Dear Sirs,

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a late-onset disease caused by motor neuron degeneration with no effective therapies [1]. Approximately, 5–10 % of cases are familial (FALS), whereas the majority of patients are sporadic (SALS). ALS exhibits an extreme genetic heterogeneity and at least 25 genes are associated to familial forms, with C9orf72 and SOD1 representing the most common mutated genes [2].

Recently, by performing an exome-wide, case-control burden analysis of rare variant in FALS index cases, we identified an excess of patient variants (7/635) in TUBA4A gene, encoding for a member of the alpha-tubulin family [3]. Functional studies showed that TUBA4A mutations exert deleterious effects on microtubule network and dynamics in primary motor neurons. By extending TUBA4A genetic analysis to 1355 sporadic cases of different origin, we identified one additional variant (p.Gly43Val) with a mild effect on microtubule cytoskeleton in an Italian patient [3].

These data led us to further assess the involvement of TUBA4A gene in sporadic cases by analyzing a large cohort of 1106 SALS of Italian origin, including 43 patients with concomitant fronto-temporal dementia (ALS-FTD).

Our mutational screening revealed the presence of four novel heterozygous variants in four patients (Table 1). Three were missense mutations (p.Val7Ile; p.Thr349Ser and p.Asp438Asn) which determined amino-acid substitutions at evolutionarily conserved residues (“Online Resource”), while the fourth variant (c.226+4A>G) was a donor splice site mutation in in-tron 2. These variants were absent in 3960 in-house Italian controls as well as in 7595 individuals from public databases (1000 Genome project and NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project). Other synonymous variants and previously reported polymorphisms were also detected (“Online Resource”).

Table 1.

TUBA4A variants identified in SALS Italian patients

| Sample ID | Sex | Age at onset | Disease duration | Site of onset | Cognitive impairment | Variant | SIFT prediction | Mutation taster | PolyPhen2 prediction | BDGP Wild type/mutant | ASSP wild type/mutant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1103 | M | 57 | 14 years | Spinal | No | IVS2+4A>G c.226+4A>G |

n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.76/- | 10.264/7.612 |

| P937 | F | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | p.Val7Ile c.19C>A |

Tolerated | Disease causing | Benign | n/a | n/a |

| N5214 | F | 62 | 12 months | Bulbar | No | p.Thr349Ser c.l045A>T |

Damaging | Disease causing | Possibly damaging | n/a | n/a |

| N6287 | M | 59 | 26 months | Bulbar | Yes | p.Asp438Asn c.1312G>A |

Damaging | Disease causing | Benign | n/a | n/a |

BDGP Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project: Splice Site Prediction by Neural Network, ASSP Alternative Splice Site Predictor, n/a not available, - the constitutive splice site is not recognized in mutant sequence

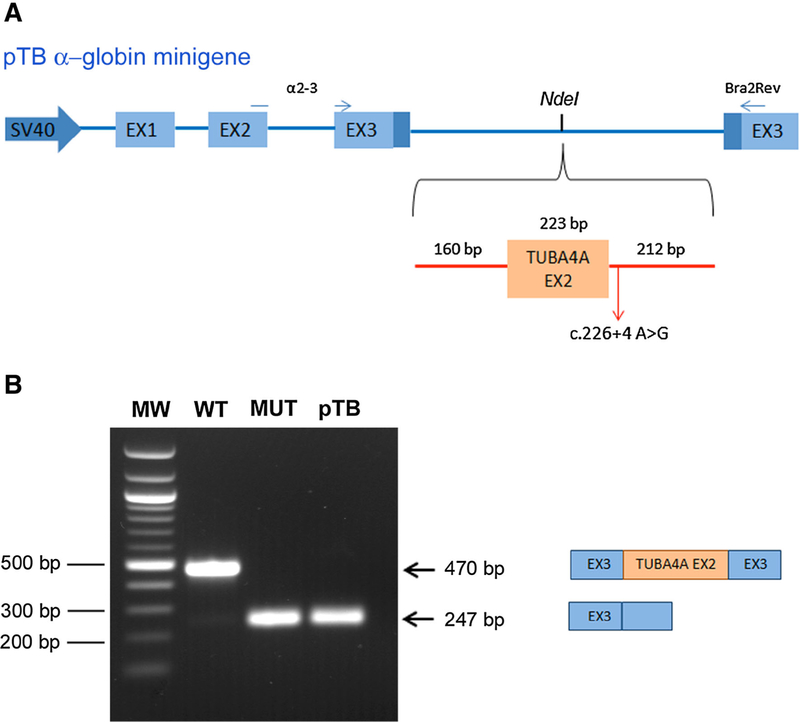

In silico analysis predicted a possibly damaging effect of three novel missense mutations on TUBA4A protein and of the c.226+4A>G variant on exon 2 splicing (Table 1). We proved that this variant abolished the original donor splice site resulting in exon 2 skipping using a minigene splicing assay (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Minigene splicing assay for TUBA4A intronic variant c.226+4A>G. a Schematic representation of the pTB minigene system, in which light blue boxes represent a-globin exons and thick lines are introns. TUBA4A exon 2 (orange box) along with part of flanking introns was subcloned into the NdeI restriction site of the pTB vector. The primers a 2–3 and Bra2rev, used for RT-PCR analysis, are indicated as thin blue arrows in the pTB map. b HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) TUBA4A hybrid minigene, or with the empty vector (pTB), as indicated. The size of the transcripts, with TUBA4A exon 2 inclusion or exclusion, is indicated on the right side of the gel. The molecular weight marker (100pb DNA ladder, Life Technologies) is reported

All patients carrying TUBA4A mutations had a classical ALS phenotype, with upper and lower motor neuron signs (full clinical information is listed in “Online Resource”). Notably, one case also showed mild cognitive impairment, adding further evidence that TUBA4A mutations in ALS may be associated to the ALS-FTD continuum, as previously observed [3].

In conclusions, here we report the identification of novel TUBA4A variants with predicted deleterious effects on protein function in a series of SALS Italian patients. Although functional studies are needed to determine their pathological effect on microtubule network, our results further support the role of TUBA4A gene in ALS. Together with PFN1 gene [4], mutations in TUBA4A indicate that defects in neuronal cytoskeleton architecture represent one of the pathogenic mechanisms triggering neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the Italian ALS patients participating in the study and their caregivers for support.

This work was partially supported by AriSLA (project NOVALS 2012 to N.T., V.S., C.G., V.P., C.T., B.C., J.L.; project RepeatALS to S.D., L.C., L.M.), ASLA onlus (to G.S.), the Eurobiobank and Telethon Network of Genetic Biobanks (GTB12001D to G.S.) and cofinanced with the support of “5 × 1000”—Healthcare Research of the Ministry of Health to C.C., C.G., C.T., V.P., B.C., N.T. J.L and V.S.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7739-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflicts of interest The authors have no competing interest.

Ethical standard On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that we acted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent Each patient gave informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

References

- 1.Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN (2009) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marangi G, Traynor BJ (2014) Genetic causes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: new genetic analysis methodologies entailing new opportunities and challenges. Brain Res S0006–8993:01361–01364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith BN, Ticozzi N, Fallini C et al. (2014) Exome-wide rare variant analysis identifies TUBA4A mutations associated with familial ALS. Neuron 84:324–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu CH, Fallini C, Ticozzi N et al. (2012) Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 488:499–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.