Abstract

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are highly comorbid among people living with HIV (PLHIV), but few instruments have been validated for use in sub-Saharan Africa. The objective of this study was to determine the reliability and validity of the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL) in a population-based sample of PLHIV in rural Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a scale validation sub-study of PLHIV nested within an ongoing population-based sample of all residents living in Nyakabare Parish, Mbarara District, Uganda. All participants identified as HIV-positive by self-report were administered the 25-item HSCL. We performed parallel analysis on the scale items and estimated internal consistency of the identified sub-scales using ordinal alpha. To assess construct validity we compared the sub-scales to related constructs, including subjective well being (happiness), food insecurity, and health status.

Results

Of 1,814 eligible adults in the population, 158 (8.7%) self-reported being HIV positive. The mean age was 41 years, and 68% were women. Mean HSCL-25 scores were higher among women compared with men (1.71 vs. 1.44; t=3.6, P<0.001). Parallel analysis revealed a three-factor structure that explained 83% of the variance: depression (7 items), anxiety (5 items), and somatic symptoms (7 items). The ordinal alpha statistics for the sub-scales ranged from 0.83–0.91. Depending on the sub-scale, between 27–41% of the sample met criteria for caseness. Strong evidence of construct validity was shown in the estimated correlations between sub-scale scores and happiness, food insecurity, and self-reported overall health.

Conclusions

The HSCL-25 is a reliable and valid measure of mental health among PLHIV in rural Uganda. In cultural contexts where somatic complaints are commonly elicited when screening for symptoms of depression, it may be undesirable to exclude somatic items from depression symptom checklists administered to PLHIV.

Keywords: HIV, depression, anxiety, screening, case-finding, Uganda, sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Depression, which is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide [1], is highly prevalent among people living with HIV (PLHIV) [2,3]. In studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, nearly one in five PLHIV have been found to have major depressive disorder and nearly one in three PLHIV have clinically significant symptoms of depression [4]. These statistics highlight an important public health problem because depression is associated with reduced HIV treatment adherence and adverse health outcomes among PLHIV, such as HIV transmission risk behavior, poorer physical functioning, and hazardous alcohol use [5–8]. In addition, the presence of anxiety symptoms among PLHIV has also been shown to compromise HIV-related outcomes, although less is known in this regard [9].

Identifying and treating depression among PLHIV not only improves access to care and initiation of treatment but also improves treatment adherence and prevents disease progression [5,6,10]. Accordingly, there has been considerable interest in the use and application of depression screening tools in care settings where specialist psychiatric care is unavailable [11]. Since both depression and HIV present with similar somatic or physical symptoms, screening for depression among PLHIV can be a difficult undertaking in population-based studies, especially in sub-Saharan Africa [12,13]. Moreover, there is need to consider cultural differences when using depression scales developed in Western populations to screen for depression in African populations [11,14]. Overall, the lack of validated screening tools complicates research focusing on mental health and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [11].

There are few published studies on the validation of screening instruments for detection of both depression and anxiety among PLHIV. In a recently published systematic review of scale validation studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa [4], the most frequently studied depression screening scales were the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). Few studies compared the reliability and/or validity of different depression screening scales; Akena et al. [15] was a notable example in comparing the CES-D and PHQ-9 to the Kessler-10. Several studies have identified a somatic factor, suggesting the importance of careful symptom assessment among PLHIV in the setting of depression and/or anxiety. Depending on illness stage and treatment status, PLHIV may experience somatic symptoms such as fatigue, disturbed sleep, and weight loss that could potentially overlap with the manifestations of depressive disorders [16]. Among studies that examined multi-factor scales, such as the Hopkins Symptom Checklist for Depression, most focused solely on the depression subscales and typically excluded anxiety subscales from consideration. One exception is the study conducted by Kaaya and colleagues [17], who validated a depression and anxiety screening scale among pregnant women in Tanzania. To address this gap in the literature, we examined the reliability and validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist for Depression (HSCL), a 25-item scale that assesses symptoms of both depression and anxiety, in a population-based sample of PLHIV in rural Uganda.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

We obtained feedback on the design of our study from a community advisory board, comprised of eight community leaders (four men and four women), including the district community development officer and a person living with HIV volunteering as a counselor at the local HIV clinic. Ethical approval for all study procedures was obtained from the Partners Human Research Committee, Massachusetts General Hospital; and the Institutional Review Committee, Mbarara University of Science and Technology. Consistent with national guidelines, we received clearance for the study from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and from the Research Secretariat in the Office of the President.

Study Population and Design

The study was conducted in Nyakabare Parish located in Mbarara District, located approximately 275 kilometers southwest of Kampala, the capital city of Uganda. The local population largely depends on subsistence agriculture for income and consumption, and both food and water insecurity are common [18,19]. We used an iterative process, involving conversations with local officials and field investigations, to select prospective study sites. We selected Nyakabare Parish because of its tractable size, both in terms of population and in terms of geographic area, and because the village leadership supported our study’s presence.

Approximately three months prior to survey administration, we conducted a population census within the parish and enumerated all adults aged 18 years and older, as well as emancipated minors (16–18 years). We excluded persons younger than 18 years of age who were not emancipated minors and adults who did not consider Nyakabare their primary place of residence. We also excluded adults who could not communicate effectively or efficiently with research staff, e.g., due to deafness, mutism, or aphasia; and adults with psychosis, neurological damage, acute intoxication, or an intelligence quotient less than 70 (all of which were determined in the field by non-clinical research staff in consultation with a supervisor).

A research assistant who spoke the local language (Runyankore) approached each potentially eligible study participant at their home or (less frequently and only by request) place of work. The research assistant described the study in detail to each person who expressed potential interest in participation. Written informed consent to participate was obtained. Study participants who were not literate were permitted to indicate consent with a thumbprint. Participants were interviewed on a one-on-one basis in a private area, out of earshot from other persons.

Survey Instrument

The survey was programmed into laptop computers for administration in the field, using the Computer Assisted Survey Information Collection (CASIC) Builder™ software program (West Portal Software Corporation, San Francisco, Calif.). Survey questions were first written in English, translated into Runyankore, and then back translated into English to verify the fidelity of the translated text. The translation and back-translation was an iterative process involving in-depth consultation and pilot testing with 18 key informants.

All study participants were asked to report their HIV serostatus, with the following response options: HIV-positive, HIV-negative, unknown, or refused. Given that it is rare for persons to identify as HIV-positive when they are actually seronegative [20], study participants were categorized as HIV-positive if they indicated as such on the survey. All other participants were categorized as having unknown serostatus. The analyses reported in this manuscript focus specifically on the sample of study participants who identified themselves as HIV-positive.

The 25-item HSCL was originally derived from the 90-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) and has traditionally been administered as a 15-item subscale measuring symptoms of depression and a 10-item subscale measuring symptoms of anxiety [21]. Following the scale development study conducted by Bolton and Ndogoni [22] in rural Uganda, we modified the depression subscale by adding a new item (“don’t care what happens to your health”) and deleting one item (“feeling trapped”). Participants rated the frequency of each symptom in the last seven days on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (4). The total severity score is then calculated as the mean of the items (range, 1–4), with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. In addition to the survey procedures above, two experienced Ugandan psychiatrists scrutinized the translation to ensure that it preserved concepts and connotations beyond simple semantic equivalence.

We also measured several related constructs, including subjective well-being (happiness), food insecurity, and self-reported overall health. Subjective well-being has a well known inverse correlation with psychological distress [23,24]. To measure subjective wellbeing, we used a one-item happiness scale: “Considering everything together, how would you say things are in your life? Would you say that you are very happy, fairly happy, or not happy?” In many settings in sub-Saharan Africa, food insecurity is one of the most predominant forms of uncertainty experienced in daily living and has a well known positive correlation with psychological distress [25,26]. To measure food insecurity, we used the 3-item Household Hunger Scale, an abbreviated form of the 9-item Household Food Insecurity Access Scale, which has been validated in this population [18,27]. Finally, to measure self-reported overall health, we used a one-item scale [28,29]: “How is your health in general? Is it very good, good, bad, or very bad?”

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/MP software (version 13.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex.) and R (version 3.3.2, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We used parallel analysis to inform our decision about the number of factors to retain [30–32]. We calculated ordinal alphas to assess the internal consistency of the identified factors [33]. We examined item-test correlations, and then re-calculated the ordinal alphas after sequentially deleting each of the items in turn.

The subscale scores were calculated by averaging across the subscale items. As with many large-scale epidemiological studies, we did not have access to a gold standard criterion of mental health (e.g., clinical psychiatric assessments for all members of the population) to assess criterion-related validity. Therefore as a preliminary step to identify caseness for depression and anxiety, we used the conventional cutoff of >1.75 that has been used previously [21,34–36]. Caseness is a binary variable that indicates a positive screen for depression and/or anxiety, equal to 1 if the subscale score exceeds the cutoff and 0 otherwise. In addition, we relied upon several different assessments of construct validity by correlating the subscales with the previously described variables theorized to be associated with mental health status in this context: subjective well-being (happiness), food insecurity, and self-reported overall health. To estimate correlations we computed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, with confidence intervals calculated using Fisher’s z transform [37,38]. Test statistics from two-sample t-tests were converted to point-biserial correlation coefficients to facilitate comparisons with the Spearman rank correlation coefficients.

RESULTS

Summary Statistics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. Of the 1,814 eligible adults in the population, 158 reported being HIV positive (8.7%). Mean participant age was 41 years (standard deviation [SD], 10.7), 68% were women, and 54% were married or cohabiting. Study participants were evenly distributed among the 8 villages of the parish, with between 17–22 PLHIV per village. The mean HSCL-25 score was 1.6 (SD, 0.45) and ranged from 1 to 2.8, with mean scores higher among women compared with men (1.71 vs. 1.44; t=3.6, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Summary statistics (N=154)

| Mean (range) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 52 (33%) |

| Women | 106 (67%) |

| Age, years | 41 (17–70) |

| Formal education | |

| None | 27 (17%) |

| Some primary (P1ȓP6) | 67 (42%) |

| Completed primary (P7ȓP8) | 40 (25%) |

| More than primary | 24 (15%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabitating | 86 (54%) |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 60 (38%) |

| Single | 11 (7%) |

Factor Structure

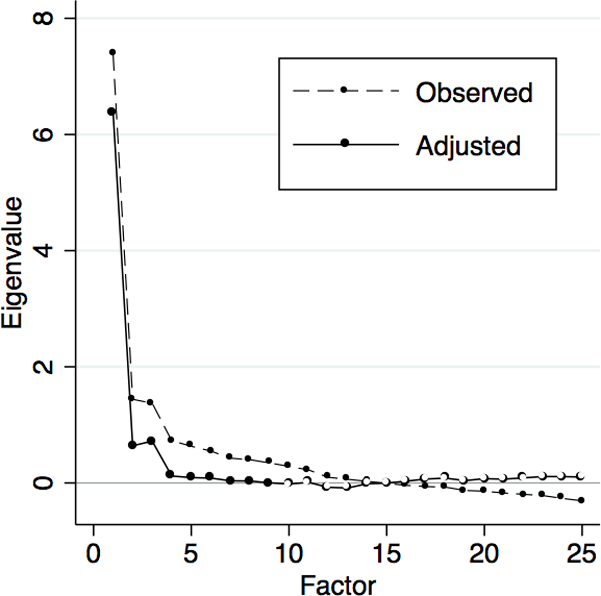

Exploratory factor analysis of the 25-item HSCL revealed a dominant factor with an eigenvalue of 7.4 that alone explained 60% of the variance. There were two additional factors both with eigenvalues of 1.4 that explained another 12% and 11% of the variance. Visual examination of the scree confirmed this three-factor structure (Figure 1). The adjusted eigenvalue was largest for factor 1, followed by steep declines in the adjusted eigenvalues for factors 2 and 3; the remaining adjusted eigenvalues were negligible. Oblique promax rotation yielded a 3-factor structure solution with a pattern of factor loadings that was easiest to interpret. Factor 1 consisted of 7 items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.49–0.76, that were related to depressed mood and negative affect; we labeled this factor the “depression subscale” (Table 2). Factor 2 consisted of 5 items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.46–0.84 that were related to agitation or anxiety; we labeled this factor the “anxiety subscale.” Factor 3 consisted of 7 items, with factor loadings ranging from 0.42–0.68 that were related to somatic symptoms; we labeled this factor the “somatic symptoms subscale.” The remaining 6 items did not load substantively on any of these identified factors. Correlations between these three factors ranged from 0.4–0.5.

Figure 1. Scree.

The graph shows the observed vs. adjusted eigenvalues of the identified factors, in declining order of magnitude. As is shown in the figure, the adjusted eigenvalue was largest for factor 1, followed by steep declines in the adjusted eigenvalues for factors 2 and 3; the remaining adjusted eigenvalues were negligible.

Table 2.

Factor structure

| Factor 1 (depression) | Factor 2 (anxiety) | Factor 3 (somatic symptoms) |

|---|---|---|

| Crying easily | Felt suddenly scared | Felt weak |

| Hopeless about future | Felt fearful | No desire for sex |

| Felt unhappy | Felt nervousness | Poor appetite |

| Felt without friends | Felt terror or panic | Faint, dizzy or weak |

| Everything was an effort | Felt difficult to settle | Heart beat so fast |

| Felt useless | Trembling | |

| Felt tense | Headaches |

Reliability

The 7-item depression subscale had an ordinal alpha of 0.90. Mean values on this subscale ranged from 1 to 3.7, with a sample mean of 1.51 (SD, 0.58); higher scores indicate greater depression symptom severity. Approximately one-quarter of the sample (42 [27%]) met criteria for caseness on this scale. The 5-item anxiety subscale had an ordinal alpha of 0.91, with values ranging from 1 to 3.6 (mean, 1.45; SD, 0.60); higher scores indicate greater anxiety symptom severity. A similar number of study participants (44 [28%]) met criteria for caseness on the anxiety subscale. The 7-item somatic symptoms subscale had an ordinal alpha of 0.83. Values on the somatic symptoms subscale ranged from 1 to 3.9, with a mean of 1.81 (SD, 0.62). A larger proportion of the sample (64 [41%]) met criteria for caseness on the somatic symptoms subscale. Of the participants who met criteria for caseness on the somatic symptoms subscale, only 26 (41%) also met criteria for caseness on the depression subscale; similarly, of the participants who met criteria for caseness on the depression subscale, 16 (38%) did not also meet criteria for caseness on the somatic symptoms subscale. More than one-half of the sample (89 [56%]) met criteria for caseness on at least one subscale, while only 20 (13%) met criteria for caseness on all three subscales.

Validity

The 7-item depression subscale identified in this study had a statistically significant positive correlation with the modified 15-item depression subscale developed by Bolton & Ngodoni [22] (r=0.87; 95% CI, 0.83–0.91). When participants were categorized according to caseness on both subscales, most participants were consistently classified on both subscales (125 [81%]). Twenty-one participants (14%) were classified as having probable depression on the Bolton & Ngodoni subscale but not on the new 7-item depression subscale, while only 8 participants (5%) were classified as having probable depression on the new subscale but not on the Bolton & Ngodoni subscale.

There was a statistically significant inverse correlation between happiness and both the depression (r=−0.43; 95% CI, −0.55 to −0.30) and anxiety (r=−0.32; 95% CI, −0.45 to −0.17) subscales. Cuzick’s test confirmed a trend of increasing symptom scores across the different levels of happiness (P<0.001 for both depression and anxiety). Similarly, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between food insecurity and both the depression (r=0.27; 95% CI, 0.12–0.41) and anxiety (r=0.32; 95% CI, 0.17–0.45) subscales. The somatic symptoms subscale also had a statistically significant inverse correlation with happiness (r=−0.21; 95% CI, −0.35 to −0.05) and a statistically significant positive correlation with food insecurity (r=0.22; 95% CI, 0.07–0.37), although these correlation coefficients were slightly smaller in magnitude. The somatic symptoms subscale had a stronger and statistically significant inverse correlation with self-reported overall health (r=−0.40; 95% CI, −0.53 to −0.26). Cuzick’s test confirmed a trend of increasing somatic symptom scores across the different levels of self-reported overall health (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The findings indicate that the HSCL-25 is a reliable and valid measure of depression and anxiety among PLHIV in rural Uganda. Parallel analysis revealed a three-factor solution with three related, but distinct, constructs: depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms. The three sub-scales were internally consistent. The depression and anxiety sub-scales correlated strongly with happiness and food insecurity while the somatic symptoms sub-scale was more strongly correlated with overall self-reported health, thus providing evidence of construct validity.

The depression and anxiety sub-scales showed slightly higher reliability compared with the somatic symptoms sub-scale. The scale reliability coefficients demonstrated by the depression and anxiety sub-scales are similar in magnitude to those estimated in a previous study of women recruited from an antenatal clinic in Tanzania [39]. Nearly one-third of participants met criteria for caseness on the depression subscale, which is broadly in agreement with findings from other parts of Uganda and from other countries in sub-Saharan Africa [40–44].

The three-factor structure is similar to what has been found in a related study of PLHIV in Tanzania [17]. The high rate of caseness on the somatic symptoms sub-scale can potentially be explained by the unique features of the sample (i.e., all were HIV positive). Additionally, across different cultures in sub Saharan Africa, including Uganda, people tend to express their feelings using physical symptoms because they perceive them to be of greater relevance when seeking care [12,13,45–47]. Although previous studies from the U.S. have suggested that there is need to exclude somatic symptoms from depression screening tools for PLHIV [16,48], somatic symptoms are commonly expressed by persons with common mental disorders in most cultures across Uganda. In a previous study of PLHIV in Uganda undergoing treatment for depression, study participants explained depression as an illness of many thoughts and worries that affect physical well-being, hence the presentation of physical symptoms among patients with depression [49]. Therefore, excluding somatic symptoms while assessing for depression among PLHIV may potentially limit the ability to capture symptoms of depression since somatic symptoms have been observed to be one of the principal modes of expressing psychological distress [50,51].

Our findings should be interpreted in view of several limitations. First, HIV serostatus was based on self-report. Although it is unlikely that many participants were misclassified (i.e., it is unlikely that persons would have reported themselves to be HIV-positive when in fact they were HIV-negative) [20], it is possible that there were some persons in the general study population who were HIV-positive but who were either unaware of their seropositivity or who falsely reported themselves to be HIV-negative. Both of these are non-trivial possibilities given that many PLHIV in Uganda have not been tested and are unaware of their seropositivity [52] and also given that HIV remains highly stigmatized in Uganda [53–55]. Nonetheless, our HIV prevalence estimate of 8.7% (based on self-report) is similar to the HIV prevalence estimate of 8.0% for southwest Uganda in the 2011 Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey (based on unlinked anonymous HIV testing) [56]; therefore we anticipate that any potential bias resulting from misclassification would be minimal. Second, we did not have access to a gold standard for the purposes of determining criterion-related validity. Thus, caution should be exercised in reviewing our findings. Studies with population-based data on clinical psychiatric assessments are rare. Future studies validating the HSCL-25 against a gold standard of psychiatric diagnosis among PLHIV should be considered. Third, for the somatic symptoms subscale specifically, we did not have objective measures of disease progression (e.g., CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count) for our assessments of construct validity. We used a measure of self-reported overall health that is generally accepted as a valid measure of health status [28,29]. However, because HIV status was self-reported and testing for CD4 levels was not done, we were not able to definitively conclude that the high rate of somatic symptoms was related to advanced HIV disease.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found that the HSCL-25 is a reliable and valid measure of mental health among PLHIV in rural Uganda. In this population, the prevalence of depression and anxiety are high. Moreover, the experience of depression is a mixed picture of cognitive, affective, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. Excluding somatic symptoms could potentially lead to many undetected cases of depression and, therefore, undertreatment overall. Thus, somatic symptoms should be taken into consideration when assessing for depression among PLHIV in rural Uganda.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Peggy Bartek, Anna Baylor, Kate Bell, Ryan Carroll, Amy Q. McDonough, Nozmo F. B. Mukiibi, Rumbidzai Mushavi, and the HopeNet Study team, for their assistance with data collection, study administration, and infrastructure development; and Roger Hofmann of West Portal Software Corporation (San Francisco, California), for developing and customizing the Computer Assisted Survey Information Collection Builder software program. In addition to the named study authors, HopeNet Study team members who contributed to data collection and/or study administration during all or any part of the study were as follows: Phiona Ahereza, Owen Alleluya, Gwendoline Atuhiere, Patience Ayebare, Augustine Byamugisha, Patrick Gumisiriza, Clare Kamagara, Justus Kananura, Noel Kansiime, Allen Kiconco, Viola Kyokunda, Patrick Lukwago, Moran Mbabazi, Juliet Mercy, Elijah Musinguzi, Sarah Nabachwa, Elizabeth Namara, Immaculate Ninsiima, Mellon Tayebwa, and Specioza Twinamasiko.

Source of Funding: The study was funded by Friends of a Healthy Uganda. The authors additionally acknowledge salary support through U.S. National Institutes of Health D43TW010128 (S.A.), T32MH093310 (C.E.C-V.), and K23MH096620 (A.C.T.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Written informed consent to participate was obtained. Study participants who were not literate were permitted to indicate consent with a thumbprint. Ethical approval for all study procedures was obtained from the Partners Human Research Committee, Massachusetts General Hospital; and the Institutional Review Committee, Mbarara University of Science and Technology. Consistent with national guidelines, we received clearance for the study from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and from the Research Secretariat in the Office of the President.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388(10053):1603–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiser SD, Wolfe WR, Bangsberg DR. The HIV epidemic among individuals with mental illness in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS reports 2004;1(4):186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001;58(8):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai AC. Reliability and validity of depression assessment among persons with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 2014;66(5):503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai AC, Weiser SD, Petersen ML, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR. A marginal structural model to estimate the causal effect of antidepressant medication treatment on viral suppression among homeless and marginally housed persons with HIV. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010;67(12):1282–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Drabkin AS, Meade CS, Hansen NB, Pence BW. Mental health treatment to reduce HIV transmission risk behavior: a positive prevention model. AIDS Behav 2010;14(2):252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adams JL, et al. The effect of antidepressant treatment on HIV and depression outcomes: results from a randomized trial. AIDS 2015;29(15):1975–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seth P, Kidder D, Pals S, et al. Psychosocial functioning and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive persons receiving care and treatment in Kenya, Namibia, and Tanzania. Prev. Sci 2014;15(3):318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nel A, Kagee A. Common mental health problems and antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Care 2011;23(11):1360–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Robinson E, et al. Effects of depression alleviation on ART adherence and HIV clinic attendance in Uganda, and the mediating roles of self-efficacy and motivation. AIDS Behav 2017;216(6):1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagee A, Tsai AC, Lund C, Tomlinson M. Screening for common mental disorders: reasons for caution and a way forward. Int. Health 2013;5(1):11–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherian VI, Peltzer K, Cherian L. The factor-structure of the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) in South Africa. East Afr. Med. J 1998;75(11):654–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okello ES, Ekblad S. Lay concepts of depression among the Baganda of Uganda: a pilot study. Transcult. Psych 2006;43(2):287–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Kruger LM, Gureje O. Manifestations of affective disturbance in sub-Saharan Africa: key themes. J. Affect. Disord 2007;102(1–3):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akena D, Joska J, Obuku EA, Stein DJ. Sensitivity and specificity of clinician administered screening instruments in detecting depression among HIV-positive individuals in Uganda. AIDS Care 2013;25(10):1245–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Somlai A. Assessing persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection using the Beck Depression Inventory: disease processes and other potential confounds. J. Pers. Assess 1995;64(1):86–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaaya SF, Fawzi MC, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2002;106(1):9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Emenyonu N, Senkungu JK, Martin JN, Weiser SD. The social context of food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med 2011;73(12):1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai AC, Kakuhikire B, Mushavi R, et al. Population-based study of intra-household gender differences in water insecurity: reliability and validity of a survey instrument for use in rural Uganda. J. Water Health 2016;14(2):280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Statistical Office and ICF Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010 Calverton: ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod. Probl. Pharmacopsychiatry 1974;7(0):79–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton P, Ndogoni L. Cross-cultural assessment of trauma-related mental illness (Phase II): a report of research conducted by World Vision Uganda and The Johns Hopkins University 2001. http://www.certi.org/publications/policy/ugandafinalreport.htm. Accessed April 23, 2011.

- 23.Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychol. Assess 1993;5(2):164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull 1999;125(2):276–302. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Food insufficiency, depression, and the modifying role of social support: Evidence from a population-based, prospective cohort of pregnant women in peri-urban South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med 2016;151:69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole SM, Tembo G. The effect of food insecurity on mental health: panel evidence from rural Zambia. Soc. Sci. Med 2011;73(7):1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med 2012;74(12):2012–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav 1997;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jylha M What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med 2009;69(3):307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965;30(2):179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glorfeld LW. An improvement on Horn’s parallel analysis methodology for selecting the correct number of factors to retain. Educ. Psychol. Meas 1995;55(3):377–393. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dinno A Implementing Horn’s parallel analysis for principal component analysis and factor analysis. Stata J 2009;9(2):192–298. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Zumbo BD. Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: a conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval 2012;17(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winokur A, Winokur DF, Rickels K, Cox DS. Symptoms of emotional distress in a family planning service: stability over a four-week period. Br. J. Psychiatry 1984;144:395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinton WL, Du N, Chen YC, Tran CG, Newman TB, Lu FG. Screening for major depression in Vietnamese refugees: a validation and comparison of two instruments in a health screening population. J. Gen. Intern. Med 1994;9(4):202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mollica RF, Wyshak G, de Marneffe D, Khuon F, Lavelle J. Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: a screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987;144(4):497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher RA. On the “probable error” of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron 1921;1(4):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seed PT. sg159: Confidence intervals for correlations. Stata Tech. Bull 2001;59(1):27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee B, Kaaya SF, Mbwambo JK, Smith-Fawzi MC, Leshabari MT. Detecting depressive disorder with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 in Tanzania. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2008;54(1):7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaharuza FM, Bunnell R, Moss S, et al. Depression and CD4 cell count among persons with HIV infection in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2006;10(4 Suppl):S105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olley BO, Seedat S, Nei DG, Stein DJ. Predictors of major depression in recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Pat. Care STDs 2004;18(8):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, Girma B, Deribe K. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2008;8:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marwick KF, Kaaya SF. Prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in HIV-positive outpatients in rural Tanzania. AIDS Care 2010;22(4):415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramadhani HO, Thielman NM, Landman KZ, et al. Predictors of incomplete adherence, virologic failure, and antiviral drug resistance among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Clin. Infect. Dis 2007;45(11):1492–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okello ES, Ngo VK, Ryan G, et al. Qualitative study of the influence of antidepressants on the psychological health of patients on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. African J. AIDS Res 2012;11(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okello ES, Neema S. Explanatory models and help-seeking behavior: Pathways to psychiatric care among patients admitted for depression in Mulago hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Qual. Health Res 2007;17(1):14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okello ES. Cultural explanatory models of depression in Uganda Stockholm: Institutionen för Klinisk Neurovetenskap, Karolinska Institutet;2006. 9171408231. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 2000;188(10):662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okello ES, Musisi S. Depression as a clan illness (eByekika): an indigenous model of psychotic depression among the Baganda of Uganda. World Cult. Psych. Res. Rev 2006;1(2):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ndetei DM, Muhangi J. The prevalence and clinical presentation of psychiatric illness in a rural setting in Kenya. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979;135:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaaya SF, Lee B, Mbwambo JK, Smith-Fawzi MC, Leshabari MT. Detecting depressive disorder with a 19-item local instrument in Tanzania. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2008;54(1):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bunnell R, Opio A, Musinguzi J, et al. HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-infected adults in Uganda: results of a nationally representative survey. AIDS 2008;22(5):617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan BT, Weiser SD, Boum Y, et al. Persistent HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda during a period of increasing HIV incidence despite treatment expansion. AIDS 2015;29(1):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan BT, Tsai AC, Siedner MJ. HIV treatment scale-up and HIV-related stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: a longitudinal cross-country analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2015;105(8):1581–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan BT, Tsai AC. HIV stigma trends in the general population during antiretroviral treatment expansion: analysis of 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 2003–2013. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 2016;72(5):558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey 2011 Kampala: Uganda Ministry of Health and Calverton: ICF International; 2012. [Google Scholar]