Abstract

The fetal heart undergoes its own growth and maturation stages all while supplying blood and nutrients to the growing fetus and its organs. Immature contractile cardiomyocytes proliferate to rapidly increase and establish cardiomyocyte endowment in the perinatal period. Maturational changes in cellular maturation, size, and biochemical capabilities occur, and require, a changing hormonal environment as the fetus prepares itself for the transition to extrauterine life. Thyroid hormone has long been known to be important for neuronal development, but also for fetal size and survival. Fetal circulating 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) levels surge near term in mammals and are responsible for maturation of several organ systems, including the heart. Growth factors like insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulate proliferation of fetal cardiomyocytes while thyroid hormone has been shown to inhibit proliferation and drive maturation of the cells. Several cell-signaling pathways appear to be involved in this complicated and coordinated process. The aim of this review is to discuss the foundational studies of thyroid hormone physiology and the mechanisms responsible for its actions as we speculate on potential fetal programming effects for cardiovascular health.

Keywords: Fetal programming, Thyroid hormone, Cardiomyocyte maturation, Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 25 years, the many roles that thyroid hormone plays in regulating fetal development have come to light. Because maternal plasma thyroid hormone levels influence fetal levels, abnormal maternal thyroid hormone levels can lead to abnormal development of the brain, heart, lung and pancreas in the fetus (Abalovich et al., 2002, Calvo et al., 2002, Casey et al., 2007, Harris et al., 2017, Chan et al., 1998, Polk et al., 1995, van Tuyl et al., 2004, Oppenheimer and Dillmann, 1978, Zimmerman, 1999, Lorijn et al., 1980). The purpose of this review is to summarize the role of thyroid hormone in regulating the growth and maturation of the fetal myocardium and to highlight features of thyroid hormone function that likely impart elevated susceptibility for adult onset disease.

David Barker, his colleagues, and now many others have shown that low term birthweight is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood (Barker et al., 1989, Barker, 1995). We now know the importance of the prenatal environment in determining risk for CVD throughout life via a process known as fetal programming (Gluckman et al., 2008, Barker and Osmond, 1988). There is increasing evidence that fetal stressors, including poor nutrition and hypoxia, lead to detrimental changes in heart and blood vessels and elevated disease risk for life.

The capacity of cardiomyocytes to proliferate over the life course has been controversial, in part because of fraudulent research (Beltrami et al., 2003, Anversa et al., 2006) which reported that stem cells were able to regenerate cardiomyocytes in the adult heart of humans and rodents and repair regions of damage. In sheep, cardiomyocytes go through a maturation phase during the perinatal period whereupon cell division is slowed significantly. Jonker et al. showed myocyte number is reduced in both ventricles immediately before term, but proliferation increases myocyte number in the neonatal right ventricle (Jonker et al., 2015). There is evidence that human cardiomyocytes are able to divide very slowly over most of the adult lifespan in order to replace low levels of cellular loss (Bergmann et al., 2009). Bergmann’s study reports that fewer than 50% of all cardiomyocytes are slowly exchanged over a normal life span with a gradual decrease from 1% turning over annually at the age of 25 to 0.45% at the age of 75. Studies of proliferation dynamics show that the number of heart cells is constant from early postnatal life into old age, when cell dropout begins to occur. Thus, cardiomyocyte proliferation during the prenatal period is important in determining the lifelong endowment of the myocardium. If the generative capacity of the myocardium is lost before it acquires an optimum number of cardiomyocytes, the heart could be vulnerable for coronary artery disease or heart failure in later life (Thornburg et al., 2010). A low cardiomyocyte endowment is especially important because cardiomyocyte loss is a hallmark of heart failure. Cardiovascular disease is the number 1 cause of death worldwide with a projected medical cost of $1.1 trillion by 2035 in the recent American Heart Association report (2017) and heart failure represent a significant portion of that cost.

Low birth weight is associated with an increased risk for coronary artery disease (Barker et al., 1989, Rich-Edwards et al., 2005) as well as type 2 diabetes (Barker, 1999b, Barker, 1999a), hypertension (Barker and Osmond, 1988), hypercholesterolemia (Barker et al., 1993), and hypercoagulopathies (Fall et al., 1995, Martyn et al., 1995). Babies that experienced intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are prone to have hearts that suffer detrimental changes over the lifespan. Hearts of 5-year olds who were IUGR had changes in cardiac shape, reduced stroke volume and increased heart rate (Crispi et al., 2010). The hearts were also characterized by abnormal systolic and diastolic function. The cardiomyocyte population is clearly affected not only through changes in cardiac loading conditions but also by the chemical environment. Fetuses that grow slowly suppress the proliferation of cardiomyocytes and their rate of maturation. In such cases, the myocardium suffers a cardiomyocyte deficit and is metabolically compromised at birth (Louey et al., 2007, Morrison et al., 2007).

It is known that maternal thyroid function can influence the growth and maturation of fetal organs (Alemu et al., 2016). We have shown that in the ovine fetus, T3 is an important driver of fetal myocardial maturation (Chattergoon et al., 2012a). This finding may be important for human fetal development. Up to 10% of all pregnancies are afflicted by some form of thyroid dysfunction (Alemu et al., 2016, Marx et al., 2008, Wang et al., 2011). Treatment is recommended whenever maternal thyroid stimulating hormone levels are high and free thyroxine (T4) is low (hypothyroidism) or when the opposite is found (hyperthyroidism) (Casey and Leveno, 2006). The discovery that subclinical hypothyroidism also leads to intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm birth, and permanent neurological deficits in offspring has given rise to a call by national organizations for screening of all pregnant women to determine plasma thyroid status (Casey et al., 2006, Casey and Leveno, 2006, Gharib et al., 2005, Haddow et al., 1999) but such screening has yet to become routine (Casey, 2014).

A few studies suggest the importance of thyroid hormone in fetal programming, 1) Small for gestational age babies have elevated plasma free 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) levels postnatally (Radetti et al., 2004); 2) Ethyl alcohol exposure in the fetal rat depresses thyroid hormone levels in the adult; 3) Fetal T4 exposure in rats alters their thyroid hormone levels as adults (Wilcoxon and Redei, 2004); 4) Small body size at birth predicts hypothyroidism in offspring and adult women (Kajantie et al., 2006); 5) Thyroid hormones in breast milk may alter the set point for other hormone levels in infants and as adults (Phillips et al., 1993); and 6) Hypothyroidism in sheep stimulates increases in fetal pancreatic beta cell mass through proliferation (Harris et al., 2017). This group of facts suggests that early life thyroid hormone levels are important for long term health of offspring.

We should not be surprised that the thyroid system is important in regulating development in mammals. Thyroid hormone was the first morphogen to be discovered when in 1912, J.F. Gudematsch, a Cornell anatomist, showed that adult thyroid gland extract stimulated the rapid metamorphosis of tadpoles into frogs (Brown and Cai, 2007). It is now known that the vast array of tissues that change dramatically as the aquatic tadpole transforms into a terrestrial frog are under the control of thyroid sensitive genes. The muscles in the tail of the tadpole are, for example, resorbed within mere hours, while muscles in the limb are stimulated to grow; both processes under the regulation of T3 (Brown and Cai, 2007). Mammals do not, of course, develop by metamorphosis as found in anurans. However, many of the thyroid receptors and their binding partners are conserved among vertebrates from fish to mammals (Bertrand et al., 2004). Aquatic fetal mammals, like tadpoles, must prepare for post-natal terrestrial life. Thus, it is possible that many other T3-driven developmental processes among fetal mammals are important in the birth transition but remain undiscovered. In this review we will focus on the role of thyroid hormones on cardiovascular development and potential long-term consequences for postnatal health.

SHEEP AS A MODEL FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DEVELOPMENTAL STUDIES

The study of the mechanisms that regulate cardiomyocyte growth has required animal models because of the understandable rarity of viable cardiac tissue or blood samples from human fetuses and infants. The fetal sheep model allows for well-tolerated chronic surgical instrumentation, serial blood sampling and continuous measurement of hemodynamic factors. Experimental alterations in the fetal endocrine or hemodynamic environments can be utilized to determine the impact of cardiomyocyte growth and functional cardiac outcomes.

Nevertheless, the interspecies differences among sheep, humans and rodents must be taken into account when interpreting findings. To begin with, placental structure and function are widely variable among members across the mammalian phylogenetic scale. These differences may influence the fetal nutritional, hemodynamic and hormonal milieu in which the heart develops (Barry and Anthony, 2008, Mu et al., 2008, Jonker et al., 2007a). Rodents have litters of up to 10 pups or more and their location in the uterine horn influences nutrient delivery and their ultimate size (Rennie et al., 2015, McLaurin and Mactutus, 2015). In contrast, sheep and humans have few offspring with each pregnancy. The longer gestation of sheep (145 days vs. 21 days in rats and mice) offers the opportunity to conduct experiments in a similar developmental time-frame to compare to humans. Rodent pups are altricial and thus, very immature at birth. They are hairless, have eyes that are sealed and the final steps of heart maturation stages occur after birth, rather than prenatally as for humans and sheep (Soonpaa et al., 1996, Jonker et al., 2007b). The fetal thyroid hormone system is similar between humans and sheep.

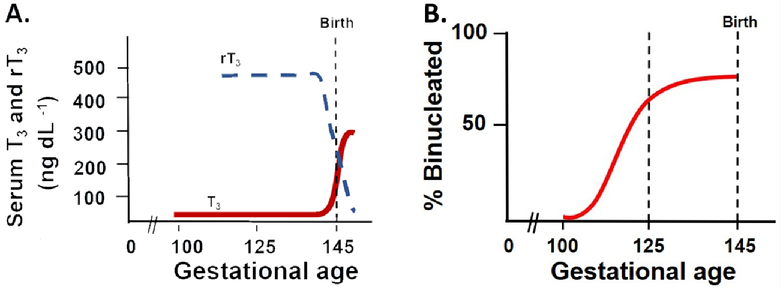

The ovine thyroid gland begins to secrete T4 around 50 days gestational age (dGA) (Hopkins and Thorburn, 1972, Thorburn and Hopkins, 1973). In humans, the fetus secretes T4 by 12 weeks gestation (Fisher and Polk, 1989, Becks and Burrow, 1991) and in rats it is detectable by 13–16 days of gestation (term is 21) (Perez-Castillo et al., 1985). Serum T3 concentrations are low in sheep and human fetuses over most of gestation. In the sheep, there is a slow increase in serum T3 concentrations during the last third of gestation. Serum T3 concentrations then increase rapidly during the week immediately preceding parturition (the prenatal T3 surge) as shown in Figure 1A. The plateau phase coincides with the final developmental window for various organs before birth, including the heart (Figure 1B). In the human fetus serum T3 is essentially unmeasurable until about 30 weeks gestation, after which time serum T3 increases to a mean concentration of about 50 ng dL−1 at term (Fisher, 1977). During the first 4–6 hours after birth, serum T3 concentrations increase another 3–6-fold (Fisher et al., 1973, Abuid et al., 1973). Rodents appear to have a T3 surge which occurs after birth (Chanoine et al., 1993). The fetal sheep model is a good representation of human development with many organs sharing similar growth trajectories, including the heart (Wu et al., 2006). In this review, we primarily focus on data from sheep.

Figure 1.

Circulating triiodothyronine (T3) and reverse T3 (rT3) levels in normal fetal sheep (Polk 1995) (A). The prepartum surge is driven by the prepartum cortisol surge stimulating deiodinase expression and conversion from T4. Cortisol stimulates D1 activity and suppresses D3 activity. Representation of the normal timing and changes in binucleation of fetal sheep left ventricular cardiomyocytes (B). Binucleation is an index of terminal differentiation, after which cells exit the cell cycle and no longer divide. In the fetal sheep heart this process begins just after 100 days gestational age and is ~75% binucleated at the time of birth. The dashed line at 125 days gestational age represents the timing of studies discussed in this review (Polk 1995, Jonker et al., 2007 and Chattergoon et al., 2012).

THYROID HORMONE IN DEVELOPMENT AND ITS METABOLISM

There has been a significant body of work pointing to the importance of thyroid hormones in development and postnatal organ function. Prematurity is associated with low circulating thyroid hormone levels (T3 and T4) (Williams et al., 2004). The fetus is dependent on maternal transfer of T4 and T3 prior to the fetal gland secreting them, which is particularly important in early development and embryogenesis during the early phases of central nervous system development (Fisher, 2008). In most mammals, extrauterine adaptation is supported by a cortisol surge near term mediated by increased cortisol production by the fetal adrenal gland and reduced conversion to cortisone. Cortisol increases deiodinase expression and activity in several fetal tissues (Wu et al., 1978). Three deiodinase enzymes, types I, II, and III (D1, D2, and D3, respectively), are found in both fetal and adult tissues (Bianco and Kim, 2006, Bianco et al., 2002). See Figure 2.Their expression is tissue specific (Brent, 2012) and is affected by glucocorticoids (Forhead et al., 2006). The activity of thyroid hormone is partially regulated by removal of iodine moieties from precursor molecules by the iodothyronine deiodinases. The enzymes are members of dimeric integral membrane thioredoxin family, containing proteins that activate or inactivate thyroid hormone by acting upon the phenolic or the tyrosil rings of the iodothyronines; each deiodinase prefers the ring from which it removes the iodine group (Bianco and Kim, 2006, van der Spek et al., 2017). Figure 2 illustrates the conversion of the T4 and T3 molecules by the specific deiodinases.

Figure 2.

Basic deiodinase reactions regulating thyroid hormone metabolism. The reactions catalyzed by the deiodinases remove iodine moieties from the phenolic (outer rings) or tyrosil (inner rings) rings of the iodothyronines. These pathways can activate T4 by transforming it into T3 via D1 or D2 or prevent it from being activated by converting it to the metabolically inactive form, reverse T3 (rT3) via D1 or D3. T2 is an inactive product common to deiodination of both T3 and rT3 and is rapidly metabolized by further deiodination (Bianco and Kim 2006 and van der Spek et al., 2017).

D1 is a 5’-monodeiodinase which activates or inactivates T4 to T3 or reverse T3 (rT3), respectively. It is present in the fetal liver, kidney, thyroid and pituitary glands; the production of T3 by liver D1 is thought to be the main source of circulating T3 (Polk, 1995). D2 is also a 5’-deiodinase that generates T3 from T4, though it is primarily found in the brain, pituitary gland, placenta, and brown adipose tissue (Polk, 1995). D2 conversion to T3 tends to be for that specific organ use rather than contributing to circulating levels. D3 is a 5’-monodeiodinase that inactivates T3 by conversion to T2 and metabolizes T4 to reverse T3 (rT3). D3 is found in liver, kidney, skin, uterus and placenta. It plays an important role in placental clearance of maternal thyroid hormones and protects the fetus by limiting its exposure to maternal thyroid hormones. Fetal thyroid hormone levels and metabolism are characterized by a predominance of D3 and rT3 (Polk, 1995, Polk et al., 1988). While it is the primary circulating T4 metabolite in development it has little activity. D1 activity is low through most of gestation therefore circulating T3 levels in the fetus are relatively low. Elevated glucocorticoids reduce D3 and increase D1 activity. In fetal sheep, kidney and liver D1 activities increase and placental D3 activity decreases in the 2 weeks prior to birth (Forhead et al., 2006). Forhead et al has shown that those changes were induced by prepartum cortisol surge and that premature maternal administration of the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone yielded the same effect (Forhead et al., 2006, Forhead et al., 2007). This results in overall preferential deiodination of T4 to T3 and reduced clearance of T3 leading to a rise in fetal plasma T3 levels.

Studies by Breall et al in the 1980s showed that, as expected, fetal sheep that were thyroidectomized 2–3 weeks prior to birth or term delivery did not undergo the T3 surge (Breall et al., 1984). Forhead et al. showed that thyroidectomy of the sheep fetus abolished the prepartum rise in fetal plasma T3 but not the cortisol surge (Forhead et al., 2000). They also identified a role for thyroid hormone in controlling growth hormone receptor, IGF-1 and IGF-2 expression in the fetal liver which is important for overall somatic growth (Forhead et al., 2000, Forhead et al., 1998). When thyroidectomized, fetuses also showed reduced heart rate, cardiac output, oxygen consumption, and lower blood flow to the peripheral circulation in the first 6 hours after delivery (Breall et al., 1984). These foundational studies indicate that plasma thyroid hormone levels in the 2–3 weeks prior to delivery, and not just the prepartum and postnatal increase, are important for cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments required to prepare the fetus for extrauterine life.

CARDIOMYOCYTE PROLIFERATION AND MATURATION

The question of what determines the numbers of cells in a mature organ has not been answered. Some organs have regenerative powers, like liver, but most have little. However, in spite of reports on the presence of stem-like cells that can be recruited or that are resident in the myocardium, the heart cannot adequately replace cardiomyocytes when it really counts, following an infarction or in heart failure when cardiomyocytes become ineffective and are dying.

The developing heart is continuously growing to meet the hemodynamic and metabolic needs of the growing fetus while cardiomyocytes continue through their own growth and maturation processes. During the first two-thirds of gestation the ovine heart grows by cardiomyocyte division before the majority of them leave the cell cycle permanently in late gestation. During this high proliferative stage cardiomyocytes are mononucleated. Figure 1B shows that an increasing number of cardiomyocytes transition into terminal differentiation in the last third of gestation. This process begins around 110 days gestational age (dGA) and continues to birth (~145 dGA) (Burrell et al., 2003, Jonker et al., 2007b). This process is marked by karyokinesis, the formation of a second nucleus, without cell division; the resulting binucleated cardiomyocyte permanently exits the cell cycle (G0). At birth, some 75% of ovine cardiomyocytes have become binucleated and can no longer divide (Jonker et al., 2007b). The mechanisms that underlie the normal transition of fetal cardiomyocyte growth from a predominantly hyperplastic to a hypertrophic mode are not known. The maturation process results in the gradual replacement of the mononucleated population by a binucleated cell population that can grow only by hypertrophy (increase in cell size). Terminal differentiation is about 75% complete at term (Figure 3) in the sheep (Jonker and Louey, 2016, Jonker et al., 2015). In mice and rats, the terminal differentiation process occurs in the newborn and is complete by 2 weeks of life (Clubb and Bishop, 1984, Cluzeaut and Maurer-Schultze, 1986, Li et al., 1996). Less is known about the maturation process in the human. The human heart has a higher population of mononucleated cardiomyocytes but most of them are polyploid and appear to be terminally differentiated. In addition, the human myocardium also has binucleated cardiomyocytes (Schmid and Pfitzer, 1985, Ahuja et al., 2007), but only to ~8–14% at birth (Rakusan, 1984) which increases up to 33% in early childhood. However, because humans are born in a more mature state than are altricial rats and mice, the human heart growth patterns are more closely related to the relative growth and maturational timing of the sheep compared to rodents.

Figure 3.

Cardiomyocyte growth in the fetal heart. Mononucleated cardiomyocytes are capable of proliferation but can also become binucleated. Binucleated cardiomyocytes are unable to undergo further cytokinesis. Both mononucleated and binucleated cardiomyocytes can undergo cellular enlargement (length or width changes) during hypertrophic growth.

Several stressors in utero can reduce cardiomyocyte numbers for life (Corstius et al., 2005, Li et al., 2003). As mentioned above, having a reduced cardiomyocyte endowment puts an individual at greater risk for cardiovascular disease and impaired recovery from an event like myocardial infarction. The terminal differentiation process, as evidenced by binucleation rates begins almost 30 days prior to the prepartum T3 surge. T3 becomes detectable at about 110dGA (Fraser and Liggins, 1988), suggesting that T3 is an important contributor to the maturation process. The effect of T3 on proliferation of isolated cells from fetal sheep hearts has been studied at 2 developmental ages that represent 100% mononucleated cardiomyocytes (100dGA) and ~ 50% mononucleated (135dGA; ~10d prior to birth). The proliferation rates are different between the two ages with the younger cells having a 10–12% rate over 24 hour of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation compared to 1–2% in 135dGA cells. We found that T3 inhibits cardiomyocyte proliferation when in the presence of a physiological growth stimulus like insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 is an important stimulant of cardiomyocyte growth throughout gestation.

We reasoned that immature cardiomyocytes that are highly proliferative, as at 100dGA and earlier, would be necessarily immune to the inhibitory effects of T3. We hypothesized that the viability of the fetus might be at stake if heart cells could not divide rapidly at a time when the cardiomyocyte endowment is being established for life. However, we proved our hypothesis wrong. We found that T3 has a stronger inhibitory effect on 100 day cardiomyocytes than in near term cells (Chattergoon et al., 2012b). This was an unexpected finding. The data suggest that maternal, and therefore fetal, hyperthyroidism would leave the fetal heart with far fewer cardiomyocytes than required for optimal function over the life course.

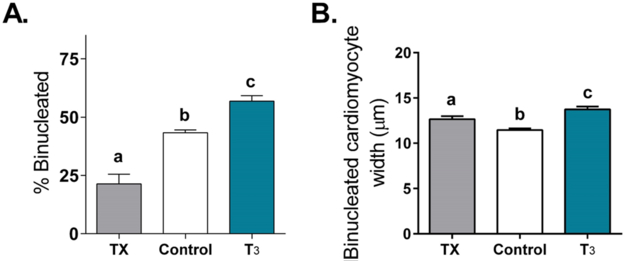

The effect of T3 on fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation was tested in vivo. T3 (54μg/day) was infused into the circulation of fetal sheep from 125–130dGA when T3 levels are very low. This is about15d prior to the normal T3 surge that occurs near the end of gestation. Hearts from these fetuses were not bigger or smaller than from control fetuses, or when normalized to body weight. However, cardiomyocyte proliferation was reduced, as indicated by lower Ki-67 expression, as the cell cycle inhibitor p21 was elevated (Figure 4). Binucleation rates were increased under the influence of T3 and cells were enlarged, particularly with increased width (Figure 5). In addition, several genes related to hypertrophy and maturation were increased. For example, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2A (SERCA2A) were increased. This is consistent with our in vitro studies showing that p21 levels are elevated and the cell cycle promoter, cyclin D1 levels were decreased after 24 hours of T3 treatment over a range of dose (Chattergoon et al., 2007, Chattergoon et al., 2012b).

Figure 4.

Cell cycle activity, measured by Ki-67, decreased in both T3-infused and TX fetuses (A). Mitotic activity of myocytes, measured by phospho-histone 3 expression, was decreased in both T3-infused and TX fetuses. T3 also elevated p21 protein levels, inhibiting the cell cycle (C). Bars that do not share letters are significantly different (P <0.05); n=8. Data are mean±SEM (Chattergoon et al., 2012).

Figure 5.

Increased circulating T3 promotes terminal differentiation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Elevated T3 concentration increased the portion of LV myocytes that were binucleated (A) and caused myocytes to be wider (B; hypertrophy). Cardiomyocytes from TX fetuses were also wider to maintain wall stress and cardiac function. Bars that do not share letters are significantly different (P <0.05); n=8. Data are mean±SEM (Chattergoon et al., 2012).

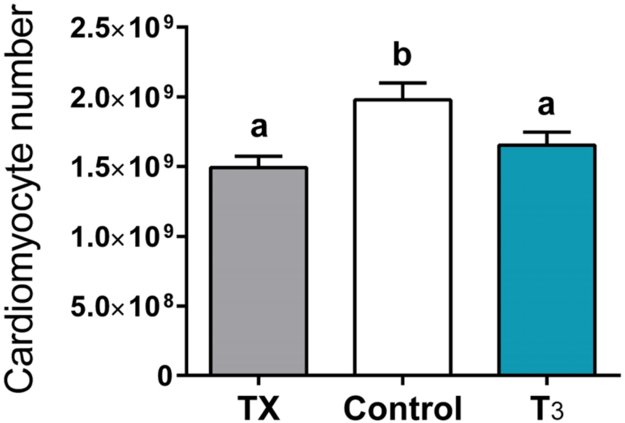

To determine whether some basal level of T3 was required to support cardiomyocyte growth and maturation, we thyroidectomized (TX) a group of fetuses. Thyroidectomized fetuses showed lower rates of proliferation of cardiomyocytes and binucleation (Figures 4 and 5) as well as reduced cardiac mass when corrected for body weight (Chattergoon et al., 2012a). The characteristics are similar to a heart that has been grown under the condition of placental insufficiency where it is nutrient deprived (Louey et al., 2007). Interestingly, cardiomyocytes from TX fetuses were enlarged (Figure 5). We speculate that under TX conditions, cardiomyocytes responded to wall thinning because of the cardiomyocyte deficit which led to elevated wall stress and a hypertrophic stimulus. Interestingly, we also noted a reduced estimated cardiomyocyte number in hearts from both TX and T3-infused (Figure 6) (Thornburg, 2015). The mechanism of this reduction is different between the two groups where T3 is required for normal growth as reflected by reduced cardiac mass in the TX group. These and findings of others showed that the loss of T3 support results in reduced glucose transport genes, contractile protein expression, hypertrophic genes, and calcium handling genes (Segar et al., 2013, Chattergoon et al., 2012a, van Tuyl et al., 2004, Mai et al., 2004) which all contribute to normal cardiac growth and function. T3 stimulates pathways of terminal differentiation which inhibits cardiomyocyte proliferation. The evidence suggests that fetal thyroid hormone concentrations must be kept within a narrow window of concentration, not too high and not too low, to produce a normal heart.

Figure 6.

Elevated or loss of circulating T3 levels significantly reduced cardiomyocyte number and overall endowment, though the mechanism of inhibition of proliferation is different between the two. T3 is needed to support cellular growth and to stimulate the pathways of maturation and terminal differentiation. Bars that do not share letters are significantly different (P <0.05); n=8. Data are mean±SEM (Thornburg 2015).

SIGNALING PATHWAYS

Extracellular control of cell cycle progression is achieved in all cells by the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Wilkinson and Millar, 2000, Chang and Karin, 2001). In particular, ERK stimulates production of cyclin D1 (Graves et al., 2000) and facilitates formation of a cyclin D1-Cdk4 complex to increase the transcription of growth-promoting genes to trigger the G1/S transition of the cell cycle. T3 is known to stimulate the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) and AKT/PKB pathways (Sundgren et al., 2003a, Sundgren et al., 2003b, Chattergoon et al., 2014, Hu et al., 2003, Kuzman et al., 2005b). ERKs are one member of the MAPK family that are associated with cardiomyocyte proliferation in the fetal heart. When the ERK signaling cascade is inhibited, pro-proliferation stimulators like IGF-1 for example are unable to promote cell division. Furthermore, AKT signaling is required for IGF-1 to stimulate proliferation in fetal sheep cardiomyocytes (Sundgren et al., 2003a, Chattergoon et al., 2014).

AKT signaling and cardiomyocyte survival

Barreto-Chaves’ group has shown that normal T3 status is important to maintain appropriate angiotensin receptor levels in the immature rodent heart (Diniz et al., 2009). They also showed that the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) mediates thyroid hormone-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through the AKT/glycogen synthase kinase-3β/mammalian target of rapamycin (AKT/GSK-3β/mTOR) pathways in primary cultures of neonatal rat (1–3 days old) cardiomyocytes. Gerdes’ research group has studied the role of T3 in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte signaling and survival (Kuzman et al., 2005a). Under serum-starved conditions neonatal cardiomyocytes underwent loss of sarcomeric structure and apoptosis quantified by histology, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, DNA laddering, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Kuzman et al., 2005a). The addition of T3 rescued this effect via the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/AKT/ GSK-3β (PI3K/AKT/ GSK-3β) pathway. It was attenuated by LY294002 (a specific PI3K inhibitor). These studies were carried out in postnatal rodent cardiomyocytes that, as noted above, are in the different growth phase than late-gestation fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. However, they offer evidence that immature cardiomyocytes require T3 to signal through each of several pathways. However, it is not known whether cardiomyocytes from newborn rodents use the same pathways under the same conditions as do prenatal cells in large mammals like sheep and humans because T3 has different effects on fetal sheep cardiomyocytes.

Interaction with IGF-1

As discussed above, T3 exerts a strong inhibitory effect on proliferation of ovine cardiomyocytes at the two stages that we have studied most (100 and 135dGA). We showed that IGF-1 stimulated the proliferation rates of 135dGA sheep cardiomyocytes by nearly four-times in vitro, which caused a 30% increase in cardiac mass when administered in vivo (Sundgren et al., 2003a). When T3 and IGF-1 were given alone in culture, they each stimulated phosphorylation of both ERK and AKT (Figure 7). In the younger mononucleated cells the combination of the two (T3+IGF-1) led to suppression of both BrdU uptake and phosphorylation of ERK and AKT (Chattergoon et al., 2014). In other words, while IGF-1 would ordinarily stimulate proliferation via ERK and PI3K pathways, when T3 levels are also elevated, proliferation stops. In older 135dGA cardiomyocytes with a mixed cell population in terms of maturation, T3+IGF-1 led to suppression of BrdU uptake but a super stimulation of ERK and AKT well above the levels of T3 or IGF-1 alone (Chattergoon et al., 2014). This high level of stimulation was an unexpected finding. Upon further investigation, histology revealed that even the binucleated cells, which can no longer divide, were highly positive for phosphorylated ERK and AKT and thus contributed to the overall signal. This suggests that cell signal patterning changes with maturation so that the signaling outcomes of IGF-1 and T3 stimulation lead to different patterns of phosphorylation and different outcomes than was found at earlier ages.

Figure 7.

MAPK and PI3K signaling analysis in 100dGA (A-C) and 135dGA cardiomyocytes (D-F). Western blot analysis shows that IGF-1 (1μg/ml) and T3 (1.5nM) each separately leads to phosphorylation of ERK (A,D), AKT (B,E), and p70 S6K (C,F). IGF-1 activates phosphorylation these proteins to a greater degree than T3 in 100dGA cells, but equally in 135dGA cells. The combination of T3 and IGF-1 in 100dGA cardiomyocytes reduces phosphorylation of each protein to half that of IGF-1 alone. The combination of T3 and IGF-1 in 135dGA cardiomyocytes stimulates further activation of ERK and AKT in a “super stimulatory way.” Bars that do not share letters are significantly different (P <0.05); n=8. Data are mean±SEM (Chattergoon et al., 2014).

In the presence of IGF-1, T3 and LY29004 (PI3K inhibitor), p-p70 S6K levels in younger cardiomyocytes were higher than those found under the same conditions with the ERK inhibitor, U0126 (p<0.05). These data are compatible with the hypothesis that p-p70S6K is more tightly linked to the ERK cascade than to the PI3K cascade at this stage of development. In older 135dGA cardiomyocytes, both inhibitors resulted in a ~50% reduction in the signaling of the alternate pathway suggesting that when cells are treated with T3 and IGF-1 together, both the ERK and AKT pathways are important in bringing about a cellular response. Perhaps, these well-established pathways that were required for cell growth at younger ages may promote hypertrophy or metabolic functions in the more mature cells (Chattergoon et al., 2012a, Kehat and Molkentin, 2010, Matsui et al., 2003). The data suggest that when physiological levels of T3 are normally low, cells are designed to proliferate under the influence of IGF-1, which is predominant throughout development. As the older cardiomyocytes become exposed to both hormones when T3 levels rise, they may require stimulation of both pathways for normal maturation.

As mentioned above, fetal sheep given exogenous T3 for 5 days had increased phosphorylation of ERK, AKT and mTOR in their cardiomyocytes (Chattergoon et al., 2012a). TX did not result in changes in the phosphorylation of these signaling molecules. In a study by the Segar group, a restrictive pulmonary artery band (PAB) was applied in fetuses at the time of thyroidectomy so that the fetuses grew into an enhanced constriction (Segar et al., 2013, Olson et al., 2008). They noted that markers of cellular proliferation but not apoptosis or expression of growth-related genes were lower in the TX and TX+ PAB groups relative to thyroid-intact animals. They concluded that in the late-gestation fetal heart thyroid hormone is required for adaptive fetal cardiac growth in response to pressure overload.

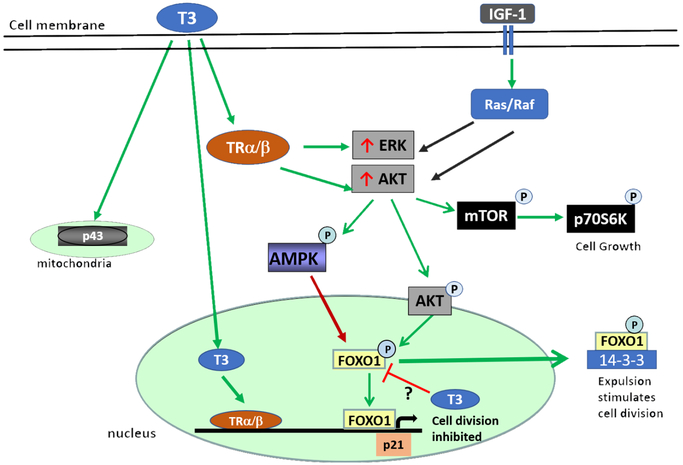

Potential of FOXO1-p21 interaction

We have identified a role for ERK and AKT signaling that results in inhibition of the cell cycle and increased levels of p21 and reduced cyclin D1. This occurs when T3 levels are elevated. There is a wide array of possible effectors but we believe that the Forkhead box O (FOXO) protein is a key intermediate. The family includes 1, 3, 4 and 6; FOXO1 is an important factor in cardiac equilibrium (Puthanveetil et al., 2013). It plays an important role in cell cycle arrest, oxidative stress resistance, cell survival, energy metabolism, and cell death in the heart (Puthanveetil et al., 2011, Puthanveetil et al., 2010, Maiese et al., 2009). The transcription factor, FOXO1, is an effector of the phosphatidylinositol- 3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway which can link growth and metabolism in some cells (Vander Heiden et al., 2009, Ward and Thompson, 2012, Ronnebaum and Patterson, 2010) as in Figure 8. PI3K signaling inhibits FOXO1 through AKT-mediated phosphorylation at Ser256 leading to its nuclear exclusion and inactivation (Salih and Brunet, 2008). The nuclear export is trafficked by 14–3-3s which only binds FOXO in this phosphorylated state (Tzivion et al., 2011). Stress signals including AMPK and extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylate FOXO1 at sites different than AKT, disrupt binding to 14–3-3, leading to nuclear import and retention. FOXO1 can then induce transcription of a variety of downstream target genes that collectively inhibit proliferation and induce cell cycle withdrawal (Huang and Tindall, 2007). Direct downstream targets of FOXO1 include the cyclin kinase inhibitors, p21 and p27, which have also been implicated in cardiomyocyte cell cycle withdrawal after birth (Seoane et al., 2004, Bicknell et al., 2007, Nakamura et al., 2000). The role of FOXO1 and their regulation during cardiomyocyte cell cycle withdrawal is not well-characterized. T3 stimulates phosphorylation of AKT and ERK (Chattergoon et al., 2014) just like IGF-1, but also stimulates the cell cycle inhibitor, p21. FOXO1 activity could be the discriminatory key to different actions of T3 and IGF-1. Although T3 activates 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Irrcher et al., 2008), we speculate AMPK phosphorylates FOXO1 at a site that disrupts its nuclear export and allows T3 to arrest the cell cycle through p21. The specific mechanism by which T3 inhibits FOXO1 inactivation are not clear but one might be through sirtuins. Sirtuins are deacetylases and T3 has been shown to activate it through TRβ binding; one of the complex’s targets is FOXO1 (Singh et al., 2013).

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of T3-FOXO1 regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation. T3 signals by nuclear TRs, p43 in the mitochondria, and cytoplasmic TRs. T3 stimulates AKT and ERK just like IGF-1, but further stimulates p21. The PI3K and MAPK pathways stimulate FOXO1 differently. FOXO1 activity could be the discriminatory key to different actions of T3 and IGF-1. ERK or AMPK phosphorylates FOXO1 at a site that disrupts its nuclear export and results in nuclear retention, leading to p21 transcription. AKT-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO1 at Ser256 leads to its expulsion from the nucleus allowing proliferation to continue. The mechanism by which T3 prevents activated FOXO1 activity are unclear.

THYROID HORMONE RECEPTORS AND ACTIONS

Research into the signaling biology of thyroid hormone is a dynamic area of research at present because of newly discovered signaling pathways through which TH molecules stimulate cellular actions. The so-called classical or “genomic” pathways involve TH binding specific nuclear thyroid receptors (TR) which affect gene expression via thyroid hormone response elements (TRE). Thus, thyroid hormone receptors behave as ligand regulated transcription factors. In most species two thyroid receptors and their isoforms are expressed by separate genes that bind T3 and T4, (THRA (TRα) and THRB (TRβ)) (Yen, 2001, Schueler et al., 1990, Mai et al., 2004, Kahaly and Dillmann, 2005). There is a general view that most of the cardiac effects of T3 are mediated via TRα while most actions in liver and other tissues are via TRβ in multiple species including humans and rodents (Yen, 2001). The affinity of T4 for TRα1 and beta TRβ1 in fetal myocardium and other organs (Kahaly and Dillmann, 2005, Kinugawa et al., 2005, Mai et al., 2004), is some 10–15 times less than for T3 (Chopra et al., 1978). The fetal sheep heart expresses both receptor types (White et al., 2001, Macchia et al., 2001) with TRα1 being the predominant isoform which increases over gestation and more so in adulthood (Chattergoon et al., 2019). Cytoplasmic thyroid hormone receptors (rat) may also have signaling properties (Moriscot et al., 1997, Makino et al., 2009, Mai et al., 2004). Of the TH alpha isoforms, only TRα1, the predominant isoform expressed in the adult heart, is known to bind T3. However, the other isoforms, α2 and shortened cousins, Δα1 and Δα2 may have other physiological actions, mostly inhibitory. All of the beta TH isoforms, β1, β2, and β3 (rat), bind T3; Δβ3 is a potent TH repressor in vitro (Belke et al., 2007). It is clear that unliganded TH can bind DNA and suppress gene expression but regulation of such action is unknown.

The functional characteristics of the TR isoforms have been identified by phenotype analysis in mutant mice. Over a dozen mutant strains have been developed (Flamant and Samarut, 2003, Gloss et al., 2001) and show that loss of TRα1 and TRα2 led to reduced heart rate and decreased pacemaker current gene expression, while loss of TRβ1 led to increased heart rate. Mutation studies show that TRα1 is necessary during pre-weaning post-natal life for survival. Mouse thyroid hormone receptors alpha- and beta-knockout experiments demonstrate receptor mediated effects of T3 (Macchia et al., 2001). Cardiac contractile performance is reduced by direct action on the cardiomyocyte and electrical activity is suppressed via decreased ion channel activity. The sodium-calcium exchanger, the L/T type calcium channels, the ryanodine receptor and the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA2) are all targets of T3 action via the receptor system. In addition, the hormone influences the expression and contractile state of the contractile proteins in striated muscle (Sayen et al., 1992). Makino et al showed that TRβ has been shown to be required for angiogenesis during cardiac development, and that administration of physiological concentrations of T3 up-regulates RNA and protein expression of TRβ and VEGFR2 in the mouse heart (Makino et al., 2009).

TRs partner with retinoid X receptors (RXR) and perhaps other receptors to form heterodimers before binding DNA targets sites on promoters of target genes (Glass, 1994). If they are “unliganded” they adopt the aporeceptor conformation, or conversely, when the ligand binding domain is occupied by T3 they adopt holoreceptor conformation (Chassande, 2003). These two conformations are in equilibrium under physiological conditions. The unliganded receptors also bind T3 regulatory elements and appear to suppress gene action. Thus, unlike most other types of nuclear receptor systems, TR sensitive gene expression ranges from stimulation to suppression depending on the ligand binding state of the receptor (Chassande, 2003).

Wrutniak-Cabello et al. (Wrutniak-Cabello et al., 2001, Wrutniak et al., 1995) identified and described a 43-kDa protein related to c-Erb A α1 (p43) with TRE and T3 binding activities in the mitochondrial matrix. Further studies show that p43 stimulates mitochondrial transcription and protein synthesis in the presence of T3 (Casas et al., 1999). p43 overexpression stimulates mitochondrial activity and potentiates terminal differentiation in myoblasts (Rochard et al., 2000, Seyer et al., 2006). More recently it was reported that p43 overexpression in mouse skeletal muscle increased mitochondrial transcription, biogenesis, and respiration, and induced a shift in metabolic and contractile type toward a more oxidative and slow twitch fiber (Casas et al., 2008). This receptor has not been studied in cardiomyocytes.

If too much or too little T3 underlies programming changes in the myocardium, it is important to know whether these changes are through binding the thyroid hormone receptors or by a non-receptor mechanism. Recent progress in signaling biology has enlightened our understanding of non-classical receptor signaling for thyroid hormone (40). There is evidence for two primary types of non-nuclear thyroid hormone signaling. One type is via a cell membrane receptor, an integrin perhaps, and the other is via a thyroid hormone receptor in the cytoplasm (Davis et al., 2005, Davis et al., 2008). Thus far, it appears that in each of these pathways, thyroid hormones stimulate well known phosphorylation cascades within minutes. In addition, it has been reported that cellular calcium ion entry and regulation of protein kinase C are influenced by TH. As an example of the first, TH can activate the MAPK pathway when bound to the αVβ3 integrin at the cell membrane; this can induce angiogenesis and promote cell growth in monkey CV-1 fibroblasts that do not express thyroid receptors (Bergh et al., 2005). For the second type, Cao et al. reported a thyroid hormone-β receptor activated cascade, THβ-PI3K-Akt/PKB-mTOR-p70s6k, that was stimulated by T3 in human skin fibroblasts (Cao et al., 2005). This cascade leads to the induction of hypoxia-sensitive HIF1α and its target genes (Moeller et al., 2006). Whether these non-genomic pathways operate similarly in immature ovine cardiac cells is unknown. Figure 8 illustrates how T3 is known to work in cardiomyocytes and other cell types and well as a proposed mechanism for incorporating FOXO1 signaling.

CONCLUSION

While there is little disagreement that stresses experienced by fetuses can predispose them for later disease, the biological mechanisms that link stressors to outcome have not been fully explained. There are four categories of stress that are well documented as causes of fetal programming: malnutrition, chronic maternal stress, intrauterine hypoxia and toxic environmental chemicals (DuBois et al., 2015, Jonker et al., 2010, Louey et al., 2007, Giraud et al., 2006, Zohdi et al., 2014, Elias et al., 2017). However, there are other potential causes of programming including the biochemical environment that includes abnormal levels of cytokines, growth factors and hormones through which a mother can influence her offspring. There is mounting evidence that concentrations of T3 at the extremes, high or low, alter the growth patterns of cardiomyocytes and vascular elements. In addition, there may be other programming related mechanisms wrought by T3 in the immature myocardium. These have the potential for elevating risk for various forms of heart disease including ischemic heart disease and heart failure. Now that it is clear that beta-cell growth in the fetal sheep pancreas is also suppressed by elevated T3 levels (Harris et al., 2017), we can add even more evidence that dysregulation of the pituitary thyroid axis lays the foundation for programming the heart and pancreas for the life of the affected fetus.

David Barker was well aware that hormonal imbalances in pregnancy have the potential to lead to offspring disease. What he did not know and what we do not yet understand is the degree to which hormonal systems can change physiological and epigenetic regulatory systems during development that promote vulnerability for a disease that has its roots in the mother’s thyroid gland.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge the advice and editorial comments from Dr. Kent L. Thornburg.

FUNDING

Research reported in this review was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HL102763 and P01HD034430. Dr. Chattergoon was supported by NHLBI K01HL118677.

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

REFERENCE LIST

- 2017. Cardiovascular Disease: A Costly Burden For America — Projections Through 2035 https://healthmetrics.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Cardiovascular-Disease-A-Costly-Burden.pdf 2017 ed.: American Heart Association. [Google Scholar]

- ABALOVICH M, GUTIERREZ S, ALCARAZ G, MACCALLINI G, GARCIA A & LEVALLE O 2002. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Thyroid, 12, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABUID J, STINSON DA & LARSEN PR 1973. Serum triiodothyronine and thyroxine in the neonate and the acute increases in these hormones following delivery. J Clin Invest, 52, 1195–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHUJA P, SDEK P & MACLELLAN WR 2007. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev, 87, 521–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALEMU A, TEREFE B, ABEBE M & BIADGO B 2016. Thyroid hormone dysfunction during pregnancy: A review. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd), 14, 677–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANVERSA P, KAJSTURA J, LERI A & BOLLI R 2006. Life and death of cardiac stem cells: a paradigm shift in cardiac biology. Circulation, 113, 1451–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ 1995. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ, 311, 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ 1999a. Fetal origins of cardiovascular disease. Ann. Med, 31 Suppl 1, 3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ 1999b. The fetal origins of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Intern. Med, 130, 322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ, MARTYN CN, OSMOND C, HALES CN & FALL CH 1993. Growth in utero and serum cholesterol concentrations in adult life. BMJ, 307, 1524–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ & OSMOND C 1988. Low birth weight and hypertension. BMJ, 297, 134–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER DJ, OSMOND C & LAW CM 1989. The intrauterine and early postnatal origins of cardiovascular disease and chronic bronchitis. J Epidemiol. Community Health, 43, 237–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRY JS & ANTHONY RV 2008. The pregnant sheep as a model for human pregnancy. Theriogenology, 69, 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKS GP & BURROW GN 1991. Thyroid disease and pregnancy. Med. Clin. North Am, 75, 121–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELKE DD, GLOSS B, SWANSON EA & DILLMANN WH 2007. Adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms-alpha1 and -beta1 improves contractile function in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Endocrinology, 148, 2870–2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELTRAMI AP, BARLUCCHI L, TORELLA D, BAKER M, LIMANA F, CHIMENTI S, KASAHARA H, ROTA M, MUSSO E, URBANEK K, et al. 2003. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell, 114, 763–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGH JJ, LIN HY, LANSING L, MOHAMED SN, DAVIS FB, MOUSA S & DAVIS PJ 2005. Integrin alphaVbeta3 contains a cell surface receptor site for thyroid hormone that is linked to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of angiogenesis. Endocrinology, 146, 2864–2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGMANN O, BHARDWAJ RD, BERNARD S, ZDUNEK S, BARNABE-HEIDER F, WALSH S, ZUPICICH J, ALKASS K, BUCHHOLZ BA, DRUID H, et al. 2009. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science, 324, 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTRAND S, BRUNET FG, ESCRIVA H, PARMENTIER G, LAUDET V & ROBINSON-RECHAVI M 2004. Evolutionary genomics of nuclear receptors: from twenty-five ancestral genes to derived endocrine systems. Mol. Biol. Evol, 21, 1923–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIANCO AC & KIM BW 2006. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin. Invest, 116, 2571–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIANCO AC, SALVATORE D, GEREBEN B, BERRY MJ & LARSEN PR 2002. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr. Rev, 23, 38–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BICKNELL KA, COXON CH & BROOKS G 2007. Can the cardiomyocyte cell cycle be reprogrammed? J Mol. Cell Cardiol, 42, 706–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREALL JA, RUDOLPH AM & HEYMANN MA 1984. Role of thyroid hormone in postnatal circulatory and metabolic adjustments. J Clin. Invest, 73, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENT GA 2012. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest, 122, 3035–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN DD & CAI L 2007. Amphibian metamorphosis. Dev. Biol, 306, 20–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURRELL JH, BOYN AM, KUMARASAMY V, HSIEH A, HEAD SI & LUMBERS ER 2003. Growth and maturation of cardiac myocytes in fetal sheep in the second half of gestation. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol, 274, 952–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALVO RM, JAUNIAUX E, GULBIS B, ASUNCION M, GERVY C, CONTEMPRE B & MORREALE DE 2002. Fetal tissues are exposed to biologically relevant free thyroxine concentrations during early phases of development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 87, 1768–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAO X, KAMBE F, MOELLER LC, REFETOFF S & SEO H 2005. Thyroid hormone induces rapid activation of Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin-p70S6K cascade through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human fibroblasts. Mol. Endocrinol, 19, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASAS F, PESSEMESSE L, GRANDEMANGE S, SEYER P, GUEGUEN N, BARIS O, LEPOURRY L, CABELLO G & WRUTNIAK-CABELLO C 2008. Overexpression of the mitochondrial T3 receptor p43 induces a shift in skeletal muscle fiber types. PLoS One, 3, e2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASAS F, ROCHARD P, RODIER A, CASSAR-MALEK I, MARCHAL-VICTORION S, WIESNER RJ, CABELLO G & WRUTNIAK C 1999. A variant form of the nuclear triiodothyronine receptor c-ErbAalpha1 plays a direct role in regulation of mitochondrial RNA synthesis. Mol Cell Biol, 19, 7913–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASEY BM 2014. The debate on thyroid screening during pregnancy continues. Obstet Gynecol, 124, 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASEY BM, DASHE JS, SPONG CY, MCINTIRE DD, LEVENO KJ & CUNNINGHAM GF 2007. Perinatal significance of isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia identified in the first half of pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol, 109, 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASEY BM, DASHE JS, WELLS CE, MCINTIRE DD, LEVENO KJ & CUNNINGHAM FG 2006. Subclinical hyperthyroidism and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol, 107, 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASEY BM & LEVENO KJ 2006. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol, 108, 1283–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN L, MILLER TF, YUXIN J, FARINA C, CHANDER A, SHAFFER TH & WOLFSON MR 1998. Antenatal triiodothyronine improves neonatal pulmonary function in preterm lambs. J Soc. Gynecol. Investig, 5, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG L & KARIN M 2001. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature, 410, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANOINE JP, VERONIKIS I, ALEX S, STONE S, FANG SL, LEONARD JL & BRAVERMAN LE 1993. The postnatal serum 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) surge in the rat is largely independent of extrathyroidal 5’-deiodination of thyroxine to T3. Endocrinology, 133, 2604–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHASSANDE O 2003. Do unliganded thyroid hormone receptors have physiological functions? J Mol. Endocrinol, 31, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERGOON NN, GIRAUD GD, LOUEY S, STORK P, FOWDEN AL & THORNBURG KL 2012a. Thyroid hormone drives fetal cardiomyocyte maturation. FASEB J, 26, 397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERGOON NN, GIRAUD GD & THORNBURG KL 2007. Thyroid hormone inhibits proliferation of fetal cardiac myocytes in vitro. J Endocrinol, 192, R1–R8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERGOON NN, LOUEY S, SCANLAN T, LINDGREN I, GIRAUD GD & THORNBURG KL 2019. Thyroid hormone receptor function in maturing ovine cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERGOON NN, LOUEY S, STORK P, GIRAUD GD & THORNBURG KL 2012b. Mid-gestation ovine cardiomyocytes are vulnerable to mitotic suppression by thyroid hormone. Reprod. Sci, 19, 642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERGOON NN, LOUEY S, STORK PJ, GIRAUD GD & THORNBURG KL 2014. Unexpected maturation of PI3K and MAPK-ERK signaling in fetal ovine cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 307, H1216–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOPRA IJ, CARLSON HE & SOLOMON DH 1978. Comparison of inhibitory effects of 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), 3,3,’,5’-triiodothyronine (rT3), and 3,3’-diiodothyronine (T2) on thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced release of thyrotropin in the rat in vitro. Endocrinology, 103, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLUBB FJ JR. & BISHOP SP 1984. Formation of binucleated myocardial cells in the neonatal rat. An index for growth hypertrophy. Lab Invest, 50, 571–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLUZEAUT F & MAURER-SCHULTZE B 1986. Proliferation of cardiomyocytes and interstitial cells in the cardiac muscle of the mouse during pre- and postnatal development. Cell Tissue Kinet, 19, 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORSTIUS HB, ZIMANYI MA, MAKA N, HERATH T, THOMAS W, VAN DER LA, WREFORD NG & BLACK MJ 2005. Effect of intrauterine growth restriction on the number of cardiomyocytes in rat hearts. Pediatr. Res, 57, 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISPI F, BIJNENS B, FIGUERAS F, BARTRONS J, EIXARCH E, LE NOBLE F, AHMED A & GRATACOS E 2010. Fetal growth restriction results in remodeled and less efficient hearts in children. Circulation, 121, 2427–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS PJ, DAVIS FB & CODY V 2005. Membrane receptors mediating thyroid hormone action. Trends Endocrinol. Metab, 16, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS PJ, LEONARD JL & DAVIS FB 2008. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol, 29, 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINIZ GP, CARNEIRO-RAMOS MS & BARRETO-CHAVES ML 2009. Angiotensin type 1 receptor mediates thyroid hormone-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through the Akt/GSK-3beta/mTOR signaling pathway. Basic Res Cardiol, 104, 653–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOIS B, LOUEY S, GIRAUD GD, CHERALA G & JONKER SS 2015. Theophylline Pharmacokinetics in Foetal Sheep: Maternal Metabolic Capacity is the Principal Driver. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol, 117, 226–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELIAS AA, MAKI Y, MATUSHEWSKI B, NYGARD K, REGNAULT TRH & RICHARDSON BS 2017. Maternal nutrient restriction in guinea pigs leads to fetal growth restriction with evidence for chronic hypoxia. Pediatr Res, 82, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALL CH, OSMOND C, BARKER DJ, CLARK PM, HALES CN, STIRLING Y & MEADE TW 1995. Fetal and infant growth and cardiovascular risk factors in women. BMJ, 310, 428–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER DA 1977. Thyroid function in the premature infant. Am J Dis Child, 131, 842–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER DA 2008. Thyroid system immaturities in very low birth weight premature infants. Semin Perinatol, 32, 387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER DA, DUSSAULT JH, HOBEL CJ & LAM R 1973. Serum and thyroid gland triiodothyronine in the human fetus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 36, 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHER DA & POLK DH 1989. Development of the thyroid. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 3, 627–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLAMANT F & SAMARUT J 2003. Thyroid hormone receptors: lessons from knockout and knock-in mutant mice. Trends Endocrinol. Metab, 14, 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORHEAD AJ, CURTIS K, KAPTEIN E, VISSER TJ & FOWDEN AL 2006. Developmental control of iodothyronine deiodinases by cortisol in the ovine fetus and placenta near term. Endocrinology, 147, 5988–5994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORHEAD AJ, JELLYMAN JK, GARDNER DS, GIUSSANI DA, KAPTEIN E, VISSER TJ & FOWDEN AL 2007. Differential effects of maternal dexamethasone treatment on circulating thyroid hormone concentrations and tissue deiodinase activity in the pregnant ewe and fetus. Endocrinology, 148, 800–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORHEAD AJ, LI J, GILMOUR RS & FOWDEN AL 1998. Control of hepatic insulin-like growth factor II gene expression by thyroid hormones in fetal sheep near term. Am. J Physiol, 275, E149–E156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORHEAD AJ, LI J, SAUNDERS JC, DAUNCEY MJ, GILMOUR RS & FOWDEN AL 2000. Control of ovine hepatic growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor I by thyroid hormones in utero. Am. J Physiol Endocrinol. Metab, 278, E1166–E1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRASER M & LIGGINS GC 1988. Thyroid hormone kinetics during late pregnancy in the ovine fetus. J Dev Physiol, 10, 461–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHARIB H, TUTTLE RM, BASKIN HJ, FISH LH, SINGER PA & MCDERMOTT MT 2005. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction: a joint statement on management from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, and the Endocrine Society. J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 90, 581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIRAUD GD, LOUEY S, JONKER S, SCHULTZ J & THORNBURG KL 2006. Cortisol stimulates cell cycle activity in the cardiomyocyte of the sheep fetus. Endocrinology, 147, 3643–3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASS CK 1994. Differential recognition of target genes by nuclear receptor monomers, dimers, and heterodimers. Endocr. Rev, 15, 391–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLOSS B, TROST S, BLUHM W, SWANSON E, CLARK R, WINKFEIN R, JANZEN K, GILES W, CHASSANDE O, SAMARUT J et al. 2001. Cardiac ion channel expression and contractile function in mice with deletion of thyroid hormone receptor alpha or beta. Endocrinology, 142, 544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLUCKMAN PD, HANSON MA, COOPER C & THORNBURG KL 2008. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med, 359, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAVES LM, GUY HI, KOZLOWSKI P, HUANG M, LAZAROWSKI E, POPE RM, COLLINS MA, DAHLSTRAND EN, EARP HS III & EVANS DR 2000. Regulation of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase by MAP kinase. Nature, 403, 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HADDOW JE, PALOMAKI GE, ALLAN WC, WILLIAMS JR, KNIGHT GJ, GAGNON J, O’HEIR CE, MITCHELL ML, HERMOS RJ, WAISBREN SE, et al. 1999. Maternal thyroid deficiency during pregnancy and subsequent neuropsychological development of the child. N Engl J Med, 341, 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS SE, DE BLASIO MJ, DAVIS MA, KELLY AC, DAVENPORT HM, WOODING FBP, BLACHE D, MEREDITH D, ANDERSON M, FOWDEN AL, et al. 2017. Hypothyroidism in utero stimulates pancreatic beta cell proliferation and hyperinsulinaemia in the ovine fetus during late gestation. J Physiol, 595, 3331–3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOPKINS PS & THORBURN GD 1972. The effects of foetal thyroidectomy on the development of the ovine foetus. J Endocrinol, 54, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU LW, BENVENUTI LA, LIBERTI EA, CARNEIRO-RAMOS MS & BARRETO-CHAVES ML 2003. Thyroxine-induced cardiac hypertrophy: influence of adrenergic nervous system versus renin-angiotensin system on myocyte remodeling. Am. J Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol, 285, R1473–R1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG H & TINDALL DJ 2007. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci, 120, 2479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRRCHER I, WALKINSHAW DR, SHEEHAN TE & HOOD DA 2008. Thyroid hormone (T3) rapidly activates p38 and AMPK in skeletal muscle in vivo. J Appl. Physiol, 104, 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONKER SS, FABER JJ, ANDERSON DF, THORNBURG KL, LOUEY S & GIRAUD GD 2007a. Sequential growth of fetal sheep cardiac myocytes in response to simultaneous arterial and venous hypertension. Am. J. Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol, 292, R913–R919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONKER SS, GIRAUD MK, GIRAUD GD, CHATTERGOON NN, LOUEY S, DAVIS LE, FABER JJ & THORNBURG KL 2010. Cardiomyocyte enlargement, proliferation and maturation during chronic fetal anaemia in sheep. Exp. Physiol, 95, 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONKER SS & LOUEY S 2016. Endocrine and other physiologic modulators of perinatal cardiomyocyte endowment. J Endocrinol, 228, R1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONKER SS, LOUEY S, GIRAUD GD, THORNBURG KL & FABER JJ 2015. Timing of cardiomyocyte growth, maturation, and attrition in perinatal sheep. FASEB J, 29, 4346–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONKER SS, ZHANG L, LOUEY S, GIRAUD GD, THORNBURG KL & FABER JJ 2007b. Myocyte enlargement, differentiation, and proliferation kinetics in the fetal sheep heart. J Appl. Physiol, 102, 1130–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHALY GJ & DILLMANN WH 2005. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr. Rev, 26, 704–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAJANTIE E, PHILLIPS DI, OSMOND C, BARKER DJ, FORSEN T & ERIKSSON JG 2006. Spontaneous hypothyroidism in adult women is predicted by small body size at birth and during childhood. J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 91, 4953–4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEHAT I & MOLKENTIN JD 2010. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1188, 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINUGAWA K, JEONG MY, BRISTOW MR & LONG CS 2005. Thyroid hormone induces cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in a thyroid hormone receptor alpha1-specific manner that requires TAK1 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Endocrinol, 19, 1618–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUZMAN JA, GERDES AM, KOBAYASHI S & LIANG Q 2005a. Thyroid hormone activates Akt and prevents serum starvation-induced cell death in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol. Cell Cardiol, 39, 841–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUZMAN JA, VOGELSANG KA, THOMAS TA & GERDES AM 2005b. L-Thyroxine activates Akt signaling in the heart. J Mol. Cell Cardiol, 39, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI F, WANG X, CAPASSO JM & GERDES AM 1996. Rapid transition of cardiac myocytes from hyperplasia to hypertrophy during postnatal development. J Mol. Cell Cardiol, 28, 1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI G, XIAO Y, ESTRELLA JL, DUCSAY CA, GILBERT RD & ZHANG L 2003. Effect of fetal hypoxia on heart susceptibility to ischemia and reperfusion injury in the adult rat. J Soc. Gynecol. Investig, 10, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORIJN RH, NELSON JC & LONGO LD 1980. Induced fetal hyperthyroidism: cardiac output and oxygen consumption. Am. J. Physiol, 239, H302–H307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOUEY S, JONKER SS, GIRAUD GD & THORNBURG KL 2007. Placental insufficiency decreases cell cycle activity and terminal maturation in fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. J Physiol, 580, 639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACCHIA PE, TAKEUCHI Y, KAWAI T, CUA K, GAUTHIER K, CHASSANDE O, SEO H, HAYASHI Y, SAMARUT J, MURATA Y, et al. 2001. Increased sensitivity to thyroid hormone in mice with complete deficiency of thyroid hormone receptor alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 98, 349–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAI W, JANIER MF, ALLIOLI N, QUIGNODON L, CHUZEL T, FLAMANT F & SAMARUT J 2004. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha is a molecular switch of cardiac function between fetal and postnatal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101, 10332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAIESE K, CHONG ZZ, SHANG YC & HOU J 2009. FoxO proteins: cunning concepts and considerations for the cardiovascular system. Clin Sci (Lond), 116, 191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKINO A, SUAREZ J, WANG H, BELKE DD, SCOTT BT & DILLMANN WH 2009. Thyroid hormone receptor-beta is associated with coronary angiogenesis during pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Endocrinology, 150, 2008–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTYN CN, MEADE TW, STIRLING Y & BARKER DJ 1995. Plasma concentrations of fibrinogen and factor VII in adult life and their relation to intra-uterine growth. Br. J. Haematol, 89, 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARX H, AMIN P & LAZARUS JH 2008. Hyperthyroidism and pregnancy. BMJ, 336, 663–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUI T, NAGOSHI T & ROSENZWEIG A 2003. Akt and PI 3-kinase signaling in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and survival. Cell Cycle, 2, 220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAURIN KA & MACTUTUS CF 2015. Polytocus focus: Uterine position effect is dependent upon horn size. Int J Dev Neurosci, 40, 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOELLER LC, CAO X, DUMITRESCU AM, SEO H & REFETOFF S 2006. Thyroid hormone mediated changes in gene expression can be initiated by cytosolic action of the thyroid hormone receptor beta through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Nucl. Recept. Signal, 4, e020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORISCOT AS, SAYEN MR, HARTONG R, WU P & DILLMANN WH 1997. Transcription of the rat sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase gene is increased by 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine receptor isoform-specific interactions with the myocyte-specific enhancer factor-2a. Endocrinology, 138, 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRISON JL, BOTTING KJ, DYER JL, WILLIAMS SJ, THORNBURG KL & MCMILLEN IC 2007. Restriction of placental function alters heart development in the sheep fetus. Am. J. Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol, 293, R306–R313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MU J, SLEVIN JC, QU D, MCCORMICK S & ADAMSON SL 2008. In vivo quantification of embryonic and placental growth during gestation in mice using micro-ultrasound. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 6, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA N, RAMASWAMY S, VAZQUEZ F, SIGNORETTI S, LODA M & SELLERS WR 2000. Forkhead transcription factors are critical effectors of cell death and cell cycle arrest downstream of PTEN. Mol Cell Biol, 20, 8969–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSON AK, PROTHEROE KN, SCHOLZ TD & SEGAR JL 2008. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases and Akt in response to pulmonary artery banding in the fetal sheep heart is developmentally regulated. Neonatology, 93, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPPENHEIMER JH & DILLMANN WH 1978. Molecular mechanisms at the tissue level in hyperthyroidism. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 7, 145–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEREZ-CASTILLO A, BERNAL J, FERREIRO B & PANS T 1985. The early ontogenesis of thyroid hormone receptor in the rat fetus. Endocrinology, 117, 2457–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIPS DI, BARKER DJ & OSMOND C 1993. Infant feeding, fetal growth and adult thyroid function. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh), 129, 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLK DH 1995. Thyroid hormone metabolism during development. Reprod. Fertil. Dev, 7, 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLK DH, IKEGAMI M, JOBE AH, NEWNHAM J, SLY P, KOHEN R & KELLY R 1995. Postnatal lung function in preterm lambs: effects of a single exposure to betamethasone and thyroid hormones. Am. J Obstet. Gynecol, 172, 872–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLK DH, WU SY, WRIGHT C, REVICZKY AL & FISHER DA 1988. Ontogeny of thyroid hormone effect on tissue 5’-monodeiodinase activity in fetal sheep. Am. J Physiol, 254, E337–E341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTHANVEETIL P, WAN A & RODRIGUES B 2013. FoxO1 is crucial for sustaining cardiomyocyte metabolism and cell survival. Cardiovasc Res, 97, 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTHANVEETIL P, WANG Y, WANG F, KIM MS, ABRAHANI A & RODRIGUES B 2010. The increase in cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 after short-term dexamethasone is controlled by an Akt-p38-forkhead box other factor-1 signaling axis. Endocrinology, 151, 2306–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTHANVEETIL P, WANG Y, ZHANG D, WANG F, KIM MS, INNIS S, PULINILKUNNIL T, ABRAHANI A & RODRIGUES B 2011. Cardiac triglyceride accumulation following acute lipid excess occurs through activation of a FoxO1-iNOS-CD36 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med, 51, 352–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADETTI G, RENZULLO L, GOTTARDI E, D’ADDATO G & MESSNER H 2004. Altered thyroid and adrenal function in children born at term and preterm, small for gestational age. J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 89, 6320–6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAKUSAN K 1984. Cardiac growth, maturation, and aging In: ZAK R (ed.) Growth of the heart in health and disease. 1 ed. New York: Raven Press. [Google Scholar]

- RENNIE MY, RAHMAN A, WHITELEY KJ, SLED JG & ADAMSON SL 2015. Site-specific increases in utero- and fetoplacental arterial vascular resistance in eNOS-deficient mice due to impaired arterial enlargement. Biol Reprod, 92, 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICH-EDWARDS JW, KLEINMAN K, MICHELS KB, STAMPFER MJ, MANSON JE, REXRODE KM, HIBERT EN & WILLETT WC 2005. Longitudinal study of birth weight and adult body mass index in predicting risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. BMJ, 330, 1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCHARD P, RODIER A, CASAS F, CASSAR-MALEK I, MARCHAL-VICTORION S, DAURY L, WRUTNIAK C & CABELLO G 2000. Mitochondrial activity is involved in the regulation of myoblast differentiation through myogenin expression and activity of myogenic factors. J Biol Chem, 275, 2733–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RONNEBAUM SM & PATTERSON C 2010. The FoxO family in cardiac function and dysfunction. Annu. Rev. Physiol, 72, 81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALIH DA & BRUNET A 2008. FoxO transcription factors in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis during aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 20, 126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAYEN MR, ROHRER DK & DILLMANN WH 1992. Thyroid hormone response of slow and fast sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase mRNA in striated muscle. Mol. Cell Endocrinol, 87, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMID G & PFITZER P 1985. Mitoses and binucleated cells in perinatal human hearts. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol, 48, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUELER PA, SCHWARTZ HL, STRAIT KA, MARIASH CN & OPPENHEIMER JH 1990. Binding of 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) and its analogs to the in vitro translational products of c-erbA protooncogenes: differences in the affinity of the alpha- and beta-forms for the acetic acid analog and failure of the human testis and kidney alpha-2 products to bind T3. Mol. Endocrinol, 4, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEGAR JL, VOLK KA, LIPMAN MH & SCHOLZ TD 2013. Thyroid hormone is required for growth adaptation to pressure load in the ovine fetal heart. Exp Physiol, 98, 722–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEOANE J, LE HV, SHEN L, ANDERSON SA & MASSAGUE J 2004. Integration of Smad and forkhead pathways in the control of neuroepithelial and glioblastoma cell proliferation. Cell, 117, 211–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEYER P, GRANDEMANGE S, BUSSON M, CARAZO A, GAMALERI F, PESSEMESSE L, CASAS F, CABELLO G & WRUTNIAK-CABELLO C 2006. Mitochondrial activity regulates myoblast differentiation by control of c-Myc expression. J Cell Physiol, 207, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGH BK, SINHA RA, ZHOU J, XIE SY, YOU SH, GAUTHIER K & YEN PM 2013. FoxO1 deacetylation regulates thyroid hormone-induced transcription of key hepatic gluconeogenic genes. J Biol Chem, 288, 30365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOONPAA MH, KIM KK, PAJAK L, FRANKLIN M & FIELD LJ 1996. Cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and binucleation during murine development. Am. J Physiol, 271, H2183–H2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUNDGREN NC, GIRAUD GD, SCHULTZ JM, LASAREV MR, STORK PJ & THORNBURG KL 2003a. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositol-3 kinase mediate IGF-1 induced proliferation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol, 285, R1481–R1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUNDGREN NC, GIRAUD GD, STORK PJ, MAYLIE JG & THORNBURG KL 2003b. Angiotensin II stimulates hyperplasia but not hypertrophy in immature ovine cardiomyocytes. J Physiol, 548, 881–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORBURN GD & HOPKINS PS 1973. Thyroid function in the foetal lamb In: COMLINE KS, CROSS KW, DAWES GS & NATHANIELSZ PW (eds.) Foetal and Neonatal Physiology: Proceedings of the Sir Joseph Barcroft Centenary Symposium held at The Physiological Laboratory Cambridge. Texas: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- THORNBURG K, JONKER S, O’TIERNEY P, CHATTERGOON N, LOUEY S, FABER J & GIRAUD G 2010. Regulation of the cardiomyocyte population in the developing heart. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol, 106, 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBURG KL 2015. The programming of cardiovascular disease. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 6, 366–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TZIVION G, DOBSON M & RAMAKRISHNAN G 2011. FoxO transcription factors; Regulation by AKT and 14–3-3 proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1813, 1938–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER SPEK AH, FLIERS E & BOELEN A 2017. The classic pathways of thyroid hormone metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 458, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN TUYL M, BLOMMAART PE, DE BOER PA, WERT SE, RUIJTER JM, ISLAM S, SCHNITZER J, ELLISON AR, TIBBOEL D, MOORMAN AF et al. H. 2004. Prenatal exposure to thyroid hormone is necessary for normal postnatal development of murine heart and lungs. Dev. Biol, 272, 104–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDER HEIDEN MG, CANTLEY LC & THOMPSON CB 2009. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science, 324, 1029–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG W, TENG W, SHAN Z, WANG S, LI J, ZHU L, ZHOU J, MAO J, YU X, LI J, et al. 2011. The prevalence of thyroid disorders during early pregnancy in China: the benefits of universal screening in the first trimester of pregnancy. Eur J Endocrinol, 164, 263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARD PS & THOMPSON CB 2012. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell, 21, 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE P, BURTON KA, FOWDEN AL & DAUNCEY MJ 2001. Developmental expression analysis of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms reveals new insights into their essential functions in cardiac and skeletal muscles. FASEB J, 15, 1367–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILCOXON JS & REDEI EE 2004. Prenatal programming of adult thyroid function by alcohol and thyroid hormones. Am. J Physiol Endocrinol. Metab, 287, E318–E326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILKINSON MG & MILLAR JB 2000. Control of the eukaryotic cell cycle by MAP kinase signaling pathways. FASEB J, 14, 2147–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS FL, SIMPSON J, DELAHUNTY C, OGSTON SA, BONGERS-SCHOKKING JJ, MURPHY N, VAN TOOR H, WU SY, VISSER TJ & HUME R 2004. Developmental trends in cord and postpartum serum thyroid hormones in preterm infants. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 89, 5314–5320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRUTNIAK-CABELLO C, CASAS F & CABELLO G 2001. Thyroid hormone action in mitochondria. J Mol Endocrinol, 26, 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]