Abstract

Grassroot Soccer developed SKILLZ Street, a soccer-based life skills program and supplementary SMS platform to support adolescent girls at risk for HIV, gender violence, and sexual and reproductive health challenges. We conducted a mixed-methods assessment of preliminary outcomes and implementation processes in three primary schools in Soweto, South Africa, from August-December 2013. Quantitative methods included participant attendance and SMS platform usage tracking, pre/post questionnaires, and structured observation. Qualitative data were collected from program participants, parents, teachers, and a social worker during 6 focus group discussions and 4 in-depth interviews. Of 394 enrolled, 97% (n=382) graduated, and 217 unique users accessed the SMS platform. Questionnaires completed by 213 participants (mean age: 11.9, SD: 3.02 years) alongside qualitative findings showed modest improvements in participants’ perceptions of power in relationships and gender equity, self-esteem and self-efficacy to avoid unwanted sex, communication with others about HIV and sex, and HIV-related knowledge and stigma. The coach-participant relationship, safe space, and integration of soccer were raised as key intervention components. Implementation challenges were faced around delivery of soccer-based activities. Findings highlight the relevance and importance of programs like SKILLZ Street in addressing challenges facing adolescent girls in South African townships. Recommendations for future programs are provided.

Keywords: Adolescent girls, soccer-based intervention, HIV, gender violence, sexual & reproductive health

INTRODUCTION

While notable progress has been made in the past 15 years in reducing the number of new HIV infections, there remains a great need to prevent infections among adolescents, especially in lower- and middle-income countries.(1) According to UNAIDS, adolescent girls and young women ages 15–24 in 2015 accounted for 20% of new HIV infections among adults globally, despite comprising only 11% of the adult population.(2) Adolescent girls are at higher risk than boys in acquiring HIV, as a result of biological, social, and economic factors. As a key driver of the HIV epidemic, sexual and physical violence has been shown in numerous studies to be linked to HIV acquisition among women and girls.(3–5)

In addition to HIV and violence, adolescent girls particularly in sub-Saharan Africa are affected by numerous sexual and reproductive health challenges, including complications during pregnancy and other sexually transmitted infections.(6) They are often unaware of how and where to receive health services, or are reluctant to access services given fears of privacy, confidentiality, and stigma.(7) These challenges are magnified for victims of sexual assault or rape.(8)

Behavior change interventions have been designed with the combined goal of addressing HIV and violence. For example, two life skills interventions providing HIV education while challenging unequal gender norms—Stepping Stones and Program H/M—have shown positive effects on improving gender attitudes and reducing violence in intimate relationships.(9–11) Existing interventions centered at an individual level have typically targeted older adolescents and young adults rather than younger adolescents and children.(12) However, reviews have found that programs are most effective in reducing rates of sexually transmitted infections when conducted prior to sexual debut.(13) Moreover, there is a growing consensus that equitable gender norms must be promoted at an early age before they become deeply engrained.(14) Single-sex programming has been put forth as a strategy for delivering gender-specific content and enabling open conversation about sensitive topics around HIV and gender norms.(15) For girls, this approach can facilitate the creation of a ‘safe space’ where they can not only be physically safe from harm but also have the freedom to express their opinions and build a network of supporters.(16, 17) While recognizing a range of factors at multiple levels that influence the prevalence of HIV and gender-based violence,(18, 19) the literature thus highlights potential value in targeting vulnerable girls directly to improve their health and safety.

There is a particular need to develop evidence-based programs for adolescent girls in South Africa, which endures one of the most severe co-epidemics of HIV and gender-based violence.(20, 21) This co-epidemic is largely fueled by widespread patriarchal gender and cultural norms. In South Africa, young women ages 15–26 who have experienced intimate partner violence are 50% more likely to become infected with HIV than women who have not experienced such violence.(5)

In 2010, Grassroot Soccer (GRS) developed an intervention, called SKILLZ Street, to address HIV, gender violence, and sexual and reproductive health challenges facing at-risk adolescent girls in South Africa. As an international non-governmental organization founded in 2002, GRS trains community role models to implement soccer-based HIV prevention interventions in schools across sub-Saharan Africa and through partnerships worldwide. Previous evaluations have reported on GRS’s mixed-sex(22, 23) and male-specific(24–26) programming. The current paper builds on an earlier evaluation of its female-specific ‘SKILLZ Street’ program(27) to explore preliminary outcomes and processes surrounding implementation of the updated curriculum in a South African township from August through December, 2013.

METHODS

Setting and recruitment

The program was delivered to female students in Grades 6 and 7, ranging from 11 to 16 years old, from three primary schools in Soweto, South Africa. Located 15 kilometers southwest of Johannesburg in the Gauteng Province, Soweto is home to 1.69 million people, mostly of black African descent.(28)

Prior to delivering the intervention and carrying out the program assessment, GRS staff obtained district-level Ministry of Education approval and approval from the principal at each participating school. Schools were purposively selected, in consultation with the district-level Ministry of Education, based on willingness to participate, possession of approximately 100 Grades 6 and 7 female students, and availability for scheduling the intervention after school. Schools were comparable in size and drew from a similar demographic.

All female students in Grades 6 and 7 were invited to participate in the program via announcements in their classrooms over multiple days and provided written agreement to participate. Parents were informed of the program and assessment through an in-person presentation given by a GRS staff member at a parent meeting held at each school. Participants were required to obtain written parental agreement to participate prior to participation. A child protection plan was used to ensure that participants in need of support were referred to appropriate social and health services.

The SKILLZ Street intervention

Facilitated by trained female community leaders called “coaches,” SKILLZ Street is an activities-based program that uses noncompetitive soccer to empower girls, create a safe space for discussion and learning, and encourage girls to advocate for their rights. A 2011 evaluation across five South African sites found the SKILLZ Street program to offer a promising approach for improving adolescent girls’ HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication, as well as increasing uptake of HIV counselling and testing.(27) Building on these findings, GRS undertook curriculum revisions to integrate more content related to gender violence as well as a two-way short-messaging-service (SMS) campaign, in an effort to ensure that the program linked participants with health services in the communities surrounding the targeted schools.

Designed for 100 female participants, the program consisted of ten 2-hour sessions taking place on school grounds after school hours twice-a-week for five weeks. The key structure of the program, viewed positively by participants and coaches,(27) remained constant. Participants were split into teams on the first day, with a participant-coach ratio of on average 10:1. Each session would begin with an “opening circle” to energize all participants and present the plan for the day. Participants would then meet in their teams for a brief period of unstructured “team time.” For half of the session, participants would remain in their teams to engage in structured discussions and soccer-based life skills activities on such topics as body image, sexual reproductive health knowledge, HIV knowledge, and decision-making in relationships. During the other half of the session, participants would take part in soccer games and activities. Sessions would end with informal “team time” with coaches, followed by a “closing circle” with all participants to review the key topics discussed. Participants were provided with “albums” in which to complete activities during sessions and as homework. A graduation was hosted after the completion of the ten sessions.

In partnership with the Thuthuzela Care Centre (TCC) and with support from the International Council for Research on Women (ICRW), GRS integrated a greater focus on sexual reproductive health and violence, responding to requests from participants and coaches in the 2011 evaluation.(27) A new session was developed, during which a guest speaker from the TCC explained TCC service offerings for adolescents and ways to access these services. This session replaced one devoted to hosting an HIV counseling and testing tournament, given that implementation challenges around engaging parents, maintaining confidentiality, and equipping coaches with the skills to support youth during the event—as noted in a previous evaluation (27)—had become more severe over time.

To supplement the formal curriculum, GRS in partnership with the Praekelt Foundation and Western Cape Labs built a two-way SMS campaign on an Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) line.(29) A USSD line is a menu of options that facilitates a conversation about a service between a person and a phone. The aim of the USSD service, called “Coach Tumi,” was to reinforce key messages delivered in the curriculum and provide information on accessing local health services. Using their own phones or a family member’s phone, participants could voluntarily dial a short-code to access information about local health services and quizzes on the following topics: a) SKILLZ Street, b) Girl topics, c) Relationships, d) Gender, and e) Rights and Responsibilities. Once a participant would complete a quiz, the results would appear on the screen, indicating the quiz score and providing encouragement for completing other quizzes. The participant would then receive a follow-up SMS, customized based on her score (see sample Rights and Responsibilities Quiz, Figure 1). Smart phones were not required. While participants would access the platform outside of the program, coaches gave participants a tutorial on how to use the platform during the introductory session and discussed the platform content with participants during each subsequent session. The conceptualization, building, and delivery of a prototype of the Coach Tumi service prior to its integration into the intervention is described elsewhere.(29)

Figure 1:

Sample SKILLZ Street SMS Campaign Layout: Rights and Responsibilities Quiz SKILLZ Street coaches—females aged approximately 18–26 years—underwent at least 80 hours of training prior to delivering the program and were required to have previous experience delivering Grassroot Soccer’s core curriculum for youth ages 10–14. Of the 31 coaches trained, 20 additionally participated in 12 hours of training on the Coach Tumi service.

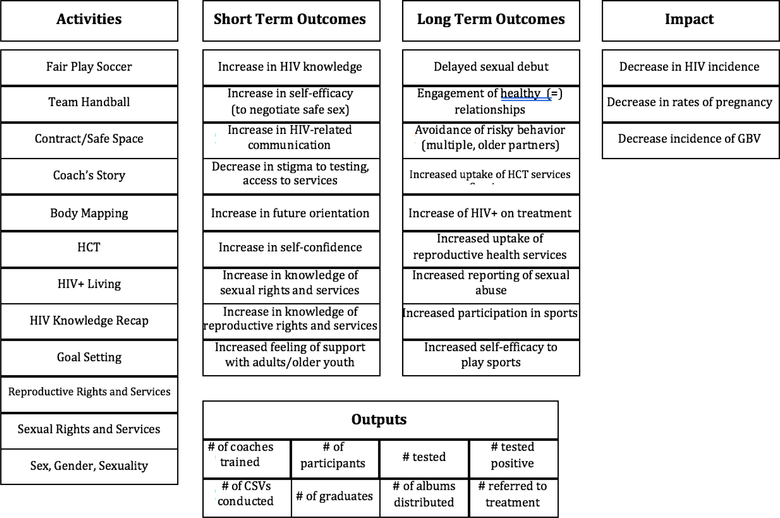

Intervention logic model

The SKILLZ Street logic model describes the planned activities to be delivered during the program; the expected outputs, as well as short and long term outcomes of the program; and the desired long-term impact of the program on the community (Figure 2). The logic model guided the design of the current assessment.

Figure 2:

SKILLZ Street logic model

Assessment design, aims, and objectives

A convergent parallel mixed-methods design was employed for this program assessment.(30) Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously, analyzed independently, and interpreted jointly to provide a fuller understanding of the program being studied. This design was deemed most advantageous for GRS in providing an efficient and cost-effective means of collecting both quantitative and qualitative forms of data, while lending itself to a team approach.(30)

The aim of the assessment was to explore preliminary outcomes of the SKILLZ Street program and the processes through which such outcomes were or were not achieved—the latter based on the U.K. Medical Research Council’s guidelines for conducting a process evaluation.(31)

Objectives included:

Investigate changes in short-term outcomes defined in GRS’s SKILLZ Street logic model immediately before and after intervention delivery;

Understand the intervention’s implementation, including the quantity and quality of the intervention;

Examine mechanisms of impact, including participants’ responses to and unintended consequences of the intervention;

Explore contextual factors that facilitate or impede intervention delivery.

Data collection processes and measures

(a). Attendance registers and mobile phone platform tracking

Attendance of each participant was collected by coaches at the beginning each SKILLZ Street session. Registers were checked for accuracy by program coordinators and entered in the GRS’s data management system to ensure data quality control. To gauge the added benefits of Coach Tumi, GRS tracked the USSD platform usage—including number of users and content accessed—on Praekelt Foundation’s Vumi, an open-source platform enabling organizations to build, send, monitor, and evaluate SMS campaigns.

(b). Pre/post questionnaire

All SKILLZ Street participants were invited to complete a pre- and post-questionnaire immediately before and after the 5-week program in classrooms using Open Data Kit (ODK) software on Android mobile phones. Two trained program evaluators explained the aim of the questionnaires, and phones were distributed to students. Students took on average 45 minutes to complete the questionnaires on the phones. Data were transmitted daily to an online database through a secure wireless connection.

This study reports on questions relating to program participation. Four binary variables measured perceived knowledge of where to obtain services for sexual violence and sexual reproductive health in the community. A composite measure was created to measure self-efficacy to protect oneself from unwanted sex using four items from the Violence against Women Indicators (32). Drawing on items from a previous study among adolescents in South African townships,(33) composite measures were developed to measure: HIV knowledge, HIV stigma, and communication about sexual behavior and HIV. Participants’ self-esteem was measured using an 8-item composite measure, adapted from the Rosenburg Self-Esteem scale (34). An 8-item composite measure measured acceptance of male-dominated gender norms, drawing from the Gender Equitable Men scale (35). An 8-item composite measure assessed participants’ attitudes towards the balance of power in relationships, adapted from the Relationship Power Scale (RPS) (36). All modifications to existing scales were implemented based on pre-testing of items among participants at various GRS sites in South Africa over six months prior to the assessment. See Appendix A for composite measures generated.

(c). Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted to gather group-level views and uncover differences in perceptions within the study population. FGDs addressed motivations/barriers for joining the program, health services available in the community, as well as perceptions of the program structure, implementation, effectiveness, and potential for improvement. In-depth interviews (IDIs) sought to capture individual opinions, perceptions, and experiences.(37) In addition to addressing the themes raising during FGDs, IDIs sought to elicit views on challenges facing local schools and approaches toward addressing issues surrounding sexual reproductive health and rights, as well as violence, in local communities.

A purposive sample was used to select individuals for FGDs and IDIs with the aim of gathering typical perspectives from each group of stakeholders. This approach, often used in qualitative studies, was thus not intended to ensure a representative sample or to obtain generalizable results. Six 90-minute FGDs were conducted, involving: SKILLZ Street participants at each of the three schools (n=3 groups), parents of participants at two of the three schools (n=2 groups), and SKILLZ Street coaches (n=1 group). Each FGD included 6 to 10 participants. Four IDIs were hosted, lasting between 45 and 60 minutes each. Two teachers were selected for interviews from two participating schools. One interview was conducted with a social worker from the Thuthuzela Care Centre, who was engaged with the program throughout its delivery and hosted the “guest speaker” presentation. The final interview was conducted with a parent at the third school, hosted given logistic challenges of engaging a group of parents to participate in a FGD.

Discussions and interviews were conducted by a local GRS staff member with fluency in isiZulu and English and extensive experience with collecting qualitative data in Soweto, particularly with adolescents. Semi-structured guides were used to ask open-ended questions, while an assistant took notes. The discussions were held in quiet, private spaces at the school or GRS office. The language used was either isiZulu or English, depending on the preference of those participating. Discussions were recorded, and later translated (where appropriate) and transcribed by a native speaker in partnership with a local evaluator.

(d). Structured observation

Structured observation was intended to serve as a check against study participants’ subjective reporting during FGDs and IDIs, while also confirming fidelity of program delivery.(37) Three GRS program coordinators were trained to conduct structured participant observation at sessions. The coordinators filled out a checklist of activities taking place and took notes on their reactions to the session, including unexpected occurrences.

Data analysis and integration

Analysis

Attendance data was summarized using simple tabulations. Questionnaire analyses were restricted to participants completing both a pre- and post-questionnaire, without discrepancies in responses. Descriptive analyses of pre/post questionnaires were carried out for all variables. Reliability of composite measures was determined using the Cronbach alpha statistic, the most common measure of reliability for quantitative scales.(38) For all composite measures, scores were assigned to each Likert response option (i.e. 1= “Strongly disagree” to 4= “Strongly agree”). Mean scores and standard deviations were calculated at pre and post. Cohen’s d test was used to estimate the effect size of changes between pre- and post- for continuous variables, with the magnitude of effect interpreted as: <0.20 = small; <0.50= moderate; and <0.80=high.(39) For binary variables, the number of participants answering favorably and the pre to post change in percentage points were generated. Analyses were conducted in STATA 14.(40)

FGDs and IDIs were analyzed thematically by a four-person team using NVivo10 software.(41) First, the team identified patterns emerging from transcripts as they became available, leading the team to develop a structured coding scheme involving primary coding categories and themes corresponding with each category. Team members formally coded each full transcript, extracting quotes illustrative of each theme. Team members convened at regular intervals to discuss discrepancies within the coding, add new themes as deemed appropriate, and refine existing themes. Primary coding categories were identified for outcomes (including six themes; e.g. “self-efficacy and self confidence”) and processes (including four themes; e.g. “key program components”).

Checklists of structured observation forms were summarized using simple tabulations. Comments recorded were coded into themes.

Integration

We developed strategies to merge the quantitative and qualitative data in assessing program’s effect on participants and the processes through which effects were achieved. In line with the contiguous approach,(42) we analyzed findings separately and integrated the data at the interpretation stage. Specifically, we created a summary table of findings to enable the drawing of new insights by assembling the data in a visual means.(42) In interpreting the merged results, we considered convergence, divergence, contradictions, and relationships between methods.(30)

RESULTS

Program attendance and SMS platform usage

In total, 394 female participants were enrolled in SKILLZ Street and 97% (n=382) were eligible to graduate after having attended at least seven of ten sessions. Perfect attendance was recorded for two-thirds (67%) of graduates.

The SMS platform was accessed by 271 unique users and the SKILLZ Street quizzes were taken 159 times over the course of the intervention. The most popular content accessed pertained to pregnancy prevention. Users requested more information about where to access reproductive health services 160 times over the duration of the program.

Pre- and post-questionnaires

Of participants enrolled, 213 were included in pre- and post-questionnaire analyses, resulting in a response rate of 54%. Based on pre-questionnaires, participants ranged in age from 11 to 16 (mean age: 11.9 years, SD: 3.02 years). A majority of participants reported being black (n=171, 82%) and speaking isiZulu at home (n=97, 47%). Over 18% (n=40) reported owning a cell phone. One third reported being in a relationship (n=68, 33%) and 7% (n=16) reported having ever had sex. Over 13% (n=28) reported having ever experienced physical abuse, 8% (n=17) reported emotional abuse, and 16% (n=35) reported sexual abuse.

Participants showed small to moderate improvements on short-term outcomes assessed via composite measures and interpreted using Cohen’s d estimates. With regard to gender equitable norms and intimate relationships, among participants who reported being in a relationship currently (n=42), moderate change was observed for attitudes towards achieving a balance of power in relationships (Cohen’s d: 0.48). Within the full sample, moderate improvement was noted in participants’ gender-equitable attitudes (Cohen’s d: 0.43).

Moderate change from pre- to post- was observed regarding participants’ self-efficacy to protect themselves from unwanted sex (Cohen’s d: 0.46), communication with peers and adults (Cohen’s d: 0.39), HIV stigma (Cohen’s d: 0.33), and self-esteem (Cohen’s d: 0.25). Small change was observed for HIV knowledge (Cohen’s d: 0.19).

At the conclusion of the program, 14 percent more participants reported knowing where to obtain rape services as compared to pre-program. However, participants showed decreases in their self-reported knowledge of where to get services for pregnancy prevention (−3%), HIV testing (−11%), and abortion (−3%) at post- compared to pre.

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews

Preliminary outcomes

a). Self-efficacy and self-confidence

Discussions suggest that participants developed greater self-efficacy to make healthy decisions, stand up for themselves, and question prevailing norms in their communities. For example:

SKILLZ Street gives you the confidence, like strong body language. Not only will I use it to say no to sex, but for other things as well. If you don’t want it, ‘No.’ (SKILLZ Street Participant)

Coaches described that participants became more assertive and more comfortable in taking on leadership roles over the course of the intervention, for instance, by serving as team captain during the soccer matches. They suggested that the program builds participants’ self-esteem, enabling them to discover themselves while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

b). Knowledge, attitudes, and stigma

Participants described learning about ways to protect themselves from HIV and unwanted pregnancy through abstinence and use of condoms. Comments from several indicated increased knowledge of sexual health, including menstruation and family planning. One participant explained the benefits of post-exposure prophylaxis as a means of reducing one’s chances of getting HIV after being raped. Another explained learning that even if she has consented to have sex with someone previously, she can refuse sex with that person when she does not want it.

Coaches believed that participants developed new perspectives on what it means to be in a healthy versus an unhealthy relationship, recognizing flaws in common justifications that a man abuses his partner because he loves her. Several participants discussed gaining a new understanding of the importance of supporting people living with HIV. “I learned that an HIV positive person is not different from anyone else…HIV can be treated. As long as you take medication, you can live a long life,” explained one participant.

c). Communication

The program was cited as increasing participants’ communication with parents, siblings, classmates, and friends about HIV, sexual and reproductive health, and family planning. In one example, a participant described sharing what she learned with her father despite what she perceived as a common belief that fathers cannot be engaged on topics of family planning and sexual health.

Parents felt their daughters were better able to express themselves as a result of the program and often shared with them their learnings from the day. For instance:

My child explained to me how the female condom works…The way she was so comfortable explaining this, you could swear she was not talking to her mother…When she gets in [from school], she puts down her bag and starts telling me all these things she has learned…She now answers when I ask her questions. (SKILLZ Street parent)

For some parents, SKILLZ Street offered a platform for conversation topics that would otherwise be difficult to address. These parents appreciated the opportunity to answer questions asked by their daughters rather than needing to personally raise topics perceived as uncomfortable. Several parents described developing stronger relationships with their daughters as a result of their increased willingness to open up. A teacher felt “overwhelmed and proud” when a participant approached her about not feeling ready for sex, stating “I wish my daughter could be this open with me.”

The SKILLZ Street albums were cited as a useful tool for increasing communication with parents. According to a coach, some participants were having trouble convincing their parents that the program was worthwhile. However, when the participants would show their parents the albums, “it becomes proof to the parent that we are learning…and their parents allow them to come” (Coach).

d). Linkages to sexual health and violence services

Findings suggest that participants gained greater awareness of services available at the Thuthuzela Care Center for sexual and reproductive health and violence, as well as a fuller appreciation for the importance of seeking out health services when needed. As one participant stated:

SKILLZ Street has helped me because now I know that if you’ve been raped, you need to go to the Thuthuzela Care Center…It has its own counselors and police so you don’t have to go to the police station and then the care center. (SKILLZ Street Participant)

Several participants described situations in which they had encouraged a classmate or neighbor outside of the program to disclose an experience with violence to a supportive adult and had referred them to the Thuthuzela Care Center. In one example:

I learned that this girl [my neighbor] was experiencing all sorts of abuse, maybe even sexual abuse. I encouraged her to disclose to her mother, and I also advised her where she can go to for help. Now, she and her mother have left that house. (SKILLZ Street Participant)

Teachers additionally described SKILLZ Street participants as more likely to approach them about their need for reproductive health services, such as sanitary pads, than other students.

e). Broader program effects

Though not a specific desired outcome of the program, a few parents and teachers discussed how the program had led to improved school attendance and performance among SKILLZ Street participants. This theme was raised in a parent FGD and separately by a teacher from another school. For instance:

[Our learners] mostly like being absent from school, but since you guys came along, they been to school at least regularly….Their marks have improved a lot, not only in life skills but in other learning areas. I’ve seen a vast difference in them…There is a lot of improvement. They start enjoying school, and they start to do their schoolwork. (Teacher)

One parent explained that one day after SKILLZ Street, her daughter came home and stated that she was not interested in boys; she just wanted to finish school.

Qualitative findings further suggested some broader program effects beyond the level of the individual SKILLZ Street participant. Notably, one participant explained how a session in the curriculum on gender norms had led to changes in the typical roles among her family members at home:

I liked Sex and Gender [the 2nd session in the curriculum] because previously I could not go play, as I had to do all the cleaning and house chores. But now we share the work between me and my brother. He cleans Monday and I take Tuesday and so forth. (SKILLZ Street participant)

Several interviewees spoke of the program as inspiring them to use new learning methods in engaging youth. Teachers at two schools, as well as the representative from the Thuthuzela Care Center, expressed wanting to give children a greater chance to participate and express their own views as opposed to simply lecturing at them. Coaches described having gained a greater understanding of their own strengths and weaknesses by delivering the program.

Process

a). Key program components

FDG and IDI findings highlighted key components of the intervention believed to affect the outcomes produced. First, the coach-participant relationship was viewed as essential to making participants feel at home and supported. Participants perceived their coaches as positive role models, describing them as “kind,” “respectful,” “honest,” “trusting,” “loving,” “energetic,” “encouraging,” “patient,” “like a sister,” and “like family.” Discussion suggested that coaches treated participants as equals and were patient in their explanations of curricular material. As one participant summarized, “The most important thing is that we were loved and advised by our coaches.”

Closely tied to the coach-participant relationship is the ‘safe space’ afforded by the program. Participants felt open to express themselves, without concern of being judged or stigmatized. Whereas one teacher described a classroom as having “four walls, where everything is formal,” SKILLZ Street was seen as a more playful, open environment that enabled participants to expand their horizons.

The program content was depicted as addressing real issues facing girls, such as important topics of sexual reproductive health and violence that participants often fail to learn about at school or at home. Participants, parents, teachers, and coaches alike praised SKILLZ Street for enabling discussion about topics that are taboo in their communities, while going beyond formal instruction to build the self-esteem and confidence of their girls.

In the coach FGD, some expressed a desire for less formal soccer activities and a greater focus on the soccer-themed discussions. Yet, overall, the inclusion of soccer games and use of an activities-based learning approach were thought to be valuable components of the program. One parent described how her daughter looked forward to attending the program because of the soccer games and activities, which made the program more exciting than a typical HIV-prevention program. The Thuthuzela Care Center social worker perceived the inclusion of soccer games to be central to energizing and engaging the participants:

The concept of using soccer, it was new. I think that was what was so exciting about it…And it looked to be very effective because the kids were perked. I work with kids, and I tell you, after school you cannot find a child just standing there, waiting for someone to talk. But these kids, they were waiting on the sidelines with something to look forward to, and for us, it was like, ‘Wow.’ (Thuthuzela Care Center social worker)

b). The Coach Tumi platform

SKILLZ Street participants spoke positively of the Coach Tumi platform, which they enjoyed using. Their comments suggested that the platform offered confidentiality and reinforced key messages in the curriculum. For example:

I think [Coach Tumi] is interesting because [it talks about] things that we learned in SKILLZ Street and it asks you questions. You are not afraid to answer because you are not afraid of your phone. Nothing must be changed. (SKILLZ Street participant)

Some participants described sharing the platform with people outside the program, including their parents. One parent described being suspicious of her daughter playing on her phone until her daughter demonstrated Coach Tumi: “She would open Coach Tumi and then we’d all read together with my husband.”

Airtime was cited as an important barrier to use by participants and coaches alike, as participants needed airtime on their phones to use the service.

Most of the kids have phones and could access [the Coach Tumi service]. The problem was the airtime. It’s not that they weren’t interested, but they couldn’t afford it. (SKILLZ Street coach)

c). Program implementation

Several facilitators and barriers for program implementation were noted. Regarding facilitators, several girls explained that they joined the program because of their desire to play soccer. Teachers and parents appreciated GRS’s efforts to gain buy-in from relevant stakeholders (i.e. parents and teachers) during program recruitment and through implementation. One teacher praised GRS for being transparent about its goals for the program and empowering teachers to understand its importance prior to its launch. Another teacher praised the coaches for being “reliable,” “professional,” and “eager,” always arriving early and prepared.

Turning to barriers, participants were at times unable to participate given their need to attend to their responsibilities at home (e.g. caring for a sick sibling), long travel distances between school and home, or parents’ concerns of their late arrival home. More broadly, qualitative findings highlighted the urgency of addressing numerous challenges facing SKILLZ Street participants and the communities in which the program is implemented. Schools were said to lack resources, such as social workers or sanitary pads. The prevalence of drugs, lack of police, and tendency for adolescent girls to drop out of school or become pregnant were described as common occurrences. Teachers, parents, and the social worker echoed the depiction of participants as coming from “broken families” (Teacher). These interviewees highlighted a world in which children are often abused and have few outlets for support:

The system fails these kids. The rapists are in their homes. The rapists are their next door neighbors. The rapists are their teachers, pastors, boyfriends, you name them. (Thuthuzela Care Center social worker)

Kids are being raped everyday and parents keep quiet about it. I don’t know why they keep quiet. Some parents defend their husbands and boyfriends…So that’s why you should come back to teach kids they shouldn’t be quiet about such things because this is a very important issue in our community. (SKILLZ Street parent)

d). Suggested changes and improvements

In light of the challenges noted, interviewees recommended expanding the reach of the program to further engage stakeholders in the community at multiple levels, including adolescent boys, parents, teachers, and other age groups of students.

[SKILLZ Street] focuses on the child, and a child lives in a system…As much as it is saying to a child, ‘You have to start being responsible for yourself,’ it tends to be difficult when a child belongs to a system that does not want the child to change. (Thuthuzela Care Center social worker)

A number of interviewees suggested running a parallel program with boys and merging the two programs over time. They also proposed extending the length of the program beyond 10 weeks. Coaches highlighted their strong desire for training as social workers to be better equipped to refer participants for appropriate health services.

Structured observation

Observation was conducted at 10 sessions, as well as 2 graduations. Coaches largely prepared and debriefed as expected during the 10 sessions; they arrived “on time” (i.e. at least 30 minutes prior to the intervention start) at 80% of sessions, reviewed the practice before the intervention at 60% of sessions, and debriefed at 90% of sessions (Table 2). The curriculum itself was delivered less consistently. Of note, participants either played soccer or participated in a soccer drill in only 2 of 10 sessions. Observers listed reasons for not playing soccer as follows: presence of rain (n=2 sessions), to save time for vital conversations and participants’ questions (n=1 session), and because coaches forgot to bring the materials (n=1 session). No explanations for the lack of soccer were provided for the remaining 4 sessions.

Table 2:

Findings from structured observation, carried out at 10 SKILLZ Street program sessions across three primary schools in Soweto, South Africa

| Activity observed | n (%)* |

|---|---|

| Preparation | |

| Coaches arrived on time | 8 (80%) |

| Practice reviewed prior to start of intervention | 6 (60%) |

| Opening Circle | |

| Director shared practice schedule | 9 (90%) |

| Energizer(s) delivered | 9 (90%) |

| Opening Team Time | |

| Coach reviewed last practice | 9 (90%) |

| Coach reviewed previous Micromove | 8 (80%) |

| Coach discussed theme of the day | 10 (100%) |

| Coach reviewed Coach Tumi with participants | 6 (60%) |

| Life Skills Activity | |

| Coach introduced session topic | 10 (100%) |

| Coach provided definitions for new terms | 8 (80%) |

| Coach followed major steps of the activity | 8 (80%) |

| Coach allowed participants to ask questions | 9 (90%) |

| Soccer | |

| Girls played soccer or participated in a soccer drill | 2 (20%) |

| Reasons for not playing soccer (listed by observer) | |

| It was raining | 2 (25%) |

| To save time for vital conversations | 1 (12.5%) |

| Coaches forgot to bring materials | 1 (12.5%) |

| No reason listed | 4 (50%) |

| Closing Team Time | |

| Coach reminded girls about the Question Box | 3 (30%) |

| Coach reviewed practice | 8 (80%) |

| Coach assigned Micromoves | 6 (60%) |

| Coach took attendance | 8 (80%) |

| Coach demonstrated Coach Tumi | 1 (10%) |

| Closing Circle | |

| Song or energizer delivered | 5 (50%) |

| Coach shared info on next practice | 3 (30%) |

| SKILLZ Cheer held | 4 (40%) |

| Debrief | |

| Coach debrief held | 9 (90%) |

| Notes taken | 8 (80%) |

Indicates the number and percentage of sessions during which the activity was performed (out of 10 sessions observed in total).

During regular sessions, observers recorded that participants felt comfortable asking a range of questions on such topics as: menstruation (e.g. use of tampons) and irregularities, female infertility, multiple births, contraceptives, hormones, and abortion. Participants were reported to have memorized the phone number needed to access Coach Tumi. Coaches were praised for their personal connections with participants in observation notes taken. At the observed graduations, coaches were reported to have cooked their own food and brought their own supplies from home (e.g. speakers) to make the event a special occasion. Teachers attended one of the two graduations observed, and the principal was moved to tears by the participants’ singing and drama performances.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine preliminary outcomes, intervention implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors affecting intervention delivery of SKILLZ Street, a soccer-based program addressing HIV and gender based violence among adolescent girls in Soweto, South Africa. Table 3 summarizes our conclusions, integrating our qualitative and quantitative findings.

Table 3:

Summary of conclusions drawn regarding the four study objectives, with associated qualitative and quantitative data

| Conclusions | Qualitative Data | Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Short term outcomes | ||

| In the short term, SKILLZ Street produces a positive effect on participants’ communication with others about sexual reproductive health, ability to avoid unwanted sex and HIV, and perceptions towards gender equitable norms and intimate relationships. While gains were observed in participants’ knowledge of resources offered by the Thuthuzela Care Center, improvements in knowledge of where to get services for other sexual reproductive health services (e.g. pregnancy prevention, HIV testing, and abortion) were not observed. | • Perceived increases in participants’ communication with family, classmates, and teachers about health-related questions and challenges they face (a central theme); • Perceived short-term improvements in participants’ self-efficacy and self confidence, knowledge and attitudes, and awareness of services for sexual and reproductive health and violence; • Some suggestion of broader program effects on family relationships/customs and improved school attendance and performance. |

• Increases observed in participants’ attitudes towards the balance of power in relationships (Cohen’s d: 0.48), gender equitable attitudes (Cohen’s d: 0.43), self-efficacy to avoid unwanted sex (Cohen’s d: 0.46), communication about HIV and sex (Cohen’s d: 0.39), HIV stigma (Cohen’s d: 0.33), self-esteem (Cohen’s d: 0.25), and knowledge of HIV (Cohen’s d: 0.19); • Increases in understanding of where to get services for rape (14% increase in percentage points from pre to post); • Decreases in knowledge of where to get services for pregnancy prevention, HIV testing, and abortion. |

| 2) Intervention implementation | ||

| Findings suggest that the intervention was largely implemented as planned, with high participant attendance rates and satisfaction from participants, coaches, teachers, and parents alike. Soccer was delivered in very few sessions observed. Suggestions were raised to engage further with stakeholders at multiple levels. | • Positive perception of SKILLZ Street among participants, coaches, teachers, and parents; • Positive perception of relationship between Grassroot Soccer and schools; • Request to engage additional audiences, including adolescent boys, parents, teachers, and other age groups of students. |

• 97% graduation rate (7+ sessions attended out of 10); perfect attendance for 67% of graduates; • Roughly 80% of sessions were delivered as planned according to session observation, though soccer was only delivered in 20% of sessions observed; • Coach Tumi platform was accessed by 271 unique users over the course of the five-week intervention. |

| 3) Mechanisms of impact | ||

| The coach-participant relationship, safe-space, curriculum content, and activities-based learning approach incorporating soccer were highlighted as key program components. Promising findings for Coach Tumi USSD platform. | • Coaches viewed as positive role models; • Participants felt free to express themselves; • Curriculum perceived as relevant; participants reported that they enjoyed the soccer-based approach. • Coach Tumi platform viewed promising but requested improvements for accessing the service. |

N/A |

| 4) Contextual factors that facilitate/impede intervention delivery | ||

| Sexual violence, HIV, and other health threats are of real concern for adolescent girls in Soweto. SKILLZ Street is of relevance and importance to this community. Responsibilities at home as well as travel distances to and from school are among barriers to participation cited. | • Participants come from “broken families”; perceived urgency in addressing challenges facing participants, including violence, drugs, and failure to finish school. • Not all participants able to attend program due to home responsibilities, travel distances, and late arrival home. |

N/A |

These findings add to the existing literature on programs designed for young people in at-risk African settings. HIV prevention programs with an explicit gender focus, such as the SISTA program (21) and Stepping Stones (9) in South Africa, have shown improvements in females’ perceived control in their intimate relationships. Studies have indeed highlighted the central importance of addressing unequal gender norms among young people in South Africa.(43) As in our study, systematic reviews of school-based HIV prevention programs in Africa broadly,(44) in South Africa specifically,(45) and utilizing a sport-based approach (23) cite short-term improvements in HIV knowledge, stigma, communication, and self-efficacy when programs are properly delivered. Our findings further add to this body of literature in providing insight into an HIV prevention intervention for younger adolescents ages 10–14, for which data is lacking.(1) Although there is also little evidence on sport-based programs addressing both HIV prevention and gender equity, our findings on participants’ improved self-esteem and self-efficacy to avoid unwanted sex are in line with qualitative exploratory findings from one program engaging girls in soccer activities in Kenya.(46)

In both quantitative and qualitative data, participants demonstrated increased understanding of the services offered by the Thuthuzela Care Center, an important finding given the typical challenges associated with linking young people to the health services they need.(7) The decreases in knowledge about other health services (i.e. pregnancy prevention, HIV testing, and abortion) observed on the surveys are unexpected. It may be that services provided by the Thuthuzela Care Center were emphasized at the expense of other forms of services, leading participants to recognize their lack of awareness of other services by the end of the program. This finding could be supported by qualitative findings and results from the SMS service suggesting that participants were eager for additional information about reproductive health services beyond those offered at the Thuthuzela Care Center. Messaging around linkages to services should be revisited in future iterations of the SKILLZ Street curriculum.

The implementation challenges observed in this assessment are not unlike those experienced by other South African programs. According to a 2010 systematic review, eighty percent of school-based HIV prevention interventions in South Africa experienced serious implementation challenges, such as scheduling disruptions, student and teacher absenteeism, and other school-level issues.(45) Despite these challenges, graduation rates were very high at 97 percent—higher than the rates observed in Soweto during a previous SKILLZ Street evaluation (75.7% in 2011 and 81.8% in 2012).(27) The program was consistently viewed positively among participants, coaches, teachers, and parents. Moreover, schools remain an important avenue for reaching large numbers of young people,(47, 48) suggesting value in attempting to overcome school-related logistical issues affecting program delivery.

Regarding mechanisms of impact, the coach-participant relationship was a key theme raised, consistent with previous studies of GRS programs.(22, 23, 27) The benefits of using older youth as peer educators for HIV interventions have been well documented.(45, 49) This finding reinforces the importance that GRS implementers focus their curriculum, recruitment, and training around building these positive relationships. Another theme raised centered on the importance of generating a space in which participants felt comfortable to discuss sensitive issues and be themselves. This concept of ‘safe space’ has been noted as important particularly to adolescent girls, who are often more restricted in their ability to meet with peers and receive mentoring support than boys.(46)

Observational findings that soccer games were implemented in less than a quarter of interventions may relate to coaches’ preference for less soccer. The 2011 evaluation of SKILLZ Street found that some coaches did not enjoy leading soccer activities because they felt unfamiliar with the sport.(27) It may be that coaches would feel more confident implementing soccer activities if Grassroot Soccer were to give technical training in the game of soccer. On the whole, stakeholders expressed satisfaction with the activities-based curriculum integrating soccer. Although our study did not include a comparator, other studies have shown some evidence of added value when using a sport-based HIV prevention approach compared to a traditional classroom-based approach.(50, 51)

The Coach Tumi USSD platform was perceived favorably as a means of reinforcing curricular messages and increasing awareness of local services. Researchers and practitioners have highlighted the importance of capitalizing on modern communication technologies, such as SMS, as a tool for promoting the linkage between HIV prevention and sexual reproductive health services.(52) Moreover, cell phone usage is high in South Africa, suggesting a promising avenue for reaching young people. In a 2013–4 study, over 77 percent of South Africans ages 9 to 18 reported having used a cell phone in the previous week.(53) Given participants’ challenges in accessing the service, future iterations of Coach Tumi or a similar platform should be designed as free for the user.

Finally, our findings demonstrate notable challenges facing adolescent girls in Soweto, described as coming from “broken families.” The multitude of threats facing girls in such communities, including sexual violence, HIV, and other health concerns, have been documented.(54) These challenges highlight the relevance and importance of programs like SKILLZ Street to such communities, as well as the need for programs to be tailored to the local contexts in which they are implemented. In light of these challenges, we note positive unintended effects of the program on school attendance, which has been shown to be a protective factor against HIV infection among adolescent girls in South Africa.(55)

Future implementers should enhance curricular messaging around linkages to a variety of health services. Building on study participants’ recommendations, implementers should consider further engaging stakeholders besides female participants (e.g. parents, teachers) in the program. Studies indeed highlight the value of adopting a school-wide or community-wide approach when seeking to change norms and behaviors.(44, 45) It may be useful to pair SKILLZ Street with delivery of comparable programming for adolescent boys to engage males in discussions around gender norms and sexual reproductive health. Such an approach could support the changing of social norms that reinforce males’ perpetration of violence against females. It would align with increasing recognition of the need to engage men and boys in addressing HIV and violence(56) and the value of synchronizing gender-specific programming.(57) Future evaluators should investigate the effects of the program over an extended timeframe, with a comparator. This design would not only enable the attribution of changes observed to the program itself, but also help to identify the added value of specific intervention components (e.g. soccer, Coach Tumi) beyond stand-alone life-skills activities. Evaluators should consider measures of outcomes other than self-reports, such as biomarkers or referral data, and further explore intervention effects on students’ school-related outcomes (e.g. attendance and performance).

Limitations

This evaluation is limited by its short timeframe of assessment, which prevents consideration of the sustained effects of the program—particularly on participants’ behaviors. The lack of a control group limits our ability to attribute changes observed to the intervention itself. We relied on self-reported measures of sensitive topics, which may have introduced bias thought to be of particular concern among adolescents.(58) Our response rate for pre/post questionnaires was low (54%), resulting from absences on the dates of questionnaire administration, completion of either the pre- or post-questionnaire but not both, and discrepancies in responses which raised questions about the quality of the participant’s data. The low response rate may have resulted in further information bias—though we generally found consistency between our quantitative and qualitative findings. We asked single questions about experiences of “abuse” rather than using the gold standard approach of asking multiple questions about specific acts of violence,(59) which may have influenced our estimates of violence at pre. Our quantitative composite measures may not have fully captured the constructs we sought to describe, given that reliability and validity testing were beyond the scope of the study. We caution against generalizing study findings, given that schools and participants were purposively selected, our sample size was small, and our response rate for pre/post questionnaires was low.

CONCLUSIONS

In this short-term assessment, SKILLZ Street was found to produce generally positive short-term effects on desired outcomes. Quantitative and qualitative findings showed modest improvements over the five-week program in participants’ attitudes towards power in relationships and gender equity, self-esteem and self-efficacy to avoid unwanted sex, communication with others about HIV and sex, and HIV-related knowledge and stigma. Other potential benefits of the program were raised in focus groups and interviews, including reported improvements in family relationships as well as school attendance and performance. Our findings can be used to inform future development of SKILLZ Street and other activities-based programs for adolescent girls.

Supplementary Material

Table 1:

Pre- and post-questionnaire findings from SKILLZ Street participants (n=213)

| Table 2: re- and post- questionnaire findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Pre mean score (SD) | Post mean score (SD) | Effect size^ | |

| Self-efficacy to protect self from unwanted sex [score range=4–16] | 201 | 12.01 (3.35) | 13.47 (2.88) | 0.46 |

| HIV knowledge [score range=0–6] | 201 | 3.68 (1.36) | 3.94 (1.31) | 0.19 |

| HIV stigma [score range=4–16] | 207 | 12.14 (2.50) | 12.97 (2.50) | 0.33 |

| Communication [score range=2–8] | 203 | 5.55 (1.18) | 6.01 (1.24) | 0.39 |

| Rosenburg self-esteem scale [score range=8–32] | 193 | 23.9 (3.78) | 24.8 (3.86) | 0.25 |

| Gender equitable attitudes (GEM Scale) [score range=10–40] | 197 | 26.3 (3.24) | 27.8 (3.53) | 0.43 |

| Attitudes towards balance of power in relationships (Relationship power scale) [score range=10–40]* | 42 | 35.02 (5.56) | 38.40 (8.26) | 0.48 |

| n | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | Change^^ | |

| Knowledge of where to go to get services for… | ||||

| Rape | 202 | 38 (18.8%) | 66 (32.7%) | + 13.9% |

| Pregnancy Prevention | 203 | 77 (37.9%) | 71 (35.0%) | −2.9% |

| HIV testing | 202 | 112 (55.5%) | 90 (44.6%) | −10.9% |

| Abortion | 203 | 26 (12.8%) | 19 (9.4%) | −3.4% |

Abbreviations: SD=standard deviation; RR= rate ratio.

Notes: For all scales, higher scores indicate changes in the desirable direction.

Among participants who report being in a relationship currently at both pre and post (n=42).

Assessed via Cohen’s d test for effect size, with magnitude of effect interpreted as: <0.20=small; <0.50=moderate; <0.80=high (27).

Denotes change in percentage points from pre to post.

HIGHLIGHTS.

A soccer-based program for adolescent girls in a South African township shows promise.

Modest improvement in gender attitudes, self-efficacy, communication, HIV knowledge, stigma.

Key intervention components are the coach-participant relationship, safe space, and soccer.

Programs like SKILLZ Street are needed for at-risk adolescent girls in such settings.

Further engagement of teachers, parents, and male students in girls’ programming is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Technical support for the SMS platform was provided by the Praekelt Foundation and Western Cape Labs. Special thanks to Gauteng Department of Education District 12 primary schools who participated in this assessment: Harry Gwala, Hector Pieterson, and Obed Mosiane.

FUNDING

Funding for this assessment was provided by the Omidyar Global Fund through the Hawaii Community Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Idele P, Gillespie A, Porth T, Suzuki C, Mahy M, Kasedde S, et al. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS Among Adolescents: Current Status, Inequities, and Data Gaps. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S144–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update: 2016. 2016.

- 3.Anderson N, Cockcroft A, Shea B. Gender-based violence and HIV: relevance for HIV prevention in hyperendemic countries of southern Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:S73–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Moreno C, Watts C. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M. Intimate partner violence, relationships power inequality, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2010;376:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra-Mouli V, Armstrong A, Amin A, Ferguson J. A pressing need to respond to the needs and sexual and reproductive health problems of adolescent girls living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MiFT. Literature review: Youth-friendly health services South Africa 2011. [

- 8.Sarnquist C, Omondi B, Sinclair J, Gitau C, Paiva L, Mulinge M, et al. Rape Prevention Through Empowerment of Adolescent Girls. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1226–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of stepping stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behavior amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: Trial design, methods, and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. Population Council. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricardo C, Eads M, Barker G. Engaging boys and young men in prevention of sexual violence: A systematic and global review of evaluated interventions. Pretoria, South Africa: Sexual Violence Research Initiative, Promundo, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommarin C, Kilbane T, Mercy J, Moloney-Kitts M, Ligiero D. Preventing sexual violence and HIV in children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S217–S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunsheit A Impact of HIV and sexual health education on the sexual behaviour of young people: A review update. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Violence against women and HIV/AIDS: Critical intersections. World Health Organization Information Bulletin Series, Number 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce J, Naberland N, Joyce A, Roca E, Sapiano T. First generation of gender and HIV programs: Seeking clarity and synergy. New York, NY: Population Council, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brady M Creating safe spaces and building social assets for young women in the developing world: A new role for sport. Women’s Studies Quarterly. 2005;33(1/3):35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabala R From HIV prevention to HIV protection: addressing the vulnerability of girls and young women in urban areas. Environment & Urbanization. 2006;18(2):407–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman M, Cornish F, Zimmerman R, Johnson B. Health Behavior Change Models for HIV Prevention and AIDS Care: Practical Recommendations for a Multi-Level Approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 3):S250–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heise L What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown H, Gray G, McIntyre J, Harlow S. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of prevalent HIV infection among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Lancet. 2004(363):1415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wingood G, DiClemente R. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark T, Friedrich G, Ndlovu M, Neilands T, McFarland W. An adolescent-targeted HIV prevention project using African professional soccer players as role models and educators in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10(Suppl. 1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman Z, Spencer T, Ross D. Effectiveness of sport-based HIV prevention interventions: a systematic review of the evidence. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;17(3):987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeCelles J, Hershow R, Kaufman Z, Gannett K, Kombandeya T, Chaibva C, et al. Process evaluation of a sport-based voluntary medical male circumcision demand-creation intervention in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(4):S304–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman Z, DeCelles J, Bhauti K, Hershow R, Weiss H, Chaibva C, et al. A Sport-Based Intervention to Increase Uptake of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Among Adolescent Male Students: Results From the MCUTS 2 Cluster-Randomized Trial in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(4):S297–S303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miiro G, DeCelles J, Rutakumwa R, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Muzira P, Ssembajjwe W, et al. Soccer-based promotion of voluntary medical male circumcision: A mixed-methods feasibility study with secondary students in Uganda. PLOS One. 2017;12(10):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hershow R, Gannett K, Merrill J, Braunschweig Kaufman E, Barkley C, DeCelles J, et al. Using soccer to build confidence and increase HCT uptake among adolescent girls: a mixed-methods study of an HIV prevention program in South Africa. Sport in Society. 2015:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GeoNames. South Africa- Largest Cities: Google Maps; 2016. [Available from: http://www.geonames.org/.

- 29.Merrill J, Hershow R, Gannett K, Barkley C. Pretesting an mHealth intervention for at-risk adolescent girls in Soweto, South Africa: studying the additive effects of SMSs on improving sexual reproductive health & rights outcomes. Preceedings of the sixth international conference on information and communications technologies and development: notes; New York, NY: ACM; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creswell J, Plano-Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles, California: SAGE; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidance. United Kingdom: 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloom S Violence against women and girls: a compendium of monitoring and evaluation indicators. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufman Z The GOAL trial: sport-based HIV prevention in South African schools. London, UK: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg M Conceiving the self. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities. 2008;10(3):322–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker S, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):637–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen K, Guest G, Namey E. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. 2005.

- 38.Cronbach L Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Routeledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.STATACorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.NVivo qualitative data analysis software: QSR International Pty Ltd.

- 42.Fetters M, Curry L, Creswell J. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-- principles and practices. Health Services Research. 2013;48(6 pt 2):2134–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrison A, Hoffman S, Mantell J, Smit J, Leu C, Exner T, et al. Gender-focused HIV and pregnancy prevention for school-going adolescents: the Mpondombili pilot intervention in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2016;15(1):29–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1337–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison A, Newell M, Imrie J, Hoddinott G. HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(102):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brady M, Banu Khan A. Letting girls play: the Mathare Youth Sports Association’s football program for girls. New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason-Jones A, Mathews C, Fisher A. Can peer education make a difference? Evaluation of a South African adolescent peer education program to promote sexual and reproductive health. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(8):1605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathews C, Aaro L, Grimsrud A, SFlisher A, Kaaya A, Onya H, et al. Effects of the SATZ teacher-led school HIV prevention programmes on adolescent sexual behavior: cluster randomised controlled trials in three sub-Saharan African sites. International Health (RSTMH). 2012;4(2):111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medley A, Kennedy C, O’Reilly K, Sweat M. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3):181–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maro C Using sport to promote HIV/AIDS education for at-risk youths: an intervention using peer coaches. Norway: 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balfour L, Farrar T, McGilvray M, Wilson D, Tasca G, Spaans J, et al. HIV prevention in action on the football field: the Whizzkids United program in South Africa. AIDS & Behavior. 2013;17:2045–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mbizvo M, Zaidi S. Addressing critical gaps in achieving universal access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH): the case for improving adolescent SRH, preventing unsafe abortion, and enhancing linkages between SRH and HIV interventions. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2010;110:S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porter G, Hampshire K, Abane A, Munthali A, Robson E, Bango A, et al. Intergenerational relations and the power of the cell phone: perspectives on young people’s phone usage in sub-Saharan Africa. Geoforum. 2015;64:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hlabangane N Teenage sexuality, HIV risk, and the politics of being “duted”: perceptions and dynamics in a South African township. Health Care for Women International. 2014;35:859–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pettifor A, Levandowski B, MacPhail C, Padian N, Cohen M, Rees H. Keep them in school: the importance of education as a protective factor against HIV infection among young South African women. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:1266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casey E, Carlson J, Bulls S, Yager A. Gender transformative approaches to engaging men in gender-based violence prevention: A review and conceptual model. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2016;19(2):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greene M, Levack A. Synchronizing gender strategies: A cooperative model for improving reproductive health and transforming gender relations. Population Reference Bureau, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelley C, Soler-Hampejsek E, Mensch B, Hewett P. Social desirability bias in sexual behavior reporting: evidence from an interview mode experiment in rural Malawi. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2013;39(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.