Abstract

It is established that neurodevelopmental disability (NDD) is common in neonates undergoing complex surgery for congenital heart disease (CHD); however, the trajectory of disability over the lifetime of individuals with CHD is unknown. Several ‘big issues’ remain undetermined and further research is needed in order to optimise patient care and service delivery, to assess the efficacy of intervention strategies and to promote best outcomes in individuals of all ages with CHD. This review article discusses ‘gaps’ in our knowledge of NDD in CHD and proposes future directions.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, genetics, paediatric cardiology, quality of care and outcomes

Introduction

Care of children with congenital heart disease (CHD) is associated with a low risk of periprocedural mortality and morbidity in all but the most complex of conditions, which constitute fewer than 10% of presentations. A broad suite of outcomes is now evaluated, including cardiovascular functional status (how well the circulation works), educational attainment and employment, social engagement and psychological well-being, which, when combined, are assessed as ‘quality of life’ (QOL). An understanding of these issues is important not only for those looking forward after CHD is ‘fixed’ but also for those contemplating long-term expectations after a fetal diagnosis. This is a major issue in the field as it is recognised that QOL is reduced in children with CHD,1 which, in turn, may have a detrimental effect on the QOL of the parents and support networks of those affected.

In this review, we articulate the undetermined ‘big issues’ in neurodevelopment affecting those who require treatment for CHD. We bring together a description of the problem, an overview of the aetiology, evaluation of the effectiveness of current interventions and considerations for the future. For the purpose of the review, CHD patients those require early cardiac intervention are of primary interest, which make up a minority of CHD as a whole. Findings may not be relevant to individuals with minor lesions, including minor pulmonary valve abnormalities and small ventricular septal defects, that do not require surgery.

Incidence and manifestations of neurodevelopmental disability

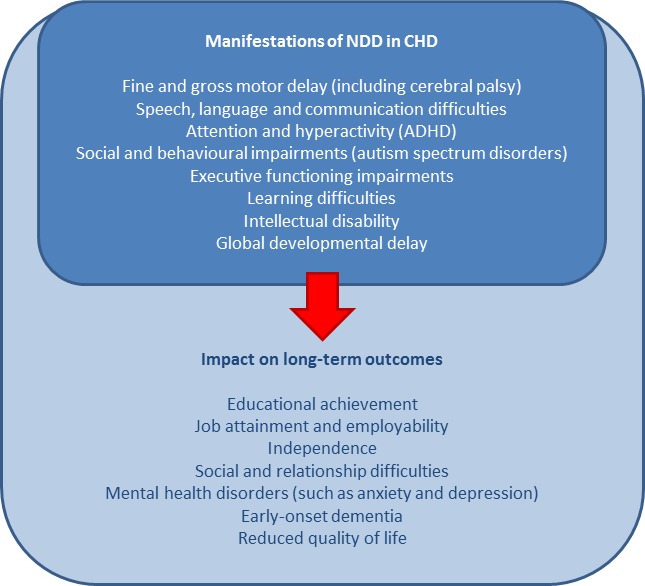

Central to normal growth and learning is brain development. Abnormal brain development is a greater issue for children with CHD (~20% of those requiring cardiac surgical intervention in infancy) compared with those without major illness (~5%). There is a spectrum of manifestations in what is termed neurodevelopmental disability (NDD) (figure 1). At one end, there are typical physical manifestations of developmental ‘delay’ which may resolve or be remediated over time, through to persisting behavioural and psychosocial syndromes, and major disability at the severe end of the phenotype. The pathophysiology of the subentities of NDD may well differ but are grouped for clinical convenience.

Figure 1.

Potential manifestations of NDD in people with CHD and associated long-term outcomes. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CHD, congenital heart disease; NDD, neurodevelopmental disability.

Depending on the definition, NDD may be the most common adverse outcome in children with CHD. Up to 50% of children requiring cardiac intervention exhibit NDD, including mild cognitive impairments, difficulties with attention and hyperactivity, deficits in motor functioning, social interaction, language and communication skills, and delayed executive function,2–7 which may persist into school age and beyond.8–10 As expected, NDD has a detrimental effect on educational achievement and attainment, which consequently affects later employability, independence and relationships, and may heighten the burden of psychological disturbance and reduce overall QOL11–13 (figure 1).

The extent to which these manifestations continue into adolescence and adulthood remains unclear and the subject of ongoing research. While many older CHD patients are doing much better physically than was ever expected at the time of their surgery, understanding the impact of NDD in later life is essential. The adult health system is not well equipped to support these issues, particularly given widespread stigma and negative societal attitudes towards disability, and a lack of adequate resourcing for dedicated neurocognitive services in CHD; a particularly vulnerable time is during the transition to adult health services.14 Advancing our understanding of the onset, causes and long-term trajectory of NDD is important to advance effective intervention and management.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes in CHD at different ages

Children

It is well established that NDD in CHD is an issue, with its origins in early gestation. Infants and children with CHD requiring intervention display NDD across a multitude of domains with outcomes comparable to those observed in premature infants and other sick neonates.3 4 15 In our clinical experience, up to 29% of children requiring cardiac surgery during infancy displayed moderate-to-severe impairment in at least one area of neurodevelopment at age 12 months. While many individuals scored between ‘normative means’, up to 28% had scores ≥2 SD below mean performance in at least one neurodevelopmental scale indicative of ‘mildly’ reduced assessment scores. This suggests that many infants requiring cardiac surgery will have reduced abilities compared with the typical population.3

Abnormalities noted in infancy may persist into early childhood. Utilising the Australian ‘National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy’ data, we demonstrated that 13.1% of children that underwent a cardiac procedure within the first year of life were classified as having ‘special needs’ at school age compared with 4.4% of children that had not had a cardiac procedure, as well as displayed a higher proportion of learning disabilities and speech impairments.16

Standardised assessments, such as the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSITD)17 and the Wechsler Scales of Intelligence,18 are routinely used at key time points throughout childhood, starting with assessments as early as 1 month of age (table 1). The BSITD assessments have been found to underestimate developmental delay19 20 and newer assessments with a high sensitivity and specificity for early detection of cerebral palsy are being introduced to assess CHD infants, such as the Prechtl Qualitative Assessment of General Movements and the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE).21

Table 1.

Example neurodevelopmental assessment tools commonly used in CHD

| Assessment | Age range | Scores |

|

Bayley Scales of Development, Version III* Cognition Expressive language Receptive language Fine motor Gross motor |

1–42 months | ≥8 normal 6–7 mild 2–6 moderate 1–2 severe |

|

Wechsler Scales of Intelligence, Version IV* Full-scale IQ

|

Preschool and primary 2.5 years–7 years 7 months Children 6–16 years Adults >16 years |

≥130 superior or ‘gifted’ 120–129 very high 110–119 bright normal >90 average–low average 69–70 borderline mental functionality <69 mental retardation |

*These assessments are commonly used assessment tools in the CHD population but various other assessments have been used for evaluation in children and adolescents with CHD including: Woodcock Johnson; Wide Range Achievement Test; Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals; Expressive Vocabulary Test; Neuropsychological Assessment; Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; Visual-Motor Integration; Conners’ Continuous Performance Test; Children’s Memory Scale; Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning; Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function; Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency; Peabody Developmental Motor Scales; Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised; Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale; Child Behavior Checklist; Youth Self-Report; Conners’ Rating Scale-Revised; Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; Basic Assessment System for Children and Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale.22

CHD, congenital heart disease.

Assessment frequency is often determined by risk profile, those deemed ‘at-risk’ are routinely re-assessed at specific intervals, with the acknowledgement that risk profile can change over time.22 Scores are typically interpreted compared with normative data, and scores determined to be ‘below average’ usually activate recommendations for intervention involving health professionals from a range of disciplines, including developmental paediatrics, neurology, psychology and allied healthcare providers, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, and child life therapy.

Extending existing guidelines published by the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP), the American Heart Association recommends universal screening and long-term surveillance for NDD in all children with CHD.22 Clinical practice and current research is based on the 2006 AAP algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening that emphasises the importance of early identification and management of developmental disorders, which suggests that earlier intervention improves outcomes23; however, evidence to support this in the CHD cohort is limited and much-needed to support necessary expenditure in health systems.

Adolescents

NDD is reported in nearly twice as many adolescents with CHD compared with population norms,24 with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes observed across various domains, including full-scale IQ, perceptual reasoning, working memory, visual perception, visuomotor integration, and executive and motor functioning.25 Attendance at special schools and lack of final school examination occurs in as many as 12% of adolescents with CHD,26 with up to 65% receiving remedial academic or behavioural services and up to 50% requiring therapeutic services, including physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and psychotherapy or counselling.25 27 When compared with sibling controls, outcomes appear worse than when compared with population norms, particularly for full-scale IQ and processing speed28 and may be a better overall assessment.

Understanding the onset and trajectory of NDD throughout life is important for effective management and optimal intervention; however, the extent to which early childhood outcomes predict later disability is uncertain. The Boston Circulatory Arrest Study (BCAS) and the Aachen Study are the only prospective longitudinal studies in this field. Both explored neurodevelopment at multiple time points throughout childhood and adolescence in individuals with surgically corrected transposition of the great arteries (TGA). The BCAS study found that outcomes in those with TGA were below population norms across various neurodevelopmental domains at different time points throughout childhood,9 10 29 30 and below mean average scores continued to be observed at age 16 years when compared with ‘healthy’ controls, particularly in academic achievement and social cognition. A substantial proportion of TGA patients scored ≥1 SD below the expected population mean across various neurodevelopmental domains, including memory (35%), academic achievement (26%–27%) and visual-spatial skills (54%), and frequencies of scores greater than the cut-off for clinical concern were significantly higher in executive functioning (13% self-reports, 23% parent reports and 38% teacher reports) and attention (19%).

This was accompanied by a higher incidence of brain abnormalities detected by MRI; however, these tended to be acquired rather than developmental and no significant association was identified between MRI abnormality and neurodevelopmental test scores.27 Similar findings were also demonstrated in the Aachen study, where significant motor dysfunction, poorer acquired abilities (learning knowledge) and speech impairment were found at age 5 years compared with population norms,31 32 and assessment at age 10 years showed that neurological and speech impairments were more frequent and motor function, acquired abilities and language were reduced compared with norms.8 33 When re-assessed during adolescence, IQ scores were within the normal range; however, the frequency of scores ≤2 SD below the expected mean for performance IQ was 11%, suggesting a greater incidence of specific cognitive deficits compared with the normal population through adolescence.26

Evidence-based predictors of later NDD will aid in identifying those ‘at-risk’ of adverse outcomes and provide opportunities for intervention. As expected, CHD complexity is predictive of worse neurodevelopmental outcomes in adolescence.34 35 Children with ‘simple’ CHD, such as atrial septal defects, have demonstrated some impairment compared with population norms,36 while others have found no differences in outcomes based on CHD complexity.25 Most neonatal indices, including birth weight and length, and 1 and 5 min Apgar score, are not predictive of adolescent NDD, with the exception of head circumference.35 Head circumference continues to be smaller than average in adolescents with CHD, and neuroimaging studies have demonstrated smaller total brain volumes, total white matter (WM), and cortical and deep grey matter volumes compared with controls, with those with cyanotic CHD being more notably affected compared with acyanotic CHD.37 Smaller brain volumes have been found to correlate with functional outcomes in adolescents with CHD but not control subjects, highlighting the importance of quantitative imaging measurements in this population.37

In time and with more research, these findings may provide a diagnostic tool in the identification and intervention of NDD in CHD; however, the generalisability of findings is currently limited due to the studies being small sample, single time point observations. To fully understand the reliability and clinical significance of these findings, longitudinal studies are needed.

Adults

Adults living with CHD now outnumber children, accounting for up to 66% of the CHD population.38 The limited research to date shows that adults with CHD (ACHD) display NDD across various domains, including reduced abilities in executive functioning,39 information processing speed, psychomotor speed and reaction time,40 overall and divided attention,39 40 fine motor function,39 working memory41 and visuospatial skills,41 with those with more complex CHD being more notably affected compared with adults with simpler CHD.39 40 42 A high frequency of MRI abnormalities and reduced brain volumes in adults with cyanotic CHD has also been observed.43 Adults with more complex CHD have been found to have a higher frequency of neurological comorbidities, such as stroke and seizures, and are more likely to be unemployed and receiving disability benefits despite educational attainment being no different to those with simpler CHD.41

The rate of unemployment across all ACHD is estimated at 18%–50%,11 44 and the incidence of comorbid psychiatric disorders (eg, anxiety and depression), pragmatic language impairment and delayed transition to independent living is increased.45 Understandably, the overall QOL in ACHD is reduced compared with population norms,46 and the accumulative effects of neurological disability pose great demands on the person affected, their support networks and societal resources. Furthermore, the burden of neurocognitive disability is likely to impact the rate of loss of follow-up in this population, which has implications for the risk of complications and consequentially, a higher cost burden on resources. ACHD patients often require additional nursing/allied health support to maintain engagement, which also impacts the costs of care.

As the growing ACHD population ages, new concerns are emerging regarding an increased risk of neurocognitive decline and dementia, particularly early-onset dementia, compared with population norms.38 47 This may be evident earlier in life than typically expected and associated with tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, stroke, disordered glucose metabolism, coronary artery disease and heart failure.47 48 Other risk factors for dementia are also more common in the CHD population, including genetic disorders and the impact of reduced exercise capacity. Adults with severe CHD are considered to have a greater risk of dementia, particularly those with single ventricle morphology.47

Aetiology of the CHD+NDD phenotype—what can we modify?

While we are starting to build a clearer picture of the incidence of NDD over the course of a lifetime, the underlying causes of the CHD+NDD paradigm are not fully understood and the extent to which NDD can be prevented or modified is unknown. Early research focused on intraoperative factors as the cause of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in CHD.29 30 49–51 Use of prolonged deep hypothermic circulatory arrest and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation are still considered to be contributory risk factors for adverse outcomes,2 51 and surgical techniques have been adapted, where possible, to minimise potential detrimental burden. Somewhat surprisingly, perioperative factors have been found to explain only 5%–8% of variability in NDD outcomes following cardiac surgery.2 52 53 The fact that modification and improvements in surgical techniques have not been accompanied by improvement in neurodevelopmental outcomes supports this view.27 54 The current understanding is that patient-specific and many preoperative and antenatal factors are likely to contribute to the majority of neurodevelopmental impairment in people with CHD.

Development of the heart and brain are intimately related and fetal neuroimaging demonstrates abnormalities that are present from early gestation that are likely to impact brain structure and growth in utero as a result of altered perfusion and substrate delivery.55 56 Some changes are dependent on the CHD anatomy, such as retrograde perfusion of the aortic arch via the ductus in fetuses with aortic atresia, and perfusion of the brain with relatively hypoxic blood in fetuses with TGA.57 In support of this concept, dysregulation of some angiogenic genes in the brain of human fetuses with CHD has been observed, possibly as a result of chronic hypoxia contributing to abnormal brain development.58 59 Measurement of fetal cerebral oxygenation by MRI demonstrates a reduction in oxygen levels with increasing gestational age in fetuses with CHD, which is considered to be significantly below typical at as early as 32 weeks gestation; impaired perfusion also correlates with smaller brain size.60 Sun et al61 demonstrated that a 15% reduction in cerebral oxygen delivery and 32% reduction in cerebral VO2 in CHD fetuses were associated with a 13% reduction in fetal brain volume, supporting a direct link between reduced cerebral oxygenation and impaired brain growth.

Disruption in fetal brain perfusion is thought to contribute to greater susceptibility to brain injury in the term neonate with CHD.62 63 Most commonly reported is WM injury (WMI; up to 50% preoperatively and ≥62% postoperatively64 65), which is comparable to the incidence of periventricular leukomalacia identified in preterm infants.63 66 The extent to which WMI worsens with surgery is unclear, but WMI detected both preoperatively and postoperatively is associated with NDD reported at various points throughout childhood,65 67 and adolescents with TGA have demonstrated reduced WM microstructure and globally altered WM topology which correlates with worse neurocognitive functioning across multiple domains.68 69 These data support the notion that the CHD brain may be smaller and relatively underdeveloped at birth. Catch-up growth may be possible as has been demonstrated in infants after the arterial switch procedure for simple transposition,70 noting that persisting WM abnormalities have been reported in other studies.69 71

Several strategies have been suggested to improve fetal brain development. Maternal oxygen therapy is considered as one possible method and has also been used to promote growth of small left ventricle morphology by increasing fetal pulmonary blood flow and left atrial return.59 While this is considered a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in fetuses with some CHD subtypes, this strategy is rarely used in clinical practice.59 72 Translational research in lambs offering an ‘artificial womb’, where ‘normal’ substrate and oxygenation are provided by extracorporeal support have allowed testing of the concept that correction of flow and oxygenation abnormalities can improve brain development73 74 and may eventually form the basis of care for preterm infants with CHD, delaying the time to definitive cardiac care to allow for brain maturation. The fetal brain in CHD may also be affected by more generalised placental insufficiency, which may be difficult to detect using conventional means.57 75 The placenta and fetal heart develop in parallel and share a common vulnerability to genetic defects, suggesting that deleterious defects in these gene pathways could likely result in abnormality in the morphology of both, with placental insufficiency further exacerbating the development of key organs, including both the heart and the brain.57 76–78 Chronic placental insufficiency has been recognised to have serious consequences on fetal growth, known as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which has been associated with CHD79; however, the exact cause and effect mechanisms of this relationship are unknown. Other factors, such as folate metabolism, are also believed to compound the issue of placental insufficiency and IUGR by impacting the underlying mechanisms of cell growth and function.80 To add further ‘insult to injury’, fetal development and growth may also be impacted by external environmental factors, including developmental neurotoxicity due to toxins, such as alcohol, drugs and environmental organophosphates. Certain environmental chemicals have been associated with cognitive and neurological impairment, including diminished intellectual functioning, learning disabilities, attention problems, hyperactivity, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism, and are thought to disrupt the development of the vulnerable fetal brain.81–83

Some very fundamental and readily accessible strategies are known to optimise neurodevelopmental outcome. Fetal cardiac diagnosis is important as it allows for coordination of perinatal care, and also provides an opportunity for detailed antenatal counselling. Antenatal diagnosis is associated with reduced risk of preoperative brain injury, improved postnatal brain development and better neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with complex CHD.73 74 Fetal diagnosis also allows planning of delivery with current guidelines suggesting delivery between 39 and 40 weeks gestation.84 Early-premature and late-premature birth in the CHD population have been associated with greater neurodevelopmental impairment85 and fetuses with CHD should not be delivered early for the convenience of the treating teams.

Information provided during antenatal counselling should include discussion of neurodevelopmental outcomes. For those requiring neonatal cardiac surgery, our own practice is to outline the broad scope of neurodevelopmental impairment at a risk of 2–3 times the rate observed in the population without CHD. We describe a spectrum from motor delay to behavioural issues (including autism and ADHD) and major disability. Anticipated surgical complexity, as well as the risk of acquired brain injury (eg, stroke), must also be considered.2 Thresholds for decisions regarding continuation of pregnancy are individual and not necessarily based on estimates of lesion severity or anticipated neurodevelopmental outcomes. Multidisciplinary support and input into these decisions are required. Genomic sequencing and fetal brain MRI have an emerging but, as yet, unproven role in understanding mechanisms86 and quantification of risk.61

There is considerable but, as yet, unwarranted optimism that genetic variants explain much of the NDD in CHD, possibly as a result of difficulty in identifying other causes of the CHD+NDD phenotype. Nevertheless, there is a growing body of evidence that genetic factors are indeed contributing to altered fetal brain development and often represent the key determinants of NDD outcomes in patients with CHD.45 87 88 Of course, there are several genetic syndromes in which both CHD and NDD co-occur, such as Williams syndrome, Alagille syndrome, Noonan syndrome or 22q11 deletion syndrome, among others89; however, our principal interest remains the much larger number of non-syndromic patients with a largely sporadic mode of presentation.

Homsy et al studied 1213 CHD parent–offspring trios and identified supporting evidence for the long-hypothesised shared genetic origin of at least a proportion of CHD with NDD.88 They found that genes highly expressed in the heart were enriched for high expression in the developing brain and overlapped with genes found to contain damaging de novo variants in a number of NDD cohorts, comprising individuals with isolated NDD. Jin et al90 extended this analysis to 2871 CHD probands, including 2645 parent–offspring trios, and confirmed these findings and additionally identified an overlap between CHD and autism genes with the suggestion that chromatin modifier genes have a specific role. As CHD/NDD gene lists start to emerge, genotype–phenotype correlations require large and well-characterised patient cohorts necessitating multicentre collaboration.

While these studies mark a significant milestone in our understanding of the genetic underpinning of NDD in CHD, the approach is not ready for clinical application. The ability to predict the development of NDD at an early time point on the basis of DNA sequencing is an attractive prospect. Early work in this field using known CHD and NDD genes86 demonstrates substantial genetic variation in CHD+NDD patients in both the ‘heart’ and ‘brain’ genes. More than 1000 genes may be implicated in CHD+NDD patients, with the likelihood that computational assessment of variant burden may be more useful than analysis of specific variants and genes. This is in contrast to the identification of causal variants in CHD (without NDD), which can nowadays be effectively achieved using massively parallel sequencing approaches.91–93 A unifying developmental model for NDD in CHD is yet to be established. Whole-genome sequencing approaches in larger well-defined patient cohorts, including prenatal and postnatal clinical data and outcomes, will be required.

While contemporary research is predominantly focused on perinatal and genetic contributions to altered brain maturation and neurodevelopment, we should again consider whether we are underestimating the role of perioperative factors and chronic circulatory abnormalities, including hypoxia. The key study by Gaynor et al in 200753 introduced the now common understanding that innate patient factors have a greater part to play in determining neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with the perioperative factors previously understood. This study was based on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of 188 neonates and infants who underwent cardiac surgery utilising cardiopulmonary bypass. Perioperative risk factors still have important associations with reduced neurodevelopmental ability.2 94 Acquired perioperative brain injury remains common in CHD, and is correlated with NDD,2 64 and postoperative factors are believed to still have a significant role in outcomes.95

Effectiveness of new assessments and intervention

The multitude of complex and often non-modifiable mechanisms contributing to CHD+NDD make it hard to determine optimal methods of intervention. The extent to which we can minimise or even prevent adverse outcomes is uncertain. Optimal management for those at-risk should include a multidisciplinary approach with early identification, vigorous intervention and routine assessments at various time points throughout life,22 96 97 and many hospital-based Cardiac Neurodevelopment Programs now exist to provide this service.98 99 However, research focusing on the efficacy of neurodevelopmental intervention and treatment strategies in the CHD population is scarce.

Advances in the early detection and treatment of cerebral palsy, unrelated to CHD, are likely to be relevant to CHD patients with milder forms of NDD. Evaluation of newer assessments, such as the General Movements (GMs) assessment, is occurring and has shown that this test is highly sensitive and specific to detect cerebral palsy in cardiac infants at 3 months of age and should be incorporated into routine standardised follow-up for these infants; however, further research is needed into the precise prediction of long-term outcomes using this test.100 Combinations of the GMs and the HINE together with standard assessments, such as MRI and BSITD, can provide accurate and early diagnosis of infants at high risk of cerebral palsy as early as 3 months of age, and can, thus, provide strong impetus for linkage into early intervention programmes to take advantage of the stage of neuroplasticity.21 100 101

The Congenital Heart disease Intervention Program102 is one of the limited intervention trials in CHD which examined the influence of family, particularly maternal, factors on infant neurodevelopment. Parents assigned to the intervention received tailored psychoeducation, narrative therapy, problem-solving techniques and parenting skills training, delivered in six sessions (each of 1–2 hours duration) by a clinical psychologist and paediatric cardiac nurse specialist.

The intervention was initiated when infants were 3 months of age and at 6-month follow-up, infants in the intervention group had significantly higher mental development scores compared with infants in the control group, as well as higher rates of breastfeeding, lower maternal worry scores and greater positive appraisals. Psychomotor scores did not differ between intervention and control infants at 6-month follow-up, with mean scores for both groups indicative of psychomotor delay. While the results of this study provide preliminary evidence that early parental psychological intervention may bolster mental developmental outcomes for infants with CHD, evidence of the longer-term efficacy of this intervention strategy is much-needed, and integrated mental health interventions tailored to support neurobiological health in children with CHD are currently being trialled.103 Psychological and socioeconomic factors and a nurturing family environment are no doubt important for maximising neurodevelopmental potential; however, adequately powered randomised controlled trials which provide data on the long-term effects of structured psychological interventions are needed to determine efficacy in reducing the neurodevelopmental burden associated with CHD.

Calderon and Bellinger104 have described avenues for intervention and treatment of NDD found to be successful in other cohorts, such as the use of psychostimulant medications commonly used in the treatment of attention-deficit disorder to improve working memory and attention performance, intensive computerised training, such as the use of the widely successful Cogmed training programme,105 as well as other non-pharmacological techniques, such as specialised assistance and support within the school classroom. While it is theorised that these techniques could improve neurodevelopmental functioning in affected individuals, controlled trials implementing these strategies in a CHD cohort are lacking, and thus their viability is unclear.

If, as yet undetermined, genetic and epigenetic influences are considered key to the development of NDD, is it reasonable to expect that we can actually modify outcomes? Early evidence would suggest that despite potential genetic causes, early and intensive intervention can improve outcomes in those affected. There is a dynamic interplay between genes and environment that is understood to form the basis of typical neurobehavioural maturation, and it is believed that these principles can be applied to neurodevelopmental disorders, even in the context of a strong genetic component.38 Synaptic development and neural plasticity in the newborn period are highly sensitive to modification and continue to be influenced by environment-dependent factors throughout the first months and years of life. After birth, the brain increases over 100% in volume in the first year and another 15% by the end of the second year of life39 and these key developmental windows are considered crucial in laying the foundations for neurodevelopmental outcomes.40

Cost-effectiveness of intervention is another key concern. Neurodevelopmental interventions are complex, may be life-long, and require a multidisciplinary approach with input from an extensive list of primary health services not necessarily directly linked to CHD, such as psychologists, developmental paediatricians, behavioural neurologists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, as well as non-health resources relating to education performance, employability and social participation.106 It is estimated that interventions to improve neurodevelopment have a high economic return if implemented during pregnancy and early childhood107; however tangible evidence to support this is limited due to the infancy of evidence-based intervention trials in CHD. As our understanding of NDD outcomes in response to new intervention strategies progresses, the cost-benefit of these services should, in turn, be estimated in order to guide the direction of future clinical programmes and care.

Conclusions

CHD+NDD remains a cause for concern across the lifespan of the individual with CHD and the adverse outcomes observed in childhood extend into adolescence and adulthood, potentially increasing the risk of early neurocognitive decline. The aetiology is complex, multifactorial and often speculative, involving many currently non-modifiable factors. Contemporary research efforts are focused on improving intervention strategies to minimise burden and maximise healthy outcomes; however, these strategies are still in their infancy. Controlled intervention trials and extended periods of follow-up are needed to assess the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these techniques and to optimise patient care, resource planning and service delivery for people of all ages with CHD.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have contributed significantly to the content of the article.

Funding: NK is the recipient of a National Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (101229), and a 2018–2019 Harkness Fellowship in Health Care Policy and Practice from the Commonwealth Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no data in this work.

References

- 1.Denniss DL, Sholler GF, Costa DSJ, et al. . Need for Routine Screening of Health-Related Quality of Life in Families of Young Children with Complex Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr 2019;205:21-28.e2 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verrall CE, Walker K, Loughran-Fowlds A, et al. . Contemporary incidence of stroke (focal infarct and/or haemorrhage) determined by neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental disability at 12 months of age in neonates undergoing cardiac surgery utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass†. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2018;26:644–50. 10.1093/icvts/ivx375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker K, Badawi N, Halliday R, et al. . Early Developmental Outcomes following Major Noncardiac and Cardiac Surgery in Term Infants: A Population-Based Study. J Pediatr 2012;161:748–52. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker K, Loughran-Fowlds A, Halliday R, et al. . Developmental outcomes at 3 years of age following major non-cardiac and cardiac surgery in term infants: A population-based study. J Paediatr Child Health 2015;51:1221–5. 10.1111/jpc.12943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaynor JW, Stopp C, Wypij D, et al. . Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Cardiac Surgery in Infancy. Pediatrics 2015;135:816–25. 10.1542/peds.2014-3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaynor JW, Ittenbach RF, Gerdes M, et al. . Neurodevelopmental outcomes in preschool survivors of the Fontan procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:1276–83. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen E, Poole TA, Nguyen V, et al. . Prevalence of ADHD symptoms in patients with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Int 2012;54:838–43. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hövels-Gürich HH, Seghaye M-C, Schnitker R, et al. . Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in school-aged children after neonatal arterial switch operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124:448–58. 10.1067/mtc.2002.122307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, duPlessis AJ, et al. . Neurodevelopmental status at eight years in children with dextro-transposition of the great arteries: The Boston Circulatory Arrest Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;126:1385–96. 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00711-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Kuban KCK, et al. . Developmental and Neurological Status of Children at 4 Years of Age After Heart Surgery With Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest or Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Circulation 1999;100:526–32. 10.1161/01.CIR.100.5.526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfitzer C, Helm PC, Rosenthal L-M, et al. . Educational level and employment status in adults with congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young 2018;28:32–8. 10.1017/S104795111700138X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasmi L, Bonnet D, Montreuil M, et al. . Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Outcomes in Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries across the Lifespan: A State-of-the-Art Review. Front. Pediatr. 2017;5 10.3389/fped.2017.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson WM, Smith-Parrish M, Marino BS, et al. . Neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes across the congenital heart disease lifespan. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2015;39:113–8. 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2015.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everitt IK, Gerardin JF, Rodriguez FH, et al. . Improving the quality of transition and transfer of care in young adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:242–50. 10.1111/chd.12463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morton PD, Ishibashi N, Jonas RA. Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities and Congenital Heart Disease: Insights Into Altered Brain Maturation. Circ Res 2017;120:960–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawley CM, Winlaw DS, Sholler GF, et al. . School-Age Developmental and Educational Outcomes Following Cardiac Procedures in the First Year of Life: A Population-Based Record Linkage Study. Pediatr Cardiol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aylward GP. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development : Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2011: 357–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flanagan DP, McGrew KS, Ortiz SO. The Wechsler Intelligence Scales and Gf-Gc theory: A contemporary approach to interpretation. Needham Heights, MA, US: Allyn & Bacon, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acton BV, Biggs WSG, Creighton DE, et al. . Overestimating Neurodevelopment Using the Bayley-III After Early Complex Cardiac Surgery. Pediatrics 2011;128:e794–800. 10.1542/peds.2011-0331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chinta S, Walker K, Halliday R, et al. . A comparison of the performance of healthy Australian 3-year-olds with the standardised norms of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (version-III). Arch Dis Child 2014;99:621–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, et al. . Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, et al. . Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children With Congenital Heart Disease: Evaluation and Management. Circulation 2012;126:1143–72. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee Identifying Infants and Young Children With Developmental Disorders in the Medical Home: An Algorithm for Developmental Surveillance and Screening. Pediatrics 2006;118:405–20. 10.1542/peds.2006-1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassidy AR, White MT, DeMaso DR, et al. . Executive Function in Children and Adolescents with Critical Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2015;21:34–49. 10.1017/S1355617714001027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer C, von Rhein M, Knirsch W, et al. . Neurodevelopmental outcome, psychological adjustment, and quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:1143–9. 10.1111/dmcn.12242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinrichs AKM, Holschen A, Krings T, et al. . Neurologic and psycho-intellectual outcome related to structural brain imaging in adolescents and young adults after neonatal arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:2190–9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Rivkin MJ, et al. . Adolescents with d-Transposition of the Great Arteries Corrected with the Arterial Switch Procedure: Neuropsychological Assessment and Structural Brain Imaging. Circulation 2011;124:1361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy LK, Compas BE, Reeslund KL, et al. . Cognitive and attentional functioning in adolescents and young adults with Tetralogy of Fallot and d-transposition of the great arteries. Child Neuropsychology 2017;23:99–110. 10.1080/09297049.2015.1087488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellinger DC, Jonas RA, Rappaport LA, et al. . Developmental and Neurologic Status of Children after Heart Surgery with Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest or Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass. N Engl J Med 1995;332:549–55. 10.1056/NEJM199503023320901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellinger DC, Rappaport LA, Wypij D, et al. . Patterns of Developmental Dysfunction After Surgery During Infancy to Correct Transposition of the Great Arteries. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 1997;18:75–83. 10.1097/00004703-199704000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hövels-Gürich HH, Seghaye M-C, Däbritz S, et al. . Cognitive and motor development in preschool and school-aged children after neonatal arterial switch operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;114:578–85. 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70047-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hövels-Gürich HH, Seghaye MC, Däbritz S, et al. . Cardiological and general health status in preschool- and school-age children after neonatal arterial switch operation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;12:593–601. 10.1016/S1010-7940(97)00232-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hovels-Gurich HH, et al. Long term behavioural outcome after neonatal arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. Arch Dis Child 2002;87:506–10. 10.1136/adc.87.6.506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karsdorp PA, Everaerd W, Kindt M, et al. . Psychological and Cognitive Functioning in Children and Adolescents with Congenital Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:527–41. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matos SM, Sarmento S, Moreira S, et al. . Impact of Fetal Development on Neurocognitive Performance of Adolescents with Cyanotic and Acyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2014;9:373–81. 10.1111/chd.12152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarrechia I, Miatton M, De Wolf D, et al. . Neurocognitive development and behaviour in school-aged children after surgery for univentricular or biventricular congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:167–74. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Rhein M, Buchmann A, Hagmann C, et al. . Brain volumes predict neurodevelopment in adolescents after surgery for congenital heart disease. Brain 2014;137:268–76. 10.1093/brain/awt322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marelli AJ, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, et al. . Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation 2014;130:749–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyagi M, Fteropoulli T, Hurt CS, et al. . Cognitive dysfunction in adult CHD with different structural complexity. Cardiol Young 2017;27:851–9. 10.1017/S1047951116001396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klouda L, Franklin WJ, Saraf A, et al. . Neurocognitive and executive functioning in adult survivors of congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:91–8. 10.1111/chd.12409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ilardi D, Ono KE, McCartney R, et al. . Neurocognitive functioning in adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:166–73. 10.1111/chd.12434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daliento L, Mapelli D, Volpe B. Measurement of cognitive outcome and quality of life in congenital heart disease. Heart 2006;92:569–74. 10.1136/hrt.2004.057273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cordina R, Grieve S, Barnett M, et al. . Brain Volumetrics, Regional Cortical Thickness and Radiographic Findings in Adults with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. Neuroimage 2014;4:319–25. 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zomer AC, Vaartjes I, Uiterwaal CSP, et al. . Social burden and lifestyle in adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1657–63. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.01.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marelli A, Miller SP, Marino BS, et al. . Brain in Congenital Heart Disease Across the Lifespan. Circulation 2016;133:1951–62. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunter AL, Swan L. Quality of life in adults living with congenital heart disease: beyond morbidity and mortality. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E1632–E1636. 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagge CN, Henderson VW, Laursen HB, et al. . Risk of Dementia in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Population-Based Cohort Study. Circulation 2018;137:1912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de la Torre JC. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2012;2012:1–15. 10.1155/2012/367516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffman GM, Mussatto KA, Brosig CL, et al. . Systemic venous oxygen saturation after the Norwood procedure and childhood neurodevelopmental outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;130:1094–100. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massaro AN, El-dib M, Glass P, et al. . Factors associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with congenital heart disease. Brain and Development 2008;30:437–46. 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamrick SEG, Gremmels DB, Keet CA, et al. . Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Infants Supported With Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation After Cardiac Surgery. Pediatrics 2003;111:e671–5. 10.1542/peds.111.6.e671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaynor JW, Stopp C, Wypij D, et al. . Impact of Operative and Postoperative Factors on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Cardiac Operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:843–9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.05.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G, Jarvik GP, et al. . Patient characteristics are important determinants of neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age after neonatal and infant cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:1344–53. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirsch JC, Jacobs ML, Andropoulos D, et al. . Protecting the infant brain during cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1365–73. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khalil A, Bennet S, Thilaganathan B, et al. . Prevalence of prenatal brain abnormalities in fetuses with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:296–307. 10.1002/uog.15932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brossard-Racine M, du Plessis AJ, Vezina G, et al. . Prevalence and Spectrum of In Utero Structural Brain Abnormalities in Fetuses with Complex Congenital Heart Disease. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2014;35:1593–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McQuillen PS, Goff DA, Licht DJ. Effects of congenital heart disease on brain development. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2010;29:79–85. 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sánchez O, Ruiz‐Romero A, Domínguez C, et al. . Brain angiogenic gene expression in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;52:734–8. 10.1002/uog.18977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Co-Vu J, Lopez-Colon D, Vyas HV, et al. . Maternal hyperoxygenation: A potential therapy for congenital heart disease in the fetuses? A systematic review of the current literature. Echocardiography 2017;34:1822–33. 10.1111/echo.13722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lauridsen MH, Uldbjerg N, Henriksen TB, et al. . Cerebral Oxygenation Measurements by Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Fetuses With and Without Heart Defects. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:e006459 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun L, Macgowan CK, Sled JG, et al. . Reduced Fetal Cerebral Oxygen Consumption Is Associated With Smaller Brain Size in Fetuses With Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation 2015;131:1313–23. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hövels-Gürich HH. Factors Influencing Neurodevelopment after Cardiac Surgery during Infancy. Front. Pediatr. 2016;4 10.3389/fped.2016.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo T, Chau V, Peyvandi S, et al. . White matter injury in term neonates with congenital heart diseases: Topology & comparison with preterm newborns. Neuroimage 2019;185:742–9. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beca J, Gunn JK, Coleman L, et al. . New white matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation 2013;127:971–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Claessens NHP, Algra SO, Ouwehand TL, et al. . Perioperative neonatal brain injury is associated with worse school‐age neurodevelopment in children with critical congenital heart disease. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60:1052–8. 10.1111/dmcn.13747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hinton RB, Andelfinger G, Sekar P, et al. . Prenatal head growth and white matter injury in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Res 2008;64:364–9. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181827bf4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andropoulos DB, Ahmad HB, Haq T, et al. . The association between brain injury, perioperative anesthetic exposure, and 12-month neurodevelopmental outcomes after neonatal cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Paediatr Anaesth 2014;24:266–74. 10.1111/pan.12350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rollins CK, Newburger JW, Roberts AE. Genetic contribution to neurodevelopmental outcomes in congenital heart disease: are some patients predetermined to have developmental delay? Curr Opin Pediatr 2017;29:529–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panigrahy A, Schmithorst VJ, Wisnowski JL, et al. . Relationship of white matter network topology and cognitive outcome in adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries. Neuroimage 2015;7:438–48. 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ibuki K, Watanabe K, Yoshimura N, et al. . The improvement of hypoxia correlates with neuroanatomic and developmental outcomes: Comparison of midterm outcomes in infants with transposition of the great arteries or single-ventricle physiology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:1077–85. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bellinger DC, Rivkin MJ, DeMaso D, et al. . Adolescents with tetralogy of Fallot: neuropsychological assessment and structural brain imaging. Cardiol Young 2015;25:338–47. 10.1017/S1047951114000031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelly CJ, Makropoulos A, Cordero-Grande L, et al. . Impaired development of the cerebral cortex in infants with congenital heart disease is correlated to reduced cerebral oxygen delivery. Sci Rep 2017;7:15088 10.1038/s41598-017-14939-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Partridge EA, Davey MG, Hornick MA, et al. . An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. Nat Commun 2017;8:15112 10.1038/ncomms15112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lawrence KM, McGovern PE, Mejaddam A, et al. . Chronic intrauterine hypoxia alters neurodevelopment in fetal sheep. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rychik J, Goff D, McKay E, et al. . Characterization of the Placenta in the Newborn with Congenital Heart Disease: Distinctions Based on Type of Cardiac Malformation. Pediatr Cardiol 2018;39:1165–71. 10.1007/s00246-018-1876-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maslen CL. Recent Advances in Placenta–Heart Interactions. Front Physiol 2018;9:735 10.3389/fphys.2018.00735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perez-Garcia V, Fineberg E, Wilson R, et al. . Placentation defects are highly prevalent in embryonic lethal mouse mutants. Nature 2018;555:463–8. 10.1038/nature26002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sparrow DB, Boyle SC, Sams RS, et al. . Placental Insufficiency Associated with Loss of Cited1 Causes Renal Medullary Dysplasia. JASN 2009;20:777–86. 10.1681/ASN.2008050547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wallenstein MB, Harper LM, Odibo AO, et al. . Fetal congenital heart disease and intrauterine growth restriction: a retrospective cohort study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2012;25:662–5. 10.3109/14767058.2011.597900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosario FJ, Nathanielsz PW, Powell TL, et al. . Maternal folate deficiency causes inhibition of mTOR signaling, down-regulation of placental amino acid transporters and fetal growth restriction in mice. Sci Rep 2017;7:3982 10.1038/s41598-017-03888-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Felice A, Ricceri L, Venerosi A, et al. . Multifactorial Origin of Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Approaches to Understanding Complex Etiologies. Toxics 2015;3:89–129. 10.3390/toxics3010089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lyall K, Schmidt RJ, Hertz-Picciotto I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:443–64. 10.1093/ije/dyt282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Slotkin TA. Cholinergic systems in brain development and disruption by neurotoxicants: nicotine, environmental tobacco smoke, organophosphates. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2004;198:132–51. 10.1016/j.taap.2003.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Donofrio MT, Moon-Grady AJ, Hornberger LK, et al. . Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;129:2183–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goff DA, Luan X, Gerdes M, et al. . Younger gestational age is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:535–42. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blue GM, Ip E, Walker K, et al. . Genetic burden and associations with adverse neurodevelopment in neonates with congenital heart disease. Am Heart J 2018;201:33–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blue GM, Kirk EP, Giannoulatou E, et al. . Advances in the Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease: A Clinician’s Guide. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:859–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Homsy J, Zaidi S, Shen Y, et al. . De novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies. Science 2015;350:1262–6. 10.1126/science.aac9396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.A. Richards A, Garg V. Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease. Curr Cardiol Rev 2010;6:91–7. 10.2174/157340310791162703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jin SC, Homsy J, Zaidi S, et al. . Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nat Genet 2017;49:1593–601. 10.1038/ng.3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alankarage D, Ip E, Szot JO, et al. . Identification of clinically actionable variants from genome sequencing of families with congenital heart disease. Genet Med 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blue GM, Kirk EP, Giannoulatou E, et al. . Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies pathogenic variants in familial congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2498–506. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Szot JO, Cuny H, Blue GM, et al. . A Screening Approach to Identify Clinically Actionable Variants Causing Congenital Heart Disease in Exome Data. Circulation 2018;11:e001978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wernovsky G, Licht DJ. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children With Congenital Heart Disease—What Can We Impact? Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2016;17(8 Suppl 1):S232–S242. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nattel SN, Adrianzen L, Kessler EC, et al. . Congenital Heart Disease and Neurodevelopment: Clinical Manifestations, Genetics, Mechanisms, and Implications. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2017;33:1543–55. 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Knutson S, Kelleman MS, Kochilas L. Implementation of Developmental Screening Guidelines for Children with Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr 2016;176:135–41. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guralnick MJ. Early Intervention for Children with Intellectual Disabilities: An Update. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2017;30:211–29. 10.1111/jar.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Soto CB, Olude O, Hoffmann RG, et al. . Implementation of a Routine Developmental Follow-up Program for Children with Congenital Heart Disease: Early Results. Congenit Heart Dis 2011;6:451–60. 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brosig C, Butcher J, Butler S, et al. . Monitoring developmental risk and promoting success for children with congenital heart disease: Recommendations for cardiac neurodevelopmental follow-up programs. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology 2014;2:153–65. 10.1037/cpp0000058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Crowle C, Galea C, Walker K, et al. . Prediction of neurodevelopment at one year of age using the General Movements assessment in the neonatal surgical population. Early Hum Dev 2018;118:42–7. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Crowle C, Badawi N, Walker K, et al. . General Movements Assessment of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit following surgery. J Paediatr Child Health 2015;51:1007–11. 10.1111/jpc.12886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McCusker CG, Doherty NN, Molloy B, et al. . A controlled trial of early interventions to promote maternal adjustment and development in infants born with severe congenital heart disease. Child Care, Health Dev 2010;36:110–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kasparian NA, Winlaw DS, Sholler GF. “Congenital heart health”: how psychological care can make a difference. Med J Aust 2016;205:104–7. 10.5694/mja16.00392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Calderon J, Bellinger DC. Executive function deficits in congenital heart disease: why is intervention important? Cardiol Young 2015;25:1238–46. 10.1017/S1047951115001134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roording-Ragetlie S, Klip H, Buitelaar J, et al. . Working Memory Training in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Psychology 2016;07:310–25. 10.4236/psych.2016.73034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lamsal R, Zwicker JD. Economic Evaluation of Interventions for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Opportunities and Challenges. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2017;15:763–72. 10.1007/s40258-017-0343-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Edmond KM, Strobel NA, McAuley K, et al. . Economic evaluation of interventions delivered by primary care providers to improve neurodevelopment in children aged under 5 years: protocol for a scoping review. Syst Rev 2017;6:59 10.1186/s13643-017-0450-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]