Abstract

Despite the high prevalence and negative impact of psychiatric comorbidities on the life of adults with epilepsy, significant unmet mental health care need exists due to a variety of factors, including poor access to mental health care providers. A potential solution to address access barriers is neurologist-driven diagnosis and management of common psychiatric conditions in epilepsy, of which mood and anxiety disorders are the most common. In this manuscript, patient selection criteria and practical treatment strategies are outlined for common mood and anxiety disorders that can be safely managed by neurologists.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, epilepsy, neurologist, treatment, psychiatric comorbidity

Introduction: Barriers to psychiatry/mental health access

Despite increased recognition that psychiatric comorbidities in adults with epilepsy are highly prevalent and important, unmet mental health care need is substantial, outnumbering physical health need 2:1 in a recent systematic review[1]. Although 84% of individuals with psychological distress and epilepsy in the California Health Interview Survey perceived a need for mental health care, only 57% had seen a mental health provider, and 30% reported delays in mental health treatment [2]. A needs-assessment conducted in South Carolina demonstrated that more than 50% of individuals experienced difficulty finding behavioral or mental health services [3]. Not only do patients perceive unmet need for treatment of psychiatric symptoms, but epileptologists do as well. Epileptologists who responded to the American Epilepsy Society Q-PULSE survey on screening for anxiety and depression in epilepsy indicated the two top barriers to screening were inadequate availability of local psychiatrists and inadequate availability of counseling/psychotherapy services (55.4% and 53.5% of respondents)[4].

Why do these gaps and barriers to mental health care exist? Multiple factors contribute, including insurance related factors, an overall shortage of mental health providers, reluctance of patients to seek psychiatric care because of stigma of mental illness , limited communication between psychiatrists and neurologists, limited education of psychiatrists on neurological illness and limited education of neurologists on psychiatric illness[2–7]. Ultimately, the result of this conundrum is that even when mental illness is recognized, it is undertreated in persons with epilepsy. An intuitive solution may be to have neurologists provide mental health care concomitant with epilepsy care.

A. Non-psychiatrists can provide safe treatment

Studies done in primary care populations have demonstrated that non-psychiatrists can manage anxiety and depression safely and effectively, particularly with the use of validated screening instruments [8, 9]. For example, in the STAR*D study, individuals with depression were treated with citalopram aided by symptom measurement every two weeks in multiple primary care and psychiatry practices. Outcomes did not differ among individuals treated in primary care settings compared to psychiatry settings. Specifically, remission measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was 26.6% in primary care and 28% in psychiatry settings; response rates were 46% in primary care and 48% in psychiatry settings, measured by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Self-Report (QIDS-SR)[8]. Zupancic et al. demonstrated in a primary care clinic that using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Self-Report instruments for anxiety and depression more than doubled treatment rates for these conditions [9]. Treatment of common psychiatric comorbidities by neurologists thus is likely feasible and could address some of the barriers to accessing mental health care.

A.1. Common psychiatric comorbidities that neurologists can identify and treat in the clinic: Diagnostic criteria

Major depressive episodes/disorder

A major depressive episode is defined as at least two weeks of impairing symptoms most of the day, nearly every day, including 5 of the 9 symptoms outlined below [10]. These include: 1) depressed mood, 2) markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities, 3) decreased or increased appetite, or significant weight loss or gain when not dieting, 4) insomnia or hypersomnia, 5) psychomotor agitation or retardation, 6) fatigue or loss of energy, 7) feelings of worthlessness or excessive inappropriate guilt, 8) diminished concentration/thinking or indecisiveness, and 9) recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation [10]. At least one of the symptoms must be depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in activities [10].

Dysthymia

Dysthymia is the presence of depressed mood most of the day for most days lasting at least two years, along with two of the following 6 additional features: 1) poor appetite or overeating, 2) insomnia or hypersomnia, 3) low energy or fatigue, 4) low self-esteem, 5) poor concentration or difficulty making decisions, and 6) hopelessness [10]. The symptoms must cause distress or impairment, must not have resolved for more than 2 months consecutively during the 2 year period [10].

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by at least 6 months of excessive, difficult to control anxiety and worry on most days, causing impairment or distress, along with 3 of 6 additional features [10]. These include: 1) restlessness, or feeling keyed up/on edge, 2) easy fatigue, 3) difficulty concentrating or mind going blank, 4) irritability, 5) muscle tension, and 6) sleep disturbance [10].

Panic disorder

Recurrent, unexpected panic attacks followed by at least one month of significant worry about attacks, and/or resulting maladaptive behavior define panic disorder [10]. A panic attack is a surge of intense fear or discomfort peaking within minutes, and involving at least 4 of the following symptoms: 1) palpitations or increased heart rate, 2) sweating, 3) trembling or shaking, 4) shortness of breath or smothering sensation, 5) choking sensation, 6) chest discomfort/pain, 7) nausea or abdominal distress, 8) dizziness, unsteadiness, lightheadedness, 9) chills or heat sensation, 10) paresthesias, 11) feeling of unreality or being detached from self, 12) fear of losing control, and 13) fear of dying [10]. Distinguishing between panic attacks and focal seizures with ictal fear/panic is important for patient management, and this can be complex due to occasional coexistence of panic attacks and focal seizures with ictal fear [11]. Features most consistent with panic attack include longer duration than seizures (5–10 minutes for panic attack vs. less than 2 minutes for seizure), initiation from wakefulness and not out of sleep (in contrast to focal seizures which may directly arise from sleep), and lack of features commonly seen in focal seizures such as automatisms, déjà vu, or hallucinations [12, 13].

B. Management of common psychiatric comorbidities: Practical suggestions

B.1. Type of anxiety and depression symptoms: temporal relation to seizures and iatrogenic symptoms

To appropriately manage anxiety and depression in persons with epilepsy, it is important to first identify the type of psychiatric symptoms at hand: a) are the symptoms temporally related to seizure occurrence (peri-ictal), seizure treatment (iatrogenic, following pharmacologic with antiepileptic drugs (AED) and /or surgical treatment), or unrelated to seizures or seizure treatment (interictal). Each of these types of symptoms has a distinct treatment approach.

Peri-ictal psychiatric symptoms can be either preictal (occurring one to three days before a seizure), ictal (a psychiatric symptom that is part of the seizure semiology, such as ictal fear), or postictal (occurring after a seizure or cluster of seizures, typically starting within three days after the seizure or seizure cluster). The management of peri-ictal psychiatric symptoms focuses on prevention by achievement of seizure control. Postictal anxiety and depression typically do not respond well to treatment with antidepressant/anxiolytic drugs, but postictal psychosis may be effectively treated with antipsychotic medications such as risperidone [14–16].

The development of iatrogenic adverse events of pharmacologic and surgical treatment of epilepsy has been identified in patients with a current, past, and/or family history of psychiatric disorders [17, 18]. Iatrogenic symptoms / episodes of anxiety and depression related to pharmacologic treatment may include a) the addition of an AED with potential negative psychotropic properties (barbiturates, felbamate, levetiracetam, topiramate, zonisamide, vigabatrin, clobazam, brivaracetam and perampanel); b) withdrawal of an AED with mood stabilizing (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid and lamotrigine) or anxiolytic properties (benzodiazepines, gabapentin, pregabalin, valproic acid), or c) reduced levels of ongoing psychotropic drugs caused by the addition of an enzyme-inducing AED (e.g., addition of phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, primidone, rufinamide to ongoing fluoxetine treatment). To prevent iatrogenic psychiatric symptoms, it is essential to identify individuals at risk: those with prior, current, or family history of psychiatric disorders.

Interictal psychiatric symptoms/ episodes occur independently of seizure occurrence. Nonetheless, peri-ictal symptoms may occur in patients with interictal symptoms (e.g., patients with ictal fear have an increased risk of having interictal panic disorder) and iatrogenic symptoms may at times occur in patients with interictal and peri-ictal symptoms. A careful history can properly identify the nature of the different types of symptoms in the same patient. Diagnostic and treatment approaches, as outlined in the sections below, are similar to approaches used for people without epilepsy.

B.2. Interictal mood and anxiety disorders

Fortunately for neurologists, some simple screening strategies and treatment principles can be employed to tackle psychiatric comorbidities with a practical approach, thus enabling competent neurologists to manage interictal depression and/or anxiety in epilepsy in addition to peri-ictal and iatrogenic symptoms as described above. An approach is composed of two freely available, validated screening instruments and simple dosing guidelines for medication therapies advantageous for use in epilepsy and efficacious for interictal major depression, dysthymia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety.

B.2.1. Identification

In the setting of a busy outpatient clinic, self-rating screening instruments can be used to identify the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety [17–21]. Of note, these instruments were developed and validated in patients with a minimum reading level of fourth grade. Therefore, they should not be used in patients with cognitive impairment. One instrument, the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) was developed to identify a possible major depressive episode (MDE) in patients with epilepsy, with scores >15 demonstrating good sensitivity and specificity for major depression [19, 20]. Scores of 15 or lower on the NDDI-E are of uncertain significance, though there is some data suggesting that scores in the 14–15 range may detect clinically relevant symptoms [19]. An alternative rating scale to identify symptoms of depression is the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II)[21]. Patients who do not meet diagnostic criteria for MDE but endorse symptoms on the BDI-II may be considered to suffer from a form of sub-syndromic depression. It is important to remember that these instruments do not establish a definitive diagnosis. Therefore, specific symptom items should be addressed in the clinical visit and expanded upon as appropriate.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorders-7 (GAD-7) is a reliable self-rating instrument used to identify symptoms of anxiety. Scores of 10 or higher have acceptable sensitivity and specificity for detecting a broad range of anxiety disorders in primary care, including 89% sensitivity and 82% specificity for generalized anxiety disorder and 74% sensitivity and 81% specificity for panic disorder[22]. Alternatively, some authors have suggested using a cutpoint of >10 for significant anxiety symptoms in epilepsy [23].

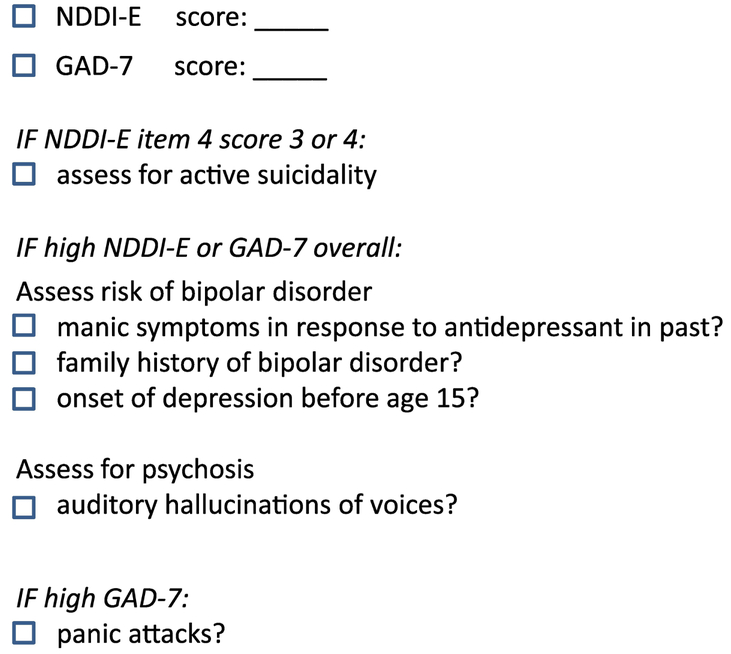

To identify clinically significant mood and/or anxiety symptoms, we recommend the use of the NDDI-E and GAD-7, which take less than 5 minutes to complete. If symptoms of depression are identified based on the NDDI-E cutpoints outlined above, we suggest asking follow-up questions for all items scored as “sometimes” or “always or often,” especially item 4 (“I’d be better off dead”), which is a validated suicide screen for those responses [24]. Among individuals with high NDDI-E scores, we also recommend asking additional questions to assess for past manic episode which would suggest bipolar disorder, and to assess for psychotic symptoms or suicidality any of which would necessitate prompt psychiatry referral (see Figure 1 for suggested items/checklist). If anxiety symptoms are identified based on the GAD-7, we suggest a follow up question to assess whether the patient has panic attacks. The use of self-rating instruments is reviewed in great detail in the article by Bermeo-Ovalle in this issue.

Figure 1:

Checklist for assessing mood and anxiety

Of note, MDE can be the expression as well of a bipolar disorder, a more severe form of mood disorder which should not be managed by a neurologist. A bipolar disorder should be suspected under the following conditions: a) a positive family history of bipolar illness established by the identification of manic and /or hypomanic episodes; b) a first MDE at the time of adolescence, as these patients have a 50% risk of having a bipolar disorder; c) the development of manic and /or hypomanic symptoms associated with the use of antidepressant drugs.

C. Pharmacologic Treatment

Fortunately, the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders described in section B can follow the same strategies used for the treatment of primary mood and anxiety disorders, based on the use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotoninnorepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) [17]. The following principles should be considered: a) An SSRI should be considered in patients with an MDE and /or anxiety disorder and /or symptoms of depression and /or anxiety as suggested in table 1. b) An SNRI should be considered first in MDE associated with symptoms of fatigue and excessive sleepiness and /or if a previous trial with an SSRI was ineffective at optimal doses. c) The trial with an SSRI or SNRI should aim to achieve complete symptom remission. If symptoms persist at maximal doses and /or adverse events develop, a trial with an antidepressant of the alternate family should be considered. d) To ensure that optimal doses have been achieved, dose increments of up to 30% in certain SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram) and SNRIs (duloxetine) may be necessary in the presence of enzyme-inducing AEDs. e) Patients need to be monitored for potential pharmacodynamic interactions between SSRIs, SNRIs and some AEDs (e.g., hyponatremia, bruising, osteopenia and osteoporosis). Escitalopram and citalopram have low pharmacokinetic interaction with AEDs and are useful for depression, generalized anxiety and panic [17]. Sertraline has a similar efficacy/common use in anxiety and depressive disorders, though with slight potential for inhibition of the metabolism of some AEDs via the CYP2D6 enzymes [17]. Dosing of these three advantageous drugs for use in epilepsy is outlined in Table 1. A more comprehensive list of SSRI and SNRI medications with FDA approved indications is outlined in Table 2, along with potential for inhibition of antiseizure drugs [13, 17]. Response to treatment can be monitored by repeated assessment with the GAD-7 and NDDI-E and /or BDI-II on follow-up visits [17].

Table 1:

Dosing of advantageous medications to treat anxiety and depression in epilepsy

| Drug | Starting dose (mg daily) | Maximal dose (mg daily) | Potential schedule for dose increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| escitalopram | 5–10 | 20 | 5–10mg biweekly |

| citalopram | 10 | 60 | 10–20mg biweekly |

| sertraline | 25–50 | 200 | 25–50mg biweekly |

Table 2:

FDA-approved indications of selected SSRI/SNRIs, potential for inhibition of antiseizure drugs

| Drug | Depression | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Panic Disorder | Inhibition of CYP enzymes with potential to affect antiseizure drugs? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||||

| Citalopram | + | Lowest potential | ||

| Escitalopram | + | + | Lowest potential | |

| Fluoxetine | + | + | Moderate inhibitor | |

| Fluvoxamine | Maximal inhibitor | |||

| Paroxetine | + | + | + | Moderate inhibitor |

| Sertraline | + | + | Mild inhibitor | |

| SNRIs | ||||

| Desvenlafaxine | + | Likely low potential | ||

| Duloxetine | + | + | Likely low potential | |

| Milnacipran | Likely low potential | |||

| Venlafaxine | + | + | + | Likely low potential |

| Vortioxetine | + | Likely low potential | ||

C.2. When to refer to psychiatry

Management by a psychiatrist rather than a neurologist is appropriate if psychotic symptoms such as delusional thinking, auditory hallucinations, risk factors for bipolar disorder, current history of alcohol and drug abuse or suicidality are identified at the time of initial screening as outlined in Figure 1 [24, 25]. In addition, patients with personality disorders should be referred to the care of a psychiatrist.

If symptoms fail to remit after two trials, one with an SSRI and one with an SNRI, then referral to psychiatry should be considered [7].

C. Clinical Strategies

Pitfalls to avoid:

Non-psychiatrists often make two main mistakes when treating depression. The first is underappreciating the role that therapeutic efforts or support from family or social contacts can offer. In many ways, outcomes are related to engagement with others. Persons who are isolated may have little opportunity to socialize and that leads to independent problems in the depressive or anxiety realms. Furthermore, identification of depressive symptoms may be difficult even with validated rating scales. If an opportunity exists to collect corroborating information from family members or other supports, it can be invaluable to verify clinical impressions and also assess improvement. Engagement with family or supportive individuals is essential to accurately assess treatment approaches, even for seasoned psychiatrists.

The second mistake is in being overly aggressive with medication usage. Many clinicians are tempted to take a formulaic approach to antidepressants. An algorithmic, deliberate approach is consistent with the heuristic methods of treatment in primary care and in neurology. However, it may not be useful in psychiatry. Psychiatry is fraught with ambiguity and uncertainty regarding symptom definition and progression. Treatment approaches vary and little evidence exists for selecting one medication over another. Individual variability is the rule and thus rigid approaches may not be effective for most patients. Very gradual adjustments and frequent follow up is the most reasonable approach. Frequent reassessment of the dosing schedule is important. Starting at a low dosage is usually the best initial step. A possible algorithm for treatment is listed in Table 3.

Table 3:

Potential algorithm for treatment of depression or anxiety in the context of epilepsy

|

D. Conclusions

Simple strategies involving brief self-report instruments and prescribing SSRIs can empower neurologists to treat anxiety and depression in adults with epilepsy. Adoption of these management strategies may have a significant positive impact on patients, resulting in fewer delays to treatment among those likely to respond to a simple pharmacotherapy approach.

Highlights.

Adults with epilepsy face substantial barriers to mental health care access.

Validated screeners can assist non-psychiatrists to manage anxiety and depression.

Simple treatment strategies with SSRIs can be employed by adult neurologists.

Acknowledgements/Funding/Disclosures:

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health: NCATS UL1 TR001420 (Heidi Munger Clary; Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute Scholar Academy).

Study sponsor entities had no direct role in manuscript preparation or decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- [1].Mahendran M, Speechley KN, Widjaja E. Systematic review of unmet healthcare needs in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2017;75: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thompson AW, Kobau R, Park R, Grant D. Epilepsy care and mental health care for people with epilepsy: California Health Interview Survey, 2005. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9: E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wagner JL, Brooks B, Smith G, St Marie K, Kellermann TS, Wilson D, Wannamaker B, Selassie A. Determining patient needs: A partnership with South Carolina Advocates for Epilepsy (SAFE). Epilepsy Behav 2015;51: 294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bermeo-Ovalle A Psychiatric Comorbidities in Epilepsy: We Learned to Recognize Them; It Is Time to Start Treating Them. Epilepsy Currents 2016;16: 270–272. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thurman DJ, Kobau R, Luo YH, Helmers SL, Zack MM. Health-care access among adults with epilepsy: The U.S. National Health Interview Survey, 2010 and 2013. Epilepsy Behav 2016;55: 184–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wagner JL, Ferguson PL, Kellermann T, Smith G, Brooks B. Behavioral health referrals in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2016;127: 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kanner AM. Is it time to train neurologists in the management of mood and anxiety disorders? Epilepsy Behav 2014;34: 139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163: 28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zupancic M, Yu S, Kandukuri R, Singh S, Tumyan A. Practice-based learning and systems-based practice: detection and treatment monitoring of generalized anxiety and depression in primary care. J Grad Med Educ 2010;2: 474–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mintzer S, Lopez F. Comorbidity of ictal fear and panic disorder. Epilepsy Behav 2002;3: 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Beyenburg S, Mitchell AJ, Schmidt D, Elger CE, Reuber M. Anxiety in patients with epilepsy: systematic review and suggestions for clinical management. Epilepsy Behav 2005;7: 161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Munger Clary H Anxiety and Epilepsy: What Neurologists and Epileptologists Should Know. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 2014;14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kanner AM, Rivas-Grajales AM. Psychosis of epilepsy: a multifaceted neuropsychiatric disorder. CNS Spectr 2016;21: 247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kanner AM, Soto A, Gross-Kanner H. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of postictal psychiatric symptoms in partial epilepsy. Neurology 2004;62: 708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kanner AM. The treatment of depressive disorders in epilepsy: what all neurologists should know. Epilepsia 2013;54 Suppl 1: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kanner AM. Management of psychiatric and neurological comorbidities in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2016;12: 106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mula M Treatment of anxiety disorders in epilepsy: an evidence-based approach. Epilepsia 2013;54 Suppl 1: 13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gill SJ, Lukmanji S, Fiest KM, Patten SB, Wiebe S, Jette N. Depression screening tools in persons with epilepsy: A systematic review of validated tools. Epilepsia 2017;58: 695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56: 893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146: 317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kanner AM. Anxiety disorders in epilepsy: the forgotten psychiatric comorbidity. Epilepsy Curr 2011;11: 90–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barry JJ, Ettinger AB, Friel P, Gilliam FG, Harden CL, Hermann B, Kanner AM, Caplan R, Plioplys S, Salpekar J, Dunn D, Austin J, Jones J. Consensus statement: the evaluation and treatment of people with epilepsy and affective disorders. Epilepsy Behav 2008;13 Suppl 1: S1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mula M, McGonigal A, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, May TW, Labudda K, Brandt C. Validation of rapid suicidality screening in epilepsy using the NDDIE. Epilepsia 2016;57: 949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]