Abstract

Complex life exists only with a continuous and rich supply of energy from oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. The biochemical machinery that enables the majority of energy production in eukaryotes is encoded by both mitochondrial and nuclear genes so the products of these genomes must interact closely to achieve coordinated function of core respiratory processes. It follows that selection for efficient respiration will lead to selection on optimal combinations of mitochondrial and nuclear genotypes, facilitating mitonuclear coadaptation. In this essay, we outline the modes by which mitochondrial and nuclear genomes coevolve within natural populations, and discuss the implications of mitonuclear coadaptation for diverse fields of study in the biological sciences. We identify six themes in the study of mitonuclear interactions, developed through decades of research, which provide a roadmap for both ecological and biomedical studies seeking to elucidate the contribution of intergenomic coevolution to the genetics of natural populations.

I. INTRODUCTION

Life depends on efficient production of useable energy. The substantial energy needs of complex life are met by the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system embedded within the inner membrane of mitochondria, which produces approximately 90% of the ATP available to cells (Lane and Martin 2010). The enzyme complexes of the electron transport system (ETS), which are responsible for OXPHOS, are comprised of numerous polypeptide subunits. While most of these subunits are encoded by nuclear genes and are transported into mitochondria, the key proton-translocating subunits, which include 13 proteins in bilaterian animals, are encoded by the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Consequently, energy production in eukaryotes must rely on a critical set of interactions between genes that span two distinct genomes (Rand et al. 2004, Wolff et al. 2014, Hill 2015a).

Because the products of mitochondrial genes play a key role in enabling core respiratory processes, it was long assumed that functional variants that appeared within the mtDNA sequence would be quickly removed by purifying selection (Avise 2004). Indeed, this assumption has been supported by analyses of ratios of nonsynonymous (amino-acid changing) to synonymous (putatively silent) mutations across key mitochondrial genes (mt genes) of metazoans, which have pointed to purifying selection as the major force in shaping the evolution of these genes (Rand 2001, Stewart et al. 2008a, Nabholz et al. 2013, Popadin et al. 2013, Zhang and Broughton 2013). As such, a generation of evolutionary biologists, from the 1980s onwards, worked under the purview that the mitochondrial sequence variation segregating within or between populations was selectively neutral (Ballard and Whitlock 2004, Dowling et al. 2008, Ballard and Pichaud 2014).

By the mid-1990s, however, several studies had emerged that questioned the strict neutrality of variation in mtDNA sequence (Ballard and Kreitman 1994, Rand et al. 1994, Pichaud et al. 2012a). Over the next 15 years, a series of experimental studies highlighted the ubiquity of non-neutral (i.e. functional) variation within the mitochondrial genome with pervasive effects on metabolic function (Willett 2008, Arnqvist et al. 2010, Pichaud et al. 2012b, Barreto and Burton 2013a, Bock et al. 2014, Wolff et al. 2016) as well as on the expression of life-history traits (James and Ballard 2003, Rand et al. 2006, Clancy 2008, Dowling et al. 2009, 2010; Ma et al. 2016, Roux et al. 2016). Furthermore, these non-neutral mitochondrial effects often appear to be manifested via allelic interactions between genes spanning the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes (Dobler et al. 2014, Wolff et al. 2014).

Research efforts have since aimed to dissect the evolutionary mechanisms that generate functional mitochondrial variation, and much emphasis has been placed on the potential for accumulation of deleterious mutations in mtDNA (Lynch and Blanchard 1998, Neiman and Taylor 2009). The notion of a high mitochondrial mutation load runs counter to the expectation that strong purifying selection on a haploid genome, in which all alleles are constantly exposed to selection, would effectively prevent the accumulation of non-neutral variants. However, studies in mutant mouse models have suggested that purifying selection may only be fully effective at removing nonsynonymous mtDNA mutations from the female germ-line when these mutations confer severely pathogenic effects (Fan 2008; Stewart et al. 2008a, b). Mitochondrial mutations of moderate effect, including those in tRNA and rRNA genes, can escape selection and be transmitted across generations (Alston et al. 2017). When combined with the observation that mitochondrial genes of many eukaryotes mutate at much higher rates than nuclear genes (Brown et al. 1979, Lynch 1997, Smith and Keeling 2015, Havird and Sloan 2016) and that these mutations reside in a genome that experiences very low rates of recombination (i.e. the most efficient mechanism of preventing mutational accumulation), there would appear to be ample opportunity for accumulation of mutations within mitochondrial genomes to contribute to functional mitochondrial variation.

Mutational erosion of the mitochondrial genome could lead to degradation of energy production and metabolic homeostasis, which could threaten the viability of eukaryote life if left unchecked (Lynch and Blanchard 1998). Therefore, mitochondrial mutation accumulation should create selection for nuclear genotypes able to offset the negative metabolic effects caused by the mtDNA mutations (Rand et al. 2004). Indeed, several studies have now identified signatures of complementary changes in interacting nuclear-encoded genes that have evolved in response to sequence changes in the mitochondrial genome (Osada and Akashi 2012, Barreto and Burton 2013b, Sloan et al. 2014, Havird et al. 2015b, 2017; Van Der Sluis et al. 2015), consistent with a model of compensatory mitonuclear coevolution. Under this model, the mitochondrial genome would provide the mutational fuel that then precipitates coadaptation between mitochondrial and nuclear genomes within populations (Ellison and Burton 2008b, Barreto and Burton 2013b, Yee et al. 2013, Havird et al. 2015b).

The importance of compensatory coevolution between the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes is a topic of current debate (Sloan et al. 2017), and the argument that an asexual and uniparental mode of inheritance makes mtDNA prone to deleterious mutation accumulation has been criticized on both empirical and theoretical grounds (Popadin et al. 2013, Zhang and Broughton 2013, Genes et al. 2013, Cooper et al. 2015, Christie and Beekman 2016). There is also growing interest in the role of adaptive changes in mitochondrial genomes as an alternative source of the functional variation, and recent research suggests that a substantial fraction of nonsynonymous substitutions in mitochondrial genes can be driven by positive selection (James et al. 2016). Because of the intimate functional integration between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, adaptive changes in mtDNA are likely to have epistatic effects and shift selection pressures on the nuclear genome. Indeed, many examples that have been interpreted as supporting a model of compensatory mitonuclear coevolution are also consistent with other forms of mitonuclear coevolution that do not depend on the accumulation of deleterious mitochondrial mutations (Sloan et al. 2017). Whether it is a result of compensation by nuclear genes for accumulation of deleterious alleles in the mtDNA or coordinated responses to beneficial (or neutral) mtDNA alleles, mitonuclear coevolution is predicted to give rise to coadapted mitonuclear genotypes (Rand et al. 2004, Burton et al. 2013, Hill 2015b).

In this essay, we propose that mitonuclear coevolution might be key to enabling a full understanding of the population biology of eukaryotes. We suggest that mitonuclear interactions underlie basic ecological concepts and that the implications of such interactions might resonate beyond the evolutionary and ecological sciences into the realm of biomedicine. We identify and discuss six emerging themes in the study of mitonuclear interactions (Box 1). We propose that ongoing conceptual development within many topics in evolutionary ecology is bounded by a critical requirement that we fully understand the contribution of mitonuclear interactions to shaping the evolutionary dynamics and genetic structure of natural populations.

II. IMPLICATIONS OF MITONUCLEAR INTERACTIONS SPANNING BIOMEDICINE AND ECOLOGY

It has been proposed that the necessity of mitonuclear coadaptation to enable core respiratory function is a key element in basic features of eukaryotes including the evolution of sex and two sexes (Hadjivasiliou et al. 2013, Havird et al. 2015a), adaptation to thermal environment and oxygen pressure (Camus et al. 2017, Sunnucks et al. 2017), and speciation (Burton and Barreto 2012, Hill 2016). The role of mitonuclear interactions in mediating the process of speciation is currently a major area of scientific research and debate. It has been proposed that independent coevolution of mt and nuclear genes in isolated populations could lead to uniquely coadapted sets of genes that are not compatible with the coadapted mt and nuclear genes of other populations. If so, then gene flow and hybridization events between diverging populations could produce negative phenotypic outcomes due to Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities underpinned by mitonuclear interactions (Levin 2003, Dowling et al. 2008, Gershoni et al. 2009, Burton and Barreto 2012, Hill 2017a). Indeed, the results of several laboratory experiments, spanning mammal to invertebrate studies, have supported this hypothesis by showing that the magnitude of incompatibilities between mt and nuclear genes generally increases with the level of overall genetic divergence between the hybridizing populations or species (Kenyon and Moraes 1997, McKenzie et al. 2003, Sackton et al. 2003, Burton et al. 2006a, Camus et al. 2012). In theory, therefore, population divergence driven by mitonuclear interactions represents a plausible model underlying the evolution of reproductive isolation, and ultimately speciation, between incipient populations. At this point, evidence for divergence in coadapted mitonuclear genotypes at species boundaries in natural populations remains limited to a few taxa (Burton et al. 2006a, Baris et al. 2017), and the hypothesis that mitonuclear coadapation plays a direct and general role in driving speciation processes remains controversial and requires further investigation (Gershoni et al. 2009, Chou and Leu 2010, Burton and Barreto 2012, Bar-Yaacov et al. 2015, Hill 2017b, Sloan et al. 2017).

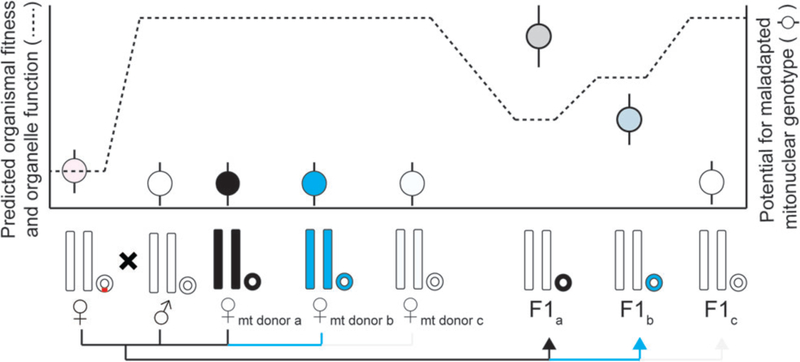

Mitonuclear interactions have also been implicated as a putative contributor to health outcomes associated with the emerging germline therapy of mitochondrial replacement (Reinhardt et al. 2013, Morrow et al. 2015) (Fig 1). Mitochondrial replacement is a modified form of in vitro fertilization that could enable prospective mothers that suffer from mtDNA-induced mitochondrial diseases to produce offspring that are free from the mother’s mtDNA mutations (Gemmell and Wolff 2015). The technique pairs a patient’s nuclear chromosomes, or fertilized pronuclei, with a healthy complement of donor mitochondrial genes inside the donor’s oocyte. Concerns have been raised, however, that the approach may create novel combinations of patient nuclear genotype and donor mtDNA haplotype that have not been previously tested by natural selection and that may lead to unanticipated negative outcomes. However, the potential negative effects of producing novel mitonuclear combinations in human oocytes, while widely debated, remain largely unknown (Reinhardt et al. 2013, Chinnery et al. 2014, Morrow et al. 2015, Sloan et al. 2015, Eyre-Walker 2017, Rishishwar and Jordan 2017).

Fig. 1.

Predicted organismal fitness, organelle function, and potential for maladapted mitonuclear genotypes during mitochondrial replacement theory. Three possible mitochondrial donors are shown, yielding variable degrees of conceivable mitonuclear incompatibilities. Importantly, deleterious mtDNA mutations (shown in red) have known fitness consequences, while those resulting from mitonuclear incompatibilities are predicted and likely complex.

Understanding the roles of mitonuclear interactions in speciation theory, mt replacement therapy, and other complex processes in ecology and biomedicine will benefit from better knowledge of mitonuclear evolutionary dynamics. Below we detail six themes that have emerged from decades of research into the consequences of mitonuclear coevolution and coadaptation that each highlight a specific outcome of the interactions of mitochondrial and nuclear genes that have important implications for both applied and basic population research.

III. EMERGING THEMES IN STUDIES OF MITONUCLEAR COADAPTATION

(1). Theme 1: Relentless selection for mitonuclear compatibility across ontogeny

Selection for optimal mitochondrial function, and hence mitonuclear compatibility, is expected to be intense, and it might well begin as early as oogenesis, with massive selection on cells in the germ line (Krakauer and Mira 1999, Fan 2008, Stewart et al. 2008a, Dowling 2014, Radzvilavicius et al. 2016). In mammals, there is a well-documented bottleneck in the sorting of mtDNA genotypes, which reduces the scope for multiple mitochondrial haplotypes to contribute to the population of any one primary oocyte (Wai et al. 2008, Stewart and Larsson 2014). This mitochondrial genetic bottleneck thus provides the ideal arena upon which oocytes could be screened based on their metabolic integrity, underpinned by their mtDNA genotype (Cree et al. 2008, Wai et al. 2008) and the modulating effect of the nuclear genomic background. We hypothesize that only those oocytes with the greatest capacity for efficient respiratory function, requiring compatible mitonuclear genotypes, should be those predicted to survive the process of atresia (Dumollard et al. 2007, Stewart and Larsson 2014). This process could well represent a core mechanism favoring the transmission of compatible mitonuclear genotypes across generations (Morrow et al. 2015), and preventing the inter-generational mutational meltdown of the mitochondrial genome predicted by theory (Lynch et al. 1993, Lynch and Blanchard 1998, Stewart et al. 2008a, Cooper et al. 2015). Furthermore, the process occurs and can be completed within the developing female foetus during embryogenesis. In humans, this occurs decades before the female mates and produces her own offspring.

In addition, there is large opportunity for selection to act on mitonuclear interactions during the development of cells from spermatogonia to mature sperm cells, but this topic seems not to have been investigated. In humans, a single ejaculate contains approximately 100,000,000 sperm, with only one sperm fertilizing an egg. Again, the difference between a successful and unsuccessful sperm is not random. Swimming speed and endurance, capacity to cope with chemical barriers, and ability to penetrate the egg faster than competitors dictate success (Snook 2005, Pizzari 2009), and sperm derive at least part of the energy that underlies these functions from OXPHOS (Ruiz-Pesini et al. 2007). With few exceptions (Barr et al. 2005), the mitochondria that power sperm are not transmitted to offspring, but the paternal nuclear genome, which includes over 1000 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial (N-mt) genes is transmitted (Calvo and Mootha 2010). N-mt genes create the majority of the mitochondrial proteome, and many interact closely with the mitochondrial-encoded gene products, so strong selection on mitochondrial function leads to strong selection on paternal N-mt genotypes that will be transmitted to offspring.

Selection for mitonuclear compatibility should then continue at every developmental stage following fertilization (Chan 2006). For instance, in mammals not all zygotes successfully implant in the uterine wall; many developing embryos are spontaneously aborted; many individuals die during early development; only a portion of adult individuals succeed in procuring a mate; and, only a portion of reproducing adults produce viable offspring. As a result of selection from gametes to a functional adult is literally the one-in-a-million winner. At each of life-stage, selection for mitonuclear compatibility could be key (Lane 2005). That is, although mitochondrial and nuclear alleles are unlinked and segregate randomly, strong selection through ontogeny could ensure that each adult in the population harbors a fully compatible mitonuclear genotype. The majority of the competition that underlies such selection is, however, difficult to detect (e.g. if it occurs in early ontogeny, before a “pregnancy” is ever even observed) unless one makes extremely careful and detailed observations across life stages.

(2). Theme 2: Mitonuclear coadaptation is manifested in mitochondrial physiology

Coadapted mitochondrial and nuclear genes must interact intimately to enable the core respiratory processes required to power eukaryotic cells (Lane 2011). Therefore, maladapted mitonuclear genotypes are often assumed to produce reduced organismal fitness due to compromised mitochondrial function and disturbed bioenergetics (Gershoni et al. 2009). However, this assumption is seldom tested. Disrupting epistatic interactions between solely nuclear-encoded genes would also result in reduced organismal fitness. Poor mitonuclear interactions should result in reduced fitness specifically due to dysfunction of mitochondrial processes. Moreover, mitochondrial physiology should be affected in a predictable manner according to the specific components that are influenced by incompatibilities (Burton et al. 2013).

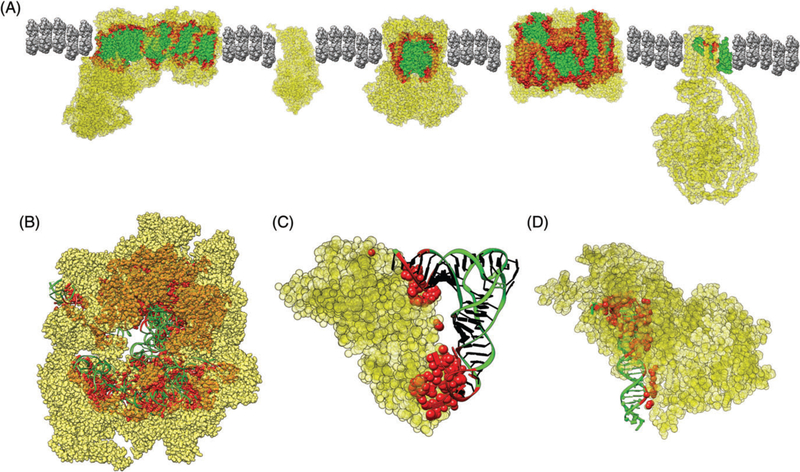

A prime testing ground for assessment of mitonuclear effects distinct from nuclear-nuclear effects is comparison between ETS complexes composed of both mt- and nuclear-encoded subunits, and complexes with only nuclear-encoded subunits. In many eukaryotes, Complex II of the ETS (succinate dehydrogenase) is made up entirely of nuclear-encoded proteins, while the other complexes responsible for ETS function are chimeric assemblies of nuclear and mitochondrial-encoded proteins (Rand et al. 2004)(Fig 1). Complex II function should therefore remain stable regardless of altered mitonuclear interactions, while NADH-dehydrogenase and cytochrome c oxidase activity are predicted to vary with the mitochondrial genomic background. Such predictions have been supported in detailed biochemical assays of ETS complexes in systems with compromised mitonuclear interactions (Ellison and Burton 2006, Meiklejohn et al. 2013). In addition to activities of the ETS complexes, ATP production, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and mitochondrial transcription have all been shown to vary with mitochondrial genotype (Ellison and Burton 2006, 2008a, 2010; Estes et al. 2011, Barreto and Burton 2013a, Hicks et al. 2013, Barreto et al. 2015). Detailed examination of respiration profiles from isolated mitochondria could also reveal the mechanistic basis for lower fitness in compromised individuals (Chung and Schulte 2015, Chung et al. 2017).

(3). Theme 3: Generational delays

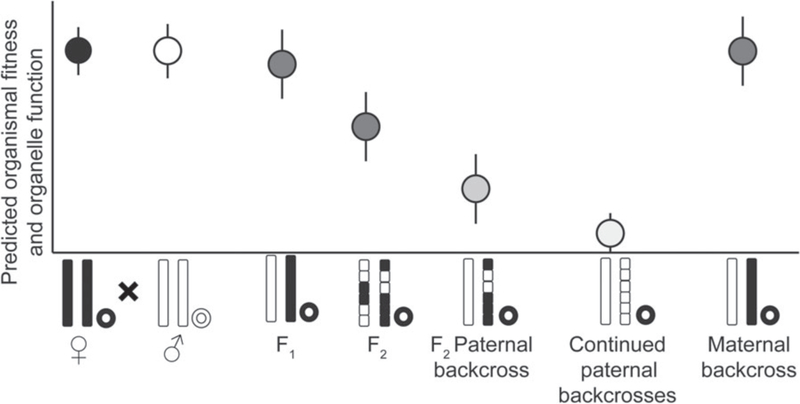

Mitonuclear incompatibilities, when they do occur, may not be revealed until F2 and subsequent generations (Burton et al. 2006a)(Fig. 2). This free pass for the F1 generation arises because offspring receive a full haploid copy of each autosomal chromosome from each parent, and the mitochondrial genome from the mother. Because the mother has demonstrable fitness through her previous survival and current ability to reproduce, the mother’s nuclear genes should be coadapted with the mitochondrial genotype that she also contributed. Even if the father’s nuclear alleles are incompatible with maternal mitochondrial haplotype, effects of mitonuclear incompatibility may not manifest in the F1 generation; the compatible alleles provided by the female may mask the effects of less functional variants provided by the male (Burton et al. 2008b, Stelkens et al. 2015). If F1 hybrids are crossed to create F2 hybrids, however, the segregation of diploid nuclear genes will generate recombinant genotypes, with some individuals receiving two paternal copies at a given nuclear locus. When pure paternal gene combinations are forced to co-function with maternal mt genes, mitonuclear incompatibilities can be revealed (Burton et al. 2006a, Stelkens et al. 2015). The degree to which incompatibilities are masked in the F1 generation will depend on dominance relationships among alleles and whether the nuclear genes involved in mitonuclear interactions are sex linked or lie on the autosomes (Hill and Johnson 2013, Hill 2014).

Fig. 2.

Examples of mitonuclear interactions: A) Multisubunit protein complexes of the electron transport chain, B) mitochondrial rRNA and nuclear ribosomal proteins of the mitochondrial ribosome, C) mitochondrial tRNA-Thr and nuclear threonyl-tRNA synthetase, and D) mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA polymerase gamma. Non-interacting mitochondrial-encoded components are presented in green, nuclear-encoded components are in yellow, and interacting residues that physically contact residues encoded by the other genome are in red. All models are from mammals, except C) which is from yeast. Interacting residues were identified following Sharbrough et al. 2017. PDB accessions used in structural depictions: 5LNK, 1ZOY, 1BGY, 1V54, 5ARA, 3J9M, 4YYE, and 5C51.

(4). Theme 4: Single nucleotide changes cause incompatibilities

Nuclear, and especially mitochondrial, sequence divergence between populations is often presumed to be a more-or-less direct proxy for the likelihood for mitonuclear incompatibilities arising between the populations. However, the majority of changes that distinguish mitochondrial haplotypes are likely to be neutral or nearly so. Moreover, only a subset of nuclear gene products are transported to the mitochondrion, and only a subset of the more than 1000 nuclear gene products that locate in mitochondria will have close functional interaction with mitochondrial gene products (Burton and Barreto 2012, Aledo et al. 2014). Thus, there is clearly a potential for substantial divergence in both nuclear and mitochondrial nucleotide sequences with no loss of mitonuclear compatibility. Conversely, numerous examples now support the contention that mitonuclear incompatibilities leading to loss of fitness could be brought about by just a single SNP in either the mitochondrial or nuclear genotype (Aledo et al. 2014). There are dozens of human diseases that are known to be caused by single SNPs in either nuclear or mitochondrial genes that cause poor mitonuclear interaction (Alston et al. 2017, Sissler et al. 2017), and single point mutations in nuclear and mitochondrial genes have been shown to be the basis for mitochondrial dysfunction in heterospecific hybrid crosses (Meiklejohn et al. 2013). Thus, overall genetic divergence can be a misleading index of mitonuclear compatibility.

(5). Theme 5: OXPHOS function is a product of more than protein interactions

The functionality of OXPHOS depends on using the energy released from electron transfer across the ETS to translocate protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The proton-motive force generated by this process then powers chemical energy production by ATP synthase (Das 2006). This is a process carried out by co-functioning mitochondrial and nuclear proteins (Fig 1A), so the emphasis in studies of mitonuclear compatibility has historically been on protein-protein interactions (e.g. (Kwong et al. 2012, Osada and Akashi 2012, Zhang and Broughton 2013, Havird et al. 2015b). Importantly, however, the mitochondrial-encoded protein subunits of the ETS are transcribed and translated independently of the transcription and translation of nuclear proteins (Taanman 1999), and the biochemical machinery that enables transcription and translation of mitochondrial genes has both nuclear protein components and mitochondrial RNA components (transfer RNA—tRNA—and ribosomal RNA—rRNA)(Fig 1B, C). The mitochondrial-encoded RNA components must co-function with nuclear-encoded proteins (Wallace 2007, Bar-Yaacov et al. 2012, Burton and Barreto 2012, Sloan et al. 2014). Even a single base pair difference between mitochondrial tRNA genotypes can result in reduced fitness when paired with an incompatible nuclear-encoded counterpart (Meiklejohn et al. 2013). The replication and transcription of the mitochondrial genome involves the interaction of mtDNA and nuclear-encoded proteins (Ellison and Burton 2008a, 2010)(2D). Incompatibilities in the mitonuclear components that enable replication, transcription, and translation of mt genes thus affect the capacity for local responsiveness to changing redox conditions, a process that might help account for why genes have been retained within the mitochondria (Allen 2017). Moreover, epistasis may occur even when there is no physical interaction of gene products because biochemical pathways and intracellular signaling are dependent on the coordinated function of mitochondrial and nuclear gene products (Moore and Williams 2005, Woodson and Chory 2008, Clark et al. 2012, Monaghan and Whitmarsh 2015, Baris et al. 2017). Finally, new types of mitonuclear interactions are still being discovered; for instance, there is some evidence that mt genomes encode small RNAs that may act to regulate nuclear gene expression (Pozzi et al. 2017) and several small peptides, such as humanin and MOTS-c, are encoded by the mt genome (Lee et al. 2013, 2015). In sum, mitonuclear incompatibilities can be caused by more than just compromised protein-protein interactions.

(6). Theme 6: Mitonuclear coadaptation is dependent on complex genotype × genotype × environment interactions

There is a tendency to think of mitonuclear gene combinations as either good (generally positive in their phenotypic effects) or bad (inducing negative phenotypic effects). However, the phenotype that results from any given mitochondrial and nuclear genotype combination will also depend on environment. This view is supported by evidence on two fronts. First, experimental studies of invertebrate models in the laboratory have confirmed that the performance associated with particular mitonuclear genotypes is routinely contingent on the environmental context (Ellison and Burton 2006; Dowling et al. 2007, 2010; Arnqvist et al. 2010, Hoekstra et al. 2013, Zhu et al. 2014, Mossman et al. 2016 Willett and Burton 2001,2003). Second, studies of spatial variation in mitochondrial haplotype distributions in humans and other metazoans in their natural environments demonstrate that mutational patterns at key protein-coding genes within the mtDNA sequence closely conform to patterns predicted under a scenario of climatic adaptation (Mishmar et al. 2003, Ruiz-Pesini 2004, Balloux et al. 2009, Cheviron and Brumfield 2009, Quintela et al. 2014, Silva et al. 2014, Morales et al. 2015, Camus et al. 2017). Indeed, a growing view has emerged that environmental context-dependency in mitochondrial disease expression is likely to be common in humans. mtDNA variants that enabled ancestral populations adapt to challenging environments, such as the arctic, might now confer moderate pathogenicity or sub-optimal metabolic performance in modern-day “climate-controlled” conditions (Mishmar et al. 2003, Wallace 2005).

Certainly, some mtDNA mutations, such as those associated with severe defects and that are often the targets of mitochondrial replacement therapy, are confidently classed as dysfunctional and pathological. However, the penetrance of mtDNA mutations associated with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) in humans, a mitochondrial disease that causes blindness, might be moderated by both the mtDNA and nuclear backgrounds on which the disease-causing mtDNA mutation occurs (Cock et al. 1998, Hudson et al. 2005, Tońska et al. 2010). The implication is that complex mitonuclear interactions involving numerous genetic loci spanning both of the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes are affecting the penetrance of pathogenic LHON-conferring mtDNA mutations in human populations. Indeed, although epistasis is sometimes downplayed in discussion of mitochondrial replacement therapy (Tanaka et al. 2013, Chinnery et al. 2014), it is well known that penetrance of numerous disease-conferring mtDNA mutations is affected by a range of modifier alleles that lie within the nuclear genome (Taanman 2001, Bykhovskaya et al. 2004, Ballana et al. 2007, Davidson et al. 2009, Luo et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2015, Morrow and Camus 2017). Thus, signatures of mitonuclear epistasis, moderating disease penetrance and outcomes, are already known to be common in human populations.

Intriguingly, the abiotic environment also appears to play a key role in the level of function or dysfunction conferred by particular mtDNA haplotypes, and these effects again extend even to confirmed pathogenic mtDNA mutations. A recent study by Ji et al. (Ji et al. 2012) revealed that LHON-causing mtDNA mutation (3394C) exhibits intriguing patterns in its distribution across Asia. Although the 3394C mutation has arisen multiple times across the human mitochondrial phylogeny (it is found on numerous mtDNA haplotypic backgrounds), it is highly enriched on haplotypes that are common in high altitude Asian populations (M9 haplotype in Tibet, and the C4a4 haplotype in the Indian Deccan Plateau), to the extent that at above altitudes of 1500m the 3394C variant is 22 times more likely to be found than among sampled low-altitude Han Chinese populations. In fact, there were no cases of the wild-type 3394T variant ever being associated with the M9 haplotype in high altitude Tibetan populations, suggesting this wild type allele might even be incompatible with the M9 background (a putative case of mtDNA × mtDNA negative epistasis). The question therefore arises; could this LHON-conferring 3394C mutation thus be adaptive at high latitudes, or are these patterns simply reflective of neutral demographic processes? While the jury is still out, functional analyses have shown that this mutation causes reductions in mitochondrial complex I activity of between 7 and 28% when expressed on the lowland BC4 and F1 Asian haplotypes, but no such reductions in transmitochondrial cybrid lines carrying the M9 haplotype. This result lends credence to the suggestion that the 3394C mutation could well be adaptive at high altitudes, while pathological at low altitudes.

Furthermore, in addition to the external environment, sex may also play a role in dictating the outcomes of mitonuclear interactions. Because mitochondria are transmitted through the female lineage, mitochondrial mutations that are male-harming can in theory escape the action of natural selection. Such mutations can therefore increase and linger in populations and be fixed through neutral mechanisms or even spread through positive selection if they confer fitness advantages to females (Frank and Hurst 1996, Gemmell et al. 2004, Beekman et al. 2014). This “mother’s curse” may be key to explaining why mitochondrial diseases such as LHON exhibit much higher penetrance in males (Yen et al. 2006, Ventura et al. 2007, Milot et al. 2017). Indeed, experimental evidence has emerged to indicate that some of the genetic variation that delineates naturally-occurring mtDNA haplotypes in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) may exhibit male-biases in effects on key life-history traits tied to reproduction and survival (Innocenti et al. 2011a; Camus et al. 2012, 2015), and other case studies have come to light in flies (Patel et al. 2016), mice (Nakada et al. 2006), hares (Smith et al. 2010) and humans (Martikainen et al. 2017) of mtDNA polymorphisms exerting negative effects exclusively on male components of fertility.

IV. DISCUSSION

(1). Implications for understanding speciation

While we strongly advocate consideration of mitonuclear interactions in future studies that seek to understand species boundaries in natural populations, we acknowledge the practical constraints of working with many metazoan species such as birds, which produce few offspring and will not breed in captivity, make many key experiments and analyses impossible. It is instructive to therefore consider the study of speciation in animals for which such constraints have been overcome, and the splash pool copepod, Tigriopus californicus, may be the best model for studies of population divergence and speciation in which the role of mitonuclear interactions has been most completely studied (Burton et al. 2013).

Two aspects of the biology of T. californicus set the stage for development of mitonuclear coadaptation. First, rates of mtDNA substitution are high; Willett (2012) estimated that the rate of substitutions at synonymous sites in T. californicus mtDNA is 55-fold higher than the rate in nuclear genes. Second, T. californicus populations show strong population structure; restricted gene flow between populations has resulted in not only high levels of mtDNA divergence across populations, but also maximized the opportunity for selection to mold the nuclear genome in response to mtDNA divergence.

Numerous studies of mitonuclear interaction have taken advantage of the Tigriopus system and these have worked within each of the themes developed in this essay. The importance of considering fitness variation across life stages (theme 1) can at least partially be addressed in this system by determining allelic frequencies of candidate genes in a sample of newly hatched larvae to their frequencies in surviving adults from the same cohort. In an analysis of the alleles of the cytochrome c (CYC) gene (a nuclear gene encoding a protein essential to ETS function), Willett and Burton (Willett and Burton 2001) observed expected Mendelian genotypic ratios in F2 hybrid larvae, but in adult animals from the same cross they observed that the ratios were skewed in favor of restoring coevolved mitonuclear genotypes. In addition to suggesting that CYC has coevolved with mitotype, this type of experiment isolates the form of selection as larval-to-adult viability selection. In this particular case, in vitro biochemical experiments and site-directed mutagenesis further verified the functional coevolution of CYC with mitotype, and demonstrated that a single amino acid substitution could dramatically change the functional interaction between a nuclear gene and a ETS complex (Rawson and Burton 2002, Harrison and Burton 2006) (theme 4).

Laboratory hybridizations of Tigriopus clearly show that mitonuclear incompatibilities may not be expressed until F2 or later generations (theme 3). In fact, most interpopulation crosses in this species show some degree of hybrid vigor in first-generation hybrids, with hybrid breakdown clearly expressed in F2 and F3 generations (Burton et al. 2006a). The key role of mitonuclear interactions in hybrid breakdown is apparent in the contrasting results of maternal and paternal backcrosses of F2 or F3 hybrids: maternal backcrosses re-establish coadapted mitonuclear genotypes and recover fitness while paternal backcrosses do not (Ellison and Burton 2008b). In addition to being apparent in whole organism fitness, functional assays of isolated mitochondria from hybrids clearly reveal degraded performance of ETS Complex I, III, IV and V—but not entirely nuclear-encoded Complex II—compared to mitochondria isolated from parental (natural) populations (Ellison and Burton 2006) (theme 2).

Although there are clear examples of protein-protein interactions underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in Tigriopus hybrids, it is also clear that non-protein coding regions of the mtDNA likely participate in mitonuclear incompatibilities (theme 5). Transcription of mtDNA requires a specific nuclear encoded RNA polymerase (mtRPOL) to recognize a promoter site in the non-coding region of the mtDNA. Ellison and Burton (Ellison and Burton 2008a) found that population mismatches between mtDNA and mtRPOL resulted in reduced mtDNA gene expression and often in reduced genotypic viability. At a more global level, Barreto and Burton (Barreto and Burton 2013b) hypothesized that ribosomal proteins interacting with fast evolving mtDNA-encoded rRNA would show evidence for elevated rates of evolution compared to those interacting with slower evolving nuc-DNA rRNA. Although all ribosomal proteins are encoded in the nuclear genome, those targeted to the mitochondria and interacting mtDNA-encoded rRNA indeed showed strong signatures of elevated substitution rates. These data show that the reach of selection pressures for mitonuclear interaction extend beyond the protein-protein domain – nuclear genes interacting with non-coding and rRNA-coding mtDNA elements show a visible signature of mitonuclear coadaptation. These data also suggest that relatively small changes to the nucleotide sequence can have big impacts on fitness through compromised mitonuclear interactions (theme 4)

As discussed earlier, the impact of environmental variation on mitonuclear interactions is often overlooked and can be substantial (theme 6). Willett and Burton (Willett and Burton 2003) found that the relative fitness of CYC genotypes not only depended on mitotype (see above), but also on the thermal environment; constant 16 °C led to consistent selection against a Los Angeles CYC on a Santa Cruz mitotype background while diurnal cycling between 16 °C and 25 °C resulted in no apparent selection in the same cross. Although no specific model has been proposed to explain these results, the complexities of enzyme thermal responses (CYC transfers electrons between Complex III and Complex IV in the ETS) suggest that interactions among non-coevolved proteins in hybrids might be subject to disruption.

(2). Implications for best practices in mitochondrial replacement therapy

Discussion of mitochondrial replacement therapy has focused on 1) the anticipation of problems based on understanding patterns of genetic variation and structure within and among human populations, and 2) an assessment of the outcomes of mitochondrial replacement in animal models and humans. A mitonuclear perspective that draws on insights from studies of natural non-human populations should be very helpful in developing best practices for performing mitochondrial replacements techniques in humans. First, following theme 1, full assessment of the outcome of any combination of mitochondrial and nuclear genes can only come after a complete lifetime because many of the negative consequences of mitonuclear dysfunction might be late onset diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases (Hudson et al. 2014).

Moreover, researchers should be skeptical of attempts to draw inferences regarding the potential for mitonuclear incompatibilities humans from assessments of genome-wide covariation between levels of mtDNA and nuclear divergence in the adult population. For instance, in a recent study, Rishishwar and Jordan (Rishishwar and Jordan 2017) assessed the risk of negative outcomes of mitochondrial replacement therapy in humans based on mitonuclear incompatibilities by observing patterns of mitochondrial haplotype and nuclear introgression in humans. They used the whole mitochondrial and nuclear genome sequences for 2054 “healthy adult” humans available through the 1KGP project (The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium 2015), which included “five major continental population groups”, to assess the possibility that there may be incompatibilities between some mt and N-mt genes between some human populations. The logic of the analysis by Rishishwar and Jordan (2017) was that if individuals who carry nuclear genes from one population and mitochondrial genes from another population can exist as healthy adults, then admixture of nuclear and mitochondrial genes from divergent populations must not present any risk of mitonuclear incompatibilities in mitochondrial replacement therapy. There are numerous problems associated with such inferences. Firstly, they do not adequately consider the possibility of selection operating against mitonuclear genotypes at earlier life stages (theme 1). Assessment of healthy adults provides no insights into whether selection had eliminated mitonuclear incompatibilities at earlier life stages in individuals not sampled. Secondly, such inferences are based on genome-wide patterns of mitonuclear association and divergence, and such broad-brushed approaches to assessing mitonuclear genetics overlook the likely scenario that the relevant associations among nuclear genes will be limited to relatively small number of key loci that interact with the mt genome (theme 4). As we have discussed above, mitonuclear incompatibilities might be underpinned by divergence at a small number of sequence sites that are under strong selection for mitochondrial function. Finally, even the statement that subjects in the data set were healthy presents an untested assumption because no phenotypic data are presented in the Rishishwar and Jordan study. Ideally, one would try to link population genomic patterns of mitonuclear genotypes to detailed measures of phenotype (including information on mitochondrial function; theme 2) (Morales et al. 2015, Baris et al. 2017).

(3). The future will rely on integration of molecular, biochemical and ecological approaches

Looking to the future, we advocate that integrative approaches are needed to better understand the molecular basis and fitness consequences of mitonuclear interactions (Sunnucks et al. 2017). Genotype-to-phenotype links can be developed by combining: (i) sequencing of mitochondrial and nuclear genomes to detect sites of selection in populations; (ii) molecular modelling and mapping to predict the effects of substitutions on protein structure, function, and interactions; and (iii) respirometry and fitness measurements to infer consequences of substitutions at mitochondrial, organismal, and population levels.

Molecular modelling is emerging as a particularly valuable tool to make predictions about the effects of mitonuclear interactions on mitochondrial respiration (Grossman et al. 2004, Scott et al. 2011). Driven by recent advances in structural biology, complete three-dimensional structures are now available of the respiratory complexes of the mammalian electron transport chain (Tsukihara et al. 1996, Iwata 1998, Fiedorczuk et al. 2016) and the respirasome supercomplex (Wu et al. 2016). It is therefore possible to use these structures to analyze direct molecular interactions between nuclear and mitochondrial gene products. Construction of homology models of sequenced variants of OXPHOS subunits facilitates predictions about how substitutions may affect structure, function, and interactions of OXPHOS complexes. Such approaches have inferred climate-driven positive selection in mitochondrial-encoded OXPHOS Complex I components in a range of animal taxa (Finch et al. 2014, Garvin et al. 2014, Caballero et al. 2015). Structural mapping has also recently provided evidence of epistatic interactions between mt-encoded and nuclear-encoded OXPHOS Complex I variants potentially under climate-driven selection (Garvin et al. 2016, Morales et al. 2016). As we have noted, mitonuclear incompatibilities need not involve direct interactions within multi-subunit complexes (Innocenti et al. 2011b, Baris et al. 2017). Nevertheless, the direct molecular interactions between nuclear and mitochondrial gene products remain leading candidates. In accord with theme 5, homology modelling is also an option to probe protein-DNA and protein-RNA mitonuclear interactions (Bar-Yaacov et al. 2015).

It is important, however, to note that molecular understanding of mitonuclear interactions remains in its infancy. The complete atomic resolution of the OXPHOS Complex I and the respirasome were only recently resolved (Fiedorczuk et al. 2016, Gu et al. 2016) and only low-resolution structures of metazoan ATP synthase are available (Zhou et al. 2015). As a result, there is limited information about the structure, function, and interactions of many OXPHOS subunits and their residues. Thus, it is rarely justified to make detailed mechanistic inferences from molecular modelling, and any predictions should be treated with caution until empirically tested (e.g. respirometry measurements). We anticipate that future advances will increase the predictive power of molecular modelling: higher resolution structures of the respirasome and ATP synthase; improved understanding of how OXPHOS complex structure relates to function at a range of levels and in specific environments; and development of molecular dynamics simulations for these complexes that may reveal the sources of environmental interactions. In turn, such approaches may allow screening for compatible mitonuclear interactions in mitochondrial replacement therapy and help consolidate genotype-to-phenotype links in mitonuclear ecology.

V. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Only in the last couple of decades has the significance of mitochondrial variation and the interactions of mitochondrial and nuclear genes been incorporated into a conceptual framework for understanding population structure and speciation. It is still a minority of studies that give any consideration to the potential effects of mitonuclear interactions in assessing adaptation and attempting to understand the genetic basis for variation in individual performance. We propose that it is inevitable that interacting mitochondrial and nuclear genotypes will have effects on how populations are structured, with implications for the process of speciation and medical therapies involving recombining mitochondrial and nuclear genotypes. The key question is how much of an overall effect will arise from mitonuclear interactions versus interactions among nuclear genes, and this question can only be answered with a greater research focus on mitonuclear interactions. Our growing understanding of the coevolution, coadaptation, and cofunction of the products of mitochondrial and nuclear genes in natural populations has established a set of themes that should guide research. The future lies in the integration of a mechanistic understanding of the biochemical and biophysical consequences of mitochondrial and nuclear genotypes with population biology and ecology.

Fig. 3.

Predicted organismal fitness and organelle function across generations. Note that in the F1 generation, mitonuclear incompatibilities will generally be masked by retention of a maternal allele. Most mitonuclear incompatibilities are predicted to occur in F2 or later generations. After Burton et al. 2013.

Table 1.

Six themes in the study of mitonuclear interactions

| 1. | Relentless selection for mitonuclear compatibility across ontogeny. Mitonuclear interactions have fitness consequences at multiple stages of development, which may result in compounding effects in filtering out maladapted mitonuclear genotypes. |

| Prediction: The frequencies of mt and N-mt genes are predicted to change across life stages via selection for mitonuclear compatibility and functionality. | |

| 2. | Mitonuclear coadaptation is manifested in mitochondrial physiology. The localized role of mt gene products within the mitochondria leads to the expectation that deleterious effects of maladapted mitonuclear genotypes will be mediated by changes in mitochondrial function. |

| Prediction: Incompatibilities in coadapted sets of mt and N-mt genes will have effects targeted to the physiological and biochemical properties of mitochondria. | |

| 3. | Generational delays. Mitonuclear incompatibilities may be shielded by dominance in the F1 generation. |

| Prediction: The negative effects of novel combinations of mitochondrial and nuclear genes may not be evident until F2 and later generations. | |

| 4. | Single nucleotide changes cause incompatibilities. Because many or most of the sequence changes that contribute to divergence in nuclear and mt genes may be neutral, the actual variants responsible for mitonuclear incompatibilities likely represent a small subset of total sequence change. |

| Prediction: Mitonuclear incompatibilities can be caused by a small number of variants and may not be proportional to overall sequence divergence. | |

| 5. | OXPHOS function is a product of more than protein interactions. Although most attention has focused on the protein-protein interactions that occur within OXPHOS complexes, there are many other arenas for mitonuclear interactions, including mitochondrial translation, transcription, and DNA replication. |

| Prediction: Mitonuclear coadaptation and compatibility will involve complex interactions of gene products beyond those between proteins. | |

| 6. | Mitonuclear coadaptation is dependent on complex genotype × genotype × environment interactions. Mitochondrial function and physiology is highly context dependent, so the signatures of mitonuclear coadaptation are likely to be as well. |

| Prediction: The outcomes of genetic interactions between mitochondrial and nuclear genomes will be dependent on the genetic (via epistasis involving other mtDNA and nuclear SNPs), physiological (the sex in which the mtDNA is expressed) and abiotic environment. |

Acknowledgements

NIH R01 GM118046 to DBS. Australian Research Council (FT160100022 and DP170100165) and Hermon Slade Foundation (HSF 15/2) to DKD.

References

- Aledo JC, Valverde H, Ruíz-Camacho M, Morilla I, and López FD (2014). Protein-protein interfaces from cytochrome c oxidase i evolve faster than nonbinding surfaces, yet negative selection is the driving force. Genome Biology and Evolution 6:3064–3076. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JF (2017). The CoRR hypothesis for genes in organelles. Journal of Theoretical Biology 0:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alston CL, Rocha MC, Lax NZ, Turnbull DM, and Taylor RW (2017). The genetics and pathology of mitochondrial disease. Journal of Pathology 241:236–250. doi: 10.1002/path.4809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnqvist G, Dowling DK, Eady P, Gay L, Tregenza T, Tuda M, and Hosken DJ (2010). Genetic architecture of metabolic rate: Environment specific epistasis between mitochondrial and nuclear genes in an insect. Evolution 64:3354–3363. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise JC (2004). Molecular Markers, Natural History, and Evolution In Sinauer, Sunderland, MA. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballana E, Mercader JM, Fischel-Ghodsian N, and Estivill X (2007). MRPS18CP2 alleles and DEFA3 absence as putative chromosome 8p23.1 modifiers of hearing loss due to mtDNA mutation A1555G in the 12S rRNA gene. BMC medical genetics 8:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO, and Kreitman M (1994). Unraveling selection in the mitochondrial genome of Drosophila. Genetics 138:757–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO, and Pichaud N (2014). Mitochondrial DNA: More than an evolutionary bystander. Functional Ecology 28:218–231. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO, and Whitlock MC (2004). The incomplete natural history of mitochondria. Molecular Ecology 13:729–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balloux F, Handley L-JL, Jombart T, Liu H, and Manica A (2009). Climate shaped the worldwide distribution of human mitochondrial DNA sequence variation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276:3447–3455. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yaacov D, Blumberg A, and Mishmar D (2012). Mitochondrial-nuclear co-evolution and its effects on OXPHOS activity and regulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1819:1107–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yaacov D, Hadjivasiliou Z, Levin L, Barshad G, Zarivach R, Bouskila A, and Mishmar D (2015). Mitochondrial involvement in vertebrate speciation? {The} case of mito-nuclear genetic divergence in chameleons. Genome Biology and Evolution:evv226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baris TZ, Wagner DN, Dayan DI, Du X, Blier PU, Pichaud N, Oleksiak MF, and Crawford DL (2017). Evolved genetic and phenotypic differences due to mitochondrial-nuclear interactions. PLoS Genetics 13:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CM, Neiman M, and Taylor DR (2005). Inheritance and recombination of mitochondrial genomes in plants, fungi and animals. New Phytologist doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01492.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Barreto FS, and Burton RS (2013a). Elevated oxidative damage is correlated with reduced fitness in interpopulation hybrids of a marine copepod. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280:20131521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto FS, and Burton RS (2013b). Evidence for compensatory evolution of ribosomal proteins in response to rapid divergence of mitochondrial rRNA. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:310–314. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto FS, Pereira RJ, and Burton RS (2015). Hybrid dysfunction and physiological compensation in gene expression. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32:613–622. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman M, Dowling DK, and Aanen DK (2014). The costs of being male: are there sex-specific effects of uniparental mitochondrial inheritance? Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 369:20130440. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock DG, Andrew RL, and Rieseberg LH (2014). On the adaptive value of cytoplasmic genomes in plants. Molecular Ecology doi: 10.1111/mec.12920 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown WM, George M, and Wilson AC (1979). Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial {DNA}. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 76:1967–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RS, and Barreto FS (2012). A disproportionate role for mtDNA in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities? Molecular Ecology 21:4942–4957. doi: 10.1111/mec.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RS, Ellison CK, and Harrison JS (2006a). The sorry state of F-2 hybrids: Consequences of rapid mitochondrial DNA evolution in allopatric populations. American Naturalist 168:S14–S24. doi: 10.1086/509046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RS, Ellison CK, and Harrison JS (2006b). The sorry state of {F}−2 hybrids: {Consequences} of rapid mitochondrial {DNA} evolution in allopatric populations. American Naturalist 168:S14–S24. doi: 10.1086/509046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RS, Pereira RJ, and Barreto FS (2013). Cytonuclear genomic interactions and hybrid breakdown. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 44:281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaya Y, Mengesha E, Wang D, Yang H, Estivill X, Shohat M, and Fischel-Ghodsian N (2004). Human mitochondrial transcription factor B1 as a modifier gene for hearing loss associated with the mitochondrial A1555G mutation. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 82:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero S, Duchêne S, Garavito MF, Slikas B, and Baker CS (2015). Initial evidence for adaptive selection on the NADH subunit two of freshwater dolphins by analyses of mitochondrial genomes. PLoS ONE 10:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo SE, and Mootha VK (2010). The mitochondrial proteome and human disease. Annual review of genomics and human genetics 11:25–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus MF, Clancy DJ, and Dowling DK (2012). Mitochondria, maternal inheritance, and male aging. Current Biology 22:1717–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus MF, Wolf JBW, Morrow EH, and Dowling DK (2015). Single Nucleotides in the mtDNA Sequence Modify Mitochondrial Molecular Function and Are Associated with Sex-Specific Effects on Fertility and Aging. Current Biology 25:2717–2722. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus MF, Wolff JN, Sgrò CM, and Dowling DK (2017). Experimental evidence that thermal selection has shaped the latitudinal distribution of mitochondrial haplotypes in Australian fruit flies 1–33. doi: 10.1101/103606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chan DC (2006). Mitochondria: Dynamic Organelles in Disease, Aging, and Development. Cell 125:1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheviron ZA, and Brumfield RT (2009). Migration-selection balance and local adaptation of mitochondrial haplotypes in Rufous-Collared Sparrows (Zonotrichia Capensis) along an elevational gradient. Evolution 63:1593–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery PF, Craven L, Mitalipov S, Stewart JB, Herbert M, and Turnbull DM (2014). The Challenges of Mitochondrial Replacement. PLoS Genetics 10:3–4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JY, and Leu JY (2010). Speciation through cytonuclear incompatibility: Insights from yeast and implications for higher eukaryotes. BioEssays 32:401–411. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JR, and Beekman M (2016). Uniparental Inheritance Promotes Adaptive Evolution in Cytoplasmic Genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34: 10.1093/molbev/msw266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DJ, Bryant HJ, and Schulte PM (2017). Thermal acclimation and population-specific effects on heart and brain mitochondrial performance in a eurythermal teleost ( Fundulus heteroclitus ). Journal of Experimental Biology 220:1459–1471. doi: 10.1242/jeb.151217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung DJ, and Schulte PM (2015). Mechanisms and costs of mitochondrial thermal acclimation in a eurythermal killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). The Journal of Experimental Biology 218:1621–1631. doi: 10.1242/jeb.120444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy DJ (2008). Variation in mitochondrial genotype has substantial lifespan effects which may be modulated by nuclear background. Aging Cell 7:795–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NL, Alani E, and Aquadro CF (2012). Evolutionary Rate Covariation : A bioinformatic method that reveals co-functionality and co-expression of genes. Genome Research 22:714–720. doi: 10.1101/gr.132647.111.Guerois [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock HR, Tabrizi SJ, Cooper JM, and V Schapira AH (1998). The influence of nuclear background on the biochemical expression of 3460 Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Annals of Neurology 44:187–193. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BS, Burrus CR, Ji C, Hahn MW, and Montooth KL (2015). Similar Efficacies of Selection Shape Mitochondrial and Nuclear Genes in Both Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens. G3 (Bethesda, Md.) 5:1–45. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.016493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree LM, Samuels DC, de Sousa Lopes SC, Rajasimha HK, Wonnapinij P, Mann JR, Dahl HH, and Chinnery PF (2008). A reduction of mitochondrial DNA molecules during embryogenesis explains the rapid segregation of genotypes. Nat Genet 40:249–254. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J (2006). The role of mitochondrial respiration in physiological and evolutionary adaptation. Bioessays 28:890–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MM, Walker WF, Hernandez-Rosa E, and Nesti C (2009). Evidence for nuclear modifier gene in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 46:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobler R, Rogell B, Budar F, and Dowling DK (2014). A meta-analysis of the strength and nature of cytoplasmic genetic effects. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 27:2021–2034. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK (2014). Evolutionary perspectives on the links between mitochondrial genotype and disease phenotype. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 1840:1393–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Abiega KC, and Arnqvist G (2007). Temperature-specific outcomes of cytoplasmic-nuclear interactions on egg-to-adult development time in seed beetles. Evolution 61:194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Friberg U, and Lindell J (2008). Evolutionary implications of non-neutral mitochondrial genetic variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Maklakov AA, Friberg U, and Hailer F (2009). Applying the genetic theories of ageing to the cytoplasm: Cytoplasmic genetic covariation for fitness and lifespan. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22:818–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Meerupati T, and Arnqvist G (2010). Cytonuclear interactions and the economics of mating in seed beetles. Am Nat 176:131–140. doi: 10.1086/653671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumollard R, Duchen M, and Carroll J (2007). The Role of Mitochondrial Function in the Oocyte and Embryo. Current Topics in Developmental Biology doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)77002-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ellison CK, and Burton RS (2006). Disruption of mitochondrial function in interpopulation hybrids of Tigriopus californicus. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution 60:1382–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CK, and Burton RS (2008a). Genotype-dependent variation of mitochondrial transcriptional profiles in interpopulation hybrids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:15831–15836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CK, and Burton RS (2008b). Interpopulation hybrid breakdown maps to the mitochondrial genome. Evolution 62:631–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CK, and Burton RS (2010). Cytonuclear conflict in interpopulation hybrids: the role of {RNA} polymerase in {mtDNA} transcription and replication. Journal of evolutionary biology 23:528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes S, Coleman-Hulbert AL, a Hicks K, de Haan G, Martha SR, Knapp JB, Smith SW, Stein KC, and Denver DR (2011). Natural variation in life history and aging phenotypes is associated with mitochondrial DNA deletion frequency in Caenorhabditis briggsae. BMC evolutionary biology 11:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-walker A (2017). Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy : Are Mito-nuclear 205:1365–1372. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.196436/-/DC1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W (2008). A Mouse Model of Mitochondrial Disease Reveals Germline Selection Against Severe mtDNA Mutations. Science 958:958–962. doi: 10.1126/science.1147786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedorczuk K, Letts JA, Degliesposti G, Kaszuba K, Skehel M, and Sazanov LA (2016). Atomic structure of the entire mammalian mitochondrial complex I. Nature 538:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature19794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch TM, Zhao N, Korkin D, Frederick KH, and Eggert LS (2014). Evidence of positive selection in mitochondrial complexes I and V of the African elephant. PLoS ONE 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S. a, and Hurst LD (1996). Mitochondria and male disease. Nature doi: 10.1038/383224a0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garvin MR, Bielawski JP, Sazanov LA, and Gharrett AJ (2014). Review and meta-analysis of natural selection in mitochondrial complex I in metazoans. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 53. doi: 10.1111/jzs.12079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin MR, Templin WD, Gharrett AJ, Decovich N, Kondzela CM, Guyon JR, and Mcphee MV (2016). Potentially adaptive mitochondrial haplotypes as a tool to identify divergent nuclear loci. Methods in Ecology and Evolution:821–834. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12698 [DOI]

- Gemmell NJ, Metcalf VJ, and Allendorf FW (2004). Mother’s curse: the effect of mtDNA on individual fitness and population viability. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19:238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell N, and Wolff JN (2015). Mitochondrial replacement therapy: Cautiously replace the master manipulator. BioEssays 37:584–585. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genes OP, Wolf JB, Wolf JB, Van Der Sluis EO, Bauerschmitt H, Becker T, Mielke T, Frauenfeld J, Berninghausen O, Neupert W, Herrmann JM, et al. (2013). Evidence for compensatory evolution of ribosomal proteins in response to rapid divergence of mitochondrial rRNA. Molecular Biology and Evolution 5:310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoni M, Templeton AR, and Mishmar D (2009). Mitochondrial bioenergetics as a major motive force of speciation. Bioessays 31:642–650. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman LI, Wildman DE, Schmidt TR, and Goodman M (2004). Accelerated evolution of the electron transport chain in anthropoid primates. TRENDS in Genetics 20:578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Wu M, Guo R, Yan K, Lei J, Gao N, and Yang M (2016). The architecture of the mammalian respirasome. Nature:1–16. doi: 10.1038/nature19359 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hadjivasiliou Z, Lane N, Seymour RM, and Pomiankowski A (2013). Dynamics of mitochondrial inheritance in the evolution of binary mating types and two sexes. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society 280:20131920. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JS, and Burton RS (2006). Tracing hybrid incompatibilities to single amino acid substitutions. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23:559–564. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havird JC, Hall MD, and Dowling DK (2015a). The evolution of sex: A new hypothesis based on mitochondrial mutational erosion: Mitochondrial mutational erosion in ancestral eukaryotes would favor the evolution of sex, harnessing nuclear recombination to optimize compensatory nuclear coadaptation J. BioEssays 37:951–958. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havird JC, and Sloan DB (2016). The roles of mutation, selection, and expression in determining relative rates of evolution in mitochondrial versus nuclear genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33:3042–3053. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havird JC, Trapp P, Miller C, Bazos I, and Sloan DB (2017). Causes and consequences of rapidly evolving mtDNA in a plant lineage. Genome Biology and Evolution doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Havird JC, Whitehill NS, Snow CD, and Sloan DB (2015b). Conservative and compensatory evolution in oxidative phosphorylation complexes of angiosperms with highly divergent rates of mitochondrial genome evolution. Evolution 69:3069–3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks KA, Denver DR, and Estes S (2013). Natural variation in Caenorhabditis briggsae mitochondrial form and function suggests a novel model of organelle dynamics. Mitochondrion 13:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2014). Sex linkage of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes. Heredity 112:469–470. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2013.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2015a). Mitonuclear ecology. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32:1917–1927. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2015b). Mitonuclear ecology. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32:1917–1927. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2016). Mitonuclear coevolution as the genesis of speciation and the mitochondrial DNA barcode gap. Ecology and Evolution 6:5831–5842. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2017a). The mitonuclear compatibility species concept. Auk 134. doi: 10.1642/AUK-16-201.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE (2017b). The mitonuclear compatibility species concept. The Auk 134:393–409. doi: 10.1642/AUK-16-201.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill GE, and Johnson JD (2013). The mitonuclear compatibility hypothesis of sexual selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra LA, Siddiq MA, and Montooth KL (2013). Pleiotropic effects of a mitochondrial-nuclear incompatibility depend upon the accelerating effect of temperature in Drosophila. Genetics 195:1129–1139. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.154914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson G, Gomez-Duran A, Wilson IJ, and Chinnery PF (2014). Recent Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase the Risk of Developing Common Late-Onset Human Diseases. PLoS Genetics 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson G, Keers S, Yu Wai Man P, Griffiths P, Huoponen K, Savontaus M-L, Nikoskelainen E, Zeviani M, Carrara F, Horvath R, Karcagi V, et al. (2005). Identification of an X-chromosomal locus and haplotype modulating the phenotype of a mitochondrial DNA disorder. American journal of human genetics 77:1086–1091. doi: 10.1086/498176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti P, Morrow EH, and Dowling DK (2011a). Experimental {Evidence} {Supports} a {Sex}-{Specific} {Selective} {Sieve} in {Mitochondrial} {Genome} {Evolution}. Science 332:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1201157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti P, Morrow EH, and Dowling DK (2011b). Experimental evidence supports a sex-specific selective sieve in mitochondrial genome evolution. Science 332:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1201157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S (1998). Complete Structure of the 11-Subunit Bovine Mitochondrial Cytochrome bc1 Complex. Science 281:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, and Ballard JWO (2003). Mitochondrial genotype affects fitness in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 164:187–194. doi: 10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[0527:domdin]2.0.co [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JE, Piganeau G, and Eyre-Walker A (2016). The rate of adaptive evolution in animal mitochondria. Molecular ecology 25:67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji F, Sharpley MS, Derbeneva O, Alves LS, Qian P, Wang Y, Chalkia D, Lvova M, Xu J, Yao W, Simon M, et al. (2012). Mitochondrial DNA variant associated with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy and high-altitude Tibetans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202484109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon L, and Moraes CT (1997). Expanding the functional human mitochondrial DNA database by the establishment of primate xenomitochondrial cybrids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94:9131–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer DC, and Mira a (1999). Mitochondria and germ-cell death. Nature 400:125–126. doi: 10.1038/22026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong S, Srivathsan A, Vaidya G, and Meier R (2012). Is the COI barcoding gene involved in speciation through intergenomic conflict? Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62:1009–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life In. Oxford University Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Lane N (2011). Mitonuclear match: Optimizing fitness and fertility over generations drives ageing within generations. Bioessays 33:860–869. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N, and Martin W (2010). The energetics of genome complexity. Nature 467:929–934. doi: 10.1038/nature09486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Yen K, and Cohen P (2013). Humanin: A harbinger of mitochondrial-derived peptides? Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 24:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Zeng J, Drew BG, Sallam T, Martin-Montalvo A, Wan J, Kim SJ, Mehta H, Hevener AL, De Cabo R, and Cohen P (2015). The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metabolism 21:443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA (2003). The Cytoplasmic Factor in Plant Speciation. Systematic Botany 28:5–11. doi: 10.1043/0363-6445-28.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo LF, Hou CC, and Yang WX (2013). Nuclear factors: Roles related to mitochondrial deafness. Gene 520:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M (1997). Mutation accumulation in nuclear, organelle, and prokaryotic transfer RNA genes. Molecular biology and evolution 14:914–925. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, and Blanchard JL (1998). Deleterious mutation accumulation in organelle genomes. Genetica 102:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Butcher D, Bürger R, and Gabriel W (1993). The mutational meltdown in asexual populations. Journal of Heredity 84:339–344. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Gutierrez N. Marti, Morey R, Van Dyken C, Kang E, Hayama T, Lee Y, Li Y, Tippner-Hedges R, Wolf DP, Laurent LC, and Mitalipov S (2016). Incompatibility between Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genomes Contributes to an Interspecies Reproductive Barrier. Cell Metabolism 24:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen MH, Grady JP, Ng YS, Alston CL, Gorman GS, Taylor RW, McFarland R, and Turnbull DM (2017). Decreased male reproductive success in association with mitochondrial dysfunction. European Journal of Human Genetics 25:1163–1165. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Chiotis M, Pinkert CA, and Trounce IA (2003). Functional respiratory chain analyses in murid xenomitochondrial cybrids expose coevolutionary constraints of cytochrome b and nuclear subunits of complex III. Molecular Biology and Evolution 20:1117–1124. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn CD, Holmbeck MA, Siddiq MA, Abt DN, Rand DM, and Montooth KL (2013). An Incompatibility between a Mitochondrial tRNA and Its Nuclear-Encoded tRNA Synthetase Compromises Development and Fitness in Drosophila. PLoS Genetics 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milot E, Moreau C, Gagnon A, Cohen AA, Brais B, and Labuda D (2017). Mother’s curse neutralizes natural selection against a human genetic disease over three centuries. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1:1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishmar D, Ruiz-Pesini E, Golik P, Macaulay V, Clark AG, Hosseini S, Brandon M, Easley K, Chen E, Brown MD, Sukernik RI, et al. (2003). Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:171–176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136972100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan RM, and Whitmarsh AJ (2015). Mitochondrial Proteins Moonlighting in the Nucleus. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 40:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JH, and Williams SM (2005). Traversing the conceptual divide between biological and statistical epistasis: Systems biology and a more modern synthesis. BioEssays 27:637–646. doi: 10.1002/bies.20236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales HE, Pavlova A, Amos N, Major R, Bragg J, Kilian A, Greening C, and Sunnucks P (2016). Mitochondrial-nuclear interactions maintain a deep mitochondrial split in the face of nuclear gene flow. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/095596 [DOI]

- Morales HE, Pavlova A, Joseph L, and Sunnucks P (2015). Positive and purifying selection in mitochondrial genomes of a bird with mitonuclear discordance. Molecular Ecology 24:2820–2837. doi: 10.1111/mec.13203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow EH, and Camus MF (2017). Mitonuclear epistasis and mitochondrial disease. Mitochondrion doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morrow EH, Reinhardt K, Wolff JN, and Dowling DK (2015). Risks inherent to mitochondrial replacement. EMBO reports 16:541–545. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman JA, Biancani LM, Zhu C, and Rand DM (2016). Mitonuclear Epistasis for Development Time and Its Modi fi cation by Diet in Drosophila 203:463–484. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.187286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabholz B, Ellegren H, and Wolf JBW (2013). High levels of gene expression explain the strong evolutionary constraint of mitochondrial protein-coding genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30:272–284. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada K, Sato A, Yoshida K, Morita T, Tanaka H, Inoue S, Yonekawa H, and Hayashi J (2006). Mitochondria-related male infertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:15148–15153. doi: 0604641103 [pii]\r 10.1073/pnas.0604641103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman M, and Taylor DR (2009). The causes of mutation accumulation in mitochondrial genomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276:1201–1209. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]