Abstract

Background

Two vaccines against Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI) are currently in phase III trials. To enable decision-making on their use in public health programs, national disease epidemiology is necessary.

Objectives

To determine the epidemiology of hospital-acquired CDI (HA-CDI) and community-associated CDI (CA-CDI) in Canada using provincial surveillance data and document discrepancies in CDI-related definitions among provincial surveillance programs.

Methods

Publicly-available CDI provincial surveillance data from 2011 to 2016 that distinguished between HA-CDI and CA-CDI were included and the most common surveillance definitions for each province were used. The HA-, CA-CDI incidence rates and CA-CDI proportions (%) were calculated for each province. Both HA- and CA-CDI incidence rates were examined for trends. Types of disparities were summarized and detailed discrepancies were documented.

Results

Canadian data were analyzed from nine provinces. The HA-CDI rates ranged from 2.1/10,000 to 6.5/10,000 inpatient-days, with a decreasing trend over time. Available data on CA-CDI showed that both rates and proportions have been increasing over time. Discrepancies among provincial surveillance definitions were documented in CDI case classifications, surveillance populations and rate calculations.

Conclusion

In Canada overall, the rate of HA-CDI has been decreasing and the rate of CA-CDI has been increasing, although this calculation was impeded by discrepancies in CDI-related definitions among provincial surveillance programs. Nationally-adopted common definitions for CDI would enable better comparisons of CDI rates between provinces and a calculation of the pan-Canadian burden of illness to support vaccine decision-making.

Keywords: epidemiology, vaccine, C. difficile, surveillance, definitions, burden of illness

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile is the most frequent cause of healthcare-associated infectious diarrhea in Canada and other industrialized countries (1). In the United States, it affects more than 300,000 hospitalized patients yearly (2). Symptoms of C. difficile infection (CDI) range from mild diarrhea to severe life-threatening inflammation of the colon (3). In Canada, many provinces initiated CDI surveillance programs following a dramatic increase in incidence and severity in the early 2000s, and in response to CDI becoming a national notifiable disease in 2009 (4). In parallel, the Canadian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Program (CNISP) network (2), a sentinel network of 67 primarily tertiary teaching hospitals in urban centers, has participated in hospital-acquired and community-associated CDI surveillance (5). Most provinces use hospital-acquired CDI as one of the indicators assessing health system performance and patient safety. The main objective of provincial surveillance programs is to determine the incidence of hospital-acquired CDI and to monitor trends and patterns in CDI over time, in order to prevent and control disease (6–14). However, in 2015, the Canadian Communicable Disease Steering Committee’s Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Task Group identified several surveillance gaps in CDI surveillance activities, most notably gaps in data from community settings (4,15).

Two C. difficile vaccines are currently in phase III trials worldwide (16,17). To enable decision-making on the potential use of these vaccines in public health programs, considering the Erickson-DeWals-Farand analytical framework (18) and methods of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (19) for immunization programs decisions in Canada, national disease epidemiology is a critical factor. Although the Public Health Agency of Canada provides annual national healthcare-associated CDI surveillance reports, the data are primarily derived from large, tertiary acute care hospitals and may not be representative of all hospital types and jurisdictions (5,20). There has never been a study conducted systematically on provincial CDI surveillance programs in Canada. Additionally, since healthcare—and thus hospital-acquired infection—is under provincial/territorial jurisdiction, discrepancies in definitions, surveillance methodologies, available laboratory diagnostics and variation in the validation of surveillance programs may exist, hence rendering inter-provincial/territorial comparison difficult.

The objectives of this study were to determine the epidemiology of hospital-acquired CDI (HA-CDI) and community-associated CDI (CA-CDI) as it pertains to Canada, using provincial surveillance data from 2011 to 2016 and to document discrepancies in CDI-related definitions among the provincial surveillance programs.

Methods

Study population

The study population included fiscal-year C. difficile infection surveillance in Canada from 2011 to 2016 at the provincial/territorial level. All of Canada’s provinces and territories were potential participants in the study. To be included, the jurisdiction needed to have a surveillance system that distinguished between HA-CDI and CA-CDI.

Definitions

The definitions related to CDI have been well-described (6–14). For the purpose of this study, definitions for HA-CDI and CA-CDI used included the most common descriptions shared by the ten provinces (Text box). The HA-CDI and CA-CDI definitions, case classification, population surveilled, denominator definition and sources, and laboratory confirmation requirements were extracted separately from provincial protocols for comparison. Surveillance definitions varied from province to province and type of discrepancies were summarized.

| Definitions Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection (HA-CDI) HA-CDI was defined as: • a primary CDI case in an inpatient, with symptom onset at least 72 hours, or more than three calendar days, after admission to the reporting facility OR • a primary CDI case, with symptom onset in the community or occurring less than 72 hours or less than or equal to three calendar days after admission to the reporting facility, who was discharged from the reporting facility in the four weeks prior to the current hospitalization (6–14) Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection (CA-CDI) CA-CDI was defined as: • a CDI case with symptom onset in the community OR • occurring less than or equal to 72 hours or less than or equal to three calendar days after admission to a healthcare facility, provided that symptom onset was more than four weeks after the patient was discharged from any healthcare facility |

Data collection

Data were extracted from provincial public reports retrieved from the Internet in July 2018. Data missing (i.e. number of HA-CDI cases and total inpatient days for Nova Scotia) were requested via email directly from the provinces (i.e. Nova Scotia’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act) in June/July 2018, with answers received in July 2018. For more specific data on the search strategy, please refer to Appendix A. All data were published or requested through legal access with the consent of the province.

Statistical analysis

When available, HA-CDI incidence rates per 10,000 inpatient-days, pooled HA-CDI incidence rates per 10,000 inpatient days, CA-CDI incidence rates per 100,000 population and CA-CDI proportions (%) were recorded. If no incidence rates existed in the provincial reports, the HA-CDI incidence rates and CA-CDI incidence rates were calculated from available data. Pooled HA-CDI incidence rates for the entire study period were calculated for each province. The CA-CDI proportions were generated for provinces with numbers of CA-CDI cases and total CDI cases available. Both HA-CDI incidence rates and CA-CDI incidence rates were examined for trends.

Pooled HA-CDI incidence rates and HA-CDI incidence rates were generated based on the following formula: (total number of HA-CDI cases/total inpatient days) x 10,000. Other than provinces with available total inpatient-days data used for calculating incidence rates, the denominator of that formula was back-calculated using the following formula: (number of HA-CDI cases/HA-CDI rate) x10,000. Similarly, CA-CDI incidence rates were computed using the following formula: (total number of CA-CDI cases/mid-year population) x 100,000 (mid-year data from July 1). The CA-CDI proportions were calculated using the following formula: total number of CA-CDI/total number of CDI cases reported in the province x 100%.

Results

Based on the inclusion criteria, the study included nine of the 10 provinces and no territories. One province was excluded because its surveillance system did not distinguish between HA-CDI and CA-CDI. The territories were excluded as they did not have existing CDI surveillance programs.

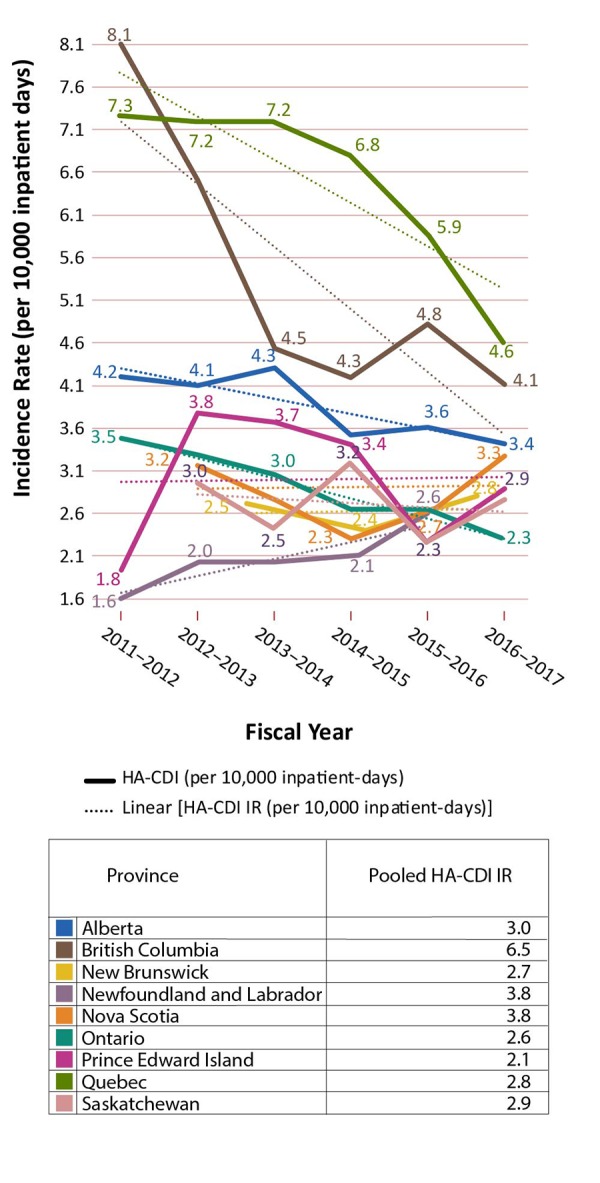

Hospital-acquired incidence rates

The HA-CDI incidence rates by year and province and pooled HA-CDI incidence rates are presented in Table 1 with additional detail in Appendix B. The HA-CDI incidence rates by year indicated that, for almost all provinces, trendlines had been decreasing. In contrast, rates in Newfoundland and Labrador had been increasing, rates in Prince Edward Island had been rising slightly and no obvious trends were seen for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Pooled HA-CDI incidence rates showed that Quebec and British Columbia had relatively higher rates, at 6.5/10,000 and 5.3/10,000 inpatient-days, respectively, followed by Alberta (3.8/10,000 inpatient-days) and Prince Edward Island (3.0/10,000 inpatient-days) (Appendix C: Figure C-1). The other provinces (Ontario, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador) each had rates of less than 3/10,000 inpatient-days.

Table 1. Hospital-acquired C. difficile incidence rates (cases/10,000 inpatient days) by year and pooled incidence rates (cases/10,000 inpatient days).

| Prov. | Fiscal yeara | Pooled rateb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–2012 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | ||

| ABc | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| BCc | 8.1 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 5.3 |

| NBc | - | - | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.8 | - | 2.6 |

| NLc | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.6 | - | 2.1 |

| NSd | - | 3.2c | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| ONb | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| PEb | 1.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| QCb | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 6.5 |

| SKc | - | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; Prov., Province; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; -, empty cells indicate data were unavailable or calculations could not be performed

a The fiscal year started April 1 of that year and ended March 31 of the year after, with the exception of Quebec 2011, when the year started August 14, 2011 and ended August 25, 2012

b Rates were calculated

c Rates were gathered directly from the reports

d For Nova Scotia 2012–2013 fiscal year, only data for the fourth quarter were available

Community-associated incidence rates

Only Alberta, British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Saskatchewan had publicly-accessible CA-CDI data. Alberta was excluded from this part of the study, since it posted only rates and utilized a unit that was different from the one used in this study (per 100,000 population versus per 1,000 admissions).

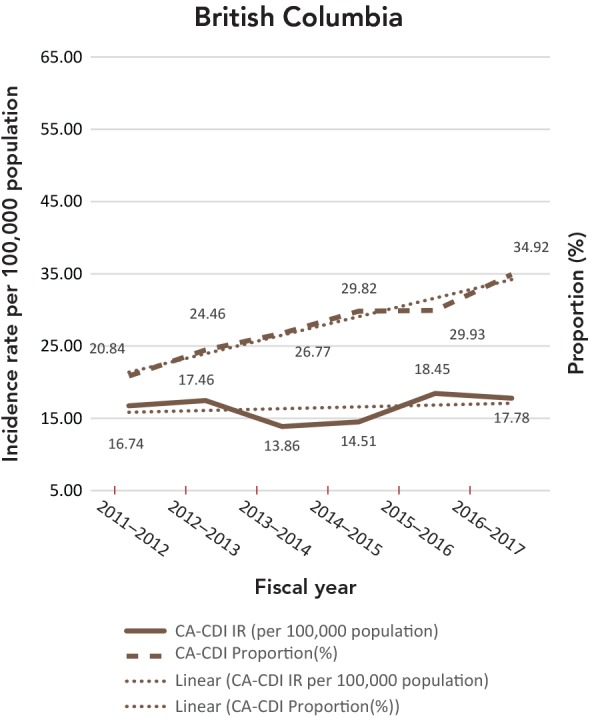

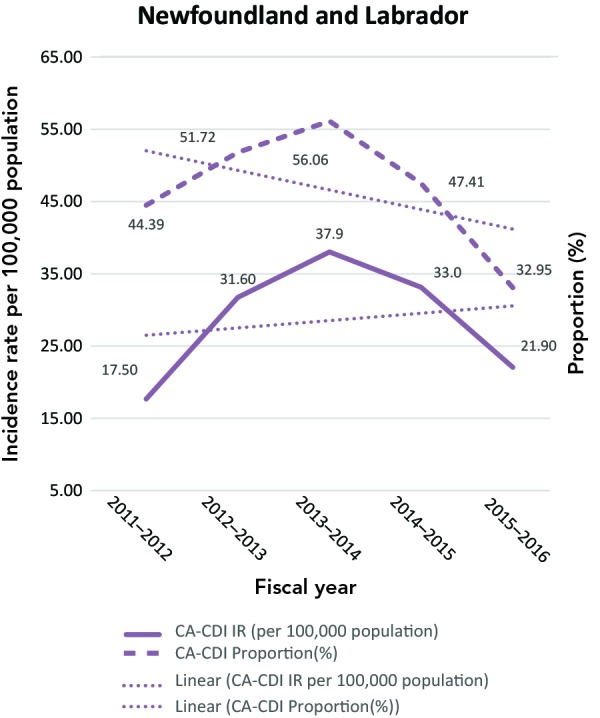

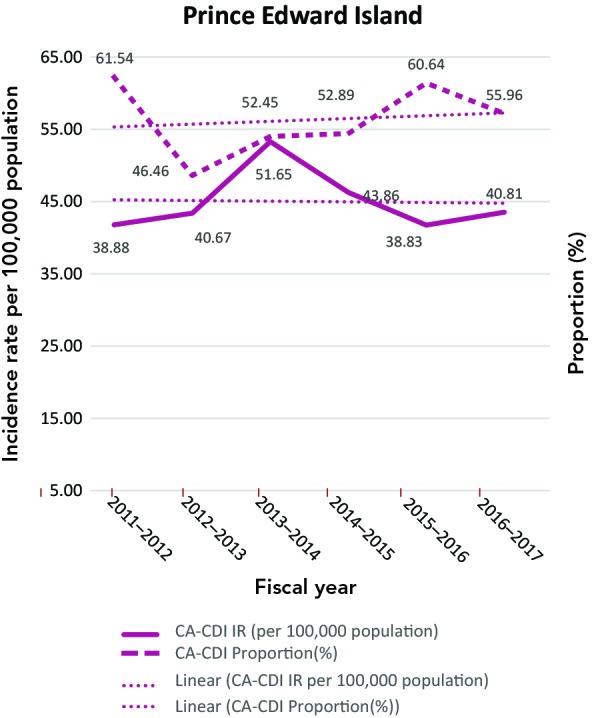

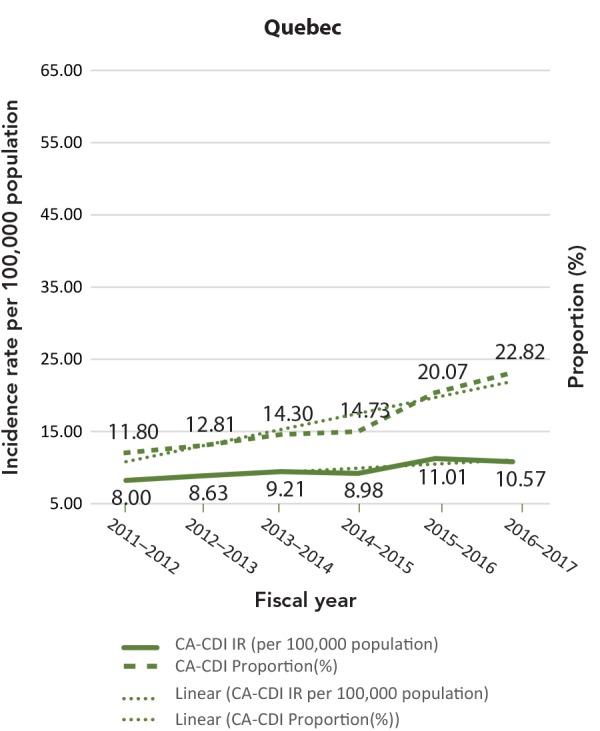

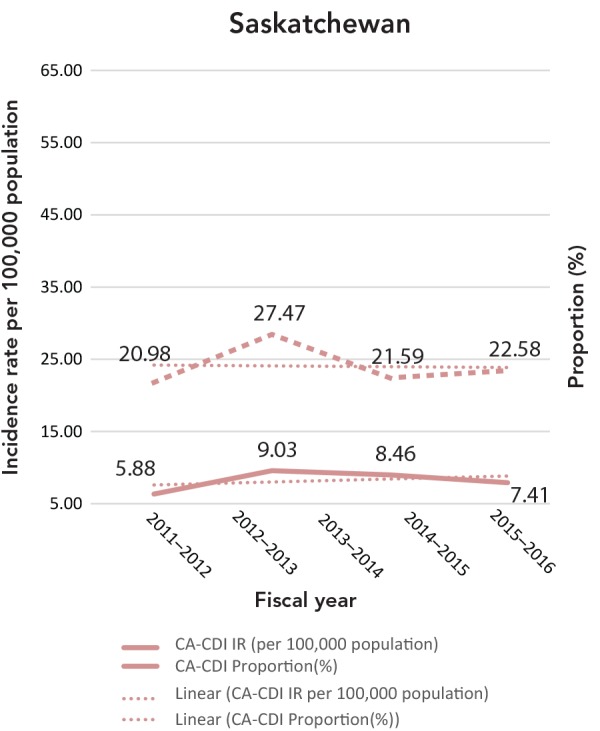

The CA-CDI incidence rates and CA-CDI proportions for provinces are presented in Table 2 with additional detail in Appendix B. In contrast to the HA-CDI incidence rates trends, the CA-CDI incidence rates of all five provinces examined (with the exception of Prince Edward Island) increased (Appendix C: Figure C-2). For Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island, there were marked increases in CA-CDI incidence rates from 2012–2013 to 2014–2015. The same trend was also seen for CA-CDI proportions in British Columbia and Quebec. Even though the CA-CDI proportions in Newfoundland and Labrador were declining over the time period of the study, and the proportion seemed to be increasing in Prince Edward Island, the overall CA-CDI case counts in both provinces still represented a large portion of the total CDI cases reported.

Table 2. Community-associated C. difficile incidence rates (cases/100,000 population) and proportions (%) by year.

| Province | Fiscal yeara,b | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–2012 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | |||||||

| Rate | % | Rate | % | Rate | % | Rate | % | Rate | % | Rate | % | |

| BC | 16.74 | 20.84 | 17.46 | 24.46 | 13.86 | 26.77 | 14.51 | 29.82 | 18.45 | 29.93 | 17.78 | 34.92 |

| NLc | 17.50 | 44.39 | 31.60 | 51.72 | 37.90 | 56.06 | 33.00 | 47.41 | 21.90 | 32.95 | - | - |

| PE | 38.88 | 61.54 | 40.67 | 46.46 | 51.65 | 52.45 | 43.86 | 52.89 | 38.83 | 60.64 | 40.81 | 55.96 |

| QC | 8.00 | 11.80 | 8.63 | 12.81 | 9.21 | 14.30 | 8.98 | 14.73 | 11.01 | 20.07 | 10.57 | 22.82 |

| SK | - | - | 5.88 | 20.98 | 9.03 | 27.47 | 8.46 | 21.59 | 7.41 | 22.58 | - | - |

Abbreviations: BC, British Columbia; C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; -, data unavailable

a Refer to Appendix D for details on rates calculation

b Fiscal years started April 1 of that year and ended March 31 of the year after, with the exception of Quebec 2011, when the year started August 14, 2011 and ended August 25, 2012

c Rates were collected directly from the NL provincial reports

Discrepancies

In the process of data collation and analysis, discrepancies among provincial surveillance definitions of CDI case classification, surveillance populations and rate calculation were detected, which impeded comparison of CDI rates between provinces. The fundamental issue was that each province defined and complied with its own protocol, leading to highly varied numerators (number of CDI cases) and denominators (total inpatient-days). A summary of discrepancies with examples are shown in Table 3. For a more detailed description of the different definitions by provincial surveillance programs, refer to Appendix D. We were unable to use the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Management Information System (MIS) database to estimate the denominators due to the differences in total inpatient days between CIHI and provincial surveillance programs. The differences between the data in the CIHI MIS database and denominators adopted by provinces varied plus or minus 5% to 10%. We were unable to match denominators that fit the definitions of provinces from the CIHI database. For detailed differences between denominators estimated from the CIHI MIS database and those used by provinces, and the calculations used to extract the denominators, please refer to Appendix B.

Table 3. Surveillance discrepancies and examples.

| Discrepancy | Examples (6–14) |

|---|---|

| Population under surveillance | The population under surveillance in British Columbia is defined as “inpatients aged one year or older and admitted to acute care facilities”, while some provinces monitor “any patient with a laboratory-confirmed CDI in the province”. Quebec excludes from surveillance patients in long-term care facilities. Only cases admitted to acute care hospital, from long-term care would be included; it is not clear if the same is done everywhere. |

| Classification of cases | While some of the provinces only report hospital-acquired CDI or only monitor new cases, some classify CDI cases into more refined categories: the category of “related to reporting facility” is further stratified into “related to current/previous hospitalization”; “another facility” is stratified into “long-term/ambulatory care and non-reporting”; and also, “new” and “recurrent” cases are documented separately. All HA-CDI cases might be classified into a single category or could be separated in two: acute care facility-acquired or long-term care facility-acquired. CA-CDI surveillance: Quebec only reports hospitalized cases; it is unclear what is done elsewhere. |

| Definition for the cases classifications | Even though the same categories of CDI cases were monitored, they might have different denominators and case definitions. For example, most provinces define HA-CDI as symptoms occurring more than 72 hours after admission, while Manitoba defines HA-CDI as 48 hours after admission. |

| Denominators used for calculating the rates | In some jurisdictions, patients less than one year of age (or a proxy of that) and/or psychiatric patients were excluded. Meanwhile, some provinces use the total number of inpatient-days regardless of age or area of care. In some instances, the denominator was estimated from other provincial data sources and might be adjusted to fit CDI rate reporting. |

| Denominators used by the provinces and CIHI MIS database | Unable to generate the denominators used by the provinces using the data available in CIHI MIS database. Some provinces used denominators that were higher than the total inpatient-days showed in CIHI MIS database. |

Abbreviations: C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CA-CDI, community-associated C. difficile infection; CDI, C. difficile infection; CIHI MIS, Canadian Institute for Health Information management information system; HA-CDI, hospital-acquired C. difficile infection

Discussion

From 2011 to 2016, the HA-CDI incidence rates in most provinces decreased, which is consistent with the trend reported by the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System and a study based on the CNISP network (21,22). This reduction in rates might be attributed to infection prevention and control interventions (e.g. hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, patient-dedicated toilets and single-patient rooms), antibiotic stewardship and increased CDI awareness. The reduction in the proportion of NAP1 isolates (22), which has been the predominant strain in Canada associated with increasing rate of severe HA-CDI, may also have played an important role.

On the other hand, despite the possibility of an actual increase in CDI cases, the increased incidence rates could be partly explained by the evolution of circulating strains, which might lead to increased toxigenic potential and survival of the bacteria, or to improvements in surveillance and reporting in the province. Notwithstanding the slightly increasing trend in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, there were only three years of data available for New Brunswick and only the fourth quarter of 2011–2012 fiscal year data available for Nova Scotia, decreasing our power to conclude on trends of HA-CDI incidence rate in these two provinces.

Even though most CA-CDI cases were reported in admitted patients, trends, not absolute rates, were studied in this article. Therefore, choosing the provincial population or admissions as the denominator had only a minor impact on the results. The five provinces included in the analysis of CA-CDI incidence rates showed a slight, increasing trend. Of the nine provinces, almost all focused only on HA-CDI. However, the observation of these trends in HA-CDI indicated the importance of also monitoring and analyzing CA-CDI in future surveillance activities. Improved surveillance and reporting from the community may explain these trends. Moreover, the mutual effect of decreasing numbers of HA-CDI cases, growing numbers of CA-CDI cases, and increased use of nucleic acid amplification testing may also explain the observed trends. The decrease in HA-CDI cases may results in an increase in the proportion of CA-CDI cases, even though the overall numbers (HA-CDI plus CA-CDI cases) remain stable, while the increased testing could contribute to the detection of more CA-CDI cases, which were not tested for in the past. In Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island, CA-CDI cases still accounted for a relatively high percentage of all CDI cases reported.

The introduction of more sensitive laboratory testing methods, such as polymerase chain reaction, which detects the toxigenic potential but not the actual toxin production, has been associated with increasing numbers of positive tests and earlier detection compared with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (23,24). Currently, although all the provinces required clinical validation for the identification of CDI cases, the test methods used for this validation varied. Moreover, laboratory tests and protocols have changed over the years, and the impact of these changes on the accuracy of CDI rates is difficult to assess.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to consider. Given the shortage of data, we were limited in the analyses that could be performed. Optimally, comparisons between the provinces and stratified analyses, such as incidence rates by age strata, underlying medical conditions and sex, are performed to determine high-risk populations and to provide useful information for cost-effective analyses that could support future CDI vaccine decision-making processes. Unfortunately, these comparisons and analyses could not be performed fully due to the tremendous disparities among the current provincial surveillance systems (Appendix D).

Another limitation was the discrepancy in the denominators (total inpatient-days) used to calculate HA-CDI rates; discrepancies among the provinces and also between the provinces and the CIHI MIS database. The CIHI database was initially considered for providing a relatively accurate estimation of total inpatient-days. This was because these data were reported on the basis of the fiscal year and are representative of the inpatient population during that year. However, it was found that denominators used by the provinces to calculate their provincial CDI rates were different from the denominators in the CIHI MI database. Furthermore, later comparisons showed a divergence between CIHI data and CNISP denominators. One of the reasons for this difference is that the definitions for denominators derived from the CIHI database did not match those used by either the provinces or CNISP. This suggested that total inpatient-days reported to CIHI and those used for provincial CDI rate calculations were derived from different reporting systems. The target population contributing to the total inpatient-days might vary as well. Because it was not clear how the provinces generated the total inpatient-days, these discrepancies cannot be fully explained. Further research and collaboration is needed to identify the cause of and to solve this discrepancy.

It should also be noted that the data retrieved from provinces through this analysis did not include laboratory-linked strain data for CDI cases. This is a major limitation and prevents the monitoring of ecological trends over time with varied CDI strain types.

Although two potential vaccines are currently undergoing clinical trials, it is not yet known how broadly protective these candidate vaccines will be against the various C. difficile strains or the potential mutants escaped from being detected by traditional strategy. The CNISP has already revealed important trends in virulent strains and antimicrobial resistance (5,22). However, as previously discussed, CNISP is limited to data primarily from a small sample of large, tertiary acute care hospitals across Canada and thus does not provide a complete picture.

Missing data were an important limitation in our study. Only Quebec provided data of total inpatient-days that met the definition of their CDI surveillance protocol. For the other provinces, although some total inpatient-days data might have appeared in the provincial reports, none matched those used to calculate HA-CDI rates. Although, as demonstrated in this paper, denominators can be estimated by back-calculation, this erodes the reliability and accuracy of data presented.

Next steps

There is a fundamental need for a nationally-adopted CDI surveillance protocol. This type of surveillance would be the single most important way to address the many discrepancies between provinces, arising from highly varied data—numerators (number of CDI cases), denominators (total inpatient-days) and different definitions for populations under surveillance—that make incidence rates difficult to compare and interpret.

To provide national-level epidemiological data to support decision-makers in their recommendations for the implementation of a potential CDI vaccine program, several key elements are needed. First, demographically-stratified incidence rates, including delineation by age and sex, would be useful to determine whether certain at-risk groups would benefit more from the vaccine. A study conducted in Spain (22,25) showed that CDI evolves differently by sex and age group. Second, as mentioned in the CNISP Summary Report (2) and as shown in our study, recurrent and CA-CDI should be monitored to increase the understanding of the burden, risk factors and outcomes of such infections in Canada. Third, the use of a common, nationally-adopted definition for CDI, CDI categories and total inpatient-days is critical; the CNISP CDI case definition (26) could be adopted for this purpose, with standardized data collected and reported. Fourth, a quality assessment system is needed to ensure quality of reported data. Fifth, CIHI could be an ideal partner to provide data for total inpatient-days, given its already well-established data gathering system from provinces. The CIHI is able to provide the general total inpatient-days that fit the selected definition, allowing for validation of provincial data, and could be an excellent source for stratified inpatient-days. Finally, the ideal solution would be a national online reporting system that includes universal case definitions, and all hospitals across Canada could provide standardized and comparable data that would be accessed and reported via an online platform, allowing for local, regional, provincial and national comparisons. This would not only simplify the study of the epidemiology of different diseases at different levels and make it more feasible to gather case characteristics to gain a complete view of the disease, but it would provide better control of the overall quality of the information as well. In our interconnected open-data era, this would meet the heightened expectation of timely and publicly-accessible surveillance data. One way to do this would be by expanding CNISP, the Public Health Agency of Canada’s sentinel surveillance program that uses a data entry platform on the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence (CNPHI), but there may be other equally valid means of collecting CDI surveillance data.

Conclusion

In Canada, the rate of HA-CDI has generally been decreasing but the rate of CA-CDI is increasing. There are important discrepancies in CDI-related definitions among provincial surveillance programs that impede comparisons of CDI rates between provinces, and calculating a pan-Canadian burden of illness to support vaccine program decision-making.

Acknowledgements

We thank A MacLaurin (senior program manager, Canadian Patient Safety Institute), C Couris (manager, Indicator Research and Development at Canadian Institute for Health Information), K Allain, B Jenkins, J Dell and the Department of Internal Services in Access and Privacy (Nova Scotia Health Authority), J Johnstone (Public Health Ontario), M Ramprashad and J Noronha (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care), J Ellison and IPC Surveillance & Standards team (Alberta Health Services), J Wei (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living) and Saskatchewan Manager Information Services—all of whom provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research. We would also like to thank R Galioto, Executive Director for the Association for Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada and G Hansen, Executive Director for Infection Prevention and Control Canada for their support on the project.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data searching strategy

Appendix A: Data searching strategy

This document summarizes the sources of data used in the study and additional sources of provincial Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI) surveillance information for further study. For those not separately indicating the origin of the data used in the study, the data are all derived from the reports mentioned below.

Alberta

• Number of hospital-acquired CDI (HA-CDI) cases, incidence rate of HA-CDI and total inpatient days:

Requested via Alberta Research Facilitation (email: Research.Facilitation@ahs.ca)

• IPC Annual Report to Alberta Health (2016):

www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/healthinfo/ipc/hi-ipc-provincial-surveillance.pdf

• CDI Surveillance Protocol:

www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/healthinfo/ipc/hi-ipc-sr-cdi-protocol.pdf

• Quarterly Performance Report:

British Columbia

• CDI Surveillance Protocol, Quarterly Report and Annual Report:

www.picnet.ca/surveillance/cdi/

Only the most recent reports were listed on the website: to access the archived reports, change the date in the URL of the latest report

• Population Statistics:

Manitoba

• Manitoba Monthly Surveillance Reports:

www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/episummary/index.html

• Manitoba Annual Summary of Communicable Diseases:

www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/cds/index.html

• CDI Surveillance Protocol

New Brunswick

• Quarterly Healthcare Associated Infections Surveillance Report:

www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/cdc/content/HAI.html

• No CDI Surveillance Protocol was available. Only the most recent report was listed on the website: to access the archived reports, change the date in the URL of the latest report

• New Brunswick Communicable Disease Annual Report:

www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/for_healthprofessionals/cdc.html

Newfoundland and Labrador

• Healthcare-associated Infections Annual report:

www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/informationandsurveillance.html#currentyear

• CDI Surveillance Protocol:

www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/CDI_surveillance_protocol_final.pdf

Nova Scotia

• Number of cases of HA-CDI and total inpatient days:

requested via Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (email: FOIPOP@nshealth.ca)

• CDI (New cases of healthcare-associated C. difficile infection that occur in the hospital)

Quarterly Performance and CDI Surveillance Protocol:

https://novascotia.ca/dhw/hsq/public-reporting/c-difficile-data-trending.asp

• Annual Notifiable Disease Surveillance Report (overall CDI cases and incidence): https://novascotia.ca/dhw/populationhealth/

Ontario

• Number of HA-CDI cases: “clostridium-difficile-infection.xls” document obtained from

www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/system-performance/clostridium-difficile-infection.xls

by searching “Clostridium difficile” in Public Health Ontario official website

www.publichealthontario.ca/en/Pages/default.aspx

Total inpatient days:

Requested via @MOH-G-Patient Safety (email: PatientSafety@ontario.ca)

• C. Difficile Infections in Hospital Patients Performance Quarterly Report:

• CDI Surveillance Guideline:

Prince Edward Island

• Prince Edward Island (PE) Infection Prevention and Control Program Surveillance Data Summary (only reports for 2015 and 2016 were available):

www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/topic/reports-and-trends

• PE Infection Prevention and Control Program Surveillance Data Summary (2014):

www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/cpho_ipc_ar2014.pdf

• PE Infection Prevention and Control Program Report (2011):

www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/DHW_IPC2011.pdf

• CDI Surveillance Guideline:

www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/c_diff_infection_guideline.pdf

• Population Statistics:

https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/pt_pop_rep_1.pdf

Quebec

• Diarrhées à Clostridium difficile (DACD) Annual Surveillance Report and Protocol:

www.inspq.qc.ca/infections-nosocomiales/spin/dacd

• Population Statistics:

www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/population-demographie/structure/qc_1971-20xx.htm

Saskatchewan

• CDI Surveillance Annual Report and Protocol:

www.ehealthsask.ca/services/resources/Pages/Communicable-Disease.aspx

• Population Statistics:

www.saskatchewan.ca/government/government-data/bureau-of-statistics/population-and-census

Appendix B: Hospital-acquired and community-associated Clostridioides difficile infections: definitions, case classification in provincial reports, population surveilled, denominator definition and sources and laboratory confirmation requirements

Table. B-1: Definitions of hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile infections.

| Province | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alberta (1) | For a primary, symptomatic case, the patient’s symptom meeting CDI case definition occur in a hospital more than or equal to 72 hours after admission OR For a primary, insufficient info case, the positive C. difficile test date more than or equal to 72 hours after admission OR A patient is readmitted to an Alberta Health Services/Covenant Health facility under surveillance within four weeks of discharge from a facility where the admission was more than or equal to 72 hours AND The patient’s symptoms meeting CDI case definition occur in a hospital within 72 hours of readmission |

| British Columbia (2) | A CDI case occurring more than 72 hours or more than three calendar days (the day of admission counted as the first calendar day, the same hereinafter) after admission to an acute care facility cases identified on or after the fourth calendar day of hospitalization will be classified as HCA) OR A CDI case with symptom onset in the community or occurring fewer than or equal to 72 hours or fewer than or equal to three calendar days after admission to an acute care facility, provided that the patient was admitted to a healthcare facility (including acute care and long-term care) for a period of more than or equal to 24 hours or at least overnight stay in the past four weeks before onset of CDI symptoms |

| Manitoba (3) | Patient’s initial symptoms occur more than 48 hours post-admission to a healthcare facility OR A patient, who has been discharged from the current healthcare facility within the preceding four weeks, who develops an onset of C. difficile-acquired disease that requires readmission to the same healthcare facility |

| New Brunswick (4) | Same as Canadian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Program 2014 definition. Cannot be found online |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (5) | A case in which symptoms occur at least 72 hours or more after the current admission OR Symptoms occur in a patient who has been hospitalized at a hospital and discharged within the previous four weeks |

| Nova Scotia (6) | The patient’s CDI symptoms occur in your healthcare facility three or more days after admission, with day of admission being day one OR The patient’s CDI symptoms occur less than three days after admission and are seen in a patient who had been hospitalized at a healthcare facility and discharged within the previous four weeks |

| Ontario (7) | Onset of symptoms more than 72 hours after admission OR The infection was present at the time of admission but was related to a previous admission to the same facility within the last four weeks and the case has not had Clostridium difficile-associated disease in the past eight weeks |

| Prince Edward Island (8) | Symptoms were not present on admission (onset of symptoms more than 72 hours after admission) and there was no admission to an acute care or long term care facility in the last four weeks (if the patient/resident was in another facility in the past four weeks, the case may be attributed to that facility) Not mentioned in the guideline or other reports |

| Quebec (9) | Patients hospitalized on a short-term care unit of the reporting facility AND diagnosed with CDAD three days and more (so starting on D4) after admission (admission=D1) OR Long-term or psychiatric patients hospitalized in short-term units three days or more after admission (D4) * Excluded: patients hospitalized on registered psychiatric, neonatal and children's complete long-term care units OR Patients hospitalized or not in the reporting facility and diagnosed with CDAD up to four weeks after their release from a short-term care unit of the reporting facility whatever the length of hospitalization OR Patients transferred to a residential and long-term care centre or private residence providing care and diagnosed with CDAD up to four weeks after their release from a short-term care unit of the reporting facility whatever the length of hospitalization whether they are re-admitted to the reporting facility or not OR Patients transferred to a general hospital specialty clinic (other participating short-term care centre) or rehabilitation centre, participating in monitoring or not, and diagnosed with CDAD less than three days (so D1, D2 or D3) after their admission/registration in emergency (D1) * Excluded: patients transferred to a short-term care centre or rehabilitation centre, participating in monitoring or not, and diagnosed with CDAD three days and more after admission (so starting on D4) after their transfers (these cases will then be attributed to the centre to which each patient was transferred) |

| Saskatchewan (10) | The patient’s CDI symptoms began more than or equal to three days after admission to the reporting healthcare facility OR The patient’s symptoms began in the community or fewer than three days after admission to the reporting facility AND The patient was admitted to the reporting facility for a period of more than or equal to three days in the past four weeks |

Abbreviations: C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CDAD, Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infections; HCA, healthcare-associated

Note: Bolded text reflect subtle differences between provinces

Table. B-2: Provincial definitions of community-associated Clostridioides difficile infection.

| Province | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alberta (1) | Any primary CDI case not meeting the criteria for the hospital-acquired or healthcare-associated will be considered community acquired |

| British Columbia (2) | A CDI case with symptom onset in the community or occurring within fewer than or equal to 72 hours or fewer than or equal to three calendar days after admission to an acute care facility, provided that the patient was not admitted to any healthcare facility (including acute care and long-term care) for a period of more than or equal to 24 hours or at least overnight stay in the past four weeks before onset of CDI symptoms |

| Manitoba (3) | Patient does not meet either nosocomial case definition |

| New Brunswick | n/a |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (5) | A case with symptom onset in the community or three calendar days or less after admission to a healthcare facility, provided that symptoms onset was more than four weeks after the last discharge from a healthcare facility |

| Nova Scotia | n/a |

| Ontario | n/a |

| Prince Edward Island (8) | Symptom onset in the community or fewer than 72 hours after being admitted to an acute care or long term care facility, and symptom onset was more than four weeks post-discharge from an acute care/long term care facility Not mentioned in the guideline or other reports |

| Quebec (9) | Patients hospitalized on a short-term care unit of the reporting facility and diagnosed with CDAD less than three days (so D1, D2 or D3) after admission/registration in emergency and having no connection with the care environment (hospital, residential centre or ambulatory services included in categories 1b, 1c, 1d and 2) within the preceding four weeks (28 days) |

| Saskatchewan (10) | CDI symptoms began in the community or fewer than three days after admission to a healthcare facility, provided that symptom onset was more than four weeks after the patient was discharged from any healthcare facility CA-CDI cases do NOT need to be entered into the CDI Electronic Report Form—might underestimate the number of CA-CDI cases |

Abbreviations: C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CA-CDI, community-associated CDI; CDAD, Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infections; n/a, data not available

Note: Bolded text reflect subtle differences between provinces

Table. B-3: Case Classification in the regular reports.

| Province | Case classification |

|---|---|

| Alberta (11) | Hospital-acquired infections |

| British Columbia (12) | HA-CDI • HCA with reporting facility, new cases • HCA with another facility, new cases • HCA with reporting facility, relapse • HCA with another facility, relapse Community-associated CDI Unknown |

| Manitoba (13) | Total CDI cases |

| New Brunswick (4) | CDI attributed to reporting hospital (definition see HA-CDI) CDI attributed to reporting hospital but does not meet the criteria of the first classification CDI attributed to another acute care facility CDI attributed to long term care or non-acute care facility Unknown |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (14) | CDI in acute care facilities CDI in long term care facilities Healthcare-associated (not hospitalized cases) CDI Community-associated CDI |

| Nova Scotia (15) | Healthcare-associated CDI in the reporting facility * Not mentioned new/recurrent case |

| Ontario (16) | New hospital acquired CDI in the reporting facility |

| Prince Edward Island (17) | New cases of healthcare-associated CDI in long term care, acute care and other, respectively New cases of community-associated CDI Other |

| Quebec (18) | Case associated with current hospitalization in the reporting facility Case associated with previous hospitalization in the reporting facility Case associated with ambulatory care of the reporting facility Case associated with long-term care unit of the reporting facility Case associated with a stay in a non-reporting facility Case of community origin, not associated with care environment |

| Saskatchewan (19) | CA-CDI (2012–2015) HA-CDI • Community-onset HA-CDI and Healthcare-onset HA-CDI • Recurrent HA-CDI and Primary HA-CDI (primary acute HA-CDI and primary long term care HA-CDI) |

Abbreviations: C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CA-CDI, community-associated CDI; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; HA-CDI, hospital-acquired CDI; HCA, healthcare-associated

Table. B-4: Provincial Surveillance—Population Surveilled.

| Province | Population |

|---|---|

| Alberta (1) | All individuals admitted to Alberta Health Services and Covenant Health acute and acute tertiary rehabilitation care facilities, where inpatient care is provided 24 hours/day, seven days a week, who are more than or equal to one year of age |

| British Columbia (2) | Inpatient one year or older admitted to acute care facilities Inclusion criteria: • Patients admitted to the Emergency Department awaiting placement • Patients in alternative level of care bed • Patients in labour and delivery beds Exclusion criteria: • Outpatient visits to clinics in the acute care facility • Emergency room patients not admitted to an acute care inpatient ward • Patients in extended care beds or in mental health beds housed in the acute care facilities • Inpatient younger than one year of age In the case that mental health inpatients are NOT excluded from the population under surveillance for CDI in your health authority, the cases of CDI identified among mental health inpatients should be collected and included in your CDI data submission |

| Manitoba (3) | Patients, residents and clients |

| New Brunswick (4) | Patients who have been hospitalized (no protocol) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (5) | Any patient with laboratory-confirmed CDIs in the province Not specified in the protocol. |

| Nova Scotia (6) | To be included in the surveillance, a patient with healthcare-associated CDI must be: • One year of age or older • Admitted to the acute care hospital Long-term care and awaiting-placement patient on acute-care wards are to be included. Patients admitted to hospital, but who remain in the Emergency Department once admitted, are included. Patients who are discharged after the date of the positive culture but before the results are available are included Exclusion criteria • Emergency, mental health units, psychiatric or withdrawal management units and ambulatory clinic or other outpatient cases. Patients who were discharged in the previous four weeks and return to the emergency department or outpatient clinic with a new onset of CDI, but are not readmitted, are NOT included |

| Ontario (7) | Total number of new nosocomial (i.e. hospital acquired) CDI cases Inclusions: • All publicly-funded hospitals • Inpatient beds • Laboratory-confirmed CDI cases Exclusion criteria: • Patients younger than one year of age |

| Prince Edward Island (17) | All cases of CDI in Health Prince Edward Island facilities Not specified in the guideline |

| Quebec (9) | For each administrative period for each facility must be included in monitoring for all categories of CDAD cases meeting the definition: • all hospitalized patients with a CDAD diagnosis (see exclusions) • all hospitalized patients with a CDAD diagnosis more than eight weeks after the end of treatment of a previous CDAD episode • all patients not hospitalized at the time of CDAD diagnosis but who were hospitalized in the reporting facility during the four weeks preceding the diagnosis Excluded from monitoring: • all non-hospitalized patients with a CDAD diagnosis AND who have not been hospitalized in the reporting facility during the four weeks before the diagnosis; a CDAD recurrence is defined as the reappearance of symptoms less than eight weeks after the end of treatment for the last episode diagnosed (with positive lab test or by physician); a repeat diagnosis does not necessarily require a new positive lab test; a case recurring more than eight weeks after the end of treatment for the last episode is considered a new case, and that case should be included in monitoring Note: the system automatically excludes patients in [hotel] ([measure] 37), neonatal and children's care (measure 38) and psychiatric beds (measure 53); patients in residential and long-term care centre beds (mission/class 400) are also excluded |

| Saskatchewan (10) | Only patients or residents admitted into a hospital or long-term care facility at the time the CDI diagnosis is made, OR who had been acute care inpatients/long-term care residents in the four weeks prior to diagnosis are included for surveillance Inclusion criteria • One year of age and older • Admitted to an acute care unit (this includes patients awaiting placement on acute care units, patients admitted to your facility but who remain in the emergency room once admitted, 'outpatients' in ER who have been there for more than three days, and patients who are discharged after the date of diagnosis, but before the laboratory results are received) • In a mental health inpatient ward/unit • Residents in long-term care facilities • Patients who were discharged from a healthcare facility in the previous four weeks and return to an outpatient unit/facility with a new onset of CDI Outpatient units may include, but are not limited to, the following: • Cancer centre • Dialysis unit • Emergency room (not admitted) • Physician clinic or office |

Abbreviations: C. difficile, Clostridioides difficile; CDAD, Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection

Table. B-5: Definition and source of denominators used to calculate rates.

| Province | Denominator |

|---|---|

| Alberta (1) | The data are abstracted from Admission, Discharge and Transfer Data using a standard methodology and is provided to Infection Prevention and Control. Inpatient admissions and inpatient days cannot be excluded for inpatients younger than one year of age; therefore, as a proxy, the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit denominators and newborn denominators in maternal or labour and delivery units are excluded |

| British Columbia (2) | Total number of inpatient days collected from the patient information systems by the respective health authority |

| Manitoba (13) | Denominator used is total population, not total inpatient days |

| New Brunswick (4) | Days spent in a hospital for all patients, regardless of medical condition Derived from the report, no protocol available |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Not mentioned in the guideline or reports |

| Nova Scotia (6) | The total number of days that patients are in hospital (“patient days”) on the units on which surveillance for CDI is conducted. This is collected on a quarterly basis. Excluded from “patient days” are dedicated long-term care, mental health/psychiatric or withdrawal management units, and patients younger than one year of age. Denominator data should be collected using the health information systems of the respective authority |

| Ontario (7) | Total number of inpatient days Inclusions: • All publicly funded hospitals • Inpatient beds Exclusions: • Patients younger than one year of age |

| Prince Edward Island | Not mentioned in the guideline or reports |

| Quebec (9) | Based on the number of patients and their length of stay in the facility or care unit |

| Saskatchewan (10) | The appropriate denominator used to determine CDI rates is ‘patient/resident days’. Denominator data (estimated from other provincial data sources) is provided to regional Infection Control Professionals (ICPs). The ICPs may change these numbers if they are not reflective of the current situation (e.g. due to bed closures), or if the ICPs are able to refine the estimate provided. Some ICPs have submitted exact denominator data for their region and others have allowed the estimated provincial data to be used. However, given that the denominator is based on 10,000 patient days, the discrepancy between the actual denominator and the estimate would have to be fairly large to make a significant difference in the rate |

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; ICP, Infection Control Professionals

Note: Bolded text reflect subtle differences between provinces

Table. B-6: Laboratory confirmation requirements.

| Province | Laboratory confirmation requirements |

|---|---|

| Alberta (11) | Laboratory-confirmed positive Clostridium difficile test (by polymerase chain reaction or toxin assay) |

| British Columbia (12) | The presence of C. difficile toxin A and/or B (positive toxin, or culture with evidence of toxin production, or detection of toxin genes) |

| Manitoba (13) | Positive C. difficile toxin, culture with evidence of toxin production or histological/pathological diagnosis of C. difficile-associated disease |

Footnotes

- 1.Alberta Health Services Infection Prevention and Control. Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Provincial Surveillance Protocol. AHS 2018. www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/healthinfo/ipc/hi-ipc-sr-cdi-protocol.pdf

- 2.British Columbia Provincial Health Services Authority, Provincial Infection Control Network. Surveillance Protocol for Clostridium difficile Infections (CDI) in BC Acute Care Facilities. PICNet 2017. www.picnet.ca/wp-content/uploads/PICNet-surveillance-protocol-for-CDI-2017.pdf

- 3.Manitoba, Communicable Disease Control Unit. Clostridium difficile-Associated Diseases (CDAD). 2006.

- 4.Brunswick N. Quarterly Hospital Associated Surveillance Report. Quarter 4 (FY 2015/16). www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/h-s/pdf/en/CDC/2015-2016_Q4_HAI_Surveillance.pdf

- 5.Labrador N. Provincial Infection Control. Provincial Surveillance Protocol for Clostridium difficile infection. PIC-NL 2013. www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/CDI_surveillance_protocol_final.pdf

- 6.Scotia N. Department of Health and Wellness. Protocol for Healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile Infection Surveillance for Acute Care Hospitals in Nova Scotia. NS PHW 2015. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/hsq/public-reporting/docs/Patient_Safety_Act_CDI_Reporting_Protocol_2015.pdf

- 7.Ontario HQ. Health Quality Indicator: Hospital-acquired C.difficile infection (CDI). HQO 2018 http://indicatorlibrary.hqontario.ca/Indicator/Summary/Cdifficile-infection/EN

- 8.Island PE. Department of Health and Wellness. Provincial Infection Prevention and Control Clostridium difficile Guideline. Charlottown (PE); PE-HW 2010. www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/DHW_IPC2011.pdf

- 9.Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Surveillance provinciale des diarrhées à Clostridium difficile au Québec. INSPQ; April 2018. www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/infectionsnosocomiales/protocole_dacd_2018.pdf

- 10.Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan Infection Prevention and Control Program. Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Surveillance Protocol: Saskatchewan. S-IPCP 2016. www.ehealthsask.ca/services/resources/Resources/CDI%20Surveillance%20Protocol%20March%202016.pdf

- 11.Alberta Health Services. Performance Measures Archive. www.albertahealthservices.ca/about/Page833.aspx

- 12.British Columbia Provincial Health Services Authority. Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia. C. difficile Infection (CDI): Provincial Surveillance Reports, Q2 of 2019-2019. PICNet 2019. www.picnet.ca/surveillance/cdi/

- 13.Manitoba HS, Living A. Annual Summary of Communicable Diseases 2015: Manitoba. www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/cds/index.html

- 14.Labrador N. Surveillance and Disease Reports. Current Year's Reports. www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/informationandsurveillance.html#currentyear

- 15.Scotia N. Department of Health and Wellness. Population Health Assessment and Surveillance: Notifiable Diseases Surveillance Report. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/populationhealth/

- 16.Ontario HQ. System Performance - C. difficile Infections in Hospital Patients. www.hqontario.ca/System-Performance/Hospital-Patient-Safety/C-Difficile-Infections-in-Hospital-Patients

- 17.Island PE. Department of Health and Wellness. Prince Edward Island Infection Prevention and Control Surveillance Data Summary 2016. Charlottetown (PE); PE-HW 2016. www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/publication/prince-edward-island-infection-prevention-and-control-surveillance-data-summary-2016

- 18.Institute national de santé publique. Centre d'expertise et de référence en santé publique. Diarrhées associées au Clostridium difficile. www.inspq.qc.ca/infections-nosocomiales/spin/dacd/surveillances-anterieures

- 19.Alberta Health Services Infection Prevention and Control. Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Provincial Surveillance Protocol. AHS 2018. www.ehealthsask.ca/services/resources/Pages/Communicable-Disease.aspx

Appendix C: Supplementary data

Figure.

C-1: Hospital-associated Clostridioides difficile infection incidence rates (cases per 10,000 inpatient days)

Note: For the 2012/2013 fiscal year of Nova Scotia, only data for Q4 was available. Trendlines are dotted.

Figure.

C-2: Community-associated Clostridioides difficile infection incidence rates (per 100,000 population) and proportions (%)

Abbreviations: CA-CDI, community-associated Clostridioides difficile infection; IR, incidence rates

Note: Prince Edward Island includes only new CA-CDI cases. Trendlines are dotted

Appendix D: Detailed data for hospital and community-acquired Clostridioides difficile infections

Table. D-1: Data for hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile infections: 2011–2017.

| Year | Type of data | Provinces | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | BC | NB | NL | NSa | ONb | PEc | QC | SK | ||

| 2011–2012 | rate | 4.2 | 8.1 | n/a | 1.6 | n/a | 3.5 | 1.8 | 7.27 | n/a |

| Number of cases | 1,200 | 2,212 | n/a | 71 | n/a | 3,555 | 26 | 3,778 | n/a | |

| TID | 2,846,938 | 2,733,174 | n/a | 443,750 | n/a | 10,223,096 | 141,552 | 5,196,485 | n/a | |

| CIHI TID | 2,883,600 | 2,616,700 | n/a | 479,600 | n/a | 10,261,500 | 137,900 | n/a | n/a | |

| 2012–2013 | rate | 4.1 | 6.5 | n/a | 2.0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 3.0 |

| Number of cases | 1,166 | 1,835 | n/a | 89 | 61 | 3,356 | 55 | 3,794 | 184 | |

| TID | 2,857,501 | 2,825,727 | n/a | 445,000 | 192,430 | 10,258,361 | 143,690 | 5,240,187 | 613,333 | |

| CIHI TID | 2,928,400 | 2,653,200 | n/a | 485,700 | n/a | 10,345,000 | 143,700 | n/a | 1,010,300 | |

| 2013–2014 | rate | 4.3 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 2.5 |

| Number of cases | 1,263 | 1,309 | 228 | 97 | 210 | 3,086 | 52 | 3,689 | 213 | |

| TID | 2,929,444 | 2,883,121 | 844,444 | 485,000 | 744,868 | 10,174,367 | 140,766 | 5,136,300 | 852,000 | |

| CIHI TID | 2,996,200 | 2,709,000 | 804,400 | 500,100 | 925,300 | 9,254,300 | 140,700 | n/a | 960,700 | |

| 2014–2015 | rate | 3.5 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 3.2 |

| Number of cases | 1,065 | 1,206 | 208 | 107 | 195 | 2,707 | 47 | 3,455 | 296 | |

| TID | 3,059,257 | 2,903,390 | 866,667 | 509,524 | 831,901 | 10,274,057 | 139,350 | 5,091,013 | 925,000 | |

| CIHI TID | 3,120,000 | 2,731,100 | 830,600 | 511,400 | 943,600 | 9,199,000 | 139,300 | n/a | 969,300 | |

| 2015–2016 | rate | 3.6 | 4.8 | 2.77 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| Number of cases | 1,091 | 1,423 | 238 | 127 | 216 | 2,645 | 31 | 2,979 | 217 | |

| TID | 3,058,834 | 2,943,047 | 859,206 | 488,462 | 803,310 | 10,260,427 | 133,640 | 5,046,574 | 943,478 | |

| CIHI TID | 3,111,200 | 2,765,100 | 747,600 | 494,000 | 907,100 | 9,203,700 | 131,200 | n/a | 941,900 | |

| 2016–2017 | rate | 3.4 | 4.1 | n/a | n/a | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 2.8 |

| Number of cases | 1,043 | 1,190 | n/a | n/a | 266 | 2,388 | 43 | 2,330 | 265 | |

| TID | 3,098,415 | 2,908,197 | n/a | n/a | 813,469 | 10,345,978 | 150,116 | 5,022,104 | 946,429 | |

| CIHI TID | 3,219,300 | 2,799,400 | n/a | n/a | 912,100 | 9,387,400 | 146,900 | n/a | 956,700 | |

| Pooled | rate | 3.8 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 6.5 | 2.7 |

| Number of cases | 6,828 | 9,175 | 674 | 491 | 948 | 17,737 | 254 | 20,025 | 1,175 | |

| TID | 17,850,389 | 17,196,656 | 2,570,317 | 2,371,735 | 3,385,978 | 61,536,286 | 849,114 | 30,732,663 | 4,280,240 | |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; CIHI, Canadian Institute for Health Information; n/a, data not available; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; TID, total input days

a For the 2012–2013 fiscal year, only data for Q4 were available

b Number of cases in Ontario were aggregated from monthly data

c Total inpatient days of Prince Edward Island were an approximation for using inpatient days (excludes psychiatric) derived from “Health PEI Annul Report”. Case counts for each fiscal year were provided by the Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Wellness

Notes:

1 If there was a discrepancy between the data in the report of that year and the same kind of data in the latest report, data in the latest reports were used. For example, if the rate reported in the 2011 report was different from the rate of 2011 in the 2016 report, the rate in the 2016 report was used

2 Data unbolded indicate that the data were collected directly from the reports or provided by the province. Data bolded indicate that the data were estimated

3 Rates were calculated using TID estimated from provincial data

4 CIHI TID were derived from CIHI Management Information System database and calculated according to the provincial surveillance protocols:

Alberta: Overall TID - Extended care/chronic TID, unable to extract TID for patients less than one year old

British Columbia: Overall TID - Extended care/chronic TID - Rehabilitation - Psychiatric TID, unable to extract TID for patients less than one year old

New Brunswick: Overall TID

Newfoundland and Labrador: Overall TID

Nova Scotia: Overall TID - Extended care/chronic TID, unable to extract TID for patients less than one year old

Ontario: Overall TID, unable to extract TID for patients less than one year old

Prince Edward Island: TID (excludes psychiatric)

Quebec: Data not available

Saskatchewan: Overall TID, unable to extract TID for patients less than one year old

Table. D-2: Data for community-associated Clostridioides difficile infections: 2011–2017.

| Year | Type of data | BC | NL | PE | QC | SK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–2012 | Number of CA cases | 753 | 91 | 56 | 641 | - |

| Total | 3,613 | 205 | 91 | 5,431 | - | |

| Population | 4,499,139 | - | 144,038 | 8,007,656 | - | |

| Rate | 16.74 | 17.50 | 38.88 | 8.00 | - | |

| Percentage | 20.84 | 44.39 | 61.54 | 11.80 | - | |

| 2012–2013 | Number of CA cases | 794 | 165 | 59 | 698 | 64 |

| Total | 3,246 | 319 | 127 | 5,448 | 305 | |

| Population | 4,546,290 | - | 145,080 | 8,085,906 | 1,088,030 | |

| Rate | 17.46 | 31.60 | 40.67 | 8.63 | 5.88 | |

| Percentage | 24.46 | 51.72 | 46.46 | 12.81 | 20.98 | |

| 2013–2014 | Number of CA cases | 636 | 199 | 75 | 751 | 100 |

| Total | 2,376 | 355 | 143 | 5,251 | 364 | |

| Population | 4,590,081 | - | 145,198 | 8,151,331 | 1,106,838 | |

| Rate | 13.86 | 37.90 | 51.65 | 9.21 | 9.03 | |

| Percentage | 26.77 | 56.06 | 52.45 | 14.30 | 27.47 | |

| 2014–2015 | Number of CA cases | 674 | 174 | 64 | 737 | 95 |

| Total | 2,260 | 367 | 121 | 5,004 | 440 | |

| Population | 4,646,462 | - | 145,915 | 8,210,533 | 1,122,653 | |

| Rate | 14.51 | 33.00 | 43.86 | 8.98 | 8.46 | |

| Percentage | 29.82 | 47.41 | 52.89 | 14.73 | 21.59 | |

| 2015–2016 | Number of CA cases | 866 | 115 | 57 | 909 | 84 |

| Total | 2,893 | 349 | 94 | 4,529 | 372 | |

| Population | 4,694,699 | - | 146,791 | 8,254,912 | 1,133,165 | |

| Rate | 18.45 | 21.90 | 38.83 | 11.01 | 7.41 | |

| % | 29.93 | 32.95 | 60.64 | 20.07 | 22.58 | |

| 2016–2017 | Number of CA cases | 846 | - | 61 | 880 | - |

| Total | 2,423 | - | 109 | 3,856 | - | |

| Population | 4,757,658 | - | 149,472 | 8,321,888 | - | |

| Rate | 17.78 | - | 40.81 | 10.57 | - | |

| Percentage | 34.92 | - | 55.96 | 22.82 | - |

Abbreviations: BC, British Columbia; CA, community-associated; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; -, no data

Note: Data unbolded means data collected directly from the reports or provided by the province, otherwise, the data were estimated

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Y Xia has no conflict of interest

MC Tunis, K Amaratunga and A House are employees of the Public Health Agency of Canada

C Frenette and K Katz are co-Chairs of CNISP

SR Rose is a Past-President of Institute of Public Administration of Canada

C Quach is the current Chair of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization and the Past-President for the Association for Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada

Funding: This study did not receive any funding.

References

- 1.Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance program (CNISP). Surveillance for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) Ottawa (ON): PHAC 2018. https://ipac-canada.org/photos/custom/Members/CNISPpublications/CNISP%202019%20CDI%20protocol_FINAL_EN.pdf

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. 2018 Surveillance for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). PHAC 2017. https://www.ammi.ca/Guideline/44.ENG.pdf

- 3.Joshi NM, Macken L, Rampton DS. Inpatient diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Med (Lond) 2012. Dec;12(6):583–8. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan-Canadian Public Health Network; The Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Task Group. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Data Requirements for Priority Organisms. PCPHN 2016. www.phn-rsp.ca/pubs/arsdrpo-dsecrao/index-eng.php#3.1

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada. Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistant Organism (ARO) Surveillance Data from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2016. Ottawa (ON): PHAC 2018. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/canadian-nosocomial-infection-surveillance-program-summary-report-aro-data-2012-2016.html#a1

- 6.Alberta Health Services Infection Prevention and Control. Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Provincial Surveillance Protocol. AHS 2018. www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/healthinfo/ipc/hi-ipc-sr-cdi-protocol.pdf

- 7.Manitoba, Communicable Disease Control Unit. www.picnet.ca/wp-content/uploads/PICNet-surveillance-protocol-for-CDI-2017.pdf

- 8.Manitoba, Communicable Disease Control Unit. Clostridium difficile-Associated Diseases (CDAD). 2006.

- 9.Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Infection Control. Provincial Surveillance Protocol for Clostridium difficile infection. PIC-NL 2013. www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/CDI_surveillance_protocol_final.pdf

- 10.Nova Scotia, Department of Health and Wellness. Protocol for Healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile Infection Surveillance for Acute Care Hospitals in Nova Scotia. NS PHW 2015. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/hsq/public-reporting/docs/Patient_Safety_Act_CDI_Reporting_Protocol_2015.pdf

- 11.Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee. Annex C: Testing, Surveillance and Management of Clostridium difficile. PIDAC 2013. www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/PIDAC-IPC_Annex_C_Testing_SurveillanceManage_C_difficile_2013.pdf

- 12.Prince Edward Island. Health and Wellness. Provincial Infection Prevention and Control Clostridium difficile Guideline. PE-HW 2010. www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/c_diff_infection_guideline.pdf

- 13.Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Surveillance provinciale des diarrhées à Clostridium difficile au Québec. INSPQ 2018. www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/infectionsnosocomiales/protocole_dacd_2018.pdf

- 14.Saskatchewan, Infection Prevention and Control Program. Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Surveillance Protocol: Saskatchewan. S-IPCP 2016. www.ehealthsask.ca/services/resources/Resources/CDI%20Surveillance%20Protocol%20March%202016.pdf

- 15.Amaratunga K, Tarasuk J, Tsegaye L, Archibald CP, on behalf of the 2015 Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee (CIDSC). Advanced surveillance of antimicrobial resistance: summary of the 2015 CIDSC Report. Can Commun Dis Rep 2016;42(11):232–7. 10.14745/ccdr.v42i11a03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clostridium difficile Vaccine Efficacy Trial: NCT03090191. Pfizer 2019. www.pfizer.com/science/find-a-trial/nct03090191

- 17.Valneva's Clostridium difficile vaccine candidate - VLA84. Valneva. www.valneva.com/en/rd/vla84

- 18.Erickson LJ, De Wals P, Farand L. An analytical framework for immunization programs in Canada. Vaccine 2005. Mar;23(19):2470–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health Agency of Canada. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Updated Statement on the use of Rotavirus Vaccines. Can Commun Dis Rep 2010;36(4):1–37. 10.14745/ccdr.v36i00a04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System 2017 Report. PHAC 2017. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-system-2017-report-executive-summary.html

- 21.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System - Update 2018: Executive Summary. PHAC 2018. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-system-2018-report-executive-summary.html

- 22.Katz KC, Golding GR, Choi KB, Pelude L, Amaratunga KR, Taljaard M, Alexandre S, Collet JC, Davis I, Du T, Evans GA, Frenette C, Gravel D, Hota S, Kibsey P, Langley JM, Lee BE, Lemieux C, Longtin Y, Mertz D, Mieusement LM, Minion J, Moore DL, Mulvey MR, Richardson S, Science M, Simor AE, Stagg P, Suh KN, Taylor G, Wong A, Thampi N; Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program. The evolving epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in Canadian hospitals during a postepidemic period (2009-2015). CMAJ 2018. Jun;190(25):E758–65. 10.1503/cmaj.180013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akbari M, Vodonos A, Silva G, Wungjiranirun M, Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Novack V. The impact of PCR on Clostridium difficile detection and clinical outcomes. J Med Microbiol 2015. Sep;64(9):1082–6. 10.1099/jmm.0.000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AlGhounaim M, Longtin Y, Gonzales M, Merckx J, Winters N, Quach C. Clostridium difficile Infections in Children: Impact of the Diagnostic Method on Infection Rates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016. Sep;37(9):1087–93. 10.1017/ice.2016.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esteban-Vasallo MD, Naval Pellicer S, Domínguez-Berjón MF, Cantero Caballero M, Asensio Á, Saravia G, Astray-Mochales J. Age and gender differences in Clostridium difficile-related hospitalization trends in Madrid (Spain) over a 12-year period. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016. Jun;35(6):1037–44. 10.1007/s10096-016-2635-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program. 2018 CNISP HAI Surveillance Case definitions. www.ammi.ca/Guideline/53.ENG.pdf