Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is the leading infectious cause of death. Synthesis of lipids critical for Mtb’s cell wall and virulence depends on phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PptT), an enzyme that transfers 4’-phosphopantetheine (Ppt) from coenzyme A to diverse acyl carrier proteins (ACPs). We identified a compound that kills Mtb by binding and partially inhibiting PptT. Killing of Mtb by the compound is potentiated by another enzyme encoded in the same operon, Ppt hydrolase (PptH), that undoes the PptT reaction. Thus, loss of function mutants of PptH displayed antimicrobial resistance. Our PptT-inhibitor co-crystal structure may aid further development of anti-mycobacterial agents against this long-sought target. The opposing reactions of PptT and PptH uncover a regulatory pathway in CoA physiology.

One-sentence summary:

A small molecule inhibitor selectively kills mycobacteria by targeting a pathway that a countering enzyme makes vulnerable.

Beginning about eighty years ago, the “golden age” of antibiotic development led to a plethora of drugs that inhibited four classes of targets: enzymes involved in the synthesis of nucleic acids, proteins, cell walls or folate (1). With antimicrobial resistance rising to the level of a global health emergency (2, 3) and with tuberculosis the leading cause of death from infectious disease (3), investigators have sought to develop whole-cell-active inhibitors of a wider range of mycobacterial targets, including enzymes involved in the synthesis of cofactors such as coenzyme A (CoA) (4–7).

An estimated 9% of 3500 known enzyme reactions depend on CoA (7), an evolutionarily conserved co-factor formed from the phosphoadenylation of 4’-phosphopantetheine (Ppt). Ppt’s sulfhydryl group forms thioester bonds upon acylation, enabling the synthesis of complex lipids when Ppt is enzymatically transferred from CoA to apo-acyl carrier proteins (ACPs). Mtb encodes two enzymes that catalyze the conversion of apo- to holo-ACPs via transfer of Ppt from CoA onto the carrier protein: Ppt transferase (PptT) and ACP synthase (AcpS). PptT and AcpS share no significant similarity at sequence or structural levels (8–10) and they activate different sets of ACPs. PptT, encoded by rv2794c, charges ACPs for the synthesis of structural lipids—mycolic acids of the cell wall—and virulence lipids, such as phthiocerol dimycoserosates (PDIMs) that suppress host immune reactions (10–12). PptT is essential to Mtb both in vitro and during infection of mice (13).

Both the synthesis of CoA and the transfer of Ppt have been targets of extensive drug development efforts (4,14,15) but no compounds have been reported that are bactericidal to wildtype Mtb through inhibition of these pathways. Here we report the discovery of a drug-like amidino-urea that kills Mtb by binding PptT, spares other bacteria and mammalian cells, and blocks growth of Mtb in the mouse. Analysis of resistant mutants led to the discovery of an enzyme, a Ppt hydrolase (PptH), whose loss of function represents a new mechanism of antimicrobial resistance.

Identification of a mycobactericidal amidino-urea

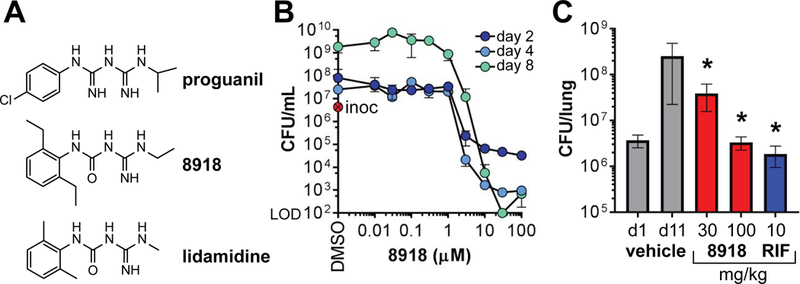

A screen of over 90,000 compounds representative of the Sanofi collection of small molecules identified the amidino-urea 1-((2,6-diethylphenyl)-3-N-ethylcarbamimodoyl)urea, hereafter called 8918 (Fig. 1A). 8918 had an MIC90 (the minimum concentration tested that inhibited growth by ≥90%) of 3.1 μM against a lab strain of Mtb that is virulent in mice (H37Rv) (Table 1). MIC90’s varied no more than 2-fold when the carbon source was changed from the standard combination of glucose plus glycerol to glucose, glycerol, acetate or cholesterol. The MIC90s ranged from 0.56 μM to 3.0 μM (median, 1.5 μM) against 29 clinical isolates of Mtb, 14 of which were resistant to one or more of 9 TB drugs and 3 of which were individually resistant to 3, 4 or 6 drugs, respectively (Table S1), suggesting that 8918 was inhibiting a distinct target. 8918 reduced the CFU of Mtb H37Rv from 106 per mL to less than the limit of detection within 8 days (Fig. 1B). The compound closely resembles proguanil, an FDA-approved drug that inhibits the folate pathway in malaria parasites (Fig. 1A). Proguanil and its active form, cycloguanil (Fig. S1), were inactive on Mtb, and 8918 did not appear to act by impairing Mtb’s folate synthesis (Fig. S2). Lidamidine, an antidiarrheal drug, also resembles 8918 (Fig. 1A), but was poorly active on Mtb (MIC90 >100 μM; MIC50 = 125 μM). The MBC99 of 8918 (the minimum concentration tested that was bactericidal for ≥ 99% of the bacteria) was 6.25 μM against Mtb and 3.13 μM against M. smegmatis. In contrast, 8918 was inactive against S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, four species of Streptomyces and C. albicans and noncytotoxic to human hepatoma cells (Table S2).

Fig. 1. Antimycobacterial activity of 8918 in vitro and in mice.

(A) Structures of proguanil, 8918 and lidamidine. (B) In vitro activity against Mtb H37Rv. Colony-forming units (CFU) remaining after treatment with 8918. Inoc = inoculum at day 0. Means ± SD of triplicates in 1 experiment representative of 3. (C) In vivo activity against Mtb H37Rv. Histogram represents log10 CFU from the lungs of BALB/c mice. One day after intranasal inoculation of 106 Mtb H37Rv Mtb, mice were treated via oral gavage, 4 days per week over 2 weeks and then euthanized. Results are means ± SD for 5 mice per group in 1 experiment representative of 2. Results for the 8918-treated groups were statistically significantly different than for the vehicle-treated group (*; P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA).

Table 1. 8918-resistant mutants of Mtb.

MIC90 (μM) of 8918, proguanil, lidamidine, isoniazid (INH), para-aminosalicyclic acid (PAS), rifampicin (RIF), ethambutol (EMB), and moxifloxacin (MOXI). Strains in bold were used in subsequent studies as representative strains for their respective mutations. Mutations in strains A1, A4, A6, B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 were found by whole-genome resequencing. The other mutations were found by Macrogen sequencing of the PCR amplified gene.

| 8918 | proguanil | lidamidine | INH | PAS | RIF | EMB | MOXI | Gene mutated | |

| WT | 3.13 | >100 | >100 | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | none |

| A1 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.2 | 3.13 | <0.02 | rv2795c H246N |

| A2 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.1 | 3.13 | <0.02 | rv2795c H246N |

| A3 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c H246N |

| A4 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | pptT W170S |

| A5 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.2 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c G266V |

| A6 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c V203F |

| B1 | 100 | * | * | 0.39 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 6.25 | <0.02 | pptT W170L |

| B2 | >100 | * | * | 1.56 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c G266V |

| B3 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c R321R, |

| H246N | |||||||||

| B4 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 6.25 | 0.04 | rv2795c D51E |

| B5 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c D24N |

| B6 | >100 | * | * | 0.39 | <0.05 | 0.1 | 6.25 | <0.02 | rv2795c A41G |

not tested

After oral administration to mice of 100 mg/kg 8918 in 0.6% methylcellulose/Tween 80 (99.5/0.5, vol/vol), the compound was bioavailable with a peak blood level of 2230 ng/mL at 0.25 h, but the t1/2 was brief (6.7 h) in association with rapid microsomal metabolism, a liability being addressed in ongoing studies. Nonetheless, accumulation in lung was 42-fold higher than in plasma (9200 ng.h/mL), encouraging us to test in vivo efficacy. In BALB/c mice infected intranasally with 106 Mtb H37Rv, oral administration of 8918 at 100 mg/kg per day, 4 days per week for 8 doses prevented the replication of Mtb in the lungs as effectively as rifampin (10 mg/kg) dosed on the same schedule (Fig. 1C).

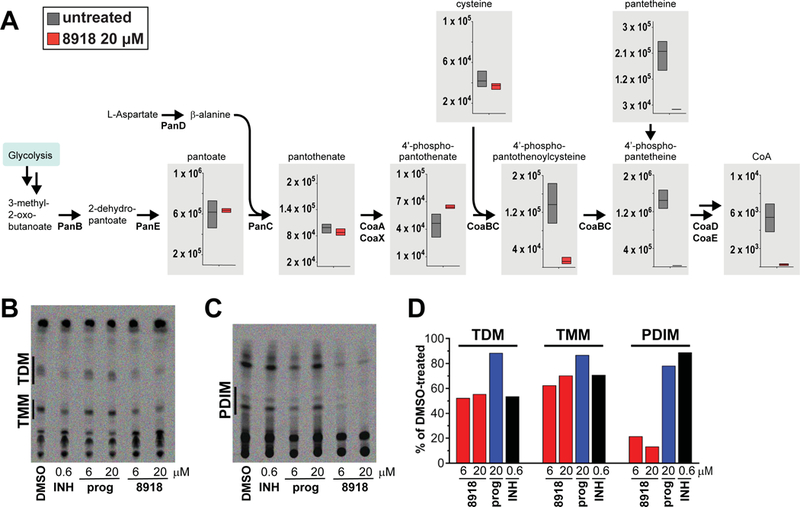

To further explore 8918’s mode of action, we compared its impact on the Mtb metabolome with that of proguanil and 4 TB drugs with known targets: isoniazid, an inhibitor of a 2-trans-enoyl-ACP reductase in mycolic acid synthesis; streptomycin, an inhibitor of the ribosome; rifampin, an inhibitor of RNA polymerase; and para-aminosalicylic acid, an inhibitor of folate synthesis. We exposed a mat of Mtb on a filter to 20 μM 8918 in the underlying agar. Under these conditions, this concentration of 8918 does not halt growth of the bacterial population, which is at a cell density >103 higher than the standard conditions for MIC determination and which grew further over a week before addition of 8918 (Fig. S3). We assayed the cells after a 24 hour exposure to 8918 to focus on primary rather than secondary effects, and observed marked changes in abundance of CoA and precursors 4’-phosphopantothenate, pantetheine, 4’-phosphopantothenoylcysteine and 4’-phosphopantetheine (Fig. 2A). At 48 hours, we also tested the impact of lidamidine and proguanil, which accumulated in Mtb to 9- and 10-fold higher levels than 8918, respectively (Fig. S4). Of 37 metabolites in a discriminatory panel, concentration- responsive changes specific to 8918 and not proguanil were seen in 3 metabolites in the CoA path (propionyl/propanoyl CoA, 2-dehydropantolactone and 3-hydroxypropionyl-CoA) and 2 metabolites whose production involves CoA (methyl citrate and malate), while (R)-pantoate levels declined and CoA was no longer depleted (Fig. S5A–F). Even though the significance of increases or decreases in specific pool sizes cannot be interpreted without flux analyses, the observed changes serve as a qualitative flag for affected pathways and bore little resemblance to the metabolomic impact of the 4 clinically used TB drugs (16) (Fig. S6).

Fig. 2. Impact of 8918 on Mtb metabolites and lipids.

(A) Impact on metabolites. Filter-grown Mtb was transferred to plates containing 7H9 medium with or without 8918 and lysates collected 24 hours later for LC-MS. The Y-axis indicates raw intensity values for the area under the curve for each metabolite peak. Boxes represent the range of peak areas of triplicate samples. The center bar represents median raw intensity value for each metabolite peak. (B) Impact on synthesis of TDMs and TMMs. M. bovis var. Bacille Calmette-Guérin was incubated with DMSO vehicle alone, isoniazid (INH, 0.6 μM), proguanil (prog., 6.25 or 20 μM), or 8918 (6.25 or 20 μM) for 12 hours, then exposed for 24 hours to 14C acetate. Extracted lipids were subjected to TLC as described (30) (24-hour Phosphorimager exposure). (C) Impact on synthesis of PDIMs. The experiments were done as in (B) but using 14C propionate (5-day Phosphorimager exposure). (D) Quantitation of results from (B) and (C) (24-hour exposures for both). Results for (A-D) are each from one experiment representative of two independent experiments.

In sum, 8918 is a drug-like, non-cytotoxic, narrow-spectrum, mycobactericidal compound with whole-cell activity in axenic culture and efficacy in mice, whose target(s) seemed likely to be distinct from the targets of many TB drugs and to be related to the formation or use of CoA. These findings encouraged us to isolate spontaneous resistant mutants for target identification.

Two classes of mutants resistant to 8918

The frequency of resistance of Mtb H37Rv to 8918 at 4 × MIC90 was 3×10−7, comparable to that of clinically used TB drugs; no mutants could be isolated at 8 × MIC90. We isolated 12 resistant clones. All had MIC90s > 100 μM to 8918, but were as sensitive as wild-type Mtb to rifampin, isoniazid and ethambutol (Table 1).

Whole genome resequencing identified two genes whose SNPs were candidates for mediating resistance. The less frequently mutated gene (2/12 clones) was rv2794c, encoding PptT. Most of the resistant clones (10/12 with 7 distinct mutations) were mutated in rv2795c, a gene adjacent to pptT in the same operon. Moreover, we isolated 12 8918-resistant clones of M. smegmatis and all were point mutants or deletion mutants in the homolog of rv2795c. rv2795c encodes a protein of unknown function that is conserved among mycobacterial species. Because rv2795c has been characterized as non-essential (17), it was unlikely to encode the target. In contrast, because PptT is essential in Mtb (13), it was a candidate for being the target. Thus our next step was to confirm if PptT was indeed the target of 8918.

Impact of 8918 on Mtb lipids

An inhibitor of PptT would impair the conversion of apo-ACPs to holo-ACPs for the synthesis of mycolates and PDIMS, among other lipids (13). Consistent with this, TLC analysis of mycobacteria labeled with 14C-acetate or 14C-propionate demonstrated marked 8918-mediated impairment of the synthesis of trehalose dimycolates (TDMs), trehalose monomycolates (TMMs) and PDIMs. Isoniazid, as expected, inhibited synthesis of TDMs and TMMs but not PDIMs. Proguanil had no observable effect on the mycolates or PDIMs (Fig 2B–D).

For a wider survey, we undertook a lipidomic analysis of 8918’s impact on intact Mtb, again using a 24-hour exposure at a concentration (20 μM) that, as noted, was sublethal for a dense mycobacterial mat on a filter, as reflected by the cells’ continued growth. In the absence of new synthesis, replication could favor the loss of slowly turning over lipids by dilution. In contrast to impact on the de novo synthesis of certain lipids, the impact of a brief, sublethal exposure to 8918 on the abundance of lipid species was complex and variable across experiments, overlapping in part with the response to isoniazid, which was consistently observed (Fig. S7; Table S3). In any one experiment, exposure to 8918 appeared to affect fewer than 5% of 8954 features (discrete ion count peaks with a distinctive retention time and m/z ratio) revealed by mass spectrometry of Mtb lipid extracts (Fig. S8). Some of these changes may have reflected regulatory responses to 8918’s depletion of CoA, as well as turnover of compound lipids, resulting in an apparent increase in the levels of some of their pre-formed components.

In all, the impact of 8918 on synthesis of TDMs, TMMs and PDIMs was consistent with inhibition of PptT in the intact cell. However, neither the metabolomic nor the lipid synthesis studies excluded that there might be other targets of 8918, nor established whether PptT was the functionally relevant target for 8918’s ability to kill Mtb.

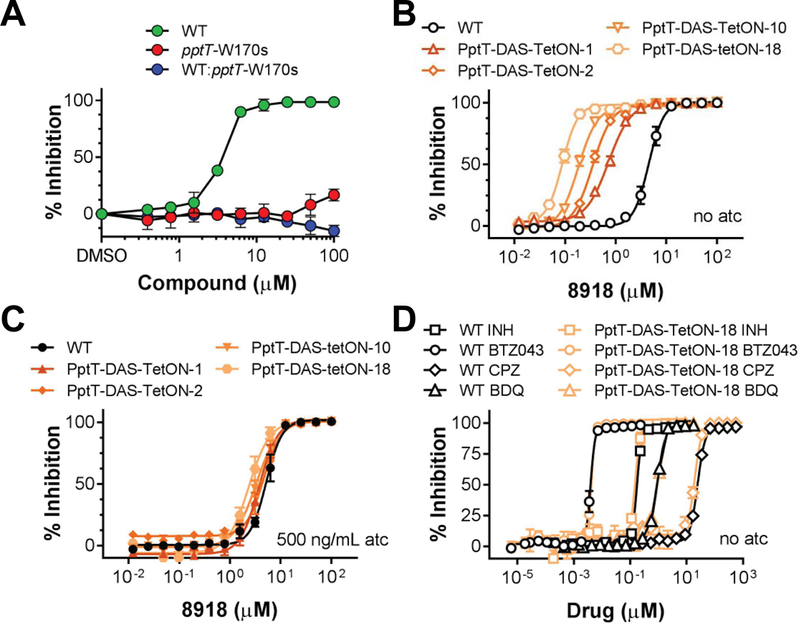

Confirmation that PptT is the functionally relevant target of 8918

Two independent point mutants in PptT conferred high-level resistance to 8918 (Table 1), and introduction of the resistance-associated allele pptTW170S into WT Mtb conferred high-level resistance on the WT strain (Fig. 3A). These results established the functional relevance of PptT as a target of 8918 and showed that the resistance allele is dominant. Moreover, we confirmed that four Mtb strains made selectively hypomorphic for PptT to different degrees (18–20) were more susceptible to 8918 in proportion to the strength of suppression of PptT expression than the same strains expressing WT levels of PptT (Fig. 3B and Fig. 3C). A similarly heightened susceptibility upon suppression of PptT was not seen with 19 other anti-infective agents (Fig. 3D and Fig. S9).

Fig. 3. Functional relevance of PptT as the target for the antimycobacterial activity of 8918.

(A) Resistance of pptT mutant Mtb to 8918. Inhibition of growth of wild-type Mtb by 8918 but not of the pptT mutant W170S or wild-type Mtb expressing the pptT W170S mutant. Means ± SD of triplicates in 1 experiment representative of 5. (B) Increased susceptibility of Mtb to growth inhibition by 8918 upon knockdown of PptT in 4 different strains. The degree of sensitization to 8918 correlates with the extent of the knockdown. Means ± SEM of at least 12 data points from 4 independent experiments. (C) Complementation with atc. Means ± SEM of at least 5 data points from 2 independent experiments. (D) Knockdown of PptT does not affect the potency of isoniazid (INH), BTZ043, chlorpromazine (CPZ), or bedaquiline (BDQ). Means ± SEM of at least 5 data points from 2 independent experiments.

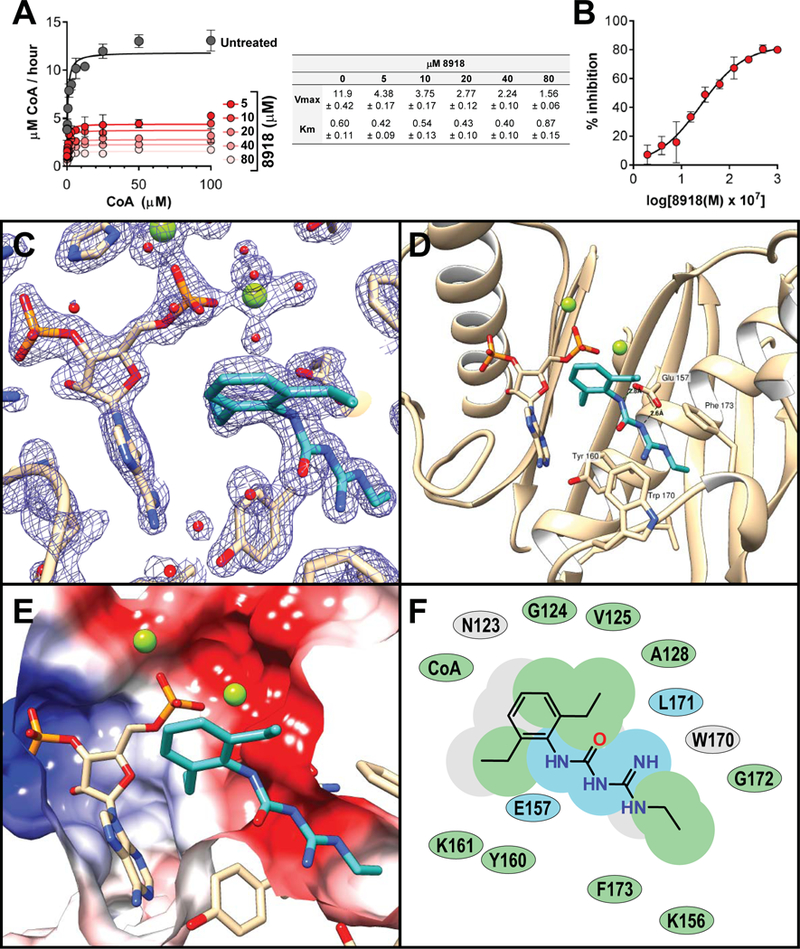

8918 inhibits purified PptT and binds the Ppt pocket in the active site

To learn if 8918 can in fact inhibit PptT and if so by what mechanism, we purified recombinant Mtb PptT and followed its activity by its ability to 4’-phosphopantetheinylate and thereby activate a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase that generates a colored product in the presence of ATP and L-glutamine (21, 22). Kinetic analysis of purified PptT showed an apparent Km for CoA that rose only slightly with increasing concentrations of 8918, while the apparent Vmax declined (Fig. 4A). Although 8918 inhibited PptT with an IC50 of 2.5 μM (Fig. 4B), inhibition plateaued below 90% (Fig. 4A, B). Thus, inhibition of PptT by 8918 was non-competitive and partial (Fig. S10A). The kinetics were unaffected by preincubating PptT with 8918 (Fig. S10B). The km (with respect to CoA) of the resistant mutant PptT (W170S) was similar to WT, although the Kcat and Kcat/Km were reduced compared to WT enzyme (Kcat of 30 hr−1 vs 119 hr−1; Kcat/Km of 53 μM−1hr−1 vs 198 μM−1hr−1) (Fig. S10C, D). Compound 8918 had no effect on the enzyme used in the second stage of the PptT assay (Fig. S10E).

Fig. 4. Inhibition of PptT through binding of 8918 to the Ppt channel in the active site.

(A, B) Impact of 8918 on activity of purified recombinant PptT. (A) Vmax for recombinant PptT in the absence of 8918 (gray) or with 8918 at 5, 10, 20, 40 or 80 μM (shown in decreasing intensities of red). Chart displays Vmax and Km ± the standard error as a function of 8918 concentration in μM. (B) Inhibition of PptT by 8918. IC50 was 2.5 μM, with maximum inhibition of 82%. (C-F) Structure of PptT with 8918 and adenosine 3’,5’-bisphosphate (PAP) moiety of CoA. (C) Simulated annealing composite omit electron density map (contoured at 2σ) of the PptT hydrophobic pocket showing protein residues in the active site with 8918 and PAP. (D) Active site of PptT with residues forming the Ppt binding pocket depicted with beige carbons. 8918 forms van der Waals interactions with Tyr160, Phe173 and Trp170. Glu157 is oriented towards the hydrophobic pocket and hydrogen bonds with 8918. Mg ions are depicted as green spheres. (E) Slice through the molecular surface of the active site of PptT colored according to the electrostatic potential (+/− 10 kT/e). (F) 2D interaction map indicating 8918’s interactions with PptT. Green shading represents hydrophobic regions, blue shading represents hydrogen bond interactions and grey shading represents accessible surface area.

To understand inhibition of PptT by 8918 at the atomic level, we crystallized Mtb PptT in the presence of 8918 and refined the structure to 1.76 Å resolution (Table S4) (PDB 6CT5). There were two copies of the enzyme in the crystal’s asymmetric unit (Fig. S11), each monomer of which bound both 8918 and the adenosine 3’,5’-bisphosphate (phosphoadenosine phosphate, PAP) portion of CoA (Fig. 4C–F), which must have come from E. coli during preparation of recombinant PptT (10). Clear electron density for the inhibitor (Fig. 4C) was located in a deep hydrophobic pocket within the PptT active site (Fig. 4D–E), where the Ppt arm of CoA resides in PptT CoA structures. The binding pocket is formed by residues Lys156, Tyr160, Leu171 and Phe173 and capped by Trp170 (Fig. 4D), the residue whose mutation conferred high-level resistance to 8918. Trp 170 is highly conserved among Mycobacteria but not in most other species (Fig. S12). Glu157, the catalytic base, is oriented towards the hydrophobic pocket (Fig. 4D), similar to what is observed in one of the CoA bound structures (4QJK). In the observed conformation for Glu157, the enzyme would not be catalytically active. This contrasts with the conformation observed in 4QVH, a second PptT-CoA structure, which likely represents the physiologically active conformation of the enzyme. The carbonyl of Leu 171 forms a H-bond with 8918. Leu 171 forms a similar H-bond with the Ppt arm of CoA in the reported structures of CoA-bound PptT. The structure helps explain why proguanil and lidamidine are weaker inhibitors of PptT than 8918 (Fig. S13). Modeling suggests that proguanil’s terminal isopropyl group does not fit in the deeper portion of the hydrophobic pocket, where it would clash with Tyr 160 (0.46 Å), Leu 171 (0.78 Å), Gly172 (0.78 Å) and Phe 173 (0.43 Å) (Fig. S14A). Similarly, lidamidine’s weaker action against PptT can be rationalized by its loss of van der Waals contacts with groups in the hydrophobic pocket (Fig. S14B).

The presence of 8918 within the Ppt binding pocket, together with the knowledge that PptT copurifies with tightly bound CoA (10) and the visualization of the PAP portion of CoA, suggested that 8918 displaces the Ppt arm of CoA from the Ppt pocket. The lack of electron density for the Ppt portion of CoA is likely explained by it becoming disordered in the active site. Indeed, after incubating excess 8918 with purified PptT and denaturing the enzyme, we recovered intact CoA, not PAP (Fig. S15). The same was true when we extracted PptT-8918 co-crystals (Fig. S16). Moreover, 8918 does not require catalytic turnover of CoA in order to bind PptT, because 8918 inhibited the single turnover that the purified enzyme carried out using only the CoA with which it co-purified (Fig. S17). Thus 8918 does not displace CoA from PptT, but does displace the Ppt arm of CoA from its binding pocket, rather than occupying a pocket that is vacant as a result of prior cleavage of Ppt from CoA to generate PAP. Displacement of CoA’s Ppt arm from its ideal position by 8918 decreases but does not abolish PptT’s catalytic activity. This likely explains why inhibition by 8918 is non-competitive and incomplete.

Loss of function of Rv2795c confers resistance to 8918

Concentrations of 8918 that afforded only partial inhibition of PptT were extensively mycobactericidal. This led us to hypothesize that an endogenous inhibitor or antagonist of PptT may augment the action of 8918.

The hypothetical protein encoded by rv2795c is predicted to be a potential phosphohydrolase (Fig. S18). It is rare for mutations in the coding sequence of an enzyme to increase its function, yet many different mutations in Rv2795c produced the same resistance phenotype. Thus it seemed likely that resistance arose through loss of function (LOF). The point mutations in rv2795c that conferred resistance were indeed LOF because knockout of rv2795c produced the same phenotype: the Δrv2795c strain grew normally, yet was highly and selectively resistant to 8918 (Fig. 5A). Expression of WT rv2795c in the Δrv2795c strain fully restored sensitivity to 8918, while complementation of the knock out with the H246N mutant did not (Fig. 5A). Finally, the H246N point mutation in rv2795c did not affect the level of pptT transcripts (Fig. S19). The resistance of Mtb with a LOF of rv2795c was also manifest in primary mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, where 8918 killed WT Mtb but not the rv2795c knockout (Fig. S20). LOF of a non-essential protein can impart resistance to a bactericidal agent if the WT protein augments accumulation of the antibacterial agent in the cell or converts it from a pro-drug form to its active form. However, when 8918 was tracked as an analyte in the study of its impact on Mtb’s metabolome, we found that 8918 accumulated to a comparable extent and in unmodified form in WT Mtb and in an Mtb clone whose resistance to 8918 was associated with mutation in rv2795c (Fig. S21). Thus, there must be a previously undescribed mechanism of resistance arising through LOF. We turned next to biochemical studies on recombinant Rv2795c.

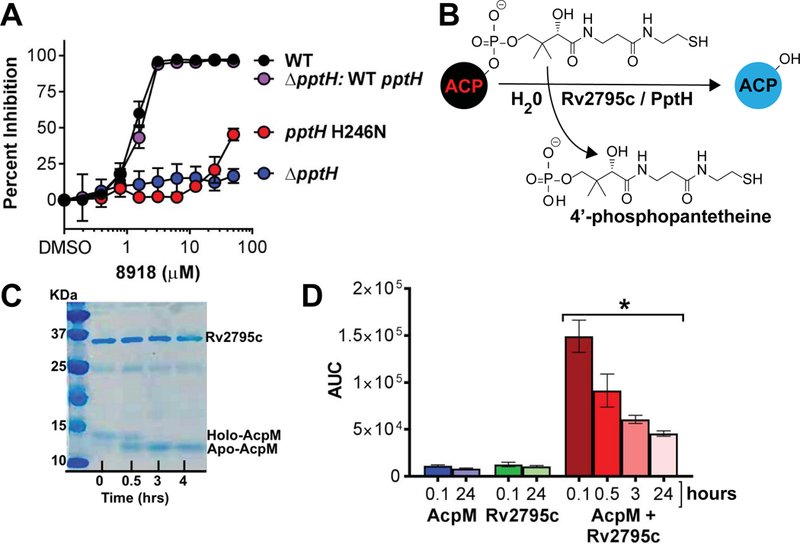

Fig. 5. Resistance to 8918 from LOF mutations in Rv2795c; identification of Rv2795c as a PptH.

(A) Resistance to 8918 in the rv2795c mutant H246N and rv2795c knock out and restoration of sensitivity with complementation of the knockout with the wild-type allele to a level matching that of wild-type Mtb. Means ± SD of triplicates in 1 experiment representative of 3. (B) Schematic of the reaction carried out in vitro by AcpH’s and detected in (C) and (D) with Rv2795c (PptH), which is not homologous to AcpH’s. (C) Conversion of holo-AcpM to apo-AcpM on incubation with C-terminally truncated Rv2795c for up to 4 hours. The experiment shown is representative of 5. (D) Detection of Ppt during incubation of AcpM alone, Rv2795c alone or the combination over the number of hours indicated. The experiment shown is representative of 3. The asterisk indicates statistically significant differences at all time points from each of the controls by unpaired Student’s t test (p < 0.002 for the 0.1 hour time point). Decreasing recovery of Ppt with time reflects instability of the compound. AUC, area under the curve (ion counts).

Rv2795c is a Ppt hydrolase (PptH)

Pathways have been discovered for the regeneration of modified forms of the coenzymes biotin, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate and thiamine (23). Gamma-proteobacteria such as E. coli encode enzymes that can act in vitro as ACP phosphohydrolases, releasing 4’-Ppt from holo-ACPs (Fig. 5B). However, that in vitro reaction has been described as physiologically implausible (24) and it has been unknown whether the reaction takes place in cells (25). Mtb’s genome encodes no sequence homologs of AcpH. However, we speculated that an enzyme that removes Ppt from ACPs could sensitize Mtb to inhibition of PptT and thereby augment 8918’s anti-mycobacterial effect. This could explain why LOF of Rv2795c conferred resistance.

To test if Rv2795c might be a functional homolog of AcpH, we purified recombinant AcpM, an ACP that is one of PptT’s native substrates in Mtb (12), and recombinant Rv2795c, after deleting the C-terminal 20 amino acids to improve its solubility upon over-expression in E. coli. Truncated recombinant Rv2795c catalyzed the conversion of holo-AcpM to apo-AcpM as visualized by a gel shift (Fig. 5C) and confirmed by peptide mass fingerprinting of the excised bands. No conversion was detectable over the same time period in the absence of Rv2795c.

The conversion of holo- to apo-AcpM was accompanied by release of Ppt (Fig 5D), detected by LC-MS as an increase in an AMRT (accurate-mass, retention time) component with a m/z of 339.074 (M-H-H2O) or 357.0891 (M-H) and an observed mass error of <5 ppm that coeluted with a tetradeuterated standard that we synthesized and spiked into the reaction mixture (Fig. S22). The standard’s own identity was confirmed by proton NMR (Fig. S23A), MS (Fig. S23B) and MS/MS (Fig. S23C). Free Ppt was seen with neither AcpM alone nor PptH alone, but only with their combination. Peak amounts of Ppt were detected at the earliest time point that the reaction could be terminated; changes occurring in free Ppt, perhaps including its cyclization or oxidation, led to time-dependent reduction in signal, precluding stoichiometric quantitation (Fig. 5D). Consistent with the hypothesis that Rv2795c is not a target of 8918, the conversion reaction catalyzed by Rv2795c was unaffected by the presence of 15 μM 8918. Accordingly, we propose that Rv2795c is a Ppt hydrolase (PptH).

DISCUSSION

A central concept of antibiotic research is that small chemical compounds can have specific biological targets and can serve as tools to identify those targets’ functions. In the present study, an inhibitor of one enzyme, PptT, led to discovery of another enzyme, PptH, that is not the inhibitor’s target. Studies throughout the antibiotic era have compiled a list of 7 mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance (2): mutation or post-translational modification of the target that reduces binding of the drug but preserves function of the target, increased expression of the target, modification or increased catabolism of the drug, decreased activation of the prodrug, decreased drug uptake or increased drug export, or expression of a compensatory pathway. The present work adds an eighth mechanism: loss of function in an enzyme that undoes the action targeted by the inhibitor.

Our findings demonstrate that PptT, a long-sought target for anti-mycobacterial drug discovery, can be selectively inhibited by a drug-like compound. Moreover, the action of PptH makes Mtb vulnerable even to partial inhibition of PptT, such that 90% of an Mtb population could be killed by 8918 at concentrations that inhibited recombinant PptT by 37%. Resistance due to coding region mutations in PptT or PptH arose infrequently (3×10−7). It is unlikely that resistance to a PptT inhibitor would arise by upregulation of expression of the operon encoding PptT, as this would upregulate PptH as well, further enhancing the action of the inhibitor. Judging from the impact on Mtb’s synthesis of trehalose mycolates and PDIMs and consistent with the literature (13), inhibition of PptT appears to result in failure to activate other enzymes whose products are critical for Mtb’s cell wall, virulence and survival.

A 24-hour exposure of Mtb to 8918 also led to accumulation of a substrate of CoaBC and depletion of products of CoaBC. Those observations are consistent with inhibition of CoaBC, an essential enzyme (4) that catalyzes the conjugation of cysteine to 4’-phosphopantothenate and decarboxylates the resulting 4-phosphopantothenoylcysteine to form 4’-phosphopantetheine. Further study is needed to determine if CoaD, CoaE and/or CoaBC are inhibited after exposure of Mtb to 8918, and if so, the mechanisms() through which inhibition is mediated (26). However, the primacy of PptT as the functionally critical target of 8918 was evident from the occurrence of preservation-of-function mutations in pptT or LOF mutations pptH in all 12 8918-resistant clones of Mtb and all 12 8918-resistant clones of M. smegmatis we isolated, the conferral of resistance as a dominant phenotype upon expression of the mutant pptT allele, and the marked increase in sensitivity to 8918 upon knockdown of PptT.

The co-crystal structure of the PptT-8918-CoA complex helps explain both the non-competitive mode of inhibition by 8918 and the incompleteness of inhibition. The inhibitor’s amidino-urea moiety occupies the hydrophobic binding pocket that normally accommodates the Ppt arm of CoA, displacing the Ppt from its ideal position for catalysis, but without displacing CoA.

The amidino-urea we identified was active against Mtb in vitro and in Mtb-infected mice, while sparing other microorganisms and mammalian cells. A narrow spectrum agent is highly desirable for treatment of tuberculosis, both to avoid dysbiosis with prolonged treatment and to discourage use as monotherapy for other infections, which could hasten the emergence of drug resistance in people with undiagnosed tuberculosis.

In 1967, Vagelos and Larrabee partially purified an activity from E. coli that cleaved Ppt from an ACP in vitro and called it AcpH (27). In 2005, Thomas and Cronan identified the gene encoding AcpH, as confirmed by the activity of the recombinant protein (24). They speculated that AcpH must not have such an action in vivo, because “the cellular content of AcpH activity is sufficient to hydrolyze all of the cellular ACP in <1 min… the physiologic role of AcpH remains enigmatic” (24). Indeed, the AcpH reaction has not been demonstrated to take place in a cell. Investigation of the basis of resistance to the PptT inhibitor provides evidence that an enzyme functions in an intact cell to remove Ppt from holo-ACPs. Mtb’s Rv2795c bears no homology with bacterial AcpH’s (28, 29); hence a different name seems warranted– PptH. PptH is conserved among mycobacteria, including M. leprae, despite severe genomic reduction in M. leprae, suggesting a crucial function in this genus. The discovery of PptH as an enzyme that functions within Mtb to undo the PptT reaction elevates the enigma from a hypothetical to an imperative for investigating a seemingly self-destructive reaction in CoA metabolism that presumably serves a physiologic role.

Materials and Methods

Full details are in the Supplementary Materials.

High throughput screen and anti-mycobacterial assays

The initial screen was conducted against the auxotrophic Mtb strain mc26220 (ΔpanCDΔlysA) from W. R. Jacobs, Jr, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. All experiments whose results are presented in the figures were performed with Mtb H37Rv.

Antimicrobial spectrum and cytotoxicity assays

Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans were clinical isolates from NewYork Presbyterian Hospital. The Streptomyces species S. coelicolor, S. roseosporus, S. antibioticus and S. albidoflavus were gifts of Sean Brady, Rockefeller University. Mammalian cell cytotoxicity was evaluated by measuring ATP content with the CellTiterGlo luminescence assay (Promega) in HepG2 human hepatocarcinoma cells after 40 hours incubation with test agent.

Treatment of Mtb-infected mice

Mouse treatment procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sanofi. Female BALB/c mice aged 5 to 7 weeks were rested 1 week before infection, inoculated intranasally with 106 H37Rv Mtb, treated by gavage beginning one day later for 4 days per week, and euthanized one day after receiving the 8th dose. Lung homogenates were plated for CFU.

Mutant selection of 8918-resistant Mtb and Mycobacterium smegmatis

Bacteria (108 and 107 cells) were plated on 7H11 agar at 4x and 8x the MIC. Surviving colonies were re-streaked on 7H11 plates containing 0.2% glycerol, 10% OADC, and 12.5 μM 8918 to confirm resistance.

Metabolomics

Mtb was grown to OD580 1 in 7H9. One mL was added to each nylon Durapore 0.22 μm membrane filter. Filters were placed on Middlebrook 7H11 agar supplemented with 0.2% glycerol and 10% OADC, incubated at 37 °C for 1 week to expand the biomass, and transferred to lay atop a reservoir containing 7H9 medium with 0.2% glycerol (no tyloxapol) and varied concentrations of test agent. After 24 or 48 hours at 37 °C, filters were extracted with 40:40:20 methanol:acetonitrile:water in a bead beater. Lysates were mixed with equal volumes of 50% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid for mass spectrometry in positive and negative ion mode (16).

Thin-layer chromatography

Cultures of BCG were incubated with 8918, proguanil or isoniazid for 12 hours, then exposed for 24 hours to 14C acetate or 14C propionate. Lipids were extracted with methanol and chloroform, dried, and subjected to chromatography on silica gels as described (30).

Lipidomics

Cell mats prepared as for metabolomics were placed on reservoirs with test agents for 24 hours, then sequentially extracted with mixtures of chloroform:methanol, evaporated, and resuspended in 70:30 [v/v] hexane:isopropanol, 0.02% formic acid [m/v], ammonium hydroxide 0.01% [m/v] for mass spectrometry (31).

Protein purification

His-tagged PptT, apo-BpsA (Streptomyces lavendulae blue pigment synthetase A), AcpM and Rv2795c (lacking the 20 amino acids after residue 304) were expressed in E. coli BL21 cells (Invitrogen) and purified on a Ni-NTA resin for enzyme assays. For crystallization, PptT was further purified by size exclusion chromatography.

Enzyme assays

PptT’s ability to phosphopantetheinylate apo-BpsA was measured by the ability of the resulting holo-BpsA to convert two molecules of L-glutamine into one molecule of indigoidine, which absorbs light at 590 nm (21, 22). Rv2795c (5 μM) and AcpM (10 μM) were combined along with a synthetic tetradeuterated PptT standard for the indicated times, the mixture centrifuged through a 10,000 molecular weight cut-off filter, and the filtrate analyzed by LC-MS. Alternatively, the reaction mixture was boiled in SDS-PAGE loading dye and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Crystallization of PptT

PptT was incubated with excess 8918 and screened against Hampton research crystallization conditions (32). The most promising condition was optimized by varying the pH and precipitant concentration using vapor diffusion (33). X-ray diffraction data were collected at APS Argonne National Labs. The structure was solved with molecular replacement (34) using reported PptT structures 4QJK (10) and 4QVH (9) as search models.

Construction of PptT knock-down strains

SspB-controlled proteolysis was used to conditionally deplete PptT (18–20). First, pptT was first tagged in situ with a DAS-tag (18–20). The resulting Mtb strain was transformed with 4 plasmids (TetON-1, TetON-2, Tet0N-10, TetON-18), which, upon removal of anhydrotetracyline (atc), produce different levels (TetON-18 > TetON-10 > TetON-2 > TetON-1) of the DAS-recognition protein SspB and thus mediate graded depletion of PptT-DAS.

Chemistry

N-((2,6-Diethylphenyl)carbamoyl)acetamide (compound 8918) was synthesized from 1-ethylguanidine and 2,6-diethylphenyl isocyanate using modifications of published protocols (35, 36). Tetradeuterated Ppt standard (Ppt-d4) was synthesized by condensation of pantothenic acid with tetradeuterated, protected 2-mercaptoethylamine, followed by phosphorylation of the primary alcohol, removal of protecting groups and HPLC purification to >98% as demonstrated by evaporative light scattering, UV and MS. Proton NMR in argon-degassed D2O was consistent with deuteration above 98% and 31P NMR showed a single phosphorus.

Statistical analysis

Groups were compared by ANOVA or Student’s unpaired t test as described in the legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Madhumitha Nandakumar, Tania Lupoli, Thulasi Warrier, David Zhang, David Little, Julia Roberts, Yan Ling, Madeleine Wood, Landys Lopez-Quezada, Xiuju Jiang, Oksana Ocheretina (Weill Cornell Medicine), Mickael Blaise (Aarhus University), Laurent Kremer (Université de Montpellier II), Jamie Bean (Sloan Kettering Institute), Ben Neuenswander (University of Kansas), Sean Brady (Rockefeller University), Veronique Dartois and members of her lab (Rutgers University), Helena Boshoff and Clifton E. Barry, III (NIAID), Baojie Wan and Scott Franzblau (University of Illinois) and Michael Glickman (Sloan Kettering Institute) for contributing advice, reagents or assistance with experiments. We thank Maria Belén Barrio (Sanofi) for collaboration at the outset of screening and Ekkehard Leberer (Sanofi) for alliance management, the Midwest Center for Structural Genomics for contributing LIC vectors. Results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center (SBC) at the Advanced Photon Source. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02–06CH1135. We thank the staff at beamline 19-ID and 23-ID of the APS at Argonne National Labs, the Laboratory of Biological Mass Spectrometry, Texas A&M University (Dr. Doyong Kim) for assisting with the LC-MS/MS analysis of CoA bound to PptT, the Integrated Metabolomics Analysis Core (IMAC), Texas A&M University (Dr. Cory Klemashevich) for assisting with the LC-MS/MS analysis of the dissolved PptT 8918 cocrystals and Andres Silva (Texas A&M) for assistance with equilibrium dialysis studies.

Funding: This work was funded by the Tri-Institutional TB Research Unit grant U19AI-111143 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) (CN), the Abby and Howard P. Milstein Program in Chemical Biology and Translational Medicine (CN), grant A-0015 from the Welch Foundation (JS), TB Structural Genomics grant P01AI095208 from NIAID (JS) and a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (DS). The Organic Synthesis Core is partially supported by NCI Core Grant P30 CA008748. The Weill Cornell Department of Microbiology & Immunology is supported by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests. LG, IB, SL, LF, CC, E. Bacqué and CR were employees of Sanofi, Inc. The authors declare no other competing interests. No patent on 8918 has been filed. CFN declares non-competing service on the scientific advisory boards of the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, the Board of Governors of the Tres Cantos Open Lab Foundation, the Pfizer Centers for Therapeutic Innovation National Therapeutic Area Panel and Leap Therapeutics.

Data and materials availability. All data to support the conclusions of this manuscript are included in the main text, supplementary materials and Protein Data Base (PDB 6CT5) (47). All materials are available on request, including chemical compounds as supplies permit, subject to a standard MTA. Chemical syntheses are fully detailed in the supplementary material.

References and Notes:

- 1.Walsh C, Molecular mechanisms that confer antibacterial drug resistance. Nature 406, 775–781 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan C, Kunkel Lecture: Fundamental immunodeficiency and its correction. J Exp Med 214, 2175–2191 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukheja P et al. , A novel small-molecule inhibitor of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis demethylmenaquinone methyltransferase MenG is bactericidal to both growing and nutritionally deprived persister cells. mBio 8, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans JC et al. , Validation of CoaBC as a bactericidal target in the coenzyme A pathway of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Infect Dis 2, 958–968 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moolman WJ, de Villiers M, Strauss E, Recent advances in targeting coenzyme A biosynthesis and utilization for antimicrobial drug development. Biochem Soc Trans 42, 1080–1086 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saliba KJ, Spry C, Exploiting the coenzyme A biosynthesis pathway for the identification of new antimalarial agents: the case for pantothenamides. Biochem Soc Trans 42, 1087–1093 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spry C, Kirk K, Saliba KJ, Coenzyme A biosynthesis: an antimicrobial drug target. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32, 56–106 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gokulan K, Aggarwal A, Shipman L, Besra GS, Sacchettini JC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis acyl carrier protein synthase adopts two different pH-dependent structural conformations. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 657–669 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung J et al. , Crystal structure of the essential Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphopantetheinyl transferase PptT, solved as a fusion protein with maltose binding protein. J Struct Biol 188, 274–278 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickery CR et al. , Structure, biochemistry, and inhibition of essential 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferases from two species of Mycobacteria. ACS Chem Biol 9, 1939–1944 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan PJ, Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 83, 91–97 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimhony O et al. , AcpM, the meromycolate extension acyl carrier protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is activated by the 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase PptT, a potential target of the multistep mycolic acid biosynthesis. Biochemistry 54, 2360–2371 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leblanc C et al. , 4’-Phosphopantetheinyl transferase PptT, a new drug target required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth and persistence in vivo. PLoS Pathog 8, e1003097 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrahams GL et al. , Pathway-selective sensitization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for target-based whole-cell screening. Chem Biol 19, 844–854 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Z et al. , Reaction intermediate analogues as bisubstrate inhibitors of pantothenate synthetase. Bioorg Med Chem 22, 1726–1735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandakumar M, Prosser GA, de Carvalho LP, Rhee K, Metabolomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Mol Biol 1285, 105–115 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeJesus MA et al. , Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. mBio 8, e02133-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH et al. , A genetic strategy to identify targets for the development of drugs that prevent bacterial persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 19095–19100 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JH et al. , Protein inactivation in mycobacteria by controlled proteolysis and its application to deplete the beta subunit of RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res 39, 2210–2220 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnappinger D, O’Brien KM, Ehrt S, Construction of conditional knockdown mutants in mycobacteria. Methods Mol Biol 1285, 151–175 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown AS, Robins KJ, Ackerley DF, A sensitive single-enzyme assay system using the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase BpsA for measurement of L-glutamine in biological samples. Sci Rep 7, 41745 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen JG, Copp JN, Ackerley DF, Rapid and flexible biochemical assays for evaluating 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase activity. Biochem J 436, 709–717 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E, Hanson AD, Metabolite damage and its repair or pre-emption. Nat Chem Biol 9, 72–80 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas J, Cronan JE, The enigmatic acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase of Escherichia coli: genetic and enzymological characterization. J Biol Chem 280, 34675–34683 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas J, Rigden DJ, Cronan JE, Acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase (AcpH) of Escherichia coli is a non-canonical member of the HD phosphatase/phosphodiesterase family. Biochemistry 46, 129–136 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abiko Y, Investigations on pantothenic acid and its related compounds. X. Biochemical studies. 5. Purification and substrate specificity of phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase from rat liver. J Biochem 61, 300–308 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vagelos PR, Larrabes AR, protein Acyl carrier IX. Acyl carrier protein hydrolase. J Biol Chem 242, 1776–1781 (1967). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosa NM, Pham KM, Burkart MD, Chemoenzymatic exchange of phosphopantetheine on protein and peptide. Chem Sci 5, 1179–1186 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murugan E, Kong R, Sun H, Rao F, Liang ZX, Expression, purification and characterization of the acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Expr Purif 71, 132–138 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W et al. , Novel insights into the mechanism of inhibition of MmpL3, a target of multiple pharmacophores in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 6413–6423 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Layre E et al. , A comparative lipidomics platform for chemotaxonomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem Biol 18, 1537–1549 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jancarik J, Kim S-H, Sparse matrix sampling: a screening method for crystallization of proteins. J. Appl. Cryst. 24, 409–411 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng B, Tice JD, Roach LS, Ismagilov RF, A droplet-based, composite PDMS/glass capillary microfluidic system for evaluating protein crystallization conditions by microbatch and vapor-diffusion methods with on-chip X-ray diffraction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 43, 2508–2511 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunkoczi G et al. , Phaser.MRage: automated molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69, 2276–2286 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muzi S, Abdul-Rahman S, Novel compounds, specifically aromatic and heteroaromatic ureas and thioureas, useful against parasites and especially against coccidiosis. Patent WO 2001030749 A1, assignee: New Pharma Research Sweden AB, Sweden. May 3, 2001

- 36.Zhang Q et al. , Unambiguous synthesis and prophylactic antimalarial activities of imidazolidinedione derivatives. J Med Chem 48, 6472–6481 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gold B et al. , Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug sensitizes Mycobacterium tuberculosis to endogenous and exogenous antimicrobials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 16004–16011 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gowda H et al. , Interactive XCMS Online: simplifying advanced metabolomic data processing and subsequent statistical analyses. Anal Chem 86, 6931–6939 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patti GJ et al. , A view from above: cloud plots to visualize global metabolomic data. Anal Chem 85, 798–804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinehart D et al. , Metabolomic data streaming for biology-dependent data acquisition. Nat Biotechnol 32, 524–527 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitely C, Enzyme kinetics: Partial and complete non-competitive inhibition. Biochem and Mol Bio Educ 27, 15–18 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolattukudy PE, Fernandes ND, Azad AK, Fitzmaurice AM, Sirakova TD, Biochemistry and molecular genetics of cell-wall lipid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol 24, 263–270 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y, I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc 5, 725–738 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J et al. , The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods 12, 7–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 40 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold B et al. , Novel cephalosporins selectively active on nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Chem 59, 6027–6044 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.PDB 6CT5 doi: 10.2210/pdb6CT5/pdb

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.