Abstract

Transition state theory teaches that chemically stable mimics of enzymatic transition states will bind tightly to their cognate enzymes. Kinetic isotope effects combined with computational quantum chemistry provides enzymatic transition state information with sufficient fidelity to design transition state analogues. Examples are selected from various stages of drug development to demonstrate the application of transition state theory, inhibitor design, physicochemical characterization of transition state analogues, and their progress in drug development.

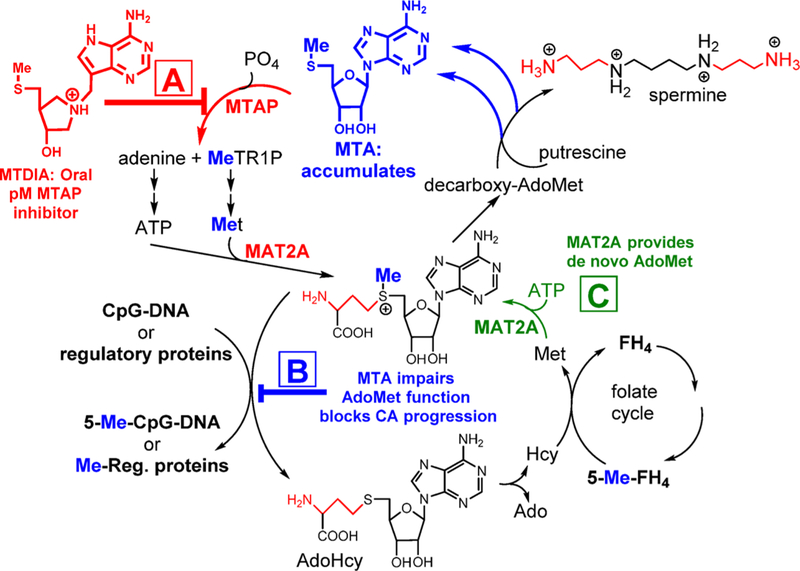

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Linus Pauling proposed over 70 years ago that “…the only reasonable picture of the catalytic activity of enzymes is that which involves an active region of the surface of the enzyme which is closely complementary in structure not to the substrate molecule itself, in its normal configuration, but rather to the substrate molecule in a strained configuration, corresponding to the “activated complex” for the reaction catalyzed by the enzyme: the substrate molecule is attracted to the enzyme, and caused by the forces of attraction to assume the strained state which favors the chemical reaction…”. And “…an enzyme complementary to a strained substrate molecule would attract more strongly to itself a molecule resembling the strained substrate molecule than it would the substrate molecule.”1 “The attraction of the enzyme molecule for the activated complex would thus lead to a decrease in its energy, and hence to a decrease in the energy of activation of the reaction, and to an increase in the rate of the reaction.”2 It was this recognition of the activated complex that Richard Wolfenden used to explain the tight binding of oxalate to lactate dehydrogenase, unsaturated analogues of substrates to 3-keto-steroid isomerase and proline racemace, the potent inhibition of cytidine deaminase by tetrahydrouridine and triose phosphate isomerase inhibition by 2-phosphoglycolate.3 Wolfenden formalized the Pauling principles by considering a thermodynamic box comparing solution (uncatalyzed) formation of product to that from the enzyme and enzyme affinity to substrate relative to that of the transition state (Figure 1). By doing so, Wolfenden concluded that ‘The attractive force between the enzyme and transition state for nonenzymatic reaction (if it could be measured) should be characterized by a binding constant exceeding by the factor F (enzyme rate acceleration) the binding constant of the substrate in the Michaelis complex… An ideal inhibitor, which perfectly resembled in its binding properties the substrate part of ETX (the transition state complex), should thus be bound as much more tightly to the enzyme than the substrate (the “binding ratio”) as the rate of the enzymatic reaction exceeds that of it nonenzymatic counterpart (the “rate ratio”). This conclusion applies whatever the nature of the binding forces (covalent, noncovalent, or both) and regardless of whether the enzyme itself is much distorted during binding and catalysis.”3 This description suggested an upper limit to the strong interactions between enzymes and putative transition state analogues.4 A sustained quest for the factor F in experimentally accessible reactions has placed upper limits near 1020 with many common enzymatic reactions in the region from 1012 to 1016.5–9 As enzymatic Km values are typically in the 10−3−10−6 M range, perfect transition states are predicted to bind with dissociation constants of 10−15−10−22 M according to the Pauling–Wolfenden proposal. These considerations place an upper limit for the affinity of transition state analogues, which by virtue of their chemical stability necessarily differ from the properties of the unstable and ethereal transition states. In practice, few if any inhibitors have reached these affinities. Most commonly, compounds considered transition state analogues bind with dissociation constants in the nanomolar to femtomolar range (10−9 −10−15 M).10

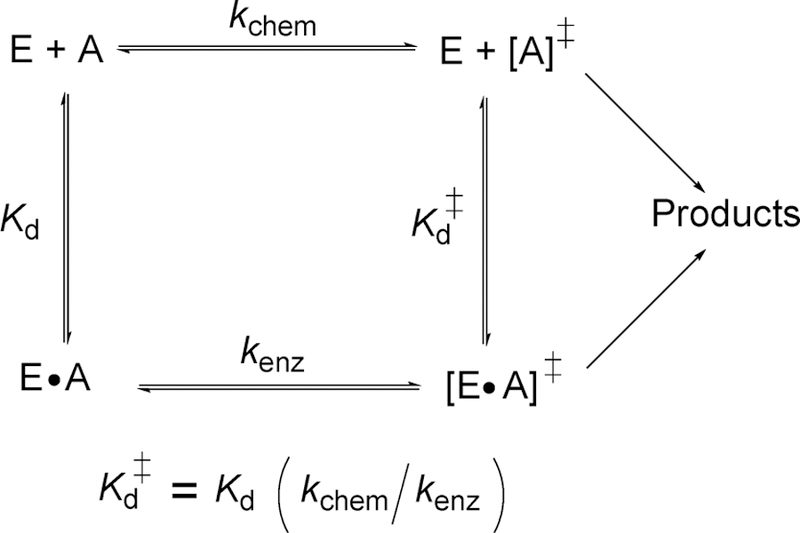

Figure 1.

Thermodynamic box for describing the equilibrium binding constant of the transition state as described by Pauling and formalized by Wolfenden. E and A are enzyme and reactant, kchem and kenz are the rates of transition state formation without and with enzyme, and Kd and Kd‡ are dissociation constants for the Michaelis and transition state complexes, respectively.

2. PROPERTIES OF THE TRANSITION STATE

Understanding that mimics of the transition state will provide powerful inhibitors for the cognate enzymes, the search for transition state information was underway. Initially, identification of powerful inhibitors suggested transition state features. Thus, the tight binding of 2-phosphoglycolate to triose phosphate isomerase supported the formation of an ene–diol intermediate, and the tight binding of tetrahydrouridine to cytidine deaminase suggested a Meisenheimer intermediate for the proposed nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction for cytidine deamination.11,12 Intermediates are not transition states but are expected to lie at higher energy levels than reactants, and mimics of intermediates would also be consistent with the suggestions of the tight-binding hypothesis.13 The transition states of chemical and enzymatic reactions correspond to bond loss and bond formation. Bond vibrational modes in biological molecules have time constants on the femtosecond time scale; thus, the transition state lifetimes, the loss of a restoring mode, are very much shorter than the catalytic turnover numbers of enzymes, typically 1–103 s−1. The brief transition state lifetimes are experimentally problematic in providing spectroscopic characterization, and it is necessary to use deductive measures of kinetic isotope effects and computational chemistry to provide well-defined geometric and electrostatic views of enzymatic transition states.14,15

2.1. Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Approach to Enzymatic Transition States

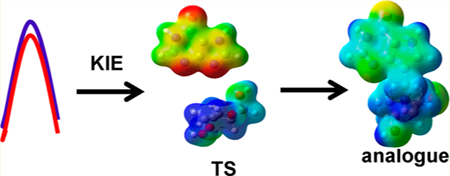

The development of KIEs applied to chemical reactions and later extended to enzyme-catalyzed reactions provided the chemical detail needed for the essential features of the transition state, namely, geometry (bond angles and lengths) and electrostatic potentials. These descriptors are conveniently provided from the wave function of the transition state, derived from experimental KIEs, and treated as a fixed structure for the purpose of building a computational model of the transition state as a guide to design transition state analogues. This approach has been detailed in readily available methods and review articles.16–19 Here, the steps in this approach will be summarized and the methods for enzymatic synthesis of the isotopically labeled substrates will be outlined. A more complete guide to “how to do it” literature is provided in section 15.1.

The approach to understand the nature of enzymatic transition states begins with a primary data set of kinetic isotope effects, refines these to intrinsic values, and compares them to quantum-chemically defined potential transition states for experimental and theoretical agreement. Experimental determination of enzymatic transition states begins with (1) synthesis of the substrates with isotope labels at individual positions involved in the reaction coordinate and remote reporter groups. (2) Intrinsic isotope effects are required for valid analysis of the chemical step and can be established from kinetic and commitment measurements. (3) Gaussian (or similar) quantum mechanical (QM) approaches are used to iterate systematically through possible transition states to find a transition state with the nearest match of the intrinsic kinetic isotope effects. (4) Electrostatic potential surfaces are calculated from the wave functions of the reactant and transition state, treating the transition state as a stationary structure. (5) Stable chemical mimics of the transition state are designed based on a geometric and molecular electrostatic match of the transition state. (6) Chemical synthesis of transition state analogues is followed by kinetic analysis against the target enzyme. (7) Inhibitory analogues are evaluated for biological efficacy by testing in cellular and animal models.20

2.2. Synthesis of Isotopically Labeled Reactants

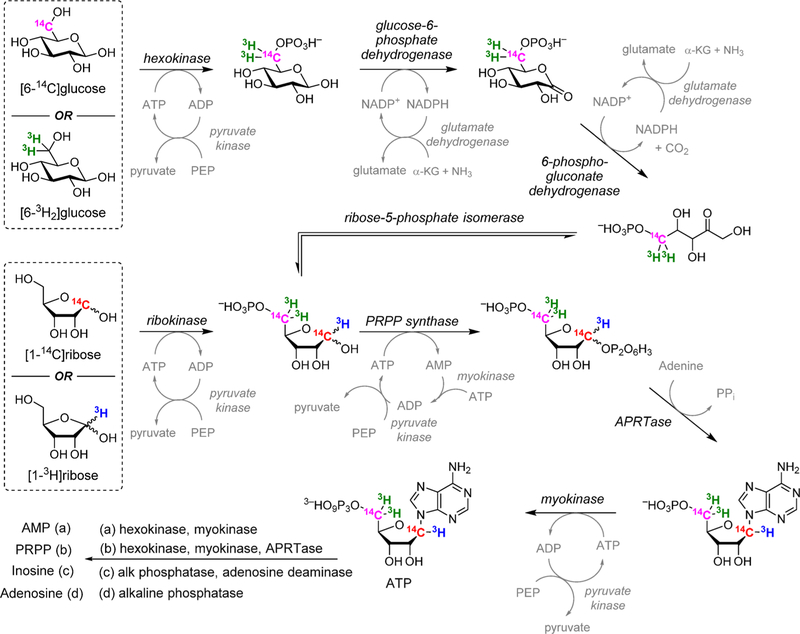

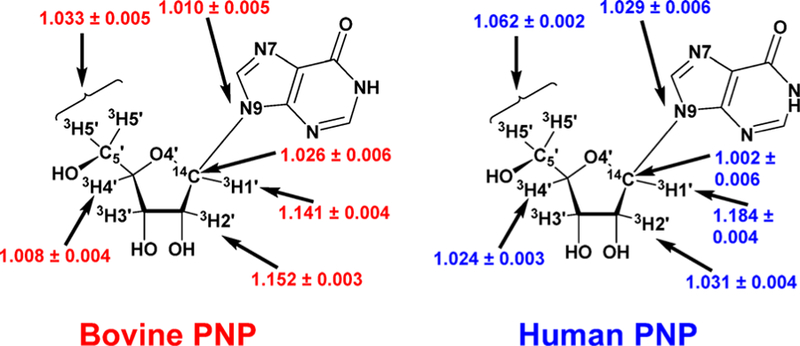

For the N-ribosyltransferases, a focus of this review, the experimental range of KIEs requires isotopic labels at the anomeric carbon of ribose (the reaction center) and the nitrogen of the leaving group, both of which give primary isotope effects to define the extent of leaving group bond breaking and the extent of bond-forming participation of the incipient nucleophiles (water for hydrolases and phosphate for phosphorylases). The α-secondary KIE from the hydrogen at the anomeric carbon provides information on the rehybridization of the reaction center at the transition state. The β-secondary KIE from the hydrogen at C2′ of ribose provides ribose pucker information, as this isotope effect is strongly affected by hyperconjugation to the breaking leaving group bond and the dihedral angle between C2′–H2′. These four isotope effects define the major properties of the transition state. Every additional measurement contributes additional details. For example, the α-O4′ isotope effect from the ribosyl ring provides a second estimate of the rehybridization of the anomeric carbon at the transition state. Leaving group effects, e.g., the N7 KIE in purine leaving groups, indicate the extent of leaving group protonation at the transition state. In competitive isotope label experiments, the atoms mentioned above are made heavy with 18O, 15N, 14C, 13C, 3H, or 2H and remote labels report on the discrimination between the chemically influenced KIE and the remote, chemically uninfluenced isotope label. Examples for the synthesis of isotopically labeled ATP, AMP, 5-phosphoribosyl 5-pyrophosphate, inosine, and adenosine are provided (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Enzymatic synthesis of radiolabeled reactants PRPP from specifically labeled glucose or ribose. Product of a single-pot coupled synthesis yields ATP. Subsequent conversions to AMP, PRPP, inosine, and adenosine are shown. Isotopic labels in any of the reactants can be used to label the desired position in products. Other transferases can replace APRTase to generate other nucleotides as intermediates or products.21–23

2.3. Binding Isotope Effects and Remote Labels

Remote labels at isotopically KIE-”silent” positions are required for the competitive radioisotope method. Chemical studies that break the N-riboside bond of AMP to form adenine and ribose 5-phosphate provide an example. The [5′–14C]AMP molecule provides an isotope label remote from the site of chemistry. A mixture of [5′–14C]AMP and [1′–3H]AMP provides ribose 5-phosphate products with a ratio of 14C to 3H representing the 1′–3H KIE. Likewise, a mixture of [5′–3H]AMP and [1′–14C]AMP provides ribose 5-phosphate products with a ratio of 14C to 3H representing the 1′–14C KIE. Double remote labels can be used to measure isotope effects from chemically stable isotopes like 2H, 13C, 15N, and 18O. A mixture of [5′–14C; 9-15N]AMP and [5′–3H]AMP provides ribose 5-phosphate products with a ratio of 14C to 3H representing the [9-15N]AMP KIE. Remote labels require extra caution as remote binding isotope effects are common with 3H.24 On formation of the Michaelis complex, 3H–C bonds can be influenced by the catalytic site environment. For each degree of distortion from the solution sp3 geometry, an approximate 1% 3H binding isotope effect will be observed from 3H–C bonds.25 These values are normal or inverse (the 3H-labeled molecule binding weaker or stronger) if the 3H–C modes are less or more constrained in the bound complexes, respectively. For this reason it is always essential to measure the BIE and/or KIE of remote 3H–C labels. This is experimentally direct by either binding or kinetic experiments with mixtures of [5′–3H]AMP and [5′–14C]AMP. Remote labels with 14C are preferred, as there are no significant binding isotope effects for remote 14C labels, in contrast to those for 3H.26,27 We will see some examples of these isotope effects in the transition state analyses described herein. Binding isotope effects can be a significant contribution to experimentally measured KIEs. For example, in binding isotope effect studies for glucose to human brain hexokinase, binding isotope effects from 6.5% normal to −7.3% inverse were observed in individually 3H-labeled glucose molecules.28 Experimentally, these effects have been considered a boon by providing bond distortional information for understanding ground state stabilization or destabilization and a bane, by requiring binding isotope effect corrections when measuring KIEs for transition state analysis.29,30

3. AMP NUCLEOSIDASE

3.1. AMP Nucleosidase Kinetic Isotope Effects

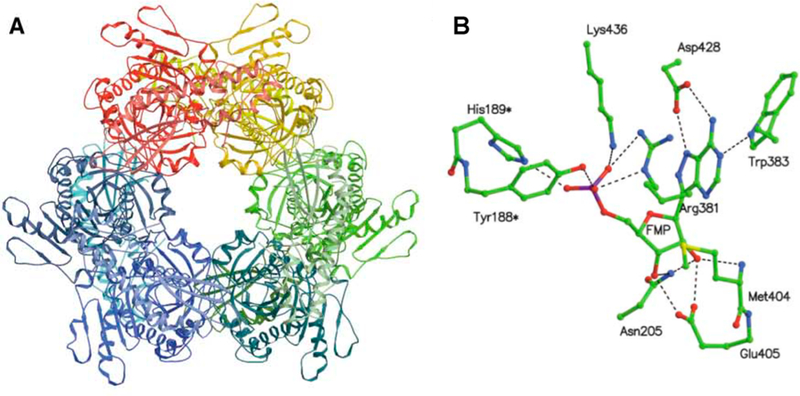

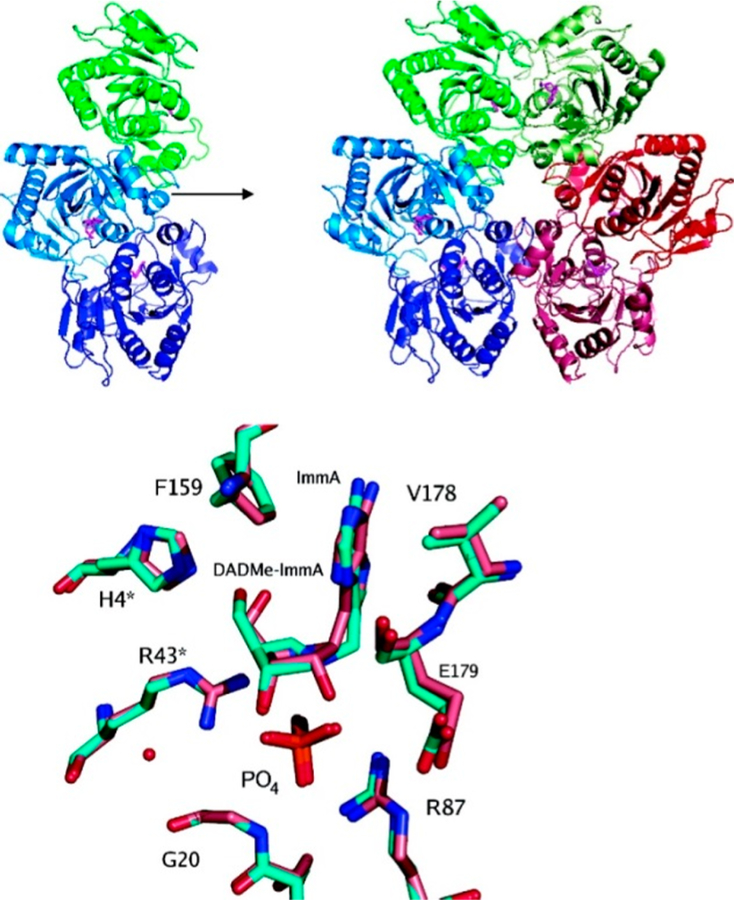

AMP nucleosidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of AMP to adenine and ribose 5-phosphate with allosteric activation by MgATP2– and inhibition by inorganic phosphate.31,32 The enzyme is found only in bacteria and has been proposed to regulate the relative ratio of ATP to less-phosphorylated nucleotides by controlled hydrolysis of AMP to products that are easily recycled to the adenylate pool.33 As AMP nucleosidase is not found in mammals, it has been proposed as a potential antibacterial target.34 The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli enzyme is homohexameric with each of the six catalytic sites composed of contacts from two subunits (Figure 3).35 A test of its suitability as a target came from genetic inactivation of the enzyme in E. coli. Loss of the catalytic activity had the effect of increasing intracellular ATP concentrations, resulting in cellular cryoprotection.36 Thus, AMP nucleosidase is an unlikely drug target. Nevertheless, the enzyme played an important role in the early application of kinetic isotope effects to understand transition state structure. Kinetic isotope effect studies compared KIE profiles for AMP nucleosidases from different sources with the nonenzymatic chemical solvolysis of AMP.21,22 This catalytic activity was first characterized in the enzyme from Azotobacter vinelandii, a hexameric enzyme that has been well characterized kinetically.31,32,37 The crystal structure of the A. vinelandii enzyme has not been reported.

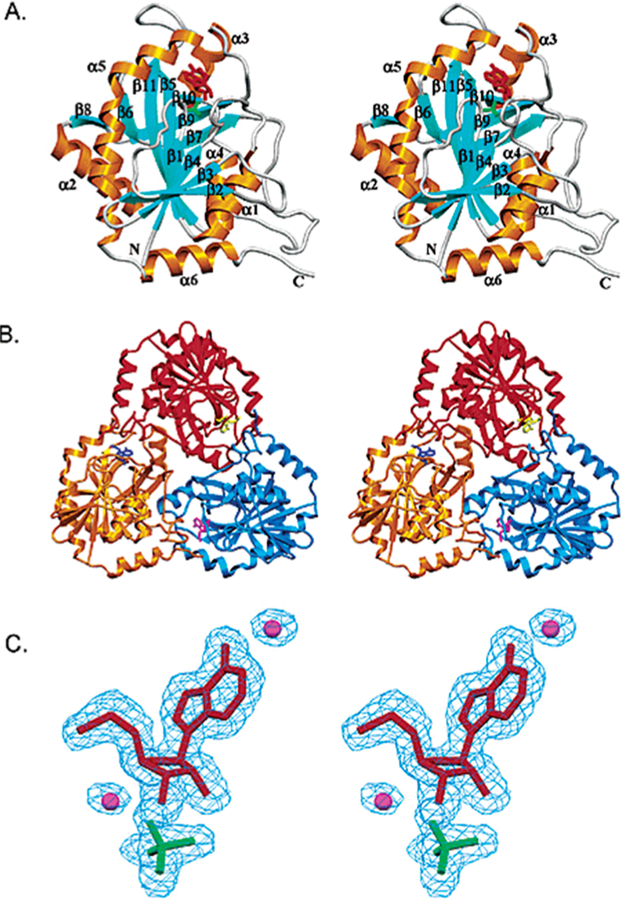

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of E. coli AMP nucleosidase hexamer with formycin 5′-phosphate at the catalytic sites (A), and detailed contacts between the enzyme and formycin 5′-phosphate at the catalytic sites (B). Catalytic site contacts are from the parental and adjacent (*) subunit contacts. From PDB structure 1T8S. Adapted with permission from ref 35. Copyright 2004 Elsevier.

3.2. Comparing Chemical and Enzymatic KIEs

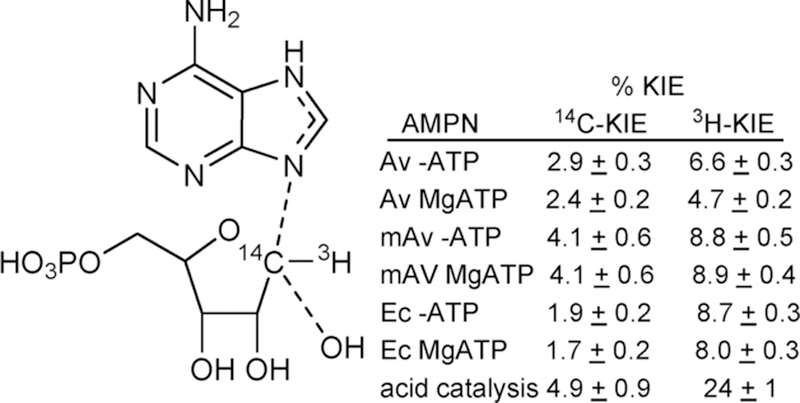

The transition states of AMP nucleosidases (AMPNs) have been interrogated by KIE analysis using three distinct forms of the enzyme. The A. vinelandii enzyme requires MgATP2− as an essential kcat activatior with the unactivated enzyme being 200-fold less active than the activated form (Av – ATP and Av MgATP in Figure 4). A mutant form of the A. vinelandii enzyme was developed with a 50-fold decreased kcat but unchanged binding of the allosteric regulators, MgATP2− or inorganic phosphate (mAv – ATP and mAv MgATP in Figure 4).38 The E. coli enzyme differs from the A. vinelandii homologue by a mechanism of allosteric activation with MgATP2− causing decreased Km values by several orders of magnitude (Ec – ATP and Ec MgATP in Figure 4).39 This early application of isotope effects provided an experimental approach toward understanding the sensitivity of the transition state structure in response to remote regulators. It also probed changes in transition states in enzymes with mutationally altered kinetic values. A direct chemical comparison was possible for this reaction.

Figure 4.

Kinetic isotope effects for [1′–14C]AMP primary effect and [1′–3H]AMP α-secondary effect with different enzyme conditions and compared to the acid-catalyzed solvolysis of AMP in 0.1 M HCl at 50 °C.21,22 % KIE = 100% (KIE – 1.000).

3.3. Qualitative Analysis of AMP Nucleosidase KIEs

Nucleophilic displacements at carbon generate 14C primary KIE values of up to 14% for transition states with symmetric (SN2) attack of the nucleophile and departure of the leaving group.40 Atomic crowding around the reaction center restrains the out-of-plane bending modes for the 1′–3H atom to be similar to the reactant state, giving KIE values near unity. Conversely, classic SN1 reactions give near unity 1′–14C primary KIE values but large 1′–3H values (above 30%) as the transition state ribocation has a fully developed sp2 geometry where increased out-of-plane modes for the C–3H bond contribute to large seconday 3H-KIE values.40,41 On the basis of similar KIE values for the enzymatic reactions with altered catalytic rates of over 3 orders of magnitude, intrinsic isotope effects were assumed. Small 14C and modest 3H KIE values were interpreted as transition states dominated by SN1 character, with significant participation of the attacking water (or hydroxyl ion) nucleophile with catalytic site crowding to prevent out-of-plane freedom for the 3H atom, resulting in small 3H KIE values on the enzyme but large ones in solution. Dissociated transition states with ribocation character generate an anionic leaving group that requires neutralization for efficient departure from the transition state. Leaving group neutralization was proposed by N7 protonation. Thus, an elevated pKa and protonation at N7 described part of the transition state for the AMP nucleosidases, suggesting formycin 5′-phosphate as an inhibitor (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Formycin 5′-phosphate differs from AMP by a chemically stable C–C ribosidic bond and elevated pKa at N7 to mimic protonation of this group at the transition state.

3.4. Formycin 5′-Phosphate as a Transition State Analogue

Formycin 5′-phosphate was proposed as a transition state analogue for AMP nucleosidase based on kinetic, KIE, and substrate specificity studies.42 pKa profiles suggested an ionizable enzyme group (R1, pKa 6.2) to be the proton donor for N7 at the transition state.37 Formycin (7-amino-3-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)pyrazolo-(4,3-d)-pyrimidine) is a natural product isolated from culture media of Nocardia interforma.43 It is phosphorylated in mammalian cells and can be readily converted to the 5′-phosphate by chemical phosphorylation.44 Formycin 5′-phosphate gave a dissociation constant of 43 nM for the A. vinelandii AMP nucleosidase compared to a Km of 120 μM for the AMP substrate, a factor of 2800 tighter binding for the analogue (Figure 5).44 The crystal structure of the E. coli AMP nucleosidase with formycin 5′-phosphate at the catalytic sites revealed Asp428 to be responsible for protonation of N7 in a bidentate interaction between the N6 amino group and N7 (Figure 3). The reaction is completed by water addition to the ribocationic transition state; however, no catalytic water was observed in the crystal structure nor is there a nearby catalytic base to assist water ionization toward an attacking hydroxide ion.35 Formycin analogues have provided useful mechanistic tools but have not found use as antibiotics or antimetabolites.

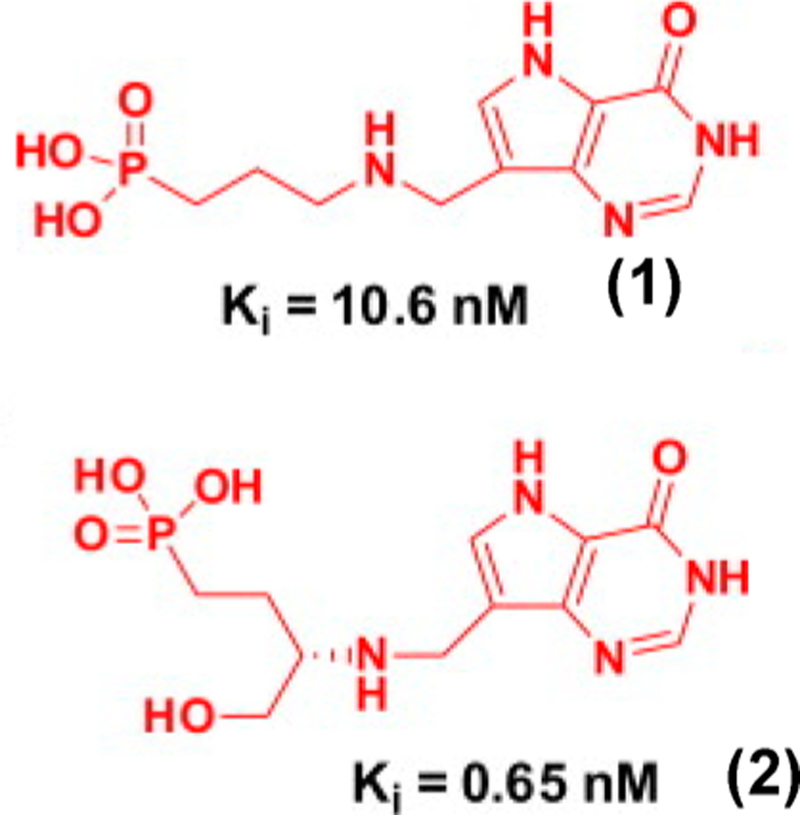

4. ADENOSINE DEAMINASE

4.1. Function and Deficiency

Adenosine deaminases catalyze the hydrolytic conversion of adenosine (and other 6-substituted purine ribosides) and their 2′-deoxy-counterparts to the 6-oxypurine ribosides. Genetic deficiency of human adenosine deaminase causes severe combined immune deficiency leading to infections and death in the first years of life.45–47 Lack of adenosine deaminase (less than 1% of normal) causes accumulation of 2′-deoxyadenosine in the blood, enzymatic conversion 2′-deoxyATP in rapidly dividing cells of the immune system, errors in DNA replication, and active repair processes leading to p53 activation and apoptotic cell death.48 The preferred treatment is compatible bone marrow (stem cell) transplant, and a secondary treatment can be accomplished by enzyme replacement therapy with stabilized adenosine deaminase constructs to remove 2′-deoxyadenosine from the circulation.49 Transition state analogue inhibitors of human adenosine deaminase have been used as anticancer agents because of the high specificity of adenosine deaminase deficiency for rapidly dividing cells of the immune system. In addition, many 6-amino purine nucleoside antimetabolites used as anticancer agents are susceptible to inactivation by the action of adenosine deaminase, and their use in combination with 2′-deoxycoformycin prevents inactivation by deamination.

4.2. Mechanism and Structure

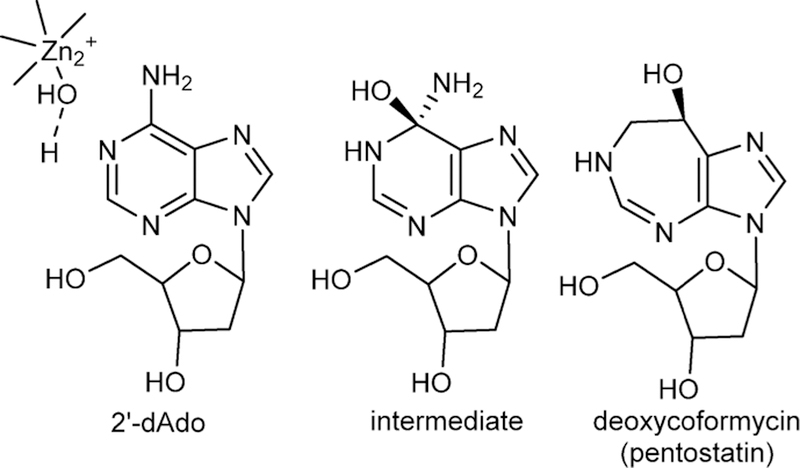

The catalytic mechanism of adenosine deaminase was first proposed to be a two-step C6 hydrolytic mechanism with the discovery that 6-amino, 6-Cl, and several other 6-substituents could be hydrolyzed from purine ribosides with a common rate-limiting step (Figure 6).50,51 The mechanism was confirmed by the NMR finding that an equilibrium existed between adenosine deaminase and [2-13C]-and [6-13C]purine ribosides where the hybridization of C6 changed from sp2 to sp3 on the enzyme as a result of a new bond to oxygen or sulfur.52 Thus, the enzyme is capable of reversibly adding to the C6 of the purine base nucleoside, also supported by the solvent exchange of H218O into the O6 of inosine.53 Earlier kinetic isotope effect studies demonstrated an unusual, large inverse solvent isotope effect for the deamination of adenosine, and this was interpreted as protonation of N1 by a Cys group to form a thiol anion at an early step in the mechanism, in coordination with addition of the hydroxyl group at C6, part of the sp2 to sp3 rehybridization.54 At the time the involvement of Zn2+ at the catalytic site was not known, making the thiol active site contact a logical hypothesis. The first crystal structure of an adenosine deaminase (mouse) in complex with 6-hydroxyl-1,6-dihydropurine ribonucleoside, a transition state analogue, revealed that the catalytic site contained a tightly bound zinc cofactor also chelated to the 6R-hydroxyl group isomer of the transition state analogue (Figure 7).55 The structure explained the inverse solvent isotope effect reported earlier, as metal-based ionization of water prior to nucleophilic addition also generates an inverse solvent isotope effect.56 No Cys groups are near the catalytic site, including the chelation sphere of the Zn2+. Three His nitrogens, a carboxylate oxygen, and the 6-hydroxyl group of the bound intermediate complete the coordination complex.

Figure 6.

Substrate 2′-deoxyadenosine (2′-dAdo) enzyme-stabilized intermediate at the catalytic site and the natural product transition state analogue inhibitor, deoxycoformycin. The Zn2+-activated water nucleophile is shown. In clinical use, the analogue is known as pentostatin.

Figure 7.

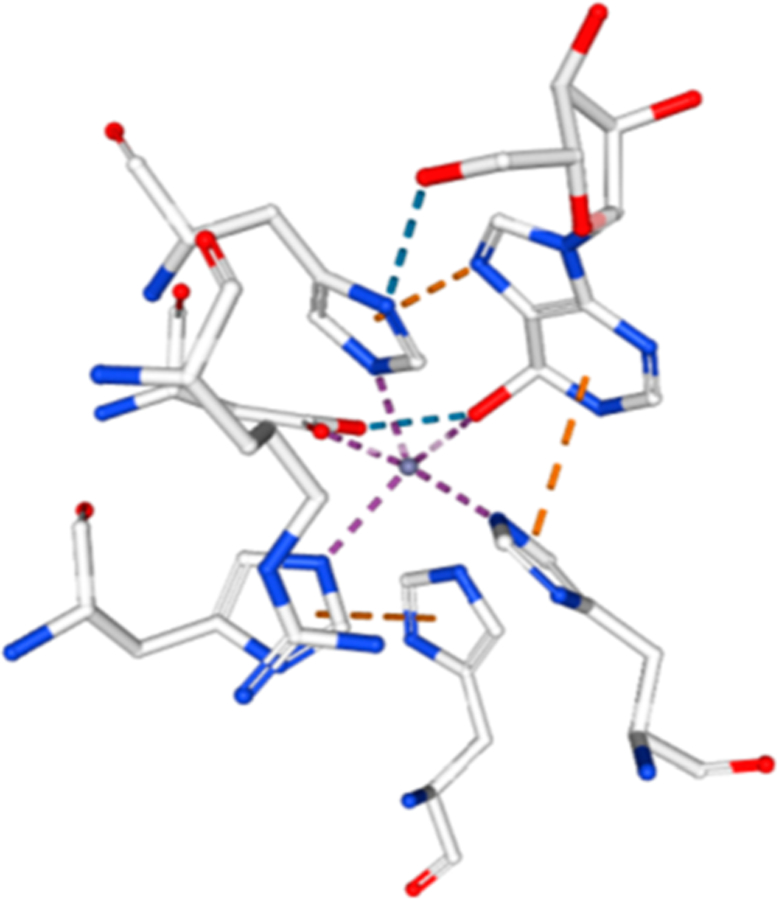

Zn2+ cation at the catalytic site of bovine adenosine deaminase from PDB 1FKX, D296A mutant. Zn2+ ion is the central sphere in the figure and is in contact with the protein ligands and the 6-hydroxyl group of 6-hydroxydihydroadenosine.

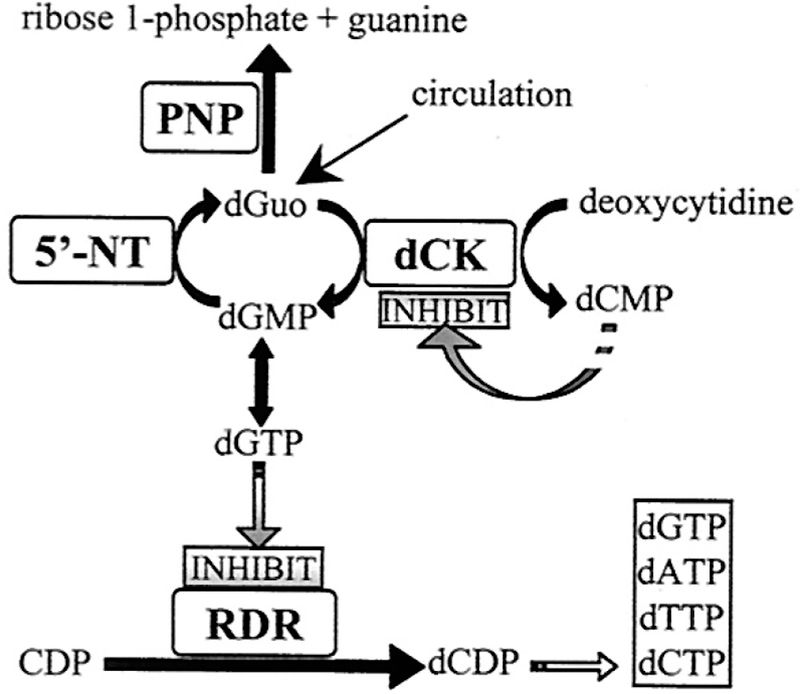

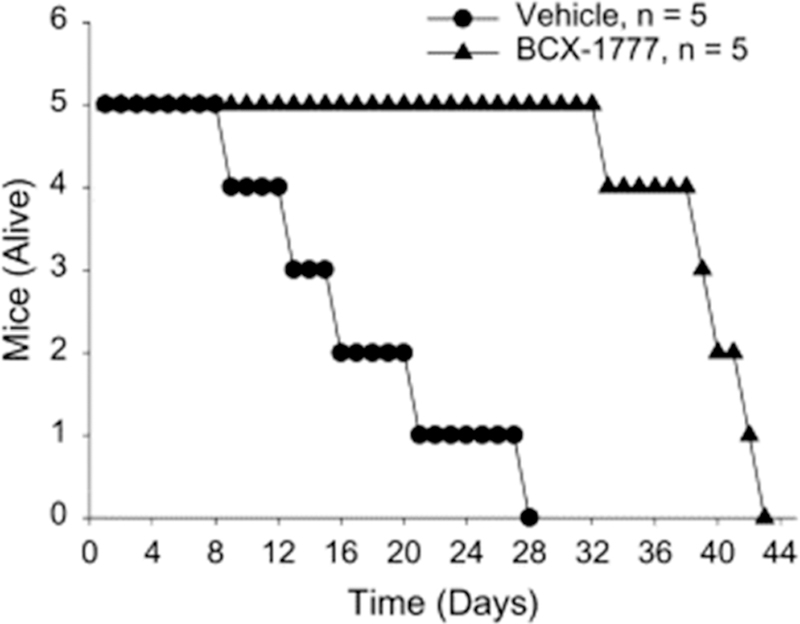

4.3. Coformycins

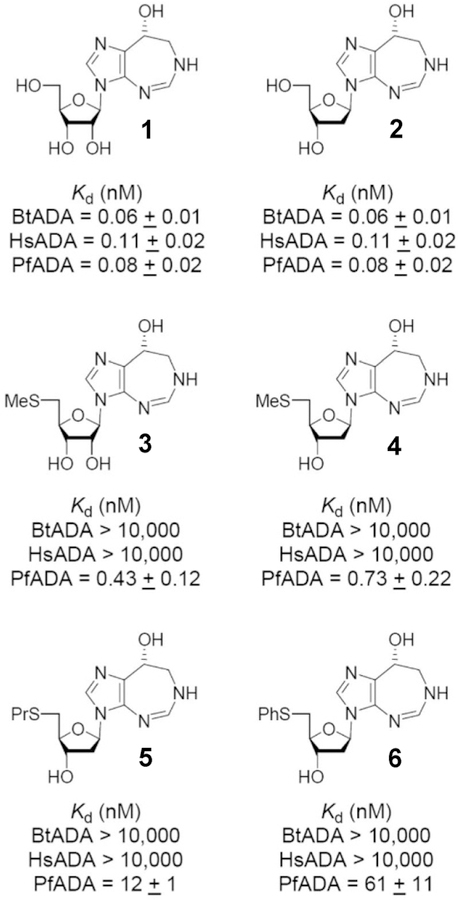

Two natural product transition state analogues for adenosine deaminase, coformycin (1) and 2′-deoxycoformycin (2), have been isolated from culture media of Streptomyces antibioticus, N. interforma, and Streptomyces kaniharaensis SF-557 (Figure 8).57–59 The same cultures that produce formycin also produce coformycin, hence the name. Their structural determination, characterization as inhibitors of adenosine deaminase, and chemical synthesis were completed within a few years of the initial discovery. Dissociation constants for human adenosine deaminase with 2′-deoxycoformycin (pentostatin) and coformycin have been reported to be 2.5 and 10 pM, respectively, matching the 4-fold difference in affinities for adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine.60–62 On the basis of the original observations that adenosine deaminase deficiency causes severe combined immunodeficiency disease (both B and T cells), pentostatin was entered into clinical trials for a variety of lymphoid malignancies.63–66 Strong responses have been observed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), but even more impressive responses are observed with the relatively rare hairy cell leukemia (HCL). Treatment with pentostatin causes adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine to accumulate in the blood with specific accumulation of dAMP and dATP in lymphocytes, where high expression of deoxycytidine kinase mistakenly converts 2′-deoxyadenosine to dAMP which accumulates as dATP because of low expression of 5′-nucleotidase activity in these rapidly dividing cells.67 The expression of enzymes causing dATP accumulation provides the cancer cell specificity.68

Figure 8.

Dissociation constants (Kd) for inhibiton of ADAs from bovine (Bt), human (Hs), and Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) sources. Reproduced from ref 434. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

The picomolar binding affinity of the coformycins with adenosine deaminase permits atomic dissection of the energy of binding by inhibitor analogues. Changing the stereochemistry of the 8-R hydroxyl center to the 8-S configuration reduces the binding affinity by 9.8 kcal/mol.69 Deletion of the HN CH=N group from the 7-membered ring decreases binding by 7 kcal/ mol, and deletion of the 2′-deoxyribose group decreases binding by 8.5 kcal/mol.70 Wolfenden has interpreted these large energy changes as “Cooperativity is so great that every substituent must be in exactly the right position, or the consequent losses in binding affinity may be catastrophic”. In other words, binding of the transition state analogue must reflect faithfully all of the interactions involved in the actual transition state. PfADA, but not human ADA, accepts 5′-substituents, providing species specificity for these inhibitors (3–6; Figure 8).

Coformycin and 2′-deoxycoformycin are equipotent for bovine, human, and P. falciparum adenosine deaminases. Both compounds are slow-onset, tight-binding inhibitors with dissociation constants of 60–110 pM (Figure 8). The similar inhibitory properties suggest similar transition states for these enzymes, verified by the isotope effect studies detailed below.

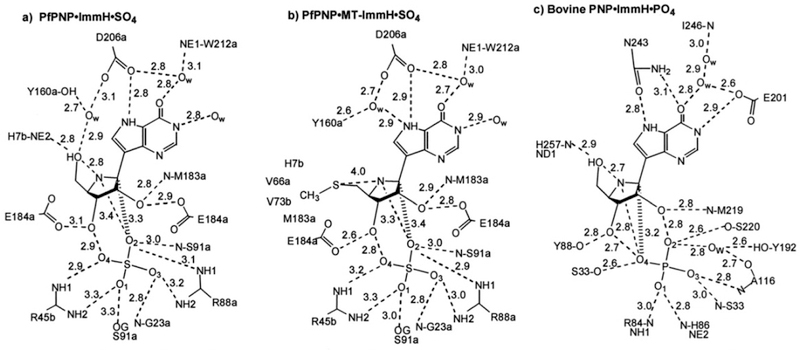

4.4. Adenosine Deaminase Transition State Structures

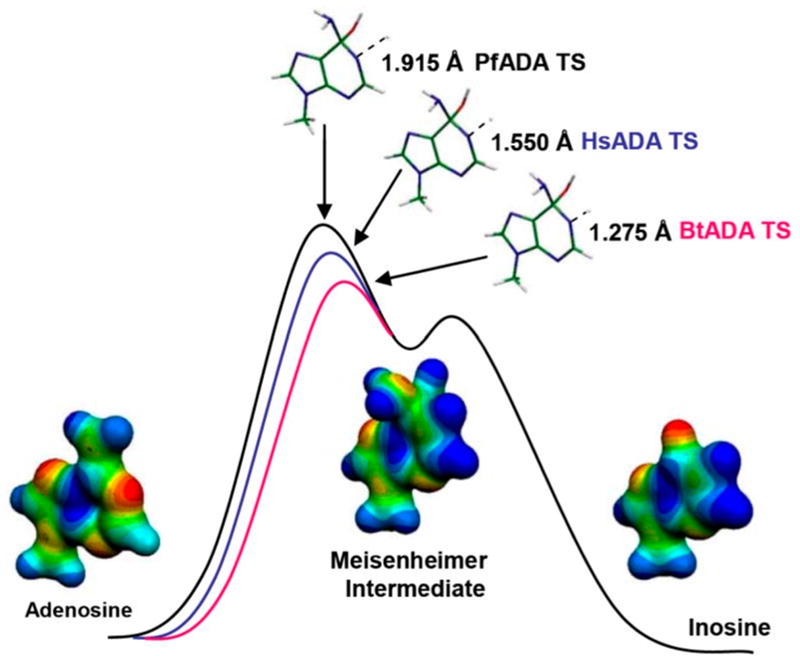

Transition state analysis for the adenosine deaminases compared enzymes from human, bovine, and P. falciparum sources. Kinetic isotope effects were measured for the reaction center at C6, N1, and the exocyclic N6 amino group. All of the enzymes catalyze nucleophilic aromatic substitutions (SNAr transition states) where the essential N1 protonation is partial and the bond order to the attacking Zn2+-activated hydroxyl group is nearly complete. A defining difference for these transition states is the extent to which N1 protonation is complete.71 Transition states for P. falciparum, human, and bovine enzymes have N1–H bond lengths of 1.915, 1.550, and 1.275, respectively, at their transition states. Molecular electrostatic potential maps indicate that all of these transition states are similar in geometry and charge to the coformycins (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Reaction coordinate and transition state structures for the P. falciparum (PfADA), human (HsADA), and bovine (BrADA) transition states with molecular electrostatic potential maps of reactant, transition state, and product. Reproduced from ref 71. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

5. NUCLEOSIDE HYDROLASES

5.1. Biological Function

The nucleoside hydrolases are a broadly distributed family of purine and pyrimidine N-ribosyl hydrolases found in single-cell organisms and plants but not in mammals.72–74 They form free nucleobases and ribose as products. The nucleosidases are found in protozoan parasites that cause human disease including Trypanosoma, Leishmania, and Giardia. They are thought to play a metabolic role by converting host nucleosides into nucleobases for salvage into the metabolic pools of the parasite.75–77 Protozoan parasites are purine auxotrophs, and purine salvage is essential to growth. Nucleoside hydrolases have been identified for all purine ribosides and have been proposed as antiparasitic targets. Targeting purine salvage is complicated by the presence of other purine salvage enzymes that may bypass nucleoside hydrolases.

The nucleoside hydrolases also act as antigens. Circulating antibodies to a Leishmania nucleoside hydrolase (called NH36) is a biomarker for infection. Immunization using this enzyme or its C-terminal fragment as antigens is protective in animal infections.78,79 Transition state analogue inhibitors of the nucleoside hydrolases also show some efficacy against visceral leishmaniasis (L. chagasi) in animal models but with limited knowledge of the mechanism of action.80 Mechanistic information and transition state analogue design for the nucleoside hydrolases has used the enzyme from a nonparasitic protozoan, Crithidia fasciculata, a biological model for Trypanosoma brucei (African trypanosomiasis) and Leishmania species (Leishmaniasis).81–83 The normal host for C. fasciculate is plant-feeding mosquitoes with transmission thought to be through plant-to-insect contacts.84 The nucleoside hydrolase from C. fasciculate (CfNH or IU-nucleoside hydrolase) hydrolyzes all naturally occurring purine and pyrimidine ribonucleosides with similar catalytic efficiencies. Others, for example the protozoan GI-nucleoside hydrolase, strongly prefer 6-oxypurine leaving groups, and the IAG-nucleoside hydrolase from T. brucei prefers these purine leaving groups. In contrast, AMP nucleosidase is specific for adenine, and purine nucleoside phosphorylase is specific for 6-oxypurine leaving groups.85

5.2. Transition State Analogue Design Features

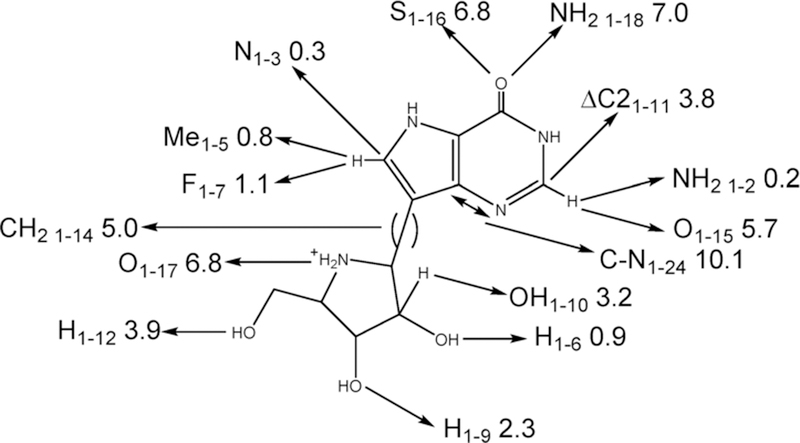

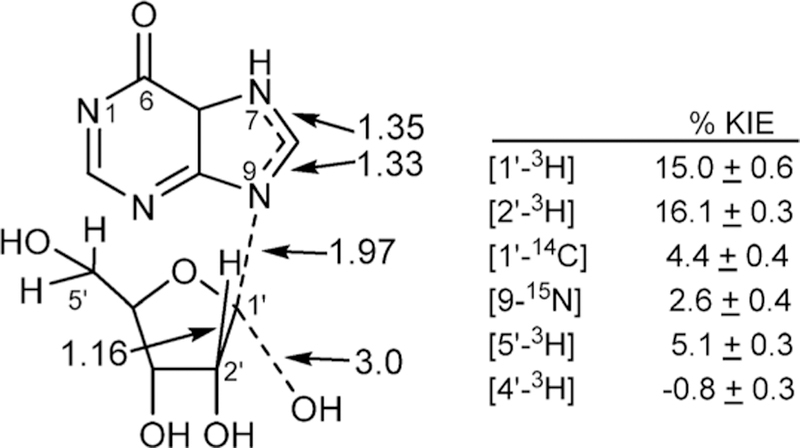

Inhibitor design for the nucleoside hydrolases was initiated from the family of kinetic isotope effects obtained with specific labeled inosine molecules (Figure 10).86 Nucleoside hydrolases permitted extensive measurement of isotope effects and revealed some surprising features of the transition state. The N-ribosidic bond has a Pauling bond order of 0.2 at the transition state as indicated by the 15N9 and 14C1′ KIE values. The water nucleophile has very weak participation at 3 Å and defines an early transition state on an SN1 reaction coordinate. The relatively large α-KIE for 1′–3H confirmed the rehybridized C1′ toward sp2, and an increased out-of-plane mode gives rise to the large isotope effect. Surprisingly, the β-secondary 2′–3H KIE is as large as the α-effect, indicating dihedral orbital overlap (hyperconjugation) between the C2′–3H2 bond and the nearly vacant orbitals of the C1′–N9 bond.41 The remote 5′–3H KIE is a surprising 5.1%, a binding isotope effect associated with the formation of the transition state. The effects are directional such that the collective modes of the C5–3H bonds exhibit more freedom of motion when bound than when in solution. This distortion also affects the nearby C4′–3H bond to give a small inverse isotope effect of −0.8%, indicating a more constrained bond vibrational environment for this atom. A catalytic site hydrogen bond to the 5′-hydroxyl group was proposed to be responsible for the binding isotope effect, a prediction later confirmed by crystallography (see below).

Figure 10.

Kinetic isotope effects and bond lengths(Angstroms)at the transition state of CfNH. The N-ribosidic bond is nearly cleaved, with weak nucleophilic participation to form a partially developed ribocation.

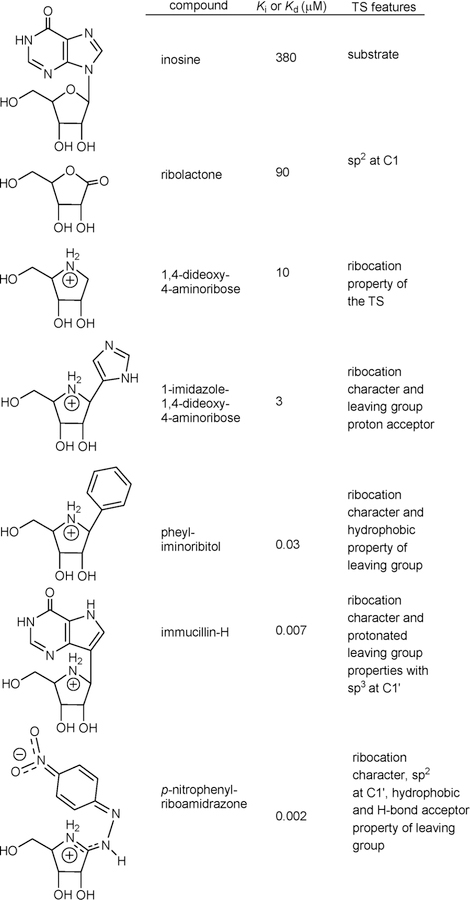

Nucleoside analogues with substituted purine or ribosyl rings are poor inhibitors of CfNH (Ki values of 2–44 mM compared to a Km of 0.38 mM).87 Transition state analogues were designed from the geometry and electrostatic potential maps of the transition state (Figure 11).88 As individual features of the transition state were designed into analogues of the potential inhibitors, Ki values decreased from 380 μM for the substrate inosine by 4-fold for sp2 geometry in ribolactone, 38-fold for the ribocation effect, 120-fold for the ribocation and mimicry of the imidazole, 10 000-fold for the ribocation and a hydrophobic group as a purine analogue, 50 000-fold for the chemically stable immucillin-H incorporating the protonated deazapurine leaving group and the ribocation, and 150 000-fold for the combined sp2 reaction center, ribocation, hydrophobic group, and proton acceptor in the p-nitro group of p-nitrophenyl riboamidrazone. An isotope-edited resonance Raman study of CfNH in complex with the p-nitrophenyl riboamidrazone revealed enzyme stabilization of one resonance state. The p-nitrophenyl group is in the quinonoid form, and the exoribosyl nitrogen bonded to the C1′ of the ribosyl group is protonated, while that bound to the phenyl group is not (Figure 11).89 The zwitterionic tautomer has a distributed cationic charge centered at C1′. The molecular electrostatic potential of p-nitrophenyl riboamidrazone bound to the catalytic site closely resembles that of the transition state.89

Figure 11.

Chemical features of the transition state for CfNH incorporated into candidates as transition state analogues.88

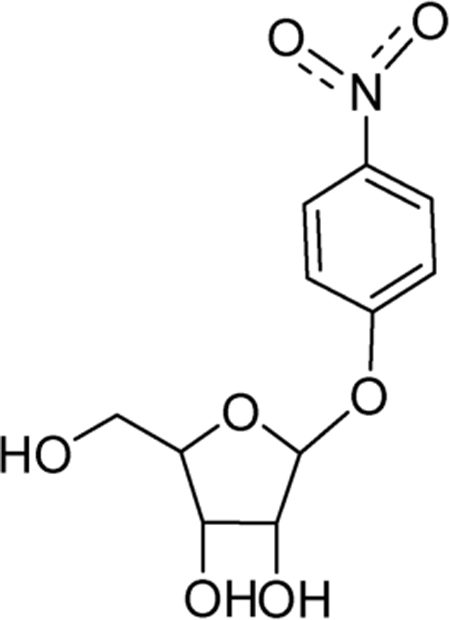

5.3. Nucleosidase Mechanistic Probe Substrate

The transition state of CfNH demonstrated that N7 protonation of the purine leaving group occurs prior to transition state formation.86 The pKa of this group increases as the C1′–N9 ribosidic bond is lost, and transition state analysis does not indicate if N7 protonation is an early or late event with respect to formation of the transition state or if protonation is from a catalytic site proton donor. Substrate specificity studies were designed to test the effects of leaving group protonation on CfNH compared to five additional purine/pyrimidine N-ribosyltransferases (Table 1). Synthesis of p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside and p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside 5′-phosphate provided the test substrates.91 They permit analysis of leaving group activation at the enzyme catalytic sites. If the test enzyme achieves the transition state through protonation of the leaving group, p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside is predicted to be a poor substrate, as the leaving group cannot be additionally activated by protonation. If the test enzyme achieves the transition state through formation of the ribocation or by enforced participation of the nucleophile, p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside will be an excellent substrate, as the p-nitrophenyl leaving group is highly activated. N-Ribosyltransferases use three mechanisms to achieve the transition state: leaving group activation (e.g., protonation of the N7 of purines), formation of the ribocation transition state, and activation of the attacking nucleophile (water in CfNH and phosphate in phosphorolysis reactions). In this analysis the broad-specificity CfNH and LmNH the only excellent catalysts for p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside, indicating its transition state formation occurs by ribocation activation. With inosine as substrate for CfNH, one proton donor and one proton acceptor (pKa values 9.1 and 7.1) are required for catalysis. Hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside shows no required proton donors or acceptors in the pH profiles, appropriate with the activated leaving group. The transition state structure showed weak participation of the water nucleophile, establishing ribocation formation as the primary force for transition state formation in CfNH and LmNH but not for the other enzymes.

Table 1.

Chemical Test of Leaving Group Activation for N-Ribosyltransferases*

| Enzyme | [kcat p-NO2-φ-riboside]/[kcat substrate] | |

|---|---|---|

| CfNH (IU-nucleoside hydrolase)a | 8.5 |  |

| LmNH (IU-nucleoside hydrolase)b | 1.8 | |

| IAG-nucleoside hydrolasec | 0.024 | |

| GI-nucleoside hydrolased | 0.0003 | |

| Purine nucleoside phosphorylasee | 0.000017 | |

| AMP nucleosidasef | 0.000015 | |

| Reactions compared p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside as substrate to a,b,cinosine, dguanosine, and einosine. fp-Nitrophenyl β-D-riboside 5′-phosphate and AMP were compared as substrates for AMP nucleosidase. bLmNH is the enzyme from Leishmania major. Results from reference 89, 90. | ||

5.4. Structural Analysis with a Transition State Analogue

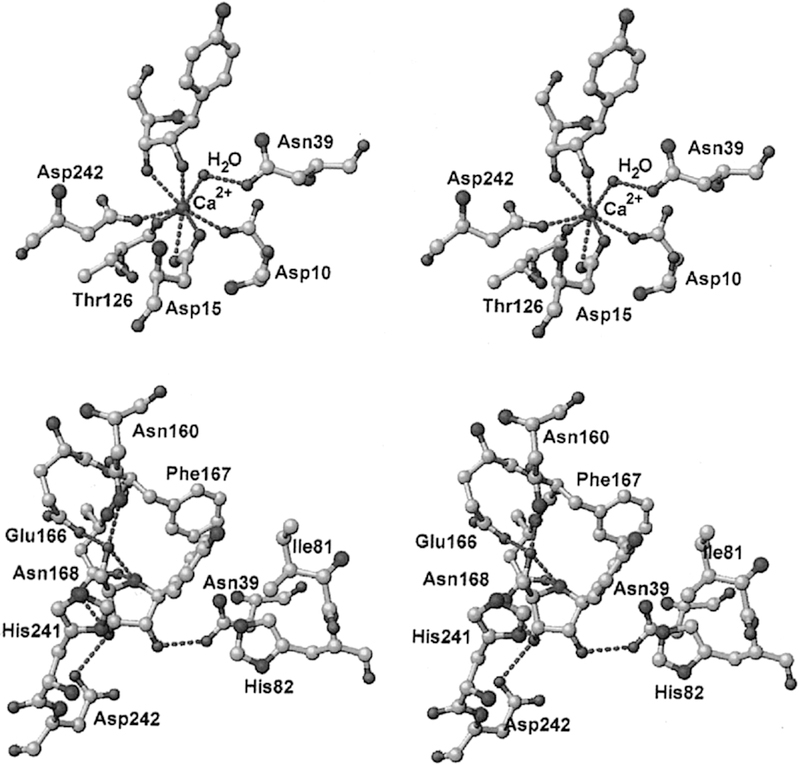

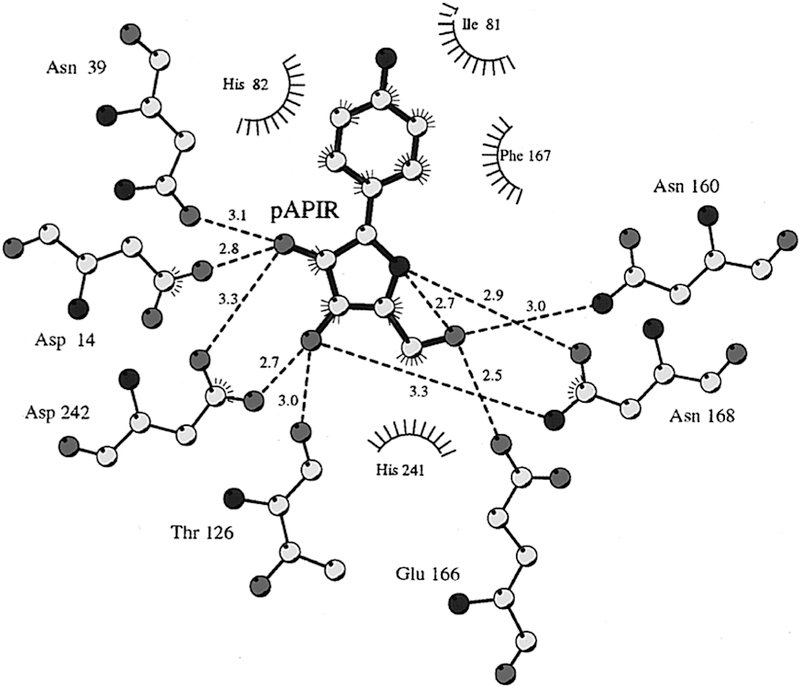

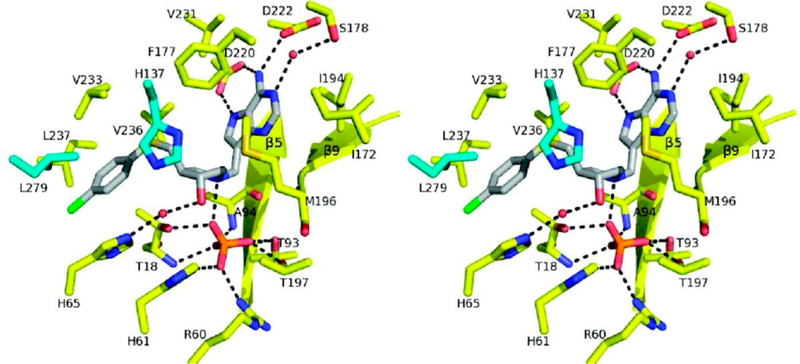

The catalytic sites of NHs have been characterized crystallo-graphically to determine the mechanism of water activation and leaving group proton donor and to explore enzymatic contacts that could be involved in stabilization of the ribocationic transition state.92–95 p-Amino-phenyl-iminoribitol (pAPIR) was used as the catalytic site ligand for CfNH. The transition state analogue is held in proximity to the catalytic water nucleophile. This water is in contact with a tightly bound catalytic site Ca2+ ion (Figure 12). The Ca2+ ion is coordinated to the 2′-and 3′-vicinal hydroxyl groups of the iminoribitol, oxygen atoms from Thr126, Asp242, and Asp10, and both side chain oxygens of Asp15 to complete an octahedral coordination with all contacts at 2.6 Å or less. The Ca2+ copurifies with the enzyme and is sufficiently tightly bound that catalytic assays in the presence of 10 mM EGTA are not inhibitory, although the Ca2+ can be removed by more extensive treatments and can be replaced.96 The water molecule is in favorable geometry for catalysis, 3.2 Å from the carbon analogous to the C1′ anaomeric carbon of normal substrates (Figure 12). Protonation of the leaving group was not an essential feature of the catalytic site, but transition state analysis indicated N7 protonation does occur at the transition state, implying protonation from solvent. The crystal structure shows no candidate ionizable groups near the leaving group pocket, consistent with the leaving group analysis. The KIE analysis of CfNH indicated binding distortion at C5′, an interaction that may be involved in formation of the ribocation. A 2.5 Å strong hydrogen bond between Glu166 and the 5′-hydroxyl group places the 5′-oxygen 2.7 Å from the position corresponding to the O4′-ring oxygen of ribose. Forcing two electron-rich oxygens close together destabilizes the ribosyl group toward the ribocation. This interaction requires anchoring of the ribosyl group, clearly provided by the Ca2+ interaction with both ribosyl vicinal hydroxyl groups together with hydrogen bonds from Asp14, Asp242, and Thr126 (Figures 12 and 13).

Figure 12.

Stereoviews of a transition state analogue bound to the catalytic site of CfNH. Upper panel shows the contacts to the catalytic site Ca2+, and lower panel indicates the contacts to the pAPIR transition state analogue. Reproduced from ref 96. Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

Figure 13.

Distance map for the catalytic site of CfNH with contacts to the catalytic site and pAPIR as a catalytic site ligand. His82 is 3.6 Å from the leaving group and has been considered a potential leaving group proton donor. Note the 2.7 Å neighboring group interaction between O5′ and O4′. Reproduced from ref 96. Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

Transition state analysis for CfNH is summarized by formation of the ribocation by neighboring group interaction between the O5′ and the O4′ oxygens of a tightly tethered ribosyl, no significant leaving group assistance, and ionization of the attacking water nucleophile by a 2.4 Å contact with the Ca2+ ion. The nearby Asp10 acts as a proton acceptor from the water. The reaction is formally a nucleophilic displacement, but the nucleophilic attack lags behind N-ribosidic bond breaking, as the transition state analysis has the water nucleophile at 3 Å in agreement with its crystallographic position (Figures 12 and 13).

5.5. Transition State Specificity for Isozymes

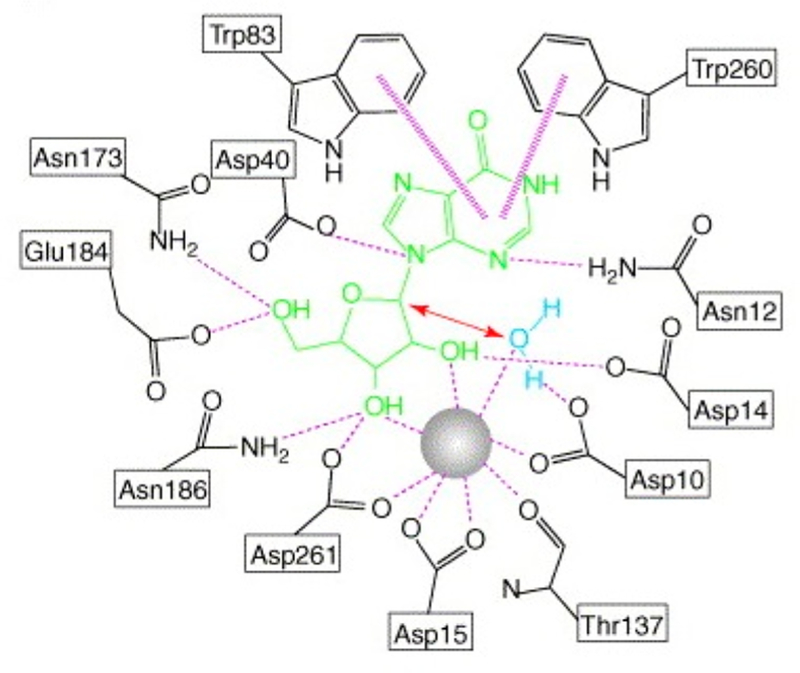

CfNH and LmNH are outliers in the leaving group activation scale (Table 1). In the IAG-nucleoside hydrolase from Trypanosoma vivax (TvNH), leaving group protonation is implicated.97 The catalytic site Ca2+ binding is similar to CfNH, but instead of the weakly interacting groups at the purine/ pyrimidine leaving group site, TvNH has the purine leaving group in a hydrophobic stack with a pair of tryptophan residues, Trp83 and Trp260 (Figures 13 and 14). This interaction is proposed to favor electron donation into the leaving group, raising the pKa to permit protonation by solvent. On the basis of the relative reactivity of p-nitrophenyl β-D-riboside with the nucleoside hydrolases, it is clear that the Trp pair plays a more important role in leaving group activation for TvNH than in CfNH.

Figure 14.

Interaction map for the catalytic site of TvNH with contacts to the catalytic site Ca2+ and inosine as a catalytic site ligand. Asp10Ala mutant prevented hydrolysis of the inosine. Trp83 and Trp260 are stacked with the leaving group. Reproduced with permission from ref 94. Copyright 2006 Elsevier.

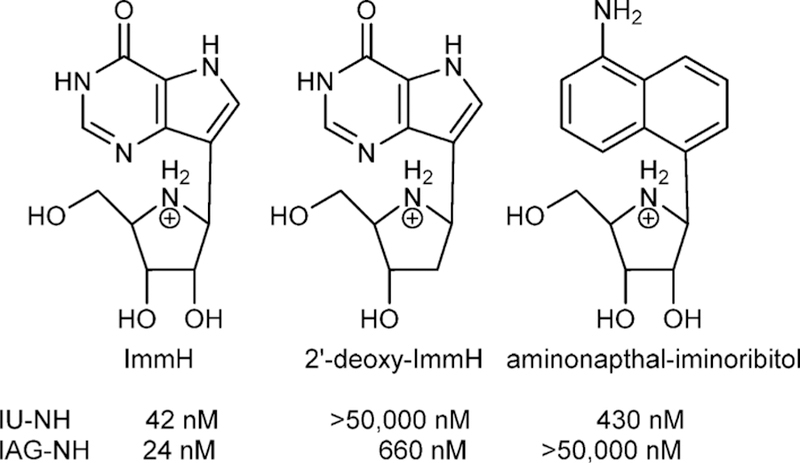

Leaving group interactions are also reflected in transition state analogue specificity. Transition state analogues with a hydrogen-bond pattern of the appropriate purine leaving groups are good inhibitiors of CfNH and TvNH.98 Both CfNH (IU-NH in Figure 15) and IAG-NH bind tightly to ImmH, as both enzymes accept inosine as substrates (hypoxanthine leaving group), to give Kd values of 42 and 24 nM. Loss of the 2′-OH is more detrimental to CfNH (IU-NH) than to IAG-NH, where more of the transition state interaction comes from the leaving group activation. Thus, 2′-deoxy-ImmH binding decreases affinity by >1000-fold for IU-NH but only 27-fold for IAG-NH. In contrast, the leaving group interactions for IAG-NH make binding of the 4-amino-1-naphthalenyl-iminoribitol >2100-fold weaker for IAG-NH but only 10-fold weaker for IU-NH.

Figure 15.

Analogues of the transition states for IU-NH (CfNH) and IAG-NH (TbbNH) demonstrating ribocation and leaving group interaction differences.97,98

5.6. Nucleoside Hydrolases as Drug Targets

Studies using a family of transition state analogues against the bloodstream form of T. brucei brucei indicated that nucleoside hydrolases are not essential.99 RNA interference to inhibit expression of IAG-NH, IG-NH, and methylthioadenosine phosphorylase did not induce purine starvation. Nucleoside hydrolases have provided a thorough understanding of reaction mechanism, transition state structure, reaction coordinate motion, and design of transition state analogues but are not suitable drug targets in the Trypanosoma. Parallel studies with a broader range of protozoan parasites have yet to be completed, but the essential nature of purine salvage appears to have forced the evolution of multiple salvage pathways, making the targeting of a single enzyme a difficult drug design strategy. Each organism has distinct pathways, and in some important parasites, including P. falciparum, there are metabolic steps related to purine salvage that can be used as suitable drug targets (see below).100–102

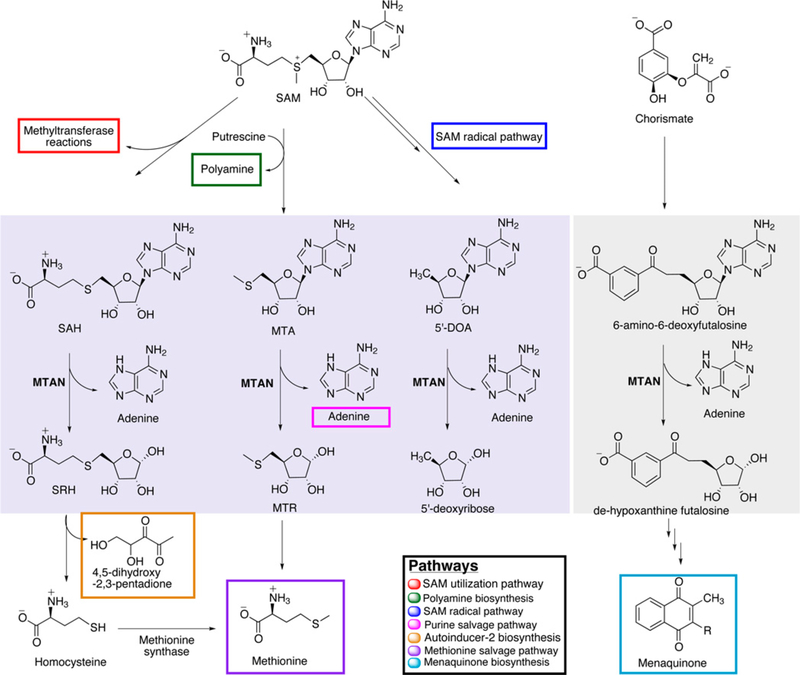

6. BACTERIAL ADP-RIBOSYLATING TOXINS AND THEIR TRANSITION STATES

6.1. Introduction

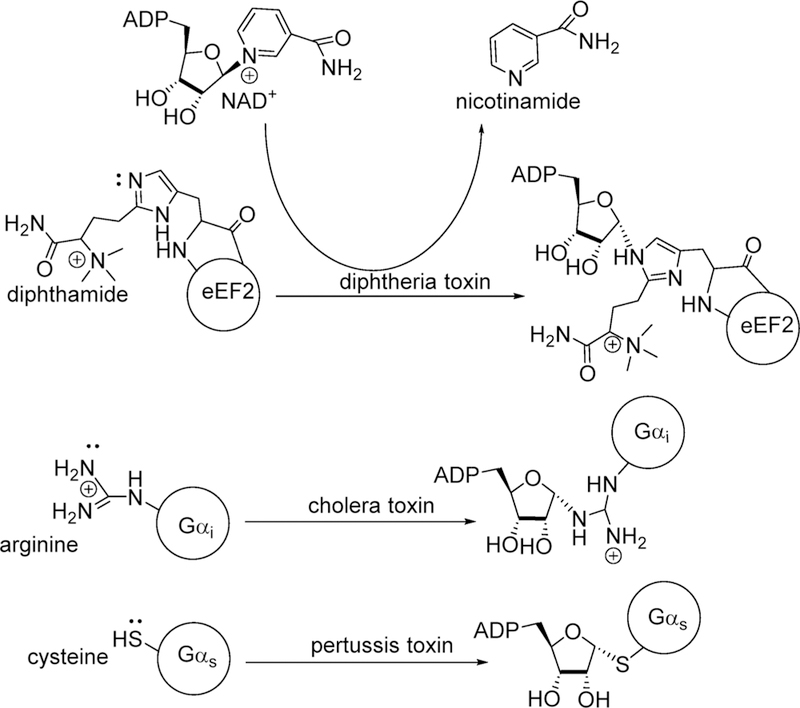

Bacterial toxins are responsible for disease symptoms when invading bacteria are induced to produce the damaging toxins.103–105 Several bacterial toxins work by a common chemical mechanism, the ADP-ribosylation of regulatory G-proteins using NAD+ as an ADP-ribosyl donor. Covalent modification of G-proteins causes loss of function, leading to damage and/or death of affected cells. Cholera, diphtheria, and pertussis toxins are produced by Vibrio cholerae, Bordetella pertussis, and Corynebacterium diphtheria to cause intestinal cholera, whooping cough, and diphtheria.106–108 The bacterial exotoxins disrupt G-protein signaling to cause cell death. The common toxic mechanism for these agents is mono-ADP-ribosylation of specific amino acids in Gsα, eEF-2, and Giα proteins, respectively, by the catalytic A chains of the toxins once they have entered the target cells.109 In the absence of acceptor proteins, these toxins also act as NAD+ N-ribosyl hydrolases. The same NAD+ hydrolytic reaction can be accomplished by nonenzymatic chemical solvolysis providing the opportunity to compare transition state structures of solution chemistry with those formed by enzymes in hydrolase or transferase reactions, Figure 16.110–112

Figure 16.

ADP ribosylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), G-stimulatory protein α, and G-inhibitory protein α by diphtheria, pertussis, and cholera toxins, respectively. Attacking nucleophile atoms are designated by the electrons. Note the inversion of configuration at C1 of the ribosyl group.

6.2. Synthesis of Labeled NAD+ Molecules

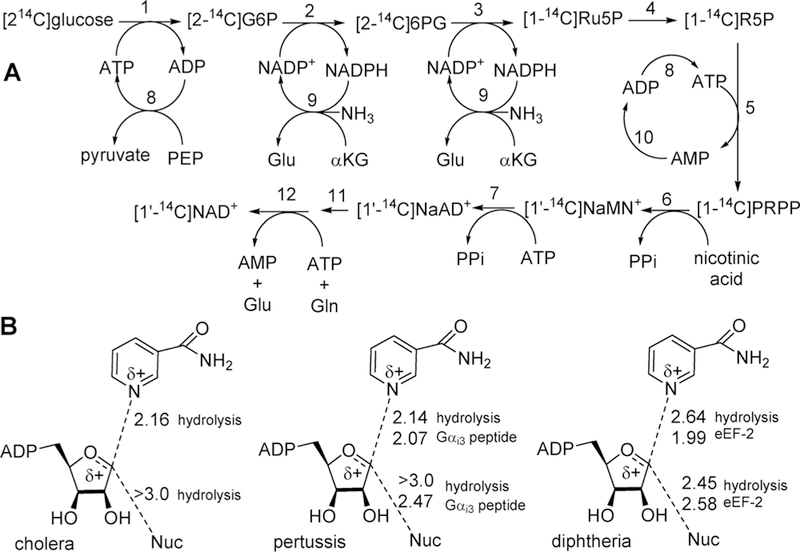

All ADP-ribosylation reactions involve the transfer of the ADP-ribosyl group from NAD+ to yield the ADP-ribosylated receptor protein and nicotinamide. Understanding the transition state structures of the ADP-ribosyltransferases requires kinetic isotope effect analysis from the NAD+ reactant. Isotopic labels are needed in the same positions as indicated for other N-ribosyltranserases. Synthesis of isotopically labeled NAD+ molecules is a parallel approach to the synthesis of labeled ATP and its derivatives (Figure 2). Synthesis of NAD+ proved more challenging because of its relative instability. With care, yields of NAD+ with the desired labels can exceed 90% from the limiting starting isotopic label (Figure 17A).113

Figure 17.

(A) Synthesis of isotopically labeled [1′–14C]NAD+ by coupled enzymatic reactions. Enzymes are (1) hexokinase, (2) glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, (3) 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, (4) 5-phosphoriboisomerase, (5) 5-phosphoribosyl 1-pyrophosphate synthatase, (6) nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase, (7) NAD+ pyrophosphorylase, (8) pyruvate kinase, (9) glutamate dehydrogenase, and (10) adenylate kinase. Single-pot incubation (steps 1–10) converts glucose to NaAd+. Reaction is stopped at step 11; NaAD+ is purified and converted to NAD+ by NAD+ synthetase (12).113 Different labels in the starting glucose or the nicotinic acid added in step 6 provide NAD+ with any desired label in the NMN+ portion of the molecule. From the method of Figure 2, label can be placed at any position in ATP and incorporated into the AMP portion of NAD+ by incorporation at step (B) Reaction coordinate distances for ADP-ribosylating cholera, pertussis, and diphtheria toxins at their transition states as determined by kinetic isotope effect analysis. All distances are in Angstroms. Hydrolysis refers to the toxin-catalyzed solvolysis of NAD+ in the absence of the protein nucleophile ADP-ribosylation acceptor. All of these toxins catalyze NAD+ solvolysis. ADP-ribosyl transferase activity to Gαi3 peptide for pertussis toxin is to the C20-terminal peptide in which transfer occurs to Cys at amino acid 4 of the peptide. ADP-ribosyl transferase to eEF-2 used full-length eEF2 isolated from baker’s yeast.

6.3. Cholera Toxin

The slow hydrolysis of NAD+ (kcat= 8 min–1) catalyzed by cholera toxin in the absence of the Gαi protein has been studied to characterize the hydrolytic transition state.114 Kinetic isotope effects support an asymmetric, dissociative transition state with the bond to the leaving group nicotinamide nearly broken (2.16 Å) and even weaker participation of the attacking water nucleophile at >3.0 Å (Figure 17B). The ribocationic transition state generated a large, normal KIE of 18.6% from [1′–3H]NAD+, indicating increased out-of-plane modes. Small KIEs are anticipated from [1′–14C]NAD+ in a dissociative mechanism, and the value of 3% is consistent with low remaining bond order to the leaving group. Water is not the preferred nucleophile for this reaction, and it is not surprising that its participation is not enforced with a distance of >3.0 Å at the transition state. Despite the remote location of the water nucleophile, it is a specific interaction, as methanolysis does not occur with the reaction enforced by cholera toxin.

6.4. Pertussis Toxin

Isotope effect experiments with pertussis toxin were designed to compare the nature of the transition states formed by the enzyme in the absence (hydrolytic reaction) and presence of the thioate nucleophile from the Gαi3 protein.115,116 The toxin is active with the N-terminal 20 amino acids of the G-protein, where the nucleophilic thioate anion is 4 amino acids from the N-terminal. The KIE values and the transition state for the hydrolysis reaction catalyzed by pertussis toxin were similar to that for cholera toxin (Figure 17). When the nucleophile from the G-protein peptide is present, the KIE values are altered. Thus, the KIE for [1′–14C]NAD+ changed from 2% for hydrolysis to 5% for ADP-ribosyl transfer to the Cys nucleophile. Transition state analysis indicated an earlier transition state with the C1′ to N1 leaving group decreasing from 2.14 to 2.07 Å and the attacking nucleophile also demonstrating increased participation at the transition state, increasing from >3.0 Å for hydrolysis to 2.47 Å for the attack of the thioate nucleophile (Figure 17). Contacts at the enzyme catalytic site in the ternary complex are more optimized, with improved activation of the leaving group and increased participation of the peptide nucleophile.

6.5. Diphtheria Toxin

The nucleophile targeted for ADP-ribosylation by diphtheria toxin is a post-translationally modified histidine in eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF-2) called diphthamide (Figure 15).117 The transition states for hydrolysis of NAD+ and ADP-ribosylation of eEF-2 by diphtheria toxin are similar to those for cholera and pertussis toxins by being dissociative with strong ribocation character at the transition state and by becoming earlier in the presence of the protein nucleophile.118,119 In the case of diphtheria toxin, the transition states were determined for the hydrolytic reaction and full-length eEF-2 isolated from bakers yeast.120 Increased nucleophile participation at the transition state is apparent in the primary KIE values. For the hydrolytic reaction, the [1′–14C]NAD+ KIE was 3.4% and increased to 5.5% for ADP-ribosylation of eEF-2. Analysis of these and other isotope effects indicated a weak bond of 2.64 Å to the leaving group at the hydrolysis transition state, changing to 1.99 Å in the presence of eEF-2. The main effect is on leaving group activation, as the water and diphthamide nucleophiles are at similar distances of 2.45 and 2.58 Å, respectively, at the transition states. This difference has been speculated to be caused by activation of the nicotinamide group from a decreased dielectric of the leaving group pocket.

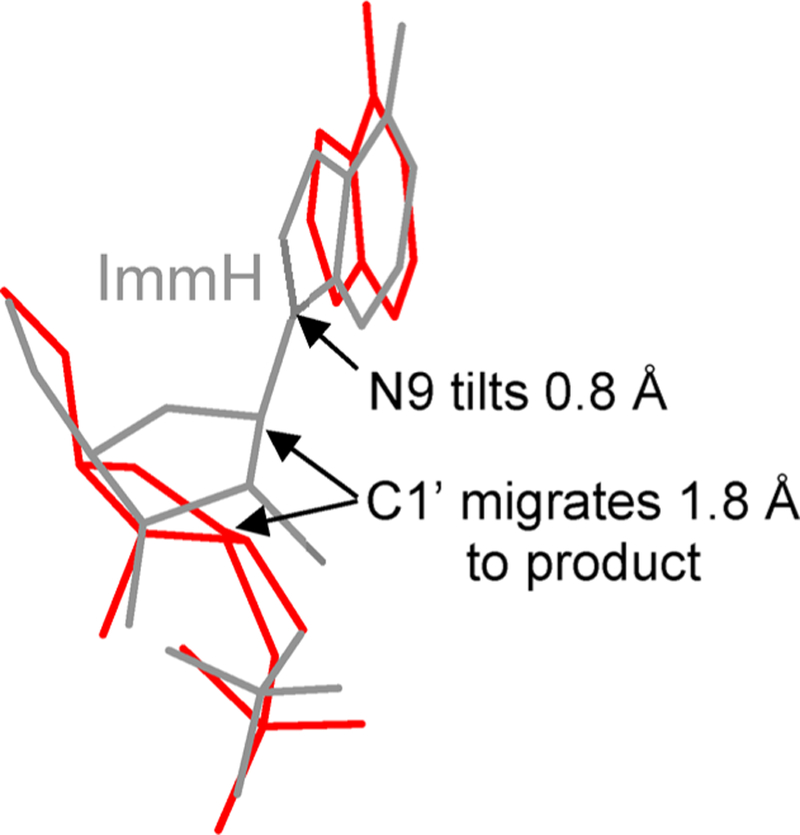

6.6. Nucleophilic Displacement by Electrophile Migration

Transition state analysis from KIEs yields a two-state comparison between reactant and transition state, with no information about intervening or following chemical steps.121 However, it is of interest that in many N-ribosyltransferases the transition states are similar with low Pauling bond order to the leaving group and even lower bond order to the attacking nucleophile. In these mechanisms, the leaving group and the nucleophile are relatively fixed by the enzymatic architecture during the reaction coordinate. Enzymatic interactions generate the ribocation and the C1′ anomeric carbon migrates 1.8–2.1 Å between the leaving group and the nucleophile.122–125 Crystallographic evidence from reactants, transition state analogues, and products at the catalytic sites of these enzymes also supports the anomeric carbon migration. The mechanism has been termed “nucleophilic displacement by electrophile migration” based on the chemical formality of nucleophilic displacement evidenced by the inversion of configuration, with the electrophile migration referring to the excursion of the ribocation between the leaving group and the nucleophile. An interesting point for the electrophile migration mechanism in the context of the ADP-ribosylating toxins is that it permits a wide variation of pKa values between the leaving group and the nucleophile. These asymmetric transition states permit formation of highly reactive ribocations that will react with nucleophiles of different chemical reactivity. For the NAD+-based ADP ribosyltransferases discussed here, the nucleophile diversity includes water, Arg, Cys, and diphthamide. In other enzymes it includes the N1 of adenosine in CD38, the N1 of ATP in the ATP-phosphoribosyltransferase, and carbonyl oxygens in the Sirtuins.126–128 This concept will be revisited in the phosphorylase reactions of section 12.

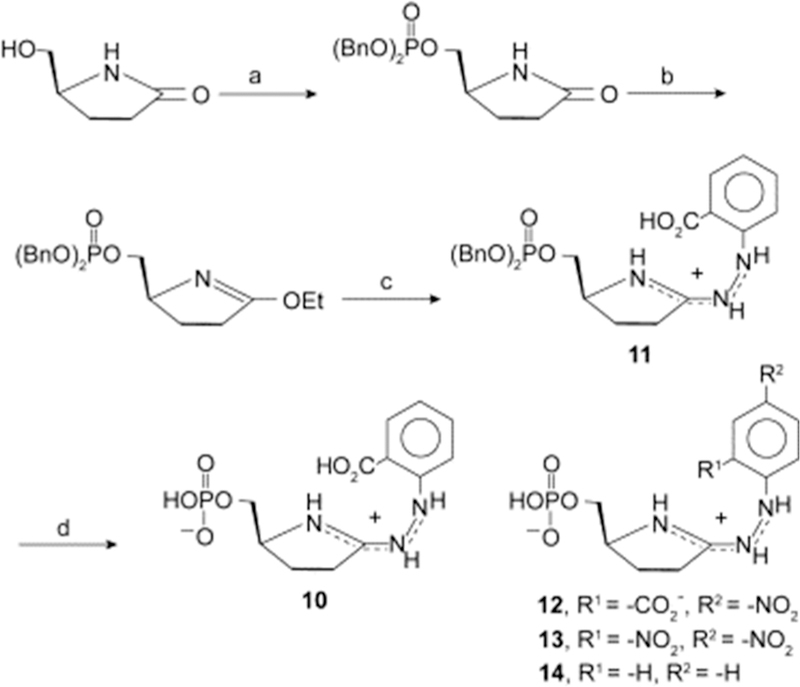

6.7. Transition State Design for ADP-Ribosylating Toxins

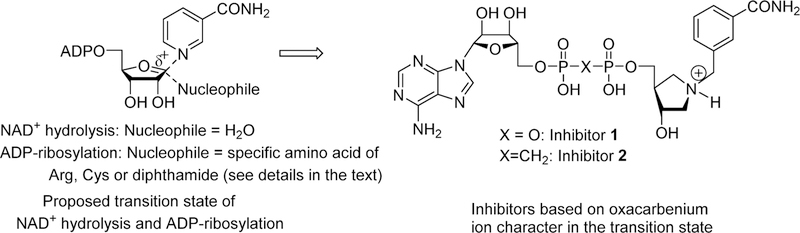

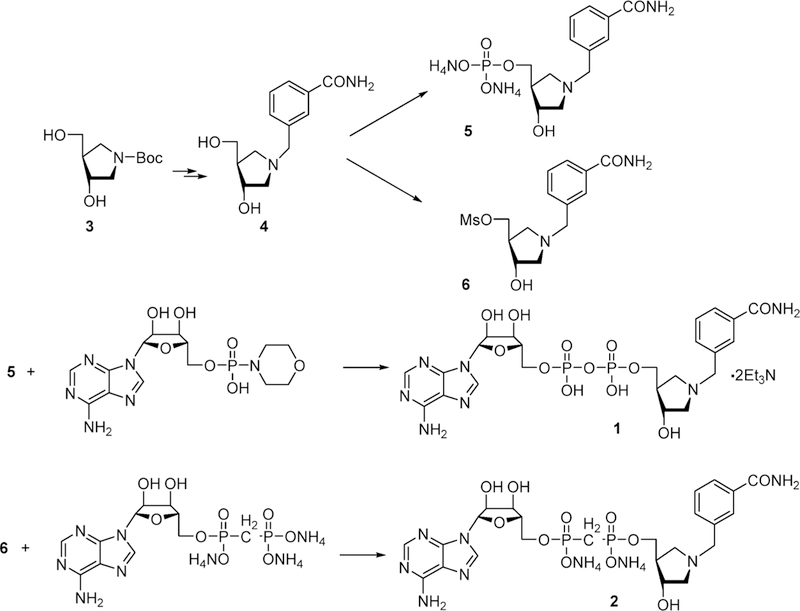

The transition states of ADP-ribosylating toxins share common features of a nicotinamide leaving group approaching neutral charge as the N-ribosidic bond breaks, a ribocation, and a long bond between the ribocation and the leaving group. In all cases, the participation of the nucleophile is weak. It was hypothesized that transition state analogues might be synthesized with similar characteristics to mimic these transition states (Figure 18.).129

Figure 18.

Design of transition state analogues for ADP-ribosylating cholera, pertussis, and diphtheria toxins. Features of the ribocation are provided by the hydroxypyrrolidine, a long bond to the leaving group is provided by the methylene bridge, and recognition elements of the carboxamide group are retained.129

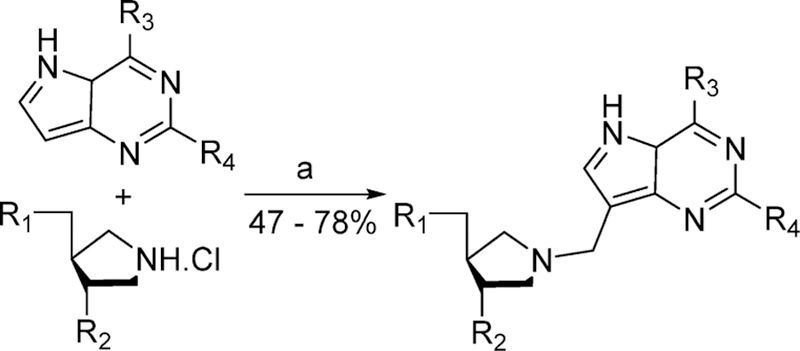

6.7.1. Inhibitor Synthesis.

Potential inhibitors were synthesized using the strategy of Figure 19. Although ADP-ribosylating toxins, phosphorylases, and nucleoside hydrolases all proceed through ribocation transition states, transition state analogue affinities are proportional to the enzyme-enforced rate enhancements according to the Wolfenden proposal.3,4 Transition state analogue design may be challenging for the ADP-ribosylating toxins because of the relatively small k /k ratio and the relatively weak binding of the NAD substrate. In the nucleoside hydrolases, rate enhancements are estimated to be around 1012, while for NAD+ hydrolysis and ADP-ribosylation, enhancements are 3–6 orders of magnitude smaller at 106–109. These considerations raised concern that even though transition state analysis provides novel insight to catalysis poor catalysts may resist efforts to design tight-binding transition state analogues.

Figure 19.

Chemical synthetic scheme for 3-hydroxypyrrolidine transition state analogues for ADP-ribosylating cholera, pertussis, and diphtheria toxins.129

6.7.2. Cholera Toxin Inhibitors.

Inhibitors 1 and 2 (Figure were tested as potential transition state analogues against cholera, pertussis, and diphtheria toxins for both the NAD+ hydrolytic reaction and the ADP-ribosylation reactions.129 Cholera toxin binds NAD+ with a Km value of 10.8 mM for the hydrolytic reaction. Inhibitors 1 and 2 gave Ki values of 17.4 and 32.7 μM, respectively. Therefore, they give Km/Ki values of 620 and 330 relative to NAD+. Although these are impressive ratios, suggesting capture of transition state features, the relatively high Km values for NAD+ make the absolute inhibition constants rather modest compared to the nanomolar inhibitors described above and the picomolar to femtomolar constants to be discussed below. In the presence of O-methyl-arginine as an ADP-ribosyl group acceptor, the Km value for NAD+ decreased to 4.7 mM and inhibitors 1 and 2 also bound tighter at 10.9 and 23.6 μM, respectively, to give Km/Ki values of 431 and 200 relative to NAD+. The ribocationic character of the 3-hydroxypyrrolidine analogues apparently generates binding affinity because of their similarity to the transition state. However, the catalytic activity of cholera toxin for hydrolysis and transfer to O-methyl-arginine is slow, at 8.7 and 20.0 min–1, providing a limited kcat/kchem target for tight binding of transition state analogues. The cholera toxin system deserves additional study with these inhibitors, as the Km values for NAD+ in this in vitro system are unlikely to be functional in vivo, where other activating factors are known to interact with cholera toxin for catalytic activation.130–132 Increased catalytic function is likely to enhance the interaction of transition state analogues.

6.7.3. Pertussis Toxin Inhibitors.

Pertussis toxin binds NAD+ with a Km value of 19 μM for the hydrolytic reaction.115,129 Inhibitors 1 and 2 gave K values of 24.4 and 39.7 μM, respectively. Therefore, they give Km/Ki values of 0.78 and 0.48 relative to NAD+. The relatively low Km value for NAD+ makes these micromolar inhibition constants near equivalent when compared to the binding of substrate. Additional studies are needed to design effective transition state analogues for pertussis toxin, as there are no reports of inhibitiors for the ADP-ribosylation of G-protein inhibitory peptides or for reaction with the intact Gαi3 protein. Surprisingly, the ribocationic character of the 3-hydroxypyrrolidine analogues does not contribute to binding as transition state analogues in the case of in vitro action of pertussis toxin. Synthesis and testing of the iminoribitol analogues of 1 and 2 (Figure 19) would add information relative to the 2-hydroxyl group and placement of the ribocation mimic.

6.7.4. Diphtheria Toxin Inhibitors.

Diphtheria toxin gives a Km value of 85 μM for the hydrolysis of NAD+ and a slow reaction of 0.11 min−1.133 Diphtheria toxin is much more active for diphthamide ADP-ribosylation of yeast eEF-2, increasing the reaction rate 1650-fold to 182 min−1.134 Inhibitors 1 and 2 (Figure 19) gave Ki values of 48.2 and 32.9 μM, respectively, for the hydrolysis of NAD+, slightly better inhibitors than NAD+ is a substrate. They give Km/Ki values of 1.8 and 2.6 relative to NAD+. The Km value for NAD+ decreases to 6 μM in the presence of eEF-2, but the Ki values for inhibitors 1 and 2 do not decrease in proportion with Ki values of 30.5 and 19.1 μM, respectively. Therefore, the Km/Ki values are 0.2 and 0.3 for the inhibitors relative to NAD+. Transition state analogues are anticipated to exhibit increased binding as the reaction rate increases, a property not seen with diphtheria toxin. No other transition state analogues have been explored for this toxin, although there are reports of inhibition of uptake by amine compounds and semicarbazoles.135–137

Because catalytic rate enhancements by the bacterial exotoxins are small, transition state analogues do not capture large energies of activation.129 Although Km/Ki values are large for cholera toxin, the weak binding of NAD+ results in rather weak (micromolar) affinities for the putative transition state analogues. In the cases of diphtheria and pertussis toxins, the transition state analogues bind with approximately the same affinity as substrates, suggesting modest transition state stabilization. Additionally, diphtheria and pertussis toxins may catalyze ADP-ribosyl transferase reactions from ground state destabilization by increasing the activation of the already activated nicotinamide leaving group while making the ADP-ribosyl receiving nucleophile the nearest reactive atom to capture the ribocation formed by nicotinamide loss. Although the original goals of transition state analogue design to block toxin action have not been accomplished, the transition state analysis of three ADP-ribosylating toxins establishes the mechanistic features of their transition states.

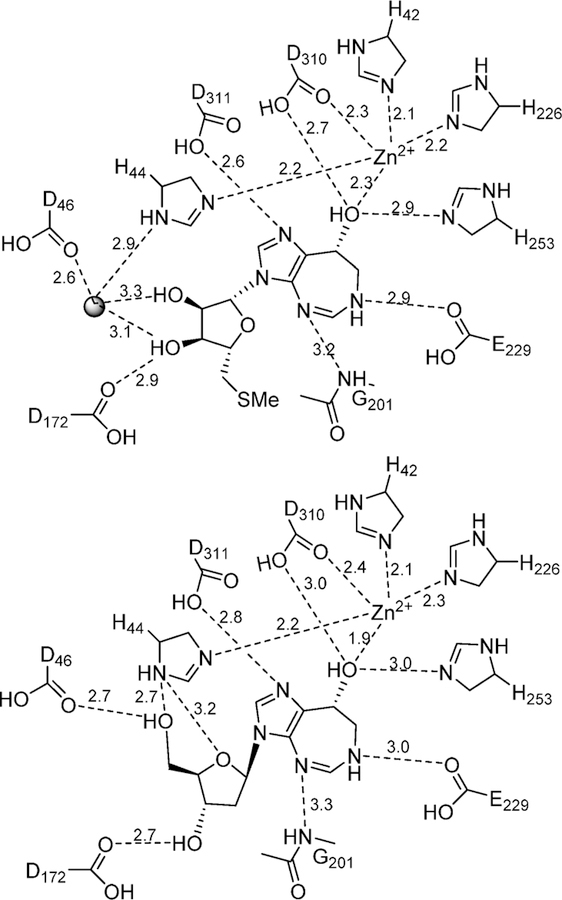

7. RIBOSOME-INACTIVATING PROTEINS

7.1. Ricin A-Chain

Among the most toxic of all natural products are the plant-derived ribosome-inactivating proteins, typified by ricin.138–140 The notoriety of ricin as a toxin was enhanced when the KGB used it to assassinate the Bulgarian dissident and defector Georgi Markov at a bus stop in London in 1976.141–143 Ricin is composed of a membrane-penetrating B-chain and a catalytically active A-chain. The subunits are linked by disulfide bonds that are reduced as the AB-toxin complex travels from the membrane by retrograde transport to the golgi and the cytosol where the reduction of disulfide bonds releases the catalytically active ricin A-chain.144 Its physiological substrate is functional eukaryotic ribosomes where it hydrolyzes a single adenine by base excision from the ricin–sarcin loop of 28 S rRNA (position 4324 in rat rRNA).145,146 Adenine depurination from the 5′-GAGA-3′tetraloop modifies the binding site for eEF-2 and destroys the catalytic function of the ribosome. The A-chain of ricin has been linked to antibodies that recognize specific cancer cell types.147–150 Delivery kills the target cancer cells, but the efficacy of this therapy is limited by toxic side effects of ricin A-chain that remains in the circulation and/or is released from cancer cells undergoing toxin-induced cell death.151–153 Transition state analogue, inhibitors of ricin A-chain could be used as rescue agents to prevent circulating ricin A-chain from causing cell lysis in the vascular bed.

7.1.1. Ricin A-Chain Transition State Structure.

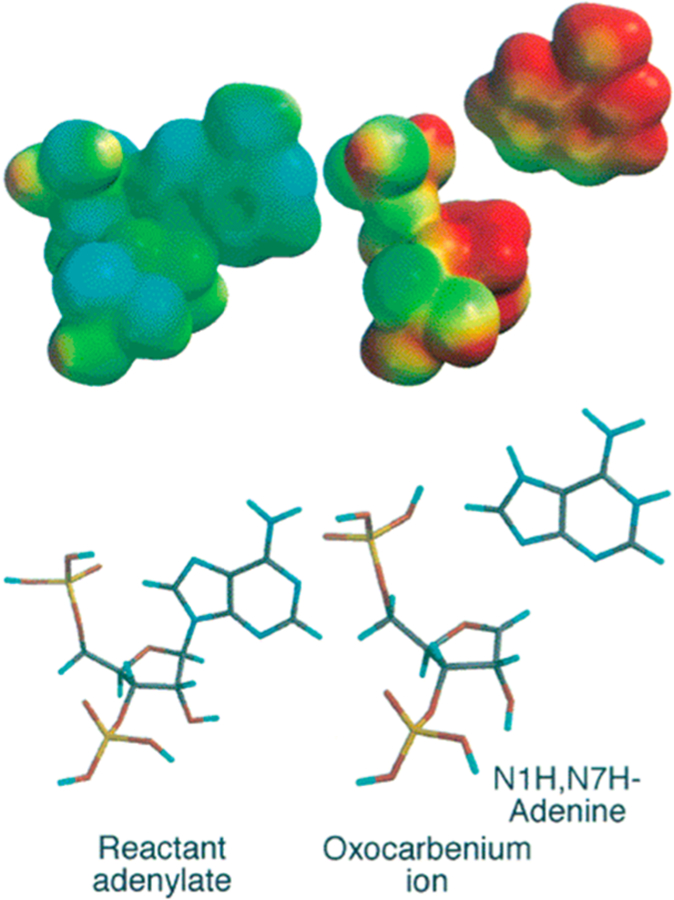

Kinetic isotope effects on the hydrolysis of a small 10mer stem– tetraloop oligonucleotide substrate with isotopic labels incorporated specifically into the target adenine (bold) of the 5′-CGCGAGAGCG-3′ stem loop established the mechanism of the reaction as DN*AN, with a ribocationic, highly dissociative transition state (Figure 20).154 Small stem–loop DNA structures are also substrates, and KIE measurements with the same sequence of DNA altered the KIE values, but the reaction stayed within the general description of the DN*AN mechanism.155

Figure 20.

Transition state structure of ricin A-chain acting on stem– loop RNA at pH 4.0. (Upper left) Reactant adenylate electrostatic potential at the van der Waals surface. (Upper right) Transition state electrostatic potential showing fully dissociated adenine. Reproduced from ref 154. Copyright 2000 American Chemical Society.

7.1.2. Inhibitor Design and Synthesis for Ricin A-Chain.

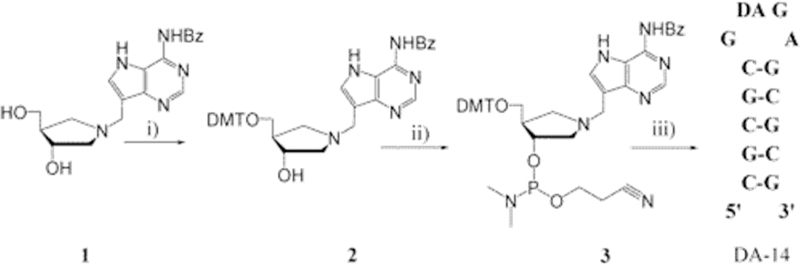

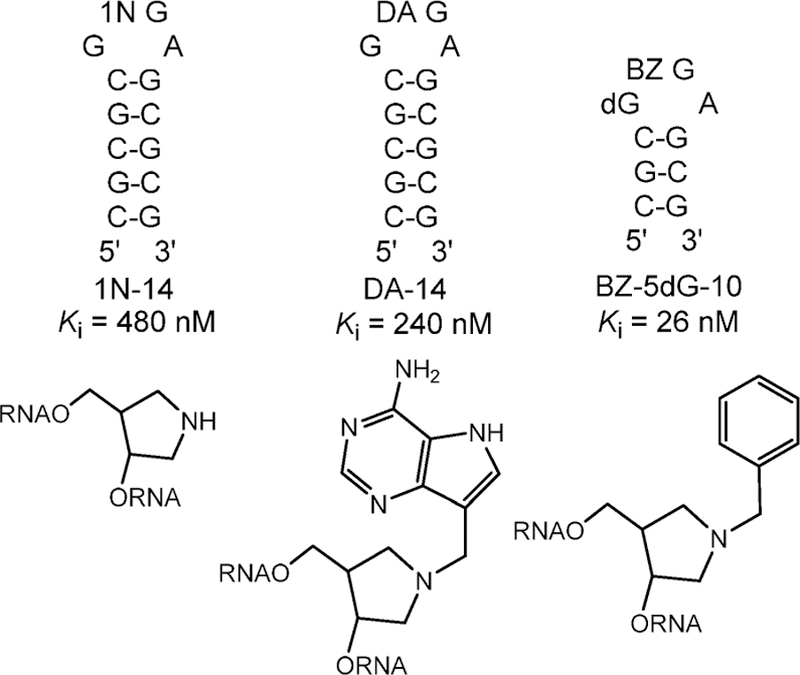

Inhibitors were designed and synthesized to mimic the stem–loop substrate. Alterations toward the transition state included replacing the substrate adenylate with a hydroxypyrrolidine mimic of the ribocation in an N1′-methylene bridge to 9-deazaadenine placed at the depurination site in tetraloops of varied length (Figures 21 and 22).156,157 An abasic, 14mer construct inhibited ricin A-chain with a Kd of 480 nM (1N-14, Figure 22). Filling the catalytic site with adenine improved binding of IN-14 to 12 nM, demonstrating the benefit of the adenine in combination with the transition state ribocation mimic.158 A stem–tetraloop inhibitor was synthesized that incorporates a methylene-bridged hydroxypyrrolidine (1-a zasugar mimic, namely, (3 S,4 R )-3-hydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidine) to a 9-deazaadenyl group to mimic the N7-protonated leaving group at the transition state (Figure 21). The 240 nM inhibition constant for the 9-deazaadenyl 14mer (DA-14) was improved to 26 nM in a construct with a phenyl-substituted inhibitor with a 2′-deoxyguanosine-nucleoside placed 5′ to the depurination site (Figure 22). This molecule is the tightest binding inhibitor reported for ricin A-chain. Important features of these molecules are their ribocation mimics and the increased pKa at N7 of the adenine leaving group, both properties of the transition state. The phenyl-substituted molecule combines the ribocation mimic with a planar hydrophobic substituent replacing the adenine leaving group, suggesting a complimentary hydrophobic feature at the leaving group pocket.

Figure 21.

Synthetic route to hydroxypyrrolidine transition state analogues of ribosome-inactivating proteins: (i) DMTrCl (1.5 equiv), DMAP (catalytic), (iPr)2NEt (2 equiv), pyridine, room temperature, 5 h; (ii) 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite (2.5 equiv), 2,4,6-collidine (2.5 equiv), 1-methylimidazole (1 equiv), methylene chloride, 0 °C, 30 min; (iii) Expedite DNA/RNA synthesis system. Reproduced from ref 156. Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society.

Figure 22.

Transition state analogue inhibitors of ricin A-chain. 1N, DA, BZ, and deoxyG (dG) inserts into the stem–loop structures replace adenosine at the depurination site for the reaction and are shown below the respective stem loops.159

7.1.3. Structure of Ricin A-Chain with a Transition State Analogue.

The value of hydrophobic interactions at the catalytic site only became apparent when the crystal structure of ricin A-chain was solved with a covalently circularized stem– loop transition state analogue at the catalytic site (Figure 23).160,161 Ricin A-chain structures with fragments or single nucleotides at the catalytic site did not induce the full architecture revealed by the transition state analogues.162–166 The adenine leaving group is sandwiched between two tryosine groups. The nearby Arg has the effect of favoring protonation of the adenine leaving group. The results of these mechanistic, transition state, inhibitor design, and structural studies made ricin A-chain the best-understood ribosome inactivation protein. In vitro, the ricin A-chain has an unusual pH optimum of pH 4.0 and is nearly inactive at pH 7. The KIEs and transition state analysis were conducted at pH 4.0. Inhibitors functioned well as stem–loop RNA competitors at low pH but did not bind to the enzyme at physiological pH values. The inhibitors did not protect rabbit reticulocyte ribosomes from ricin A-chain inactivation under physiological conditions evaluated by protein translation assays.

Figure 23.

Catalytic site contact maps of ricin A-chain (A) and saporin L3 (B) with a cyclic transition state analogue inhibitor bound to the active sites. Purines and catalytic site groups involved in π-stacking are in orange. Water molecules are drawn as red dots. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines (green). Hydrogen bonds are in Angstroms. Reproduced with permission from ref 161. Copyright 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

7.2. Saporin L3

A screen of other ribosome-inactivating proteins that might be susceptible to inhibitors designed for ricin A-chain led to the development of saporin L3, a poorly understood leaf form of a ribosomal-inactivating protein from Soapwort plants and earlier known as saporin L1.167–169 Other isozymes of saporin, especially saporin-6, have been used as a toxic agent in antibody-targeted toxin therapy. Saporin L3 was found to be a superior agent in its catalytic action on mammalian rRNA and as a target for the development of transition state analogues as rescue agents.169–172 Characterization of saporin L3 demonstrated it to be a promiscuos RNA adenine depurinating enzyme.173,174 In addition to depurinating ribosomes and rRNA, saporin L3 catalyzed the depurination of adenines in the GAGA tetraloop of short sarcin–ricin stem–loops and multiple adenines within eukaryotic rRNA, tRNAs, and mRNAs. The transition state structure of saporin L3 was solved in experiments similar to those used for ricin A-chain, except that the stem–loop RNA substrate (5′-GGGAGGGCCC-3′) contained only a single A to prevent multiple depurinations in kinetic isotope effect experiments.175

7.2.1. Saporin L3 Transition State.

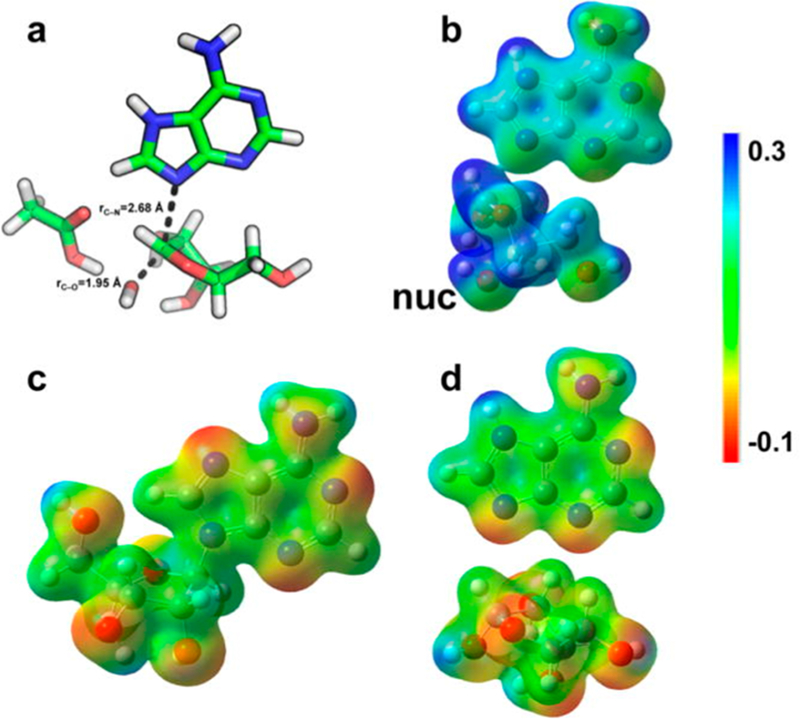

Despite catalysis of the same reactions and homology in ricin A-chain and saporin (30% identical), the transition states differ. Intrinsic kinetic isotope effects are a direct reflection of the environment at the transition states. Thus, the intrinsic 1′–14C KIE for the ricin A-chain-catalyzed depurination of RNA was 0.993, indicating a completely dissociated adenine leaving group with no significant participation of the attacking water nucleophile.154 The intrinsic primary 1′–14C KIE for saporin L3 depurination is 1.052, less than expected for a fully developed SN2 mechanism, where the 1′–14C KIE value can be as large as 1.14.175–177 The smaller α-secondary hydrogen KIEs of 1.045 for saporin L3 compared to 1.163 for ricin A-chain also indicates a transition state with less dissociative character. Where does the bond order reside in the saporin L3 transition state? The 9–15N KIEs report on the degree of N9-ribosyl bond breaking. The KIE values indicate a fully broken C–N bond at both TSs. Therefore, the attacking water nucleophile contributes to the bond structure of the transition state more in saporin L3 than in ricin A-chain. It is located 1.95 Å from the anomeric carbon of the adenine depurination site (Figure 24). The nucleophilic water is well defined in the crystal structure of saporin L3 with a transition state analogue.161 The crystallographic water nucleophile is held in position by two 2.5 Å hydrogen bonds to a carboxylate oxygen of Glu174 and the carbonyl oxygen of Glu206 and is positioned 3.1 Å from the reaction center.

Figure 24.

Transition state geometry, electrostatic potential surface (EPS), and NBO charges for the reaction of saporin L3. Transition state geometry (a), EPS values for transition state (b), reactant (c), and products (d) are shown. nuc is the nucleophilic water. Reproduced from ref 175. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

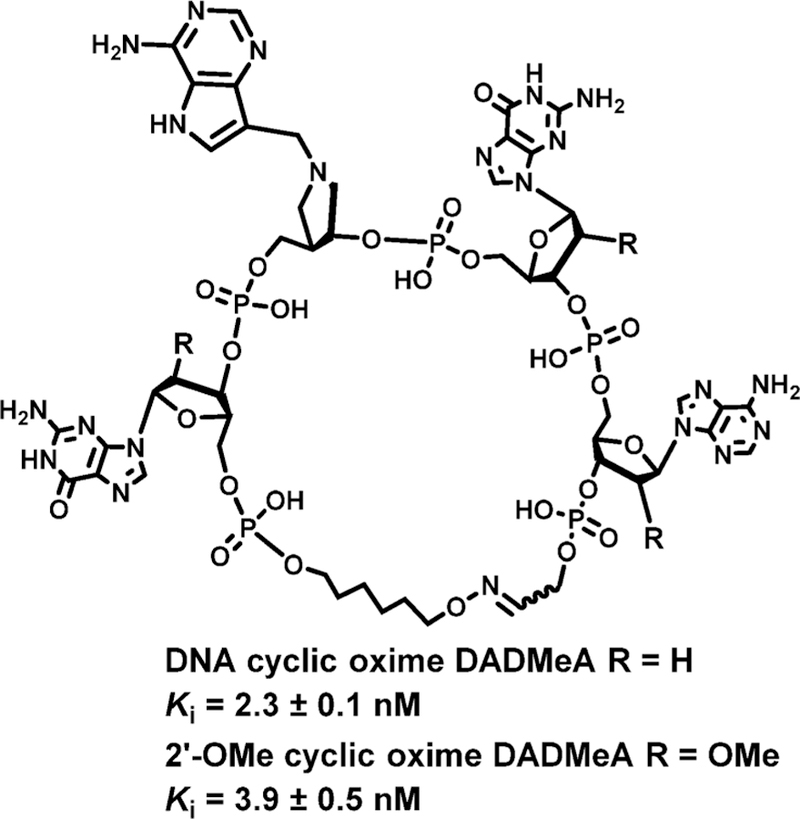

7.2.2. Saporin L3 Inhibitor Design.

Transition state analogues developed to mimic the ricin A-chain transition state were used as a starting point for design of inhibitors for saporin L3. Although the transition states differ in detail, they share ribocation character, leaving group protonation, and specificity for the RNA scaffold. The inhibitor cocrystallized with ricin A-chain and saporin L3 was a four-base cyclic, covalently closed RNA construct. Instead of the RNA stem, the RNA tetraloop mimic was closed with a cyclic oxime linker and contained a transition state analogue at the adenylate depurination site.160 Both DNA and O2′-methylated RNA versions were synthesized. With dissociation constants at 2.3 and 3.9 nM, these are the highest affinity inhibitors reported for saporin L3 (Figure 25). The inhibitors act on purified saporin L3 at physiological Ph and also protect rabbit reticulocyte ribosomes against inactivation by saporin L3 at concentrations consistent with their nanomolar dissociation constants (see below).178

Figure 25.

Transition state analogues for saporin L3. Structure is covalently closed and O2′ protected from RNases. It provided a scaffold for A of both ricin A-chain and saporin L3 (Figure 23).178

It is of interest to compare the electrostatic potential surfaces for the saporin L3 transition state to that of a small, linear transition state analogue construct of two backbone links with a transition state analogue linked to a protected guanosine group, a 3.3 nM inhibitor (Figure 26). This construct lacks a stabilized tetraloop group and does not bind to ricin A-chain. The electrostatic potential surface reveals the similarity between the transition state structure and the inhibitor.175

Figure 26.

Comparison of electrostatic potentials for the transition state (a) of saporin L3 and the transition state mimic (b) of a truncated 2-base transition state mimic (c). This truncated inhibitor is a 3.3 nM TS analogue. Reproduced from ref 175. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

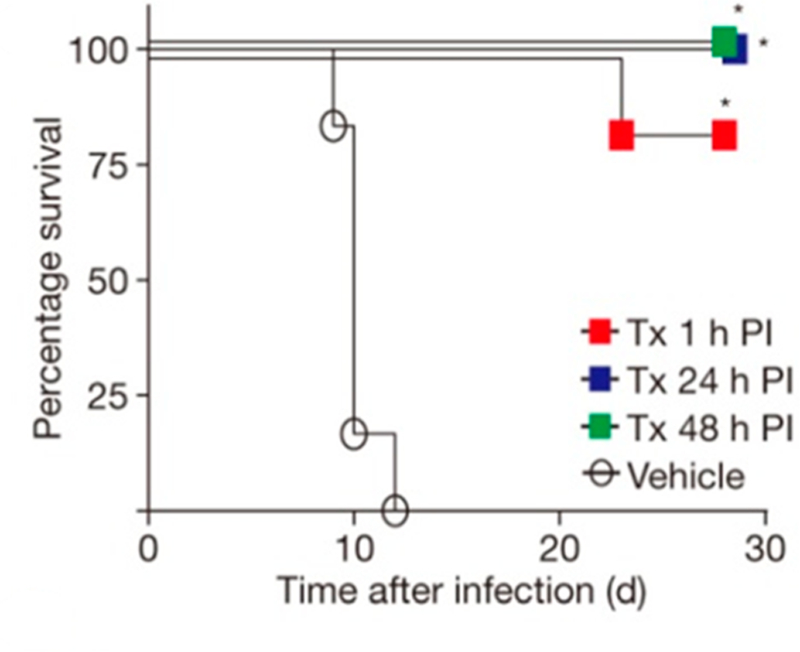

7.2.3. Saporin L3 Inhibitors Protect Ribosomes.

Inhibitors of saporin L3 were tested with an in vitro protein translation system using ribosomes from rabbit reticulocyte lysates. The 2-base saporin L3 inhibitor construct (Figure 26) was used. Saporin L3 at a concentration of 300 pM caused ∼90% inhibition of cell-free translation.178 Under the same conditions, varied concentrations of the inhibitor (Figure 26) were added to rescue protein synthesis by protection of the ribosomes from saporin L3. The inhibitor rescued protein synthesis with an EC50 of 36 ± 2 nM, consistent with protection by blocking the saporin L3 catalytic site. This inhibitor also inhibited adenine release from purified 80S rabbit ribosomes with an IC50 of 7.8 ± 1.1 nM. The transition state inhibitors of saporin L3 are effective in preventing ribosome depurination and depurination of small nucleic acid substrates. No studies have yet been reported on the use of saporin L3 inhibitors in protecting cells or animals from the side effects caused by saporin L3.

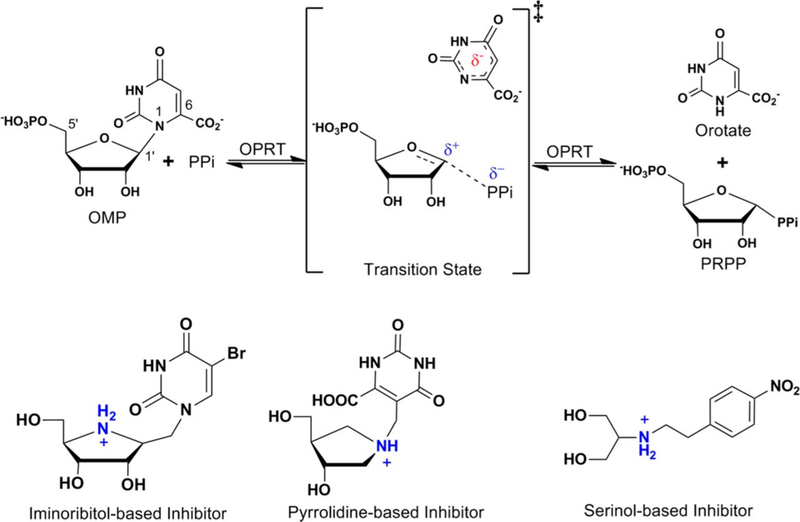

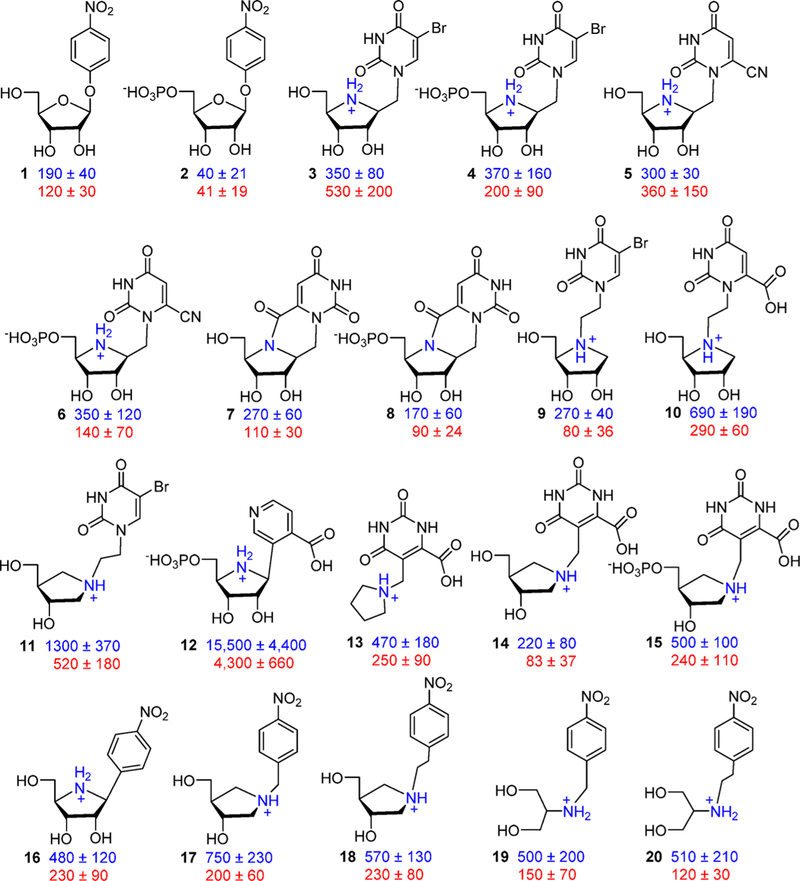

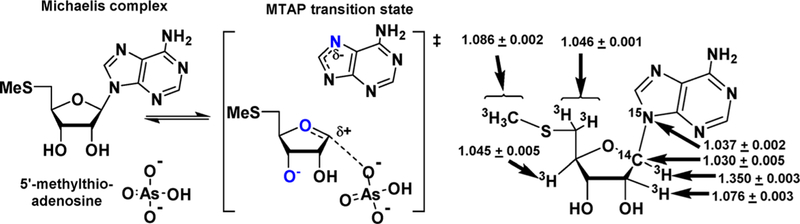

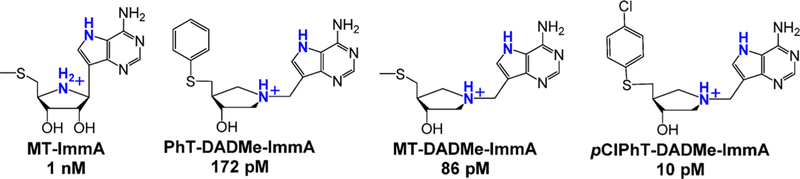

8. PURINE PHOSPHORIBOSYLTRANSFERASES

8.1. Discovery and Biological Function

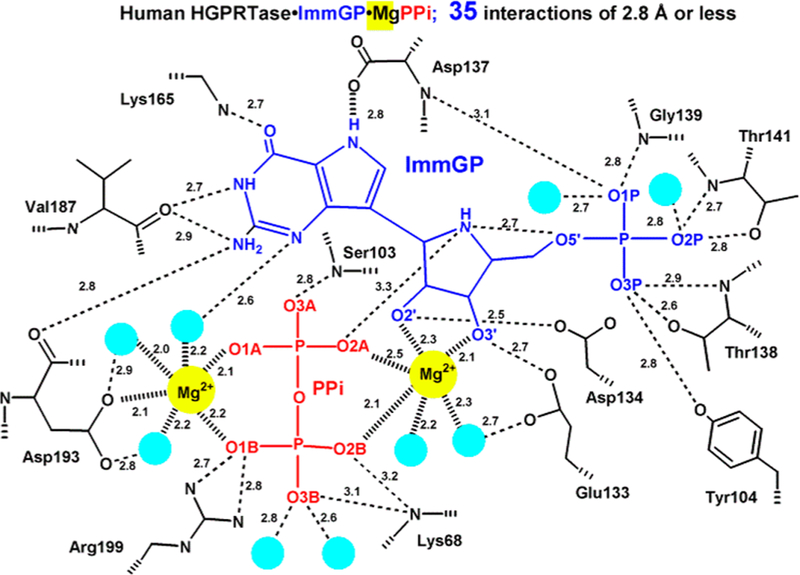

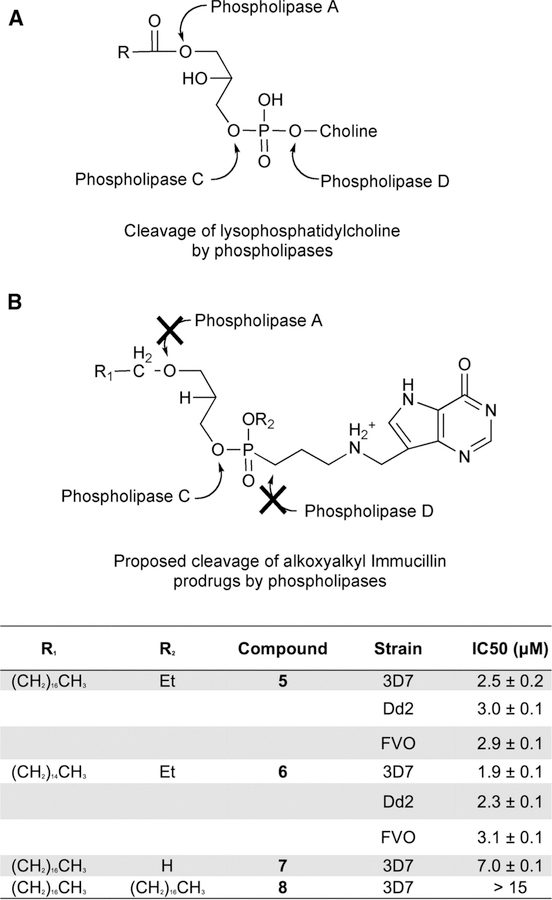

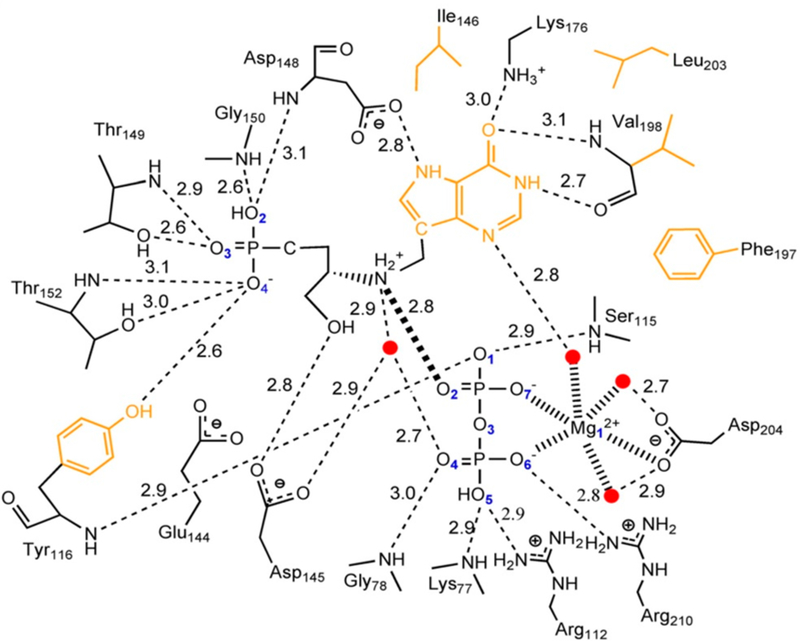

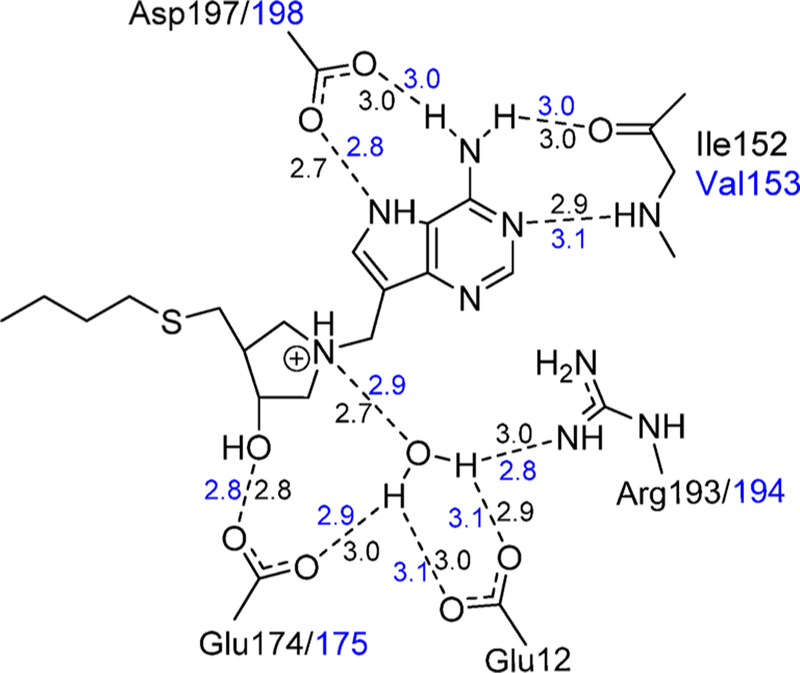

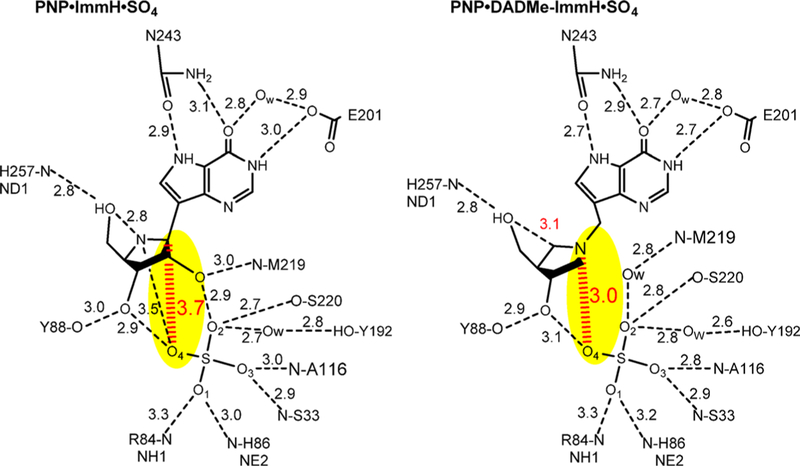

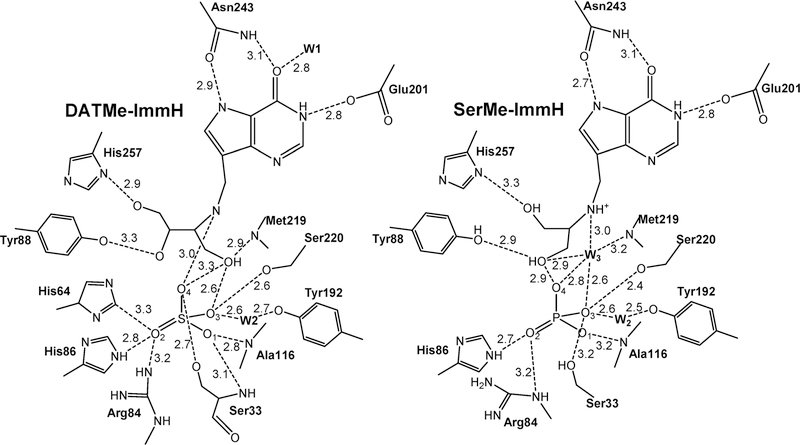

Kornberg, Lieberman, and Simms discovered and characterized 5-phosphoribosyl-α-D-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) in 1954 as the required ribosyl phosphate donor in the synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides from orotic acid.179 The importance of purine salvage in humans via hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase became apparent with the discovery of its genetic deficiency as the cause of Lesch–Nyhan syndrome.180–182 Studies with Plasmodium species indicated an ability to synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides by de novo pathways but not purines, making exogenous purines essential nutrients.183 The pathway for purine salvage in P. falciparum was deduced by direct assay of the enzymes from extracts of cultured parasites, where the high activities of adenosine deaminase, purine nucleoside phosphorylase, and hypoxanthine-guanine-xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGXPRT) supported a robust pathway for salvage of hypoxanthine.184 More recent studies have concluded that purine phosphoribosyltransferases provide an essential step for purine salvage in most purine auxotrophic protozoan parasites.185–187 On the basis of the nature of the transition states for the nucleoside hydrolases and purine nucleoside phosphorylase, transition state analogue candidates were synthesized and found to be powerful inhibitors of the enzymes from both P. falciparum and human sources.188,189 Crystal structures indicated catalytic site contacts essential for catalysis, including the catalytic site magnesium atoms required for catalysis in the HG(X)PRTs (Figures 27 and 28).190–192

Figure 27.

Catalytic site contact map for human HGPRT in complex with ImmGP.190 Light green circles represent crystallographic water oxygens. O2A is the nearest to the reaction center and is proposed to be the nucleophilic oxygen.

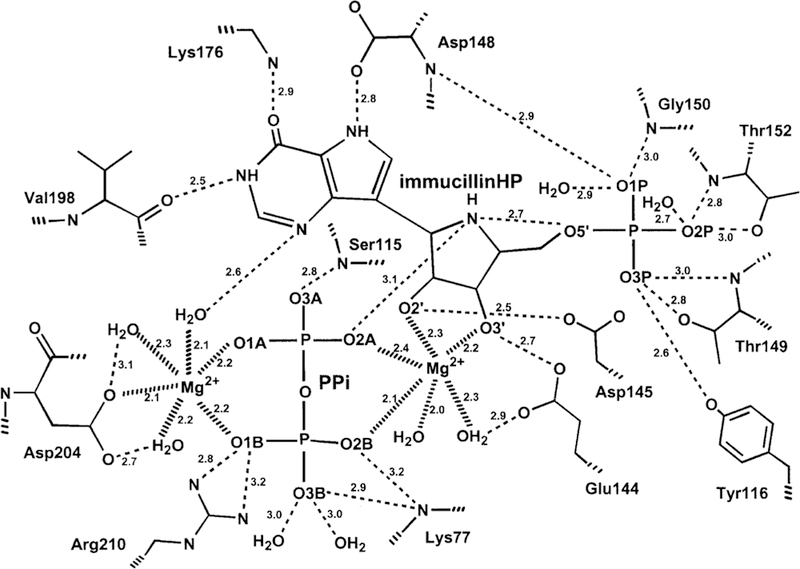

Figure 28.

Catalytic site contact map for P. falciparum HGXPRT in complex with ImmHP. Similar to the structure of the human enzyme, O2A is the nearest to the reaction center and is proposed to be the nucleophilic oxygen and the O5′–N4′ distance is 2.7 Å. Reproduced from ref 191. Copyright 1999 American Chemical Society.

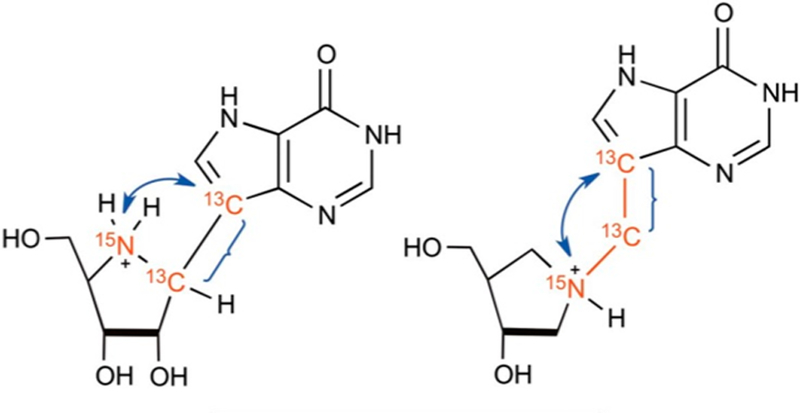

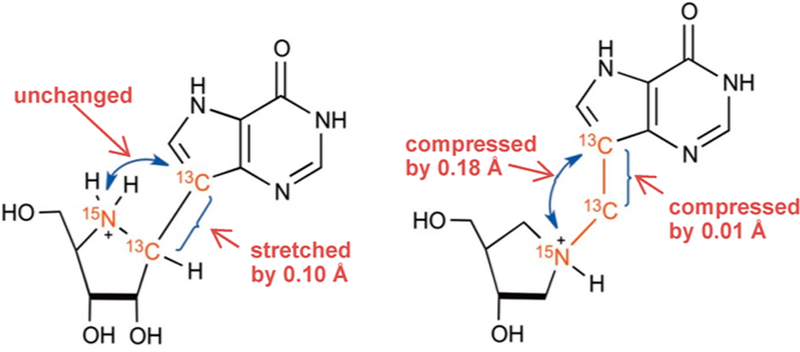

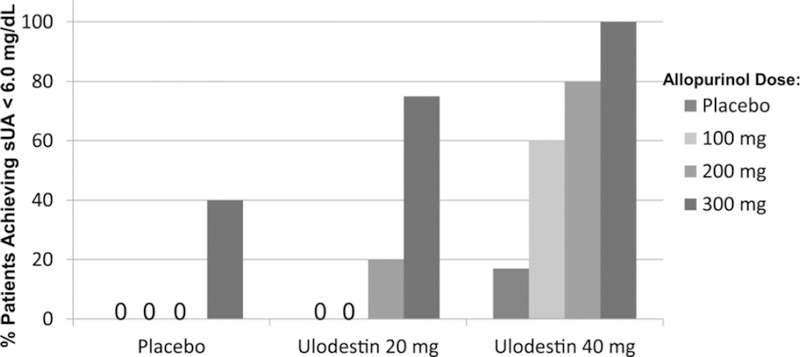

8.2. Transition State Structures

The transition states for N-ribosyltransferases exhibit ribocation character with purine leaving groups activated by protonation at N7 of the purine ring.193 As the reaction of HGXPRT is freely reversible (hypoxanthine + PRPP ↔ IMP + PPi), the transition state can be reached from either direction. Analogues of IMP were synthesized with ribocation features of the transition state, similar to the targets described above. Immucillin-G 5′-phosphate (ImmGP) was a 4.6 nM inhibitor of the HGPRT from human sources, binding 14 000 times tighter than the dissociation constant for IMP.188 Considering the full catalytic site ensemble of two Mg2+ ions, PPi, and ImmGP finds 35 interactions at 2.8 Å or less. Thus, the inhibitor complex is highly immobilized, and dilution experiments show slow release of the inhibitor from the inhibited complex.188 Of specific interest for the mechanisms of N-ribosyltransferases is the interaction of Asp137 stabilizing the hydrogen bond to N7, as protonation of the leaving group is a common feature of these enzymes. Another significant interaction is the O5′ with the N4′ iminoribitol nitrogen at 2.7 Å. When nucleotides are at the catalytic site, the close O5′–O4′ distance constitutes a neighboring group interaction assisting formation of the ribocationic transition state.194

8.3. Iminoribitol Transition State Analogues

Immucillin-H 5′-phosphate and Immucillin-G 5′-phosphate were analyzed for P. falciparum HGXPRT and found to be 1 and 14 nM inhibitors, respectively. In the crystal structure of the P. falciparum HGPRT, Asp148 plays the role of N7 proton donor as does Asp137 in the human structure (Figure 28). In both human and P. falciparum enzymes, two Mg2+ ions form bidentate interactions with both phosphoryl groups of the PPi and bridge it to the ribosyl group by another bidentate interaction to the vicinal 2′,3′-hydroxyl groups of the nucleotide. In both enzymes, the transition state analogues are proposed to capture part of the tight interactions at the transition state. An unusually strong hydrogen-bond interaction is observed by the NMR chemical shift of the N7-Asp hydrogen bond. The chemical shift for this proton is detected in the enzyme–immucillinHP–Mg2+– pyrophosphate complexes for both human and P. falciparum enzymes. Downfield 1H signals at 13.9 (human) and 14.3 ppm (P. falciparum) have been assigned to the N7 protons of ImmHP hydrogen bonded to Asp148 (Asp137 for the human enzyme) by 15N-edited proton NMR spectra using [7-15N]ImmHP.188,191 Isotope-edited Raman and FTIR studies of the complex with enzyme–immucillinHP–Mg2+–pyrophosphate found the 5′-phosphate to be dianionic and the pyrophosphate to be the fully ionized tetraanion.195 Mutagenic studies indicate that the Asp is important for catalysis but does not contribute significantly to substrate binding.196,197 Despite the tight binding of the ImmHP and ImmGP for their target enzymes, phosphate esters are not suitable drugs, as anions are membrane impermeable and phosphoesters are susceptible to hydrolysis.

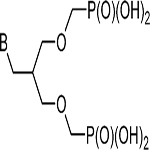

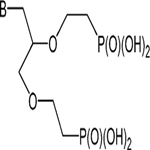

8.4. Asymmetric Acyclic Nucleoside Bisphosphonate Inhibitors

The multiple phosphate binding sites in the catalytic sites of purine phosphoribosyltransferases have led to the synthesis of families of symmetric or asymmetric acyclic nucleoside bisphosphonates (ANbP) as inhibitors of human HGPRT and P. falciparum HGXPRT (Table 2).198–201 Compounds 1a and 20 are 30 and 6 nM inhibitors for the P. falciparum HGXPRT. When converted to the phosphoramidate prodrugs to permit cellular entry, the IC50 values for inhibition of P. falciparum growth in cultured erythrocytes were between 1.4 and 9.7 μM and showed low toxicity for human cell lines.200

Table 2.

Symmetric and Asymmetric Acyclic Nucleoside Bisphosphonate Ki Value with Human and P. falciparum Purine PRTs198–20,1

| No. | Base | Acyclic moiety | Human HGXPRT Ki[μM] | P. f. HGXPRT Ki[μM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | G |  |

0.03 | 0.07 |

| 1b | Hx | 1 | 5 | |

| 2a | G |  |

0.6 | 0.5 |

| 2b | Hx | 0.7 | NIa | |

| 27 | 8-Br-G | 0.4 | 0.9 | |

| 20 | G |  |

0.006 | 0.07 |

| 21 | Hx | 1.8 | 3 | |

| 22 | 8-Br-G | 0.1 | 2 | |

| 23 | 8-Br-Hr | 2.5 | NI | |

| 24 | 7-deaza-G | 0.1 | 4 | |

| 25 | 7-deaza-Hx | 4.6 | 6 |

No inhibition obseved. Base abbreviations are guanine (G), hypoxanthine (Hx), and 8-bromo (8-Br).

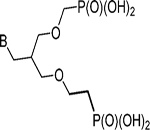

What do these constants suggest for potential druggability of the compounds in Table 2? Inhibition of human HGPRT is not a major concern in the treatment of malaria, as only long-term genetic deficiency of the enzyme leads to symptoms in humans. However, two other concerns are dissociation constants above 70 nM, making them weaker by factors of up to 100 than transition state analogues (e.g., 2, Figure 29) for the same target. The phosphonates of Table 2 and Figure 29 suffer from the likely barrier to oral uptake from anionic compounds. Both will need prodrug chemistry to move them toward useful agents.

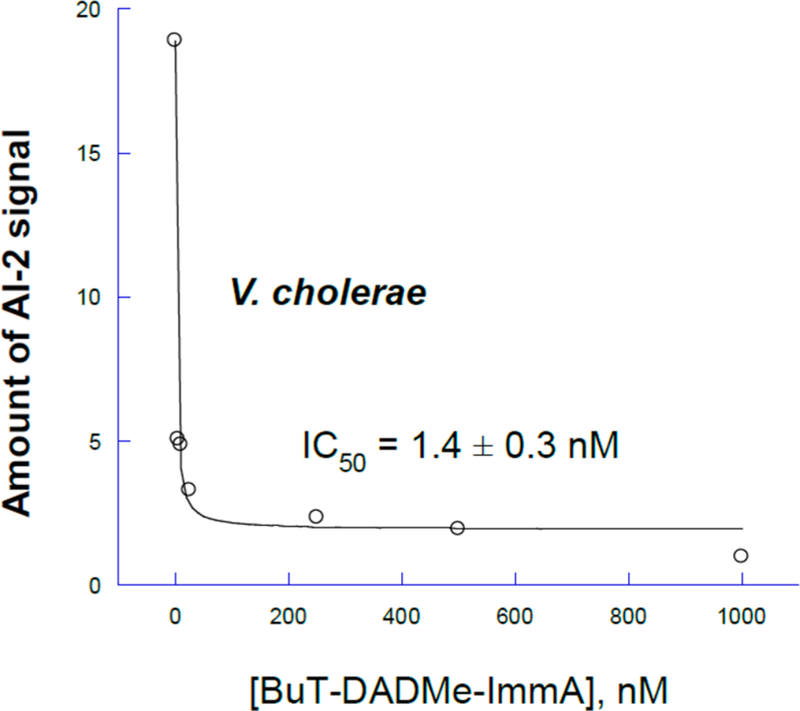

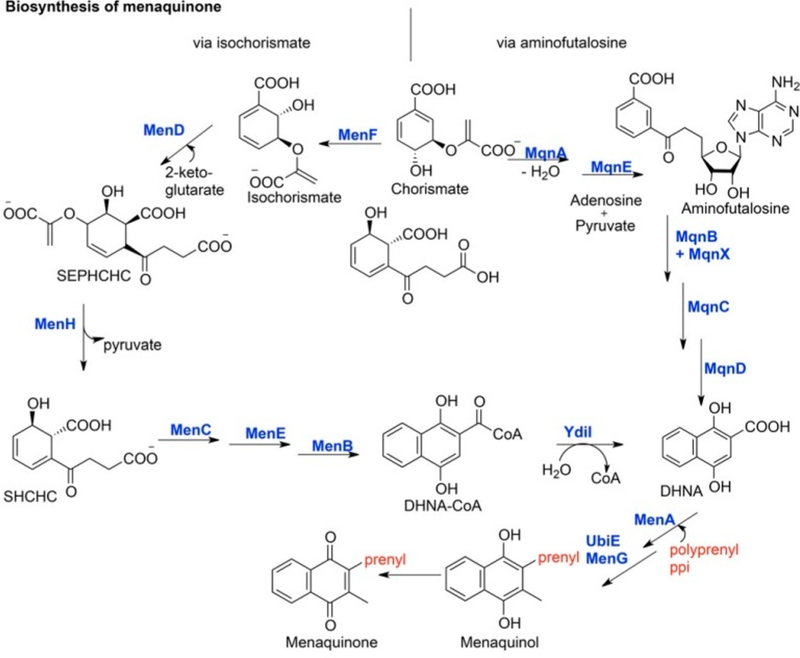

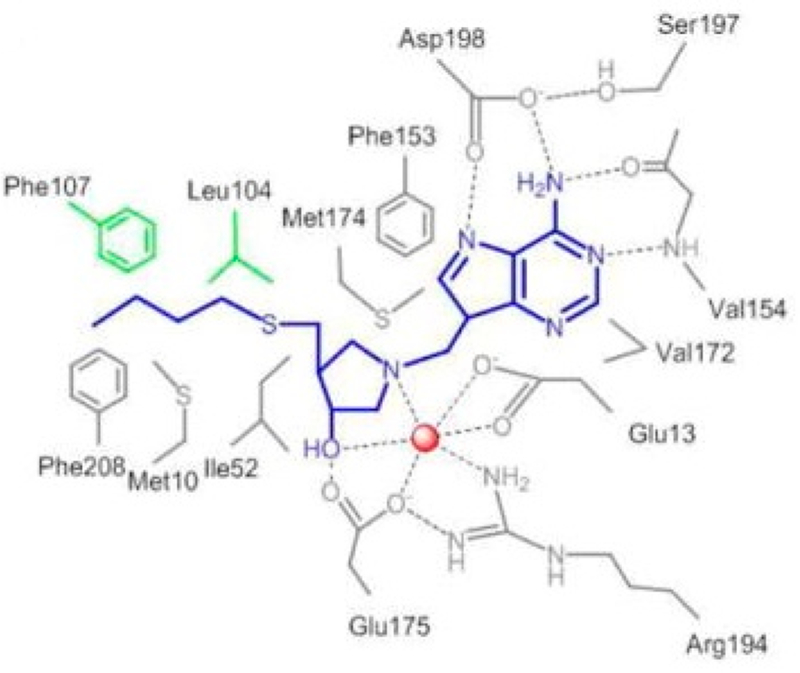

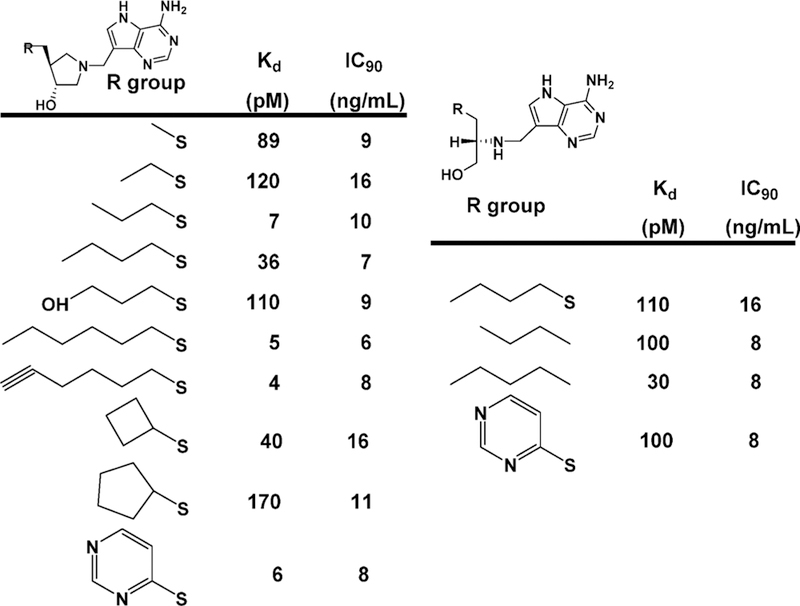

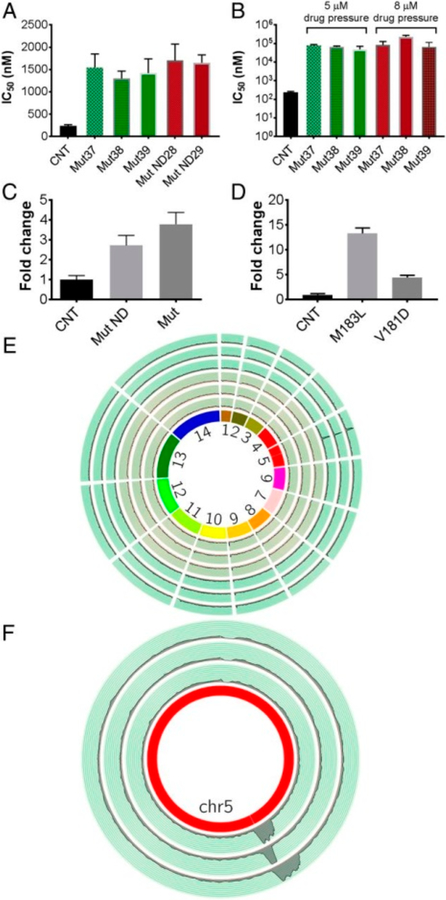

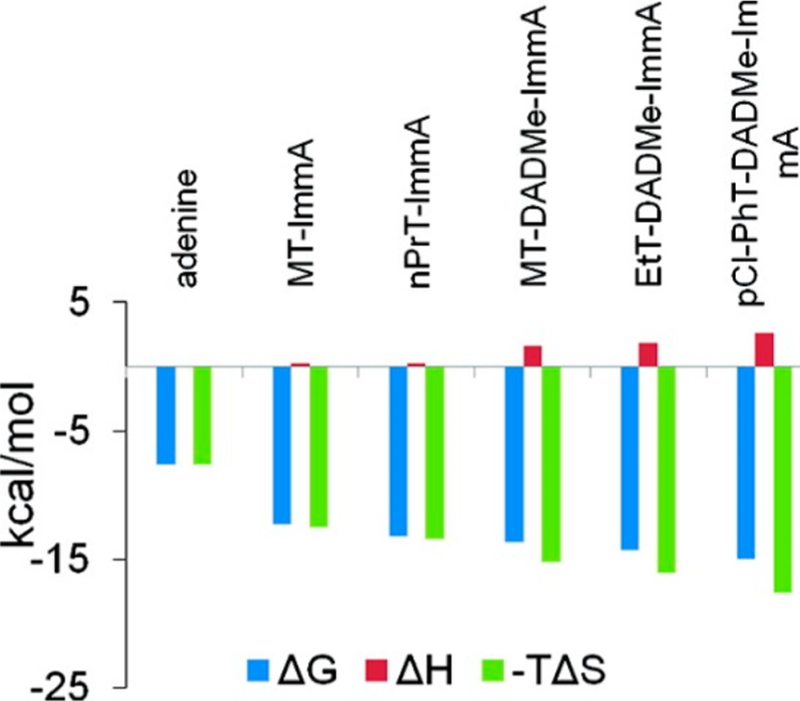

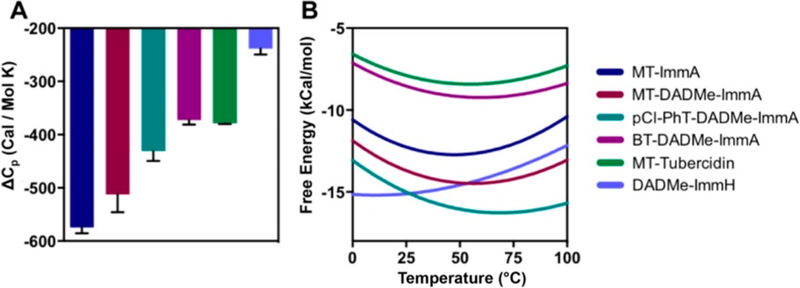

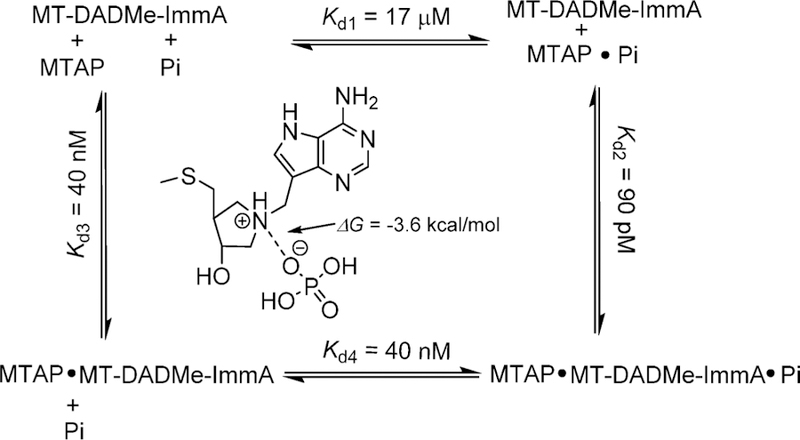

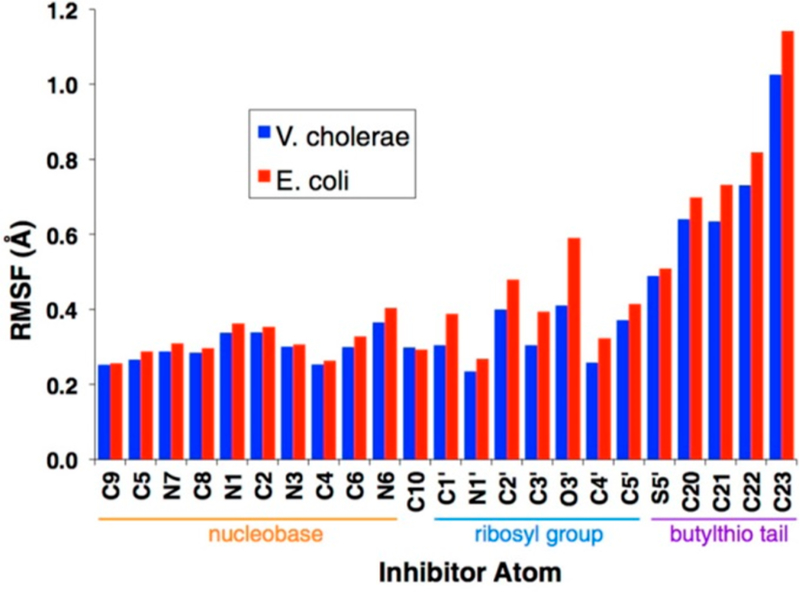

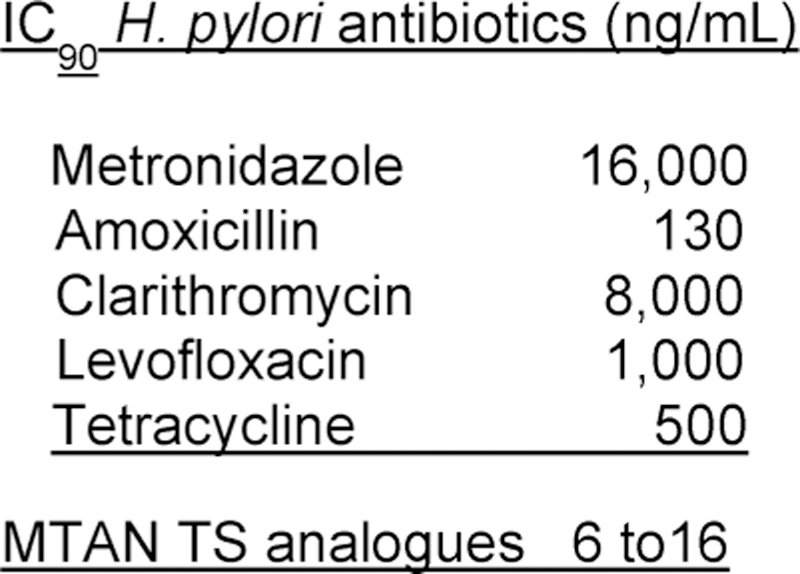

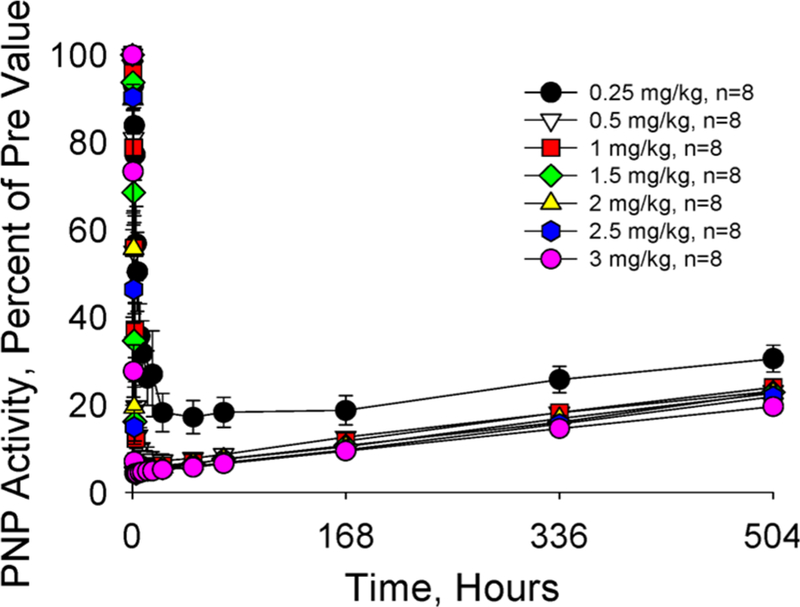

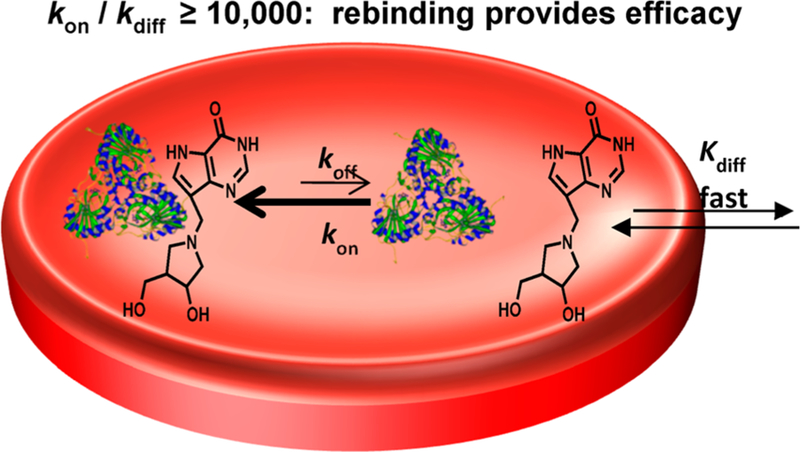

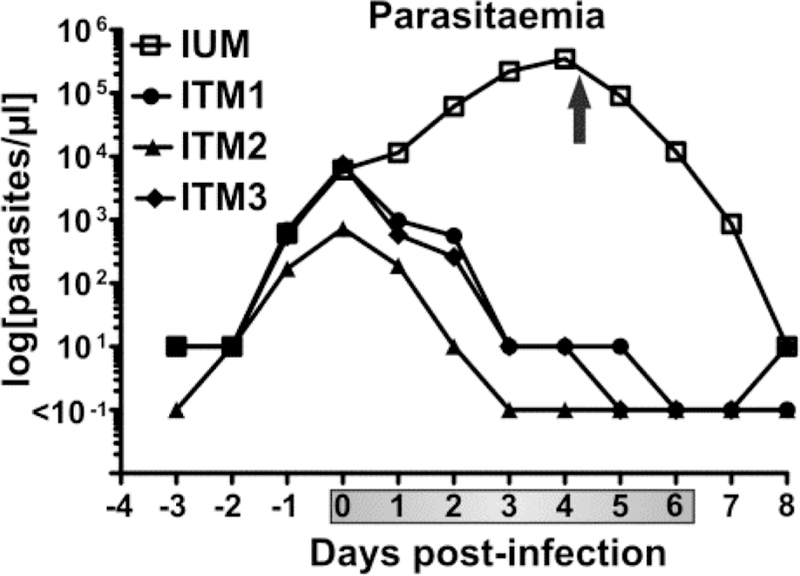

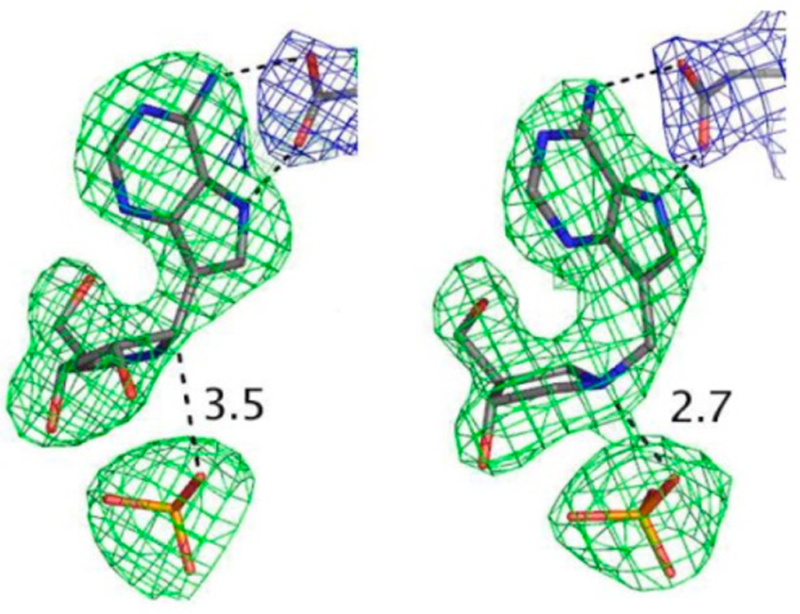

Figure 29.