Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The progression rate and predictors of anal dysplastic lesions to squamous cell carcinoma of the anus remain unclear. Characterizing these parameters may help refine anal cancer screening guidelines.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the rate of progression of high-grade anal dysplasia to invasive carcinoma in HIV-infected persons.

DESIGN:

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database linked to Medicare claims from 2000–2011, we identified HIV-infected subjects with incident anal intraepithelial neoplasia III. To estimate the rate of progression of anal intraepithelial neoplasia III to invasive cancer, we calculated the cumulative incidence of anal cancer in this cohort. We then fitted Poisson models to evaluate the potential risk factors for incident anal cancer.

SETTINGS:

This is a population-based study.

PATIENTS:

592 HIV-infected subjects with incident anal intraepithelial neoplasia III.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Incident squamous cell carcinoma of the anus.

RESULTS:

Study subjects were largely male (95%) of median age 45.7 years. Within the median follow-up period of 69 months, 33 subjects progressed to anal cancer. The incidence of anal cancer was 1.2% (95% confidence interval: 0.7–2.5%) and 5.7% (95% confidence interval: 4.0–8.1%) at 1 and 5 years, respectively, following anal intraepithelial neoplasia III diagnosis. Risk of progression did not differ by anal intraepithelial neoplasia III treatment status. On unadjusted analysis, Black race (p = 0.02) and history of anogenital condylomata (p = 0.03) were associated with increased risk of anal cancer incidence, whereas prior anal cytology screening was associated with a decreased risk (p = 0.04).

LIMITATIONS:

Identification of some incident cancer episodes employed surrogate measures.

CONCLUSIONS:

In our population-based cohort of HIV-infected subjects with long-term follow-up, the risk of progression from anal intraepithelial neoplasia III to anal squamous cell carcinoma was higher than reported in other studies and was not associated with receipt of anal intraepithelial neoplasia III treatment. See Video Abstract at http://links.lww.com/DCR/Axxx.

Keywords: Anal cancer; Anal dysplasia; Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN); Human papillomavirus (HPV); Incidence; Progression; Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA); Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)

INTRODUCTION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA) is an uncommon cancer with an annual incidence of 1.8 per 100,000 persons.1 Yet the incidence of SCCA is more than 30-fold higher in the HIV-infected population than the general population,2 and up to 80-fold higher among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM).3

Investigation of the natural history of SCCA precursor lesions has helped clarify trends regarding the incidence of this cancer. The classification of these lesions has evolved over time, however. In 2012, the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) Project standardized the nomenclature for HPV-associated squamous lesions of the anogenital tract, recommending a two-tiered system of low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL vs. HSIL).4 Prior to LAST, the three tiered anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) classification was widely used. In that terminology high-grade lesions were classified depending on the thickness of the dysplastic epithelium as either AIN II (when up to two-thirds of the epithelium is involved), or the more advanced AIN III (when two-thirds to the full thickness is dysplastic). Some data sources, such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results cancer registry, continued to use AIN classifications for these lesions, although HSIL is the currently accepted clinical designation for high-grade lesions.

Anal cancer screening programs targeting high-risk populations have been implemented to prevent SCCA by finding and treating HSIL, although the benefits of screening are still controversial.5–10 As SCCA screening has increased, so too have the incidence of HSIL and early stage SCCA.11–13 Little is known about the progression rate and predictors of HSIL to invasive SCCA. Despite a limited understanding of the natural history of high-grade anal dysplasia, these lesions are often managed with high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) guided ablative treatments such as electrocautery.14

Understanding the risk of HSIL progression is critical for proper management, prognostication, and surveillance of patients at highest risk of SCCA. To better characterize the natural history of these premalignant lesions, we used population-based data to estimate the risk of progression of high-grade anal dysplasia (AIN III) to SCCA in HIV-infected subjects. We also examined potential predictors of SCCA incidence in this cohort. These data may help better inform current anal cancer screening guidelines and the management of HSIL.

METHODS

Cohort

The study cohort was assembled from the SEER database linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare). We restricted our cohort to the years 2000–2011 to ensure sufficient follow-up time and so that diagnostic and treatment practices would be consistent with evolving trends in anal cancer screening and the marked increase in SCCA in HIV-infected individuals, and MSM in particular. AIN II cases are not included in SEER, nor is there a registry classification for the broader category of HSIL; therefore we only included AIN III (which does have a distinct SEER code) diagnoses in this analysis.15 Cases of AIN III were identified using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3) site codes C21.0 (Anus, not otherwise specified, excludes skin of anus and perianal skin), C21.1 (Anal canal), C21.2 (Cloacogenic zone) and C21.8 (Overlapping lesion in rectum, anus, and anal canal) with histology code 8077 (Squamous intraepithelial neoplasia, grade III) and behavior code 2 (benign). Cases were excluded from the analysis if subjects had incomplete Medicare part A and part B claims data for the study period, as this would affect the ability to accurately ascertain important exposures and outcomes.

We used a validated algorithm for identifying HIV infection that required either two HIV-related ICD-9 codes separated by at least 30 days in outpatient data, or one inpatient code.16,17 This method maximizes the specificity of this diagnosis, as single codes can represent “rule-out” diagnoses, and has a positive predictive value of 88% in administrative data sources.18 Demographic data (age, sex, race/ethnicity, etc.) were also collected from SEER. Medicare claims data were used to calculate modified Charlson comorbidity scores for subjects using diagnostic codes identified in the 12 months prior to AIN III diagnosis.19 Concomitant anogenital condylomata diagnoses and anal cytologic examinations within two years prior to AIN III diagnosis (hereafter termed “prior anal cytology”) were also collected using claims data.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the incidence of invasive SCCA, detected at least three months after AIN III diagnosis. Incident SCCA was determined from four sources: 1) incident SCCA cases recorded in SEER that followed an initial diagnosis of AIN III; 2) Medicare claims capturing treatment for a diagnosis of invasive SCCA by identifying claims for radiotherapy or chemotherapy combined with diagnostic codes for SCCA; 3) Medicare claims for extensive surgical resection or colostomy placement combined with diagnostic codes for SCCA; and 4) cases of AIN III with SCCA as the cause of death from SEER death data (see Supplemental table 1). We collected data on other outcomes including anal cancer-specific death (from SEER cause of death data), colostomy placement (using Medicare claims), and death from any cause using SEER and Medicare data.

Treatment and Surveillance of AIN 3

Treatment methods for AIN III within 30 days of diagnosis were collected from the SEER database and Medicare claims, specifically surgical (local excision) and non-surgical (thermal ablation, laser tumor destruction, electrocautery, and fulguration). Surveillance of AIN III lesions after diagnosis and treatment (hereafter termed “subsequent anal cytology”) was identified using Medicare claims denoting anal cytology performed at 30 days or more following AIN III diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of baseline characteristics for patients was compared using the t-test for normal continuous variables, the Wilcoxon test for non-normal continuous variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. We used cumulative incidence function methods to determine the incidence of SCCA accounting for death as a competing event, and for estimation of 95% confidence intervals (CI). We then implemented the method proposed by Pepe and Mori to compare cumulative incidence of SCCA by treatment status and subsequent anal cytology.20 In order to identify independent predictors of risk of progression to SCCA by treatment status, we fitted models of SCCA incidence adjusting for sex, age, race, year of AIN 3 diagnosis, HIV infection, history of anogenital condylomata, smoking, prior anal cytology, and treatment of AIN III using poisson regression methods. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The institutional review board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai deemed this research exempt from review.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

Our analytic cohort consisted of 592 HIV-infected subjects who were diagnosed with incident AIN III as reported to the SEER registry. The study sample was predominantly male (95%) of mean age 45.7 years. We identified thirty-three subjects with likely incident SCCA during this time period (Table 1). Compared to AIN 3 subjects without incident SCCA, subjects with incident SCCA over the study period were more likely to be non-Hispanic black (Table 1; 33% vs. 13%, p < 0.01) and to have a history of anogenital condylomata (63% vs. 43%, p = 0.02). Sixty-six percent of subjects without incident SCCA underwent prior anal cytology compared to 48% of subjects with incident SCCA (p = 0.04). There was no statistically significant difference in sex, age, or history of smoking by SCCA incidence status. The burden of comorbidities in the study sample was low, with a mean Charlson comorbidity score of 0.36 and 0.57 in those without and with incident SCCA, respectively (p = 0.2). Median follow up time was approximately 6 years and did not significantly differ between those with and without incident SCCA. Of subjects with incident SCCA, 77% underwent prior surgical or non-surgical treatment of the AIN III lesion, compared to 61% in those subjects without incident SCCA (Table 1; p = 0.07). Subjects without and with incident SCCA underwent subsequent anal cytology (following AIN 3 diagnosis) at rates of 73% and 64%, respectively (p = 0.3).

Table 1.

Cohort subject characteristics.

| Characteristic | AIN 3 cases without incident SCCAb

(n=559) |

AIN 3 cases with incident SCCAb (n=33) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (% male) | 534 (95) | 31 (94) | 0.7 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 47.3 (41.5–52.4) | 44.7 (39.4–50.2) | 0.6 |

| Race, N (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 354 (63) | 18 (55) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 73 (13) | 11 (33) | |

| Hispanic | 52 (9) | <11d | |

| Other | 80 (14) | <11d | |

| Year of AIN 3a diagnosis, N (%) | 0.02 | ||

| 2000–2003 | 108 (19) | <11d | |

| 2004–2007 | 189 (34) | 18 (55) | |

| 2008–2011 | 262 (47) | <11d | |

| Site of AIN 3 diagnosis, N (%) | 0.4 | ||

| Anus, not otherwise specifiedc | 194 (35) | 15 (45) | |

| Anal canal | 360 (64) | 18 (55) | |

| Overlapping lesion of rectum, anus, and anal canal | <11d | <11d | |

| Charlson comorbidity index score, mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.9) | 0.57 (1.1) | 0.2 |

| History of smoking (current or past), N (%) | 99 (18) | <11d | 0.2 |

| History of anogential condylomata, N (%) | 241 (43) | 21 (63) | 0.02 |

| Prior anal cytology,e N (%) | 370 (66) | 16 (48) | 0.04 |

| Subsequent anal cytology,f N (%) | 407 (73) | 21 (64) | 0.3 |

| Treated for AIN 3,g N (%) | 325 (61) | 24 (77) | 0.07 |

| Follow up time, months, median (IQR) | 69 (46–97) | 75 (54–94) | 1.0 |

AIN 3: anal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3

SCCA: squamous cell carcinoma of the anus

Excludes skin of anus and perianal skin

Value suppressed for confidentiality per SEER guidelines

Prior anal cytology: Anal cytology within two years prior to AIN 3 diagnosis

Subsequent anal cytology: anal cytology thirty days or more following AIN 3 diagnosis

Treated for AIN 3: Treated defined as cryosurgery, electrocautery, laser ablation, or local excision within 30 days of AIN 3 diagnosis

Incidence rates of SCCA

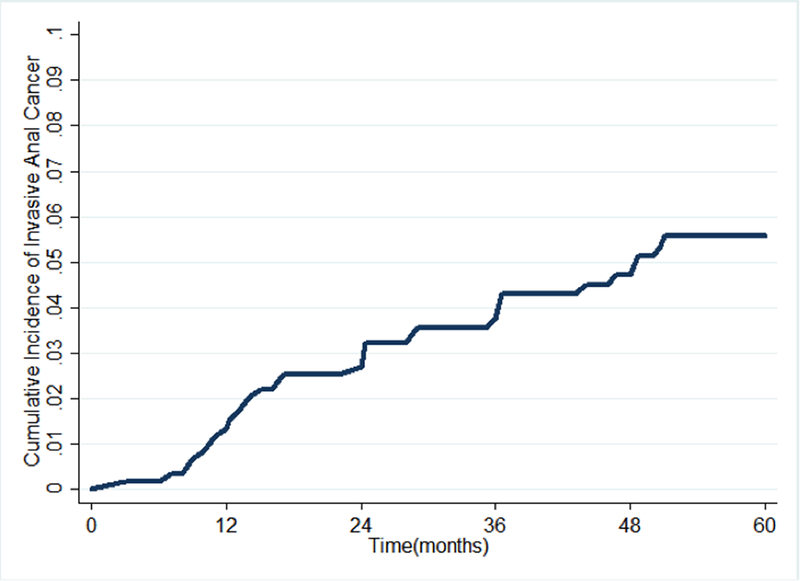

During the study period, we identified 33 incident cases of SCCA among the 592 subjects diagnosed with AIN III at baseline (Table 1). Among the 33 subjects who developed incident SCCA, the median time from AIN III to incidence of SCCA was 24 months (interquartile range 12–40 months). The cumulative incidence of SCCA after AIN 3 diagnosis was 1.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0/7–2.5%) at 12 months, 2.6% (95% CI 1.6–4.3) at 24 months, 3.7% (95% CI 2.4–5.6) at 36 months, and 5.7% (95% CI 4.0–8.1) at 60 months (Table 2 and Figure 1). The cumulative incidence of SCCA did not differ significantly when comparing by AIN III treatment status (results not otherwise shown; p = 0.2) nor by whether patient underwent subsequent anal cytology (p = 0.1).

Table 2.

| Time | Incidence (%) | 95% CIc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months | 1.2 | 0.7–2.5 |

| 24 months | 2.6 | 1.6–4.3 |

| 36 months | 3.7 | 2.4–5.6 |

| 60 months | 5.7 | 4.0–8.1 |

SCCA = squamous cell carcinoma of the anus

AIN 3 = anal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3

CI = confidence interval

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curve for invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected subjects with anal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3.

Predictors of progression to SCCA

Table 3 shows the incidence rate ratios of various predictors of SCCA incidence. In unadjusted analyses, non-Hispanic Black race (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 12.2, 95% CI 1.6–95.4, p = 0.02) and history of anogenital condylomata (IRR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1–4.8, p = 0.03) were associated with increased risk of SCCA incidence. The risk of SCCA was nearly three times greater among non-Hispanic Blacks compared to non-Hispanic Whites. The associations of non-Hispanic Black race and history of anogenital condylomata only trended towards significance on adjusted analysis (p = 0.06 and p =0.07, respectively). In unadjusted analysis, prior anal cytology (preceding AIN 3 diagnosis) was associated with a decreased risk of SCCA incidence (IRR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2–0.96, p = 0.04). This association was not statistically significant after adjustment (p = 0.2). Treatment of AIN 3 was associated with a trend towards increased risk of SCCA incidence, however this was not statistically significant (IRR 1.7, 95% CI 0.7–4.0, p = 0.2).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses of predictors of SCCAa incidence

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRRb (95%CI) | P | IRRb (95%CI) | P | |

| Male sex | 1.5 (0.4–3.3) | 0.6 | 1.9 (0.4–8.5) | 0.4 |

| Age | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.9 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.9 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4.0 (0.5–29.9) | 0.2 | 3.6 (0.5–27.5) | 0.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.2 (1.6–95.4) | 0.02 | 7.5 (0.9–61.3) | 0.06 |

| Hispanic | 4.4 (0.5–42.0) | 0.2 | 4.3 (0.4–42.4) | 0.2 |

| Other | REFf | REFf | ||

| Year of AIN 3a diagnosis | ||||

| 2000–2003 | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.3–2.5) | 0.7 |

| 2005–2007 | 1.7 (0.7–3.9) | 0.2 | 1.4 (0.6–3.3) | 0.5 |

| 2008–2011 | REFf | REFf | ||

| History of anogential condylomata | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) | 0.03 | 2.1 (1.0–4.8) | 0.07 |

| History of smoking (current or past) | 1.9 (0.9–4.1) | 0.1 | 1.3 (0.6–3.0) | 0.6 |

| Prior anal cytologyd | 0.5 (0.2–0.96) | 0.04 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.2 |

| Treated of AIN 3e | 1.7 (0.7–4.0) | 0.2 | 1.0 (0.4–2.6) | 0.9 |

SCCA = squamous cell carcinoma of the anus

IRR = incidence rate ratio

AIN 3: anal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3

Prior anal cytology: Anal cytology within two years prior to AIN 3 diagnosis

Treated for AIN 3: Treated defined as cryosurgery, electrocautery, laser ablation, or local excision within 30 days of AIN 3 diagnosis

REF = Reference group

DISCUSSION

The incidence and predictors of SCCA in patients with HSIL are unclear. Using population-based data with long-term follow-up, we estimate the 5-year risk of AIN III progression to SCCA in HIV-infected patients to be 5.7%. Furthermore, we found no difference in rates of progression to SCCA in patients who received treatment for HSIL compared to those who did not.

To appreciate the limits of comparing this data to that of prior studies, it is important to note the historical context in which SCCA precursor lesions were classified and studied. Estimates of the risk of progression of HSIL to SCCA have varied widely due to significant heterogeneity in diagnostic terminology and criteria used (HSIL, AIN III, and anal carcinoma in situ)4,21; treatment (if any) for such lesions (excision, ablation, or watchful waiting); populations studied (HIV-infected and uninfected, men and women); as well as follow-up time.1,14,22–25 HSIL, the current widely used histological diagnosis for high-grade SCCA precursor lesions, combines anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) grades 2 and 3 since these lesions are associated with significant risk of malignant transformation. Of note, our data were collected prior to the LAST Project, and AIN III is the only SCCA precursor lesion reportable to SEER.

Our study presents data on one of the largest cohorts of HIV-infected subjects with HSIL, with follow-up time exceeding that of most similar studies. We found 5-year cumulative SCCA incidence rates among patients initially diagnosed with AIN III that were similar to other retrospective studies. Previous studies reported cumulative risks of SCCA as 0–1.2% at 1 year14,25 and 1.7–13% at 5 years1,22,23 following diagnosis of the SCCA precursor lesion. However, Goldstone et al. reported a 2% progression rate at 3 years among 727 MSM with high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (HGAIN) treated with ablation, which is roughly half the rate seen in our cohort within the same timeframe.14 Using pooled incidence estimates of anal cancer and prevalence rates of HSIL, Machalek et al. estimated that the theoretical rate of progression of HGAIN to SCCA is 1/377 per year among HIV-infected MSM living in the ART era, equivalent to 0.3% per year and 1.3% at 5 years, and even lower rates for HIV-uninfected patients.26 Several studies have generated progression estimates closer to those seen in our analysis however; Tong et al. estimated progression at approximately 1.2%/year and a state-transition modeling analysis by Mathews et al. determined a range of 1.1–1.7%/year.25,27

The lower rates of progression in some of these studies compared to our results may be explained by differences in treatment of AIN III lesions or methods used to identify progression. Our study identified incidence of SCCA both directly, via reporting to SEER, and indirectly via radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgical treatment for an SCCA diagnosis in patients with previous diagnoses of AIN III. This indirect identification of incident SCCA may overestimate the true incidence due to potential classification errors. Additionally, previous similar studies of SCCA incidence in patients with dysplasia included patients with AIN II diagnoses1,14,25,26 which probably have a lower rate of progression to SCCA than AIN III.21,26 Thus, rates in these studies may not be directly comparable to those in the present study.

On adjusted analysis, we were not able to detect any statistically significant predictors of progression to SCCA. However, on unadjusted analysis, history of anogenital condylomata was associated with increased hazard of progression to SCCA. This is likely due to the increased risk of concomitant anal high-grade dysplasia among patients with anogenital condylomata.28 Similarly, studies have shown that persistent infection with high-risk HPV is an important risk factor for HSIL, and may predict progression of HSIL to SCCA.4 Since SEER-Medicare lacks data on HPV co-testing of AIN III lesions for the time period studied, we could not evaluate oncogenic HPV strains as a potential predictor. Additionally, not all persons who progressed to SCCA had evidence of prior condylomata, which is consistent with prior evidence that high-grade lesions often manifest in patients without overt verrucous lesions.29

With nearly two-thirds of subjects undergoing anal cytology both prior and subsequent to AIN III diagnosis, our study likely represents a cohort of HIV-infected patients undergoing anal cancer screening as well as treatment and surveillance of HSIL. History of anal cytology prior to AIN III diagnosis—a variable that strongly suggests a history of anal cancer screening—was associated with lower risk of progression to SCCA on unadjusted analysis. This result suggests that participation in an anal cancer screening program that can detect and treat HSIL may decrease the risk of progression to SCCA. However, an alternative explanation is that anal cytology may lead to overdiagnosis, identifying less aggressive lesions that are slower to progress.30

Although we did not observe an association between AIN III treatment and lower SCCA incidence, our methods for defining treatment of AIN III may not adequately capture true treatment and surveillance of these lesions. Claims-based data do not provide detailed AIN III management details for our subjects. For instance, we were unable to identify the frequency of ablative or surgical treatments a subject underwent after diagnosis, the location of recurrent dysplastic lesions, extent of the treatment or frequency of follow-up visits to monitor dysplasia resolution or recurrence. These elements of management have been shown to contribute to AIN III recurrence or progression to SCCA, and therefore without these data we are unable to draw detailed conclusions on the effect of AIN III treatment on progression to SCCA.14

Our study has several limitations. Although our sample represents one of the largest AIN III long-term outcomes analyses, for a nationally representative sample it includes a smaller number of cases than might be expected. Medicare enrollment was a requirement for inclusion in the analysis (studies of AIN III in SEER without Medicare linkage have demonstrated significantly more cases),15 and the younger age of the US HIV-infected cohort partially explains the limited number of cases. Also, as AIN III is not an invasive cancer, it is possible that it is less consistently reported by cancer registrars. Another limitation was that our methods captured incident SCCA in part by identifying relevant cancer treatments using Medicare claims. Miscoding and misclassification associated with these claims may have led to incorrect identification of incident cancers, although we utilized a conservative approach that had been established in previous publications.31–33 We also identified some cases using cause of death data; for this method it is possible that SCCA incidence preceded the AIN III diagnosis, thereby overestimating cancer risk. Furthermore, SEER-Medicare does not contain clinical data on HIV-infected patients, and therefore we had no ability to account for HIV disease and immune status in our analysis. Lastly, there was likely heterogeneity in the types of treatments for AIN III administered to the patients in this study. Nevertheless, our study has significant strengths including the use of nationally-representative, population-based data. It is on of the largest studies with the most extensive follow-up to date reporting incidence rates of SCCA in a population registry of HIV-infected subjects with high-grade anal dysplasia.

Characterization of the risk of invasive anal cancer is important for counseling patients on the risk of malignancy and benefits of treating precancerous lesions. Further, knowledge of such risks allows for more informed decisions when refining anal cancer screening programs.5,8,10 Our population-based study suggests that the rate of progression of AIN III to SCCA is higher than that reported in some previous studies. Randomized controlled studies assessing the impact of screening and treatment of high-grade anal dysplasia are currently underway and will further inform the management of anal dysplasia among high-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07CA180782 to KS) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K08AI120806 to THS).

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Goldstone reports grants and personal fees from Merck and Co, grants personal fees and non-financial support from Medtronic Inc., outside of the scope of the submitted work. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the International Anal Neoplasia Society Meeting November 11–13, 2016

REFERENCES

- 1.Cachay E, Agmas W, Mathews C. Five-year cumulative incidence of invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected patients according to baseline anal cytology results: an inception cohort analysis. HIV Med. 2015;16:191–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeken JF, Tjen-A-Looi A, Rudek MA, et al. The rising challenge of non-AIDS-defining cancers in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1228–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, et al. ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1026–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. ; Members of LAST Project Work Groups. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for hpv-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiao EY, Giordano TP, Palefsky JM, Tyring S, El Serag H. Screening HIV-infected individuals for anal cancer precursor lesions: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the natural history of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and anal human papillomavirus infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28:422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaisa M, Ita-Nagy F, Sigel K, et al. High rates of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected women who do not meet screening guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czoski-Murray C, Karnon J, Jones R, Smith K, Kinghorn G. Cost-effectiveness of screening high-risk HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) and HIV-positive women for anal cancer. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:(53)iii-iv, ix-x, 1–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiao EY, Krown SE, Stier EA, Schrag D. A population-based analysis of temporal trends in the incidence of squamous anal canal cancer in relation to the HIV epidemic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldie SJ, Kuntz KM, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA, Welton ML, Palefsky JM. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in homosexual and bisexual HIV-positive men. JAMA. 1999;281:1822–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson RA, Levine AM, Bernstein L, Smith DD, Lai LL. Changing patterns of anal canal carcinoma in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1569–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amirian ES, Fickey PA Jr, Scheurer ME, Chiao EY. Anal cancer incidence and survival: comparing the greater San-Francisco bay area to other SEER cancer registries. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiels MS, Kreimer AR, Coghill AE, Darragh TM, Devesa SS. Anal cancer incidence in the United States, 1977–2011: distinct patterns by histology and behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1548–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstone SE, Johnstone AA, Moshier EL. Long-term outcome of ablation of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: recurrence and incidence of cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simard EP, Watson M, Saraiya M, Clarke CA, Palefsky JM, Jemal A. Trends in the occurrence of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in San Francisco: 2000–2009. Cancer. 2013;119:3539–3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasciano NJ, Cherlow AL, Turner BJ, Thornton CV. Profile of Medicare beneficiaries with AIDS: application of an AIDS casefinding algorithm. Health Care Financ Rev. 1998;19:19–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Harlan LC, Warren JL. Data sources for measuring comorbidity: a comparison of hospital records and medicare claims for cancer patients. Med Care. 2006;44:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, et al. Development and verification of a “virtual” cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006;44(suppl 2):S25–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepe MS, Mori M. Kaplan-Meier, marginal or conditional probability curves in summarizing competing risks failure time data? Stat Med. 1993;12:737–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longacre TA, Kong CS, Welton ML. Diagnostic problems in anal pathology. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholefield JH, Castle MT, Watson NF. Malignant transformation of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson AJ, Smith BB, Whitehead MR, Sykes PH, Frizelle FA. Malignant progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:715–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry JM, Jay N, Cranston RD, et al. Progression of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong WW, Jin F, McHugh LC, et al. Progression to and spontaneous regression of high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected and uninfected men. AIDS. 2013;27:2233–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathews WC, Agmas W, Cachay ER, Cosman BC, Jackson C. Natural history of anal dysplasia in an HIV-infected clinical care cohort: estimates using multi-state Markov modeling. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramowitz L, Benabderrahmane D, Ravaud P, et al. Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and condyloma in HIV-infected heterosexual men, homosexual men and women: prevalence and associated factors. AIDS. 2007;21:1457–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaisa M, Sigel K, Hand J, Goldstone S. High rates of anal dysplasia in HIV-infected men who have sex with men, women, and heterosexual men. AIDS. 2014;28:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srokowski TP, Fang S, Duan Z, et al. Completion of adjuvant radiation therapy among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith BD, Haffty BG, Buchholz TA, et al. Effectiveness of radiation therapy in older women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1302–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chamie K, Litwin MS, Bassett JC, et al. ; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Recurrence of high-risk bladder cancer: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2013;119:3219–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.