Abstract

Background

The σ54 factor controls unique promoters and interacts with a specialized activator (enhancer binding proteins [EBP]) for transcription initiation. Although σ54 is present in many Clostridiales species that have great importance in human health and biotechnological applications, the cellular processes controlled by σ54 remain unknown.

Results

For systematic analysis of the regulatory functions of σ54, we performed comparative genomic reconstruction of transcriptional regulons of σ54 in 57 species from the Clostridiales order. The EBP-binding DNA motifs and regulated genes were identified for 263 EBPs that constitute 39 distinct groups. The reconstructed σ54 regulons contain the genes involved in fermentation and amino acid catabolism. The predicted σ54 binding sites in the genomes of Clostridiales spp. were verified by in vitro binding assays. To our knowledge, this is the first report about direct regulation of the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis by σ54 and the respective EBPs. Considerable variations were demonstrated in the sizes and gene contents of reconstructed σ54 regulons between different Clostridiales species. It is proposed that σ54 controls butyrate and alcohols synthesis in solvent-producing species, regulates autotrophic metabolism in acetogenic species, and affects the toxin production in pathogenic species.

Conclusions

This study reveals previously unrecognized functions of σ54 and provides novel insights into the regulation of fermentation and amino acid metabolism in Clostridiales species, which could have potential applications in guiding the treatment and efficient utilization of these species.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-019-5918-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: σ54, Enhancer binding protein, Transcriptional regulation, Clostridium, Comparative genomics

Background

The sigma (σ) subunit is required for promoter recognition and initiation of transcription by the bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP). σ54 is unique in that it shares no detectable homology with any of the other known sigma factors (e.g., σ70) and binds to conserved − 12 and − 24 promoter elements [1]. The σ54-dependent transcription absolutely requires the presence of an activator that couples the energy generated from ATP hydrolysis to the isomerization of the RNA polymerase-σ54 closed complex [2]. These activators are usually called enhancer binding proteins (EBPs) and bind to upstream activator sequences (UAS) located upstream of the promoter. EBPs are modular proteins and generally consist of three domains [3, 4]. The regulatory domain has a role in signal perception and modulates the activity of the EBPs. The AAA+ (ATPase associated with cellular activities) domain is responsible for ATP hydrolysis and interaction with σ54. The DNA-binding domain enables recognition of specific UAS site. DNA looping is required for the activator to contact the closed complex and catalyze formation of the open promoter complex [5].

The σ54 regulons have been extensively studied in several model organisms. In Escherichia coli, σ54 was identified as a sigma factor for transcription of genes involved in the assimilation of ammonia and glutamate under conditions of nitrogen limitation [6]. This σ54-dependent transcription requires the activator NtrC that is phosphorylated by the sensor kinase NtrB in response to the nitrogen status of the cell [7]. The involvement of σ54 in flagellar biosynthesis, formate metabolism, and phage shock response was also found in E. coli. It was considered that the physiological themes of the vast majority of σ54-dependent genes in E. coli may be related to nitrogen assimilation [8]. In many diazotrophic Proteobacteria such as Azotobacter vinelandii, transcription of the genes required for nitrogen fixation are dependent on σ54 [9]. In addition, other physiological functions such as catabolism of toluene and xylenes in Pseudomonas putida as well as utilization of levan and acetoin in Bacillus subtilis are also controlled by σ54 [10–12].

Organisms of the order Clostridiales are Gram-positive obligate anaerobes important in human health and physiology, the carbon cycle, and biotechnological applications [13, 14]. For example, Clostridium beijerinckii, Clostridium acetobutylicum, Clostridium saccharobutylicum, and Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum can ferment carbohydrates and produce solvents [15]. The acetogenic Clostridium ljungdahlii, Clostridium carboxidivorans, Clostridium autoethanogenum, Acetobacterium woodii are able to fix CO2 or CO [16]. Several Clostridiales species are significant human pathogens, including Clostridioides difficile that is an important cause of diarrhea, Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium tetani, and Clostridium perfringens that are the etiological agents of botulism, tetanus, and gas gangrene, respectively [17]. On the other hand, some Clostridiales species are believed to have positive effect on human health, including Clostridium butyricum that is widely used as a probiotic and Clostridium novyi that has potential therapeutic uses in cancers [18, 19]. Recently, several Clostridiales species have been isolated from animal gut, including Romboutsia ilealis and Romboutsia sp. FRIFI, which are natural resident and key players in the small intestinal of animals [20].

Our previous study has identified some σ54-dependent genes in several Clostridium species, which are activated by the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system regulation domain (PRD)-containing EBPs and involved in utilization of β-glucosides, fructose/levan, pentitols, and glucosamine/fructosamine [21]. However, the regulatory functions of the majority of the EBPs in Clostridiales species remain unknown. Our knowledge about the cellular processes controlled by σ54 in Clostridiales is limited, because the σ54 regulons have not been systematically analyzed in these organisms.

In this study, we used a comparative genomic approach to reconstruct σ54-dependent transcriptional regulons in 57 species from the Clostridiales order. We identified putative EBPs and their regulatory modules. The candidate targets of σ54 and 263 EBPs, which constitute 39 distinct EBP groups, were identified based on the recognition of the EBP-binding DNA motifs, candidate UAS sites, and conserved σ54 promoter elements. Some of the predicted σ54-dependent promoters upstream of putative target genes in the genomes of Clostridium spp. were validated by in vitro binding assays. Considerable variations were found in the sizes and gene contents of reconstructed σ54 regulons between different species. Based on the gene contents of the reconstructed regulons, novel functions of σ54 and the respective EBPs were identified, including direct regulation of the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis.

Results

Repertoire of σ54 and EBPs in Clostridiales

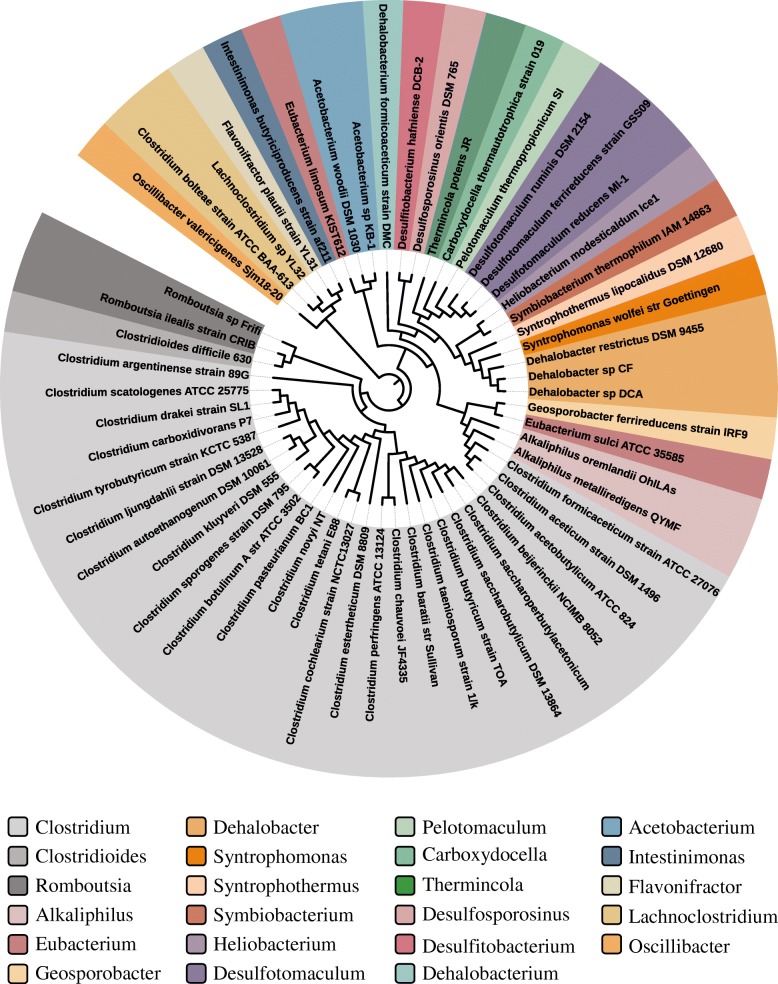

For identification of σ54 (SigL) in Clostridiales species, orthologs of SigL from B. subtilis was searched in 124 completely sequenced genomes. The SigL orthologs were found in 57 genomes from 23 genera including Clostridium, Clostridioides, Eubacterium, Acetobacterium, and Dehalobacter (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Table S1). Each of these genomes has a single copy of sigL. Among the 23 genera, Clostridium genus has the largest number of SigL orthologs. The SigL was identified in 26 genomes of Clostridium genus, including C. beijerinckii, C. acetobutylicum, C. ljungdahlii, C. botulinum, and C. tetani. However, some species in Clostridium genus such as cellulolytic Clostridium cellulovorans lack a SigL ortholog. In each of the other genera, SigL was found in only one to three species. Thus, σ54 is widely present among Clostridiales. However, its presence seemingly had no obvious correlation with the phylogeny of Clostridiales species.

Fig. 1.

The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of σ54 (SigL) in 57 species from 23 genera of Clostridiales

For identification of EBPs that are σ54-dependent transcriptional activators, the experimentally characterized EBPs proteins including NtrC from E. coli, AcoR and LevR from B. subtilis were used for homologous search in the Clostridiales species that have the σ54-encoding gene. A total of 490 EBPs were identified in 57 Clostridiales species. The presence of the peptide motif ‘GAFTGA’ was checked in the identified EBPs, which is necessary for the interaction with σ54 [22]. An exact GAFTGA sequence was observed in 355 out of 490 EBPs (Additional file 1: Table S2). The other 100 EBPs possess some variants of the motif (e.g., GSFTGA, GAYTGA, GAFSGA), which still allow the EBP to activate σ54-dependent transcription [3]. Our regulon reconstruction results (see below) also suggested that these variants do not prevent the respective EBP from activating σ54 promoters.

Each of the analyzed Clostridiales species possesses one to thirty-five EBPs (Additional file 1: Table S1). The number of EBPs is highly variable between different species. A significant positive correction was observed between the EBPs number and the genome size with the spearman correlation test (p < 0.0001) (Additional file 1: Table S1), similar to the results of the previous report [6].

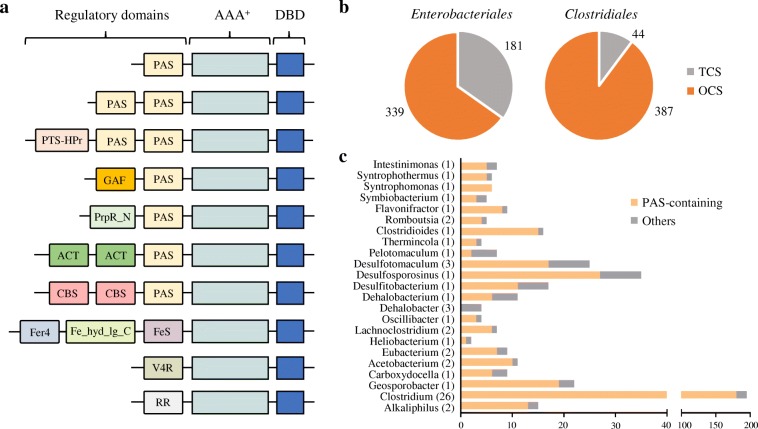

The majority (431 out of 490; 77%) of the identified EBPs in Clostridiales consist of a central AAA+ domain, an N-terminal regulatory domain, and a DNA-binding domain (DBD) at the C-terminus (Additional file 1: Table S2). Forty-eight EBPs possess the PRD domain at the C-terminus [21]. The remaining 11 EBPs lack the N-terminal regulatory domain, which is similar to PspF from E. coli [23].

The N-terminal regulatory domain, which responds to environmental signals and modulates EBP activity [24], is not well conserved between the identified EBPs in Clostridiales species (Fig. 2a). A variety of domains were found in the regulatory region of the 431 EBPs, including PAS domains (Pfam clan accession no. CL0183), GAF domains (CL0161), PTS-HPr domains (PF00381), PrpR_N domains (PF06506), ACT domains (PF01842), CBS domains (PF00571), Fer4 domains (PF00037), Fe_hyd_lg_C domains (PF02906), FeS domains (PF04060), V4R domains (PF02830), and response regulator (RR) domains (Fig. 2a). Most of these domains lack transmembrane regions, suggesting that the EBPs in Clostridiales mainly sense intracellular signals. Interestingly, only 44 EBPs (~ 10%) have the RR domains that are part of two-component systems (TCSs) and phosphorylated by specific sensor kinases (Fig. 2b). The other 387 EBPs are one-component regulatory systems (OCSs) containing a regulatory domain that directly binds small effector molecules. This is different from the situation in Enterobacteriales, in which a larger fraction of EBPs (~ 35%) has the RR domains (Fig. 2b). This result indicates that the EBPs in Clostridiales respond to environmental signals mainly through ligand binding rather than phosphorylation of the N-terminal regulatory domain.

Fig. 2.

Domain organization of EBPs in Clostridiales. a The domain architecture of EBPs. PAS, Per-Arnt-Sim domain; GAF, cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases and FhlA; PTS-HPr, PTS system histidine phosphocarrier protein HPr-like; PrpR_N, N-terminal domain of Propionate catabolism activator; ACT, aspartokinase-chorismate mutase-TyrA; CBS, cystathinoine β-synthase domain; Fer4, 4Fe-4S binding domain; Fe_hyd_lg_C, iron only hydrogenase large subunit, C-terminal domain; FeS, Fe-S cluster; V4R, vinyl 4 reductase domain; RR, response regulator domain. b Distribution of TCS and OCS-type EBPs in Enterobacteriales and Clostridiales. c Distribution of PAS-containing EBPs in 23 genera of Clostridiales

Almost all the OCS-type EBPs (357 out of 387) contain the PAS domains, which can bind various cofactors and ligands and are often found in signaling proteins [25, 26]. These PAS domain-containing EBPs are widely distributed in nearly all the analyzed Clostridiales species (Fig. 2c). The PAS domains are present as single domain, in two copies, or adjacent to other domains on the same EBP (Fig. 2a). This suggests that the PAS domains play an important role in signal sensing or transduction, thereby modulating the activity of a large number of EBPs in Clostridiales species.

Reconstruction of regulons of σ54-dependent transcriptional activators in Clostridiales

To reconstruct transcriptional regulons for the repertoire of the EBPs in Clostridiales, we used the integrative comparative genomics approach that combines identification of candidate DNA binding sites of EBPs and σ54 with cross-genomic comparison of regulons (see Methods for details). The DNA-binding domain of 335 EBPs in Clostridiales contains a Fis-type helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (Pfam accession no. PF02954), which allows recognition of specific EBP binding sites (UAS sites). We identified the conserved UAS motifs and reconstructed the regulons for 263 EBPs that constitute 39 groups with two or more orthologs. The remaining EBPs lack orthologs in the sequenced Clostridales genomes, thus comparative genomics approach cannot be applied reliably. Among the 39 orthologous groups of EBPs, four groups are PRD-containing EBPs, for which the UAS motifs have been identified previously [21]. We named the individual EBP groups based on the functional content analysis of the reconstructed regulons as described below.

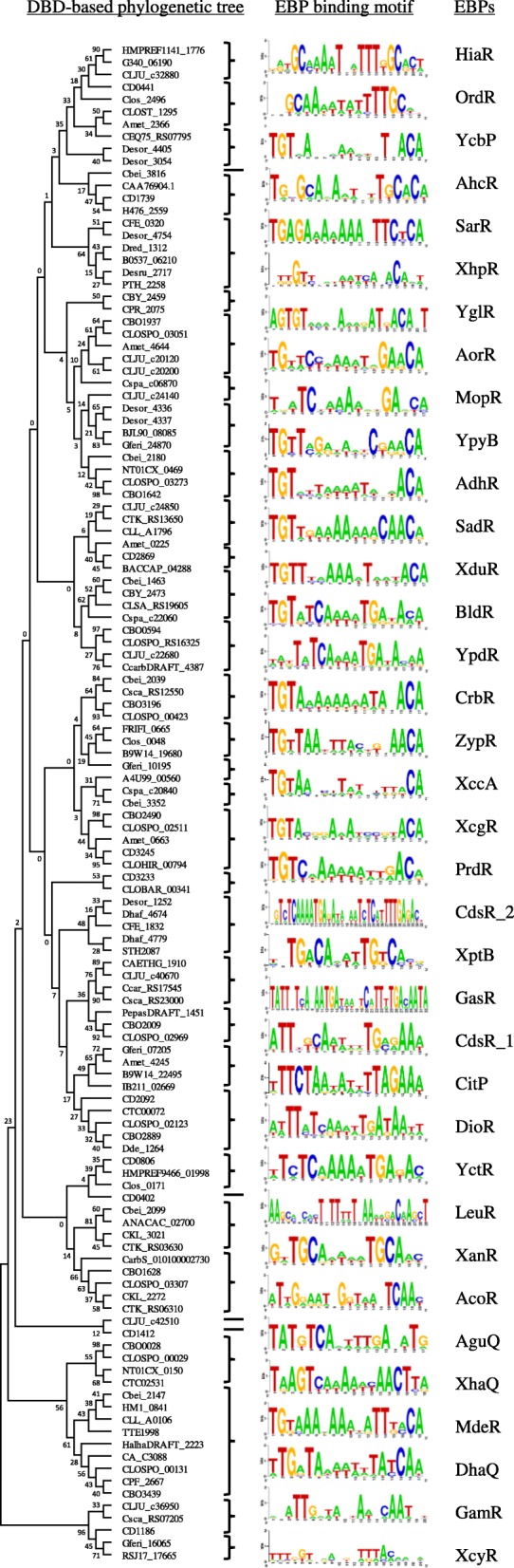

The identified UAS motif for each orthologous group of EBPs is shown in Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S3. The motifs for fifteen groups including YcbP, AhcR, XhpR, AorR, YpyB, AdhR, SadR, XduR, BldR, CrbR, ZypR, XccA, XcgR, PrdR, MdeR, consist of two inverted repeats TGT and ACA separated by 10–12-bp spacer, which is similar to the UAS motifs for the well-characterized EBPs such as FhlA in E. coli [27] and NifA in Klebsiella pneumoniae [28]. Comparison of all the identified UAS motifs using TOMTOM [29] found similarity in the motifs for the other 6 groups (i.e., SarR, YglR, XptB,AguQ, XhaQ, DhaR). However, distinct DNA motifs were found for the remaining 15 groups (i.e., HiaR, OrdR, MopR, YpdR, CdsR1/2, GasR, CitP, DioR, YctR, LeuR, XanR, AcoR, GamR, XcyR). Similarity of the UAS motifs is consistent with the similarity of the DNA-binding domains of EBPs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of DNA-binding domains of EBPs and identified EBP-binding DNA motifs in Clostridiales

All the candidate UAS sites for 263 EBPs were detected using these obtained DNA motifs. Moreover, we used the σ54 promoter sequence motif with the consensus TTGGCATNNNNNTTGCT to search for candidate σ54 binding sites in 57 Clostridiales genomes [30]. The details about the target operons of individual EBPs, and their upstream UAS sites and σ54-binding sites are listed in Additional file 1: Table S3.

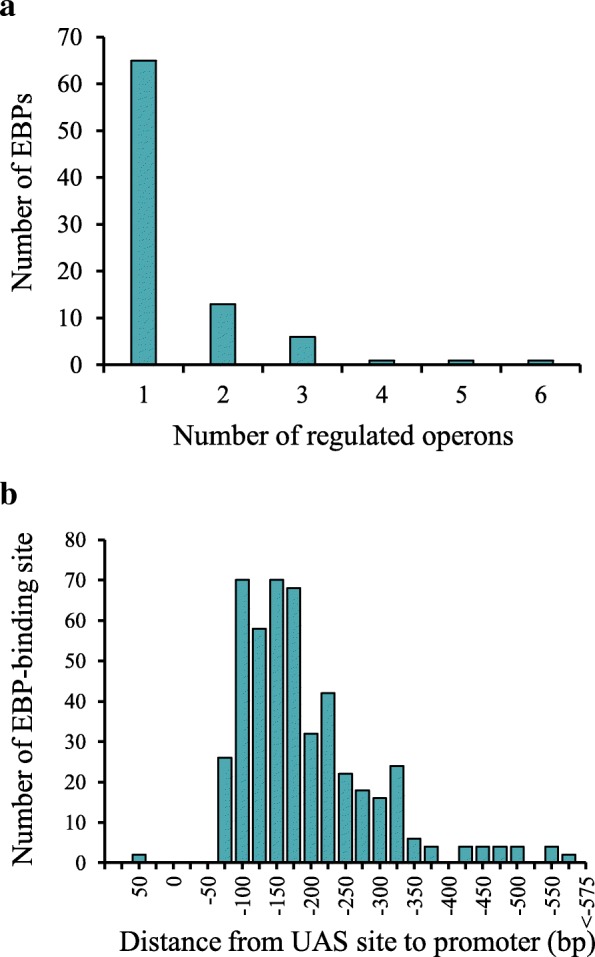

The majority of the EBPs (170 out of 263; 65%) was found to control only one target operon (Fig. 4a). The rest 93 EBPs have larger regulons with two to six operons. Most of the predicted target operons are co-localized with the respective EBP-encoding genes on the chromosome. This is coincident with previous findings that the EBP-encoding genes are usually close or adjacent to their target genes [4, 31]. However, 38 EBPs belonging to 12 orthologous groups were found not positionally clustered with the regulated genes (Additional file 1: Table S3). For 32 orthologous groups comprising of 198 EBPs, the target operons are preceded by multiple UAS sites. The σ54 binding sites were identified within the promoter regions of all the candidate target operons of EBPs. Most of the detected UAS sites are situated in the upstream of the candidate σ54 promoter at a distance of 100–250 bp (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of a EBPs regulons sizes and b distances between UAS site and σ54 promoter

Functional content of reconstructed σ54 regulons in Clostridiales

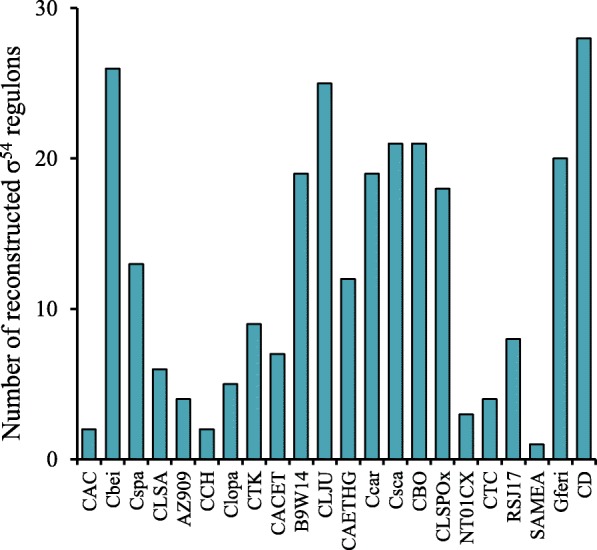

We tentatively predicted possible biological functions of σ54 and EBPs by assessing the functional context of the target operons. We were able to predict the functions for 31 out of 39 orthologous EBP groups (Table 1). These EBPs were named based on the functional content analysis of the target genes. For the remaining eight groups, the functions of the target genes are unknown. We observed that the sizes of reconstructed σ54 regulons vary significantly in different Clostridiales species (Fig. 5). For instance, the σ54 regulon contains 26 operons in C. beijerinckii, whereas in C. acetobutylicum only two operons are σ54-controlled. The total number of regulons per genome varies from one to twenty-eight. Not a single operon is potentially regulated by σ54 in all the analyzed species.

Table 1.

Reconstructed EBP regulons of Clostridiales

| EBP | Target operon | Function | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| AcoR | acoABCL | Acetoin catabolism | Clostridium |

| AdhR | adhA | Alcohol synthesis | Clostridium |

| AguQ | aguDA, aguBC, aguQT | Agmatine metabolism | Clostridium |

| AhcR | atoE-hbd-cotX | Butyrate/Butanol synthesis | Clostridium |

| AorR | aor-moaD | Alcohol synthesis | Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| AtlR |

atlEFG, atlD-tkt-rpi-araD-manB |

Pentitol catabolism | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Geosporobacter, Lachnoclostridium |

| BldR | butA | 2,3-Butanediol synthesis | Clostridium |

| CelR | celCA-bglB-celB, celFB | Cellobiose catabolism | Alkaliphilus, Clostridium |

| CitP | citA | Transporter | Alkaliphilus, Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| CrbR | crt-hbd-thl-maoC-bcd-etfAB, cotX-gntT | Butyrate/Butanol synthesis | Clostridium |

| DhaQ | dhaKLM, ptsI | Dihydroxyacetone metabolism | Acetobacterium, Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| DioR |

dpaL-pyrC-argE, tdcF, yqeB, pbuX, ygeW-ygfK-ssnA-ygeY, dioR, yqeC-ygfJ-yqeB-xdhC-hyp-fepDCB |

Unknown | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Desulfotomaculum |

| GamR | puuDT | Amino acid metabolism | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Romboutsia |

| GasR | puuXP | Amino acid metabolism | Clostridium |

| GfrR | gfrABCDEF | Glucosamine/fructosamine catabolism | Clostridioides, Clostridium |

| HiaR | hiaL-hyp-hutH | Histidine catabolism | Clostridium |

| CdsR | cdsB | Cysteine catabolism | Clostridium, Clostridioides |

| LeuR | hadAIBC-acdB-etfBA | Leucine catabolism | Clostridioides |

| LevR | levDEFG-sacC | Levan catabolism | Clostridium |

| MdeR | mdeA-metT | Methionine catabolism | Clostridium |

| MopR | mopR, mop, hyp-moeA | Unknown | Clostridium |

| OrdR | ord-ortBA-oraSEF-orr-nhaC | Ornithine catabolism | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Geosporobacter, Romboutsia |

| PrdR | prdABDEF, prdC | Proline catabolism | Alkaliphilus, Clostridioides, Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| SadR | sadh | Alcohol synthesis | Clostridium |

| SarR | grdGF | Sarcosine metabolism | Clostridioides |

| XanR |

abfD-nifU-hyp-ach-golB, acp-caiC-luxEC |

Butyrate/Butanol synthesis | Clostridium |

| XcaA | thl | Unknown | Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| YcbP | phyL-uroD-eamA | Unknown | Dehalobacterium, Desulfosporosinus |

| XcgR | cotY-gntT-bcd-etfAB | Butyrate/Butanol synthesis | Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| XcyR | malY-pepT-hyp | Peptide degradation | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Flavonifractor, Geosporobacter, Lachnoclostridium |

| XduR | kdgT-uxaA | Pectin degradation | Alkaliphilus, Clostridioides, Clostridium, Geosporobacter |

| XhaQ | rhaT | Transporter | Clostridioides |

| XhpR | hyp-memP | Unknown | Desulfosporosinus, Carboxydocella, Desulfotomaculum |

| XptB | sulT, hyp | Unknown | Dehalobacterium, Desulfitobacterium, Desulfosporosinus, Carboxydocella |

| YctR | crt-gntT-caiB-bcd-etfAB | Butyrate/Butanol synthesis | Clostridioides |

| YglR | hyp-gltD | Unknown | Clostridium |

| YpdR |

metM-memP-pepABC, fmdE-metM-hemABC |

Peptide degradation | Clostridium |

| YpyB | pdc-tdh-hyp | Unknown | Clostridium, Desulfosporosinus, Geosporobacter |

| ZypR | tyrB-iorAB-butK | Amino acid metabolism | Clostridioides, Clostridium, Romboutsia |

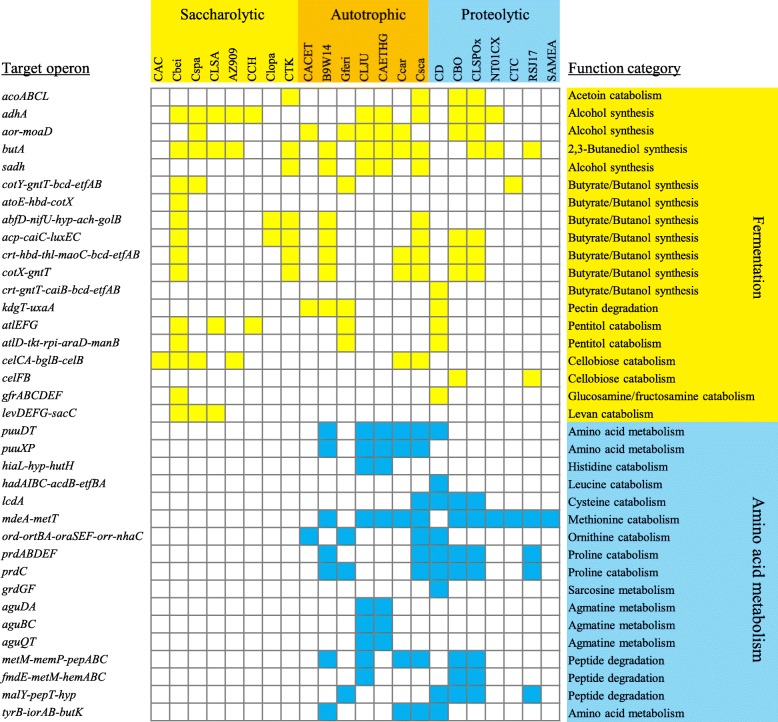

Fig. 5.

The sizes of reconstructed σ54 regulons in representative species of Clostridiales. CAC, C. acetobutylicum; Cbei, C. beijerinckii; Cspa, C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum; CLSA, C. saccharobutylicum; ZA909, C. butyricum; CCH, Clostridium chauvoei; Clopa, Clostridium pasteurianum; CTK, Clostridium tyrobutyricum; CACET, C. aceticum; B9W14, Clostridium drakei; CLJU, C. ljungdahlii; CAETHG, C. autoethanogenum; Ccar, C. carboxidivorans; Csca, C. scatologenes; CBO, C. botulinum; CLSPOx, C. sporogenes; NT01CX, C. novyi; CTC, C. tetani; RSJ17, C. argentinense; SAMEA, Clostridium cochlearium; Gferi, G. ferrireducens; CD, C. difficile

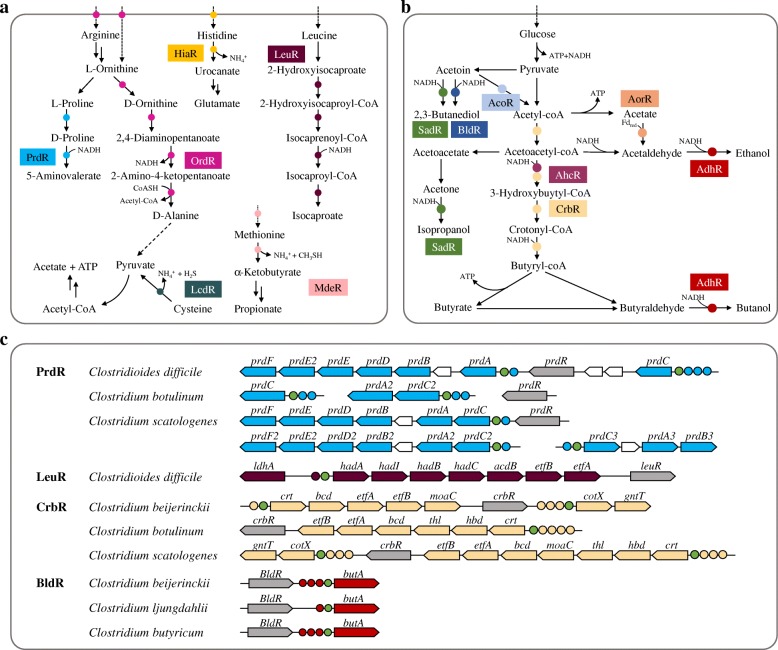

The reconstructed σ54 regulons control the metabolism in all of the analyzed Clostridiales species. The acoABCL operon involved in acetoin catabolism, which is σ54-dependent in B. subtilis [12], is present in the reconstructed clostridial σ54 regulons. The genes involved in transport of arginine/ornithine and histidine (i.e., nhaC and hiaL) are predicted to be σ54-dependent. The same function has been reported for the σ54 in E. coli [8], although the target genes are not orthologous. More importantly, we observed some members of the σ54 regulons in Clostridiales, which have not been described in any other bacteria. These operons are involved in fermentation and amino acid catabolism (Fig. 6), particularly in butyrate and alcohols synthesis and the Stickland reactions, as described in detail below.

Fig. 6.

Metabolic context of the reconstructed σ54 regulons in Clostridiales species. EBPs and regulated genes are involved in a amino acid catabolism and b fermentation. Individual EBPs and corresponding target genes are shown by matching background colors. c Functional and genomic context of representative EBPs regulons. EBP-encoding genes are shown by gray arrows, and target genes (shown by arrows) from the same metabolic pathway are shown with the same color. EBP binding sites are indicated by circle with matching colors, and σ54 binding sites are marked by green circle

Regulation of the Stickland reactions

In C. difficile and some other related species, the reconstructed σ54 regulons contain the genes involved in amino acid metabolism, especially the Stickland reactions (Fig. 6a). The Stickland reactions couple the oxidation and reduction of amino acids to their corresponding organic acids, which serves as a primary source of energy generation in Clostridium species [32]. This process strongly influences the production of toxins in pathogenic clostridia [33, 34].

Proline is one of the most efficient electron acceptors in the Stickland reactions [35]. The prdA, prdB, prdC, prdD, prdE, and prdF genes, which are involved in reduction of proline to 5-aminovalerate, were predicted to be σ54-dependent in nine Clostridiales species (Table 1). The prdABCDEF operon is preceded by putative σ54 promoter and multiple UAS sites of PrdR in the genome of C. difficile (Fig. 6c). Consistently, a previous study has shown that PrdR activates the expression of prd operon and negatively affects the expression of toxin gene in C. difficile [36]. We predicted that the genes involved in proline reduction, which are either clustered or stand-alone on the genome, are regulated by σ54 and PrdR in eight other species including C. botulinum, Clostridium scatologenes, Clostridium sporogenes, Clostridium formicaceticum, Alkaliphilus metalliredigenes, Clostridium argentinense, Geosporobacter ferrireducens, Alkaliphilus oremlandii (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Leucine can be used as both an electron donor and an acceptor in the Stickland reactions [37]. The hadAIBC-acdB-etfBA operon, which is involved in reduction of l-leucine to isocaproate, is preceded by a putative σ54 promoter and a candidate UAS site of LeuR in the genome of C. difficile (Fig. 6a, c). This suggests that reduction of leucine may be controlled by σ54 and LeuR in C. difficile. In addition, the ord-ortBA-oraSEF-orr-nhaC, which is involved in oxidation of ornithine to acetate, alanine, and ammonia, is predicted to be regulated by σ54 and OrdR in five species including C. difficile, Romboutsia sp. Frifi, G. ferrireducens, Clostridium aceticum, and C. scatologenes (Fig. 6a).

Utilization of cysteine and methionine was predicted to be controlled by σ54 in several pathogenic Clostridiales species (Fig. 6a). Availability of cysteine and methionine strongly affects production of toxins in these species [38, 39]. Recent studies have shown that σ54 and CdsR mediate the cysteine-dependent repression of toxin production in C. difficile [40, 41]. We identified a putative σ54 promoter and UAS site of CsdR upstream of cdsB gene involved in cysteine catabolism in C. difficile, C. botulinum, C. sporogenes, and C. scatologenes (Fig. 6a; Table 1). Moreover, the mdeA-metT operon, which is involved in transport and catabolism of methionine, is predicted to be regulated by σ54 and MdeR in C. botulinum, C. tetani, and 9 other Clostridiales species (Fig. 6a; Table 1).

Regulation of butyrate and alcohols synthesis

The reconstructed σ54 regulons contain the genes associated with butyrate and alcohols synthesis in Clostridiales species. The crt-hbd-thl-maoC-bcd-etfAB operon, which is able to convert acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) to butyryl-CoA, is preceded by a putative σ54 promoter and multiple UAS sites of CrbR in the genomes of C. beijerinckii, C. carboxidivorans, C. botulinum, and five other species (Fig. 6c; Additional file 1: Table S3). We predicted that the expression of this operon likely depends on the co-regulation of the CrbR and σ54 in these Clostridiales species, however the signal molecular remains unknown [42]. Candidate σ54 promoter was also identified in the upstream region of adhA and adhA2 genes encoding alcohol dehydrogenases, butA encoding 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase, and sadh encoding a secondary alcohol dehydrogenase [42–44] (Table 1). These genes constitute the most conserved part of the σ54 regulons in Clostridiales species. The corresponding EBPs are AdhR, BldR, and SadR, respectively (Fig. 6b). The aor gene encoding aldehyde oxidoreductase, which catalyzes the reduction of acetate to acetaldehyde, was predicted to be regulated by σ54 and AorR in C. ljungdahlii, C. carboxidivorans, C. autoethanogenum, and six other species. This gene has been shown to play an important role in ethanol production from syngas in C. autoethanogenum [45].

Comparison of σ54 regulons between different Clostridiales species

Clostridia are often differentiated by performing a saccharolytic or a proteolytic metabolism, although some proteolytic species can also grow on sugars [46]. Moreover, some saccharolytic species are able to perform autotrophic metabolism by using CO2/H2 gas mixture or CO as substrate [47]. We compared the reconstructed σ54 regulons between different Clostridiales species. In saccharolytic species such as C. beijerinckii, C. butyricum, and C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum, the σ54 regulons control sugar catabolism and fermentation, particularly butyrate and alcohols synthesis (Fig. 7). In proteolytic species such as C. difficile, C. botulinum, and C. sporogenes, the σ54 regulons contain not only the genes involved in amino acid catabolism (particularly in the Stickland reactions) but also the genes for sugar catabolism and fermentation (Fig. 7). Thus, the σ54 is likely closely linked to the central metabolism in different Clostridiales species. The size of the σ54 regulons is relatively large in the acetogenic species that are capable of autotrophic metabolism, including C. ljungdahlii, C. carboxidivorans, and C. autoethanogenum. Interestingly, for these species, the σ54 regulons control not only sugar catabolism and fermentation but also amino acid metabolism (Fig. 7). Previous studies have shown that the amino acid metabolism may provide reducing power and energy for autotrophic growth of C. autoethanogenum [48].

Fig. 7.

Distribution of predicted target operons of σ54 in Clostridiales species. The abbreviations of Clostridiales species are described in Fig. 5. The putative σ54-dependent genes involved in fermentation or amino acid metabolism are marked by yellow or blue square respectively

Experimental validation of σ54 binding to predicted DNA targets

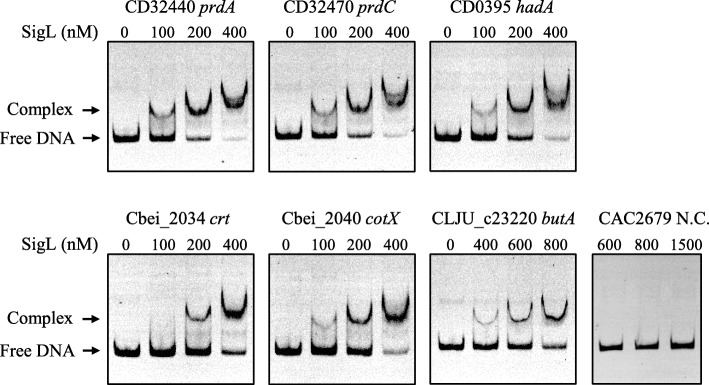

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed with the recombinant SigL (σ54) protein from C. beijerinckii to validate the predicted clostridial σ54 regulons. The SigL (σ54) protein is well conserved in the analyzed clostridia. We tested six DNA fragments from the upstream region of C. difficile prdC, prdABDE-prdE2-prdF, hadAIBC-acdB-etfBA; C. beijerinckii crt-bcd-etfAB-moaC, cotX-gntT; and C. ljungdahlii butA. These DNA fragments contain the predicted σ54 promoter elements. Upon the incubation of SigL protein with each promoter fragment, a shifted band was observed, and its intensity was σ54 concentration-dependent increased (Fig. 8). In contrast, the DNA fragment that lacks putative σ54 promoter elements was not shifted even at 1500 nM SigL protein (Fig. 8). These results confirm that SigL (σ54) binds specifically to the promoter regions of the predicted σ54 regulon members involved in the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis in Clostridiales species.

Fig. 8.

Experimental validation of the σ54 regulons in Clostridiales species. The EMSAs were performed with the purified SigL (σ54) protein from C. beijerinckii and DNA fragments containing the candidate −24 and − 12 regions upstream of predicted target genes in Clostridiales species. As a negative control (N.C.), the promoter region of CAC2679 gene in C. acetobutylicum was used, which lacks putative −12 and − 24 elements

Discussion

In this study, we performed comparative genomic reconstruction of transcriptional regulons of σ54 and 263 EBPs in 57 species from the Clostridiales order. These EBPs constitute 39 distinct groups. The sizes and gene contents of reconstructed σ54 regulons varied significantly among Clostridiales species. Based on the gene contents of the reconstructed regulons, the σ54 was predicted to control the central metabolism in diverse Clostridiales species. The predicted σ54 binding sites in the genomes of Clostridiales spp. were experimentally validated.

The reconstructed σ54 regulons contain the genes involved in fermentation and amino acid catabolism, particularly in the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about direct regulation of the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis by σ54 and the respective EBPs. Thus, the σ54 was predicted to control the ethanol and butanol production in solvent-producing clostridia including C. beijerinckii, C. saccharobutylicum, and C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum. In pathogenic clostridia including C. difficile, C. tetani, and C. botulinum, the σ54 was proposed to regulate the amino acid catabolism, especially the Stickland reaction, which strongly influences the production of toxins [33, 34]. Thus, the σ54 is probably strongly linked to the virulence of these pathogenic species. For the acetogenic species including C. ljungdahlii, C. carboxidivorans, and C. autoethanogenum that can fix CO2 or CO [47], the σ54 may play an important role in regulation of both heterotrophic and autotrophic metabolism. Although the recent two studies in C. beijerinckii have obtained some similar results about the σ54 function [49, 50], our systematic analysis of the regulatory network of σ54 yielded more complete and comprehensive regulons of σ54 and EBPs, covering all completely sequenced Clostridiales genomes.

The majority of the EBPs in Clostridiales are OCSs possessing a regulatory domain that directly recognize signal molecules and modulates the activity of the EBPs. A variety of domains were present in the regulatory region of the EBPs in Clostridiales. The most frequently found domain is the PAS domain, which can sense oxygen, light, redox potential, and energy status through binding various cofactors and ligands [25, 26]. The PAS domain is usually present in two copies or adjacent to other domains such as the GAF domain that can also bind diverse small-molecule metabolites [51, 52]. These regulatory domains could allow the EBPs to sense various signals of intracellular environment such as redox and energy status. Even one EBP may respond to multiple input signals. Thus, the σ54-dependent transcription may enable a rapid regulation of the central metabolism in response to changes in various environmental conditions.

Conclusions

In this study, we comprehensively characterized the σ54-dependent regulons in 57 Clostridiales species. In the analyzed genomes, we identified σ54 associated activators and their DNA-binding sites, as well as σ54-recognised promoters, and σ54-controlled genes and operons. In particular, we inferred σ54-dependent genes that are unknown before, including those involved in the Stickland reactions and butyrate and alcohols synthesis. Our results showed that the gene contexts and sizes of σ54-dependent regulons among Clostridiales species reveal significant difference. It is proposed that the σ54 controls butyrate and alcohols synthesis in solvent-producing species, regulates autotrophic metabolism in acetogenic species, and affects the toxin production in pathogenic species.

Methods

Identification of σ54 and enhancer binding proteins (EBPs)

Genomes analyzed in this study were download from GenBank [53], and were listed in the Additional file 1: Table S1. σ54 (SigL) orthologs were identified by similarity search using SigL from Bacillus subtilis. EBPs were identified based on homology to NtrC from E. coli and AcoR from B. subtilis using BLAST with an E-value threshold 1.0E-5. The presence of the characteristic amino acid motif GAFTGA was checked, which is required for the interaction between EBP and σ54 [54]. The MAFFT program [55] was used for protein sequence alignments. Conserved functional domains were identified using the HHpred tool [56] and Pfam [57]. Transmembrane regions were identified using the TMHMM server [58] and TMMOD [59]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum-likelihood method implemented in MEGA [60], with calculation of bootstraps from 1000 replicates. The MicrobesOnline database [61] and GenomeExplorer software [62] were used for cross-genomic comparison of genomic contexts for EBPs. Spearman correlation test was applied to assess the association of the EBPs number with the genome size.

Identification of σ54 promoters

For identification of σ54 binding sequences with conserved elements located at − 12 and − 24 positions, the 85 known promoters [30] were utilized to formulate the σ54 promoter sequence motif using the SignalX [62]. The motif was used to scan the genomes by the RegPredict [63] and GenomeExplorer [62] tools. The score threshold was defined as the lowest score observed in the training set.

Reconstruction of regulons of EBPs

Transcriptional regulons of EBPs were reconstructed using an established comparative genomics method based on identification of candidate regulator-binding sites in closely related prokaryotic genomes [64]. For identification of the conserved UAS motif for EBPs, we constructed the training sets of potentially regulated operons that are co-localized with σ54 promoters and EBP-encoding genes on the chromosome. For each group of EBP orthologs, a separate training gene set was used. The upstream noncoding sequences of potentially regulated operons were extracted, and an iterative motif detection algorithm implemented in the RegPredict was used to identify the UAS motif. A positional weight matrix was constructed for the identified motif and used to search the upstream regions of coding genes (from − 400 to + 50 bp with respect to the translation start) for candidate UAS sites in the genomes using the RegPredict [63] and GenomeExplorer [62] tools. Scores of candidate UAS sites were calculated as the sum of positional nucleotide weights. The score threshold was defined as the lowest score observed in the training set. Genes with candidate upstream UAS sites that are high scored and/or conserved in two or more genomes were included in the regulon of the respective EBP. The UAS motifs were visualized as sequence logos using WebLogo [65].

Functional annotations of the reconstructed regulon members were based on the literature and MicrobesOnline [61]. Known functional assignment for a particular gene was expanded to its orthologous genes. For prediction of gene function, both the comparative genomics and context-based methods were used [64] .

Protein overexpression and purification

The sigL gene was PCR amplified from C. beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 genomic DNA using the primers shown in Additional file 1: Table S4. The PCR fragment was ligated into the expression vector pET28a. The resulting plasmid pET28a-sigL was used to produce SigL protein with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag. E. coli BL21Rosetta(DE3) (Novagen) was transformed with expression plasmid. Protein overexpression and purification were performed as described previously [21].

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The 200-bp DNA fragments in the promoter region of crt or cotX gene from C. beijerinckii genome and of butA gene from C. ljungdahlii genome were PCR amplified using the primers shown in Additional file 1: Table S4. The DNA fragments containing the putative promoter elements upstream of prdA, prdC and hadA genes from C. difficile were chemically synthesized by Genscript. Both forward and reverse primers were Cy5 fluorescence labeled at the 5′-end (Sangong, China). Mobility shift assays were performed as described previously [21].

Additional file

Table S1. List of Clostridiales species containing σ54 (SigL) and EBPs. Table S2. Identified EBPs in Clostridiales. Table S3. Reconstructed regulons of EBPs in Clostridiales. Table S4. Primers used in this study. (PDF 1577 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AAA+

ATPase associated with cellular activities domain

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- EBPs

Enhancer binding proteins

- GAF

Cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases and FhlA

- PAS

Per-Arnt-Sim domain

- PRD

Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system regulation domain

- RR

Response regulator domain

- UAS

Upstream activator sequences

Authors’ contributions

X.N. performed comparative genomics analysis and wrote the manuscript. W.D. conducted EMSAs. C.Y. designed the research project and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31630003 and 31470168), National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1303303), and Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27020201). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed in this study were obtained from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and MicrobesOnline [61]. The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaoqun Nie, Email: niexiaoqun@sibs.ac.cn.

Wenyue Dong, Email: wydong2016@sibs.ac.cn.

Chen Yang, Email: chenyang@sibs.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Buck M, Cannon W. Specific binding of the transcription factor sigma-54 to promoter DNA. Nature. 1992;358(6385):422–424. doi: 10.1038/358422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morett E, Segovia L. The sigma 54 bacterial enhancer-binding protein family: mechanism of action and phylogenetic relationship of their functional domains. J Bacteriol. 1993;175(19):6067–6074. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6067-6074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush M, Dixon R. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of Sigma54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76(3):497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Studholme DJ, Dixon R. Domain architectures of sigma54-dependent transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(6):1757–1767. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1757-1767.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmona M, Magasanik B. Activation of transcription at sigma 54-dependent promoters on linear templates requires intrinsic or induced bending of the DNA. J Mol Biol. 1996;261(3):348–356. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francke C, Groot Kormelink T, Hagemeijer Y, Overmars L, Sluijter V, Moezelaar R, Siezen RJ. Comparative analyses imply that the enigmatic sigma factor 54 is a central controller of the bacterial exterior. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss V, Magasanik B. Phosphorylation of nitrogen regulator I (NRI) of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(23):8919–8923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reitzer L, Schneider BL. Metabolic context and possible physiological themes of sigma (54)-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65(3):422–444. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.422-444.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon R. The oxygen-responsive NIFL-NIFA complex: a novel two-component regulatory system controlling nitrogenase synthesis in gamma-proteobacteria. Arch of Microbiol. 1998;169(5):371–380. doi: 10.1007/s002030050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cases I, de Lorenzo V. Promoters in the environment: transcriptional regulation in its natural context. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(2):105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Verstraete I, Débarbouilé M, Klier A, Rapoport G. Interactions of wild-type and truncated LevR of Bacillus subtilis with the upstream activating sequence of the Levanase operon. J Mol Biol. 1994;241(2):178–192. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali NO, Bignon J, Rapoport G, Debarbouille M. Regulation of the acetoin catabolic pathway is controlled by sigma L in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(8):2497–2504. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2497-2504.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tracy BP, Jones SW, Fast AG, Indurthi DC, Papoutsakis ET. Clostridia: the importance of their exceptional substrate and metabolite diversity for biofuel and biorefinery applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23(3):364–381. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. Commensal clostridia: leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 2013;5(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SY, Park JH, Jang SH, Nielsen LK, Kim J, Jung KS. Fermentative butanol production by clostridia. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101(2):209–228. doi: 10.1002/bit.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake HL, Gossner AS, Daniel SL. Old acetogens, new light. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1125:100–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brazier JS, Duerden BI, Hall V, Salmon JE, Hood J, Brett MM, McLauchlin J, George RC. Isolation and identification of Clostridium spp. from infections associated with the injection of drugs: experiences of a microbiological investigation team. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51(11):985–989. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-11-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbe S, Van Mellaert L, Anne J. The use of clostridial spores for cancer treatment. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101(3):571–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araki Y, Andoh A, Takizawa J, Takizawa W, Fujiyama Y. Clostridium butyricum, a probiotic derivative, suppresses dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13(4):577–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerritsen J. The genus Romboutsia : genomic and functional characterization of novel bacteria dedicated to life in the intestinal tract. Wageningen University: Wageningen; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nie X, Yang B, Zhang L, Gu Y, Yang S, Jiang W, Yang C. PTS regulation domain-containing transcriptional activator CelR and sigma factor sigma (54) control cellobiose utilization in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Mol Microbiol. 2016;100(2):289–302. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappas M, Schumacher J, Beuron F, Niwa H, Bordes P, Wigneshweraraj S, Keetch CA, Robinson CV, Buck M, Zhang X. Structural insights into the activity of enhancer-binding proteins. Science. 2005;307(5717):1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jovanovic G, Weiner L, Model P. Identification, nucleotide sequence, and characterization of PspF, the transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli stress-induced psp operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(7):1936–1945. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1936-1945.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher J, Joly N, Rappas M, Zhang X, Buck M. Structures and organisation of AAA+ enhancer binding proteins in transcriptional activation. J Struct Biol. 2006;156(1):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor BL, Zhulin IB. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63(2):479–506. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.479-506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry JT, Crosson S. Ligand-binding PAS domains in a genomic, cellular, and structural context. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlensog V, Lutz S, Bock A. Purification and DNA-binding properties of FHLA, the transcriptional activator of the formate hydrogenlyase system from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(30):19590–19596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buck M, Miller S, Drummond M, Dixon R. Upstream activator sequences are present in the promoters of nitrogen fixation genes. Nature. 1986;320:374. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Bailey TL, Noble WS. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 2007;8(2):R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. Compilation and analysis of sigma (54)-dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(22):4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cases I, Ussery DW, de Lorenzo V. The sigma54 regulon (sigmulon) of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5(12):1281–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barker HA. Amino acid degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:23–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riedel T, Wetzel D, Hofmann JD, Plorin S, Dannheim H, Berges M, Zimmermann O, Bunk B, Schober I, Sproer C, et al. High metabolic versatility of different toxigenic and non-toxigenic Clostridioides difficile isolates. Int J Med Microbiol. 2017;307(6):311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann-Schaal M, Hofmann JD, Will SE, Schomburg D. Time-resolved amino acid uptake of Clostridium difficile 630Δerm and concomitant fermentation product and toxin formation. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:281. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0614-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadtman TC, Elliott P. Studies on the enzymic reduction of amino acids. II. Purification and properties of D-proline reductase and a proline racemase from Clostridium sticklandii. J Biol Chem. 1957;228(2):983–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouillaut L, Self WT, Sonenshein AL. Proline-dependent regulation of Clostridium difficile Stickland metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(4):844–854. doi: 10.1128/JB.01492-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Darley D, Buckel W. 2-Hydroxyisocaproyl-CoA dehydratase and its activator from Clostridium difficile. FEBS J. 2005;272(2):550–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlsson S, Burman LG, Akerlund T. Suppression of toxin production in Clostridium difficile VPI 10463 by amino acids. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 7):1683–1693. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karlsson S, Lindberg A, Norin E, Burman LG, Akerlund T. Toxins, butyric acid, and other short-chain fatty acids are coordinately expressed and down-regulated by cysteine in Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 2000;68(10):5881–5888. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5881-5888.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubois T, Dancer-Thibonnier M, Monot M, Hamiot A, Bouillaut L, Soutourina O, Martin-Verstraete I, Dupuy B. Control of Clostridium difficile physiopathology in response to cysteine availability. Infect Immun. 2016;84(8):2389–2405. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00121-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu H, Yang Y, Wang M, Chen S, Wang H, Li S, Ma Y, Wang J. Novel cysteine Desulfidase CdsB involved in releasing cysteine repression of toxin synthesis in Clostridium difficile. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:531. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Li X, Mao Y, Blaschek HP. Genome-wide dynamic transcriptional profiling in Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 using single-nucleotide resolution RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raedts J, Siemerink MA, Levisson M, van der Oost J, Kengen SW. Molecular characterization of an NADPH-dependent acetoin reductase/2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase from Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(6):2011–2020. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04007-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopke M, Gerth ML, Maddock DJ, Mueller AP, Liew F, Simpson SD, Patrick WM. Reconstruction of an acetogenic 2,3-butanediol pathway involving a novel NADPH-dependent primary-secondary alcohol dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(11):3394–3403. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00301-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liew F, Henstra AM, Kpke M, Winzer K, Simpson SD, Minton NP. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium autoethanogenum for selective alcohol production. Metab Eng. 2017;40:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willis AT, Hobbs G. Some new media for the isolation and identification of clostridia. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959;77(2):511–521. doi: 10.1002/path.1700770223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drake HL, Küsel K, Matthies C. Acetogenic prokaryotes. Prokaryotes. 2006;2:354–420. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valgepea K, Loi KQ, Behrendorff JB, Lemgruber RSP, Plan M, Hodson MP, Kopke M, Nielsen LK, Marcellin E. Arginine deiminase pathway provides ATP and boosts growth of the gas-fermenting acetogen Clostridium autoethanogenum. Metab Eng. 2017;41:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hocq R, Bouilloux-Lafont M, Lopes Ferreira N, Wasels F. Sigma (54) (sigma(L)) plays a central role in carbon metabolism in the industrially relevant Clostridium beijerinckii. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7228. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43822-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Jiao S, Lv J, Du R, Yan X, Wan C, Zhang R, Han B. Sigma factor regulated cellular response in a non-solvent producing Clostridium beijerinckii degenerated strain: a comparative transcriptome analysis. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:23. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aravind L, Ponting CP. The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22(12):458–459. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anantharaman V, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Regulatory potential, phyletic distribution and evolution of ancient, intracellular small-molecule-binding domains. J Mol Biol. 2001;307(5):1271–1292. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D37–d42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dago AE, Wigneshweraraj SR, Buck M, Morett E. A role for the conserved GAFTGA motif of AAA+ transcription activators in sensing promoter DNA conformation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(2):1087–1097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305(3):567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahsay RY, Gao G, Liao L. An improved hidden Markov model for transmembrane protein detection and topology prediction and its applications to complete genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1853–1858. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dehal PS, Joachimiak MP, Price MN, Bates JT, Baumohl JK, Chivian D, Friedland GD, Huang KH, Keller K, Novichkov PS, et al. MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mironov AA, Vinokurova NP. Gel'fand MS: [software for analyzing bacterial genomes] Mol Biol (Mosk) 2000;34(2):253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Novichkov PS, Rodionov DA, Stavrovskaya ED, Novichkova ES, Kazakov AE, Gelfand MS, Arkin AP, Mironov AA, Dubchak I. RegPredict: an integrated system for regulon inference in prokaryotes by comparative genomics approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W299–W307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodionov DA. Comparative genomic reconstruction of transcriptional regulatory networks in Bacteria. Chem Rev. 2007;107(8):3467–3497. doi: 10.1021/cr068309+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of Clostridiales species containing σ54 (SigL) and EBPs. Table S2. Identified EBPs in Clostridiales. Table S3. Reconstructed regulons of EBPs in Clostridiales. Table S4. Primers used in this study. (PDF 1577 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study were obtained from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and MicrobesOnline [61]. The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files.