Abstract

Introduction

Adding neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) to 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone (DEX) improved carboplatin (CBDCA)-induced chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with thoracic cancer. NK1RAs with high-drug cost are raising medical expenses. Olanzapine (OLZ) is less expensive and can be expected to have an excellent effect on CINV. This phase II trial aimed at evaluating the efficacy and safety of 5 mg OLZ plus granisetron (GRN) and DEX in CBDCA combination therapy with area under curve (AUC) ≥5 mg/mL/min for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients with thoracic cancer.

Methods and analysis

This is an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase II trial. Patients who receive CBDCA-based therapies (AUC ≥5) and have never been administered moderate to high emetogenic chemotherapy will be enrolled. All patients will receive a combination of GRN, DEX and OLZ. The primary endpoint is complete response (CR) rate, defined as the absence of emetic episodes and no use of rescue medication for 120 hours after the initiation of CBDCA. Forty-eight patients are required based on our hypothesis that this regimen can improve CR rate from 65% (null hypothesis) to 80% (alternative hypothesis) with a one-sided type I error of 0.1 and a power of 0.8. We set the target sample size at 50 considering dropouts.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each of the participating centres. Data will be presented at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

UMIN000031267.

Keywords: olanzapine, carboplatin, nausea, vomiting

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding 5 mg olanzapine to granisetron and dexamethasone for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after area under curve ≥5 mg/mL/min carboplatin -induced combination therapy in thoracic cancer patients.

A positive result for this phase II trial is necessary before a phase III trial can be conducted. The data will be used to inform a future large multicentre double-blind randomised phase III trial.

Limitations are open-label and single arm design and the study is conducted within the Japanese population.

Introduction

In recent guidelines, carboplatin (CBDCA) is reclassified at the upper limit of the moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) category and/or the highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) category.1–3 The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) (regardless of the CBDCA dose),1 the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (CBDCA at a dose of ≥4 mg/mL/min)2 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (CBDCA at a dose of ≥4 mg/mL/min)3 have recommended emesis prophylaxis using a three-drug regimen including 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist (5-HT3RA), dexamethasone (DEX) and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) in patients receiving CBDCA-based chemotherapy.

CBDCA is widely used against various cancers. The complete response (CR) rate (the absence of emetic episodes and no use of rescue medication) for first generation 5-HT3RA and DEX varies depending on the cancer type; the rate is approximately 50% in patients with gynaecological cancer4 5 and approximately 65% in those with thoracic cancer.6 7 This difference is due to the background of the cancer types. Gynaecological cancer patients are only women and are younger than thoracic cancer patients. Female gender, younger age, non-habitual alcohol intake and non-smoker . are known as risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).8 Therefore, we believe NK1RA with high drug cost is unnecessary for CBDCA-based therapy in thoracic cancer patients. Furthermore, because of the inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4, clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions of apreitant (APR) and fosaprepitant have been reported not only for general agents but also chemotherapy agents.9 Therefore, the development of antiemetic therapy without NK1RA is beneficial in complicated cancer chemotherapy.

Olanzapine (OLZ) is classified as a multiacting receptor-targeted antipsychotic and blocks dopaminergic D1, D2, D3 and D4 receptors, serotonergic 5-TH2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors, histamine H1 receptors and muscarinic acetylcholine M1, M2, M3 and M4 receptors.10 Among its other uses, OLZ is used to improve CINV. Navari et al performed a phase III trial to confirm the superiority of 10 mg OLZ combined with palonosetron (PALO) and DEX to an antiemetic regimen consisting of PALO, DEX and APR in HEC. The study could not demonstrate that the OLZ regimen was superior to the APR regimen and the CR rates for the acute, delayed and overall period were not significantly different between the OLZ regimen and the APR regimen. On the other hand, the OLZ regimen showed excellent control of nausea in the delayed and overall period.11 Moreover, in the USA and Asia, the effectiveness of a combination of 10 mg OLZ and standard antiemetic therapy has been demonstrated for HEC in randomised control trials; however, the resulting patient sedation due to the therapy may be a concern.12–15 In Japan, three phase II studies revealed the efficacy and safety of the combination of 5 mg OLZ and standard triplet therapy for CINV induced by HEC.16–18 In a trial, Yanai et al reported that OLZ at 5 mg and 10 mg showed comparable CR effects, but the 5 mg dose was less sedative.18

However, the effectiveness of OLZ against CBDCA-induced CINV has not been demonstrated. The cost per treatment cycle of 5 mg of OLZ (brand: 733.60 JPY, generic: 180.80 JPY) is less than that of PALO (14 851.00 JPY) and NK1RA (APR: 11 638.20 JPY, fosaprepitant: 14 545.00 JPY), and confirming the effectiveness of the combination of OLZ, first generation 5-HT3RA and DEX would change the standard antiemetic treatment for CBDCA-based chemotherapy in thoracic cancer.

In recent years, the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), in combination with chemotherapy, is available in clinical settings for lung cancer. Arbour et al reported that baseline corticosteroid use was associated with poorer outcomes in patients who were treated with ICI.19 Therefore, there is a concern that DEX as emesis prophylaxis may adversely affect ICI combination chemotherapy. The non-inferiority of DEX, except on days 2 and 3, combined with PALO has been demonstrated for MEC in randomised control trials.20–22 Therefore, use of PALO can reduce the corticosteroid. Among the ICI combination therapies, the pembrolizumab combined with CBDCA and pemetrexed is one of the most often used regimens for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. In the KEYNOTE-189 trial that proved the effectiveness of this regimen for prophylaxis of cutaneous reaction, the administration of DEX at 8 mg per day for 2 days besides DEX of day 1 used for antiemetic therapy was regulated by the protocol.23 Therefore, we plan to administer DEX for 3 days.

The efficacy of OLZ has been demonstrated in both combinations with the first and second generation 5HT3RA in HEC.11–18 24 Therefore, granisetron (GRN) was chosen as 5HT3RA in the study.

Given the above, we plan this open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 5 mg OLZ plus GRN and DEX in CBDCA combination therapy with area under curve (AUC) ≥5 mg/mL/min for the prevention of CINV in patients with thoracic cancer.

Study protocol

Objective

Our objective is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 5 mg OLZ plus GRN and DEX for the prevention of nausea and vomiting during CBDCA combination therapy achieving AUC ≥5 mg/mL/min in patients with thoracic cancer. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating centre and was independently monitored by the alliance data centre and safety monitoring board.

Study setting

This study is an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase II trial conducted in four centres in Japan.

End points

We choose the CR rate, defined as the absence of emetic episodes and no use of rescue medication during the overall assessment period (0–120 hours) after the initiation of CBDCA, as the primary endpoint.

Secondary endpoints are the CR rate in the early assessment period (0–24 hours), the CR rate in the delayed assessment period (25–120 hours), and the complete control rate defined as no significant nausea, no emetic episodes and no use of rescue medication for the acute, delayed, and overall assessment periods. We use a four-grade categorical scale (none, mild, moderate or severe) to stratify nausea and choose the moderate and severe categories to define significant nausea. The total control rate is defined as the absence of nausea and emetic episodes and no use of rescue medication for the acute, delayed, and overall assessment periods. The time to treatment failure is defined as the time to the first emetic episode or the use of rescue medication. The levels of nausea, anorexia, sleepiness, impact on life severity and patient satisfaction with antiemetic therapy are also classified using a four-grade categorical scale. These data are collected from patient diaries. Adverse events are graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) V.4.0.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients with thoracic cancer scheduled to receive CBDCA-based chemotherapy (AUC ≥5).

Age: 20–79 years at registration.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, 1 or 2.

Absence of symptomatic brain metastasis and carcinomatosis.

Absence of a history of the administration of moderate-to-high emetogenic chemotherapy.

No current use of any drug, with antiemetic activity and somnolence, such as 5-HT3RA, NK1RA, corticosteroids, dopamine receptor antagonists, phenothiazine tranquillisers, antihistamine drugs (paclitaxel administration allowed during premedication) and benzodiazepine agents.

- Meeting the following standard values of general clinical tests:

- aspartate aminotransferase ≤100 U/L.

- alanine aminotransferase ≤100 U/L.

- total bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dL.

Patients who provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

History of hypersensitivity or allergy to study drugs or similar compounds.

Antiemetics needed at the time of enrolment.

Started opioid intake in the 48 hours prior to enrolment.

Presence of unstable angina, ischaemic heart disease, cerebral haemorrhage or apoplexy, or active gastric or duodenal ulcer within 6 months prior to enrolment.

Presence of convulsive disorders requiring anticonvulsant therapy.

Presence of ascites effusion requiring paracentesis.

Presence of gastrointestinal obstruction.

Breastfeeding or pregnant women or those not willing to use contraception.

Presence of psychosis or psychiatric symptoms that interfere with daily life.

Abdominal or pelvic irradiation within 6 days prior to enrolment.

Presence of diabetes mellitus.

Being a habitual smoker at the time of enrolment.

Patients deemed inappropriate for the study by the investigator (From daily behaviour, patients who may not be able to keep medication adherence and/or fulfil patient diary etc).

Registration

The accrual started in February 2018.

Treatment methods

The study antiemetic administrations are shown in table 1. All patients receive GRN (1 mg intravenous (iv) infusion on day 1, 30 min before chemotherapy), DEX (9.9 mg iv infusion or 12 mg oral administration on day 1, 30 min before chemotherapy and 6.6 mg iv infusion or 8 mg oral administration on days 2, 3) and OLZ (5 mg oral administration on days 1–4, after supper). In addition, when paclitaxel is used, DEX is administered at 19.8 mg intravenously or 20 mg orally on day 1. DEX injection is provided as DEX sodium phosphate. The 8 mg of DEX sodium phosphate contains 6.6 mg of DEX.

Table 1.

Antiemetic administrations

| Antiemetics | Method of administration |

Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 |

| Granisetoron | iv | 1 mg | |||

| Dexamethasone | po or iv |

12 mg* 9.9 mg* |

8 mg 6.6 mg |

8 mg 6.6 mg |

|

| Olanzapine | po | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg |

*When paclitaxel is used, on day-1 DEX is administered 19.8 mg intravenously or 20 mg orally.

po; per os.

Follow-up

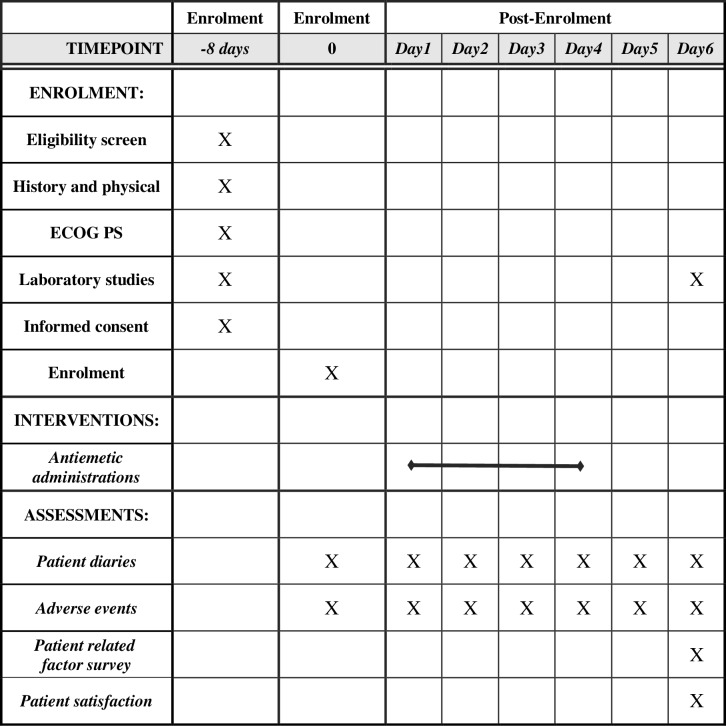

We schedule physical and blood examinations of patients before the initiation of treatment and once between days 5 and 15 after treatment initiation. The data are collected from patient diaries. Patients are required to fill the diary every 24 hours from the start of chemotherapy for a 120-hour period. After the overall assessment period (0–120 hours), patient-reported study diaries are collected (figure 1 provides details of the schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments).

Figure 1.

The schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments.

Study design and statistical methods

The hypothesis of this study is that the CR rate for 5 mg OLZ plus GRN and DEX during CBDCA combination therapy achieving AUC ≥5 mg/mL/min will be significantly higher than that for standard antiemetic doublet therapy.

Other trials have shown CR rates of approximately 65%.6 7 The improvement in CR due to the treatment has to be >10% to enable amendment of the guidelines of MASCC/ESMO20162. According to previous studies, CR rates of antiemesis treatment by PALO, DEX, and APR were 80.5%–92%.25–27 We think an improvement of >15% in the CR rate will be clinically meaningful.

Therefore, assuming the null hypothesis of the CR rate to be ≤65% and an alternative hypothesis to be 80%, we calculate that a minimum of 48 patients are required to achieve a one-sided type I error of 0.1% and 80% of power, based on the exact binomial distribution. Because some dropouts are expected, we set the target sample size at 50. A sample size calculation was performed by SAS V.9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the design of this study.

Ethics and dissemination

A signed informed consent form will be obtained from all patients before enrolment. Data will be presented at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Participating institutions

Gifu University Hospital, Gifu Municipal Hospital, Murakami Memorial Hospital - Asahi University and Gunma Prefectural Cancer Center.

Trial status

February 2018: Protocol approval by the Ethics Committee.

February 2018: Start of inclusion.

December 2019: End of inclusion.

We will submit the manuscript during the first half of 2020.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HI, MS, TG, YF and YO made a significant contribution to the conception and design of the study protocol. MS provided statistical expertise. The protocol was written by HI, MS, TG, YF, TY, NF, KM, DK, TO, MY and CH and critically reviewed by AS, and YO. HI, MS, TG and YF drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding: This work is supported by self-funding from the Department of Cardiology and Respirology at the Gifu University Graduate School of Medicine.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each of the participating centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J, et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2016;27(suppl 5):v119–33. 10.1093/annonc/mdw270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3240–61. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Antiemesis Version 2. 2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf.

- 4. Tanioka M, Kitao A, Matsumoto K, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of aprepitant in nondrinking women younger than 70 years receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2013;109:859–65. 10.1038/bjc.2013.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yahata H, Kobayashi H, Sonoda K, et al. Efficacy of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with a moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimen: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study in patients with gynecologic cancer receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin. Int J Clin Oncol 2016;21:491–7. 10.1007/s10147-015-0928-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ito Y, Karayama M, Inui N, et al. Aprepitant in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 2014;84:259–64. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Endo J, Iihara H, Yamada M, et al. A randomized controlled non-inferiority study comparing the antiemetic effect between intravenous granisetron and oral azasetron based on estimated 5-HT3 receptor occupancy. Anticancer Res 2012;32:3939–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sekine I, Segawa Y, Kubota K, et al. Risk factors of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: index for personalized antiemetic prophylaxis. Cancer Sci 2013;104:711–7. 10.1111/cas.12146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patel P, Leeder JS, Piquette-Miller M, et al. Aprepitant and fosaprepitant drug interactions: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017;83:2148–62. 10.1111/bcp.13322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brafford MV, Glode A. Olanzapine: an antiemetic option for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Adv Pract Oncol 2014;5:24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol 2011;9:188–95. 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Navari RM, Nagy CK, Le-Rademacher J, et al. Olanzapine versus fosaprepitant for the prevention of concurrent chemotherapy radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Community Support Oncol 2016;14:141–7. 10.12788/jcso.0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Babu G, Saldanha SC, Kuntegowdanahalli Chinnagiriyappa L, et al. The efficacy, safety, and cost benefit of olanzapine versus aprepitant in highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a pilot study from South India. Chemother Res Pract 2016;2016:1–5. 10.1155/2016/3439707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang X, Wang L, Wang H, et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine combined with ondansetron in prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting of non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015;72:471–3. 10.1007/s12013-014-0489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med;14:134–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abe M, Hirashima Y, Kasamatsu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine combined with aprepitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone for preventing nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy in gynecological cancer: KCOG-G1301 phase II trial. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:675–82. 10.1007/s00520-015-2829-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakashima K, Murakami H, Yokoyama K, et al. A Phase II study of palonosetron, aprepitant, dexamethasone and olanzapine for the prevention of cisplatin-based chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with thoracic malignancy. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2017;47:840–3. 10.1093/jjco/hyx084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yanai T, Iwasa S, Hashimoto H, et al. A double-blind randomized phase II dose-finding study of olanzapine 10 mg or 5 mg for the prophylaxis of emesis induced by highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2018;23:382–8. 10.1007/s10147-017-1200-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, et al. Impact of baseline steroids on efficacy of programmed cell death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2872–8. 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aapro M, Fabi A, Nolè F, et al. Double-blind, randomised, controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of palonosetron plus dexamethasone for 1 day with or without dexamethasone on days 2 and 3 in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1083–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdp584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Celio L, Frustaci S, Denaro A, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1217–25. 10.1007/s00520-010-0941-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Komatsu Y, Okita K, Yuki S, et al. Open-label, randomized, comparative, phase III study on effects of reducing steroid use in combination with Palonosetron. Cancer Sci 2015;106:891–5. 10.1111/cas.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2078–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tan L, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Clinical research of Olanzapine for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2009;28:131 10.1186/1756-9966-28-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kitazaki T, Fukuda Y, Fukahori S, et al. Usefulness of antiemetic therapy with aprepitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone for lung cancer patients on cisplatin-based or carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:185–90. 10.1007/s00520-014-2339-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kusagaya H, Inui N, Karayama M, et al. Evaluation of palonosetron and dexamethasone with or without aprepitant to prevent carboplatin-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015;90:410–6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miya T, Kobayashi K, Hino M, et al. Efficacy of triple antiemetic therapy (palonosetron, dexamethasone, aprepitant) for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving carboplatin-based, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Springerplus 2016;5:5 10.1186/s40064-016-3769-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.