Abstract

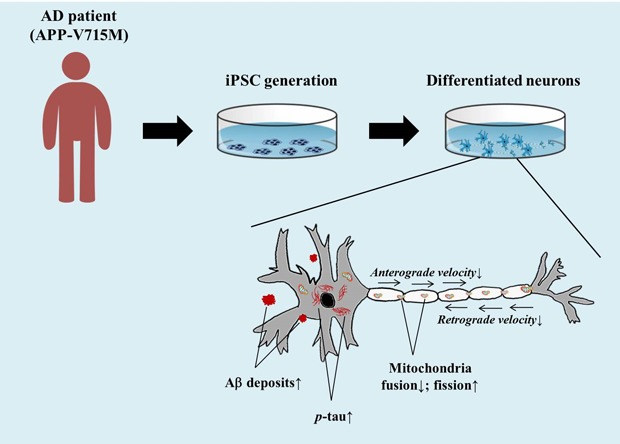

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, which is pathologically defined by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and hyper-phosphorylated tau aggregates in the brain. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also a prominent feature in AD, and the extracellular Aβ and phosphorylated tau result in the impaired mitochondrial dynamics. In this study, we generated an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line from an AD patient with amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutation (Val715Met; APP-V715M) for the first time. We demonstrated that both extracellular and intracellular levels of Aβ were dramatically increased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. Furthermore, the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons exhibited high expression levels of phosphorylated tau (AT8), which was also detected in the soma and neurites by immunocytochemistry. We next investigated mitochondrial dynamics in the iPSC-derived neurons using Mito-tracker, which showed a significant decrease of anterograde and retrograde velocity in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. We also found that as the Aβ and tau pathology accumulates, fusion-related protein Mfn1 was decreased, whereas fission-related protein DRP1 was increased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, compared with the control group. Taken together, we established the first iPSC line derived from an AD patient carrying APP-V715M mutation and showed that this iPSC-derived neurons exhibited typical AD pathological features, including a distinct mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, iPSC, APP, Amyloid beta, Mitochondrial dysfunction

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, and AD patients exhibit loss of memory that impairs their ability to learn or carry out daily tasks. Pathologically, AD can be characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and hyper-phosphorylated tau aggregates which causes neuronal loss in the brain [1,2]. AD can be divided into sporadic and autosomal-dominant familial forms. The latter form is rare, but very tragic, given its 100% penetrance to the family members who have the causative mutations. The autosomal-dominant form of AD is associated with mutations in amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PS1), or presenilin-2 (PS2) [3]. It has been demonstrated that the APP C-terminal mutations including APP (V715M) exhibited increased Aβ42 secretion in primary neurons [4,5]. The APP (Val715Met; APP-V715M) mutation was detected in Korea and the patient showed typical clinical symptoms [6]. In this study, we generated an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line from an AD patient with APP-V715M mutation for the first time. We characterized the phenotypes of APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, including extracellular and intracellular levels of Aβ and high expression levels of phosphorylated tau, compared with the elderly normal control iPSC line which has been fully characterized in our previous study [7]. We investigated the mitochondrial dynamics and the expression of fission and fusion-related proteins in the iPSC-derived neurons. APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons exhibited decrease of mitochondrial velocity and impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion, indicative of extracellular Aβ or phosphorylated tau-induced impairment of mitochondrial dynamics [8,9,10,11]. Taken together, we established an iPSC line, for the first time, from a middle-aged AD patient with an APP-V715M mutation, which recapitulats the cardinal features of AD pathophysiology, which will be potentially useful to develop biomarkers associated with disease progression and responses to the disease-modifying therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enrollment of participants

The patient met the criteria for AD as recommended by the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association, and the normal elderly subject fulfilled the criteria of a normal elderly control as defined by Christensen, et al [12,13]. We performed detailed neuropsychological tests, MRI, [18F]-Florbetaben amyloid PET, and blood draw for iPSC generation from each participant. The institutional review board of the Samsung Medical Center, Asan Medical Center, and CHA University approved the study protocol, and informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Characterization and differentiation of iPSCs

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated freshly from the peripheral blood of the APP-V715M patient using the Ficoll-Paque™ PLUS method (GE Healthcare, USA) [7]. Isolated peripheral-derived MNCs (PBMCs) were infected with SeVdp (KOSM) 302L [14]. Genotyping of the APP-V715M single nucleotide mutation was performed by DNA sequencing (Cosmo Genetech, Korea). The APP gene was amplified by PCR using the following primers (forward primer: TTC AAG GTG TTC TTT GCA GA; reverse primer: CAT AGT CTT AAT TCC CAC TTG G). For teratoma formation, undifferentiated iPSCs were harvested and subcutaneously transplanted into NOG mice. Teratomas were dissected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 8 to 16 weeks after injection. Paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned and stained with hematoxylin/eosin to detect the formation of three-germ layer tissue morphology. Karyotyping, Sendai virus detection PCR, in vitro and cortical differentiation were performed as we described before [7,14].

Extracellular and intracellular amyloid-β ELISA

Extracellular Aβ levels were measured using conditioned media (CM), which were collected from cultured neuronal cells (1×105) at 48 hours after the last medium change from 8 and 10 weeks of differentiation. Intracellular Aβ42 and Aβ40 were measured in a total of 1µg proteins from 10 week-differentiated neurons. All procedures were essentially same as described before [7].

Immunocytochemistry and Western blot

Immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis were performed as described before [7]. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-OCT4 (1:200, Santa Cruz), anti-SOX2 (1:200, Millipore), anti-NANOG (1:200, R&D Systems), anti-SSEA-4 (1:100, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), anti-TRA-1-81 (1:100, Chemicon), Tuj1 anti-tubulin beta III isoform (1:200, Millipore), anti-SMA (1:100, DAKO); anti-AFP (1:100, DAKO), Aβ42 anti-Aβ42 (1:500, Calbiochem), AT8 anti-p-tau (1:1000, Thermo-Fisher), Tau5 anti-tau (1:1000, Thermo-Fisher), anti-Mfn1 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-Mfn2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-Drp1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling), anti-Fis1 (1:1000, Santa Cruz), anti-β-amyloid 6E10 (1:400, BioLegend) and anti-β-actin (1:10000, Santa Cruz) .

Live cell imaging and mitochondrial dynamics analysis

Living cells were imaged using Leica TCSSP5II confocal microscopy. Ten week-differentiated neurons were incubated with Mito-tracker red (Thermo-Fisher Cat.M7512) for 15 min before live cell imaging (LCI) analysis. Cells were maintained at 37℃ and were supplied with atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air (Live Cell Instrument, Seoul, Korea) during imaging. Time-lapse image recording were acquired in 2 sec interval and duration up to 4 min 30 sec. Mitochondria kymographs were analyzed using KymographClear, an ImageJ macro toolset that allows for the generation of kymographs from image sequences. Quantitative analysis of mitochondria velocity was performed using KymographDirect, a stand-alone tool to extract quantitative information from kymographs in an automated way with high accuracy and reliability [15].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the Fisher's LSD (Least Significant Difference) in the Statistical Analysis System (Enterprise 4.1, SAS Korea, Seoul, Korea). Significance was accepted at the 95% probability level. Data in graphs were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (i.e., p value) in the graphs were presented as follows: p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Clinical features of the patient

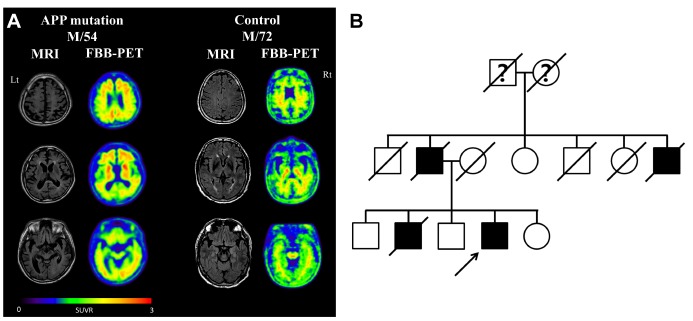

This study is based on a 54 year-old man with an APP mutation (Exon17; c.2143G>A; p.V715M) who visited the memory disorder clinic of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea). The patient developed symptoms at the age of 49, starting with memory impairment and attention deficits. He subsequently developed an impairment in daily activities at the age of 52. Neurological examination revealed a generalized cognitive impairment with the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score of 10. Treatments with cholinesterase inhibitor and NMDA receptor antagonist had limited effects. By the age of 54, the patient developed bradykinesia and rigidity, and no longer understood verbal commands. MRI taken at the age of 54 showed a generalized cortical atrophy, and the 18F-Florbetaben amyloid PET showed a significant amyloid accumulation in the bilateral striatum and association cortices (Fig. 1A). The patient had a strong family history of dementia with an autosomal dominant pattern (Fig. 1B). A 72 year-old healthy man with normal cognition was enrolled for the study. He showed no brain atrophy on brain MRI and no significant amyloid accumulation on amyloid PET (Fig. 1A). Informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Fig. 1. Brain images and the pedigree of the AD patient with APP-V715M mutation. (A) Left: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR images showing the generalized cortical atrophy, including medical temporal lobes in the patient with APP mutation. 18F-Florbetaben (FBB) amyloid PET images showed increased amyloid uptakes in the cerebral cortices and the bilateral striatum in the patient. Right: Control subject showing normal brain MRI findings without cortical atrophy and non-specific subcortical amyloid uptakes, which is normal in elderly subjects. Standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was measured using cerebellar grey matter as the reference region. (B) Pedigree of the APP-V715M family. Autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance was observed on the patient marked with an arrow.

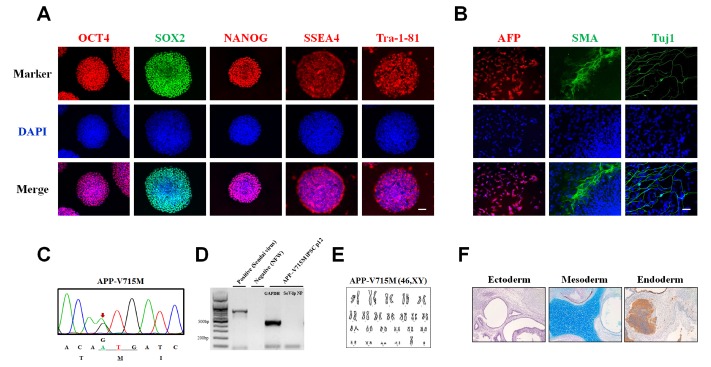

To investigate the pathological features of the patient with APP-V715M mutation, we generated an iPSC line from an AD patient carrying the APP-V715M mutation using the technology that we developed for iPSC generation [7]. The APP patient-derived MNCs were reprogrammed using Sendai virus vector (SeVdp) which expresses four reprogramming factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, cMYC, and KLF4) [7,14]. For iPSC generation, we picked more than three individual clones and selected the best growing clone for further analyses. iPSC lines harboring the APP-V715M mutation exhibited the typical expression of pluripotent stem cell markers, including OCT4, SOX2, SSEA4 and TRA-1-81 (Fig. 2A). Differentiation potential of iPSC lines was assessed using in vitro embryoid body formation and in vivo teratoma assays, based on the three-germ layer marker expression (Fig. 2B and 2F). Genotyping of the established iPSC line was confirmed by a conventional sequencing method (Fig. 2C). No SeVdp vector was integrated in the established iPSC line (Fig. 2D) and its karyotype was normal (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Generation of an iPSC line from an AD patient harboring the APP-V715M mutation. (A) Established iPSC lines from the APP-V715M patient showing the expression of pluripotent stem cell markers, including OCT4 (red), SOX2 (green), SSEA4 (red) and TRA-1-81 (red). (B) Immunocytochemistry showing the potential of iPSC line to form three germ layers, including ectoderm (TUJ1, green), mesoderm (SMA, green), and endoderm (AFP, red). Scale bar: 100 µm. (C) Genomic DNA sequences showing the presence of the heterozygous V715M mutation (GTG to ATG) in the APP gene of the APP-V715M iPSC line. (D) Reverse-transcription PCR analysis showing the absence of integration of the Sendai virus vectors. (E) Karyotype analysis of the APP-V715M iPSC line. (F) In vivo teratoma analysis showing the formation of all three germ layers: Tuj1-positive neurons (ectoderm), cartilage (mesoderm) and gut-like epithelium (endoderm). Scale bar: 100 µm.

To investigate the pathological features of the patient with APP-V715M mutation, we generated an iPSC line from an AD patient carrying the APP-V715M mutation using the technology that we developed for iPSC generation [7]. The APP patient-derived MNCs were reprogrammed using Sendai virus vector (SeVdp) which expresses four reprogramming factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, cMYC, and KLF4) [7,14]. For iPSC generation, we picked more than three individual clones and selected the best growing clone for further analyses. iPSC lines harboring the APP-V715M mutation exhibited the typical expression of pluripotent stem cell markers, including OCT4, SOX2, SSEA4 and TRA-1-81 (Fig. 2A). Differentiation potential of iPSC lines was assessed using in vitro embryoid body formation and in vivo teratoma assays, based on the three-germ layer marker expression (Fig. 2B and 2F). Genotyping of the established iPSC line was confirmed by a conventional sequencing method (Fig. 2C). No SeVdp vector was integrated in the established iPSC line (Fig. 2D) and its karyotype was normal (Fig. 2E).

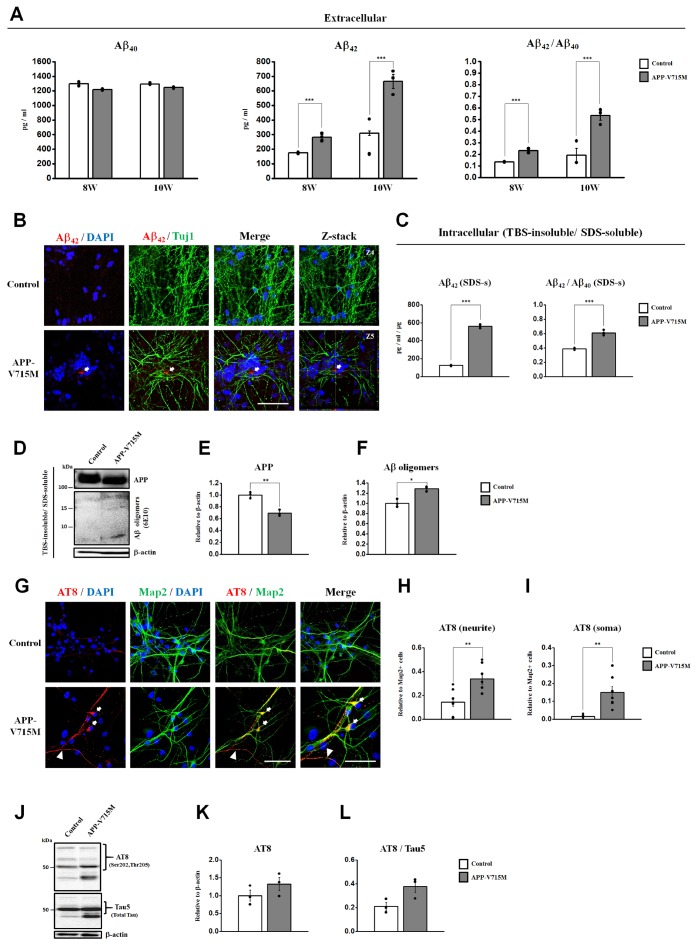

Although the effects of overexpression of the APP-V715M mutation on Aβ secretion have been studied in primary neurons previously [4,5], little has been known about the pathological features of the patients carrying the APP-V715M mutation at cellular levels. To investigate the Aβ levels in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, we measured Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels both extracellularly and intracellularly at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. No significant difference in Aβ40 level was detected. However, the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons exhibited a dramatic increase in Aβ42 level (i.e., over 2-fold) at 10 weeks of differentiation. Importantly, the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 was significantly increased (i.e., over 2-fold) in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived group, compared with the control group (Fig. 3A). To detect the Aβ deposits, the iPSC-derived neurons were stained with anti-Aβ42 antibody at 10 weeks of neural differentiation. Notably, confocal microscopy images showed a robust increase in the extracellular Aβ42 deposits in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, compared to the control (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we extracted the TBS-insoluble/SDS-soluble fraction according to the previous protocols [16,17]. The TBS-insoluble/SDS-soluble intracellular Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels were measured in a total 1µg of proteins using ELISA at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. Levels of the intracellular Aβ42 and the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 were significantly increased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons (Fig. 3C). Western blot analysis showed that the expression level of total APP was significantly decreased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons (Fig. 3D and 3E). By contrast, the Aβ oligomers showed a significant increase in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, compared with the control (Fig. 3D and 3F). It has been recently demonstrated in vitro that the increase and accumulation of Aβ peptides can lead to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles consisting of aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau [16]. Tau protein normally exists as a soluble form in the axons of mature neurons. However, when it becomes hyperphosphorylated, p-tau protein abnormally accumulates in the dendrites and the cell bodies in AD [18,19]. To investigate the p-tau levels in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, we performed an immunocytochemical analysis using an antibody against AT8 (phosphorylated at Ser202/Thr205). We found that the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons exhibited a significant increase of AT8 expression in the neurites and the soma, compared with the control group (Fig. 3G~I). Furthermore, we performed Western blot to measure the AT8 protein levels and found that the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons showed an increase of tau levels, compared with the control group (Fig. 3J~L). Taken together, we demonstrated that the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons exhibited significant increases both in extracellular and intracellular Aβ levels and increased levels of p-tau levels, compared with the control group.

Fig. 3. Increase of Aβ and p-tau levels in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. (A) ELISA detection of the extracellular Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels secreted from the iPSC-derived neurons into the medium. (B) Immunocytochemical analysis showing the expression of Aβ deposits using an antibody against Aβ42 (red), co-stained with Tuj1 (green) and DAPI (blue) at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. The fourth figures (from the left) show the z-stack images of the Aβ42-positive Aβ deposits (indicated as arrows) in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. (C) The TBS-insoluble/SDS-soluble intracellular Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels were measured in a total 1 µg of proteins using ELISA at 10 week-differentiated neurons. (D~F) Quantification of the expression level of total APP and Aβ oligomers. Note that levels of Aβ oligomers were increased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. (G) Immunocytochemical analysis showing the expression of AT8 (p-tau) (red) and MAP2 (green), counter-stained with DAPI (blue) in the iPSC-derived neurons at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. Expression of AT8 (p-tau) was indicated in the soma (arrow) and the neurites (arrowhead) (H~I) Quantification of the immunocytochemical analysis, normalized against MAP2-positive cells. (J~L) Western blot analysis showing an increase of AT8 and the ratio of AT8/Tau5 in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. Scale bar: 10 µm. Data are presented as mean±SEM. Sample sizes: Fig. 3A, C, E, F, K and L (n=3); Fig. 3H and I (n=7). Two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; and ***p<0.001.

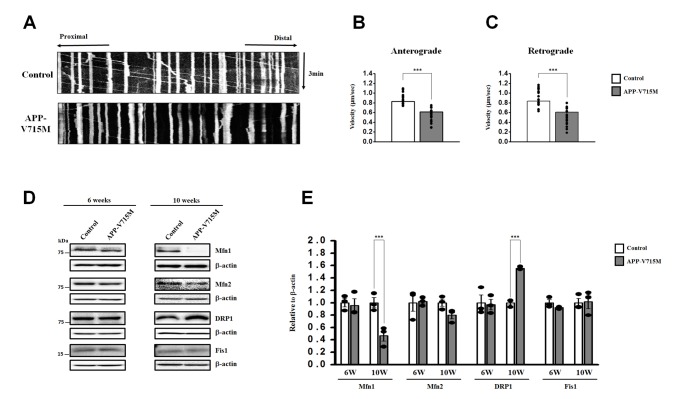

To investigate the mitochondrial dynamics, we performed the live cell imaging analysis using Mito-tracker (Ds-Red) at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. We found that the APP-V715M iPSCderived neurons showed a reduced movement compared with the control group (Supplementary movie files 1 and 2). Kymograph (Fig. 4A) and the quantification analysis of mitochondria velocity were performed using KymographClear and KymographDirect, respectively [15]. Both anterograde and retrograde velocity were significantly decreased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons compared with the control group (Fig. 4B and 4C). Furthermore, we investigated the expression levels of mitochondrial fusion and fission-related proteins at 6 and 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation, including mitochondria fusion-related protein Mfn1 (membrane proteins mitofusin 1), Mfn2 (membrane proteins mitofusin 2) and mitochondria fission-related proteins DRP1 (dynaminrelated protein 1) and Fis1 (mitochondrial fission 1 protein). There was no significant difference of fusion and fission-related protein expression in the control and APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons at 6 weeks of neuronal differentiation. At 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation, Western blot analysis revealed that Mfn1 expression was dramatically reduced, whereas DRP1 expression levels were significantly increased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, compared with the control neurons (Fig. 4D and 4E). In accordance with previous reports, in which accumulated Aβ and p-tau affect mitochondrial functions, our results strongly suggest that high levels of Aβ and p-tau may disrupt the mitochondrial transport, presumably due to the impaired balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons.

Fig. 4. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and the impaired balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons. (A) Representative kymographs for mitochondrial movements. Cells were live stained using Mito-tracker at 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. Average of anterograde (B) and retrograde (C) velocity were analyzed separately in motile mitochondria from iPSC-derived neurons. In both cases, significant decrease was observed in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons compared with the control. (D) The Western blot images were from the representative results of three independent experiments. (E) Quantification of the protein levels associated with mitochondrial fusion (Mfn1and Mfn2) and fission (DRP1 and Fis1) at 6 and 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation. Note that fusion-related protein Mfn1 was decreased, whereas fission-related protein DRP1 was increased in the APP-V715M iPSC--derived neurons compared with the control. Data are presented as mean±SEM. Sample sizes: Fig. 4B and 4C (n=20); Fig. 4E (n=7). Two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. ***p<0.001.

Mitochondria plays an important role in neuronal function and survival, and mitochondrial dysfunction is one of the most prominent features in the AD brains [9]. We investigated the mitochondrial dynamics in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, which exhibited a dramatic decrease of mitochondria movement as well as the anterograde and retrograde mitochondrial velocity using Mito-tracker (Supplementary movie files 1, 2 and Fig. 4). Mitochondrial dynamics is determined by the constantly repeating process of fusion and fission, and this process is tightly regulated by the balance of fusion and fission-related proteins [10,20]. As extracellular Aβ and phosphorylated tau are implicated in the impairment of mitochondrial fission and fusion processes in humans [10,20,21], we measured the expression level of fusion and fissionrelated markers at 6 and 10 weeks of neuronal differentiation, because APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons showed a significant increase in Aβ levels from 8 weeks of neuronal differentiation (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis revealed that the expression of fission-associated markers was significantly increased, but fusion-related markers were significantly decreased in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons at 10 weeks. However, this difference was not clearly detected at 6 weeks of neuronal differentiation (Fig. 3D and 3E). Based on these findings, we speculated that the increased Aβ secretion and phosphorylated tau proteins can lead to the defective mitochondrial axonal transport and the imbalance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons.

In summary, we generated an iPSC line from AD patient with the APP-V715M mutation for the first time. We also characterized the pathological features of APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons, including increased levels of extracellular and intracellular Aβ as well as phosphorylated tau, and identified that mitochondrial dysfunction may be a key contributing factor to AD pathophysiology in the APP-V715M iPSC-derived neurons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI14C2746, HI14C3319, HI18C0335020119), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018M3C7A1056894), the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE 10060305), and the Asan Institute for Life Sciences (2016-0670). We are also grateful to Tokiwa-Bio, Ajinomoto and Matrixome for providing the SeVdp vectors, StemFit® medium and iMatrix-511, respectively for our iPSC research, and to Drs. John C. Morris and Chang-Seok Ki for their valuable comments for the case. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

L.L., J.H.R., H.J.K., D.L.N., and J.S. were responsible for the study concept and design. L.L., J.H.R., H.J.K., H.J.P., M.K., W.K., H.H., J.W.C., M.N., and T.Y. were responsible for data acquisition. L.L., J.H.R., and J.S. performed data analysis and manuscript writing. J.S. and D.L.N. finalized the manuscript. L.L., J.H.R. and H.J.K. contributed equally.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Goedert M, Spillantini MG. A century of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2006;314:777–781. doi: 10.1126/science.1132814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. 2012;148:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohamet L, Miazga NJ, Ward CM. Familial Alzheimer's disease modelling using induced pluripotent stem cell technology. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6:239–247. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Jonghe C, Esselens C, Kumar-Singh S, Craessaerts K, Serneels S, Checler F, Annaert W, Van Broeckhoven C, De Strooper B. Pathogenic APP mutations near the γ-secretase cleavage site differentially affect Aβ secretion and APP C-terminal fragment stability. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1665–1671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park HK, Na DL, Lee JH, Kim JW, Ki CS. Identification of PSEN1 and APP gene mutations in Korean patients with early-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:213–217. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Roh JH, Chang EH, Lee Y, Lee S, Kim M, Koh W, Chang JW, Kim HJ, Nakanishi M, Barker RA, Na DL, Song J. iPSC modeling of presenilin1 mutation in Alzheimer's disease with cerebellar ataxia. Exp Neurobiol. 2018;27:350–364. doi: 10.5607/en.2018.27.5.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burté F, Carelli V, Chinnery PF, Yu-Wai-Man P. Disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:11–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manczak M, Calkins MJ, Reddy PH. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal interaction of amyloid beta with mitochondrial protein Drp1 in neurons from patients with Alzheimer's disease: implications for neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2495–2509. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manczak M, Reddy PH. Abnormal interaction of VDAC1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5131–5146. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen KJ, Moye J, Armson RR, Kern TM. Health screening and random recruitment for cognitive aging research. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:204–208. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh M, Kawagoe S, Okano HJ, Nakagawa H. Integration-free T cell-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from a patient with lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome (LDS) carrying an insertion-deletion complex mutation in the FOXC2 gene. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2016;16:611–613. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangeol P, Prevo B, Peterman EJ. KymographClear and KymographDirect: two tools for the automated quantitative analysis of molecular and cellular dynamics using kymographs. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:1948–1957. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-06-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi SH, Kim YH, Hebisch M, Sliwinski C, Lee S, D'Avanzo C, Chen H, Hooli B, Asselin C, Muffat J, Klee JB, Zhang C, Wainger BJ, Peitz M, Kovacs DM, Woolf CJ, Wagner SL, Tanzi RE, Kim DY. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2014;515:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Yoo J, Shin J, Chang Y, Jung J, Jo DG, Kim J, Jang W, Lengner CJ, Kim BS, Kim J. Modelling APOE ε3/4 allele-associated sporadic Alzheimer's disease in an induced neuron. Brain. 2017;140:2193–2209. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zempel H, Mandelkow E. Lost after translation: missorting of Tau protein and consequences for Alzheimer disease. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manczak M, Reddy PH. Abnormal interaction between the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 and hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer's disease neurons: implications for mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2538–2547. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C, Choi H, Jung ES, Lee W, Oh S, Jeon NL, Mook-Jung I. HDAC6 inhibitor blocks amyloid beta-induced impairment of mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.