Significance

Dysregulated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response contributes to the pathogenesis of myriad diseases. The molecular pathways leading to ER stress-induced cell death are well characterized; however, much less is known about how cells suppress excessive ER stress response to avoid apoptosis and restore homeostasis. Using a CRISPR-based loss-of-function genetic screen, our study uncovered multiple suppressors of ER stress response. These suppressors include a polycomb protein complex that directly inhibits the expression of the transcriptional factor central to ER stress-induced cell death and a microRNA that targets IRE1, a canonical ER stress pathway component. Our study reveals regulatory mechanisms that ameliorate potentially damaging stress response and provides potential therapeutic targets for pathologies whose etiology is linked to overactive ER stress response.

Keywords: UPR (unfolded protein response), proteotoxicity, environmental toxicant, genetic screen

Abstract

Sensing misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), cells initiate the ER stress response and, when overwhelmed, undergo apoptosis. However, little is known about how cells prevent excessive ER stress response and cell death to restore homeostasis. Here, we report the identification and characterization of cellular suppressors of ER stress-induced apoptosis. Using a genome-wide CRISPR library, we screen for genes whose inactivation further increases ER stress-induced up-regulation of C/EBP homologous protein 10 (CHOP)—the transcription factor central to ER stress-associated apoptosis. Among the top validated hits are two interacting components of the polycomb repressive complex (L3MBTL2 [L(3)Mbt-Like 2] and MGA [MAX gene associated]), and microRNA-124-3 (miR-124-3). CRISPR knockout of these genes increases CHOP expression and sensitizes cells to apoptosis induced by multiple ER stressors, while overexpression confers the opposite effects. L3MBTL2 associates with the CHOP promoter in unstressed cells to repress CHOP induction but dissociates from the promoter in the presence of ER stress, whereas miR-124-3 directly targets the IRE1 branch of the ER stress pathway. Our study reveals distinct mechanisms that suppress ER stress-induced apoptosis and may lead to a better understanding of diseases whose pathogenesis is linked to overactive ER stress response.

Maintaining protein homeostasis is critical for the fitness and survival of all living cells. Newly synthesized proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) must be correctly folded before being transported to subcellular destinations. About 30% of all newly synthesized proteins are misfolded (1), and exposure of cells to environmental proteotoxicants such as arsenic (As) further increases protein misfolding (2, 3). Misfolded proteins are nonfunctional, prone to aggregation, and often toxic to cells (4). As a result, high levels of misfolded proteins contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cancer, and most neurodegenerative disorders (5).

As a major site of protein synthesis, the ER is capable of sensing and responding to the accumulation of misfolded proteins, a condition widely known as ER stress. The elaborate cellular response to ER stress, also known as unfolded protein response (UPR), is mediated by three ER-resident transmembrane proteins: PERK, IRE1, and ATF6 (6). In the presence of ER stress, misfolded proteins bind and sequester the molecular chaperone BiP/GRP78 away from PERK, IRE1, and ATF6, leading to activation of these three molecules and their respective downstream signaling cascades (7). Activation of PERK induces phosphorylation of eIF2α and up-regulation of ATF4, a potent transcription factor (8). Activation of IRE1 triggers the cleavage of XBP1 mRNA into its transcriptionally active spliced form XBP1s (9, 10). ATF6 activation results in translocation to the Golgi, where it is cleaved by proteases into an active form ATF6(n), another potent transcription factor (11). As transcriptional activators, ATF4, XBP1s, and ATF6(n) up-regulate a myriad of UPR target genes, including antioxidant genes, ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery, ER chaperones, and autophagy pathway genes (12–14), to alleviate ER stress. In addition, PERK-induced eIF2α phosphorylation attenuates global protein translation to prevent the introduction of additional misfolded proteins (8). Together, these responses relieve disturbances in the ER and help restore proteohomeostasis.

Sustained high levels of ER stress, however, trigger apoptosis (15). The ER stress-induced apoptosis is largely mediated through CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein, also known as DDIT3), the transcription factor that integrates signaling from all three branches of the ER stress pathway. XBP1s, ATF6(n), and ATF4 all can bind to the CHOP promoter to increase its expression (16). Up-regulation of CHOP triggers apoptosis mainly by increasing the ratio of pro- vs. antiapoptotic proteins (16, 17). For example, CHOP increases the expression of the proapoptotic proteins BIM and PUMA, and, at the same time, down-regulates the expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein (18–20). These molecular events ultimately lead to the activation of apoptotic caspases (e.g., caspase 3, 8, and 9) to cause cell death (21).

While the elaborate signaling pathways leading to ER stress-induced cell death have been well characterized, much less is known about how cells suppress excessive ER stress response to prevent unwanted apoptosis. In this study, using a genome-wide CRISPR loss-of-function screen coupled with a CHOP up-regulation–based ER stress cell model, we identified and characterized multiple genes, including members of polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC.1), as well as microRNAs, as suppressors of ER stress response and associated cell death. Our study reveals distinct mechanisms that suppress ER stress response and apoptosis, and provides insights into diseases whose pathogenesis is linked to abnormal ER stress response and cell death.

Results

Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Identifies Suppressors of ER Stress Response.

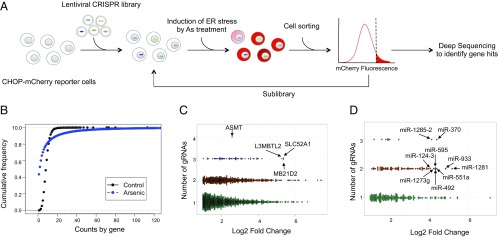

We previously developed an ER stress cell model that harbors a fluorescence reporter (mCherry) under the control of the CHOP gene promoter (22). These CHOP-mCherry reporter cells respond in a dose-dependent manner to known ER stressors such as As and tunicamycin (Tm) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). We transduced the CHOP-mCherry reporter cells with a genome-wide lentiviral CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (KO) library that targets ∼19,000 protein-coding genes (six guide RNAs [gRNA] per gene) and ∼1,800 miRNAs (four gRNAs per miRNA) (23). We used the lentiviral library at a relatively low multiplicity of infection (MOI = 0.3) to minimize superinfection of the reporter cells. After selection for stable CRISPR viral integration, the final cellular library contains an estimated ∼4 × 107 independent viral integration events. This represents about 300-fold coverage of ∼120,000 CRISPR guides in the starting viral library. To identify suppressors of the ER stress response, the CRISPR KO library cells were treated with As, which as a ubiquitous metal toxicant activates all three pathways of the ER stress response and induces apoptosis (24, 25). Moreover, chronic exposure to high levels of As found in certain geographical areas in the world has been shown to be associated with increased risk of developing ER stress-associated diseases (26, 27). As-treated cells were then subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate the bright cell populations that express a high amount of mCherry (Fig. 1A), as CRISPR knockout of genes that normally suppress CHOP up-regulation would lead to an increase in mCherry expression. To allow for identification of CRISPR cell populations with increased intensity of fluorescence, we used a screen condition (treatment of 5 μM As for 15 h) that initially induced a moderate increase (approximately two-fold) in the mean mCherry fluorescence. Sorted mCherry-bright cells were then allowed to repopulate once, followed by another round of ER stress induction and cell sorting (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). To minimize nonspecific bystander effect, we constructed a sub-CRISPR library using guides amplified from the genomic DNA of cells isolated from the second-round sorting (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Compared with vector control, the sublibrary cells exhibited greater mCherry fluorescence at basal levels. The sublibrary cells were again subjected to As treatment and cell sorting (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). After As treatment, there was even more improved separation in CHOP-mCherry signals, suggesting that the screen selected the population of cells with gRNAs conferring ER stress response suppression (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). In the final round of sorting, we isolated the upper 50% mCherry-bright cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Fig. 1.

Identification of ER stress suppressors using genome-wide CRISPR screen. (A) Scheme of CRISPR screen. CHOP-mCherry reporter cells were transduced with lentiviruses produced from the genome-wide CRISPR library. Stably transduced reporter cells were treated with ER stress inducer As (5 µM) for 15 h, and strong responders with higher mCherry fluorescence (upper 10%) were isolated by FACS. The isolated cells were regrown for enrichment and subjected to another round of induction. At the end of the second round of induction and enrichment, the genomic DNA of the strong responders was extracted and the region harboring the gRNAs was amplified and cloned into a lentiviral vector to generate a CRISPR sublibrary. A new batch of reporter cells was transduced with the CRISPR sublibrary for another round of As treatment. Finally, the strong responders (50%) were FACS sorted and the genomic DNA was subjected to deep dequencing and bioinformatics analysis for the identification of target genes. (B) Cumulative frequencies of gRNAs from sorted and control (unsorted, original library) cells. (C and D) Plots showing fold change of gRNAs versus number of distinct gRNAs for protein-coding genes and miRNAs, respectively. Gene names of top hits are indicated.

To identify gene hits whose CRISPR knockout leads to the phenotypic change (higher mCherry induction in response to ER stress), we extracted genomic DNA and PCR-amplified the CRISPR guide sequences from the sorted population, along with guide sequences from unsorted control library cells, for deep sequencing. We analyzed sequencing data to identify guides and their corresponding target genes that were enriched in sorted cells compared to control unsorted library cells. Deep sequencing results revealed a significant reduction in the diversity of gRNAs in the sorted population (Fig. 1B). Using criteria that include greater than 2.5 log2 fold change and the presence of at least two enriched guides per gene, we identified a total of 361 hits, including 324 protein-coding genes and 37 miRNAs (Fig. 1 C and D and Datasets S1 and S2). Ontological analysis of the protein-coding hits using the NIH Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Functional Annotation tool showed enrichment of genes that function in apoptosis, proliferation, cell growth and size, and cellular responses to stress and other stimuli (Dataset S3). DAVID pathway analysis of target genes of miRNA hits with fold change greater than 10 revealed presence of gene sets involved related to chaperone-mediated protein folding and cell death (Dataset S4).

Loss of L3MBTL2 Increases Basal and ER Stress-Induced CHOP Expression.

Among the top protein-coding gene hits identified by the screen are ASMT (acetylserotonin methyltransferase), SLC52A1 (solute carrier family 52 member 1), L3MBTL2 (lethal(3)malignant brain tumor-like 2), and MB21D2 (mab 21 domain containing 2). Among the top hits, only MB21D2 has no annotated function. ASMT is an enzyme that catalyzes the final step in melatonin biosynthesis (28) while SLC52A1 is a transmembrane protein that functions as a riboflavin transporter (29) and belongs to the solute carrier (SLC) gene superfamily (30). On the other hand, L3MBTL2 is a component of the polycomb repressive complex that possesses transcriptional repressive activity (31). We proceeded to validate these top protein-coding gene hits by first generating individual CRISPR gene knockouts in the CHOP-mCherry reporter cells. For each of these gene hits, we transduced the reporter cells with lentiviruses containing two independent CRISPR gRNAs. We then measured As-induced CHOP expression in the KO cells using flow cytometry. Only cells with gRNAs for two of the gene hits, SLC52A1 and L3MBTL2, showed higher mCherry expression, both at basal level and in response to As treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). This was not the case for either ASMT or MB21D2 KO cells. SLC52A1 KO cells showed modest shifts in mCherry fluorescence compared with the more obvious increases in mCherry expression exhibited by L3MBTL2 KO cells after arsenic treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The function of SLC52A1 in the ER stress response is not clear, although there are reports suggesting that riboflavin deficiency causes ER stress (32, 33). Possibly, SLC52A1 KO cells are deficient in riboflavin due to its impaired riboflavin transport system which causes ER stress and may explain the increase, although modest, in CHOP expression. In addition to SLC52A1, the screen has identified other members of the SLC superfamily (namely SLC1A6, SLC16A8, SLC22A10, SLC26A3, SLC3913, SLC44A2, SLC44A5, and SLCO1B3), although they were ranked lower using our priority criteria (Dataset S1). On the other hand, both gRNAs for L3MBTL2 KO cells produced the most robust increase in mCherry expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D) both at basal and As-treated states. Thus, we decided to further investigate L3MBTL2’s potential role as suppressor of the ER stress response.

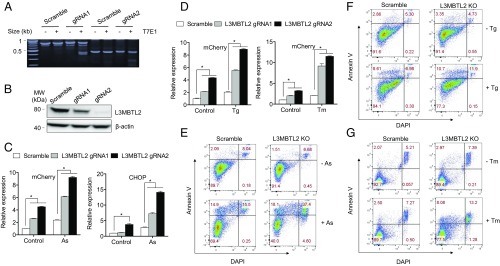

Both L3MBTL2 gRNAs led to efficient gene editing as evidenced by the T7E1 cleavage assay which detects mismatched DNAs such as indels (insertions or deletions) at the gRNA targeting sites (Fig. 2A). Similarly, Western blotting showed significant reduction in L3MBTL2 protein expression in the reporter cells stably transduced with the CRISPR guide RNAs (Fig. 2B). The incomplete knockout of L3MBTL2 in the cells is likely because we used pooled stable cells rather than single clones. Compared with the control cells transduced with a scrambled gRNA, the L3MBTL2 KO cells exhibit higher mCherry at both basal level and in response to As treatment (Fig. 2 C, Left). Consistent with augmented mCherry expression, the endogenous CHOP mRNA expression was also increased in L3MBTL2 knockout cells at both basal level and in response to As treatment (Fig. 2 C, Right).

Fig. 2.

Loss of L3MBTL2 increases CHOP expression and sensitizes cells to ER stress-induced apoptosis. (A) Analysis of CRISPR knockout using the T7E1 assay. L3MBTL2 knockout cells were generated using the top two gRNAs identified in the CRISPR screen. DNA cleavage indicating mismatch and mutation induced by the two gRNAs targeting L3MBTL2 was detected by T7E1 assay. (B) Western blot analysis showing significant reduction in the levels of L3MBTL2 in CHOP-mCherry reporter cells transduced with lentiviruses containing gRNAs targeting L3MBTL2. (C) Loss of L3MBTL2 increases the mean CHOP-mCherry fluorescence and endogenous CHOP mRNA expression as assessed by flow cytometry (16 h, 5 µM As) and qRT-PCR (6 h, 5 µM As), respectively. β-Actin was used as the internal control for qRT-PCR. Error bars = SEM (n = 3); *P < 0.05. (D) Loss of L3MBTL2 in reporter cells further increases the mean CHOP-mCherry flourescence in Tg (8 h, 100 nM) or Tm (16 h, 500 ng/mL)-treated cells as assessed by flow cytometry. DMSO and water were used as vehicle controls for Tg and Tm, respectively. Error bars = SEM (n = 3); *P < 0.05. (E–G) Loss of L3MBTL2 sensitizes cells to ER stress-induced apoptosis. (E) Representative Annexin V and DAPI staining of scrambled control or L3MBTL2 KO cells in the absence (−As, Upper) or presence of As treatment (+As, Lower). Scrambled control and L3MBTL2 KO cells were treated with 50 μM As or water for 24 h and harvested for Annexin V/DAPI staining analysis to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells. (F and G) Representative Annexin V and DAPI staining of scrambled control of L3MBTL2 KO cells treated with 1 μM Tg and 1 μg/mL Tm for 24 h. Annexin V positive cells, which are shown in the Upper quadrant of each graph, make up the apoptotic populations.

We next tested whether L3MBTL2 KO cells exhibit enhanced response to other ER stressors. We treated the KO reporter cells with thapsigargin (Tg) or Tm and measured mCherry expression. In the presence of Tg or Tm, the CHOP-mCherry fluorescence was greater in L3MBTL2 KO cells compared with controls (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, while Tg treatment augmented the expression of endogenous CHOP in KO cells, the levels of spliced xBP1 and ATF4 mRNAs, which are upstream of CHOP induction, did not significantly change between scramble and L3MBTL2 KO cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). These data indicate that L3MBTL2 is likely a suppressor of general ER stress response induced by diverse stimuli.

Loss of L3MBTL2 Sensitizes Cells to ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis.

Up-regulation of CHOP is associated with induction of apoptotic cell death. We next examined whether loss of L3MBTL2 increases apoptosis in the presence of ER stress. We treated control and L3MBTL2 KO cells with As for 24 h and then measured cell death using annexin V/DAPI staining, which can differentiate early apoptotic (annexin V positive, DAPI negative), late apoptotic cells (annexin V and DAPI positive), and necrotic (annexin V negative, DAPI positive) from live cells (negative for both annexin V and DAPI) cells (34). In the absence of As treatment, no significant difference in apoptosis was detected between KO and control cells (Fig. 2 E, Upper). After exposure to As, as expected, there was significant decrease in the percentage of live cells (negative for annexin V and DAPI) for both control and L3MBTL2 knockout cells (Fig. 2 E, Lower). However, the percentage of live cells was significantly lower in L3MBTL2 knockout cells (∼40%) than in control cells (69.4%) (Fig. 2E). The cell death was mostly due to apoptosis, as seen by greater percentage of late apoptotic cells (37.4%) in knockout cells than in scramble control cells (15.5%). Similarly, L3MBTL2 CRISPR knockout cells exhibited more apoptosis induced by Tg and Tm than the scramble control cells (Fig. 2 F and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). On the other hand, treatment with genotoxic stressors 5-fluorouracil or etoposide, which induce apoptosis via ER stress-independent pathways (35) did not result in greater increase in apoptosis in L3MBTL2 KOs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Together, these results show that loss of L3MBTL2 renders cells more susceptible to apoptosis induced by ER stress but likely not by other cellular stresses.

Loss of L3MBTL2-Interacting Protein, MGA, Increases CHOP Expression and Sensitizes Cells to ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis.

L3MBTL2 belongs to polycomb-group proteins (PcG), a family of proteins that commonly assemble as a complex possessing chromatin remodeling activities (31). Interestingly, at least four other gene hits (MGA, HDAC1, L3MBTL3, and SFMBT1) from our CRISPR screen are members of the PcG family (Dataset S1). One of the hits, MGA, encodes a protein known to interact with L3MBTL2 as part of PRC.1, which promotes a repressive chromatin environment to facilitate transcriptional gene silencing (31, 36). We therefore tested whether MGA, like L3MBTL2, also plays a role in suppressing ER stress-induced CHOP expression. We established MGA CRISPR KOs using the top two gRNAs identified by our screen. In the absence of a reliable antibody, the efficiency of MGA gRNA-induced gene editing was confirmed by T7E1 cleavage assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). We then treated MGA KO cells with ER stress inducers and assessed CHOP expression. Similar to L3MBTL2 KO cells, MGA KO cells exhibited higher CHOP-mCherry fluorescence and endogenous CHOP expression at both the basal level and in response to As (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Tg and Tm treatments resulted in augmented mCherry fluorescence in MGA KOs compared with scrambled control (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Consistent with higher CHOP expression and similar to L3MBTL2 KOs, MGA KO cells were more susceptible to either As- or Tg-induced apoptosis (∼1.5- and ∼1.25-folds, respectively) compared with similarly treated scrambled control (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 D and E). Together our data collectively suggest that the two interacting PRC.1 components (L3MBTL2 and MGA) play a role in protecting cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis.

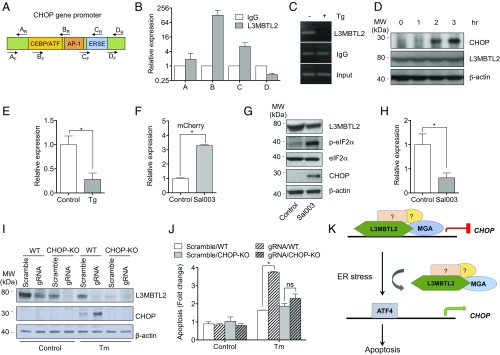

L3MBTL2 Associates with CHOP Promoter to Repress Its Transcription and This Association Is Abrogated by ER Stress.

As part of the PRC.1 complex, L3MBTL2 possesses transcriptional repressive activity and is associated with repressive chromatin structure (37, 38). As our collective results suggest that L3MBTL2 suppresses ER stress-induced apoptosis by repressing CHOP, we hypothesized that L3MBTL2 associates with the promoter region of CHOP to inhibit its up-regulation. We also hypothesized that such association, if any, would be diminished in the presence of ER stress. To test this hypothesis, we pulled down the L3MBTL2 protein and the associated chromatin from cells using the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) technique. We then performed qRT-PCR using primers spanning several regions of the CHOP gene promoter (Fig. 3A) to determine L3MTBL2 association. We found that under basal, unstressed conditions, L3MBTL2 coimmunoprecipitates mostly with the CHOP promoter sequences (region B) that harbor known binding sites for CEBP and ATF transcriptional activators, and to some extent also the region with putative AP-1 binding site (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

L3MBTL2 associates with the CHOP promoter to repress its induction. (A) Schematic drawing of the CHOP promoter. Primer pairs covering different regions of the promoter are indicated. (B) ChIP analysis showing binding of L3MBTL2 to the CHOP promoter region. After chromatin extraction, L3MBTL2 was pulled down and PCR using primers targeting different regions of the CHOP promoter was performed. (C) Representative gel image of ChIP analysis after 8 h post-Tg treatment (100 nM) HEK293T cells were treated with either 100 nM Tg or DMSO 8 h and harvested for ChIP analysis. Primers spanning the promoter region where L3MBTL2 associates the strongest as determined in B were used for PCR. (D) Time course of induction of CHOP protein after Tg (100 nM) treatment as assessed by Western blotting. (E) ChIP analysis in the presence of Tg at 1 h post-Tg treatment. Data represent a representative experiment. Erros bars = SEM (n = 2–3), *P < 0.05. (F) CHOP-mCherry fluorescence in the presence of 10 μM Sal003 or vehicle control as assessed by flow cytometry. *P < 0.05. (G) Western blot analysis showing up-regulation of CHOP in the presence of 10 μM Sal003. (H) ChIP analysis showing reduced association of L3MBTL2 on the CHOP promoter in 20 μM Sal003-treated cells compared with vehicle control. Data represent a representative experiment, Error bars = SEM (n = 2–3), *P < 0.05. (I) Western blot analysis of the expression of CHOP in L3MBTL2 KO or scrambled control in CHOP KO or CHOP WT MEF cells treated with Tm (100 ng/mL, 12 h). (J) Relative apoptosis in L3MTBL2 KO versus scrambled control cells after treatment with Tm (100 ng/mL, 20 h). APC-annexin V/DAPI staining was used to detect apoptosis. *P < 0.05. (K) Proposed model of L3MBTL2-mediated CHOP suppression. In normal conditions, L3MBTL2, together with MGA and other polycomb groups of proteins, occupies the promoter region of the CHOP gene to suppress the latter’s transcription. In the presence of ER stress, the transcription factors (e.g., ATF4) bind to the CHOP promoter region, displacing L3MBTL2 and the polycomb complex, resulting in increased transcription of the CHOP gene.

We next examined whether the association of L3MBTL2 with the CHOP promoter is modulated by ER stress. We treated cells with Tg for 8 h and assessed the binding of L3MBTL2 with the CHOP promoter using ChIP analysis. As shown in Fig. 3C, Tg treatment resulted in diminished L3MBTL2 occupancy. We next tested whether such dissociation happens before CHOP up-regulation. Tg did not affect the levels of L3MBTL2 but induced the expression of CHOP starting at 2 h posttreatment (Fig. 3D). We reasoned that ER stress would lead to dissociation of L3MBTL2 from the CHOP promoter before Tg-induced CHOP protein expression. We thus performed ChIP at 1 h post-Tg treatment. As shown in Fig. 3E the association of L3MBTL2 with the CHOP promoter was greatly diminished before Tg-induced CHOP induction, suggesting that L3MBTL2 may contribute to ER stress-mediated apoptosis via transcriptional repression of CHOP. We also used Sal003, a selective chemical blocker of eIF2α dephosphorylation that causes CHOP up-regulation, to investigate L3MBTL2-mediated transcriptional repression of CHOP. As shown in Fig. 3 F and G, Sal003 treatment increased both CHOP-mCherry fluorescence (Fig. 3F) and endogenous CHOP expression (Fig. 3G). Moreover, treatment with Sal003 led to diminished L3MBTL2 association on CHOP promoter as shown by our ChIP analysis (Fig. 3H).

L3MBTL2 Mitigates ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis by Repressing CHOP.

As our CRISPR screen utilized an ER stress cell model that is based on CHOP up-regulation and as L3MBTL2 suppresses CHOP expression, we next examined whether L3MBTL2 mitigates ER stress-induced apoptosis via CHOP. To this end, we used an existing mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell line that lacks CHOP (CHOP-KO) (39) as well as the corresponding wild-type (WT) MEFs. We established L3MBTL2 CRISPR KO as well as L3MBTL2-overexpressing MEFs and characterized their responses to ER stress. We hypothesized that L3MBTL2 inactivation or overexpression would cause augmentation of or confer protection to ER stress-induced apoptosis in WT cells but would not alter the response in CHOP-KO cells. As shown in Fig. 3I, knockout of L3MBTL2 in WT MEF cells led to greater CHOP expression as well as augmented apoptosis (approximately two-fold) in the presence of ER stress compared with control. These data confirmed the results of our aforementioned experiments that were conducted on the ER stress cell model (Fig. 2) in yet another cell line. However, no difference in apoptosis was observed in scrambled control and L3MBTL2 knockout in CHOP-KO MEFs in the presence of ER stress (Fig. 3J). This result indicates that L3MBTL2’s role in attenuating apoptosis is mediated through CHOP.

Conversely, L3MBTL2 overexpression diminished CHOP expression and mitigated apoptosis (∼1.75-fold) in Tm-treated WT MEFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). On the other hand, no difference in apoptosis was again observed between control and L3MBTL2-overexpessing MEF cells in CHOP KO background after Tm treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). Taken together, the results of our experiments on L3MBTL2 KO and L3MBTL2-overexpressing MEF cells in CHOP−/− background imply that L3MBTL2 suppresses ER stress-induced apoptosis by repressing the induction of CHOP. Taken together, our results support a model in which L3MBTL2, likely in a complex with MGA and other PRC.1 proteins, associates with the CHOP promoter to repress CHOP expression in healthy, unstressed cells. This association is abrogated in the presence of ER stress to allow CHOP expression and eventually lead to apoptosis (Fig. 3K).

MiR-124-3 Inhibits CHOP Expression and ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis.

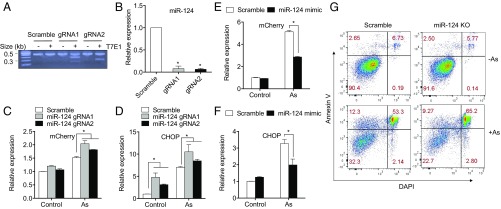

In addition to protein-coding hits, our CRISPR screen also identified multiple microRNAs as potential ER stress suppressors (Fig. 1D and Dataset S2). To validate the top microRNA hits, we generated CRISPR-mediated knockouts of individual microRNAs (two gRNAs each) in the CHOP-mCherry reporter cells, which were then exposed to As and measured for mCherry expression by flow cytometry. Among the top microRNAs identified, miR-370 and miR-124-3 knockouts showed consistent increase in mCherry fluorescence after As exposure (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Because the extent of increase in mCherry expression was highest for miR-124-3 gRNAs (SI Appendix, Fig. S8I), we focused on miR-124-3 for further characterization.

Both gRNAs targeting miR-124-3 induced efficient gene editing in the CHOP-mCherry reporter cells as shown by the T7E1 cleavage assay (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this, qRT-PCR showed that miR-124-3 expression was suppressed by more than 90% by miR-124-3 gRNAs compared with the scrambled control (Fig. 4B). MiR-124-3 KO cells had higher CHOP-mCherry fluorescence as well as endogenous CHOP expression than control cells in response to As (Fig. 4 C and D). Conversely, overexpression of miR-124-3 by mimic transfection resulted in decreased ER stress-induced CHOP-mCherry fluorescence (Fig. 4E) and decreased endogenous CHOP expression (Fig. 4F). Similarly, miR-124-3 knockout increased Tg-induced CHOP expression and the basal CHOP expression compared with scramble control, whereas overexpression of miR-124 down-regulated Tg-induced CHOP expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Consistent with the effect on CHOP expression, miR-124-3 knockout cells exhibited increased apoptosis in response to As (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

MiR-124-3 inhibits ER stress-induced CHOP expression and its knockout augments ER stress-induced apoptosis. (A) DNA cleavage indicating mismatch and mutation induced by the two gRNAs targeting miR-124-3 was validated by T7E1 assay. (B) Suppression of miR-124-3 expression by two gRNAs was validated by qRT-PCR. (C and D) Knockout of miR-124-3 increases As (5 μM)-induced CHOP-mCherry fluorescence and endogenous CHOP expression compared with scrambled control as measured by flow cytometry. (E and F) Transfection of miR-124-3 mimic to CHOP-mCherry reporter cells suppresses As (5 μM)-induced CHOP-mCherry fluorescence and endogenous CHOP expression compared with scrambled control as measured by flow cytometry. (G) MiR-124-3 KO cells (by gRNA1) showed augmented apoptotic cells compared scrambled control in the presence of As, as measured by Annexin V staining and subsequent flow cytometry. Scrambled control and miR -124 KO were treated with 50 μM As or water for 24 h and harvested for Annexin V/DAPI staining analysis to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells. Annexin V positive.cells, which are shown in the Upper quadrant of each graph, make up the apoptotic populations. n = 3 experiments. Triplicates were done for each condition. *P < 0.05.

MiR-124-3 Inhibits ER Stress by Directly Targeting IRE1.

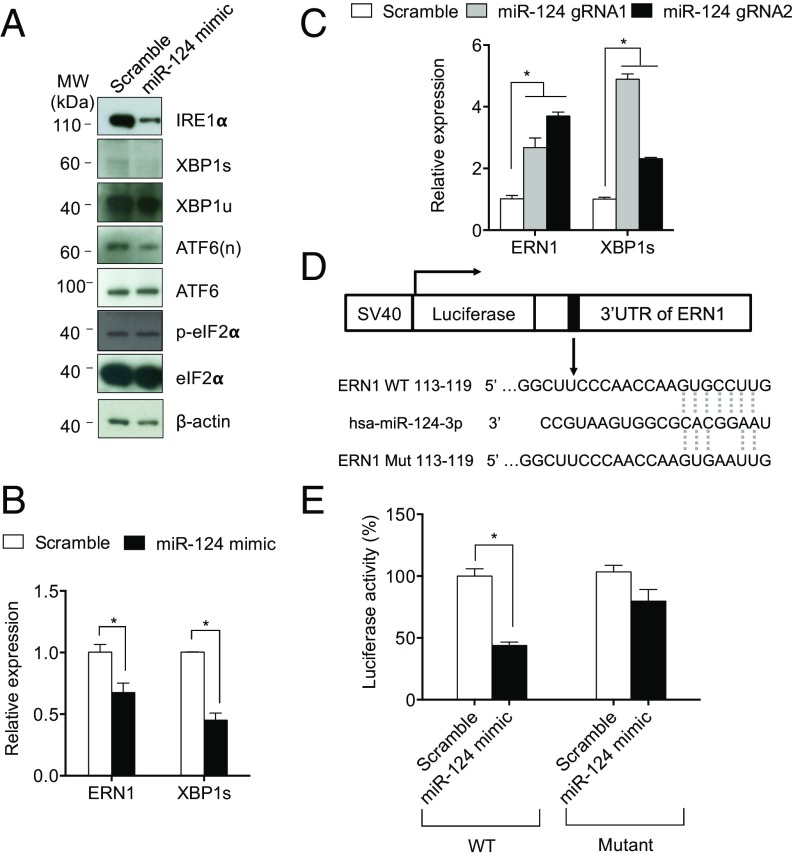

To investigate the mechanism underlying CHOP suppression by miR-124-3, we assessed the effect of miR-124-3 on the three branches of the ER stress pathway (IRE1α, ATF6, and PERK). XBP1s, ATF6(n), and ATF4 all can bind to the CHOP promoter to increase its expression (16). Therefore, we examined the expression of XBP1, ATF6, and eIF2α, and their corresponding active forms: spliced XBP1 (XBP1s), ATF6(n), and phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α). As shown in Fig. 5A, miR-124-3 mimic significantly down-regulated IRE1α protein expression. In addition, miR-124-3 mimic decreased the expression of the spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) at basal conditions while miR-124-3 mimic did not seem to affect the expression of the unspliced form of XBP1 (XBP1u) (Fig. 5A). MiR-124-3 mimic also down-regulated the expression of ATF6(n) (Fig. 5A). Expression of ATF6, p-eIF2α, and eIF2α was not affected by miR-124-3 mimic transfection (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the Western blot result, miR-124-3 mimic significantly decreased the level of ERN1 (the gene encoding IRE1) and XBP1s transcript (Fig. 5B). Conversely, miRNA-124-3 KO cells have greater ERN1 and XBP1s expression (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

MiR-124-3 directly targets IRE1. (A) MiR-124-3 mimic suppresses As-stimulated IRE1α and XBP1s expression. HEK293T cells were transfected with scramble or miR-124-3 mimic, then exposed to As (5 μM) for 24 h. (B) MiR-124-3 mimic suppresses mRNA expression of ERN1 (the gene encoding IRE1) and XBP1s. (C) MiR-124-3 KOs increase ERN1 and XBP1s mRNA expression. (D) Sequences of wild-type or mutant 3′-UTR of ERN1 in the downstream of the firefly luciferase gene. (E) MiR-124-3 binds to 3′-UTR of ERN1, the gene encoding IRE1. HEK293T cells were transfected with pMirTarget ERN3′-UTR or pMirTarget ERN3′-UTR mutant in the presence of scramble or miR-124-3 mimic. n = 3 experiments. Triplicates were done for each condition. *P < 0.05.

Although miR-124-3 mimic may down-regulate the ATF6 pathway, we focused on the IRE1 pathway for further validation because TargetScan predicts that ERN1 has a potential miR-124-3 targeting site in its 3′-untranslated region (UTR). To test whether miR-124-3 suppresses IRE1 expression by directly targeting the 3′-UTR of ERN1, we fused either the wild type or a mutant form (in which we changed two nucleotides in the putative miR-124-3 targeting sequence through site-directed mutagenesis) of the ERN1 3′-UTR to the luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 5D). We then cotransfected the luciferase constructs (wild type or mutant) with either miR-124-3 or control mimics (scramble) into HEK293T cells and measured the luciferase activity. As shown in Fig. 5E, miR-124-3 mimic reduced the luciferase activity of the wild-type 3′-UTR construct by over 50%. However, such repression by miR-124-3 mimics was largely abolished for the mutant construct that contains the altered miR-124-3 binding site, indicating that the site in the ERN1 3′-UTR is required for the inhibitory effect of miR-124-3. Together, these data showed that miR-124-3 directly targets the 3′-UTR of ERN1 (IRE1) to inhibit its expression.

Discussion

The ER stress response is aimed at restoring protein homeostasis and promoting cell survival but in excessive ER stress conditions, can lead to cell death. While the ER stress pathways are well characterized, much less is known about how cells suppress the ER stress response to avoid apoptosis and help restore homeostasis. Using a CRISPR-based loss-of-function genetic screen, we identified multiple suppressors of the ER stress response that protect cells from apoptosis by targeting key players at multiple steps of the UPR. These include members of polycomb-group proteins that directly inhibit the expression of the transcriptional factor central to ER stress-induced cell death and a microRNA that targets IRE1, a canonical ER stress pathway component. Our study reveals regulatory mechanisms that ameliorate potentially damaging stress response and provides insights into pathologies linked to excessive ER stress and apoptosis.

The expression of transcription factors mediating cell death such as CHOP is tightly regulated and maintained at basal levels to prevent unwanted cell death (16, 40–42). Our results suggest that L3MBTL2, possibly in a complex with MGA, binds to the CHOP promoter to repress CHOP expression in healthy, unstressed cells. In the presence of ER stress, L3MBTL2 association with the CHOP promoter region is diminished. This potentially allows known transcriptional activators of CHOP (e.g., ATF4) to bind to the promoter, in turn tipping the balance in favor of CHOP up-regulation (Fig. 3K). The precise mechanism for the reduced L3MBTL2 occupancy at the CHOP promoter during ER stress, however, remains to be determined. One possibility is that transcriptional activators compete with and displace L3MBTL2 from the CHOP promoter under ER stress conditions as indicated by the results of our ChIP experiments. It has been reported that L3MBTL2 sumoylation facilitates repression of its target genes (43). Conceivably, L3MBTL2 sumoylation may be regulated by ER stress to allow for CHOP induction. Finally, as L3MBTL2 and MGA can exist in a complex and colocalize in target loci (44), their interaction may be disrupted by ER stress to relieve CHOP suppression.

Our study also identifies a microRNA (miR-124-3) as a suppressor of the IRE1 branch of the ER stress pathway. MicroRNAs have emerged as key regulators of ER homeostasis, stress response, and UPR signaling (45, 46). For example, overexpression of the miR-23a, -27a, and 24-2 cluster and miR-122 has led to induction of CHOP, ATF4, and subsequent cell death (47, 48). In addition, IRE1 mediates the induction of miR-346 while degrading premiRs-17, -34a, -96, and -125b (49–51). MiR-1291 has been shown to bind to 3′-UTR of ERN1 gene, resulting in reduced IRE1 expression in hepatoma cells (52). Although miR-1291 reduced XBP1 splicing, it failed to attenuate Tm-induced CHOP activation. Our study showed that miR-124-3 suppresses the IRE1 signaling pathway by direct binding to the sequence in the 3′-UTR of the ERN1 gene, leading to decreased XBP1 splicing and CHOP activation in As- or Tg-treated cells. Furthermore, miR-124-3 KO leads to increased activation of IRE1 signaling with increased XBP1 splicing, augmented CHOP activation, and increased apoptotic cell death. Our study demonstrates that miR-124-3 protects against ER stress-mediated cell death by attenuating CHOP activation potentially through inhibiting the IRE1/XBP1 pathway. Although the IRE1/XBP1 UPR branch may regulate the induction of CHOP (16), PERK is known to be dominant in the activation of CHOP (6, 53). In addition, activation of IRE1/XBP1 signaling mainly activates proadaptive pathways such as up-regulation of target genes for ER chaperones and ER-associated degradation components (54). Moreover, miR-124-3 has been predicted to target more than 1,800 genes based on TargetScan database, suggesting that there are likely other mechanisms by which miR-124-3 suppresses the ER stress response.

The present study is a genome-wide CRISPR-based knockout screen specifically aimed at identifying suppressors of the ER stress response in mammalian cells. We used a reporter cell line that was specifically designed to identify regulators of CHOP, allowing us to infer that the identified genes also suppress ER stress-induced cell death. However, because our screen did not include a control arm in which the effect of gene deletion itself (without any chemical stressor) could have been observed on the reporter, it is difficult to know for the full screen (outside of the validated and characterized hits) which gene hits affect ER homeostasis vs. arsenic-induced stress. Further studies are needed to determine whether hits other than L3MBTL2, MGA, or miR-124 suppress basal ER stress response in untreated cells to maintain ER homeostasis. A recent study using a CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screen identified genes whose repression perturbs ER homeostasis and revealed how the three branches of the ER stress pathway monitor distinct types of stress (55). We have found some overlaps in the present screen with that of the CRISPRi screen. For example, the CRISPRi screen identified UFM1, a uniquitin-like protein involved in proper maintenance of ER homeostasis, while our present study uncovered UFSP1, a protease that has been reported to activate UFM1. Each screen has also identified a member of the HSP-40 chaperone family—DNAJ19 (CRISPRi screen) or DNAJC15 (present study). These genes may play roles in suppressing ER stress response through their chaperone activities (56). Furthermore, some of the other hits identified by our screen have known roles in protecting cells from protein aggregation. For example, HSPB9 is a member of the heat-shock protein family possessing chaperone activity (57) while UBE3C and UBE2B are enhancers of proteasome activity that is essential in eliminating aggregated proteins (58, 59) (Dataset S1). While these proteins may not act directly on any of the ER stress pathways or on CHOP itself, their absence could result in accumulation of misfolded proteins and ER stress.

The ER stress response is an elaborate cellular response with potent cell damaging consequences; it is not surprising that the results of our screen reveal many potential ER stress suppressors. Our screen has also identified genes, other than L3MBTL2 and MGA, that likewise have known DNA-binding and transcriptional repression activities (Dataset S1). These genes, which include E2F6, OMG, SCA1, MPHOSPH8, L3MBTL3, and others, may be the subject of follow-up studies to characterize which step(s) of the ER stress response pathways they act on or whether they also interact with canonical members of the PRC.1. This would allow mapping of the suppressors of the UPR and would increase our understanding of this important cellular response. In addition to the aforementioned genes, interestingly, some of the top hits from our screen include genes with known roles in the nervous system but have not been largely explored in the context of ER stress. These include OMG, KCNJ14, NTS, and SEMA6D. OMG (oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein) contributes to myelination in the nervous system (60), KCNJ14 (Potassium Voltage-Gated Channel Subfamily J Member 14) is believed to influence the excitability of motor neurons (61), NTS (Neurotensin) is a secreted tridecapeptide that may function as a neuromodulator or a neurotransmitter (62), and SEMA6D (Semaphorin 6D) is highly expressed in the brain and is believed to play a role in axon guidance (63). As many neurological diseases exhibit heightened ER stress, the potential roles of these genes in protecting the nervous system from ER stress-mediated apoptosis is an attractive area for future studies. Furthermore, as miR-124-3 is also highly abundant in the nervous system and is dysregulated in many neurological disorders (64), whether these hits act independently of or cooperate with miR-124-3 to prevent the development of ER stress-related neurological disorders is an important aspect of future studies.

Dysregulated ER stress response contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and neurological disorders. A primary mechanism of the pathogenesis of many ER stress-related diseases is CHOP-mediated cell death (15, 16, 65, 66). Our findings suggest that CHOP elevation in ER stress-related diseases could result from the loss of transcriptional repressive activity by the PRC.1 on CHOP. Conceivably, changes in the expression of members of PRC.1 caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms may contribute to the molecular mechanisms of ER stress-related diseases in susceptible populations by favoring CHOP up-regulation and sensitizing cells to ER stress-induced apoptosis. Indeed, studies have linked L3MBTL2 gene variants with neuroticism (67) and schizophrenia (68), neurological disorders believed to be associated with heightened ER stress. In addition, miR-124-3 is highly expressed in the brain and is believed to play a role in many neurodegenerative diseases (64). Genetic variants on the PRC.1 or miR-124-3 genes may provide a potential mechanistic link between ER stress-induced cell death and neurological disorders.

In summary, we uncovered multiple suppressors of ER stress-induced apoptosis using a CRISPR-based loss-of-function genetic screen. These suppressors include members of a polycomb protein complex that inhibit the expression of the transcriptional factor central to ER stress-induced cell death, and a microRNA that targets IRE1, a canonical ER stress pathway component. Further characterization of these genes as well as additional hits identified by our screen will advance our understanding of the ER stress response and provide potential therapeutic targets for pathologies whose etiology is linked to overactive ER stress response and apoptosis.

Methods

Cell Culture and Chemicals.

HEK293T cells and MEFs were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin; Life Technologies). The mCherry reporter cell line driven by the CHOP promoter was established as described previously (22). Sodium arsenite, thapsigargin, tunicamycin, etoposide, and 5-fluorouracil were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Establishment of Lentiviral CRISPR Knockout Library in CHOP-mCherry Reporter Cells.

The CRISPR knockout library containing ∼120,000 gRNAs individually cloned into lentiCRISPRv2 vector was obtained from Addgene. The library contains six distinct gRNAs targeting each protein-coding gene and four distinct gRNAs for each of the miRNAs (23). After amplification of the library DNA, lentiviruses were produced in HEK293T cells using the packaging plasmids pVSVg and psPAX2 (Addgene) (69). The resulting lentiviral library was used to transduce the CHOP-mCherry reporter cells at a relatively low MOI of 0.3 and in the presence of polybrene (8 µg/mL) for 24 h. Cells with stable viral integration were selected for 7 d using puromycin at 1 µg/mL. The cells were allowed to grow in fresh media for an additional 9 d to expand the library.

FACS-Based Screen.

The reporter cells containing the CRISPR library were treated with 5 µM sodium arsenite for 15 h and then subjected to FACS using the BD FACSAria Sorter (BD Biosciences). The upper 10% (fluorescence intensity) of the mCherry-positive cell population was isolated, recovered, and allowed to repopulate for 4 d. The sorted reporter cells were treated again with 5 µM As and the upper 10% of the bright population was isolated. The genomic region containing the CRISPR guides was PCR-amplified and then subcloned into the lentiCRISPRv2 plasmid to generate a sublibrary. For PCR amplification the following conditions were used: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 4 min, 98 °C for 20 s, 30 cycles at 60 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. The primers used were “forward: 5′-AACGGATCGGCACTGCGTGC and reverse: 5′- TGTGGGCGATGTGCGCTCTG.” For subcloning, the PCR products and lentiCRISPRv2 plasmid were digested using EcoR1 and KpnI (New England Biolabs) restriction enzymes and transformed into XL10-Gold Ultracompetent Cells (Agilent Technologies). Lentiviruses made from the sublibrary were then used to transduce into CHOP-mCherry reporter cells, which were subjected to a new round of As treatment and sorting. In the final round of FACS, the upper 50% of mCherry-positive As-treated population was isolated for deep sequencing and identification of target genes.

Deep Sequencing and Data Analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the final sorted cell population and used for PCR to amplify the CRIPSR guides as previously described (23). Deep sequencing was perfomed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument in Rapid Run mode (150-bp paired end) at the Bauer Core Facility at Harvard University. Sample raw reads were demultiplexed using the fastq-multx function of the ea-utils package (v1.1.2) (70). Because some barcodes were not 5′ anchored, we recursively demultiplexed reads after trimming one base pair from the 5′ end until the entire gRNA sequence could not be captured (i.e., allowing for 20 bp to remain). Primer sequences from 5′ (TCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACCG) and 3′ (GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGTTAAAATAAGGCTAGTCCGTTATCAACTTGAAAAAGTGGCACCGAGTCGGTGCTTTTTTGAATTCGCTAGC) ends were trimmed from reads using cutadapt v1.9 while allowing for overhang. Next, reads were aligned to the Human GeCKOv2 library available at Addgene (http://www.addgene.org/crispr/libraries/geckov2/) using Bowtie 2 v2.1.0 while allowing for a single base mismatch (71). The total number of reads mapping to each gRNA guide was obtained with the samtools (v0.1.19) idxstats function (72), and raw gRNA counts were normalized to the total number of mapped reads for each sample in R. Per-gene results were obtained by taking the mean of normalized gRNA counts corresponding to each gene. Gene-level results were ranked by the fold change of the mean for both sorted population samples to the control sample. The number of gRNAs per gene with fold change greater than two was also recorded.

Pathway Analysis.

DAVID was used to perform gene functional annotation clustering using default options and annotation categories (Disease: OMIM_DISEASE; Functional Categories: COG_ONTOLOGY, SP_PIR_KEYWORDS, UP_SEQ_FEATURE; Gene_Ontology: GOTERM_BP_FAT, GOTERM_CC_FAT, GOTERM_MF_FAT; Pathway: BBID, BIOCARTA, KEGG_PATHWAY; and Protein_Domains: INTERPRO, PIR_SUPERFAMILY, SMART) (73). Genes predicted to be targets of top miRNAs (fold-change >10) were obtained from TargetScan (74) and used for the enrichment analysis corresponding to the miRNA CRISPR screen.

Generation of Individual CRISPR Knockout Cells.

To validate top hits from the screen, CRISPR knockout cells for individual genes or miRNAs were generated using specific guides (top two different guides for each gene or miRNA) from the pooled library list. Guides were cloned into lentiCRISPRv2 vector containing hSpCas9 cassette (Addgene) as previously described (69). In brief, oligonucleotides targeting the site sequence were synthesized with 3 bp NGG PAM sequence flanking the 3′ end, annealed, and cloned into the BsmBI-digested lentiCRISPRv2 vector. The resulting plasmids were transformed into Stbl3 bacteria (Life Technologies) and purified using Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Lentiviruses were produced by cotransfecting the lentiCRISPRv2 containing gRNAs with the packaging plasmids pVSVg and psPAX2 (Addgene) in HEK293T cells. Lentiviral transduction in CHOP-mCherry cells was performed in the presence of polybrene (8 µg/μL) for 24 h. Selection was performed using puromycin (Life Technologies) in a similar manner as described in the CRISPR knockout viral library transduction. The T7E1 assay was performed to determine knockout efficiency. For the T7E1 assay, the genomic region harboring the target of gRNAs was first PCR-amplified and subjected to denaturing and reannealing temperatures (95 °C for 2 min, ramp down at −2 °C/s to 85 °C, ramp down at −0.1 °C/s to 25 °C, and stopped at 16 °C). The T7E1 (New England Biolabs) cleavage reaction was then performed at 37 °C for 20 min. The PCR products were visualized using 1.5% agarose gel. The gRNA sequences are tabulated in SI Appendix, Table S3.

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted using RNEasy Kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using Oligo-dT and SuperScript II Kit (Life Technologies). For miRNAs, total RNA was extracted using miRNEasy Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription and PCR were performed using miScript PCR Starter Kit (Qiagen). qPCR was performed using SYBR green (Qiagen) using specific primers for each gene or miRNA. The [delta][delta]Ct method was used to compare relative amounts of transcripts between different genes. β-Actin was used as internal control. RNU6B (RNU6-2) was used as internal control for miRNAs.

Flow Cytometry Assay.

Following experimental treatments, cells were harvested at indicated timepoints and resuspended in 300 µL regular medium. Flow cytometry was performed using DXP11 analyzer (Cytek) on 20,000 events and the mean of the fluorescence on the YeFL2 channel corresponding to mCherry fluorescence was determined using FlowJo software.

Western Blotting.

Western blotting was performed as previously described (22) using the following antibodies: anti-CHOP (mouse mAb, 2895), anti-IRE1α (rabbit mAb, 3294), anti-XBP1s (rabbit mAb, 12782), anti-eIF1α (rabbit mAb, 5324), and anti-phosphorylated-eIF2α (rabbit mAb, 3398) from Cell Signaling; anti-ATF6 (rabbit pAb, TA306287) from Origene; anti-L3MBTL2 (rabbit pAb, 39569) was from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA); and anti–β-actin (mouse mAb, sc-8432) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). All antibodies were diluted 1:1,000-fold (exception: β-actin, 1:3,000). For immunoblot quantitation, chemiluminescence was captured with an Alpha Innotech Fluorchem Imager and analyzed with AlphaEaseFC software.

Annexin V and DAPI Staining.

The annexin V/DAPI staining was used to determine cell death posttreatment according to manufacturer’s protocol with slight modification (Biolegend). Staining with annexin V (4.5 ng/µL) conjugated to either FITC or APC and DAPI (2 µg/mL) was performed in annexin V binding buffer at a concentration of 0.25–1.0 × 107 cells/mL. Flow cytometry was performed using the DXP11 Analyzer (Cytek) on 20,000 events and analyzed using FlowJo software.

ChIP.

ChIP using anti-L3MBTL2 antibody (PA5-28549, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed using the ChIP-It Express Enzymatic Kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to determine enrichment of CHOP promoter regions after immunoprecipitation with the L3MBTL2 antibody. The percentage input method was used to determine relative expression.

MiR-124-3 Mimic Transfection.

HEK293T cells plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates were transfected with scramble control (AllStars Negative Control siRNA, Qiagen) or miR-124-3 mimic (Syn-hsa-mir-124-3p, Qiagen; 5 pmol/well) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After incubation for 4 h, the medium was replaced for fresh medium, and cells were incubated for an additional 20 h. Cells were then exposed to As for 6 h (for qRT-PCR) or 24 h (for Western blot analysis). Total RNAs or cell lysates were collected for qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively.

Cloning of 3′-UTR of ERN1 and Luciferase Assay.

The 3′-UTR of ERN1 was PCR-amplified using primers with EcoRI or NotI sites (forward primer: 5′-ATATATGAATTCGCGAGGGCGGCCCCTCTGTTC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TGCTTA GCGGCCGCAGCCTCTTGTTCCACCGGCCT-3′) and cloned into the pMirTarget vector (Origene). The cloning was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion (EcoRI and NotI) and direct DNA sequencing. Site mutagenesis on the sequence of 3′-UTR of ERN1 was performed using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocol (forward primer: 5′-CAGAGCAGGCAGCTCAATTCACTTGGTTTGGGAAGC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GCTTCCCAAACCAAGTGAATTGAGCTGCCTGCTCTG-3′).

HEK293T cells were transfected with pMirTarget ERN1 3′-UTR or pMirTarget ERN1 3′-UTR mutant in the presence of scramble or miR-124–3 mimic using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). pRL CMV control vector (1 ng) was cotransfected as an internal control. After a 4-h incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh medium, and cells were incubated for 20 h. Luciferase activity was quantified using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System following the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity by pMirTarget vector was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prizm version 6 (La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed by Student’s t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. If significant effects were detected, the ANOVA was followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparison of means. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically different. Data were expressed as means ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hanno Hock (Massachusetts General Hospital) for providing us with the plasmids used for establishing MEF overexpressing L3MBTL2 and the corresponding control. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01grants (R01ES02230 and R01ES029097) and in part by a pilot grant from the Harvard National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Center (P30ES000002).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1906275116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schubert U., et al. , Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature 404, 770–774 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson T., et al. , Arsenite interferes with protein folding and triggers formation of protein aggregates in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 125, 5073–5083 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramadan D., Rancy P. C., Nagarkar R. P., Schneider J. P., Thorpe C., Arsenic(III) species inhibit oxidative protein folding in vitro. Biochemistry 48, 424–432 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquardt T., Helenius A., Misfolding and aggregation of newly synthesized proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 117, 505–513 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakes S. A., Papa F. R., The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 10, 173–194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I., Ron D., Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 184–190 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ron D., Walter P., Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding H. P., Zhang Y., Ron D., Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397, 271–274 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida H., Matsui T., Yamamoto A., Okada T., Mori K., XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 107, 881–891 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calfon M., et al. , IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415, 92–96 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K., Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3787–3799 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogata M., et al. , Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 9220–9231 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avivar-Valderas A., et al. , PERK integrates autophagy and oxidative stress responses to promote survival during extracellular matrix detachment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 3616–3629 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrika B. B., et al. , Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy provides cytoprotection from chemical hypoxia and oxidant injury and ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One 10, e0140025 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sano R., Reed J. C., ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 3460–3470 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyadomari S., Mori M., Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 11, 381–389 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim I., Xu W., Reed J. C., Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: Disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 1013–1030 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCullough K. D., Martindale J. L., Klotz L. O., Aw T. Y., Holbrook N. J., Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1249–1259 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puthalakath H., et al. , ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell 129, 1337–1349 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galehdar Z., et al. , Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J. Neurosci. 30, 16938–16948 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momoi T., Caspases involved in ER stress-mediated cell death. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 28, 101–105 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh R. S., et al. , Functional RNA interference (RNAi) screen identifies system A neutral amino acid transporter 2 (SNAT2) as a mediator of arsenic-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 6025–6034 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shalem O., et al. , Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C., et al. , Unfolded protein response signaling and MAP kinase pathways underlie pathogenesis of arsenic-induced cutaneous inflammation. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 4, 2101–2109 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolt A. M., Zhao F., Pacheco S., Klimecki W. T., Arsenite-induced autophagy is associated with proteotoxicity in human lymphoblastoid cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 264, 255–261 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argos M., et al. , Arsenic exposure from drinking water, and all-cause and chronic-disease mortalities in Bangladesh (HEALS): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 376, 252–258 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu M. M., Kuo T. L., Hwang Y. H., Chen C. J., Dose-response relation between arsenic concentration in well water and mortality from cancers and vascular diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 130, 1123–1132 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donohue S. J., Roseboom P. H., Illnerova H., Weller J. L., Klein D. C., Human hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase: Presence of LINE-1 fragment in a cDNA clone and pineal mRNA. DNA Cell Biol. 12, 715–727 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Y., et al. , Identification and comparative functional characterization of a new human riboflavin transporter hRFT3 expressed in the brain. J. Nutr. 140, 1220–1226 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He L., Vasiliou K., Nebert D. W., Analysis and update of the human solute carrier (SLC) gene superfamily. Hum. Genomics 3, 195–206 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin J., et al. , The polycomb group protein L3mbtl2 assembles an atypical PRC1-family complex that is essential in pluripotent stem cells and early development. Cell Stem Cell 11, 319–332 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manthey K. C., Chew Y. C., Zempleni J., Riboflavin deficiency impairs oxidative folding and secretion of apolipoprotein B-100 in HepG2 cells, triggering stress response systems. J. Nutr. 135, 978–982 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manthey K. C., Rodriguez-Melendez R., Hoi J. T., Zempleni J., Riboflavin deficiency causes protein and DNA damage in HepG2 cells, triggering arrest in G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Nutr. Biochem. 17, 250–256 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vermes I., Haanen C., Steffens-Nakken H., Reutelingsperger C., A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods 184, 39–51 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Der S. D., Yang Y. L., Weissmann C., Williams B. R., A double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway mediating stress-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 3279–3283 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morey L., Helin K., Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 323–332 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trojer P., et al. , L3MBTL2 protein acts in concert with PcG protein-mediated monoubiquitination of H2A to establish a repressive chromatin structure. Mol. Cell 42, 438–450 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo J. Y., et al. , Histone deacetylase 3 is selectively involved in L3MBTL2-mediated transcriptional repression. FEBS Lett. 584, 2225–2230 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinszner H., et al. , CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12, 982–995 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calkhoven C. F., Ab G., Multiple steps in the regulation of transcription-factor level and activity. Biochem. J. 317, 329–342 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada T., Yoshida H., Akazawa R., Negishi M., Mori K., Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem. J. 366, 585–594 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ron D., Habener J. F., CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 6, 439–453 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stielow C., et al. , SUMOylation of the polycomb group protein L3MBTL2 facilitates repression of its target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3044–3058 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stielow B., Finkernagel F., Stiewe T., Nist A., Suske G., MGA, L3MBTL2 and E2F6 determine genomic binding of the non-canonical Polycomb repressive complex PRC1.6. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007193 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Logue S. E., Cleary P., Saveljeva S., Samali A., New directions in ER stress-induced cell death. Apoptosis 18, 537–546 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maurel M., Chevet E., Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling: The microRNA connection. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C1117–C1126 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang F., et al. , Modulation of the unfolded protein response is the core of microRNA-122-involved sensitivity to chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia 13, 590–600 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chhabra R., Dubey R., Saini N., Gene expression profiling indicate role of ER stress in miR-23a∼27a∼24-2 cluster induced apoptosis in HEK293T cells. RNA Biol. 8, 648–664 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartoszewski R., et al. , The unfolded protein response (UPR)-activated transcription factor X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces microRNA-346 expression that targets the human antigen peptide transporter 1 (TAP1) mRNA and governs immune regulatory genes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41862–41870 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lerner A. G., et al. , IRE1α induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 16, 250–264 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Upton J. P., et al. , IRE1α cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science 338, 818–822 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maurel M., Dejeans N., Taouji S., Chevet E., Grosset C. F., MicroRNA-1291-mediated silencing of IRE1α enhances Glypican-3 expression. RNA 19, 778–788 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu C., Bailly-Maitre B., Reed J. C., Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Cell life and death decisions. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2656–2664 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fonseca S. G., Gromada J., Urano F., Endoplasmic reticulum stress and pancreatic β-cell death. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 266–274 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adamson B., et al. , A multiplexed single-cell CRISPR screening platform enables systematic dissection of the unfolded protein response. Cell 167, 1867–1882.e21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cherian P. T., et al. , Increased circulation and adipose tissue levels of DNAJC27/RBJ in obesity and type 2-diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 9, 423 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kappé G., et al. , The human genome encodes 10 alpha-crystallin-related small heat shock proteins: HspB1-10. Cell Stress Chaperones 8, 53–61 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chu B. W., et al. , The E3 ubiquitin ligase UBE3C enhances proteasome processivity by ubiquitinating partially proteolyzed substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34575–34587 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Braganza A., et al. , UBE3B is a calmodulin-regulated, mitochondrion-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2470–2484 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vourc’h P., Andres C., Oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp): Evolution, structure and function. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 45, 115–124 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Töpert C., et al. , Kir2.4: A novel K+ inward rectifier channel associated with motoneurons of cranial nerve nuclei. J. Neurosci. 18, 4096–4105 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.St-Gelais F., Jomphe C., Trudeau L. E., The role of neurotensin in central nervous system pathophysiology: What is the evidence? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 31, 229–245 (2006). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu X., et al. , Identification, characterization, and functional study of the two novel human members of the semaphorin gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35574–35585 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun Y., Luo Z. M., Guo X. M., Su D. F., Liu X., An updated role of microRNA-124 in central nervous system disorders: A review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9, 193 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakamura T., et al. , Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase links pathogen sensing with stress and metabolic homeostasis. Cell 140, 338–348 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsukano H., et al. , The endoplasmic reticulum stress-C/EBP homologous protein pathway-mediated apoptosis in macrophages contributes to the instability of atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1925–1932 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lo M. T., et al. , Genome-wide analyses for personality traits identify six genomic loci and show correlations with psychiatric disorders. Nat. Genet. 49, 152–156 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium , Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanjana N. E., Shalem O., Zhang F., Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 11, 783–784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aronesty E., Comparison of sequencing utility programs. Open Bioinf. J. 7, 1–8 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Langmead B., Salzberg S. L., Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li H., et al. ; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup , The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A., Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P., Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.