values; Harris and Pannell, 2008); leaf nitrogen content (males have lower values; Sánchez-Vilas and Pannell, 2011a); flowering time (males flower earlier; Harris and Pannell, 2008); competitive ability (males are more competitive; Sánchez-Vilas et al., 2011; Orlofsky et al., 2016); herbivore defence (males are less well defended; Sánchez-Vilas and Pannell, 2011b); and germination time (Gillot, 1924, cited in Lloyd and Webb, 1977). Ultimately, all these dimensions of sexual dimorphism will be the outcome of upstream differences in gene expression between males and females, although, to our knowledge, the quantitative relationship between sexual dimorphism at the gross phenotypic level and dimorphism in underlying gene expression has not been demonstrated. Sex in M. annua is determined by an XY sex chromosome system (Russell and Pannell, 2015). The sex chromosomes are homomorphic, probably young, and show evidence for only mild differentiation and Y chromosome degeneration (Ridout et al., 2017). Our study should thus be informative about SBGE in species with homomorphic and/or young sex chromosomes.

We analysed patterns of SBGE in tissues sampled from two different experimental populations of M. annua, which we refer to as Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiment 1, we assessed gene expression in above-ground shoots for males vs. females at four developmental stages, from very young seedlings to individuals beginning to flower. In Experiment 2, we compared gene expression in males and females between roots and shoots. Harris and Pannell (2008) found that males of M. annua invest more heavily in roots than do females. Roots and shoots are known to display contrasted profiles of gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana (Schmid et al., 2005), but the extent to which such tissue-specific differences in morphology are associated with sexual dimorphism in dioecious species is so far not known. Of course, SBGE may differ in detail across a wide range of specific tissues, but we remain ignorant even of first-order differences between roots and shoots, and whether any sex-specific patterns in roots might already be expressed in pre-reproductive individuals. Whereas Experiments 1 and 2 differ in terms of growth conditions and tissues sampled, and are therefore not directly comparable, they represent complementary investigations, under a variety of conditions and in a variety of tissues, of SBGE in non-reproductive tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study material

We grew 90 males and 90 females from seeds sampled from an experimental population of adults originating from 25 populations of M. annua in Catalonia, Spain. These individuals were allowed to mate and their seeds were used in our two experiments. Seeds germinated and grew in a growth chamber under constant temperature, moisture and light conditions. For Experiment 1, plants grew in soil with 2 g of slow-release fertilizer per litre of soil. In Experiment 2, to permit extraction of RNA from undisturbed roots, 2-week-old germinated seedlings were transplanted into pots filled with Seramis clay granules for further growth under hydroponic conditions.

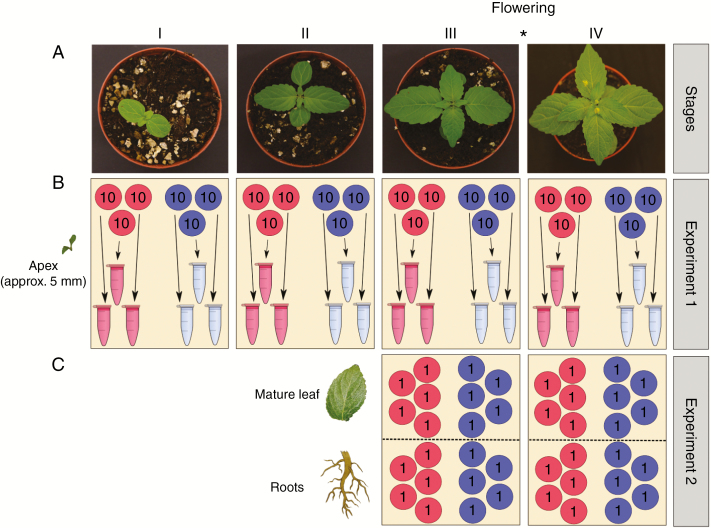

For Experiment 1, we harvested apical tissues (comprising developing leaves and apical meristems) for RNA extraction at four developmental stages, each corresponding to the growth of a new pair of leaves. Stages I, II and III comprised seedlings with cotyledons and the first, second and third pair of true leaves, respectively. Different individuals were sampled and pooled for each stage and sex. We then waited 2 weeks before sampling fully flowering individuals at Stage IV. Apical tissues contain apical meristems, leaf primordia and undifferentiated axillary meristems that may develop later as floral tissue. Although no reproductive tissue may be produced at Stage IV, differences in hormonal signalling that precede cell differentiation may affect these tissues. Sampled tissues were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until RNA extraction. Extra material was collected from each plant for determining its sex on the basis of a sex-linked marker (see below).

Experiment 1 involved samples of pooled individuals, whereas RNA was extracted from unpooled individuals in Experiment 2. For Experiment 1, three pools of tissues were sampled per sex and stage, with ten individuals per pool. In order to reduce intersample variance in gene expression due to variation among individuals, we pooled tissues from ten individuals for each sample. Tissue material was pooled prior to RNA extraction to reduce further any variance that may be introduced during the quantification and pooling of RNA from individuals after extraction (Biswas et al., 2013). For Experiment 2, we sampled roots and mature leaves of each of five males and five females individually at Stages III and IV (as defined for Experiment 1). After transplantation of 2-week-old seedlings from seedling trays, these plants were raised under hydroponic conditions in pots filled with Seramis clay granules to allow access to undamaged roots for sampling. A schematic overview of the protocol designs used for both experiments is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

(A) Images of the typical (male) plant phenotype at each of the four growth stages studied. (B) Experimental design of Experiment 1 focusing on apical tissues. Three replicates have been produced per sex and per stage; each replicate is constituted of RNA extracted from ten pooled individuals. (C) Experimental design of Experiment 2, investigating mature leaves and root tissues. Five replicates have been produced per sex, per stage and per tissue; each replicate constituted of RNA extracted from a single individual. Blue circles and tubes represent male samples. Red circles and tubes represent female samples. The asterisk indicates that flowering occurred between Stage III and Stage IV.

Genetic marker-assisted determination of individual sex

We determined the sex of each individual on the basis of the presence or absence of a Y-linked genetic ‘SCAR’ (sequence-characterized amplified restriction) marker (Khadka et al., 2002). Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh or silica gel-dried leaves according to the protocols of the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen), or of the NucleoSpin® PlantII kit (Macherey-Nagel). Following Russell and Pannell (2015), we checked for DNA integrity by amplifying a neutral 766 bp marker. We identified males on the basis of amplification of OPB01-1562 (Khadka et al., 2002). PCRs were performed in a reaction volume of 20 μL containing 10 μm of each dNTP, 50 μm MgCl2, 20 μm of each primer and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Eurobio Laboratories).

mRNA extraction and sequencing

We extracted RNA from each sample using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. We determined the quality of extracted RNA using Fragment Analyser, and measured concentrations using Qubit at the Center for Integrative Genomics (CIG), University of Lausanne. We prepared RNAseq libraries using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), following the manufacturer’s protocol, along with SuperScriptII (Invitrogen) enzyme for retrotranscription, as recommended by Illumina. Library quality was checked using BioAnalyser at the CIG before being sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2000 machine as paired-end 100 bp reads.

Genome annotation

For genome annotation, we used the assembled Mercurialis annua genome sequence version 1.4 (Ridout et al., 2017), masked for transposable elements and repeat tandem libraries from Mercurialis, Euphorbiacae, Vitis vinifera and from the Plant Genome and System Biology repeats database (http://pgsb.helmholtz-muenchen.de/plant/recat/). We assessed data for quality using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Adaptors were clipped from the resulting sequences with Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014), which we also used for quality filtering: reads were trimmed if the leading or trailing base had a Phred score <3, or if the sliding window Phred score, averaged over four bases, was <15. We then discarded all unpaired reads as well as all pairs of reads for which at least one pair was <36 bases long, leaving an average of >25 million paired-end reads per sample.

We mapped reads onto the assembled M. annua genome (Ridout et al., 2017) with Tophat v2.0.13 (Trapnell et al., 2012), using bowtie2 to align reads and infer splice junctions. Multi-mapping was allowed, and only concordant mapping was reported. The resulting transcripts were assembled for each sample using cufflinks 2.2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2012), correcting for reads that mapped at different genomic locations. The transcriptome assembly was produced from extensive RNAseq data (including transcripts of all libraries analysed in our two experiments, for a total of 1.63 billion pairs of 100 bp reads) using Cuffmerge with default parameters (Trapnell et al., 2012). These assemblies were used as input for the gene-predictor software Augustus 3.0.1 (Stanke et al., 2006), with parameters trained for M. annua (from Ridout et al., 2017). Gene prediction resulted in 34 006 genes with a correct start codon and frame. RNAseq data allowed us to identify several alternative isoforms for some genes, yielding 37 601 transcripts in total. These reads were kept as a reference transcript data set for downstream expression analysis (Brown et al., 2016).

Differential expression analysis

We estimated transcript abundances with Kallisto (Bray et al., 2016) using 31 bp long kmers to pseudo-align all trimmed reads onto the annotated gene set (including all transcripts) produced for M. annua. On average, this represented 20.23 million paired-end reads per sample that were mappable onto the gene set (Supplementary Data Table S1). As described in Soneson et al. (2016), transcript abundances were then summed up within genes and multiplied by the total library size, using the tximport package (Love et al., 2016). This procedure provided scaledTPM (scaled transcripts per million) scores, to which we refer in all figures and tables, as well as count estimates per gene. We used count matrices to estimate differential expression using the DESeq2 package (Love et al., 2014). We corrected P-values for multiple tests using Benjamini and Hochberg’s algorithm in DESeq2, applying an adjusted P-value cut-off of 0.05 for all analysis. We performed likelihood ratio tests (implemented in the DESeq2 package) to test for a potential interaction between developmental stage and sex, e.g. whether one developmental stage particularly affects the level of sex-biased expression more than others.

Functional annotation of differentially expressed genes

We performed a BLAST search (tblastx 2.2.29+) of all mapped transcripts against a custom protein database for eudicots (e-value cut-off of 1 × 10–5, 20 hits retained). Functional categories were attributed by mapping Gene Ontology (GO) terms using Blast2GO 3.0 (Conesa et al., 2005). We identified conserved protein domains among putative genes using InterProScan (Quevillon et al., 2005). We performed Fisher exact tests to test for sex-specific or stage-specific enrichment in particular GO terms, implemented within B2GO [false discovery rate (FDR) <5 %; Conesa et al., 2005]. We finally identified, via reciprocal blast (with an e-value cut-off of 1 × 10–6), a number of orthologues of key genes involved in the main steps of plant reproduction (e.g. meristem cell identity, timing of flowering), described in Pajoro et al. (2014). We tracked the mean expression profiles of these genes, from the earliest stages of development, using expression data from Experiment 1.

Evolutionary rates and detection of selection

We estimated evolutionary rates by comparing M. annua sequences with orthologues from its sister species M. huetii, for which we grew a male and a female in the greenhouse of the University of Lausanne in summer 2015. We sampled seven different tissues from each M. huetii individual (cotyledons, leaves before and after flowering, stem, roots, apical meristem and flowers) and extracted RNA from tissues pooled for each individual. Library quality was checked using BioAnalyser at the CIG, University of Lausanne, before being sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2000 as paired-end 100 bp reads. We assembled a reference transcriptome for M. huetii by combining de novo assembly using Trinity 2.5.1 (Haas et al., 2013) and a genome-guided assembly using the M. annua genome as a reference. We assessed redundancy in the combined transcriptome using CD-HIT-EST v4.6.1 (Li and Godzik, 2006). The reduced assembled M. huetii transcriptome contained 31 979 genes. We used reciprocal blast (with an e-value cut-off of 1 × 10–6) to find orthologous genes between M. annua and M. huetii transcriptomes. Using the PopPhyl pipeline (Tsagkogeorga et al., 2010; Romiguier et al., 2014), we inferred the median synonymous (dS) and non-synonymous divergence (dN) between M. huetii and M. annua from the raw reads for each orthologue, based on the 20 individuals sequenced separately in Experiment 2, as well as neutrality index (NI; McDonald and Kreitman, 1991). We used ranked Mann–Whitney tests to test for differences in dN/dS and NI between female-biased, male-biased and unbiased genes. We also computed permutations t-tests using the R package Deducer (Fellows, 2012).

Sex linkage of genes involved in sex-biased expression

To attribute possible sex linkage for the genes in our analysis, we used a previously established database (Ridout et al., 2017) of 568 putative sex-linked contigs in M. annua, using SEX-DETector (Muyle et al., 2016). We mapped our genes against this database using reciprocal BLAST and reported all results with >90 % similarity (using an e-value cut-off of 1 × 10–6).

RESULTS

Sex-biased gene expression in apical tissue

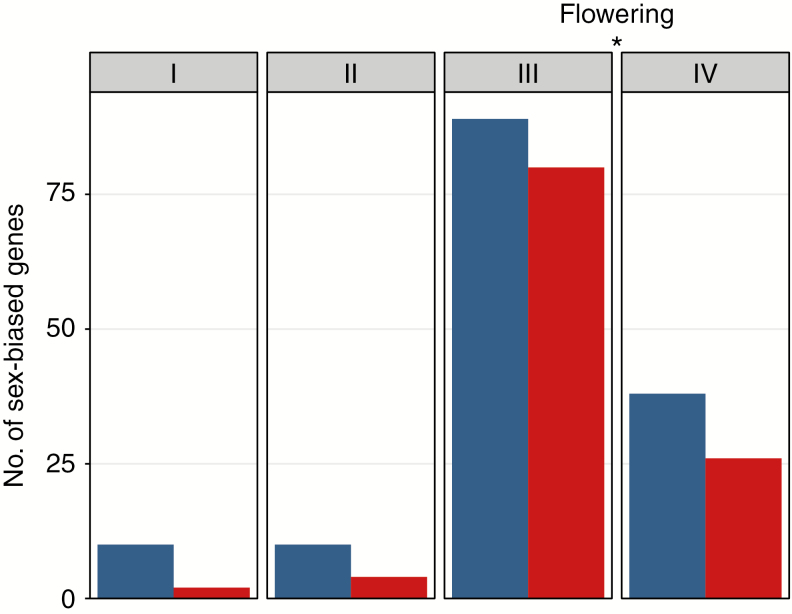

A total of 27 978 genes were expressed in apical tissues of Mercurialis annua across all four developmental stages in Experiment 1 (see Supplementary Data Table S2 for the number of expressed genes per stage). A total of 231 genes were expressed differently between males and females for at least one of the stages (i.e. approx. 0.83 % of expressed genes). For each stage, there were more male-biased than female-biased genes (Fig. 2). Sex-specific expression concerned only a minority of the genes expressed, at most 0.14 and 0.12 % for male- and female-specific genes, respectively (Supplementary Data Table S2). The first two stages showed the fewest differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with a total of 12 genes at Stage I and 13 genes at Stage II. The greatest number of DEGs was observed at Stage III (170 genes), just before flowering (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data Table S2). At Stage IV, after the onset of flowering, 64 genes were sex biased. The sex-biased genes in Experiment 1 showed low fold differences in expression. Indeed, among the identified sex-biased genes, only 6.85 % of male-biased genes and 1.78 % of female-biased genes showed at least a 2-fold difference in expression. Hierarchical clustering of all expressed genes (Supplementary Data Fig. S1) showed that samples cluster by developmental stage, with samples from sexually mature individuals clearly separated from samples from the first three stages.

Fig. 2.

Number of sex-biased genes found at each stage of development. Blue and red bars indicate male- and female-biased genes, respectively. The asterisk indicates that flowering occurred between Stage III and Stage IV.

Comparison of SBGE between roots and shoots

There were 30 192 genes expressed in leaves and/or roots of M. annua in Experiment 2 (Supplementary Data Table S3). Most of the variance in expression could be accounted for by differences across tissues (Supplementary Data Fig. S2), with relatively low differences between sexes and development stages. Indeed, we detected most (approx. 89.7 %) expressed genes in both roots and leaf tissues (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). Hierarchical clustering over all expressed genes (Supplementary Data Fig. S4) showed that samples cluster principally by tissues and developmental stage. A total of 16 038 and 15 234 genes were differentially expressed between tissues before and after flowering, respectively.

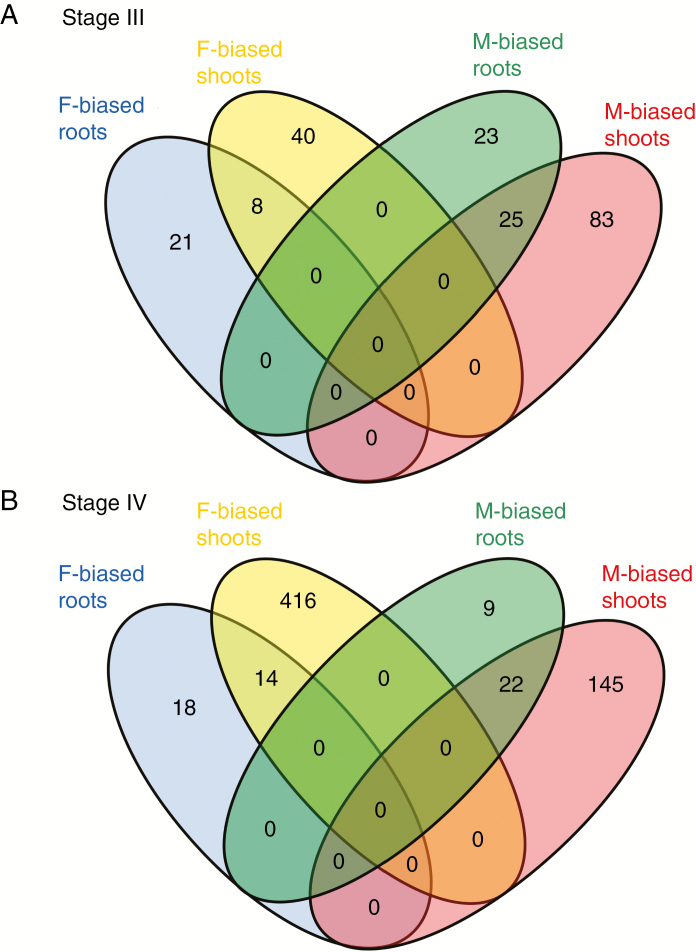

In total, 789 genes were differentially expressed between males and females in Experiment 2 (about 2.61 % of expressed genes), i.e. substantially more DEGs than in Experiment 1. The number of DEGs in roots was low and remained relatively unchanged before and after flowering (77 and 63 DEGs, respectively). In contrast, patterns of SBGE changed more dramatically in mature leaves, with 156 and 597 sex-biased genes before and after flowering, respectively (Supplementary Data Table S3). This trend was mostly attributable to a large increase in the number of female-biased genes in mature leaf tissues, i.e. from 48 to 430 genes before and after flowering, respectively. Male-biased genes, as well as female-biased genes, significantly overlapped in their expression between shoot and root tissues, indicating that a non-negligible part of the sex-biased genes have similar patterns of expression in multiple tissues (Fisher’s exact tests, P < 2.2 × 10–6, for both male- and female-biased genes). Across stages and tissues in Experiment 2, 76.4 % of male-biased and 70.0 % of female-biased genes showed at least a 2-fold difference in expression between the sexes.

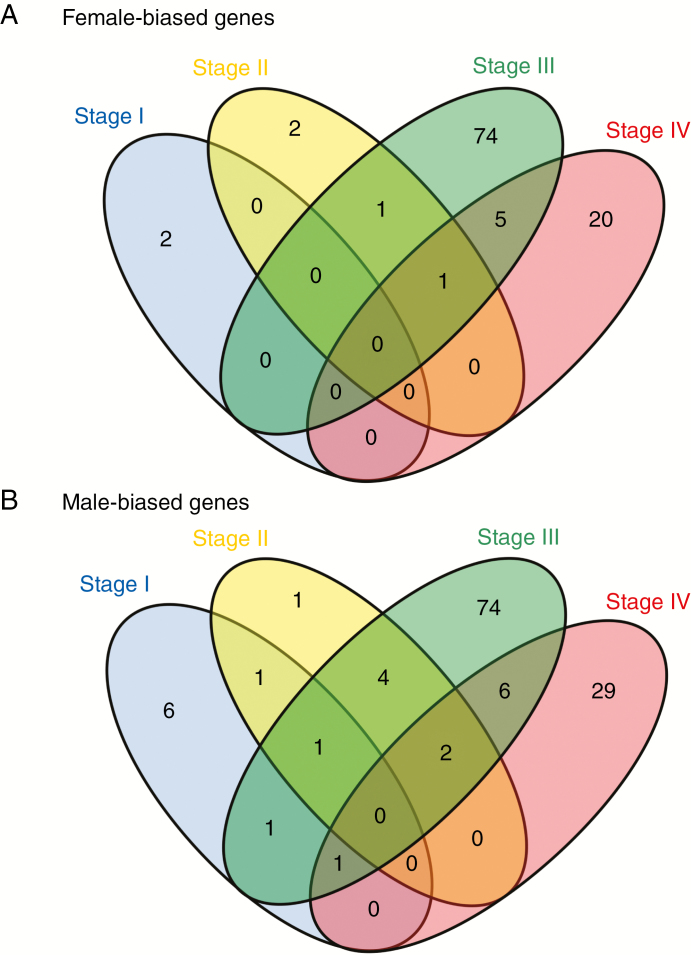

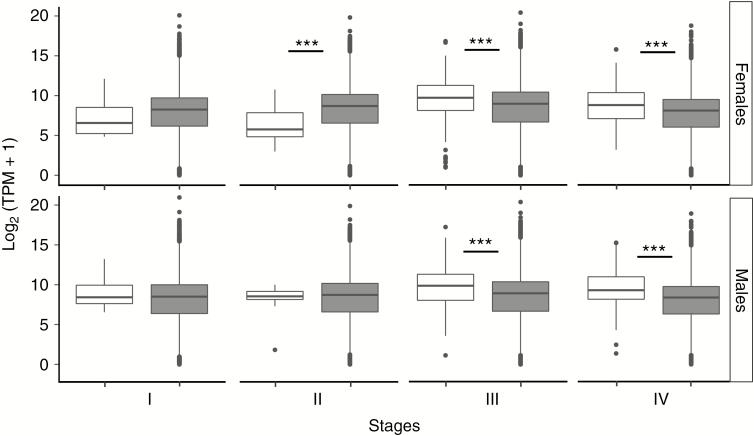

It was found that SBGE was highly dynamic during plant development. sex-biased genes were largely sex and tissue specific in both experiments (Figs 3 and 4). Most sex-biased genes showed bias at only one of the stages, and no genes showed bias across the four stages. While sex-biased and unbiased genes showed similar mean expression in the two earliest developmental stages, males and females showed increased expression of sex-biased genes just before flowering, which continued in mature individuals. This led to significant overexpression of sex-biased compared with unbiased genes in both sexes at these stages (Fig. 5; Table 1). Sex-biased genes showed similar expression in males and females at all stages, except for a slightly significant difference at Stage II, where mean expression was higher in males (P = 0.040; Supplementary Data Fig. S5). At Stages I and II, female- and male-biased genes showed similar expression, averaged across pools. However, at Stages III and IV, male-biased genes showed greater mean expression than female-biased genes, again averaged across individuals (permutation t-tests with 100 000 bootstraps: P = 8.24 × 10–3 and P = 1.47 × 10–2 for Stages III and IV, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Venn diagrams representing the overlapping patterns of sex-biased genes across the four developmental stages investigated in Experiment 1. (A) Diagram for female-biased genes. (B) Diagram for male-biased genes.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagrams representing the overlapping patterns of sex-biased genes across the tissues investigated in Experiment 2. (A) Overlapping patterns of sex-biased genes at Stage III. (B) Overlapping patterns of sex-biased genes at Stage IV. Blue and yellow circles show female-biased genes in roots and leaves, respectively. Green and red circles show male-biased genes in roots and leaves, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Boxplots of the expression level, measured as log2(TPM + 1), of sex-biased (white) and unbiased (grey) genes in males and females at the four developmental stages investigated in Experiment 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of expression levels of sex-biased and unbiased genes in both males and females

| Sex | Statistics | I | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | P | 0.146 | 0.00318*** | <2.2e-16*** | <2.2e-16*** |

| Mean biased genes | 8.48 ± 2.23 | 5.82 ± 2.70 | 9.36 ± 3.36 | 10.02 ± 2.69 | |

| Mean unbiased genes | 7.81 ± 2.95 | 8.18 ± 3.00 | 8.40 ± 3.12 | 8.12 ± 2.93 | |

| Males | P | 0.0545 | 0.541 | <2.2e-16*** | <2.2e-16*** |

| Mean biased genes | 8.96 ± 2.13 | 8.69 ± 1.11 | 10.07 ± 2.30 | 10.05 ± 2.80 | |

| Mean unbiased genes | 8.06 ± 2.98 | 8.21 ± 2.99 | 8.35 ± 3.10 | 7.86 ± 2.91 |

Permutation t-test P-values are presented for 100 000 Monte-Carlo samples generated.

Mean expression levels are given in terms of log2(TPM + 1).

Importantly, likelihood ratio tests revealed a significant stage by sex interaction only for a limited number of expressed genes (six genes in Experiment 1; 154 genes in Experiment 2). Our sampling thus revealed no evidence for gross differences in the pattern of sex bias across all stages, despite the higher number of sex-biased genes detected at Stages III and IV. Neither of these two gene sets was enriched for any particular GO term (Fisher exact tests, FDR <0.05).

Functions and identity of sex-biased genes

In Experiment 1, there was no significant enrichment in GO terms in sex-biased gene sets in apical tissues at the two earliest stages of plant growth. At Stage III, female-biased genes were principally enriched for functions related to photosynthesis/chloroplastic processes, including starch metabolism (Table 2). Similarly, male-biased genes were enriched at Stage III for acetyl-CoA-related functions, i.e. fatty acid synthesis in plastids. In sexually mature individuals (Stage IV), female-biased genes showed no specific enrichment, whereas male-biased genes were enriched for several functions, mostly related to the regulation of gene expression (GO:0010468), protein binding (GO:0005515) and floral meristem determinacy (GO:0010582). The latter may indicate differences of phenology between sexes (see the Discussion).

Table 2.

Fisher’s exact tests for GO term enrichment (FDR <0.05) of sex-biased genes

| Bias and stage | GO ID | GO term | Category | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-biased III | GO:0004075 | Biotin carboxylase activity | F | 1.95 × 10–5 |

| GO:0003989 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity | F | 1.95 × 10–5 | |

| GO:0016885 | Ligase activity forming carbon–carbon bonds | F | 2.54 × 10–5 | |

| F-biased III | GO:0005982 | Starch metabolic process | P | 2.51 × 10–2 |

| GO:0044435 | Plastid part | C | 2.51 × 10–2 | |

| GO:0009507 | Chloroplast | C | 3.00 × 10–2 | |

| M-biased IV | GO:0005515 | Protein binding | P | 8.83 × 10–4 |

| GO:0010468 | Regulation of gene expression | P | 2.25 × 10–3 | |

| GO:0010582 | Floral meristem determinacy | P | 8.89 × 10–3 |

Significant enrichment was detected only at Stages III and IV.

Three representative enriched GO terms are reported, when possible.

Functional categories are C: cellular component, P: biological process, F: molecular function.

In Experiment 2, male-biased genes in root tissues were not enriched for any particular function, either before or after flowering (Table 3). In contrast, female-biased genes in roots before flowering may be involved in stress responses to the presence of inorganic compounds such as copper ions, which may be linked to the hydroponic growth of our samples in Experiment 2. Here, a shortage in nutrients might be more challenging to males, which are more nitrogen demanding during flower production than are females (Harris and Pannell, 2008), although our experiment provides no direct evidence for nutrient limitation. At the same stage, leaves showed enrichment for various metabolic processes, including the activity of the phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase (GO:0000234), which plays a role in sterility sensitivity in arabidopsis (Mou et al., 2002). Female-biased genes in leaves of sexually mature individuals were differently enriched for cell-associated processes involving the cytoskeleton. We detected no enrichment for male-biased genes in leaves of mature individuals.

Table 3.

Fisher’s exact tests for GO term enrichment (FDR <0.05) of sex-biased genes

| Stage | Bias | Tissue | GO ID | GO term | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage III | Male bias | Leaves | GO:0006119 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 1.42 × 10–2 |

| Female bias | Roots | GO:0097501 | Stress response to metal ion | 1.95 × 10–2 | |

| GO:0061687 | Detoxification of inorganic compound | 1.95 × 10–2 | |||

| GO:1990169 | Stress response to copper ion | 1.95 × 10–2 | |||

| Leaves | GO:0000234 | Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase activity | 2.87 × 10–2 | ||

| GO:0006656 | Phosphatidylcholine biosynthetic process | 4.30 × 10–2 | |||

| GO:0016642 | Oxidoreductase activity | 4.30 × 10–2 | |||

| Stage IV | Female bias | Leaves | GO:0015630 | Microtubule cytoskeleton | 3.77 × 10–7 |

| GO:0099080 | Supramolecular complex | 3.69 × 10–6 | |||

| GO:0044430 | Cytoskeletal part | 2.89 × 10–6 |

Two representative enriched GO terms are reported when possible, for each tissue at both stages investigated.

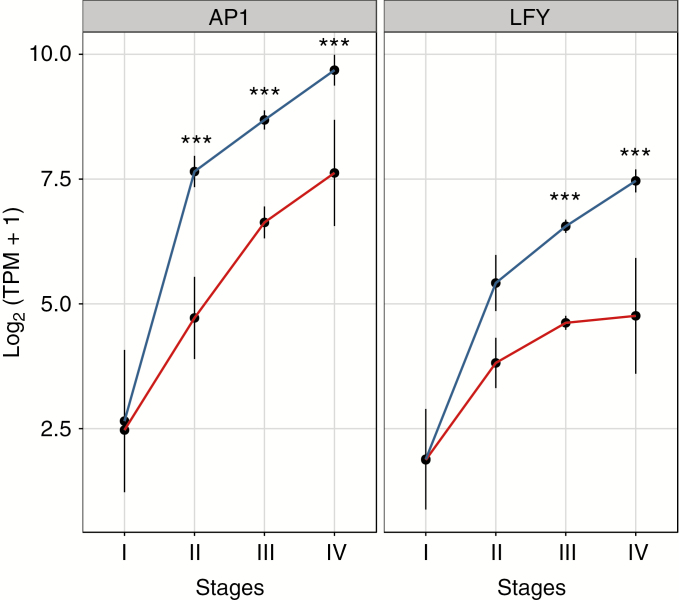

We identified two orthologues among the 13 protein-coding transcription factors involved in plant reproduction described in table 1 of Pajoro et al. (2014), based on retention of reciprocal hits and with an e-value cut-off of 1 × 10–6. We explored the expression of these genes over the course of Experiment 1, which sampled more developmental stages than did Experiment 2. Two genes that were male biased are thought to be directly involved in plant reproduction and the determination of floral meristems: LEAFY (LFY) and APETALA1 (AP1). In Experiment 1, AP1 was male biased from Stages II to IV, while LFY was male biased at Stages III and IV only (Fig. 6). Both genes showed similar levels of expression in young plants at Stage I and were uniformly upregulated in both sexes, although more so in males than in females (Fig. 6). In Experiment 2, only AP1 showed female bias in mature leaf tissues, and neither LFY nor AP1 was sex biased in roots. We also identified the sex-biased expression of an orthologue of GLOBOSA (GLO) and of promoters of SQUAMOSA (SQUA), both of which are involved in floral determinacy (Yu et al., 1999). The former showed male-biased expression in Experiment 1 (g10857), as did two promoters of SQUAMOSA-like genes g1783 and g10599, which were male biased at Stages III and IV, respectively (Supplementary Data Fig. S6); these genes are known to be involved in the regulation of floral architecture in Antirrhinum majus (Egea-Cortines et al., 1999). In addition, g15976, which blasts against AGAMOUS-like isoform 6, was always more highly expressed in males than in females (its expression in females began only at Stage III). Finally, an AGAMOUS-like isoform x4 (g7084) and an orthologue of the CRABS CLAW (CRC) gene (g21428) were female biased at Stage IV, and at both Stages III and IV, respectively (Supplementary Data Fig. S6). CRC is a MADS-box gene involved in carpel development in arabidopsis (Alvarez and Smyth, 1999), activated by the action of transcription factor genes SEPALATA3 and AGAMOUS (Hugouvieux et al., 2018). Among these genes, GLO and a promoter of SQUA showed sex bias in mature leaf tissues in Experiment 2, the former being male biased before flowering, and the latter being female biased after flowering.

Fig. 6.

Tracking expression of APETALA1 (AP1) and LEAFY (LFY) genes, calculated as log2(TPM + 1), across the four stages of development. Red and blue lines indicate the mean expression level in females and males, respectively. Black bars represent the s.d. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of expression between sexes (**0.001 < Padj < 0.05; ***Padj < 0.001).

Evolutionary rates of sex-biased genes

Reciprocal blast comparison of the M. annua transcriptome with that of the closely related species M. huetii identified 13 875 orthologous loci. The PopPhyl pipeline (which uses bwa to map raw reads against the M. huetii transcriptome) permitted us to map reads onto 12 974 M. huetii genes. Among these, 8675 genes had an identified orthologue in M. annua (approx. 28.7 % of genes expressed in Experiment 2). We retained genes for further analysis for which dN/dS >0 and dS >0.0637, following the PopPhyl pipeline (Supplementary Data Table S4). We detected no statistically significant difference in dN/dS or NI between female-biased, male-biased and unbiased genes using either ranked Mann–Whitney (Table 4) or permutation t-tests. Across the three tissues, we identified a total of 220 male-biased and 356 female-biased genes with at least a 2-fold difference in expression between the sexes. Among them were nine male-biased and 35 female-biased genes with orthologues in M. huetii. These sex-biased genes similarly displayed no significant difference in either dN/dS or NI compared with unbiased genes. Male-biased genes showed a slight reduction in dN/dS, as well as an increase of NI above 1, though these effects fell short of statistical significance.

Table 4.

Summary statistics of Wilcoxon tests on dN/dS and NI between male-biased, female-biased and unbiased orthologues with Mercurialis huetii

| Unbiased | Female biased | Male biased | No. of orthologues | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d N/dS | |||||

| Unbiased | 4346 | 0.114 | |||

| Female biased | 0.34 | 112 | 0.112 | ||

| Male biased | 0.72 | 0.88 | 46 | 0.109 | |

| All biased | 0.32 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 158 | 0.110 |

| NI | |||||

| Unbiased | 3783 | 0.63 | |||

| Female biased | 0.89 | 99 | 0.68 | ||

| Male biased | 0.20 | 0.33 | 35 | 1.12 | |

| All biased | 0.44 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 134 | 0.78 |

Genes with dS >0.0637 and non-zero values for dN/dS or NI have been retained for analysis.

Sex linkage of sex-biased genes

Of the 972 sex-biased genes identified in both experiments, 38 (3.90 %) were putatively sex linked, representing 6.69 % of sex-linked genes inferred to date, a proportion that represents a significant enrichment compared with autosomes (Fisher’s exact test, P = 2.31 × 10–4).

DISCUSSION

Gene expression differed between males and females of Mercurialis annua early in development, at least from the point at which they produced their first whorl of leaves, although only a small proportion of all genes showed any such bias. Importantly, none of the four stages we investigated showed any particularly different level of SBGE from the others, although a number of individual genes varied greatly in SBGE between stages (though not in the direction of their bias). We also found that: (1) both the number and identity of sex-biased genes differed between tissues; (2) sex-biased genes were over-represented on the sex chromosomes; and (3) sex-biased genes evolved at a rate similar to unbiased genes.

Low SBGE in Mercurialis annua

Although SBGE was present in vegetative tissues of M. annua both before and after flowering, the number and identity of sex-biased genes differed between our two experiments. Our two experiments should be seen as complementary, and their results cannot be directly compared. Because our experiments differed in the nature of the tissues sampled (apical tissues in Experiment 1 vs. mature leaves and roots in Experiment 2), the sampling design (pooled tissues in Experiment 1 vs. single individuals in Experiment 2) and the growth substrates used (soil in Experiment 1 vs. hydroponic in Experiment 2), variation in gene expression between them is not altogether surprising. Merculialis annua is sexually dimorphic for several morphological and life history traits, but only a small proportion of its genes (0.83 and 2.61 % in Experiments 1 and 2, respectively) were expressed differently between the sexes. These low values are broadly consistent with observations in Populus tremula (0.0065 %; Robinson et al., 2014), Asparagus officinalis (0.47 %; Harkess et al., 2015) and Silene latifolia (0.9 %; Zemp et al., 2016).

There were modest differences in SBGE between root and leaf tissues of M. annua, and in the way gene expression changed during development. There were more sex-biased genes in leaves than roots during vegetative growth, and their number increased at sexual maturity (especially for female-biased genes; Supplementary Data Table S3) only in leaves. The greater number of sex-biased genes in leaves could be partly due to a lower number of cell types in leaves than in roots, but there are also fundamental differences in physiology between roots and shoots. Although male and female functions require different provisioning of nitrogen and water that might place divergent demands on the roots of males vs. females (Harris and Pannell, 2008), above-ground growth and reproduction may be subject to more strongly differing trade-offs between the sexes than below-ground growth.

The consistently low values of SBGE found across tissues in plants contrast with the high variation found across tissues in animals. For example, SBGE ranges from <1 to 77.6 % in Drosophila melanogaster (Assis et al., 2012) and from 13.6 to 72 % in mice (Yang et al., 2006) depending on the tissue investigated. Whereas reproductive tissues in animals show relatively high SBGE, flowers show values that typically are much lower. For instance, in the plants Salix suchowensis (Liu et al., 2013) and Cucumis sativus (Guo et al., 2010), only 2.7 and 1.07 %, respectively, of all genes expressed in flowers were sex biased, values that are similar to those found in animal brains, which have the lowest values of bias among animal tissues. In the one modest exception to this pattern, flowers of S. latifolia were found to have substantially higher SBGE (16.8 %) than rosette leaves (0.9 %; Zemp et al., 2016). Even when more restricted and sex-specific reproductive tissues were investigated, for instance pollen tube in males or synergid cells in females, Gossman et al. (2014) reported 4.24 and 1.02 % of expressed genes sex specifically enriched in these tissues, respectively.

Why should plants display such lower absolute values of SBGE, and lower variance among tissue types, than do animals? One possible reason is that separate sexes in animal models are typically evolutionarily older than those for the plant models studied to date, leaving more time for differential gene expression to evolve (Charlesworth, 2013). This might account for some of the differences, but SBGE in dioecious plants can evolve quickly, as indicated by comparisons of gene expression between males and females and their hermaphroditic ancestors (Zemp et al., 2016). Another possible reason is that plants have a modular development that is similar between sexes (e.g. Grant et al., 1994), including serial homology between leaves, carpels and stamens, whereas animals develop a separate germ line and display deep structural variation between the sexes from the earliest stages of development (e.g. Rinn and Snyder, 2005). Finally, whereas both intra- and intersexual selection may contribute to divergence between the sexes in animals, the opportunities for intersexual selection (female choice) in plants are more limited and probably confined to the potential choice of pollen tubes by pistil tissue, if at all (Stephenson and Bertin, 1983; Arnold, 1994; Skogsmyr and Lankinen, 2002; Moore and Pannell, 2011).

While differences between plants and animals in their development and mating may explain some differences in SBGE, they cannot explain those between angiosperms and the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus, in which vegetative tissues display SBGE >12 %. Although brown algae are distantly related to land plants, they share with them a modular developmental programme, indirect mating behaviour associated with a sessile habit, and the lack of a germ line (Lipinska et al., 2015). It is tempting to suppose that high SBGE in brown algae may be due to the greater age of their separate sexes (at least 70 Ma; Ahmed et al., 2014), but brown algae differ from angiosperms in many respects that might affect gene expression (e.g. separate sexes in the haploid gametophyte phase of the life cycle, and the possession of U and V sex chromosomes that both have non-recombining regions).

Turnover of sex-biased gene identity

We observed high turnover of sex-biased genes during plant development in both above- and below-ground tissues of M. annua. SBGE was apparent with the first whorl of leaves, and might well have been present as early as the seed stage. However, the sex-biased genes identified at these early stages did not maintain their biased expression for long. It is possible that plants prepare themselves during early vegetative growth for later sex-specific phenotypes at flowering, e.g. in resource acquisition and/or allocation traits. Such a strategy might involve differential root vs. shoot growth (Gedroc et al., 1996), or differential timing in preparation for flowering (Pickup and Barrett, 2012), with implications for gene expression. Later in development, SBGE may be associated with sex organ production and the direct costs of reproduction, involving different genes more directly related to flowering (as suggested by our GO analysis). Such dynamic sexual dimorphism was found in Rumex hastatulus, in which males were larger than females at the time of flowering yet smaller subsequently (Pickup and Barrett, 2012), and there are likely to have been corresponding difference in SBGE, too.

The phenology of flowering may influence the dynamics of sexual dimorphism through sex differences in the onset of somatic costs of reproduction. In our experiments, the number of sex-biased genes in M. annua peaked just before, and then after, sexual maturity (Fig. 2). Because the potential somatic costs of reproduction should mostly affect vegetative growth during and after reproduction, we expected and observed more sex-biased genes in sexually mature individuals (0.23 % of expressed genes at Stage IV) compared with the first stages of development (0.04 and 0.05 % of expressed genes at Stages I and II, respectively). However, the number of sex-biased genes just prior to flowering (Stage III) was even higher (about 0.60 % of expressed genes), perhaps reflecting preparation for the ensuing sex-specific transition to flowering. This pattern might be expected especially for species such as M. annua in which rudiments of the opposite sex are absent within flowers and where male and female flowers differentiate early in development (Lebel-Hardenack and Grant, 1994), probably via the differential expression of floral identity genes (e.g. ABC genes; Weigel and Meyerowitz, 1994). It is perhaps relevant that the genes LEAFY and APETALA1 were male biased in expression in developing tissues of M. annua before flowering occurred (Stage IV; Fig. 6); although the earlier flowering by males of M. annua may not be directly related to meristem identity determination, earlier flowering might still be associated with SBGE prior to sex organ differentiation.

Genomic location of sex-biased genes

Sex-biased genes were proportionally over-represented among sex-linked genes in M. annua, indicating that sex chromosomes may play a more important role than autosomes in sexual dimorphism, as predicted by theory (Rice, 1984; Kirkpatrick and Hall, 2004; van Doorn and Kirkpatrick, 2007; Dean and Mank, 2014). Specifically, the evolution of SBGE for sex-linked genes is consistent with the idea that sex linkage partly resolves intralocus conflicts associated with sexually antagonistic selection (Bonduriansky and Chenoweth, 2009; Cox and Calsbeek, 2009). Patterns similar to those in M. annua have also been found in other angiosperm species. For instance, 4.09 % of all sex-biased genes in flower buds were found linked to the sex chromosome 19 in Salix suchowensis (Liu et al., 2013), and the Y chromosome of Silene latifolia appears to harbour quantitative trait loci involved in sexual dimorphism and responsible for most of the trait variance in males (Scotti and Delph, 2006).

Evolutionary rates of sequence evolution for sex-biased genes

Sex-biased genes in M. annua evolved no faster or slower than unbiased genes. The rate of evolution of sex-biased genes is expected to increase with the degree of sex bias they present (Harrison et al., 2015). Our results might thus reflect an overall lower difference in expression between sexes than recorded in other studies, although genes with at least a 2-fold difference in expression similarly did not show any difference in evolutionary rates, though our sampling might have lacked power to detect such differences. Interestingly, male-biased genes showed the only computed NI above 1, indicating purifying selection. Although not significant, this result for male-biased genes is similar to that reported recently for the perennial plant Salix viminalis (Darolti et al., 2018).

We inferred that male- and female-biased genes have also been evolving at about the same rate in M. annua, so that biased expression in the shoot apex, leaves and roots is not associated with more nucleotide substitutions. These tissues are shared between sexes and express genes that are neither sex limited nor sex specific (Supplementary Data Table S2). Although the breadth of expression of sex-biased genes might influence their evolutionary rate (Meisel et al., 2012), the relationship between the tissue specificity of expressed genes and the degree of sex-biased or sex-specific expression is likely to be quite complex (Dean and Mank, 2016) because of constraints imposed by pleiotropy on genes expressed in different tissues. Indeed, Meisel et al. (2012) could attribute accelerated evolution of sex-biased genes in Drosophila melanogaster and Mus musculus to genes with tissue-specific expression. In Ectocarpus siliculosus, sex-biased genes are more narrowly expressed in terms of both tissues and developmental stages, and evolutionary rates appear to be higher for those genes (Lipinska et al., 2015). In contrast, most genes in M. annua are expressed throughout development, so the absence of evolutionary rate heterogeneity is perhaps not surprising.

CONCLUSIONS

Dioecious M. annua shows rather limited SBGE in vegetative tissues. This finding contrasts with what has been found in many animals, in particular when considering reproductive tissues, but it is consistent with the few plant species studied to date. It is striking that sexual dimorphism in gene expression in M. annua begins at early stages of vegetative development, long before flowering. Although other dioecious plants show life history differences between males and females at the seed and seedling stage (Zluvova et al, 2010; Barrett and Hough, 2012; and see the Introduction), to our knowledge no previous study of a flowering plant has sought evidence of SBGE so early in development. Nevertheless, it is likely that SDGs and relevant downstream loci in dioecious plants are often expressed early in development. We remain ignorant about the details of sex determination and sexual differentiation in M. annua. However, the exogenous application of the hormone cytokinin causes males to produce pistillate flowers and seeds (Louis and Durand, 1978; Hamdi, 1987; Eppley and Pannell, 2009), and it seems likely that hormones will also play a role in sex determination and sexual dimorphism throughout development. Patterns of gene expression in males feminized by the application of exogenous hormones would be revealing, as would those in individuals for which putative nutrient depletion is measured.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Figure S1: hierarchical clustering of all expressed genes, across all samples in Experiment 1. Figure S2: PCA plot of all samples, including roots and shoots, studied in Experiment 2. Figure S3: Venn diagram of all expressed genes across leaf and root tissues of Experiment 2. Figure S4: hierarchical clustering of all expressed genes, across all samples in Experiment 2. Figure S5: tracking of the average expression of sex-biased genes in males and females across the four developmental stages investigated in Experiment 1, measured in log2(TPM + 1). Figure S6: tracking of the expression of extra developmental genes involved in determining the identity of the floral organ, across the four stages of development in Experiment 1. Table S1: sequencing pair-of-reads counts and alignment statistics from Kallisto for all sequenced M. annua pooled samples in Experiment 1. Table S2: number of sex-specific and sex-biased genes as a proportion of the total number of genes expressed at each stage of development. Table S3: number of sex-specific and sex-biased genes in Experiment 2, as a proportion of the total number of genes expressed at each stage of development. Table S4: summary statistics on indexes calculated from the PopPhyl pipeline for each orthologue between M. annua and M.huetii identified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by grants 31003A_163384 and CRSII3 from the Swiss National Science Foundation. We thank members of the Pannell lab for helpful discussions. G.C.C. and J.R.P. designed the experiments. G.C.C. conducted the experiments, laboratory work and data analysis. M.T. assembled and produced a consensus transcriptome of Mercurialis huetii. G.C.C. and J.R.P. drafted the manuscript. All authors commented on and approved the final manuscript. Reads are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under accession no. E-MTAB-6716 (for Experiment 1) and no. E-MTAB-6715 (for Experiment 2).

LITERATURE CITED

- Ahmed S, Cock JM, Pessia E, et al. 2014. A haploid system of sex determination in the brown alga Ectocarpus sp. Current Biology 24: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Smyth DR. 1999. CRABS CLAW and SPATULA, two Arabidopsis genes that control carpel development in parallel with AGAMOUS. Development 126: 2377–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ. 1994. Bateman’s principals and the measurement of sexual selection in plants and animals. American Naturalist 144: S126–S149. [Google Scholar]

- Assis R, Zhou Q, Bachtrog D. 2012. Sex-biased transcriptome evolution in Drosophila. Genome Biology and Evolution 4: 1189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SCH, Hough J. 2012. Sexual dimorphism in flowering plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AJ. 1948. Intra sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2: 349–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. 1978. The evolution of anisogamy. Journal of Theoretical Biology 73: 247–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Agrawal YN, Mucyn TS, Dangl JL, Jones CD. 2013. Biological averaging in RNA-seq. BioRXiv doi: 1309.0670. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond WJ, Maze KE. 1999. Survival costs and reproductive benefits of floral display in a sexually dimorphic dioecious shrub, Leucadendron xanthoconus. Evolutionary Ecology 13: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF. 2009. Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24: 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. 2016. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nature Biotechnology 34: 525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JWS, Calixto CPG, Zhang R. 2016. High-quality reference transcript datasets hold the key to transcript-specific RNA-sequencing analysis in plants. New Phytologist 213: 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd M. 1994. Bateman’s principle and plant reproduction: the role of pollen limitation in fruit and seed set. Botanical Review 60: 83–139. [Google Scholar]

- Catalàn A, Hutter S, Parsch J. 2012. Population and sex differences in Drosophila melanogaster brain gene expression. BMC Genomics 13: 654. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. 1978. A model for the evolution of dioecy and gynodioecy. American Naturalist 112: 975–997. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D. 2002. Plant sex determination and sex chromosomes. Heredity 88: 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D. 2013. Plant sex chromosome evolution. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 405–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. 2005. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21: 3674–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connallon T, Clark AG. 2014. Evolutionary inevitability of sexual antagonism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281: 20132123. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RM, Calsbeek R. 2009. Sexually antagonistic selection, sexual dimorphism, and the resolution of intralocus sexual conflict. American Naturalist 173: 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darolti I, Wright AE, Pucholt P, Berlin S, Mank JE. 2018. Slow evolution of sex-biased genes in the reproductive tissue of the dioecious plant Salix viminalis. Molecular Ecology 27: 694–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R, Mank JE. 2014. The role of sex chromosomes in sexual dimorphism: discordance between molecular and phenotypic data. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 27: 1443–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R, Mank JE. 2016. Tissue specificity and sex-specific regulatory variation permit the evolution of sex-biased gene expression. American Naturalist 188: E74–E84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delph LF, Herlihy CR. 2012. Sexual, fecundity, and viability selection on flower size and number in a sexually dimorphic plant. Evolution 66: 1154–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delph LF, Wolf DE. 2005. Evolutionary consequences of gender plasticity in genetically dimorphic breeding systems. New Phytologist 166: 119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delph LF, Gehring JL, Arntz MA, Levri M, Frey FM. 2005. Genetic correlations with floral display lead to sexual dimorphism in the cost of reproduction. American Naturalist 166: 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delph LF, Arntz MA, Scotti-saintagne C, Scotti I. 2010. The genomic architecture of sexual dimorphism in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Evolution 64: 2873–2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng CL, Qin RY, Wang NN, et al. 2012. Karyotype of Asparagus by physical mapping of 45S and 5S rDNA by FISH. Journal of Genetics 91: 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn GS, Kirkpatrick M. 2007. Turnover of sex chromosomes induced by sexual conflict. Nature 449: 909–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doust JL, O’Brien G, Doust L. 1987. Effect of density on secondary sex characteristics and sex ratio in Silene alba (Caryophyllaceae). American Journal of Botany 74: 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Durand B. 1963. Le complexe Mercurialis annua LSL: une étude biosystématique. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Botanique, Paris 12: 579–736. [Google Scholar]

- Egea-Cortines M, Saedler H, Sommer H. 1999. Ternary complex formation between the MADS-box proteins SQUAMOSA, DEFICIENS and GLOBOSA is involved in the control of floral architecture in Antirrhinum majus. EMBO Journal 18: 5370–5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H, Parsch J. 2007. The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nature Reviews. Genetics 8: 689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppley SM. 2001. Gender-specific selection during early life history stages in the dioecious grass Distichlis spicata. Ecology 82: 2022–2031. [Google Scholar]

- Eppley SM, Pannell JR. 2009. Inbreeding depression in dioecious populations of the plant Mercurialis annua: comparisons between outcrossed progeny and the progeny of self-fertilized feminized males. Heredity 102: 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows I. 2012. Deducer: a data analysis GUI for R. Journal of Statistical Software 49: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. 1931. The evolution of dominance. Biological Reviews 6: 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gedroc JJ, McConnaughay KDM, Coleman JS. 1996. Plasticity in root/shoot partitioning: optimal, ontogenetic, or both? Functional Ecology 10: 44–50.

- Gehring JL, Delph LF. 2006. Effects of reduced source–sink ratio on the cost of reproduction in females of Silene latifolia. International Journal of Plant Sciences 167: 843–851. [Google Scholar]

- Gillot P. 1924. Remarques sur le déterminisme du sexe chez Mercurialis annua L. Compte Rendu Hebdomadaire des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences 179: 1995–1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gossmann TI, Schmid MW, Grossniklaus U, Schmid KJ. 2014. Selection-driven evolution of sex-biased genes is consistent with sexual selection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 574–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grath S, Parsch J. 2016. Sex-biased gene expression. Annual Review of Genetics 50: 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, Hunkirchen B, Saedler H. 1994. Developmental differences between male and female flowers in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. The Plant Journal 6: 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin RM, Dean R, Grace JL, Rydén P, Friberg U. 2013. The shared genome is a pervasive constraint on the evolution of sex-biased gene expression. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2168–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Zheng Y, Joung J-G, et al. 2010. Transcriptome sequencing and comparative analysis of cucumber flowers with different sex types. BMC Genomics 11: 384. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, et al. 2013. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-Seq: reference generation and analysis with Trinity. Nature Protocols 8: 1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haerty W, Jagadeeshan S, Kulathinal RJ, et al. 2007. Evolution in the fast lane: rapidly evolving sex-related genes in Drosophila. Genetics 177: 1321–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi S. 1987. Régulation génétique et biochimique de l’auxine dans les souches fertiles et stériles de M. annua. PhD thesis, University of Orléans. [Google Scholar]

- Harkess A, Mercati F, Shan H-Y, Sunseri F, Falavigna A, Leebens-Mack J. 2015. Sex-biased gene expression in dioecious garden asparagus (Asparagus officinalis). New Phytologist 207: 883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Pannell JR. 2008. Roots, shoots and reproduction: sexual dimorphism in size and costs of reproductive allocation in an annual herb. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275: 2595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PW, Wright AE, Zimmer F, et al. 2015. Sexual selection drives evolution and rapid turnover of male gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112: 4393–4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E, Pannell JR. 2011. Sexual dimorphism in a dioecious population of the wind-pollinated herb Mercurialis annua: the interactive effects of resource availability and competition. Annals of Botany 107: 1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis B, Houle D, Yan Z, Kawecki TJ, Keller L. 2014. Evolution under monogamy feminizes gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature Communications 5: 3482. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugouvieux V, Silva CS, Jourdain A, et al. 2018. Tetramerization of MADS family transcription factors SEPALLATA3 and AGAMOUS is required for floral meristem determinacy in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Research 46: 4966–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka DK, Nejidat A, Tal M. 2002. DNA markers for sex: molecular evidence for gender dimorphism in dioecious Mercurialis annua L. Molecular Breeding 9: 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M, Hall DW. 2004. Male-biased mutation, sex linkage, and the rate of adaptive evolution. Evolution 58: 437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardon A, Georgiev S, Abdelaziz M, Le Merrer G, Negrutiu I. 1999. Sexual dimorphism in white campion: complex control of carpel number is revealed by Y chromosome deletions. Genetics 151: 1173–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel-Hardenack S, Grant SR. 1994. Genetics of sex determination in flowering plants. Trends in Plant Science 2: 997–999. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. 1942. The evolution of sex in flowering plants. Biological Reviews 17: 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. 2006. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22: 1658–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinska A, Cormier A, Luthringer R, et al. 2015. Sexual dimorphism and the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in the brown alga Ectocarpus. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32: 1581–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Lamm MS, Rutherford K, Black MA, Godwin JR, Gemmell NJ. 2015. Large-scale transcriptome sequencing reveals novel expression patterns for key sex-related genes in a sex-changing fish. Biology of Sex Differences 6: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yin T, Ye N, Chen Y, Yin T, Liu M, Hassani D. 2013. Transcriptome analysis of the differentially expressed genes in the male and female shrub willows (Salix suchowensis). PLoS One 8: e60181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DG. 1974. Female-predominant sex ratios in angiosperms. Heredity 32: 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DG, Webb CJ. 1977. Secondary sex characters in plants. Botanical Review 43: 177–216. [Google Scholar]

- Louis JP, Durand B. 1978. Studies with the dioecious angiosperm Mercurialis annua L. (2n = 16): correlation between genic and cytoplasmic male sterility, sex segregation and feminizing hormones (cytokinins). Molecular and General Genetics 165: 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 15: 550–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Anders S, Kim V, Huber W. 2016. RNA-Seq workflow: gene-level exploratory analysis and differential expression. F1000Research 4: 1070. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7035.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank JE. 2017. The transcriptional architecture of phenotypic dimorphism. Nature, Ecology and Evolution 1: 6. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank JE, Ellegren H. 2009. All dosage compensation is local: gene-by-gene regulation of sex-biased expression on the chicken Z chromosome. Heredity 102: 312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank JE, Nam K, Brunström B, Ellegren H. 2010. Ontogenetic complexity of sexual dimorphism and sex-specific selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27: 1570–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais GAB, Nicolas M, Bergero R, et al. 2008. Evidence for degeneration of the Y chromosome in the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Current Biology 18: 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. 1991. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature 351: 652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel RP, Malone JH, Clark AG. 2012. Disentangling the relationship between sex-biased gene expression and X-linkage. Genome Research 22: 1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JC, Pannell JR. 2011. Sexual selection in plants. Current Biology 21: R176–R182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Z, Wang X, Fu Z, et al. 2002. Silencing of phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase results in temperature-sensitive male sterility and salt hypersensitivity in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 14: 2031–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JC, Kuhl H, Timmermann B, Kempenaers B. 2016. Characterization of the genome and transcriptome of the blue tit Cyanistes caeruleus: polymorphisms, sex-biased expression and selection signals. Molecular Ecology Resources 16: 549–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyle A, Käfer J, Zemp N, Mousset S, Picard F, Marais GAB. 2016. SEX-DETector: a probabilistic approach to study sex chromosomes in non-model organisms. Genome Biology and Evolution 8: 2530–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JR. 2002. The costs of reproduction in plants. New Phytologist 155: 321–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlofsky EM, Kozhoridze G, Lyubenova L, et al. 2016. Sexual dimorphism in the response of Mercurialis annua to stress. Metabolites 6: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajoro A, Biewers S, Dougali E, et al. 2014. The (r)evolution of gene regulatory networks controlling Arabidopsis plant reproduction: a two-decade history. Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 4731–4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsch J, Ellegren H. 2013. The evolutionary causes and consequences of sex-biased gene expression. Nature Reviews. Genetics 14: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JC, Harrison PW, Mank JE. 2014. The ontogeny and evolution of sex-biased gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 1206–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickup M, Barrett SCH. 2012. Reversal of height dimorphism promotes pollen and seed dispersal in a wind-pollinated dioecious plant. Biology Letters 8: 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purrington CB, Schmitt J. 1995. Sexual dimorphism of dormancy and survivorship in buried seeds of Silene latifolia. Journal of Ecology 83: 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, et al. 2005. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Research 33: 116–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner SS. 2014. The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database. American Journal of Botany 101: 1586–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznick D. 1985. Costs of reproduction: an evaluation of the empirical evidence. Oikos 44: 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Rice WWR. 1984. Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38: 1416–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice WWR. 1987. The accumulation of sexually antagonistic genes as a selective agent promoting the evolution of reduced recombination between primitive sex chromosomes. Evolution 41: 911–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout KE, Veltsos P, Muyle A, et al. 2017. Hallmarks of early sex-chromosome evolution in the dioecious plant Mercurialis annua revealed by de novo genome assembly, genetic mapping and transcriptome analysis. BioRXiv doi: 10.1101/106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn JL, Snyder M. 2005. Sexual dimorphism in mammalian gene expression. Trends in Genetics 21: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, Delhomme N, Mähler N, et al. 2014. Populus tremula (European aspen) shows no evidence of sexual dimorphism. BMC Plant Biology 14: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romiguier J, Gayral P, Ballenghien M, et al. 2014. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature 515: 261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JRW, Pannell JR. 2015. Sex determination in dioecious Mercurialis annua and its close diploid and polyploid relatives. Heredity 114: 262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vilas J, Pannell JR. 2011a. Sex-differential herbivory in androdioecious Mercurialis annua. PLoS One 6: e22083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vilas J, Pannell JR. 2011b. Sexual dimorphism in resource acquisition and deployment: both size and timing matter. Annals of Botany 107: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vilas J, Turner A, Pannell JR. 2011. Sexual dimorphism in intra- and interspecific competitive ability of the dioecious herb Mercurialis annua. Plant Biology 13: 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Davison TS, Henz SR, et al. 2005. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nature Genetics 37: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti I, Delph LF. 2006. Selective trade-offs and sex-chromosome evolution in Silene latifolia. Evolution 60: 1793–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogsmyr I, Lankinen A. 2002. Sexual selection: an evolutionary force in plants?Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 77: 537–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW. 1963. The mechanism of sex determination in Rumex hastatulus. Genetics 48: 1265–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. 2016. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research 4: 1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigler RB, Lewers KS, Main DS, Ashman T-L. 2008. Genetic mapping of sex determination in a wild strawberry, Fragaria virginiana, reveals earliest form of sex chromosome. Heredity 101: 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I, Hayes A, Waack S, Morgenstern B. 2006. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 34: W435–W439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik I, Barrett SCH. 2005. Mechanisms governing sex-ratio variation in dioecious Rumex nivalis. Evolution 59: 814–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson AG, Bertin RI. 1983. Male competition, female choice and sexual selection in plants. In: Real L, ed. Pollination biology. New York: Academic Press Inc, 110–149. [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, et al. 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols 7: 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsagkogeorga G, Turon X, Galtier N, Douzery EJP, Delsuc F. 2010. Accelerated evolutionary rate of housekeeping genes in tunicates. Journal of Molecular Evolution 71: 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Meyerowitz EM. 1994. The ABCs of floral homeotic genes. Cell 78: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AE, Dean R, Zimmer F, Mank JE. 2016. How to make a sex chromosome?Nature Communications 7: 12087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Yang X, Schadt EE, et al. 2006. Tissue-specific expression and regulation of sexually dimorphic genes in mice. Genome Research 16: 995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin T, DiFazio S, Gunter L, et al. 2008. Genome structure and emerging evidence of an incipient sex chromosome in Populus. Genome Research 18: 422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Kotilainen M, Pöllänen E, et al. 1999. Organ identity genes and modified patterns of flower development in Gerbera hybrida (Asteraceae). The Plant Journal 17: 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemp N, Tavares R, Muyle A, Charlesworth D, Marais GAB, Widmer A. 2016. Evolution of sex-biased gene expression in a dioecious plant. Nature Plants 2: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]