Abstract

Background:

Thrombolysis is the standard of treatment for acute ischemic stroke, with a time window of up to 4½ h from stroke onset. Despite the long experience with the use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and the adherence to protocols symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (SICH) may occur in around 6% of cases, with high-mortality rate and poor-functional outcomes. Many patients are excluded from thrombolysis on the basis of an evaluation of known risk factors, but there are other less known factors involved.

Objective:

The purpose of this work is to analyze the less known risk factors for SICH after thrombolysis. A search of articles related with this field has been undertaken in PubMed with the keywords (brain hemorrhage, thrombolysis, and acute ischemic stroke). Some risk factors for SICH have emerged such as previous microbleeds on brain magnetic resonance imaging, leukoaraiosis, and previous antiplatelet drug use or statin use. Serum matrix metalloproteinases have emerged as a promising biomarker for better selection of patients, but further research is needed.

Conclusions:

In addition to the already known risk factors considered in the standard protocols, an individualized evaluation of risks is needed to minimize the risk of brain hemorrhage after thrombolysis for ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Acute stroke, brain hemorrhage, thrombolysis complications

INTRODUCTION

Thrombolysis is the first line of treatment in hyperacute ischemic stroke, and eventually followed by mechanical thrombectomy. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) is the only agent approved by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMEA) since 2002 for acute ischemic stroke within 3 h of stroke onset according to the benefits observed in multicenter clinical trials in North America and Europe.[1,2,3] A registry and a protocol was created to monitor the outcomes and safety (ISTR, SITS-MOST/www.acutestroke.org/SM_Protocol/SITS-MOST_final_protocol. pdf). The time window was extended to 4.5 h on light of the benefits observed in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS [III]) trial,[4] with a new registry called Safe implementation of thrombolysis in upper time window monitoring study (SITS-UTMOST).[5]

The major complication of thrombolysis is symptomatic brain hemorrhage in the area of infarction symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (SICH), which happens in around 6.4% of cases in the NINDS trial,[1,2] or higher in the ECASS II trial (8.8%), but SICH can also appear in remote or extraischemic brain regions as well in 1.3%–2% of cases.[2,3] The in-hospital mortality due to SICH after thrombolysis was 52.3% (67/128 cases), independently of treatment.[6] Furthermore, SICH appeared after thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism in two studies, in 1.8% (176/9705) and in 1.9% (6/302) of treated patients, respectively, and with poor outcomes.[7,8] The frequency of BH was low after thrombolysis for AMI, 9 cases out of 1700 patients treated with rt-PA (0.53%).[9]

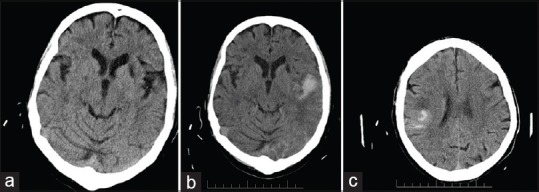

Most postthrombolysis hematomas occur in the area of infarction [Figure 1a and b] because of damaged brain tissue, loss of hemostatic control, and later reperfusion, whereas remote hemorrhages tend to occur in preexisting brain pathologies and/or coagulopathies.[10] Amyloid angiopathy has been associated with remote brain hemorrhages.[11,12]

Figure 1.

(a) Brain computed tomography before thrombolysis. Old infarction in the left basal ganglia. The patient fulfilled the criteria of SITS-MOST for intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. (b) Brain computed tomography, carried out 24 h after thrombolysis with hemorrhage type 2 in the area of infarction in the left posterior MCA (middle cerebral artery), with clinical worsening. (c) Brain computed tomography after thrombolysis small hemorrhagic transformation (HI-2) without clinical worsening

Given the high mortality and poor functional outcome of BH after thrombolysis, many studies have been focused on the predictive factors. Some risk factors are well known, and they are taken into account in the standard protocols by preventing clinicians to administer rt-PA in patients with these factors (noncontrolled hypertension, high elevation of plasma glucose, low platelet count, previous surgery within the 3 months, NIHSS score higher than 25 points, early signs of infarction on brain CT, duration of stroke symptoms longer than 4.5 h, symptoms with unknown onset time, and so on).[13] Despite discarding patients with these factors for thrombolysis SICH can occur.

I have searched articles in PubMed, related with the field of SICH after thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. The key words used were: thrombolysis, brain hemorrhage, and acute ischemic stroke. From the initial 695 articles, only 51 were considered informative enough with regard to risk factors for SICH after thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke.

There is a consensus in several factors such as higher NIHSS score, age, systolic blood pressure, previous antiplatelet treatment, and high glucose levels in the serum in two great registries.[14,15] The Italian registry including 15,949 patients developed a prediction model based on 10 variables that were predictors of BH.[14] The European one with 31,627 patients found 9 predictive variables.[15] However, the protocols are not sacrosanct; alteplase can be administered even in acute stroke with unknown onset time in cases with positive MRI-diffusion-weighted imaging and negative FLAIR imaging.[16]

Preexisting cerebral microbleeds have been considered a risk factor for BH after thrombolysis, and it was confirmed in three meta-analyses from pooled data of medical literature with 2702,[17] 1704,[18] and 2479[19] patients. According to three meta-analyses from 15/11/11 trials with a similar number of treated patients (6967/6912/7194), the presence of leukoaraiosis was associated with an increased risk of SICH and poor outcomes.[20,21,22] Both microbleeds and leukoaraiosis were associated with remote location SICH.[23,24] Extensive leukoaraiosis also increased the risk of remote SICH and poor outcomes in a cohort of 503 patients[25] and in another cohort of 2485 Finnish patients.[26] However, the data of 614 patients from a prospective registry did not show such an association, but leukoaraiosis predicted poor functional outcomes after stroke.[27] Cardioembolic stroke is an independent risk factor for SICH in two far-East countries.[28,29]

From a prospective stroke database, the only predictor of SICH was the change in the level of consciousness, which happened in 108 out of 511 patients and 19 of them had SICH (odds ratio [OR]: 6.62; 1.64–26.7).[30]

The question on whether antiplatelet treatment for prevention of ischemic stroke prior ischemic stroke treated with thrombolysis increases or not the risk of SICH has not been completely elucidated. In two systematic review and meta-analysis, the conclusions were discordant; in the first one with 7 clinical trials and 4376 patients, there was no association between previous antiplatelet treatment and SICH, nor was the functional outcome worse.[31] In the second one with 108,588 patients from 19 studies, there was a positive association between the use of antiplatelet drugs and SICH, but the differences regarding outcomes and mortality were not significant.[32] In the last American heart society/American stroke association (AHS/ASA) guidelines of 2018 for the early management of acute ischemic stroke, the prior use of antiplatelet drugs does not preclude thrombolysis with t-PA, as benefits outweigh the small increased risk of SICH.[13]

With regard to previous ischemic stroke within 3 months before receiving thrombolysis, it was not associated with increased risk of SICH but with increased risk of death, according to the data of a multicenter registry in the USS comprising 36,599 patients treated with thrombolysis.[33] From an European Registry with 13,007 patients included, neither was seen an increased risk of SICH, with no worse outcomes.[34] Prior asymptomatic SICH in the context of ischemic stroke did not increase the risk of SICH after thrombolysis in a retrospective cohort of 640 patients.[35]

Prior statin use has been associated to increased risk of SICH, but it did not have any impact on outcomes according to cases series of 311 and 182 patients treated[36,37] and three European registries totaling 2482 patients.[37,38,39] In another registry of 606 patients, the risk of SICH was not increased (OR: 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.22–1.49)[40] and in a meta-analysis of 11 studies and 6438 patients, the statin use neither increased the risk of SICH nor was associated with more favorable outcomes.[40]

Some MRI-based technique such as diffusion (apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC]),[41] and spin-label MRI after reperfusion (arterial spin labelling [ASL]),[42] may offer some aid in the prediction of SICH postthrombolysis. An ADC ratio (ADC in the affected area/ADC in the normal contralateral area) <0.65 was an independent predictor of hemorrhagic transformation, so was FLAIR hyperintensity.[41] Focal hyperperfusion in the damaged area after reperfusion on ASL in a ratio higher than 1.5 (ipsilateral/contralateral) was also a reliable predictor of hemorrhagic transformation.[42]

The use of the ASPECTS CT-based scale prior thrombolysis is common worldwide to stratify the risk of bleeding after thrombolysis. According to data from the ECASS II trial, the patients with scores ≤7 points were at increased risk of parenchymal brain hemorrhage (Relative risk [RR]: 18.9; 95% CI: 1.6–138) as those with scores of 8–10.[43]

Patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy in hyperacute stroke were not at increased risk of brain hemorrhage as those who did not, according to a systematic review comprising 1287 patients.[44] The off-label use of rt-PA (e.g., age older than 80, previous stroke and diabetes, previous surgery within 3 months prior of stroke onset, prior oral anticoagulation, systemic diseases, intracranial tumors, seizures at onset, and NIHSS score higher than 25 points) did not result in higher rates of SICH or poorer functional outcome than in the on-label group in a retrospective study of 505 patients.[45]

The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants is associated with some trend to bleeding, but the data of an international registry with 1114 patients treated with thrombolysis and 135 treated with SSRI drugs did not show association between the use of SSRI antidepressants and the risk of SICH, mortality, or poorer functional outcome.[46]

An unresolved issue on SICH is the case definition. The criteria of ICH vary across the studies. In the NINDS trial, symptomatic ICH was defined as hemorrhage seen within 36 h of treatment and deemed to be temporally related to neurological decline.[1] The SITS-MOST criteria only considered parenchymal hemorrhages with an increase of at least 4 points in the NIHSS. The ECASS III trial defined symptomatic ICH as evidence of hemorrhage on CT or MRI that was felt to be associated with an increase in NIHSS score of ≥4, and SICH occurred in 2.4% of patients in the extended window of 3–4.5 h.[4] The ECASS II criteria distinguish hemorrhagic infarction from parenchymal hemorrhages [Table 1].[3] In a secondary analysis of ECASS II trial, only parenchymal hematoma type 2 was associated with an increased risk for deterioration at 24 h after stroke onset.[47] Of course, small hemorrhagic transformations do not have clinical implications [Figure 1c]. The variability of criteria used may contribute to the differences found in the different studies and meta-analysis. Thus, the incidence of SICH tends to be higher in clinical trials than in the registries (7.4% vs. 3.5%).[48]

Table 1.

Classification of brain hemorrhages postthrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke, according to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II trial[3]

| ECASS classification of hemorrhagic transformation |

| HI |

| H-1: Small petechiae along margins of infarcted area |

| H-2: Confluent petechiae within the infarcted area; no mass effect |

| PH |

| PH-1: Hematoma less than 30% of infarcted area, with mild mass effect |

| PH-2: Hematoma in more than 30% of infarcted area, with notable mass effect |

HI=Hemorrhagic infarction, PH=Parenchymal hemorrhage

The search of plasmatic biomarkers for better selection of patients for thrombolysis has not yielded yet results useful enough for clinical application. The determination of serum metalloproteinases seems to be promising. A baseline level of metalloproteinase-9 7 900 ng/ml can predict SICH with 85% sensitivity and 79% specificity in accordance with the pooled values of a meta-analysis of 7 studies and 1492 patients, but heterogeneity between studies was significant, with cutoff values ranging from 140 to 900 ng/dl.[49]

Other plasmatic biomarkers have been studied for better prediction, such as F2-isoprostanes, thrombin-activated fibrinolysis inhibitor, plasminogen activation inhibitor, and the calcium-binding protein S100B. To date, there are no current recommendations for using determined plasmatic biomarkers.[50]

The main conclusions drawn by the experience with thrombolysis for acute stroke can be summarized by the secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis from the Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists (9 trials and 6756 patients), with time to treatment and stroke severity being the best predictors of global outcome. Although the sooner the better, within 4–5 h of stroke onset the benefits of thrombolysis outweigh the risks of SICH and death.[51]

In Table 2, the data of the different recent meta-analysis based on predictors of SICH after thrombolysis for acute stroke are given.

Table 2.

Factors predictive of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage and that do not exclude intravenous thrombolysis. Results from meta-analysis and large registries

| Predictor Author | Number of trials and patients | Risk of SICH OR/RR and 95% CI | Unfavourable outcome (death or dependence) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior statin use Meseguer 2012 | 11 studies with 6438 patients | 1.55 (1.23-1.95) | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) NS |

| Leuko-araiosis Lin, 2106 | 11 trials, 6912 patients | 1.89 (1.51-2.37) | Not given |

| Leuko-araiosis, Charidimou 2016 | 11 studies, 7194 patients | 1.55 (1.17-2.06) | 1.61 (1.44-1.79) |

| Leuko-araiosis Kongbunkiat 2017 | 15 studies, 6967 patients | 1.65 (1.26-2.16) | 1.30 (1.19-1.42) |

| Microbleed burden Tsivgoulis 2016 | 9 studies, 2479 patients | 2.36 (1.21-4.61), risk proportional to the burden | Not given |

| Microbleed burden Charidimou 2015 | 8 studies, 1704 patients | 2.87 (1.73-4.79) | Not given |

| Microbleed burden Wang S, 2017 | 11 studies, 2702 patients | 2.14 (1.34-3.42) | 1.58 (1.08-2.31) |

| Recent ischemic stroke Merkler | Several registries with 36,599 patients | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) NS | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) |

| Antiplatelet drug use Luo 2016 | 19 studies with 108,588 patients | 1.70 (1.47-1.97) | 1.46 (1.22-1.75) |

| Antiplatelet drug use Tsivgoulis | 7 trials, 4376 patients | 1.67 (0.75-3.72) NS | 1.01 (0.55-1.86) NS |

| Antiplatelet drug Capellari 2016 | 179 centers, 15,949 patients | 2.23 (1.26-3.94) | Not given |

NS=Not significant, SICH=Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, OR=Odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval, RR=Relative risk

To date, we do not have treatment effective enough to reverse coagulopathy caused by thrombolysis or to prevent hematoma expansion.[52] However, the American Heart Association recommends replacing coagulation factors and platelets with the infusion of cryoprecipitate and platelets because of the alteplase-induced hypofibrinogenemia,[53] but it is only based on empirical data.

CONCLUSIONS

Therefore, despite the better selection of patients for thrombolysis, many SICH will occur, and the decision of treatment will be for long time based on the individual balance of benefits/risks.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous t-PA therapy for ischemic stroke. The NINDS t-PA stroke study group. Stroke. 1997;28:2109–18. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:1245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed N, Hermansson K, Blumki E, Danays T, Nunes AP, Kenton A, et al. The SITS-UTMOST: A registry-based prospective study in Europe investigating the impact of regulatory approval of intravenous actilyse in the extended time window (3–4.5 h) in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2016;1:213–21. doi: 10.1177/2396987316661890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaghi S, Boehme AK, Dibu J, Leon Guerrero CR, Ali S, Martin-Schild S, et al. Treatment and outcome of thrombolysis-related hemorrhage: A multicenter retrospective study. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1451–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee S, Weinberg I, Yeh RW, Chakraborty A, Sardar P, Weinberg MD, et al. Risk factors for intracranial haemorrhage in patients with pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolytic therapy development of the PE-CH score. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:246–51. doi: 10.1160/TH16-07-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanter DS, Mikkola KM, Patel SR, Parker JA, Goldhaber SZ. Thrombolytic therapy for pulmonary embolism. Frequency of intracranial hemorrhage and associated risk factors. Chest. 1997;111:1241–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kase CS, Pessin MS, Zivin JA, del Zoppo GJ, Furlan AJ, Buckley JW, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage after coronary thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator. Am J Med. 1992;92:384–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90268-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trouillas P, von Kummer R. Classification and pathogenesis of cerebral hemorrhages after thrombolysis in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:556–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000196942.84707.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarron MO, Nicoll JA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and thrombolysis-related intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:484–92. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karaszewski B, Houlden H, Smith EE, Markus HS, Charidimou A, Levi C, et al. What causes intracerebral bleeding after thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke? Recent insights into mechanisms and potential biomarkers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1127–36. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cappellari M, Turcato G, Forlivesi S, Zivelonghi C, Bovi P, Bonetti B, et al. ATARTING-SICH nomogram to predict symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis for stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:397–404. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazya M, Egido JA, Ford GA, Lees KR, Mikulik R, Toni D, et al. Predicting the risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in ischemic stroke treated with intravenous alteplase: Safe implementation of treatments in stroke (SITS) symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage risk score. Stroke. 2012;43:1524–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, Andersen G, Berthezene Y, Cheng B, et al. MRI-guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:611–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Lv Y, Zheng X, Qiu J, Chen HS. The impact of cerebral microbleeds on intracerebral hemorrhage and poor functional outcome of acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2017;264:1309–19. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charidimou A, Shoamanesh A, Wilson D, Gang Q, Fox Z, Jäger HR, et al. Cerebral microbleeds and postthrombolysis intracerebral hemorrhage risk updated meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;85:927–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsivgoulis G, Zand R, Katsanos AH, Turc G, Nolte CH, Jung S, et al. Risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke and high cerebral microbleed burden: A meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:675–83. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kongbunkiat K, Wilson D, Kasemsap N, Tiamkao S, Jichi F, Palumbo V, et al. Leukoaraiosis, intracerebral hemorrhage, and functional outcome after acute stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2017;88:638–45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Q, Li Z, Wei R, Lei Q, Liu Y, Cai X, et al. Increased risk of post-thrombolysis intracranial hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke patients with leukoaraiosis: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charidimou A, Pasi M, Fiorelli M, Shams S, von Kummer R, Pantoni L, et al. Leukoaraiosis, cerebral hemorrhage, and outcome after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis (v1) Stroke. 2016;47:2364–72. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prats-Sánchez L, Camps-Renom P, Sotoca-Fernández J, Delgado-Mederos R, Martínez-Domeño A, Marín R, et al. Remote intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis: Results from a multicenter study. Stroke. 2016;47:2003–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prats-Sanchez L, Martínez-Domeño A, Camps-Renom P, Delgado-Mederos R, Guisado-Alonso D, Marín R, et al. Risk factors are different for deep and lobar remote hemorrhages after intravenous thrombolysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Yan S, Xu M, Zhong G, Liebeskind DS, Lou M, et al. More extensive white matter hyperintensity is linked with higher risk of remote intracerebral hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:380–e15. doi: 10.1111/ene.13517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtze S, Haapaniemi E, Melkas S, Mustanoja S, Putaala J, Sairanen T, et al. White matter lesions double the risk of post-thrombolytic intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015;46:2149–55. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CM, Hung CL, Su HC, Lin HJ, Chen CH, Lin CC, et al. Leukoaraiosis and risk of intracranial hemorrhage and outcome after stroke thrombolysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu M, Pan Y, Zhou L, Wang Y. Predictors of post-thrombolysis symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in Chinese patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lokeskrawee T, Muengtaweepongsa S, Patumanond J, Tiamkao S, Thamangraksat T, Phankhian P, et al. Prediction of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: The symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage score. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James B, Chang AD, McTaggart RA, Hemendinger M, Mac Grory B, Cutting SM, et al. Predictors of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage in patients with an ischaemic stroke with neurological deterioration after intravenous thrombolysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:866–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Zand R, Sharma VK, Köhrmann M, Giannopoulos S, et al. Antiplatelet pretreatment and outcomes in intravenous thrombolysis for stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2017;264:1227–35. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo S, Zhuang M, Zeng W, Tao J. Intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:pii: e003242. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkler AE, Salehi Omran S, Gialdini G, Lerario MP, Yaghi S, Elkind MS, et al. Safety outcomes after thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in patients with recent stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:2282–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlinski M, Kobayashi A, Czlonkowska A, Mikulik R, Vaclavik D, Brozman M, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis for stroke recurring within 3 months from the previous event. Stroke. 2015;46:3184–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AbdelRazek MA, Mowla A, Hojnacki D, Zimmer W, Elsadek R, Abdelhamid N, et al. Prior asymptomatic parenchymal hemorrhage does not increase the risk for intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40:201–4. doi: 10.1159/000439141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier N, Nedeltchev K, Brekenfeld C, Galimanis A, Fischer U, Findling O, et al. Prior statin use, intracranial hemorrhage, and outcome after intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1729–37. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Ramirez S, Delgado-Mederos R, Marín R, Suárez-Calvet M, Sáinz MP, Alejaldre A, et al. Statin pretreatment may increase the risk of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage in thrombolysis for ischemic stroke: Results from a case-control study and a meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2012;259:111–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheitz JF, Seiffge DJ, Tütüncü S, Gensicke H, Audebert HJ, Bonati LH, et al. Dose-related effects of statins on symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and outcome after thrombolysis for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:509–14. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erdur H, Polymeris A, Grittner U, Scheitz JF, Tütüncü S, Seiffge DJ, et al. A score for risk of thrombolysis-associated hemorrhage including pretreatment with statins. Front Neurol. 2018;9:74. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meseguer E, Mazighi M, Lapergue B, Labreuche J, Sirimarco G, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, et al. Outcomes after thrombolysis in AIS according to prior statin use: A registry and review. Neurology. 2012;79:1817–23. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318270400b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinoda N, Hori S, Mikami K, Bando T, Shimo D, Kuroyama T, et al. Prediction of hemorrhagic transformation after acute thrombolysis following major artery occlusion using relative ADC ratio: A retrospective study. J Neuroradiol. 2017;44:361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okazaki S, Yamagami H, Yoshimoto T, Morita Y, Yamamoto H, Toyoda K, et al. Cerebral hyperperfusion on arterial spin labeling MRI after reperfusion therapy is related to hemorrhagic transformation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:3087–90. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17718099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dzialowski I, Hill MD, Coutts SB, Demchuk AM, Kent DM, Wunderlich O, et al. Extent of early ischemic changes on computed tomography (CT) before thrombolysis: Prognostic value of the Alberta stroke program early CT score in ECASS II. Stroke. 2006;37:973–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206215.62441.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambrinos A, Schaink AK, Dhalla I, Krings T, Casaubon LK, Sikich N, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43:455–60. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillan M, Alonso-Canovas A, Garcia-Caldentey J, Sanchez-Gonzalez V, Hernandez-Medrano I, Defelipe-Mimbrera A, et al. Off-label intravenous thrombolysis in acute stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:390–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schellen C, Ferrari J, Lang W, Sykora M. VISTA Collaborators. Effects of SSRI exposure on hemorrhagic complications and outcome following thrombolysis in ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:511–7. doi: 10.1177/1747493017743055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berger C, Fiorelli M, Steiner T, Schäbitz WR, Bozzao L, Bluhmki E, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic brain tissue: Asymptomatic or symptomatic? Stroke. 2001;32:1330–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seet RC, Rabinstein AA. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage following intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: A critical review of case definitions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:106–14. doi: 10.1159/000339675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Wei C, Deng L, Wang Z, Song M, Xiong Y, et al. The accuracy of serum matrix metalloproteinase-9 for predicting hemorrhagic transformation after acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:1653–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W, Li M, Chen Q, Wang J. Hemorrhagic transformation after tissue plasminogen activator reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke: Mechanisms, models, and biomarkers. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:1572–9. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whiteley WN, Emberson J, Lees KR, Blackwell L, Albers G, Bluhmki E, et al. Risk of intracerebral haemorrhage with alteplase after acute ischaemic stroke: A secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:925–33. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yaghi S, Eisenberger A, Willey JZ. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in acute ischemic stroke after thrombolysis with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: A review of natural history and treatment. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1181–5. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matrat A, De Mazancourt P, Derex L, Nighoghossian N, Ffrench P, Rousson R, et al. Characterization of a severe hypofibrinogenemia induced by alteplase in two patients thrombolysed for stroke. Thromb Res. 2013;131:e45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]