Summary

Both caloric restriction (CR) and mitochondrial proteostasis are linked to longevity, but how CR maintains mitochondrial proteostasis in mammals remains elusive. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are well known for gene silencing in cytoplasm and have recently been identified in mitochondria, but knowledge regarding their influence on mitochondrial function is limited. Here, we report that CR increases miRNAs, which are required for the CR-induced activation of mitochondrial translation, in mouse liver. The ablation of miR-122, the most abundant miRNA induced by CR, or the retardation of miRNA biogenesis via Drosha knockdown significantly reduces the CR-induced activation of mitochondrial translation. Importantly, CR-induced miRNAs cause the overproduction of mtDNA-encoded proteins, which induces the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), and consequently improves mitochondrial proteostasis and function. These findings establish a physiological role of miRNA-enhanced mitochondrial function during CR and reveal miRNAs as critical mediators of CR in inducing UPRmt to improve mitochondrial proteostasis.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Molecular Biology, Cell Biology, Functional Aspects of Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

CR increases miRNA biogenesis and the global expression of miRNAs in mitochondria

-

•

miRNAs are critical for CR-induced activation of mitochondrial translation

-

•

CR-induced miRNAs cause overproduction of mtDNA-encoded proteins and induce UPRmt

Biological Sciences; Molecular Biology; Cell Biology; Functional Aspects of Cell Biology

Introduction

Mitochondrion, a semi-autonomous organelle, encodes and locally expresses a number of subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes that generate the vast majority of cellular ATP (Koopman et al., 2013). Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or defects in mitochondrial translation disrupt mitochondrial proteostasis to cause serious human diseases (Boczonadi and Horvath, 2014, Kauppila et al., 2017, Park and Larsson, 2011); conversely, mild mitochondrial proteostatic stress induces the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) to improve mitochondrial proteostasis and has been increasingly linked to longevity in C. elegans (Houtkooper et al., 2013). Caloric restriction (CR) without malnutrition has been proven to extend the lifespan in a wide range of organisms (Fontana and Partridge, 2015, Fontana et al., 2010). Among the myriad of CR-induced changes, mitochondrial processes, including mitochondrial proteostasis, are notably affected (Andreux et al., 2013, Cai et al., 2017, Lanza et al., 2012). However, the mechanism by which mitochondrial proteostasis is improved in mammals in the context of CR is largely unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are evolutionarily conserved RNAs 21–22 nucleotides in length that constitute an important layer of gene regulation in eukaryotes (Chen and Rajewsky, 2007). This group of small noncoding RNAs is well known for gene silencing through either accelerating mRNA degradation or inhibiting translation in the cytoplasm (Hausser and Zavolan, 2014, Ke et al., 2003). Owing to their widespread suppressive effect at the post-transcriptional level, miRNAs reduce protein expression variation (noise) and help maintain homeostasis in diverse biological processes (Ebert and Sharp, 2012, Schmiedel et al., 2015). Recently, a few studies have suggested that CR impacts the expression levels of miRNAs in mouse serum (Dhahbi et al., 2013) and in the serum (Schneider et al., 2017) and skeletal muscle (Mercken et al., 2013) of rhesus monkeys. In addition to the canonical cytosolic localization of miRNAs, emerging evidence has identified miRNAs in mitochondria (Das et al., 2012, Jagannathan et al., 2015, Li et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2014). Recent findings have suggested that miR-1 in skeletal muscle coordinates the myogenic program and that miR-21 in cardiac tissues lowers blood pressure by upregulating mitochondrial translation (Li et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2014). Nevertheless, compared with the well-studied functions of miRNAs in the regulation of protein expression in the cytoplasm, the role of miRNAs in mitochondria during CR remains elusive. Therefore, it is of interest to investigate whether this group of regulatory RNAs is involved in the beneficial effects of CR on mitochondrial function in mammals.

In the present study, we calorie-restricted mice for 12 weeks and then performed small RNA sequencing to profile miRNA expression in mouse livers. We observed that CR increases global and mitochondrial miRNAs in mouse livers. Importantly, CR-induced miRNAs upregulate mitochondrial translation, which consequently induces UPRmt to improve mitochondrial proteostasis. Our findings suggest miRNAs as a group of mediators in the regulation of mitochondrial proteostasis in response to CR.

Results

CR Increases Global and Mitochondrial miRNA Levels

To investigate whether miRNAs are involved in the beneficial effects of CR in mammals, we used mice as our model organism. We fed 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice a calorie-restricted diet for 12 weeks (20% restricted for the first week and 40% restricted for the remaining 11 week) or food ad libitum (AL) (Figure S1A), as previously described (Liu et al., 2016). Twelve weeks of CR significantly reduced body weight gain (Figure S1B) and reduced lipid accumulation in the liver and adipose tissues (Figures S1C and S1D). The indirect calorimetry examination results showed decreased energy expenditure and a reduced respiratory exchange rate, indicating a preference of lipids as the energy source in the CR mice (Figure S1E); we also observed that the physical activity level increased in CR mice (Figure S1F). Glucose tolerance tests suggest that CR improved glucose regulatory function in mice (Figure S1G). Consistent with a previous report (Mitchell et al., 2018), these observations suggest the successful construction of a CR mouse model, in which 12 weeks of CR significantly reprogrammed the metabolic state of the animals.

To obtain a global landscape of the miRNA profile during CR, we performed small RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in whole liver tissues and in liver mitochondria (Figure 1A). After RNA extraction and quality control (Figures S2A and S2B), the RNA samples were spiked with Arabidopsis thaliana miR168a as an internal control. Analysis of the sequencing results enabled the identification of a total of 421 hepatic miRNAs in both the whole tissue and mitochondrial RNA samples (Figure S2C). As shown in the circos plot, the identified miRNAs are extensively distributed along the genome, and interestingly, the miRNAs in the whole liver tissues and in the mitochondrial samples generally increased during CR (Figure 1B). Consistently, the density plot of miRNA expression in the whole liver tissues of the CR mice exhibits a right shift from the AL mice (Figure 1C), and approximately 70% of the miRNAs were increased by CR (Figure 1D). Likewise, in the mouse liver mitochondria, the majority (∼86%) of miRNAs were increased by CR (Figures 1E and 1F). After ranking the most abundant miRNAs in mouse liver and liver mitochondria, we observed that miR-122, the most abundant miRNA in the liver (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002), accounted for the highest number of CR-induced miRNA reads in the mouse liver and liver mitochondria (Figures S2D and S2E). Particularly in the mitochondria, miR-122 increased the most during CR (Figure 1G). To confirm the CR-induced increase in miRNAs, we performed real-time PCR to examine the expression levels of the abundant miRNAs. We observed that, after normalizing against the spike-in control, the RNA levels of GAPDH and β-actin were not significantly altered, whereas the miRNAs were generally increased in the whole liver tissue samples after CR (Figure 1H). Moreover, using mouse liver mitochondrial RNA samples, we observed that, despite the lack of change in the expression of 5S rRNA, miRNAs were generally increased in the mitochondria after CR (Figure 1I). These results suggest that CR could increase miRNAs in mouse liver and liver mitochondria.

Figure 1.

CR Increases Global and Mitochondrial miRNA Levels

(A) Study design for sRNA-seq of mouse livers in AL and CR groups.

(B) Circos plot of small RNA-seq dataset showing miRNAs differentially expressed in whole liver tissue (total) and in liver mitochondria (mito) in response to CR aligned to the mouse genome. The inset shows an enlarged image of chromosome 1. From the outer to the inner rings: chromosome ideogram; upregulated (red bars) and downregulated (blue bars) miRNAs in whole liver tissues; and upregulated (orange bars) and downregulated (light blue bars) miRNAs in liver mitochondria.

(C) Density plot of miRNAs identified in AL and CR mouse livers normalized to the spike-in ath-miR168a internal control.

(D) Cumulative distribution of CR-induced changes in the expression levels of miRNAs in whole-cell samples derived from mouse livers.

(E) Heatmap of commonly identified miRNAs in all samples generated by small RNA-seq. All expression levels were normalized to the exogenous ath-miR168a as an internal control. AM represents AL mitochondria, and CM represents CR mitochondria.

(F) Volcano plot of CR-induced changes in mouse liver mitochondrial miRNA expression generated by small RNA-seq.

(G) Stacked plot of the ratio of the increased Transcripts Per Million (TPM) value from AL to CR of each miRNA in mouse liver and in liver mitochondria indicated by small RNA sequencing results. miR-122-5p increased the most in the mitochondria, and miR-148a-3p increased the most in the liver during CR.

(H and I) Real-time PCR of miRNAs in whole liver tissues (H) and mouse liver mitochondria (I) in the AL and CR groups normalized to the exogenous ath-miR168a as an internal control; n = 6.

For (H and I), the data represent the mean ± SEM. p Values were obtained using unpaired t test with Welch's correction. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant, compared with the respective AL group.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

miR-122 Is Necessary for the CR-Induced Activation of Mitochondrial Translation

As miRNAs affect protein output on a large scale (Baek et al., 2008, Selbach et al., 2008), we next utilized a stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative mass spectrometry (MS) approach to analyze the hepatic proteome to obtain a global insight into the effect of CR (Figures 2A and S3A–S3C). A total of 3,162 proteins were identified in samples from both the AL and CR groups (Figures S3D and S3E). Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that the differentially expressed proteins were mostly enriched in the mitochondria (Figure 2A). We next analyzed the biological processes in which these mitochondrial proteins are involved and found that the upregulated mitochondrial proteins were most significantly clustered in the electron transport chain and metabolic pathways (Figure 2B). In contrast to the enrichment of translation among all downregulated proteins, translation was significantly upregulated among mitochondrial proteins (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

miR-122 Is Necessary for CR-induced Activation of Mitochondrial Translation

(A) Study design for SILAC-based relative quantitative proteomics of mouse livers in AL and CR groups.

(B) Cellular component GO analysis of differentially regulated proteins using REVIGO.

(C) Biological process GO analysis of upregulated mitochondrial proteins using REVIGO.

(D) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 in Huh7 cells overexpressing miR-122.

(E) Sequences of miR-122 5′ and 3′ mutants aligned with the predicted mt-nd1 and mt-co1 target sequences.

(F) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 expression in Huh7 cells upon the transfection with miR-122 and miR-122 mutants.

(G) Western blot of Ago2 in whole hepatocytes and mitochondria from the AL or CR groups.

(H and I) RNA IP of Ago2 in mouse liver mitochondria (H) or Huh7 cells (I). Bound RNA was analyzed by real-time PCR. IP efficiency was calculated relative to input. n = 3.

(J) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 in Huh7 cells co-transfected with siRNA (Ago2 KD or control) and miRNA (miR-122-5p OE or control).

(K) Real-time PCR of miR-122 in livers of the miR-122 knockout (122KO) mice or the WT littermates in response to AL or CR.

(L) Mitopolysome profiling of WT and 122KO mouse liver tissues in response to AL or CR. MRPL37 and MRPS26 levels were examined. Three biological replicates from each group were pooled in equal amounts. The OD ratio of mitopolysome to mitomonosome was quantified.

(M) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 in the livers of WT and 122KO mice assigned to AL or CR diet. ODs were quantified and normalized to GAPDH.

The data in bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. p Values were obtained using unpaired t test with Welch's correction.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant, compared with the AL group (H), miR-NC group (I), or WT-AL group (K)-(M). #p < 0.05 compared with the WT-CR group.

See also Figures S3–S5.

Emerging evidence has suggested, in addition to the canonical gene silencing function of miRNAs in the cytoplasm (Baek et al., 2008, Selbach et al., 2008), that mitochondrial miRNAs may play a positive role in mitochondrial translation (Li et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2014). The substantial increase in mitochondrial miRNAs in the CR mouse liver (Figure 1) and the proteome enrichment in mitochondrial translation (Figure 2C) prompted us to explore whether miRNAs are involved in the regulation of mitochondrial translation by CR. Because miR-122, the liver-specific miRNA (Chang et al., 2004, Jopling, 2012), is involved in many metabolic processes (Bian et al., 2010, Krutzfeldt et al., 2005, Yang et al., 2012) and exhibited the most abundant mitochondrial miRNA reads in the CR mouse liver (Figures S2D and S2E), we studied miR-122 as a representative miRNA in the liver mitochondria during CR.

We overexpressed the miR-122 mimic in Huh7 cells and conducted western blot analysis. We observed that miR-122 overexpression (OE) increased the protein expression levels of the mtDNA-encoded genes, including MTND1 and MTCO1 as the representative subunits of OXPHOS complexes I and IV, respectively (Koopman et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2014) (Figure 2D). Next, we investigated whether miR-122 directly targeted mt-nd1 and mt-co1 mRNAs to account for their increased expression. We searched for potential miR-122-binding sites in the coding regions of mt-nd1 and mt-co1 using PITA (Kertesz et al., 2007) and then inserted the predicted sequences in the open reading frames of mt-nd1 and mt-co1 at the 3′UTR of a luciferase reporter (Figure S4A). We observed that miR-122 inhibited the luciferase activities of the reporters containing the predicted miR-122 target sites in 293T cells (Figure S4B). These data suggest that miR-122 has the capacity to directly target the predicted sites in mt-nd1 and mt-co1. We further designed and synthesized an miRND1 mimic that specifically targets mt-nd1 and an miRCO1 mimic that specifically targets mt-co1. After transfecting 293T cells, we observed that miRND1 robustly inhibited the luciferase activities of Luc-MTND1 and that miRCO1 suppressed the activities of Luc-MTCO1 (Figures S5A and S5B). Importantly, the western blot analysis demonstrated that, in Huh7 cells, transfection with miRND1 specifically increased the protein expression level of MTND1 (Figures S5C and S5D) and transfection with miRCO1 increased the protein expression level of MTCO1 (Figures S5C–S5E). Finally, we constructed miR-122 5′ and 3′ mutants with disrupted complementarity to the predicted binding sites at mt-nd1 and mt-co1 (Figure 2E) and observed that, although miR-122 increased the expression of MTND1 and MTCO1 in Huh7 cells, the mutant miR-122 mimics did not (Figure 2F). These results indicate that miR-122 increased the protein expression of MTND1 and MTCO1 through a complementary base-pairing mechanism.

In the cytoplasm, miRNAs were reported to silence gene expression by binding to Argonaute 2 (Ago2) proteins (Hock and Meister, 2008). In addition to being present in the cytoplasm, Ago2 has also been observed in the mitochondria (Zhang et al., 2014). In mouse liver mitochondria, we detected the presence of Ago2 and observed that CR increased the protein level of Ago2 in the mitochondria (Figure 2G). We next examined the binding capacity of Ago2 through RNA immunoprecipitation and quantitative PCR and observed that CR elevated the levels of miR-122 and its target mRNAs (mtnd1 and mtco1) bound to the Ago2 protein in mitochondria (Figure 2H). In addition, miR-122 OE mimicked the CR effect of increasing the binding of Ago2 to mtnd1 and mtco1 (Figure 2I). Importantly, we co-transfected miR-122 with siRNA against Ago2 in Huh7 cells, and we observed that Ago2 KD abrogated the miR-122 OE-induced increase in the protein levels of mitochondrial-encoded genes (Figure 2J). Therefore, the increased binding of Ago2 to mitochondrial RNAs is involved in the miRNA-mediated elevation of mitochondrial translation during CR.

To further investigate the importance of endogenous miR-122 in the regulation of mitochondrial translation by CR, we used the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Wang et al., 2013) to knock out (KO) miR-122 in mice and then subjected the miR-122 KO (122KO) mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates to 12 weeks of CR. Real-time PCR revealed an increase in miR-122 as a result of CR in the WT mouse livers and the abolishment of miR-122 in the 122KO mouse livers (Figure 2K). Next, we isolated the liver mitochondria and performed mitochondrial polysome profiling to evaluate the mitochondrial translational activity. The results showed that CR increased the proportion of mitoribosomes in the polysomal fractions, demonstrating an upregulated mitochondrial translation, but miR-122 deficiency suppressed the CR-induced upregulation (Figure 2L). Accordingly, the CR-induced increase in MTND1 and MTCO1 expression was impaired in the 122KO livers (Figure 2M). These results suggest that miR-122, the most abundant hepatic miRNA induced by CR, is critical in mediating CR-enhanced mitochondrial translation.

miRNA Biogenesis Is Required for the CR-Induced Activation of Mitochondrial Translation

In addition to increased miR-122 as a representative miRNA, the small RNA-seq results revealed that CR induced a global increase in miRNA contents in mouse livers. Therefore, we next investigated whether miRNA biogenesis, which affects the maturation of multiple miRNAs (Bartel, 2018, Treiber et al., 2018), is affected by CR and whether it is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial translation. We performed real-time PCR and observed that CR increased the RNA levels of multiple components involved in the miRNA biogenesis pathway, including Dicer, Ago2, and exportin 5 (Xpo5), in mouse livers (Figure 3A). In addition, a western blot analysis showed a marked increase in these miRNA biogenesis factors, including Drosha, Dicer, and Ago2, in response to CR (Figure 3B). To study the importance of CR-induced miRNA biogenesis in the regulation of mitochondrial translation, we knocked down (KD) Drosha and Dicer, two ribonucleases required for the maturation of miRNAs, in Huh7 cells. The western blotting analysis showed that KD of either Drosha or Dicer markedly decreased the protein expression levels of the mtDNA-encoded genes MTND1 and MTCO1 (Figure 3C). Conversely, we overexpressed Drosha and Dicer in Huh7 cells and observed that, although Dicer OE did not affect MTND1 or MTCO1 expression to a measurable level, Drosha OE significantly increased MTND1 and MTCO1 expression in Huh7 cells (Figure 3D). These results suggest that Drosha might be a rate-limiting factor in the miRNA-mediated enhancement of mitochondrial translation.

Figure 3.

Drosha is the Rate-limiting Factor in CR-Induced Activation of Mitochondrial Translation

(A) Real-time PCR of miRNA biogenesis factors in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups normalized to β-actin; n = 6.

(B) Western blot of miRNA biogenesis factors in liver tissues from AL and CR groups.

(C and D) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 in response to siRNA-mediated knockdown (KD, C) and overexpression (OE, D) of Drosha or Dicer in Huh7 cells.

(E) Mitopolysome profiling of mouse liver tissues in response to GFP control and shDrosha adenovirus infection. MRPL37 and MRPS26 levels were examined. Three biological replicates from each group were pooled in equal amounts. The OD ratio of mitopolysome to mitomonosome (55S) was quantified.

(F) Western blot of MTND1 and MTCO1 in the livers of mice in the AL and CR groups infected with GFP control or shDrosha adenovirus. ODs were quantified and normalized to GAPDH.

For A, E, and F, the data represent the mean ± SEM. p Values were obtained using unpaired t test with Welch's correction. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, not significant, compared with the AL-Adv-GFP group. #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001, compared with the CR-Adv-GFP group.

See also Figure S6.

Next, we knocked down Drosha (through tail vein injection of adenoviruses expressing Drosha-targeted shRNA [Adv-shDrosha]) in the C57BL/6J mouse livers after 12 weeks of CR to investigate the importance of miRNAs in vivo (Figure S6). The Drosha KD significantly reduced miRNAs, including miR-122 (Figure S6C). Seven days after adenovirus injection, the mouse livers were collected and the hepatic mitochondria were isolated, followed by mitochondrial polysome profiling. The results showed that CR increased the presence of mitoribosomes in the polysomal fractions from the Adv-GFP scrambled control virus-injected mice, whereas the Adv-shDrosha virus significantly prevented the CR-induced increase in mitopolysomes (Figure 3E). Accordingly, the Adv-shDrosha virus abrogated the CR-induced increase in the expression of MTND1 and MTCO1 in the liver (Figure 3F). These results suggest that augmented miRNA biogenesis is critical for the CR-induced increase in mitochondrial translation.

CR Induces the Overproduction of Mitochondrial-Encoded Proteins and UPRmt

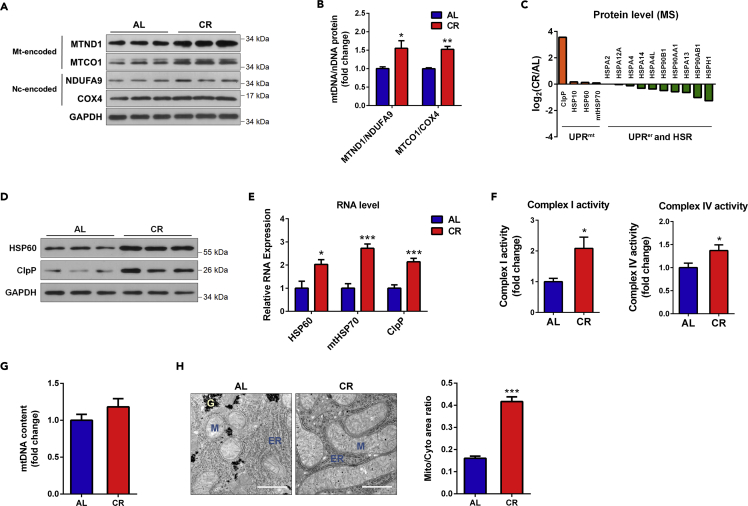

The above-mentioned results regarding the liver-specific miRNA, miR-122, and the miRNA biogenesis factor, Drosha, suggest that miRNAs are key factors in mediating the CR-induced activation of mitochondrial translation. Western blotting showed that, as a result of the upregulated mitochondrial translation, the mitochondrial-encoded proteins were overproduced (Figure 4A), raising the stoichiometric ratios of mtDNA-encoded to nDNA-encoded subunits in the same complexes (i.e., MTND1 to NDUFA9 in complex I and MTCO1 to COX4 in complex IV) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

CR Induces the Overproduction of Mitochondrial DNA-Encoded Proteins and UPRmt

(A) Western blot of the mtDNA and nDNA-encoded mitochondrial subunits in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups.

(B) OD ratios of the nDNA-encoded to mtDNA-encoded subunits of blots (A) were quantified; n = 3.

(C) Protein levels of UPRmt, UPRer, and heat shock response (HSR) effectors in the AL and CR groups obtained from the MS dataset.

(D) Western blot of the UPRmt effectors HSP60 and ClpP in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups.

(E) Real-time PCR of the UPRmt effectors in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups; n = 5.

(F) Activities of mitochondrial complexes I (left) and IV (right) in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups; n = 6.

(G) mtDNA contents in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups were examined by real-time PCR quantification of the mtDNA to nuclear genome ratios; n = 6.

(H) Representative images of mitochondria in mouse livers in the AL and CR groups obtained using a transmission electron microscope. M indicates mitochondria. ER indicates endoplasm reticulum. G indicates glycogen. Scale bars represent 2 μm. The ratio of mitochondrial to cytoplasmic area was quantified using Image-Pro Plus; n = 6.

The data in bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. p Values were obtained using unpaired t test with Welch's correction. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the corresponding AL group.

The complete structure and full function of OXPHOS complexes require precise interactions and coordination between the nDNA-encoded and mtDNA-encoded subunits (Fernandez-Vizarra et al., 2009). The moderate imbalance between mtDNA- and nDNA-encoded proteins has been shown to induce UPRmt (Houtkooper et al., 2013), which responds to proteostatic stress in mitochondria to restore mitochondrial homeostasis (Haynes and Ron, 2010). Hence, we next investigated whether UPRmt was induced by CR in mice. At the protein level, as suggested by our MS data (Figure 4C), although the effectors of ER UPR (UPRer) and heat shock response (HSR) decreased, the UPRmt effectors, including HSP60, mtHSP70, and peptidase ClpP, tended to increase during CR (Figure 4C). Western blotting confirmed a marked increase in HSP60 and ClpP expression in the CR mouse livers (Figure 4D). Consistently, real-time PCR results showed that the RNA expression levels of UPRmt effectors were induced by CR at the mRNA level (Figure 4E). Next, we examined whether the overproduction of mtDNA-encoded OXPHOS subunits affects mitochondrial function. Consistent with the previous finding that CR enhances mitochondrial respiration (Lanza et al., 2012, Lopez-Lluch et al., 2006), the activities of OXPHOS complexes significantly increased in mouse livers during CR (Figure 4F). Moreover, transmission electron microscopy showed the elongation and expansion of mitochondria in the CR mouse livers, indicating an increase in the relative content of mitochondria and improved mitochondrial morphology in response to CR (Figures 4G and 4H). Taken together, these observations support improved mitochondrial proteostasis and mitochondrial function in the mouse liver after CR.

miRNAs Mediate CR-Induced UPRmt and Enhancement of Mitochondrial Function

To investigate the importance of CR-induced miRNAs in the regulation of mitochondrial function, we overexpressed Drosha in Huh7 cells and examined the expression of UPRmt effectors. Western blot analysis showed that Drosha OE increased ClpP expression in Huh7 cells (Figure 5A). Hence, we next investigated the involvement of miRNAs in enhancing mitochondrial activities. We observed that Drosha OE increased the activities of the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes I and IV in transfected Huh7 cells (Figure 5B). Additionally, we overexpressed miR-122 in Huh7 cells and observed that miR-122 OE increased the expression of both HSP60 and ClpP (Figure 5C) as well as the activities of the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes I and IV in Huh7 cells (Figure 5D). To further study the importance of endogenous miRNAs in CR-induced UPRmt and enhanced mitochondrial complex activities, we examined the expression of UPRmt effectors in the livers of WT and 122KO mice fed an AL or CR diet. The results showed that, although CR increased HSP60 and ClpP expression in the livers of WT littermates, the effects were lost in the livers of the 122KO mice (Figure 5E). In addition, CR significantly reinforced the activities of the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes I and IV in the WT mice but not in the 122KO mice (Figure 5F). Consistently, 122KO weakened CR-induced metabolic reprogramming, such as the improvement in the overall energy metabolism and physical activity, except for the effect on energy expenditure, providing the possibility that CR-induced miRNAs in liver exert the beneficial effects on whole body (Figure 5G). Together, CR-induced miRNAs, particularly miR-122, are important for the CR-induced UPRmt and enhanced mitochondrial function.

Figure 5.

miRNAs Mediate CR-Induced UPRmt and Enhancement of Mitochondrial Function

(A and C) Western blot of HSP60 and ClpP in Huh7 cells overexpressing Drosha (A) or miR-122 (C).

(B and D) Activities of the mitochondrial complexes I (left) and IV (right) in Huh7 cells overexpressing Drosha (B) or miR-122 (D); n = 3.

(E) Western blot of HSP60 and ClpP in the livers of WT and 122KO mice in response to AL or CR diet; n = 3.

(F) Activities of the mitochondrial complexes I (left) and IV (right) in the livers of WT and 122KO mice in response to AL or CR diet; n = 4.

(G) Indirect calorimetric examination of oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, energy expenditure, respiratory exchange rate (RER), and total and ambulatory activity of WT or 122KO mice in the AL and CR groups; n = 5.

The data in bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. p Values were obtained using unpaired t test with Welch's correction. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the corresponding control or WT-AL group. ##p < 0.01, compared with the 122KO-AL group.

Discussion

In summary, we report that CR induced a global increase in miRNAs in a mouse model to improve mitochondrial proteostasis in mice. Specifically, at least partially by upregulating translation in the mitochondria, CR-induced miRNAs caused the overproduction of mtDNA-encoded proteins, which resulted in mild proteostatic stress in the mitochondria and consequently induced UPRmt to enhance mitochondrial proteostasis and function. Moreover, we demonstrated that the ablation of miR-122, the most abundant hepatic mitochondrial miRNA, or knockdown of Drosha, a key ribonuclease for miRNA biogenesis, blunts the effect of CR on the regulation of mitochondrial translation, UPRmt, and mitochondrial function. Therefore, our study uncovered the previously unrecognized critical role of miRNAs in linking CR to improved mitochondrial proteostasis and function.

In the present study, we observed that CR increased mitochondrial miRNAs in mouse livers and that miR-122, the most abundant and liver-specific miRNA (Chang et al., 2004, Jopling, 2012), accounted for the highest number of reads that were induced in mitochondria during CR. The identification of mitochondrial miRNAs has received increasing attention. Unlike miRNAs in the cytoplasm, tissue-specific mitochondrial miRNAs have been reported to activate mitochondrial translation in the myoblasts and cardiomyocytes (Li et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2014). In the present study, we confirmed the positive effect of miRNAs on mitochondrial protein expression in liver by observing that miR-122 increased the expression of the OXPHOS subunits MTND1 and MTCO1. Mechanistically, the positive regulation of mitochondrial-encoded genes by miR-122 appears to rely on a complementary base-pairing mechanism and the binding of Ago2 to mitochondrial targets (Figures 2 and S4). Furthermore, the observation that synthetic miRND1 and miRCO1 specifically upregulate the protein expression of their mitochondrial targets MTND1 and MTCO1, respectively (Figure S5), suggests a potentially universal mechanism by which miRNAs activate the protein expression of their mitochondrial targets.

After being transcribed, the levels of mature miRNAs are determined by the efficiency of miRNA processing (Treiber et al., 2018). A previous study reported that Dicer is downregulated in adipose tissue as mice age, thus resulting in declined miRNA processing and the decrease in multiple miRNAs, but CR can prevent the miRNA decline (Mori et al., 2012). In the present study, we found that CR upregulates several miRNA biogenesis factors in the mouse liver, among which Drosha is an important factor mediating the effect of CR (Figure 3). The knockdown or overexpression of Drosha can downregulate or upregulate the expression of mt-encoded proteins, respectively (Figures 3B and 3C). Although more detailed mechanisms related to the upregulation of mitochondrial translation by mitochondrial miRNAs remain to be examined, we demonstrated that either knockdown of Drosha or knockout of miR-122 largely reduces the effect of CR on the activation of mitochondrial translation and the improvement of mitochondrial proteostasis in vivo. Therefore, CR-induced miRNA biogenesis and the increased miRNA in mitochondria may play an important physiological role in the upregulation of mitochondrial translation in metabolic systems.

Because different miRNAs target different regions in the mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes, CR-induced miRNAs might collectively contribute to the redundant accumulation of mtDNA-encoded OXPHOS subunits in the mitochondria (Figure 4A). Consistently, Gomes et al. have shown that, owing to HIF-1α upregulation and TFAM downregulation, aging is associated with a specific decline in mitochondrial-encoded OXPHOS subunits, whereas CR reverses this decline by activating NAD-SIRT1 pathway (Gomes et al., 2013). Thus, CR upregulates mitochondrial proteins, particularly mtDNA-encoded OXPHOS subunits, at multiple levels. The slight perturbation of the stoichiometric ratios between mtDNA- and nDNA-derived protein subunits often induces UPRmt, a retrograde pathway that induces a suite of mitochondrial chaperones and proteases (Haynes and Ron, 2010), to augment the stress resistance to improve mitochondrial proteostasis, which is regarded as a conserved longevity mechanism (Houtkooper et al., 2013). However, most previously reported interventions induce UPRmt at the cost of physical functions, and these potential side effects limit their clinical application (Copeland et al., 2009, Dillin et al., 2002, Houtkooper et al., 2013, Lee et al., 2003, Redman et al., 2018, Yee et al., 2014). CR, as a physiological stimulation (Lanza et al., 2012, Lopez-Lluch et al., 2006), was reported to induce UPRmt in Caenorhabditis elegans (Cai et al., 2017), but whether and how UPRmt is induced in calorie-restricted mammals remained unclear. In the present study, we found that CR globally induced miRNAs in the mouse liver to induce UPRmt accompanied by the enhancement of OXPHOS complex activities in the mouse livers and that miRNAs are required for the CR-induced improvements even in the overall metabolism and physical activity of mice. Therefore, these findings provide new evidence supporting that CR might be an effective and safe physiological strategy to induce UPRmt and improve mitochondrial proteostasis for healthy aging and longevity.

Limitations of the Study

Although we observed that the blockage of miRNA biogenesis pathway (drosha) or the ablation of the most abundant hepatic miRNA (miR-122) compromises CR-induced mitochondrial translation, mitochondrial function, and metabolic reprogramming in liver, we do not exclude the possible contribution from certain cytosolic miRNAs that silence relevant targets in the cytoplasm. Therefore, a better mechanistic understanding of how miRNAs locally regulate mitochondrial translation would help dissect the importance of mitochondrial miRNAs in mediating CR's effects.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Evan D. Rosen (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School) for scientific insight. This work was supported by grants from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2017-I2M-1-008, 2016-I2M-1-015, 2016-I2M-1-016, 2016-I2M-1-011), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31571193, 91639304, 91849207), and the Medical Epigenetics Research Center, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2017PT31035, 2018PT31015). Dr. H.Z. Chen is also supported by the Youth Top-Notch Talent Support Program and the Youth Yangtze River Scholar Program in China.

Author Contributions

R.Z., J.-H.Q, and X.-M.W performed and analyzed small RNA-seq. X.W., J.-H.Q, T.Z., P.-C.F., and P.X. performed and analyzed SILAC MS. P.Z. and G.-Y.X. constructed 122KO mice. R.Z., X.W., J.-H.Q., Y.L., and D.-L.H. performed different parts of the other experiments. R.Z., X.W., J.-H.Q., B.L., Y.X., Z.-Q.Z., P.X., H.-Z.C., and D.-P.L. analyzed and discussed the results. R.Z., X.W., J.-H.Q., H.-Z.C., and D.-P.L. conceptualized and designed the study. R.Z., J.-H.Q., H.-Z.C., and D.-P.L. wrote the manuscript. H.-Z.C. and D.-P.L. acquired the funding and supervised the study.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 26, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.06.028.

Contributor Information

Hou-Zao Chen, Email: chenhouzao@ibms.cams.cn.

De-Pei Liu, Email: liudp@pumc.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- Andreux P.A., Houtkooper R.H., Auwerx J. Pharmacological approaches to restore mitochondrial function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:465–483. doi: 10.1038/nrd4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D., Villen J., Shin C., Camargo F.D., Gygi S.P., Bartel D.P. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. 2018;173:20–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Z., Li L.M., Tang R., Hou D.X., Chen X., Zhang C.Y., Zen K. Identification of mouse liver mitochondria-associated miRNAs and their potential biological functions. Cell Res. 2010;20:1076–1078. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczonadi V., Horvath R. Mitochondria: impaired mitochondrial translation in human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;48:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Rasulova M., Vandemeulebroucke L., Meagher L., Vlaeminck C., Dhondt I., Braeckman B.P. Life-span extension by axenic dietary restriction is independent of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitohormesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017;72:1311–1318. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Nicolas E., Marks D., Sander C., Lerro A., Buendia M.A., Xu C., Mason W.S., Moloshok T., Bort R. miR-122, a Mammalian liver-specific microRNA, is processed from hcr mRNA and may downregulate the high affinity cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1. RNA Biol. 2004;1:106–113. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:93–103. doi: 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J.M., Cho J., Lo T., Jr., Hur J.H., Bahadorani S., Arabyan T., Rabie J., Soh J., Walker D.W. Extension of Drosophila life span by RNAi of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1591–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Ferlito M., Kent O.A., Fox-Talbot K., Wang R., Liu D., Raghavachari N., Yang Y., Wheelan S.J., Murphy E. Nuclear miRNA regulates the mitochondrial genome in the heart. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1596–1603. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi J.M., Spindler S.R., Atamna H., Yamakawa A., Guerrero N., Boffelli D., Mote P., Martin D.I. Deep sequencing identifies circulating mouse miRNAs that are functionally implicated in manifestations of aging and responsive to calorie restriction. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:130–141. doi: 10.18632/aging.100540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A., Hsu A.L., Arantes-Oliveira N., Lehrer-Graiwer J., Hsin H., Fraser A.G., Kamath R.S., Ahringer J., Kenyon C. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science. 2002;298:2398–2401. doi: 10.1126/science.1077780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert M.S., Sharp P.A. Roles for microRNAs in conferring robustness to biological processes. Cell. 2012;149:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Vizarra E., Tiranti V., Zeviani M. Assembly of the oxidative phosphorylation system in humans: what we have learned by studying its defects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Partridge L. Promoting health and longevity through diet: from model organisms to humans. Cell. 2015;161:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Partridge L., Longo V.D. Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A.P., Price N.L., Ling A.J., Moslehi J.J., Montgomery M.K., Rajman L., White J.P., Teodoro J.S., Wrann C.D., Hubbard B.P. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013;155:1624–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser J., Zavolan M. Identification and consequences of miRNA-target interactions–beyond repression of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrg3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes C.M., Ron D. The mitochondrial UPR - protecting organelle protein homeostasis. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:3849–3855. doi: 10.1242/jcs.075119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock J., Meister G. The argonaute protein family. Genome Biol. 2008;9:210. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper R.H., Mouchiroud L., Ryu D., Moullan N., Katsyuba E., Knott G., Williams R.W., Auwerx J. Mitonuclear protein imbalance as a conserved longevity mechanism. Nature. 2013;497:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nature12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannathan R., Thapa D., Nichols C.E., Shepherd D.L., Stricker J.C., Croston T.L., Baseler W.A., Lewis S.E., Martinez I., Hollander J.M. Translational regulation of the mitochondrial genome following redistribution of mitochondrial microRNA in the diabetic heart. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2015;8:785–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C. Liver-specific microRNA-122: biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2012;9:137–142. doi: 10.4161/rna.18827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppila T.E.S., Kauppila J.H.K., Larsson N.G. Mammalian mitochondria and aging: an update. Cell Metab. 2017;25:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X.S., Liu C.M., Liu D.P., Liang C.C. MicroRNAs: key participants in gene regulatory networks. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:516–523. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz M., Iovino N., Unnerstall U., Gaul U., Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1278–1284. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman W.J., Distelmaier F., Smeitink J.A., Willems P.H. OXPHOS mutations and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2013;32:9–29. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutzfeldt J., Rajewsky N., Braich R., Rajeev K.G., Tuschl T., Manoharan M., Stoffel M. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with 'antagomirs'. Nature. 2005;438:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Yalcin A., Meyer J., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza I.R., Zabielski P., Klaus K.A., Morse D.M., Heppelmann C.J., Bergen H.R., 3rd, Dasari S., Walrand S., Short K.R., Johnson M.L. Chronic caloric restriction preserves mitochondrial function in senescence without increasing mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2012;16:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.S., Lee R.Y., Fraser A.G., Kamath R.S., Ahringer J., Ruvkun G. A systematic RNAi screen identifies a critical role for mitochondria in C. elegans longevity. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhang X., Wang F., Zhou L., Yin Z., Fan J., Nie X., Wang P., Fu X.D., Chen C. MicroRNA-21 lowers blood pressure in spontaneous hypertensive rats by upregulating mitochondrial translation. Circulation. 2016;134:734–751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang T.T., Zhang R., Fu W.Y., Wang X., Wang F., Gao P., Ding Y.N., Xie Y., Hao D.L. Calorie restriction protects against experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:2473–2488. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lluch G., Hunt N., Jones B., Zhu M., Jamieson H., Hilmer S., Cascajo M.V., Allard J., Ingram D.K., Navas P. Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:1768–1773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercken E.M., Majounie E., Ding J., Guo R., Kim J., Bernier M., Mattison J., Cookson M.R., Gorospe M., de Cabo R. Age-associated miRNA alterations in skeletal muscle from rhesus monkeys reversed by caloric restriction. Aging. 2013;5:692–703. doi: 10.18632/aging.100598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S.J., Bernier M., Mattison J.A., Aon M.A., Kaiser T.A., Anson R.M., Ikeno Y., Anderson R.M., Ingram D.K., de Cabo R. Daily fasting improves health and survival in male mice independent of diet composition and calories. Cell Metab. 2018;29:221–228.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M.A., Raghavan P., Thomou T., Boucher J., Robida-Stubbs S., Macotela Y., Russell S.J., Kirkland J.L., Blackwell T.K., Kahn C.R. Role of microRNA processing in adipose tissue in stress defense and longevity. Cell Metab. 2012;16:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.B., Larsson N.G. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:809–818. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman L.M., Smith S.R., Burton J.H., Martin C.K., Il'yasova D., Ravussin E. Metabolic slowing and reduced oxidative damage with sustained caloric restriction support the rate of living and oxidative damage theories of aging. Cell Metab. 2018;27:805–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedel J.M., Klemm S.L., Zheng Y., Sahay A., Bluthgen N., Marks D.S., van Oudenaarden A. Gene expression. MicroRNA control of protein expression noise. Science. 2015;348:128–132. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A., Dhahbi J.M., Atamna H., Clark J.P., Colman R.J., Anderson R.M. Caloric restriction impacts plasma microRNAs in rhesus monkeys. Aging Cell. 2017;16:1200–1203. doi: 10.1111/acel.12636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M., Schwanhausser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiber T., Treiber N., Meister G. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;20:5–20. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yang H., Shivalila C.S., Dawlaty M.M., Cheng A.W., Zhang F., Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.M., Seo S.Y., Kim T.H., Kim S.G. Decrease of microRNA-122 causes hepatic insulin resistance by inducing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, which is reversed by licorice flavonoid. Hepatology. 2012;56:2209–2220. doi: 10.1002/hep.25912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee C., Yang W., Hekimi S. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway mediates the pro-longevity response to mitochondrial ROS in C. elegans. Cell. 2014;157:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zuo X., Yang B., Li Z., Xue Y., Zhou Y., Huang J., Zhao X., Zhou J., Yan Y. MicroRNA directly enhances mitochondrial translation during muscle differentiation. Cell. 2014;158:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.