Summary

Background

Adjuvant trastuzumab significantly improves outcomes for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer. The standard treatment duration is 12 months but shorter treatment could provide similar efficacy while reducing toxicities and cost. We aimed to investigate whether 6-month adjuvant trastuzumab treatment is non-inferior to the standard 12-month treatment regarding disease-free survival.

Methods

This study is an open-label, randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Patients were recruited from 152 centres in the UK. We randomly assigned patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, aged 18 years or older, and with a clear indication for chemotherapy, by a computerised minimisation process (1:1), to receive either 6-month or 12-month trastuzumab delivered every 3 weeks intravenously (loading dose of 8 mg/kg followed by maintenance doses of 6 mg/kg) or subcutaneously (600 mg), given in combination with chemotherapy (concurrently or sequentially). The primary endpoint was disease-free survival, analysed by intention to treat, with a non-inferiority margin of 3% for 4-year disease-free survival. Safety was analysed in all patients who received trastuzumab. This trial is registered with EudraCT (number 2006–007018–39), ISRCTN (number 52968807), and ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT00712140).

Findings

Between Oct 4, 2007, and July 31, 2015, 2045 patients were assigned to 12-month trastuzumab treatment and 2044 to 6-month treatment (one patient was excluded because they were double randomised). Median follow-up was 5·4 years (IQR 3·6–6·7) for both treatment groups, during which a disease-free survival event occurred in 265 (13%) of 2043 patients in the 6-month group and 247 (12%) of 2045 patients in the 12-month group. 4-year disease-free survival was 89·4% (95% CI 87·9–90·7) in the 6-month group and 89·8% (88·3–91·1) in the 12-month group (hazard ratio 1·07 [90% CI 0·93–1·24], non-inferiority p=0·011), showing non-inferiority of the 6-month treatment. 6-month trastuzumab treatment resulted in fewer patients reporting severe adverse events (373 [19%] of 1939 patients vs 459 [24%] of 1894 patients, p=0·0002) or stopping early because of cardiotoxicity (61 [3%] of 1939 patients vs 146 [8%] of 1894 patients, p<0·0001).

Interpretation

We have shown that 6-month trastuzumab treatment is non-inferior to 12-month treatment in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, with less cardiotoxicity and fewer severe adverse events. These results support consideration of reduced duration trastuzumab for women at similar risk of recurrence as to those included in the trial.

Funding

UK National Institute for Health Research, Health Technology Assessment Programme.

Introduction

Trastuzumab delivered with chemotherapy for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer in the metastatic1 and adjuvant settings2, 3, 4 resulted in improved treatment outcomes, and long-term follow-up has confirmed these benefits.5, 6 A 12-month treatment duration with adjuvant trastuzumab was chosen arbitrarily for the pivotal licensing trials2, 3, 4 and, subsequently, became standard. However, results from the FinHer trial,7 which randomly assigned patients to adjuvant chemotherapy with or without 9 weeks of concurrent trastuzumab, showed a statistically significant improvement in disease-free survival for patients assigned to trastuzumab (hazard ratio [HR] 0·29 [95% CI 0·13–0·64; p=0·002) and generated considerable interest in the possibility of shorter trastuzumab durations than the standard treatment time. Trastuzumab has well recognised toxic effects, particularly cardiac,8, 9, 10, 11 and substantial costs. Studies have been done to assess whether similar outcomes can be achieved with reduced treatment duration. PHARE (France),12 PERSEPHONE (UK),13 and the HORG study (Greece)14 compared 6-month with 12-month trastuzumab treatments. Short-HER (Italy)15 and SOLD (international)16 compared treatment for 12 months with treatment for 9 weeks (concurrently with docetaxel-first sequenced chemotherapy), and E219817 compared treatment for 12 months with 12-week treatments (concurrently with weekly paclitaxel). Five of these six de-escalation trials were supported wholly or in part by government funding and aimed to discover the optimal balance between efficacy, toxicity, and cost for patients and health services. The PERSEPHONE trial, reported in this Article, aimed to investigate the hypothesis that 6-month adjuvant trastuzumab treatment is non-inferior to the standard 12-month treatment in terms of outcomes, but with reduced toxicity. The trial uses a non-inferiority design18 and we report 4-year disease-free survival results, the definitive primary endpoint.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed in October, 2006, using search terms “trastuzumab”, “adjuvant”, and “HER2 positive breast cancer”, for papers published in English. We found three randomised controlled trials of adjuvant trastuzumab added to chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer. In 2005, two reports established 12-month trastuzumab as the standard of care. The HERA trial examined both 24-month and 12-month trastuzumab compared with a no trastuzumab control group and reported a benefit of disease-free survival at 2 years of 8·4% (95% CI 2·1–14·8) for the 12-month treatment group compared with the no trastuzumab group. The joint analysis of the US studies (NSABP-B31 and NCCTG-N9831) showed a similar hazard ratio (HR) for 12-month trastuzumab and a control group that did not receive this drug, with a benefit of disease-free survival of 11·8% at 3 years. However, in 2006 a smaller study (FinHer) reported just 9-week trastuzumab with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy control, and showed very similar results with a benefit in disease-free survival of 11·7% at 3 years for 9-week trastuzumab. This result prompted a substantial interest in whether duration of trastuzumab could be reduced and a number of trials were started all with a non-inferiority design, to establish whether shorter duration trastuzumab could have similar efficacy but reduced toxicity.

Added value of this study

The Persephone trial was a pragmatic study of 6-month versus 12-month trastuzumab, which mapped onto standard practice in the UK and included all patients who were planned to receive adjuvant or neoadjuvant trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Broad eligibility criteria, and in particular the inclusion of all chemotherapy regimens, ensured that results would be directly applicable to similar patients in the clinic. The trial has a non-inferiority design and, with recruitment of over 4000 patients, was powered to test whether 6-month treatment was no worse than 3% less of the standard disease-free survival with 12-month treatment. PERSEPHONE is the largest of the reduced duration, adjuvant trastuzumab trials, it recruited the required number of patients, and accrued the number of events set out in the statistical analysis plan. This trial is the only one to show clear non-inferiority for reduced duration trastuzumab in HER2-positive early breast cancer.

Implications of all the available evidence

Available evidence for trastuzumab duration includes the SOLD and Short-HER trials, which compared 9-week trastuzumab with 12-month trastuzumab, and neither trial showed non-inferiority. The HORG trial (n=481) and the PHARE trial (n=3380) compared 6-month with 12-month trastuzumab and also did not show non-inferiority. The PHARE trial was presented in December, 2018, with a median follow-up of 90 months and showed a HR of 1·08 (95% CI 0·93–1·25), which is remarkably similar to the data we report from PERSEPHONE's findings (1·07 [0·93–1·24]). However, the PHARE trial set a 2% non-inferiority margin and HR boundary of 1·15, and, therefore, accordingly cannot claim non-inferiority. During the trial, standard treatments gradually changed in the clinic and PERSEPHONE has captured these data. PERSEPHONE is the only trial to show clear non-inferiority for 6 months of trastuzumab in the early disease setting in the population treated and we believe this result, together with the recent, mature data from PHARE, should signal reduced duration trastuzumab becoming a standard of care in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer.

Methods

Study design

PERSEPHONE was a prospective, multicentre, phase 3 randomised trial to test the hypothesis that 6 months of trastuzumab treatment is non-inferior to the standard 12-month treatment. Patients were recruited in 152 hospitals in the UK. The trial was approved by the Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) on Aug 9, 2007, (07/MRE08/35), and then by Research and Development departments at each participating institution. It was sponsored by Cambridge University Hospital National Health Service Trust and University of Cambridge; and co-ordinated and analysed by the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Warwick. The trial was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and supported by the National Cancer Research Network (number 4078), which funded research personnel in local networks to support the trial. The trial was run under the auspices of an independent data safety and monitoring committee (IDSMC), an independent trial steering committee (TSC), and a trial management group (TMG). Ethical approval is from the MREC. The protocol can be found online on the Warwick Clinical Trial Unit website.

Participants

Eligible patients, aged 18 years or older, had a histological diagnosis of invasive early breast cancer with overexpression of HER2 receptor, defined according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists guidelines.19 All patients had a clear indication for chemotherapy and provided written informed consent. At the beginning of the trial, all patients were randomised before starting trastuzumab. However, in 2009, recruitment numbers remained substantially lower than expected and after discussion between the TMG, TSC, IDSMC, and funders, a protocol amendment (protocol version 3.1; July, 2009) allowed randomisation to occur at any time up to and including the ninth cycle of trastuzumab. All participants were considered medically fit to receive treatment by the responsible clinician. Female patients who were of child-bearing potential were non-pregnant, non-lactating, and agreed to use adequate contraception during treatment. For full eligibility criteria see online protocol.

Randomisation and masking

The trial was open label and patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to either 12 months (standard 18 cycles) of trastuzumab or 6 months (experimental nine cycles) of trastuzumab (figure 1). Randomisation was done by telephone to the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, where a central computerised minimisation procedure used the following stratification variables: oestrogen receptor status (positive or negative); chemotherapy type (anthracycline without taxane, anthracycline with taxane, taxane without anthracycline, or neither anthracycline nor taxane); chemotherapy timing (adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy); and trastuzumab timing (concurrent or sequential).

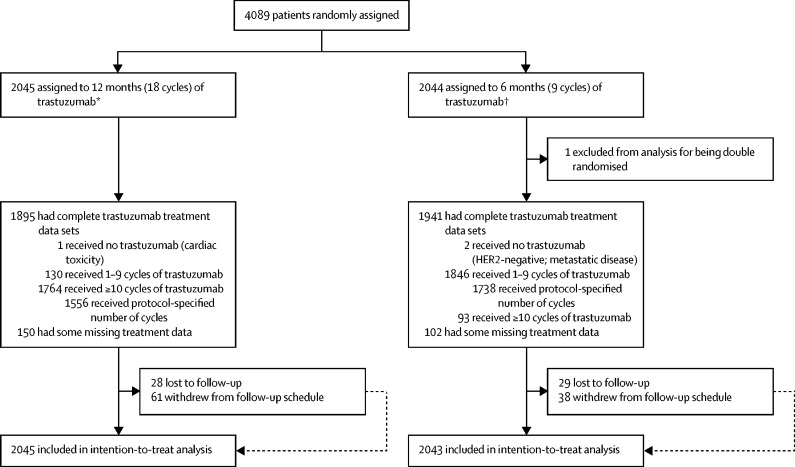

Figure 1.

Trial profile

*Seven patients were found to be ineligible after randomisation (four had previous cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ treated with surgery and radiotherapy, two were HER2 negative, and one had primary cancer confined to the axilla). †11 patients were found to be ineligible after randomisation (seven had previous cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ treated with surgery and radiotherapy, one was HER2 negative, two had metastatic disease, and one had received >9 cycles of trastuzumab).

Procedures

Trastuzumab was administered every 3 weeks either intravenously or, following a third protocol amendment (version 4.0, published Oct 31, 2013), subcutaneously. Switching from intravenous to subcutaneous route was allowed at clinician discretion. The intravenous loading dose was 8 mg/kg followed by maintenance doses of 6 mg/kg, and the subcutaneous dose was fixed at 600 mg.

After randomisation, patients were followed up routinely at the centre where the patient was recruited or an associated institution with ethical approval for the study. Follow-up was every 12 weeks for the first year after starting trastuzumab and all toxic effects were recorded. Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 3) grades were recorded for each trastuzumab cycle after randomisation. Originally, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessments every 3 months for up to 12 months after starting trastuzumab were required for all patients. However, in June, 2013, the IDSMC recommended reducing LVEF monitoring to every 4 months, in line with new national guidelines.20 Trastuzumab was discontinued if LVEF decreased to lower than 50%; LVEF was reassessed after 6 weeks and 12 weeks. Trastuzumab was restarted if the LVEF recovered; however, if treatment could not be restarted for 12 weeks because of persistently low LVEF, it was stopped permanently. Patients were followed up every 6 months for the second year and annually thereafter, in accordance with standard local practice, and continued for 10 years.

The quality of life assessment schedule, defined by our group for the purposes of the trial, specifies assessments before starting trastuzumab, and then 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months later. All patients followed this schedule from the time they entered the trial, completing assessments at the same timepoints in their treatment. Patients who were randomised during their trastuzumab treatment did not have a baseline quality of life assessment and some also did not have the 3-month assessment if randomised after this timepoint. Questions regarding general health and the Euroqol 5D questionnaire 3 level (EQ-5D-3L) were recorded. The health economic analysis will be reported separately.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was disease-free survival, which was calculated from the date of diagnostic biopsy to the date of first invasive breast cancer relapse (local or distant) or death, or to date of censor in patients alive and relapse-free. The secondary endpoint of overall survival was also calculated from the date of diagnostic biopsy. Other secondary endpoints were expected incremental cost-effectiveness (health economic analysis), cardiac function as assessed by LVEF during treatment, and analysis of predictive factors for development of cardiac damage. Since randomisation could occur at any time up to and including the ninth cycle of trastuzumab, a prespecified landmark analysis was done from 6 months after the start of trastuzumab. The number of trastuzumab cycles received per patient was recorded, with route of administration and reasons for any deviation from protocol. LVEF measurements were defined as low if results were less than 50% or reported as low without quantification of LVEF. Incidence of clinical cardiac dysfunction, defined as symptoms or signs of congestive heart failure or new cardiac medication, was recorded every 3 months for 12 months. A cardiologist (CP) was a member of the trials group and reviewed the cardiac toxicity together with the Chief Investigator (HME) and other members of the TMG.

Disease-free interval, distant disease-free interval, distant disease-free survival, invasive disease-free survival (including contralateral breast and second primary cancers, according to the STandardized definitions for Efficacy End Points system),21 and breast-cancer specific survival were also analysed post hoc.

Statistical analysis

The trial was designed to assess non-inferiority of the experimental group (6 months of trastuzumab), and the clinically acceptable non-inferiority margin for the 6-month group was defined as being not worse than an absolute value of 3% below the 4-year disease-free survival of the standard group (12 months of trastuzumab). This 3% non-inferiority margin was decided before the start of the trial following consensus from the trial development group together with the patient and public involvement group. Data from adjuvant trastuzumab trials at the time2, 3, 4 estimated the 4-year disease-free survival for patients treated with 12 months of trastuzumab to be 80%. Consequently, 4000 patients (2000 in each group) were required to show the non-inferiority of 6-month trastuzumab treatment with a 3% non-inferiority margin of the 4-year disease-free survival, and 5% one-sided significance and 85% statistical power. This calculation assumes a 4-year recruitment period, an additional 5-year follow-up period, and 4% of patients being lost to follow-up. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and the HR between the two groups was estimated using a Cox's proportional hazards model containing only the trial treatment effect, after assessment of the proportionality of hazards using log-log plots. The upper limit of the HR required to show the 3% non-inferiority was only to be calculated at the time of analysis and based on the disease-free survival in the 12-month group observed at the time of analysis. As described by Mauri and D'Agostino,22 if the upper limit of the 90% CI (the 95th percentile) of the estimated HR was less than the relevant 3% absolute non-inferiority limit, then the experimental group (6-month trastuzumab) would be regarded as non-inferior.

Warwick Clinical Trials Unit analysed all the data using SAS (version 9.4) software. The IDSMC-approved statistical analysis plan stated that the event-driven primary endpoint analysis required 500 disease-free survival events to have occurred. At this point, the relevant non-inferiority limits in terms of HR for 3% non-inferiority in disease-free survival were calculated using the observed 4-year disease-free survival events in the standard, 12-month group. The statistical analysis plan included a secondary analysis adjusting for stratification factors within the Cox model and also the presentation of treatment effect on disease-free survival for stratification variables and baseline prognostic factors using HR plots with the test for interaction or heterogeneity using Cochran's Q.23 To remove the effect of timing of randomisation, the statistical analysis plan also defined an exploratory landmark analysis for patients alive and disease-free 6 months after starting trastuzumab. All randomly assigned patients were included in all outcome analyses, and all patients who started trastuzumab were included in all safety analyses. All analyses were done on an intention-to-treat basis because the trial aimed to compare the duration of trastuzumab treatments in routine clinical practice. Treatment analyses were done for all patients with available data. PERSEPHONE is registered with EudraCT (number 2006–007018–39), International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial (number ISRCTN 52968807), and ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT00712140).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and, along with LH and JAD, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication with the agreement of all the authors and the IDSMC.

Results

Between Oct 4, 2007, and July 31, 2015, a total of 4089 patients were randomly assigned by 210 clinicians at 152 sites in the UK (figure 1). One double randomisation reduced the analysis set to 4088 patients. 18 patients were deemed ineligible after randomisation, mainly because of previous cancers or ductal carcinoma in situ treated with radiotherapy and surgery. Patient characteristics were similar between the two groups (table 1). Randomisation before starting trastuzumab occurred in 1786 [44%] of 4088 patients and the timings for those randomly assigned after the first cycle of trastuzumab are shown in the appendix (p 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trial participants

| 12-month group (n=2045) | 6-month group (n=2043) | |

|---|---|---|

| Oestrogen receptor status* | ||

| Negative | 633 (31%) | 632 (31%) |

| Positive | 1412 (69%) | 1411 (69%) |

| Chemotherapy type* | ||

| Anthracycline-based | 854 (42%) | 846 (41%) |

| Taxane-based | 200 (10%) | 203 (10%) |

| Anthracycline-based and taxane-based | 989 (48%) | 991 (49%) |

| No taxane and no anthracycline | 2 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Chemotherapy timing* | ||

| Adjuvant | 1737 (85%) | 1731 (85%) |

| Neoadjuvant | 308 (15%) | 312 (15%) |

| Trastuzumab timing* | ||

| Concurrent | 951 (47%) | 952 (47%) |

| Sequential | 1094 (53%) | 1091 (53%) |

| Age at randomisation, years | ||

| Median (range) | 56 (23–82) | 56 (23–83) |

| <35 | 50 (2%) | 45 (2%) |

| 35–49 | 552 (27%) | 557 (27%) |

| 50–59 | 608 (30%) | 656 (32%) |

| ≥60 | 835 (41%) | 785 (38%) |

| Nodal status at surgery (patients who received adjuvant therapy) | ||

| Negative | 1003/1737 (58%) | 1019/1731 (59%) |

| 1–3 nodes positive | 479/1737 (28%) | 486/1731 (28%) |

| 4+ nodes positive | 244/1737 (14%) | 211/1731 (12%) |

| Unknown | 11/1737 (<1%) | 15/1731 (<1%) |

| Tumour size (patients who received adjuvant therapy)† | ||

| ≤2 cm | 824/1737 (47%) | 807/1731 (47%) |

| >2 and ≤5 cm | 778/1737 (45%) | 786/1731 (45%) |

| >5 cm | 87/1737 (5%) | 83/1731 (5%) |

| Unknown | 48/1737 (3%) | 55/1731 (3%) |

| Tumour grade‡ | ||

| I (well differentiated) | 29 (1%) | 34 (2%) |

| II (moderately differentiated) | 628 (31%) | 642 (31%) |

| III (poorly differentiated) | 1322 (65%) | 1297 (63%) |

| Unknown | 66 (3%) | 70 (3%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1658 (81%) | 1648 (81%) |

| Asian | 57 (3%) | 52 (3%) |

| Black | 52 (3%) | 45 (2%) |

| Other | 17 (1%) | 21 (1%) |

| Unknown | 261 (13%) | 277 (14%) |

| Menopausal status before chemotherapy | ||

| Premenopausal | 567 (28%) | 580 (28%) |

| Perimenopausal | 110 (5%) | 150 (7%) |

| Postmenopausal | 1144 (56%) | 1070 (52%) |

| Not assessable or not available | 224 (11%) | 243 (12%) |

| Reported previous use of cardiac medication | ||

| Yes | 44 (2%) | 55 (3%) |

| No | 2001 (98%) | 1988 (97%) |

| HER2 immunohistochemistry score and FISH positivity | ||

| 3+ | 1460 (71%) | 1487 (73%) |

| 2+ and FISH positive | 540 (26%) | 497 (24%) |

| Not available | 45 (2%) | 59 (3%) |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise specified. Six men are included in the 4088 patients, four in the 12-month group and two in the 6-month group. FISH=fluorescence in-situ hybridisation.

Stratification variable.

Size of the largest invasive tumour at diagnosis.

Grade of the largest invasive tumour at diagnosis.

The majority of patients (69%) had oestrogen receptor-positive tumours. Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=620), the majority (553 [89%]) received anthracycline and taxane, 53 (9%) anthracycline without taxane, and 14 (2%) taxane without anthracycline; for patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy (n=3468), less than half received anthracycline and taxane (1427 [41%]) or anthracycline without taxane (1647 [47%]), and 389 (11%) received taxane without anthracycline (appendix p 1). UK standard practice gradually changed during trial recruitment with a steady increase in anthracycline and taxane combinations, trastuzumab commencing concurrently with taxanes but not anthracyclines, taxane-based treatment without anthracyclines, and neoadjuvant timing (appendix p 2). Patients given trastuzumab and chemotherapy concurrently compared with sequentially, in the adjuvant group, were more often node positive (749 [53%] of 1412 patients vs 671 [33%] of 2056, p<0·0001), had larger tumours (>2 cm; 777 [55%] of 1412 patients vs 957 [47%] of 2056 patients, p<0·0001); in the whole group, patients more often received neoadjuvant treatment (491 [26%] of 1903 patients vs 129 [6%] of 2185 patients, p<0·0001) and had shorter median duration of follow-up (4·5 years [IQR 3·3–5·9] vs 5·8 years [4·5–7·4]; appendix pp 2–4). More than half of the patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were node negative (2022 [58%] of 3468 participants) and 1631 [47%] of 3468 patients in this group had tumours smaller than 2 cm (table 1).

Complete trastuzumab administration details are available for 3836 (94%) of 4088 patients: 1895 (93%) of 12-month treatment patients and 1941 (95%) of 6-month treatment patients (figure 1). 40 530 (82%) of 49 632 trastuzumab cycles were administered intravenously and 9102 (18%) of 49 632 cycles subcutaneously. In total, 3294 (86%) of 3836 patients received the protocol-specified number of trastuzumab cycles: 1556 (82%) of 1895 patients assigned to 12-month treatment who had available treatment data and 1738 (90%) of 1941 patients assigned to 6-month treatment with available treatment data. The most common reasons for early treatment cessation were cardiac toxicity (146 [8%] of 1894 patients in the 12-month group, 61 [3%] of 1939 patients in the 6-month group) and patient request (91 [5%] of 1894 patients in the 12-month group, 24 [1%] of 1939 patients in the 6-month group; figure 1). Delays occurred in 3631 (7%) of 49 632 cycles (appendix p 4), the main reasons being holidays, sepsis or infection, and cardiotoxicity. The most common chemotherapy treatments (known for 3959 patients: 1985 patients in the 12-month group and 1974 patients in the 6-month group), were fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide, with docetaxel (811 [41%] of 1985 patients in the 12-month group vs 790 [40%] of 1974 in the 6-month group), and without docetaxel (548 [28%] of 1985 vs 567 [29%] of 1974).

At database lock on April 17, 2018, with a median follow-up of 5·4 years (IQR 3·6–6·7) for both treatment groups and 3588 (96%) of 3753 alive patients followed up for at least 2 years, 335 deaths had been reported (156 [8%] of 2045 patients in the 12-month group and 179 [9%] of 2043 patients in the 6-month group), the majority (272 [81%] of 335 patients: 129 [83%] of 156 in the 12-month group and 143 [80%] of 179 in the 6-month group) due to breast cancer (table 2). Local or distant relapse occurred in 452 (11%) of 4088 patients, with distant metastases in 373 patients (183 [9%] of 2045 in the 12-month group vs 190 [9%] of 2043 patients in the 6-month group). These metastases occurred in the liver (81 [44%] of 183 patients vs 79 [42%] of 190 patients), bone (61 [33%] patients vs 81 [43%] patients), lung (72 [39%] patients vs 67 [35%] patients), and brain (38 [21%] patients vs 40 [21%] patients). A relapse or death was reported for 512 (13%) patients overall.

Table 2.

Details of events

| 12-month group (n=2045) | 6-month group (n=2043) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 156 (8%) | 179 (9%) | |

| Breast cancer listed as a cause | 129 (6%) | 143 (7%) | |

| Breast cancer not listed as a cause, but a local or distant relapse reported | 2 (<1%) | 6 (<1%) | |

| Breast cancer not listed as a cause and no local or distant relapse reported | 25 (1%) | 30 (1%) | |

| Relapse* | 218 (11%) | 234 (11%) | |

| Local relapse | 79 (4%) | 77 (4%) | |

| Distant relapse | 183 (9%) | 190 (9%) | |

| Relapse or death | 247 (12%) | 265 (13%) | |

| Second primary | 58 (3%) | 52 (3%) | |

Data are n (%).

Patients can have both a local and distant relapse recorded.

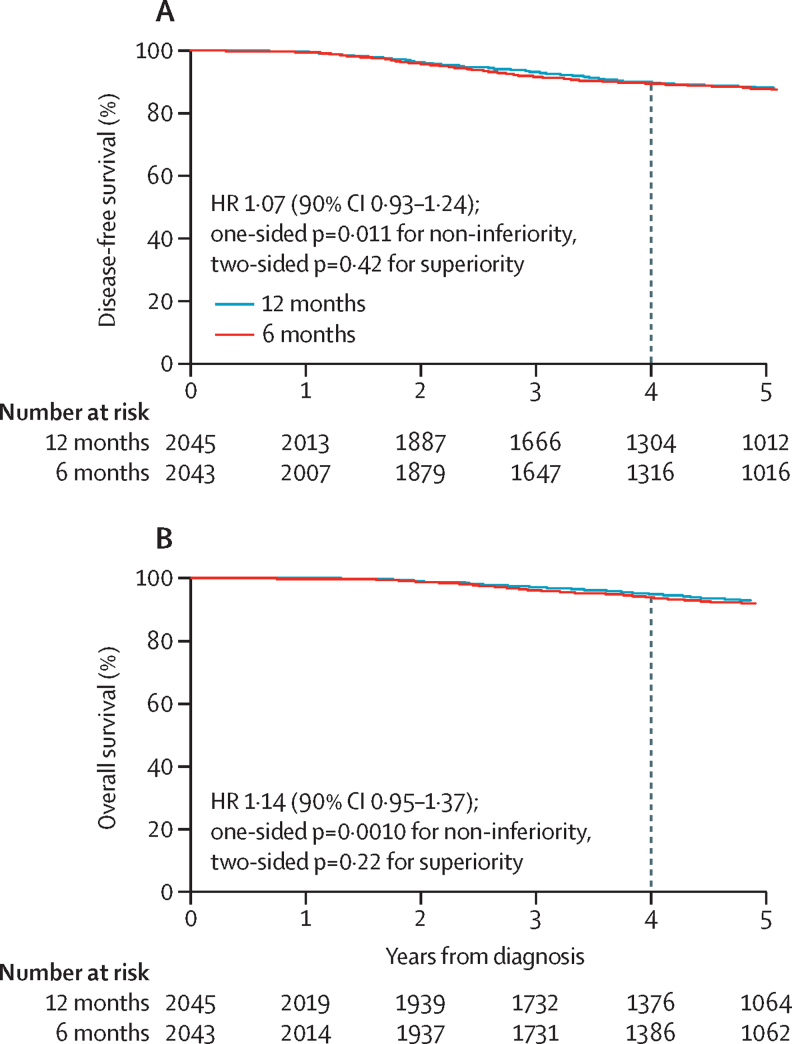

The 4-year disease-free survival in the 12-month group was 89·8% (95% CI 88·3–91·1) and 89·4% (87·9–90·7) in the 6-month group (figure 2A), showing a 0·4% absolute difference in disease-free survival between treatment groups at 4 years. Thus, with the non-inferiority margin of 3%, the non-inferiority limit for the HR was set at 1·32. The HR for relapse or death with 6 months compared with 12 months trastuzumab was 1·07 (90% CI 0·93–1·24, non-inferiority p=0·011); this outcome met the prespecified definition of non-inferiority. The two-sided p value for difference between treatments (superiority) was 0·42. Adjustment for all stratification factors gave the same results with an HR of 1·07 (90% CI 0·93–1·24; non-inferiority p=0·0097). Analysis of overall survival (figure 2B) also met the prespecified definition of non-inferiority (4-year overall survival of 94·8% [95% CI 93·7–95·8] in the 12-month group and 93·8% [92·6–94·9] in the 6-month group), showing a 1% absolute difference in overall survival between treatment groups at 4 years. The non-inferiority limit for the HR was set at 1·60. The HR for overall survival was 1·14 (90% CI 0·95–1·37, non-inferiority p=0·0010). The two-sided p value for difference between treatments was 0·22 and adjustment for all stratification factors resulted in similar results (HR 1·13 [90% CI 0·94–1·35]).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of disease-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) for 6-month and 12-month trastuzumab treatment groups

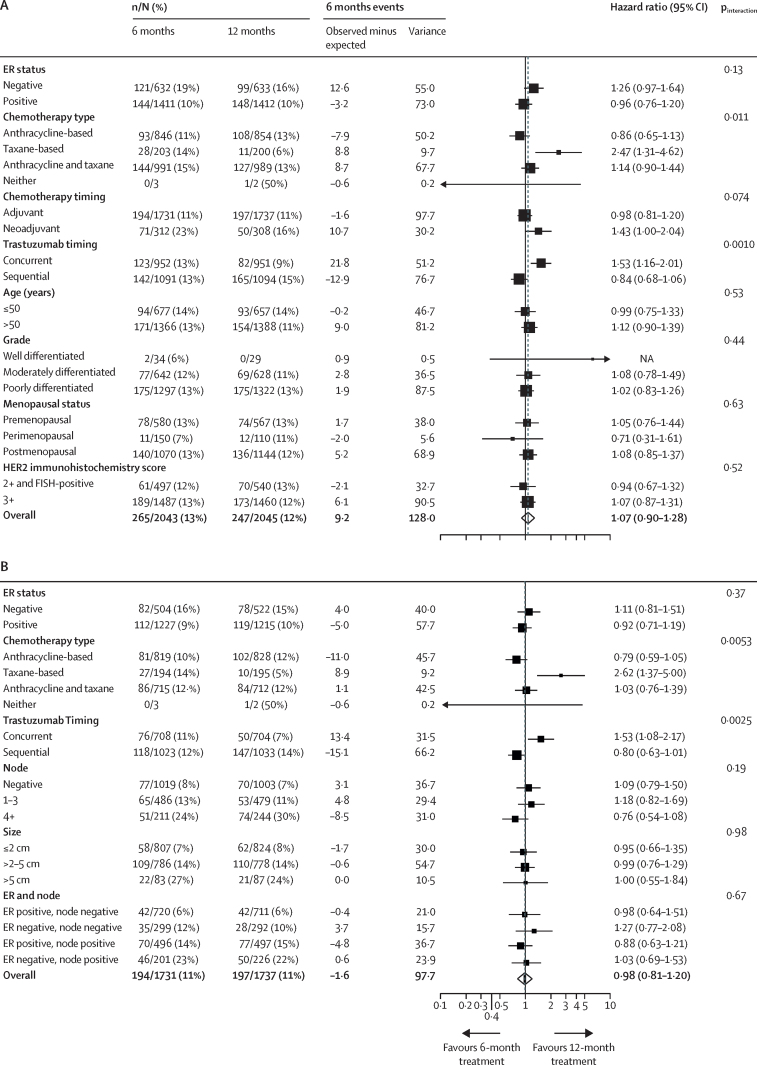

Forest plots for disease-free survival that included all patients (figure 3A) showed heterogeneity for chemotherapy type (p=0·011), predominantly driven by the small number of events in the taxane-only group, in which most patients received docetaxel with cyclophosphamide.24 The timing of trastuzumab relative to chemotherapy (concurrent or sequential) showed heterogeneity between groups (p=0·0010), favouring the 12-month treatment for patients receiving concurrent trastuzumab. Forest plots for overall survival (appendix p 7) also showed heterogeneity for concurrent and sequential treatments; they additionally showed heterogeneity for oestrogen receptor-status (p=0·019), with improved outcomes for 12-month trastuzumab treatments for patients with oestrogen receptor-negative disease. No heterogeneity was observed for age, grade, menopausal status, or HER2 score (immunohistochemistry score 3+, or score 2+ with fluorescence in-situ hybridisation-positive) for disease-free survival or overall survival. Exploratory forest plots for patients who received adjuvant therapy only (figure 3B; appendix p 8) showed similar results, with no heterogeneity for node status, size, and combined oestrogen receptor and node status.

Figure 3.

Forest plots of disease-free survival for all patients (A) and patients who received adjuvant treatment (B)

FISH=fluorescence in-situ hybridisation. ER=oestrogen receptor.

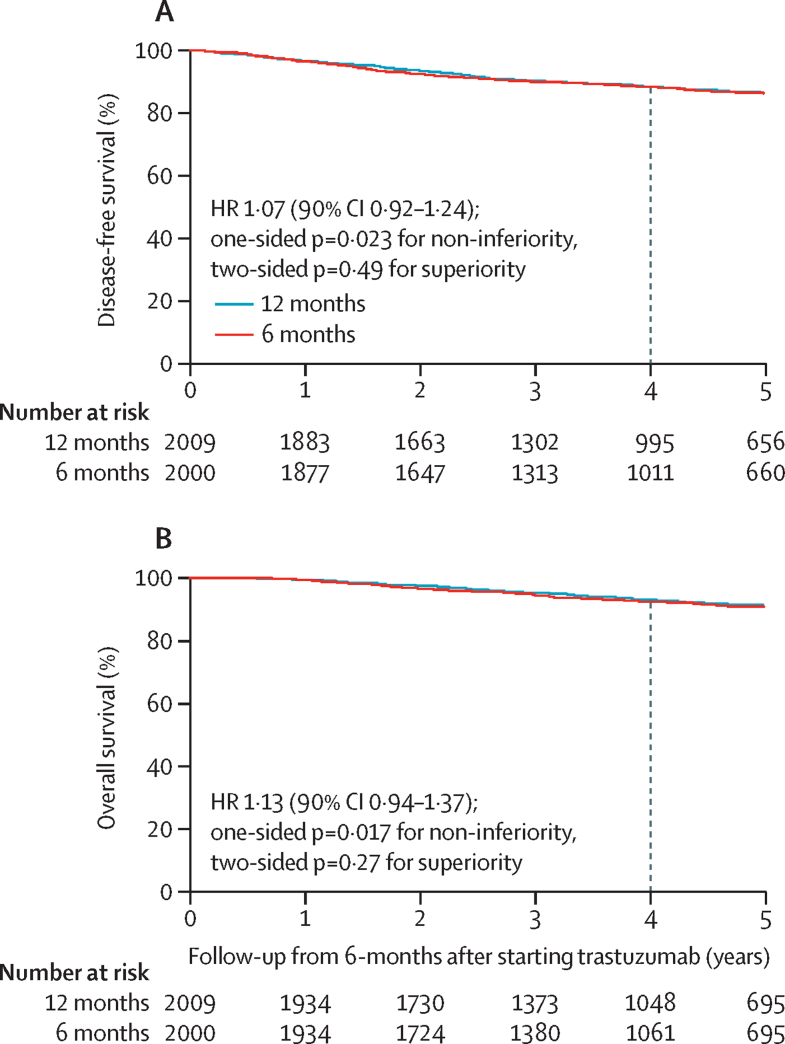

The landmark analysis of disease-free survival and overall survival included 4009 patients (2009 patients in the 12-month group and 2000 patients in the 6-month group) who remained alive and disease-free 6 months after starting trastuzumab. Kaplan-Meier (figure 4) and forest plots (appendix pp 9–12) for landmark disease-free survival and overall survival showed similar results to those observed for disease-free survival and overall survival. Landmark 4-year disease-free survival was 88·3% for the 12-month group and 88·2% for the 6-month group (absolute difference 0·1%). Therefore, the non-inferiority limit for the HR was set at 1·28 and, with a calculated HR of 1·07 (90% CI 0·92–1·24), this outcome met the prespecified definition of non-inferiority (non-inferiority p=0·023). Landmark 4-year overall survival was 92·8% for the 12-month group and 92·2% for the 6-month group (absolute difference 0·6%). Thus, the non-inferiority limit for the HR was set at 1·44 and, with a calculated HR of 1·13 (90% CI 0·94–1·37), this outcome met the prespecified definition of non-inferiority (non-inferiority p=0·017). Congruent results were found for disease-free interval, distant disease-free interval, distant disease-free survival, invasive disease-free survival, and breast-cancer specific survival analyses (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier plots of landmark analysis from 6-months after starting trastuzumab treatment

(A) Disease-free survival. (B) Overall survival.

During the 12-month period after starting trastuzumab, a higher proportion of 12-month patients (459 [24%] of 1894 patients) than 6-month patients (373 [19%] of 1939 patients, p=0·00020) reported at least one adverse event of severe grade (ie, CTCAE ≥3, or CTCAE=2 for palpitations; table 3). The excesses were in cough (82 [4·3%] of 1894 patients in the 12-month group vs 44 [2·3%] of 1939 patients in the 6-month group, p=0·00049), palpitations (91 [4·8%] vs 52 [2·7%], p=0·00072), fatigue (226 [11·9%] vs 167 [8·6%], p=0·00086), pain (98 [5·2%] vs 62 [3·2%], p=0·0029), chills (67 [3·5%] vs 40 [2·1%], p=0·0075), muscle or joint pain (215 [11·4%] vs 174 [9·0%], p=0·017), and nausea (35 [1·9%] vs 20 [1·0%], p=0·047; appendix p 13). These were seen predominantly during the 7–12-month period. Similarly, 67 serious adverse reactions were reported in 64 patients in the 12-month group and 34 events in 29 patients in the 6-month group; the excesses seen during the 7–12 month period. Clinical cardiac dysfunction was reported more commonly in the 12-month group (224 [11%] of 1968 patients) than in the 6-month group (155 [8%] of 1994 patients; p=0·00014; table 3). A small absolute difference in clinical cardiac dysfunction rates was observed in the first 6 months (p=0·018), with a larger difference during the 7–12-month period (p=0·00020). Trastuzumab was stopped early because of cardiac toxicity in 146 (8%) of 1894 patients in the 12-month group and 61 (3%) of 1939 patients in the 6-month group (p<0·0001).

Table 3.

Adverse events and cardiac monitoring over the two 6-month periods

|

12-month group |

6-month group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Months 1–6 | Months 7–12 | Total | Months 1–6 | Months 7–12 | ||

| Adverse event with severe* CTCAE grade | 459/1894 (24%) | 350/1894 (18%) | 259/1764 (15%) | 373/1939 (19%) | 370/1939 (19%) | 8/93 (9%) | |

| Serious adverse reaction to trastuzumab† | 64/2044 (3%) | 39/2044 (2%) | 25/2019‡ (1%) | 29/2041 (1%) | 28/2041 (1%) | 2/2015‡ (0·1%) | |

| Clinical cardiac dysfunction§ | 224/1968 (11%) | 164/1968 (8%) | 157/1936 (8%) | 155/1994 (8%) | 126/1994 (6%) | 96/1894 (5%) | |

| Stopped trastuzumab permanently due to cardiac toxicity | 146/1894 (8%) | 63/1894 (3%) | 83/1764 (5%) | 61/1939 (3%) | 60/1939 (3%) | 1/93 (1%) | |

| Cardiac death¶ | 7/2044 (<1%) | 0/2044 | 0/2019‡ | 4/2041 (<1%) | 0/2041 | 0/2015‡ | |

| Cardiac death related to trastuzumab¶ | 0/2044 | 0/2044 | 0/2019‡ | 0/2041 | 0/2041 | 0/2015‡ | |

| Low LVEF‖ | 228/2040 (11%) | 148/2040 (7%) | 151/1938 (8%) | 176/2038 (9%) | 146/2038 (7%) | 84/1749 (5%) | |

| Substantial falls in LVEF | |||||||

| Absolute decrease of ≥10% from baseline to <50% | 163/1959 (8%) | 98/1950 (5%) | 102/1873 (5%) | 132/1959 (7%) | 102/1954 (5%) | 60/1693 (4%) | |

| LVEF <50% after a baseline of ≥59% | 108/1959 (6%) | 63/1950 (3%) | 71/1873 (4%) | 86/1959 (4%) | 70/1954 (4%) | 32/1693 (2%) | |

Data are n/N (%). CTCAE=Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction.

CTCAE grade of 3 or more, or grade of 2 for palpitations.

Denominators exclude the three patients known not to have received trastuzumab.

Denominators reduced because of either deaths or withdrawal of consent for follow-up within the first 6 months.

Clinical cardiac dysfunction is defined as symptoms of cardiac disease, signs of congestive heart failure, use of new medication for cardiac disease, or a combination of these factors.

11 deaths were reported to have a cardiac cause, either first cause or contributory; none occurred during the first 12 months after starting trastuzumab treatment; nine patients died without metastatic disease and two had metastatic disease; in all cases, trastuzumab was considered unrelated or unlikely to be related with the cardiac problems.

Low LVEF was defined as ejection fraction of less than 50% or unknown ejection fraction but classified on report as not normal.

In total, 19 414 measurements of LVEF were made in 4078 patients: 10 162 in 2040 12-month patients and 9252 in 2038 6-month patients. During the first 6 months of treatment, proportions of patients with low LVEF were 7% in both groups (p=0·96). However, during months 7–12, this proportion increased for the 12-month group (8%) but decreased for the 6-month group (5%; p=0·0003 for difference between groups). During months 7–12, substantial decreases of LVEF to less than 50% after a baseline of 59% or more occurred in 71 (4%) of 1873 patients in the 12-month and 32 (2%) of 1693 patients in the 6-month group (p=0·0010). 11 deaths were considered cardiac (primary or contributory cause); however, none occurred during trastuzumab treatment and none were considered to be associated with trastuzumab by the TMG (appendix p 5, 6). Comparing the 1786 (44%) of 4088 patients randomised into the trial before the start of trastuzumab with all patients, the comparison of toxicity between the two treatment groups was broadly similar, although toxicity, including cardiotoxicity, showed marginally higher proportions of patients reporting these effects in both 6-month and 12-month treatment groups for patients randomised before the start of trastuzumab (appendix p 6).

3910 patients (1960 patients in the 12-month group, 1950 patients in the 6-month group) participated in the substudy assessing quality of life. In both groups, feelings of general health declined during the first 3 months of trastuzumab (appendix p 14), when 1816 (46%) of 3910 patients were receiving concurrent chemotherapy, and then steadily improved after completion of treatment. The EQ-5D-3L health state remained steady from baseline to 3 months for both randomised groups and appeared to slowly increase after this period, occurring slightly later for 12-month patients (appendix p 15).

Discussion

PERSEPHONE showed non-inferiority for 6 months of trastuzumab compared with 12 months. Our definition of non-inferiority was no worse than 3% absolute below the standard group's 4-year disease-free survival, and the non-inferiority limit was thus calculated as an HR of less than 1·32. Notably, the upper confidence limit of the HR was 1·24, which is statistically significantly below this non-inferiority boundary (non-inferiority p=0·011). This finding reflects that, although the non-inferiority boundary was set at 3%, the actual point estimate reduction observed was very small at 0·4% for 4-year disease-free survival and 0·1% for the landmark 4-year disease-free survival.

Other outcome analyses, including overall survival, landmark overall survival 6 months after the start of trastuzumab, and sensitivity analyses for other survival endpoints, were all congruent, showing the non-inferiority of 6-months treatment. In addition, fewer cardiac events and other toxic effects occurred with 6-month treatment and, therefore, the balance of risk and benefit favours shorter treatment. Notably, the patient population in PERSEPHONE, mapping onto standard practice in the clinic, had a substantially better profile of standard prognostic factors than patients treated in the original adjuvant trastuzumab trials.2, 3, 4, 5 The trial included 69% patients with oestrogen receptor-positive tumours compared with 36–54% in registration studies; 58% patients were node negative compared with 7–33%; and 47% had tumours of 2 cm or less compared with 35–40%. These standard prognostic factors are similar to those for patients entered into PHARE12 and the other non-inferiority trials.15, 16 PERSEPHONE recruited the number of patients specified in the statistical plan and with an event-driven analysis was sufficiently powered to meet the primary endpoint. To our knowledge, PERSEPHONE is the largest trastuzumab duration comparison study for early breast cancer and the only one to show non-inferiority for the primary endpoint of reduced duration adjuvant trastuzumab.

Before the set-up of the trial, the PERSEPHONE TMG and the patient and public involvement group agreed that an absolute difference up to 3% for the 6-month treatment was considered acceptable by clinicians and patients. This margin is commonly used in non-inferiority trials in oncology, including in the TAILORx study,26 published in 2018. Funders (which provided national and international peer review for the trial), National Research Ethics Committee, and each recruiting centre endorsed the view that showing this non-inferiority margin would be important and, if proven, would be potentially practice changing. In the PERSEPHONE statistical analysis plan, we planned to calculate the HR limit of non-inferiority using the observed 4-year disease-free survival in the standard group at the time of the primary endpoint analysis. This statistical analysis plan was approved by the IDSMC as most appropriate for the study.

Two other randomised studies compared treatment for 6 months with 12 months. The HORG14 study included only 481 patients and used a non-inferiority margin of 8% using dose-dense fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel as chemotherapy with 6 months or 12 months of trastuzumab commencing concurrently with docetaxel. This relatively small trial with low power did not show non-inferiority for 3-year disease-free survival. The PHARE trial12 had an original recruitment target of 7000 patients with a 2% non-inferiority margin. The trial included fewer patients than originally planned (n=3384) and reported an early primary endpoint of disease-free survival at 2 years on the advice of the IDSMC. The HR non-inferiority limit was prespecified at 1·15 on the expected standard group for a disease-free survival of 85% at 2 years. The trial reported an HR of 1·28 (95% CI 1·05–1·56; non-inferiority p=0·29) and, therefore, did not show non-inferiority. The longer-term results from PHARE27 were presented in December, 2018, after a median of 7·5 years and the HR was 1·08 (95% CI 0·93–1·25; non-inferiority p=0·39) with the upper confidence limit still exceeding the HR limit of 1·15. Therefore, the conclusion remained the same: non-inferiority was not confirmed. Although the HR at 7·5 years median follow-up is remarkably similar to that measured in the PERSEPHONE trial, each trial is correctly reported according to its own prespecified statistical analysis plan, and hence reported conclusions are different. The PERSEPHONE and PHARE trials groups established a collaboration at the start of the trials for an individual patient data meta-analysis or joint analysis, which will provide larger numbers for exploratory subgroup analyses.

Long-term follow-up of patients within the PERSEPHONE trial is planned. The importance of long-term follow-ups in trials of HER2-positive breast cancer has been emphasised by several studies in which results have changed with time. The longer-term follow-up of PHARE27 showed a reduction in the HR for disease recurrence or death compared with the 2-year results. In contrast, the FinHer study,28 which provided the stimulus for all the reduced duration trials, showed with longer follow-up28 less effect in terms of the HR for disease recurrence or death, which increased from 0·42 at 3 years to 0·65 with a median follow-up of more than 5 years. In addition, a presentation29 in 2018 from a combined analysis of the N9831 and NSABP B31 studies showed that the risk of recurrence after 5 years was higher in patients with oestrogen receptor-positive and HER2-positive breast cancer than those with oestrogen receptor-negative and HER2-positive disease; this finding is relevant for PERSEPHONE because of the inclusion of a high proportion of oestrogen receptor-positive patients. Longer follow-up in the PERSEPHONE trial will also be particularly important because changes in standard treatments during the trial mean that for concurrent, anthracycline with taxane-based, and neoadjuvant treatments, the follow-up will be on average shorter than for those receiving sequential, anthracycline-based and adjuvant treatment.

Two trials tested 9 weeks concurrent treatment versus 12 months and neither showed non-inferiority. SHORTHer15 randomly assigned 1253 patients and the non-inferiority limit for a less than 3% margin below standard treatment was an HR of less than 1·29 for the primary endpoint of disease-free survival at 5 years; the trial HR was 1·15 (90% CI 0·91–1·46). SOLD16 randomly assigned 2176 patients and the non-inferiority limit for a margin of less than 4% was an HR of less than 1·385 for the primary endpoint of disease-free survival at 5 years; the trial HR was 1·39 (90% CI 1·12–1·72). One potential explanation is that the total dose of trastuzumab in the 9-week group was 20 mg/kg, which is substantially less than the 56 mg/kg in PERSEPHONE, PHARE,12 and HORG.14 This total dose might be insufficient to produce a non-inferior outcome compared with 12 months, even when used concurrently with docetaxel immediately after surgery.

Heterogeneities between prespecified stratification subgroups are seen in the PERSEPHONE trial. For disease-free survival, there is apparent heterogeneity (p=0·0010) for timing of trastuzumab and chemotherapy: patients receiving concurrent treatment appeared to benefit more from standard 12 months of trastuzumab. This result is intriguing because we anticipated that concurrent rather than sequential timing of trastuzumab and chemotherapy would show non-inferiority on the basis of evidence of synergy of concurrent treatment from in-vitro data,30 and metastatic1 and adjuvant7, 12, 31 clinical trials. We cannot readily explain the heterogeneity measured in our trial for trastuzumab scheduling and duration, but it is important to note that the decision to use concurrent or sequential treatment was selected by investigators and not randomised. Given that patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy also generally had more high-risk features, it is not clear whether the observed heterogeneity is due to the treatment schedule itself, the type of chemotherapy used, or whether it reflects the underlying risk of relapse. However, although the trial was stratified by concurrent and sequential chemotherapy and subgroups are balanced in terms of numbers of patients receiving either 6 or 12 months trastuzumab, these subgroups are smaller and, therefore, lack statistical power. All patients in the concurrent group received either anthracycline and taxane combinations or taxane-based chemotherapy without anthracyclines. HERA2, 32 is the only trial reporting data for an exploratory subgroup analysis of a non-randomised comparison of sequential administration of trastuzumab after anthracycline and taxane, with trastuzumab after anthracycline without taxane chemotherapy Although trastuzumab appeared to be less efficacious in the anthracycline and taxane group than in the anthracycline alone group, this interaction was not found to be statistically significant. Although we acknowledge that any possible interaction between concurrent and sequential trastuzumab with chemotherapy might raise some concern, this subgroup analysis lacks statistical power for non-inferiority. The heterogeneity showed for different chemotherapy backbones is driven mainly by the taxane without anthracycline group and this result should be interpreted with caution given the small size of this group and the very small number of events. For overall survival in the PERSEPHONE trial, heterogeneity was also shown for oestrogen receptor status; patients with oestrogen receptor-negative disease appeared to benefit more from 12 months trastuzumab, which is perhaps not surprising given the increased risk of relapse in this group.

PERSEPHONE mapped onto standard practice in the UK and study strengths are broad inclusion criteria, which allowed recruitment of a large number of patients in routine clinics and ongoing recruitment as standard chemotherapy regimens and trastuzumab timing changed. The limitations of this design include the potential for complex interactions between trastuzumab duration and prognostic factors, the changing standard practice over the 8 years of the trial, the variable timing of randomisation potentially introducing ascertainment bias, and selection of chemotherapy and trastuzumab timing according to perceived risk by the investigators (ie, concurrent preferred in high-risk patients; appendix pp 2–4). An additional limitation that must be considered is that the analyses were done according to the intention-to-treat principle. Although we believe that this analysis is the most appropriate to use, ensuring unbiased estimates, it can potentially underestimate differences between treatment groups and thus drive the results towards non-inferiority. This limitation is a concern particularly when adherence to treatment is low, differential loss to follow-up occurs, or both. However, in the PERSEPHONE trial, adherence to protocol-mandated treatment is high and loss to follow-up is low.

All reduced-duration trastuzumab trials have shown less cardiotoxicity for the shorter duration.11, 15, 16 In addition, the HERA trial showed that 24 months of trastuzumab further increased rates of cardiotoxicity without improving cancer outcomes.5, 9 As part of the translational programme in PERSEPHONE, over 80% of patients have donated blood samples that will be part of a genome-wide association study of cardiotoxicity with investigation of interaction with duration of treatment.

Substantial changes to the management of HER2-positive early breast cancer over the past 13 years have occurred, since the concept for the PERSEPHONE trial was developed alongside the other duration trials. The trial was designed to be pragmatic, map onto standard practice, which allowed patients to continue to be enrolled since standard chemotherapy regimens and trastuzumab timings changed. Although this approach is an advantage for trial recruitment and ensures contemporaneity, one of the limitations of this design is that there will not be sufficient power in different subgroups to confirm non-inferiority. Following the report of N9831 in 2011,31 which showed superiority of concurrent trastuzumab and taxane chemotherapy over sequential trastuzumab, the use of concurrent treatments increased. Until 2011, the majority of patients in the UK received standard anthracycline-based regimens with sequential trastuzumab similar to those used successfully in HERA.2 The docetaxel, carboplatin, and herceptin regimen from the BCIRG 006 study4 and the adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab regimen33 which avoid anthracyclines, are now widely used in North America and are gaining acceptance in Europe, including the UK. The adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab regimen was developed in particular for patients with low-risk node-negative breast cancer and tested in a phase 2 non-randomised study.33 Only 403 (10%) patients in our study, who were enrolled mostly towards the end of the recruitment period, received non-anthracycline containing regimens, in whom very few events have been reported; therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about the effect of a short-duration trastuzumab treatment in combination with a non-anthracycline regimen.

Additional advances in the management of HER2-positive early breast cancer warrant consideration. Trials of neoadjuvant therapy can provide personalised HER2-directed therapies with potential for both escalation and de-escalation strategies. Use of dual anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) with chemotherapy has been increasing in the neoadjuvant setting following the Neo-SPHERE trial,34, 35 which showed improved pathological complete response and disease-free survival. In the Katherine trial,36 published in 2019, trastuzumab emtansine was tested against trastuzumab after the combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and anti-HER2 therapy did not result in a pathological complete response. The estimated percentage of patients who were free of invasive disease at 3 years was 88·3% in the trastuzumab emtansine group and 77·0% in the trastuzumab group. Invasive disease-free survival was significantly higher in the T-DM1 group than in the trastuzumab group (HR for invasive disease or death 0·50 [95% CI 0·39–0·64], p<0·001).36 This significant improvement in outcomes is likely to lead to an appropriate escalation of standard treatment in the post-neoadjuvant setting, at least for patients who do not achieve pathological complete response with neoadjuvant treatment. However, patients who do achieve a pathological complete response could be considered for trials that are planned for de-escalation of HER2 therapy. The APHINITY trial37 reported improved outcomes for the addition of 12-month adjuvant pertuzumab to 12-month trastuzumab treatment. The reduction in disease recurrence was relatively small, albeit statistically significant (HR 0·81 [95% CI 0·66–1·00], p=0·045) and subgroup analysis showed a larger effect for the node-positive subgroup. More precise prognostic or predictive classifications are urgently required38 so that the results of the de-escalation trials and those escalating treatment with dual HER2 therapy37 can be appropriately applied to optimise effectiveness while reducing toxicity and containing cost. As part of the translational research programme within the PERSEPHONE trial, over 80% of patients have donated formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumour tissue and germline blood, and our aim is to investigate whether it is possible to personalise trastuzumab duration taking into account germline and tumour genomics, as well as efficacy, toxicity, and standard prognostic factors.

In general, very substantial challenges remain to de-escalating effective treatments that have been used as standard for many years. An understandable reluctance on the part of both oncology teams and their patients to consider a change to practice, which has been established since 2005, is expected, despite the potential benefit for the individual patient of reduced toxicity, length of treatment, and a more rapid return to normal life. We are convinced that the optimal approach to evaluate shorter durations is to use registration trials, and we would strongly encourage such testing for new targeted adjuvant cancer therapies. Although we have shown non-inferiority for trastuzumab in the population we tested, discussion and intense debate about our results is ongoing, including whether or not these are applicable in 2019 compared with 2007 when the study was designed, because of the changes in standard treatments for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer that have occurred. Duration questions within registration trials could only occur with substantial high-level international collaboration between the pharmaceutical industry, international academic groups, and governments or medicines approval bodies (such as the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration), with input from the wider cancer specialist teams and patients with cancer, as has been discussed by Ponde and colleagues.39 If shorter treatments are found to be non-inferior by agreed statistical criteria at the outset, then these treatments will become the standard of care on licensing. The escalating cost of effective novel anti-cancer treatments is rapidly becoming unsustainable even for wealthy nations, and we believe clinical trials designed to test the non-inferiority of shorter treatments should become one of the priorities in cancer research.

In conclusion, in the PERSEPHONE trial, we have shown non-inferiority for 6-month adjuvant trastuzumab compared with 12-month treatment in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer. The observed absolute difference in the primary endpoint of disease-free survival at 4 years was only 0·4%. This result signals the potential of reducing treatment duration to 6 months and, thereby, toxicity and cost, while obtaining similar efficacy for at least some women with HER2-positive breast cancer. This trial provides a positive result and will stimulate substantial debate because it is the only reduced-duration study to show non-inferiority for shorter adjuvant trastuzumab treatment.

Data sharing

Data collected within the PERSEPHONE study will be made available to researchers whose full proposal for their use of the data has been approved by the PERSEPHONE Trial Management Group and whose research group includes a qualified statistician. The data required for the approved, specified purposes and the trial protocol will be provided, after completion of a data sharing agreement. Data sharing agreements will be set up by the sponsors of the trial, the funders, the trial coordination centre, and the Trial Steering and Management Groups. The data will be made available 2 years after publication. Please address requests for data to persephone@live.warwick.ac.uk.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (grant number 06/303/98). We acknowledge the 210 investigators and their teams from 152 participating UK centres who enrolled patients into the Persephone trial. Our gratitude also goes to the 4088 patients who kindly participated in our study. We wish to thank the independent members of the Trial Steering Committee, Tim Maughan, Richard Gray, and Adele Francis (deceased) for their expert guidance. We thank the Independent Data Safety and Monitoring Committee members: Richard Bell, Roger A'Hern, and Marianne Nicolson, who have provided independent, expert professional advice throughout the study on patient safety, data, and analysis. We thank the trials unit staff: phase 3 coordination at Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, Coventry, UK; translational coordination at University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK; and statistical analysis at Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, Coventry, UK. The trial conduct at UK sites would not have been possible without access to research nurses, data managers, and other research staff funded via the NHS research and development departments (National Institute for Health Research in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland; Scottish Cancer Research Network in Scotland). In addition, we especially thank Catherine Durance personal assistant to HME, for her expert secretarial assistance in manuscript preparation and all documentation related to submission. The views expressed are our and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Contributors

HME, LH, A-LV, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD contributed to the study conception. HME, LH, A-LV, CM, CH, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD wrote the grant. HME, LH, A-LV, MW, CP, JM, BM-A, EP, CM, CH, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD contributed to the study design. HME, LH, A-LV, SL, DH, HBH MW, BM-A, EP, AC, CM, CH, and JAD participated in the study set-up. HME, LH, A-LV, SL, HBH, DAC, and JAD contributed to the oversight of trial conduct. HME, LH, A-LV, SL, KM, LH-D, ANH, DR, KR, MW, CP, JM, JEA, CC, PSH, CM, CH, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD were members of the Trial Steering Committee. A-LV, SL, DH, and KR coordinated the trial. HME, LH, A-LV, SL, KR, HH, and JAD managed the trial. A-LV, SL, DH, and KR contributed to data collection. LH, CP, and DC analysed the data. HME, LH, MW, CP, IG, JEA, PSH, CM, CH, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD contributed to data interpretation. HME, LH, A-LV, SL, KM, LH-D, ANH, M-LA-S, RS, DR, SR, PW, MH, CP, JM, IG, BM-A, EP, AC, JEA, CC, PH, CM, CH, DM, AMW, DAC, and JAD wrote the paper. HME, LH, and JAD created the table and figures. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

HME reports grants from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme (HTA), during the conduct of the study; and grants from Roche and Sanofi-Aventis, personal fees and travel expenses from Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca, travel expenses from Pfizer and Amgen, and personal fees from Prime Oncology, all outside the submitted work. KM reports an educational grant from Roche, and was a member of the Advisory Board for the Aphinity study from Roche. M-LA-S is a full-time employee of AstraZeneca with associated share options. DR reports personal fees and grants from Roche, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Genomic Health, and Daiichi Sankyo, and grants from Celgene, all outside the submitted work. CP reports personal fees and non-financial support from Roche, Amgen Limited, Novartis, and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. IG reports being employed by Novartis, outside the submitted work. CC reports grants from Genentech, Roche, Servier, and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work, and is a member of AstraZeneca Innovative Medicines and Early Development external science panel. PSH reports grants from Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novaratis, Eisai, and Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work. CM reports that his institution received funding from NIHR for the design and implementation of the economic evaluation of this trial, and was employed by the University of Leeds for the first 4 years of the trial's operation, outside the submitted work. CH reports being a Member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board. DM reports personal fees from Roche-Genentech, outside the submitted work. AMW reports personal fees from Roche, Napp Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Pierre Fabre, Accord Healthcare, Athenex, Gerson Lehmann Group, Coleman Expert Network Group, and Guidepoint global, and personal fees and other support from Lilly and Daiichi Sankyo, all outside the submitted work; and is leading the National Cancer Research Institute Breast Group Initiative to develop the next de-escalation trial for HER2-positive breast cancer. DAC reports funds to his institution from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Eli Lilly, PUMA, Daiichi Sankyo, Synthon, Seagen, Zymeworks, Elsevier, European Cancer Organisation, Celgene, Succint Medical Communications, Prima BioMed, Oncolytics Biotech, Celldex Therapeutics, San Antonio Breast Cancer Consortium, Highfield Communication, Samsung Bioepis, prIME Oncology, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Prima BioMed, RTI Health Solutions, and Eisai, all outside the submitted work. LH, DH, KR, and JAD report grants from NIHR HTA Clinical Trials grant (Persephone) during the conduct of the study. A-LV, SL, LH-D, ANH, RS, SR, PW, MH, HBH, MW, JM, BM-A, EP, AC, and JEA have nothing to declare.

Contributor Information

Helena M Earl, Email: hme22@cam.ac.uk.

PERSEPHONE Steering Committee and Trial Investigators:

Roshan Agarwal, Hafiz Algurafi, Rozenn Allerton, Caroline Archer, Anne Armstrong, Catherine Bale, Lisa Barraclough, Urmila Barthakur, Carolyn Bedi, Kim Benstead, David Bloomfield, Rebecca Bowen, Chris Bradley, Jane Brown, Mohammad Butt, Mark Churn, Susan Cleator, Joanne Cliff, Perric Crellin, Margaret Daly, Shiroma De Silva-Minor, Amandeep Dhadda, Omar Din, Sue Down, Helena Earl, David Eaton, Andrew Eichholz, Daniel Epurescu, Chee Goh, Andrew Goodman, Robert Grieve, Maher Hadaki, Catherine Harper-Wynne, Mark Harries, Larry Hayward, Alison Humphreys, Helen Innes, Mariam Jafri, Apurna Jegannathen, Muireann Kelleher, Hartmut Kristeleit, Daniela Lee, Susan Lupton, Carol MacGregor, Zafar Malik, Janine Mansi, Jennifer Marshall, Karen McAdam, Trevor McGolick, Rakesh Mehra, David Miles, Natasha Mithal, Charlotte Moss, Aian Moss, Mukesh Mukesh, Anthony Neal, Daniel Nelmes, Helen Neville-Webbe, Jacqueline Newby, Susan O'Reilly, Peter Ostler, Mojca Persic, Laura Pettit, Sanjay Raj, Fharat Raja, Daniel Rea, Catherine Reed, Anne Rigg, Helen Roe, Nihal Shah, Peter Simmonds, Eliot Sims, Sarah Smith, Nicola Storey, Wendy Taylor, Narottam Thanvi, Karen Tipples, Jayant Vaidya, Mohini Varughese, Anup Vinayan, Nawaz Walji, Simon Waters, Pamela Woodings, Kathryn Wright, and Sundus Yahya

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 783–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1659–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1673–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1273–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1273–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD. 11 years' follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32616-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, et al. 11 years' follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 1195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3744–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3744–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:809–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Joensuu H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Bono P, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without trastuzumab for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 809–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Earl HM, Vallier AL, Dunn J. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events in the Persephone trial. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1462–1470. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Earl HM, Vallier AL, Dunn J, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events in the Persephone trial. Br J Cancer 2016; 115: 1462–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the Herceptin Adjuvant trial (BIG 1–01) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2159–2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.9288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the Herceptin Adjuvant trial (BIG 1–01). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2159–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Russell SD, Blackwell KL, Lawrence J. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy: a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3416–3421. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Russell SD, Blackwell KL, Lawrence J, et al. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy: a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3416–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Pivot X, Suter T, Nabholtz JM. Cardiac toxicity events in the PHARE trial, an adjuvant trastuzumab randomised phase III study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1660–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pivot X, Suter T, Nabholtz JM, et al. Cardiac toxicity events in the PHARE trial, an adjuvant trastuzumab randomised phase III study. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 1660–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pivot X, Romieu G, Debled M. 6 months versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHARE): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:741–748. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pivot X, Romieu G, Debled M, et al. 6 months versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHARE): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 741–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Earl HM, Cameron DA, Miles D. PERSEPHONE: duration of trastuzumab with chemotherapy in women with HER2-positive early breast cancer—six versus twelve months. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 15) [Google Scholar]; Earl HM, Cameron DA, Miles D, et al. PERSEPHONE: duration of trastuzumab with chemotherapy in women with HER2-positive early breast cancer—six versus twelve months. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32 (suppl 15): TPS667.

- 14.Mavroudis D, Saloustros E, Malamos N. Six versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with dose-dense chemotherapy for women with HER2-positive breast cancer: a multicenter randomized study by the Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG) Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1333–1340. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mavroudis D, Saloustros E, Malamos N, et al. Six versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with dose-dense chemotherapy for women with HER2-positive breast cancer: a multicenter randomized study by the Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG). Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1333–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Conte P, Frassoldati A, Bisagni G. Nine weeks versus 1 year adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy: final results of the phase III randomized Short-HER studydouble dagger. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2328–2333. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Conte P, Frassoldati A, Bisagni G, et al. Nine weeks versus 1 year adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy: final results of the phase III randomized Short-HER studydouble dagger. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 2328–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Joensuu H, Fraser J, Wildiers H. Effect of adjuvant trastuzumab for a duration of 9 weeks vs 1 year with concomitant chemotherapy for early human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: the SOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Joensuu H, Fraser J, Wildiers H, et al. Effect of adjuvant trastuzumab for a duration of 9 weeks vs 1 year with concomitant chemotherapy for early human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: the SOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 1199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Schneider BP, O'Neill A, Shen F. Pilot trial of paclitaxel-trastuzumab adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer: a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN cancer research group (E2198) Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1651–1657. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Schneider BP, O'Neill A, Shen F, et al. Pilot trial of paclitaxel-trastuzumab adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer: a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN cancer research group (E2198). Br J Cancer 2015; 113: 1651–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG, Group C. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594–2604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.87802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG, Group C. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 2012; 308: 2594–604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3997–4013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Jones AL, Barlow M, Barrett-Lee PJ. Management of cardiac health in trastuzumab-treated patients with breast cancer: updated United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute recommendations for monitoring. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:684–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jones AL, Barlow M, Barrett-Lee PJ, et al. Management of cardiac health in trastuzumab-treated patients with breast cancer: updated United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute recommendations for monitoring. Br J Cancer 2009; 100: 684–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP system. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2127–2132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, et al. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP system. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2127–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Mauri L, D'Agostino RB., Sr Challenges in the design and interpretation of noninferiority trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1357–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mauri L, D'Agostino RB Sr. Challenges in the design and interpretation of noninferiority trials. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1357–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group . Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1990. Treatment of early breast cancer: worldwide Evidence 1985–1990. [Google Scholar]; Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Treatment of early breast cancer: worldwide Evidence 1985–1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- 24.Jones SE, Collea R, Paul D. Adjuvant docetaxel and cyclophosphamide plus trastuzumab in patients with HER2-amplified early stage breast cancer: a single-group, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70384-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jones SE, Collea R, Paul D, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel and cyclophosphamide plus trastuzumab in patients with HER2-amplified early stage breast cancer: a single-group, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 1121–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Pivot X, Romieu G, Debled M, et al. PHARE randomized trial final results comparing 6 to 12 months of trastuzumab in adjuvant early breast cancer. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX; Dec 10–14, 2018. GS2–07.

- 28.Joensuu H, Bono P, Kataja V. Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide with either docetaxel or vinorelbine, with or without trastuzumab, as adjuvant treatments of breast cancer: final results of the FinHer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5685–5692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Joensuu H, Bono P, Kataja V, et al. Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide with either docetaxel or vinorelbine, with or without trastuzumab, as adjuvant treatments of breast cancer: final results of the FinHer Trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5685–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Chumsri S, Li Z, Serie DJ, et al. Incidence of late relapse in HER2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant trastuzumab: Combined analysis of NCCTG (Alliance) N9831 and NSABP (NRG) B31. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX; Dec 10–14, 2018. PD3–02.

- 30.Pegram MD, Slamon DJ. Combination therapy with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and cisplatin for chemoresistant metastatic breast cancer: evidence for receptor-enhanced chemosensitivity. Semin Oncol. 1999;26(suppl 12):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pegram MD, Slamon DJ. Combination therapy with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and cisplatin for chemoresistant metastatic breast cancer: evidence for receptor-enhanced chemosensitivity. Semin Oncol 1999; 26 (suppl 12): 89–95. [PubMed]

- 31.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE. Sequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4491–4497. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, et al. Sequential versus concurrent trastuzumab in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4491–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, et al. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed]