Abstract

Advancements in nanotechnology and molecular biology have promoted the development of a diverse range of models to intervene in various disorders (from diagnosis to treatment and even theranostics). Manganese dioxide nanosheets (MnO2 NSs), a typical two-dimensional (2D) transition metal oxide of nanomaterial that possesses unique structure and distinct properties have been employed in multiple disciplines in recent decades, especially in the field of biomedicine, including biocatalysis, fluorescence sensing, magnetic resonance imaging and cargo-loading functionality. A brief overview of the different synthetic methodologies for MnO2 NSs and their state-of-the-art biomedical applications is presented below, as well as the challenges and future perspectives of MnO2 NSs.

Keywords: MnO2 nanosheets, synthetic methods, biocatalysis, fluorescence sensing, controlled drug delivery, stimuli-activated imaging

Introduction

Advances in nanotechnology and molecular biochemistry, the ability to decrypt and elaborate multiple artificial materials, the continuous search for new targets, and the disentangling of diverse signaling pathways of many medical disorders have had a conspicuous influence on modern medical practices.1–4 Among the various nanomaterials designed for biomedical applications, two-dimensional (2D) materials, especially transition metal dichalcogenides (eg, MoS2, WS2, TiS2, MoSe2, and WSe2)5 and transition metal oxides (TMOs, eg, MnO2),6 have received a substantial amount of recent attention due to their distinct structure–property relationships in multiple fields, eg, optoelectronics, spintronics, catalysis, defect engineering, and energy-related applications.7–9 Among these materials, manganese oxides have attracted increasing attention because Mn is the twelfth most common element on the planet and the third most abundant transition element after iron and titanium.10 Manganese (II) ions function as cofactors in a number of enzymes with varying functionalities as well as being key components in the oxygen-evolving complexes of photosynthetic plants.11 Additionally, manganese oxide (Mn-oxide) has a variety of structures (nanorods, nanobelts, nanosheets (NSs), nanowires, nanotubes, nanofibers and so on)12 and compositions (MnO, Mn5O8, Mn2O3, MnO2, and Mn3O4)13 which further broadens its applications in a diverse range of fields. Hoseinpour et al reviewed the structures, sizes and applications of Mn NPs prepared via different green synthetic methods in detail.14 Among the various nanostructures, NS is two-dimensional nanostructure with thickness ranging from 1 to 100 nm. A typical NS example is graphene, which is composed of a single layer of carbon atoms with hexagonal lattice.15 NS shares several similar common features, eg, ultralarge specific surface areas and high surface-to-volume ratios, allowing easy contact between reactant molecules and the active sites, thus providing enhanced catalytic activities16 as well as unique optical properties (described below) and excellent photothermal therapy (PTT), etc.17 MnO2 nanosheets (MnO2 NSs) are composed of MnO6 octahedra that share edges, with manganese ions occupying the centers of the octahedra and being coordinated to the six nearest oxygen ions, while each oxygen ion is coordinated to the three nearest manganese ions.18,19 Similar to the structures of other 2D materials, MnO2 NSs possess high specific surface areas and a thickness of nanometers to micrometers. Moreover, the redox reactions between MnO2 and glutathione (GSH) in acidic environment have favored their applications in activatable fluorescent biosensors, controlled drug delivery and activable T1-MR imaging.20–22 As a class of novel and facilely synthesized 2D TMOs with good biocompatibility, MnO2 NSs have received increased attention across a vast range of disciplines, especially biomedicine. In this review, we aim to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art syntheses, biomedical applications, toxicological assessments and challenges/opportunities in the research field of MnO2 NSs. First, various synthetic strategies for the preparation of MnO2 NSs are introduced. Then, we briefly discuss their main biomedical applications. Furthermore, the in vitro and in vivo toxicological evaluations are highlighted. Ultimately, we provide some personal perspectives on the future directions of this promising research field.

Synthesis of manganese dioxide nanosheets (MnO2 NSs)

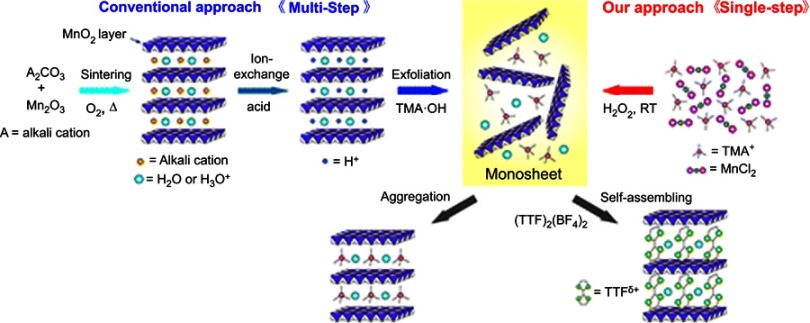

As a class of 2D nanomaterials, NSs are characterized by their nanometer thicknesses as well as lateral dimensions ranging from the submicrometers to micrometer scales. MnO2 NSs with extremely large surface-area-to-mass ratios (SMRs) display a number of distinctive physicochemical properties compared with their bulk form. Hence, the synthesis of MnO2 NSs is of great significance for a variety of novel biomedical applications. To date, several methods have been developed for the preparation of MnO2 NSs. In general, these methods can be classified into two categories: top-down and bottom-up approaches, as is also true of other types of 2D nanomaterials.23 In 2003, Omomo et al. first reported the formation and characterization of unilamellar 2D crystallites of MnO2 as well as the swelling and exfoliation behavior of layered manganese oxide, H0.13MnO2·H2O, which was dissolved in tetrabutylammonium hydroxide solution.24 This traditional top-down approach always utilizes ion-exchange and exfoliation of bulk MnO2 templates to obtain MnO2 NSs. However, this route entails a cost-demanding and time-consuming multistep high-temperature solid-state synthetic process. Moreover, one hurdle that the obtained NSs possess a wide thickness distribution, which is a challenge that must be overcome before their possible future application. In 2008, Kazuya Kai et al demonstrated a single-step bottom-up approach to directly synthesize MnO2 NSs for the first time,25 drawing from the synthetic methodology for producing Ti1-δO2monosheets with uniform shapes and sizes reported by Yoon and coworkers.26 Since then, the bottom-up strategy, as a novel approach to synthesize MnO2 NSs, has attracted the attention of most researchers in this field, owing to its significant advantages, such as an easier preparation and better controlled exfoliation and reaction steps. In this review, we focus on the bottom-up methods for obtaining MnO2 NSs, and their sizes and morphologies when prepared by different approaches have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized sizes and morphologies of MnO2 NSs synthesized by different approaches

| Method | Reaction materials | Morphology | Lateral dimensions | Thickness | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down | H0.13MnO2·0.7H2O + TBAOH | Nanosheet structure | <50 nm | 0.91±0.07nm | 24 |

| Bottom-Up (reductive) | KMnO4+ MES | Nanosheet structure | 141 nm | ~1.5 nm | 28 |

| Bottom-Up (reductive) | KMnO4+ SDS | Single-layered nanosheet | ~200 nm | 0.77–0.95 nm | 29 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ EDTA + NaOH | Thin film of nanosheet | 2–5 µm width | ~10 nm | 27 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ TMA.OH | Single-layered NS | <200 nm | Nearly 80% <1 nm | 25 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ H2O2+ TMA.OH | A two-dimensional sheet structure |

~200 nm | ~1.3 nm. | 111 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ (NH4)2S2O8+ TMA.OH | Flat morphology | 2 µm | ~4.07 nm | 35 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ H2O2+ TMA.OH | A sheet-like structure | N/A | ~1.5 nm | 36 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ H2O2+ TMA.OH | Nanosheet structure | 100–200 nm | N/A | 69 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ H2O2+ TMA.OH | Polycrystalline sheet structure | 141 nm | 1.5 nm | 150 |

| Bottom-Up (oxidative) | MnCl2+ H2O2+ TMA.OH | Single-layer sheet structure | 200 nm | ~1.5 nm | 170 |

Abbreviations: TMA.OH, tetramethylammonium hydroxide; TBA.OH, tetrabutylammonium hydroxide; NS, nanosheet.

Manganese ion (Mn2+) based oxidative methodology

The preparation of multilayer MnO2 NSs (ca. 10 nm in thickness) with bottom-up approaches has mainly been achieved by the oxidation of Mn2+ or the reduction of KMnO4 with a self-sacrificing template (eg, graphene oxide nanosheets; GO NSs) or a chelating agent (eg, EDTA)27 in the presence of reducing or oxidizing reagents. In 2007, Oaki and Imai proposed bottom-up approach to obtain MnO2 NSs by the oxidation of manganese ions with dissolved oxygen in the solution.27 EDTA was utilized as a chelating agent for the manganese ions (Mn2+) to hinder the rapid precipitation of Mn(OH)2. However, their precipitate consisted of multiple layers with thicknesses of 10 nanometers or greater (ie, over 10 layers). Moreover, the time-consuming process (at least 3 days) was unavoidable. To address these issues, inspired by the single-step route reported by Yoon for the synthesis of titanate dioxide nanosheets (Ti1-δO2 NSs), Kazuya Kai and coworkers attempted to prepare MnO2 NSs with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as an oxidant in an alkaline medium and TMA cations for the exfoliation of layered H/MnO2. However, unlike the method form Yoon, their reaction readily proceeded at ambient temperature instead of heating under reflux (Figure 1).26

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the single-step oxidative method with H2O2 at room temperature versus the conventional method.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Kai K, Yoshida Y, Kageyama H, et al. Room-temperature synthesis of manganese oxide monosheets. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(47):15938–15943.25 Copyright (2008) American Chemical Society.

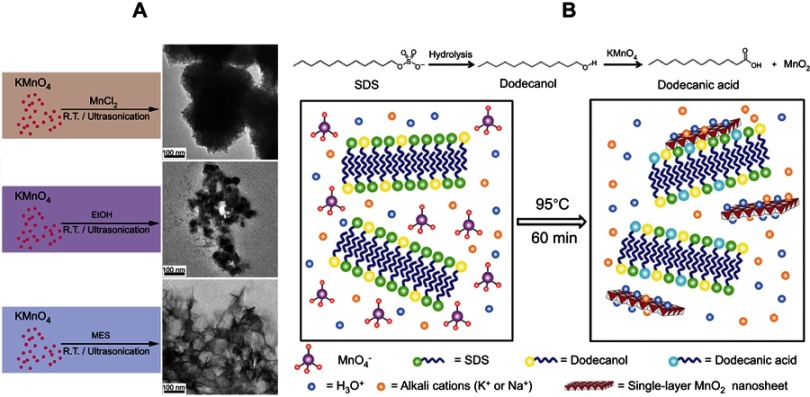

Potassium permanganate (PP, KMnO4)-based reductive methodology

Compared to the top-down and the oxidative bottom-up methods, a reductive bottom-up method has been developed in recent years. With KMnO4 as the Mn source, different reactive agents have been introduced to prepare MnO2 NSs. For example, Liu et al first obtained MnO2 NSs via the addition of an aqueous KMnO4 solution into a 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer at pH 6. Compared with other reducing reagents (eg, MnCl2 and ethanol), the use of the MES buffer as the reducing agent showed the best results (Figure 2A).28 Later, in 2015, Yin and coworkers developed a facile template-free, one-step and one-phase reductive strategy to synthesize single-layered MnO2 NSs with sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) as the reducing agent. In their system, SDS not only played the role of a precursor of dodecanol to reduce KMnO4 but also was a structure-directing agent to promote the formation of the MnO2 monosheets, which opened up the possibility of constructing other NS without the use of an exfoliation reagent (Figure 2B).29 Indeed, this reductive method was more facile in both principle and practice because a variety of reductants could be selected. Furthermore, the synthetic process for the MnO2 NSs was more controllable. Nonetheless, an inevitable drawback was that KMnO4 tended to decompose in hydrothermal environments (ca. 95°C), which challenged researchers attempting to verify the exact mechanisms of the corresponding chemical reactions.30–34

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic illustration for the control experiments of reductants employed in the growth of MnO2 nanomaterials at ambient temperature (left) and TEM characterization of the corresponding products (right). Reprinted with permission from Deng R, Xie X, Vendrell M, Chang Y, Liu X. Intracellular glutathione detection using MnO(2)-nanosheet-modified upconversion nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(50):20168–20171.28 Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society. (B) Schematic illustration for MnO2 NS formation based on the KMnO4 and SDS reaction. Reprinted with permission fromLiu Z, Xu K, Sun H, Yin S. One-step synthesis of single-layer MnO2 nanosheets with multi-role sodium dodecyl sulfate for highperformance pseudocapacitors. Small. 2015;11(18):2182–2191.29 Copyright © 2015, John Wiley and Sons.

Biomedical applications of MnO2 nanosheets (MnO2 NSs)

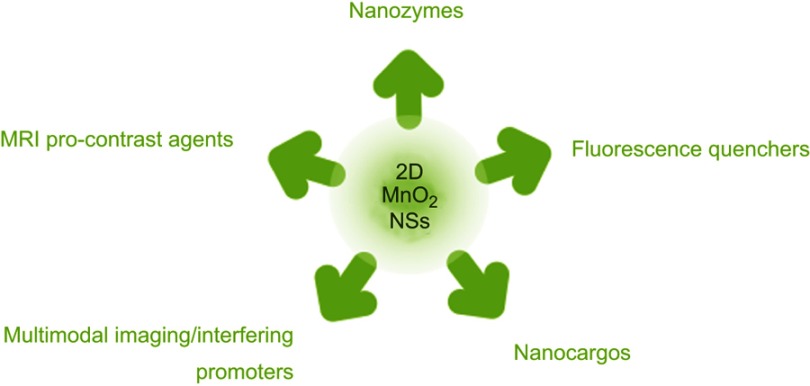

Since the intriguing 2D structure and distinct physical/chemical properties were initially identified, MnO2 NSs have received much attention and have exhibited favorable potential for application in a wide range of disciplines, such as physics,37 chemistry,38 material science39 (especially energy-related applications, eg, solar cells,40 supercapacitors,41–45 and lithium-ion batteries46,47), optoelectronics,48,49 spintronics,18 biomedicine,40 and so forth. Particularly, their broad use in biological sensing and catalysis, drug delivery and controlled release, PTT and chemo-dynamic therapy (CDT),21 molecular imaging and engineering, etc., has shown promising potential. Herein, we summarize a majority of the MnO2 NS applications in recent years in the field of biomedicine (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the diverse roles MnO2 NSs have played in the field of biomedicine.

As a nanozyme: biocatalysis based on MnO2 NSs

In recent decades, nanotechnology and biochemistry have flourished, including artificial materials with multiple applications.7,50,51 Certain nanomaterials possess enzymatic-like profiles and substrate specificities, which are commonly called “Nanozymes”. Despite the substrate specificities of nanozymes rarely being as high as those of natural enzymes, their multiple active sites favor more efficient and steady catalytic activity. Additionally, owing to their tunable structures, their related properties can be controlled and optimized.52,53 Furthermore, compared with natural enzymes, nanozymes are more compatible with specific environments, such as high temperatures, and low or high pH conditions.54 These features give rise to their promising applications in a variety of fields.

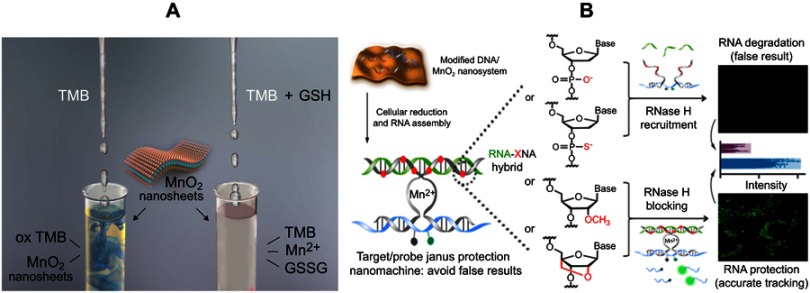

Nanozymes, mainly comprising carbon,55,56 metal,57,58 and metal oxide,59,60 mimic the functionality of natural enzymes, but have different structures. Amongst them, 2D nanomaterials,61 with ultralarge surface areas and flexible structures, enable their excellent catalytic activity and can be incorporated into the surrounding environment to improve substrate specificity. For instance, graphene oxide has been confirmed to possess intrinsic peroxidase-like activity in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),62,63 so as to ultrathin graphitic carbon nitride (g-CN)64,65 and molybdenum disulfate nanosheets (MoS2 NSs),66 which are only pragmatic for use as ex-vivo or in vitro substrates. MnO2 NSs, a typical 2D nanomaterial, also possess intrinsic oxidase-like activity. In 2012, Liu and Wang et al. employed 3,3ʹ,5,5ʹ-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) as a tracer to test this property.67 The oxidation of the pale yellow-colored substrate (TMB) to the blue-oxidized product (ox-TMB) indicated the catalytic activity of the MnO2 NSs. Based on this, Liu and colleagues have developed a selective, rapid, and reliable colorimetric assay for the determination of GSH because GSH can further lead to a concentration-dependent reduction of ox-TMB and a proportional decrease in the absorption at ca. 650 nm (Figure 4A).68 Notwithstanding their utilization as a group of nanozymes with oxidase activity, MnO2 NSs can also act as indirect DNA partzymes to some extent. Recently, Zhao et al fabricated a MnO2 NS-powered target/probe Janus protected DNA nanomachine to achieve RNA imaging. In this DNA machine, the MnO2 NSs were utilized as both promoters for the cellular uptake of DNA and generators of Mn2+ as indispensable DNAzyme cofactors, ensuring the efficiency of catalytic cleavage (Figure 4B).69

Figure 4.

(A) Illustration of the MnO2 NS-based colorimetric assay for GSH quantification, where the MnO2 NSs acted as an oxidase-like nanozyme for the formation of ox-TMB and GSSG. Reprinted from Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 90, Liu J, Meng L, Fei Z, Dyson P, Jing X, Liu X. MnO nanosheets as an artificial enzyme to mimic oxidase for rapid and sensitive detection of glutathione, 69–74, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.68 (B) Schematic design of the Janus protected DNA nanomachine, where miRNA-21 is employed as a model cellular RNA target (green sequence), the red X denotes DNA, PS (phosphorothioate)-DNA, 2ʹOMe (methylation)-DNA and LNA (locked nuclease acid) monomers, which are highlighted in the DNA partzymes (gray sequences). Reprinted with permission from Chen F, Bai M, Zhao Y, Cao K, Cao X, Zhao Y. MnO-nanosheet-powered protective janus DNA nanomachines supporting robust RNA imaging. Anal Chem. 2018;90(3):2271–2276.69 Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

As a quencher: fluorescence sensing based on MnO2 NSs

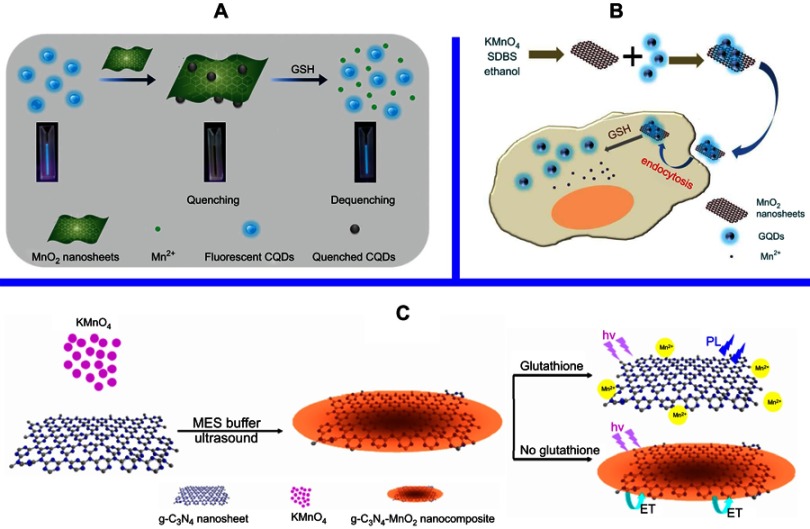

The use of 2D nanomaterials with light harvesting and/or electron-conducting capacities has emerged as a promising nanoplatform for biological and/or chemical sensing based on the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), photoinduced transfer mechanisms, etc.70,71 Fluorescence or Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a mechanism delineating nonradiative energy transfer72 from a luminescent donor to an energy acceptor in proximity (ie, 1–10 nm) mediated by dipole-dipole coupling.73,74 Due to its high sensitivity and suitability for homogeneous detection, FRET has been universally utilized in a variety of fields, eg, microscope,75 immunoassay,76,77 nucleic acid hybridization78–81 and macromolecule interactions .82,83 As a 2D nanomaterial as well as an ultrathin semiconductor, MnO2 NSs exhibit a broad and intense absorption band at ca. 374 nm,24 making them as an efficient broad-spectrum quencher, which is resulted from the d–d transitions of manganese ions in the ligand field of the edge-sharing MnO6 octahedral crystal lattice.24 The use of MnO2 NSs as fluorescence quencher can mainly be ascribed to two aspects: their broad and intense absorption band at ca. 374 nm and the break-up of the NSs structure with the reduction of MnO2 into Mn2+. Ji et al designed a multifunctional nanosystem, CaO2/MnO2@polydopamine-methylene blue (MB) nanosheets (CMP-MB), where the fluorescence of MB was suppressed by the MnO2 NS. Once exposed to a tumor microenvironment, the MnO2 NSs could decompose into Mn2+, which triggered the emission of MB fluorescence. Hence, switch-controlled tumor cell imaging was achieved.84 Xia et al. found that the MnO2 NS mediated quenching effect can be reversed via the reduction of MnO2 into Mn2+ by ascorbic acid (AA), resulting in MnO2 NS destruction. Based on this, they developed a carbon dot (CD)-MnO2 nanocomposite for the determination of ALP with help from the hydrolysis of 2-phosphate (AAP) into AA. Utilizing the CD-MnO2 nanocomposite as a sensing probe, a label-free fluorescent switching strategy for detecting ALP activity was realized with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.4 U/L.85 In 2015, with the reduction of MnO2 into Mn2+ by GSH, Wang and coworkers employed fluorescent CDs and MnO2 NSs as an energy donor-acceptor pair to construct a nanoplatform for GSH detection (Figure 5A).86 In addition to employing MB and CDs as fluorescence donors, Yan et al fabricated a graphene quantum dot (GQD)-MnO2 NS-based optical sensing platform for GSH detection (Figure 5B).87 Chu and colleagues developed a MnO2 NS-modified upconversion (UC) nanosystem for sensitive switchable fluorescence detection of H2O2 and glucose in blood. The enzymatic cleavage and unification of glucose by glucose oxidase (GOx) generated H2O2, which was then utilized to reduce MnO2 to Mn2+, similarly to GSH (as depicted by the equation: MnO2+ H2O2+2H+ = Mn2+ +2H2O + O2) (Figure 5C).88

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic illustration of the preparation of CDs-MnO2 NSs and the principle of the FRET-based CD-MnO2 NSs architecture for GSH sensing. Republished with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from A sensitive turn-on fluorescent probe for intracellular imaging of glutathione using single-layer MnO2 nanosheet-quenched fluorescent carbon quantum dots, He D, Yang X, He X, et al, 51, 79, 2015; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearence Centre, Inc.170 (B) Scheme for the preparation of MnO2 NSs and the mechanism of a GQD-MnO2 NS-based optical sensing nanoplatform for monitoring GSH in MCF-7 cells. Reprinted with permission from Yan X, Song Y, Zhu C, et al. Graphene quantum dot-MnO2 nanosheet based optical sensing platform: a sensitive fluorescence“Turn Off-On” nanosensor for glutathione detection and intracellular imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(34):21990–21996.87 Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (C) Schematic illustration of a g-C3N4 NS-MnO2 NS sandwich-like nanocomposite for GSH sensing. Reprinted with permission from Zhang X, Zheng C, Guo S, Li J, Yang H, Chen G. Turn-on fluorescence sensor for intracellular imaging of glutathione using g-C3N4 nanosheet-MnO2 sandwich nanocomposite. Anal Chem. 2014;86(7):3426–3434.151 Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

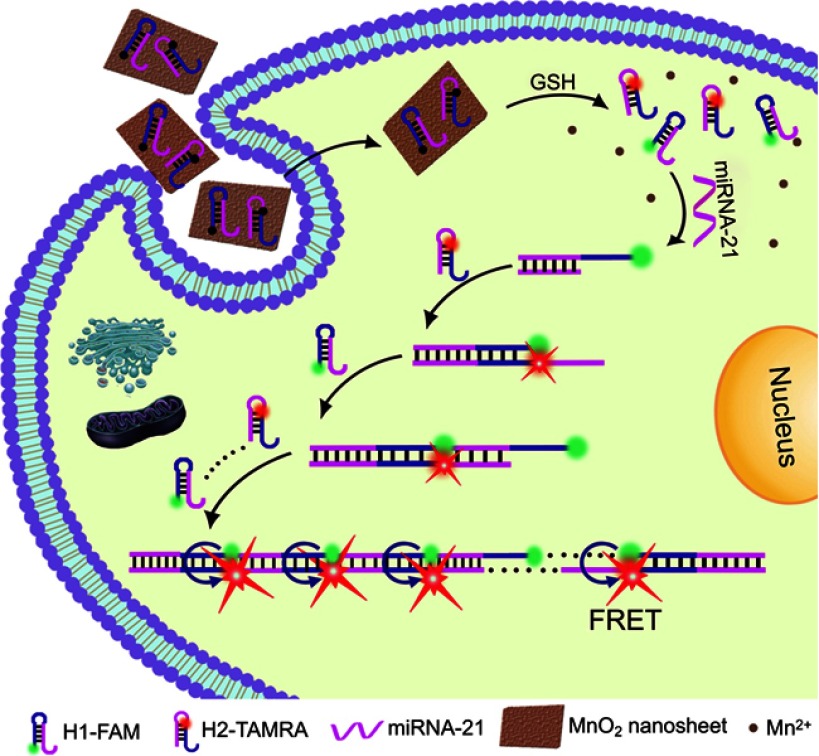

In addition to sensing relatively more tractable and visible substances, such as GSH and H2O2,MnO2 NSs can also be utilized for tracking RNAs even at very low levels. As is well-known, miRNAs can regulate gene expression by promoting the degradation or inhibition of the translation of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in epigenetics,89–91 thereby playing momentous roles in cell differentiation,92–95 proliferation,96 tumorigenesis,97,98 metastasis,99,100 apoptosis,98 autophagy101,102 and many other biochemical processes. Despite quantitative determination of various miRNAs being accomplished by traditional detection strategies, eg, PCR and northern blot, these previously developed methods possess unavoidable costs and are time-consuming as well as having sensitivity limiting shortcomings. Therefore, recent alternatives have incorporated a variety of signal amplification approaches such as nanomaterials,80,103–106 enzymes,107 electrochemical108 or electrochemiluminescent109 transduction fashion to detect target miRNAs with both high selectivity and high sensitivity. In 2017, Xiang and colleagues reported a biodegradable MnO2 NS-based hybridization chain reaction (HCR) strategy to determine miRNA expression even at exceedingly low levels in living cells.110 They designed two hairpins which were separately labeled with the organic dyes FAM (as a FRET donor) and Tamra (TMR, as a FRET acceptor) and loaded onto MnO2 NSs. Thereafter, once entering living cells, the hairpins would be released because of the displacement responses as well as the degradation of the MnO2 NSs by intracellular GSH. Then, miRNA-21 in living HeLa cells triggered the hairpins to convene into double-stranded polymers, resulting in prominent amplification of the FRET signal for the determination of trace levels of miRNA-21 in living cells (Figure 6).111 It is anticipated that this inspiring work might open up new opportunities for monitoring multiple trace-level RNA species in living cells with greater accuracy, sensitivity and integrity.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the MnO2 NS-mediated intracellular-hybridized chain reaction (HCR) signal amplification system for efficiently detecting miRNA-21 in living HeLa cells. The MnO2 NSs could deliver two types of hairpin DNA probes into the cytosol. Overexpressed glutathione (GSH) in HeLa cells and displacement reactions by other proteins or nucleic acids promoted the decomposition of the MnO2 NSs to release free hairpins, which assembled into double-stranded (dsDNA) polymers upon binding to the target miRNA-21. Subsequently, enhanced FRET signals were produced to realize accurate and sensitive detection. Reprinted with permission from Li J, Li D, Yuan R, Xiang Y. Biodegradable MnO2 nanosheet-mediated signal amplification in living cells enables sensitive detection of down-regulated intracellular MicroRNA. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(7):5717–5724.111 Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Finally, the applications of various MnO2 NS-based fluorescent biosensors for determining specific targets are listed in Table 2, and their different values for the limits of detection (LODs) as well as the linear concentration ranges of the corresponding targets are mentioned.

Table 2.

Fluorescent biosensors based on MnO2 NSs

| Nanomaterials | Targets | Linear response concentration | Limit of detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDs-MnO2NS architecture | GSH | 0.2–600 µM | 22 nM | 86 |

| CDs-MnO2 nanocomposite | ALP | 1–100 U/L | 0.4 U/L | 85 |

| CQDs-MnO2 nanocomposite | GSH | 0.01–200 µM | 0.01 µM | 170 |

| GQDs-MnO2 nanoplatform | GSH | 0.5–10 µM | 150 nM | 87 |

| g-C3N4-MnO2nanosandwich | GSH | 200–500 µM | N/A | 151 |

| MnO2 NS-UCP nanosystem | GSH and H2O2 | 0–250 and 250–400 µM | 3.7 µM | 88 |

| MnO2 NS-UCP nanosystem | L-lactic acid | 50–400 and 450–800 µM | 10 µM | 88 |

| MnO2 NS-FAM +TMR hairpins | miRNA-21 | 100–250 nM | 100 nM | 111 |

| MnO2 NS label-free platform | Mercury(II) (Hg2+) | 0–20 n M | 0.8 nM | 112 |

| MnO2 NS label-free platform | Ochratoxin (OTA) | 0.02–2 nM | 0.02 ng/mL | 113 |

| MnO2 NS label-free platform | Cathepsin (Cat D) | 1–100 ng/mL | N/A | 113 |

| MnO2 NS-7-hydroxycoumarin | Ascorbic acid | 0.5–40 µM | 0.09 µM | 114 |

| MnO2 NS-7-hydroxycoumarin | GSH | 1–25 µM | 300 nM | 68 |

| MnO2 NS & ligand-DNA FP | Silver ions (Ag+) | 30–240 nM | 9.1 nM | 115 |

| Ru(BPY)3@MnO2 nanoprobe | GSH | 0–300 µM | 420 nM | 157 |

| MSNs-G@MnO2 NSs | GSH | 100 nM to 10 µM | 34 nM | 116 |

| MnO2 NS-cascade logic circuit | GSH | 20–2,000 nM | 6.7 nM | 152 |

Abbreviations: CD, carbon dot; GSH, glutathione; NS, nanosheet; GQD, graphene quantum dot.

As a nanocarrier for controlled drug delivery: cargo-loading functionality based on MnO2 NSs

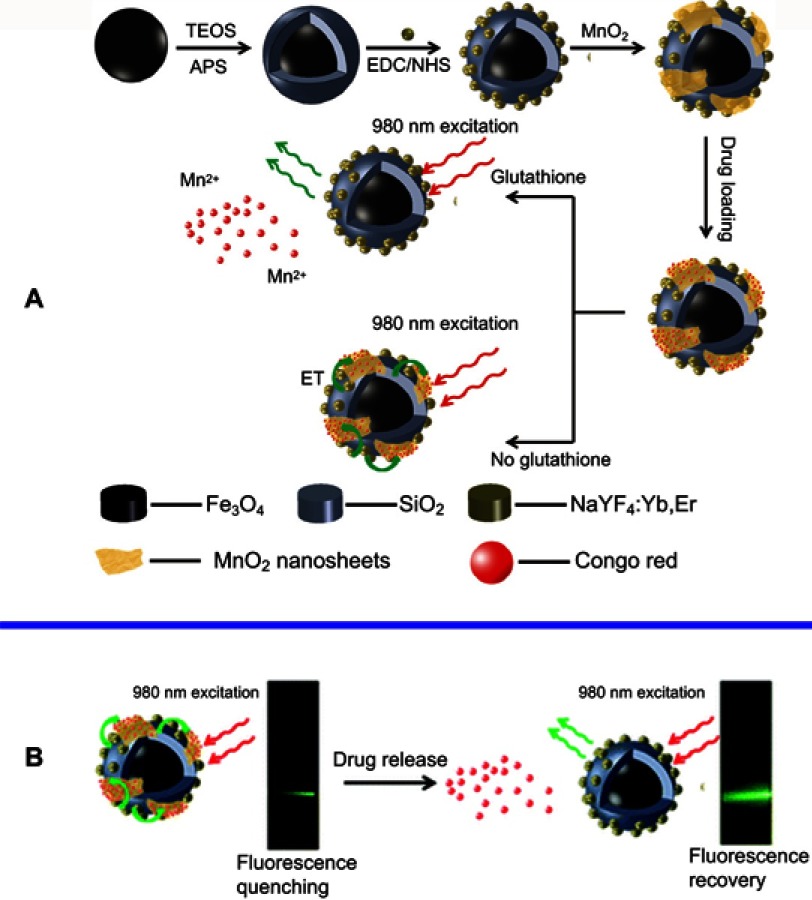

As mentioned above, MnO2 NSs, with extremely large SMRs, exhibit a wide range of distinctive physicochemical properties compared with their bulk composition. One of most typical biomedical applications of MnO2 NS, is drug delivery due to their large SMRs. Moreover, distinct from conventional drug delivery systems (DDSs), MnO2 NS-based nanoplatforms can function as controlled or on-demand DDSs. The controlled drug delivery systems (c-DDSs) for current medications have received increasing interest from numerous chemists and clinical physicians owing to their low toxicities, broad therapeutic windows and ideal administrational efficacies compared with conventional DDSs.117–121 On-demand DDSs triggered by intrinsic physiological microenvironment changes (eg, pH,122 redox agents,123,124 enzymes,125 and heat126,127) and/or external artificially introduced stimuli128,129 (eg, light,130 laser pulses,131 magnetic/electronic fields,132 and ultrasonication133) can simultaneously diminish the side-effects of anticancer agents toward normal tissue to improve the therapeutic effects. Previous reports on DDSs have mainly focused on nanocomposites, such as magnetic composites and upconversion nanoparticles, and most of them have been magnetically functionalized mesoporous materials or hollow spherical particles with the drugs being released via changes in the pH or temperature.121,134–137 For the use of MnO2 NSs as controlled drug delivery nanocarriers, two main properties are beneficial: a large specific surface area and a sensitive response to the tumor microenvironment. In 2013, Zhao et al proposed a novel and facile strategy for the fabrication of multifunctional nanocomposites with silica-coated Fe2O3 particle cores and NaYF4׃Yb,Er shells, on which MnO2 NSs were further grown for delivery and release of a model drug, Congo red (CR). In this nanosystem, the MnO2 NSs served not only as carriers for the loading and release of CRin vitro but also as efficient quenchers for the UC luminescence to monitor intracellular GSH concentration (Figure 7).138 The drug was released upon reduction of MnO2 to Mn2+ by GSH, while simultaneously increasing the UC luminescence. The fabricated nanocomposite is a promising platform due to its GSH-stimulated smart drug delivery and UC luminescence monitoring. Indeed, the nanocarrier functionality of MnO2 NSs has rarely been applied individually and has always been combined with other pragmatic components, eg, fluorescence quenchers and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) probes, which will be mentioned below.

Figure 7.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthetic procedure for the preparation of the MSU/MnO2-CR drug delivery system. (B) Images of the MSU/MnO2-CR system before and after drug delivery under 980 nm excitation. Republished with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from Multifunctional MnO2 nanosheet-modified Fe3O4@SiO2/NaYF4: yb,Er nanocomposites as novel drug carriers, Zhao P, Zhu Y, Yang X, et al, 43, 2, 2014; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearence Centre, Inc.138

As an MRI pro-contrast agent: stimuli-activated imaging based on MnO2 NSs

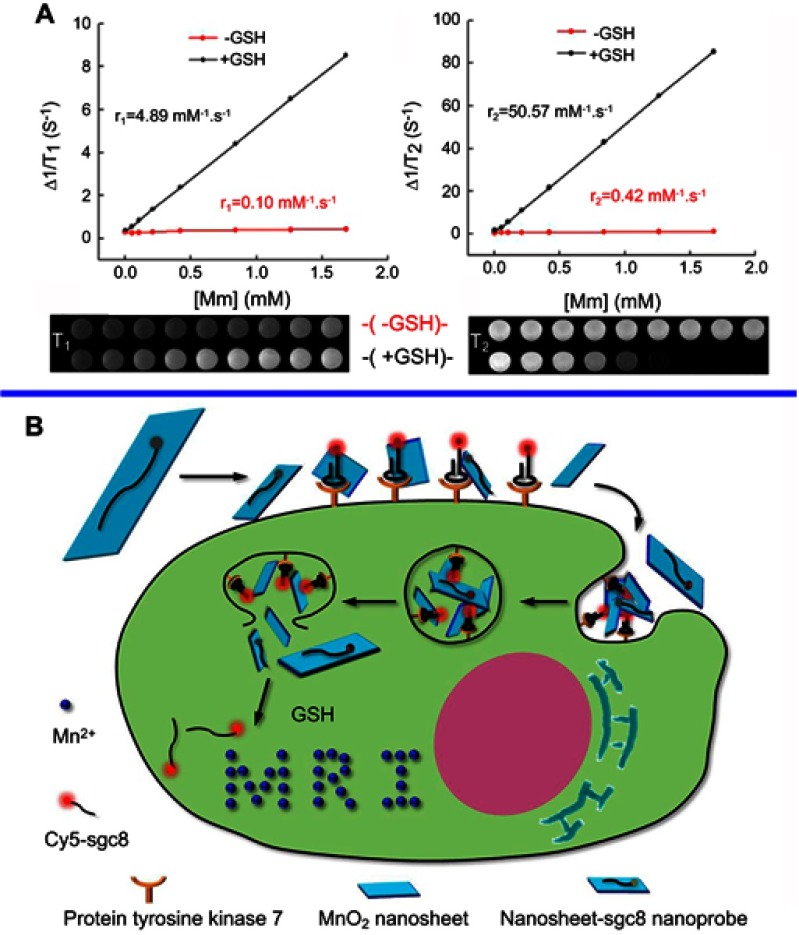

MRI was originally known as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)139 imaging and belongs to a configuration of NMR, albeit the “nuclear” employed in the acronym was omitted to avoid negative associations with the word. Certain atomic nuclei are capable of absorbing and releasing radiofrequency (RF) energy in the presence of an external magnetic field. Hydrogen atoms are typically applied to boost the detectable RF signals which can be received by antennas in proximity to the corresponding anatomy for examination. By altering the parameters of the pulse sequence, different degrees of contrast may be generated between tissues based on the relaxation properties of their hydrogen atoms.140,141 Compared with other imaging modalities, the main advantage of MRI is its superb spatial resolution whereas its major drawback is the limited sensitivity. As such, chemistry and materials science research has focused on searching for solutions capable of solving this challenging hurdle142 The introduction of contrast agents (CAs) has been the main solution. Paramagnetic complexes comprising metal ions with symmetric electronic ground states, eg, gadolinium (Gd3+)143 and manganese (Mn2+),144 have been successfully applied as MRI CAs since the late 1980s145 in virtue of their outstanding capabilities to decrease the longitudinal relaxation time T1 of water protons dipolarly interacting with the unpaired electrons of the metal ions. Manganese-based oxides have been demonstrated as alternative CAs for T1-weighted MRI, with relatively improved biocompatibilities and cytotoxicities, to replace the clinically widespread gadolinium-based CAs, which have been warned by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to the correlation between gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, kidney dysfunction, etc.146–149 The Mn atoms in MnO2 nanosheets are coordinated in an octahedral geometry to six oxygen atoms and shielded from aqueous environments, making no contribution to the longitudinal or tranverse relaxation of the protons.150 As Zhang and coworkers reported, the relaxation rate (r1 value) of initial PEG-MnO2 NSs was very low (0.007 mM−1 s−1), which was ascribed to the high valence (IV) of manganese and the shielded paramagnetic centers being inaccessible to water molecules.151 Upon disintegration and degradation, the released Mn2+ gives rise to a highly improved T1-MRI performance because of the five unpaired 3d electrons and the enhanced accessibility of the paramagnetic centers to the surrounding water molecules. As illustrated by Zhang et al, the longitudinal relaxivity r1 and transverse relaxivity r2, obtained by measuring the relaxation rate as a function of Mn concentration, exhibited a 48- (from 0.1 to 4.89 mM−1 s−1) and 120-fold (from 0.42 to 50.57 mM−1 s−1) enhancement, respectively, when the MnO2 NSs were reduced to Mn2+ by GSH (Figure 8A).150 The decomposition of MnO2 NSs in the tumor microenvironment (GSH-activated152,153 or pH-dependent154,155) to release Mn2+ can be utilized for tumor cell MR imaging. Wang and Shi’s group in 2014, presented an intriguing achievement with their report on an intelligent theranostic platform based on highly disperse 2D MnO2 NSs for concurrent ultrasensitive pH-responsive MRI and drug delivery/release.156

Figure 8.

(A) Determination of the T1 (left) and T2 (right) relaxation rates of a MnO2 nanosheet solution (red lines) and MnO2 nanosheet solution treated with GSH (black lines). The related T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI images were presented below. (B) Schematic illustration of the activation mechanism of the MnO2 NS-aptamer nanoprobe for fluorescence/MRI bimodal tumor cell imaging. Reprinted with permission from Zhao Z, Fan H, Zhou G, et al. Activatable fluorescence/MRI bimodal platform for tumor cell imaging via MnO2 nanosheet-aptamer nanoprobe. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(32):11220–11223.150 Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

In addition to MRI, MnO2 NSs have shown promising potential for the fabrication of dual-activatable fluorescence/MRI bimodal platforms. In 2014, Tan and coworkers designed a redox-capable MnO2 NS-aptamer nanoprobe for multimodal imaging of tumor cells (Figure 8B).150 In this platform, the MnO2 NSs played three roles as a DNA nanocarrier, fluorescence quencher and intracellular GSH-activated MRI CA. Upon encountering the target cells, the binding of the aptamer to the corresponding target weakened the absorption of the probe on the NSs and produced a fluorescence recovery as well as aptamer-mediated endocytosis. The intracellular GSH further reduced the MnO2 NSs into a large amount of Mn2+ suitable for MRI. Using a similar principle, a MnO2 NS-Ru(II) complex nanoarchitecture, Ru(BYP)3@MnO2 (BYP = 2,2ʹ-bipyridine) has also been developed for determining GSH in vitro and in vivo.157

Despite the multimodal imaging applications of MnO2 NSs in conjunction with their fluorescence and MR imaging, many exploits have been attempted to accomplish theranostic applications (ie, imaging and killing at the same time). Notably, the PEG-MnO2 NSs reported by Wang and colleagues in 2014 promoted ultrasensitive pH-triggered concurrent diagnostic and therapeutic functionalities (designated as theranostics) for cancers, which provided a novel and facile platform for concurrent ultrasensitive pH-stimulated T1-weighted MRI and anti-tumor drug (doxorubicin, Dox) release (Figure 9).156 The pH-triggered rapid decomposition of 2D MnO2 NSs in a mildly acidic microenvironment could facilitate the controlled release of delivered anticancer agents and circumvent the multidrug resistance of cancer cells by bypassing the typical P-glycoprotein (P-gP)-induced efflux process with MnO2 NSs due to their larger size than free Dox molecules.158

Figure 9.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthetic procedure for the PEG-MnO2 NSs. (B) Theranostic functionality of the PEG-MnO2 NSs for intracellular pH-responsive drug release and the axial and coronal T1-MRI images of 4T1 tumor-bearing nude mice before (a1, b1) and after (a2 – a9 and b2 – b9) administration of the PEG–MnO2 nanosheets within the tumor and normal subcutaneous tissue. PEG denotes ethylene glycol. Reproduced with permission from Chen Y, Ye D, Wu M, et al. Break-up of two-dimensional MnO2 nanosheets promotes ultrasensitive pH-triggered theranostics of cancer. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2014;26(41):7019–7026.156 Copyright © 2014, John Wiley and Sons.

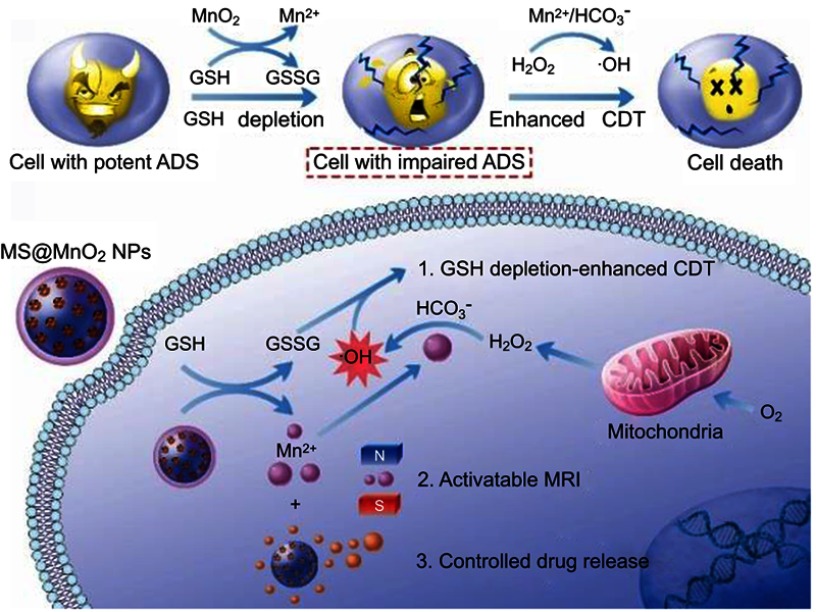

MnO2 NSs themselves can be used not only as nanocarriers for drug delivery, but also as therapy agents. Recently, Xiaoyuan Chen and colleagues at the National Institute of Health (NIH) reported that the construction of MnO2-based nanoagents can augment the efficiency of CDT (Figure 10).21 CDT utilizes iron-initiated Fenton chemistry to kill tumor cells via the conversion of endogenous H2O2 into hydroxyl radicals (·OH), which have a high toxicity, inducing intracellular oxidative stress.159–162 To date, a number of iron-carrying nanoparticles have been employed as CDT agents to induce ferroptosis163 in tumor cells via H2O2-dependent Fenton-like reaction.164–167 As envisaged, the overproduction of GSH in tumor cells ought to be one of the most formidable hurdles for the CDT effect in that GSH serves as a scavenger of the highly reactive ·OH generated by chemodynamic agents, thereby increasing the resistance of cancer cells to oxidative stress and diminishing the efficacy of CDT.168,169 Chen et al was the first time to report that MnO2, which possesses both Fenton-like Mn2+ delivery and GSH depletion capabilities, could play a role as a novel chemodynamic agent in order to improve the CDT of cancer via simultaneously disrupting the antioxidant system and loading an ·OH generator into cells. Ultimately, they utilized MnO2 NSs to successfully construct an activatable theranostic nanosystem for an MRI-monitored chemo-chemodynamic combination regimen.21

Figure 10.

Schematic illustrations of the mechanism and application of mesoporous silicon (MS)@MnO2 NPs for MRI-monitored chemo-chemodynamic combination therapy. Reproduced with permission from Lin L, Song J, Song L, et al. Simultaneous fenton-like ion delivery and glutathione depletion by MnO-based nanoagent to enhance chemodynamic therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(18):4902–4906.21 Copyright © 2018, John Wiley and Sons.

In conclusion, as an MRI CA, MnO2 NSs can produce an activatable MRI signal upon the degradation of their structure in the tumor microenvironment, favoring the improvement of the signal-to-noise ratio and specificity. Additionally, benefitting from the high surface area, fluorescence quenching ability and CDT ability of MnO2 NSs, MRI-based theranostic platforms and multimodal imaging nanoprobes can be easily fabricated with the help of MnO2 NSs, which undoubtedly broadens the applications of MRI.

Taken together, MnO2 NSs have displayed promising potential in multiple modalities for the diagnosis, treatment and theranostics of tumors in vitro and in vivo.

Toxicity evaluation of MnO2 nanosheets (MnO2 NSs)

With the widespread use of MnO2 NSs in a range of biomedical applications, their toxicological assessment both in vitro and in vivo is extremely important. Nonetheless, there are still a limited number of toxicity studies on MnO2 NSs especially in vivo. MTT assays and cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assays are two commonly employed methods to assess the toxicity of MnO2 NSs in various cells. Herein, we present the main cytotoxicity testing results of various nanomaterials based on MnO2 NSs. He et al developed a single-layer MnO2 NS-quenched fluorescent carbon quantum dots, and their nanosystem exhibited no apparent cytotoxicity at the concentrations of 30 µg/mL or less when exposed to HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells for 24 hrs.170 Similarly Yan et al reported of GQD-MnO2 NS based optical sensing nanoplatform and confirmed that this nanomaterial had low toxicity even at a concentration of 40 µg/mL, toward MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma cells.87 Zhang et al have reported that their graphitic-C3N4NS-MnO2 sandwich-like nanocomposite displayed no apparent loss in cell viability even at a 50 µg/mL exposure to HeLa cells.151 Recently, corresponding cytotoxicological assessments of MnO2 NS-based nanosystems in HeLa and MCF-7 cells were carried out by the Xiang group,111 Chen and coworkers69 and Shi and colleagues.157 They all reported excellent biocompatibilities and insignificant viability losses as listed in Table 3. It is also remarkable that the effort of Zhao et al to fabricate MnO2 NS-aptamer nanoprobes early in 2014 verified that 79% of CCRF-CEM and Ramos human B lymphoma cells remained alive following by exposure to their nanoprobes at a concentration of 1 mM for 24 hrs.150

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity results of various nanomaterials based on MnO2 NSs

| Nanomaterials | Cell lines | Response, maximum exposure concentration, and duration | Testing assays | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQDs-MnO2 NS | HeLa | No apparent loss of cell viability, 30 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 170 |

| GQDs-MnO2 nanoprobe | MCF-7 | Low cytotoxicity, 40 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 87 |

| g-C3N4-MnO2 nanosandwich | HeLa | No apparent loss of cell viability, 50 µg/mL, 24 hrs | CCK-8 | 151 |

| MnO2 NS-FAM + TMR hairpins | HeLa | Insignificant viability loss, 86% alive, 60 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 111 |

| MnO2 NS-FAM + TMR hairpins | MCF-7 & HepG2 | Low cytotoxicity, 90 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 171 |

| MnO2 NS-Janus DNA machine | MCF-7 | Good biocompatibilty, 100 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 69 |

| MnO2 NS-aptamer nanoprobe | CCRF-CEM and Ramos | 79% of cells remained alive, 1 mM, 24 hrs | MTS | 150 |

| Ru(BPY)3@MnO2 nanoprobe | HeLa | The viabilities remained higher than 87%, 160 µM, 24 hrs | MTT | 157 |

| MnO2 NS-“DD-A” binary probe | HepG2 | Low cytotxicity, 90 µg/mL, 24 hrs | MTT | 172 |

Abbreviations: CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; NS, nanosheet; GQD, graphene quantum dot.

Conclusion and perspectives

Over the last few decades, research on the synthesis and biomedical applications of MnO2 NSs has thrived and seen impressive advancements. In this review, first of all, we highlighted the state-of-the-art strategies that have been developed for the preparation of MnO2 NSs by top-down or bottom-up methods. Notwithstanding, in contrast to other 2D nanomaterials, the top-down approach of MnO2 NS synthesis is obviously costly and time-consuming. Moreover, it is fairly difficult to completely exfoliate the protonated compounds completely into single-layer NSs (monosheets), thus, previously obtained NSs have always had a wide thickness distribution in practice. The bottom-up strategies, comprising the oxidative and the reductive methods, have been widely utilized widespread. MnO2 NSs can be facilely prepared via the reduction of KMnO4 in the presence of an MES buffer at pH 6 or through the oxidation of MnCl2 with oxidants, eg, H2O2 in the coexistence of TMA·OH as summarized above. Numerous reductants can be selected, and the synthetic process for MnO2 NSs is tunable. Although many intriguing methods have been developed in this inspiring research field, it is still urgent to develop new facile and effective methods for the synthesis of high-quality MnO2 NSs.

Then, we provided an overview of the main applications of MnO2 NSs in biomedicine. MnO2 NSs can play multiple roles as nanozymes, nanocargos, fluorescence quenchers and activatable MRI probes. Hitherto, almost all of the reported biomedical applications have been based on these four fundamental functionalities and their roles are not dichotomies towards each other. Numerous researchers have focused on integrating MnO2 NSs into multiple modalities to explore increasingly novel uses in biomedicine.

Last but not the least, biosafety is one of the most concerning issues for the use of nanomaterials in biomedical employments before end-point clinical translation, despite the knowledge of the toxicity for MnO2 NSs are still very preliminary and limited. Therefore, the toxicity of MnO2 NSs should be systematically and comprehensively validated, especially in vivo. In addition, several intermediate metabolites accumulate in living organisms and cannot be easily degraded or detoxified, resulting in long-term toxicity issues, which should be further considered.

In the future, for MnO2 NS-related research, the biosafety should be considered first. Thus, green synthetic approaches are preferred for obtaining MnO2 NSs with controllable thicknesses, sizes and morphologies. The biomedical applications of MnO2 NSs have experienced markedly rapid advancement over the last few decades. However, the targets are relatively limited. Extra attention should be paid to integrating proper targeting aptamers/antigens/antibodies especially those that play important roles in cancer cell signaling pathways with MnO2 NSs. This will help to improve both the performance of biosensors and the efficacy of cancer theranostics based on MnO2 NSs. Furthermore, additional applications of MnO2 NSs such as PTT and imaging-guided combination therapy, should be considered to broaden their biomedical applications. As envisaged optimistically, the MnO2 NSs will provide promising opportunities for the realization of more advanced medical imaging. We also believe that this review may entice other scientists in multiple disciplines to join into this new but growing research field.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771904, 81502280), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province for the Excellent Young Scholars (BK20170054), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M601890, 177607), Qing Lan Project, the Peak of Six Talents of Jiangsu Province (WSN-112), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent (QNRC2016776), Six One Project of Jiangsu Province (LGY2018083) and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX18_0708).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mansouri A, Gattolliat C, Asselah T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and signaling in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:629–647. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fruman D, Chiu H, Hopkins B, Bagrodia S, Cantley L, Abraham R. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170(4):605–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McInnes I, Schett G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2328–2337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31472-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169(6):985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kis A, Coleman J, Strano M. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7(11):699–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer J, Hamwi S, Kröger M, Kowalsky W, Riedl T, Kahn A. Transition metal oxides for organic electronics: energetics, device physics and applications. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2012;24(40):5408–5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loh K, Ho D, Chiu G, Leong D, Pastorin G, Chow E. Clinical applications of carbon nanomaterials in diagnostics and therapy. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2018;30(47):e1802368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu W, Qiu G, Wang Y, Wang R, Ye P. Tellurene: its physical properties, scalable nanomanufacturing, and device applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:7203–7212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chimene D, Alge D, Gaharwar A. Two-dimensional nanomaterials for biomedical applications: emerging trends and future prospects. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2015;27(45):7261–7284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veeramani H, Aruguete D, Monsegue N, et al. Low-temperature green synthesis of multivalent manganese oxide nanowires. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013;1(1070–1074). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Layfield RA. Manganese(II): the black sheep of the organometallic family. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37(6):1098–1107. doi: 10.1039/b708850g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fei J, Cui Y, Yan X, et al. Controlled preparation of MnO2 hierarchical hollow nanostructures and their application in water treatment. Adv Mater. 2008;20:452–456. doi: 10.1002/adma.200701231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad AS. Green synthesis of nanocrystalline manganese (II, III) oxide. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2017;71:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2017.08.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoseinpour V, Ghaemi N. Green synthesis of manganese nanoparticles: applications and future perspective-A review. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;189(undefined):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo S, Dong S. Graphene nanosheet: synthesis, molecular engineering, thin film, hybrids, and energy and analytical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(5):2644–2672. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00079e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao M, Huang Y, Peng Y, Huang Z, Ma Q, Zhang H. Two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets: synthesis and applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(16):6267–6295. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00268a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Shan J, Zhang W, Su S, Yuwen L, Wang L. Recent advances in synthesis and biomedical applications of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Small. 2017;13(5):1602660. doi: 10.1002/smll.v13.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Zhang J, Hang X, et al. Half-metallicity in single-layered manganese dioxide nanosheets by defect engineering. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(4):1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rani A, Velusamy D, Kim R, et al. Non-volatile ReRAM devices based on self-assembled multilayers of modified graphene oxide 2D nanosheets. Small. 2016;12(44):6167–6174. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan H, Yan G, Zhao Z, et al. A smart photosensitizer-manganese dioxide nanosystem for enhanced photodynamic therapy by reducing glutathione levels in cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(18):5477–5482. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L, Song J, Song L, et al. Simultaneous fenton-like ion delivery and glutathione depletion by MnO-based nanoagent to enhance chemodynamic therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(18):4902–4906. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Chen X, Chai R, Xing C, Li H, Yin X. A magnetic/fluorometric bimodal sensor based on a carbon dots-MnO2 platform for glutathione detection. Nanoscale. 2016;8(27):13414–13421. doi: 10.1039/c6nr03129c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lhuillier E, Pedetti S, Ithurria S, Nadal B, Heuclin H, Dubertret B. Two-dimensional colloidal metal chalcogenides semiconductors: synthesis, spectroscopy, and applications. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48(1):22–30. doi: 10.1021/ar500326c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omomo Y, Sasaki T, Wang L, Watanabe M. Redoxable nanosheet crystallites of MnO2 derived via delamination of a layered manganese oxide. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(12):3568–3575. doi: 10.1021/ja021364p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kai K, Yoshida Y, Kageyama H, et al. Room-temperature synthesis of manganese oxide monosheets. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(47):15938–15943. doi: 10.1021/ja804503f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tae E, Lee K, Jeong J, Yoon K. Synthesis of diamond-shape titanate molecular sheets with different sizes and realization of quantum confinement effect during dimensionality reduction from two to zero. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(20):6534–6543. doi: 10.1021/ja711467g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oaki Y, Imai H. One-pot synthesis of manganese oxide nanosheets in aqueous solution: chelation-mediated parallel control of reaction and morphology. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(26):4951–4955. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng R, Xie X, Vendrell M, Chang Y, Liu X. Intracellular glutathione detection using MnO(2)-nanosheet-modified upconversion nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(50):20168–20171. doi: 10.1021/ja2100774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Xu K, Sun H, Yin S. One-step synthesis of single-layer MnO2 nanosheets with multi-role sodium dodecyl sulfate for high-performance pseudocapacitors. Small. 2015;11(18):2182–2191. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng J, Dong M, Ran B, et al. “One-for-All”-type, biodegradable prussian blue/manganese dioxide hybrid nanocrystal for trimodal imaging-guided photothermal therapy and oxygen regulation of breast cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(16):13875–13886. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b01365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng X, Lu L, Sun C. Green synthesis of three-dimensional MnO/graphene hydrogel composites as a high-performance electrode material for supercapacitors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(19):16474–16481. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b02354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Wang F, Ou P, et al. High efficiency and rapid degradation of bisphenol A by the synergy between adsorption and oxidization on the MnO@nano hollow carbon sphere. J Hazard Mater. 2018;360:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu X, Shen C, Zhang Z, Barrios E, Zhai L. Core-shell composite fibers for high-performance flexible supercapacitor electrodes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(4):4041–4049. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b12997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borysiewicz M, Ekielski M, Ogorzałek Z, Wzorek M, Kaczmarski J, Wojciechowski T. Highly transparent supercapacitors based on ZnO/MnO nanostructures. Nanoscale. 2017;9(22):7577–7587. doi: 10.1039/c7nr01320e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng X, Guo Y, Yin Q, et al. Double-exchange effect in two-dimensional MnO nanomaterials. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5242–5248. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan H, Zhao Z, Yan G, et al. A smart DNAzyme-MnO(2) nanosystem for efficient gene silencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(16):4801–4805. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng S, Xu C, Deng S, et al. Interface reconstruction with emerging charge ordering in hexagonal manganite. Sci Adv. 2018;4(5):eaar4298. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Zhao Z, Xia Z, Dai L. A metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10(5):444–452. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng F, Shen J, Peng B, Pan Y, Tao Z, Chen J. Rapid room-temperature synthesis of nanocrystalline spinels as oxygen reduction and evolution electrocatalysts. Nat Chem. 2011;3(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nchem.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu M, Liang T, Shi M, Chen H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem Rev. 2013;113(5):3766–3798. doi: 10.1021/cr300263a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia H, Cai Y, Lin J, et al. Heterostructural graphene quantum Dot/MnO nanosheets toward high-potential window electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2018;5(5):1700887. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang JS, Zhang YZ, Tao J, Sun YY, Zhu YN. Preparation and luminescent properties of SiO2-Sr(4)A1(14)O(25): eu2+,Dy3+/light conversion agent phosphor for anti-counterfeiting application. J Mater Sci-Mater El. 2018;29(13):10762–10768. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-9142-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Z, Song Y, Feng D, Sun Z, Sun X, Liu X. High mass loading MnO with hierarchical nanostructures for supercapacitors. ACS Nano. 2018;12(4):3557–3567. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b00621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu S, Li L, Liu J, et al. Structural directed growth of ultrathin parallel birnessite on β-MnO for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Nano. 2018;12(2):1033–1042. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhai T, Sun S, Liu X, Liang C, Wang G, Xia H. Achieving insertion-like capacity at ultrahigh rate via tunable surface pseudocapacitance. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2018;30(12):e1706640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee S, Wu L, Poyraz A, et al. Lithiation mechanism of tunnel-structured MnO electrode investigated by in situ transmission electron microscopy. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2017;29(43). doi:10.1002/adma.201703186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen X, Qian T, Zhou J, Xu N, Yang T, Yan C. Highly flexible full lithium batteries with self-knitted α-MnO2 fabric foam. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(45):25298–25305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue Y, Yang Z, Liu N, et al. A flexible integrated system containing a microsupercapacitor, a photodetector, and a wireless charging coil. ACS Nano. 2016;10(12):11249–11257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galbiati M, Barraud C, Tatay S, et al. Unveiling self-assembled monolayers’ potential for molecular spintronics: spin transport at high voltage. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2012;24(48):6429–6432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu M, Ren W, Jeong T, et al. Omnipotent phosphorene: a next-generation, two-dimensional nanoplatform for multidisciplinary biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(15):5588–5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, Wang Y, Huang G, Gao J. Cooperativity principles in self-assembled nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2018;118(11):5359–5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tonga G, Jeong Y, Duncan B, et al. Supramolecular regulation of bioorthogonal catalysis in cells using nanoparticle-embedded transition metal catalysts. Nat Chem. 2015;7(7):597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burton A, Thomson A, Dawson W, Brady R, Woolfson D. Installing hydrolytic activity into a completely de novo protein framework. Nat Chem. 2016;8(9):837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long L, Liu J, Lu K, et al. Highly sensitive and robust peroxidase-like activity of Au-Pt core/shell nanorod-antigen conjugates for measles virus diagnosis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16(1):46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang H, Li P, Yu D, et al. Unraveling the enzymatic activity of oxygenated carbon nanotubes and their application in the treatment of bacterial infections. Nano Lett. 2018;18(6):3344–3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan K, Xi J, Fan L, et al. In vivo guiding nitrogen-doped carbon nanozyme for tumor catalytic therapy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1440–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feng L, Dong Z, Liang C, et al. Iridium nanocrystals encapsulated liposomes as near-infrared light controllable nanozymes for enhanced cancer radiotherapy. Biomaterials. 2018;181:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu Y, Cheng H, Zhao X, et al. Surface-enhanced raman scattering active gold nanoparticles with enzyme-mimicking activities for measuring glucose and lactate in living tissues. ACS Nano. 2017;11(6):5558–5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J, Cao Y, Hinman S, et al. Efficient label-free chemiluminescent immunosensor based on dual functional cupric oxide nanorods as peroxidase mimics. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;100:304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagvenkar A, Gedanken A. Cu0.89Zn0.11O, A new peroxidase-mimicking nanozyme with high sensitivity for glucose and antioxidant detection. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(34):22301–22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qin L, Wang X, Liu Y, Wei H. 2D-metal-organic-framework-nanozyme sensor arrays for probing phosphates and their enzymatic hydrolysis. Anal Chem. 2018;90(16):9983–9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tao Y, Lin Y, Huang Z, Ren J, Qu X. Incorporating graphene oxide and gold nanoclusters: a synergistic catalyst with surprisingly high peroxidase-like activity over a broad pH range and its application for cancer cell detection. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2013;25(18):2594–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hui C, Liu M, Li Y, Brennan J. A paper sensor printed with multifunctional bio/nano materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57(17):4549–4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouyang H, Tu X, Fu Z, et al. Colorimetric and chemiluminescent dual-readout immunochromatographic assay for detection of pesticide residues utilizing g-CN/BiFeO nanocomposites. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;106:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Dong K, Liu Z, et al. Activation of biologically relevant levels of reactive oxygen species by Au/g-CN hybrid nanozyme for bacteria killing and wound disinfection. Biomaterials. 2017;113:145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yin W, Ma D, Yu J, et al. Synthesis of surface modification oriented nano-sized molybdenum disulfide with high peroxidase-like catalytic activity for H2O2 and cholesterol detection. Chemistry. 2018;24:15868–15878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu X, Wang Q, Zhao H, Zhang L, Su Y, Lv Y. BSA-templated MnO2 nanoparticles as both peroxidase and oxidase mimics. Analyst. 2012;137(19):4552–4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu J, Meng L, Fei Z, Dyson P, Jing X, Liu X. MnO nanosheets as an artificial enzyme to mimic oxidase for rapid and sensitive detection of glutathione. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;90:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen F, Bai M, Zhao Y, Cao K, Cao X, Zhao Y. MnO-nanosheet-powered protective janus DNA nanomachines supporting robust RNA imaging. Anal Chem. 2018;90(3):2271–2276. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li J, Cheng F, Huang H, Li L, Zhu J. Nanomaterial-based activatable imaging probes: from design to biological applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(21):7855–7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Dong X, Chen P. Biological and chemical sensors based on graphene materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(6):2283–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baldo M, Thompson M, Forrest S. High-efficiency fluorescent organic light-emitting devices using a phosphorescent sensitizer. Nature. 2000;403(6771):750–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prevo B, Peterman E. Förster resonance energy transfer and kinesin motor proteins. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(4):1144–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puchert R, Steiner F, Plechinger G, et al. Spectral focusing of broadband silver electroluminescence in nanoscopic FRET-LEDs. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12(7):637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pian Q, Yao R, Sinsuebphon N, Intes X. Compressive hyperspectral time-resolved wide-field fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat Photonics. 2017;11:411–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu Y, Qiu X, Lindbo S, et al. Quantum dot-based FRET immunoassay for HER2 using ultrasmall affinity proteins. Small. 2018;14(35):e1802266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salis F, Descalzo A, Benito-Peña E, Moreno-Bondi M, Orellana G. Highly fluorescent magnetic nanobeads with a remarkable stokes shift as labels for enhanced detection in immunoassays. Small. 2018;14(20):e1703810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang H, Li C, Liu X, Zhou X, Wang F. Construction of an enzyme-free concatenated DNA circuit for signal amplification and intracellular imaging. Chem Sci. 2018;9(26):5842–5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Melnychuk N, Klymchenko A. DNA-functionalized dye-loaded polymeric nanoparticles: ultrabright FRET platform for amplified detection of nucleic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:10856–10865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang D, Huang Z, Xiao H, Wu Z, Tang L, Jiang J. Protein scaffolded DNA tetrads enable efficient delivery and ultrasensitive imaging of miRNA through crosslinking hybridization chain reaction. Chem Sci. 2018;9(21):4892–4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qiu X, Guo J, Jin Z, Petreto A, Medintz I, Hildebrandt N. Multiplexed nucleic acid hybridization assays using single-FRET-pair distance-tuning. Small. 2017;13(25):1700332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Teunissen A, Pérez-Medina C, Meijerink A, Mulder W. Investigating supramolecular systems using Förster resonance energy transfer. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:7027–7044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dyla M, Terry D, Kjaergaard M, et al. Dynamics of P-type ATPase transport revealed by single-molecule FRET. Nature. 2017;551(7680):346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ji C, Lu Z, Xu Y, Shen B, Yu S, Shi D. Self-production of oxygen system CaO/MnO @PDA-MB for the photodynamic therapy research and switch-control tumor cell imaging. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:2544–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qu F, Pei H, Kong R, Zhu S, Xia L. Novel turn-on fluorescent detection of alkaline phosphatase based on green synthesized carbon dots and MnO nanosheets. Talanta. 2017;165:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Y, Jiang K, Zhu J, Zhang L, Lin H. A FRET-based carbon dot-MnO2 nanosheet architecture for glutathione sensing in human whole blood samples. Chem Commun (Camb). 2015;51(64):12748–12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yan X, Song Y, Zhu C, et al. Graphene quantum dot-MnO2 nanosheet based optical sensing platform: a sensitive fluorescence “Turn Off-On” nanosensor for glutathione detection and intracellular imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(34):21990–21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yuan J, Cen Y, Kong X, et al. MnO2-nanosheet-modified upconversion nanosystem for sensitive turn-on fluorescence detection of H2O2 and glucose in blood. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(19):10548–10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.You J, Jones P. Cancer genetics and epigenetics: two sides of the same coin? Cancer Cell. 2012;22(1):9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kasinski A, Slack F. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):849–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(12):861–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Honkanen S, Thamm A, Arteaga-Vazquez M, Dolan L. Negative regulation of conserved class I bHLH transcription factors evolved independently among land plants. Elife. 2018;7:e38529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen X, Wang L, Huang R, et al. Dgcr8 deletion in the primitive heart uncovered novel microRNA regulating the balance of cardiac-vascular gene program. Protein Cell. 2018;10:327–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sun Q, Tripathi V, Yoon J, et al. MIR100 host gene-encoded lncRNAs regulate cell cycle by modulating the interaction between HuR and its target mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:10405–10416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cesana M, Guo M, Cacchiarelli D, et al. A CLK3-HMGA2 alternative splicing axis impacts human hematopoietic stem cell molecular identity throughout development. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(4):575–588.e577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.El Harane N, Kervadec A, Bellamy V, et al. Acellular therapeutic approach for heart failure: in vitro production of extracellular vesicles from human cardiovascular progenitors. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(20):1835–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robertson A, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 2017;171(3):540–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xu R, Rai A, Chen M, Suwakulsiri W, Greening D, Simpson R. Extracellular vesicles in cancer – implications for future improvements in cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:617–638. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ozawa T, Kandimalla R, Gao F, et al. A microRNA signature associated with metastasis of T1 colorectal cancers to lymph nodes. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):844–848. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by modulating autophagy. Cell. 2017;170(3):548–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hall D, Cost N, Hegde S, et al. TRPM3 and miR-204 establish a regulatory circuit that controls oncogenic autophagy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(5):738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Song Y, Yan X, Ostermeyer G, et al. Direct cytosolic MicroRNA detection using single-layer perfluorinated tungsten diselenide nanoplatform. Anal Chem. 2018;90:10369–10376. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu C, Chen C, Li S, et al. Target-triggered catalytic hairpin assembly-induced core-satellite nanostructures for high-sensitive “Off-to-On” SERS detection of intracellular microRNA. Anal Chem. 2018;90:10591–10599. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ye S, Wang M, Wang Z, Zhang N, Luo X. A DNA-linker-DNA bifunctional probe for simultaneous SERS detection of miRNAs via symmetric signal amplification. Chem Commun (Camb). 2018;54(56):7786–7789. doi: 10.1039/c8cc02910e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dai W, Zhang J, Meng X, et al. Catalytic hairpin assembly gel assay for multiple and sensitive microRNA detection. Theranostics. 2018;8(10):2646–2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nelson P, Baldwin D, Scearce L, Oberholtzer J, Tobias J, Mourelatos Z. Microarray-based, high-throughput gene expression profiling of microRNAs. Nat Methods. 2004;1(2):155–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun X, Wang H, Jian Y, et al. Ultrasensitive microfluidic paper-based electrochemical/visual biosensor based on spherical-like cerium dioxide catalyst for miR-21 detection. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;105:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang P, Wu X, Yuan R, Chai Y. An “off-on” electrochemiluminescent biosensor based on DNAzyme-assisted target recycling and rolling circle amplifications for ultrasensitive detection of microRNA. Anal Chem. 2015;87(6):3202–3207. doi: 10.1021/ac504455z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kichemazova NV, Bukharova EN, Selivanov NY, Bukharova IA, Karpunina LV. Preparation, properties and potential applications of exopolysaccharides from bacteria of the genera xanthobacter and ancylobater. Appl Biochem Micro+. 2017;53(3):325–330. doi: 10.1134/S0003683817030073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li J, Li D, Yuan R, Xiang Y. Biodegradable MnO2 nanosheet-mediated signal amplification in living cells enables sensitive detection of down-regulated intracellular MicroRNA. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(7):5717–5724. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b13073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang K, Zeng M, Hu X, Guo B, Zhou J. Layered MnO₂ nanosheet as a label-free nanoplatform for rapid detection of mercury(II). Analyst. 2014;139(18):4445–4448. doi: 10.1039/c4an00649f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yuan Y, Wu S, Shu F, Liu Z. An MnO2 nanosheet as a label-free nanoplatform for homogeneous biosensing. Chem Commun (Camb). 2014;50(9):1095–1097. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47755j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhai W, Wang C, Yu P, Wang Y, Mao L. Single-layer MnO2 nanosheets suppressed fluorescence of 7-hydroxycoumarin: mechanistic study and application for sensitive sensing of ascorbic acid in vivo. Anal Chem. 2014;86(24):12206–12213. doi: 10.1021/ac503215z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Qi L, Yan Z, Huo Y, Hai X, Zhang Z. MnO nanosheet-assisted ligand-DNA interaction-based fluorescence polarization biosensor for the detection of Ag ions. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;87:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tan Q, Zhang R, Kong R, Kong W, Zhao W, Qu F. Detection of glutathione based on MnO nanosheet-gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles and target induced release of glucose measured with a portable glucose meter. Mikrochim Acta. 2017;185(1):44. doi: 10.1007/s00604-017-2586-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jalani G, Tam V, Vetrone F, Cerruti M. Seeing, targeting and delivering with upconverting nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:10923–10931. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yang Z, Cheng R, Zhao C, et al. Thermo- and pH-dual responsive polymeric micelles with upper critical solution temperature behavior for photoacoustic imaging-guided synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy against subcutaneous and metastatic breast tumors. Theranostics. 2018;8(15):4097–4115. doi: 10.7150/thno.26195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Langton M, Keymeulen F, Ciaccia M, Williams N, Hunter C. Controlled membrane translocation provides a mechanism for signal transduction and amplification. Nat Chem. 2017;9(5):426–430. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Niu D, Li Y, Shi J. Silica/organosilica cross-linked block copolymer micelles: a versatile theranostic platform. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(3):569–585. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00495d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yao C, Wang P, Li X, et al. Near-infrared-triggered azobenzene-liposome/upconversion nanoparticle hybrid vesicles for remotely controlled drug delivery to overcome cancer multidrug resistance. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2016;28(42):9341–9348. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Datz S, Illes B, Gößl D, Schirnding C, Engelke H, Bein T. Biocompatible crosslinked β-cyclodextrin nanoparticles as multifunctional carriers for cellular delivery. Nanoscale. 2018;10:16284–16292. doi: 10.1039/c8nr02462f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhang D, Yang J, Guan J, et al. In vivo tailor-made protein corona of a prodrug-based nanoassembly fabricated by redox dual-sensitive paclitaxel prodrug for the superselective treatment of breast cancer. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(9):2360–2374. doi: 10.1039/c8bm00548f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Behroozi F, Abdkhodaie M, Abandansari H, et al. Engineering folate-targeting diselenide-containing triblock copolymer as a redox-responsive shell-sheddable micelle for antitumor therapy in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2018;76:239–256. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu J, Zhang Y, Kahkoska A, Gu Z. Bioresponsive transcutaneous patches. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;48:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hu J, Chen Y, Li Y, Zhou Z, Cheng Y. A thermo-degradable hydrogel with light-tunable degradation and drug release. Biomaterials. 2017;112:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ji H, Dong K, Yan Z, et al. Bacterial hyaluronidase self-triggered prodrug release for chemo-photothermal synergistic treatment of bacterial infection. Small. 2016;12(45):6200–6206. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Timko B, Dvir T, Kohane D. Remotely triggerable drug delivery systems. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2010;22(44):4925–4943. doi: 10.1002/adma.201002072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Agrawal G, Agrawal R. Functional microgels: recent advances in their biomedical applications. Small. 2018;14:e1801724. doi: 10.1002/smll.v14.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.He Q, Kiesewetter D, Qu Y, et al. NIR-responsive on-demand release of CO from metal carbonyl-caged graphene oxide nanomedicine. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2015;27(42):6741–6746. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lukianova-Hleb E, Ren X, Sawant R, Wu X, Torchilin V, Lapotko D. On-demand intracellular amplification of chemoradiation with cancer-specific plasmonic nanobubbles. Nat Med. 2014;20(7):778–784. doi: 10.1038/nm.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang C, Seo S, Kim J, et al. Intravitreal implantable magnetic micropump for on-demand VEGFR-targeted drug delivery. J Control Release. 2018;283:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Andreeva D, Cherepanov P, Avadhut Y, Senker J. Rapidly oscillating microbubbles force development of micro- and mesoporous interfaces and composition gradients in solids. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;51:439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nguyen V, Ahmed A, Ramanujan R. Morphing soft magnetic composites. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2012;24(30):4041–4054. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhang D, Wei L, Zhong M, Xiao L, Li H, Wang J. The morphology and surface charge-dependent cellular uptake efficiency of upconversion nanostructures revealed by single-particle optical microscopy. Chem Sci. 2018;9(23):5260–5269. doi: 10.1039/c8sc01828f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lai W, Rogach A, Wong W. Molecular design of upconversion nanoparticles for gene delivery. Chem Sci. 2017;8(11):7339–7358. doi: 10.1039/c7sc02956j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wolfbeis O. An overview of nanoparticles commonly used in fluorescent bioimaging. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(14):4743–4768. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00392f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhao P, Zhu Y, Yang X, et al. Multifunctional MnO2 nanosheet-modified Fe3O4@SiO2/NaYF4: yb,Er nanocomposites as novel drug carriers. Dalton Trans. 2014;43(2):451–457. doi: 10.1039/c3dt52066h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Pykett IL, Newhouse JH, Buonanno FS, et al. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Radiology. 1982;143(1):157–168. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7038763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nitz WR. [Magnetic resonance imaging. Sequence acronyms and other abbreviations in MR imaging]. Radiologe. 2003;43(9):745–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Armstrong P, Keevil SF. Magnetic resonance imaging–1: basic principles of image production. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 1991;303(6793):35–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6793.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Terreno E, Castelli D, Viale A, Aime S. Challenges for molecular magnetic resonance imaging. Chem Rev. 2010;110(5):3019–3042. doi: 10.1021/cr100025t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhang S, Merritt M, Woessner D, Lenkinski R, Sherry A. PARACEST agents: modulating MRI contrast via water proton exchange. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36(10):783–790. doi: 10.1021/ar020228m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Duboc C. Determination and prediction of the magnetic anisotropy of Mn ions. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45(21):5834–5847. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00898k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Weinmann H, Brasch R, Press W, Wesbey G. Characteristics of gadolinium-DTPA complex: a potential NMR contrast agent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142(3):619–624. doi: 10.2214/ajr.142.3.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Schmidt-Lauber C, Bossaller L, Abujudeh H, et al. Gadolinium-based compounds induce NLRP3-dependent IL-1β production and peritoneal inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(11):2062–2069. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]