Abstract

Aim:

Magnetic hyperthermia is limited by the low selective susceptibility of neoplastic cells interspersed within healthy tissues, which we aim to improve on.

Materials & methods:

Two superparamagnetic calcium phosphates nanocomposites, that is, iron-doped hydroxyapatite and iron oxide (Mag) nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate (Mag@CaP), were synthesized and tested for selective activity against brain and bone cancers.

Results:

Nanoparticle uptake and intracellular localization were prerequisites for reduction of cancer viability in alternate magnetic fields of extremely low power. Sheer adsorption onto the outer membrane was not sufficient to produce this effect, which was extremely significant for Mag@CaP and iron-doped hydroxyapatite, but negligible for Mag, demonstrating benefits of combining magnetic iron with calcium phosphates.

Conclusion:

Such selective effects are important in the global effort to rejuvenate clinical prospects of magnetic hyperthermia.

Keywords: : calcium phosphate, composite nanoparticles, glioblastoma, magnetic hyperthermia, nanoparticles, osteosarcoma

Magnetic hyperthermia (MH) is an anticancer therapeutic procedure based on the administration of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) that, when subjected to an alternating magnetic field (AMF), act as thermo-seeds and generate heat at the local level, causing irreversible damage to the cells [1–3]. First attempted in 1957 for the treatment of cancer [4], MH used to be considered as one of the most promising therapies for the neoplastic disease in the research stage [5]. One of the early expectations was that its localized action [6] consequential to the ability of MNPs to be injected in the proximity of the tumors would result in lesser side effects compared with chemotherapy and radiotherapy [7]. However, despite the recent advancements and promising results from clinical trials, the use of MH alone in the treatment of cancer has been in steady decline over the past two decades [8] and it is currently used only in Europe as an adjuvant for chemotherapy and radiotherapy [9].

One of the reasons for this decline is that the classical assumption [10] that the cancer cells are more sensitive to heat than healthy cells is not a universal matter of fact, but it rather depends on the types of cells and tissues, on the composition and the rheology of the medium and on the physicochemical features of the MNPs [11]. The efficacy of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs), which are the most used thermo-seeds in MH [12], is also hindered by their low uptake by cancer cells [13], which has brought the feasibility of the classical concept [14] of intracellularly precise MNPs localization for a more effective MH to question. Therefore, the search of new ways to achieve the selective activity of MNPs toward cancer cells is essential to improve the efficacy of MH and rejuvenate its clinical prospects.

The main aim of this study was to evaluate the interaction of different cancer cells with two differently designed composites combining calcium phosphates and MNPs as potential MH agents. Calcium phosphates have been selected as the main component of the composites because their similarity to the inorganic phase of bone and teeth endows them with superior biodegradability, biocompatibility and nonimmunogenicity profiles [15], thanks to which they have a clear advantage over metallic MNPs [16]. Calcium phosphates are intrinsically diamagnetic, and two different approaches are commonly used to prepare magnetic materials based on them. The first is to introduce selected amounts of Fe ions as dopants in their structure. Hydroxyapatite (HA) is a calcium phosphate phase particularly convenient for foreign ion accommodation because of its extraordinarily flexible lattice [17]. The second approach is based on the synthesis of SPION-calcium phosphate hybrid composites, for which several synthetic strategies have been reported. The most common one consists in the separate preparation of SPIONs and calcium phosphate nanoparticles, and in their subsequent blending by different homogenization methods, for example, a mechanochemical reaction [18,19] or a hydrothermal treatment [20]. Other synthesis methods may involve co-precipitation of SPIONs and calcium phosphate nanoparticles, for example, by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis [21], or sequential aqueous precipitation of the two phases, which may result in core-shell nanoparticles under certain conditions [22]. Still, several problems are associated with SPION-calcium phosphate composites, including the uncontrolled growth of calcium phosphates during the synthesis, providing MNPs with too large dimensions at the expense of the loss of their superparamagnetism (e.g., lower mass magnetization), thus limiting their use in MH. Therefore, conceiving new synthetic strategies to produce SPION-calcium phosphate composites, conducive to creating interesting synergies between the components, can be of immense importance.

In this study, we comparatively evaluated the biological response of human primary lung fibroblasts and different cancerous cell lines to different magnetic calcium phosphates, including iron-doped HA (FeHA) and MNPs coated with amorphous calcium phosphate (Mag@CaP). Prior to the biological analyses, we compared the physicochemical properties of the two types of MNPs using spectroscopic, diffractometric and microscopic techniques. To elucidate the effects of individual components comprising these MNPs, they were included in most analyses. Osteosarcoma (OS) and glioblastoma (GB) cell lines were selected to study the interaction with these two types of MNPs because they are two of the most challenging types of cancer to treat. OS is one of the most common types of cancer in children [23], while bone is also a frequent site of metastasis of other forms of cancer [24]. Whereas the mortality of children with cancer has been reduced by over 50% since the mid-1970s, there has been no improvement in the survival of children diagnosed with OS (60% for 5-year overall survival) in the same period and the very same therapies are prescribed to these children as in the late 1970s [25]. Since calcium phosphate itself is the central bone mineral component, its use presents a natural choice for the controlled delivery of therapies to the malignant regions of bone. In contrast, GB is the most common and aggressive malignant primary brain tumor in humans and despite decades of intense research, the survival of GB patients has been only marginally improved and still cannot exceed 24 months even with the use of concomitant chemotherapies and radiation in addition to surgical resection [26]. Therefore, there has been an impetus to supplement this classical cancer therapy triad with novel approaches. One such take on MH in a novel, intracellular form, relying on the AMF of ultralow intensity and prior nanoparticle uptake, was tested in this study as a potential substitute of or addendum to the standard therapies for OS and GB.

Materials & methods

Synthesis of FeHA & HA nanoparticles

Superparamagnetic iron-substituted HA (FeHA) nanoparticles were synthesized according to the method reported by Tampieri et al. with minor modifications [27]. Briefly, a solution obtained by mixing 8.87 g of H3PO4 (>85 wt% in water, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with 30 ml of ultrapure water was added dropwise into a Ca(OH)2 (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) suspension (10.0 g in 50 ml) containing FeCl2·4H2O (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) (2.57 g) and FeCl3·6H2O (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) (3.53 g) in a 1:1 molar ratio at 45°C under vigorous stirring. When the neutralization reaction was completed, the growth solution was kept at 45°C under constant stirring at 400 r.p.m. for 3 h and then left still at room temperature overnight. FeHA was recovered by centrifugation (15,000 r.p.m., 5 min, 4°C) of the reaction mixture, repeatedly rinsed with water and finally freeze dried.

Iron-free HA nanoparticles were prepared similarly to FeHA, but without adding any iron precursor to the Ca(OH)2 suspension. The same experimental conditions as those used to synthesize FeHA (e.g., reaction temperature, Ca/P ratio, maturation time, etc.) were employed.

Synthesis of Mag, CaP & Mag@CaP nanoparticles

Iron oxide (Mag) nanoparticles were synthesized as reported by Pušnik et al. with minor modifications [28]. Briefly, 7.50 g of FeSO4·7H2O (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) and 6.21 g of FeCl3·6H2O (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved together in 500 ml of ultrapure water and kept magnetically stirred at room temperature and under atmospheric conditions. Ammonia solution (NH3, 25 wt% in water, Sigma-Aldrich) was added dropwise up to pH 11.0 and the mixture was left to age at room temperature for 30 min under continuous stirring. The reaction product was collected by centrifugation (15,000 r.p.m., 5 min, 4°C) repeatedly rinsed with water, and finally re-suspended in water at 20 mg/ml.

Calcium phosphate (CaP) nanoparticles were synthesized by mixing two solutions (1:1 v/v, 250 ml total) at 37°C: (i) 100 mM CaCl2·2H2O (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) + 400 mM Na3(C6H5O7)·2H2O (Na3(Cit), ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich) + 10 ml NaOH 0.1 M (ACS reagent ≥97%, Sigma-Aldrich) and (ii) 120 mM Na2HPO4 (ACS reagent ≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich). The mixture was left to age for 5 min, then nanoparticles were repeatedly washed with ultrapure water by centrifugation (15,000 r.p.m., 5 min, 4°C) and freeze dried overnight at -50°C under a vacuum of 3 mbar.

Iron oxide-calcium phosphate (Mag@CaP) nanocomposites were synthesized similarly to CaP, but including the addition of Mag (12.5 mg) in the solution (ii). The same experimental conditions as those used to synthesize CaP (e.g., reaction temperature, maturation time, etc.) were employed.

Characterization of the nanoparticles

The x-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples were recorded on a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a Lynx-eye position sensitive detector using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å) generated at 40 kV and 40 mA. XRD patterns were recorded in the 2θ range from 10 to 60 with a step size (2θ) of 0.02° and a counting time of 0.5 s.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analyses were performed on a Nicolet 5700 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., MA, USA) with a resolution of 4 cm-1 by accumulation of 64 scans covering the 4000–400 cm-1 range, using the KBr pellet method.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) were carried out on a simultaneous thermal analyzer (STA 449 Jupiter Netzsch Geratebau, Selb, Germany). Approximately 10 mg of the sample was weighed in a platinum crucible and heated from the room temperature to 600°C under air flow with the heating rate of 10°C min-1.

The nanoparticle morphology and size in a dry state were analyzed on a Tecnai F20 (FEI company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with a Schottky emitter and operating at 120 and 200 keV. Ten microliters of FeHA, HA and CaP suspended in 0.1 wt% citrate buffer at 10.0 mg ml-1 were dissolved in 5 ml of isopropanol and treated with ultrasound. A droplet of the resulting finely dispersed suspensions was evaporated at room temperature and under the atmospheric pressure on a holey carbon film supported on a copper grid. The same procedure was followed for Mag and Mag@CaP, with the difference that the suspensions of these nanoparticles were evaporated on a continuous carbon film.

Calcium, phosphate and iron contents were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) on a Liberty 200 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies 5100 ICP-OES, CA, USA). Twenty milligrams of the samples were dissolved in 50 ml of 2 wt% HNO3 (puriss. p.a. ≥65%, Sigma-Aldrich) or 2 wt% HCl (puriss. p.a ≥37%, Sigma-Aldrich) solutions prior to the analysis.

ζ-potential and hydrodynamic diameter distributions were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) on a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Malvern, UK). ζ-potentials were quantified by Laser Doppler Velocimetry as the electrophoretic mobility using a disposable electrophoretic cell (DTS1061, Malvern Instruments Ltd). An aliquot of each sample was suspended in 0.01 M HEPES buffer at pH = 7.4 to reach a concentration of 1.0 mg/ml. Ten runs of 30 s were performed for each measurement and four measurements were carried out for each sample over the period of 1 h.

Magnetic characterization

DC magnetometry was performed on a commercial superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) MPMS2 by Quantum Design, Inc. (CA, USA). Specifically, isothermal magnetization at 5 and 300 K; and temperature-dependent magnetization were measured. The latter was measured at low field (10 and 100 Oe) from T = 5 K up to T = 350 K in both zero field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) modes.

Ion release

The rate of ion release was evaluated by mixing 15 mg of the samples with 5 ml of 0.1 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) or 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.5). The suspension was continuously shaken at 37°C. At scheduled times ranging from 1 to 48 h, the supernatant was separated from the solid phase by centrifugation and rinsed with the fresh buffer. The concentration of calcium ions released in the supernatant was determined using ICP-OES.

Cell culture

K7M2-pCl Neo mouse OS cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collections (VA, USA). U87-MG and E297 human GB cells were a gift from Herbert H Engelhard (University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Neurosurgery). E297 is a highly aggressive patient cell line extracted in 1991 [29], which does not require immunosuppressants to grow tumors on rats. Primary human lung fibroblasts (HLFs) were a gift from Rennolds Ostrom (Chapman University, CA, USA). All cell lines with the exception of the HLFs were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies, CA, USA) to prevent bacterial and fungal contamination and were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. HLFs were cultured in the lung/cardiac fibroblast growth medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies). Cell lines were grown to confluency before being plated on 12-mm circular glass cover slips or 24/48-well culture plates for assaying.

3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide viability assay

A 12 mM 3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) stock solution was prepared by adding 1 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a 5 mg vial of MTT and vortex mixing to ensure complete dissolution. Cell lines were grown in 48-well plates until confluency. Upon confluency, 1, 2.5 or 5 mg/ml of nanoparticles were added to each well. After 24 h of incubation, cells were washed with PBS and 275 μl of 1:10 MTT/media v/v were added into each well. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C, 211 μl of the solution were carefully removed and 125 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide were added to each well. Plates were placed in a 37°C incubator shaker at 120 r.p.m. for 30 min before measuring the absorbance at 570 nm using the BMG LABTECH FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (Ortenberg, Germany). To account for the effect of nanoparticles per se on the absorbance in the lysate, the sample control absorbance was subtracted from that of the nanoparticle samples. Viability was expressed in percentages and normalized to the absorbance of the negative control. All the sample groups were analyzed in triplicates.

Immunofluorescent staining & confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed and stained for nuclei, f-actin filaments and CaP 48 h after adding nanoparticles to the culture at the concentration of 5 mg/ml. Cells were fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and washed 3 × 10 min in PBS, then blocked at room temperature for 1 h in the blocking solution (2% bovine serum albumin, 0.5% Triton-X in PBS), washed 3 × 10 min with PBS again and stained with Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin (1:400), OsteoImage reagent (1:100) and NucBlue® Fixed Cell ReadyProbes™ reagent (Molecular Probes, OR, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After the incubation, cells were washed 3 × 5 min with OsteoImage wash buffer and mounted using Prolong Diamond mounting media (Life Technologies). Images were acquired on a T1-S/L100 inverted epifluorescent confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). All the samples were analyzed in triplicates.

Magnetic hyperthermia

Cells were seeded in μ-Slide plates (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) at 2 × 104 cells/ml. After being exposed to nanoparticles for different periods of time, they were placed inside a multiturn helical coil of an induction heating system (Ultraflex SH2/350, FL, USA) and surrounded by an insulating box, which prevented heat dissipation and maintained the temperature of the cell culture close to 37°C, before being subjected to a low-intensity AMF (350 kHz, 1.16 μT, 1 kW) in 100 μl of complete DMEM media under ambient conditions for 30 min. With the H·f value of 4.5·105 A m-1 s-1, the intensity and frequency of the AMF were markedly lower than the biosafety limit of 6.7·109 A m-1 s-1. After 30 min, the plates were removed from the chamber, placed back into the cell culture incubator with 200 μl of DMEM media and allowed to recover for 24 h. The cell signaling cascade required to activate the apoptotic cell death can take hours to activate after the initial stress, the reason for which cells were given 24 h to recover or die before they were assessed for viability. After the recovery, the viability of cells was measured using the MTT assay. All the samples were analyzed in triplicates.

Flow cytometry

In addition to fluorescent cell staining, the cellular uptake of nanoparticles was analyzed using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS, Becton Dickinson FACSVerse, IL, USA). Cells were grown to confluency in aforementioned growth conditions in 24-well plates before 5 mg/ml of the nanoparticles were added to them. After 24-h incubation at 37°C, the cells were rinsed with PBS and trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. The cells that had uptaken the nanoparticles were sorted from the untreated, control cells based on changes in the increased side scatter indicative of increased granularity in the cells due to intracellular localization of nanoparticles uptaken by the cells. All the samples were analyzed in triplicates.

Antibacterial assays

Selected nanoparticles were tested for their antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC27661 (Carolina Biological, NC, USA), Salmonella enteritidis ATCC13076 (Carolina Biological) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853 (Carolina Biological) using the agar diffusion assay. Ten milligrams of the powder were placed onto a bacterium-infused nutrient agar plate with the spot radius of 1 cm. The plates were then allowed to incubate for 24 h at 37°C. The zone of inhibition was used to visually gauge the antibacterial activity of the cements.

Results

XRD patterns of Mag, CaP, Mag@Cap, HA and FeHA are reported in Figure 1. The pattern registered on Mag nanoparticles features relatively broad reflections with d-spacings consistent with the crystalline spinel iron oxide (Fe3O4/γ-Fe2O3) structure having a cubic unit cell and Fd3m space group (JCPDS no. 04-0755), typically forming by aqueous co-precipitation of Fe2+/Fe3+ ions. The average crystallite size calculated from the broadening of (311), (400) and (440) peaks using Scherrer’s equation [30] is 37 ± 2 nm for the shape factor of 0.9.

Figure 1. . X-ray diffraction patterns of iron oxide, calcium phosphate, iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite and iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles.

Miller indices are relative to hydroxyapatite (JCPDS no. 09-432) and to the crystalline spinel iron oxide (JCPDS no. 04-0755) structure reflections (reflections of this latter are identified by asterisk).

CaP: Calcium phosphate; HA: Hydroxyapatite; FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous CaP.

The XRD pattern of CaP features a broad, diffuse peak in the 2θ range from 25 to 38°, corroborating the formation of a very poorly crystalline phase without a long range order, very close to an amorphous one. The XRD pattern of Mag@CaP displays the more intense diffraction peaks of Mag, but also the broad peak in 25–38° 2θ range attributed to amorphous CaP. In addition, the weak reflection of the (002) plane of poorly crystalline HA at 26.1° is overlapped with the broad band of the amorphous phase. The presence of this peak is ascribed to the partial conversion of the amorphous to crystalline phase when Mag is present. The average crystallite size of the iron oxide phase calculated from the broadening of (311), (400) and (440) diffraction peaks of Mag@CaP using Scherrer’s equation is 39 ± 4 nm. This value matches the one calculated for Mag, confirming that the deposition of the CaP phase has not altered the size of iron oxide nanoparticles.

The XRD patterns of FeHA and HA demonstrate the occurrence of low-crystalline HA (JCPDS no. 09-432) as the main phase. The presence of the peak at 35.4° in the XRD pattern of FeHA, corresponding to the (311) plane of Fe3O4/γ-Fe2O3 (JCPDS no. 04-0755), reveals the presence of a small amount of magnetite/maghemite iron oxide as the secondary phase. In this case, iron oxide crystallites are smaller compared with those in Mag and Mag@CaP, and their average size calculated from the broadening of (311) peak using Scherrer’s equation was estimated to be in the 5–10 nm range. As already described elsewhere [31,32], both HA and FeHA crystallites are elongated along the c-axis and display a high aspect ratio, as evidenced by the higher relative intensity of the peak at 25.8° corresponding to the (002) plane in HA than in stoichiometric HA (40% of the most intense (211) reflection). The addition of iron also decreases the crystallinity of the material, as evident from the broader diffraction peaks in FeHA compared with HA.

FTIR spectra of the samples (Figure 2) confirm the presence of calcium phosphate as the dominant phase in FeHA and Mag@CaP. Thus, the most prominent IR band in both materials was the triply degenerated asymmetric stretching vibration mode (ν3) of the phosphate tetrahedron, located in the 995–1120 cm-1 range. This band has a significantly higher full width at half maximum value in Mag@CaP and particularly CaP than in HA and FeHA, where it is also evidently split. Full width at half maximum is inversely proportional to the crystallinity of a material, implying a larger content of the amorphous phase in CaP and Mag@CaP compared with HA and FeHA, which is in agreement with the results of the XRD analysis. Similarly, the triply degenerated bending mode (ν4) of the phosphate tetrahedron in the 550–650 cm-1 range adopts a sharper, characteristically triplet fine structure in crystalline HA and FeHA, but convolutes into a single broad band in CaP. In Mag@CaP, however, the ν4 bending mode possesses a finer structure, suggesting a more crystalline nature of CaP formed in the presence of Mag. T1u phonon modes of Mag appear in the same range, at 450 and 570 cm-1, and are shifted with respect to pure Mag, corroborating the generation of a composite material with an intimate interaction between the components. The band at circa 1580 cm-1 in the spectrum of CaP is assignable to the antisymmetric stretch (ν3) of COO- in the citrate ion, which was used as the dispersant. Another signature band of this ion discerned in the spectrum of CaP is its symmetric stretch (ν1) at circa 1412 cm-1 [33]. Surprisingly, the signals of citrate are not present in the spectra of Mag@CaP, which is more abundant in carbonate anions derived from atmospheric CO2 adsorbed on the surface and/or entrapped within the particles during the synthesis and storage. In fact, the out-of-plane bending (ν2) of the carbonate ion at 880 cm-1 and the ν3 stretching mode of the carbonate ion in the 1400–1600 cm-1 range are more intense in Mag@CaP than in other samples.

Figure 2. . Fourier-transform infrared spectra of iron oxide, calcium phosphate, iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite and iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles.

Major bands, originating from Fe-O, P-O and C-O stretches (ν1 and ν3), C-O bending mode (ν2) and H-O-H scissoring mode (δ), are denoted in the graph.

CaP: Calcium phosphate; HA: Hydroxyapatite; FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous CaP.

Iron oxide, itself, possessing the spinel structure, displays the two highest frequency T1u phonon modes peaking at 450 and 570 cm-1. The other two, lower frequency modes lie below the spectral range used, at 210 and 360 cm-1. The missing finer spectral lines within these relatively broad bands suggest a moderate to high concentration of vacancies within the iron oxide structure [34]. Since magnetite and maghemite exhibit an identical high frequency T1u vibration profile, it is impossible to distinguish the two phases based on FTIR spectra.

Chemical compositions of the samples, as determined from the ICP-OES analysis, are reported in Table 1. Despite the incomplete precipitation of ferrous and ferric solutes during the formation of FeHA and the complete incorporation of Mag into Mag@CaP, the total iron content of FeHA is higher than that of Mag@CaP (8.5 vs 6.3 wt%). Based on its iron content, it can be estimated that Mag@CaP is composed of circa 96 wt% of calcium phosphate and circa 4% of iron oxide. The amount of the iron oxide phase in FeHA and the relative weight content of iron confined to the oxide phase were assessed by the Rietveld analysis of the respective XRD pattern, as previously reported [27,31], while the content of iron ions in the lattice of FeHA was quantified by subtracting the amount of iron in iron oxide from the total iron content derived from the ICP-OES analysis. As expected, both HA and CaP were iron free and exhibited a similar Ca/P atomic ratio of circa 1.6. Ca/P atomic ratio in Mag@CaP is also very close to this value, indicating that no substitution of iron ions for calcium ions has taken place. On the other hand, Ca/P atomic ratio in FeHA was significantly lower than 1.6, and (Fe+Ca)/P atomic ratio was close to this value. This may indicate that Fe2+ ions rather than Fe3+ ions present the predominant iron cation in the FeHA lattice because Fe2+ and Ca2+ have an identical valence state and can engage in 1:1 substitution in the HA structure. More probably, however, any loss of Ca2+ due to replacement of Ca2+ by ferric, Fe3+ ions would be compensated by the incorporation of carbonates in place of phosphates, so that, as the result, the Ca/P atomic ratio does not deviate significantly from the stoichiometric 1.67 value.

Table 1. . Chemical composition of the samples.

| Samples | Iron oxide phase | Calcium phosphate phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe (wt%) | Fe (wt%) | Fe/Ca (mol) | Ca/P (mol) | (Fe+Ca)/P (mol) | |

| HA | – | – | – | 1.62 | – |

| FeHA | 3.1† | 5.4 | 0.21 | 1.38 | 1.61 |

| Mag@CaP | 6.3‡ | 4.5 | 0.15 | 1.62 | 1.89 |

| CaP | – | – | – | 1.66 | – |

| Mag | 71.0 | – | – | – | – |

The table was divided in two parts, one for the iron oxide phase and the other for the calcium phosphate one, so as to highlight the differences among the samples. Data are reported as means of three independent analyses (relative standard deviation <5%).

Determined by Rietveld analysis of the x-ray diffraction pattern.

Determined by the ratio between the specific magnetization at saturation of Mag@CaP and that of Mag.

CaP: Calcium phosphate; FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite; HA: Hydroxyapatite; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous CaP.

Thermogravimetric (TG) curves of the samples reported in Supplementary Figure 1 show that CaP and Mag@CaP, being composed for the major part of the amorphous calcium phosphate phase, are less thermally stable than the crystalline samples, yielding weight losses of about 23 and 20 wt% at 600°C, respectively. TGA curves of Mag, FeHA and HA present a small, gradual weight loss of about 1.2, 8 and 9 wt% at 600°C, respectively, which is attributed to the evaporation of water molecules absorbed on the nanoparticles. In contrast, TG and derivative thermogravimetric curves of CaP and Mag@CaP (Supplementary Figure 2) display three weight losses: the first one, from the room temperature to about 180°C, is due to adsorbed water; the second one, from about 180–400°C, is attributed to the entrapped, lattice water; and the third, from 400–600°C, is due to the removal of organic molecules, such as carbonate and citrate. Unlike anhydrous HA, amorphous CaP contains a stoichiometric amount of lattice water, representable [35] as CaxHy(PO4)z · nH2O, where n = 3–4.5, which explains the steadier water release peaks on TG diagrams, extending over wider temperature ranges than in HA. Comparison of the peak temperatures for the three phase transitions recorded for CaP and Mag@CaP shows the identical temperature for the surface water desorption peak, at 95°C for both samples, suggesting that the structure and the bonding of this water to the particles is the same in both samples. However, the release of lattice water is shifted to a higher temperature for Mag@CaP compared with CaP (300 vs 260°C, respectively), indicating that this water requires more energy to be released in the presence of the magnetic component and also indirectly confirming the tight physical contact between the two phases. In contrast, the release of the organic component, primarily citrate ions, proceeds with a lesser energy input in CaP compared with Mag@CaP, thus indicating that these ions, as expected, have a greater affinity for CaP than for Mag.

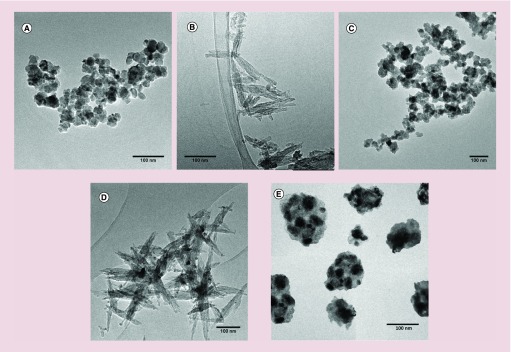

TEM analysis confirmed this tight contact between the two components in Mag@CaP and showed that these are core-shell materials based on iron oxide nanoparticles dispersed in the matrix of calcium phosphate (Figure 3). Iron oxide nanoparticles of Mag@CaP appeared homogeneously distributed within the CaP matrix and less aggregated compared with Mag. The TEM analysis also revealed that Mag, CaP and Mag@CaP nanoparticles are moderately agglomerated, with the caveat that some agglomeration is also the artifact of the microscopic analysis. These three types of nanoparticles all had round-shaped morphologies, but the size range of the individual nanoparticles increases going from Mag (30–40 nm) to CaP (30–60 nm) and finally to Mag@CaP (150 nm).

Figure 3. . Transmission electron microscopy images of iron oxide (A), hydroxyapatite (B), calcium phosphate (C), iron-doped hydroxyapatite (D) and iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate (E).

The scale bar is 100 nm.

FeHA sample, in contrast, is composed of nanoparticles with needle-like morphologies intermixed with round-shaped iron oxide nanoparticles having 5–10 nm in diameter. The length of the needle-shaped nanoparticles is typically in the 75–125 nm size range and their width is in the 15–25 nm range. These results are in good agreement with the crystallite sizes estimated from the XRD analysis. HA displays a similar morphology and dimensions as FeHA, though obviously no external Fe-rich phases were observed.

Hydrodynamic diameters measured from DLS (Table 2) revealed that the dimensions of FeHA and HA in suspensions are comparable to those detected in the dry state under TEM, while Mag and particularly Mag@CaP and CaP are more aggregated, having hydrodynamic diameters in the 650–900 nm range. Polydispersity index of Mag@CaP and CaP is also higher than 0.3, indicating a significant polydispersity of the suspensions. The given size range should not be an obstacle to the parenteral route of administration, given that it is still smaller than 5–10 μm diameter of the finest capillaries in the body and that 20–60-μm-sized HA particles were intravenously administered without any adverse effects [36].

Table 2. . Hydrodynamic diameters, polydispersity index and ζ-potential of the samples.

| Samples | Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential at pH 7.4 (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 160 ± 2 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | -17.4 ± 1.3 |

| FeHA | 208 ± 10 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | -17.6 ± 0.5 |

| Mag@CaP | 737 ± 83 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | -31.5 ± 1.0 |

| CaP | 854 ± 52 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | -35.2 ± 1.9 |

| Mag | 132 ± 6 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | -51.3 ± 1.0 |

FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite; HA: Hydroxyapatite; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate; PDI: Polydispersity index.

ζ-potentials of all the samples at the physiological pH are negative, with HA and FeHA having the lowest and highly similar absolute values, lying just above the ±15 mV aggregation threshold (Table 2). The effective coating of Mag with CaP in Mag@CaP is corroborated by the shift of the ζ-potential value from -51.3 mV in Mag to -31.5 mV in Mag@CaP, as this latter value lies close to that of pure CaP (-35.2 mV).

Temperature-dependent and isothermal magnetization curves for all the iron-containing samples, namely FeHA, Mag and Mag@Cap, are reported in Figure 4. They show the temperature dependence of the ZFC and field-cooled (FC) M/H curves measured at the low field (10 and 100 Oe) in the 5–350 K temperature range. In the case of FeHA, the M/H graph presents a sharp bifurcation between ZFC and FC curves for T <250 K. Below this temperature, the FC magnetization increases with decreasing temperature, while the ZFC magnetization presents a broad peak centered at circa 100 K. This behavior is typical of an ensemble of MNPs within the superparamagnetic limit and with a broad size distribution.

Figure 4. . Temperature dependence of M/H for iron-containing samples.

FeHA ( zero field cooled (ZFC)

zero field cooled (ZFC)  field cooled (FC) upper panel), the measurements were performed at 10 and 100 Oe, while for Mag (

field cooled (FC) upper panel), the measurements were performed at 10 and 100 Oe, while for Mag ( ZFC

ZFC  FC lower panel, left scale) and Mag CaP (

FC lower panel, left scale) and Mag CaP ( ZFC

ZFC  FC lower panel right scale), the measurements were carried out only at 10 Oe.

FC lower panel right scale), the measurements were carried out only at 10 Oe.

CaP: Calcium phosphate; HA: Hydroxyapatite; FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous CaP.

The temperature dependence of M/H for Mag and Mag@CaP is similar, except in terms of their absolute value: M/H measured for Mag@CaP sample is significantly smaller than that of Mag, which is expected given the dispersion of Mag inside CaP. On the other hand, the temperature-dependent M/H curves of Mag-containing samples (Mag and Mag@CaP) and FeHA are pronouncedly different: while the former exhibits plateauing of the FC magnetization with respect to the ideal superparamagnetic system, the latter exhibits an almost linear decay of the ZFC magnetization as temperature decreases (Figure 4), indicating the presence of strong magnetostatic interactions between nanoparticles and/or nanoclusters.

Hysteresis loops measured at both 300 and 5 K for FeHA, Mag and Mag@CaP are reported in Figure 5, while those of CaP and HA were not reported for the sake of brevity, as these iron-free materials are diamagnetic. All the hysteresis loops are almost closed except at a very low temperature (Figure 5B, D & E) and the relative coercive forces at room temperature are far below 100 Oe for all the samples (Table 3), supporting the observation that all samples fall within the limits of superparamagnetic behavior at room temperature. Specific saturation magnetization values (Ms) at room temperature for FeHA and Mag@CaP are similar. The Ms of Mag is compatible with that reported for a mixture of maghemite/magnetite [37] and is in agreement with the results of the XRD analysis. At low temperature, the paramagnetic component is evident, mainly in FeHA. From the measurements carried out at room temperature, it was possible to estimate the paramagnetic fraction of each sample at about 20.3, 5.3 and 2.8 wt% for FeHA, Mag and Mag@CaP, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 5. . Isothermal magnetization hysteresis loops of FeHA (A & B), Mag (C & D) and Mag CaP (E & F).

Hysteresis loops were measured at 5 K (blue line) and 300 K (red line) up to 55 kOe, with a zoom in the low-field region.

FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate.

Table 3. . Main magnetic properties at room temperature for iron-doped hydroxyapatite, iron oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate samples.

| Sample | Ms (300 K) [emu/g] | Paramagnetic fraction (55 kOe) | Hc (300 K) (±10%) [Oe] |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeHA | 4.02 ± 0.02 | 0.203 ± 0.003 | 16 |

| Mag | 79.10 ± 0.20 | 0.053 ± 0.004 | 20 |

| Mag@CaP | 3.91 ± 0.01 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 68 |

The saturation magnetization, Ms, was determined from the linear fit of M/H versus 1/H for H >10 kOe. The paramagnetic fraction was calculated as [Ms(fit)-M(55 kOe)]/M(55 kOe). The coercive field was determined as [Hc(+)-Hc(-)]/2 because of the presence of a small exchange-bias effect.

FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate; Ms: Saturation magnetization value.

The released weight percentages of Ca2+ ions from all samples except Mag as a function of time at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 are reported in Figure 6, where the extent of Ca2+ release can be considered as a measure of their dissolution. CaP and Mag@CaP have very similar degradation profiles, and both of them dissolve much faster than HA and FeHA at both the acidic and physiological pHs. The two materials release approximately 25 wt% of Ca at the physiological pH after 48 h, and they are almost completely dissolved in acidic conditions after 8 h. The degradation of HA was more rapid than that of FeHA at both pHs, with >10 versus 7 wt% of released Ca2+, respectively, at the physiological pH after 48 h. Different dissolution rates of the two materials are even more evident at pH 5.5, where 65 wt% of HA gets dissolved versus only 31 wt% of FeHA after the same period of time. At both pH values, the solubility of CaP was considerably higher than that of HA, corroborating the higher endurance and resistance to degradation of crystalline samples over the amorphous ones.

Figure 6. . Calcium release assays.

Released mass percentages of Ca2+ from Mag@CaP, FeHA, HA and Mag as a function of time in acetate buffer at pH 5.5 (A) and in HEPES buffer at pH 7.4 (B). Error bars represent the relative standard deviations (<5%).

HA: Hydroxyapatite; FeHA: Iron-doped HA; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate.

Figure 7 presents the results of the viability assays run on healthy and cancerous cells challenged with three different doses of FeHA and Mag@CaP composite nanoparticles and their individual components. Primary HLF cells were used as the healthy cell line, and K7M2 murine OS cells and E297 and U87 human GB cells were used as the three cancer cell lines. Out of all the materials tested, the most positive selectivity and ‘targeting’ potential was exhibited by CaP: at the same, relatively high concentration of 5 mg/ml at which it was significantly toxic to E297 cells, it increased the viability of HLF cells by whole 25.4 ± 6.7%. At comparative dosages, HA appeared more toxic to all cells than Mag, but the same effect did not apply to CaP. CaP was also significantly more viable to healthy cells than crystalline HA, at all three particle dosages, suggesting the potential favorability of its use in cancer targeting over HA. Even though CaP, because of its amorphous nature and higher solubility, releases more Ca2+ ions to the medium than HA (Figure 4), the healthy cells appear not to be adversely affected by this. In contrast, no significant difference between the two powders was observed in E297 cells and in K7M2 and U87 cells at the lowest, 1 mg/ml dose. The effect of the lower viability due to CaP treatment was present in K7M2 cells at only the highest, 5 mg/ml dose and in U97 cells at the two highest doses: 2.5 and 5 mg/ml. Dose-dependent experiments also showed that HA and CaP, unlike their magnetic composites, display similar overall levels of cancer versus HLF cell selectivity. Positive selectivity was detected only for CaP at its highest concentration tested, 5 mg/ml, and only against E297 GB cells, suggesting the potential utility of this form of calcium phosphate primarily against this type of cancer.

Figure 7. . Cell viability assays.

Mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity indicative of cell viability determined by the optical density at λ = 570 nm in the 3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay after 24 h of incubation of human primary lung fibroblasts (HLFs), K7M2 osteosarcoma cells and E297 and U87 human glioblastoma cells with different dosages (1, 2.5 and 5 mg/ml) of FeHA, iron oxide nanoparticles coated with Mag@CaP, CaP, HA and Mag. Data points are shown as arithmetic means of biological replicates (n = 3) with error bars representing the standard deviation. Samples with a significantly (p < 0.05 with respect to the control group) different cell viability with respect to the control are marked with an asterisk.

CaP: Calcium phosphate; HA: Hydroxyapatite; HLF: Primary human lung fibroblast; FeHA: Iron-doped HA; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous CaP.

The addition of Fe ions to HA consistently and significantly increased the HLF cell viability, at all three particle doses, indicating the positive effect of this type of doping on healthy cells. These results comply with those previously reported on the higher proliferation of healthy osteoblast-like cells tested against FeHA with respect to those treated with HA [38]. This correlation was absent in K7M2 cells, but partially present in the two types of GB cells, specifically at the two highest doses, 2.5 and 5 mg/ml, for E297 and at the highest, 5 mg/ml dose for U87. FeHA, in fact, at any dose and against any cell type, was never significantly more toxic than HA. Compared with the beneficial effect that the addition of iron to HA had on all cells, the addition of Mag to CaP had the opposite effect, though only in HLF cells and, to some extent, E297 cells.

Whereas the toxicity of HA, be it pure or doped with Fe, was intensely dose dependent against HLF in the 1–5 mg/ml range and somewhat dose dependent against the three cancerous cell lines, the toxicity of the Mag@CaP composite and of its individual components was largely dose independent against the healthy HLFs and the K7M2 and E297 lines and intensely dose dependent against U87 cells. Since the dose dependency of the Mag@CaP composite against U87 cells followed the same trend as the dose dependency of its Mag component, it can be inferred that the latter had a dominant effect on this phenomenon over its CaP counterpart, which demonstrated the dose-dependent effect only in the 1–2.5 mg/mol range. Still, averaged across all four cell lines and particularly applying to the healthy HLFs, HA and CaP were more prone to exhibit dose dependency than the particles containing iron, be it in the ionic (FeHA) or the particulate (Mag@CaP) form.

The effect of combining the two Mag@CaP nanoparticle components, Mag and CaP, was also intensely cell and dose dependent. Thus, for example, for HLFs, at the lowest and the highest nanoparticle dose, a synergistic effect was observed, where the toxicity of the cells treated with the Mag@CaP composite was higher than that caused by any of its two individual components. In contrast, the viability of K7M2 cells treated with Mag@CaP particles was higher, albeit insignificantly, than that of the cells treated with the single components at all doses, and the same effect was observed in E297 cells in the 2.5–5 mg/ml dose range. At 5 mg/ml, U87 cell viability was significantly reduced after being treated with Mag@CaP and Mag particles, while it remained unchanged after being treated with CaP. Still, the lack of consistency in response means that it is difficult to pinpoint which of the two components is more responsible for causing the cancer versus healthy cell selectivity observed.

Detailed viability experiments run at different doses of different composite particles and their components helped us elucidate the most prospective conditions under which the positive targeting propensity and healthy versus cancer cell selectivity can be achieved. Thus, for composite particles, these conditions are found at high concentrations for Mag@CaP and at medium concentrations for FeHA. Specifically, the viability of HLFs and U87 GB cells dropped to a similarly significant degree after being treated with 5 mg/ml of Mag@CaP particles or with 2.5 mg/ml of FeHA. As for the individual components of composite particles, Mag impaired toxicity to U87 cells at the highest, 5 mg/ml concentration, but this was paralleled by a similar drop in the viability of HLFs. As already mentioned, CaP proved to be the most promising, as at the 5 mg/ml dose it impaired toxicity to E297 and increased the viability of HLFs compared with the untreated, negative control. This positive effect is, however, observed only at the highest, 5 mg/ml dose, and the inverse effect applied at the two lower dosages. This effect was also absent in K7M2 OS and U87 GB cells.

In addition to the tests on eukaryotic cells, the particles were tested against prokaryotic, bacterial cells, including Gram-negative E. coli, P. aeruginosa and S. enteritidis and Gram-positive S. aureus. Practically nil inhibition zone diameters were detected for most tested bacterial species, with only a very fine and limited inhibition zone observed around biofilm-forming P. aeruginosa treated with FeHA (Supplementary Figure 3). To some extent, this has suggested that the shielding of the iron component in core-shell particles minimizes the contact of the bacterial cells with iron ions and iron oxide particles, and diminishes their moderate antibacterial activity [39].

Figure 8 shows the results of the MH experiments performed on E297 GB cells, using FeHA, Mag and Mag@CaP. E297 was chosen for these assays as the GB cell line because, unlike the standard U87, it is a more recent patient-derived line [29] and it is also more aggressive and more resistant to therapy than the U87, the reason for which its response to the treatment is likely closer to what will be seen clinically. These experiments were performed at the particle concentration of 10 mg/ml; as such, the tests in the absence of the AMF do not replicate, but complement the regular viability experiments performed in the 1–5 mg/ml particle concentration range (Figure 7). At this concentration, FeHA particles were moderately toxic to E297 cells in the absence of the AMF, just like Mag particles, reducing the viability down to 80.5 ± 6.0% and 75.9 ± 7.6%, respectively. Both of these types of particles were significantly more toxic to the cells than Mag@CaP particles, where the iron component is shielded by CaP and cells protected from a direct contact with it.

Figure 8. . Cell viability after the alternating magnetic field treatment.

Viability of human E297 glioblastoma cells challenged with 10 mg/ml of different magnetic nanoparticles for 30 min in a low-intensity alternating magnetic field (300 kHz, 1.16 μT) (blue bars) compared with the controls subjected to no alternating magnetic field (red bars) and to E297 cells treated under the same conditions but involving prior uptake of the nanoparticles for 24 h (green bars). Following the magnetic hyperthermia treatment, the particles were washed off and the cells were allowed to recover for 24 h before the viability assay was performed. Control cells underwent the same treatment as the comparative cell populations, except for their not being challenged with any nanoparticles. Data points are shown as averages (n = 4–8) with error bars representing the standard deviation. Statistically significant difference between sample groups is represented with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.0001. Samples with a significantly reduced cell viability with respect to the identically treated, albeit particle-free control are topped with an asterisk.

FeHA: Iron-doped HA; Mag: Iron oxide; Mag@CaP: Mag nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate.

Interestingly, Mag@CaP nanoparticles at the highest, 10 mg/ml dose imposed lesser cytotoxicity both with and without the AMF than FeHA or Mag, and their toxic response became ‘turned on’ only after they had been uptaken prior to the exposure to the AMF, in which case their toxic effect greatly surpassed that achieved by FeHA or magnetite. Specifically, the viability of E297 following the treatment including the particle uptake and the subsequent 24 h cell recovery dropped down to mere 10.50 ± 0.67%. For FeHA particles, the effect of the AMF coupled to the particle uptake was moderate, but consistent. Thus, the viability reduction by 19.5 ± 6.0% in the absence of the AMF increased by 14.9 ± 9.0% more when cells were treated with the particles and the external field for 30 min and by 42.9% ± 8.0% more when cells were incubated with the particles for 24 h (to allow for the uptake to happen) prior to the AMF exposure. This positive effect of the particle uptake on MH was cell line dependent, as, for example, no effect was observed against OS K7M2 cells under identical treatment conditions with FeHA (Supplementary Figure 4). Interestingly, Mag was not responsive to uptake or the AMF of this intensity. Namely, there was a mild, but statistically insignificant reduction in the viability of the population exposed to the AMF compared with the one not subjected to it and there was a similarly minute and insignificant reduction of the population of cells subjected to the uptake prior to the treatment compared with the one not given sufficient time to internalize the particles (Figure 8).

To confirm the nanoparticle uptake, fluorescent microscopy experiments were performed on E297 and K7M2 cells treated with iron-containing nanoparticles. Images shown in Figure 9 demonstrate excellent uptake of the nanoparticles, particularly by GB cells, but also by OS cells, an effect that supports and explains the MH viability results. Although FeHA nanoparticles mostly exhibited no negative morphological effects on K7M2 and E297 cells when brought into contact with them, regions were present in E297 cultures where this contact did elicit cell necrosis, as evidenced by the nonstriated, granulated cytoskeletal microfilaments and the shrunken, dissipating cell nuclei (Figure 9). Meanwhile, Mag@CaP nanoparticles did not produce any visible effects on cells and they were morphologically indistinguishable from the control (Figure 10). This mild reduction of E297 cell viability caused by the treatment with 10 mg/ml FeHA and no effect by the treatment with Mag@CaP is evident in Figure 8. However, after the 24-h uptake and the switching of the AMF for 30 min, the viable E297 population dramatically decreases over the next 24 h in the Mag@CaP treatment group and gets reduced below 50% of the pretreatment value in the FeHA group (Figure 8).

Figure 9. . Immunofluorescent images of cells in interaction with iron-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles.

Fluorescent optical micrographs of fluorescently stained E297 glioblastoma and K7M2 osteosarcoma cells (cytoskeletal f-actin – phalloidin; nucleus – 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI]) of the negative control and of samples incubated with 10 mg/ml iron-doped hydroxyapatite (FeHA) (green) after 24 h of incubation. White arrows in E297 population denote the regions of intense cell necrosis due to the contact with the nanoparticles.

FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite.

Figure 10. . Immunofluorescent images of cells in interaction with iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate.

Fluorescently stained E297 glioblastoma and K7M2 osteosarcoma cells (cytoskeletal f-actin – phalloidin; nucleus – DAPI) display no adverse effects on their proliferation degree or morphology following the 24-h treatment with 10 mg/ml iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate.

The corresponding flow cytometry analysis, testing for the cell granularity reported in Figure 11, confirmed the nanoparticle uptake; specifically, 44.9 ± 12.0% of the E297 cells incubated with FeHA nanoparticles displayed increased granularity compared with only 1.5 ± 0.3% for the negative control. These values correspond to the percentages of cells uptaking the particles after the 24-h co-incubation (Figure 10). Interestingly, the uptake of Mag@CaP nanoparticles was present, but less prominent than that of FeHA particles, equaling only 17.7 ± 1.6% of the cell population, which was 2.5-times less than the percentage of cells uptaking FeHA. These results confirm the superior uptake propensity of HA, which decreases when the crystallinity of this phase is reduced to the point of amorphousness, as in CaP, let alone combined with Mag.

Figure 11. . Fluorescence activated cell sorting.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) of E297 cells to determine the nanoparticle uptake based on increased granularity in cells following a 24-h incubation with 5 mg/ml of different nanoparticles, as represented by cell populations with an SSC-A profile. (A) Parental E297 cell population with no Mag@CaP particle uptake; (B) E297 cells treated with Mag@CaP particles showing two populations of cells, the parental control and one exhibiting granularity; (C) parental E297 cell population without FeHA particle uptake; (D) E297 cells treated with FeHA particles showing a second cell population with increased granularity along with the parental population. Percentage of cells uptaking Mag@Cap and FeHA nanoparticles compared with the remaining population is shown in (E). Data points are shown as averages (n = 3) with error bars representing the standard deviation. Statistically significant difference between sample groups is represented with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.0001.

FeHA: Iron-doped hydroxyapatite; Mag@CaP: Iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate; SSC-A: Increased side scatter.

Discussion

The addition of iron to calcium phosphates has been a traditional approach to endow a highly biocompatible material that calcium phosphate is with magnetic properties [40]. To create these combinations, two approaches are generally possible: incorporating iron in the ionic form and taking advantage of the exceptional ability of calcium phosphate, particularly HA, to accommodate foreign ions inside its lattice; or using iron in a particulate, typically oxide form under ambient conditions and creating composites. In this study, we characterized these two types of magnetic calcium phosphates, namely FeHA and Mag@CaP, and compared their physicochemical properties as well as efficacy for targeting cancer cells for destruction in and out of the AMF.

Regardless of whether iron was added to calcium phosphate in ionic or particular form, it exhibited a measurable effect on the material structure. Ferrous ions have a smaller ionic radius than calcium ions (75 vs 114 pm) and their substitution leads to lattice contraction and consequent deformation, causing reduced long-range symmetry. Ferric ions, owing to their valence disparity, produce a single calcium vacancy per two Ca2+ → Fe3+ substitutions to compensate for the charge imbalance, leading to defect accumulation and an increase in the lattice strain. As a result, the incorporation of iron in the ionic form into HA, be iron divalent or trivalent, decreases the crystallinity of the material. Indeed, the addition of Fe to HA did not only broaden the diffraction peaks, but it also decreased the (002)/(211) diffraction peak intensity ratio, complying with its role as a structure breaker that reduces the crystalline anisotropy. In turn, the partial conversion of CaP – whose amorphous nature can be hypothesized as the key to explaining its ability to finely coat iron oxide nanoparticles in Mag@CaP – to a crystalline phase in the presence of Mag was observed in both XRD and FTIR analyses, proving that Mag particles act as nucleation promoters, not inhibitors, during the crystallization of CaP, presumably because of the favorable combination of Fe-OH groups forming due to Mag surface hydrolysis and the epitaxial lattice matching between the calcium phosphate crystals and the iron oxide substrate [41].

Solubility experiments showed that doping with a foreign ion, in this case Fe, could stabilize the material and prevent it from acidic degradation in spite of the structure-breaking effect that the ion has on the crystalline symmetry. While the core-shell structure in Mag@CaP completely shields the iron phase from the solution, iron oxide nanoparticles are located on the surface of FeHA rods, where they may exhibit a dissolution-suppressing effect. Moreover, previous studies have shown that iron doping of apatite can decrease its solubility [42], while an additional effect may come from the smaller particle size of HA compared to FeHA, contributing to the somewhat higher solubility of the former material.

Neither of the nanoparticles exhibited a consistent, dose-independent and positive selectivity in inducing toxicity to healthy and cancerous cells in regular culture, without the use of AMF. In fact, the nanoparticles exhibited an overall negative selectivity, with a single exception being CaP at 5 mg/ml. The above point need not be concerning because cancer cells are by their makeup sturdier and more resistant to treatments than the healthy cells, with p53 signaling playing a particularly important role in the promotion of this resilience [43].

The significant difference in effect observed against the two types of GB cells, E297 and U87, suggests that the treatment, as ever in the clinic, especially for brain tumor patients, will be greatly dependent on the tumor pathology and the molecular features of the cell genotype and phenotype [44]. Tangentially, this implies that more detailed studies on interaction between single cells and particles are needed as parts of elaborate in vitro models to make progress in knowledge on these phenomena. Additionally, these results demonstrate that setting up the right dose will be of critical importance for effective cancer targeting. Choosing the right particle composition and structure is thus only one aspect of the effort to derive a potent anticancer treatment and the choice of the dose proves to be equally important. These are, quite possibly, the very same arguments that apply to every nanoparticle treatment per se.

A significantly higher viability of cells subjected to an AMF without being allowed to uptake the MNPs (FeHA and Mag@CaP) than the viability of cells allowed to uptake the nanoparticles before being subjected to the AMF demonstrates the importance of uptake for an effective MH therapy. In the attempt to elucidate the effect of the cell uptake on the treatment efficacy, we chose to make the AMF intensity relatively weak. Whereas a strong field would be expected to reduce the viability of cells treated with the adsorbed and the uptaken nanoparticles to a similarly significant degree, the purpose of the weak field in these experiments was to allow for the difference between the effect of the AMF on the viability of cells with and without the particle uptake to be noticeable.

Alternation of the magnetic field direction produces heat losses in the process of the rapid reorientation of magnetic dipoles and this MH effect can cause the cancer cells to deteriorate and become apoptotic or necrotic. In the case of a low-intensity field, the application of the magnetic stimulus does not generate a macroscopic temperature increase, but rather a localized subcellular temperature rise capable of inducing cell death through a subtler mechanism dubbed as ‘imperceptible’ MH [45,46]. Therefore, the uptake of the nanoparticles by the cells prior to their exposure to a weak AMF can make them more susceptible to the treatment and augment the efficacy of this type of therapy [13].

The morphology of cells immediately after the hyperthermia treatment was not noticeably different than the control. During the treatment, certain, albeit relatively minor percentage of the cells detached from the coverslips, having likely been killed during the treatment. The majority of cells, however, remained adherent and did not show gross morphological changes, as was expected in view of the fact that the stress during the treatment will mostly induce apoptosis, a regulated cell response that depends on highly regulated cell signaling, in which case the cells would not show much morphological changes for many hours or even days. After the 24-h period of recovery, however, the cell death due to the treatment with FeHA and Mag@CaP was obvious, but only if the AFM exposure was preceded with a 24-h incubation period allowing the cells to uptake the nanoparticles.

While both FeHA and Mag@CaP nanoparticles produced a significant reduction in viability in E297 cells that were allowed to internalize the nanoparticles prior to the AMF treatment compared with cells treated without internalization, no effect was detected for Mag nanoparticles. Two essential insights can be drawn from the fact that the toxic response of Mag@CaP is present only after the nanoparticles are being uptaken prior to the AMF exposure: Ms of a nanoparticle need not be in the range of the bulk materials and can be as low as 4 emu/g for the MH treatment to be effective; the positive effect of CaP in Mag@CaP must be due to increased nanoparticle uptake and intracellular localization. Mag nanoparticles by themselves adhere strongly to the outer membrane and are not uptaken well by the cells, but the addition of CaP reverses this trend and endows Mag@CaP with an excellent uptake propensity. CaP, in fact, has been a major nonviral gene delivery carrier for decades thanks to its ability to be effectively uptaken by a range of cells [47]. This essential property of it can be utilized to deliver the magnetic domains into the cell and promote a more effective MH therapy.

FeHA was internalized more abundantly than Mag@CaP by the same cells, which is not surprising given that HA, because of its higher surface energy and a higher potential for interaction with biological molecules, should be uptaken better than CaP. On the other hand, the effect of the uptake on the induction of E297 cell death in the AFM was not as intense for FeHA as for Mag@CaP. The fact that the cells challenged with Mag@CaP were more susceptible to MH than the cells challenged with FeHA (Figure 8) in spite of the greater uptake of FeHA (Figure 11) and the practically indistinguishable Ms for both materials (Figure 5) may be explained by the specificities of dipolar coupling in FeHA and Mag@CaP. For example, rather than referring to a difference in interparticle interactions, it can be assumed that the superimposition of ferromagnetic exchange interaction to Néel relaxation in the transition region between superparamagnetism and ferromagnetism provides a substantial contribution to the AMF energy absorption rate in Mag@CaP and makes it higher than that of FeHA, due to the larger size of MNPs in the former composite than in the latter (i.e., 35–40 nm vs 5–10 nm). A complementary effect by which CaP coating may increase the effect of Mag is through minimized particle–particle contact consequential to dispersing Mag within CaP. Even though Mag particles are superparamagnetic, they do possess finite coercivity; in addition, the AMF, causing them to magnetize, will endow them with a strong cohesive force. This resulting agglomeration can limit the particles to mere surface interaction with the cells, as these larger particulates may be more difficult to uptake and/or transmit heat to the cell to an equally effective degree. Thus, although the addition of the diamagnetic phase diminishes the specific Ms of the material, its protective effect against agglomeration may have positive therapeutic repercussions. Finally, there is the effect of different intracellular fate of FeHA and Mag@CaP: namely, the lysosomal degradation of FeHA will release mostly ionic, MH-inactive Fe species into the cell, while the degradation of the CaP coating in Mag@CaP will leave behind finely dispersed of Mag nanoparticles in the deep interior of the cell, where their propensity to affect the cell in the AMF may be maximized. The slower degradation of HA in the acidic lysosome than that of CaP, however, guarantees that MH-active FeHA nanoparticles will be retained in the cell for sufficient periods of time to produce a significant MH effect following their uptake. MNP ‘impurities’ released from the surface of FeHA particles during their lysosomal degradation may also lead to this augmented MH effect.

To sum up, dose-dependent toxicity experiments showed that larger amounts of Mag@CaP nanoparticles translate to a more intense MH effect, but only if the nanoparticles are uptaken prior to the treatment. In the absence of the uptake, the toxicity effect is greater for both FeHA and Mag than for Mag@CaP. This difference illustrates the immense importance of the nanoparticle uptake by the cells and of precise localization of MNPs for an effective MH treatment. A cell to which the MNP is external would not be as susceptible to the heat produced in the AFM as a cell to which the same MNP is internal. Overall, for both FeHA and Mag@CaP, MH experiments demonstrate a positive synergy achieved by combining amorphous (CaP) or crystalline (HA) calcium phosphate with a magnetic component, regardless of whether the latter has come in an ionic (in FeHA) or nanoparticulate (in Mag@CaP) form.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was the evaluation of the interaction of different GB (E297 and U87) and OS (K7M2) cells with nanoparticles combining calcium phosphates and iron in two different ways: magnetic FeHA and magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate (Mag@CaP). Nanoparticles were synthesized using wet chemistry and characterized using a number of physicochemical measurement techniques, including: FTIR, which demonstrated the intimate interaction between the individual material components; XRD, which showed that iron oxide acts as a nucleation promoter for the crystallization of HA; magnetometry, which showed that both FeHA and Mag@CaP were superparamagnetic and their specific saturation magnetizations were almost identical, 4 and 5 emu/g, respectively; TEM, which was used to visualize the core-shell morphology of Mag@CaP nanoparticles and the needle-shaped morphology of FeHA nanoparticles; TGA, which confirmed the tight physical contact between Mag and CaP, and the sole affinity of the citrate dispersant for CaP; DLS, which confirmed the coating of Mag by CaP; and ICP, which showed the higher solubility of FeHA than Mag@CaP and demonstrated that the addition of Fe suppresses the dissolution of HA in spite of its disruptive effect on the long-range order in the material. Interestingly, the most positive selectivity and targeting potential against cancer cells, specifically GB, was exhibited by the two calcium phosphates: HA and CaP. The addition of Fe ions to HA increased the HLF cell viability, indicating the positive effect of this type of doping on healthy cells, even though FeHA was not more toxic than HA at any dose and against any cancer cell line. In vitro results, in general, were intensely cell and dose dependent and for some cell lines, such as U87, Mag component was more responsible for causing the cancer versus healthy cell selectivity than CaP, but this was reversed for other cell lines. HA and CaP were more prone to exhibit dose dependency than the particles containing iron, be in its ionic (FeHA) or particulate (Mag@CaP) form. FeHA and Mag particles were significantly more toxic to the cells than Mag@CaP particles at the highest dose tested, hinting at the potential safety benefit, if not somewhat diminished treatment efficacy, of protecting Mag with an iron-free CaP layer. Antibacterial effects were tested too, but no activity was detected against Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria in agar assays. Hyperthermia experiments demonstrated that allowing the cancer cells to uptake FeHA or Mag@CaP particles before employing the AMF reduces the cancer cell viability significantly more than running the same experiment on cells in a superficial contact with the nanoparticles. The uptake of the particles was confirmed using immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometry, which showed that 44.9 ± 12.0% of the cells incubated with FeHA nanoparticles and 17.7 ± 1.6% of cells incubated with Mag@CaP displayed increased granularity due to uptake. While the effect was statistically extremely significant for Mag@CaP or FeHA particles, it was negligible for Mag, highlighting the definite benefit of combining iron oxide with calcium phosphates.

Future perspective

Selective effects, such as the ones reported in this study, are essential signs on the roadmap toward improved efficacy of MH and rejuvenation of its clinical prospects. One take-home point of this study is that the intracellular localization of the nanoparticles to a large extent defines the efficacy of a treatment. It ties back to the key point of drug delivery technologies, namely the question, ‘how do we produce better outcomes by delivering the therapeutic agent to the right location, while avoiding its random distribution elsewhere?’ This ultrafine localization can always be improved, focusing onto deeper and finer subcellular compartments and segments of biomolecules, which is exactly where future of the intracellular delivery of MNPs for the MH treatment of cancer lies. If purely inorganic strategies could be conceived of to enable this targeting, along with the targeted, selective effect against cancer versus healthy cells, as was the case in this study, it would be an additional conquest for the materials scientists as developers of these new nanomedical technologies.

Summary points.

Two superparamagnetic calcium phosphates were synthesized using wet chemistry: iron-doped hydroxyapatite (FeHA) and iron oxide nanoparticles coated with amorphous calcium phosphate (Mag@CaP).

Physicochemical characterization confirmed an intimate interaction between the individual components and a higher solubility of FeHA than that of Mag@CaP.

Composite nanoparticles and their individual components were assayed against primary lung fibroblasts, K7M2 murine osteosarcoma cells and E297 and U87 human glioblastoma cells, in and out of the alternate magnetic field (AMF).

The most positive selectivity and targeting potential against cancer cells, specifically glioblastoma, outside the AMF was exhibited by the two diamagnetic calcium phosphates: hydroxyapatite and CaP.

Allowing the cancer cells to uptake Mag@CaP and FeHA nanoparticles before employing the AMF reduced the cell viability more than running the same experiment on cells in a superficial contact with the nanoparticles.

Mag@CaP nanoparticles had no effect on cancer cells at all in the AFM unless they had been incubated with the cells for a prior 24 h and partially uptaken by them.

FeHA was internalized by the cells more effectively than Mag@CaP, but the induction of cancer cell death in the AFM was not as intense for FeHA as for Mag@CaP, with lysosomal degradation specifics, surface energetics, blocked particle–particle interaction and superimposition of exchange interaction to Néel relaxation being elaborated as possible reasons.

Selective effects reported here may be essential signs on the roadmap toward improved efficacy of magnetic hyperthermia and rejuvenation of its clinical prospects.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors acknowledge the European Community for its financial support in the framework of the project CUPIDO (www.cupidoproject.eu) H2020-NMBP-2016 720834 and the US NIH grant R00-DE021416. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Mahmoudi K, Bouras A, Bozec D, Ivkov R, Hadjipanayis C. Magnetic hyperthermia therapy for the treatment of glioblastoma: a review of the therapy’s history, efficacy and application in humans. Int. J. Hyperthermia 34(8), 1316–1328 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedayatnasab Z, Abnisa F, Daud WMAW. Review on magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic nanofluid hyperthermia application. Mater. Des. 123, 174–196 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardoso VF, Francesko A, Ribeiro C, Bañobre-López M, Martins P, Lanceros-Mendez S. Advances in magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7(5), 1700845 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilchrist RK, Medal R, Shorey WD, Hanselman RC, Parrott JC, Taylor CB. Selective inductive heating of lymph nodes. Ann. Surg. 146(4), 596–606 (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A seminal study demonstrating the destruction of cancer tissue in ex vivo, postmortem tissue specimens with the use of magnetic hyperthermia.

- 5.Hervault A, Thanh NTK. Magnetic nanoparticle-based therapeutic agents for thermo-chemotherapy treatment of cancer. Nanoscale 6(20), 11553–11573 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stauffer PR, Cetas TC, Jones RC. Magnetic induction heating of ferromagnetic implants for inducing localized hyperthermia in deep-seated tumors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 31(2), 235–251 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silberman AW, Rand RW, Storm FK, Drury B, Benz ML, Morton DL. Phase I trial of thermochemotherapy for brain malignancy. Cancer 56(1), 48–56 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Phase I clinical trial showing that the temperatures inside brain tumors exceed 42°C without causing any neurological complications, heralding great prospect for this cancer treatment modality, but not foreseeing the decades-long plateau that will follow.

- 8.Roussakow S. The history of hyperthermia rise and decline. Conference Papers Med. 2013, 1–40 (2013). [Google Scholar]; • Broad review of the historic progress, present challenges and future prospects for magnetic hyperthermia.

- 9.Abenojar EC, Wickramasinghe S, Bas-Concepcion J, Samia ACS. Structural effects on the magnetic hyperthermia properties of iron oxide nanoparticles. Prog. Nat. Sci. 26(5), 440–448 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerweck LE. Hyperthermia in cancer therapy: the biological basis and unresolved questions. Cancer Res. 45(8), 3408–3414 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackeyev Y, Mark C, Kumar N, Serda RE. The influence of cell and nanoparticle properties on heating and cell death in a radiofrequency field. Acta Biomater. 53, 619–630 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavla M, Martin B, Jindrich K, Miroslav P. Iron oxide nanoparticles: innovative tool in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7(5), 1700932 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pernal S, Wu VM, Uskokovic V. Hydroxyapatite as a vehicle for the selective effect of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles against human glioblastoma cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(45), 39283–39302 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Comprehensive in vitro study demonstrating that the uptake of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles is greater in normal cells than in cancer cells, underlying a whole new problem for magnetic hyperthermia.

- 14.Gordon RT, Hines JR, Gordon D. Intracellular hyperthermia. A biophysical approach to cancer treatment via intracellular temperature and biophysical alterations. Med. Hypotheses 5(1), 83–102 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A paper introducing the idea of eradicating cancer cells by ‘generating intracellular heat in precise increments’.

- 15.Gómez-Morales J, Iafisco M, Delgado-López JM, Sarda S, Drouet C. Progress on the preparation of nanocrystalline apatites and surface characterization: overview of fundamental and applied aspects. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 59(1), 1–46 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degli Esposti L, Carella F, Adamiano A, Tampieri A, Iafisco M. Calcium phosphate-based nanosystems for advanced targeted nanomedicine. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 44(8), 1223–1238 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boanini E, Gazzano M, Bigi A. Ionic substitutions in calcium phosphates synthesized at low temperature. Acta Biomater. 6(6), 1882–1894 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sneha M, Sundaram NM. Preparation and characterization of an iron oxide-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite for potential bone cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 10, 99–106 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwasaki T, Nakatsuka R, Murase K, Takata H, Nakamura H, Watano S. Simple and rapid synthesis of magnetite/hydroxyapatite composites for hyperthermia treatments via a mechanochemical route. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14(5), 9365–9378 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami S, Hosono T, Jeyadevan B, Kamitakahara M, Ioku K. Hydrothermal synthesis of magnetite/hydroxyapatite composite material for hyperthermia therapy for bone cancer. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn 116(1357), 950–954 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inukai A, Sakamoto N, Aono H. et al. Synthesis and hyperthermia property of hydroxyapatite–ferrite hybrid particles by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 323(7), 965–969 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran N, Webster TJ. Increased osteoblast functions in the presence of hydroxyapatite-coated iron oxide nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 7(3), 1298–1306 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]