Abstract

The current and projected deficit in the physician workforce in the US is a challenge for primary care and specialty medical settings. Foreign medical graduates (FMGs) represent an important component of the US graduate medical education (GME) training pathway and can help to address the US physician workforce deficit. Availability of FMGs is particularly important to the internal medicine community, as recent data demonstrate that internal medicine is the specialty with the highest number of FMGs. System-based and logistical inefficiencies in the current US visa system represent significant obstacles to FMG trainees and have important psychological, emotional, and logistical consequences to FMG engagement and participation in US GME training and in the post-training workforce. In this article, we review the contemporary structure, process, and challenges of obtaining a visa for GME training. The H1B and J1 visa programs are compared and contrasted, with an emphasis on logistical specifics for FMG GME trainees and training programs. The process of and options for J1 visa waivers are reviewed. These considerations are specifically reviewed in the context of recent policy decisions by the Trump administration, with emphasis on the effects of these decisions on FMGs in medical training and practice.

Key Words: foreign medical graduates, immigration, graduate medical education, US physicians’ workforce

INTRODUCTION

The current physician shortfall in the US is expected to worsen.1 There is an estimated deficit of 40,800 to 104,900 physicians by 2030.2 Recent data indicate that 29% of physicians currently practicing in the US were born outside the US.3 In a 2017 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges, international medical graduates (IMGs) comprise one quarter of the current physician workforce in the US.4 The percentage of IMGs in internal medicine is higher than other medical specialties. For instance, the 2016–2017 data resource book of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education shows that IMGs comprise 39.4% of internal medicine residents in the US, such that internal medicine accounts for the highest number of IMGs (10,352) when compared to other training specialty programs.5

The Association of American Medical Colleges reported that 42.3% of hospitalists in the US in 2013 were IMGs.6 IMGs also comprise a significant proportion of the US primary care physician workforce in rural underserved areas.7

Despite representing a significant proportion of the medical workforce, there have recently been increasing obstacles for foreign medical graduates (FMGs) to obtain visas. This review article describes the implications of the current visa system for FMGs given that more than 60% of IMGs are FMGs.8

VISAS AVAILABLE FOR FMGS TO JOIN GME TRAINING

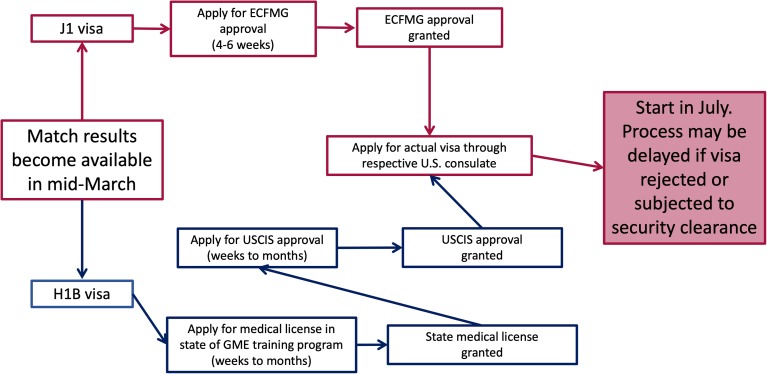

There are currently two main visas available for FMGs to participate in graduate medical education (GME) training: J1 and H1B visas.9, 10 J1 visas are sponsored by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) at no cost to the training hospital,11 whereas H1B visas are sponsored by the training hospital at a cost of $3000–4000 per GME trainee.12 Due to the 2016 cut in Medicare GME funding,13 many residency programs stopped sponsoring H1B visas.14 Hence, the majority of FMGs currently in GME training programs have J1 visas.15

Both J1 and H1B visas can be delayed for several months pending security clearance.16 Delays in residency start dates entitle training programs to request a waiver from their Match commitment through the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).17 In this case, FMGs can lose their residency spots.16 Since 2013, the NRMP imposed an “all in” or “all out” Match requirement.18 Prior to 2013, training programs could offer some spots months before Match Day, which some programs used to start the lengthy visa process as early as possible.18

In a survey of residency program directors, this “all in” or “all out” change by the NRMP has been viewed negatively by programs with higher percentage of FMG applicants.18 In addition, 24% of surveyed programs reported an increase in delayed starting times for FMGs.18 In its recent position paper on immigration, the American College of Physicians (ACP) states:

The more stringent visa and security procedures implemented since September 11, 2001, have resulted in denials and delays of visas to many IMGs seeking to come to the U.S. for residency training. This disrupts residency programs, and program directors may avoid accepting IMGs for this reason.19

Figure 1 illustrates the process of applying for both visas after the Match.

Figure 1.

Timeline for applying for J1 and H1B visas after the Match.

IMPLICATIONS OF CURRENT VISA SYSTEM ON FMGS DURING GME TRAINING

FMGs are usually allowed up to 7 years of GME training on J1 visas, which may limit the opportunities for training in certain advanced subspecialty fellowships.

Extension of the J1 visa beyond 7 years may be permitted on a case-by-case basis if the FMG can demonstrate to the Department of State (DOS) that the country to which he or she will return at the end of subspecialty training has an exceptional need for such subspecialty skills.20 Compared to J1 visas, FMGs who join residency programs on H1B visas face even more limited choices if they aspire to complete fellowship training. Many fellowship programs do not sponsor H1B visas.21 Hence, H1B FMG residents may delay fellowship plans until obtaining a green card through employment via working as a generalist for few years.

With recent changes in the timeline for fellowship Match results to December, an unmatched J1 FMG resident into fellowship may not have enough time to secure a generalist position before his or her visa expires.22 The current visa system has been reported by some FMGs to limit opportunities for subspecialty training.23

IMPACT OF VISA SYSTEM ON FAMILY LIFE OF FMGS AND THE 2017 TRAVEL BAN

There have been reports of some FMGs being unable to visit their families in their home countries for fear of visa denial. There are instances of denial of visa renewal for established trainees, causing great anxiety among FMGs.24

In January 2017, a Presidential Executive Order blocked citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US.25 This executive order was upheld by the Supreme Court in June 2018.26 Jena and colleagues studied the effect this ban could have and found that physicians trained in those banned countries comprise 5% of FMGs practicing in the USA, a total of approximately 8000 physicians.27 Some FMGs participating in US GME programs from these countries who were visiting their families when the Executive Order took place were either denied re-entry to the US or deported after arriving to the US, leading to interruption in their training.28, 29 This ban might have also influenced the chances of FMGs from these countries negatively during the 2017 NRMP Match. Some program directors indicated that they will not rank FMGs from those nationalities because of the concern they would not be able to start residency on time.30 In its 2017 annual meeting, the American Medical Association decried this travel ban and its negative effect on the US physician workforce.31

VISA ISSUES AFTER COMPLETING US GME TRAINING

After completing GME training, there is no geographical restriction on where H1B FMGs can practice in order to obtain a green card. Comparatively, J1 FMGs have to obtain a waiver from the DOS before they are eligible to apply for green card.22 There are few options available for J1 FMGs to obtain a waiver from the DOS.

The first option is to work in a medically underserved area in the US for 3 years, through either the Conrad State 30 Program or the Delta Regional Authority (DRA). The Conrad 30 program covers all US states. The DRA only operates in eight states: Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Recently, Congress allowed the expansion of the number of waivers through the Conrad program from 30 to 35 spots per year per state.32 Congress also allows 3 spots per state for academic medical centers, which may not be in underserved areas.32

Many states give preference to primary care physicians, leaving subspecialty FMGs with limited options. Some states receive far more applications than the allowed slots,33 leaving some FMGs with no options for employment through the Conrad program.

While we are not aware of data about how many FMGs would have to return to their home countries because of inability to adjust their visa status, it is extremely likely that this does happen. For instance, in its report to Congress about the shortage of intensivists in the US, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) stated: “the shortage of intensivists is worsened by an inability of many qualified IMG intensivists to remain in the United States because of visa restrictions.”34

If the J1 FMG is able to secure a waiver position, he or she is generally locked in with an employer for 3 years before being able to apply for a green card. Although changing employers is permitted on a case-by-case basis, this requires the FMG to prove the existence of extenuating circumstances.35 Unfortunately, this has led to abuse by employers in some cases,36 including call schedules that unfairly burden FMGs, pay disparities, and even sexual harassment.36 In a survey of J1 FMGs granted a waiver in the Washington State, 62% of FMGs who had to change employers reported being victims of exploitation.37

Hagopian and colleagues conducted a national survey among J1 waiver program administrators in 42 states, and half or more of respondents reported problems related to payment dispute or issues with employers asking J1 FMGs to work under unfair conditions.33 Indeed, the majority of respondents reported some change in work practices after signing the initial employment contract.33

To try to protect J1 FMGs against pay abuse, states mandate that the J1 FMG is paid according to the “prevailing wage.” While such efforts are to be commended, there is no consensus about what constitutes a “prevailing wage.” In the experience of the authors from interviewing for J1 waiver positions, many employers use the 50th percentile of the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) report on physician compensation. While nominally fair, J1 waiver FMGs are usually the sole or among few providers in underserved areas. Hence, call is usually more frequent and work hours are prolonged, such that using the 50th percentile MGMA report may not be the best estimate of fair compensation.

Such vulnerabilities in the legal relationship of J1 waiver FMGs to their employers may account for reported lack of retention of those physicians in underserved areas.38, 39

Another option for J1 FMGs is obtaining sponsorship by an interested US federal government agency, such as the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) or Department of Veterans Affairs. Applying for a waiver through the ARC entails working “for at least three years in rural Appalachian areas that suffer significant shortages of health care providers.”40 These areas are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

States Participating in the Appalachian Regional Commission

| States where FMGs can obtain rural J1 waiver through Appalachian Regional Commission | |

|---|---|

| West Virginia | New York |

| Alabama | North Carolina |

| Georgia | Ohio |

| Kentucky | Pennsylvania |

| Maryland | South Carolina |

| Mississippi | Tennessee |

| Virginia | |

To obtain a waiver through VA hospitals, those hospitals are required to demonstrate a 6-month period of active unsuccessful recruitment efforts of US physicians before they can submit a waiver application for a J1 FMG.41

A third option for FMGs is to apply for hardship and persecution waivers. To obtain a hardship waiver, the applicant must submit evidence that returning to his or her home country would impose exceptional hardship on his or her US citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse or child.42 Persecution waivers require evidence that the applicant would be subjected to persecution on account of race, religion, or political opinion, on returning to the home country.43

At the time of writing this article, the estimated processing time of such waivers is 11–14 months.44

A final option for FMGs is to obtain a HHS research waiver. This option allows FMG J1 physicians to work directly in an academic research setting. Research waiver requests are submitted by the sponsoring academic facility to HHS. For approval, the application must contain evidence that the J1 FMG physician is indispensable to the research program in the sponsoring institution.45 Table 2 summarizes helpful websites for obtaining more information about J1 waivers.

Table 2.

Useful Websites for FMGs for J1 Waivers

| Program for J1 waivers | Website address |

|---|---|

| Information on the Conrad 30 program through the USCIS website | https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/conrad-30-waiver-program |

| DRA program | http://dra.gov/initiatives/promoting-a-healthy-delta/delta-doctors/how-to-apply/ |

| J1 waiver through HHS | https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/oga/about-oga/what-we-do/exchange-visitor-program/index.html |

| The Appalachian Regional Commission J1 waiver program | https://www.arc.gov/program_areas/J1VisaWaivers.asp |

EFFECT OF VISA STATUS OF FMGS ON CHOOSING AN ACADEMIC CAREER

Some authors suggest that FMGs may be able to address the increasing shortage of physician-scientists in the US.46 FMGs do not generally have as significant medical school debts as US graduates,47 potentially making the decision to transition into a physician-scientist career more appealing for FMGs on the outset. However, J1 FMGs who aspire to practice in academic settings have significant challenges, as many academic centers are not in underserved areas and the waiver slots available to them through the Conrad program are limited.32 Table 3 describes the basic differences between J1 and H1 B visas for FMGs.

Table 3.

Differences Between H1B and J1 Visas

| H1B visa | J1 visa | |

|---|---|---|

| Sponsor | Training hospital | ECFMG |

| Fees | Few thousand dollars paid by training program | No fees are paid by training program. The FMG pays a fee of $325 every year to ECFMG and an additional one time $180 to the Department of Homeland Security with the initial J1 visa application |

| Subjected to rejection if applicant is deemed to not have strong ties to home country | Uncommon because H1B is a dual intent visa | Yes |

| Subjected to security clearance | Yes | Yes |

| Duration of training allowed | Usually maximum of 6 years | 7 years that can be extended to 8 years on a case-by-case basis |

| Transition to fellowship | Harder than J1 since few fellowship programs accept H1B visa | Easier than H1B since the majority of fellowship programs accept J1 visas |

| Transition to independent practice | Easier than J1 | Harder process than H1B since a waiver process of the 2 years home country requirement is needed |

Some J1 FMGs may have to go to non-academic private practice for a few years to obtain a green card prior to returning to academic practice.48 This circuitous career trajectory can create anxiety about the potential of being accepted back to academics after spending 3–5 years in private practice fulfilling visa requirements.48 These considerations have conspired to result in an under-representation of FMGs in the academic research, medical education, and administrative settings.24

CONCLUSION

Despite FMGs being welcomed in the medical community,49 the current visa system for FMGs is a significant reason for delays in effectively recruiting and incorporating FMGs into clinical and academic practice in the US and may prompt future FMGs to seek positions in other non-US countries.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kirch DG, Petelle K. Addressing the physician shortage: the peril of ignoring demography. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1947–1948. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IHS Inc. Update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2015 to 2030: final report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017; https://aamcblack.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/a5/c3/a5c3d565-14ec-48fb-974b-99fafaeecb00/aamc_projections_update_2017.pdf. February 28, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 3.Patel YM, Ly DP, Hicks T, Jena AB. Proportion of non-US-born and noncitizen health care professionals in the United States in 2016. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2265–2267. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2017 State physician workforce data book. https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/484392/2017-state-physician-workforce-data-report.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 5.Residents Characteristics. ACGME data resource book. https://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book Academic Year 2016–2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 6.Jones KC, Whatley MM. Hospitalists: a growing part of the primary care workforce. Analysis in Brief. 2016;16(5):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baer LD, Ricketts TC, Konrad TR, Mick SS. Do international medical graduates reduce rural physician shortages? Med Care. 1998;36(11):1534–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckhert NL, van Zanten M. U.S.-citizen international medical graduates—a boon for the workforce? N Engl J Med. 2015;372(18):1686–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1415239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.J1 Visa Exchange Program. https://j1visa.state.gov/. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 10.H1-B Program. https://www.dol.gov/whd/immigration/h1b.htm. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 11.Exchange Visitor Sponsorship Program (EVSP). https://www.ecfmg.org/evsp/. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 12.H1B visa filing fees. https://www.uscis.gov/forms/h-and-l-filing-fees-form-i-129-petition-nonimmigrant-worker. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 13.Riaz M, Palermo T, Yen M, Edelman NH. The projected responses of residency-sponsoring institutions to a reduction in Medicare support for graduate medical education: a national survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1380–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Datta J, Zaydfudim V, Terhune KP. General surgery residency after graduation from U.S. medical schools: visa-related challenges for the international citizen. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(3):292–4. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Physicians. The Role of International Medical Graduates in the U.S. Physician Workforce. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians. A policy monograph. 2005; https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/role_international_medical_graduates_2008.pdf . Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 16.Saleh, M. Hospitals in Trump country suffer as Muslim doctors denied visas to U.S. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2017/08/17/rural-hospitals-suffer-as-pakistani-doctors-denied-visas-to-u-s/. August 17, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 17.NRMP policies and procedures for waiver requests. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Waiver-Policy.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 18.Alweis R, Khan MS, Kuehl S, et al. Internal medicine program directors’ perceptions of the “all in” Match rule: a cross-sectional survey. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):173–177. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00260.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Physicians Executive Committee of the Board of Regents. Immigration Position Statement. American College of Physicians. A position statement. 2017; https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/immigration_position_statement_2017.pdf?utm_source=acp_advocacy_in_focus_2017.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 20.Continuation of ECFMG sponsorship in non-standard clinical training. https://www.ecfmg.org/evsp/continuation-non-standard.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 21.Pomerantz RM. Applying for a sub-specialty fellowship: some tips and advice from a former program director. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2011;1(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Goyal H, Singla U, Grimsley EW, Parish D. Changes in internal medicine fellowship timeline are not favorable for applicants on J1 visa. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):e41–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen PG-C, Curry LA, Bernheim SM, et al. Professional challenges of non-U.S.-born international medical graduates and recommendations for support during residency training. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1383–1388. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823035e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao NR. “A little more than kin and less than kind”: US immigration policy on international medical graduates. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(4):329–337. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2012.14.4.pfor1-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trump’s executive order: who does travel ban affect? BBC. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38781302. Feb 10, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 26.Liptak A, Shear M. Trump’s travel ban is upheld by Supreme Court. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/26/us/politics/supreme-court-trump-travel-ban.html. June 26, 2018. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 27.Jena AB, Olenski A, Blumenthal DM, Khullar D. Trump’s immigration order could make it harder to find a psychiatrist or pediatrician. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-immigration-order-could-make-it-harder-to-find-a-psychiatrist-or-pediatrician/. February 3, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 28.Ornstein O. Trump’s executive order strands Brooklyn doctor in Sudan. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/trump-rsquo-s-executive-order-strands-brooklyn-doctor-in-sudan/ . January 31, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 29.Pisano C, Riaz H. Denying international medical graduates entry to the United States: a loss at both ends. Am J Med. 2017;130(8):878–879. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frellick M. Travel ban confusion complicates Match Day decisions. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/875858. February 15, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 31.Murphy B. AMA decries impact of travel ban, other immigration barriers. AMA News. https://wire.ama-assn.org/ama-news/ama-decries-impact-travel-ban-other-immigration-barriers. June 16, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 32.S.898—Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/898. April 7, 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 33.Hagopian A, Thompson MJ, Kaltenbach E, Hart LG. Health departments’ use of international medical graduates in physician shortage areas. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(5):241–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duke E. The critical care workforce: a study of the supply and demand for critical care physicians. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/documents/CAPNAH/files/criticalcare.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 35.Conrad 30 Waiver Program. https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/conrad-30-waiver-program. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 36.Allen, M. (2007). Doctors exploited; patients suffer, too. Las Vegas Sun. https://lasvegassun.com/news/2007/dec/23/doctors-exploited-patients-suffer-too/ December 23, 2007. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 37.Kahn TR, Hagopian A, Johnson K. Retention of J-1 visa waiver program physicians in Washington State’s health professional shortage areas. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):614–21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2ad1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opoku ST, Apenteng BA, Lin G, et al. A comparison of the J-1 visa waiver and loan repayment programs in the recruitment and retention of physicians in rural Nebraska. J Rural Health. 2015;31(3):300–9. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crouse BJ, Munson RL. The effect of the physician J-1 visa waiver on rural Wisconsin. WMJ. 2006;105(7):16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Appalachian Regional Commission J-1 Visa Waivers. Appalachian Regional Commission. https://www.arc.gov/program_areas/J1VisaWaivers.asp. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 41.Department of Veterans Affairs Handbook. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2383. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 42.Waiver based on exceptional hardship. https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/AFM/HTML/AFM/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-19459/0-0-0-19610.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 43.Waiver based on a claim of persecution. https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/AFM/HTML/AFM/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-19459/0-0-0-19719.html Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 44.Processing time for application for waiver of the foreign residence requirement. https://egov.uscis.gov/processing-times/#mainContent. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 45.Exchange Visitor Program. https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/oga/about-oga/what-we-do/exchange-visitor-program/index.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2019.

- 46.Vidyasagar D. Integrating international medical graduates into the physician-scientist pool: solution to the problem of decreasing physician-scientists in the United States. J Investig Med. 2007;55(8):406–9. doi: 10.2310/6650.2007.00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox M. Medical student indebtedness and the propensity to enter academic medicine. Health Econ. 2003;12:101–12. doi: 10.1002/hec.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaiban JT. My new country: a journey to belonging. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):498–499. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00585.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alpert JS. On immigration: welcome to America! Am J Med. 2017;130(4):383–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]