Significance

Can radiocarbon (14C) dating uncover modern forgeries? Radiocarbon dating has the potential to answer the question of when an artwork was created, by providing a time frame of the material used. In this study we show that with two microsamples (<500 μg), from both the canvas and the paint layer itself, a modern forgery could be identified. The canvas dating is consistent with the purported attribution to the 19th century; however, the 14C age gained on the paint contradicts this as it offers clear evidence for a post-1950 creation. Thus the additional dating of the paint reveals the forger’s scheme where the repainting of an appropriately aged canvas was used to convey the illusion of authenticity.

Keywords: radiocarbon dating, forgery, microsample, organic binder

Abstract

Art forgeries have existed since antiquity, but with the recent rapidly expanding commercialization of art, the approach to art authentication has demanded increasingly sophisticated detection schemes. So far, the most conclusive criterion in the field of counterfeit detection is the scientific proof of material anachronisms. The establishment of the earliest possible date of realization of a painting, called the terminus post quem, is based on the comparison of materials present in an artwork with information on their earliest date of discovery or production. This approach provides relative age information only and thus may fail in proving a forgery. Radiocarbon (14C) dating is an attractive alternative, as it delivers absolute ages with a definite time frame for the materials used. The method, however, is invasive and in its early days required sampling tens of grams of material. With the advent of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) and further development of gas ion sources (GIS), a reduction of sample size down to microgram amounts of carbon became possible, opening the possibility to date individual paint layers in artworks. Here we discuss two microsamples taken from an artwork carrying the date of 1866: a canvas fiber and a paint chip (<200 µg), each delivering a different radiocarbon response. This discrepancy uncovers the specific strategy of the forger: Dating of the organic binder delivers clear evidence of a post-1950 creation on reused canvas. This microscale 14C analysis technique is a powerful method to reveal technically complex forgery cases with hard facts at a minimal sampling impact.

Since its discovery in the 1940s (1), radiocarbon dating has undergone significant development allowing a substantial decrease in the amount of material necessary for 14C analysis. The initial sample requirement in the method’s early days amounted to tens of grams of material. With the advent of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) (2, 3), the amount of carbon necessary for obtaining a radiocarbon date was significantly reduced from a few grams down to 1 milligram carbon (4). Technical advances in general, and especially in the field of gas ion source AMS (5, 6), where mixtures of CO2 and He gas are introduced straight into the GIS-AMS, have reduced sample requirements to micrograms of material (7), thereby setting a new milestone. Through the direct coupling of an elemental analyzer (EA) that converts the sample to CO2 by combustion, samples containing as little as 10 µg carbon can be directly analyzed for their 14C content (8). These ongoing developments (9–11) have revolutionized sample requirements and hold great promise to support the research and understanding of cultural heritage materials, where sampling is critical and sample size is very often limited. The GIS-AMS setup requires only minute amounts of material rendering the 14C analysis microinvasive and henceforth opening the possibility to target paint layers themselves (12). In the case of a painting, the typical supports made of textile, wood, parchment, or paper are sampled, as they usually offer sufficient material and can provide decisive evidence in authentication issues (13, 14). Radiocarbon dating of the canvas gives a time frame of when the raw fiber material was harvested and generally has a few years offset with the actual completion of the work. A time lag of 2–5 y between the radiocarbon date and the date noted on the work of art is not uncommon (15). When the 14C age of the canvas postdates the signed date, it is considered a potential evidence of forgery (13). However, results on the canvas alone may be inconclusive, as canvas may have been reused by the artist himself as an economic measure or intentionally by a forger with the intent to deceive. The infamous Han Van Meegeren (1889–1947), who specialized in forging Vermeer paintings, is known to have scraped the paint off of older paintings to reuse the canvases to yield the illusion of a naturally aged painting substrate (16, 17). Similarly, Wolfgang Beltracchi, a 21st century forger, also bought his frames and supports at antique markets (18). Thus, the art of deceiving by acquiring an older support is a common modus operandi among forgers to avoid anachronistic features and was already common practice before the development of 14C dating. Therefore, identifying counterfeited artworks by relying solely on the dating of the support material is insufficient to ensure authenticity.

A common approach to uncover forgeries involves discrete material analyses (19–21). In cases where no pigment, filler, or binder anachronisms are identified, the judgment of degradation products arising from natural aging is inconclusive, and radiocarbon dating of the support material is indecisive, dating of the binder in the pictorial layer is indispensable. The idea of identifying modern forgeries based on 14C dating of the binder was formulated with the advent of AMS (22), but suffered from practical limitation as the study was conducted on 100-mg scale sample material, an unfeasible sampling quantity for artworks. It is only possible nowadays thanks to technological advances of the 21st century that have made the technique viable for application to microsamples.

The case study presented here is a known forgery created by Robert Trotter (b. 1954–). By his own admission, Trotter conducted 52 sales of his fakes and forgeries from 1981 to 1988 (23). One of those paintings, signed “Sarah Honn” and dated “May 5, 1866 AD,” imitates the American primitive folk art style and is entitled Village Scene with Horse and Honn & Company Factory, (Fig. 1). The painting was seized by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation. This case study was thoroughly investigated previously and numerous telltale signs of forgery were identified (23). The results were unanimously consistent in proving that the work was a modern counterfeit. In our work, we demonstrate the power of 14C dating of microsamples using the painting previously studied by Smith et al. and shed further light on the modus operandi of Trotter to create this forgery.

Fig. 1.

Village Scene with Horse and Honn & Company Factory, 40.8 cm × 51.1 cm. In the lower right-hand corner, the painting is signed “Sarah Honn May 5, 1866 AD.” The blue rectangle on the left indicates the sampling location of the white paint; the one on the right indicates a close-up of the sampling location. The blue trapezoid in dashed lines shows a previous loss in the white paint due to the nature of the artificial aging used by Trotter––the paint is literally falling off the canvas. The triangle in continuous blue lines is a small extension of that loss to acquire a sample for the work reported here. If possible, conservators sample from existing losses or damages. The microscale present in the photo on the Right represents 5 mm. Image courtesy of James Hamm (Buffalo State College, The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY).

Results and Discussion

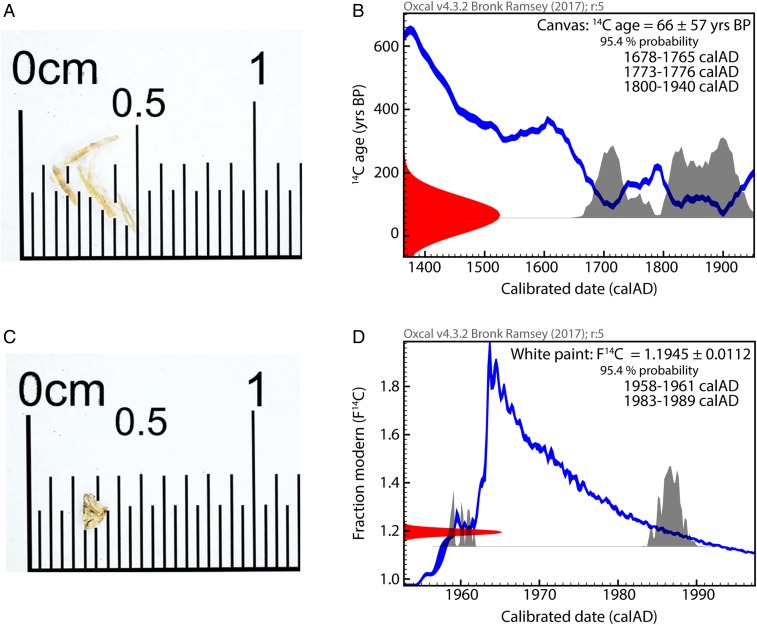

Determination of the age of the painting is based on the comparison of two samples, one from the support versus one of a paint layer (Fig. 2 A and C). The canvas dating affords a large time window covering the last quarter of the 17th to mid-20th century as displayed in Fig. 2B. This broad calendar age range is due to fluctuations in the 14C content of the atmosphere and the need for a 14C age calibration into calendar ages (24–26). Interestingly, the resulting age range does not contradict the signed date of 1866, nor does it exclude a later creation date either. As a consequence, the dating of the organic binder plays a more decisive role in authenticating this painting. Radiocarbon dating of the binder is a complex task, as the paint sample is a heterogeneous mixture of pigments within an organic binding medium. Following the criteria for sampling locations described in a pilot study (12), the sample selection was narrowed to the white-painted building (Fig. 1). Material analysis of the microsample identified titanium white and barium sulfate, i.e., inorganic pigments, in a mixed binding medium, overlaid by a shellac varnish layer (see SI Appendix for details regarding material characterization analysis). The use of a standard drying oil was expected as Trotter revealed having used standard oil colors; however, the presence of a proteinaceous material was also identified. These findings are supported by results from the study of Smith et al., who noted the presence of both oil and protein, i.e., egg or hide glue. With respect to 14C analysis, this dual carbon source is at first glance not ideal. However, with a deeper insight in paint treatise, it is well known that oil binders and egg tempera must be fresh for application; thus owing that both compounds are of natural source, it is reasonable to assume a similar 14C signature for both compounds. The presence of a varnish complicates the dating of the binder, since an additional carbon source is present that could have been applied any time after the paint (i.e., different 14C signature) and could introduce an error in the dating. This undesired layer was consequently removed prior to analysis to ensure that the evolved CO2 during analysis originates from the organic binder only. The original paint sample (Fig. 2C) weighed 160 µg, but only 58 µg of material remained after cleaning, which finally resulted in 19 µg of carbon for AMS analysis. The challenge of measuring 14C on only a few micrograms of carbon was met by directly coupling the EA, which combusts the sample, to the GIS (8, 10) of a modern tabletop-sized high-performance AMS spectrometer (27, 28). The results are unambiguous; the oil used as binder for the pigments contains an excess of 14C, characteristic of the 20th century nuclear testing period (Fig. 2D). The seeds, from which the oil was extracted, were harvested between 1958–1961 or 1983–1989 as displayed in Fig. 2D. The double outcome of calendar ages is due to the bomb peak calibration curve, that shows a sudden increase of the atmospheric 14C triggered by nuclear testing (1954–1963), followed by a decline (1963–present) due to CO2 removal from the atmosphere through the carbon cycle and its dilution with fossil fuel CO2. In either case, the results contradict the dating of the canvas and explicitly indicate a post-1950 production, i.e., a modern forgery.

Fig. 2.

Microscale samples and respective calibrated age plots. (Left) Details of microsampling, canvas fibers weighing 330-µg (A) and 160-µg paint material (C). (Right) Respective calibration of the 14C ages of the canvas fibers (B) and paint material (D) to real calendar ages using the calibration software OxCal v.4.3.2. The calibration curve (blue) allows the conversion of measured radiocarbon ages with their uncertainty (red) on the ordinate axis to the respective calendar ages on the abscissa axis. Radiocarbon results are reported in years “before present” (BP) and as fraction modern (F14C) for samples younger than 1950 (35). The black histograms indicate the resulting calibrated time intervals with a probability of 95.4%.

The clear disagreement between canvas and binder 14C ages reveals the modus operandi of Trotter in repainting older canvases to convey the illusion of authenticity. Our results bring further evidence in physical age to corroborate the results of Smith et al. (23), who also concluded that the support was recycled and older than the actual painting. During his trial in the US District Court of Connecticut, Trotter confirmed these observations (29). Indeed, he admitted to having acquired authentic aged paintings from the mid to late 19th century, from which the original paint layers were scraped off before application of new ground and pictorial layers. With 14C dating, the age of the forgery can be confined to a defined time interval, namely the object was either created in the 1950s or in the 1980s. With the statement by Trotter, who confessed to have painted the Sarah Honn forgery in 1985, the 14C age thus proves that the forged piece of art was created between 1983 and 1989.

Conclusion

One of the most significant findings to emerge from this study is that 14C dating of the paint layer is a powerful strategy for the unmasking of modern (post-1950) forgeries even when recycled older canvas supports have been used in an attempt to increase its credibility. Due to the success in minimizing the requisite sample size following technological advances in GIS-AMS, a paint sample no larger than 200 µg is sufficient for 14C analysis. Adequate samples, where no other source of carbon than the binder is present, are identified through a thorough pigment analysis (SI Appendix). The results from this study demonstrate that 14C dating of the canvas alone may not always be conclusive. The additional dating of the paint binding medium reveals the forger’s scheme or strategy where an appropriately aged canvas was used to convey the illusion of authenticity, which intentionally or not excludes 14C analysis as evidence. In comparison with pigment anachronism where forgeries are related to the pigments and additives used, radiocarbon dating of the pictorial layer binder offers decisive evidence, regardless of the level of sophistication of the forger, as it targets the only material which accurately reflects the image being assessed. Hence, in the arsenal of techniques available to uncover counterfeits, pigment anachronisms can only offer a terminus post quem date, while 14C dating can pinpoint the specific time window in which the painting was forged.

Nonetheless, one must bear in mind that the case study under discussion presented the only difficulty of an added varnish layer, which could be removed to create an ideal sample for 14C analysis of the binder. However, such cases represent the minority; a far larger proportion of artworks are likely to be more complex in composition with the presence of multiple paint layers, repairs, episodes of conservation, and introduction of synthetic or natural polymers, which through aging or chemical similarity to the binder may become difficult to recognize and separate by solvent extraction, thereby adding to the challenge of this approach.

For that reason, the method validated on the Trotter case study has the potential to become a decisive instrument to confidently answer the question of forgery or authenticity in oil paintings as long as sample selection is thoroughly carried out, i.e., the identification of original paint layers bearing no organic pigment, cleaned from varnish and/or natural or synthetic consolidants.

Method

Sample Selection and Characterization.

Following a multiinstrumental approach previously defined (12), the paint sample was fully characterized and its suitability, i.e., presence of inorganic pigments exclusively, was assessed for further 14C analysis. In their work, Smith et al. (23) already conducted X-ray fluorescence measurement, hereby allowing to narrow the sample selection to the white building as the observed elemental distribution hinted to the use of inorganic pigments. For Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis the sample was pressed in a diamond cell and analyzed using a Perkin-Elmer System 2000 in transmission mode. The spectrum was acquired over the 4,000–580-cm−1 range with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 16 accumulation scans. Raman spectroscopy was performed using a Renishaw InVia dispersive Raman spectrometer, equipped with a Leica DM microscope and 785-nm excitation laser (Renishaw HP NIR785). The laser power was adjusted between 0.01 and 1 mW, and the measurement times were set between 30 and 200 s. The microscope objective enabled 50× and 100× magnification. Evaluation and interpretation of the both FTIR and Raman spectra was carried out by comparison with published data and in-house databases from the Hochschule der Künste Bern.

Sample Preparation Prior 14C Analysis.

The canvas sample was cleaned by Soxhlet (30) and conventional ABA treatment (31). The varnish layer on the surface of the paint sample was removed by multiple ethanol cleaning steps, hereby also removing the PY3 traces, while potential carbonate contaminants were eliminated by washing with 0.5 M hydrochloric acid for 3 h at 80 °C (12).

14C Analysis.

All radiocarbon measurements were conducted on the Mini Carbon Dating System MICADAS at the laboratory of Ion Beam Physics at Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (27, 28, 32), which allows the measurement of both graphite (1 mg C) and gaseous samples (<100 µg C). Both the cleaned canvas material and paint sample were directly measured on the AMS as carbon dioxide following combustion in an elemental analyzer (8). Owing to the ultrasmall sample size, constant contamination was considered and accordingly corrected (33, 34). Radiocarbon results are reported as 14C ages (before 1950) and as fraction modern F14C for samples younger than 1950 (35). The measured data were further calibrated online with OxCal v.4.3.2 software (36, 37). For calibration of the canvas sample (Fig. 2B), the Intcal13 atmospheric calibration curve was used (38), while for the paint sample (Fig. 2D) with elevated concentration of 14C, the postbomb atmospheric NH1 curve was applied (39).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. James Hamm of State University of New York (SUNY) Buffalo State College for providing paint samples from the forged painting. The authors express their gratitude to Markus Küffner from the Swiss Institute for Art Research as well as to Markus Christl for support during preparation of the manuscript. Funding by an ETH grant (ETH-21 15-1) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Commentary on page 13158.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1901540116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Libby W. F., Anderson E. C., Arnold J. R., Age determination by radiocarbon content: World-wide assay of natural radiocarbon. Science 109, 227–228 (1949). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson D. E., Korteling R. G., Stott W. R., Carbon-14: Direct detection at natural concentrations. Science 198, 507–508 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett C. L., et al. , Radiocarbon dating using electrostatic accelerators: Negative ions provide the key. Science 198, 508–510 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel J. S., Southon J. R., Nelson D. E., Brown T. A., Performance of catalytically condensed carbon for use in accelerator mass-spectrometry. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 5, 289–293 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Middleton R., A review of ion sources for accelerator mass spectrometry. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 5, 193–199 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronk C., Hedges R., A gas ion source for radiocarbon dating. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 29, 45–49 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruff M., et al. , A gas ion source for radiocarbon measurements at 200 kV. Radiocarbon 49, 307–314 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruff M., et al. , On-line radiocarbon measurements of small samples using elemental analyzer and micadas gas ion source. Radiocarbon 52, 1645–1656 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruff M., et al. , Gaseous radiocarbon measurements of small samples. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 268, 790–794 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wacker L., et al. , A versatile gas interface for routine radiocarbon analysis with a gas ion source. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 294, 315–319 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahrni S. M., Wacker L., Synal H. A., Szidat S., Improving a gas ion source for C-14 AMS. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 294, 320–327 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendriks L., et al. , Combined 14 C analysis of canvas and organic binder for dating a painting. Radiocarbon 60, 207–218 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caforio L., et al. , Discovering forgeries of modern art by the 14C bomb peak. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 129, 1–6 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrucci F., et al. , Radiocarbon dating of twentieth century works of art. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 122, 983 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock F., Eastaugh N., Ford T., Townsend J. H., Bomb-pulse radiocarbon dating of modern paintings on canvas. Radiocarbon 61, 39–49 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coremans P., Van Meegeren’s Faked Vermeers and De Hooghs (Meulenhoff, Amsterdam, 1949). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Held J. S., Coremans P. B., Van Meegeren’s faked Vermeers and de Hooghs: A scientific examination. Coll. Art J. 10, 432–436 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chappell D., Hufnagel S., The Beltracchi affair: A comment on the most spectacular German art forgery case in recent times. J. Art Crime 7, 38 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saverwyns S., Russian avant‐garde… or not? A micro‐Raman spectroscopy study of six paintings attributed to Liubov Popova. J. Raman Spectrosc. 41, 1525–1532 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaplin T. D., Clark R. J. H., Identification by Raman microscopy of anachronistic pigments on a purported Chagall nude: Conservation consequences. Appl Phys A 122, 144 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khandekar N., et al. , A technical analysis of three paintings attributed to Jackson Pollock. Stud. Conserv. 55, 204–215 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keisch B., Miller H. H., Recent art forgeries–Detection by C-14 measurements. Nature 240, 491–492 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith G. D., Hamm J. F., Kushel D. A., Rogge C. E., “What’s wrong with this picture? The technical analysis of a known forgery” in Collaborative Endeavors in the Chemical Analysis of Art and Cultural Heritage Materials (ACS Symposium Series: Washington, DC, 2012), vol. 1103, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talma A., Vogel J. C., A simplified approach to calibrating 14 C dates. Radiocarbon 35, 317–322 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson G. W. How to cope with calibration. Antiquity 61, 98–103 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein J., Lerman J.-C., Damon P. E., Ralph E. K., Calibration of radiocarbon dates: Tables based on the consensus data of the workshop on calibrating the radiocarbon time scale. Radiocarbon 24, 103–150 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wacker L., et al. , Micadas: Routine and high-precision radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon 52, 252–262 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Synal H. A., Stocker M., Suter M., MICADAS: A new compact radiocarbon AMS system. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 259, 7–13 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jongbloed P. S., United States v. Robert Lawrence Trotter, Criminal no. N-89-59 (AHN), U.S. Department of Justice: District of Connecticut, 1990.

- 30.Bruhn F., Duhr A., Grootes P. M., Mintrop A., Nadeau M. J., Chemical removal of conservation substances by ‘soxhlet’-type extraction. Radiocarbon 43, 229–237 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajdas I., The radiocarbon dating method and its applications in Quaternary studies. Quat Sci. J. 57, 2–24 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Synal H. A., Developments in accelerator mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 349, 192–202 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanke U. M., et al. , Comprehensive radiocarbon analysis of benzene polycarboxylic acids (BPCAs) derived from pyrogenic carbon in environmental samples. Radiocarbon 59, 1103–1116 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welte C., et al. , Towards the limits: Analysis of microscale 14C samples using EA-AMS. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 437, 66–74 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reimer P. J., Brown T. A., Reimer R. W., Discussion: Reporting and calibration of post-bomb 14C data. Radiocarbon 46, 1299–1304 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsey C. B., Deposition models for chronological records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 42–60 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsey C. B. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reimer P. J., et al. , Intcal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0-50,000 years cal Bp. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua Q., Barbetti M., Rakowski A. Z., Atmospheric radiocarbon for the period 1950-2010. Radiocarbon 55, 2059–2072 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.