Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Initial formative years in every children's life are critical for their optimal development, as these frame the foundation of future well-being. With a varied prevalence of developmental delays (DDs) in the world and most of the studies representing the hospital-based data. The present study was aimed to find the prevalence and risk factors for DDs (domain wise) in children aged 2 months to 6 years in the rural area of North India.

METHODS:

This was a cross-sectional study in which a multistage random sampling technique was used. From 30 Anganwadi centers, 450 children aged 2 months–6 years were taken in the study. Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram screening tool developed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India, was used for developmental screening. Binary logistic regression analysis was done to identify the predictors for DDs (domain wise).

RESULTS:

Seventy-three (16.2%) children were found to have DDs and 60 (13.3%) children had the global DDs. About 84/421 (20.0%) children had cognitive delay, followed by 43/450 (9.6%) children who had delay in speech and language area. About 17/190 (8.9%) children had social delay while 26/407 (6.4%) children had hearing and vision impairment. Gross motor delay was seen in 24/450 (5.3%) children and 16/300 (5.3%) children had fine motor delay. Gestational age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] – 13.30), complications during delivery (AOR – 25.79), meconium aspiration (AOR – 12.81), and child never breastfed (AOR – 8.34) were strong predictors for the delay in different domains of developmental milestones.

CONCLUSION:

Socio-economic, ante-natal, natal and post-natal factors should be considered for prompt identification and initiation of intervention for DDs.

RECOMMENDATION:

There is a need for increasing awareness and knowledge of parents regarding the achievement of developmental milestones according to the age. A multipronged approach to the holistic treatment of developmentally delayed children for early intervention is required.

Keywords: Developmental delays, developmental milestones, Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram

Introduction

Early childhood is a crucial period when various skills such as motor, cognitive, language, social, and vision are acquired. Development milestones are age-specific tasks that children attain at a certain age.[1] However, for individual development, acquisition of various skills varies from child to child.[2,3] It is not only the interplay of genes that provide the framework for the development of the brain but also the child's physical and social environment that play the role equally.[4]

The developmental trajectories are often helpful to assess about any delays, if any. However, the assessment methods of these developmental delays (DDs) vary from county to country, for example, Germans use the term “performance deficits” for perceived single DD,[5,6,7] and USA and Canada focus on specific combinations of developmental disabilities that are displayed before the 18th birthday and affect three or more areas of daily functioning such as follows: capacity for independent living, economic self-sufficiency, learning, mobility, language receptive and expressive, self-care, and self-direction.[8] Earlier studies considered development delays independently and laid focus on motor and language development on the one side[6] and cognitive or mental delays in specific patient populations on the other side.[9,10] However, studies by Bishop[11] and Nicolson and Fawcett[12] observed a combination of delays in children.

In India, it is defined as “Delay in any gross motor, fine motor, speech and language, cognitive and social, hearing and vision domain in a young child's development compared to other children. When this occurs in one area it is said to be 'Focal Delay' while delay in more than one area is called as “Global Developmental Delay.”[13]

Globally, around 250 million (43%) children under 5 years of age are unable to reach their developmental potential due to poverty, poor health, and lack of stimulation.[4] Across the world, 1.5%–19.8% of children are afflicted with DDs. The prevalence of DDs in children in India is approximately 10% and is even more in children who get discharged from the sick newborn unit.[13]

According to a survey by the INCLEN trust, 5.4% of children have hearing impairment, 4.79% have cognitive delay, 5%–10% have vision impairment, and 5%–8% have speech and language delay.[13]

The screening tools used in India for the assessment of these delays are mostly of international origin and validated in high-income countries. They are later translated into Indian languages. These tools are often culturally incongruous and after translation lose their explication.[14]

To countermand the impact of tribulation on the child's development and corroborating a healthy future for all children, in 2013, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India, launched a program Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) which aims at screening for defects at birth, diseases, deficiencies, and development delays including disabilities (4Ds) in children between 0 and 18 years. RBSK screening tool for developmental milestones and early intervention services intent to improve the quality of life and survival outcomes of “at risk” children.[13] To optimize good health care for children and their families, early detection and timely intervention for children with DDs or disorders is an essential part.[15,16] However, due to delay in identifying, access to early intervention services gets limited and they receive intervention when the children with DDs present with manifested functional disabilities.[17]

As many previous validated studies have been conducted on high-risk children in clinical settings,[18,19,20] we planned to conduct our study in a community-based setting. According to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has used RBSK screening tool to assess the developmental milestones in children; keeping these things in mind, the following objectives for the study were framed:

To assess the proportion of DDs using RBSK screening tool, in children <6 years of age in rural area of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

To assess the factors influencing the developmental milestones in the study population.

Materials and Methods

The study was undertaken after the approval by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the University. It was a cross-sectional study conducted at Anganwadi center (AWC) of rural area of North India from September 2016 to August 2017 on children enrolled at the AWCs along with their caregivers/parents. Since the expected prevalence for DDs in children is 10%[13] and the participants were chosen by multistage random sampling, a design effect of 2 along with a 4% margin of error of the prevalence was taken for sample size calculation. Thus, the sample size came out to be 434, but we enrolled 450 children in the study.

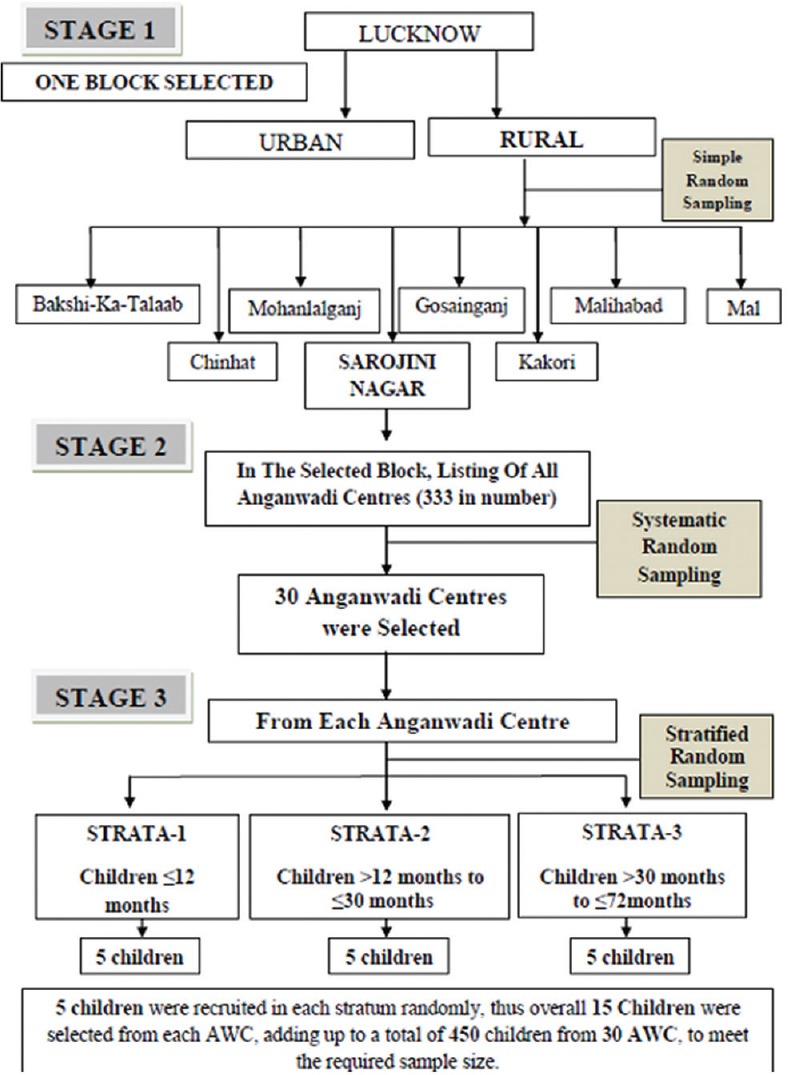

Multistage random sampling technique was used to recruit children from that rural area. Lucknow is divided into eight blocks, out of which one block was selected randomly using the lottery method. In the selected block, the list of all AWCs was taken from Child Development Project Officer. There were around 333 AWCs in the selected block out of which 30 AWCs were selected using a systematic random sampling technique.

First, sampling interval was calculated by dividing the total number of AWCs which were 333 in the selected block by the number we wanted in the sample i.e., 33. The sampling interval came out to be 10. Then, a number i.e., 7, was selected between 1 and 10 (sampling interval) using the random number tables The list of AWCs was arranged in alphabetical order, and thus, the 7th AWC was the first selected center. The second selected AWC was 7 + 10 = 17, next 27, 37, and so on till the desired number of AWCs were selected to cover the targeted sample size.

The list of children enrolled at each selected AWCs was obtained from the Anganwadi worker of the selected AWCs. To ensure the representation of different age groups according to the RBSK screening tool for DDs,[13] stratified random sampling was done and children were divided into three age groups (<12 months, ≥12–<30 months, and ≥ 30–≤72 months). From the list of children registered at the selected AWCs, the children were randomly selected according to the strata groups, thus in each strata 5 children were recruited, that made the total of 15 children from each AWC In each stratum, 5 children were recruited thus from each AWC in total 15 children were selected [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sampling technique

The criteria for inclusion were all children aged 2 months–6 years registered in the selected AWCs and whose caregivers/parents have been residing in the area of the selected AWC for >6 months and have consented for the study. Children who were unavailable even after the third visit at the AWC and suffered from acute illnesses that require immediate hospitalization were excluded from the study.

A predesigned and pretested interview schedule was used for data collection that consisted of biosocial information, family details, antenatal, natal and postnatal history, and history of breastfeeding practices of the index child. For assessing DDs in children aged 2 months–6 years, RBSK screening tool cum referral card was used. The tool has total 61 questions pertaining to different domains of developmental milestones. For quick identification of the DDs, three ways were used. First, some questions were directly observed; second, some questions were asked from caregiver/parents about the child; and third, the child was asked to perform developmental domain-related activity according to his/her age. Children who were found to have the DD or global DD (GDDs) were referred to the tertiary care center for appropriate management.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 23 (SPSS-23, IBM, Chicago, USA) was used for data processing and statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were presented in mean ± standard deviation (for quantitative data) and the frequency with percentages (for categorical data). Association between categorical variables was tested using Chi-square test. In case, the expected frequency was found to be <5; in any particular cell, Fischer exact test was used.

Factors found to be statistically significant in univariate logistic regression analysis were subjected to multivariate logistic regression (Backward Wald) for adjustment and controlling the effect of confounding variables to determine the predictors for DD domain-wise. Results were presented in terms of odds ratio and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) in a univariate and multivariate analysis. A minimum 95% confidence interval or P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

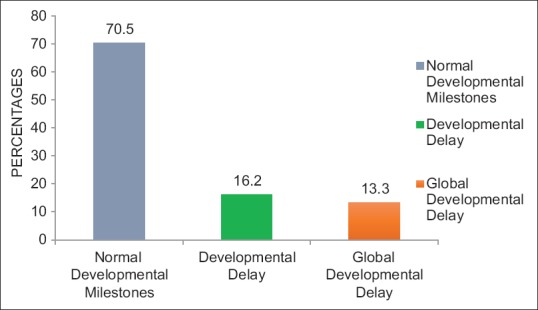

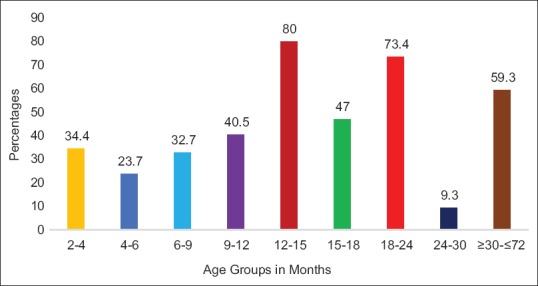

Of the total 450 children who were screened, 232 (51.6%) were male and 218 (48.4%) were female. Majority of the respondents, i.e. 440 (97.8%) were mothers. The mean age of mothers at the time of childbirth was 24.48 ± 4.25 years, while fathers' mean age was 28.04 ± 5.00 years. Table 1 shows the detail biosocial characteristics of the study participants. In this study, 317 (70.5%) children had normal developmental milestones, 73 (16.2%) children had DDs, while 60 (13.3%) children had GDDs [Figure 2]. Overall maximum (20%) delay was seen in cognitive domain and least (2%) in vision area. Majority (80%) children aged 12–15 months had DDs, while very few (9.3%) children belonging to the age group of 24–30 months had DDs [Figure 3].

Table 1.

Biosocial characteristics of the study children

| Biosocial characteristics | Children (N=450), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 432 (96.0) |

| Muslim | 18 (4.0) |

| Social group | |

| OBC | 156 (34.7) |

| SC/ST | 234 (52.0) |

| Others | 60 (13.3) |

| Type of family | |

| Nuclear | 169 (37.6) |

| Joint | 210 (46.7) |

| Three generation | 71 (15.8) |

| Marital status of parents | |

| Married | 443 (98.4) |

| Separated | 3 (0.07) |

| Widow/widower | 4 (0.09) |

| Educational profile of mother | |

| Illiterate | 121 (27.8) |

| Primary level | 95 (20.2) |

| Middle school | 83 (18.4) |

| High school | 55 (12.2) |

| Intermediate | 48 (10.7) |

| Graduate and above | 48 (10.7) |

| Educational profile of father | |

| Illiterate | 78 (17.3) |

| Primary level | 67 (14.9) |

| Middle school | 119 (26.4) |

| High school | 107 (23.8) |

| Intermediate | 35 (7.8) |

| Graduate and above | 44 (9.8) |

| Socioeconomic status* | |

| Upper | 31 (6.9) |

| Upper middle | 126 (28.0) |

| Middle | 161 (35.8) |

| Lower middle | 104 (23.1) |

| Lower | 28 (6.2) |

*According to Modified B.G. Prasad classification 2017

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing distribution of the children according to the status of their developmental milestones

Figure 3.

Age group-wise distribution of developmental delays in children

Gross motor delays (GMD) were maximum (10.3%) in children in 2–4 months' age group, while fine motor delay (FMD) was seen maximum (25%) in 4–6 months' age group. Majority (15.2%) children belonging to 6–9 months' age group had delay in speech and language area. About 17.6% children in 9–12 months' age group had delay in social area. Mostly 25.7% children in 12–15 months' age group, 23.7% children in 18–24 months' age group, 4.7% children in 24–30 months' age group, and 34.7% children in ≥30 months' age group had cognitive delay [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of children according to their age groups and developmental delays in different domains

| Domains | Age groups (in months) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-4 (n=29) | 4-6 (n=38) | 6-9 (n=46) | 9-12 (n=37) | 12-15 (n=35) | 15-18 (n=34) | 18-24 (n=38) | 24-30 (n=43) | ≥30-≤72 (n=150) | Total | |

| Gross motor (n=450) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 26 (6.1) [89.7] | 37 (8.7) [97.4] | 45 (10.6) [97.8] | 36 (8.5) [97.3] | 34 (8.0) [97.1] | 32 (7.5) [94.1] | 38 (8.9) [100.0] | 43 (10.1) [100.0] | 135 (31.7) [90.0] | 426 [94.7] |

| Delay | 3 (12.5) [10.3] | 1 (4.2) [2.6] | 1 (4.2) [2.2] | 1 (4.2) [2.7] | 1 (4.2) [2.9] | 2 (8.3) [5.9] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 15 (62.5) [10.0] | 24 [5.3] |

| Fine motor (n=300) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 28 (9.9) [96.6] | 34 (12.0) [89.5] | 46 (16.2) [100.0] | 35 (12.3) [94.6] | 33 (11.6) 9[4.3] | 32 (11.3) [94.1] | 34 (12.0) [89.5] | 42 (14.8) [97.7] | NA* | 284 [94.7] |

| Delay | 1 (6.3) [3.4] | 4 (25.0) [10.5] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 2 (12.5) [5.4] | 2 (12.5) [5.7] | 2 (12.5) [5.9] | 4 (25.0) [10.5] | 1 (6.3) [2.3] | 16 [5.3] | |

| Hearing (n=407) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 28 (7.3) [96.6] | 38 (10.0) [100.0] | 45 (11.8) [97.8] | 34 (8.9) [91.9] | 29 (7.6) [82.9] | 31 (8.1) [91.2] | 29 (7.6) [76.3] | NA* | 147 (38.6) [98.0] | 381 [93.6] |

| Delay | 1 (3.8) [3.4] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 1 (3.8) [2.2] | 3 (11.5) [8.1] | 6 (23.1) [17.1] | 3 (11.5) [8.8] | 9 (34.6) [23.7] | 3 (11.5) [2.0] | 26 [6.4] | |

| Speech (n=450) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 26 (6.4) [89.7] | 37 (9.1) [97.4] | 39 (9.6) [84.8] | 36 (8.8) [97.3] | 33 (8.1) [94.3] | 29 (7.1) [85.3] | 32 (7.9) [84.2] | 42 (10.3) [97.7] | 133 (32.7) [88.7] | 407 [90.4] |

| Delay | 3 (7.0) [10.3] | 1 (2.3) [2.6] | 7 (16.3) [15.2] | 1 (2.3) [2.7] | 2 (4.7) [5.7] | 5 (11.6) [14.7] | 6 (14.0) [15.8] | 1 (2.3) [2.3] | 17 (39.5) [11.3] | 43 [9.6] |

| Vision (n=300) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 29 (9.9) [100.0] | 38 (12.9) [100.0] | 43 (14.6) [93.5] | 36 (12.2) [97.3] | NA* | NA* | NA* | NA* | 148 (50.3) [98.7] | 294 [98.0] |

| Delay | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 3 (50.0) [6.5] | 1 (16.7) [2.7] | 2 (33.3) [1.3] | 6 [2.0] | ||||

| Social (n=190) | ||||||||||

| No delay | 27 (15.6) [93.1] | NA* | 42 (24.3) [91.3] | 34 (19.7) [91.9] | 27 (15.6) [77.1] | NA* | NA* | 43 (24.9) [100.0] | NA* | 173 [91.1] |

| Delay | 2 (11.8) [6.9] | 4 (23.5) [8.7] | 3 (17.6) [8.1] | 8 (47.1) [22.9] | 0 (0.0) [0.0] | 17 [8.9] | ||||

| Cognition (n=421) | ||||||||||

| No delay | NA* | 35 (10.4) [92.1] | 45 (13.4) [97.8] | 33 (9.8) [89.2] | 26 (7.7) [74.3] | 30 (8.9) [88.2] | 29 (8.6) [76.3] | 41 (12.2) [95.3] | 98 (29.1) [65.3] | 337 [80.0] |

| Delay | NA* | 3 (3.6) [7.9] | 1 (1.2) [2.2] | 4 (4.8) [10.8] | 9 (10.7) [25.7] | 4 (4.8) [11.8] | 9 (10.7) [23.7] | 2 (2.4) [4.7] | 52 (61.9) [34.7] | 84 [20.0] |

*RBSK screening tool for developmental delays does not have any question pertaining to the following domain in particular age group. ()=Parentheses show row percentages, []=Parentheses show column percentages. NA=Not applicable, RBSK=Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram

The biosocial factors, gestational factors, and factors related to breastfeeding practices were assessed to know their relationship with developmental milestones. On exploratory analysis, factors which were found to be significant on univariate analysis out of those, 3 biosocial, 12 gestational, and 4 breastfeeding practice factors had a significant association (P < 0.05) with different domains of DDs. Factors such as religion, social groups, type of family, marital status of parents, mother's education level, parent's occupation, socioeconomic group, parity, mode of delivery, umbilical cord wrapped around child's neck, early initiation of breastfeeding, and exclusive and extended breastfeeding were found to be statistically insignificant (P > 0.05).

Predictors for gross motor delay

Meconium aspirated children had 4.73 times more risk of developing GMD (AOR – 4.73, P = 0.034). Children who did not receive colostrum and children who were given complementary feeds after 12 months had >3 times higher risk of developing GMD (AOR – 3.86, P = 0.013 and AOR – 3.97, P = 0.014) [Table 3a].

Table 3a.

Predictors for delay in gross motor, fine motor, and hearing and vision domains

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| GMD | ||||||

| Gestational age | 0.009 | |||||

| Preterm | 4.72 | 1.73-12.89 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| Postterm | 2.53 | 0.30-21.17 | 0.390 | - | - | - |

| Term | Reference | |||||

| Meconium aspiration | ||||||

| Yes | 12.193 | 3.72-39.19 | <0.001 | 4.73 | 1.12-19.95 | 0.034 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Birth weight | 0.003 | |||||

| Very low | 10.45 | 2.32-47.04 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| Low | 0.39 | 0.90-1.71 | 0.213 | - | - | - |

| Normal | Reference | |||||

| Child ever breastfed | ||||||

| No | 6.9 | 2.04-23.30 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Colostrum given | ||||||

| No | 4.23 | 1.72-10.45 | 0.002 | 3.86 | 1.33-11.17 | 0.013 |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Complementary feeding (m) | 0.027 | 0.034 | ||||

| <6 | 1.52 | 0.41-5.58 | 0.531 | 1.03 | 0.25-4.20 | 0.962 |

| >12 | 4.19 | 1.48-11.89 | 0.007 | 3.97 | 1.31-11.65 | 0.014 |

| 6-12 | Reference | |||||

| FMD | ||||||

| Gestational age | 0.022 | 0.046 | ||||

| Preterm | 4.72 | 1.38-16.19 | 0.013 | 3.03 | 0.77-11.81 | 0.110 |

| Postterm | 5.90 | 0.60-57.35 | 0.126 | 13.30 | 1.12-157.07 | 0.040 |

| Term | Reference | |||||

| Meconium aspiration | ||||||

| Yes | 15.44 | 3.83-62.06 | <0.001 | 12.81 | 2.88-56.93 | 0.001 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Neonatal complications in child | ||||||

| Yes | 6.00 | 1.90-18.96 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Prelacteal feeds given | ||||||

| No | 0.25 | 0.07-0.96 | 0.038 | 0.24 | 0.06-0.96 | 0.044 |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Hearing and Vision Impairment | ||||||

| Complications in mother during delivery | ||||||

| Yes | 2.66 | 1.27-5.56 | 0.010 | 25.79 | 2.15-308.64 | 0.010 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Birth injury | ||||||

| Yes | 24.93 | 2.20-282.96 | 0.009 | 2.67 | 1.26-5.69 | 0.010 |

| No | Reference | |||||

GMD=Gross motor delay, FMD=Fine motor delay, CI=Confidence interval, OR=Odds ratio, AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio, Binary logistic regression analysis used

Predictors for fine motor delay

Postterm children had 13 times and preterms had 3 times more risk of developing FMD (AOR – 13.30, P = 0.040 and AOR – 3.03, P = 0.110) than term children. Children who aspired meconium during natal period were found to have 12 times more risk of having FMD (AOR – 4.73, P = 0.034). Children who were not given prelacteal feeds showed protection toward developing FMD than prelacteal fed children (AOR – 0.24, P = 0.044) [Table 3a].

Predictors for delay in hearing and vision

As shown in Table 3a, complications in mothers at the time of delivery and birth injury exhibited substantial association with delay in hearing and vision areas (AOR – 25.79, P = 0.010 and AOR – 2.67, P = 0.010).

Predictors for delay in speech and language

When the combined effect of factors was assessed for delay in speech and language area, large family size (AOR-2.18, P=0.037), delivery conducted by Dai (AOR-5.14, P=0.007), Nurse/Auxillary Nurse Midwife (AOR=2.43, P-0.038), complication during delivery (AOR- 2.54, P-0.018), meconium aspiration (AOR=3.81, P-0.058) and child never breastfed (AOR-8.35, P=0.002) were found to be strong predictors [Table 3b].

Table 3b.

Predictors for delay in speech and language, social, and cognitive domains

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Speech and language delay | ||||||

| Family size | ||||||

| Small | 1.95 | 1.04-3.67 | 0.038 | 2.18 | 1.05-4.56 | 0.037 |

| Large | Reference | |||||

| Medication Intake by the mother during antenatal period | ||||||

| Yes | 2.20 | 1.11-4.39 | 0.024 | - | - | - |

| No | Reference | |||||

| ANC services availed by the mother | ||||||

| No | 0.24 | 0.06-0.99 | 0.049 | - | - | - |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Delivery conducted by | ||||||

| Dai | 3.87 | 1.49-10.06 | 0.006 | 5.15 | 1.57-16.86 | 0.007 |

| Nurse/ANM | 1.96 | 0.96-3.99 | 0.066 | 2.43 | 1.05-5.61 | 0.038 |

| Doctor | Reference | |||||

| Complications in mother during delivery | ||||||

| Yes | 2.27 | 1.18-4.37 | 0.014 | 2.54 | 1.17-5.49 | 0.018 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Meconium aspiration | ||||||

| Yes | 5.82 | 1.86-18.24 | 0.003 | 3.81 | 0.96-15.24 | 0.058 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Child ever breastfed | ||||||

| No | 4.74 | 1.56-14.35 | 0.006 | 8.346 | 2.17-32.08 | 0.002 |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Colostrum given | ||||||

| No | 2.98 | 1.40-6.34 | 0.005 | - | - | - |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Complementary feeding (m) | ||||||

| <6 | 0.30 | 0.09-1.06 | 0.061 | - | - | - |

| >12 | 0.30 | 0.13-0.71 | 0.006 | - | - | - |

| 6-12 | Reference | |||||

| Social Delay | ||||||

| Children in family | ||||||

| >2 | 3.59 | 1.13-11.35 | 0.030 | 3.72 | 1.05-13.14 | 0.041 |

| ≤2 | Reference | |||||

| Accident/fall during pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 5.96 | 1.34-26.44 | 0.019 | 9.43 | 1.99-44.71 | 0.005 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Child ever breastfed | ||||||

| No | 7.20 | 1.55-33.30 | 0.012 | 6.62 | 1.28-34.09 | 0.024 |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Cognitive Delay | ||||||

| Children in family | ||||||

| >2 | 2.31 | 1.18-4.54 | 0.015 | 2.90 | 1.31-7.50 | 0.004 |

| ≤2 | Reference | |||||

| Father’s education | 0.049 | 0.015 | ||||

| Illiterate | 2.20 | 0.99-4.88 | 0.053 | 3.30 | 1.45-6.14 | 0.040 |

| Up to high school | 1.10 | 0.55-2.20 | 0.784 | 0.96 | 0.45-2.07 | 0.922 |

| Above high school | Reference | |||||

| Gestational age | 0.030 | 0.036 | ||||

| Preterm | 2.35 | 1.08-5.11 | 0.030 | 2.07 | 0.84-5.12 | 0.114 |

| Postterm | 2.99 | 0.82-10.90 | 0.096 | 5.99 | 1.13-31.47 | 0.035 |

| Term | Reference | |||||

| Prolonged labor | ||||||

| Yes | 2.65 | 1.55-4.51 | <0.001 | 2.83 | 1.57-5.09 | 0.001 |

| No | Reference | |||||

| Child cry (min) | 0.003 | 0.015 | ||||

| After 5 | 2.35 | 1.41-3.89 | 0.001 | 2.32 | 1.31-4.10 | 0.004 |

| Within 1-5 | 1.03 | 0.40-2.62 | 0.958 | 1.71 | 0.62-4.70 | 0.299 |

| Immediately or within 1 | Reference | |||||

| Child ever breastfed | ||||||

| No | 0.15 | 0.05-0.44 | <0.001 | 4.48 | 1.27-15.84 | 0.020 |

| Yes | Reference | |||||

| Complementary feeding (m) | 0.003 | 0.011 | ||||

| <6 | 0.70 | 0.30-1.64 | 0.413 | 0.58 | 0.23-1.45 | 0.242 |

| >12 | 3.033 | 1.52-6.04 | 0.002 | 2.84 | 1.28-6.30 | 0.010 |

| 6-12 | Reference | |||||

CI=Confidence interval, OR=Odds ratio, AOR= Adjusted Odds Ratio, Binary logistic regression analysis used, ANM=Auxillary Nurse Midwife

Predictors for social delay

Univariate analysis possible predictor variables such as more than two children in the family, child never breastfed, and accident/fall during pregnancy for delay in social area were confirmed on multiple logistic regression analysis (AOR – 3.72, P = 0.041; AOR – 6.62, P = 0.024; and AOR – 9.43, P = 0.005) [Table 3b].

Predictors for cognitive delay

More than two children in family and children of illiterate fathers had 2.5–3.3 times more risk of having cognitive delay (AOR – 3.30, P = 0.004 and AOR – 2.53, P = 0.040). Gestational factors such as prolonged labor and child cry after 5 min were strong predictors for delay in cognition (AOR – 2.82, P = 0.001 and AOR – 2.32, P = 0.004). Children who were never breastfed and were postterm had more risk of developing cognitive delay (AOR – 4.48, P = 0.020 and AOR – 5.99, P = 0.035). Additional predictor was children who were given complementary feeds after 12 months (AOR – 2.84, P = 0.010) [Table 3b].

Discussion

There have been extensive studies conducted on assessing the DDs in the Western world, but there is a paucity of literature in our country as previous studies mostly have been done in clinical settings and the prevalence of DDs at community level goes unknown. The present study is the first of its type to assess DDs in all the domains using RBSK screening tool for assessing developmental milestones in children.

There are wide variations in the prevalence of DDs across the world ranging from 1.5% to 19.8%;[21,22,23,24,25] this might be due to the use of different tools for assessing developmental milestones and studies conducted in different regions. The prevalence of children with DDs in the present study was 16.2%, and children with GDDs was 13.3%. Results from our study indicate that majority (84/421, 20.0%) children had cognitive delay, while 8.9% (17/190) children had social delay. The strikingly higher percentages in these domains might be due to the reason that the study was conducted in a rural area, where parent's education level is low, and they do not have any idea about the importance of cognitive skills, thus, they were unable to evoke learning skills in their children. Moreover, children were not even attending the Anganwadi centers regularly and thus they were deprived of learning environment leading to hindrance in problem-solving ability.

The prevalence of children with delay in speech and language domain was 9.6% (43/450), and the findings are supported by earlier work[26,27,28,29,30,31] that reports prevalence ranging from 3.9%–27.0%. One important reason that we encountered for delay in seeking treatment among such children was that the parents were taking treatment for these children from quacks, and most of them had this myth that by 5–6 years of age, the child will automatically speak normally, that delayed the best possible time of intervention.

Our study confirms the findings from several other studies[21,32,33,34] that reported the prevalence of GMDsand FMDs ranging from 4% to 9.7%.

On looking up for the factors associated with DDs, our study buttresses the same findings from previous literature[24,33,35,36] in regard to gender that there was no relationship between gender and DDs; however, there are few studies[28,37,38,39,40] that have identified male sex associated with high risk of having DDs.

In our study, most of the mothers had low education level, but surprisingly, mother's education was not significantly associated with any of the DDs, the result was in accordance to the findings of Lisbeth et al. However, the results from previous studies[38,41,42,43,44] are in contradiction with the above results. Although it has been proved in past that parent's education and mother's vocabulary are strong predictors for cognitive development in children,[45] it is evident from our study that children of illiterate father had >3 times odds of developing cognitive delay, thus father's education is cardinal for cognitive development in children, and the results are in consonance with the study by Jorien et al.[5]

Having more children in family poses a higher risk of developing social and cognitive delay in the current study which is supported by the work of Nilay et al.[46] and Astrid Alvik[47] that reported a significant association between number of children in family and fine motor skills and children with older siblings having low IQ scores. The reason might be that parents were unable to focus on one child completely.

Our study reflects that small family size contributes to higher risk of developing speech and language delay which was incongruent with the study by Sidhu et al.[30] where large family size was risk for delay in speech and language area. The possible reason for this could be that as the present study was carried out in a rural area with low education level of parents. Therefore, parents were not actively involved in conversation, reading books or telling stories to the children because of household chores and other works, thus due to lack of time they were unable to provide suitable environment to children for enhancing speech and language skills. Whereas if the family would have been large, interaction of children with other family members wouldn't have made them deprived of such situations. On exploring other variables, age of the mother at the time of pregnancy and parental occupation was found to be insignificant with any of the DDs in the study.

Antenatal factors such as parity, illness in mother, addictive habits, and X-ray exposure were not found to be significant with any of the developmental domains. However, mothers who experienced accident or fall during pregnancy had more chances of developing social delay. The likely reason could be that after accident or fall, the mother might have developed abruptio placentae that led to low birth weight (LBW) or birth asphyxia which likely coaxed delay in social domain of children. Previous studies[48,49,50,51] have investigated the relationship between gestational ages with child development and suggest the correlation between prematurity with DDs and GDDs; our study also endorses similar trend, but it further reflects that gestational age is a strong risk factor for FMD and cognitive delay. In fact, postterm children had even more risk than preterm children of developing delay in fine motor and cognitive domain in comparison to term children, which was also documented by Marroun et al. study.[52] However, this was in contradiction to the study done by Olesen et al.[53] where children born postterm achieved the assessed developmental milestones at the scheduled time.

Mode of delivery in our study showed no associations with any domain of developmental milestones which was consistent with the findings of previous studies.[34,48,50] Prolonged labor, delivery conducted by Dai, ANM/nurse, perinatal complications, and birth injury were found to be significant predictors for development delays. However, place of delivery and induced labor and umbilical cord wrapped around child's neck at time of birth was not associated with any of the developmental domain.

In the current study, children who aspirated meconium, 35.7% of them had GMD and 35.7% had delay in speech and language domain respectively while 40.0% children had FMD. Beligere et al.[54] also reported similar findings in their study, where 41.0% children of meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) had mild hypotonia and mild speech delay while 7% children of MAS had cerebral palsy. After adjusting for other factors, meconium aspiration was still a strong predictor for all the three developmental domains. As previous literature[55,56] clearly describes the mechanism of meconium aspiration leading to airway obstruction and pulmonary hypertension resulting in hypoxia and further leading to brain injury and hypoxemic-ischemic encephalopathy; therefore, despite adequate respiratory support given to children, there are chances of developing neuromotor impairment later in life. Furthermore, birth asphyxia has also been shown as a strong predictor for DDs in children in earlier works;[48,49,51,57,58] and in our study also, the prevalence of birth asphyxia was 10% which was consistent with the previous Indian work.[50,59] We also explored that developmentally delayed children had more than two times risk of having cognitive delay, which is possibly due to the reason that most of the deliveries were conducted by nurse, ANM, or Dai, who are still not that much skilled enough to adequately resuscitate the newborn at the time of birth resulting in hypoxic injury to the brain. In the current study, there were 91 (20.3%) children who had low birth weight (LBW), among those 91, 15.4% children had DDs and GDDs respectively while there were 8 (1.8%) children with very low birth weight (VLBW), in them, 25% children had DDs and GDDs. After adjusting for other factors, it was seen that LBW children were having >10 times risk of developing delay in gross motor area, which was concurrent with meta-analysis done by Kiviet et al.[60] A study by Ballot et al.[61] showed DD in 6.6% of very LBW children with no significant change in the cognitive or motor assessments in paired assessments, but the language score was significantly reduced. Thus, LBW remains to be an important risk factor for DDs which can easily be prevented by regular monitoring and better nutrition. It was also seen that there was a significant association between neonatal illness with FMD and the results were steady with the study by Vora et al.[22], where respiratory problems, sepsis, seizures significantly associated with DDs. Neonatal seizure as a contributory factor for DDs was also shown by Chattopadhayay et al.[62] Since we clubbed all the illnesses into one, so we could not separately associate which neonatal illness was more important in causing DDs or GDDs, however further detail evaluation of illnesses in contributing to delays in developmental milestones is required.

On evaluation of breastfeeding factors, a lot of literature describes the protective role of two fatty acids found in breast milk, namely docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid, on the development of nerve cells, retina, and the brain.[63,64,65] Our study also adds further that children who were never breastfed had more chances of developing delay in speech and language area, social domain, and cognitive areas. Children who were deprived of colostrum most of them had GMD. However, earlier authors[66,67,68] have shown strong correlation between colostrum and achieving cognitive skills. Delay in gross motor area and cognition was also seen in children who were offered late complementary feeds. The possible reason that was derived from the study was as most children belong to Hindu religion which has this belief that thickened and viscous colostrum can pose difficulty in swallowing and thus mostly it is discarded until true milk comes in. This also gives room for prelacteal feeds, which in our study is significantly associated with delay in fine motor domain; children who were not given prelacteal feeds were protected towards developing delay in fine motor skills.

Thus, early identification of factors for DDs with comprehensive medical evaluation is the need for prompt initiation of intervention.

Limitations

As the study relied on caregivers/parents verbatim, their recall might have weakened the reliability of information related to the developmental history, pregnancy history, and breastfeeding history. Small sample size of the study also poses a limitation. Thus, to provide a clear picture, an extensive epidemiological study in rural area should be conducted.

Conclusion

Considering the fact that there are many factors that lead to DDs in young children, this study further adds to the potential risk factors individually affecting the various developmental domains in children. Number of children in family, father's education level, gestational age, medication taken by mother, accident or fall during pregnancy, prolonged labor, complications during pregnancy, delivery conducted by Dai, Nurse/ANM, meconium aspiration, birth injury, delayed child cry, neonatal illnesses, child never breastfed, colostrum not given, prelacteal feeds, and untimely initiation of complementary feeds were found to be the strong predictors for delay in different domains of developmental milestones.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are here being put forward for early timely intervention and referral. Since caregivers/parents play a central role in enabling early childhood development interventions, their awareness and knowledge regarding developmental milestones need to be increased for better recognition of delay in developmental milestones, right from the antenatal period, and thereafter each time the child meets any health-care worker.

In the current study, most of the children had delay in the cognitive domain; being a rural study, it is expected that children are not getting the right environment or opportunities to enhance their skills in this domain. Preschool education provided by AWCs has a lacuna in their implementation; the AWWs themselves does not have conceptual clarity about the preschool equipment's kits; moreover, due to lack of proper infrastructure, the services are not executed accordingly. Thus, infrastructure needs to be strengthened and caregivers/parents and Anganwadi workers should be made aware of interactive, incidental, and conceptual learning.

The present study also shows the educational status of the father to be strongly linked with the cognitive development of the child, and thus, educational programs involving father should be encouraged. A protocol should be formulated for identification of children who are at high risk (targeted approach) of suspected DDs so that they can be monitored easily, and early intervention can be tailored. Fortnight visits of super specialists such as pediatric subspecialists, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist, and physiotherapist at the CHCs, PHCs, and subcenters and at child's home or any other natural environment (community-based individual/collateral) visits should be made mandatory. Finally, counseling and training in psychosocial interventions should be given to families to enhance their capacity to care.

Consent

Written consent was taken from each parents/caregivers of the children in the study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate consent forms. In the form, the parents/caregivers of the children gave their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The parents/caregivers understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.David D, Toppo KJ, Saini K. Research article a study to assess the knowledge of mothers' regarding developmental milestones of infants. 2014 Jul;6(07):7524–7528. Available from: http://www.gmferd.com/journalcra.com/sites/default/files/5791_1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eldred K, Darrah J. Using cluster analysis to interpret the variability of gross motor scores of children with typical development. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1510–8. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tervo RC. Identifying patterns of developmental delays can help diagnose neurodevelopmental disorders. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45:509–17. doi: 10.1177/0009922806290566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter F, Wrester F. Early childhood development. J Child Dev. 2009;23:23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerstjens JM, de Winter AF, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, ten Vergert EMJ, Reijneveld SA, Bos AF. Developmental delay in moderately perterm-born children at school entry. J Pediatr. 2011;159:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch R. Institute: Results of the child and youth health survey. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:529–908. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wohlfeil A. Developmental delays in children starting school with the resultant performance deficits. Öffentl Gesundhwes. 1991;53:175–80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Developmental Disabilities Services and Facilities Construction Act of 1970. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 02]. pp. 91–517. Available from: http://www.mn.gov/mnddc/dd_act/documents/FEDREG/90-DDALEGLISLATIVEHISTORY.pdf .

- 9.Landgren M, Pettersson R, Kjellman B, Gillberg C. ADHD, DAMP and other neurodevelopmental/psychiatric disorders in 6-year-old children: Epidemiology and co-morbidity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1996;38:891–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tirosh E, Berger J, Cohen-Ophir M, Davidovitch M, Cohen A. Learning disabilities with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Parents' and teachers' perspectives. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:270–6. doi: 10.1177/088307389801300606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishop DV. Handedness, clumsiness and developmental language disorders. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:681–90. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ. Comparison of deficits in cognitive and motor skills among children with dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. 1994;44:147–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02648159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) Child Health Screening and Early Intervention Services under NRHM. Oper Guidelines. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee SB, Aneja S, Krishnamurthy V, Srinivasan R. Incorporating Developmental Screening and Surveillance of Young Children in Office Practice [Internet] Vol. 627. INDIAN PEDIATRICS; 2014. [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.indianpediatrics.net/aug2014/627.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cioni G, Inguaggiato E, Sgandurra G. Early intervention in neurodevelopmental disorders: Underlying neural mechanisms. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(Suppl 4):61–6. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell F, Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Pungello E, et al. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science. 2014;343:1478–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1248429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg SA, Zhang D, Robinson CC. Prevalence of developmental delays and participation in early intervention services for young children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1503–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal PK, Shi L, Daniel LM, Yang PH, Khoo PC, Quek BH, et al. Prospective evaluation of the ages and stages questionnaire 3rd edition in very-low-birthweight infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:484–9. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerstjens JM, Bos AF, ten Vergert EM, de Meer G, Butcher PR, Reijneveld SA, et al. Support for the global feasibility of the ages and stages questionnaire as developmental screener. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flamant C, Branger B, Nguyen The Tich S, de la Rochebrochard E, Savagner C, Berlie I, et al. Parent-completed developmental screening in premature children: A valid tool for follow-up programs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torabi F, Akbari SAA, Amiri S, Soleimani F, Majd HA. Correlation between high-risk pregnancy and developmental delay in children aged 4-60 months. Libyan J Med. 2012;7(1):0–6. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.18811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vora H, Shah P, Mansuri SH. A study on developmental delay among children less than 2 year attending well baby clinic – Prevalence and antecedents factors. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;462037:1084–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meenai Z, Longia S. A study on prevalence & antecedents of developmental delay among children less than 2 years attending well baby clinic. Peoples J Sci Res. 2009;2:462037. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali SS, Pa B, Dhaded SM, Goudar SS. Assessment of growth and global developmental delay: A study among young children in a rural community of India. International Multidisciplinary Research Journal. 2011;1(7):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Séguin L, Xu Q, Gauvin L, Zunzunegui MV, Potvin L, Frohlich KL, et al. Understanding the dimensions of socioeconomic status that influence toddlers' health: unique impact of lack of money for basic needs in Quebec's birth cohort. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 05];Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 59:42–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020438. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1763364/pdf/v059p00042.pdf . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binu A, Sunil R, Baburaj S, Mohandas MK. Socio demographic profile of speech and language delay up to six years of age in Indian children. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2014;3(1):98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devi UL, Professor A, Resident S. Assessment of speech and language delay using language evaluation scale Trivandrum (LEST 0-3) [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 27];Chettinad Health City Med J. 2015 4:70–4. Available from: http://www.chcmj.ac.in/journal/pdf/vol4_no2/Assessment. pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mondal N, Bhat BV, Plakkal N, Thulasingam M, Ajayan P, Poorna DR. Prevalence and risk factors of speech and language delay in children less than three years of age. J Compr Pediatr. 2016;7:e33173. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venketraman Kondekar S, Shree VS, Kondekar SV. Assessment of speech and language delay among 0-3 years old children attending well-baby clinics using Language Evaluation Scale Trivandrum. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 25];Indian J Child Health. 2016 3:220–4. Available from: https://www.atharvapub.net/index.php/IJCH/article/viewFile/551/337 . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidhu M, Malhi P, Jerath J. Early language development in Indian children: A population-based pilot study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:371–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.116937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dharmalingam A, Raghupathy NS, Belgin R, Kumar P. Cross sectional study on language assessment of speech delay in children 0 to 6 years. [Last accessed on 2018, Oct 6];IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015 14:2279–861. Available from: http://www.iosrjournals.org . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta A, Kalaivani M, Gupta SK, Rai SK, Nongkynrih B. The study on achievement of motor milestones and associated factors among children in rural North India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:378–82. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sajedi F, Vameghi R, Kraskian Mujembari A. Prevalence of undetected developmental delays in Iranian children. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:379–88. doi: 10.1111/cch.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bello AI, Quartey JN, Appiah LA. Screening for developmental delay among children attending a rural community welfare clinic in Ghana. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dabar D, Das R, Nagesh S, Yadav V, Mangal A. A community-based study on growth and development of under-five children in an urbanized village of South Delhi. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62:446–56. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmw026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soleimani F, Vameghi R, Biglarian A, Rahgozar M. Prevalence of motor developmental disorders in children in Alborz province, Iran in 2010. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e16711. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.16711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerstjens JM, de Winter AF, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, ten Vergert EM, Reijneveld SA, Bos AF, et al. Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children at school entry. J Pediatr. 2011;159:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharya T, Ray S, Das DK. Developmental delay among children below two years of age : A cross- sectional study in a community development block of Burdwan district, West Bengal. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2017;4:1762–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheelamma JK, Kumari KS. Developmental profile of children under two years in the coastal area of Kochi, Kerala. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 05];Int J Adv Res J. 2013 1:870–4. Available from: http://www.journalijar.com/uploads/2013-12-04_031544_778.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valla L, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hofoss D, Slinning K. Prevalence of suspected developmental delays in early infancy: Results from a regional population-based longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:215. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0528-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hediger ML, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Troendle JF. Birthweight and gestational age effects on motor and social development. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16:33–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handal AJ, Lozoff B, Breilh J, Harlow SD. Sociodemographic and nutritional correlates of neurobehavioral development: A study of young children in a rural region of Ecuador. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;21:292–300. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892007000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter J, Janson H. A validation study of the Norwegian version of the ages and stages questionnaires. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:748–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potijk MR, Kerstjens JM, Bos AF, Reijneveld SA, de Winter AF. Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children with low socioeconomic status: Risks multiply. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schady N. Parents' education, mothers' vocabulary, and cognitive development in early childhood: Longitudinal evidence from Ecuador. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2299–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comuk-Balci N, Bayoglu B, Tekindal A, Kerem-Gunel M, Anlar B. Screening preschool children for fine motor skills: Environmental influence. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28:1026–31. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alvik A, Grøholt B. Examination of the cut-off scores determined by the Ages and Stages Questionnaire in a population-based sample of 6 month-old Norwegian infants [Internet] 2011. [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/11/117 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Charan GS, Vagha J. Study of perinatal factors in children with developmental delay. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 2017;4:182–90. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguefack S, Kamga KK, Moifo B, Chiabi A, Mah E, Mbonda E. Causes of developmental delay in children of 5 to 72 months old at the child neurology unit of Yaounde Gynaeco-obstetric and paediatric hospital (Cameroon) [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 27];Open J Pediatr. 2013 3:279–85. Available from: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojped. 2013.33050 . [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sachdeva S, Amir A, Alam S, Khan Z, Khalique N, Ansari MA, et al. Global developmental delay and its determinants among urban infants and toddlers: A cross sectional study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:975–80. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tikaria A, Kabra M, Gupta N, Sapra S, Balakrishnan P, Gulati S, et al. Aetiology of global developmental delay in young children: Experience from a tertiary care centre in India. Natl Med J India. 2010;23:324–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Marroun H, Zeegers M, Steegers EA, van der Ende J, Schenk JJ, Hofman A, et al. Post-term birth and the risk of behavioural and emotional problems in early childhood. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:773–81. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olesen AW, Olsen J, Zhu JL. Developmental milestones in children born post-term in the Danish national birth cohort: A main research article. BJOG. 2015;122:1331–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beligere N, Rao R. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with meconium aspiration syndrome: Report of a study and literature review. J Perinatol. 2008;28(Suppl 3):S93–101. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiswell TE, Bent RC. Meconium staining and the meconium aspiration syndrome. Unresolved issues. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40:955–81. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38618-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vidyasagar D, Harris V, Pildes RS. Assisted ventilation in infants with meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatrics. 1975;56:208–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koul R, Al-Yahmedy M, Al-Futaisi A. Evaluation children with global developmental delay: A prospective study at Sultan Qaboos university hospital, Oman. Oman Med J. 2012;27:310–3. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomaidis L, Zantopoulos GZ, Fouzas S, Mantagou L, Bakoula C, Konstantopoulos A, et al. Predictors of severity and outcome of global developmental delay without definitive etiologic yield: A prospective observational study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Juneja M, Mohanty M, Jain R, Ramji S. Ages and stages questionnaire as a screening tool for developmental delay in Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:457–61. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Oosterlaan J. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:2235–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ballot DE, Chirwa TF, Cooper PA. Determinants of survival in very low birth weight neonates in a public sector hospital in Johannesburg. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chattopadhyay N, Mitra K. Neurodevelopmental outcome of high risk newborns discharged from special care baby units in a rural district in India. J Public Health Res. 2015;4:318. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2015.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, Vanilovich I, Platt RW, Matush L, et al. Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:578–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jedrychowski W, Perera F, Jankowski J, Butscher M, Mroz E, Flak E, et al. Effect of exclusive breastfeeding on the development of children's cognitive function in the Krakow prospective birth cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:151–8. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lundqvist-Persson C, Lau G, Nordin P, Strandvik B, Sabel KG. Early behaviour and development in breast-fed premature infants are influenced by omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acid status. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pérez-Escamilla R. Influence of Breastfeeding on Psychosocial Development. 2008. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 31]. Available from: http://www.childencyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/textes-experts/en/545/influence-of-breastfeeding-on-psychosocial-development.pdf .

- 67.Walfisch A, Sermer C, Cressman A, Koren G. Breast milk and cognitive development – The role of confounders: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003259. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernard JY, Armand M, Peyre H, Garcia C, Forhan A, De Agostini M, et al. Breastfeeding, polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in colostrum and child intelligence quotient at age 5-6 years. J Pediatr. 2017;183:43–50.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]