Abstract

Metabotropic receptors are responsible for so-called slow synaptic transmission and mediate the effects of 100’s of peptide and non-peptide neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. Over the past decade or so a revolution in membrane protein structural determination has clarified the molecular determinants responsible for the actions of these receptors. Here I focus on the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) which are targets for neuropsychiatric drugs and show how insights into the structure and function of these important synaptic proteins are accelerating our understanding of their actions. Importantly, illuminating GPCR structure and function should enhance the structure-guided discovery of novel chemical tools to manipulate and understand these synaptic proteins.

MAIN

Neurotransmitter receptors are essential for mediating the effects of neurotransmitters in the brain and peripheral nervous system. There are generally considered to be two types of neurotransmitter receptors: ionotropic and metabotropic. While ionotropic receptors are typically ligand-gated ion channels, through which ions pass in response to a neurotransmitter, metabotropic receptors require G proteins and second messengers to indirectly modulate ionic activity in neurons. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest family of metabotropic receptors, although receptor-tyrosine kinases 1 and guanylate cyclase receptors 2,3 can also be considered to be metabotropic receptors 4. GPCRs also constitute the largest family of druggable targets 5,6 in the human genome, and 34% of FDA-approved medications have GPCRs as their main therapeutic target 7,8— especially those used for neuropsychiatric disorders 6,9,10(Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors as targets for neuropsychiatric disorders and drugs of abuse

| Target class |

Neurotransmitter | Receptor | Representative medication |

Therapeutic indications or abuse |

Pharmacological action |

Structure determined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCR | Dopamine | D2-dopamine | Ropinirole | Parkinson’s Disease | Agonist | 75 |

| GPCR | Dopamine | D2-dopamine | Nemonapride | Schizophrenia | Antagonist/inverse agonist | 75 |

| GPCR | Serotonin | 5-HT2C serotonin | Lorcaserin | Obesity | Agonist | 33 |

| GPCR | Serotonin | 5-HT1A serotonin | Buspirone | Anxiety and depression | Partial agonist | None reported |

| GPCR | Serotonin | 5-HT1B | Ergotamine | Migraine headaches | Antagonist | 31,32 |

| GPCR | Adenosine | A2A-adenosine | Caffeine | Alertness | Antagonist | 128 |

| GPCR | Norepinephrine | β1 and β2-adrenergic | Propranolol | Post-traumatic stress disorder; anxiety disorders | Inverse agonist | 129,130 |

| GPCR | Serotonin | 5-HT2A serotonin | Pimavanserin | Psychosis related to Parkinson’s Disease | Inverse agonist | 131 |

| GPCR | Serotonin | Many 5-HT receptors | LSD | Hallucinogen use and abuse | Agonist | 70 |

| GPCR | Endocannabinoids | CB1 cannabinoid | Tetrahydrocannibinol | Anorexia related to cancer chemotherapy; cannabis abuse | Agonist | 132 |

| GPCR | γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) | GABA-B | Baclofen | Spasticity-related movement disorders | Agonist | None reported |

| GPCR | Histamine | H1-histamine | Diphenhydramine | Sedative | Antagonist | 41 |

| GPCR | Endorphins; endomorphans | μ opioid | Morphine | Pain; abused opioid | Agonist | 59,133 |

| GPCR | Dynorphin | κ opioid | Nalfurafine | Itch | Agonist | 52,134 |

| GPCR | Dynorphin | κ opioid | Salvinorin A | Hallucinogen use and abuse | Agonist | 52,134 |

| GPCR | Orexin | OX1-orexin | Suvorexant | Insomnia | Antagonist | 135 |

| GPCR | Norepinephrine | α2-adrenergic | Clonidine | Anxiety; opioid withdrawal | Agonist | None reported |

| GPCR | S1P1 sphingosine antagonist | Fingolimod | Multiple sclerosis | Down-regulates receptor | 136 | |

| Recept or tyrosine kinase | Nerve growth factors | TRK | Entrectinib | Cancers including astrocytoma | Antagonist | No full length structure reported |

| Guanylate cyclases | Atrial natriuretic peptide | NPRA-atrial natriuretic receptor | Atrial natriuretic peptide | None (heart failure) | Agonist | 137 |

There are many distinct chemical classes of neurotransmitters including: (1) small molecules (e.g. glutamate, norepinephrine, serotonin); (2) neuropeptides (e.g. enkephalins, endorphins, neurokinins); and (3) others, including metabolites (e.g. endocannabinoids, ATP, ADP, adenosine) and gases (e.g. nitric oxide). Although the precise number of brain neurotransmitters is not known with certainty, it is likely that 100’s of distinct neurotransmitters exist, including many orphan neuropeptides 11. Each neurotransmitter system has distinct cellular and region-specific distribution patterns in the brain; these can be visualized at the mRNA level using the Allen Brain Atlas 12 or with genetically-encoded markers using the GENSAT resource 13 Virtually all neurotransmitters transduce their signals at least in part by activating GPCRs, and the regional and cellular distributions of brain GPCR mRNAs are well described 12,14. As is the case with neurotransmitters, each neurotransmitter metabotropic receptor has a distinct regional and cellular distribution in the brain 12,14 and elsewhere 14.

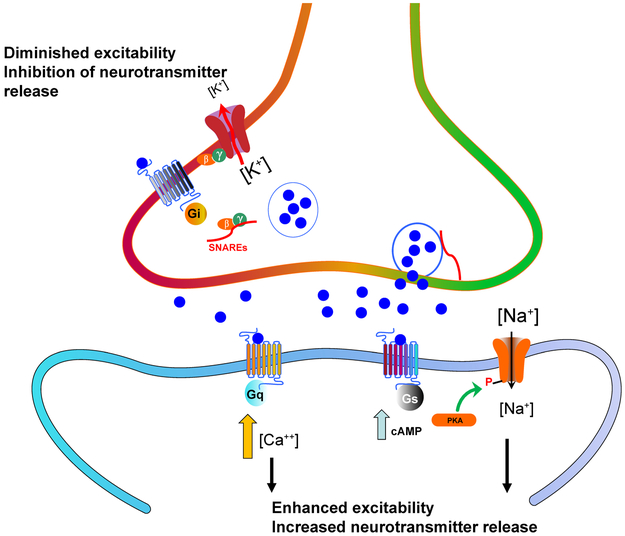

GPCRs modulate synaptic transmission via so-called ‘slow synaptic transmission’ 15 which occurs in the seconds-minutes time frame in the central nervous system. Metabotropic receptors like GPCRs may be found pre- and post-synaptically. Presynaptic Gi-coupled GPCRs, such as the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B serotonin receptors 16,17, inhibit neurotransmitter release via Gβ/γ-mediated activation of inhibitory channels like G-protein inwardly rectifying potassium channels 18 and by inhibition of vesicle docking SNARE-like proteins 19,20 (Fig.1). Post-synaptically GPCRs can enhance neuronal excitability via Gs- and Gq-coupled GPCRs which have complex actions mediated by second messengers and protein kinases 21,22 (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1. Metabotropic receptors such as GPCRs modulate synaptic transmission.

Shown is a cartoon depicting several of the mechanisms by which metabotropic receptors like GPCRs can modify synaptic transmission. As is depicted, Gi-coupled GPCRs can attenuate presynaptic release via activating various channels including inhibitory G-protein inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRKS) 18,138 and by inhibiting vesicle release machinery including SNARE proteins 19. Postsynaptic Gq and Gs-coupled GPCRs can induce or potentiate neuronal firing via a number of intracellular second messengers 139 and secondary modulation of ion channel activity 21.

Here I will discuss how structural insights into neurotransmitter GPCRs transforms our understanding of them, focusing on example GPCRs that are targets of approved drugs used in neuropsychiatric disorders. The past decade has witnessed remarkable progress in elucidating the structure and function of GPCR family, with perhaps 60 or so GPCRs having their structures determined by x-ray crystallography 7 or cryo-EM7. Additionally, various intermediate signaling states ranging from inactive to active have been elucidated for exemplar GPCRs 6. Finally, progress has been made on utilizing this structural information for structure-guided and structure-inspired neuropsychiatric drug discovery 8. Here I will provide an overview of our understanding of how structure informs the function of representative neurotransmitter GPCRs. I will also show how an understanding of structure illuminates neuropharmacology and I will highlight therapeutic challenges and opportunities for neurotransmitter-targeted GPCRs.

TOWARDS A STRUCTURAL GENOMICS OF NEUROTRANSMITTER TARGETED GPCRs

Structural genomics has been defined as the approach which proposes “determining protein structures on a genome-wide scale” 23—which boils down to ultimately determining the three-dimensional structure of every protein in the human genome. Obtaining GPCR structures has been historically challenging. Thus, although low-resolution structures of rhodopsin were available as early as 199324 and useful models of helical arrangements were generated using this information25, the first bona fide high resolution GPCR structure was not achieved until 2000 with rhodopsin 26. The first non-opsin GPCR structures were obtained in 2007 27,28,29 and since then structures, mainly via x-ray crystallography, have been obtained for around 60 distinct human GPCRs (Fig 2a and ref 7). To obtain useful structures, GPCR crystallography typically requires high affinity ligands which serve to stabilize the receptor in a distinct state suitable for crystallography. Such compounds not only need to be high affinity (e.g. low nM to pM) but also to have slow dissociation rates30. Ideally, then to obtain complete structural coverage of all GPCRs in the human genome, one would need high affinity, slowly dissociating ligands for each of them. Such ligands do not necessarily need to be specific as, for instance, the non-selective drug ergotamine has been used to obtain three different serotonin receptor subtype structures: 5-HT1B 31, 5-HT2B 32 and 5-HT2C 33. Once structures are obtained—even with non-selective ligands—the structural features for distinct pharmacological properties can be elucidated (see for instance 32,33). Furthermore, obtaining structures of related GPCRs frequently facilitates the structure-guided discovery and design of subtype-selective drugs34.

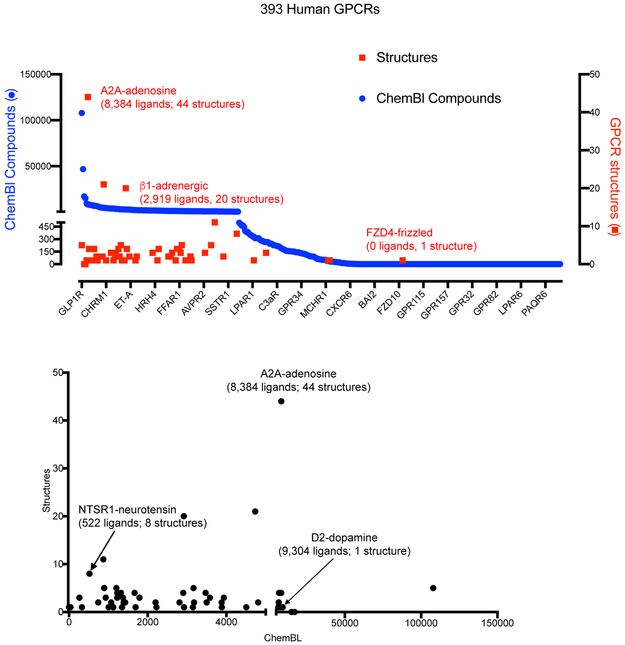

FIGURE 2. The availability of chemical matter is useful for obtaining GPCR structures.

(a) shows a graph with the number of compounds annotated in Chembl against a particular human GPCR (blue dots) versus the number of X-ray or Cryo-EM structures (red squares) deposited for each particular GPCR (effective date Feb 1, 2019). (b) shows that there is no direct linear relationship comparing the number of compounds annotated and the number of structures currently available.

An analysis of available GPCR structures and cognate ligands, utilizing open-source databases of small molecules binding known protein targets along with databases of GPCR structural information can be the first step towards determining the feasibility of a comprehensive structural elucidation of the GPCR-ome.,. Chembl 35, the KiDatabase 36 or PubChem 37 are databases matching compounds and their targets. . Fig 2A shows the number of ligands with Chembl -annotated activity against a total of 393 non-olfactory GPCRs and, simultaneously, the number of structures available for each of these receptors (as of February 2019). Similar to our previous analyses 38,39,6,8 and those of others 7, around half of all human non-olfactory GPCRs are well-annotated with respect to chemical matter, while the rest have few to no compounds associated with them in openly available databases 35. With one exception—the Frizzled 4 (FZD4) receptor—for which the structure of the seven transmembrane domain (7-TM) in the ligand-free state was recently solved 40—those GPCRs for which there are reported structures typically have 100’s to 1000’s of annotated ligands (Fig 2a). No clear relationship exists between the number of annotated ligands in Chembl and the number of distinct structures (Fig 2b), though as mentioned above, high affinity, slowly dissociating ligands are typically key for obtaining structures. Thus, to comprehensively illuminate the structural genomics of GPCRs, suitable ligands will likely need to be obtained for a large number. Efforts are now ongoing to obtain these ligands including the ‘Illuminating the druggable genome’ initiative (https://commonfund.nih.gov/idg), which has those GPCRs for which there is little chemical matter a top priority.

Taking into account this wealth of data, and with new GPCR structures now appearing every week or so, what are the opportunities and challenges for completing a structural genomics survey for neurotransmitter GPCRs? Even with respect to the 240 Class A (Rhodopsin- like) GPCRs—comprising most neurotransmitter receptors and for which there is the most structural coverage — fewer than 50 distinct members have structures elucidated. Several classes—B2 (Adhesion), C (Glutamate), F (Frizzled) and T(Tastant 2), for instance—have two (Glutamate and Frizzled) to zero (Adhesion and Tastant) structures reported.

Even among the thoroughly structurally annotated families of neurotransmitter receptors—for instance the biogenic amine receptor family— structural annotation is still quite sparse. Thus, only one 41 (the H1-histamine) of 4 histamine receptors has a reported structure, and there are no publicly available structures for α1 or α2 adrenergic receptors. Finally, only 3 (5-HT1B, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C) 31,32,33 of 1417 serotonin receptors have published structures. Thus, considerable opportunities exist for obtaining structures of representative members of each neurotransmitter GPCR subfamily. Additionally, even for those neurotransmitter families such as the muscarinic receptor family, which has acetylcholine as its neurotransmitter, and at which 4 (M1, M2, M3 and M4) 42,43,44 of 5 members have structures reported, the structural determinants for subtype selectivity are still to be elucidated and fully exploited for the creation of selective muscarinic agonists and antagonists 45. For muscarinic receptors, in particular, it is clear that drugs targeting M1 and M4-muscarinic receptors may have special utility for enhancing cognition in Alzheimer’s Disease and Schizophrenia, while interactions with M3-muscarinic are associated with debilitating side-effects 46,47. In terms of creating subtype-selective drugs, a variety of structure-guided approaches can be used including targeting allosteric and orthosteric sites (see refs 8,6,48). As the foregoing makes clear, although significant progress has been made towards a comprehensive understanding of the structural genomics of human neurotransmitter GPCRs, a vast amount of work remains which will require the integrated and coordinated efforts of structural biologists, pharmacologists, chemists and computational biologists.

STRUCTURAL INSIGHTS INTO NEUROTRANSMITTER-BASED GPCR ACTIVATION AND BIASED SIGNALING

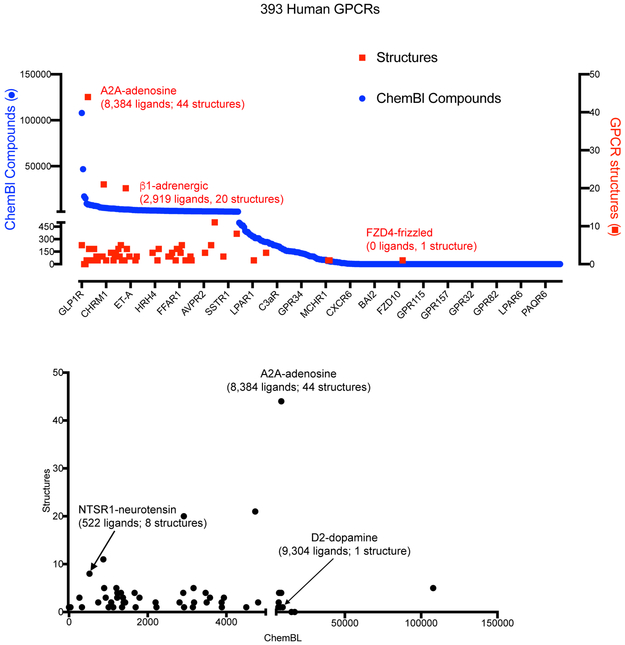

As is the case with GPCR structural genomics, considerable insights into the structural features of neurotransmitter-targeted GPCR activation and biased signaling have been obtained. With regard to GPCR activation, the first structure of a GPCR in complex with hetereotrimeric G proteins was obtained in 2011 49 and since then several structures of nanobody (e.g. β2-adrenergic 50 M2-muscarinic 51,52 and μ-opioid53 receptors) and heterotrimeric G protein-stabilized active states (e.g. calcitonin54 cacitonin gene related peptide 55,56 5-HT1B-serotonin 57,58 μ-opioid 59 and glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) 60 receptors) have appeared—essentially all with neurotransmitter-targeted GPCRs. Further, structures of arrestin-biased agonists at 5-HT2B receptors 32,61,62, arrestin-bound rhodopsin 63 and G-protein biased agonists at GLP-1 receptors 64 have been reported. Finally, there are inactive-state structures stabilized by sodium (e.g. A2A-adenosine65 δ-opioid 66 and D4-dopamine34 receptors), negatively modulating allosteric nanobodies at the β2-adernergic receptor67 and the ligand-free basal structure of the FZD4-frizzled receptor40. Fig 3 depicts representative structures of these various states along with a graphical representation of an extended ternary complex model of receptor activation that includes both G protein-68 and β-arrestin-[see ref69] stabilized complexes. The outward movement of TM6 is the hallmark for GPCR activation along with several other canonical rearrangements 49,53. These include rearrangements of several micro-switches 32 as follows: (1) residues P5.50, I3.40and F6.44 which form the P-I-F motif. Here there is an inward shift of P5.50 along with a rotomer switch of13.40 and a large inward movement of F6.44. Additional microswitches which undergo rearrangement include the D(E)/RY motif in TM III and the NPxxY motif in TM VII. The salt bridge between D3.49 and R3.50 is typically broken in active-state structures 49,53. At the NPxxY motif activation reveals a rotation of Y7.53. Additionally the sodium site collapses due to rearrangements of key residues coordinating sodium 53. Finally there is typically a large outward movement (10-15 Å) of the cytoplasmic end of TMVI which facilitates interactions with G proteins 49and other transducers 53. In general, the ‘active-like’ receptor states in Fig 3 show the various transitions mentioned above without the large outward movement of TMVI.

FIGURE 3. Structural validation of the extended ternary complex model of GPCR action.

The extended ternary complex model 68,69,6 predicts the existence of multiple interconvertible GPCR states stabilized by ligands (agonists, neutral antagonists and inverse agonists) and transducers (G proteins, arrestins and other transducers). The figure depicts various high resolution structures which have provided validation for this schema. These states include: inactive states stabilized by allosteric nanobodies (RL2) 67, active (R*L; 70) and inactive sodium-bound 66 states stabilized by agonists and inverse agonists, respectively; as well as coupled states (R*GL and R**LβARR). The model also provides for the possibility of biased signaling due to agonist-induced stabilization of distinct active and coupled states 32,31 (e.g. R*L and R**L). Finally, spontaneously active (R*) and coupled (R*G) states which have been demonstrated in many systems 68 are predicted to exist although structures of these are not yet available.

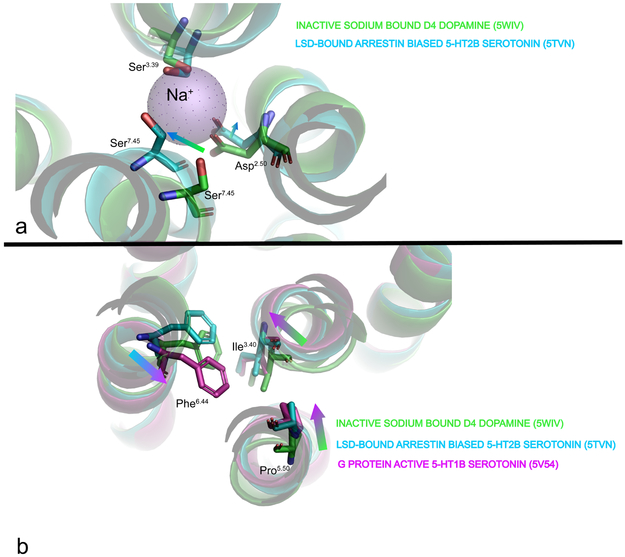

Currently, there are two published structures of GPCRs complexed with β-arrestin (β-ARR) biased agonists including LSD 70 and ergotamine 32 with the 5-HT2B serotonin receptor and one structure of a G-protein biased ligand complexed with hetereotrimeric G-protein for the GLP-1 receptor 64. The β-ARR-biased agonist structures (Figs 3 and 4) appear to represent an ‘intermediate’ state between the signaling complex states and the inactive states. Notably, the sodium site is collapsed, with rearrangements of key residues that stabilize the bound sodium ion including, using the Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering convention71, Ser3.39 and Asp2.50 (Fig 4A). Notably Ser7.45 rotates in to occlude the sodium pocket (Fig 4a). Additionally, a key extracellular residue in loop 2–L209EL2 appears to form a ‘lid’ over LSD, retarding its dissociation and being essential for arrestin recruitment. A similar role of the same EL2 residue was verified in studies of the D2-dopamine receptor and several other biogenic amine receptors 61,72,62. Notably the ‘P-I-F’ and NPXXY motifs along with conformational rearrangements in TM6 and TM7 are consistent with an intermediate activated state 61 (Fig 4b). Taken together, these rearrangements suggest that concerted conformational changes involving residues throughout the receptor, albeit not fully mimicking the changes in the rhodopsin–arrestin complex (ref 63), are responsible for the arrestin-biased conformation which favor arrestin binding (Fig 4b). By contrast, the GLP-1 complex with the G-protein biased agonist extendin-P5 shows the most pronounced difference in TM1, along with extracellular regions of TM6, TM7 and extracellular loop 3 (EL3), for which there is support by extensive mutagenesis (see ref64 for details).

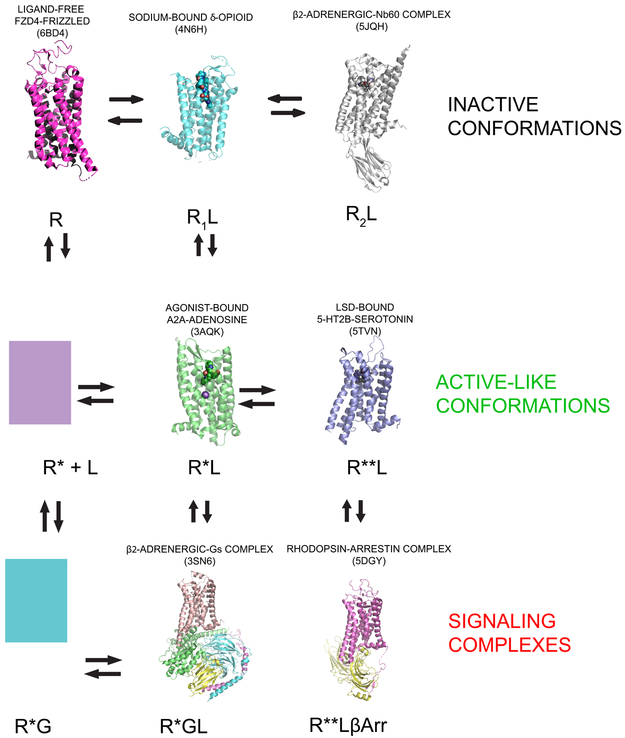

FIGURE 4. Structural rearrangements associated with distinct GPCR states.

(a) shows rearrangements within the sodium pocket associated with stabilization of an arrestin-biased state of the 5-HT2B serotonin receptor. Green depicts the inactive sodium-stabilized state of the D4 dopamine receptor while cyan shows the LSD-bound 5-HT2B receptor. As can be seen, key residues involved in stabilizing sodium (Ser3.39 and Asp2.59) along with Ser 7.45 collapse to occlude the sodium site. (b) shows rearrangements in the P-I-F motif associated with inactive (green), G-protein (magenta) and arrestin-biased (cyan) conformations.

The inactive states typically show a conserved sodium site with sodium visualized in the highest resolution structures 34,65,66 Additionally a conserved ‘ionic lock’ between D/E3.49 (of the D(E)/RY motif and N6.30 which stabilizes the ground state of several GPCRs 73,74 is occasionally seen. Remarkably in an inactive state stabilized by Nb60 and carazolol 67 this ionic lock is recapitulated by the nanobody. Addtionally in many inactive-state structures the P-I-F, NPxxY and D(E)/RY motifs are all in a generally conserved ‘inactive-like’ state.

The above studies demonstrate clear progress in the understanding of the structural features required for different modalities of receptor activation and signaling. Clearly, much remains to be done in this direction, and the discovery of many novel permutations of these features is eagerly anticipated.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR STRUCTURE-GUIDED DRUG DESIGN AND DISCOVERY FOR NEUROTRANSMITTER TARGETED GPCRS

Selectivity:

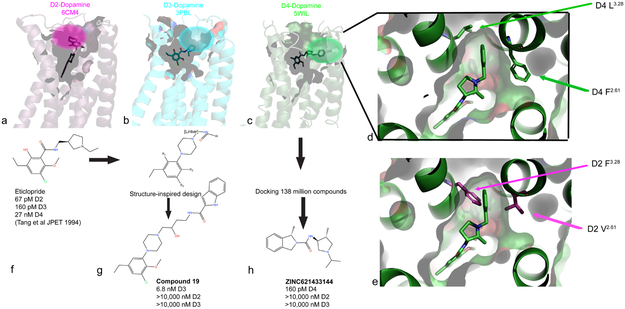

Given the large number of GPCR structures and reasonable coverage of some GPCR families, these structures should, at least in theory, be useful for the de novo design of selective drugs. This is particularly true when new ‘pockets’ are discovered, as was the case for the D2 75, D3 76 and D4 34 dopamine receptors. As shown in Fig 5a-c, these structures revealed potentially unique binding surfaces that could be exploited for the design of selective ligands. Fig 5d shows a more detailed view of the D4-selectivity filter while 5e shows how this is occluded in the D2 receptor34. Given that all three structures were obtained with chemically distinct and non-selective ligands, however, it is conceivable that the different binding pockets might simply reflect the fact that different ligands with distinct chemical scaffolds (e.g. different chemotypes) engage different residues in the receptors. One way to test the hypothesis that these different binding pockets are pharmacologically relevant is to create new ligands that are designed to engage these ‘selectivity filters’. For the D3 receptor, remarkable success was achieved 77 with a compound with 1700-fold selectivity for the D3 receptor, and minimal off-target activity (Fig 5). Then, starting with the seed compound eticlopride (5f), which is a potent and non-selective D2 and D3 antagonist with weaker activity at D4, the group used a combination of docking and medicinal chemistry to identify a potential modified scaffold predicted to target a putative selectivity region within the D3 receptor previously identified by mutagenesis and molecular modeling 76 (Fig 5g). Via this structure-inspired design approach, Compound 19 (5g) was eventually synthesized and found to be a potent and selective D3 antagonist.

FIGURE 5. Structure-guided design of selective GPCR ligands for dopaminergic modulating neurotransmission.

As shown, structures of the three members of the D2-family dopamine receptor family have been solved: (a) D2 75 shown in magenta, (b) D3 76 shown in cyan and (c) D4 34 in green. (d) shows the location of the D4-selectivity filter with nemonapride bound in green while (e) shows that this is occluded in the D2 receptor (D2 residues magenta). As described in the text, the D3 receptor structure was used to modify the non-selective D3 inverse agonist eticlopride (f) to Compound 19 (g) which has high affinity and selectivity. Alternatively, ultra-large scale docking led directly to ZINC621433144 (h) which emerged as a pM selective D4 agonist 79

An alternative approach is to target these ‘selectivity filters’ via automated docking (5c-e). In an initial proof-of-concept study, the D4-dopamine receptor selectivity filter was targeted by a docking campaign of 600,000 commercially-available compounds 34 from the ZINC database 78. A set of ‘seed’ compounds discovered from the initial docking campaign was further optimized by docking and subsequent identification of analogs, which ultimately led to the highly selective D4 partial agonist Compound 9-6-24 34 which was >1000-fold selective for the D4 receptor and lacked activity at 320 other GPCRs.

More recently the computational approach has been enhanced by automated docking-based screening of ultra-large libraries in a campaign with 138 million drug-like compounds. This in silico screening campaign, wherein each compound was docked in >100,000 conformations, required the analysis and scoring of 70 trillion docking events 79 (Fig 5h). In this study, the previously identified D4 selectivity filter 34 comprised of the pocket formed by residues Leu3.28 and Phe2.61 (see Fig 5c-e) was again computationally targeted. This docking campaign led to the discovery of a large number of chemically novel and highly selective D4 ligands. Of these, ZINC621433144 (5h) was the most potent of the agonists tested, with an EC50 of 180 pM and selectivity for D4 over D2 and D3 (Fig 5h). Based on the rate of true positives among the predicted actives, the authors estimate that there could exist as many as 400,000 distinct D4-active compounds having more than 70,000 diverse chemotypes 79 in the library of 138 million compounds. Similar, albeit less computationally intensive, docking-based approaches have yielded selective ligands for the 5-HT1B-serotonin80, κ-opioid 81, D2-dopamine81 and other receptors [see refs8,82 for reviews)

Structure-guided design of biased ligands for neurotransmitter receptors

Functional selectivity, also known as biased signaling83, has been defined as the process by which “ligands induce (or stabilize) unique, ligand-specific receptor conformations… result(ing) in differential activation of signal transduction pathways associated with that particular receptor” 83. The phenomenon of functional selectivity occurs when different ligands at the same receptor lead to preferential activation of different G proteins (e.g. G-protein subtype bias), a preference for G-protein signaling over arrestin (e.g. G-protein bias) or a preference for arrestin signaling (e.g. arrestin bias) over G-proteins. Reports of functional selectivity at GPCRs have appeared for many decades (see Ref 84 for example) and such bias is now recognized as a nearly universal phenomenon for GPCRs 6. Indeed there, are now multiple reports of the discovery and optimization of arrestin85,86- and G-protein87-89 biased ligands for many GPCRs [see refs6,90,91 for recent reviews]. As mentioned above, to date there is only one structure of a GPCR (a GLP-1 receptor) in complex with G-protein biased ligand (peptide exendin-P5) and hetereotrimeric G proteins64, a handful of structures of arrestin-biased ligands complexed with the 5-HT2B serotonin receptor32,62,70 and no structures of arrestin-biased ligands in a GPCR-arrestin complex. Thus, although there is a paucity of structural information regarding GPCR functional selectivity, there have been several reports in which structure-informed and structure-inspired design of neurotransmitter targeted G-protein and arrestin-biased ligands have been achieved.

For example, Manglik et al92 reported the discovery of G-protein biased agonists for the μ opioid receptor although this discovery was accomplished without knowledge of any of the structural features responsible for biased signaling. In that study, molecular docking of 3 million compounds was performed against the inactive conformation of the μ opioid receptor targeting a highly conserved aspartic acid (Asp3.32) and engaging a conserved water network and tyrosine (Tyr3.33) putatively involved in selectivity and agonist activity. Compounds with predicted activity were tested for functional activity at G-protein and arrestin signaling and, after several rounds of medicinal chemistry optimization, PZM21 was identified as a potent and efficacious G-protein biased agonist92. Similar G-protein biased ligands have been discovered for μ–93,94 and κ-89,95 opioid receptors, albeit without being informed by structural determinants. On the other hand, via a combination of molecular dynamics and synthetic studies, a Salvinorin A96 -derivative was discovered for μ-opioid receptors97 that was G-protein biased, and thus likely has reduced abuse potential. Similarly, in a recent study of κ-opioid receptors, residues identified from structural studies as being essential for biased signaling ultimately led to the creation of novel structure-guided G-protein biased opioid agonists52.

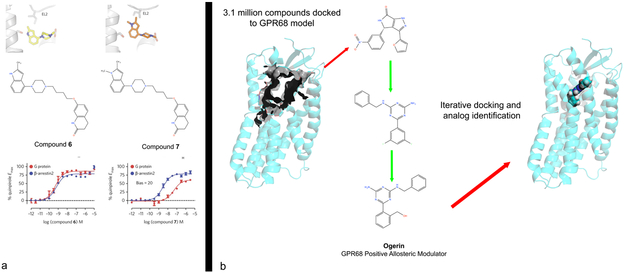

Additionally, McCorvy et al72 provided a structure-inspired approach for creating biased ligands at aminergic GPCRs—all of which are essential targets for the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine and histamine. For this study, they took advantage of prior studies indicating that interactions with TMV serine and other residues are essential for G-protein signaling62 at aminergic GPCRs, while interactions with EL2 residues can be essential for arrestin signaling61. Via a combination of molecular modeling, molecular dynamics simulations, automated docking and synthesis, the arrestin-biased Compound 7 was discovered for the D2-dopamine receptor72 (Fig 6a). As previous studies have shown that such arrestin-biased compounds may have efficacy in treating schizophrenia and related neuropsychiatric disorders 85,98, this could represent a useful approach for optimizing arrestin-biased medications for treating neuropsychiatric disorders. Finally, it is also worth mentioning that biased signaling might be influenced on the level of recruitment of and receptor phosphorylation by GPCR kinases (GRKs) 99 and this potentially can be influenced by GPCR ligands.

FIGURE 6. Structure-inspired design of ligands for GPCRs to modulate synaptic transmission.

(a) depicts strategy (see text for details) to design ligands with arrestin bias for biogenic amine neurotransmitter receptors 72. Here using a combination of molecular dynamics simulations, docking and medicinal chemistry, compounds were created which were predicted to interact with a conserved EL2 residue which can impart arrestin bias (b) depicts computational strategy to discovery small molecule probes to modulate orphan synaptic GPCRs such as GPR68 102 Here, 3.1 million compounds were docked to a model of GPR68 and then via iterative docking and testing of analogs ogerin was identified as a selective GPR68 positive allosteric modulator.

Orphan and understudied GPCRs

As previously mentioned, nearly 50% of GPCRs—most of which are highly expressed in the brain14--have a paucity of known ligands. Even for those neurotransmitter receptors that have been the subject of intensive investigation, such as muscarinic and dopamine receptors, the identification of suitably selective ligands for the various subtypes continues to be challenging. Thus, for instance, there are no truly selective D5-dopamine or M5-muscarinic receptor agonists, although a modestly selective D5100 – and a fairly selective M5101 antagonist have been reported. Unfortunately, off-target pharmacology has not been reported for these compounds, so their selectivity over other GPCRs is unknown.

Although there are no published structures of orphan or understudied brain GPCRs (oGPCRs38), the use of homology models and automated docking provides a structure-inspired approach for ligand discovery. Thus for instance, an integrated approach using parallel screening, homology modeling, docking and analog synthesis led to ogerin—a selective positive allosteric modulator for GPR68—and selective negative allosteric modulators for GPR65 102 (Fig 6b). The allosteric modulator ogerin was demonstrated to affect learning and behavior in mice, indicating that GPR68 is a potentially important GPCR in the brain 102. A similar approach led to the discovery of selective agonists for the oGPCR MRGPRX2 which is involved in pain and itch 103 and binds many important neurotransmitters including substance P and other peptides 103. These approaches are facilitated by parallel-screening approaches in which 100’s of oGPCRs can be screened simultaneously 102,104 ; active compounds are used to inform homology models for docking and subsequent discovery of new ligands102,103,105-107.

Genetic and model organism studies are also facilitating the understanding of the potential therapeutic importance of oGPCRs for neuropsychiatric disease. Thus, a very recent study indicates that the orphan GPCR MRGPRX4 is involved in the pain and itch sensations mediated by bile acids 108 Another recent study shows that MRGPRX4 is also essential for the preference for menthol cigarettes in certain ethnic populations109. Given the distribution of MRGPRX4 in peripheral nerves, it is likely that MRGPRX4 and related receptors are neurotransmitter receptors involved in peripheral sensations like pain and itch 110. Databases devoted to oGPCR brain distribution39,111,112 should facilitate discovering their endogenous neurotransmitters, function and neuropsychiatric implications for pathogenesis and treatment.

Polypharmacology

Historically, the most effective drugs for many complex neuropsychiatrc diseases have targeted multiple GPCRs and other molecular targets9,113. It is now understood that this is likely because of the exceedingly complex genetic landscape of common diseases in which 100’s-1000’s of genes might exert small effects114. This has led to the understanding that complex diseases are omnigenic rather than polygenic114—meaning that nearly every gene may ultimately exert a small effect on core disease pathways. Perhaps not surprisingly, the desire to discover increasingly selective drugs has resulted in lower overall success rates of drug discovery campaigns115. This lack of success has led to the hypothesis that generating polypharmacologic drugs with designated multiple targets represents a useful approach for treating complex diseases 113,116. For aminergic GPCRs, there has been some recent success in discovering the structural features responsible for polypharmacological activities 33 which comprises a series of 9 semi-conserved residues (Asp3.32, Ile/Val3.33; Cys3.36, Thr3.37, Ala/Ser/Thr5.46, Trp6.48, Phe6.51, Phe6.52, EL2Val/Ile/Leu). Although in theory structure-guided approaches should be helpful for the discovery and design of polypharmacological drugs, to date, this has not been entirely successful117,118

THERAPEUTIC AND COMMERCIAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR STRUCTURE-GUIDED GPCR DRUG DISCOVERY

Heptares (acquired by Sosei in 2016) 119, and Receptos (acquired by Celgene in 2015120) along with Conformetrix 121 have invested considerable resources to bring GPCR structure-guided drug discovery to fruition. To date, publicly available information indicates that the exemplar compounds are targeted mainly to well-studied GPCRs for which selective ligands are difficult to obtain. Thus, for instance, Heptares has advanced an M4-selective agonist to Phase I trials, presumably for cognition enhancement (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03244228?term=heptares&rank=4). Heptares has also brought a structure-guided mGlu5 negative allosteric modulator122 for metabotropic glutamate receptors to initial Phase I trials, presumably for a central nervous system application (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03785054?term=heptares&rank=2). Receptos, in partnership with Celgene, has advanced RPC1063 (an S1P receptor agonist for treating multiple sclerosis https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/detailedIndex.cfm?cfgridkey=611517) to Phase III clinical trials.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Given the wealth of structural information now available for many GPCRs, it is anticipated that structure-guided approaches will eventually lead to neuropsychiatric medications with greater efficacy and fewer side-effects. As on- and off-target side-effects, along with clinical effectiveness and safety, continue to be major drivers of drug failures in clinical trials123, insights into the structural basis of ligand engagement could provide new opportunities for GPCR-based neuropsychiatric drug discovery. Thus, where a G-protein biased ligand might show greater efficacy and fewer side-effects, insights into the structural basis of such bias could accelerate the discovery of novel chemotypes with biased signaling patterns. Indeed, this approach has been successful in generating biased tool compounds for many neurotransmitter receptors, including D4-dopamine34,124, μ-opioid92 and others62,72. Although there are currently no structure-guided biased drugs in clinical trials, encouraging results have appeared for TRV-130 as a G protein-biased opioid receptor agonist for pain125, albeit with some abuse liabilities as manifested in preclinical studies126,127.

As is clear from the foregoing, the past decade has witnessed astounding progress in understanding the structure and function of metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors. This increasing wealth of structural information, and advances in structure guided and inspired drug discovery, promise to accelerate the discovery of drugs targeting metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors with improved efficacies and fewer side-effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Wes Kroeze, PhD and the Editor for helpful editing and comments. Work described in this review was funded by grants and contracts from the National Institute of Health as well as the Michael Hooker Distinguished Professorship.

REFERENCESβ

- 1.Ullrich A & Schlessinger J Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell 61, 203–212, (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz S et al. The guanylate cyclase/receptor family of proteins. FASEB J 3, 2026–2035, (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinkers M et al. A membrane form of guanylate cyclase is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Nature 338, 78–83, (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purves D et al. Neuroscience, 2nd Edition Two Families of Postsynaptic Receptors. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10855/ (Sinauer Associates, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overington JP et al. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov 5, 993–996, (2006).A classic paper which provides estimates for the size of the 'druggable' genome

- 6.Wacker D et al. How Ligands Illuminate GPCR Molecular Pharmacology. Cell 170, 414–427, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser AS et al. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 829–842, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth BL et al. Discovery of new GPCR ligands to illuminate new biology. Nat Chem Biol 13, 1143–1151, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth BL et al. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 353–359, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marder SR et al. Advancing drug discovery for schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1236, 30–43, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fricker LD & Devi LA Orphan neuropeptides and receptors: Novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther 185, 26–33, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lein ES et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature 445, 168–176, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerfen CR et al. GENSAT BAC cre-recombinase driver lines to study the functional organization of cerebral cortical and basal ganglia circuits. Neuron 80, 1368–1383, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regard JB et al. Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell 135, 561–571, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greengard P The neurobiology of slow synaptic transmission. Science 294, 1024–1030, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger M et al. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med 60, 355–366, (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCorvy JD & Roth BL Structure and function of serotonin G protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther 150, 129–142, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade R et al. A G protein couples serotonin and GABAB receptors to the same channels in hippocampus. Science 234, 1261–1265, (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackmer T et al. G protein betagamma directly regulates SNARE protein fusion machinery for secretory granule exocytosis. Nat Neurosci 8, 421–425, (2005).One of the first demonstrations that G protein β/γ subunits regulate vesicle fusion machinery to inhibit synaptic transmission

- 20.Gerachshenko T et al. Gbetagamma acts at the C terminus of SNAP-25 to mediate presynaptic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 8, 597–605, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skeberdis VA et al. Protein kinase A regulates calcium permeability of NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci 9, 501–510, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver CM & Shapiro MS Gq-Coupled Muscarinic Receptor Enhancement of KCNQ2/3 Channels and Activation of TRPC Channels in Multimodal Control of Excitability in Dentate Gyrus Granule Cells. J Neurosci 39, 1566–1587, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens RC & Wilson IA Tech.Sight. Industrializing structural biology. Science 293, 519–520, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schertler G et al. Projection structure of rhodopsin. Nature 362, 770–771, (1993).The first cryo-EM structure of a membrane protein.

- 25.Baldwin JM The probable arrangement of the helices in G protein-coupled receptors. Embo J 12, 1693–1703, (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palczewski K et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289, 739–745, (2000).The first crystal structure of a GPCR

- 27.Rosenbaum DM et al. GPCR engineering yields high-resolution structural insights into beta2-adrenergic receptor function. Science 318, 1266–1273, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen SGF et al. Crystal Structure of the Human b2 Adrenergic G-Protein-Coupled Receptor. Nature 450, 383–387, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherezov V et al. High-Resolution Structure of an Engineered Human b2-Adrenergic G Protein-Coupled Receptor. Science 318, 1258–1265, (2007).References 27-29 provide the first crystal structures of non-opsin GPCRs

- 30.Katritch V et al. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 53, 531–556, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C et al. Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 610–614, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wacker D et al. Structural features for functional selectivity at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 615–619, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng Y et al. 5-HT2C Receptor Structures Reveal the Structural Basis of GPCR Polypharmacology. Cell 172, 719–730 e714, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S et al. D4 dopamine receptor high-resolution structures enable the discovery of selective agonists. Science 358, 381–386, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaulton A et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res 40, D1100–1107, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth B et al. Multiplicity of serotonin receptors: useless diverse molecules or an embarrassement of riches? The Neuroscientist 6, 252–262, (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y et al. PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res 37, W623–633, (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth BL & Kroeze WK Integrated Approaches for Genome-wide Interrogation of the Druggable Non-olfactory G Protein-coupled Receptor Superfamily. J Biol Chem 290, 19471–19477, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oprea TI et al. Unexplored therapeutic opportunities in the human genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 377, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang S et al. Crystal structure of the Frizzled 4 receptor in a ligand-free state. Nature 560, 666–670, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimamura T et al. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature 475, 65–70, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haga K et al. Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature 482, 547–551, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruse AC et al. Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 482, 552–556, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thal DM et al. Crystal structures of the M1 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Nature 531, 335–340, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H et al. Structure-guided development of selective M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 12046–12050, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vardigan JD et al. Improved cognition without adverse effects: novel M1 muscarinic potentiator compares favorably to donepezil and xanomeline in rhesus monkey. Psychopharmacology (Berl), (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster DJ et al. Activation of M1 and M4 muscarinic receptors as potential treatments for Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10, 183–191, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thal DM et al. Structural insights into G-protein-coupled receptor allostery. Nature 559, 45–53, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasmussen SG et al. Crystal structure of the beta2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555, (2011).The first structure of a GPCR complexed in its active state with a G protein hetereotrimer

- 50.Rasmussen SG et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the beta(2) adrenoceptor. Nature 469, 175–180, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruse AC et al. Activation and allosteric modulation of a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 504, 101–106, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Che T et al. Structure of the Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Kappa Opioid Receptor. Cell 172, 55–67 e15, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang W et al. Structural insights into micro-opioid receptor activation. Nature 524, 315–321, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang YL et al. Phase-plate cryo-EM structure of a class B GPCR-G-protein complex. Nature 546, 118–123, (2017).The first cryo-EM structure of an active GPCR complexed with G protein

- 55.Liang YL et al. Cryo-EM structure of the active, Gs-protein complexed, human CGRP receptor. Nature 561, 492–497, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Draper-Joyce CJ et al. Structure of the adenosine-bound human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi complex. Nature 558, 559–563, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia-Nafria J et al. Cryo-EM structure of the serotonin 5-HT1B receptor coupled to heterotrimeric Go. Nature 558, 620–623, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia-Nafria J et al. Cryo-EM structure of the adenosine A2A receptor coupled to an engineered heterotrimeric G protein. Elife 7, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koehl A et al. Structure of the micro-opioid receptor-Gi protein complex. Nature 558, 547–552, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y et al. Cryo-EM structure of the activated GLP-1 receptor in complex with a G protein. Nature 546, 248–253, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wacker D et al. Crystal structure of an LSD-bound human serotonin receptor. Cell, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCorvy JD et al. Structural determinants of 5-HT2B receptor activation and biased agonism. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 787–796, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang Y et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 523, 561–567, (2015).The first crystal structure of a GPCR with arrestin

- 64.Liang YL et al. Phase-plate cryo-EM structure of a biased agonist-bound human GLP-1 receptor-Gs complex. Nature 555, 121–125, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu W et al. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of GPCRs by sodium ions. Science 337, 232–236, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fenalti G et al. Molecular control of delta-opioid receptor signalling. Nature 506, 191–196, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Staus DP et al. Allosteric nanobodies reveal the dynamic range and diverse mechanisms of G-protein-coupled receptor activation. Nature 535, 448–452, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Samama P et al. A mutation-induced activated state of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor. Extending the ternary complex model. J Biol Chem 268, 4625–4636, (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roth BL DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron 89, 683–694, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wacker D et al. Crystal Structure of an LSD-Bound Human Serotonin Receptor. Cell 168, 377–389 e312, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ballesteros JA & Weinstein H Integrated Methods for the Construction of Three-Dimensional Models and Computational Probing of Structure-Function Relations in G Protein-Coupled Receptors. METHODS IN NEUROSCIENCES 25, 366, (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCorvy JD et al. Structure-inspired design of beta-arrestin-biased ligands for aminergic GPCRs. Nat Chem Biol 14, 126–134, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ballesteros JA et al. Activation of the b2-Adrenergic Receptor Involves Disruption of an Ionic Lock between the Cytoplasmic Ends of Transmembrane Segments 3 and 6. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29171–29177, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shapiro DA et al. Evidence for a model of agonist-induced activation of 5-HT2A serotonin receptors which involves the disruption of a strong ionic interaction between helices 3 and 6. J Biol Chem 18, 18, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang S et al. Structure of the D2 dopamine receptor bound to the atypical antipsychotic drug risperidone. Nature 555, 269–273, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chien EY et al. Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science 330, 1091–1095, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumar V et al. Highly Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor (D3R) Antagonists and Partial Agonists Based on Eticlopride and the D3R Crystal Structure: New Leads for Opioid Dependence Treatment. J Med Chem 59, 7634–7650, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Irwin JJ & Shoichet BK ZINC--a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model 45, 177–182, (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyu J et al. Ultra-large library docking for discovering new chemotypes. Nature 566, 224–229, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodriguez D et al. Structure-based discovery of selective serotonin 5-HT(1B) receptor ligands. Structure 22, 1140–1151, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Negri A et al. Discovery of a novel selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist using crystal structure-based virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model 53, 521–526, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Irwin JJ & Shoichet BK Docking Screens for Novel Ligands Conferring New Biology. J Med Chem 59, 4103–4120, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Urban JD et al. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320, 1–13, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roth BL & Chuang D-M Minireview: multiple mechanisms of serotonergic signal transduction. Life Sciences 41, 1051–1064, (1987).The first explication of the principles of functional selectivity and biaed agonism and anatagonism

- 85.Allen JA et al. Discovery of beta-arrestin-biased dopamine D2 ligands for probing signal transduction pathways essential for antipsychotic efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 18488–18493, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boerrigter G et al. Cardiorenal actions of TRV120027, a novel ss-arrestin-biased ligand at the angiotensin II type I receptor, in healthy and heart failure canines: a novel therapeutic strategy for acute heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 4, 770–778, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen X et al. Discovery of G Protein-Biased D2 Dopamine Receptor Partial Agonists. J Med Chem 59, 10601–10618, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen XT et al. Structure-activity relationships and discovery of a G protein biased mu opioid receptor ligand, [(3-methoxythiophen-2-yl)methyl]({2-[(9R)-9-(pyridin-2-yl)-6-oxaspiro-[4.5]decan- 9-yl]ethyl})amine (TRV130), for the treatment of acute severe pain. J Med Chem 56, 8019–8031, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lovell KM et al. Structure-activity relationship studies of functionally selective kappa opioid receptor agonists that modulate ERK 1/2 phosphorylation while preserving G protein over betaarrestin2 signaling bias. ACS Chem Neurosci 6, 1411–1419, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wootten D et al. Mechanisms of signalling and biased agonism in G protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 638–653, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith JS et al. Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat Rev Drug Discov, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manglik A et al. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 537, 185–190, (2016).Structure-guided discovery of biased ligands.

- 93.Varadi A et al. Mitragynine/Corynantheidine Pseudoindoxyls As Opioid Analgesics with Mu Agonism and Delta Antagonism, Which Do Not Recruit beta-Arrestin-2. J Med Chem 59, 8381–8397, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schmid CL et al. Bias Factor and Therapeutic Window Correlate to Predict Safer Opioid Analgesics. Cell 171,1165–1175 e1113, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.White KL et al. Identification of novel functionally selective kappa-opioid receptor scaffolds. Mol Pharmacol 85, 83–90, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roth BL et al. Salvinorin A: a potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 11934–11939, (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Crowley RS et al. Synthetic Studies of Neoclerodane Diterpenes from Salvia divinorum: Identification of a Potent and Centrally Acting mu Opioid Analgesic with Reduced Abuse Liability. J Med Chem 59, 11027–11038, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park SM et al. Effects of beta-Arrestin-Biased Dopamine D2 Receptor Ligands on Schizophrenia-Like Behavior in Hypoglutamatergic Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 704–715, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Choi M et al. G protein–coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) orchestrate biased agonism at the β2-adrenergic receptor. Sci Signal 11, eaar7084, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mohr P et al. Dopamine/serotonin receptor ligands. 12(1): SAR studies on hexahydro-dibenz[d,g]azecines lead to 4-chloro-7-methyl-5,6,7,8,9,14-hexahydrodibenz[d,g]azecin-3-ol, the first picomolar D5-selective dopamine-receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 49, 2110–2116, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gentry PR et al. Discovery, synthesis and characterization of a highly muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR)-selective M5-orthosteric antagonist, VU0488130 (ML381): a novel molecular probe. ChemMedChem 9, 1677–1682, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huang XP et al. Allosteric ligands for the pharmacologically dark receptors GPR68 and GPR65. Nature 527, 477–483, (2015).Structure-inspired discovery of allosteric ligands for an orphan GPCR

- 103.Lansu K et al. In silico design of novel probes for the atypical opioid receptor MRGPRX2. Nat Chem Biol 13, 529–536, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kroeze WK et al. PRESTO-Tango as an open-source resource for interrogation of the druggable human GPCRome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22, 362–369, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ngo T et al. Orphan receptor ligand discovery by pickpocketing pharmacological neighbors. Nat Chem Biol, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 106.Ngo T et al. Identifying ligands at orphan GPCRs: current status using structure-based approaches. Br J Pharmacol 173, 2934–2951, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trauelsen M et al. Receptor structure-based discovery of non-metabolite agonists for the succinate receptor GPR91. Mol Metab 6, 1585–1596, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meixiong J et al. Identification of a bilirubin receptor that may mediate a component of cholestatic itch. Elife 8, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kozlitina J et al. An African-specific haplotype in MRGPRX4 is associated with menthol cigarette smoking. PLoS Genet 15, e1007916, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dong X et al. A diverse family of GPCRs expressed in specific subsets of nociceptive sensory neurons. Cell 106, 619–632, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ehrlich AT et al. Expression map of 78 brain-expressed mouse orphan GPCRs provides a translational resource for neuropsychiatric research. Commun Biol 1, 102, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oprea TI et al. Far away from the lamppost. PLoS Biol 16, e3000067, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dar AC et al. Chemical genetic discovery of targets and anti-targets for cancer polypharmacology. Nature 486, 80–84, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Boyle EA et al. An Expanded View of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell 169, 1177–1186, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shih HP et al. Drug discovery effectiveness from the standpoint of therapeutic mechanisms and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 78, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Besnard J et al. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature 492, 215–220, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Anighoro A et al. Polypharmacology: challenges and opportunities in drug discovery. J Med Chem 57, 7874–7887, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Weiss DR et al. Selectivity Challenges in Docking Screens for GPCR Targets and Antitargets. J Med Chem 61, 6830–6845, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Micklus A & Muntner S Biopharma deal-making in 2016. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 161–162, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Morrison C & Lahteenmaki R Public biotech in 2015 - the numbers. Nat Biotechnol 34, 709–715, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Blundell CD & Almond A Method for determining three-dimensional structures of dynamic molecules. (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Christopher JA et al. Fragment and Structure-Based Drug Discovery for a Class C GPCR: Discovery of the mGlu5 Negative Allosteric Modulator HTL14242 (3-Chloro-5-[6-(5-fluoropyridin-2-yl)pyrimidin-4-yl]benzonitrile). J Med Chem 58, 6653–6664, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Harrison RK Phase II and phase III failures: 2013-2015. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 817–818, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lyu J et al. Ultra-large library docking for discovering new chemotypes. Nature, (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Singla NK et al. APOLLO-1: a Randomized, Controlled, Phase 3 Study of Oliceridine (TRV130) for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Pain Following Bunionectomy. Spine J 17, S2017, (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 126.Araldi D et al. Mu-opioid Receptor (MOR) Biased Agonists Induce Biphasic Dose-dependent Hyperalgesia and Analgesia, and Hyperalgesic Priming in the Rat. Neuroscience 394, 60–71, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Austin Zamarripa C et al. The G-protein biased mu-opioid agonist, TRV130, produces reinforcing and antinociceptive effects that are comparable to oxycodone in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 192, 158–162, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dore AS et al. Structure of the adenosine A(2A) receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure 19, 1283–1293, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cherezov V et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science 318, 1258–1265, (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Warne T et al. Structure of a beta1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 454, 486–491, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kimura KT et al. Structures of the 5-HT2A receptor in complex with the antipsychotics risperidone and zotepine. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26, 121–128, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hua T et al. Crystal Structure of the Human Cannabinoid Receptor CB1. Cell 167, 750–762 e714, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Manglik A et al. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 485, 321–326, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wu H et al. Structure of the human kappa-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature 485, 327–332, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yin J et al. Structure and ligand-binding mechanism of the human OX1 and OX2 orexin receptors. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23, 293–299, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hanson MA et al. Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science 335, 851–855, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Misono KS et al. Structure, signaling mechanism and regulation of the natriuretic peptide receptor guanylate cyclase. FEBS J 278, 1818–1829, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kunkel MT & Peralta EG Identification of domains conferring G protein regulation on inward rectifier potassium channels. Cell 83, 443–449, (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Alexander GM et al. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron 63, 27–39, (2009).The first paper demonstrating that DREADDs can activate neuronal activity