Abstract

Introduction:

Numerous reports highlight variations in pain clinic provision between services, particularly in the provision of multidisciplinary services and length of waiting times. A National Audit aims to identify and quantify these variations, to facilitate raising standards of care in identified areas of need. This article describes a Quality Improvement Programme cycle covering England and Wales that used such an approach to remedy the paucity of data on the current state of UK pain clinics.

Methods:

Clinics were audited over a 4-year period using standards developed by the Faculty of Pain Medicine of The Royal College of Anaesthetists. Reporting was according to guidance from a recent systematic review of national surveys of pain clinics. A range of quality improvement measures was introduced via a series of roadshows led by the British Pain Society.

Results:

94% of clinics responded to the first audit and 83% responded to the second. Per annum, 0.4% of the total national population was estimated to attend a specialist pain service. A significant improvement in multidisciplinary staffing was found (35–56%, p < 0.001) over the 4-year audit programme, although this still requires improvement. Very few clinics achieved recommended evidence-based waiting times, although only 2.5% fell outside government targets; this did not improve. Safety standards were generally met. Clinicians often failed to code diagnoses.

Conclusion:

A National Audit found that while generally safe many specialist pain services in England and Wales fell below recommended standards of care. Waiting times and staffing require improvement if patients are to get effective and timely care. Diagnostic coding also requires improvement.

Keywords: Chronic pain, pain clinics, pain measurement, pain, intractable

Introduction

Specialist pain services are an established component of healthcare in most nations. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) provides guidance on standards of care that include the approach, infrastructure and treatment content of such services, and recommended waiting times.1,2 Treatment should be evidence-based; take into account biomedical, psychological and social factors; be multidisciplinary; and give high priority to safety. Services are further expected to carry out research, evaluation of patient outcomes and clinical education.

Chronic pain has become a growing public health concern both with respect to its prevalence and to unsatisfactory treatment. Of particular concern are the rising numbers of problems associated with long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain, with the United States declaring this a public health emergency in 2017.3 It is essential that pain clinics provide leadership in this area. A recent systematic review of large-scale surveys of pain clinics in seven countries described wide variation in standards of care.4 Setting standards has also proved problematic.5

Quality improvement in pain management services is also recognised as challenging.6 Issues are the subjective nature of pain, a lack of consensus on treatment and, in the United Kingdom, several government reviews highlighted the paucity of data on specialist pain services, including information on the patient population, the types of treatment offered and their outcomes.7,8 In 2008, both the Chief Medical Officers (CMO) in England and the Welsh Government recommended several interventions to improve the quality of care for people with chronic pain.9,10 One recommendation was that all pain clinics should submit data to a national database so that services could be meaningfully compared. National Audits are a recognised way of doing this, aiming to raise the standard of care through engaging clinicians in reporting the quality of their care against agreed standards and comparing their service with others.11 Further recommendations to improve quality included a consensus pathway of care and better understanding of need through data collection via the Health Survey for England. While there are other examples of quality improvement interventions in other jurisdictions,12–14 no attempt has been published involving a whole nation’s pain services in a Quality Improvement Programme.

A Quality Improvement Programme was implemented in England and Wales and a National Audit funded to support this from 2010–2014. Four reports were published over the lifespan of the audit, which have now been combined into two reports.15,16 Some outcomes were reported in the second National Health Services (NHS) Atlas of Variation.17 However, much of the methodology from the audit was not reported, and the reports were of each cycle rather than reviewing the whole process. The purpose of this article is to assess whether a Quality Improvement Programme, based upon government recommendations, which involved the setting of standards for pain clinics, a suite of interventions to improve care and a re-audit, led to improvement. To achieve this, we have reviewed and revised the original data from all four reports, re-presented the data in the format of a recent systematic review of such surveys4 and explained the methods used to deliver the audit. Additional data not reported in any report include the number of patients seen and a more complete data set from providers as 30 missed the deadline for the follow-up report. The Baseline Audit reported by centre rather than by provider, which was not in line with reporting requirements, made it difficult to make meaningful comparisons. This article therefore looks at the impact and implementation of the audit and allows comparisons with other national surveys.

Methods

Context

The National Pain Audit’s brief was to look at case mix, service organisation and outcomes of care including patient safety and patient experience within the NHS of England and Wales, which both provide care free at the point of delivery, but differ in waiting times, targets and system integration. The English NHS is delivered based upon competition and choice of providers, whereas the Welsh NHS is integrated in delivery. Controversial National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance was produced on low back pain during this period, emphasising the importance of multidisciplinary care and reducing emphasis on medical treatments.18

Quality improvement interventions

The CMO of England’s and Welsh government’s recommendations were reviewed and those deemed feasible were implemented as an improvement programme. This was led by the British Pain Society. The programme consisted of feedback of National Pain Audit results to patients, politicians and policy-makers through the Chronic Pain Policy Coalition, regular newsletter updates, development of specific best practice pathways,19 revised speciality standards,20,21 population data on chronic pain from the Health Survey for England,22 a roadshow to all regions in England and Wales, commissioning guidance,23 a pain summit that brought together many stakeholders24 and linkage of audit results to NHS Choices, the main public source of information on NHS providers and treatments available in England.

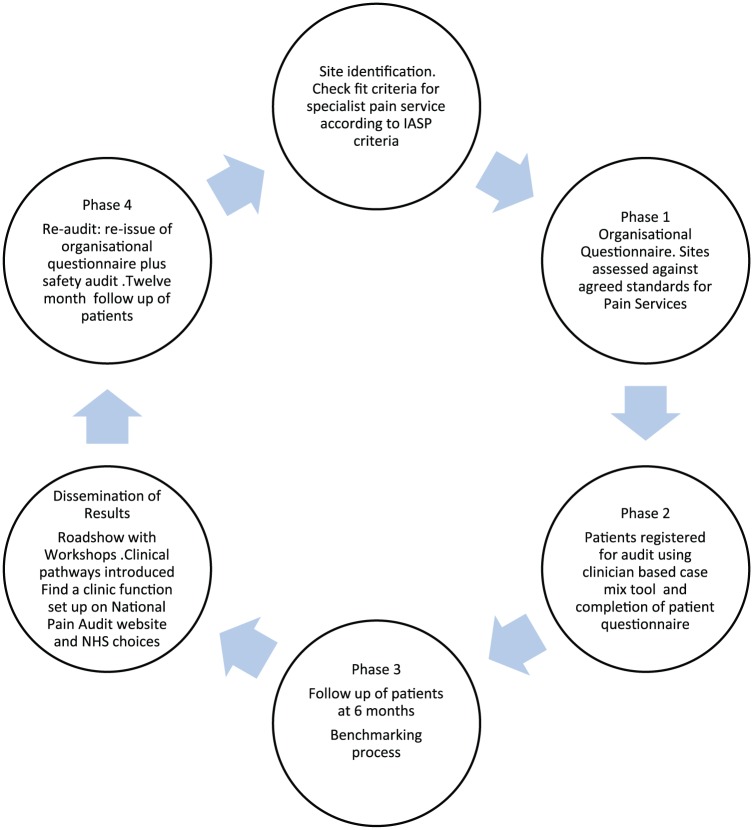

A Donabedian approach was taken to examine organisational structures, care processes and clinical effectiveness.25 Structure of services and processes of care were measured by direct questions. Both Departments of Health signed off the approaches and reviewed the recommendations made, and outcomes were assessed by the National Audit oversight board. Figure 1 shows the complete Quality Improvement Programme and Evaluation which covered the period 2010–2014.

Figure 1.

Audit cycle undertaken by the National Pain Audit 2010–2014.

Inclusion criteria – identification of services

During the Baseline Audit (Phase 1), specialist pain services were initially located through searching England’s national administrative hospital admission database (Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)) to identify services with the treatment function code 191 for Pain Management and through British Pain Society newsletters requesting contact. These services were sent an organisational questionnaire to complete. For the Follow-up Audit (Phase 4), the organisational re-audit, the NHS Choices website that hosts all NHS providers in England was searched for mention of specialist pain services and then contact was made and a further organisational questionnaire sent. Services were reported by the responsible provider organisation rather than by individual clinics, in line with reporting standards from the Health Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP).

Exclusion criteria

Services were excluded if they were clearly non-specialist providers, non-NHS providers or were unable to self-classify into type of pain facility.1

Audit standards

Audit standards were derived from the Royal College of Anaesthetists’ General Provision of Anaesthetic Services guidance chapter on Chronic Pain Services,20,21 IASP guidelines on pain services and waiting times1,2 and, for the follow-up Report, the National Patient Safety Agency (Table 1).26 Clinicians were asked to assign International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes to the primary condition of patients completing the Phase 2 questionnaire. For the additional work on coverage of services, population data were calculated from Office of National Statistics tables.27

Table 1.

Audit standards assessed by the first National Pain Audit.

| Standard | Indicator type | Justification | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type of clinic (IASP definition) | Structure | Evidence for multidisciplinary care | International Association for the Study of Pain guidance1 |

| 2 | Waiting times | Outcome | Key performance indicator nationally Evidence for waiting times impact on health |

18-week referral to treatment times (Baseline Audit) IASP waiting time standard2 (Follow-up) |

| 3 | Multidisciplinary staffing | Structure | Internationally recognised standard for pain services | IASP treatment facilities guidance1 |

| 4 | Availability of pain services per head of population | Structure | Key concern worldwide | Systematic review recommendations4 |

| 5 | Treatments available at pain services | Structure | Availability of evidence-based multidisciplinary care, back-up facilities and wider specialist support to the community | British Pain Society Map of Medicine treatment pathways19 |

| 6 | Attributes of pain treatment facilities | Structure | Multidisciplinary care check that personnel match the definition | Systematic review recommendations4 |

| 7 | 100% patients diagnoses assigned an ICD-10 code | Outcome | Diagnosis determines treatment pathway | NHS Information Standards |

| 8 | 100% of clinics had protocols in place to manage high risk areas of practice | Process | Standard requirement of NHS providers | National Patient Safety Agency26 |

| 9 | Education Programme | Structure | As a specialist service, should be providing best practice on managing pain to non-specialists | IASP treatment facilities guidance2 |

IASP: International Association for the Study of Pain; ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision; NHS: National Health Services.

Data collection

Data for the items given in Table 1 were collected from providers of pain services via an Excel spreadsheet with sign-off by their audit departments. For consistency, services were analysed by provider in line with National Audit guidance. This produced some discrepancies from the first National Audit report where analysis was by individual clinic.

Data analysis

Reporting recommendations from the systematic review of multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment facilities were followed,4 and the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) checklist for quality improvement studies followed.28 The χ2 test was used to test for significant differences in important variables. Free text diagnoses were mapped to ICD codes by national pain coding leads.

Data validation

Data were compared with HES in England. It was not possible to obtain the Welsh equivalent (Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW)). Data were also uploaded to a public-facing website, and initial outcomes were reported to the clinics. Items were cross-referenced for inaccuracies.

Ethical considerations

As a Quality Improvement Programme, National Audits do not require an ethics review. The use of data and the audit were overseen by HQIP. The evaluation was overseen by a scientific committee and an independent governance group including lay members.

Results

Identification of providers and response rates

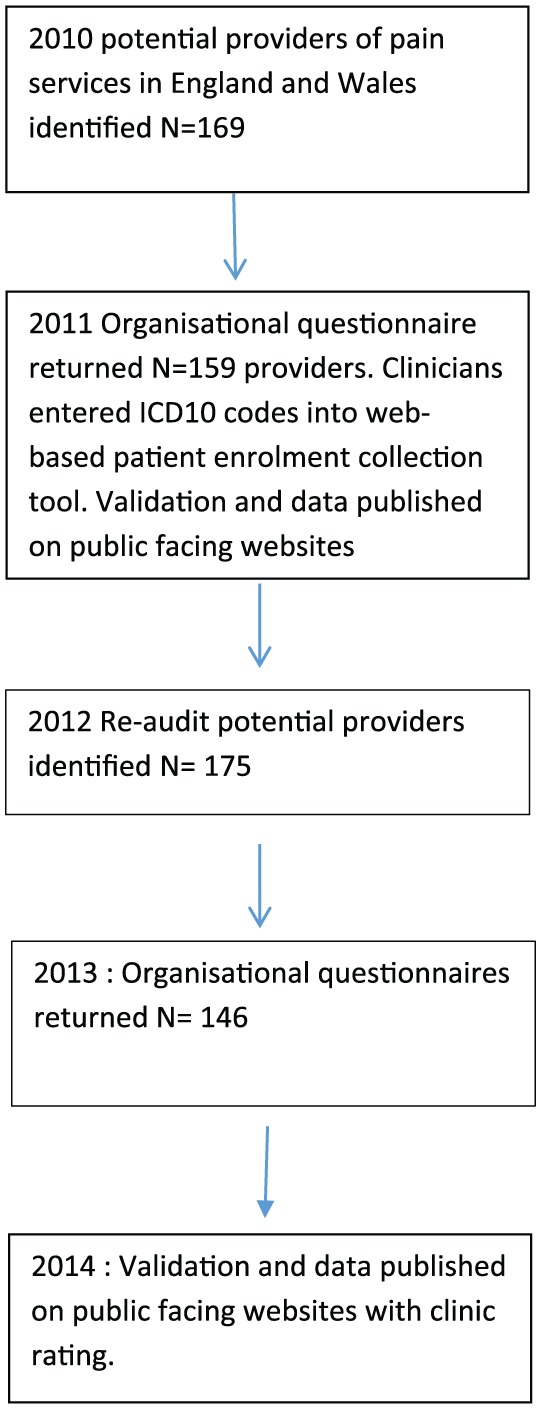

Figure 2 shows flow through the audit. For the Baseline Audit, the first search methodology found 169 clinics, and responses were received from 159 clinics, a 94% response rate. For the Follow-up Audit, the follow-up organisational questionnaire, we identified services in England using hand searches of NHS Choices. NHS Wales provided a list. These identified 175 providers of specialist pain care in England and Wales, in a variety of settings both in and out of hospital. In total, 146 providers responded to the Follow-up Audit, a response rate of 83%. Nineteen providers identified as having a pain service did not submit a return (10%), and there was uncertainty over the status of another 10 providers who did not respond and it could not be ascertained if they ran a pain service.

Figure 2.

Data collection flow through the audit.

Data validation

HES data (England only) identified 133 providers with outpatient data using the specialty code 191: Pain Management. In total, 26 providers in the Baseline Audit were not identified through HES, but provided specialist pain services. This may have been due to incorrect coding of the clinics. We were unable to cross-check services in Wales using PEDW; however, the Welsh government had a record of all services.

Standard 1: clinics were classified according to IASP classification of pain clinics

As reported in Table 2, in the Baseline Audit, all clinics were able to self-classify using the IASP clinic type classification guideline. In the Follow-up Audit, 19 (13%) did not self-classify their clinic type.

Table 2.

Types of clinics, staffing and treatments available in pain clinics services at each audit round (N = total number of responses for that section*).

| Baseline (2010) | Follow-up (2013) | Chi squared test/P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Clinic | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Modality-oriented | 11 (7) | 3 (3) | N/A |

| Pain Clinic | 33 (21) | 5 (5) | N/A |

| Total Non-multidisciplinary | 44 (28) | 8 (7) | N/A |

| Multidisciplinary** Pain Clinic | 76 (49) | 71 (65) | N/A |

| Multidisciplinary** Pain Centre | 35 (23) | 30 (28) | N/A |

| Total Multidisciplinary ** | 111 (72) | 101 (93) | <0.001 |

| Total Clinic Type | 155 | 109 | |

|

Staffing |

N=124 (%) |

N=133 (%) |

|

| Psychologist | 60 (49) | 80 (64 ) | 0.058 |

| Physiotherapist | 67 (54) | 89 (67) | 0.003 |

| Consultant | 89 (72) | 113 (85) | 0.010 |

| Incomplete responses | 40 (32) | 20 (22) | |

| True multidisciplinary staffing (minimum) | 39 (32) | 75 (56) | <0.001 |

|

MDT meetings |

70 (56) |

117 (88) |

<0.001 |

|

Treatment Modality |

N=146 (%) |

N= 116 (%) |

|

| Interventional procedures | 130 (88) | 111 (96) | 0.049 |

| Implants | 43 (30) | 31 (28) | 0.626 |

| Pain Management Programme | 122 ***(86) | 71 (61) | <0.001 |

N varied between each section due to missing data returns.

Minimum staffing of physician, psychologist and physiotherapist.

May be inaccurate as question asked about specialist rehabilitation rather than distinguishing psychologically based rehabilitation from standard rehabilitation.

Standard 2: waiting times should be appropriate and evidence-based

Baseline Audit (Phase 1): 80% of clinics in England in the Baseline Audit reported meeting the government target for England of 18 weeks to first appointment, and 2.5% explicitly did not meet the standard. In Wales, where targets are somewhat different, 50% of clinics achieved 18 weeks for elective waits, with a lower completion rate of 70%. For clinics failing government targets, the median wait was 20 weeks in England and 33 weeks in Wales.

Follow-up Audit (Phase 4): IASP waiting time recommendations were used in this round2 as they have an evidence base for pain and we became aware of the potential consequence of a fine for declaring failing a government target. However, only 49 (38%) services responded to this. For routine referrals, 25 (43% of those who responded to this question) were able to offer a first appointment within the recommended time of 8 weeks, with a median wait of 15 weeks.

Standard 3: clinics should be multidisciplinary

The majority of clinics, 111(72%), self-rated themselves as multidisciplinary in the Baseline Audit according to IASP criteria, rising to 101 (93%) at the Follow-up Audit. (Table 2)

Standard 4: multidisciplinary pain services per head of population in line with other first world countries

In total, 100 services, across the range of types of clinic, provided information on number of patients seen per annum – an average of 0.25% of the total population in 1 year in England (Table 3). Adjusting for non-responders (based on the size of the populations they serve and the numbers seen in responding clinics), a rough estimate would be that 0.46% of the population was seen. As only 64% of clinics were multidisciplinary, then 0.25% of the England and Wales population is estimated to attend a multidisciplinary pain clinic every year.

Table 3.

Percentage of patients seen at a pain clinic per total head of population in England.

| Region | Number seen in pain clinic | Population | % seen |

|---|---|---|---|

| East of England | 18,043 | 5,954,200 | 0.303 |

| East Midlands | 6927 | 4,598,700 | 0.151 |

| North West | 20,456 | 7,103,300 | 0.288 |

| London | 21,849 | 8,416,500 | 0.260 |

| South West | 11,253 | 5,377,600 | 0.209 |

| South East | 17,076 | 8,792,600 | 0.194 |

| North East | 8431 | 2,610,500 | 0.323 |

| West Midlands | 8577 | 5,674,700 | 0.151 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 10,083 | 5,337,700 | 0.189 |

| England total | 134,223 | 53,865,800 | 0.249 |

Source: Office of National Statistics – Population Estimates for the United Kingdom, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, 2013.

Services also estimated that 95 services responded to this question, with a mean estimate of 0.3% of the population seen.

Standard 5: multimodal treatments should be available at services

Multimodal treatments are more than one type of treatment being delivered, for example, physiotherapy and an injection. Ninety-three percent of services in the Baseline Audit and 97% in the Follow-up Audit self-reported that they offered multimodal treatment. The types of treatments available are shown in Table 2. Nearly all services provided interventional pain management. In the Follow-up Audit, 61% reported providing a pain management programme; in the Baseline Audit, nearly all services appeared to provide some form of a pain management programme, but the question asked about specialist rehabilitation treatments so may be confused with other approaches. In total, 72% of those providing pain management programmes had a qualified cognitive behavioural therapy practitioner delivering the programme. Implants (neurostimulation and infusion catheters) were available in 30% of services.

Standard 6: attributes of pain treatment facilities – core multidisciplinary staff should be available

It was noted that there was a significant discrepancy between services’ self-report and the actual staffing, defined by the audit group comprising at minimum a physician, physiotherapist and psychologist, who together could deliver all major treatment components. Generally, completion rates of questions on staffing levels were high, allowing some understanding of whether staffing levels were matched to need (Table 3). By the time of the Follow-up Audit, there was significant improvement in the reported availability of the specific multidisciplinary staff needed. Most services held multidisciplinary team meetings, and 14% offered multispecialty clinics aimed at the most complex cases.

Standard 7: ICD codes should be correctly assigned for diagnosis

At the Baseline Audit, clinicians were able to assign codes for 6430 patients (67%). They were unable to code 3000 patients into diagnostic groups and used free text instead, which, when reviewed by the clinical expert group, could nearly all be mapped to a code. It appeared that sometimes clinicians were entering the co-morbidity contributing to chronic pain (e.g. ‘arthritis’) rather than pain as a condition in itself.

Standard 8: protocols should be in place to manage risk

This was also reported in the Third Report of the National Pain Audit.16 Of the 121 providers that responded, 53 (44%) reported having a suicide risk assessment protocol. Fifty-three (44%) had a clear process for acting on a wrong diagnosis being made: all providers reported this as a serious untoward event. A process for recording prescribing errors was reported by 114 (94%). One hundred and four services (86%) had pain prescribing guidance, with 94 services (77%) having specific opioid prescribing guidance. Of those providing interventional pain therapy, 88% had a process in place for managing accidental misplacement of an injection, with 92% having a process in place to manage adverse events with interventional pain therapy.

Standard 9: education to non-specialists and Quality Improvement Programmes should be provided

Most providers met this standard. Ninety-three percent provided a clinical teaching programme for health professionals. Eighty-two percent stated that they carried out a regular audit of clinical practice.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first time, worldwide, that pain services have gone through an improvement cycle on a national scale. The National Pain Audit managed to characterise most pain clinics in England and Wales in terms of types of clinics, case mix, processes in place to manage risk, patient experience and clinical outcomes. Outcomes from this audit enabled clearer standards to be published and developed for routine inspection by regulators.29

The quality-of-service provision improved over the audit period. Sound patient safety procedures are found in nearly every clinic. The proportion of services with reported truly multidisciplinary staffing rose from 32% at Baseline to 56% at Follow-up (p < 0.001). Hogg in Australia and Peng in Canada reported that 79% and 39%, respectively, were multidisciplinary clinics; this was by self-report alone and so it is difficult to draw comparisons.30,31 Multidisciplinary care has been shown to improve general medical inpatient hospital-based outcomes.32 Multidisciplinary pain care focusing on self-management skills acquisition has also been found to be effective.33 This is encouraging and was a key message of the Quality Improvement Programme although may also have been related to national guidance on the management of low back pain. However, professional controversy over the evidence base was not resolved until the production of clinical pathways.

Methodological challenges included difficulties with identifying services: HES data captured many services, but at least 11 were missing. Hand searching for clinics on the NHS Choices website and searching for a pain clinic on providers’ websites proved to be the best way of identifying clinics. Obligatory use of the relevant specialty code within the national hospital administrative database (HES) would make identification of services much easier. Fashler et al.4 highlighted the variety of identification methods used by each large pain facility survey; some standardisation is needed to avoid selection bias. Considerable liaison was needed to verify eligibility and confirm data. Data availability on an open website proved very useful.

For many services, there was significant discrepancy between their self-description as a multidisciplinary clinic and the staffing required to provide multidisciplinary care. Exact staffing depends on feasibility, potential scope of practice and workforce supply.34 At the time, only medical staff had a clear, competency-based training programme. No other survey has attempted to assess this, and there are no comparators. Given the discrepancy, future surveys ought to ask exactly which staff are present. Using two methods, we estimated that 0.25–0.3% of the total population was seen at multidisciplinary clinic. This is somewhat lower than elsewhere;4 the reasons for this require further research.

Government waiting time targets of 18 weeks in England were largely met by services. However, the maximum waiting time recommended by the IASP for routine cases is 8 weeks, as deterioration is found in some cases from 5 weeks onwards.35 A more detailed prioritisation of cases such as that recommended in Norway, based upon condition and complexity, may enable clinics to reduce waiting times.36

One major difficulty for clinicians was entering diagnostic codes. Perhaps, selecting from the 600 ICD-10 codes for long-term pain is simply too overwhelming. The International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision (ICD-11) revision has proposed and tested new codes specifically for chronic pain, which may increase use.37 Treatments were also confusing, difficult to classify and require better information standards.

Conclusion

A Quality Improvement Programme for specialist pain services in England and Wales was successfully delivered and measured. Sound patient safety processes are in place in nearly every service. Improvement in multidisciplinary provision occurred over the time period. However, waiting times did not improve and coding for diagnoses and treatments require improvement. Future programmes should focus on these areas and ensuring multidisciplinary care continues to grow.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yvonne Silove, Health Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP), Professor Richard Langford for oversight of the audit and the British Pain Society President.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: C.P. and A.C.d.C.W. declared no conflicts of interest. On behalf of his institution, B.H.S. received funding from Pfizer Ltd (£84,600) and for research into the genetics of pain; and travel and accommodation to attend an EFIC pain conference from Napp Pharmaceuticals. A.B.’s unit, the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London, receives grant income from Dr Foster (a Telstra Health company), which facilitated the data collection in the audit described in the manuscript.

Ethical approval: The Health Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) acted as data controller for the duration of the audit and oversaw the publication of the reports from which these data are taken.

Funding: The National Audit project was funded by the Departments of Health in England and Wales.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study for linkage to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data.

Trial Registration: Not applicable as this was not a clinical trial.

Guarantor: CP.

Contributorship: CP researched the literature and conceived the study. CP, ACdCW and AB were involved in protocol development, gaining approval, patient recruitment and data analysis. CP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Cathy Price  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0111-9364

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0111-9364

References

- 1. Pain Treatment Services. International Association for the Study of Pain, 2009, http://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1381 (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 2. IASP Task Force on Wait-Times, www.dgss.org/fileadmin/pdf/Task_Force_on_Wait-Times.pdf (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 3. Roehr B. Trump declares opioid public health emergency but no extra money. BMJ 2017; 359: j4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fashler SR, Cooper L, Oosenbrug ED, et al. Systematic review of multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment facilities. Pain Res Manag 2016; 2016: 5960987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker DW. History of the joint commission’s pain standards. Lessons for today’s prescription opioid epidemic. JAMA 2017; 317(11): 1117–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gordon DB, Dahl JL. Quality improvement challenges in pain management. Pain 2004; 107(1–2): 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG): services for patients with pain, HMSO London, 2000. London: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Getting to GRIPS with chronic pain in Scotland: NHS QIS, 2007, http://www.nopain.it/file/GRIPS_booklet_lowres.pdf

- 9. Donaldson L. 150 years of the Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer: On the state of public health 2008: Pain Breaking Through the Barrier, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090430160249/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/AnnualReports/DH_096206 (2009, accessed 19 November 2018).

- 10. Service Development and Commissioning Directives Chronic: Non-Malignant Pain. Welsh Assembly Government, 2008, http://www.wales.nhs.uk/documents/chronicpaine.pdf

- 11. Pink D, Bromwich N. National institute for clinical excellence (Great Britain): principles for best practice in clinical audit. London: Radcliffe Publishing, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kerns R. Improving care across hundreds of facilities: the veterans health administration’s national pain management strategy. In: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (ed.) Improving the quality of pain management through measurement and action. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleeland CS, Reyes-Gibby CC, Schall M, et al. Rapid improvement in pain management: the Veterans Health Administration and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Collaborative. Clin J Pain 2003; 19(5): 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hooten WM, Timming R, Belgrade M, et al. Assessment and management of chronic pain. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), 2013, p.105. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Pain Audit: Reports 2011 to 2012, https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/national-pain-audit-reports-from-2011-to-2012/ (accessed 19 August 2018).

- 16. The National Pain Audit Third Report, https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_npa_2013_safety_outcomes.pdf (accessed 19 August 2018).

- 17. NHS Atlas of Variation, volume 2, 2011, https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/atlas-of-variation (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 18. NICE. Low back pain in adults: early management (clinical guideline CG88), 2009, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88 (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 19. Colvin LA Rowbotham RJ. I. Managing pain: recent advances and new challenges. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111(1): 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia services for chronic pain management 2014. Guidelines for the provision of anaesthetic services, https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/GPAS-FULL-2014_3.pdf (2014, 19 November 2018).

- 21. Royal College of Anaesthetists. Raising the standard: a compendium of audit recipes (3rd edition) 2012, https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/ARB2012 (accessed 20 November 2018).

- 22. Bridges S. Chronic pain. Health Survey for England, 2011, https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub09xxx/pub09300/hse2011-ch9-chronic-pain.pdf (accessed 19 November 2018).

- 23. Pain management services: planning for the future guiding clinicians in their engagement with commissioners, file:///C:/Users/cmp1v07/Downloads/RCGP-Commissioning-Pain-Management-Services-Jan-14.pdf (accessed 19 August 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pain Summit Report, 2011, https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_pain_summit_report.pdf (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 25. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1965; 44(3): 166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Patient Safety Agency (Corporate Office), www.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/ (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 27. Office for National Statistics National Records of Scotland Northern Ireland Statistics Research Agency, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/2014-06-26 (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 28. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25: 986–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthestists. Core Standards for Pain management Services in the UK, 2015, http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/CSPMS-UK-2015-v2-white.pdf (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 30. Hogg MN, Gibson S, Helou A, et al. Waiting in pain: a systematic investigation into the provision of persistent pain services in Australia. Med J Aust 2012; 196(6): 386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, et al. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Can J Anaesth 2007; 54(12): 977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woolhouse I, Treml J. The impact of consultant-delivered, multidisciplinary, inpatient medical care on patient outcomes. Clin Med 2013; 13(6): 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pike A, Hearn L, Williams AC. Effectiveness of psychological interventions for chronic pain on health care use and work absence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2016; 157: 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Conway J, Higgins I. Literature review: models of care for pain management, http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PainManagement/Documents/appendix-3-literature-review.pdf (accessed 28 August 2018).

- 35. Lynch ME, Campbell F, Clark AJ, et al. A systematic review of the effect of waiting for treatment for chronic pain. Pain 2008; 136(1–2): 97–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hara KW, Borchgrevink P. National guidelines for evaluating pain – patients’ legal right to prioritised health care at multidisciplinary pain clinics in Norway implemented 2009. Scand J Pain 2010; 1(1): 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015; 156(6): 1003–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]