Abstract

Background.

Textbooks are a formative resource for health care providers during their education and are also an enduring reference for pathophysiology and treatment. Unlike the primary literature and clinical guidelines, biomedical textbook authors do not typically disclose potential financial conflicts of interest (pCoI). The objective of this study was to evaluate whether the authors of textbooks used in the training of physicians, pharmacists, and dentists had appreciable undisclosed pCoI in the form of patents or compensation received from pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies.

Methods.

The most recent editions of six medical textbooks: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (HarPIM), Katzung’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (KatBCP), the American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (AOAFOM), Remington’s The Science and Practice of Pharmacy (RemSPP), Koda-Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics (KKYAT), and Yagiela’s Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry (YagPTD) were selected after consulting biomedical educators for evaluation. Author names (N=1,152, 29.2% female) were submitted to databases to examine patents (Google Scholar) and compensation (ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs (PDD)).

Results.

Authors were listed as inventors on 677 patents (maximum/author = 23) with three-quarters (74.9%) to HarPIM authors. Females were significantly under-represented among patent holders. The PDD 2009-2013 database revealed receipt of 13.2 million $US, the majority to (83.9%) to HarPIM. The maximum compensation per author was $869,413. The PDD 2014 database identified receipt of 6.8 million with 50.4% of eligible authors receiving compensation. The maximum compensation received by a single author was $560,021. Cardiovascular authors were most likely to have a PDD entry and neurologic disorders authors were least likely.

Conclusion.

An appreciable subset of biomedical authors have patents and have received remuneration from medical product companies and this information is not disclosed to readers. These findings indicate that full transparency of financial pCoI should become a standard practice among the authors of biomedical educational materials.

Keywords: author, dentist, disclosure, medical education, pharmacist, pharmacotherapy

A Conflict of Interest (CoI) is a set of conditions in which professional judgement regarding a primary interest (e.g. care of a patient) may be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (e.g. economic gain) (Thompson 1993). As a result of several high-profile episodes (Feder 2005; Kearns et al. 2015, 2016; Harris 2009), the biomedical research culture has undergone a substantial transformation in the past two decades in how potential CoI are defined and the importance of disclosing a financial CoI (Bosch et al. 2013; Krimsky & Sweet 2009). Examination of over one thousand biomedical and scientific journals revealed that less than one-sixth had a CoI policy in 1997 (Krimsky & Rothenberg 2001) but almost all (99%) clinical biomedical journals required authors to disclose CoI in 2014 (Shawwa et al. 2016). Similarly, only a small-minority (3.7%) of clinical practice guidelines from 1979-1999 disclosed CoI (Papanikolaou et al. 2001). However, over one-third (34.8%) of clinical practice guidelines made CoI information publically available in 2010 (Norris et al. 2012). Interestingly, the American Society of Clinical Oncology requires presenters disclose all financial CoIs and not just the ones deemed relevant (Boothby et al. 2016). Recognition of the importance of CoI transparency is not limited to empirical reports, oral presentations, and guidelines, but also reviews, meta-analyses, and other highly-influential materials (Cosgrove & Krimsky 2012; Roseman et al. 2011).

Biomedical textbooks also have the potential to be influential for health care providers as these are read not just during their formative professional development years but are often enduring references (Davies et al. 2007). These educational cornerstones include recommendations for treatments. Further, the breadth of how a disease is defined could substantially impact how often treatment is appropriate. Previously, potential CoIs among the authors of four textbooks that are used in the training of physicians (MD), pharmacists, and pharmacologists were examined. Over one-quarter (26.2%) of the authors in Goodman and Gilman’s textbook (Brunton et al. 2011) had an undisclosed patent. Almost one-third (30.4%) of the authors had received money from a pharmaceutical company which was undisclosed to readers. Research accounted for less than one-quarter (23.9%) of support which trailed both speaking (28.3%) and consulting (27.0%). Males and academic physicians (MD/PhDs) had a significantly greater likelihood of CoIs than either females or pharmacist authors (Piper et al. 2015).

The objective of this line of research was to determine if the authors and editors of influential biomedical information resources have appreciable pCOIs in the form of patents or compensation from pharmaceutical companies. The goals of the present report are two-fold. First, to examine the pCoIs of authors of textbooks used in the education of health professionals weWe will expand upon the earlier paper by Davies et al (2007) by examining additional textbooks used in the training of allied health professionals (osteopaths and dentists). Second, we conducted exploratory analyses to further describe the author characteristics (e.g. gender) that are associated with undisclosed financial CoI. ProPublica’s Dollar’s for Docs (PDD) (Ornstein et al. 2016) database has been used previously to quantify pCoIs (Norris et al. 2012, Piper et al. 2015) but this only covered seventeen pharmaceutical companies for 2009-2013. The new PDD database includes more pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers.

Methods

Sample:

We used the following procedures to identify textbooks for our sample. First, we emailed about fifty educators at various professional schools to identify which book(s) they use most often and less than one-third responded. Second, among the textbooks identified, textbooks that had undergone multiple editions were selected assuming they are standard texts. Third, textbooks that were not edited by US authors were excluded as PDD is limited to U.S. authors. Finally, textbooks that did not focus on clinical interventions were excluded. As a result of this process six textbooks were identified:

Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (Kasper et al. 2015, HarPIM)] is an authoritative medical teaching text. Regarded as the bible of internal medicine, it comprehensively reviews disease states including pathophysiology, diagnosis, clinical trials, treatment, and monitoring. The two-volumes are further divided into nineteen Parts (e.g. Infectious Diseases, Oncology/Hematology).

Katzung and Trevor’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (Katzung and Trevor 2014, KatBCP)(Katzung & Trevor 2014)is an accessible pharmacology textbook A prior investigation examined the 12th edition (Piper et al. 2015), therefore the 13th edition was evaluated here.

American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (Chila 2010, AOAFOM)is considered the comprehensive standard in the field of Osteopathic Medicine, covering multiple topics from the basic sciences to primary care to coding and billing.

Remington’s The Science and Practice of Pharmacy (Allen et al. 2012, RemSPP), is regarded as the bible of pharmacy education. The 22nd edition covers most aspects of pharmacy practice, including pharmaceutical calculations, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, patient care, and pharmacy law.

Koda-Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs (Alldredge et al. 2012, KKYAT)Kis a foundational pharmacotherapy text discussing evidence-based drug therapy for a wide variety of disease states and disorders.

Yagiela’s Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentists (Yagiela 2010, YagPTD) focuses on drugs used for providing dental care (antibiotics, analgesics, and anesthetics), and the impact of drugs on oral health.

A list of authors/editors was compiled based on the “Contributors” section and inspection of each chapter. Author/editor names were entered into the following databases to identify patents associated with each:

Google Scholar:

Names were entered into Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) with the checkbox “include patents” selected. As many authors contributed to earlier textbook editions, patents dated from 2000-present (early 2016) published in English were included. If the location listed on the patent was not within the same state, or within a commuting proximity, as in the textbook, prior institutional affiliations were determined by examining publications. For the present purposes, “patent” is inclusive of both applications and awarded patents as both could contribute to CoI. Patents and inventor affiliations were verified with a second database (freepatentsonline.com).

ProPublica Dollars for Docs (PDD):

The non-profit organization ProPublica maintains two PDD databases of remuneration in the US. The first, PDD09 (projects.propublica.org/d4d-archive), covers 4 billion in U.S. dollars in support distributed from seventeen pharmaceutical companies to health care providers from 2009-2013. The checkbox “Show only payments over $250” was turned off to increase the likelihood of identifying even modest pCoIs although analyses were also conducted examining the percent of authors that had been compensated above this cutoff as there are thresholds that may adversely impact recipient trust (Green et al. 2012). The second database, PDD14 (projects.propublica.org/docdollars) covers 8/2013 to 12/2014 for 1,565 pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers for compensation (3.5 billion) for promotional speaking, consulting, meals, travel and research to medical doctors, osteopaths, dentists, and chiropractors. This information is mandated by the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, a part of the Affordable Care Act, and is reported to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS 2013). Pharmacists, PAs, NPs, and biomedical scientists are not currently covered by the Sunshine Act. The Open Payments System has been the source for many recent investigations (Ahmed et al. 2016a, 2016b). We elected to use the PDD databases because they cover a broader period than the CMS database.

The IRB of Bowdoin College concluded that this project did not meet the federal definition of human research and review was unnecessary.

Data Analysis

Data-analysis was completed with Systat, version 13.1 and figures were prepared with GraphPad Prism, version 6.07. The primary analysis was to quantify the pCoIs for each textbook in the form of compensation and patents. Central tendency of compensation ($USD) was expressed as both the mean and median as this measure was skewed. The SD was used to report variability. Compensation was shown for the top ten authors for PDD09 and PDD14. Authors whose primary affiliation was outside of the U.S. (7.1% of all authors) and PhDs (non-clinicians who are not included in PDD, 12.7% of all authors), were excluded from the denominator for percentage calculations. Only prescribers were included in the denominator of percentage calculations for PDD14. Similarly, textbooks where many authors were PharmDs were not submitted to PDD14.The dependent measures for the patent search were the percent of authors with ≥1 patent and total patents. Analyses were completed both unweighted and weighted for multiple contributions (i.e. an author that contributed to more than one chapter). Each unique contributor counted once in the unweighted analysis. An author would have one spreadsheet row for every chapter that they contributed to in the weighted calculation. Editors or members of the editorial board (RemSPP) had one row for their role as editor and another for each chapter they authored. Exploratory analyses were conducted to determine if author characteristics (gender, as reported by: npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov, Part of HarPIM contributed for Parts with ≥20 authors) were associated with pCoIs.

Results

1. Author Characteristics

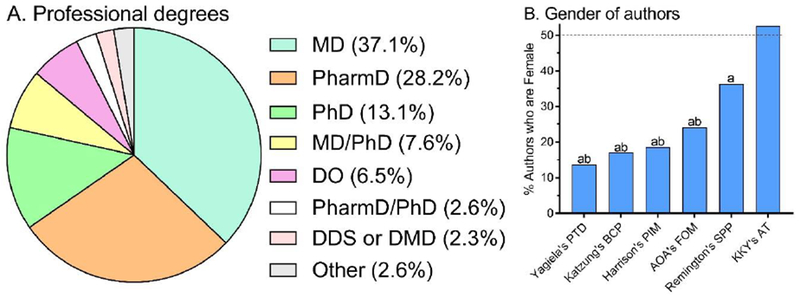

A total of 1,473 authors/editors were identified of which 320 contributed to multiple chapters. One-hundred and five authors/editors were excluded from PDD analysis because there were not affiliated with a US institution. A total of 904, 552, and 1,153 unique authors/editors were entered into PDD09 , PDD14, and the patent searches, respectively. The basic demographic characteristics of the authors/editors, including their professional degrees, is depicted in Figure 1A. Of note, textbooks used in the training of pharmacists (KKYAT=52.6%, RemSPP=36.3%) had significantly more female contributors than other books (KatBCP=17.1%, YagPTD=13.7%) (See Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Author characteristics. Highest academic degrees of all authors (A, N = 1,127). Percent authors in each book that are female (B). Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry (PTD), Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (BCP), Principles of Internal Medicine (PIM), American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (AOA’s FOM). ap < .0001 versus Koda-Kimble & Young’s Applied Therapeutics (KKY’s AT); bp < .05 versus Remington’s Science and Practice of Pharmacy (SPP).

2. Patents

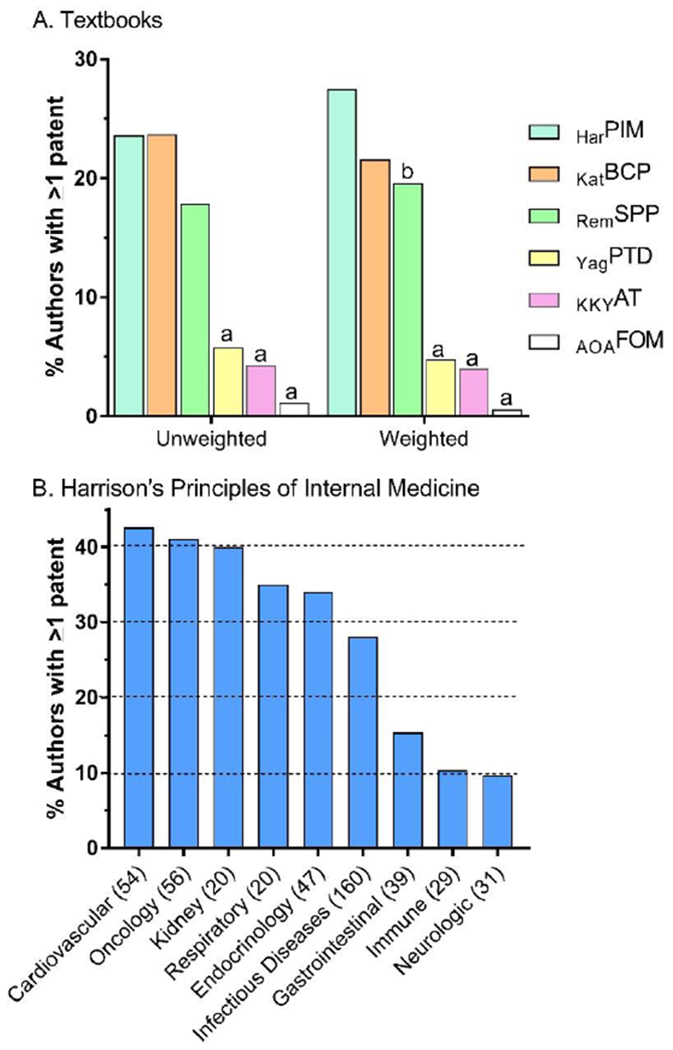

The authors/editors of the six textbooks, containing 772 chapters, collectively held 677 patents (or 1,090 in the weighted analysis, 1.41 patents/chapter). Table 1 shows example patent titles and the correspondence with the chapter title. Almost two-thirds of patents (65.7%) were to HarPIM authors. Further, the editors of HarPIM held 40 patents or five-fold more than the editors of the all other textbooks combined. Figure 2 shows the percent of authors of each textbook that had received at least one patent. Approximately one out of every five authors of HarPIM, KatBCP, and RemSPP, versus one out of every twenty authors for AOAFOM, KKYAT, and YagPTD held a patent. Figure 2A shows this pattern with the percent of HarPIM, KatBCP, and RemSPP authors with at least one patent was significantly greater for each textbook as compared to AOAFOM, KKYAT, or YagPTD. The pattern was similar for the unweighted and weighted data for multiple author contributions with the exception that patents held by HarPIM (27.5%) authors exceeded RemSPP (19.6%) authors in the weighted analyses (χ2(1)=6.00, p<.05). Notably, the single patent holder for AOAFOM was a biomedical scientist (i.e. a PhD) and a similar pattern was evident for RemSPP and YagPTD. More specifically, among 108 patents to REMSPP authors, few (16.7%) belonged to a PharmD/RPh.

Table 1.

Example patent (P) and textbook chapter (C) titles. Contributor to: HarHarrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, KatKatzung & Trevor’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology; RemRemington’s Science & Practice of Pharmacy; KKYKoda-Kimble & Young’s Applied Therapeutics. eEditor. Note to reviewers: This table contains author initials for review purposes. If the reviewers or editors prefer, author identity could be further obscured by removing this information.

| Author (initials): | Titles |

|---|---|

| KCA, MDHar | P: Treatment of Multiple Myeloma; C: Plasma Cell Disorders |

| JAB, MDHar | P: Methods for treating inflammatory disorders; C: Allergies, Anaphylaxis, and Systemic Mastocytosis |

| SBC, MDHar | P: Bacterial strain typing; C: Acute Infectious Diarrheal Diseases and Bacterial Food Poisoning |

| AMKC, MDHar | P: Carbon monoxide as a biomarker and therapeutic agent; C: Approach to the Patient with Disease of the Respiratory System |

| CAC, MD PhDHar | P: System and method for monitoring information related to sleep; C: Sleep Disorders |

| ASF, MDE,Har | P: Efficient inhibition of hiv-1 viral entry through a novel fusion protein including of cd4; C: Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease: AIDS and Related Disorders |

| DNG, MDHar | P: Methods and compositions for prevention and treatment of clostridium difficile-associated diseases; C: Clostridium difficile Infection, Including Pseudomembranous Colitis |

| PJK, MDHar | P: Imaging, diagnostic, and therapeutic device and methods of use thereof; C: Diseases of the Esophagus |

| DLK, MDE,Har | P: Immunomodulating compounds and related compositions and methods; C: Approach to the Patient with an Infectious Disease |

| SK, MDHar | P: Methods and materials for reducing bone loss; C: Hypercalcemia and Hypocalcemia |

| KTM, MDHar | P: Penile prosthesis; C: Sexual Dysfunction |

| VIR, MDHar | P: Methods for treating bipolar mood disorder associated with markers on chromosome 18q; C: Mental disorders |

| HE, MDKat | P: Methods and compositions for the treatment of pain; C: General Anesthetics |

| AJP, PhDKat | P: Composition and methods to treat cardiac diseases; C: Cholinoceptor-Activating & Cholinesterase-Inhibiting Drugs |

| VK, MSRem | P: Process for manufacturing opioid analgesics; C: Dissolution |

| PM, PhDRem | P: Drug delivery device; C: Ophthalmic preparations |

| FTA, PharmDKKY | P: Providing patient-specific drug information; C: Dosing of drugs in renal failure |

Figure 2.

Percent of authors with ≥ 1 patent by textbook unweighted and weighted for authors with multiple-contributions (A) and by Part within Harrison’s Principles of Internal of Medicine HarPIM. ap < .05 versus HarPIM, Katzung’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (KatBCP), and Remington’s Science and Practice of Pharmacy (RemSPP). bp < .05 versus HarPIM. Yagiela’s Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentists (YagPTD), Koda-Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics (KKYAT), American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (AOAFOM).

As the largest single textbook (almost three-times more chapters than the next longest book), further analyses were completed within HarPIM. There was no significant difference in the percent of male (23.6%) versus female (16.1%) HarPIM authors that had at least one patent (p=.069). However, this gender difference was significant in the analyses that accounted for multiple author contributions (Males=29.8%, Females=15.5%, p<.005). The percentage of authors with at least one patent by HarPIM Part was evaluated. Figure 2B shows a four-fold difference among the HarPIM Parts with the Cardiovascular System (42.6%) and Oncology and Hematology (41.1%) ranking highest and Immune-mediated (10.4%) and Neurologic Disorders (9.7%) ranking lowest.

3. Compensation as reported to PDD 2009 to 2013

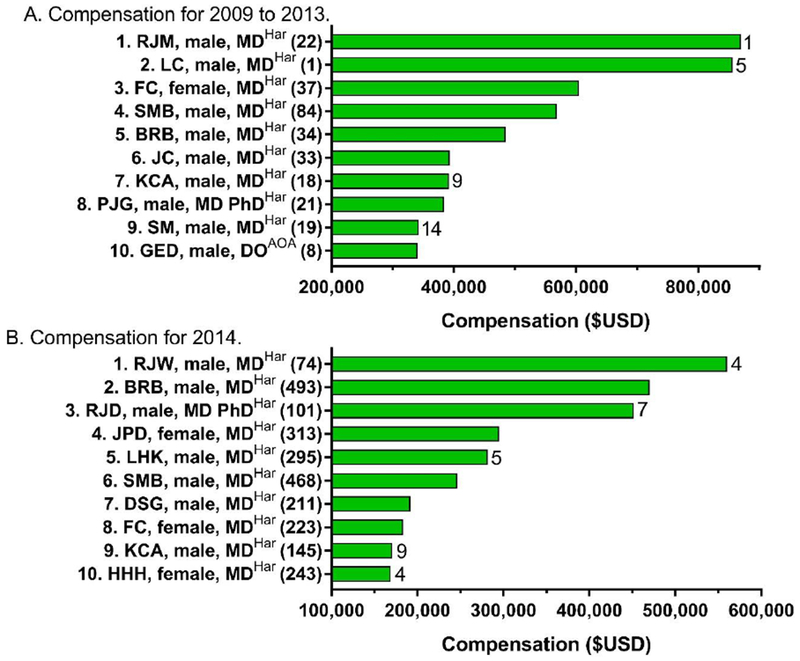

The next analyses evaluated compensation from pharmaceutical companies. Figure 3A shows the compensation received from 2009-2013 as reported to PDD in 277 payments (Min=$2, Max=$856,067) to the top ten authors. The highest compensated individual author received $869,353 with 95.2% for research and 4.2% for consulting. Four of the ten most highly compensated authors were oncologists (or list their primary affiliation with an organization focused on cancer), two were neurologists, two were endocrinologists, one was a gastroenterologist, and one was a DO certified in internal medicine. HarPIM accounted for 41.8% of all authors but nine of the top ten most compensated. Women authored 28.7% of all chapters but the top ten included only one woman. The top ten most compensated were also inventors on 29 patents.

Figure 3.

Top ten highest compensated authors as reported to ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs (https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/) for 2009 to 2013 (A) or from 8/2013 to 12/2014 (B). Author initials are listed followed by their gender. The textbook each author contributed to, either Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (Har) or the American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (AOA) is listed in superscript. Number of payments awarded to each author is in parentheses. Patents are listed to the right of each bar.

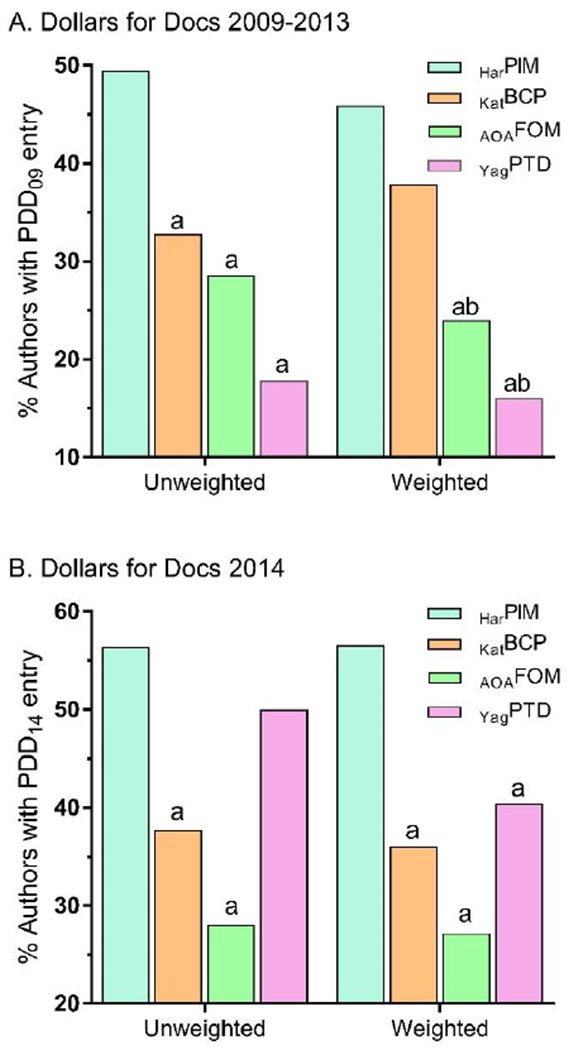

Collectively, authors reported receipt of $13.20 million ($15.95 million in the weighted analysis), most ($11.07 million or 83.9%) to HarPIM. Figure 4A compares textbooks and shows that half (49.5%) of the HarPIM authors had a PDD09 entry which was statistically greater than the other books in the unweighted analysis (not shown: KKYAT=11.1% and RemSPP=3.7%). The KatBCP (37.9%) authors were more significantly likely to have an entry than either AOAFOM (24.0%) or YagPTD (16.1%) in the weighted analysis. Using a more conservative threshold of >$250, HarPIM (37.8%) exceeded YagPTD (10.7%, p<.0001) and AOAFOM (10.1%, p<.0001). Similarly, KatBCP authors were more likely to have an entry (35.0%) than YagPTD (p<.0001) or AOAFOM (p<.0001). Among authors with a PDD09 entry, the median amount received was $6,000 ($1,500/year) with KatBCP ($8,296) exceeding HarPIM ($7,500). Further, HarPIM (Mean=$56,842±129,919) was higher than KatBCP ($22,905±30,203, t(117.9)=2.95, p<.005), and AOAFOM ($19,916±73,374, p≤.05). In the weighted analysis, HarPIM ($54,054±132,778) was greater than KatBCP ($24,872±24,872, p<.005) and YagPTD ($13,864, p<.0005).

Figure 4.

Percent of authors with a ProPublica Dollars for Docs (PDD, https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/) entry unweighted and weighted for authors with multiple-contributions, for 2009 to 2013 (A) or from 8/2013 to 12/2014 (B). Harrison’s Principles of Internal of Medicine HarPIM, Katzung’s Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (KatBCP), American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (AOAFOM), or Yagiela’s Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentists (YagPTD). ap < .05 versus HarPIM, ap < .05 versus KatBCP.

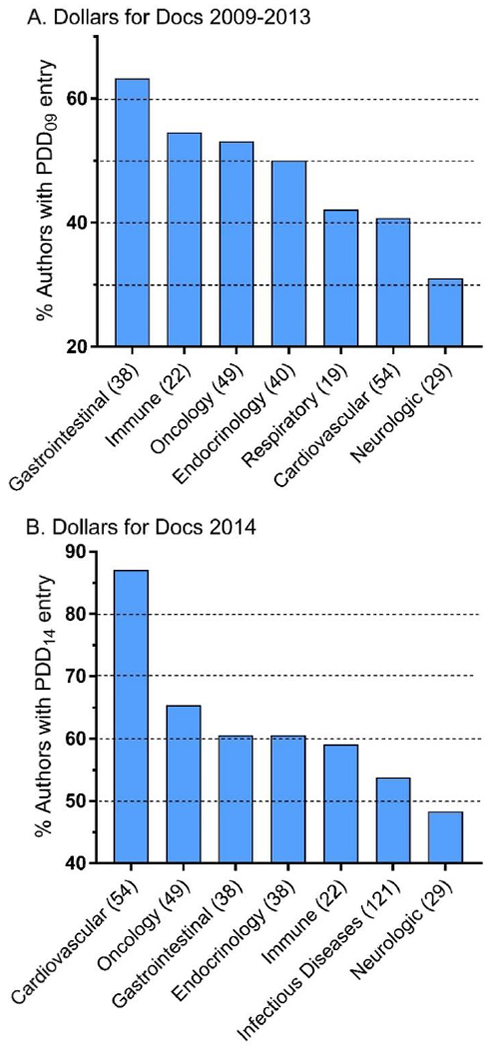

Further analyses were conducted within HarPIM data. Figure 5A shows the percent of authors that had an entry in PDD09 (i.e. that had received >$250 in compensation), by Part. Authors of the Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System (63.2%) were twice as likely as Neurologic Disorders (31.0%) authors to have an entry. Men were not significantly more likely to have a PDD09 entry (45.2%) than women (38.3%).

Figure 5.

Percent of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine authors with a ProPublica Dollars for Docs (PDD, https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/) entry by Part, ranked, for 2009 to 2013 (A) or from 8/2013 to 12/2014 (B). Number of authors of each Part is in parentheses.

4. Compensation as reported to PDD in 2014

These final analyses examine compensation from pharmaceutical and medical device companies. Figure 3B depicts the compensation received in 2014 as reported to PDD via 2,566 payments to the top ten highest compensated authors. The highest compensated individual author received $560,021 over seventeen months ($32,942/month) with 90.2% for consulting and 9.4% for travel. HarPIM authors were listed as all ten of the top ten and 44 of the top 50 highest compensated authors. The ten most compensated authors included three women. These highest compensated included two oncologists, two neurologists, one pediatrician, and one geneticist as well as two others whose research has an emphasis on genetics. Four individuals from Figure 3A were also retained in Figure 3B. The top ten were listed as inventors on 29 patents.

Figure 4B compares textbooks for the percentage of authors with a PDD13 entry and shows that HarPIM exceeded KatBCP and AOAFOM in both the weighted and unweighted analysis. Among PDD14 recipients, the median compensation for HarPIM authors was $4,848 or $3,422/year. Average payment amount for HarPIM contributors ($28,320±70,485) was greater than KatBCP ($14,182±19,770, p<.05) and AOAFOM ($706±1,502, p<.0005). In the weighted analysis, HarPIM contributors ($27,286±62,176) had higher compensation than KatBCP ($13,577±17,544, p<.005) and AOAFOM ($503±1,204, p<.0005) authors. Further, YagPTD ($24,064±39,100) was greater than AOAFOM (p<.05).

Figure 5B shows the percent of authors that had an entry in PDD14 by HarPIM Part. Cardiovascular authors (87.0%) were over twenty percent higher than the next Part (Oncology/Hematology=65.3%) and almost forty percent greater than Neurologic Disorders (48.3%). The percentage of men with a PDD14 entry (55.3%) was not significantly higher than women (50.0%).

Discussion

Unlike the primary literature and meta-analyses by reputable organizations like the Cochrane library, it is not currently a common practice for authors to disclose their financial CoI in textbooks. This study evaluated whether over one thousand contributors to textbooks used in the education of allopathic and osteopathic physicians, pharmacists, and dentists had patents or received sufficient compensation from pharmaceutical or medical device companies to an extent that such a policy would be warranted. The answer is a clearly in the affirmative.

Patents were not equally common among the half-dozen textbooks evaluated. There were two distinct groups of textbooks with almost one-quarter of allopathic medicine (HarPIM and KatBCP) authors receiving at least one patent. Patents were uncommon (<6%) among authors and editors for the education of osteopaths and dentists (i.e. AOAFOM and YagPTD). Historically, osteopathic medicine has differed from allopathic medicine with a greater emphasis on primary care (Shannon and Teitelbaum 2009). Osteopathic schools typically have modest research portfolios (Chen and Mullan 2009) which might result in less infrastructure such as intellectual property attorneys to support patent applications. Dentistry has substantial potential for CoIs which has been well documented for research (Brignardello-Petersen et al. 2013; Kearns et al. 2015) but the infrequency of patents was unanticipated. The prevalence of patents was not uniform within the two textbooks used in the education of doctors of pharmacy. Within KKYAT, many of the patents were to non-pharmacist authors. Inspection of the patent titles for KKYAT reveals an emphasis on pharmaceuticals which is also a focus of that textbook. Overall, based on this investigation and Piper et al. 2015, textbook contributors may form two distinct groups: 1) clinicians who are also academic educators, and 2) biomedical scientists who are researchers and inventors.

Examination of which Parts of HarPIM had the most patents revealed an interesting ranking. Heart disease and cancer rank first and second, respectively, for leading causes of death in the US (CDC 2016) and cardiology and oncology were similarly ranked for patents. Examination of PDD2014 showed that cardiovascular and oncology again had top rankings. However, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease rank fifth and sixth, respectively, and suicide ranks tenth. The Neurologic Part, which includes psychiatric disorders, was ranked last for patents (Figure 2B). Patents associated with the diagnosis or treatment of psychiatric disorders, with the exception of obesity and sleep, were uncommon. Similarly, Neurologic Disorders ranked last for entries in the PDD09 and PDD14 databases. Although the reputation of psychiatry may have been tarnished by frequent CoIs (Cosgrove et al. 2014), or difficulties with disclosure (Thacker 2009), these findings do not indicate that academic psychiatrists or neurologist authors are elevated in their listing in the Open Payment database or in patents. The proportion of U.S. neurologists and psychiatrists listed in the Open Payment system is approximately average (Marshall et al. 2016a). Together, these findings are broadly concordant with authors of chapters on more widespread conditions or diseases also having more undisclosed patents.

The finding that an appreciable subset of textbook authors have patents or were compensated from pharmaceutical/medical device companies should be placed in a comparative context. Over half (56%) of the authors of seventeen clinical practice guidelines in cardiology had a CoI (Mendelson et al. 2011). Over three quarters of physicians specializing in cardiovascular diseases or neurosurgery in the U.S. received compensation from medical product manufacturers in 2013 (Marshall et al. 2016a). Similarly, half (49.1%) of non-oncology physicians in the US were listed in the Open Payments system for 2014 which was lower than the almost two-thirds (63.0%) of medical oncologists (Marshall et al. 2016b).

Although not the primary objective of this report, several gender differences were identified. A textbook geared toward biomedical scientists and physicians (Brunton et al. 2011), had fewer female authors (11.2%) than a commonly utilized book written by, and for, pharmacists (52.6%) (Piper et al. 2015). This pattern was verified and extended with textbooks for pharmacists having more female authors than those for allopathic and osteopathic physicians or dentists. Perhaps not coincidentally, less than one third of all editors were female. As the invitation to contribute a chapter is an honor typically reserved for established professionals, the under-representation (<50%) of women in the majority of textbooks examined may be reflective of broader gender disparities in academic career advancement (Draugalis et al. 2014; Mayer et al. 2014; Sklar 2015; Whelton & Wardman 2015). Similarly, being awarded a patent is an important achievement. Compensation from industry, particularly for research and consulting, represents the sequelae of extensive training and expertise which may advance and benefit patient care. A prior investigation of biomedical authors also determined that females were several fold less likely to be patent holders. However, many female authors were PharmDs and pharmacists were also less likely than others to be patent holders (Piper et al. 2015). The deficit of female inventors in the weighted analysis within HarPIM, where the author’s credentials were more uniform, is congruent with and reinforces prior findings (Piper et al. 2015; Reddy et al. 2016).

There are some limitations and caveats to this investigation. First, we are not suggesting that all pCoIs identified were relevant (although see Table 1). Although it is known that health care providers who receive compensation from pharmaceutical companies are more likely to prescribe those companies’ products (DeJong et al. 2016; Fleischman et al 2016a; Taylor et al. 2016; Wood et al. 2017; Yeh et al. 2016), our findings do not necessarily suggest that payments by pharmaceutical manufacturers or patents adversely impacted the textbook content (e.g. presentation of material that is inconsistent with evidence based medicine). Although evaluating textbook content versus pCOI is outside the scope of this paper, it is an opportunity for further research. Second, the patents identified may be an underestimation of their true number. Some authors did not use a middle initial, which impeded the search process. Some authors switch affiliations over the course of their careers and some patents that listed an earlier affiliation in a different state were likely missed. Clearly, identification of patents, even with two databases, is an imperfect process and would benefit from a unique identification number for each inventor. The presence of a patent, or patent application, at the time a chapter was written, provides no information about whether the inventor received any proceeds. Third, PDD09 is only as complete as the information reported by the pharmaceutical companies. Similarly, the data from PDD14 is only as accurate as that which was reported to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and has been criticized (Babu et al. 2016). Clearly, although many pCoIs were identified, the authors themselves should also regularly provide CoI information, including about investments that they or their immediate family members own, in order to maintain the trust that educators and future health care providers have in these resources. Fourth, the presence of a financial pCoI (i.e. top ten lists like Figure 4) should not be interpreted to stigmatize or tarnish the reputation of a health care provider. Innovation thrives in an environment of close relationships between industry and providers. It is appropriate for providers to be fairly compensated for innovations that enhance health outcomes. Finally, although a large number of authors were examined and some of the textbooks evaluated have a distinguished history, further research with electronic resources (e.g. UpToDate) may be needed. Unfortunately, the Sunshine Act does not currently cover veterinarians or many mid-level providers that have prescription authority (Wood et al. 2017). Although the Sunshine Act has been successful in stimulating many investigations and facilitating transparency for cardiothoracic surgeons (Ahmed et al. 2016a), neurosurgeons (Babu et al. 2016), orthopaedic surgeons (Cvetanovich et al. 2015), plastic surgeons (Chao & Gangopadhyay 2016), transplant surgeons (Ahmed et al. 2016b), emergency physicians (Fleischman et al. 2016b), obstetrician-gynecologists (Thompson et al. 2016), oncologists (Jairam & Yu, 2016; Marshall et al. 2016b), ophthalmologists (Reddy et al. 2016; Taylor et al. 2016), otolaryngologists (Rathi et al. 2015), pediatricians (Karas et al. 2017), and others (Jarvies et al. 2014; Marshall et al. 2016a, Wood et al. 2017), future research will be necessary to determine if a by-product of the Sunshine Act, or other similar laws internationally (Pepitone and Sharkey 2016), has been the reduction of compensation to doctors for non-research activities.

We have some suggestions for textbook editors considering strategies for how to improve CoI transparency. First would be regularly obtaining, and sharing, complete pCoI information using the International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (Drazen et al. 2010) or another standardized form, for all authors and editors. Electronic resources like PDD are sufficiently user friendly that a “trust, but verify” approach by the highly interested reader should be possible. A small subset (≈5% of RemSPP) of authors had an industrial affiliation. There is nothing even slightly untoward about this. A subset of readers might be very interested that the author of a chapter titled “Ectoparasite Infestations and Arthropod Injuries” is also the President and Chief Scientific Officer for IdentifyUS, a company whose specialty is to identify and manage pest problems. Unlike others (Cosgrove et al. 2014; Kearns et al. 2016), we are not currently advocating that only individuals without CoIs should be eligible to contribute reviews, clinical guidelines, or author educational materials. Our second recommendation is it would be easier for readers to reach their own conclusion about the importance of a contributor’s affiliation when this information is listed at the beginning of each chapter rather than within a separate “Contributors,” or other, section.

Our final recommendation is to view full CoI disclosure as only an important first step. The author of a highly influential psychopharmacology textbook (Stahl 2015) lists a team of reviewers in the Acknowledgements. One responsibility of reviewers with sufficient expertise in a content area could be to evaluate pCoIs and compare this to the presentation of material where the contributor has an economic interest. Although greater transparency of CoIs is needed, the appropriate management of CoIs is integral for maintaining the audience’s trust.

In conclusion, many authors of medical and allied health professions cornerstone texts have significant undisclosed CoIs. We recommend publishers and editors implement disclosure requirements similar to those present in journal article publications in order to maintain confidence in biomedical textbooks. The influence of these CoIs is unclear and further research is warranted to determine if the content of the texts was impacted.

Acknowledgements:

Lillian A. Eckstein and Carly Lappas provided technical support. Melissa A. Birkett, PhD, and Joseph Fraiman, MD, provided feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. The ProPublica organization is acknowledged for the Dollars for Docs database. This report is based on the analysis of the authors and does not reflect the opinions of our respective institutions.

Role of funding source: This study was conducted with software provided by Husson University School of Pharmacy and NIEHS (T32-ES007060-31A1) and supported by Bowdoin College. Funders had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations:

- AOAFOM:

American Osteopathic Association’s Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine

- CoI:

conflict of interest

- DSM:

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- HarPIM:

Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine

- KatBCP:

Katzung’s Basic & Clinical Pharmacology

- KKYAT:

Koda-Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics

- PDD:

ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs

- RemSPP:

Remington’s The Science and Practice of Pharmacy

- YagPTD:

Yagiela’s Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: BJP has received travel support from the Wellness Connection of Maine and research support from the Center for Wellness Leadership, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, and is a Fahs-Beck Fellow. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL: This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Husson University and Bowdoin College.

References

- Ahmed R, Bae S, Hicks CW, et al. (2016a). Here comes the sunshine: Industry’s payments to cardiothoracic surgeons. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 103(2): 567–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R, Chow EK, Massie AB, et al. (2016b). Where the sun shines: Industry’s payments to transplant surgeons. American Journal of Transplantation 16(1): 292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alldredge BK, Corelli RL, Ernst ME, et al. 2012. Koda-Kimble & Young’s Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs (10th edition), Philadelphia, PA: LWW. [Google Scholar]

- Allen LV, Adejar A, and Dessele SP. 2012. Remington: The Science & Practice of Pharmacy (22nd edition), New York, NY: Pharmaceutical Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Osteopathic Association and Chila A 2010. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine (3rd edition), Philadelphia: PA: LWW. [Google Scholar]

- Babu MA, Heary RF, and Nahed BV. 2016. Does the Open Payments Database provide sunshine on Neurosurgery? Neurosurgery 79(6): 933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby A, Wang R, Cetnar J, and Prasad V. 2016. Effect of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s conflict of interest policy on information overload. JAMA Oncology 2(12): 1653–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch X, Pericas JM, Hernandez C, and Doti P. 2013. Financial, nonfinancial and editors’ conflicts of interest in high-impact biomedical journals. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 43(7): 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignardello-Petersen R, Carrasco-Labra A, Yanine N, et al. 2013. Positive association between conflicts of interest and reporting of positive results in randomized clinical trials in dentistry. Journal of the American Dental Association 144(10): 1165–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton LL, Chabner BA, and Knollman BC, 2011. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th edition) New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Fast Facts: Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed 10/26/2017).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2013. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs: transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests: final rule. Federal Registrar 78(27): 9457–9528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao AH, and Gangopadhyay N, 2016. Industry financial relationships in plastic surgery: Analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 138(2): 341e–348e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, and Mullan F. 2009. The separate osteopathic medical education pathway: Uniquely addressing national needs. Academic Medicine 84: 695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Krimsky S, Anaya M, and Walker J. 2009. Conflicts of interest and disclosure in the American Psychiatric Association’s Clinical Practice Guidelines. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 78(4): 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove L, and Krimsky S. 2012. A comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 panel members’ financial associations with industry: A pernicious problem persists. PLoS Medicine 9(3): e100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove L, Krimsky S, Wheeler EE, Kaitz J, Greenspan SB, and DiPentima NL. 2014. Tripartite conflicts of interest and high stakes patent extensions in the DSM-5. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 83(2): 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetanovich GL, Chalmers PN, and Bach BR. 2015. Industry financial relationships in orthopaedic surgery: Analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database and comparison with other surgical subspecialties. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery: American 97(15): 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K 2007. The information-seeking behaviour of doctors: a review of the evidence. Health Information and Libraries Journal 24: 78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng CW, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, and Dudley RA. 2016. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(8): 1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draugalis JR, Plaza CM, Taylor DA, and Meyer SM. 2014. The status of women in US academic pharmacy. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 78(10): Article 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazen JM, De Leeuw PW, Laine C C, et al. 2010. Toward more uniform conflict disclosures-The updated ICMJE conflict of interest reporting form. New England Journal of Medicine 363(2): 188–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder BJ Subpoenas seek data on orthopedics makers’ ties to surgeons. The New York Times. March 31, 2005. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/31/business/31doctor.html?fta=y (accessed October 26, 2017).

- Fleischman W, Agrawal S, King M, et al. 2016a. Association between payments from manufacturers of pharmaceuticals to physicians and regional prescribing: cross sectional ecological study. BMJ 354: i4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman W, Ross JS, Melnick ER, et al. 2016b. Financial ties between emergency physicians and industry: Insights from Open Payments data. Annals of Emergency Medicine 68(2): 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberman RH, Samson D, Mirza SK, et al. 2010. Orthopaedic surgeons and the medical device industry: the threat to scientific integrity and the public trust. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery: American Volume 92(3): 765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, and Kupfer DJ. 2014. Failure to report financial disclosure information. JAMA Psychiatry 71(1):95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Masters R, James B, Simmons B, and Lehman E. 2012. Do gifts from the pharmaceutical industry affect trust in physicians? Family Medicine 44(5): 325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G Crackdown on doctors who take kickbacks. New York Times. March 3, 2009. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/04/health/policy/04doctors.html?_r=0 (accessed October 26, 2017).

- Jairam V, and Yu JB. 2016. Examination of industry payments to radiation oncologists in 2014 using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments Database. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology and Physics 94(1): 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvies D, Coombes R, and Stahl-Timmins W. 2014. Open Payments goes live with pharma to doctor fee data: first analysis. British Medical Journal 349: g6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas DJ, Bandari J, Browning DN, Jacobs BL, and Davies BJ. 2017. Payments to pediatricians in the Sunshine Act. Clinical Pediatrics 56(8): 723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, and Loscalzo J. 2015. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (19th edition), New York: NY, McGraw Hill Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Katzung B, Trevor A 2014. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (13th edition), New York: NY, McGraw-Hill Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CE, Schmidt LA, and Glantz SA. 2015. Sugar industry influence on the scientific agenda of the National Institute of Dental Research’s 1971 National Caries Program: A historical analysis of internal documents. PLOS Medicine 12(3): e1001798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CE, Schmidt LA, and Glantz SA. 2016. Sugar industry and coronary heart disease research: A historical analysis of internal industry documents. JAMA Internal Medicine 176: 1680–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Siri K, Batra P, and Franklin JM. 2013. Distributions of industry payments to Massachusetts physicians. New England Journal of Medicine 368(22): 2049–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimsky S, and Rothenberg LS. 2001. Conflict of interest policies in science and medical journals: Editorial practices and author disclosures. Science & Engineering Ethics 7: 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimsky S, and Sweet E. 2009. An analysis of toxicology and medical journal conflict-of-interest policies. Accountability in Research 16(5): 235–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DC, Jackson ME, and Hattangadi-Gluth JA. 2016a. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: An epidemiological analysis of early data from the Open Payments program. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 91(1): 84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DC, Moy B, Jackson ME, Mackey TK, and Hattangadi-Gluth JA. 2016b. Distribution of patterns of industry-related payments to oncologists in 2014. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 108(12): pii:djw163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AP, Blair JE, Ko MG, et al. 2014. Gender distribution of the U.S. medical school faculty by academic track type. Academic Medicine 89(2): 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson TB, Meltzer M, Campbell EG, Caplan AL, and Kirkpatrick JN. 2011. Conflicts of interest in cardiovascular practice guidelines. Archives of Internal Medicine 171: 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Selph SS, and Fu R. 2012a. Conflict of interest disclosures for clinical practice guidelines in the National Guideline Clearinghouse. PLoS One 7(11): e47343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, et al. 2012b. Characteristics of physicians receiving large payments from pharmaceutical companies and the accuracy of their disclosures in publications: an observational study. BMC Medical Ethics 13: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein C, Lena Groeger L, Tigas M, and Grochowski JR. 2016. ProPublica, Dollars for Docs. Available at: https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/ (accessed October 26, 2017).

- Papanikolaou GN, Baltogianni MS, Contopoulos-Ionnidis DG, et al. 2001. Reporting conflicts of interest in guidelines of preventive and therapeutic interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepitone K, and Sharkey BP. 2016. The sun never sets on transparency. Medical Writing 25: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Piper BJ, Telku HM, and Lambert DA. 2015. A quantitative analysis of undisclosed conflicts of interest in pharmacology textbooks. PLoS One 10(7): e0133261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathi VK, Samuel AM, and Mehra S. 2015. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the Physician Payment Sunshine Act. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 152: 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AK, Bounds GW, Bakri SJ, et al. 2016. Representation of women with industry ties in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmology 134(6): 636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA, et al. 2011. Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. Journal of the American Medical Association 305(10): 1008–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon SC, and Teitelbaum HS. 2009. The status and future of osteopathic medicine education in the United States. Academic Medicine 84(6): 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawwa K, Kallas R, Koujanian S, et al. 2016. Requirements of clinical journals author’s disclosure of financial and non-financial conflicts of interest: A cross sectional study. PLoS One 11: e0152301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar DP 2016. Women in medicine: Enormous progress, stubborn challenges. Academic Medicine 91(8): 1033–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl SE 2012. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology (4th edition), Cambridge: UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SC, Huecker JB, Gordon MO, Vollman DE, and Apte RS. 2016. Physician-industry interactions and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor use among US ophthalmologists. JAMA Ophthalmology 134(8): 897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DF 1999. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. New England Journal of Medicine 329(8): 573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JC, Volpe KA, Bridgewater LK, et al. 2016. Sunshine Act: shedding light on inaccurate disclosures at a gynecologic annual meeting. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 215(5): 661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton H, and Wardman MJ. 2015. The landscape for women leaders in dental education, research, and practice. Journal of Dental Education 79(5 Suppl): S7–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagiela JA. 2010. Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry (6th edition) Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JS, Franklin JM, Avorn J, Landon J, and Kesselheim AS. 2016. Association of industry payments to physicians with the prescribing of brand-name statins in Massachusetts. JAMA Internal Medicine 176: 763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]