Summary

This study, part of the health promotion program of a high school in Milan (Italy), was aimed at evaluating the impact of training conferences on the awareness of STIs among adolescents aged 16-17.

Students attending the 3rd class of a Scientific and Linguistic High School in Milan (Italy) participated in this study in November 2017.

All students gave their anonymous answers on a voluntary basis in a pre-test survey, designed by psychologists and infectious diseases specialists, to test their basic knowledge, accuracy, and awareness of STIs. After a two-hour interactive conference, the students were asked to answer the post-test survey. A higher awareness of the spread and the mode of transmission of STIs, of high risk sexual and behavioural practices and prevention methods was observed in the post-test compared to the pre-test.

These findings outline both the need for sexual-health communication campaigns targeted at adolescents, who are at great risk of exposure and mostly unaware of STIs other than HIV/AIDS, and the short-term efficacy of a direct approach to the problem, guided by experts in infectious diseases and psychology. A long-term assessment of the effects of training conferences needs to be evaluated.

Keywords: Adolescent health, Sexual health, Sexually transmitted infections, Intervention strategy

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a significant hazard for individual and public health. The type of problems related to STIs ranges from acute and chronic diseases to infertility, cancer, pregnancy complications, vertical transmission with foetal disease, death. From the social and economic point of view, moreover, problems are related to loss of working ability, stigma, and individual and social economic burden [1].

Adolescents are at high risk of STIs in the industrialized world. The high prevalence of STIs in young people has been attributed to increased risky behaviours, earlier sexual debut in the last decades, multiple sexual partners, unawareness of preventive methods [2, 3]. In a report from CENSIS (2017) on the knowledge and prevention of the HPV and sexually transmitted diseases among 1000 “millennials” aged 12-24 in Italy (2017) only 15.3% admit to being highly informed about STIs [4]. The interviewed millennials seem to pay attention more to avoiding pregnancies (92.9%), rather than to protecting themselves from infections (74.5%) during sexual intercourse; frequently a misunderstanding about prevention of infections and contraception was revealed.

Moreover, the lack of knowledge of STIs, of the ways in which they are transmitted, of their symptoms, associated to fear of social stigma, to low perceived risk, to partner trust, and to confidentiality concerns, all cause delay in seeking medical services and advice for diagnosis and treatment. Consequently, there is an increased likelihood of secondary transmission and the risk of a worse outcome [5, 6].

The knowledge of risks is necessary, even if not sufficient, for safe sexual practices and sexual and reproductive health; this underscores the need to find public health intervention for the primary prevention of STI’s in young and adolescent people. At the same time, this intervention must inform correctly and must be able to change attitudes, promoting risk-reduction behaviours [7, 8].

To understand the level of STIs knowledge, sexual behaviours, and the impact of interactive conferences on STIs awareness on adolescent students, we conducted a 3-step intervention study among students attending the 3rd class of a high school in Milan (Italy).

Methods

This project was included in the health promotion program of the high school “G Marconi” in Milan (Italy) whose purposes are the information and promotion of physical and psychological health, the increase of friendship and cooperation among the different components of the school community, the promotion of self-awareness, responsibility, and social involvement, the identification and knowledge of the public health structures and opportunities.

Within the health promotion project, the Teachers’ Board and School Board approved a three-step intervention to evaluate the impact of interactive conferences on knowledge and behaviour among students aged 16-17 attending the 3rd class of the school, in order to prevent STI’s. The choice of this age was due to the fact that the average age of sexual debut among Italian adolescents has been reported to be 16 [9, 10].

Specialists in infectious diseases and psychologists designed the pre-test survey which was administered on an anonymous and voluntary basis in November 2017 to all the students attending the 3rd classes of the school by the teachers adhering to the project.

The survey was designated by Infectious Diseases specialists and psychologists and tested in previous one-shot surveys administered to adolescents and persons living with HIV/AIDS [11, 12]. The overall number of questions have been reduced, compared to the previous studies, to allow to be filled-in during a one-hour lesson time. Items were simple, short, and written in language familiar to the target people.

The survey consisted of nine multiple-choice and true-false close-ended items or open-ended items designated to test the key aspects of this study: the diffusion of STIs, the self-evaluated knowledge of STIs, the behaviours at risk, the prevention methods, the HPV vaccination, the HIV/AIDS, and, lastly, the preferential reference person(s) in case of sexual health problems.

The second step consisted of a 2-hour interactive conference held by a specialist in Infectious Diseases and by a Psychologist. Issues dealt with were: the spread, the risk, and the means of transmission of STIs, the types of behaviours at risk, the primary and secondary prevention methods, the psychological attitudes towards risky behaviour during adolescence, and lastly, the indications for responsible sexual behaviours. The conference was designed for a maximum of 40-50 people and was thus repeated three times to reach all the target students of the project.

The 3rd step consisted of a new anonymous survey, to be completed within one week of the conference, with the same range of closed and open questions included in the pre-test, and other questions aimed at evaluating changes in the students’ behavioural attitudes, changes in preferential information sources and the psychological and behavioural impact of the conference.

Finally, the students completed a post-event feedback survey to evaluate the entire project.

Results are described as descriptive statistics for the pre-and post-test data using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com. We used a two-tailed Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests according to the sample size and odds ratios were performed to test for dichotomous variables between pre- and post-test answers. The D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test was used to test if the values come from a Gaussian distribution. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the distribution of unmatched groups of non-parametric variables.

Results

The survey was administered to all the students attending the 3rd classes of the school (8 classes for a total of 178 students; 66 males and 112 females, median age 16.5 years). The response rate was 78.1% with a total of 139 pre-test cards evaluable.

All the students actively participated in the conference, asking questions, and sharing personal experiences and knowledge.

The post-test survey was completed by 100 students (70.5% of the pre-test participants). A 6 items feedback form was filled in after the end of the survey by 119/178 students (66.85%).

PRE-TEST RESULTS

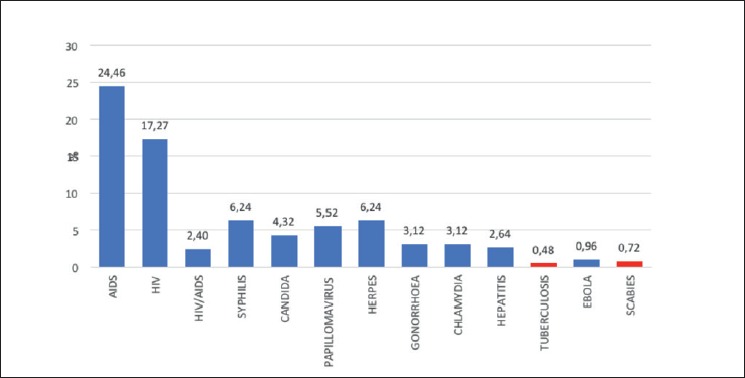

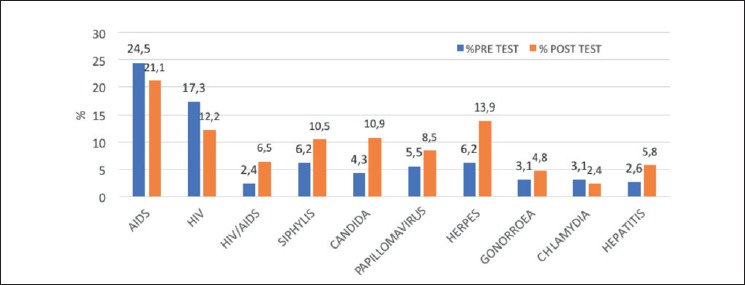

An overall 97.84% of the participants (136/139) who completed the pre-test survey declared that they were informed about STIs, and 85.1% of them (119/139) answered that STIs were very widespread in the world (questions 1 and 2). However, only a 47.5% (66/139) of them were able to complete the third question which asked the students to mention at least three STIs. Moreover, not all the diseases indicated as sexually acquired were correct (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sexually transmitted infections mentioned in the pre-test survey by 139 students for the question: Mention at least 3 STIs. Incorrect answers in red.

Knowledge of STIs was mostly limited to the HIV and AIDS infection/disease which, considered together, represented 41.73% of the STIs indicated by the students; every other STI was mentioned in less than 7% of the pre-test cards.

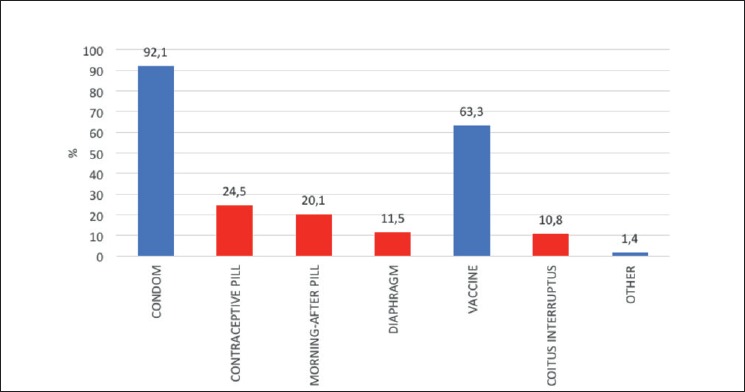

Question 4 (according to you, which of the following methods are useful in the prevention of sexually transmitted infections?) was made up of a closed question with several correct and incorrect possible answers to choose from, and an open part, leaving the possibility to add some other options. The use of a condom was indicated by 92.09% of participants as a reliable method for the prevention of STIs; vaccines were indicated by 63.31% of the participants as methods useful for STI prevention. However, among the preventive methods to avoid STIs, also the contraceptive pill (24.46%) the morning-after pill (20.14%), the diaphragm (11.51%) and the coitus interruptus (10.79%) (Fig. 2) were wrongly indicated.

Fig. 2.

STI prevention methods indicated in the pre-test survey for the question: According to you, which of the following methods are useful for the prevention of the sexually transmitted infections? Incorrect answers in red.

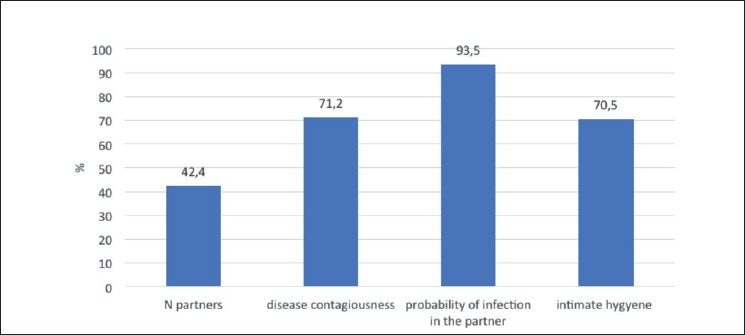

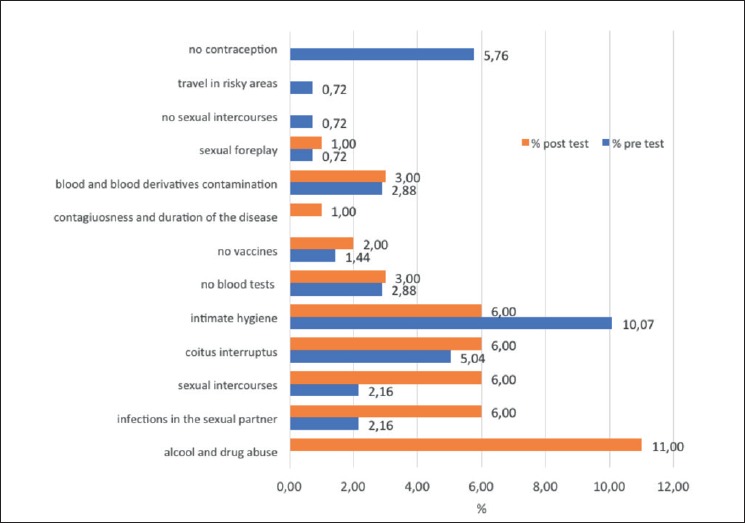

Only 42.45% of the students interviewed indicated the number of sexual partners as an important risk factor for disease transmission. Intimate hygiene, probability of infection in the sexual partner, and contagious properties of the diseases were the most important factors implicated in STI transmission, according to the answers to Question 5 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Conditions involved in STI transmission indicated in the pre-test survey for the question: Which of the following conditions are involved in STI transmission?

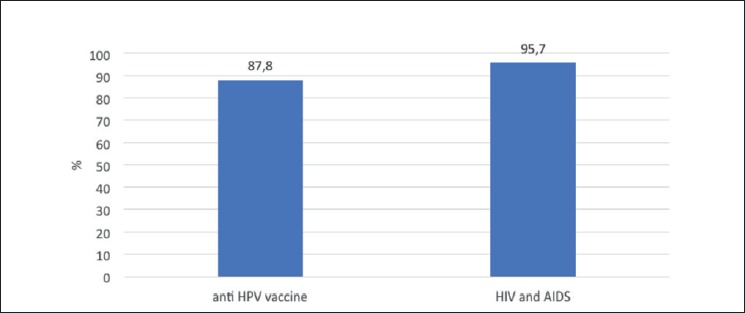

Almost all the students declared that they were informed about HIV/AIDS, and the awareness of an HPV vaccine was slightly lower (87.77%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of students who declared knowledge of HIV/AIDS and HPV vaccine answering the questions: Have you ever heard about HPV vaccine and AIDS or HIV?

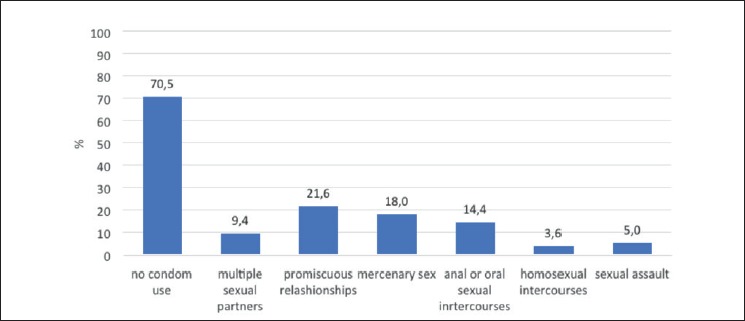

The answers to the open question 8 (List at least three sexual behaviours at risk for STIs) show that a high proportion of adolescents (70.5%) are aware that sexual intercourse without condom protection can be considered at risk, but only a very low proportion of them indicated other risky sexual practices (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pre-test survey results for the question: List at least 3 sexual behaviours at risk for STIs.

Lastly, we asked students to list, in order of priority, who they would turn to if they suspected a sexually transmitted disease. We assigned a score according to the order of preference: 1 to the first choice and 7 to the last choice. In the pre-test, the main reference for adolescents who suspect a STI were the parents (score 2.0) followed by the family doctor (score 2.6), friends (score 3.6) or hospital (score 3.6) and local health facilities (ASL) (score 4.2); web-based information, such as internet sites or chats are the last options with scores of 4.6 and 6.1 respectively.

COMPARISON BETWEEN PRE-AND POST-TEST SURVEYS

The proportion of students who declared that they were informed about STIs raised from 97.84% (136/139 students) of the pre-test to 99% (99/100 students) in the post-test survey but the difference was not significant (χ2 test p = 0.50). More evident is the increase in the proportion of students who become aware of the wide diffusion and high prevalence of STIs in the world from 85.1% (119/139 students) to 98% (98/100 students) (χ2 test p = 0.001).

The ability to list 3 STIs increased from 48.2% (67/139) to 88% (88/100) (χ2 test p < 0.0001) with a change in the type of STIs listed. The range of STIs widened, with a shift toward non-HIV STIs (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparison between pre- and post-test answers to the question:Mention at least 3 STIs.

To calculate the proportion of STIs appropriately identified as sexually transmitted, we considered as denominator the number of possible correct answers (3 for each form filled): while in the pre-test survey we found several diseases wrongly qualified as sexually transmitted, the proportion of STIs appropriately identified as sexually transmitted rose in the post-test survey from 76.26% (318/417) to 97.96% (288/294) (χ2 test p < 0.0001).

The effect of the training conference on the knowledge of the preventive methods to decrease the risk of STI acquisition is controversial. We found a significant increase in the awareness of the preventive effect of some vaccines against STIs (from 63.3% to 87%) but the idea that the contraceptive pill, the morning-after pill, the diaphragm, and the coitus interruptus could have some preventive properties, even if significantly reduced, still persists in the post-test survey (Tab. I).

Tab. I.

Comparison of the pre-test answers (available for 139 students) and post-test answers (available for 100 students) related to preventive measures, risk factors and risky behaviours for STIs.

| Pre-test N - (%) |

Post-test N - (%) |

χ2 test | Odds ratio* (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive measures | ||||

| Condom | 128 (92.1) | 95 (95.0) | 0.37 | 1.63 (0.55-4.86) |

| Vaccines | 88 (63.3) | 87 (87.0) | < 0.0001 | 3.88 (1.97-7.64) |

| Contraceptive pill | 34 (24.5) | 14 (14.0) | 0.046 | 0.5 (0.25-0.99) |

| Morning after pill | 28 (20.1) | 5 (5.0) | 0.0008 | 0.21 (0.08-0.56) |

| Diaphragm | 16 (11.5) | 7 (7.0) | 0.24 | 0.58 (0.23-1.46) |

| Coitus interruptus | 15 (10.8) | 8 (8.0) | 0.19 | 0.47 (0.72-1.77) |

| Others | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | / | / |

| Risk factors for transmission | ||||

| N of partners | 59 (42.4) | 96 (96.0) | < 0.0001 | 32.54 (11.3-93.5) |

| Disease contagiousness | 99 (71.2) | 92 (92.0) | < 0.0001 | 4.65 (2.07-10.45) |

| Probability of infection in the partner | 130 (93.5) | 99 (99.0) | 0.04 | 6.85 (0.85-55.0) |

| Intimate hygiene | 98 (70.5) | 62 (62.0) | 0.17 | 0.68 (0.39-1.18) |

| Risky sexual behaviours | ||||

| No condom use | 98 (70.5) | 72 (72.0) | 0.80 | 1.08 (0.61-1.9) |

| Multiple sexual partners | 13 (9.4) | 37 (37.0) | < 0.0001 | 5.69 (2.82-11.47) |

| Promiscuous relationships | 30 (21.6) | 29 (29.0) | 0.19 | 1.48 (0.82-2.68) |

| Mercenary sex | 25 (18.0) | 6 (6.0) | 0.0065 | 0.29 (0.11-0.74) |

| Anal or oral sexual intercourses | 20 (14.4) | 10 (10.0) | 0.31 | 0.66 (0.29-1.48) |

| Homosexual intercourses | 5 (3.6) | 2 (2.0) | 0.47 | 0.55 (0.10-2.88) |

| Sexual assault | 7 (5.0) | 0 | 0.022 | 0.09 (0.00-1.56) |

* Odds ratio with 95% Confidence interval in the post-test compared to the pre-test answers. In bold statistically significative differences between the two tests.

We found a statistically significative increased consciousness of the importance of the number of sexual partners in infection transmission (χ2 test p < 0.0001). The identification of this parameter as risk factor for STIs transmission increased by 32-fold in the post test. The role of disease contagiousness (which is the sum of intrinsic disease characteristics, time of diagnosis and treatment, efficacy of treatment) is better understood, given the increase of this factor from 71.22% to 92% in the pre- and post-test survey respectively (χ2 test p < 0.0001, OR 4.65). Among the risk factors for STIs transmission, a slight increase of the probability of infection in the partner was observed, while the role attributed to the intimate hygiene decreased in the post-test. Although we found better knowledge of STIs, of preventive measures, of means of STI transmission, we found a stable attitude in considering sexual behaviours at risk. The answers to the question on risky sexual behaviours reported in Table I continue to attribute the highest risk to sexual intercourses without condom protection.

A high risk was attributed in the post-test also to multiple sexual partner which rose from 9.35% to 37% and a lower risk was attributed to mercenary sex which decreased from 18% to 6%.

No significative differences were observed in the consciousness of the disease called HIV/AIDS and of the anti HPV vaccine already high in the pre-test survey.

The analysis of the answers given in the open section of the question on risky behaviours (Fig. 7) shows several misconceptions in the pre-test: no use of contraception, travel in “risky areas”, no sexual intercourses are reported as sexual risky behaviours. In the post-test survey, 11% of participants recognized alcohol and drug abuse as risky factors for a reduced attention to safe sex practices never mentioned in the pre-test.

Fig. 7.

Sexual risky behaviour indicated in the open question in pre- and post-test.

Parents, who were the main reference in the case of a suspected STI, fell in second place in the post-test (Mann-Whitney t test between pre and post-test score p = 0.0002). After the conference, the main reference for a suspected STI became the family doctor (Mann-Whitney t test between pre-test score and post test score p = 0.04) (Tab. II). In the post-test survey, we also asked students their opinion on who should give information on STIs; we assigned a score according to the order of preference: 1 to the first choice and 6 to the last choice. The ranking result is reported in Table II.

Tab. II.

Order of reference participants would turn to in case of suspected sexually transmitted infection in the pre- and post-test survey (a), and ranking of people and groups who are expected to be able to give information on STIs (b).

| a | Order of reference in case of suspected STI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° | 2° | 3° | 4° | 5° | 6° | 7° | |

| Pre-test | Parents (2.0) |

Family doctor (2.6) |

Hospital (3.6) |

Friends (3.6) |

Primary health care services (4.2) |

Web based information (4.6) |

Chat (6.1) |

| Post-test | Family doctor (2.2) |

Parents (2.8) |

Hospital (3.5) |

Primary health care services (3.7) |

Friends (4.2) |

Web based information (5.1) |

Chat (6.0) |

| b | Ranking of people able to give informations on STIs | ||||||

| 1° | 2° | 3° | 4° | 5° | 6° | ||

| Post-test | Experts in STIs (2.0) |

Teachers (3.1) |

Parents (3.2) |

Media (3.2) |

Partner (4.4) |

Friends (4.6) |

|

Personal feelings, suggestions, and general feedback.

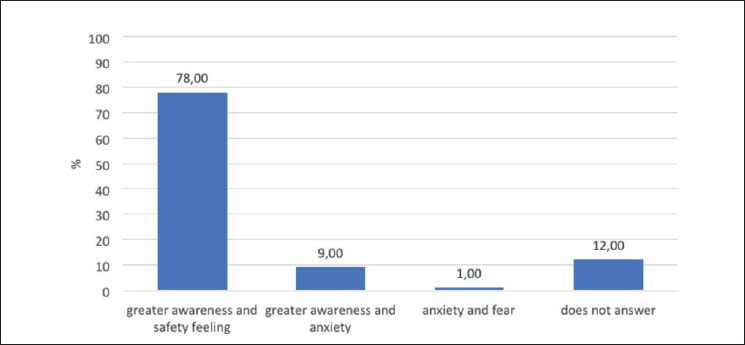

Lastly, we analysed the comments on the training conference, the free suggestions left and the feedback form.

Greater consciousness and awareness of STIs, associated with a feeling of greater protection against infections is perceived by 78% of participants (78 students); 9% of them (9 students), however, reported consequent anxiety and discomfort (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Personal feeling on the whole conference experience.

Suggestions were made by 11% (11 students) of the participants in the post-test survey. In 8/11 cases (72.7%) a positive comment was made, in 2/11 cases (18.2%) a more detailed discussion on the topic was claimed. In 1/11 case (9.1%) we found an appeal to reassure adolescents in order to avoid transmitting fear rather than awareness.

The scores, scaled from 1 to 5 in the feedback survey, filled-in by 119 individuals, are reported in Table III.

Tab. III.

Score obtained in the feedback survey filled in by 119 participants in a scale from 1 to 5 (with 5 as the best score).

| Question | Score value (mean) |

|---|---|

| Were these topics interesting to you? | 3.95 |

| Did the speakers explain these topics clearly? | 3.96 |

| Were these topics treated exhaustively? | 3.84 |

| Did you have time and opportunity to ask information and to say your opinions and doubts? | 3.96 |

| Was the organization of the meeting suitable both regarding the presentation and the instruments used? | 3.73 |

Discussion and conclusions

This is an interventional study which focused on the evaluation of the potential impact of training conferences on the knowledge and awareness of STIs in adolescent students. It was performed among students aged 16-17 attending a high school in Milan, Italy as part of a health promotion program.

Results outline the scarce basic knowledge of STIs among students. There is a high level of awareness of HIV/AIDS, but a low level of awareness of other STIs, their diffusion, means of transmission, prevention methods, behaviours at risk. These findings agree with other reports in literature about student’s STI knowledge and awareness [9, 13-15] and suggest the need for targeted information programs.

A two-hour interactive conference held by Infectious Diseases and Psychology specialists seem to improve STI knowledge significantly in the short-term, even if several misconceptions persist.

It is noteworthy that only a very low proportion of participants declared that the conference led to anxiety or fear. This could be due to the fact that psychological consideration of behaviour at risk in adolescence was discussed during the conference: its positive value for the process of personal growth, and the importance of dealing with risk in a controlled and conscious way.

Although this study adds some insights into the sexual health knowledge and STI awareness in adolescent students and on the possible educational role of interactive specifically targeted conferences on STIs, there are several limits to be noted. First, the relatively low number of adolescents in a single high-school included in the analysis could be not representative of the entire population aged 16-17 years. Secondly, the anonymous participation to the survey, prevented us to perform a matched comparison of answers in the pre- and post-test survey.

Moreover, we did not perform a second control survey to verify the long-term effectiveness of the intervention on knowledge and awareness.

Lastly, we did not test how and to what extent this intervention could be translated into behaviour changes.

The adolescents’ sexual health education plays a key role in STI prevention; school is the primary place to reach a large part of them. Collaboration between health specialists and teachers can prove to be extremely important in order to obtain successful behaviour change interventions and STIs control.

Figures and tables

Acknowledgements

We thank Marconi High School Board and the Headmistress of the school, Prof.ssa Donata Graziella Scotti, for having authorized the project as part of the health promotion program of the school.

Funding sources: this research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

GO conceived and coordinate the study, designed the pre-test and post-test surveys, held the interactive conferences, evaluated the results, and wrote the manuscript. MC contributed substantially to the conception and the design of the study, participated to the design of the pre- and post-test surveys, held the interactive conferences, and contributed substantially to the manuscript writing. SI organized and coordinated the whole intervention within the health promotion project of the school. GPJ revised the manuscript and provided English language editing.

References

- [1].World Health Organization (WHO). Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections, 2016-2021. Available online at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246296/?sequence=1

- [2].Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, Su J, Xu F, Weinstock H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:187-93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gullette DL, Lyons MA. Sensation seeking, self-esteem, and unprotected sex in college students. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2006;17:23-31. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Conoscenza e prevenzione del papillomavirus e delle patologie sessualmente trasmesse tra i giovani in Italia. CENSIS, Roma, 8 Febbraio 2017. Available online at: https://www.key4biz.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Rapporto-Censis_2016_Millennials_e_vaccinati_8_febbraio_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chacko MR, Sternberg K, Velasquez MM, Wiemann CM, Smith PB, Di Clemente R. Young women’s perspective of the pros and cons to seeking screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: an exploratory study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008;21:187-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tilson EC, Sanchez V, Ford CL, Smurzynski M, Leone PA, Fox KK, Irwin K, Miller WC. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 2004;4:1 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lauszus FF, Nielsen JL, Boelskifte J, Falk J. Sexual practice associated with knowledge in adolescents in ninth grade. Dan Med J 2012;59:A4474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull 1992;111:455 doi.apa.org [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Panatto D, Amicizia D, Trucchi C, Casabona F, Lai PL, Bonanni P, Boccalini S, Bechini A, Tiscione E, Zotti CM, Coppola RC, Masia G, Meloni A, Castiglia P, Piana A, Gasparini R. Sexual behaviour and risk factors for the acquisition of human papillomavirus infections in young people in Italy: suggestions for future vaccination policies. BMC Public Health 2012;12:623 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Orlando G, Fasolo M, Mazza F, Ricci E, Esposito S, Frati E, Zuccotti GV, Cetin I, Gramegna M, Rizzardini G, Tanzi E;VALHIDATE study group. Risk of cervical HPV infection and prevalence of vaccine-type and other high-risk HPV types among sexually active teens and young women (13-26 years) enrolled in the VALHIDATE study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:986-94. doi: 10.4161/hv.27682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Orlando G, Campaniello M, Citriniti TS, Fasolo MM, Beretta R. Valutazione del livello di conoscenza delle malattie a trasmissione sessuale (MTS) in un campione di adolescenti milanesi. 7° Congresso Nazionale SIMIT, Bergamo 19-22 novembre 2008 (Oral presentation 045). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Orlando G, Campaniello M, Beretta R, Fasolo MM, Bardzki AM, Molinari L, Citriniti TS, Borreggio G, Pellegrini M, Rizzardini G. Knowledge on sexually transmitted infections of HIV-infected patients. 19th ECCMID, Helsinki, Finland 16-19 may 2009. Poster N 1279. Clinical Microbiology and infection 2009;15:S349-S350. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cassidy C, Curran J, Steenbeek A, Langille D. University students’ sexual health knowledge: a scoping literature review. Can J Nurs Res 2015;47:18-38. doi: 10.1177/084456211504700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tilmann von Rosen F, Juline von Rosen A, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Damberg I, Tinnemann P. STI Knowledge in Berlin adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:110 doi:10.3390/ijerph15010110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Samkange-Zeeb FN, Spallek L, Zeeb H. Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health 2011;11:727 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]