Abstract

Objective:

This study examined a range of indicators of alcohol’s harm to others (AHTO) among U.S. adults and assessed sociodemographic and alcohol-related risk factors for AHTO.

Method:

The data came from 8,750 adult men and women in two parallel 2015 U.S. national surveys conducted in English and Spanish. Both surveys used computer-assisted telephone interviews and two-stage, stratified, list-assisted, random samples of adults ages 18 and older.

Results:

One in five adults experienced at least one of ten 12-month harms because of someone else’s drinking. The prevalence of specific harm types and characteristics differed by gender. Women were more likely to report harm due to drinking by a spouse/partner or family member, whereas men were more likely to report harm due to a stranger’s drinking. Being female also predicted family/financial harms. Younger age increased risk for all AHTO types, except physical aggression. Being of Black/other ethnicity, being separated/widowed/divorced, and having a college education without a degree each predicted physical aggression harm. The harmed individual’s own heavy drinking and having a heavy drinker in the household increased risk for all AHTO types. The risk for physical aggression due to someone else’s drinking was particularly elevated for heavy drinking women.

Conclusions:

Secondhand effects of alcohol in the United States are substantial and affected by sociodemographics, the harmed individual’s own drinking, and the presence of a heavy drinker in the household. Broad-based and targeted public health measures that consider AHTO risk factors are needed to reduce alcohol’s secondhand harms.

Alcohol use ranks among the notable modifiable risks to health worldwide (Forouzanfar et al., 2016). Excessive drinking adversely affects not just drinkers themselves, but also their partners and families (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017, 2018a), costing people other than the drinker time, money, and peace of mind (Laslett et al., 2017). Given the impact on other people’s physical and mental health (Greenfield et al., 2016; Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017) and quality of life (Livingston et al., 2010), the societal costs of alcohol are estimated to be twice those incurred by drinkers to themselves (Laslett et al., 2010). Alcohol’s harm to others (AHTO) is, therefore, a significant public health issue.

Risk factors for alcohol’s harm to others

As with heavy drinking, AHTO occur in a socioecological context (Freisthler et al., 2008). Individual-level characteristics, such as gender and income, interact with drinking context (Kaplan et al., 2017a) and neighborhood conditions (Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014) to influence exposure to harm from others’ drinking.

Sociodemographics.

Victims and problem drinkers often are both young and single (Fillmore, 1985). Women more frequently report marriage and family harms and financial impacts from other drinkers (Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014), whereas men are likely to be assaulted by other drinkers and to be passengers of drunk drivers (Greenfield et al., 2009; Laslett et al., 2010). Being unmarried, unemployed, and of low income increase AHTO risk, even with age and neighborhood socioeconomic status accounted for (Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014).

Alcohol-related characteristics.

An individual’s own drinking can increase risk for AHTO, such as being assaulted by another drinker (Laslett et al., 2011). Alcohol users are more likely to be routinely exposed to other heavy drinkers in certain drinking contexts such as bars or parties (Kaplan et al., 2017a).

Population-level data are critical for developing targeted and cost-effective public health efforts to reduce AHTO among those most at risk (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2018b). Prior research has included mostly college student samples or those from limited geographical regions, with more recent studies focusing on population samples. Gaps in the scientific knowledge about AHTO in the United States include lack of national population prevalence data on many types of AHTO and on risk factors for various AHTO types. For instance, it is unknown whether the risk due to an individual’s own drinking differs for marital problems versus having one’s property vandalized by someone else who has been drinking. Having a heavy drinker in one’s life, particularly in the same household, is another important alcohol-related contextual risk factor for AHTO (Stanesby et al., 2018) that has been under-studied in the United States, especially for different AHTO types.

The present study used 2015 U.S. national population survey data to (a) assess prevalence of a comprehensive range of AHTO among adult men and women and (b) examine associations of AHTO with sociodemographics and alcohol-related characteristics, including the harmed individual’s own drinking and the presence of a heavy drinker in the household (HDHH).

Method

Sample

We used data from two U.S. surveys conducted in parallel, the 2015 National Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey (NAHTOS; n = 2,830) and the 2015 National Alcohol Survey (NAS; n = 7,071). Both surveys used computer-assisted telephone interview protocols designed to facilitate co-analysis and included representative samples of adults ages 18 and older, with oversamples of Black/African American (henceforth, Black) and Hispanic/Latino (henceforth, Hispanic) respondents selected from areas with at least 40% Black and/or Hispanic residents. Both surveys used an identical dual-frame sampling design, drawing two-stage, stratified, list-assisted, random samples of adults from landline telephone households and cellular (mobile) phone users. Surveys were conducted in English and Spanish from April 2014 to June 2015. The institutional review boards of the Public Health Institute and ICF (the fieldwork agency) approved all study materials, survey protocols, and procedures.

Data collection protocols

A maximum of 6 attempts were made to reach cell phone respondents, with 15 attempts made for landline households. Calls at varying times of the day and days of the week maximized the likelihood of reaching eligible respondents. Interviewers confirmed that cell phone users were in a safe situation, that is not driving or in situations with limited privacy. Interviewers ascertained verbal consent, and participants received $10 or $20 for completing the survey interview, the higher amount when more screening was required to recruit an eligible participant.

Average interview lengths were 29 and 37 minutes for abstainers, and 34 and 50 minutes for drinkers in the NAHTOS and NAS, respectively. The combined survey cooperation rate was 59.8%, considered typical for national telephone surveys in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2012). Regression analysis of random subsamples of NAS respondents showed no significant relationship between a sub-sample’s completion rate and the proportion of drinkers in either the cell- or landline-phone samples (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017).

The present analysis focused on an analytic sample of 8,750 respondents who answered the 12-month questions on AHTO experiences. Of these, 40.7% were men, 20.7% were Hispanic, 51.9% were non-Hispanic White (henceforth White), 22.0% were Black, and 5.5% reported another ethnicity (Asian, Pacific Islander, or Native American) or were multiracial. About a third (37.9%) had a high school diploma or less education; 50.4% and 25.5%, respectively, were currently employed and retired; and 24.6% reported incomes below the 2015 poverty line.

Measures

AHTO measures included two sets of items. The first set contained 10 items on harm in the last 12 months caused by “someone who had been drinking,” comprising (a) being harassed, bothered, called names, or otherwise insulted; (b) feeling threatened or afraid; (c) having clothing or belongings ruined; (d) having house, car, or other property vandalized; (e) being pushed, hit, or assaulted; (f) being physically harmed; (g) being in a traffic accident; (h) being a passenger in a vehicle with a drunk driver; (i) having family problems or marriage difficulties; and (j) having financial trouble. These items have been used in prior U.S. surveys (Greenfield et al., 2016; Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014; Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017) and studies outside the United States (Laslett et al., 2011). We created an indicator of any past-year AHTO (one or more of the 10 harms) and five specific AHTO type indicators that collapsed sets of two items with similar content as follows: harassment/threats (a–b), property ruined/vandalism (c–d), physical aggression (e–f), driving-related (g–h), and family/financial (i–j) harm caused by someone who had been drinking.

Respondent who reported an AHTO answered a second set of questions on characteristics of each harm reported, identifying perpetrators (spouses/partners, girlfriend/boyfriend, family members, friend or coworker, strangers) and the frequency of harm in the past year.

Sociodemographic variables were used for descriptive analyses and were controlled for in multivariate analyses. They included age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44 vs. 45 years and older), race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, other vs. White), marital status (separated/divorced/widowed, never married vs. married/cohabitating), income (below poverty level vs. not below poverty level) based on a standard measure involving number of dependents in the family (Greenfield et al., 2015), education (high school graduate or less and some college vs. college graduate), and employment status (employed vs. other, comprising unemployed, retired, homemaker, disabled, or had never worked).

Alcohol-related characteristics.

The respondent’s own drinking status was categorized as abstention, non–heavy drinking, and heavy drinking in the past year (Greenfield, 2000). Heavy drinking was defined as exceeding per day limits specified in low-risk drinking guidelines (Dawson et al., 2012), that is four or more drinks for women and five or more drinks for men on any single day, at least monthly in the past year.

HDHH was assessed using two items from the NAHTOS only: “Thinking about the last 12 months, can you think of anyone among the people in your life—your family, friends, co-workers or others—who you would consider to be a fairly heavy drinker or someone who drinks a lot sometimes?” Follow-up items determined the respondent’s relationship to the heavy drinker and whether the heavy drinker lived in the same household at any time in the last 12 months. A dichotomous variable was created for having an HDHH versus not.

Family history of alcohol problems was determined by a positive response to either of two questions: “When you were growing up, that is, during your first 18 years, did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or an alcoholic?” and “Have any of your blood relatives ever been a problem drinker or an alcoholic?” Family history increases risk for alcohol-related problems (Warner et al., 2007) and for reporting harms from others’ drinking (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017).

Data analysis

Sampling weights were used in all analyses to adjust for probability of selection and nonresponse, thus approximating U.S. population representativeness at the time of data collection. We normalized population weights to the total analytic sample size of each survey.

We estimated the population prevalence of any AHTO and of the five AHTO types separately for men and women in bivariate analyses. We then examined prevalence among sociodemographic subgroups, including groups defined by the respondent’s own drinking status. Two sets of logistic regression models were estimated for each of the five AHTO types to assess associations of AHTO with the respondent’s own drinking status (Model 1) and with having an HDHH (Model 2, NAHTOS only). These models tested interactions of gender with the respondent’s own drinking for each AHTO type. When the interaction of gender with the respondent’s own drinking was not statistically significant, parsimonious main effects models were estimated. All analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Prevalence of alcohol’s harm to others

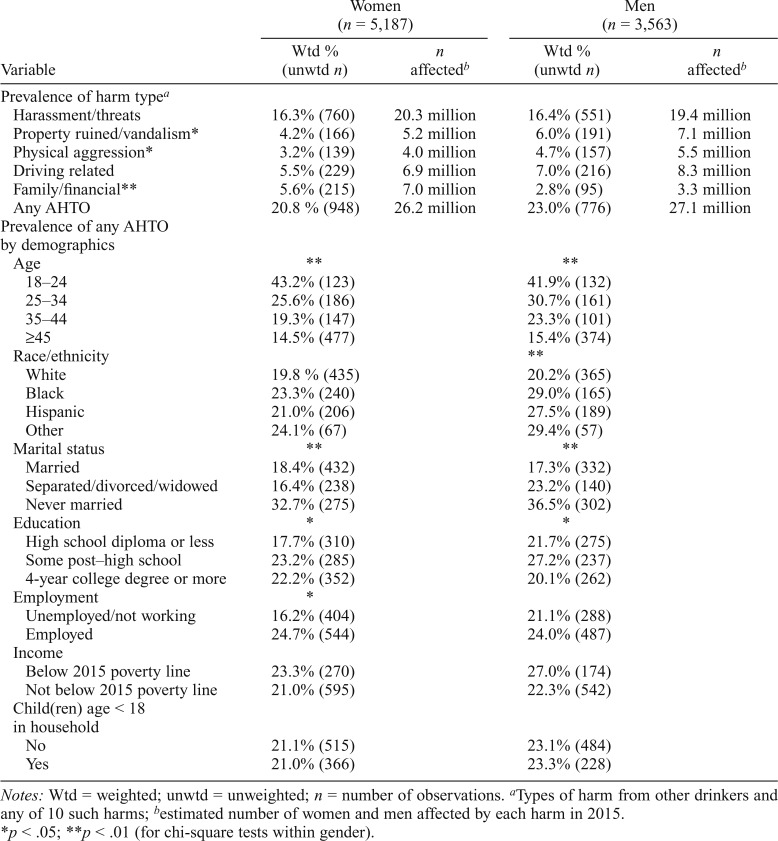

Table 1 shows the prevalence of past-year AHTO among different sociodemographic groups, by gender. About one in five adult women (21%) and almost one in four adult men (23%) experienced at least one AHTO in the past year. Thus, each year 53 million adults (26 million women, 27 million men) in the United States are estimated to experience at least one type of harm from someone else’s drinking; with 4 million to 20 million women and 3 million to 19 million men estimated to experience each specific AHTO type (Table 1).

Table 1.

Past-year prevalence of types of alcohol’s harm to others (AHTO) and of any AHTO within demographic subgroups (2015 U.S. National Alcohol Survey and 2015 National Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey data combined)

| Women (n = 5,187) |

Men (n = 3,563) |

|||

| Variable | Wtd % (unwtd n) | n affectedb | Wtd % (unwtd n) | n affectedb |

| Prevalence of harm typea | ||||

| Harassment/threats | 16.3% (760) | 20.3 million | 16.4% (551) | 19.4 million |

| Property ruined/vandalism* | 4.2% (166) | 5.2 million | 6.0% (191) | 7.1 million |

| Physical aggression* | 3.2% (139) | 4.0 million | 4.7% (157) | 5.5 million |

| Driving related | 5.5% (229) | 6.9 million | 7.0% (216) | 8.3 million |

| Family/financial** | 5.6% (215) | 7.0 million | 2.8% (95) | 3.3 million |

| Any AHTO | 20.8 % (948) | 26.2 million | 23.0% (776) | 27.1 million |

| Prevalence of any AHTO by demographics | ||||

| Age | ** | ** | ||

| 18–24 | 43.2% (123) | 41.9% (132) | ||

| 25–34 | 25.6% (186) | 30.7% (161) | ||

| 35–44 | 19.3% (147) | 23.3% (101) | ||

| ≥45 | 14.5% (477) | 15.4% (374) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ** | |||

| White | 19.8 % (435) | 20.2% (365) | ||

| Black | 23.3% (240) | 29.0% (165) | ||

| Hispanic | 21.0% (206) | 27.5% (189) | ||

| Other | 24.1% (67) | 29.4% (57) | ||

| Marital status | ** | ** | ||

| Married | 18.4% (432) | 17.3% (332) | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 16.4% (238) | 23.2% (140) | ||

| Never married | 32.7% (275) | 36.5% (302) | ||

| Education | * | * | ||

| High school diploma or less | 17.7% (310) | 21.7% (275) | ||

| Some post–high school | 23.2% (285) | 27.2% (237) | ||

| 4-year college degree or more | 22.2% (352) | 20.1% (262) | ||

| Employment | * | |||

| Unemployed/not working | 16.2% (404) | 21.1% (288) | ||

| Employed | 24.7% (544) | 24.0% (487) | ||

| Income | ||||

| Below 2015 poverty line | 23.3% (270) | 27.0% (174) | ||

| Not below 2015 poverty line | 21.0% (595) | 22.3% (542) | ||

| Child(ren) age < 18 in household | ||||

| No | 21.1% (515) | 23.1% (484) | ||

| Yes | 21.0% (366) | 23.3% (228) | ||

Notes: Wtd = weighted; unwtd = unweighted; n = number of observations.

Types of harm from other drinkers and any of 10 such harms;

estimated number of women and men affected by each harm in 2015.

p < .05;

p < .01 (for chi-square tests within gender).

The most prevalent type of AHTO was harassment/threats (16% for both women and men). Even with this harm excluded, the annual prevalence of any past-year harm was substantial: 13% for women and 15% for men, or about 34 million U.S. adults. Compared with men, women were significantly more likely to report family/financial harm, whereas men were more likely than women to report property being ruined/vandalized and physical aggression by someone who had been drinking. The prevalence of harassment/threats and driving-related harms did not differ by gender.

Prevalence of alcohol’s harm to others among sociodemographic subgroups

Among both women and men, those under 25 years of age were most likely to report AHTO, with the most common being harassment/threats (31%) followed by driving-related harm (16%). Reporting did not differ by race/ethnicity among women, but for men, Black, Hispanic or of other races/ethnicities were more likely than Whites to report AHTO. Among both women and men, those never married were the most likely to report AHTO, but presence of children in the home was unrelated to prevalence of AHTO. Employed women were more likely to report AHTO than women who were unemployed, but prevalence of AHTO did not differ by income for either women or men.

Additional gender differences were found in AHTO characteristics (not shown in Table 1). Women were more likely than men to report harm because of the drinking of a spouse/partner/ex-partner (4.2% vs. 1.8%, χ2[1] = 43.9, p < .001) or a family member (5.6% vs. 3.7%, χ2[1] = 19.8, p < .01). Men were more likely than women to report harm because of a stranger’s drinking (8.7% vs. 6.2%, χ2[1] = 22.4, p < .01). There were no gender differences in the reporting of more than one perpetrator type (3.2% of women, 3.4% of men), experiencing recurrent AHTO (9.9% of women, 11.7% of men), or experiencing more than one type of AHTO (10.2% of women, 10.0% of men) in the past year.

Risk factors for alcohol’s harm to others: Alcohol-related characteristics

Respondent’s own drinking status.

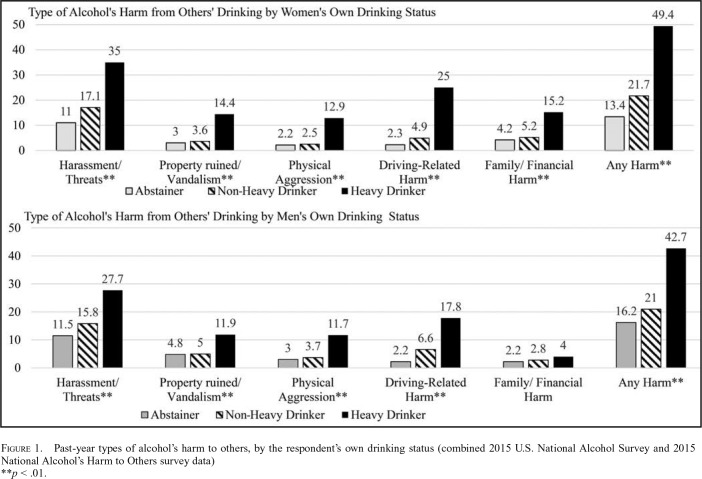

Figure 1 shows significantly higher prevalence of each type of AHTO for both women and men reporting heavy drinking in the past year, with the single exception being family/financial harms for men. Close to half (49%) of heavy drinking women and 43% of heavy drinking men reported at least one past-year AHTO. Rates of two types of AHTO were also higher among non–heavy drinkers compared with abstainers: harassment/threats (women: 17% vs. 11%, χ2[1] = 58.76, p < . 001; men: 16% vs. 12%, χ2[1] = 28.70, p < .05) and driving-related harm (women: 5% vs. 2%, χ2[1] = 35.51, p < . 01; men: 7% vs. 2%, χ2[1] = 74.36, p < .001). Past-year prevalence of other harms did not differ for non–heavy drinkers compared with past-year abstainers.

Figure 1.

Past-year types of alcohol’s harm to others, by the respondent’s own drinking status (combined 2015 U.S. National Alcohol Survey and 2015 National Alcohol’s Harm to Others survey data) **p < .01.

Logistic regression analyses with the full sample substantiated that the respondent’s own heavy drinking increased risk for each of the five AHTO subtypes, even after adjusting for other sociodemographic and family risk factors. We do not detail findings from Model 1 (Supplementary Table S1) with the full sample in which no significant interactions for gender with the respondent’s own drinking status were found for any AHTO type. Instead, we report findings from Model 2, which used the NAHTOS data to include having an HDHH (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of past-year alcohol’s harm to others with demographics, respondent’s own drinking status, and having a heavy drinker in the household in 2015 U.S. National Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey Data

| Harassment/threats |

Ruin/vandalism |

Physical aggression |

Driving related |

Family/financial |

||||||

| Risk factor | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] |

| Agea | ||||||||||

| 18–24 | 2.75** | [1.50, 5.04] | 4.66** | [1.77, 12.26] | 1.95 | [0.78, 4.87] | 4.31** | [1.75, 10.60] | 2.83* | [1.00, 8.00] |

| 25–34 | 1.94** | [1.22, 3.09] | 3.52** | [1.56, 7.95] | 2.5 | [1.00, 6.29] | 1.34 | [0.65, 2.78] | 1.28 | [0.62, 2.66] |

| 35–44 | 1.78* | [1.11, 2.84] | 1.07 | [0.38, 2.99] | 1.94 | [0.70, 5.33] | 1.28 | [0.59, 2.76] | 0.86 | [0.31, 2.39] |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||||||

| Black | 1.52 | [0.97, 2.39] | 1.69 | [0.81, 3.54] | 2.53* | [1.05, 6.11] | 0.73 | [0.33, 1.60] | 1.54 | [0.64, 3.71] |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | [0.58, 1.68] | 1.28 | [0.46, 3.53] | 1.4 | [0.47, 4.15] | 0.98 | [0.49, 1.94] | 1.15 | [0.42, 3.14] |

| Other | 1.35 | [0.80, 2.27] | 1.75 | [0.86, 3.56] | 3.22** | [152, 6.84] | 0.68 | [0.28, 1.61] | 1.69 | [0.69, 4.11] |

| Marital statusc | ||||||||||

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 1.29 | [0.86, 1.93] | 1.74 | [0.79, 3.82] | 2.81* | [1.26- 6.25] | 1.7 | [0.92, 3.14] | 0.57 | [0.29, 1.14] |

| Never married | 1.18 | [0.71, 1.96] | 0.62 | [0.30, 1.29] | 1.2 | [0.53, 2.69] | 1.8 | [0.84, 3.86] | 0.46 | [0.20, 1.08] |

| Educationd | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 1.1 | [0.73, 1.66] | 1.04 | [0.53, 2.05] | 1.87 | [0.90, 3.90] | 1.03 | [0.58, 1.83] | 0.96 | [0.49, 1.90] |

| Some college | 1.63* | [1.10, 2.42] | 1.33 | [0.67, 2.63] | 2.82** | [1.32, 6.02] | 0.85 | [0.47, 1.55] | 1.26 | [0.64, 2.49] |

| Not employed or othere | 0.92 | [0.65, 1.30] | 1.1 | [0.59, 2.04] | 0.95 | [0.50, 1.80] | 0.68 | [0.41, 1.13] | 1.35 | [0.74, 2.48] |

| Below 2015 poverty levelf | 0.9 | [0.63, 1.29] | 0.89 | [0.49, 1.62] | 0.67 | [0.35, 1.26] | 0.89 | [0.53, 1.49] | 0.72 | [0.39, 1.34] |

| Family history of alcohol problemsg | 1.71** | [1.24, 2.35] | 1.74 | [0.96, 3.13] | 1.19 | [0.63, 2.23] | 3.32** | [1.93, 5.70] | 5.27** | [2.64, 10.53] |

| Genderh | 1.01 | [0.72, 1.41] | 1.06 | [0.58, 1.95] | – | – | 0.74 | [0.44, 1.25] | 0.30** | [0.15, 0.60] |

| Respondent’s own drinkingi | ||||||||||

| Not heavy | 1.91** | [1.33, 2.74] | 0.87 | [0.44, 1.72] | – | – | 3.04** | [1.45, 6.36] | 0.9 | [0.47, 1.73] |

| Heavy (4+/5+ monthly) | 3.58** | [2.08, 6.17] | 3.77** | [1.78, 8.02] | – | – | 12.13** | [5.30- 27.76] | 2.56* | [1.02, 6.45] |

| Heavy drinker in householdj | 6.11** | [3.75, 9.93] | 5.68** | [2.90, 11.14] | 2.26** | [637, 23.59] | 3.99** | [2.02, 7.86] | 15.69** | [8.44 -29.17] |

| Gender × Respondent’s Own Drinkingk | ||||||||||

| Abstainer male | 1.02 | [030, 3.40] | ||||||||

| Non–heavy drinker female | 0.61 | [024, 1.57] | ||||||||

| Non–heavy drinker male | 2.12 | [087, 5.15] | ||||||||

| Heavy drinker female | 6.95** | [211, 22.95] | ||||||||

| Heavy drinker male | 3.77** | [145, 9.81] | ||||||||

| Observations, n | 2,726 | 2,729 | 2,727 | 2,730 | 2,730 | |||||

Notes: Reference groups:

age = 45 and older;

race/ethnicity = White;

marital status = married;

education = 4-year college degree or more;

employment = employed;

income = not below poverty;

family history of alcohol problems = none;

gender = women;

respondent’s own drinking = did not drink in the past year;

heavy drinker in household = none;

Gender × Respondent’s Own Drinking interaction = abstainer female. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Compared with abstention, heavy drinking was a significant risk factor for each AHTO type, with heavy drinkers being at 12 times greater odds for reporting driving-related harm than abstainers. Relative to abstainers, non–heavy drinkers were at 2 and 3 times greater odds for reporting harassment/threats and driving-related AHTO, respectively.

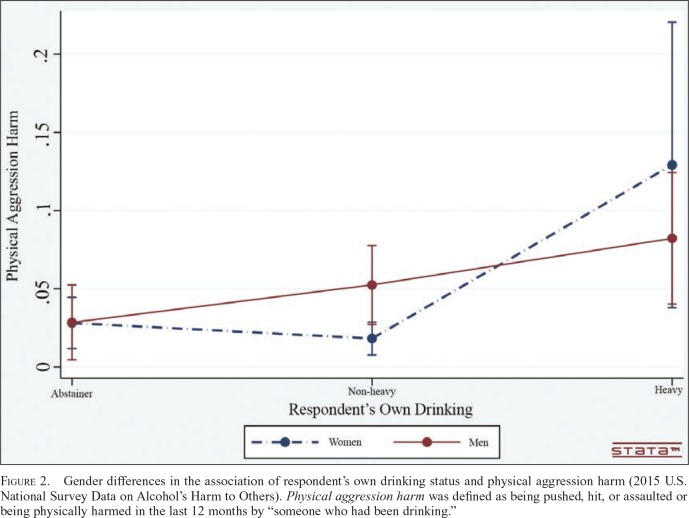

A significant interaction of gender with the respondent’s own drinking status (p < .01) emerged for physical aggression from someone else’s drinking. Heavy drinking women were at 7 times higher risk for physical aggression harm compared with abstaining women. Figure 2 shows predicted probabilities of physical aggression associated with women’s and men’s heavy drinking, highlighting a significantly greater increase in the probability of physical aggression by someone who had been drinking for heavy drinking women compared with heavy drinking men. Notably, the odds for this type of harm did not differ for non–heavy drinking women versus abstaining women. A post hoc analysis excluding heavy drinkers confirmed no interaction (p > .10) of gender with non–heavy drinking compared with abstention.

Figure 2.

Gender differences in the association of respondent’s own drinking status and physical aggression harm (2015 U.S. National Survey Data on Alcohol’s Harm to Others). Physical aggression harm was defined as being pushed, hit, or assaulted or being physically harmed in the last 12 months by “someone who had been drinking.”

Having a heavy drinker in the household.

This factor was a robust risk factor for all AHTO types (Table 2). The increased odds for AHTO associated with HDHH ranged from 4 for driving-related harm to nearly 16 for family/financial harm because of someone else’s drinking. Risk for AHTO types associated with HDHH did not differ by gender.

Because the significant interaction of gender with the respondent’s own drinking status for risk for physical aggression was found after we controlled for having an HDHH, we used post hoc analyses to explore gender differences in the harm perpetrator among the 91 NAHTOS respondents who reported physical aggression harm and answered questions on having an HDHH. Among those who reported physical aggression harm and having an HDHH (n = 32), women were more likely than men (92.2% vs. 28.4%, p < .01) to report being harmed by a drinking spouse/partner or family member. Men were more likely than women (71.6% vs. 7.8%, p < .01) to report physical aggression harm by a friend/coworker or stranger. Among those reporting physical aggression harm but no HDHH (n = 58), women were more likely than men to report physical aggression by a drinking spouse/partner/family member (66.9% vs. 18.2%, p < .01); men were more likely than women to report physical aggression harms by a friend/coworker or stranger (81.8% vs. 33.1%, p < .01). All (100%, n = 10) heavy drinking women versus 29% of heavy drinking men (n = 1 of 7) who reported physical aggression and presence of an HDHH reported that the drinker who had most negatively affected them in the past year was male.

Family history of alcohol problems.

This factor was a significant risk factor for harassment/threats, driving-related harms, and family/financial harms because of someone else’s drinking. Family history was not associated with property vandalism or physical aggression by someone who had been drinking. The risk for harm associated with family history of alcohol problems did not differ by gender.

Significant sociodemographic risk factors in Model 2 included younger age compared with age 45 and older, specifically age under 25 for all types of AHTO except physical aggression, under 45 for harassment/threats, and under 35 for property ruined/vandalism. Being Black or of other race/ethnicity; separated, widowed, or divorced; and having some college education (but no degree) were significantly associated with increased risk of physical aggression harm. Finally, male gender was associated with reduced risk (a third of that for women) for family/financial harms because of someone else’s drinking.

Findings from Model 1 (full sample without data on HDHH, Supplementary Table S1) and Model 2 (NAHTOS data only, Table 2) were consistent for age, family history of alcohol problems, and the respondent’s own drinking as significant risk factors for all AHTO types. Findings from the two models also converged for education and race/ethnicity, in that having less than a college degree, and being of Black and other race/ethnicity increased risk for physical aggression harm. Model 1 and Model 2 findings differed slightly with regard to education and marital status as AHTO risk factors. Unlike Model 2, in Model 1 having high school or less education (vs. a college degree) increased risk for physical aggression harm. Being separated, widowed, or divorced or being never married versus married increased risk for harassment/threats only in Model 1, but in Model 2 being separated, widowed, or divorced (but not never married) increased risk for physical aggression harm only.

Discussion

Research on secondhand smoke helped establish controls to reduce the public health costs of tobacco (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Similarly, data on the full range of AHTO provide the needed evidence base for efforts to reduce the public health toll of alcohol, influence public opinion, and spur legislation to reduce the health burden of alcohol (Greenfield et al., 2004). Our findings provide data on a broad range of AHTO types and risk factors and indicate the substantial prevalence of harms because of others’ drinking in the United States. In 2015, nearly one fifth of all adults in the United States, an estimated 53 million women and men, experienced at least one harm attributable to someone else’s drinking.

The burden of others’ drinking is not experienced uniformly across sociodemographic groups. Young people are more likely to experience a broad range of secondhand effects of alcohol. Physical aggression harm from others’ drinking cuts across age groups but is especially relevant for individuals of Black or other (non-Hispanic) minority ethnicity; individuals who are separated, widowed, or divorced; or those who have a college education but no degree. Unlike prior work using earlier U.S. national data that documented poverty as increasing risk for harms (Greenfield et al., 2009; Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014), we did not find poverty to be an AHTO risk factor. This may be because of our study simultaneously examining sociodemographics and alcohol-related characteristics in AHTO risk, something not done previously.

Our findings are consistent with the growing evidence of gender differences in AHTO in the United States (Greenfield et al., 2009; Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014; Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017). They also substantiate research documenting the considerable risk for women from heavy, often male, drinkers in the household and, for men, from drinkers outside their family. Further, our findings are consistent with recent data from outside the United States (Stanesby et al., 2018) that highlight the significance of the proximity of male harmful drinkers for women’s victimization by others who have been drinking. Our study contributes to the AHTO literature by elucidating heightened risk for physical aggression harm to heavy drinking women. Targeted public health programs and policies need to go beyond considering gender as an individual-level risk factor and account for gender-related vulnerabilities, due to the harmed individual’s own drinking and their social environment, particularly their relationship with the harmful drinker.

Our study documented several alcohol-related characteristics as AHTO risk factors. Any drinking increases risk for harassment/threats and for driving-related harm, and heavy drinking increases the risk for each harm type. Having a heavy drinker in one’s household and a family history of alcohol problems each elevate risk of several types of harm. Each of these alcohol-related characteristics should be considered in AHTO prevention and intervention approaches. Our prior research has highlighted the need to screen for heavy drinkers in the household to reduce alcohol’s harm to children (Kaplan et al., 2017b). These findings underscore the key role of exposure to others’ drinking in AHTO, via the harmed individual’s living or social environment, given that drinkers, including heavy drinkers, are more likely to socialize with and, thus, be exposed to other drinkers, as posited by routine activities theory (Freisthler et al., 2004).

Taken together, the present findings converge to substantiate the complex role of gender in a broad range of AHTO types and highlight the need to consider the harmed individual’s gender, and their own drinking, as well as who they drink with and where (Crane et al., 2016; Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014). Drinking context may be especially important for physical aggression harm for women, as when heavy drinking occurs in the home with an HDHH. Repeated, shared drinking at home can exacerbate existing risks for interpersonal violence (Graham & Wells, 2001), especially for a heavy drinking woman with a male heavy drinker in her household. Indeed, women are more likely than men to report experiencing physical aggression harm attributable to other’s drinking in the home and to experience this harm recurrently (Fillmore, 1985).

Our findings are limited by common reporting biases that affect self-reported data. Perceptions of what constitutes heavy drinking and what harm might be attributable to another person’s drinking are inherently subjective and transactional (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2018b). These perception biases can result in under- or over-estimates of alcohol’s harms, the presence of an HDHH, or both. Estimates of the extent of AHTO can also be limited by the type of harm assessed. Although being a passenger in a vehicle with a drinking driver substantially increases risk for alcohol-related accidents, because such accidents are not frequently reported (less than 1% prevalence), including riding with a drinking driver as a driving-related harm may inflate AHTO estimates. Conversely, our data did not include other potential harms, such as caring for someone who is injured or ill because of their own or someone else’s drinking. Further, our data are cross-sectional and cannot establish causality regarding AHTO risk factors. Although we examined differential associations of alcohol use characteristics and AHTO risk by gender, we did not assess interactions among other sociodemographic factors in AHTO risk. Frequency of exposure to others’ drinking was not assessed in our study and should be examined in future research.

Research on the association of income inequalities with ethnicity and alcohol use problems (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2013) suggests the need to investigate possible interactions of ethnicity with poverty in AHTO risk. Future studies should include such interactions to illuminate conditions contributing to greater risk for physical aggression harm for those of Black or other minority race/ethnicity. Our study did not include event-specific information for acute harms like physical aggression, such as the level of drinking by the harmed individual and by the perpetrator when the reported harm occurred.

Further, we were unable to document possible, compounded, gender-specific risks for AHTO types, such as physical assault harm for heavy drinking women with a male HDHH, due to lack of power. Although 54 women reported both heavy drinking and an HDHH, only 7 women also reported physical assault harm. Interactions of gender with the harmed individual’s drinking and having an HDHH on AHTO risk should be examined in future studies that could oversample heavy drinking women or use data from very large samples. Data on the contexts of harm, particularly drinking venues or neighborhood characteristics (e.g., alcohol outlet density), are important for understanding the socioecological context within which harms occur (Karriker-Jaffe & Greenfield, 2014).

Venue-based harm-reduction efforts, such as mandated responsible beverage service programs, may help prevent and reduce harm to others, and future studies are needed to assess impacts on harms incurred in these venues, as well as in the home. Future research should also assess the impact of policies shown to be effective in reducing population alcohol use, such as taxation, reduced availability, and restricting advertising, on exposure to others’ drinking and AHTO.

In sum, the present study provides novel population-level data on AHTO and risk factors that highlight the considerable public health impact of other people’s drinking and the urgent need to reduce the burden of alcohol in the United States. These data are vital for informing and supporting the introduction of evidence-based alcohol control measures. To reduce the burden of alcohol use, prevention efforts should include population-wide measures to reduce heavy drinking overall (Xuan et al., 2015) and targeted prevention with individuals who have an HDHH (Stanesby et al., 2018), especially women (Devries et al., 2014).

Footnotes

This research was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01AA022791 (to Thomas K. Greenfield and Katherine J. Karriker-Jaffe, principal investigators), R01 AA023870 (to Thomas K. Greenfield, Kim Bloomfield, and Sharon C. Wilsnack, principal investigators), and P50 AA005595 (Years 31–35, Thomas K. Greenfield; Years 36–40, William C. Kerr, principal investigator). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. National Institutes of Health or sponsoring institutions, which had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the article, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Crane C. A., Godleski S. A., Przybyla S. M., Schlauch R. C., Testa M. The proximal effects of acute alcohol consumption on male-to-female aggression: A meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2016;17:520–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584374. doi:10.1177/1524838015584374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Smith S. M., Pickering R. P., Grant B. F. An empirical approach to evaluating the validity of alternative lowrisk drinking guidelines. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00335.x. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K. M., Child J. C., Bacchus L. J., Mak J., Falder G., Graham K., Heise L. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109:379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393. doi:10.1111/add.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore K. M. The social victims of drinking. British Journal of Addiction. 1985;80:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb02544.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar M. H., Afshin A., Alexander L. T., Anderson H. R., Bhutta Z. A., Biryukov S., Murray C. J. L. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388:1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B., Gruenewald P. J., Ring L., LaScala E. A. An ecological assessment of the population and environmental correlates of childhood accident, assault, and child abuse injuries. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1969–1975. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00785.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B., Midanik L. T., Gruenewald P. J. Alcohol outlets and child physical abuse and neglect: Applying routine activities theory to the study of child maltreatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:586–592. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.586. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K., Wells S. The two worlds of aggression for men and women. Sex Roles. 2001;45:595–622. doi:10.1023/A:1014811624944. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: Experience with graduated frequencies. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00039-0. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Johnson S. P., Giesbrecht N. The alcohol policy development process: Policymakers speak. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2004;31:627–654. doi:10.1177/009145090403100403. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Kaplan L. M., Kerr W. C., Wilsnack S. C. Trends in Alcohol’s Harms to Others (AHTO) and co-occurrence of family-related AHTO: The four US National Alcohol Surveys, 2000–2015. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2015;9(Supplement 2):23–31. doi: 10.4137/SART.S23505. doi:10.4137/SART.S23505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Kerr W. C., Ye Y., Kaplan L. M. Those harmed by others’ drinking in the US population are more depressed and distressed. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2016;35:22–29. doi: 10.1111/dar.12324. doi:10.1111/dar.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Ye Y., Kerr W., Bond J., Rehm J., Giesbrecht N. Externalities from alcohol consumption in the 2005 US National Alcohol Survey: Implications for policy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6:3205–3224. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6123205. doi:10.3390/ijerph6123205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L. M., Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Greenfield T. K. Drinking context and alcohol’s harm from others among men and women in the 2010 US National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Substance Use. 2017a;22:412–418. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2016.1232758. doi:10.1080/14659891.2016.1232758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L. M., Nayak M. B., Greenfield T. K., Karriker-Jaffe K. J. Alcohol’s harm to children: Findings from the 2015 United States National Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey. Journal of Pediatrics. 2017b;184:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.025. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Greenfield T. K. Gender differences in associations of neighbourhood disadvantage with alcohol’s harms to others: A cross-sectional study from the USA. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33:296–303. doi: 10.1111/dar.12119. doi:10.1111/dar.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Greenfield T. K., Kaplan L. M. Distress and alcohol-related harms from intimates, friends, and strangers. Journal of Substance Use. 2017;22:434–441. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2016.1232761. doi:10.1080/14659891.2016.1232761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Li L., Greenfield T. K. Estimating mental health impacts of alcohol’s harms from other drinkers: Using propensity scoring methods with national cross-sectional data from the United States. Addiction. 2018a;113:1826–1839. doi: 10.1111/add.14283. doi:10.1111/add.14283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Roberts S. C. M., Bond J. Income inequality, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:649–656. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300882. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Room R., Giesbrecht N., Greenfield T. K. Alcohol’s harm to others: Opportunities and challenges in a public health framework. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2018b;79:239–243. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.239. doi:10.15288/jsad.2018.79.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A.-M., Catalano P., Chikritzhs T., Dale C., Doran C., Ferris J., et al. The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others. Fitzroy, Victoria: AER Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre, Eastern Health.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A.-M., Rankin G., Waleewong O., Callinan S., Hoang H. T., Florenzano R., Room R. A multi-country study of harms to children because of others’ drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:195–202. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.195. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A.-M., Room R., Ferris J., Wilkinson C., Livingston M., Mugavin J. Surveying the range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others in Australia. Addiction. 2011;106:1603–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03445.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M., Wilkinson C., Laslett A.-M. Impact of heavy drinkers on others’ health and well-being. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:778–785. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.778. doi:10.15288/jsad.2010.71.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/. [Google Scholar]

- Stanesby O., Callinan S., Graham K., Wilson I. M., Greenfield T. K., Wilsnack S. C., Laslett A.-M. Harm from known others’ drinking by relationship proximity to the harmful drinker and gender: A meta-analysis across 10 countries. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2018;42:1693–1703. doi: 10.1111/acer.13828. doi:10.1111/acer.13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. 2006 Retrieved from https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/secondhandsmoke/fullreport.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L. A., White H. R., Johnson V. Alcohol initiation experiences and family history of alcoholism as predictors of problemdrinking trajectories. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:56–65. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.56. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan Z., Blanchette J., Nelson T. F., Heeren T., Oussayef N., Naimi T. S. The alcohol policy environment and policy subgroups as predictors of binge drinking measures among US adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:816–822. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302112. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]