Abstract

Background:

The Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 allele is a well-known risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and sleep disturbances are commonly associated with AD. However, few studies have investigated the relationship between APOE ε4 and abnormal sleep patterns (N+) in AD.

Objective:

To examine the relationship between APOE genotype, Lewy body pathology, and abnormal sleep patterns in a large group of subjects with known AD load evaluated upon autopsy.

Method:

Data from 2,368 cases obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre database were categorized as follows: Braak Stage V/VI and CERAD frequent neuritic plaques as high load AD, Braak Stage III/IV and moderate CERAD as intermediate load AD, and Braak Stage 0/I/II and infrequent CERAD as no to low load AD. Cases discrepant between the two measures were discarded.

Results:

Disrupted sleep was more frequent in males (42.4%) compared to females (35.1%), and in carriers (42.3%) as opposed to non-carriers (36.5%) of ε4. Amongst female subjects with high AD load and Lewy body pathology, homozygous (ε4/ε4) carriers experienced disrupted sleep more often compared with heterozygous (ε4/x) or non-carriers of ε4. Such recessive, gender specific, and Lewy body association is reminiscent of the ε4 effect on psychosis in AD. However, such association was lost after adjusting for covariates. In subjects with no to low AD pathology, female ε4 carriers had significantly more nighttime disturbances than non-carriers; this effect is independent of the presence of Lewy body pathology.

Conclusion:

The influence of APOE ε4 on sleep disturbances is dependent on gender and severity of AD load.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Apolipoprotein E, Sleep behaviours, Lewy Bodies, Risk Factors, Neuropathology, Gender

1. Introduction

The Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 allele is well known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) [1]. It exhibits a gene dosage influence on the development of AD, such that one copy of the ε4 allele increases risk of AD by approximately 3 times, while carrying two copies increases risk by 8–15 times [2, 3]. Lewy bodies (LBs) are commonly found to co-exist with AD neuropathology and have been found to be present in over 40% cases of AD [4–6]. Unlike the widespread neocortical distribution of Lewy bodies in Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Lewy bodies in AD are encountered primarily in the amygdala [5,6]. Recent reports describing an association between APOE ε4 and presence of Lewy bodies in AD [7] suggest that stratification by the presence of Lewy bodies should be used when investigating the effect of APOE genotype in the manifestations of AD.

The importance of proper sleep for optimal cognitive and physiological functioning is widely known. An important study by Lim et al. [8] found that even the ε4-associated risk for AD can be reduced through better sleep consolidation. Unfortunately, the presence of abnormal sleep behaviours such as rising early in the morning or awakening during the night is a common clinical manifestation amongst AD patients, where the consequences of disrupted sleep not only affect the patient, but can also intensify caregivers’ burden [9].

The association between sleep disturbances and AD-related pathology has been examined in the past. While amyloid-β (Aβ) is found to be positively associated with reports of poor sleep [10], other studies indicate that abnormal sleep behaviours may render elders without dementia to become more vulnerable to pathological changes predisposing to AD [11, 12], suggesting for a bidirectional relationship between abnormal sleep and AD pathology [13]. However, despite sleep disturbances and APOE ε4 both being commonly associated with AD, few studies have examined the potential effect of APOE ε4 in the development of abnormal sleep patterns in subjects with known AD pathology load. This cross-sectional study will focus on the presence of abnormal sleep patterns as reported by an informant through the entire spectrum of AD pathological load, and their relationship with APOE ε4 and presence of Lewy bodies in the brain.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source:

The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre (NACC) database, comprised of clinical and neuropathological data compiled from Alzheimer’s Disease Centers across the United States, from visits conducted between September 2005 and September 2016, was used for this study. The Uniform Data Set (UDS) containing clinical and demographic data from the NACC, and Neuropathology (NP) Data Set containing autopsy data, were used for analyses. AD severity was evaluated according to the density of neocortical neuritic plaques (CERAD) and Braak staging for neurofibrillary degeneration, provided by the NP Data Set. The presence of abnormal sleep patterns (N+) during the month prior to the interview (NITE: Does the patient awaken you during the night, rise too early in the morning, or take excessive naps during the day?) was evaluated using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire quick version (NPI-Q) by collateral informants. The reported presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms were also obtained from the NPI-Q. Severity scores were not considered.

2.2. Subjects:

A total of 3, 771 autopsy cases with Braak staging and CERAD scores were available. Of these, NPI-Q N+ was completed in 3,478 cases. To ensure that information collected on the last clinical visit is relevant to the neuropathological data obtained upon autopsy, subjects with data collected more than two years prior to the death were excluded, resulting in 2,793 cases. Of these cases, APOE ε4 status was determined in 2,368 individuals. These subjects were further divided into three groups of increasing AD load based on NIA-Reagan criteria. Subjects with Braak Stage of 0, I, or II, and CERAD of 0 or 1, corresponding to a no to low likelihood of AD (N=516), were classified as no to low AD load (NAD group). Subjects with Braak Stage of III or IV, and CERAD of 2, corresponding to an intermediate likelihood of AD (N=192), were classified as intermediate AD load (IAD group). Similarly, subjects reflecting a high likelihood of AD (N=905), were classified as high AD load (HAD), and corresponded to Braak Stage of V or VI, and CERAD of 3. A total of 755 discrepant cases with CERAD and Braak stage that did not align with any of the severity categorization were eliminated, thus leaving 1,613 individuals for analysis. NIA-AA criteria was not used as data on Thal phase was not available in several subjects. The presence of Lewy bodies (LB+) were defined by the presence of Lewy body pathology in the brainstem, limbic region or amygdala, neocortical areas, olfactory bulb, or unspecified region, as determined by α-synuclein immunostaining.

2.3. Statistical Analysis:

Analyses were performed on patients stratified by AD severity (NAD, IAD, HAD), gender, and presence or absence of Lewy bodies (LB+/−). The χ2 test was employed for categorical data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality was used to determine normality, and the independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used for normal or non-normal distributions, respectively. Age at last clinical visit, years of education, race, depression, and anxiety, were compared between subjects with and without abnormal sleep patterns (N+/N-). Significant differences in any of these variables within each subgroup were analyzed as covariates when fitting binomial logistic regression models. An α level of 0.05 was used to evaluate significance in this study, and Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple testing when appropriate. SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Subject Demographics

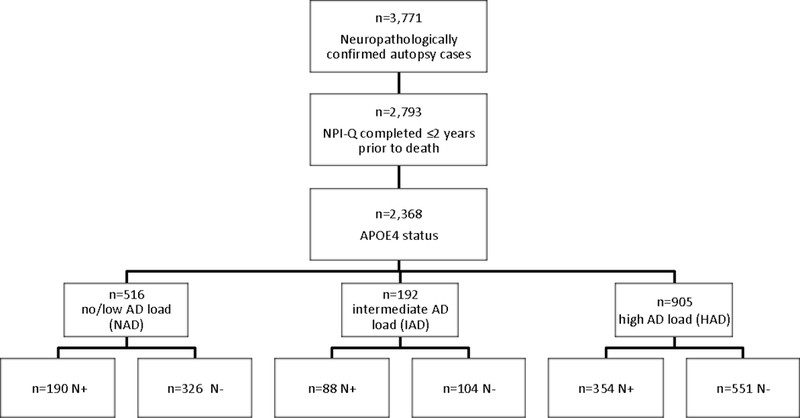

Independent of AD pathology, N+ was found to be more common amongst males, with 42%, compared to 34.4% in females (p=0.001), and in carriers (42.3%) over non-carriers (36.5%) of the APOE ε4 allele (p=0.017). Of the 1,613 individuals studied, 516, 192, and 905 subjects were assigned to NAD, IAD, and HAD groups, respectively (Figure 1). Carriers with two copies of the ε4 allele were absent in the NAD group, and very few were present in the IAD group. Consequently, the comparisons for these two groups were made simply between carriers (either one or two copy) and non-carriers.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the selection and number of neuropathologically confirmed cases of AD within each diagnostic sub-group. NPI-Q: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire Quick version. NAD: no/low AD load; IAD: intermediate AD load; HAD: high AD load. +/−: presence/absence. N: abnormal sleep behaviours.

Although the prevalence of N+ was similar across three groups of AD load, the prevalence within IAD (45.8%) was statistically higher than NAD (36.8%). No significant differences were detected between IAD and HAD (39.1%), and between NAD and HAD.

Clinical and demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. The study population was largely Caucasian, with most subjects being fairly well educated. A male predominance in N+ is noted across all three groups. Across all groups, the median age at last clinical visit was higher in N-compared to N+, significance reached only in the NAD and HAD groups. Prominent differences in the number of individuals with depression was observed in the NAD and HAD groups, while anxiety was significantly more prevalent in N+ subjects across all groups (Table 1). Collateral information was collected predominately from spouses, and nearly half of all collateral informants report to reside with subjects (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1:

General characteristics and demographics of the study population. Comparisons for each variable were made between N+ and N-of each subgroup. SD: standard deviation; NAD: no/low AD load; IAD: intermediate AD load; HAD: high AD load. +/−: presence/absence. N: abnormal sleep behaviours.

| NAD | IAD | HAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N− | N+ | N− | N+ | N− | N+ | ||

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | * | ||||||

| Male | 179 (54.9) | 108 (56.8) | 51 (49) | 56 (63.6) | 294 (53.5) | 221 (62.4) | |

| * | * | ||||||

| Age, median ± SD years | 79±12.6 | 71.5±12.8 | 86±8.5 | 83±9.2 | 80±10.2 | 78±11.0 | |

|

Years of education,

mean ± SD years |

* | ||||||

| 15.1±3.2 | 15±2.8 | 15.6±3.2 | 15.2±3.3 | 15±3.3 | 15.5±3.1 | ||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 308 (95.7) | 182 (96.3) | 102 (99) | 85 (96.6) | 515 (94.3) | 333 (94.6) | |

| Black/African American | 11 (3.4) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3.4) | 25 (4.6) | 14 (4) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 6 (1.1) | 5 (1.4) | |

| Others | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Depression (NPI-Q) | * | * | |||||

| 86 (26.4) | 82 (43.2) | 32 (30.8) | 34 (38.6) | 156 (28.3) | 155 (43.8) | ||

| * | * | * | |||||

| Anxiety (NPI-Q) | 68 (20.9) | 83 (43.7) | 24 (23.1) | 37 (42) | 173 (31.4) | 185 (52.3) | |

p ≤ 0.05.

3.2. APOE ε4 and Lewy Bodies

Table 2 shows that in individuals with low AD load (NAD group), carriers of ε4 are more likely to develop N+ compared to non-carriers (OR 2.48, 95% CI: 1.26–4.86), though this was statistically significant in females only. Adjusting for covariates had a moderate yet non-significant effect on the association, reducing the OR from 2.48 (95% CI: 1.26–4.86) to 2.16 (95% CI: 1.06–4.40). In the HAD group, the prevalence of N+ was higher in homozygous carriers (ε4/ε4) compared against heterozygous (ε4/x) or non-carriers, and this was particularly prominent in females (OR 1.88, 95% CI: 1.03–3.41), however the association was lost after adjusting for covariates. A similar but also non-significant trend between carriers and non-carriers was observed across the IAD group, both before and after controlling for covariates.

Table 2:

Regression analyses on the relationship of APOE ε4 on abnormal sleep patterns. NAD: no/low AD load; IAD: intermediate AD load; HAD: high AD load; OR: odds ratio.

| Males |

Females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| NAD | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 1.13 (0.62–2.07) | 1.05 (0.57–1.94) | 2.48 (1.26–4.86) * | 2.16 (1.06–4.40) * | |

| Age last visit | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) * | |||

| Depression | 1.00 (0.52–1.93) | 1.49 (0.63–3.53) | |||

| Anxiety | 2.88 (1.02–8.14) * | 1.28 (0.66–2.48) | |||

| IAD | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 1.20 (0.56–2.57) | 1.26 (0.58–2.72) | 1.39 (0.57–3.41) | 1.34 (0.53–3.36) | |

| Anxiety | 2.02 (0.89–4.55) | 2.90 (1.08–7.80) * | |||

| HAD | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 1.16 (0.71–1.91) | 1.13 (0.68–1.70) | 1.88 (1.03–3.41) * | 1.55 (0.83–2.90) | |

| Age last visit | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | |||

| Yrs Education | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | |||

| Depression | 1.62 (1.10–2.41) * | 1.41 (0.85–2.32) | |||

| Anxiety | 1.87 (1.28–2.73) * | 2.25 (1.38–3.65) * | |||

p ≤ 0.05.

In order to investigate the possibility that N+ is also influenced by Lewy bodies (LB), the association between Lewy bodies and N+, independent of APOE genotype, was examined. Table 3 shows that the presence of Lewy bodies is not a significant predictor of N+ across AD severity in neither gender. However, a slight negative trend between LB and N+ was noted in females, particularly in HAD females (OR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.52–1.27), whereas a general positive trend was observed in males across all groups of AD severity (Table 3).

Table 3:

Regression analyses on the relationship of Lewy bodies on abnormal sleep patterns. NAD: no/low AD load; IAD: intermediate AD load; HAD: high AD load; OR: odds ratio.

| Males |

Females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| NAD | |||||

| Lewy body | 1.27 (0.72–2.24) | 1.49 (0.80–2.77) | 1.00 (0.45–2.20) | 0.97 (0.42–2.23) | |

| Age last visit | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) * | |||

| Depression | 1.65 (0.94–2.88) | 1.79 (0.95–3.39) | |||

| Anxiety | 3.66 (2.05–6.56) * | 1.28 (0.66–2.50) | |||

| IAD | |||||

| Lewy body | 2.07 (0.92–4.70) | 2.25 (0.98–5.17) | 1.46 (0.56–3.78) | 0.99 (0.35–2.86) | |

| Anxiety | 2.11 (0.92–4.86) | 2.95 (1.02–8.52) * | |||

| HAD | |||||

| Lewy body | 1.06 (0.74–1.51) | 1.04 (0.72–1.50) | 0.82 (0.52–1.27) | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | |

| Age last visit | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | |||

| Yrs Education | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | |||

| Depression | 1.64 (1.11–2.44) * | 1.40 (0.84–2.30) | |||

| Anxiety | 1.84 (1.25–2.69) * | 2.31 (1.42–3.76) * | |||

p ≤ 0.05.

3.3. Stratification by Lewy Body Pathology

To analyze whether the relationships or observed trends between APOE ε4 and N+ could be attributed to the formation of Lewy bodies, subjects were further stratified by the presence or absence of Lewy body pathology. In NAD females, the significant correlation between APOE ε4 carriers and N+ remained upon the removal of the small number of LB+ females (14%) (OR 2.28, 95% CI: 1.04–5.01), and this can be contrasted with the absence of any significant correlation between ε4 on N+ in LB+ females (Table 4). No significant effect of ε4 were found in male carriers of this group, both before and after Lewy body stratification.

Table 4:

Regression analysis on the relationship between APOE ε4 and abnormal sleep patterns after stratification by Lewy bodies (LB+/−) and gender in NAD (no/low AD load) and HAD (high AD load) subjects. +/−: presence/absence.

| Males |

Females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| NAD | |||||

| LB+ | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 2.18 (0.65–7.24) | 2.03 (0.53–7.77) | 1.26 (0.18–8.97) | 0.71 (0.07–7.09) | |

| Age last visit | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.98 (0.91–1.07) | |||

| Depression | 1.60 (0.49–5.23) | 1.09 (0.16–7.52) | |||

| Anxiety | 4.83 (1.20–19.5) * | 7.00 (0.82–59.71) | |||

| LB- | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) | 0.8 (0.37–1.73) | 2.59 (1.25–5.39) * | 2.28 (1.04–5.01) * | |

| Age last visit | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) * | |||

| Depression | 1.58 (0.83–3.02) | 1.75 (0.87–3.54) | |||

| Anxiety | 3.59 (1.87–6.90) * | 0.93 (0.45–1.94) | |||

| HAD | |||||

| LB+ | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 1.37 (0.64–2.90) | 1.25 (0.57–2.73) | 2.96 (1.22–7.20) * | 2.32 (0.91–5.79) | |

| Age last visit | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | |||

| Education | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 1.15 (0.98–1.34) | |||

| Depression | 1.59 (0.82–3.08) | 1.70 (0.70–4.16) | |||

| Anxiety | 2.33 (1.29–4.23) * | 1.93 (0.83–4.53) | |||

| LB- | |||||

| APOE ε4 | 1.04 (0.54–2.00)* | 1.07 (0.54–2.11) | 1.35 (0.59–3.09) | 1.13 (0.47–2.70) | |

| Age last visit | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | |||

| Education | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | |||

| Depression | 1.71 (1.03–2.83) * | 1.30 (0.70–2.42) | |||

| Anxiety | 1.52 (0.92–2.52) | 2.30 (1.25–4.22) * | |||

p ≤ 0.05.

On the other hand, Lewy body stratification in the HAD group revealed a recessive-like effect of ε4 on N+. In LB+ females, the effect of ε4 on N+ is strongest in homozygous carriers, such that these individuals show a significantly higher prevalence of N+ compared to heterozygous or non-carriers of ε4 (OR 2.96, 95% CI: 1.22–7.20). Adjusting for covariates reduced the OR to 2.32, 95% CI: 0.91–5.79, resulting in the loss of statistical significance (Table 4). The much weaker effect of two ε4 copies in LB+ males did not reach significance.

4. Discussion

Given that APOE ε4 is an important genetic risk factor for AD with a dosage-dependent influence on the onset and progression of AD [14–16], our finding that patients with two copies of the ε4 allele were predominately in the HAD group, with very few to none in IAD and NAD groups, respectively, was not surprising.

Controlling for age, depression, and anxiety, NAD female carriers of the ε4 allele are more commonly associated with N+ than non-carriers. Moreover, this is not correlated to the formation of Lewy bodies, as the significant association remained upon the elimination of LB+ individuals (Table 4). This suggests that APOE ε4 is associated with N+ in subjects with low AD load or even in otherwise healthy individuals, and is in line with a recent clinical study that found evidence of a relationship between the presence of APOE ε4 and poor objective sleep quality in healthy individuals screened for cognitive impairments [17]. Our finding provides pathological evidence to indicate that ε4 carriers, compared to non-carriers, are at a higher risk of developing sleep disturbances, despite having mild to no AD load and Lewy body pathology.

In an unadjusted model, APOE ε4 seems to exert a recessive-like influence on N+ in HAD subjects such that while one copy is insufficient, carriers with two copies of the ε4 allele are at a higher risk of developing N+, in contrast to the dose-dependent influence of APOE ε4 on AD. This is demonstrated through the significant difference in the prevalence of N+ amongst homozygous carriers of the ε4 allele, as compared to heterozygous or non-carriers of ε4. The higher prevalence of N+ found in homozygous carriers, present only upon stratification by Lewy bodies, is female specific and exclusive only to subjects with Lewy body pathology (Table 4). However, after controlling for clinical and demographic confounders, significance on the recessive-like effect of ε4 on N+ in HAD females with Lewy body pathology was lost. A similar recessive-like effect of the ε4 allele in females with high AD load and Lewy body pathology has also been reported for psychosis, another common symptom in AD [18].

Our results show that the effects of APOE ε4 on N+ seem to be gender specific, as demonstrated by the positive correlation between APOE ε4 and N+ in the NAD and HAD groups, which were restricted to females only. This strong gender influence on the effects of APOE ε4 on AD is not new [19] – having previously shown to escalate the risk of AD in females more than males [20], increase the likelihood of developing AD-related symptoms such as dis-inhibition and irritability in females [21], and exert a female specific effect on the development of psychosis [18]. On the other hand, although non-significant, we found a positive and male specific trend between Lewy body pathology and N+ across all groups of AD load. The stronger prevalence of AD with Lewy bodies in males [7, 22], may explain why this trend was observed in males only. Previous findings, along with our results, suggests for a stronger influence of the APOE ε4 on AD and AD-related symptoms in females over males.

Although many previous studies have investigated the relationship between amyloid and poor sleep quality in the past, few previous studies have examined the relationship between APOE ε4 status and sleep disturbances in AD. A longitudinal study of 44 subjects clinically diagnosed with probable AD who were followed and measured for sleep disturbances found non-carriers of the ε4 allele to experienced greater sleep disturbances during AD progression [23]. Based on our study however, no such trend seems to exist. This discrepancy could be related to the differences in characterization of sleep disturbances, or variations in methods of assessment (self-reported assessment, caregiver’s assessment, physiological measures).

The evaluation of sleep disturbances in this study is based solely on the NPI-Q question, and presents a limitation in our study as this question reflects the presence of abnormal sleep patterns only in the past one month, inhibiting the distinction between long term versus short term sleeping behaviours. The answers to this question, provided by a collateral informant, may have been an incomplete representation of the presence or absence of abnormal sleep patterns in patients, depending on the relationship between the informant and the patient, and whether the informant resides with the patient. In addition, this question alone does not provide information on the patient’s quality of sleep or sleep latency -parameters in which changes are common in the aging population, but even more pronounced in AD patients [24–26]. As such, other methods of monitoring sleep disturbances, such as electrophysiological recordings, may provide a more objective assessment on the effects of various risk factors on sleep disturbances in AD patients. It may also be interesting to investigate in the future whether sleep impairments experienced by subjects with no or minimal AD load are different from those experienced by individuals with high AD load. Finally, as with most other studies using the NACC database, complete randomization of subjects was likely not achieved, given our study subjects being predominantly Caucasians with relatively high education levels. Individuals enrolled in a voluntary observational program involving regular visits to an Alzheimer’s Disease Centre (ADC) would likely be a stronger representation of the urban population, affecting the generalizability of our results.

5. Conclusion

The influence of APOE ε4 on N+ is largely female predominant, and seems to be correlated with the presence of Lewy bodies in females with high AD load, though significance was lost after controlling for covariates. This is similar to a previous report on the effect of APOE ε4 on psychosis in AD patients, which was also found to be female specific, and mediated through the formation of Lewy bodies [18]. Our unexpected finding that the ε4 allele significantly increases the risk of developing N+ in female subjects with no or low AD pathology is suggestive of the possible effects of APOE ε4 beyond those currently known, particularly in individuals without AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [Grant number 313912]. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material:

Supplementary Table 1 outlines the breakdown of the number of subjects in each diagnostic subgroup.

Conflict of Interest:

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References:

- [1].Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63(3):287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Uchikado H, Lin WL, DeLucia MW, Dickson DW. Alzheimer disease with amygdala Lewy bodies: a distinct form of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(7):685–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowsk JQ, Lee VM. Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17(2):225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hamilton RL. Lewy bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: a neuropathological review of 145 cases using alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol. 2000; 10(3):378–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chung EJ, Babulal GM, Monsell SE, Cairns NJ, Roe CM, Morris JC. Clinical Features of Alzheimer Disease With and Without Lewy Bodies. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(7):789–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lim A, Yu L, Kowgier M, Schneider J, Buchman A, Bennett D. Modification of the Relationship of the Apolipoprotein E ε4 Allele to the Risk of Alzheimer Disease and Neurofibrillary Tangle Density by Sleep. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70(12):1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vitiello MV, Borson S. Sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(10):777–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen DW, Wang J, Zhang LL, Wang YJ, Gao CY. Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid-β Levels are Increased in Patients with Insomnia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018; 61(2):645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Carvalho DZ, St Louis EK, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Lowe VF, Roberts RO, Mielke MM, Przybelski SA, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr, Vemuri P. Association of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness With Longitudinal β-Amyloid Accumulation in Elderly Persons Without Dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2018. June 1;75(6):672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sprecher KE, Koscik RL, Carlsson CM, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Okonkwo OC, Sager MA, Asthana S, Johnson SC, Benca RM, Bendlin BB Poor sleep is associated with CSF biomarkers of amyloid pathology in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2017. August 1;89(5):445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ju YE, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology--a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;10(2):115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Farlow MR. Alzheimer’s disease: clinical implications of the apolipoprotein E genotype. Neurology. 1997;48(5 Suppl 6):S30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hostage CA, Roy Choudhury K, Doraiswamy PM, Petrella JR, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Dissecting the gene dose-effects of the APOE epsilon4 and epsilon2 alleles on hippocampal volumes in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Spira AP, An Y, Resnick SM. Self-reported sleep and beta-amyloid deposition in older adults-reply. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):651–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Drogos LL, Gill SJ, Tyndall AV, Raneri JK, Parboosingh JS, Naef A, et al. Evidence of association between sleep quality and APOE epsilon4 in healthy older adults: A pilot study. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1836–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kim J, Fischer CE, Schweizer TA, Munoz DG. Gender and Pathology-Specific Effect of Apolipoprotein E Genotype on Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14(8):834–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Payami H, Zareparsi S, Montee KR, Sexton GJ, Kaye JA, Bird TD, et al. Gender difference in apolipoprotein E-associated risk for familial Alzheimer disease: a possible clue to the higher incidence of Alzheimer disease in women. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58(4):803–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative I. Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(4):563–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Xing Y, Tang Y, Jia J. Sex Differences in Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Modifying Effect of Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 Status. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:275256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stern Y, Jacobs D, Goldman J, Gomez-Tortosa E, Hyman BT, Liu Y, et al. An investigation of clinical correlates of Lewy bodies in autopsy-proven Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(3):460–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yesavage JA, Friedman L, Kraemer H, Tinklenberg JR, Salehi A, Noda A, et al. Sleep/wake disruption in Alzheimer’s disease: APOE status and longitudinal course. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17(1):20–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Deschenes CL, McCurry SM. Current treatments for sleep disturbances in individuals with dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):20–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bombois S, Derambure P, Pasquier F, Monaca C. Sleep disorders in aging and dementia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(3):212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu YH, Swaab DF. Disturbance and strategies for reactivation of the circadian rhythm system in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2007;8(6):623–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.