Abstract

Introduction

A growing body of literature has demonstrated that cancer patients have a higher risk of suicide and cardiovascular mortality compared with the general population, especially immediately after a cancer diagnosis. Using data from the National Cancer Registry in Japan launched in January 2016, we will conduct the first nationwide population-based study in Japan to compare incidence of death by suicide, other externally caused injuries (ECIs) and cardiovascular disease following a cancer diagnosis with that of the general population in Japan. We will also aim to identify the patient subgroups and time periods associated with particularly high risk.

Methods and analysis

Our study subjects will consist of cancer cases diagnosed between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2016 in Japan and they will be observed until 31 December 2018. We will calculate standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) and excess absolute risks (EARs) for suicide, other ECIs and cardiovascular death compared with the general population in Japan, after adjustment for sex, age and prefecture. SMRs and EARs will be calculated separately in relation to a number of factors: sex; age at diagnosis; time since cancer diagnosis; prefecture of residence at diagnosis; primary tumour site; behaviour code of tumour; extension of tumour; whether definitive surgery of the primary site was performed; and presence/absence of multiple primary tumours.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the National Cancer Center Japan and Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences. The findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

UMIN000035118; Pre-results.

Keywords: neoplasms, suicide, cardiovascular diseases, registries, standardised mortality ratio

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be the first nationwide population-based study in Japan to investigate the impact of a cancer diagnosis on subsequent death by suicide, other externally caused injuries and cardiovascular events.

Our study will cover virtually all cancer incidence and subsequent fatal outcomes in Japan.

Our study will not be able to control for potential confounding factors for cancer, suicide and cardiovascular events, such as smoking history and alcohol use, sociodemographic status and pre-existing medical and psychiatric conditions.

Introduction

In Japan, it is estimated that ~1 million people have been newly diagnosed with cancer annually in recent years, and about 1 in 2 Japanese will receive a cancer diagnosis during their lifetime.1

Receiving a cancer diagnosis and undergoing diagnostic workup leading to a definite cancer diagnosis are highly stressful experiences for cancer patients, and a high prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and disorders has been observed around the time of a cancer diagnosis.2 3 A number of population-based studies have consistently demonstrated that patients with cancer are at increased risk for suicide,4–15 especially in the weeks after their cancer diagnosis.16–19 A high incidence of other externally caused injuries (ECIs), including accidental death and death due to events of undetermined intent, has also been reported among cancer patients.20–22 Some suicide deaths may be misclassified as other ECIs,23 24 and physical, psychological and social impairment due to cancer itself or adverse effects of cancer treatment could increase the risk of accidental death.25

Furthermore, a few population-based studies have demonstrated that the period immediately after a cancer diagnosis is related to elevated mortality from cardiovascular causes among patients with prostate cancer26 27 and those with other cancer types as well.17 Acute psychological stressors, such as earthquakes, war and the death of a loved one, are known to trigger cardiovascular events.28–31 Acute emotional distress induced by a cancer diagnosis may also affect cardiovascular functioning and cause critical outcomes beyond the influence of cancer itself or cancer treatment. Possible mechanisms linking acute psychological stressors to cardiovascular events include pathophysiological pathways that have the potential to cause rupture of vulnerable plaque, thrombosis formation or fatal arrhythmias (eg, increased sympathetic tone, blood pressure, shear stress and blood viscosity; endothelial dysfunction; and hypercoagulability), and health-impairing behaviours related to emotional distress.28 29

Suicide risk among persons with cancer has been suggested to differ between different ethnic and cultural groups.32 Two previous studies have reported risk of suicide among Japanese patients with cancer compared with the general population.22 33 The first, a single-institution study demonstrated that suicide risk among patients newly diagnosed with cancer was significantly elevated within the first year after a diagnosis.33 The second, a population-based prospective study investigating Japanese residents including over 10 000 cancer patients, showed that risk of death by suicide and other ECIs was about 24 and 19 times higher, respectively, among those with cancer within the first year after a cancer diagnosis than among those without cancer.22 There has been no nationwide study examining the risk of suicide among cancer patients in Japan, and cardiovascular mortality risk following a cancer diagnosis has not been investigated in countries other than Sweden and the USA. As Japan is ageing faster than any other country in the world and the number of patients with newly diagnosed cancer is expected to keep increasing,34 the impact of a cancer diagnosis on subsequent stress-related outcomes is a serious public health issue. It is necessary to identify vulnerable patients and the window of maximum risk in order to implement appropriate supportive and preventive intervention.

The Act on Promotion of Cancer Registries was enacted in Japan in 2013 and the National Cancer Registry (NCR) in Japan was launched on 1 January 2016.35 36 According to the Act, hospitals in Japan have a legal duty to report all targeted cancer cases (ie, intraepithelial and malignant tumours corresponding to a behavioural code of 2 or 3 in the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition; benign and uncertain whether benign or malignant central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms and gastrointestinal stromal tumours; and some types of ovarian borderline malignant tumours) to the NCR. The NCR has enabled hospitals to calculate accurate cancer incidences and survival rates, and it is expected that the NCR database will contribute to planning and assessment of evidence-based cancer control policies and promote research in such areas as evaluation of cancer care quality and follow-up surveys in nationwide cohort studies. The first NCR data will become available for research purposes in 2019.

Using data from the NCR, we will conduct the first nationwide population-based study in Japan to characterise the incidence of death by suicide, ECIs and cardiovascular disease among patients with a cancer diagnosis compared with the general population in Japan. We will also aim to identify higher-risk patients and time periods that may require more attention. We hypothesise that the risk of suicide, other ECIs and cardiovascular death is significantly higher within the first year after a cancer diagnosis and that the period soon after a cancer diagnosis is associated with the greatest risk.

Methods

Data sources

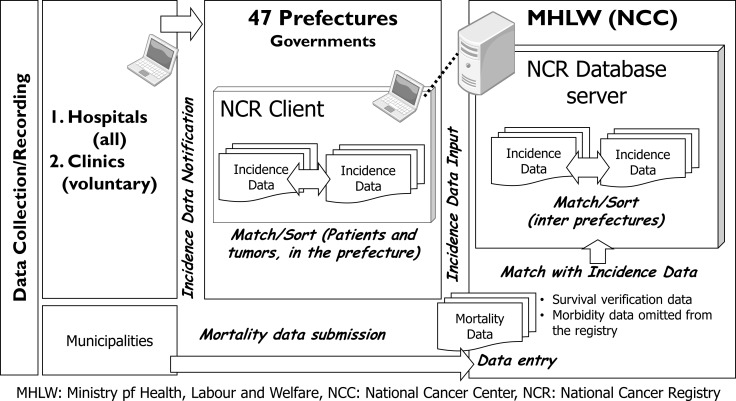

Cancer patients will be identified from the NCR database in Japan. The NCR covers the total population in Japan, and hospitals are required to report all targeted cancer cases newly diagnosed in their institutions from 1 January 2016 onwards, irrespective of patient nationality. The NCR system in Japan is described in figure 1. Incidence data from cancer care hospitals are submitted to prefectual governors and prefectural governors review and match record in their prefecture and enter the data in the NCR database in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) (National Cancer Center (NCC)). The MHLW/NCC matches the cancer registry data interprefectually and information from death certificate on cancer disease is matched with the incidence data in the NCR. The NCC follows up cancer patients in the NCR database by linking to national death certificate data and registers death information in the NCR. The unit of registration is tumour, duplications of the same cancer case are corrected and each cancer is registered separately for cases in which a patient is judged to have multiple primary cancers based on pathology. Data aggregation is based on name, birth date and address of patients. The data collection deadline for each year’s cases is the end of the following year, and the data will become available for research purposes the year after that. Data quality of the NCR for year 2016 cases has been reported to be very high: the proportion of death certificate notification was 4.5%, the proportion of death certificate only was 3.2%, the mortality incidence ratio was 0.37, and the morphological verification proportion was 85.4%.37

Figure 1.

The National Cancer Registry (NCR) system in Japan. Reporting of newly diagnosed cancer cases from 1 January 2016 onwards has become a legislative duty of hospitals in Japan. Information collected in each prefecture must be registered in the NCR database and the National Cancer Center (NCC) follows up patients in the NCR by linking to mortality data based on national death certificate files. MHLW, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

The standard items submitted to the NCR by cancer care hospitals are presented in table 1. The date of cancer diagnosis is defined as the date of the most definitive diagnostic test before initiation of treatment and diagnostic tests are arranged hierarchically by levels of definitiveness as follows: histopathological testing of primary tumour, histopathological testing of metastatic tumour, cytology, certain kind of tumour-specific markers, other clinical testing and clinical diagnosis.38 Information such as race, educational status, marital status, income, insurance status and comorbidity is not registered in the NCR database.

Table 1.

Items submitted to the National Cancer Registry in Japan by cancer care hospitals

| 1. Name of hospital | 14. Date of diagnosis |

| 2. Patient’s identification (ID) number | 15. Circumstance of cancer detection |

| 3. Name (Hiragana) | 16. Extension of disease (clinical) |

| 4. Name (Kanji) | 17. Extension of disease (pathological) |

| 5. Sex | 18. Surgery of primary site |

| 6. Birth date | 19. Laparo/thoracoscopic surgery |

| 7. Address of patients | 20. Endoscopic surgery |

| 8. Laterality | 21. Result of surgery |

| 9. Diagnosis (primary site) | 22. Radiation therapy |

| 10. Diagnosis (morphology) | 23. Chemotherapy |

| 11. Diagnosis facility | 24. Endocrinotherapy |

| 12. Treatment facility | 25. Other treatment |

| 13. Basis of diagnosis | 26. Date of death |

Details of the NCR system have been described previously.35 36

Study population and inclusion criteria

Our study cohort will consist of all cancer cases diagnosed in Japan between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2016 and registered in the NCR and they will be followed until 31 December 2018. We will exclude cancer cases that are diagnosed incidentally at autopsy, reported only on a death certificate or missing a diagnosis date. For individuals with multiple cancers, the start of the at-risk period will be defined as the date of the most recent cancer diagnosis. A total of 995 132 malignant cancer cases (defined by C00–C96 according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10)) were diagnosed in Japan in 2016,37 and about 1 million cancer patients will be included in our study.

Study variables

We will identify cancer patients who died by suicide, ECIs and cardiovascular causes based on underlying cause of death according to ICD-10 registered in the NCR database. Outcomes will be classified as follows: suicide (X60–X84 and Y87.0), other ECIs (V01–X59 and Y10–Y34) and cardiovascular diseases (I00–I99). Cardiovascular death will be further subcategorised as myocardial infarction (I21–I24), other disease of the heart (I10–I13, I71 and I72), embolism or thrombosis (I26, I74, I80.1, I81, I82 and I85.0), stroke (I60–I64), haemorrhagic stroke (I60–I62), ischaemic stroke (I63) and others. Quality of cause of death information in Japan has been reported to be high.39 Other information we will obtain from the NCR includes sex, age at diagnosis, prefecture of residence at diagnosis, presence/absence of multiple primary tumours, primary site of tumour according to ICD-10 codes, basis of diagnosis, date of diagnosis, extension of tumour, presence/absence of each treatment, presence/absence of definitive surgery of the primary site, hospital region, survival status and survival time.

Statistical analysis

Person-years at risk will be computed from the date of a cancer diagnosis to the date of death, or December 31 2018, whichever comes first. Standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) will be calculated as the observed numbers of targeted events (ie, suicide, other ECIs or cardiovascular death) among cancer patients divided by the expected numbers of events in the general population. Excess absolute risks (EARs) will be calculated by subtracting the expected numbers of events from the observed numbers of events; the difference will be then divided by person-years of cancer patients, and the number of events in excess will be expressed per 10 000 person-years. The expected numbers of events will be obtained by multiplying the number of person-years at risk, stratified by sex, age group (0–4, 5–9, …, 80–84, ≥85 years), prefecture and calendar year, by mortality rates from targeted events in each year in the general population in Japan in each corresponding stratum. We will calculate mortality rates by sex, age and prefecture in each year in the general population by dividing the numbers of death from each event occurring in Japan (based on datasets from Vital Statics Japan, provided by the MHLW) by the estimated total population in Japan based on population estimates.40 The numbers of death by each targeted event in the general population will be calculated by using the same definition according to ICD-10 codes as those used in the cancer patients. We will calculate 95% CIs of SMRs and EARs by assuming that the observed numbers of events follow a Poisson distribution.

SMRs and EARs will be calculated separately in relation to a number of factors: sex, age at diagnosis, time since cancer diagnosis, prefecture of residence at diagnosis, primary tumour site, behavioural code of tumour, extension of tumour, whether definitive surgery of the primary site was performed, and presence/absence of multiple tumour. Age at diagnosis will be stratified into the following groups: 0–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and ≥80 years. Time after a cancer diagnosis will be divided into 0–2, 3–5, 6–11 and ≥12 months for suicide and other ECIs. Risk of suicide and other ECIs during the first week after diagnosis will be also separately calculated. For cardiovascular death, we will investigate <1 week, 1 week to <1 month, 1–5 months, 6–11 months and ≥12 months. Primary tumour site will be based on the classifications used in the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan project (table 2).41 The extension of tumour will be classified into localised (confined to the original organ), regional (spread to regional lymph nodes and/or adjacent tissue), metastatic (metastasised to distant organ) and unknown. Stroke will be excluded from cardiovascular mortality in the analysis of CNS tumours, and CNS tumours will be excluded from ‘any cancer’ in the analysis of death from cardiovascular causes.17 Cases of hematological disease will be excluded in the analysis of presence/absence of definitive surgery. Likelihood ratio tests based on Poisson regression models will be conducted to test for heterogeneity. All p value will be two-sided tests and be considered to be statistically significant at a p value of <0.05. We will also perform multivariable regression analysis based on Poisson regression models to adjust for following factors: sex, age at a cancer diagnosis, primary tumour site, extension of tumour, presence/absence of multiple tumours and follow-up period. All factors will be included in the multivariable regression model with no interaction terms. We will also test for the heterogeneity from the multivariable models.

Table 2.

Primary tumour site according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition code used in the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan project41

| Any cancer (C00–C96, D00–D09) | Breast (C50, D05) |

| Oral cavity and pharynx (C00–C14) | Uterus (C53–C55, D06) |

| Oesophagus (C15, D001) | Cervix uteri (C53, D06) |

| Stomach (C16) | Corpus uteri (C54) |

| Colon and rectum (C18–C20, D010–D012) | Ovary (C56) |

| Colon (C18 and D010) | Prostate (C61) |

| Rectum (C19–C20, D011–D012) | Bladder (C67, D090) |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile ducts (C22) | Kidney and urinary organs (except bladder) (C64–C66, C68) |

| Gallbladder and other parts of biliary tract (C23–C24) | Brain and other parts of central nervous system (C70–C72) |

| Pancreas (C25) | Thyroid (C73) |

| Larynx (C32) | Malignant lymphoma (C81–C85, C96) |

| Lung and bronchus (C33–C34, D021–D022) | Multiple myeloma (C88, C90) |

| Skin (C43–C44, D030–D049) | Leukaemia (C91–C95) |

In order to explore the factors affecting their choice of suicide method by cancer patients, we will describe distribution of characteristics of patients and tumours (eg, sex, age at diagnosis, extension of tumour and time since diagnosis) by common suicide methods in Japan (eg, poisoning (X60–X69), hanging (X70) and jumping from heights (X80)).

We will also divide cancer patients who die during the observation period into two groups according to the main cause of death: (1) suicide, other ECIs and cardiovascular diseases and (2) others. Characteristics of patients and tumours will be compared between two groups.

All analyses will be performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows V.25.0.

Discussion

This will be the first nationwide study in Japan to investigate the impact of a cancer diagnosis on subsequent death by suicide, other ECIs and cardiovascular events. The main strength of this study is that it will cover virtually all cancer incidence and subsequent fatal outcomes in Japan using information registered in the NCR. SMRs and EARs of stress-related outcomes after a cancer diagnosis will help to identify higher-risk patients and time periods, and will provide useful evidence for considering the priority of preventive strategies.

Several limitations inherent in this study should be acknowledged. First, our study will not be able to control for potential confounding factors for cancer, suicide and cardiovascular events, such as smoking history and alcohol use, sociodemographic status and pre-existing medical and psychiatric conditions. These data are not collected in the NCR and we cannot link anonymous cancer registry information to other medical and socioeconomic databases. Second, our study will explore mortality outcomes alone and we cannot capture nonfatal outcomes, such as suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and non-lethal cardiovascular events. Our findings will represent only a small portion of the psychological burden associated with a cancer diagnosis. Third, some deaths classified as other ECIs may be misclassification of deaths due to suicide,23 24 and assuming that more under-reporting of suicide occurs in cancer patients than in the general population, risk of suicide among cancer patients in our study will be potentially underestimated. Fourth, in the analysis of presence/absence of definitive surgery of the primary tumour, the result should be interpreted with caution because only patients who did not die by targeted outcomes and survived until surgery could undergo surgery. Finally, if death ascertainment in the NCR system is incomplete, risk of deaths by targeted causes among cancer patients can be underestimated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is reviewed and supported by the Japan Supportive, Palliative and Psychosocial Oncology Group (J-SUPPORT) in terms of the adequacy of the research involved, and approved as J-SUPPORT 1902.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH, MF, TA, TM, KS, TH, KI, KY, IM, YU and YJM contributed to the study conception and design. TM and KS advised on statistical analysis and management of the database. TA and YU supervised the project. SH and MF will perform the data analysis and all coauthors will be involved in interpretation of the data. SH and MF wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all coauthors reviewed the manuscript and provided critical revisions. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the Innovative Research Program on Suicide Countermeasures (IRPSC) (1-2), Japan Support Center for Suicide Countermeasures (JSSC), National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (NCNP).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center. Projected Cancer Statistics. 2018. https://ganjoho.jp/en/public/statistics/short_pred.html (accessed 28 May 2019).

- 2. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. . Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:160–74. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu D, Andersson TM, Fall K, et al. . Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders immediately before and after cancer diagnosis: A nationwide matched cohort study in sweden. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1188–96. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris EC, Barraclough BM. Suicide as an outcome for medical disorders. Medicine 1994;73:281–96. 10.1097/00005792-199411000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robson A, Scrutton F, Wilkinson L, et al. . The risk of suicide in cancer patients: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 2010;19:1250–8. 10.1002/pon.1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spoletini I, Gianni W, Caltagirone C, et al. . Suicide and cancer: where do we go from here? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;78:206–19. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anguiano L, Mayer DK, Piven ML, et al. . A literature review of suicide in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:E14–E26. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fc76c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahn E, Shin DW, Cho SI, et al. . Suicide rates and risk factors among Korean cancer patients, 1993-2005. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2097–105. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu D, Fall K, Sparén P, et al. . Suicide and suicide attempt after a cancer diagnosis among young individuals. Ann Oncol 2013;24:3112–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdt415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oberaigner W, Sperner-Unterweger B, Fiegl M, et al. . Increased suicide risk in cancer patients in Tyrol/Austria. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014;36:483–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vyssoki B, Gleiss A, Rockett IR, et al. . Suicide among 915,303 Austrian cancer patients: who is at risk? J Affect Disord 2015;175:287–91. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin PH, Liao SC, Chen IM, et al. . Impact of universal health coverage on suicide risk in newly diagnosed cancer patients: Population-based cohort study from 1985 to 2007 in Taiwan. Psychooncology 2017;26:1852–9. 10.1002/pon.4396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaceniene A, Krilaviciute A, Kazlauskiene J, et al. . Increasing suicide risk among cancer patients in Lithuania from 1993 to 2012: a cancer registry-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017;26:S197–S203. 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saad AM, Gad MM, Al-Husseini MJ, et al. . Suicidal death within a year of a cancer diagnosis: A population-based study. Cancer 2019;125:972–9. 10.1002/cncr.31876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henson KE, Brock R, Charnock J, et al. . Risk of Suicide After Cancer Diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76:51–60. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hem E, Loge JH, Haldorsen T, et al. . Suicide risk in cancer patients from 1960 to 1999. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4209–16. 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, et al. . Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1310–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson TV, Garlow SJ, Brawley OW, et al. . Peak window of suicides occurs within the first month of diagnosis: implications for clinical oncology. Psychooncology 2012;21:351–6. 10.1002/pon.1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang SM, Chang JC, Weng SC, et al. . Risk of suicide within 1 year of cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer 2018;142:1986–93. 10.1002/ijc.31224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kendal WS, Kendal WM. Comparative risk factors for accidental and suicidal death in cancer patients. Crisis 2012;33:325–34. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dalela D, Krishna N, Okwara J, et al. . Suicide and accidental deaths among patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer. BJU Int 2016;118:286–97. 10.1111/bju.13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamauchi T, Inagaki M, Yonemoto N, et al. . Death by suicide and other externally caused injuries following a cancer diagnosis: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Psychooncology 2014;23:1034–41. 10.1002/pon.3529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pritchard C, Hean S. Suicide and undetermined deaths among youths and young adults in Latin America: comparison with the 10 major developed countries--a source of hidden suicides? Crisis 2008;29:145–53. 10.1027/0227-5910.29.3.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rockett IR, Hobbs G, De Leo D, et al. . Suicide and unintentional poisoning mortality trends in the United States, 1987-2006: two unrelated phenomena? BMC Public Health 2010;10:705 10.1186/1471-2458-10-705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bergen H, Hawton K, Kapur N, et al. . Shared characteristics of suicides and other unnatural deaths following non-fatal self-harm? A multicentre study of risk factors. Psychol Med 2012;42:727–41. 10.1017/S0033291711001747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fall K, Fang F, Mucci LA, et al. . Immediate risk for cardiovascular events and suicide following a prostate cancer diagnosis: prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000197 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fang F, Keating NL, Mucci LA, et al. . Immediate risk of suicide and cardiovascular death after a prostate cancer diagnosis: cohort study in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:307–14. 10.1093/jnci/djp537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dimsdale JE. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1237–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwartz BG, French WJ, Mayeda GS, et al. . Emotional stressors trigger cardiovascular events. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:631–9. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02920.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, et al. . Risk of acute myocardial infarction after the death of a significant person in one’s life: the Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study. Circulation 2012;125:491–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.061770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berntson J, Patel JS, Stewart JC. Number of recent stressful life events and incident cardiovascular disease: Moderation by lifetime depressive disorder. J Psychosom Res 2017;99:149–54. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakash O, Barchana M, Liphshitz I, et al. . The effect of cancer on suicide in ethnic groups with a differential suicide risk. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:114–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cks045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tanaka H, Tsukuma H, Masaoka T, et al. . Suicide risk among cancer patients: experience at one medical center in Japan, 1978-1994. Jpn J Cancer Res 1999;90:812–7. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00820.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Utada M, Ohno Y, Shimizu S, et al. . Cancer incidence and mortality in Osaka, Japan: future trends estimation with an age-period-cohort model. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:3893–8. 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsuda T, Sobue T. Recent trends in population-based cancer registries in Japan: the Act on Promotion of Cancer Registries and drastic changes in the historical registry. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:11–20. 10.1007/s10147-014-0765-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanaka H, Matsuda T. Arrival of a new era in Japan with the establishment of the Cancer Registration Promotion Act. Eur J Cancer Prev 2015;24:542–3. 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Cancer incidence in Japan. 2016. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000468976.pdf (accessed 28 May 2019).

- 38. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center. Manual for the National Cancer Registry. 2016. in Japanese https://ganjoho.jp/data/reg_stat/cancer_reg/national/hospital/ncr_manual_2017rev_201901.pdf (accessed 28 May 2019).

- 39. Mathers CD, Fat DM, Inoue M, et al. . Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:171–7. doi:/S0042-96862005000300009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bureau S. Ministry of the Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Japan. Population Estimates, Annual Report https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=7&month=0&tclass1=000001011679&cycle_facet=tclass1%3Acycle&second2=1 (accessed 28 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hori M, Matsuda T, Shibata A, et al. . Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2009: a study of 32 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2015;45:884–91. 10.1093/jjco/hyv088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.