Abstract

Eukaryotic DNA polymerase (Pol) X family members such as Pol μ and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) are important components for the nonhomologous DNA end-joining (NHEJ) pathway. TdT participates in a specialized version of NHEJ, V(D)J recombination. It has primarily nontemplated polymerase activity but can take instructions across strands from the downstream dsDNA, and both activities are highly dependent on a structural element called Loop1. However, it is unclear whether Pol μ follows the same mechanism, because the structure of its Loop1 is disordered in available structures. Here, we used a chimeric TdT harboring Loop1 of Pol μ that recapitulated the functional properties of Pol μ in ligation experiments. We solved three crystal structures of this TdT chimera bound to several DNA substrates at 1.96–2.55 Å resolutions, including a full DNA double-strand break (DSB) synapsis. We then modeled the full Pol μ sequence in the context of one these complexes. The atomic structure of an NHEJ junction with a Pol X construct that mimics Pol μ in a reconstituted system explained the distinctive properties of Pol μ compared with TdT. The structure suggested a mechanism of base selection relying on Loop1 and taking instructions via the in trans templating base independently of the primer strand. We conclude that our atomic-level structural observations represent a paradigm shift for the mechanism of base selection in the Pol X family of DNA polymerases.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, DNA repair, X-ray crystallography, structural biology, DNA damage, non-homologous DNA end joining, double-strand break, DNA bridging, DNA synapsis, DNA polymerase Pol X family, V(D)J recombination, junctional diversity, ternary complex, Pol μ catalytic cycle

Introduction

Two major DNA repair systems can resolve DNA double-strand breaks (DSB):4 homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) (1). HR is an accurate process that takes advantage of the presence in the cell of a DNA duplex that is homologous to the DSB site and that will restore faithfully the DNA integrity (2). In contrast, the NHEJ pathway relies only on the two DNA ends at the DSB sites and does not require the presence of homologous DNA. Importantly, NHEJ is usually error-prone, leading to the loss or the addition of a few nucleotides (3). HR can occur only in dividing cells during late S and G2 stages, after synthesis of a homologous DNA molecule, whereas the NHEJ pathway can be potentially activated in all phases of the cell cycle and is thought to be the major DSB repair system in higher eukaryotic cells (4).

The NHEJ pathway involves sequential interactions of proteins allowing stabilization, end processing, and ligation of the DSB. The eukaryotic NHEJ machinery is composed of the Ku heterodimer (Ku 70/80), DNA-PKcs, Artemis nuclease, Pol λ and/or Pol μ, and the ligase IV–XRCC4–XLF complex, with accessory roles by Paralog of XRCC4 and XLF and apratoxin and PNK-like factor (5, 6). The same machinery participates in a programmed genetic recombination that occurs in developing lymphocytes called V(D)J recombination (7–9). During this process, TdT incorporates random nucleotides at the coding end to increase immune repertoire diversity (10, 11). The expression of TdT is limited to primary lymphoid organs, where B- and T-cell maturation occurs, and consequently TdT does not participate in the NHEJ pathway in other cell types (12).

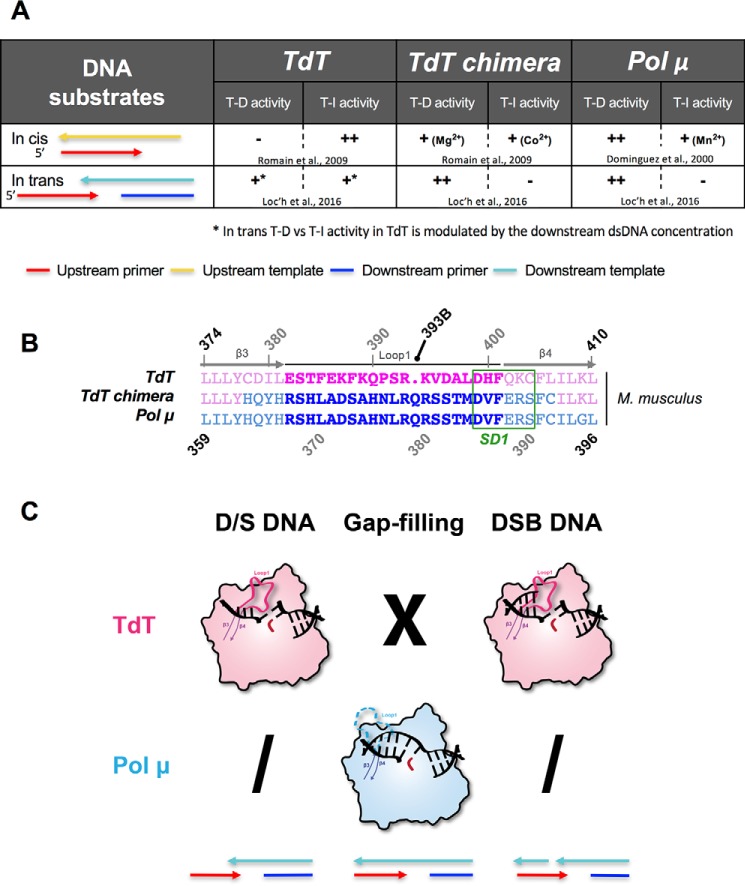

For the last 50 years, TdT has been described as a template-independent polymerase (13, 14). Indeed, it behaves like a nucleotidyltransferase even in the presence of an in cis template strand (Fig. 1A). However, recent results demonstrate the ability of this enzyme to carry out templated activity across strands in the presence of a downstream (in trans) DNA duplex with a 3′-protruding end at high DNA/TdT ratios (15). This activity was also described earlier for Pol μ at an equimolar DNA/Pol X ratio (16), as well as an intrinsic nucleotidyltransferase activity in the presence of transition metal divalent ions (Fig. 1A). TdT and Pol μ are two members of the polymerase X family that share high sequence and structure similarity (17, 18) (see Fig. S1 for their alignment). From a structural point of view, the main difference between these two polymerases is the sequence of a long loop (Loop1) composed of 20 amino acids (382–401 in TdT) between the β3 and β4 strands (Fig. 1B). In all TdT structures, Loop1 adopts a lariat-like conformation (Fig. 1C) that prevents the binding of an uninterrupted template DNA strand (19). In contrast, Loop1 is disordered in Pol μ structures obtained in a gap-filling complex and does not interact with the continuous template DNA molecule used for crystallization (20). Thus far, Pol μ could not be crystallized in complex with a true DNA–DSB substrate, despite substantial efforts from several laboratories, whereas TdT could not be crystallized in the presence of a 1-nt-gapped DNA substrate (Fig. 1C).

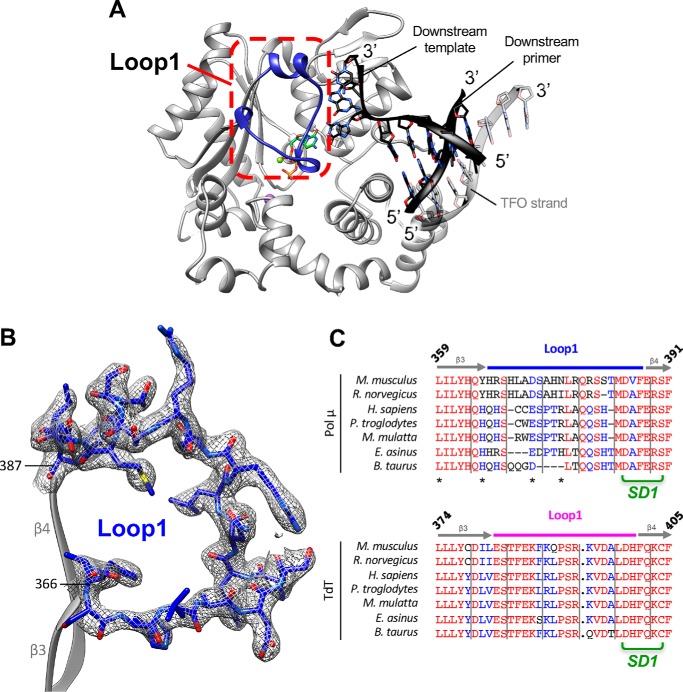

Figure 1.

Templated or template-independent activity of TdT, TdT-μ chimera, and Pol μ in the in cis or in trans situations. A, summary of the different activities of TdT-μ chimera in the presence of different DNA substrates, already known from the indicated references (15, 18, 22), illustrating its template-dependent (T-D) or template-independent (T-I) activities, both in cis and in trans. B, sequence alignments of Loop1 sequence in Mus musculus TdT-WT, TdT-μ chimera, and Pol μ. Residues belonging to Loop1 are represented in boldface type. The region SD1 is indicated in green. The special numbering choice for the insertion Gln393 is highlighted in black. C, previously known structures of complexes of TdT (pink) or Pol μ (blue) with a primer strand and a downstream DNA duplex (D/S DNA), in a gap-filling mode or with a full DSB–DNA junction. The colored arrows at the bottom indicate the 5′ to 3′ orientation of strands used in the DNA substrates. X means 'not possible' and a slash 'not done.'

Extensive biochemical experiments were performed on TdT and Pol μ to better understand the difference between their activities. For instance, Pol μ can acquire a template-independent activity by single point mutation or by exchanging the catalytic metal ions from Mg2+ to Mn2+ (21). Conversely, it is possible to transform TdT to a template-dependent in cis polymerase by a single point mutation that destabilizes the Loop1 conformation (22), as probed by regular primer extension tests with a primer–template duplex containing a 5′-end overhang on the template strand. Interestingly, the deletion of Loop1 in Pol μ improves both DNA binding and catalytic efficiency in DNA-templated reactions (in cis) but inhibits its weak intrinsic template-independent activity (23). Similar experiments with TdT lead to the same conclusion: deletion of Loop1 leads to a drastic decrease of the untemplated activity correlated with an increase of the in cis template-dependent activity (22). Furthermore, grafting Loop1 of Pol μ to a chimeric TdT (Fig. 1B) confers to TdT an in cis templated activity (22) (Fig. 1A) and vice versa (23). These results highlight the importance of Loop1 for the specific activity of both Pol μ and TdT. However, the role of Loop1 of Pol μ specifically in a DNA-bridging context is far from clear.

Interestingly, crystal structures of TdT in the presence of a full DNA synapsis could be obtained (15) and showed that Loop1 is crucial to maintain a tight binding of TdT across the DNA synapsis (Fig. 1C). This raised the question of whether Loop1 has the same role in Pol μ and possibly uses a similar mechanism of base selection.

Here, we present a complete functional and structural characterization of the TdT–Loop1–Pol μ chimera (Fig. 1B), hereafter referred to as the TdT-μ chimera. We previously showed that it is a templated enzyme across a discontinuous template strand, taking its instructions in trans at a 1:1 DNA/TdT ratio (15). We now demonstrate the biological relevance of this Tdt-μ chimera protein using an in vitro NHEJ ligation assay, which shows functional properties similar to Pol μ. We then solve and compare its crystal structure in the apo form with that of Pol μ (20) as well as in the gap-filling mode. We also report the structure of a ternary complex with the downstream dsDNA (down-dsDNA), where Loop1 is fully ordered and prevents the binding of the upstream dsDNA (up-dsDNA) but actively participates in the selection of the incoming dNTP in front of a template base located in trans. Related studies on LigD in prokaryotes show striking similarities with this mechanism (24). Finally, we present the structure of a ternary complex of TdT-μ chimera with a full DNA–DSB synapsis and an incoming nucleotide, which could be used as a model for the Pol μ–DNA DSB complex.

Results

The TdT–Loop1 chimera

The first Pol X chimera was described in 2006 (23). In this paper, Juarez et al. created both a Pol μ ΔLoop1 mutant and a chimeric construct (Pol μ–TdT chimera) in which Loop1 was replaced by the one from TdT. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay experiments with Pol μ ΔLoop1 and different DNA substrates suggested that Loop1 negatively affects the DNA-binding capacity of Pol μ. Furthermore, deletion of Loop1 in Pol μ produced a 10-fold improvement of the catalytic efficiency of in cis templated polymerase activity and abolished the intrinsic template-independent activity of Pol μ (23). Functional assays showed a similar polymerase activity between the Pol μ–TdT chimera and TdT, in the presence of ssDNA and template–primer substrate.

We performed similar experiments using a TdT-μ chimera (described in Fig. 1B), obtained by the grafting of Loop1 of Pol μ in a TdT context (22). Note that in the TdT–Pol μ chimera, 29 amino acids were changed, containing Loop1 (20 residues). In addition, 4 residues upstream and 5 residues downstream were changed, thereby also including the SD1 region, which stands out as “maximally different” between TdT sequences and Pol μ sequences (25). Comparable template-dependent polymerase activity was observed in the TdT-μ chimera and Pol μ using an in cis DNA substrate (Fig. 1A), whereas WT TdT displays an essentially untemplated polymerase activity in the same conditions (22). More recently, we demonstrated a similar template-dependent activity both in TdT-μ chimera and Pol μ using an in trans DNA substrate (Fig. 1A) (15, 26). Here we describe further functional studies of TdT-μ chimera using an in vitro NHEJ ligation assay.

Ligation of compatible or incompatible 3′ overhangs in the presence of full-length WT TdT, TdT-μ chimera, and Pol μ

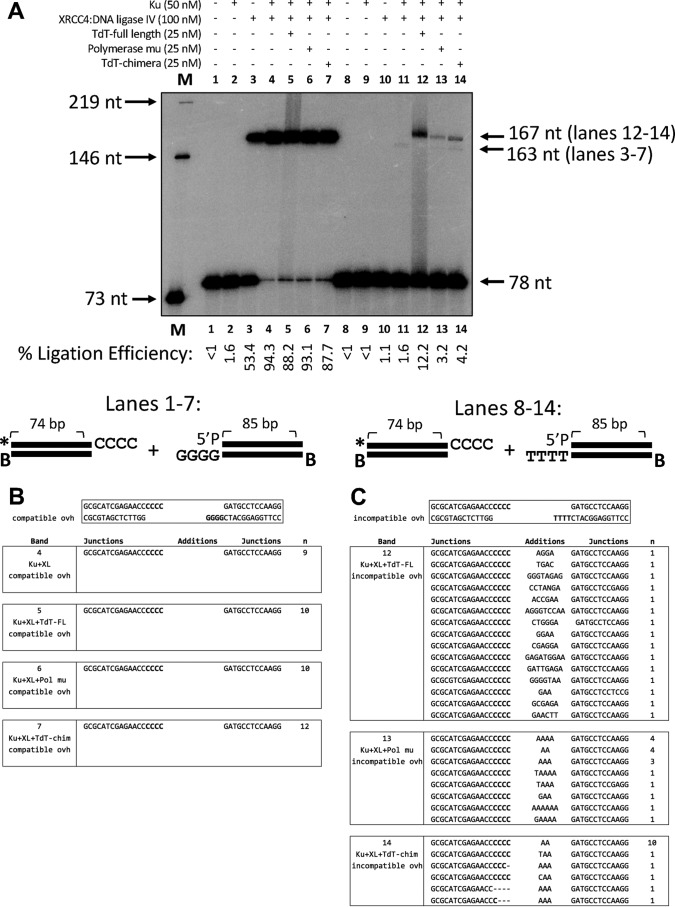

In Fig. 2, we show that XRCC4–ligase IV alone is sufficient for ligation of compatible 4-nt 3′ overhangs (lane 3, 53% efficiency), whereas the addition of Ku 70/80 ensures an even more efficient (>88%) ligation (lanes 4–7) (Fig. 2A). This reflects in vivo data showing that Ku 70/80 is not essential for ligation of overhangs containing at least 2 bp of microhomology, which can be generated upon hairpin nicking during V(D)J recombination (40). Sequencing data show that ligation proceeds without nucleotide addition by a polymerase, likely because rapid base pairing of these overhangs occurs faster than template-independent or template-dependent polymerase activity at the DNA ends (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Ligation experiments in the presence of XRCC4–ligase IV and Ku 70/80. A, comparative functional properties of TdT WT, Pol μ, and TdT-μ chimera using complementary or noncomplementary overhangs. B, sequences of the products of ligation for compatible overhangs. Note that only the top strand of sequence is shown. The junctions are where the Additions column is located, and when no nucleotides are present here, this means that the left and right ends are joined directly, using the compatible overhangs. C, sequences of the products of ligation for incompatible overhangs. Note that only the top strand of sequence is shown.

Whereas XRCC4–ligase IV is sufficient for ligation of compatible overhangs, we find that substantial ligation of incompatible 3′ overhangs does not occur in the absence of TdT-WT, Pol μ, or TdT-μ chimera (lanes 12–14) (Fig. 2A). Sequencing data show that at least 1 bp of microhomology must become available through either template-dependent or template-independent nucleotide addition before ligation of the ends can occur (Fig. 2C). In particular, these data show that full-length TdT adds nucleotides randomly until at least 1 nucleotide is available for base pairing with the downstream strand. As expected, this reflects the known template-independent activity of TdT-WT. Conversely, Pol μ adds nucleotides mainly template-dependently, although there are four instances where a template-independent addition of 1 nucleotide occurs prior to templated addition, illustrating a small degree of template-independent activity (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the activity of TdT-μ chimera is much more like that of Pol μ than that of TdT in terms of template dependence because most of the nucleotides added are A and thus complementary to the T overhang of the right-hand DNA end. This clearly indicates that Pol μ Loop1 does indeed confer template-dependent activity to the TdT-μ chimera across strands, in the context of a DNA synapsis. In addition to the ligated product sequence, the ligation efficiency also emphasizes that the chimera is more like Pol μ than TdT. Specifically, ligation in reactions with Pol μ and TdT-μ chimera are very similar in efficiency, in contrast to the efficiency for the TdT reactions (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 12, 13, and 14). Therefore, it is important to note that both the joining efficiency and junctional sequencing support the conclusion that the chimeric protein behaves like Pol μ rather than TdT.

Overall structure of TdT-μ chimera apoenzyme or in complex with the incoming nucleotide

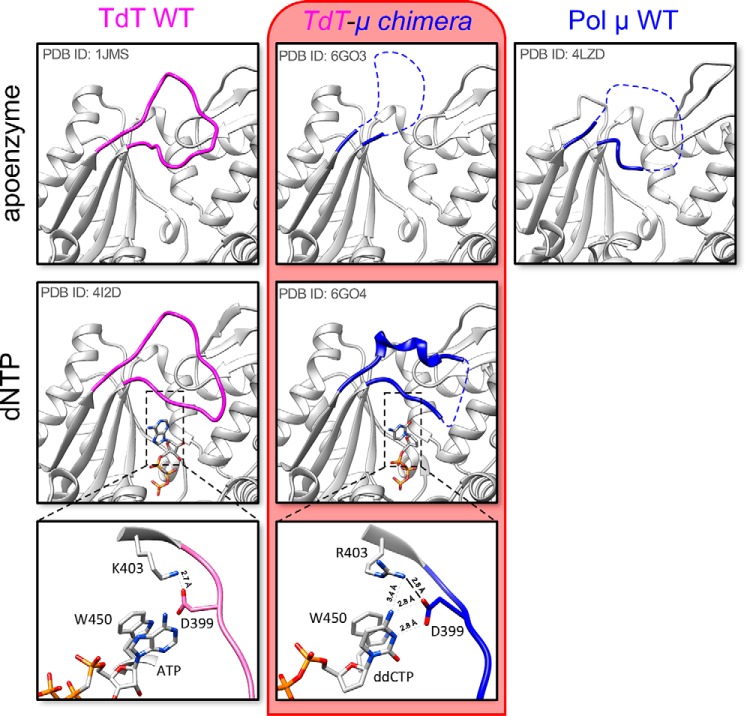

Structures of TdT-μ chimera apoenzyme or as a complex with an incoming dideoxynucleotide were solved at 2.20 and 1.96 Å resolution, respectively. The overall architecture of the TdT-μ chimera protein is almost identical to the TdT apoenzyme structure (RMSD of 0.517 Å over 336 Cα atoms using PDB entry 1JMS). The only notable difference is observed in Loop1, localized between strands β3 and β4. In TdT apoenzyme, this loop adopts a lariat-like conformation, with a clear electron density (19), whereas in TdT-μ chimera apoenzyme, 16 amino acids (positions 384–399) of 20 are missing in the electron density map (Fig. 3). Therefore, Pol μ's Loop1 (in the context of TdT) appears to be as flexible as reported in the context of Pol μ apo-structure or engaged in a gap-filling complex (20, 27).

Figure 3.

Loop1 conformation in TdT WT, TdT-μ chimera, and Pol μ without or with dNTP. The new structures described in this paper are framed in red. No structure of the binary complex with an incoming nucleotide is available for Pol μ. Residues in Loop1 depicted in pink belong to TdT, whereas residues colored in blue belong to Pol μ. In addition, a more detailed picture of the interaction of the incoming base ddCTP with the ion pair Arg403-Asp399 (Lys403-Asp399 in TdT) of Loop1 is shown at the bottom; close distances are shown with dotted lines.

Interestingly, in the structure of the TdT-μ chimera dNTP–Mg2+ complex, Loop1 becomes mainly visible, with the exception of residues 394–396, and contains a short α-helix. Some crystal contacts were observed that might stabilize this short helix (especially Arg393), but the rest of the Loop1 structure is free from such contacts and is sufficient to prevent the binding of an uninterrupted template strand (Fig. 3), as described in various TdT-dNTP structures (28). Here Asp399 and Arg403 make specific hydrogen bonds with the nucleobase (Fig. 3), which is stacked between the conserved positions Trp450 and Arg454. We note that in a bacterial Pol X from Thermus thermophilus, the equivalent of Arg454, namely Lys263, has also been seen to be essential for strong binding of dNTP–Mg2+ (29). The triphosphate moiety of the dNTP binds at the same place in all other TdT or Pol μ structures.

Asp399 and Arg403 belong to a specific sequence motif located at the end of Loop1, called SD1 and first identified by Romain et al. (22) in 2009 (Fig. 1B), and they form an important salt bridge (Asp399–Lys403) in TdT (15), also probed by site-directed mutagenesis in (22). Asp399 is conserved in Loop1 of TdT and Pol μ; its mutation into a glutamate in Pol μ leads to the degradation of the primer strand (28), whereas the mutation of Arg403 in Pol μ results in an increased nucleotidyltransferase activity (21). Here, we mutated the same position in the context of the Tdt-μ chimera and tested the activity of the R403A mutant for its in trans templated activity (Fig. S2). We found a decreased activity with all four substrates, thereby confirming the important role of this side chain suggested by the X-ray structure.

We also observed a rearrangement in the catalytic site involving the side chain of the Asp434. Specifically, in the apo form and, in fact, in all known structures of Pol μ and TdT, this aspartate makes a salt bridge with Arg432 (both Asp434 and Arg432 residues have been shown to be essential in TdT by site-directed mutagenesis.5 Here it changes partners from Arg432 to Arg403, from the SD1 motif, preventing the correct coordination of metal A, which is absent in the structure of the dNTP–Mg2+ complex (Fig. S3). We note that the equivalent of Asp434 in Pol λ is seen in both conformations in PDB structure 1XSN and that metal A is known to be the last partner to bind to complete the assembly of the catalytic site in Pol β (31). A similar (but not identical) mechanism involving a change of partners in salt bridges occurs in the catalytic site of Pol β when switching from the open form to the closed form (32); specifically, Asp192 switches from interacting with Arg258 to metal B, whereas Arg258 changes rotamer to interact with Glu295 and Tyr296 in motif SD2.

In summary, the presence of the incoming nucleotide participates in the organization of Pol μ's Loop1, whereas in TdT, Loop1 is intrinsically ordered and adopts a similar conformation (RMSD = 1.95 Å) in the absence or in the presence of an incoming nucleotide in known structures.

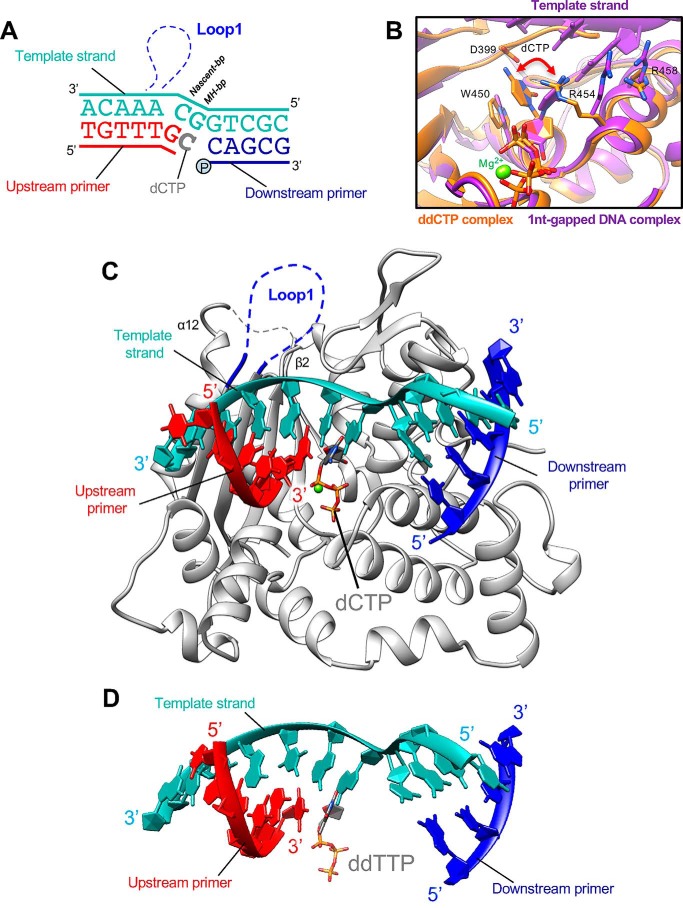

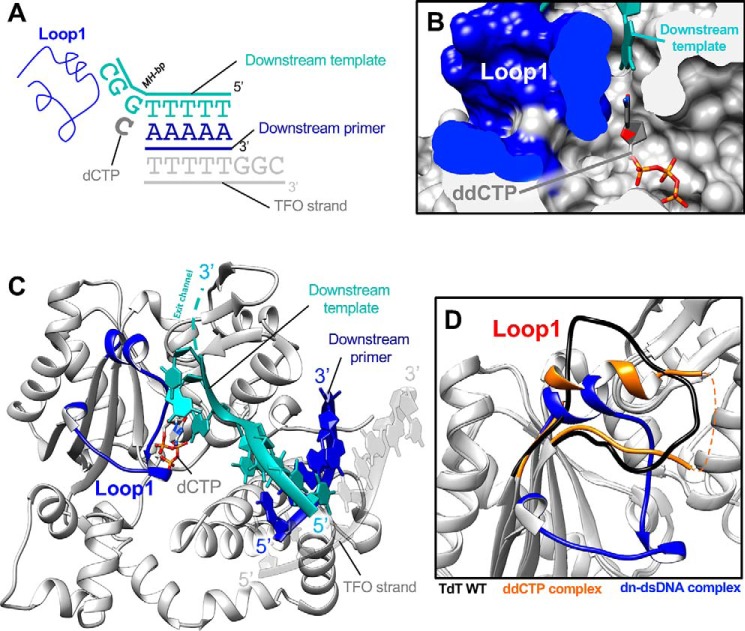

Exchanging Loop1 allows TdT-μ chimera to bind a DNA substrate in a gap-filling mode

To check whether TdT-μ chimera reproduces the known behavior of Pol μ in those cases where structural data are available, we co-crystallized the TdT-μ chimera in complex with a 1-nt-gapped DNA duplex substrate and a nonhydrolyzable nucleotide (Fig. 4A). In this nonhydrolyzable dNTP, the oxygen atom between α- and β-phosphate has been substituted by a carbon atom, to prevent DNA synthesis and to block the enzyme in a precatalytic state. The structure was solved at 2.35 Å resolution with two copies of the complex in the asymmetric unit. The electron density of each one of the DNA bases is well-defined and readily allows the building of the DNA molecules as well as the incoming nucleotide, which makes Watson–Crick interactions with the templating base (Fig. S4A). Binding of the uninterrupted template strand is possible because residues 384–401, corresponding to Loop1, are disordered (Fig. 4C). Such a complex could not be obtained under the same conditions using WT TdT, probably because of its intrinsically ordered Loop1, whereas several similar structures, also showing a disordered Loop1, have been solved with polymerase μ (20, 27, 33).

Figure 4.

Structure of TdT-μ chimera bound to a 1-nt-gapped DNA substrate with an incoming dNTP. A, single-nucleotide-gapped DNA substrate; upstream and downstream primers are represented in red and blue, respectively. The continuous template strand is depicted in cyan, and the incoming nucleotide is in gray. B, detailed view of the differences in the base moiety conformation in the ddCTP binary complex and in the gap-filling complex, accompanied by a change of rotamer in Arg454 and Arg458. C, overall structure of TdT-μ chimera in complex with a gap-filling DNA substrate. Loop1 (in blue) is not visible in electron density. The β2–α12 loop (junction) is indicated in gray dashed lines. D, DNA conformation in Pol μ gap-filling structure, for comparison (PDB entry 2IHM).

The two copies of the same complex in the asymmetric unit have no major difference (RMSD of 0.28 Å over 329 Cα atoms). Their comparison with the corresponding complex with Pol μ shows that the protein structures are very close (RMSD of 1.95 Å over 328 Cα atoms of the protein using PDB entry 2IHM), as well as the DNA molecules; the RMSD is 1.255 Å over 11 nucleotides for the template strand, 1.30 Å for 6 nucleotides in the upstream primer strand, and 1.36 Å over 4 nucleotides for the downstream primer strand (Fig. 4D). In both structures, Loop1 is disordered and gives way to the DNA template strand. One difference involves the β2–α12 loop that appears more flexible in the TdT-μ chimera gap-filling complex because no electron density is present to build residues 452 and 453 (Fig. 4C), whereas the N-terminal part of α12 helix is slightly distorted and shifted by 3.3 Å. Concerning the nucleobase of the incoming dNTP, its orientation is slightly modified compared with the one seen in the ddCTP complex to make a Watson–Crick bp with the templating base, whereas the Arg454 side chain swings to allow this rearrangement (Fig. 4B).

In the TdT-μ chimera gap-filling structure, we used a 5′-phosphorylated downstream primer because the presence of a phosphate group in this position was described to be important for the binding of the downstream DNA strands in Pol μ (33, 34). Importantly, we also tested the gap-filling activity in vitro for the TdT-μ chimera and found that it essentially reproduces the activity of Pol μ and not that of TdT (Fig. S5).

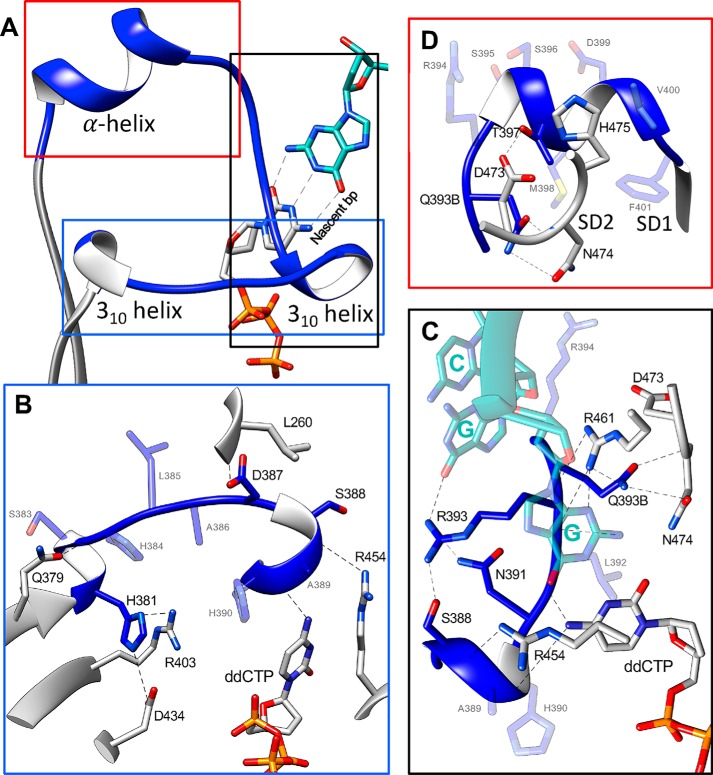

Loop1 checks the in trans nucleotide selection in the absence of a DNA primer strand

By mixing TdT-μ chimera with a 2-fold excess of the dsDNA and an incoming ddCTP, we obtained crystals that lead to a detailed picture of a possible role for Loop1 at 2.09 Å resolution. Unexpectedly, only the downstream dsDNA was visible in the electron density (Fig. S4B), and Loop1 was ordered and actively involved, through its main-chain atoms, in stabilizing the Watson–Crick interactions of the nascent bp with an in trans instructing base. All residues of Loop1, including the side chains, could be manually built (Fig. 5, A and B), and several secondary structure elements were identified, including two sequential 310 helices and an α-helix of 7 residues (Fig. 6A). Notably, no crystal contact is involved in the stabilization of this conformation. The full upstream dsDNA is excluded by Loop1, whereas in TdT's comparable structure, Loop1 just prevents the binding of a continuous template strand but not of the primer strand (Fig. 7D). The incoming ddCTP, which can access the nucleotide binding site through a dedicated channel formed by the 8-kDa and fingers domains, makes Watson–Crick interactions with the first 3′ protruding base of the downstream template strand and nicely fits a cavity created by Loop1 (Fig. 7B), whereas the rest of the protruding bases make their way out of the active site through a separate exit channel, encompassed between Loop1 and the thumb domain (Fig. 7C).

Figure 5.

Ordered structure of Loop1 in TdT-μ chimera bound to the downstream DNA duplex and the incoming dNTP. A, overview of the ternary complex. Loop1 is shown in deep blue and boxed in a red dotted frame. The DNA duplex is in black. The incoming nucleotide is in green. B, electron density in the 2Fo − Fc map (contoured at 1σ in gray) in the Loop1 region of TdT-μ chimera pre-ternary complex. Loop1 is represented in a ball-and-stick model in the context of the adjacent β3 and β4 strands, shown in gray. C, sequence alignments of TdT and Pol μ in the Loop1 region. Loop1 of Pol μ and TdT are delimited with a light blue and pink line, respectively. The interactions between side-chain atoms of Loop1 and the remaining part of TdT are indicated with an asterisk. Strictly conserved residues are shown in red, and residues with similar physico-chemical character are in blue.

Figure 6.

Interaction of Loop1 in the TdT chimera with the downstream dsDNA substrate. A, Loop1 conformation in the TdT-μ chimera–downstream dsDNA ternary complex. The dNTP and the templating base are represented in stick form. B, interaction between the N-terminal part of Loop1 and TdT. C, interaction between the middle part of Loop1 and TdT. D, interaction between the α helix of Loop1 and TdT.

Figure 7.

Structure of TdT chimera as a ternary complex with a downstream dsDNA and the incoming dNTP. A, DNA substrates; the downstream DNA duplex is colored in blue and cyan. The incoming nucleotide and Loop1 are represented in dark gray and blue, respectively. The additional DNA strand, a triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) is represented in gray. B, space-filling representation of the incoming ddNTP-binding site. The ddCTP is in ball-and-stick form, the downstream template strand is in cyan, and the surface of the Loop1 atoms is in dark blue. C, overall structure of the TdT-μ chimera downstream dsDNA. The incoming ddCTP makes Watson–Crick interactions with the in trans template strand. Loop1 is fully visible in the electron density map and is made of two 310 helices and one α helix. The exit channel for the 3′ protruding end is represented by a dashed cyan line. D, differences in the Loop1 conformation in the binary ddCTP complex (gold) and in the downstream dsDNA complex (dark blue). Loop1 conformation of TdT-WT apoenzyme is also represented as a reference (black).

The incoming ddCTP is positioned by Loop1 Pol μ opposite the most downstream template possible (the last ssDNA/template nucleotide before dsDNA), even when another upstream complementary nucleotide is present (Figs. 5A and 7A). This is consistent with previously described studies of template selection by Pol μ (33, 34).

We observe a slight distortion in the catalytic site, where the χ2 angle of the catalytic residue Asp434 (Asp418 in Pol μ) is rotated by 82° compared with the apo-form (Fig. S3). This is due to an interaction with the side chain of His381 (His363 in Pol μ), which is also stabilized by stacking interactions with Arg403. This rotation prevents the correct coordination of metal A in the active site.

Loop1 drastically changes its conformations and is completely remodeled when compared with the ddCTP binary complex (Fig. 7D). It interacts with residues in the fingers domain (Leu260), the palm domain (Gln379, Arg403, and Asp434), and the thumb domain (Arg454, Arg461, Asp473, Asn474, and His475) of the protein (Fig. 6, B–D). The interactions with the incoming base involve only main-chain atoms of Loop1 (Fig. 6C), and the templating base interacts with the conserved residue Arg461, whose mutation into an alanine has a strong deleterious effect in TdT (25). Importantly, all of the interactions of Loop1 in the chimera construct with the rest of the TdT-like structure involve residues that are conserved in Pol μ or subject to a conservative substitution (Fig. 6C). To investigate further how this structure would be modified in the context of the full Pol μ sequence, we modeled this complex using homology modeling techniques. This is justified, considering the high level of sequence identity (42%) between them.

Modeling of the full sequence of Pol μ in the context of the downstream dsDNA complex

Both in the TdT-μ chimera X-ray structure and the Pol μ homology model, the following features were observed. 1) The main-chain atoms of Asn391, Leu392, and Arg393 amino acids stabilize the nascent bp formed by the incoming ddCTP and the template base across strands, but their side-chain atoms play no apparent role. This is shown in Fig. 7B, where residues from Loop1 are represented in surface mode and colored in dark blue, playing the role of the absent upstream dsDNA. Clearly, the check is made at the level of the nascent bp volume, and there is no base specificity: all isosteric bp would be accommodated in the same way in this cavity. 2) There is a direct interaction of the base immediately downstream of the templating base with the side chain of Arg393, which also interacts with the side chains of both Ser388 and Asn391 in Loop1 (Fig. 6C). 3) The side chains of Gln393B and Thr397 make hydrogen bonds with the DNH motif (Asp473, Asn474, and His475), also called the SD2 region (22) or SD2 motif (25) or the thumb mini-loop motif (16), localized in the β8–β9 loop (Fig. 6D). Mutations of this motif in human Pol μ (16) resulted in loss of function. 4) There is a van der Waals contact between Phe401 in region SD1 both with Trp450 and with the SD2 region. F401A mutation human Pol μ (16), resulting in total loss of activity. 5) Both residues Phe401 and Phe405 (SD1) make a sandwich for the side chain of His381 (N terminus of Loop1), thereby clipping both ends of Loop1. The mutation of Phe405 (F387A in human Pol μ), as well as in mouse Pol μ (F391A), resulted in a total loss of function (16, 25). 6) Asp399 side chain stabilizes the short N-terminal helix of Loop1. Its mutation in mouse Pol μ (D385E) resulted in a total loss of function (25).

Interestingly, two arginine residues (Arg454 and Arg458 in TdT, corresponding to Lys438 and Arg442 in Pol μ) are close to position Ser372 (Ser388 in TdT), localized in the middle of Loop1, which is the main cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation site in Pol μ during S and G2 phases (35). A reduced activity of Pol μ was observed when this position was mutated into a glutamate residue, mimicking a phosphorylated serine, suggesting a regulatory mechanism to avoid NHEJ activity in dividing cells. The structure therefore suggests how these two arginines would interact with a phosphorylated serine at position Ser372 and increase the stability of Loop1, thereby preventing the binding of the primer DNA binding and inhibiting the polymerase activity.

It should be noted that a short extra DNA strand forming a triple helix with each dsDNA is present in the electron density map, forming 1A:2T triple bases. This third strand does not interact with the protein, except with Glu67, far away from the active site, but stabilizes packing interactions that occur between neighboring DNA duplexes in the crystal. To check whether the presence of this extra strand could induce an artifactual conformation of the dsDNA in the crystal, we compared its structure with an earlier structure of TdT (PDB code 5D46) with a DSB–DNA synapsis and found that the RMSD is 1.16 Å over the backbone atoms of 12 nucleotides (3 atoms per nucleotide: C4′, C1′, and P) for the downstream dsDNA.

Furthermore, we removed the third strand and performed energy minimization in water; the RMSD of DNA atoms of the TdT-μ chimera was only 0.8 Å, whereas the RMSD on Cα atoms was 1.1 Å.

We also subjected the Pol μ homology model to energy minimization in water in the presence of both ddCTP and the down-dsDNA. After equilibration, the RMSD on DNA atoms was 0.8 and 1.0 Å for the protein Cα atoms. Notably, Loop1 conformation was remarkably stable.

Flexibility of Loop1 allows Pol μ to interact with a full DNA synapsis

We also solved the structure of TdT-μ chimera bound to a full DSB–DNA substrate (a DNA synapsis) and with an incoming ddCTP, at 2.55 Å resolution, by increasing the dsDNA/protein ratio to 4:1 instead of 2:1. This time, both upstream and downstream dsDNA can be fully built in the electron density map (Fig. S4C). The TdT-μ chimera DSB–DNA structure is highly similar to the TdT-WT DSB–DNA structure (RMSD of 0.504 Å over 336 Cα atoms with PDB entry 5D46). Moreover, ddCTP is present in the nucleotide-binding pocket and makes Watson–Crick interactions with the first single base at the 3′ protruding end of the downstream dsDNA molecule (across strands). Loop1 appears to be disordered in this structure, so that it does not sterically hinder the binding of the template strand (Fig. 8, A and B), as observed in the TdT-μ chimera structure in a gap-filling mode (Fig. 4).

Figure 8.

Structure of TdT chimera bound to the full DNA synapsis and incoming dNTP. A, DNA substrates; the downstream DNA duplex is colored in blue and cyan, and the upstream duplex is in red and yellow (primer strand and template strand). Incoming nucleotide and Loop1 are represented in gray and blue, respectively. The two additional DNA strands, a triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO), are represented in gray. B, overall structure of TdT-μ chimera full DNA synapsis complex. The incoming dCTP makes Watson–Crick interactions with in trans template strand. Loop1 is mostly invisible in the electron density map and represented by blue dashed lines.

A third DNA strand is present on each DNA duplex, forming a triple helix with a 1A:2T stoichiometry (Fig. 8A). As described above, these additional strands help to stabilize interactions in the crystal-packing arrangement, but they do not interact directly with the protein. They also do not directly participate in the stabilization of the DNA synapsis itself, as observed in the TdT-WT DSB–DNA complex. To check whether the presence of this extra strand could induce an artifactual conformation of the DNA in the crystal, we compared its structure with the known structure of TdT with a DSB–DNA synapsis; the RMSD is 0.5 Å over 6 nucleotides for the upstream primer, 5 nucleotides for the downstream primer strand, and 6 backbones for the downstream template strand (with 3 backbone atoms per nucleotide). We note that the third DNA strand is not in the same direction in the downstream and upstream parts of the synapsis.

In summary, it is possible to crystallize the TdT-μ chimera construct in the context of a full DNA–DSB junction, but in this case, Loop1 is lifted up and moved out of the way of the upstream DNA duplex, as if it is not needed any more once it has played its role to select the base in front of the in trans templating base.

Discussion

The studies presented here provide the first atomic structure for two DNA ends brought close together by a protein that recapitulates the properties of a Pol X DNA polymerase involved in the NHEJ machinery, in this case Pol μ, in ligation experiments.

Comparison of Pol X activities during NHEJ in the presence of different 3′ ends

The biochemical ligation tests using Ku 70/80, XRCC4–ligase IV, and either the full-length TdT, Pol μ, or TdT-μ chimera provide useful insights into the role of Pol X polymerases in NHEJ (Fig. 2). First, TdT robustly adds nucleotides in a template-independent manner prior to ligation in the case of incompatible DNA ends. However, TdT does not add nucleotides when compatible DNA ends are being joined. This illustrates that the collision and annealing of the DNA ends is rapid relative to the encounter of those ends with the Pol X polymerase. This observation confirms and extends previous work showing that when DNA end structures are compatible, then new synthesis is suppressed. This was indeed apparent in very early work before specific proteins were identified for NHEJ (36, 37). More recently, the degree of Pol X engagement was shown to be directly proportional to the extent to which there was a barrier to direct ligation (due to sequence overhang incompatibility), both in vitro and in vivo, for Pol λ (38).

Second, for incompatible DNA ends, Pol μ usually adds nucleotides that generate terminal microhomology. But in ∼25% of instances in the experiments here for this configuration, it appears that Pol μ adds at least 1 nucleotide in a template-independent manner. This raises the possibility that the microhomology nucleotide is also template-independent, and we are only observing the subset of events where Pol μ added, by chance, a nucleotide that provided 1 bp of terminal microhomology. The remaining nucleotides could reflect fill-in synthesis by Pol μ in a template-dependent manner. The clearest tests of template-dependent versus template-independent addition by Pol μ are with dideoxynucleotides or immobilized DNA ends (33, 39, 40), and in these tests, Pol μ shows both template-independent and template-dependent activity. Our in trans structural studies show synthesis across a discontinuous template by both Pol μ and TdT-μ chimera (15). All of the aforementioned biochemical and structural data are consistent with the original conception of Pol μ's ability to cross a discontinuous template (39).

Most importantly for this study, in the NHEJ biochemical assays using TdT-μ chimera, the nucleotide additions are much more like those of Pol μ than of TdT. This illustrates the importance of Loop1 in the distinction between TdT and Pol μ, directly in the context of NHEJ, and validates that TdT-μ chimera can be used to characterize the role of Loop1 in Pol μ and the SD1 region at the structural level.

Loop1 in the context of the Pol X family: Positioning SD1 and SD2 regions

The length of Loop1 is one of the main differences observed among members of the polymerase X family. This loop is composed of only 4 and 9 amino acids in polymerase β and polymerase λ, respectively, whereas Loop1 is made up of 20 amino acids in TdT and 17–21 residues in polymerase μ (Fig. 5C). All structures of individual members of this family were solved by X-ray crystallography. Loop1 can be observed in Pol β, Pol λ, and TdT structures, but not in any of the currently available Pol μ structures (this loop is too small in Pol β and Pol λ to interfere with the template DNA path). At the sequence level, Loop1 is more conserved in TdT sequences than in Pol μ sequences, and there seems to be an inverse correlation between sequence conservation and flexibility of Loop1. Indeed, Loop1 always adopts the same fixed correlated conformation in TdT, where the sequence conservation is high. On the other hand, Loop1 sequence is more divergent in Pol μ, resulting in an increased flexibility of this loop in Pol μ.

Just downstream of Loop1, there is an important region called SD1 that is differentially conserved in Pol μ and TdT (Figs. 1B and 5C). Our structures indicate that Loop1 ordering in the complex with the down-dsDNA is responsible for the new positioning of the SD1 region (located at the C terminus of Loop1) with respect to the SD2 region and the catalytic site (Fig. 6), and this probably explains its importance for functional aspects of Pol μ.

For Pol λ, Loop1 is too short to play the role described here. However, Loop3, coming from the down-dsDNA side, might be able to play a similar role, as suggested by the superimposition of the different structures in a recent review (26). Answering this question will require additional structural studies of Pol λ in the context of a true DNA synapsis, as we have done here.

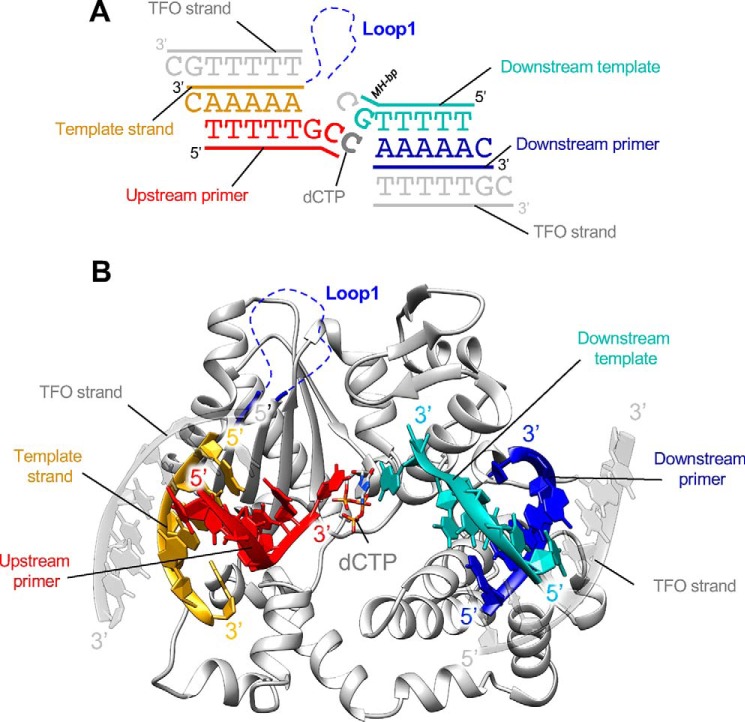

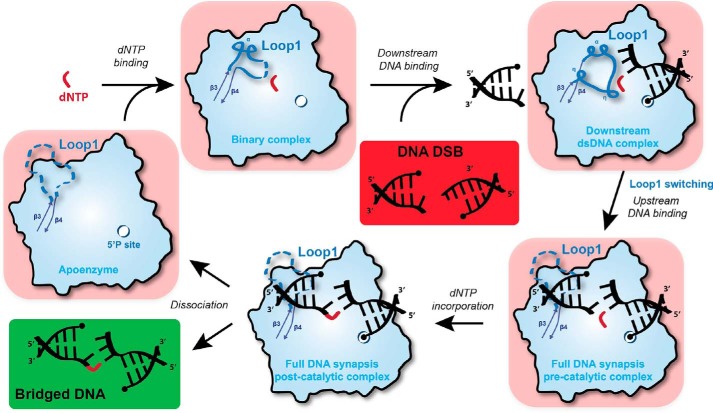

Sequence of conformational changes during Pol μ catalytic cycle in the presence of 3′ overhanging DNA ends

Recent studies have provided a wealth of structural and biochemical information about the DNA-bridging binding properties of eukaryotic Pol X polymerases (15, 26). Nevertheless, the order of substrate binding as well as the role of Loop1 for Pol μ activity in the NHEJ pathway remains a central unknown aspect. The new structural information revealed here by using TdT-μ protein may be organized as follows to explain the function of Loop1 during the NHEJ pathway in the presence of 3′ protruding ends by Pol μ (Fig. 9). First, our data on the binary complex with dNTP would be compatible with the idea that Pol μ is always “loaded” with a dNTP (see below). When a DSB is detected and stabilized by Ku heterodimer, Pol μ–dNTP complex would bind preferentially to the downstream DNA duplex, due to the presence of a 5′-phosphate binding pocket. In this process, Loop1 is rearranged to stabilize Watson–Crick interactions in the microhomology bp across strands and excludes the binding of the up-dsDNA. Subsequently, Loop1 would be displaced by the up-dsDNA positioning, driven by base-stacking interactions. Pol μ would then catalyze nucleotide incorporation to the primer DNA, allowing bridging between upstream and downstream dsDNA, followed by dissociation of the complex. Therefore, the catalytic cycle contains a separate step that checks Watson–Crick interactions at the nascent bp, independently of the upstream DNA molecule. This suggests for the first time a structural basis for the role of the specific Loop1 of Pol μ that includes the selection of the incoming nucleotide before binding the primer strand.

Figure 9.

Sequential model of Pol μ activity in the presence of a DSB DNA with 3′ protruding ends. Initially, a complex composed of free Pol μ (apoenzyme) and dNTP is formed. The binding of downstream dsDNA, strengthened by the 5′ phosphate-binding pocket, modifies Loop1 conformation to favor Watson–Crick interactions in the nascent bp but also prevents the binding of upstream dsDNA, including the primer. Subsequently, Loop1 is moved away, and the upstream dsDNA is recruited (DSB full synaptic complex), allowing nucleotide incorporation on the upstream primer (DSB post-catalytic complex). Finally, the enzyme and the bridged DNA dissociate to allow for the action of ligase IV. If the incoming dNTP does not form a Watson–Crick bp with the downstream template DNA end, then it is possible that the ternary complex (downstream duplex + dNTP-Pol μ) will disassemble. If the complex does not fall apart and the mismatched nucleotide is incorporated, then this would account for the low level of template-independent addition that is seen in Fig. 2C (bottom two boxes).

This step is actually the major difference between TdT and Pol μ, because such an intermediate state was never detected during extensive crystallization trials at various WT TdT/DNA ratios. Indeed, Loop1 is always ordered in TdT and structured in such a way that it excludes the upstream template strand, but not the upstream primer strand, Ref. 42 by Ref. 26. This further highlights the imporatance of stacking interactions between the incoming nt and the 3′ base of the primer in TdT, which indeed are known to play a major role in the nature of sequences added (13, 30).

Similarity with the bacterial NHEJ system

Loop1 is mostly ordered in the binary structure with dNTP–Mg2+, in the absence of any primer strand (Fig. 9). Strikingly, the same type of intermediate structure is also present in bacterial Pol X from T. thermophilus (43), where it was suggested that the bacterial Pol X is always present in solution as a complex with one of the four dNTPs. This is important because phylogenetic studies of the Pol X family (43) suggest that eukaryotic Pol X members involved in NHEJ have a bacterial origin. We note that if the polymerase is already loaded with a dNTP prior to its binding to a synapsis of two DNA ends, it may incorporate a nucleotide that does not match the downstream DNA end, resulting in a template-independent mode (39). This is a critical point highlighted by our study.

In bacteria, NHEJ is promoted by PolDom, a member of the archaeo-eukaryotic primase (AEP) superfamily, whose folding is different from that of the Pol X family. In the bacterial Mycobacterium tuberculosis PolDom structure, there is also an intermediate state that contains the incoming nucleotide and only the downstream dsDNA (with no upstream dsDNA) and also a mobile loop, called Loop2, that can adopt two conformations and regulate the binding of a catalytic metal ion in the polymerase active site (24). The rotation of the side chain of one of the catalytic aspartates that interacts with an arginine belonging to Loop2 leads to an inactive catalytic site (Fig. S6). The relevance of such a complex in solution was demonstrated using FRET experiments and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (24). Although Loop1 of Pol μ is neither structurally nor topologically related in any way to Loop2 of PolDom, both loops intervene in stabilizing the catalytic site conformation. Also, both loops are able to promote the complete exclusion of the upstream dsDNA. It was postulated for PolDom that this preliminary step is responsible for nucleotide selection, prior to DNA bridging at the DSB site. The fact that similar observations can be made in the prokaryotic and eukaryotic NHEJ pathways suggests that this mechanism, which dissociates DNA bridging and fidelity, may have been selected twice in evolution. Because the folding topologies of the polymerases involved in this reaction are different, we may speak of convergent evolution for the mechanism of base selection by the NHEJ polymerase in bacterial (AEP family) and eukaryotic (Pol X family) systems.

In conclusion, the set of proposed structures of intermediates in the catalytic cycle of Pol μ described here represents a paradigm shift in the base selection mechanism in the Pol X family of DNA polymerases. Because of the high quality in the atomic details of this set of structures and of the high sequence identity between Pol μ and the Tdt-μ chimera, we can reliably model Pol μ in the context of the proposed complexes along the catalytic cycle, which might, ultimately, help in the rational design of inhibitors specific to this step of NHEJ and DNA repair, during which the DNA ends are made compatible before ligation.

Experimental procedures

Cloning and protein purification

The catalytic domain of mouse TdT and mouse TdT-μ was expressed and purified using the protocol described previously (25). The catalytic domain of human Pol μ was cloned, expressed, and purified using the protocol described previously (27). The full-length sequences of mouse TdT and mouse Pol μ were cloned into RSFDuet-1 expression vector (Novagen) fused to an N-terminal 14-histidine tag followed by a cleavage site for tobacco etch virus protease. The full-length sequence of TdT-μ chimera contains the BRCT (breast cancer susceptibility C terminus) domain of mouse Pol μ (residues 1–140), the catalytic domain of mouse TdT (residues 141–510), and Loop1 of mouse Pol μ (residues 378–406).

To keep the original TdT residue numbering everywhere, including after Loop1, the Gln394 residue that is an insertion between the two Loop1 sequences is labeled differently (393B, Fig. 1B).

Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL strain in Luria broth at 20 °C for 16 h after induction by 0.5 mm isopropyl-d-thiogalactoside. The purification was done using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) chromatography, followed by overnight tobacco etch virus cleavage and heparin chromatography (GE Healthcare). All proteins were stored at −20 °C in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, 300 mm NaCl, and 15% glycerol.

Recombinant Ku70/80 and recombinant XRCC4–ligase IV were expressed and purified as described previously (44, 45). Proteins were expressed using a baculovirus system in High Five cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ku 70/80 was purified by Ni-NTA–affinity, dsDNA (oligonucleotide)-affinity, and size-exclusion chromatography. XRCC4–ligase IV was purified by Ni-NTA–affinity and two-step ion-exchange chromatography.

Oligonucleotides and DNA substrates

Oligonucleotides used for the NHEJ assay were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Oligonucleotides were purified using 12% denaturing PAGE, and their concentration was determined by UV spectroscopy. 5′ end radiolabeling of oligonucleotides was performed using [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mol) (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Unincorporated radioisotope was removed using Sephadex G-25 spin columns (Epoch Life Science). Duplex DNA substrates were created by adding a 20% excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide to the radiolabeled complementary strand. DNA substrates were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and cooled at room temperature for 3 h and then at 4 °C overnight. Sequences of oligonucleotides used in this study are as follows: CG07, 5′-C*G*T* T*AA GTA TCT GCA TCT TAC TTG ATG GAG GAT CCT GTC ACG TGC TAG ACT ACT GGT CAA GCG CAT CGA GAA CCC CCC-3′; HC102, 5′-GGT TCT CGA TGC GCT TGA CCA GTA GTC TAG CAC GTG ACA GGA TCC TCC ATC AAG TAA GAT GCA GAT ACT TAA CG-biotin-3′; HC105, 5′-CTA GAC TAC TGG TCA AGC-3′; HC114, 5′-TGT ACA TAT ATC AGT GTC TG-3′; HC115, 5′-GAT GCC TCC AAG GTC GAC GAT GCA GAC ACT GAT ATA TGT ACA GAT TCG GTT GAT CAT AGC ACA ATG CCT GCT GAA CCC ACT ATC G-3′; HC116, 5′-biotin-CGA TAG TGG GTT CAG CAG GCA TTG TGC TAT GAT CAA CCG AAT CTG TAC ATA TAT CAG TGT CTG CAT CGT CGA CCT TGG AGG CAT CGG GG-3′; HC119, 5′-biotin-CGA TAG TGG GTT CAG CAG GCA TTG TGC TAT GAT CAA CCG AAT CTG TAC ATA TAT CAG TGT CTG CAT CGT CGA CCT TGG AGG CAT CTT TT-3′; JG163, 5′-GTT AAG TAT CTG CAT CTT ACT TGA CGG ATG CAA TCG TCA CGT GCT AGA CTA CTG GTC AAG CGG ATC GGG CTC GAC C-3′; JG166, 5′-CGA GCC CGA TCC GCT TGA CCA GTA GTC TAG CAC GTG ACG ATT GCA TCC GTC AAG TAA GAT GCA GAT ACT TAA CAG G-3′. Asterisks indicate phosphorothioate linkages.

Oligonucleotides used for the polymerase activity test were purchased from Eurogentec and dissolved in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 1 mm EDTA. Concentrations were measured by UV absorbance using the absorption coefficient ϵ at 260 nm provided by Eurogentec. Primer strand was 5′-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences; 3000 Ci/mm) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 37 °C. The labeling reaction was stopped by heating the kinase at 75 °C for 10 min. Upstream (5′-TAC GCA TTA GCC TG) and downstream (5′-P-GGC TAA TGC GTA) primers were mixed with template strand (5′-TAC GCA TTA GCC CCA GGC TAA TGC GTA), heated for 5 min up to 90 °C, and slowly cooled to room temperature overnight.

NHEJ assay

In vitro NHEJ assays were performed as described previously (57). Briefly, NHEJ components were incubated with DNA substrates as indicated at 37 °C for 1 h. Markers were generated under the same conditions. Reactions were terminated by heating at 95 °C for 10 min, and samples were subsequently deproteinized using phenol-chloroform extraction. Extracted DNA was resolved using 8% denaturing PAGE and detected by autoradiography. Ligation efficiency was quantitated using Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad).

Junction sequence analysis

Sequence analysis of ligated DNA junctions was performed as described previously (57). Briefly, DNA was visualized by exposing dried radioactive gels to an X-ray film overnight. Ligated DNA products were eluted from the gel, and junction sequences were amplified from these products using PCR primers HC105 and HC114. Amplified junction sequences were TA-cloned into pGEM-T Easy vectors (Promega) and transformed into electrocompetent DH10B cells. Transformed cells were plated on Luria broth-agar/ampicillin/X-gal, and white colonies were selected for sequencing.

Crystallization and data collection

The dsDNA 5′-AAAAA and 5′-TTTTTGG (or 5′-TTTTTG) or gap-filling DNA (upstream primer, 5′-TGTTTG; downstream primer, 5′-CAGCG; template, 5′-CGCTGGCAAACA) were annealed in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.8, 5 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm EDTA. TdT-μ chimera was mixed at a final concentration of 10 mg ml−1, with ddCTP (2 mm), with ddCTP (2 mm), and a 2 (or 4)-fold excess of dsDNA or with dCpCpp (2 mm) and a 2-fold excess of gap-filling DNA, in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 200 mm NaCl, 100 mm ammonium sulfate, and 50 mm magnesium acetate. All complexes were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h.

Crystals of TdT-μ chimera alone (apoenzyme) or mixed with ddCTP grew in 1 day at 18 °C by mixing of 1 μl of concentrated protein at 10 mg ml−1 and 1 μl of mother liquor solution containing 20–24% PEG 6000, 400–800 mm lithium chloride, and 100 mm MES, pH 6. Crystals of TdT-μ chimera in the presence of nucleotide and dsDNA or gap-filling DNA (1 μl of complex + 1 μl of mother liquor) grew in 1 day at 18 °C in a solution containing 19–25% PEG 4000, 100–400 mm lithium sulfate, and 100 mm Tris, pH 8.5. Crystals were cryo-protected using one soaking step with 25% glycerol and then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray data collections were collected at the Soleil Synchrotron (Saint-Aubin, France) on Beamline Proxima-1 and at ESRF (Grenoble, France) on Beamlines ID23-1, ID23-2, and ID29.

Data processing, crystallographic refinement, and model validation

Diffraction data sets were processed using XDS (41) and CCP4 (46, 47). Crystals of TdT-μ chimera apoenzyme alone or bound to ddCTP belong to space group P212121 and diffract at 2.20 and 1.96 Å resolution, respectively. Crystals of TdT-μ chimera in the presence of a 2-fold excess of dsDNA A5/T5GG and ddCTP diffract at 2.09 Å resolution and belong to space group P21212. Crystals of TdT-μ chimera in the presence of a 4-fold excess of dsDNA A5/T5G and ddCTP diffract at 2.55 Å and belong to space group P21. Finally, crystals of TdT-μ chimera in the gap-filling mode with a continuous template strand and dCpcpp diffract to 2.35 Å and belong to space group C2 with two molecules of TdT-μ chimera per asymmetric unit. Molecular replacement was performed with the program Phaser using the PDB file 1JMS as a search model (48). Manual building by iterative cycles of model building and refinement was carried out with the software COOT (49) and BUSTER (50), using TLS parameters (51) in the last stages of refinement. The number of TLS groups was chosen by default by the program Buster. The quality of the models was assessed using MolProbity (42). Data collection and refinement statistics are reported in Table S1. Superimpositions of structures and figures were performed and generated with Chimera (52).

Modeling Pol μ complex with the incoming dNTP and the in trans templating strand (down-dsDNA)

We modeled the complete Pol μ sequence on the template of the TdT-μ chimera in a frozen backbone conformation, keeping intact the side chains of conserved residues (46%). We optimized the rotamers of the nonconserved residues globally using our mean field optimization algorithm implemented on our web server, http://lorentz.dynstr.pasteur.fr/pdb_hydro.php6 (53). No major clash was observed between the modeled side chains or with the DNA in the resulting model. The model with both the incoming dCTP (and Mg2+) and the down-dsDNA (without the third DNA strand) was inserted in a cubic box of dimensions such that the distance between the protein and the edges was at least 12 Å. The TIP3P water model was used, and Na+ ions were added to neutralize the total charge of the system. Force field parameters for dCTP were obtained with CGENFF, and the CHARMM36 force field was used for the rest of the system (54). All simulation runs were performed using NAMD (55). The package PSFGEN was used within VMD (56) to build missing atoms and create input files for NAMD. 50,000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimization were performed, and 1000 frames were collected; convergence occurred after about 15,000 cycles (Fig. S7).

Author contributions

J. L. validation; J. L., C. A. G., S. R., M. T., M. R. L., and M. D. investigation; J. L. writing-original draft; C. A. G., M. R. L., and M. D. writing-review and editing; M. R. L. and M. D. supervision; M. R. L. and M. D. funding acquisition; M. D. conceptualization; M. D. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of synchrotrons SOLEIL (Saint-Aubin, France) and ESRF (Grenoble, France) for assistance using beamlines and help during diffraction data collection. We thank L. Deriano (IP) and B. Bertocci (INSERM) for helpful discussions and B. Bertocci for the full-length constructs of TdT and Pol μ. We thank PF6 (Institut Pasteur) for help in crystallogenesis experiments.

This work was supported by the “Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur la cancer” through a postdoctoral fellowship (to J. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 6GO3, 6GO4, 6GO5, 6GO6, and 6GO7) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

This article contains Table S1 and Figs. S1–S7.

F. Romain, I. Barbosa, J. Gouge, F. Rougeon, and M. Delarue, unpublished results.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- DSB

- double-strand break(s)

- HR

- homologous recombination

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous DNA end joining

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- down-dsDNA

- downstream dsDNA

- up-dsDNA

- upstream dsDNA

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- AEP

- archaeo-eukaryotic primase

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- TLS

- translation–libration–screw

- bp

- base pair

- WT

- wild-type.

References

- 1. Mao Z., Bozzella M., Seluanov A., and Gorbunova V. (2008) DNA repair by nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination during cell cycle in human cells. Cell Cycle 7, 2902–2906 10.4161/cc.7.18.6679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heyer W.-D. (2007) Biochemistry of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Top. Curr. Genet. 17, 95–133 10.1007/978-3-540-71021-9_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waters C. A., Strande N. T., Wyatt D. W., Pryor J. M., and Ramsden D. A. (2014) Nonhomologous end joining: a good solution for bad ends. DNA Repair (Amst.) 17, 39–51 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iyama T., and Wilson D. M. 3rd (2013) DNA repair mechanisms in dividing and non-dividing cells. DNA Repair (Amst.) 12, 620–636 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lieber M. R. (2008) The mechanism of human nonhomologous DNA end joining. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1–5 10.1074/jbc.R700039200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang K., Guo R., and Xu D. (2016) Non-homologous end joining: advances and frontiers. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 48, 632–640 10.1093/abbs/gmw046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahajan K. N., Gangi-Peterson L., Sorscher D. H., Wang J., Gathy K. N., Mahajan N. P., Reeves W. H., and Mitchell B. S. (1999) Association of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase with Ku. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13926–13931 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malu S., De Ioannes P., Kozlov M., Greene M., Francis D., Hanna M., Pena J., Escalante C. R., Kurosawa A., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Adachi N., Vezzoni P., Villa A., Aggarwal A. K., and Cortes P. (2012) Artemis C-terminal region facilitates V(D)J recombination through its interactions with DNA ligase IV and DNA-PKcs. J. Exp. Med. 209, 955–963 10.1084/jem.20111437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mickelsen S., Snyder C., Trujillo K., Bogue M., Roth D. B., and Meek K. (1999) Modulation of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase activity by the DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Immunol. 163, 834–843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benedict C. L., Gilfillan S., Thai T. H., and Kearney J. F. (2000) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and repertoire development. Immunol. Rev. 175, 150–157 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2000.imr017518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landau N. R., Schatz D. G., Rosa M., and Baltimore D. (1987) Increased frequency of N-region insertion in a murine pre-B-cell line infected with a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase retroviral expression vector. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 3237–3243 10.1128/MCB.7.9.3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desiderio S. V., Yancopoulos G. D., Paskind M., Thomas E., Boss M. A., Landau N., Alt F. W., and Baltimore D. (1984) Insertion of N regions into heavy-chain genes is correlated with expression of terminal deoxytransferase in B cells. Nature 311, 752–755 10.1038/311752a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bollum F. J. (1978) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: biological studies. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 47, 347–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kato K. I., Gonçalves J. M., Houts G. E., and Bollum F. J. (1967) Deoxynucleotide-polymerizing enzymes of calf thymus gland. II. Properties of the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 2780–2789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loc'h J., Rosario S., and Delarue M. (2016) Structural basis for a new templated activity by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: implications for V(D)J recombination. Structure 24, 1452–1463 10.1016/j.str.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin M. J., and Blanco L. (2014) Decision-making during NHEJ: a network of interactions in human Polμ implicated in substrate recognition and end-bridging. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 7923–7934 10.1093/nar/gku475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aoufouchi S., Flatter E., Dahan A., Faili A., Bertocci B., Storck S., Delbos F., Cocea L., Gupta N., Weill J. C., and Reynaud C. A. (2000) Two novel human and mouse DNA polymerases of the polX family. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 3684–3693 10.1093/nar/28.18.3684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Domínguez O., Ruiz J. F., Laín de Lera T., García-Díaz M., González M. A., Kirchhoff T., Martínez-A C. Bernad A., and Blanco L. (2000) DNA polymerase μ (Pol μ), homologous to TdT, could act as a DNA mutator in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 19, 1731–1742 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delarue M., Boulé J. B., Lescar J., Expert-Bezançon N., Jourdan N., Sukumar N., Rougeon F., and Papanicolaou C. (2002) Crystal structures of a template-independent DNA polymerase: murine terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. EMBO J. 21, 427–439 10.1093/emboj/21.3.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moon A. F., Garcia-Diaz M., Bebenek K., Davis B. J., Zhong X., Ramsden D. A., Kunkel T. A., and Pedersen L. C. (2007) Structural insight into the substrate specificity of DNA Polymerase mu. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 45–53 10.1038/nsmb1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrade P., Martín M. J., Juárez R., López de Saro F., and Blanco L. (2009) Limited terminal transferase in human DNA polymerase μ defines the required balance between accuracy and efficiency in NHEJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16203–16208 10.1073/pnas.0908492106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Romain F., Barbosa I., Gouge J., Rougeon F., and Delarue M. (2009) Conferring a template-dependent polymerase activity to terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase by mutations in the Loop1 region. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4642–4656 10.1093/nar/gkp460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Juárez R., Ruiz J. F., Nick McElhinny S. A., Ramsden D., and Blanco L. (2006) A specific loop in human DNA polymerase μ allows switching between creative and DNA-instructed synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 4572–4582 10.1093/nar/gkl457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brissett N. C., Martin M. J., Pitcher R. S., Bianchi J., Juarez R., Green A. J., Fox G. C., Blanco L., and Doherty A. J. (2011) Structure of a preternary complex involving a prokaryotic NHEJ DNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 41, 221–231 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gouge J., Rosario S., Romain F., Poitevin F., Béguin P., and Delarue M. (2015) Structural basis for a novel mechanism of DNA bridging and alignment in eukaryotic DSB DNA repair. EMBO J. 34, 1126–1142 10.15252/embj.201489643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loc'h J., and Delarue M. (2018) Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase: the story of an untemplated DNA polymerase capable of DNA bridging and templated synthesis across strands. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 53, 22–31 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moon A. F., Pryor J. M., Ramsden D. A., Kunkel T. A., Bebenek K., and Pedersen L. C. (2014) Sustained active site rigidity during synthesis by human DNA polymerase μ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 253–260 10.1038/nsmb.2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gouge J., Rosario S., Romain F., Beguin P., and Delarue M. (2013) Structures of intermediates along the catalytic cycle of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase: dynamical aspects of the two-metal ion mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 4334–4352 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakane S., Ishikawa H., Nakagawa N., Kuramitsu S., and Masui R. (2012) The structural basis of the kinetic mechanism of a gap-filling X-family DNA polymerase that binds Mg2+-dNTP before binding to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 417, 179–196 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gauss G. H., and Lieber M. R. (1996) Mechanistic constraints on diversity in human V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 258–269 10.1128/MCB.16.1.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freudenthal B. D., Beard W. A., and Wilson S. H. (2012) Structures of dNTP intermediate states during DNA polymerase active site assembly. Structure 20, 1829–1837 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sawaya M. R., Prasad R., Wilson S. H., Kraut J., and Pelletier H. (1997) Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: evidence for an induced fit mechanism. Biochemistry 36, 11205–11215 10.1021/bi9703812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moon A. F., Gosavi R. A., Kunkel T. A., Pedersen L. C., and Bebenek K. (2015) Creative template-dependent synthesis by human polymerase mu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4530–E4536 10.1073/pnas.1505798112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pryor J. M., Waters C. A., Aza A., Asagoshi K., Strom C., Mieczkowski P. A., Blanco L., and Ramsden D. A. (2015) Essential role for polymerase specialization in cellular nonhomologous end joining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4537–E4545 10.1073/pnas.1505805112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Esteban V., Martin M. J., and Blanco L. (2013) The BRCT domain and the specific loop 1 of human Polμ are targets of Cdk2/cyclin A phosphorylation. DNA Repair (Amst.) 12, 824–834 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thode S., Schäfer A., Pfeiffer P., and Vielmetter W. (1990) A novel pathway of DNA end-to-end joining. Cell 60, 921–928 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90340-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roth D. B., and Wilson J. H. (1986) Nonhomologous recombination in mammalian cells: role for short sequence homologies in the joining reaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 4295–4304 10.1128/MCB.6.12.4295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Waters C. A., Strande N. T., Pryor J. M., Strom C. N., Mieczkowski P., Burkhalter M. D., Oh S., Qaqish B. F., Moore D. T., Hendrickson E. A., and Ramsden D. A. (2014) The fidelity of the ligation step determines how ends are resolved during nonhomologous end joining. Nat. Commun. 5, 4286 10.1038/ncomms5286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gu J., Lu H., Tippin B., Shimazaki N., Goodman M. F., and Lieber M. R. (2007) XRCC4:DNA ligase IV can ligate incompatible DNA ends and can ligate across gaps. EMBO J. 26, 1010–1023 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nick McElhinny S. A., Havener J. M., Garcia-Diaz M., Juárez R., Bebenek K., Kee B. L., Blanco L., Kunkel T. A., and Ramsden D. A. (2005) A gradient of template dependence defines distinct biological roles for family X polymerases in nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cell 19, 357–366 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 10.1107/S0907444909042073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bienstock R. J., Beard W. A., and Wilson S. H. (2014) Phylogenetic analysis and evolutionary origins of DNA polymerase X-family members. DNA Repair (Amst.) 22, 77–88 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gerodimos C. A., Chang H. H. Y., Watanabe G., and Lieber M. R. (2017) Effects of DNA end configuration on XRCC4-DNA ligase IV and its stimulation of Artemis activity. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 13914–13924 10.1074/jbc.M117.798850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma Y., Pannicke U., Schwarz K., and Lieber M. R. (2002) Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell 108, 781–794 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00671-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 10.1107/S0907444905036693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Evans P. R. (2011) An introduction to data reduction: space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 282–292 10.1107/S090744491003982X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., and Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 10.1107/S0021889807021206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bricogne G., Blanc E., Brandl M., Flensburg C., Keller P., Paciorek W., Roversi P., Sharff A., Smart O. S., Vonrhein C., and Womack T. O. (2011) Buster version 2.11.2, Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- 51. Painter J., and Merritt E. A. (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 439–450 10.1107/S0907444906005270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Azuara C., Lindahl E., Koehl P., Orland H., and Delarue M. (2006) PDB_Hydro: incorporating dipolar solvents with variable density in the Poisson-Boltzmann treatment of macromolecule electrostatics. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W38–W42 10.1093/nar/gkl072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang J., and MacKerell A. D. Jr. (2013) CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2135–2145 10.1002/jcc.23354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., and Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chang H. H. Y., Watanabe G., Gerodimos C. A., Ochi T., Blundell T. L., Jackson S. P., and Lieber M. R. (2016). Different DNA End Configurations Dictate Which NHEJ Components Are Most Important for Joining Efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 24377–24389 10.1074/jbc.M116.752329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.