INTRODUCTION

Diabetes affects 30.2 million adults in the US and contributes to substantial health and economic burdens.1, 2 While there are many evidence-based interventions that are expected to improve diabetes outcomes,3 many patients with diabetes do not achieve their goals for prevention and treatment,4 particularly less educated individuals and racial/ethnic minorities.5 To improve diabetes disparities and outcomes, resources for implementing evidence-based interventions are needed in the settings where patients with diabetes receive healthcare.3 This study provides national estimates of the distribution of outpatient visits for US adults with diabetes across care settings to inform the delivery of resources for diabetes interventions.

METHODS

We analyzed the 2009 through 2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) which includes visits to non-federal office-based physicians engaged in direct patient care, and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), which includes visits to non-federal hospital emergency departments, and outpatient departments through 2011: these provide annual, nationally representative samples of physician visits.6 Surveys are completed by the sampled physicians and census staff for the designated reporting period. We included visits for adults aged ≥ 18 years, excluding surgical, pediatric, and obstetrics/gynecology visits. We examined two outcomes which are annual mean counts of visits: (1) visits in which a patient was identified as having diabetes by a direct survey question and (2) the subset of these visits in which diabetes was a patient reason for visit: either the chief complaint or one of up to two (2009–2013) or four (2014 onwards) additional reasons for visit. We specified four care settings: primary care offices (general/family practice, internal medicine, geriatrics, and palliative medicine), specialist offices (other medical specialties), hospital outpatient departments, and hospital emergency departments. We compared visit characteristics across settings using survey-weighted Pearson χ2 tests and conducted analyses using Stata (StataCorp) version 14.2 accounting for the complex sampling design. This study met criteria for exemption from institutional review board review.

RESULTS

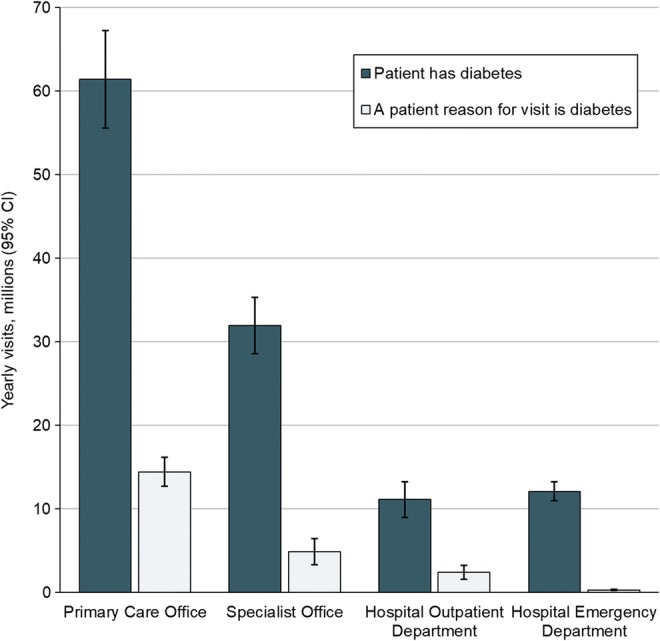

Most visits for US adults with diabetes occurred in primary care offices, followed by specialist offices, hospital emergency departments, and hospital outpatient departments (Fig. 1). Among non-hospital-based office visits, primary care comprised 65.8% (95% CI 63.1–68.4%) of visits for patients with diabetes and 75.8% (95% CI 67.9–80.7%) of visits in which diabetes was a patient reason for visit. In primary care offices, the proportion of visits for patients with diabetes in which diabetes was a patient reason for visit was 23.5% (95% CI 21.7–25.5%) which was higher than that in other settings: 15.2% (95% CI 11.5–19.9%), 21.6% (95% CI 17.1–27.0%), and 2.5% (95% CI 1.9–3.1%) in specialist offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments, respectively. Diabetes was the chief complaint in 59.6% (95% CI 55.3–63.7%) of visits in which diabetes was a patient reason for visit.

Figure 1.

Outpatient visits for adults with diabetes by care setting, 2009–2015. The mean number of yearly visits (millions) for patients with diabetes was 61.4 (95% CI 55.6–67.2), 32.0 (28.6–35.3), 11.1 (9.0–13.3), and 12.1 (11.0–13.2) for primary care offices, specialist offices, hospital outpatient departments, and hospital emergency departments, respectively. The mean number of yearly visits (millions) for which diabetes was a patient reason for visit was 14.4 (95% CI 12.7–16.2), 4.9 (3.3–6.4), 2.4 (1.6–3.2), and 0.3 (0.2–0.4) for primary care offices, specialist offices, hospital outpatient departments, and hospital emergency departments, respectively. Hospital outpatient department data were only available from 2009 to 2011.

A greater proportion of patients in primary care office visits were younger, female, and of minority race/ethnicity, compared to specialist office visits (Table 1). Visits to hospital outpatient departments and emergency departments were relatively enriched with patients who were younger, female, and of minority race/ethnicity, compared to other settings. A greater proportion of patients in primary care office visits had type 2 diabetes compared to specialist office and emergency department visits which were relatively enriched with patients with type 1 or unspecified diabetes. There were also significant differences across care settings in insurance payer and geographic location.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Outpatient Visits for US Adults with Diabetes by Care Setting

| Yearly visits, 100,000s (% of visits in care setting) | Primary care vs. specialist, P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care office | Specialist office | Hospital OPD | Hospital ED | ||

| Survey year† | n/a | ||||

| 2009 to 2011 | 632.4 | 304.9 | 111.3 | 110.4 | |

| 2012 to 2013 | 539.6 | 290.0 | † | 115.0 | |

| 2014 to 2015 | 661.3 | 371.3 | † | 143.0 | |

| All survey years | 614.1 | 319.6 | 111.3 | 121.0 | |

| Age category | 0.002 | ||||

| 18–44 years | 52.7 (8.7) | 23.6 (7.5) | 14.9 (13.6) | 22.8 (19.1) | |

| 45–64 years | 257.7 (42.4) | 121.3 (38.3) | 54.8 (50.0) | 47.7 (40.0) | |

| ≥ 65 years | 297.3 (48.9) | 171.6 (54.2) | 40.0 (36.5) | 48.7 (40.9) | |

| Sex | 0.031 | ||||

| Female | 323.3 (52.6) | 158.9 (49.7) | 65.3 (58.7) | 66.7 (55.1) | |

| Male | 290.9 (47.4) | 160.7 (50.3) | 46.0 (41.3) | 54.3 (44.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity‡ | 0.002 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 385.9 (62.8) | 221.9 (69.4) | 62.6 (56.3) | 70.9 (58.6) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 99.8 (16.3) | 40.1 (12.6) | 27.2 (24.5) | 30.5 (25.2) | |

| Hispanic | 94.5 (15.4) | 32.5 (10.2) | 17.6 (15.8) | 15.6 (12.9) | |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 34.0 (5.5) | 25.1 (7.9) | 3.8 (3.5) | 4.0 (3.3) | |

| Minority race/ethnicity‡ | 228.3 (37.2) | 97.7 (30.6) | 48.7 (43.7) | 50.1 (41.4) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes classification§ | < 0.001 | ||||

| Type 1 diabetes | 18.6 (2.8) | 18.1 (4.9) | § | 8.5 (6.0) | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 433.1 (65.5) | 183.9 (49.5) | § | 54.2 (37.9) | |

| Unspecified diabetes | 209.5 (31.7) | 169.3 (45.6) | § | 80.2 (56.1) | |

| Diabetes was a patient reason for visit | 144.4 (23.5) | 48.7 (15.2) | 24.1 (21.6) | 3.0 (2.5) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes was the chief complaint | 85.6 (13.9) | 28.7 (9.0) | 19.2 (17.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.025 |

| Physician specialty | ‖ | ||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | ‖ | 68.7 (21.5) | ‖ | ‖ | |

| Dermatology | ‖ | 18.7 (5.9) | ‖ | ‖ | |

| Psychiatry | ‖ | 13.0 (4.1) | ‖ | ‖ | |

| Neurology | ‖ | 15.6 (4.9) | ‖ | ‖ | |

| Other medical specialties | ‖ | 203.2 (63.7) | ‖ | ‖ | |

| Source of payment for visit | < 0.001 | ||||

| Private insurance | 231.6 (39.5) | 112.0 (36.6) | 30.2 (28.0) | 24.9 (21.7) | |

| Medicare | 279.4 (47.6) | 162.7 (53.2) | 43.9 (40.8) | 55.5 (48.4) | |

| Medicaid | 51.5 (8.8) | 14.9 (4.9) | 19.4 (18.0) | 21.1 (18.4) | |

| Other | 24.3 (4.1) | 16.4 (5.4) | 14.3 (13.2) | 13.2 (11.5) | |

| Geographic region | 0.209 | ||||

| Northeast | 109.1 (17.8) | 65.8 (20.6) | 34.3 (30.8) | 19.9 (16.5) | |

| Midwest | 130.7 (21.3) | 52.9 (16.5) | 30.8 (27.7) | 29.5 (24.4) | |

| South | 236.5 (38.5) | 126.6 (39.6) | 35.3 (31.7) | 49.1 (40.6) | |

| West | 137.8 (22.4) | 74.4 (23.3) | 10.9 (9.8) | 22.5 (18.6) | |

| Metropolitan statistical area | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 528.5 (86.1) | 301.4 (94.3) | 89.1 (80.1) | 87.8 (83.6) | |

| No | 85.6 (13.9) | 18.3 (5.7) | 22.2 (19.9) | 17.3 (16.4) | |

OPD, outpatient department; ED, emergency department

*P value < 0.005 for all three-way comparisons between primary care, medical specialist, and emergency department visits, except geographic region (P = 0.12). P value < 0.02 for all comparisons between all four care settings from 2009 to 2011, except metropolitan statistical area (P = 0.063)

†Hospital outpatient department data were available from 2009 to 2011

‡Approximately 27% of values imputed by the National Center for Health Statistics using a model-based sequential regression including demographic, clinical, and visit characteristics

§Data for diabetes classification were available only from 2014 to 2015

‖Physician specialty subgroups are only relevant to specialist offices

DISCUSSION

The majority of outpatient visits for US adults with diabetes, as well as visits in which diabetes was a patient reason for visit, occurred in primary care offices, followed by specialist offices. To improve the care of patients with diabetes, it is critical to target resources to the healthcare settings where patients with diabetes interact with their physicians.3 Our findings suggest that most diabetes management occurs in primary care offices, which therefore presents a proportional opportunity to improve diabetes care delivery. Hospital-based settings saw a greater proportion of patients of minority race/ethnicity compared to other settings which may be important for targeting interventions to reduce diabetes health disparities in these populations. Limitations of this study include that data regarding certain specialties, including endocrinology, were not available. Nevertheless, the majority of care for US adults with diabetes occurred in the primary care setting where interventions are needed to improve diabetes practices and outcomes.

Contributors

Only the listed authors contributed to the manuscript.

Funders

SJP was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5T32HL007180-40, PI: Hill-Briggs). JBS was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1K24AG049036).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917–28. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. 1. Improving Care and Promoting Health in Populations Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S7–S12. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999-2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1213829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterji P, Joo H, Lahiri K. Racial/ethnic- and education-related disparities in the control of risk factors for cardiovascular disease among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):305–12. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.About the Ambulatory Health Care Surveys [Internet]. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; [cited 2018 August 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/about_ahcd.htm.