Abstract

Background

Physician behaviors are important to high-value care, and the learning environment medical students encounter on clinical clerkships may imprint their developing practice patterns.

Objectives

To explore potential imprinting on clinical rotations by (a) describing high- and low-value behaviors among medical students and (b) examining relationships with regional healthcare intensity (HCI).

Design

Multisite cross-sectional survey

Participants

Third- and fourth-year students at nine US medical schools

Main Measures

Survey items measured high-value (n = 10) and low-value (n = 9) student behaviors. Regional HCI was measured using Dartmouth Atlas End-of-Life Chronic Illness Care data (ratio of physician visits per decedent compared with the US average, hospital care intensity index, ratio of medical specialty to primary care physician visits per decedent). Associations between regional HCI and student behaviors were examined using unadjusted and adjusted (controlling for age, sex, and year in school) logistic regression analyses, using median item ratings to summarize reported engagement in high- and low-value behaviors.

Key Results

Of 2623 students invited, 1304 (50%) responded. Many reported trying to determine healthcare costs (1085/1234, 88%), but only 45% (571/1257) reported including cost details in case presentations. Students acknowledged suggesting tests solely to anticipate what their supervisor would want (1143/1220, 94%), show off their ability to generate a broad differential diagnosis (1072/1218, 88%), satisfy curiosity (958/1217, 79%), protect the team from liability (938/1215, 77%), and build clinical experience (533/1217, 44%). Students in higher intensity regions reported significantly more low-value behaviors: each one-unit increase in the ratio of physician visits per decedent increased the odds of reporting low-value behaviors by 20% (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04–1.38; P = 0.01).

Conclusions

Third- and fourth-year medical students report engaging in both high- and low-value behaviors, which are related to regional HCI. This underscores the importance of the clinical learning environment and suggests imprinting is already underway during medical school.

KEY WORDS: high-value cost-conscious care, cost-conscious care, undergraduate medical education, medical students, survey

BACKGROUND

Physician behaviors play a key role in the provision of high-value care.1,2 Value in this context has been defined as quality (care that is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered)3 divided by cost (the “Value Equation”).4 High-value care seeks to balance quality and cost with the goal of reducing harm and improving patient outcomes.5 The importance of high-value care is underscored by the Institute for Health Care Improvement Triple Aim, which encourages healthcare systems to simultaneously improve population health, enhance patient experience, and reduce per capita cost.6 Medical education thus has a responsibility to not only equip students with a nuanced understanding of value, but also support the development of high-value practice patterns aligned with this aim.7

Prior studies have demonstrated relationships between physicians’ experiences during residency and their subsequent knowledge,8 attitudes,9 behaviors,10,11 and patient outcomes12 related to high-value care. These relationships are evident as early as internship13 and persist for up to 15 years after training.10,11 This suggests residency training contributes to an imprinting process whereby learners develop practice patterns resembling those they observe in the learning environment.11,12 Studies like these highlight the importance of the graduate medical education training environment. However, comparatively little is known about the potential impact of regional practice patterns on medical student behaviors and experiences—despite the fact that their professional identity formation is already well-underway.14 Clinical clerkships, for example, represent a particularly formative time in the professional development of physicians15–17 and a time when early practice patterns begin to develop. It is thus possible that the practice patterns medical students experience in clinical settings imprint their behaviors even before entering residency training.

Practice patterns can be evaluated using measures of regional healthcare intensity (HCI) which reflects the number and types of services patients receive within a particular geographic region. Regional HCI varies widely across the USA, and this cannot be completely explained by differences in illness severity, patient preferences, socioeconomic factors, or pricing.18 Instead, this variation appears to reflect differences in practice style.18,19 Higher HCI, while costly, could increase the overall value of healthcare by improving patient outcomes. However, regions with higher spending do not consistently demonstrate better health outcomes, access to care, or patient satisfaction—illustrating that more intense care is not necessarily better care.18,20,21

OBJECTIVES

We previously demonstrated that medical students observe conflicting physician role-modeling behaviors with respect to high-value care and that students training in regions with higher HCI report observing fewer cost-conscious role-modeling behaviors than students training in regions with less intense use of healthcare resources.22 In this study, we aimed to build upon our prior work by (a) surveying medical students about their own behaviors related to value and (b) examining the relationship between student behaviors and HCI in the region of their medical school.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of all third- and fourth-year students at nine US medical schools: Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University; University of California, Davis School of Medicine; University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine; Indiana University School of Medicine; Mayo Clinic School of Medicine; Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine; University of Michigan Medical School; Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. These nine participating schools were recipients of an American Medical Association (AMA) Accelerating Change in Medical Education grant23 and have variable geographic locations, class sizes, missions, and private/public status. Each school’s institutional review board (IRB) approved or exempted this study.

Measures

Survey items measured high-value (n = 10) and low-value (n = 9) medical student behaviors. These items were developed by the study team (which includes experienced educators, content experts, and survey researchers), achieving consensus through discussion via a series of conference calls, in-person meetings, and a review of the literature to identify relevant medical student behaviors (such as the “Choosing Wisely for Medical Students” guidelines).24 Students were asked to indicate how often in the current academic year they had engaged in each behavior: 0 = never, 1 = rarely (1–2 times), 2 = sometimes (3–5 times), 3 = often (6 or more times).

As previously described,22 we measured regional HCI using hospital referral region (HRR)–level per capita data from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care’s End-of-Life Chronic Illness Care database.25 These data reflect HCI during the last 2 years of life for Medicare beneficiaries aged 67 years or older with chronic illnesses who died (decedents) in 2014. Consistent with prior studies,1,8,22 we used end-of-life data in order to compare the intensity of care provided to a cohort of comparably ill patients with a life expectancy of exactly 2 years. We elected to use regional-level data rather than hospital-level data because most students train at more than one hospital, usually in close proximity. The primary HRR for each medical school was considered to be the HRR encompassing the majority of hospitals where students from that school rotate.

We measured HCI in the primary HRR associated with each medical school using the hospital care intensity index (a composite measure of hospital days and inpatient physician visits), ratio of physician visits per decedent relative to the average number of physician visits per decedent in the USA, and ratio of medical specialty to primary care physician visits per decedent. These data were all adjusted for sex, age, race, and chronic condition (cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes with end-organ damage, dementia, liver disease, pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure).26 As previously described,22 we selected these measures of HCI based on the premise that they would be more visible to students than direct measures of spending.

Data Collection

We e-mailed a letter to students inviting them to participate in the study between January and March 2017. The letter emphasized that participation was voluntary and responses would be anonymous. Each letter included a link to the electronic survey. As an incentive for participation, students at eight of the nine participating medical schools were invited to enter a lottery to win one of 70 $250 cash cards; one school’s IRB did not allow an incentive. Up to three reminders were sent to non-responders, and informed consent was implied upon survey completion.

Data Analysis

We reported response rates using the American Association for Public Opinion Research response rate 2 (RR2) definition27 and compared the sex, age, and year in school of respondents with those of the total sampled population. Descriptive summary statistics were reported as frequencies with percentages, and we examined the internal consistency reliability of the high- and low-value behavior items using Cronbach’s alpha.

To summarize student behaviors, we calculated median item ratings for each student across the high- and low-value behavior items. Students were then dichotomized into two groups (those with a median rating of < 1 and ≥ 1) for each set of items, reflecting the natural cut-point of our 4-point behavioral frequency rating scale (0 = never, ≥ 1 = one or more times). These groups were used as dependent variables in unadjusted and adjusted (controlling for age, sex, and year in school) logistic regression models examining associations with regional HCI.

All tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We conducted sensitivity analyses excluding responses from students who were not offered an incentive for participation. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of 2623 third- and fourth-year medical students invited to participate, 1304 (50%) responded. The distributions of respondents with respect to sex, age, and year of training were similar to those of the overall sample (Table 1) and US medical students in general.28

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants: Respondents and Overall Sample (Numbers in Each Column May Not Sum to the Total N for That Column due to Missing Data. Aggregate Data for the Overall Sample Were Obtained from Institutional Records)

| Characteristics | Respondents* (n = 1304) | Overall sample (N = 2623) |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 575 (48) | 1338 (51) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| <25 | 147 (12) | 258 (10) |

| 25–30 | 939 (78) | 2053 (78) |

| 31–35 | 97 (8) | 251 (10) |

| >35 | 17 (1) | 61 (2) |

| Year of training, n (%) | ||

| Year 3 | 639 (49) | 1300 (50) |

| Year 4 | 665 (51) | 1323 (50) |

*Percentage calculations are not all based on a denominator of 1304 because of missing responses to some survey items

High-Value Behaviors

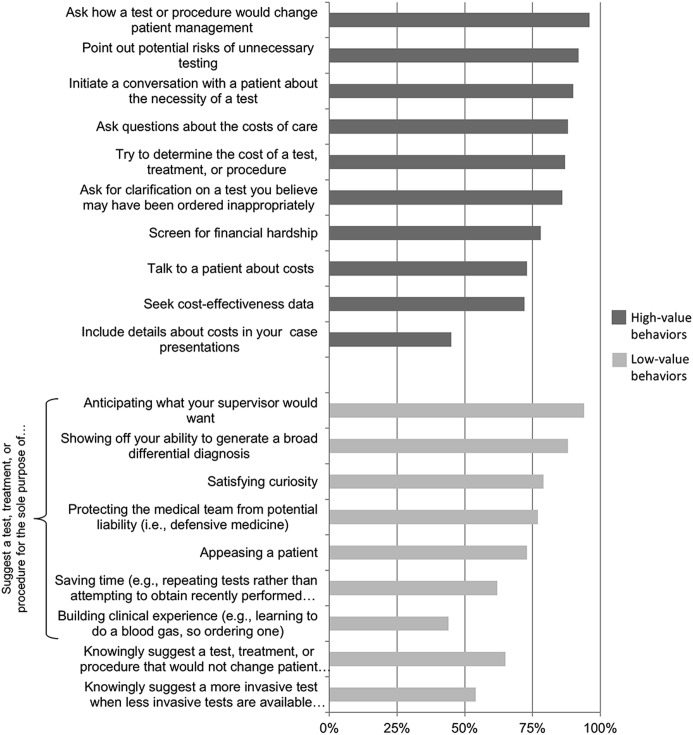

Most students reported engaging in at least one high-value behavior on clinical rotations in their current academic year (Fig. 1), such as asking their supervisor to clarify how a test or procedure would change patient management (1211/1256, 96%), pointing out potential risks of unnecessary testing (1135/1230, 92%), and initiating a conversation with a patient about whether a test is necessary (1117/1238, 90%; Table 2). The majority of students also reported asking their supervisor questions about costs of care (1085/1234, 88%), trying to determine costs (1099/1259, 87%), asking for clarification on a test they believed may have been ordered inappropriately (1062/1238, 86%), and screening for financial hardship (961/1230, 78%). However, over one-quarter of students reported never talking to patients about costs when discussing treatment options (333/1230, 27%) and never seeking cost-effectiveness data to inform proposed care plans (347/1256, 28%), while over half of students (686/1257, 55%) reported never including details about costs in their case presentations.

Figure 1.

Percentage of third- and fourth-year medical students who reported in engaging in high- and low-value behaviors on clinical rotations during their current academic year, 2017 survey.

Table 2.

High- and Low-Value Behaviors Among Third- and Fourth-Year US Medical Students, 2017 Survey

| Responses, no. (%)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely (1–2 times) | Sometimes (3–5 times) | Often (6+ times) | |

| High-value behaviors | ||||

| Ask your supervisor to clarify how a test or procedure would change patient management | 45 (4) | 185 (15) | 438 (35) | 588 (47) |

| Point out potential risks of unnecessary testing (e.g., radiation exposure, incidental findings causing undue anxiety) | 95 (8) | 298 (24) | 467 (38) | 370 (30) |

| Initiate a conversation with a patient about whether a test, treatment, or procedure is necessary | 121 (10) | 296 (24) | 433 (35) | 388 (31) |

| Ask your supervisor questions about the costs of care | 149 (12) | 407 (33) | 472 (38) | 206 (17) |

| Try to determine the cost of a test, treatment, or procedure | 160 (13) | 459 (37) | 429 (34) | 211 (17) |

| Ask for clarification on a test, treatment, or procedure you believe may have been ordered inappropriately | 176 (14) | 431 (35) | 452 (37) | 179 (15) |

| Question a patient to determine if their medical expenses were causing financial hardship | 269 (22) | 415 (34) | 389 (32) | 157 (13) |

| Talk to a patient about costs when discussing treatment options | 333 (27) | 419 (34) | 333 (27) | 145 (12) |

| Seek cost-effectiveness data to inform your proposed care plans | 347 (28) | 474 (38) | 307 (24) | 128 (10) |

| Include details about the cost of a test, treatment, or procedure in your case presentations | 686 (55) | 401 (32) | 125 (10) | 45 (4) |

| Low-value behaviors | ||||

| Suggest a test, treatment, or procedure for the sole purpose of… | ||||

| Anticipating what your supervisor would want | 77 (6) | 168 (14) | 447 (37) | 528 (43) |

| Showing off your ability to generate a broad differential diagnosis | 146 (12) | 217 (18) | 463 (38) | 392 (32) |

| Satisfying curiosity | 259 (21) | 348 (29) | 436 (36) | 174 (14) |

| Protecting the medical team from potential liability (i.e., defensive medicine) | 277 (23) | 349 (29) | 372 (31) | 217 (18) |

| Appeasing a patient | 324 (27) | 573 (47) | 272 (22) | 47 (4) |

| Saving time (e.g., repeating tests rather than attempting to obtain recently performed test results) | 461 (38) | 414 (34) | 251 (21) | 87 (7) |

| Building clinical experience (e.g., learning to do a blood gas, so ordering one) | 684 (56) | 277 (23) | 180 (15) | 76 (6) |

| Knowingly suggest a test, treatment, or procedure that would not change patient management | 432 (35) | 503 (41) | 245 (20) | 55 (5) |

| Knowingly suggest a more invasive test when less invasive tests are available (e.g., CT instead of ultrasound for suspected appendicitis) | 569 (46) | 411 (33) | 198 (16) | 54 (4) |

*Percentage calculations are not all based on a denominator of 1304 because of missing responses to some survey items; percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding; students were asked how many times during the current academic year they had performed each behavior

Low-Value Behaviors

Most students also reported engaging in at least one low-value behavior on clinical rotations in their current academic year (Fig. 1), such as suggesting a test for the sole purpose of anticipating what their supervisor would want (1143/1220, 94%) or showing off their ability to generate a broad differential diagnosis (1072/1218, 88%). Many medical students also reported suggesting a test solely to satisfy curiosity (958/1217, 79%), protect the medical team from potential liability (938/1215, 77%), appease a patient (892/1216, 73%), and save time (752/1213, 62%). Forty-four percent (533/1217) suggested a test or procedure solely to build clinical experience. Nearly two-thirds (803/1235, 65%) knowingly suggested a test that would not change patient management, and 54% (663/1232) knowingly suggested a more invasive test when a less invasive test was available (this item included an example from the Choosing Wisely for Medical Education guidelines24 illustrating the less invasive test was also appropriate in order to emphasize the focus on value).

Internal Consistency Reliability

Cronbach’s alphas for the high- and low-value behavior items were 0.82 and 0.79 respectively.

Relationship Between Regional Healthcare Intensity and Medical Student Behaviors

Measures of HCI did not significantly differ between HRRs that were (n = 9) and were not (n = 297) associated with a participating medical school (Table 3). Students training in regions with higher HCI had lower odds of reporting high-value behaviors, but these associations were not statistically significant (Table 4). Conversely, students training in higher intensity regions had higher odds of reporting low-value behaviors. These associations were statistically significant for two of our three measures of HCI in unadjusted analyses. The association with physician visits per decedent relative to the US average remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and year in school. This finding did not change when responses from students who were not offered an incentive for participation were excluded from the analysis (data not shown).

Table 3.

Regional Healthcare Intensity of Hospital Referral Regions That Were (n = 9) and Were Not (n = 297) Associated with a Participating School (the Primary Hospital Referral Region Associated with Participating Medical School Was Considered to be the Hospital Referral Region That Encompassed the Majority of Hospitals Where Students from That School Rotate)

| Regional healthcare intensity measures* | Hospital referral regions | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associated with a participating school (n = 9), mean (SD) | Not associated with a participating school (n = 297), mean (SD) | ||

| Hospital care intensity index† | 0.92 (0.23) | 0.93 (0.27) | 0.91 |

| Ratio of physician visits per decedent compared with US average | 0.93 (0.22) | 0.93 (0.25) | 1.00 |

| Ratio of medical specialty to primary care physician visits per decedent | 1.11 (0.30) | 1.11 (0.32) | 1.00 |

*Regional healthcare intensity measures are per capita data from the Dartmouth Hospital Referral Region End-of-Life Atlas (adjusted for age, sex, race, and chronic illness) and reflect care intensity during the last 2 years of life for Medicare beneficiaries age 67 years or older with chronic illnesses who died in 2014

†The hospital care intensity index represents the mean of the number of days decedents spent in the hospital and the number of physician visits they experienced as inpatients (both adjusted for age, sex, race, and chronic condition and reported as ratios compared with the US average)

Table 4.

Relationship Between Regional Healthcare Intensity and High- and Low-Value Medical Student Behaviors

| Regional healthcare intensity* | High-value student behaviors† | Low-value student behaviors† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted‡ | Unadjusted | Adjusted‡ | |||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Ratio of physician visits per decedent compared with US average | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) | 0.54 | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | 0.40 | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) | 0.02 | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | 0.01 |

| Hospital care intensity index§ | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | 0.49 | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) | 0.31 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 0.04 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 0.05 |

| Ratio of medical specialty to primary care physician visits per decedent | 0.93 (0.83–1.05) | 0.26 | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) | 0.14 | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | 0.28 | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 0.69 |

*Healthcare intensity in the hospital referral region encompassing the majority of hospitals where students at a given medical school rotate; all measures are per capita data from the Dartmouth Hospital Referral Region End-of-Life Atlas (adjusted for age, sex, race, and chronic illness) and reflect care intensity during the last 2 years of life for Medicare beneficiaries age 67 years or older with chronic illnesses who died in 2014

†Odds ratios represent the odds of reporting high- and low-value behaviors (i.e., of having a median item rating of ≥ 1 across the high- and low-value behavior survey items) per unit increase in each measure of regional healthcare intensity; odds ratios more than 1 indicate a higher odds of reporting high- or low-value behaviors; odds ratio less than 1 indicates a lower odds of reporting high- and low-value behaviors

‡Adjusted for age, sex, and year in school

§The hospital care intensity index represents the mean of the number of days decedents spent in the hospital and the number of physician visits they experienced as inpatients (both adjusted for age, sex, race, and chronic condition and reported as ratios compared with the US average)

DISCUSSION

This large, multisite survey study describes high- and low-value behaviors among third- and fourth-year medical students and demonstrates that students training in regions with higher HCI report engaging in more low-value behaviors. This highlights the importance of the undergraduate medical education learning environment and reinforces the need to foster healthcare teams and organizational systems that promote the delivery of the best care at the lowest cost.

The high-value behaviors most frequently reported by students primarily involved interactions with the healthcare team (e.g., questioning how a test will change patient management, asking a supervisor about costs of care) or interactions with patients (e.g., initiating a conversation about whether a test is necessary, screening for financial hardship). Student responses suggest they are aware of and willing to point out potential risks of unnecessary testing, make efforts to determine the costs of healthcare services, and consider the impact of costs on patients. These results are encouraging, especially given students’ more junior role on the healthcare team and relative inexperience navigating clinical settings.

However, our findings also highlight opportunities for improvement. The high-value behaviors reported least frequently by students involve incorporating cost information into patient care plans (e.g., seeking cost-effectiveness data, including cost in case presentations). These types of behaviors may thus deserve special attention and focus in undergraduate medical education curricula, especially given the numerous barriers students endorse with respect to high value.22 Such barriers may stem from the students themselves (e.g., inadequate knowledge and skills, competing priorities), from faculty on clinical rotations (e.g., suboptimal role-modeling behaviors, no expectation or reinforcement of high-value behaviors),22,29 from the local learning environment (e.g., limited or no consideration of high-value behaviors on clerkship evaluations), or from the broader healthcare system (lack of cost transparency, limited cost-effectiveness research, time pressures).30,31

Third- and fourth-year students also report engaging in numerous low-value behaviors—including those specifically identified by Choosing Wisely Canada as behaviors trainees should avoid.24 Notably, students appear to have insight into the wasteful nature of these behaviors (e.g., proposing a test for the sole purpose of anticipating what a supervisor would want; knowingly recommending a test that would not change patient management), indicating lack of awareness is not the only driver of such behaviors. Rather, students appear to be influenced by many of the same drivers of wasteful behaviors reported by residents and practicing physicians such as saving time, satisfying curiosity, appeasing patients, and protecting the healthcare team from liability (so-called defensive medicine).32–40

Other drivers of wasteful behaviors may be unique to trainees such as suggesting a test solely to anticipate what a supervisor would want, show off one’s ability to generate a broad differential diagnosis, or build clinical experience. Students are keenly aware of the impact of clerkship evaluations on the likelihood of matching into desired residency programs and may thus engage in these types of low-value behaviors to create an impression of competence or otherwise ingratiate themselves to their supervisors.40–42 Students are also sensitive to hierarchy within healthcare teams,41,43 and may engage in wasteful behaviors to avoid upsetting or being disrespectful to more senior team members.44 To address this issue, medical schools could consider faculty development strategies that encourage attending physicians to explicitly reinforce high-value behaviors and discourage low-value behaviors.32,45 Items assessing such behaviors could also be added to clerkship evaluation forms and other assessments to elevate the importance of these issues in the eyes of both faculty and students.46

The importance of the clinical learning environment is further underscored by our finding that medical students training in regions with more intense use of healthcare resources reported significantly more low-value behaviors than students training in lower intensity regions. This suggests the imprinting process is already underway during medical school. Students training in higher intensity regions also tended to report fewer high-value behaviors, though these associations were not statistically significant. The reason for this is unclear. One possibility is that formal high-value, cost-conscious care curricula are more effective at promoting high-value student behaviors than deterring low-value behaviors, leaving the latter more susceptible to imprinting by regional practice patterns. Taken together, the results of this study highlight medical schools’ obligation to train physicians capable of effectively stewarding healthcare resources on behalf of both patients and society.7,47

To address this issue, educators and educational leaders should consider ways to promote “purposeful imprinting.”11 Results of a recent systematic review suggest a three-pronged strategy of knowledge transmission, reflective practice (e.g., audits with feedback, interactive discussions), and provision of a supportive environment may be particularly effective.48 Schools could also give serious consideration to training students in a variety of environments, including those with less intense use of healthcare services. Such an undertaking may be logistically and politically challenging, but could expose students to practice settings enriched with individuals who model high-value care.

The generalizability of our results is supported by the inclusion of private and public medical schools that are distributed geographically across the USA. The characteristics of respondents were also similar to those of the total sampled population and US medical students in general, reducing concerns about bias resulting from systematic differences between respondents and non-respondents. The anonymous nature of the survey also decreases concerns about the impact of social desirability on student responses.

Nevertheless, our study has limitations. First, the nine participating schools were recruited through the AMA Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative,23 so the findings reported here may not reflect the behaviors of all US medical students. Second, our classification of medical student behaviors as high or low value, while based on the literature, may not apply in all situations or fully capture the complex trade-offs between financial and non-financial resources made in clinical practice.49 For example, repeating a test to save time, while classified as a low-value behavior for the purposes of this study, could increase the value of care in high-acuity situations when time is of the essence or if the effort required to procure recent test results would divert team members from more pressing tasks. Conversely, behaviors classified as high value for the purposes of this study could reduce the value of care if they undermine the doctor-patient relationship (e.g., talking to a patient about costs when discussion treatment options) or shift the focus to costs apart from quality (e.g., including cost details in case presentations). Such trade-offs are common but difficult to measure through formal cost analyses. Third, our survey may have omitted key behaviors that were not identified in our review of the literature. Fourth, student responses were based on recall and hence may not accurately or completely reflect their actual past behaviors. Fifth, while we sought to provide content validity for survey items (e.g., by grounding them in the Choosing Wisely for Medical Education guidelines24) and demonstrated their internal consistency reliability, additional construct validity evidence is needed to support the use of resulting scores as a measure student behaviors. Sixth, our HCI measures only reflect care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. However, prior studies have demonstrated that healthcare resource utilization among Medicare beneficiaries reflects HCI among Medicaid beneficiaries50 and commercially insured patients51 in the same region.

CONCLUSIONS

This study describes high- and low-value medical student behaviors on clinical rotations and demonstrates that students training in regions with higher HCI have higher odds of reporting low-value behaviors. Further studies are needed to determine if the association between regional HCI and low-value behaviors persists into residency and to clarify the relative impact of undergraduate versus graduate medical education experiences on physicians’ subsequent practice patterns. Strategies whereby medical education can mold the clinical learning environment and mitigate its potentially negative impacts on students also warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Regional healthcare intensity data from the End-of-Life Chronic Illness Care database were obtained from The Dartmouth Atlas, which is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Funding

This study was prepared with financial support from the American Medical Association as part of the Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative, and all participating schools received grants through this initiative (see www.changemeded.org for further details).

Data Availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data that support the findings of this study, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the American Medical Association and the relevant medical school(s).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The institutional review board (IRB) at each participating school approved or exempted this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Gonzalo reports receiving support from the Josiah Macy Foundation, American Medical Association, and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Dr. Fancher reports support from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number UH1HP29965, Academic Units for Primary Care Training and Enhancement, for $3,741,116. This information or content and conclusions of this manuscript are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. All remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content reflects the views of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of U.S. health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:813–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smoldt R, Cortese D. Pay-for-performance or pay for value? Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:210–213. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Physicians. High value care. https://hvc.acponline.org/index.html. Accessed 27 Nov 2018.

- 6.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care--What is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1253–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryskina KL, Halpern SD, Minyanou NS, Goold SD, Tilburt JC. The role of training environment care intensity in U.S. physician cost consciousness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists’ ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1640–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312:2385–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips RL, Jr, Petterson SM, Bazemore AW, Wingrove P, Puffer JC. The effects of training institution practice costs, quality, and other characteristics on future practice. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:140–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA. 2009;302:1277–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dine CJ, Bellini LM, Ciemer G, et al. Assessing correlations of physicians’ practice intensity and certainty during residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:603–9. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00092.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90:718–25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, et al. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL) Adv Health Sci Edu Theory Pract. 2014;19:721–49. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karani R, Fromme HB, Cayea D, Muller D, Schwartz A, Harris IB. How medical students learn from residents in the workplace: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89:490–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatte DJ, Piemonte N, Clark M. “I started to feel like a ‘real doctor’”: medical students’ reflections on their psychiatry clerkship. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:267–74. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of U.S. health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:813–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussey PS, Wertheimer S, Mehrotra A. The association between health care quality and cost: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:27–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leep Hunderfund AN, Dyrbye LN, Starr SR, et al. Role modeling and regional health care intensity: U.S. medical student attitudes toward and experiences with cost-conscious care. Acad Med. 2017;92:694–702. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakhani A, Lass E, Silverstein WK, Born KB, Levinson W, Wong BM. Choosing Wisely for medical education: six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016;9:1374–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. End-of-Life Chronic Illness Care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/tools/downloads.aspx?tab=40. Accessed 27 Nov 2018.

- 26.Goodman D, Esty A, Fisher E, Chang CH. Trends and variations in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with severe chronic illness. 2011. Available online at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/EOL_Trend_Report_0411.pdf. Accessed 27 Nov 2018. [PubMed]

- 27.American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 8. Lenexa: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association of American Medical Colleges. U.S. medical student applications and matriculants by school, state of legal residence, and sex, 2016-2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/321442/data/. Accessed 9 Nov 2017.

- 29.Patel MS, Reed DA, Smith C, Arora VM. Role-modeling cost-conscious care—a national evaluation of perceptions of faculty at teaching hospitals in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1294–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3242-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lesser CS, Lucey CR, Egener B, Braddock CH, 3rd, Linas SL, Levinson W. A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. JAMA. 2010;304:2732–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy AE, Shah NT, Moriates C, Arora VM. Fostering value in clinical practice among future physicians: time to consider COST. Acad Med. 2014;89:1440. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedrak MS, Patel MS, Ziemba JB, et al. Residents’ self-report on why they order perceived unnecessary inpatient laboratory tests. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:869–72. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saini V, Garcia-Armesto S, Klemperer D, et al. Drivers of poor medical care. Lancet. 2017;390:178–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan DJ, Leppin AL, Smith CD, Korenstein D. A practical framework for understanding and reducing medical overuse: conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:346–51. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. 2008;299:2789–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown SR, Brown J. Why do physicians order unnecessary preoperative tests? A qualitative study. Fam Med. 2011;43:338–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnston WF, Rodriguez RM, Suarez D, Fortman J. Study of medical students’ malpractice fear and defensive medicine: a “hidden curriculum?”. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:293–8. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.8.19045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jena AB, Schoemaker L, Bhattacharya J, Seabury SA. Physician spending and subsequent risk of malpractice claims: observational study. BMJ. 2015;351:h5516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–11. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benson MK, Donovan AK, Hamm M, Zickmund S, McNeil M. The hidden curriculum in high-value care education: resident-perceived barriers to practicing high value care in a training environment [SGIM abstract 2196705] J Gen Int Med. 2015;30(2 suppl):S274. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benson MK. Cost-consciousness in teaching hospitals. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:1035–9. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.11.ecas3-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han H, Roberts NK, Korte R. Learning in the real place: medical students’ learning and socialization in clerkships at one medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90:231–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tartaglia KM, Kman N, Ledford C. Medical student perceptions of cost-conscious care in an internal medicine clerkship: a thematic analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1491–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3324-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiggleton C, Petrusa E, Loomis K, et al. Medical students’ experiences of moral distress: development of a web-based survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:111–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c4782b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Detsky AS, Verma AA. A new model for medical education: celebrating restraint. JAMA. 2012;308:1329–30. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalo JD, Baxley E, Borkan J, et al. Priority areas and potential solutions for successful integration and sustainment of health systems science in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92:63–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: A critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:386–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-6-201109200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stammen LA, Stalmeijer RE, Paternotte E, et al. Training physicians to provide high-value, cost-conscious care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:2384–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabbatini AK, Tilburt JC, Campbell EG, Sheeler RD, Egginton JS, Goold SD. Controlling health costs: Physician responses to patient expectations for medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1234–41. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2898-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kronick R, Gilmer TP. Medicare and Medicaid spending variations are strongly linked within hospital regions but not at overall state level. Health Aff. 2012;31:948–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chernew ME, Sabik LM, Chandra A, Gibson TB, Newhouse JP. Geographic correlation between large-firm commercial spending and Medicare spending. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:131–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data that support the findings of this study, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the American Medical Association and the relevant medical school(s).