Abstract

Extranodal adrenal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is very rare, estimated to be around less than 0.2%. Most common sites involved are stomach, intestine and testis. It is very rare for adrenal tumours to present as primary adrenal insufficiency, with an incidence of around 1.2% in patients diagnosed with adrenal masses. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBL) originating from the stomach and metastasizing to bilateral adrenal glands is an extremely uncommon occurrence with only three cases found on review of the literature. We present a case of a 62-year-old African–American man who presented with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and hypotension, later being diagnosed as DLBL of the gastric antrum metastasized to bilateral adrenal glands. Initial laboratory workup revealed including hormonal analysis and cosyntropin test revealed adrenal insufficiency. The patient later died during the hospitalisation after developing respiratory failure, severe hypotension refractory to vasopressors and severe metabolic acidosis.

Keywords: endocrine system, gastroenterology, oncology, endocrine cancer, gastric cancer

Background

Extranodal adrenal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is very rare, reported as being less than 0.2%.1 The most common extranodal sites for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the stomach, intestine and testis.2 3 It is very rare for adrenal tumours to present as primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI), with an incidence of around 1.2% in patients diagnosed with adrenal masses.1 4 We present a case of a 62-year-old African–American man who presented with nausea and vomiting, later being diagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBL) of the gastric antrum metastasized to bilateral adrenal glands. The patient was later found to have adrenal insufficiency.

Case presentation

The patient is a 62-year-old African–American man with Past Medical History (PMH) of hypertension, hepatitis B presented to the emergency department for vomiting, decreased appetite, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. On further questioning, he mentioned that he had vomiting for 1 week, yellowish to greenish in colour, and three episodes on the day of admission. He described the abdominal pain as diffuse pain, with being more severe on the right side of the abdomen.

On general examination, the patient looked cachexic and tachypneic, with no use of accessory muscles. He was lying in bed with no apparent distress. On review of vitals, blood pressure was low 87/48 mm Hg, tachycardic (pulse 117 beats/min) and the respiratory rate was elevated at 22 breaths/min. On examination of the abdomen, there was tenderness on palpation on right middle quadrant. Rest of the examination was unremarkable. No lymphadenopathy or masses were palpated anywhere in the body

Investigations

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further management. Initial laboratory investigation revealed normocytic anaemia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and hypercalcemia. Anion gap was elevated with lactic acidosis, suggesting a mixed anion gap and non-anion-gap metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation (table 1).

Table 1.

Initial laboratory workup for the patient

| Normal ranges | ||

| CBC | ||

| Haemoglobin | 70 g/L | 130–170 g/L |

| Hematocrit | 29.3% | 39%–53% |

| Platelet | 633×109/L | 130−400×109/L |

| CMP | ||

| Sodium | 133 mmol/L | 136–144 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 6.0 mmol/L | 3.6–5.1 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 106 mmol/L | 101–111 mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate | 13 mmol/L | 22–32 mmol/L |

| Anion gap | 14 | 10–12 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 92 mg/dL | 8–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 3.49 mg/dL | 0.4–1.3 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 59 mg/dL | 74–118 mg/dL |

| Calcium | 12.4 mg/dL | 8.9–10.3 mg/dL |

| Albumin | 2.5 g/dL | 3.5–4.8 g/dL |

| Total protein | 5.2 g/dL | 6.1–7.9 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.4 mg/dL | 0.3–1.2 mg/dL |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 12 IU/L | 17–63 IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 29 IU/L | 15–41 IU/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 60 IU/L | 32–91 IU/L |

| Lactic acid | 2.6 mmol/L | 0.5–1.9 mmol/L |

| ABG | ||

| pH | 7.359 | 7.350–7.450 |

| pCO2 | 25.9 mm Hg | 35.0–45.0 mm Hg |

| pO2 | 124.0 mm Hg | 75.0–100.0 mm Hg |

| O2 saturation | 99.1% | 92%–98.5% |

| HIV | Negative | - |

| RPR | Negative | - |

ABG, arterial blood gas; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, complete metabolic profile; RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

Differential diagnosis

At this point, the most likely aetiology of the symptoms was simple gastroenteritis considering the acute history of vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and decreased appetite. Another possibility at that point was of adrenal insufficiency in view of metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation, hyperkalemia and low serum sodium. Malignancy was also suspected due to patient cachectic outlook, hypercalcemia and deranged laboratory tests.

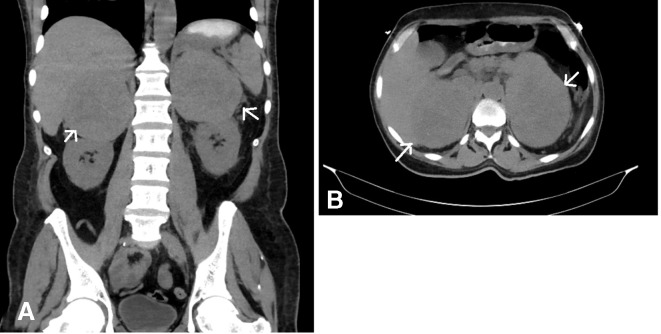

CT abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast was done, which revealed large ulcerated mass lesion in the fundus of the stomach and large bilateral adrenal masses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A & B) Large bilateral adrenal mass lesions, measuring approximately 10.5×8.2 cm on the right and 12.9×8.8 cm on the left, were seen. It also revealed large ulcerated mass in the gastric antrum, although no invasion of the tumour was noted directly into the stomach. Right inguinal prominent lymph, gastrohepatic ligament and left-para aortic adenopathy was also noted.

Treatment

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further management. He was worked up for adrenal insufficiency, which revealed PAI with low aldosterone, ante merīdiem (AM) cortisol, and elevated renin levels. The patient also failed the cosyntropin stimulation test, as it failed to elevate the cortisol levels. Twenty-four hour urine collection revealed low metanephrine levels (table 2). He was started on glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Hypercalcemia was managed with hydration and pamidronate. Skeletal survey was negative for any bone lesions anywhere in the body. Further evaluation also revealed positive serology for active hepatitis B infection with a viral load of around 50 000.

Table 2.

Adrenal function test

| Normal range | ||

| 17-α-hydroxy progesterone | <10 ng/dL | 27–199 ng/dL |

| Aldosterone | 1.0 | 0.0–30.0 |

| Renin | 8.79 ng/mL/hour | 0.167–5.380 ng/mL/hour |

| Cortisol AM | 7.9 | 12–25 µg/dL |

| Cortisol after ACTH stimulation test | 10.9 | >18 µg/dL |

| 24 -hour urine metanephrine | 4 µg/dL | 45–290 µg/dL |

| 24-hour urine normetanephrine | 186 µg/dL | 82–500 µg/dL |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropin hormone.

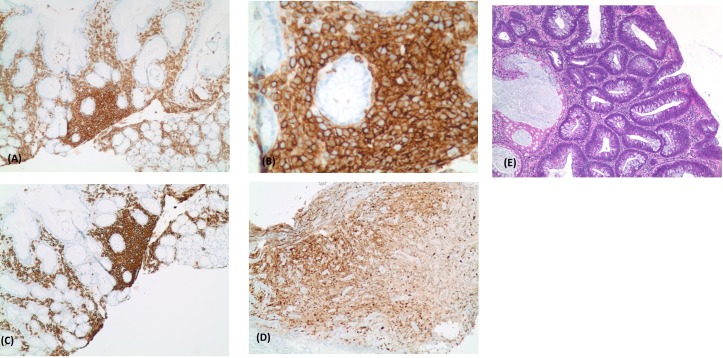

Gastroenterology was consulted and the patient was scheduled to undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which revealed malignant ulcer in the cardia and antrum of the stomach. No perforation was seen (figure 2). Duodenum, gastroesophageal junction and oesophagus were normal. A biopsy was taken of the ulcers, which revealed atypical B-cell lymphoid infiltrate, compatible with large B-cell lymphoma of non-germinal centre cell type (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed malignant ulcer in the cardia and antrum of the stomach.

Figure 3.

(E) Proliferation of large atypical cells within necrotic background. These atypical cells were positive for CD45 (A , B), CD20 (C) and MUM-1 (D), and negative for CD10. Morphologic and phenotypes findings were consistent with large B-cell lymphoma of non-germinal centre cell type (activated B-cell type).

At this point, it was believed that bilateral adrenal masses were most likely metastasis from gastric mass and plan was to do CT guided adrenal gland biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, but the patient was very uncooperative and biopsy was cancelled.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was upgraded to intensive care unit after he developed severe hypotension unresponsive to fluid challenge administration associated with acute renal failure, altered mental sensation and impending respiratory failure with severe metabolic acidosis and refractory hyperventilation. The patient was intubated and placed on a mechanical ventilator. He was started on vasopressors, but he continued to deteriorate. He later developed hypocalcemia, was given calcium gluconate. Lactic acidosis worsened and developed severe metabolic acidosis, after which bicarbonate drip was started. Later he became bradycardic and went into asystole. Despite adequate resuscitation, the patient was declared dead.

Discussion

DLBL with gastrointestinal tract as the primary tumour origin and bilateral adrenal gland metastasis is a very rare occurrence. In our review of the literature, we were able to find only two cases with DLBL of the stomach with bilateral adrenal gland metastasis.

Adrenal glands are one of the common sites for metastasis, mainly due to their high vascular supply. It is estimated that 50%–75% of incidental adrenal masses are most often due to metastasis in patients with malignant disease. More than 90% of metastatic adrenal tumours are carcinoma, with the majority being adenocarcinoma. The most common primary sites are lung (35%), followed by the stomach (14%), oesophagus (12%) and the liver/bile ducts (10%). Majority of the patients have bilateral adrenal glands involvement, typically having greater than 3 cm masses.4 5 On abdominal CT without contrast, suprarenal masses usually appear hypodense and homogenous when compared with muscles.6 In our case the patient had bilateral adrenal masses, with sizes greater than 10 cm in both glands.

An extensive review of the literature was done using PubMed and Google scholar. We identified only three cases published in the literature who had gastrointestinal DLBL with bilateral adrenal masses, two had gastric involvement, while one had duodenal.7 8 Adrenal insufficiency was noted in two cases similar to our patient. Almost all patients presented with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, similar to our patient (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of symptoms, treatment and outcome in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma in gastrointestinal tract and bilateral adrenal glands

| Authors | Age, sex | Symptoms | PAI present? | GI Lesion | Treatment | Outcome |

| Huminer et al 7 | 73, Female | Hypotension, nausea | Yes | Ulcer in stomach | – | – |

| Wakabayashi et al 8 | 60, Male | Nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite | No | Ulcer on lesser curvature at angulus | Chemotherapy | Completed 14 months of treatment, in complete remission |

| Nishiuchi et al 11 | 73, Male | General malaise, high fever, skin pigmentation | Yes | Haemorrhage in duodenal mucosa | Chemotherapy | Alive and in remission |

| Hassan et al | 62, Male | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, hypotension | Yes | Ulcer in the cardia and antrum of the stomach | – | Death within 1 week |

GI, gastrointestinal; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency.

It is very rare for adrenal lymphoma to present with PAI, with estimated incidence to be around 3% in patients who have adrenal lymphoma with bilateral adrenal disease.9 In a series of 173 patients who had lymphoma, only 7 patients had adrenal involvement, out of which only 3 patients had tumour involvement in the adrenal glands bilaterally, with only one patient with adrenal insufficiency.10 In our case the patient demonstrated adrenal insufficiency as confirmed by the hormonal analysis, cosyntropin test and electrolyte imbalance.

Learning points.

Adrenal glands are the most common sites for metastasis. Ninety percent of metastatic adrenal tumours are carcinomas.

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma very rarely originates from stomach and metastasizes to bilateral adrenal glands.

Adrenal masses very rarely present as primary adrenal insufficiency.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH was responsible for conception and design of the study. All authors were involved in data gathering, literature review, analysis of data and writing of the initial manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer 1972;29:252–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weindorf SC, Smith LB, Owens SR. Update on gastrointestinal lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018;142:1347–51. 10.5858/arpa.2018-0275-RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Magnoli F, Bernasconi B, Vivian L, et al. Primary extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: Many sites, many entities? Clinico-pathological, immunohistochemical and cytogenetic study of 106 cases. Cancer Genet 2018;228-229:28–40. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herndon J, Nadeau AM, Davidge-Pitts CJ, et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency due to bilateral infiltrative disease. Endocrine 2018;62:721–8. 10.1007/s12020-018-1737-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lam K-Y, Lo C-Y. Metastatic tumours of the adrenal glands: a 30-year experience in a teaching hospital. Clin Endocrinol 2002;56:95–101. 10.1046/j.0300-0664.2001.01435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Singh D, Kumar L, Sharma A, et al. Adrenal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: four cases and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma 2004;45:789–94. 10.1080/10428190310001615756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huminer D, Garty M, Lapidot M, et al. Lymphoma presenting with adrenal insufficiency. Adrenal enlargement on computed tomographic scanning as a clue to diagnosis. Am J Med 1988;84:169–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wakabayashi M, Sekiguchi Y, Shimada A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma solely involving bilateral adrenal glands and stomach: report of an extremely rare case with review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:8190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gamelin E, Beldent V, Rousselet MC, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting with primary adrenal insufficiency. A disease with an underestimated frequency? Cancer 1992;69:2333–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paling MR, Williamson BR. Adrenal involvement in non-hodgkin lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;141:303–5. 10.2214/ajr.141.2.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nishiuchi T, Imachi H, Fujiwara M, et al. A case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma primary arising in both adrenal glands associated with adrenal failure. Endocrine 2009;35:34–7. 10.1007/s12020-008-9125-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]